Abstract

Cryptosporidium and Giardia are of public health importance, with recognized transmission through recreational waters. Therefore, both can contaminate marine waters and shellfish, with potential to infect marine mammals in nearshore ecosystems. A 2-year study was conducted to evaluate the presence of Cryptosporidium and Giardia in mussels located at two distinct coastal areas in California, namely, (i) land runoff plume sites and (ii) locations near sea lion haul-out sites, as well as in feces of California sea lions (CSL) (Zalophus californianus) by the use of direct fluorescent antibody (DFA) detection methods and PCR with sequence analysis. In this study, 961 individual mussel hemolymph samples, 54 aliquots of pooled mussel tissue, and 303 CSL fecal samples were screened. Giardia duodenalis assemblages B and D were detected in hemolymph from mussels collected near two land runoff plume sites (Santa Rosa Creek and Carmel River), and assemblages C and D were detected in hemolymph from mussels collected near a sea lion haul-out site (White Rock). These results suggest that mussels are being contaminated by protozoa carried in terrestrial runoff and/or shed in the feces of CSL. Furthermore, low numbers of oocysts and cysts morphologically similar to Cryptosporidium and Giardia, respectively, were detected in CSL fecal samples, suggesting that CSL could be a source and a host of protozoan parasites in coastal environments. The results of this study showed that Cryptosporidium and Giardia spp. from the feces of terrestrial animals and CSL can contaminate mussels and coastal environments.

INTRODUCTION

Cryptosporidium and Giardia spp. are zoonotic waterborne pathogens known to be released into the environment through human and animal fecal contamination (1–3). Previous studies have shown that these fecal protozoal parasites and other enteric pathogens are transported via freshwater sources to estuarine ecosystems in California (4–6). In coastal areas, this “pathogen pollution” may lead to contamination of surface waters and shellfish, which can serve as a source of infection for humans and marine mammals.

Cryptosporidium oocysts and Giardia cysts are ideally suited for transmission through recreational waters because they can be excreted in large quantities by animals and humans (7–10) and are immediately infectious upon fecal excretion (3) even at a low doses (7, 8). Cryptosporidium spp. are particularly problematic because oocysts may not be removed by all water filtration processes due to their small size (5 μm). In addition, a fully efficacious drug treatment for cryptosporidiosis remains elusive (3). Cryptosporidium oocysts and Giardia cysts can survive for long periods of time in environmental waters, resist chlorine-based treatments, and can be concentrated and remain infectious in shellfish (1, 2, 11–14).

California sea lions (CSL) (Zalophus californianus) haul out in large numbers at sites where fecal contamination and pathogen pollution can be significant; therefore, it is possible that these marine mammals are exposed to and infected with protozoan parasites. Cryptosporidium parvum and Giardia duodenalis have been detected in the feces of California sea lions recovered from a marine mammal rehabilitation facility located in the northern California coastal area (15), documenting for the first time the presence of infections with these potentially zoonotic pathogens. Although this suggests that California sea lion haul-out sites may serve as a source of parasite contamination, the public health implications are still not clear since the assemblages of the G. duodenalis detected in sea lions have not been determined. Understanding the role of CSL in the contamination of marine environments and the zoonotic potential of the protozoa shed in their feces is important because these marine mammals can be found living close to beaches that are heavily used by humans for recreation and seafood harvest. Unfortunately, the chances of detecting a positive fecal sample in the field can be difficult because fecal shedding of oocysts and cysts is usually high only after acute infection and can then be intermittent.

In this study, wild mussels were used as bioindicators of fecal protozoa in environmental samples. This approach has merit due to the high filtration rate of mussels, which can filter over 2 liters of water/h/shellfish (16), and helps overcome dilution limitations of direct water testing. Shellfish have been used as bioindicators of pathogen pollution in nearshore waters in previous studies (5, 13, 17) because pathogenic microorganisms that occur in marine environments may be filtered by the gills during feeding and become concentrated in the digestive tract/glands of the mollusk (18). Mussels are also frequently found at CSL haul-out sites and, therefore, may be exposed to fecal material. Thus, molecular identification of Cryptosporidium and Giardia in these mussels could provide information about the possible role of CSL in the transmission of protozoan parasites to the marine environment.

Previous studies have found evidence of Cryptosporidium oocysts and Giardia cysts in marine environments by DNA amplification of parasite sequences in the tissues of filter-feeding bivalves that serve as prey for both sea otters and some humans in coastal California (13, 19–21). Host-specific and anthropozoonotic Cryptosporidium genotypes have been recovered previously from marine shellfish in California (22); however, whether these oocysts were shed by terrestrial animals and/or marine mammals is unclear.

The objectives of this study were (i) to test for the presence of Cryptosporidium oocysts and Giardia cysts in mussels at two distinct coastal areas, (a) land runoff plume sites and (b) locations near CSL haul-out sites, as well as in CSL feces and (ii) to genotype protozoal DNA detected in California sea lion feces and mussels (Mytilus californianus). We hypothesized that the genotypes found in terrestrial animals would be present in mussels and CSL feces if pathogen pollution were flowing from land to sea. The results of this study contribute to our understanding of the fate and transport of Cryptosporidium and Giardia parasites in nearshore marine environments and of the possible role of CSL as a nearshore host for these parasites.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The presence of the protozoan parasites Cryptosporidium spp. and Giardia spp. was screened in mussels (Mytilus californianus) and the feces of California sea lions (Zalophus californianus) collected from the wild. Specific sampling sites were selected based on accessibility and safety for boat-based and ground work and on locations where freshwater runoff and sea lion haul-out sites are distinctly separated. Collection dates were based on periods of low tide, surf, and swell. Samples were collected during the wet season (December to May) and dry season (June to November) (23) for 2 years (2011 to 2013). A wet season was identified as the period starting from when the seasonal rivers began discharging to the ocean until 30 days after the river mouth closed; otherwise, the season was considered dry.

Sample collection.

California sea lion (CSL) feces samples were collected from haul-out sites (rookeries where the CSL rest) located at Año Nuevo Island near Pescadero, Point Lobos State Reserve near Monterey, and White Rock near Cambria, in California (Fig. 1). Feces to be analyzed for Cryptosporidium oocysts and Giardia cysts were collected with a tongue depressor and then placed in 50-ml conical tubes that were placed in plastic bags labeled with the site name and date of collection. All samples were placed in ice chests and transported within 24 h to the laboratory of the University of California, Davis (UC Davis), where they were stored at 4°C and processed within 48 h of collection.

FIG 1.

Locations of mussel and California sea lion (CSL) fecal sample collection sites along the central California coast, with filled stars representing CSL haul-out sites, filled circles representing land runoff sites, and gray rectangles representing Giardia DNA-positive mussel hemolymph. Map created using Quantum GIS version (QGIS) 1.8-Lisboa open source software (http://qgis.osgeo.org) under a Creative Commons license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/).

Mussels were collected near two possible sources of pathogen pollution, adjacent to two freshwater sources (Carmel River in Monterey area and Santa Rosa Creek in the Cambria area; Fig. 1) and near the two CSL haul-out sites (Point Lobos State Reserve in the Monterey area and White Rock in the Cambria area) described above. At each site, at least 40 mussels were collected during each sampling effort for the 2-year sampling period. Mussels were collected during low tide and placed in plastic bags labeled with the site name, date of collection, and number of mussels collected. Samples were shipped on ice to UC Davis for pathogen analysis within 24 h.

Fecal sample processing.

Five grams of CSL fecal sample, or the whole sample if it weighed less than 5 g (15), was processed as previously described by Dabritz et al. (24) with the following modifications. The feces samples were homogenized in 0.1% Tween solution, and the tubes were centrifuged at 1,000 × g for 20 min. With a smooth movement, the supernatant was removed, and by the use of a loop the surface of the pellet was transferred to a well of a 3-well slide, as described by Marks et al. (25). Within 12 h, the slides were stained by the direct fluorescent antibody (DFA) technique using Waterborne kit reagents (Aqua-Glo G/C Direct; Waterborne Inc., New Orleans, LA) per the manufacturer's instructions and according to Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) method 1623 (17). Slides were stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) and DAPI (4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) and examined for protozoa by the use of an Axioscop epifluorescence microscope.

Organisms were visualized at ×200 magnification, and identifications were confirmed at ×400 magnification (17). Cryptosporidium oocysts were identified as ∼5-μm-diameter spheres outlined in apple green and often with a midline seam, whereas Cryptosporidium andersoni/C. muris-like organisms were identified as 5-by-7-μm elliptical forms (17). Giardia cysts were also apple green but oval and 9 to 14 μm long (17). All slides were read by the same experienced microscopist and confirmed by a second microscopist. Any DFA-positive samples were concentrated by the use of immunomagnetic separation (IMS) (Dynal Biotech, Olso, Norway), as previously described by Miller et al. (17), with some modifications. Five loops filled with fecal sample were processed, the step consisting of dissociation of bead-parasite complexes with 0.1 N HCl was omitted, and the concentrated samples were placed in a 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tube instead of onto a DFA slide. The samples were then subjected to DNA extraction and conventional PCR (described in detail below) for confirmation and sequence analysis of Cryptosporidium and Giardia.

Hemolymph sample processing.

Hemolymph samples were taken from 30 individual mussels from each site. The hemolymph collection methods and DNA extraction, amplification, and sequencing methods were as described by Miller et al. (26). The cell pellet homogenized in 100 μl of supernatant was subjected to DNA extraction adapting the Qiagen DNA minikit manufacturer instructions (described below) within 24 h of extraction. Hemolymph and DNA were stored at −20°C. Hemolymph samples were not processed by DFA methods because hemocytes tend to autofluoresce, thus making oocyst visualization difficult (22).

Mussel tissue sample processing.

Tissues of 30 mussels per site per sampling event were scraped and blended to obtain a pool of mussel tissue homogenate. Mussel homogenate was then sieved using 100-μm-pore-size cell strainers to obtain three aliquots of 4 g each per sample per site per sampling event. The samples were centrifuged at 1,000 × g for 15 min, and the supernatant was removed from the tube. Detection of Cryptosporidium oocysts and Giardia cysts in the pellets of mussel homogenate involved concentration by IMS and quantification by the DFA technique as described above, except that the step consisting of dissociation of the bead-parasite complex was included as described by Miller et al. (17). The parasite dissociation steps were repeated once. Parasite-positive samples were then subjected to DNA extraction and conventional PCR for confirmation and sequencing of Cryptosporidium and Giardia as described below.

DNA extraction protocol.

A modification of a protocol described by Miller et al. (22) was followed for DNA extraction from a 100-μl (maximum) pellet of hemolymph- and DFA-positive or -suspicious CSL feces and mussel tissue homogenate. Proteinase K (40 μl) was added to the sample and kept at 56°C overnight for sample digestion. By the use of the Qiagen DNA minikit tissue protocol (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, CA), the sample was bound to a QIAamp column and washed and the DNA eluted with 50 μl of 95°C 10% buffer AE. Extracted DNA was stored at −20°C until PCR analysis.

Conventional PCR protocols.

PCR techniques for detection of Cryptosporidium DNA in hemolymph, DFA-positive CSL feces, and DFA-positive mussel homogenate were based on two genes used for molecular characterization: the 18S rRNA gene (27–29) and the COWP gene (30). To initially screen samples, a 298-bp DNA fragment was amplified using a modification of the Morgan 18S rRNA PCR protocol. This assay was chosen as a screening tool as a previous study showed that the Morgan protocol was more sensitive though less specific than the Xiao 18S rRNA assay (17, 26).

PCR mixtures contained 5 μl (1×) 10× PCR buffer with 1.5 mM MgCl2, 3 μl (3 mM) of additional MgCl2, 1 μl (200 mM) deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs), 0.2 μl (0.4 μg/ml reaction) 10% bovine serum albumin (BSA), 0.5 μl (200 nM) of each primer at a concentration of 20 pmol/μl, 0.25 μl (1.25 U) HotStarTaq Plus polymerase plus 3 μl DNA for hemolymph and 5 μl DNA for CSL feces, and PCR-grade water in a 50-μl total volume. Amplification conditions for the PCRs started with 95°C for 5 min and proceeded as previously described by Morgan et al. (27). Amplified PCR products were combined with 2 μl of Blue/Orange loading dye (Promega Corporation, Fitchburg, WI) and loaded into a 1.5% to 2% gel stained with ethidium bromide (1.5 μl) for electrophoresis.

To further characterize samples that yielded a positive result using the Morgan 18S rRNA assay, a 850-bp DNA segment was amplified using a modified Xiao 18S rRNA nested-PCR protocol (28, 29). PCR mixtures contained 5 μl (1×) 10× PCR buffer with 1.5 mM MgCl2, 12 μl (6 mM) and 6 μl (3 mM) MgCl2 for round 1 and 2, respectively, 1 μl (0.2 mM) dNTPs, 0.2 μl (0.4 μg/ml reaction) 10% bovine serum albumin (BSA), 0.5 μl (200 nM) of each primer at a concentration of 20 pmol/μl, 0.25 μl (1.25 U) HotStarTaq Plus polymerase, 3 μl and 5 μl DNA for round 1 and round 2, respectively, and PCR-grade water in a 50-μl total volume. Amplification conditions for the PCRs started with 95°C for 5 min and followed the settings previously described by Xiao et al. (28).

To allow sequence analysis at a second locus, Xiao 18S-positive samples were further processed to amplify a 550-bp DNA fragment using a modified Spano COWP PCR protocol (30). All PCR mixtures contained 5 μl (1×) 10× PCR buffer with 1.5 mM MgCl2, 3 μl (3 mM) MgCl2, 1 μl (0.2 mM) dNTPs, 0.2 μl (0.4 μg/ml reaction) 10% bovine serum albumin (BSA), 1.5 μl (200 nM) of each primer at a concentration of 20 pmol/μl, 0.25 μl (1.25 U) HotStarTaq Plus polymerase and 3 μl DNA, and PCR water in a 50-μl total volume. Amplification conditions for the PCRs started with 95°C for 5 min and followed the settings previously described by Spano et al. (30).

Genotype analysis of Giardia spp. in hemolymph, DFA-positive CSL feces, and DFA-positive mussel homogenate was based on two loci used for molecular characterization: the glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH) gene (31) and the beta-giardin gene (32). A 432-bp fragment was amplified using a modified GDH PCR protocol (31). The PCR mixtures contained 5 μl (1×) 10× PCR buffer with 1.5 mM MgCl2, 1 μl (0.2 mM) dNTPs, 0.2 μl (0.4 μg/ml reaction) 10% bovine serum albumin (BSA), 1.25 μl (25 pmol/reaction) of each primer at a concentration of 20 pmol/μl, 0.25 μl (1.25 U) HotStarTaq Plus polymerase and 3 μl and 1 μl DNA for round 1 and round 2, respectively, and PCR water in a 50-μl total volume. Amplification conditions for the PCRs started with 95°C for 5 min and followed the settings previously described by Read et al. (31).

For GDH-positive samples, a second DNA locus was targeted by amplifying a 384-bp DNA segment using a modified beta-giardin seminested-PCR protocol (32). All PCR mixtures contained 5 μl (1×) 10× PCR buffer with 1.5 mM MgCl2, 1 μl (0.2 mM) dNTPs, 0.2 μl (0.4 μg/ml reaction) 10% bovine serum albumin (BSA), 0.5 μl (200 nM) of each primer at a concentration of 20 pmol/μl, 0.25 μl (1.25 U) HotStarTaq Plus polymerase and 3 μl and 1 μl DNA for round 1 and round 2, respectively, and PCR water in a 50-μl total volume. Amplification conditions for the PCRs started with 95°C for 5 min followed by 33 cycles with thermocycler settings as previously described by Caccio et al. (32). The primer sequences for all PCR protocols used in this study are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Nucleotide sequences of PCR primers used to detect DNA of Cryptosporidium and Giardia species in mussel hemolymph and tissue homogenates and in sea lion feces

| Amplification target | PCR protocol | Primer | Primer sequence (5′–3′) | Length of final PCR product (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cryptosporidium spp. | Morgan 18S rRNAa | 18SF | AGTGACAAGAAATAACAATACAGG | 298 |

| 18SR | CCTGCTTTAAGCACTCTAATTTTC | |||

| Xiao 18S rRNAb,c | Xiao EF | TTCTAGAGCTAATACATGCG | 819–825 | |

| Xiao ERc | CCCATTTCCTTCGAAACAGGA | |||

| Xiao IF | GGAAGGGTTGTATTTATTAGATAAAG | |||

| Xiao IR | AAGGAGTAAGGAACAACCTCCA | |||

| Giardia spp. | Spano COWPd | Cry-15 EF | GTAGATAATGGAAGAGATTGTG | 550 |

| Cry-9 ER | GGACTGAAATACAGGCATTATCTTG | |||

| Cry-12 IF | CCAGATGGATTCAGATTATTGGG | |||

| Cry-14 IR | CTATCTTTTCACAACCACCGGATGGGC | |||

| GDHe | GDHeF | TCAACGTYAAYCGYGGYTTCCGT | 432 | |

| GDHiF | CAGTACAACTCYGCTCTCGG | |||

| GDHiR | GTTRTCCTTGCACATCTCC | |||

| Beta-giardinf | Caccio G7 eF | AAGCCCGACGACCTCACCCGCAGTGC | 384 | |

| Caccio G759 eiR | GAGGCCGCCCTGGATCTTCGAGACGAC |

Samples with amplified DNA bands matching the sizes described above for each PCR protocol were purified using either ExoSAP-IT (Affymetrix Inc., Cleveland, OH) or QIAquick (Qiagen Inc., Chatsworth, CA) PCR purification kits following the instructions of the manufacturer, and the samples were submitted to the UC core DNA Sequencing Facility for sequence analysis.

Phylogenetic analysis.

The ends of the forward and reverse DNA sequences were trimmed and then aligned using Codon Code aligner software (Codon Code Corporation, Centerville, MA). The amplified DNA sequences identified in CSL feces, mussel tissue homogenate, and mussel hemolymph were compared with GenBank reference sequences for Cryptosporidium and Giardia using BLAST (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) and Clustal X (33) software. The phylogenetic analysis was inferred based on Kimura 2-parameter distance estimates with 1,000 bootstrap replicates, and trees were constructed by using the Neighbor-Joining algorithm (34) implemented in MEGA 5.0 software (35).

Preliminary spiking studies were performed to evaluate assay sensitivity for parasite detection (data not shown). Previous CSL fecal samples and individual mussel hemolymph spiking experiments performed with oocysts of a C. parvum Iowa isolate (Harley Moon) passaged through calves and gerbil-passaged cysts of G. lamblia human isolate H-3 obtained from Waterborne Inc. (New Orleans, LA) showed that the minimum detection level in 5 g of feces by DFA was 10 oocysts or 10 cysts. For CSL fecal samples tested by PCR, the minimum detection limits were 10 oocysts by Morgan 18S rRNA, 10 oocysts by Xiao 18S rRNA, 100 oocysts with Spano COWP, and 1 cyst by GDH. For mussel hemolymph samples tested by PCR, the minimum detection limit was 1 oocyst or 1 cyst for all of primers used in this study.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

Nucleotide sequence data for isolates HW1 (GenBank accession no. KF294079 for the GDH gene and KF294078 for the beta-giardin gene), HW4 (GenBank accession no. KF294080), HS71 (GenBank accession no. KF294081), and HC216 (GenBank accession no. KF294082) are available under the indicated accession numbers.

RESULTS

Over the 2-year duration of the study, a total of 303 individual CSL fecal samples were collected and tested; of those fecal samples, 133 were collected from White Rock (86 during the dry season and 47 during the wet season), 113 were collected from Point Lobos State Reserve (58 during the dry season and 55 during the wet season), and 57 were collected from Año Nuevo Island (41 during the dry season and 16 during the wet season). Table 2 shows the prevalence of samples per site with oocysts and cysts that had the morphological features characteristic of Cryptosporidium and Giardia, respectively, and which were DFA positive. Cryptosporidium oocysts were detected in 8.3% of the individual CSL fecal samples (9.3% during the dry season and 6.4% during the wet season) collected from White Rock, 15% of the individual fecal samples (6.9% during the dry season and 23.6% during the wet season) collected from Point Lobos, and 3.5% of the individual fecal samples (2.4% during the dry season and 6.3% during the wet season) collected on Año Nuevo Island. Giardia cysts were detected in CSL fecal samples collected from White Rock, with a prevalence of 3.0% (3.5% during the dry season and 2.1% during the wet season).

TABLE 2.

Prevalence of Cryptosporidium- and Giardia-positive CSL fecal samples, individual mussel hemolymph samples, and pooled mussel tissue homogenates collected at sample sites along the central California coast

| Site | Season | % prevalence (no. of positive samples/no. of samples tested) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSL fecesa |

Hemolymphb |

Mussel homogenatec |

|||||

| Cryptosporidium | Giardia | Cryptosporidium | Giardia | Cryptosporidium | Giardia | ||

| White Rock | Dry | 9.3 (8/86) | 3.5 (3/86) | 0 (0/118) | 1.7 (2/118) | 0 (0/9) | 0 (0/9) |

| Wet | 6.4 (3/47) | 2.1 (1/47) | 0 (0/120) | 0 (0/120) | 0 (0/3) | 0 (0/3) | |

| Santa Rosa Creek | Dry | NAd | NA | 0 (0/121) | 0 (0/121) | 0 (0/12) | 0 (0/12) |

| Wet | NA | NA | 0 (0/120) | 0.8 (1/120) | 0 (0/3) | 0 (0/3) | |

| Point Lobos | Dry | 6.9 (4/58) | 0 (0/58) | 0 (0/121) | 0 (0/121) | 0 (0/9) | 0 (0/9) |

| Wet | 23.6 (13/55) | 0 (0/55) | 0 (0/90) | 0 (0/90) | 0 (0/3) | 0 (0/3) | |

| Carmel River | Dry | NA | NA | 0 (0/119) | 0 (0/119) | 0 (0/9) | 0 (0/9) |

| Wet | NA | NA | 0 (0/152) | 0.7 (1/152) | 0 (0/6) | 0 (0/6) | |

| Año Nuevo Island | Dry | 2.4 (1/41) | 0 (0/41) | NCe | NC | NC | NC |

| Wet | 6.3 (1/16) | 0 (0/16) | NC | NC | NC | NC | |

| Total collected | Dry | 7.0 (13/185) | 1.6 (3/185) | 0 (0/479) | 0.4 (2/479) | 0 (0/39) | 0 (0/39) |

| Wet | 14.4 (17/118) | 0.9 (1/118) | 0 (0/482) | 0.4 (2/482) | 0 (0/15) | 0 (0/15) | |

| Overall | 9.9 (30/303) | 1.3 (4/303) | 0 (0/961) | 0.4 (4/961) | 0 (0/54) | 0 (0/54) | |

Positive samples detected by direct fluorescent antibody (DFA) method.

Positive samples detected by PCR methods and confirmed by sequence analysis.

IMS- and DFA-positive aliquots of 4 g of mussel tissue homogenate.

NA, not applicable, as this site is not a CSL haul-out site.

NC, not collected due to low numbers of specimens in the area and unsafe sampling conditions.

Counts in Cryptosporidium- and Giardia-positive CSL fecal samples detected by DFA without IMS were under 10 oocysts/cysts per sample, except for three samples, one (>100 oocysts) from White Rock and another (98 oocysts) from Año Nuevo Island, both collected during the dry season, and the third one collected from Point Lobos during the wet season. Cryptosporidium DNA and Giardia DNA were not identified by IMS in combination with PCR in any of the CSL fecal samples.

Over the 2-year study, hemolymph was extracted from 961 mussels; of those mussels, 479 were collected during the dry season and 482 were collected during the wet season (Table 2). No hemolymph samples yielded positive results for Cryptosporidium DNA by PCR using the Morgan 18S rRNA (298-bp target) PCR protocol and the Xiao 18S rRNA nested (850-bp target)-PCR protocol. Table 2 shows the proportions of hemolymph samples that were positive for Giardia DNA per site by PCR.

Giardia DNA was identified by PCR amplification of GDH sequences that were confirmed by sequence analysis in 0.4% (4/961) of individual hemolymph samples. Only one of the most strongly GDH-positive samples (432-bp target) was also positive by beta-giardin PCR (384-bp target), a protocol that has been less sensitive previously. Among the 68 PCR products of amplification with GDH primers, BLAST searches in GenBank revealed 4 DNA sequences (isolates HW1, HW4, HS71, and HC216) that closely matched reference sequences for Giardia intestinalis, 6 DNA sequences that were more closely related to non-Giardia microorganisms, and 48 DNA sequences that gave mixed results. Of the three DNA sequences found to closely match the reference sequences for Giardia intestinalis, two of them (HW1 and HW4) were detected in hemolymph from mussels collected from White Rock during the dry season. Isolate HW4 was 96% similar to G. intestinalis assemblage D (GenBank accession number EF507636) by BLAST and Clustal X analysis, with only 13 mismatching nucleotides of a total of 421 nucleotides. The other GDH sequence (isolate HW1) was 97% similar to G. intestinalis assemblage C (GenBank accession numbers AB569390 and U60985) by BLAST and Clustal X, with only 9 mismatching nucleotides of a total of 425 nucleotides. This sample (isolate HW1) was also positive by beta-giardin PCR, and the DNA sequence was 99% similar to that of G. intestinalis assemblage D (GenBank accession numbers AY545647, HQ538708, HQ538709, and FJ009205) according to both BLAST and Clustal X, with only 1 mismatching nucleotide of a total of 313 nucleotides. The third GDH-amplified DNA sequence (isolate HS71) that closely matched the reference G. intestinalis sequence was detected in the hemolymph of mussels collected in Santa Rosa Creek during the wet season. The sequence similarity to G. intestinalis assemblage B (GenBank accession numbers AY178749, AY178750, HM134215, and EU594666) was 100% by BLAST and 99.8% by Clustal X, with only 1 mismatching nucleotide of a total of 411 nucleotides. The fourth GDH-amplified DNA sequence (isolate HC216) that closely matched reference G. intestinalis was detected in the hemolymph of a mussel collected near Carmel River during the wet season. This sequence was 100% similar to G. intestinalis assemblage D (GenBank accession numbers EF507619, JX448631, and U60986) by both BLAST and Clustal X, with no mismatching nucleotides of a total of 407 nucleotides.

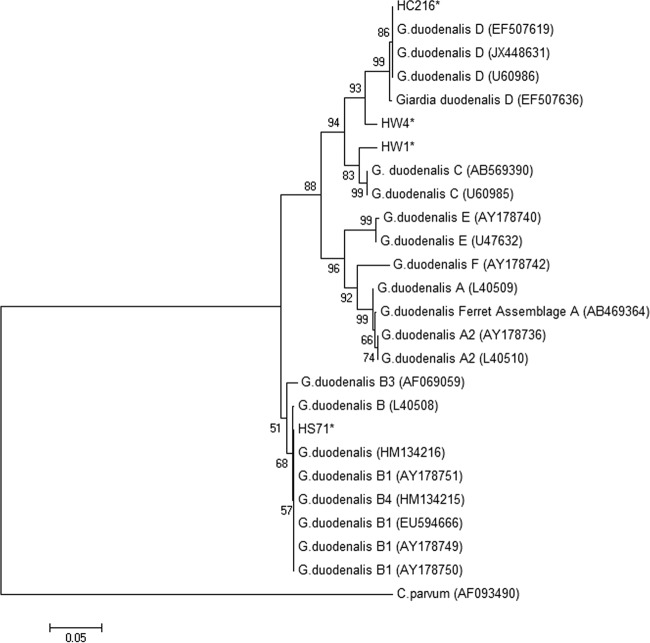

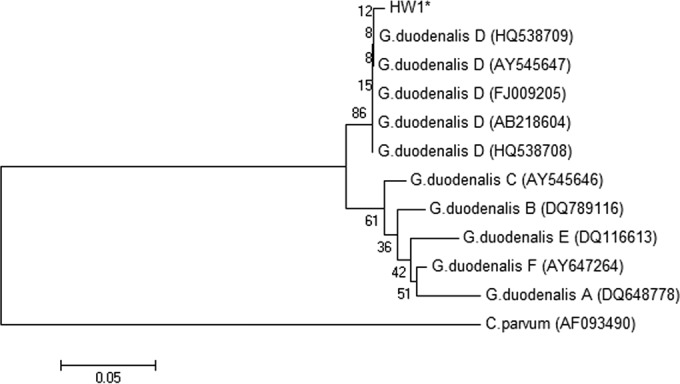

Giardia DNAs identified in hemolymph samples were uploaded to the GenBank database. Figures 2 and 3 show the phylogenetic analyses of isolates HW1 (assemblage C at the GDH gene; GenBank accession no. KF294079; assemblage D at the beta-giardin gene; accession no. KF294078) and HW4 (assemblage D; GenBank accession no. KF294080) obtained from mussels at the White Rock study site, as well as isolates HS71 (assemblage B; GenBank accession no. KF294081) and HC216 (assemblage D; GenBank accession no. KF294082) detected in mussels from Santa Rosa Creek, CA, and Carmel, CA, respectively. Isolates HW1, HW4, HS71, and HC216 were not all exact matches to reference sequences but were classified within the Giardia clade, with HW1 most closely related to G. duodenalis assemblage C based on the GDH locus (Fig. 2) and located in the same clade as G. intestinalis assemblage D based on the beta-giardin locus (Fig. 3). As shown in Fig. 2, HW4 and HC216 were most closely related to G. duodenalis assemblage D and HS71 was most closely related to G. duodenalis assemblage B with the GDH locus.

FIG 2.

Phylogenetic analysis of Giardia duodenalis sequences detected in hemolymph from mussels based on the nucleotide sequence at the GDH locus and using a neighbor-joining Kimura 2-parameter method. (GenBank reference accession numbers are shown in parentheses.) *, isolates detected in hemolymph from mussels in this study.

FIG 3.

Phylogenetic analysis of Giardia duodenalis sequences detected in hemolymph from mussels based on the nucleotide sequence at the beta-giardin locus and using a neighbor-joining Kimura 2-parameter method. (GenBank reference accession numbers are shown in parentheses.) *, isolate detected in hemolymph from mussels in this study.

DISCUSSION

In this study, hemolymph and tissue homogenates collected from filter-feeding mussels and fecal samples from California sea lions at two study sites along the central coast of California were tested for Cryptosporidium and Giardia spp. Notably, DNAs of Giardia duodenalis assemblages B and D were detected in the hemolymph of mussels located near land runoff sites, at Santa Rosa Creek and Carmel River, and DNAs of assemblages C and D were detected in the hemolymph of mussels collected near the CSL haul-out site at White Rock. In addition, the presence of G. duodenalis assemblage B, which is known to have zoonotic potential, provided evidence of a potential health risk to beachgoers and surfers, particularly during the wet season, when river runoff is high due to rainfall. Rainfall can result in mobilization of fecal material from land and subsequent discharge into rivers, increasing the concentration of fecal pathogens and exposure of both mussels and mammals, including humans, to these pathogens (29, 36). G. duodenalis assemblages C and D that were identified in mussels collected at the CSL haul-out site can also have implications for public health, as they have been shown to be infectious to humans (37), though they appear to be most commonly shed by domestic and wild canids. Although Giardia-like cysts were observed in CSL feces in this study, their genotypes were not identified, so the source of the G. duodenalis DNA in the mussels collected at haul-out sites could not be confirmed.

The molecular characterization of Giardia in mussels in this study affirms the usefulness of testing filter-feeding shellfish, such as mussels, that can concentrate protozoan parasites and other pathogens in aquatic environments (21, 22, 38–41). Unlike the present study results, however, the predominant protozoan parasite reported by previous authors was Cryptosporidium, most notably C. parvum. In our study, Giardia was molecularly identified and characterized from mussel hemolymph, whereas Cryptosporidium was not confirmed using PCR methods with sequence analysis in any of the mussel hemolymph samples collected. The low prevalence of Giardia and lack of detection of Cryptosporidium in the hemolymph samples tested in this study might be explained by the fact that the concentration of cysts and oocysts coming from river outflow was diluted as fecally contaminated water was discharged into the sea; thus, despite the ability of mussels to concentrate these parasite stages, the levels were often lower than our detection limits. The low number of positive samples in mussels could also have been due to the fact that both wet seasons during which mussels were sampled were low in total rainfall and the fact that our sampling occurred late in the wet season (around April in 2012). Another possible explanation for the low prevalence of these protozoan parasites in the hemolymph samples is that prior studies have demonstrated that bivalves depurate the pathogens concentrated from surrounding water over the following days or weeks (17). Most of our bivalve sampling did not occur immediately after storm events, when bivalves would be most likely to retain higher pathogen concentrations and are most useful as bioindicators (42).

In the present study, there was a discrepancy between the sequence analysis results obtained with the GDH and the beta-giardin PCR protocols for the amplification of Giardia DNA. Analysis at the GDH locus revealed that isolate HW1 was related to G. duodenalis assemblage C; in contrast, the beta-giardin locus suggested that this isolate was related to G. duodenalis assemblage D. Similar mixed multilocus genotyping results were reported in three other studies (43–45) and deserve further molecular epidemiologic investigation. Additionally, amplified DNA sequences of isolates HW4, HS71, and HC216 were detected using the GDH PCR protocol but not with the beta-giardin PCR protocol. Nantavisai et al. (46) spiked stool samples with known numbers of Giardia cysts to assess the sensitivities of different Giardia PCR methods and obtained better recovery efficiencies by the use of the GDH locus than by the use of the beta-giardin locus.

Very few studies have investigated the presence of Cryptosporidium oocysts and Giardia cysts in fecal samples from CSLs in the wild. In a previous study, Deng et al. (15) identified and molecularly characterized C. parvum and Giardia duodenalis in fresh fecal samples collected from stranded CSLs in a marine animal recovery and rehabilitation facility. These CSL could have been more extensively exposed to infection as they were in contact with humans and other terrestrial animals and could also have been more susceptible due to stress or illness, causing the CSL to shed sufficient oocysts and cysts for the detection of DNA by PCR. In the present study, CSL fecal samples came from haul-out sites where the animals were apparently healthy and free-ranging; under these circumstances, however, feces could not be collected immediately after defecation, which could explain the low counts detected for both species of protozoa. Another possible explanation for the low counts detected in our study is that the CSL fecal samples were collected approximately every 3 months, which could have reduce the likelihood of detecting higher counts of oocysts and cysts, as oocysts and cysts have an intermittent shedding pattern in feces (8). Nonetheless, fresh samples were collected and the presence detected of oocysts and cysts with the morphological features characteristic of Cryptosporidium spp. and Giardia spp. in fecal samples from wild CSLs at White Rock and Point Lobos, along with the identification of Giardia DNA in hemolymph of mussels collected at the CSL haul-out site at White Rock. Unfortunately, it was not possible to confirm by genotype analysis the identification of isolates of both Cryptosporidium-like oocysts and Giardia-like cysts in the feces of CSL. The lack of amplification of DNA sequences for Cryptosporidium and Giardia could have been due to the low number of oocysts and cysts detected in the fecal samples. The detection of oocysts and cysts with the morphological features characteristic of Cryptosporidium spp. and Giardia spp. in fecal samples from wild CSLs suggests that CSLs may serve as a source of these protozoan parasites and might be contributors of the parasite load discharged in their natural marine environment. Further studies are needed to better understand the role of CSL as the host of Cryptosporidium and Giardia in marine environs, including genotyping and viability studies of protozoa detected in CSL feces.

Conclusions.

In summary, detection of G. duodenalis assemblages B, C, and D in the hemolymph of mussels sampled near freshwater runoff and CSL haul-out sites in coastal California confirmed the usefulness of testing shellfish that are capable of concentrating protozoans from marine environments and is consistent with terrestrial sources for these fecally transmitted, waterborne parasites flowing from land to sea. The detection of G. duodenalis assemblage B in mussels collected near land runoff in Carmel is noteworthy, as this assemblage is known to be infectious to humans and thus may pose public health risks. Detection of G. duodenalis assemblages C and D in mussels collected in CSL haul-out sites provides evidence of their presence in the waters surrounding haul-out sites. Overall, the results of this study support the hypothesis that the same genotypes found in terrestrial animals can be found in mussels; however, further molecular studies are needed to ascertain whether CSL fecal samples have the same genotypes as those found in terrestrial animals.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge the financial support received from the “Presidente de la República” Chilean scholarship, the Central Coast Long-term Environmental Assessment Network (CCLEAN) (grant no. 06-076-553) from the California State Water Board to the City of Watsonville, the National Science Foundation (NSF) Ecology of Infectious Disease Grant Program (grant no. OCE-1065990), the UC Davis Graduate Student Support Program (GSSP), and a UC Davis Graduate group in Comparative Pathology Block Grant.

Thanks are due to the field teams that supported collections of mussels, and we specifically acknowledge Tim Tinker, Joe Tomoleoni, Jim Webb, Ben Weitzman, Don Canestro, Miles Daniels, Mark Kocina, Colin Krusor, Zach Randell, and Matt Smith. Collection of mussels from the sites in Cambria was facilitated through the University of California Ken Norris Rancho Marino Reserve. Thanks are also due to Chuck Bancroft, Sean James, and Erik Abma and to Patricia Morris for facilitating collection of CSL fecal samples at Point Lobos State Reserve and Año Nuevo Island, respectively.

We are also grateful to the laboratory team that assisted in the processing of the mussels and specifically acknowledge Beatriz Aguilar, Andrea Packham, Terra Berardi, Heather Fritz, Leopoldo Guerrero, Kaitlyn Hanley, Claudia Llerandi, Lauren Michaels, and Anna Naranjo.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 3 October 2014

REFERENCES

- 1.Haas CN, Rose JB, Gerba CP. 1999. Quantitative microbial risk assessment. John Wiley & Sons, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Acha P, Szyfres B. 2003. Zoonosis y enfermedades transmisibles comunes al hombre y a los hombres animales, p 25–26, 47, 49 In Parasitosis, vol 3 Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fayer R, Xiao L. 2008. Cryptosporidium and cryptosporidiosis. Taylor & Francis Group, Boca Raton, FL. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miller MA, Gardner IA, Kreuder C, Paradies DM, Worcester KR, Jessup DA, Dodd E, Harris MD, Ames JA, Packham AE, Conrad PA. 2002. Coastal freshwater runoff is a risk factor for Toxoplasma gondii infection of southern sea otters (Enhydra lutris nereis). Int. J. Parasitol. 32:997–1006. 10.1016/S0020-7519(02)00069-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Conrad PA, Miller MA, Kreuder C, James ER, Mazet J, Dabritz H, Jessup DA, Gulland F, Grigg ME. 2005. Transmission of Toxoplasma: clues from the study of sea otters as sentinels of Toxoplasma gondii flow into the marine environment. Int. J. Parasitol. 35:1155–1168. 10.1016/j.ijpara.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miller MA, Byrne BA, Jang SS, Dodd EM, Dorfmeier E, Harris MD, Ames J, Paradies D, Worcester K, Jessup DA, Miller WA. 2010. Enteric bacterial pathogen detection in southern sea otters (Enhydra lutris nereis) is associated with coastal urbanization and freshwater runoff. Vet. Res. 41:1. 10.1051/vetres/2009049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rendtorff RC. 1954. The experimental transmission of human intestinal protozoan parasites. II. Giardia lamblia cysts given in capsules. Am. J. Hyg. 59:209–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chappell CL, Okhuysen PC, Sterling CR, DuPont HL. 1996. Cryptosporidium parvum: intensity of infection and oocyst excretion patterns in healthy volunteers. J. Infect. Dis. 173:232–236. 10.1093/infdis/173.1.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nydam DV, Wade SE, Schaaf SL, Mohammed HO. 2001. Number of Cryptosporidium parvum oocysts or Giardia spp cysts shed by dairy calves after natural infection. Am. J. Vet. Res. 62:1612–1615. 10.2460/ajvr.2001.62.1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Castro-Hermida JA, Almeida A, Gonzalez-Warleta M, Correia da Costa JM, Rumbo-Lorenzo C, Mezo M. 2007. Occurrence of Cryptosporidium parvum and Giardia duodenalis in healthy adult domestic ruminants. Parasitol. Res. 101:1443–1448. 10.1007/s00436-007-0624-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.deRegnier D, Cole L, Schupp D, Erlandsen S. 1989. Viability of Giardia cysts suspended in lake, river, and tap water. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 55:1223–1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robertson LJ, Campbell AT, Smith HV. 1992. Survival of Cryptosporidium parvum oocysts under various environmental pressures. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 58:3494–3500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Graczyk TK, Fayer R, Lewis EJ, Trout JM, Farley CA. 1999. Cryptosporidium oocysts in Bent mussels (Ischadium recurvum) in the Chesapeake Bay. Parasitol. Res. 85:518–521. 10.1007/s004360050590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Graczyk TK, Lewis EJ, Glass G, Dasilva AJ, Tamang L, Girouard AS, Curriero FC. 2007. Quantitative assessment of viable Cryptosporidium parvum load in commercial oysters (Crassostrea virginica) in the Chesapeake Bay. Parasitol. Res. 100:247–253. 10.1007/s00436-006-0261-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deng MQ, Peterson RP, Cliver DO. 2000. First findings of Cryptosporidium and Giardia in California sea lions (Zalophus californianus). J. Parasitol. 86:490–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McMahon RD. 1991. Mollusca: bivalvia, p 315–401 In Thorp JH, Covich AP. (ed), Ecology and classification of North American freshwater invertebrates. Academic Press, San Diego, CA. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miller WA, Atwill ER, Gardner IA, Miller MA, Fritz HM, Hedrick RP, Melli AC, Barnes NM, Conrad PA. 2005. Clams (Corbicula fluminea) as bioindicators of fecal contamination with Cryptosporidium and Giardia spp. in freshwater ecosystems in California. Int. J. Parasitol. 35:673–684. 10.1016/j.ijpara.2005.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robertson LJ. 2007. The potential for marine bivalve shellfish to act as transmission vehicles for outbreaks of protozoan infections in humans: a review. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 120:201–216. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2007.07.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Freire-Santos F, Oteiza-Lopez AM, Vergara-Castiblanco CA, Ares-Mazas E, Alvarez-Suarez E, Garcia-Martin O. 2000. Detection of Cryptosporidium oocysts in bivalve molluscs destined for human consumption. J. Parasitol. 86:853–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fayer R, Trout JM, Lewis EJ, Xiao L, Lal A, Jenkins MC, Graczyk TK. 2002. Temporal variability of Cryptosporidium in the Chesapeake Bay. Parasitol. Res. 88:998–1003. 10.1007/s00436-002-0697-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lucy FE, Graczyk TK, Tamang L, Miraflor A, Minchin D. 2008. Biomonitoring of surface and coastal water for Cryptosporidium, Giardia, and human-virulent microsporidia using molluscan shellfish. Parasitol. Res. 103:1369–1375. 10.1007/s00436-008-1143-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miller WA, Miller MA, Gardner IA, Atwill ER, Harris M, Ames J, Jessup D, Melli A, Paradies D, Worcester K, Olin P, Barnes N, Conrad PA. 2005. New genotypes and factors associated with Cryptosporidium detection in mussels (Mytilus spp.) along the California coast. Int. J. Parasitol. 35:1103–1113. 10.1016/j.ijpara.2005.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holloway JM, Dahlgren RA, Hansen B, Casey WH. 1998. Contribution of bedrock nitrogen to high nitrate concentrations in stream water. Nature 395:785–788. 10.1038/27410. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dabritz HA, Miller MA, Atwill ER, Gardner IA, Leutenegger CM, Melli AC, Conrad PA. 2007. Detection of Toxoplasma gondii-like oocysts in cat feces and estimates of the environmental oocyst burden. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 231:1676–1684. 10.2460/javma.231.11.1676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marks SL, Hanson TE, Melli AC. 2004. Comparison of direct immunofluorescence, modified acid-fast staining, and enzyme immunoassay techniques for detection of Cryptosporidium spp in naturally exposed kittens. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 225:1549–1553. 10.2460/javma.2004.225.1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miller WA, Gardner IA, Atwill ER, Leutenegger CM, Miller MA, Hedrick RP, Melli AC, Barnes NM, Conrad PA. 2006. Evaluation of methods for improved detection of Cryptosporidium spp. in mussels (Mytilus californianus). J. Microbiol. Methods 65:367–379. 10.1016/j.mimet.2005.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morgan UM, Constantine CC, Forbes DA, Thompson RC. 1997. Differentiation between human and animal isolates of Cryptosporidium parvum using rDNA sequencing and direct PCR analysis. J. Parasitol. 83:825–830. 10.2307/3284275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xiao L, Morgan UM, Limor J, Escalante A, Arrowood M, Shulaw W, Thompson RC, Fayer R, Lal AA. 1999. Genetic diversity within Cryptosporidium parvum and related Cryptosporidium species. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:3386–3391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xiao L, Alderisio K, Limor J, Royer M, Lal AA. 2000. Identification of species and sources of Cryptosporidium oocysts in storm waters with a small-subunit rRNA-based diagnostic and genotyping tool. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:5492–5498. 10.1128/AEM.66.12.5492-5498.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Spano F, Putignani L, McLauchlin J, Casemore DP, Crisanti A. 1997. PCR-RFLP analysis of the Cryptosporidium oocyst wall protein (COWP) gene discriminates between C. wrairi and C. parvum, and between C. parvum isolates of human and animal origin. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 150:209–217. 10.1016/S0378-1097(97)00115-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Read CM, Monis PT, Thompson RC. 2004. Discrimination of all genotypes of Giardia duodenalis at the glutamate dehydrogenase locus using PCR-RFLP. Infect. Genet. Evol. 4:125–130. 10.1016/j.meegid.2004.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cacciò SM, De Giacomo M, Pozio E. 2002. Sequence analysis of the beta-giardin gene and development of a polymerase chain reaction-restriction fragment length polymorphism assay to genotype Giardia duodenalis cysts from human faecal samples. Int. J. Parasitol. 32:1023–1030. 10.1016/S0020-7519(02)00068-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Plewniak F, Jeanmougin F, Higgins DG. 1997. The CLUSTAL_X windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:4876–4882. 10.1093/nar/25.24.4876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Solarczyk P, Majewska AC. 2010. A survey of the prevalence and genotypes of Giardia duodenalis infecting household and sheltered dogs. Parasitol. Res. 106:1015–1019. 10.1007/s00436-010-1766-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. 2011. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol. Biol. Evol. 28:2731–2739. 10.1093/molbev/msr121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miller WA, Lewis DJ, Pereira MD, Lennox M, Conrad PA, Tate KW, Atwill ER. 2008. Farm factors associated with reducing Cryptosporidium loading in storm runoff from dairies. J. Environ. Qual. 37:1875–1882. 10.2134/jeq2007.0413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Traub RJ, Inpankaew T, Reid SA, Sutthikornchai C, Sukthana Y, Robertson ID, Thompson RC. 2009. Transmission cycles of Giardia duodenalis in dogs and humans in Temple communities in Bangkok–a critical evaluation of its prevalence using three diagnostic tests in the field in the absence of a gold standard. Acta Trop. 111:125–132. 10.1016/j.actatropica.2009.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gomez-Bautista M, Ortega-Mora LM, Tabares E, Lopez-Rodas V, Costas E. 2000. Detection of infectious Cryptosporidium parvum oocysts in mussels (Mytilus galloprovincialis) and cockles (Cerastoderma edule). Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66:1866–1870. 10.1128/AEM.66.5.1866-1870.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gómez-Couso H, Freire-Santos F, Amar CF, Grant KA, Williamson K, Ares-Mazás ME, McLauchlin J. 2004. Detection of Cryptosporidium and Giardia in molluscan shellfish by multiplexed nested-PCR. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 91:279–288. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2003.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gómez-Couso H, Méndez-Hermida F, Ares-Mazás E. 2006. Levels of detection of Cryptosporidium oocysts in mussels (Mytilus galloprovincialis) by IFA and PCR methods. Vet. Parasitol. 141:60–65. 10.1016/j.vetpar.2006.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li X, Guyot K, Dei-Cas E, Mallard JP, Ballet JJ, Brasseur P. 2006. Cryptosporidium oocysts in mussels (Mytilus edulis) from Normandy (France). Int. J. Food Microbiol. 108:321–325. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2005.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Applied Marine Sciences Inc, Davis UC, California Department of Fish and Game Marine Wildlife Veterinary Care & Research Center. 2011. Monitoring and mitigation to address fecal pathogen pollution along California coast. Proposition 50 Coastal Management Program California State Water Board agreement no. 06-076-553. California Department of Fish and Wildlife. http://www.cclean.org/ftp/Prop50%20Fecal%20Pathogen%20Final%20Report%20copy.pdf.

- 43.Abe N, Read C, Thompson RC, Iseki M. 2005. Zoonotic genotype of Giardia intestinalis detected in a ferret. J. Parasitol. 91:179–182. 10.1645/GE-3405RN. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Robertson LJ, Forberg T, Hermansen L, Hamnes IS, Gjerde B. 2007. Giardia duodenalis cysts isolated from wild moose and reindeer in Norway: genetic characterization by PCR-rflp and sequence analysis at two genes. J. Wildl. Dis. 43:576–585. 10.7589/0090-3558-43.4.576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Siembieda JL, Miller WA, Byrne BA, Ziccardi MH, Anderson N, Chouicha N, Sandrock CE, Johnson CK. 2011. Zoonotic pathogens isolated from wild animals and environmental samples at two California wildlife hospitals. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 238:773–783. 10.2460/javma.238.6.773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nantavisai K, Mungthin M, Tan-ariya P, Rangsin R, Naaglor T, Leelayoova S. 2007. Evaluation of the sensitivities of DNA extraction and PCR methods for detection of Giardia duodenalis in stool specimens. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45:581–583. 10.1128/JCM.01823-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]