Abstract

Alternative sigma (σ) factors and phosphotransferase systems (PTSs) play pivotal roles in the environmental adaptation and virulence of Listeria monocytogenes. The growth of the L. monocytogenes parent strain 10403S and 15 isogenic alternative σ factor mutants was assessed in defined minimal medium (DM) with PTS-dependent or non-PTS-dependent carbon sources at 25°C or 37°C. Overall, our results suggested that the regulatory effect of alternative σ factors on the growth of L. monocytogenes is dependent on the temperature and the carbon source. One-way analysis of variance (one-way ANOVA) showed that the factor “strain” had a significant effect on the maximum growth rate (μmax), lag phase duration (λ), and maximum optical density (ODmax) in PTS-dependent carbon sources (P < 0.05) but not in a non-PTS-dependent carbon source. Also, the ODmax was not affected by strain for any of the three PTS-dependent carbon sources at 25°C but was affected by strain at 37°C. Monitoring by quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) showed that transcript levels for lmo0027, a glucose-glucoside PTS permease (PTSGlc-1)-encoding gene, were higher in the absence of σL, and lower in the absence of σH, than in the parent strain. Our data thus indicate that σL negatively regulates lmo0027 and that the increased μmax observed for the ΔsigL strain in DM with glucose may be associated with increased expression of PTSGlc-1 encoded by lmo0027. Our findings suggest that σH and σL mediate the PTS-dependent growth of L. monocytogenes through complex transcriptional regulations and fine-tuning of the expression of specific pts genes, including lmo0027. Our findings also reveal a more important and complex role of alternative σ factors in the regulation of growth in different sugar sources than previously assumed.

INTRODUCTION

The facultatively intracellular pathogen Listeria monocytogenes has a “Jekyll and Hyde” lifestyle (1). L. monocytogenes can effectively adapt to environmental conditions outside the eukaryotic host cells and can multiply using various carbon sources. The transition of L. monocytogenes from an extracellular saprophyte to an intracellular parasite is modulated mainly by the activation of the master virulence regulatory protein PrfA, triggered by a variety of environmental cues, such as carbon source and temperature (2, 3). PrfA is activated in host cells but remains inactive in broth cultures. While the mechanisms of regulation of PrfA activity are not fully understood (4, 5), carbon sources may serve as an environmental signal for L. monocytogenes to switch between the life cycle of an extracellular saprophyte and that of an intracellular pathogen (6). Specifically, when the bacterium is outside the host cell, extracellular carbon sources, such as glucose and cellobiose, are transported by phosphoenol pyruvate (PEP)-dependent phosphotransferase systems (PTSs) (7). In the presence of active PTSs, the activity of PrfA appears to be downregulated through complex regulatory interactions (2, 8) that are not yet fully elucidated. In contrast, L. monocytogenes can utilize non-PTS-dependent carbon sources available in the cytoplasm of eukaryotic cells, such as phosphorylated glucose and glycerol, for intracellular growth (9). PrfA is thus activated in the absence of active PTSs (10). By in silico analysis, Stoll and Goebel have identified 86 genes encoding 29 complete PTSs and 10 single PTS components (11). Among these, two mannose-fructose-sorbose PTS permeases, PTSMan-2 (encoded by lmo0096 to lmo0098) and PTSMan-3 (encoded by lmo0781 to lmo0784), as well as a glucose-glucoside PTS permease (PTSGlc-1, encoded by lmo0027), have been found to play key roles in glucose transportation in L. monocytogenes EGD-e (11).

Alternative σ factors play key roles in the adaptation of L. monocytogenes to changing environmental conditions (12). Under certain environmental conditions, alternative σ factors reprogram the RNA polymerase holoenzyme to recognize specific promoters and hence allow for rapid induction of the transcription of stress response and virulence genes (12). Four alternative σ factors (σB, σC, σH, and σL) have been identified in L. monocytogenes. A number of studies on σB have demonstrated that this alternative σ factor controls a large regulon and contributes both to the stress response and to the virulence of L. monocytogenes (12–17). σB has been shown to positively regulate at least one PTS-encoding operon, lmo0781 to lmo0784 (PTSMan-3), which has been suggested to play an important role in the regulation of PrfA activity (18). However, σH, σL, and σC have not been as extensively characterized. A transcriptomic analysis of the L. monocytogenes parent strain EGD-e and an isogenic sigL deletion mutant indicated that σL controls the expression of genes encoding four PTSs and thus controls carbohydrate metabolism via direct regulation of PTS activity (19). Proteomics using strain 10403S and isogenic mutants have also shown that σL positively regulates the expression of PTSMan-2, another PTS suggested to play a key role in the activation of PrfA (18), and negatively regulates the expression of other PTSs, such as those encoded by lmo0027 (PTSGlc-1) and lmo2097 to lmo2098 (PTSGat-2) (20). Chaturongakul et al. identified 51 and 169 genes as differentially regulated by σL and σH, respectively, including 8 and 3 genes encoding components of PTSs (14). An L. monocytogenes EGD-e ΔsigH strain showed significantly impaired growth in minimal medium as well as slightly reduced virulence potential in a murine model (21). Through proteomics, Mujahid et al. identified three PTS components positively regulated by σH: (i) PTSGlc-1, encoded by lmo0027; (ii) one component of PTSMan-2, encoded by lmo0096; and (iii) PTSGlc (EIIBC), encoded by lmo1255 (20). Moreover, a σH-dependent promoter was identified 54 nucleotides upstream of the start codon of lmo0027, suggesting that σH may directly regulate the expression of this gene (20). σC has been described only for L. monocytogenes strains belonging to lineage II, and studies conducted to date on the σC regulon identified a few pts genes as σC dependent (14, 20, 22). Furthermore, considerable overlap has been found between different L. monocytogenes alternative σ factor regulons (14, 20).

The previous studies collectively suggest that alternative σ factors other than σB may play an important role in the environmental adaptation and/or virulence of L. monocytogenes through the regulation of specific pts genes. To more precisely characterize the significance of alternative σ factors and PTSs for listerial carbon utilization and pathogenesis, we assessed the growth of L. monocytogenes 10403S and 19 isogenic alternative σ factor and/or pts gene mutants in PTS-dependent and non-PTS-dependent carbon sources at either 25°C or 37°C.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

L. monocytogenes 10403S and the 19 isogenic mutant strains used in this study (Table 1) were stored at −80°C in brain heart infusion broth (BHIB) (Becton Dickinson, Sparks, MD) with 15% glycerol (IBI Scientific, Peosta, IA). In preparation for the experiments, isolates were streaked onto brain heart infusion agar (BHIA) from frozen stocks and were incubated at 37°C for 24 h. A single colony was transferred to 5 ml BHIB and was incubated at 37°C with shaking (230 rpm) for 18 h, followed by transfer of a 1% inoculum to 5 ml BHIB. After growth to early-exponential phase (defined as an optical density at 600 nm [OD600] of 0.4), 2 μl of a 0.01% inoculum was transferred to a 100-well honeycomb plate (Oy Growth Curves AB, Raisio, Finland) containing 198 μl prewarmed (37°C) chemically defined L. monocytogenes minimal medium (DM) (23) in each well. DM was supplemented with one of the following carbon sources at a final concentration of 10 mM: glucose (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), mannose (Sigma), cellobiose (Sigma), or glycerol. The carbon sources were added to the medium at the required final concentrations, followed by filter sterilization.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmid used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| FSL X1-001 | Parent strain 10403S | 38 |

| FSL A1-254 | ΔsigB | 39 |

| FSL B2-124 | ΔsigL | 28 |

| FSL C3-126 | ΔsigH | 28 |

| FSL C3-113 | ΔsigC | 28 |

| FSL C3-119 | ΔsigB ΔsigC | This study |

| FSL C3-123 | ΔsigB ΔsigH | This study |

| FSL B2-127 | ΔsigB ΔsigL | This study |

| FSL C3-124 | ΔsigC ΔsigH | This study |

| FSL B2-129 | ΔsigC ΔsigL | This study |

| FSL B2-130 | ΔsigH ΔsigL | This study |

| FSL C3-139 | ΔsigC ΔsigH ΔsigL | This study |

| FSL C3-128 | ΔsigB ΔsigC ΔsigH | 20 |

| FSL C3-137 | ΔsigB ΔsigC ΔsigL | 20 |

| FSL C3-138 | ΔsigB ΔsigH ΔsigL | 20 |

| FSL C3-135 | ΔsigB ΔsigC ΔsigH ΔsigL | 20 |

| FSL B2-392 | ΔsigH ΔsigL Δlmo0027 | This study |

| FSL B2-393 | ΔsigL Δlmo0027 | This study |

| FSL B2-394 | Δlmo0027 | This study |

| FSL B2-395 | ΔsigH Δlmo0027 | This study |

| Plasmid pSW1 | Δlmo0027 | This study |

The 100-well honeycomb plates were incubated in the Bioscreen C automated turbidimetric system (Growth Curves USA, Piscataway, NJ) at 25°C or 37°C. OD measurements were taken every 10 min using the wide-band filter (420 to 580 nm) of the instrument for a total of 72 h. Growth parameters were determined in duplicate wells in two independent replications. Additionally, spread plating was used to determine the growth parameters of the parent strain 10403S and the ΔsigH, ΔsigL, and ΔsigH ΔsigL mutants in DM supplemented with glucose, cellobiose, or glycerol at a final concentration of 10 mM. Briefly, early-exponential-phase cell cultures were diluted in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) and transferred to 5 ml DM to reach a final level of approximately 1 × 103 CFU per milliliter. Cultures were sampled every 12 h for 96 h. Samples were diluted in PBS and were plated onto BHIA using an Autoplate 4000 system (Spiral Biotech, Bethesda, MD). Plates were incubated at 37°C for 24 h before enumeration of colonies with a Q-Count system (Spiral Biotech). Growth was monitored for three independent replicates of each strain with each carbon source.

Growth parameters and statistical analyses.

Optical-density-based growth curves were fitted by the Gompertz model using the grofit package, version 1.0, in R, version 2.13.1 (24), to estimate the lag phase duration (λ), maximum growth rate (μmax), and maximum optical density (ODmax). One-way analysis of variance (one-way ANOVA) was used to examine the effect of strain on the growth parameters for a given temperature and carbon source. Linear regression models were subsequently applied to the data by using the presence of the genes encoding alternative σ factors as predictors of the response variables (i.e., λ, μmax, and ODmax) for each of the four carbon sources (cellobiose, mannose, glucose, and glycerol). The models were created using the lm function, while the stepAIC function from the MASS package in R, version 2.13.1, was used with both the forward and backward algorithms to identify the best model. Confidence intervals at an α value of 0.05 (95% CI) were estimated using the “predict” function.

For plate count data, the growth parameters of each strain in each carbon source were estimated using the Baranyi model without λ (25) implemented in the NLStools package, version 0.0-11, in R, version 2.13.1. Plate counts (in CFU per milliliter) for each strain at every time point were log transformed and were used to estimate the μmax and maximum cell density (Nmax) values. Differences among the strains and carbon sources were analyzed with a separate fixed-effect ANOVA for each growth parameter. The linear model used for ANOVA included the strain and carbon source as fixed effects. ANOVA and a post hoc Tukey test were performed with JMP Pro, version 9.0.2 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC). Adjusted P values of <0.05 were considered significant.

RNA isolation and quantitative PCR (qPCR).

RNA was extracted from cultures of strain 10403S and its isogenic ΔsigL, ΔsigH, and ΔsigH ΔsigL mutants after growth in DM with 10 mM glucose at 37°C to an OD600 of 0.4. Total RNA was extracted using the PowerSoil total-RNA isolation kit (Mo Bio, Carlsbad, CA) by following the manufacturer's protocol. After extraction, RNA was treated with DNase I (Invitrogen, Foster City, CA), followed by purification with RNeasy minicolumns (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). RNA quality was assessed on a Bioanalyzer system (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA), and samples with an RNA integrity number (RIN) of >8.0 were used for subsequent analyses.

cDNA was synthesized from 500 ng total RNA using 4 μl qScript cDNA SuperMix (5×) (Quanta Biosciences, Gaithersburg, MD) in a reaction mixture with a total volume of 20 μl. Reverse transcription reactions were carried out under the following conditions: 5 min at 25°C, 30 min at 42°C, 5 min at 85°C, and a hold at 4°C. Tenfold serial dilutions of cDNA were used as the input for qPCR assays. RNA samples without 10-fold dilution and reverse transcription were used to determine background levels of DNA. Primer sequences for lmo0027 and rpoB were taken from previous studies (26, 27). The qPCR mixtures contained 10 μl PerfeCTa SYBR green FastMix (2×) (Quanta Biosciences), 500 nmol (each) primer, and 5 μl of the template and were run on the CFX96 system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) under the following conditions: 40 cycles at 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 1 min. The threshold cycle (CT) and reaction efficiencies were determined using CFX Manager software (Bio-Rad). Quantitative PCRs were carried out in duplicate for each cDNA sample tested. Target gene copy numbers were determined using genomic DNA standard curves and were normalized to copy numbers of rpoB. The ratios of normalized lmo0027 transcript levels for the ΔsigH, ΔsigL, and ΔsigH ΔsigL strains to transcript levels for the parent strain 10403S were calculated.

Mutant construction.

In-frame deletion mutations of lmo0027 were constructed in the 10403S, 10403S ΔsigH, 10403S ΔsigL, and 10403S ΔsigH ΔsigL backgrounds, using the splicing by overlap extension (SOE) method and the pKSV-7 vector as described previously (28). Table 2 lists the primer sequences used in mutant construction. All mutations were confirmed by PCR and by sequencing of the chromosomal copy of the deletion allele (data not shown).

TABLE 2.

SOE PCR primers for mutant construction

| Primer | Sequence (5′ to 3′) |

|---|---|

| SW01 soeA | TGGAAGCTTAATGCTTGCAACCGTTTTCTTTAT |

| SW02 soeB | TTGACCACCACTTTTAATGACAGA |

| SW03 soeC | TCTGTCATTAAAAGTGGTGGTCAAACAACTATCTTCCCAACTGGT |

| SW04 soeD | TGGTCTAGACATAAAAACAGCTTGAGCAAGTTACT |

| SW05 lmo0027 XF | TGGTTAGTTGAGCAAGGCGTTA |

| SW06 lmo0027 XR | AGTGCAATTCTGTTCTCATCTTCTTT |

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The effects of deletion of alternative σ factors on the growth of L. monocytogenes are dependent on the growth temperature and carbon source.

One-way ANOVA was used for initial assessment of the effect of the factor “strain” on each OD-derived growth parameter in each of the four carbon sources at 25°C or 37°C (Table 3; detailed data are provided in Tables S1 and S2, and in Fig. S1 and S2, in the supplemental material). Overall, this factor affected more growth parameters when L. monocytogenes was grown at 37°C than when it was grown at 25°C; only 5 of the 12 growth parameters were significantly affected by strain at 25°C, while 9 of the 12 growth parameters were significantly affected by strain at 37°C (Table 3). At 25°C, this factor contributed significantly to the observed differences in the maximum growth rate (μmax) and lag phase duration (λ) (P < 0.05), but not in the maximum optical density (ODmax), in DM with glucose and mannose, while in DM with cellobiose, only μmax was significantly affected by strain (Table 3). At 37°C, this factor contributed significantly to the observed differences in μmax, λ, and ODmax in all three PTS-dependent carbon sources (glucose, cellobiose, and mannose) (P < 0.05). Interestingly, no significant effect of strain on growth parameters was observed when L. monocytogenes was grown in glycerol, a non-PTS-dependent carbon source, at either 25°C or 37°C (P > 0.05) (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Results of one-way ANOVA on the effects of strain on optical density-based growth parameters

| Temp (°C) | Carbon source | PTS dependenta | Prob > Fb for: |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| μmax | λ | ODmax | |||

| 25 | Glucose | Y | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.134 |

| Mannose | Y | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.170 | |

| Cellobiose | Y | <0.001 | 0.390 | 0.199 | |

| Glycerol | N | 0.302 | 0.560 | 0.806 | |

| 37 | Glucose | Y | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Mannose | Y | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.017 | |

| Cellobiose | Y | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |

| Glycerol | N | 0.780 | 0.082 | 0.280 | |

Y, yes; N, no.

Prob > F, probability of obtaining an F value greater than the one calculated if, in reality, there is no difference in the population group means. Observed significance probabilities of <0.05 are considered as indicating that there are differences in the group means.

These results suggested that the effects of deletions of genes encoding alternative σ factors on the growth of L. monocytogenes in DM with different sugars are more pronounced at 37°C than at 25°C. This may be explained by the temperature-dependent expression of alternative σ factors and/or the alternative σ factor regulon, which has been reported previously (29–32). For example, sigL transcript levels have been shown in one study to be higher at 10°C than at 37°C in BHIB (29). Chan et al., on the other hand, reported that sigL transcript levels were lower in stationary-phase cells at 4°C than at 37°C in BHIB (30). Moreover, previous studies have shown that the transcript levels of the σB regulon are temperature dependent (31, 32); Toledo-Arana et al. specifically found that σB-mediated transcription of virulence genes, including prfA, inlA, inlB, and ctsR, was upregulated in stationary phase relative to exponential phase at 37°C but not at 30°C (31). McGann et al. found that the transcript levels of four σB-dependent internalin genes (inlC2, inlD, lmo0331, and lmo0610) were highest at 16°C and generally lowest at 37°C (32). While these findings do not provide direct evidence that alternative σ factor expression and activity are higher at 37°C than at 25°C, they do demonstrate the effect of temperature on alternative σ factor expression and activity, consistent with our findings suggesting an influence of temperature on the growth parameters observed for different alternative σ factor-null mutants in different carbon sources.

The growth of L. monocytogenes is dependent on σB, σH, and/or σL in PTS-dependent carbon sources at 37°C according to an OD-based growth study.

Since ANOVA results showed a significant effect of strain on the three growth parameters at 37°C, we used linear regression to specifically assess the effects of deletions of the genes encoding the four alternative σ factors on growth parameters in different carbon sources at 37°C. The best model for each combination of carbon source and growth parameter was selected by the Akaike information criterion (AIC) using stepwise algorithms (Fig. 1, 2, and 3 present results for λ, μmax, and ODmax, respectively; results are discussed by carbon source below). Predictor variables and their respective estimates are presented in Tables S3 to S14 in the supplemental material.

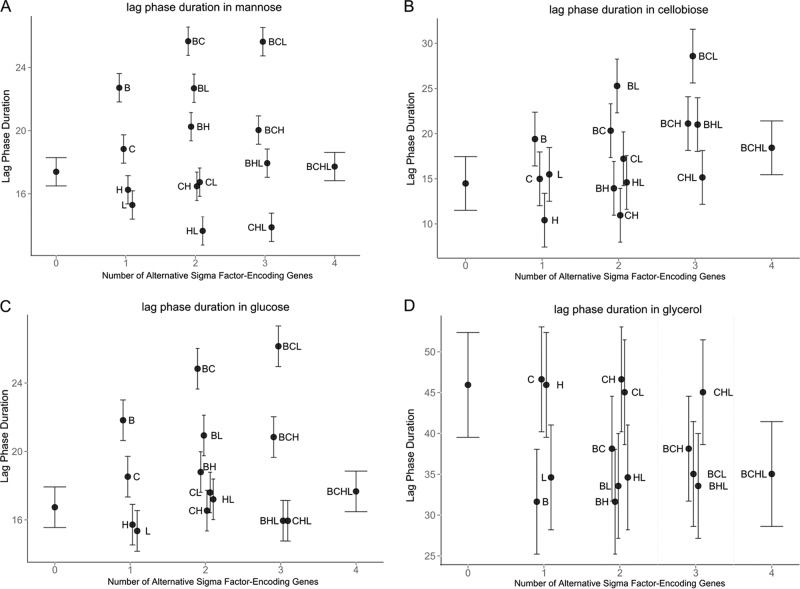

FIG 1.

Estimates for OD-based lag phase duration (λ) in DM with mannose (A), cellobiose (B), glucose (C), or glycerol (D) for 10403S and 15 isogenic mutants at 37°C. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. The lag phase duration (in hours) is shown along the y axis. The number of alternative σ factor-encoding genes present, ranging from zero (ΔsigB ΔsigC ΔsigH ΔsigL quadruple mutant) to 4 (parent strain 10403S), is shown along the x axis. B, σB; C, σC; H, σH; L, σL.

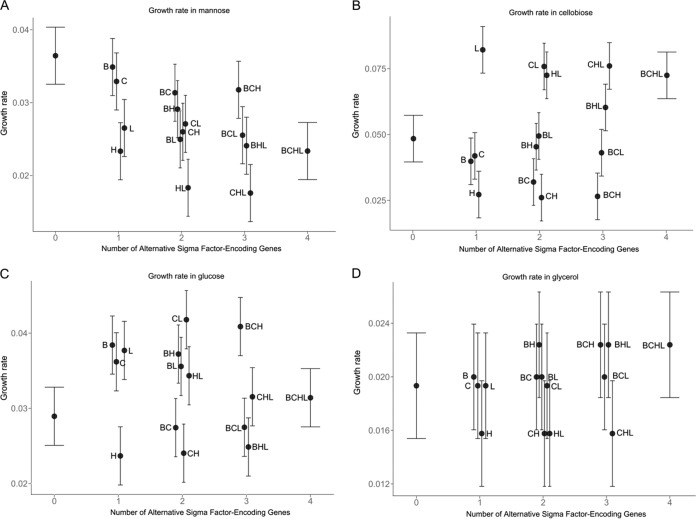

FIG 2.

Estimates for OD-based maximum growth rate (μmax) in DM with mannose (A), cellobiose (B), glucose (C), or glycerol (D) for 10403S and 15 isogenic mutants at 37°C. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. The value of μmax (OD increase per hour). The number of alternative σ factor-encoding genes present, ranging from zero (ΔsigB ΔsigC ΔsigH ΔsigL quadruple mutant) to 4 (parent strain 10403S), is shown along the x axis.

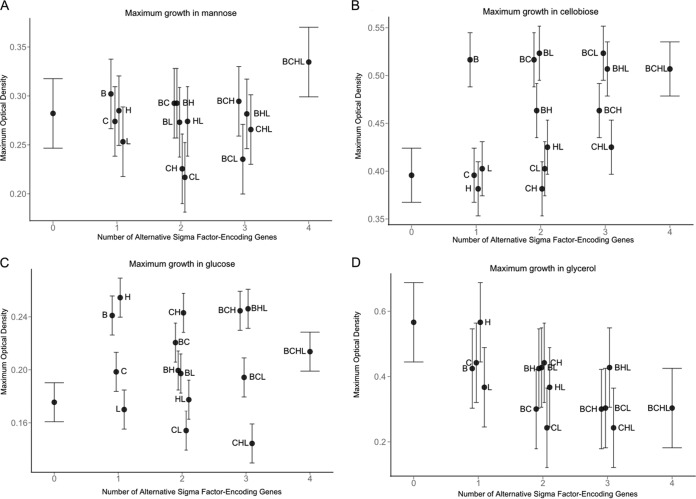

FIG 3.

Estimates for maximum OD (ODmax) in DM with mannose (A), cellobiose (B), glucose (C), or glycerol (D) for 10403S and 15 isogenic mutants at 37°C. Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals. The ODmax value is shown along the y axis. The number of alternative σ factor-encoding genes present, ranging from zero (ΔsigB ΔsigC ΔsigH ΔsigL quadruple mutant) to 4 (parent strain 10403S), is shown along the x axis.

In DM with mannose, the presence of sigB had a significant positive effect on λ (i.e., longer λ in the presence of sigB) while the presence of sigL had a significant negative effect on λ (Fig. 1A; see also Table S3 in the supplemental material). Under the same conditions, the interaction of sigB and sigL resulted in a significant positive effect on λ (Fig. 1A; see also Table S3), suggesting a regulatory interaction between the two alternative σ factors encoded by these genes. The presence of sigC also showed a significant positive effect on λ, and the interaction of sigB and sigC resulted in a significant further increase in this parameter (Fig. 1A; see also Table S3). μmax was negatively affected by the presence of sigH and sigL, but these effects were not statistically significant (P = 0.17), while the interaction between sigH and sigB resulted in a significant increase in this parameter in DM with mannose (Fig. 2A; see also Table S4 in the supplemental material). ODmax was not significantly affected by any alternative σ factor-encoding gene alone or by any interaction among alternative σ factor-encoding genes in DM with mannose (see Table S5 in the supplemental material).

In DM with cellobiose, the presence of sigB significantly increased λ (Fig. 1B; see also Table S6 in the supplemental material). The presence of sigL alone led to a significant increase in μmax in cellobiose (Fig. 2B; see also Table S7 in the supplemental material). The presence of sigH significantly reduced μmax, but the interaction between sigB and sigH led to an increase in this parameter, in DM with cellobiose (see Table S7). Conversely, the interaction of sigB and sigL resulted in a significant decrease in μmax (see Table S7), suggesting differential regulatory interactions between σB and σH, as well as between σB and σL, in DM with cellobiose. ODmax was significantly affected only by the presence of sigB, which led to an increase in this parameter, in DM with cellobiose (Fig. 3B; see also Table S8 in the supplemental material).

Growth in DM with glucose was the most affected by the presence of alternative σ factor-encoding genes. λ was significantly increased by (i) the presence of sigB, (ii) the presence of sigC, and (iii) the interaction between sigH and sigL (Fig. 1C; see also Table S9 in the supplemental material). Conversely, λ was significantly reduced by the interactions between (i) sigB and sigH, (ii) sigB, sigH, and sigL, and (iii) sigC, sigH, and sigL (see Table S9), suggesting a complex network of regulatory interactions among σ factors in DM with glucose. In DM with glucose, μmax was also significantly affected by several σ factor-encoding genes and their interactions; the presence of sigB, sigC, and sigL and the interaction between sigB, sigC, and sigH positively affected μmax (Fig. 2C; see also Table S10 in the supplemental material). The presence of sigH and the interactions between (i) sigB and sigC, (ii) sigB and sigL, (iii) sigC and sigH, and (iv) sigB, sigH, and sigL had negative effects on μmax (Fig. 2C; see also Table S10). ODmax was also highly affected by the presence of alternative σ factor-encoding genes. Interestingly, sigB, sigC, and sigH all had positive effects on ODmax, while the presence of sigL had a negative though nonsignificant effect on this parameter (Fig. 3C; see also Table S11 in the supplemental material). However, all possible combinations of interactions between two σ factor-encoding genes resulted in significantly negative effects on ODmax (see Table S11). Yet interactions among three of the four alternative σ factor-encoding genes, excluding the interaction among sigC, sigH, and sigL, resulted in significantly positive effects on ODmax, and the interaction among all four alternative σ factor-encoding genes resulted in a significantly negative effect on ODmax (see Table S11). These data suggested that in DM with glucose, alternative σ factors form a regulatory network that can drastically affect ODmax during the growth of L. monocytogenes.

The initial ANOVA did not identify a significant effect of strain on growth parameters in DM with glycerol, the only non-PTS-dependent carbon source analyzed. However, linear regression indicates that the presence of sigB or sigL significantly reduced λ, while the interaction between these two σ factor-encoding genes significantly increased λ (Fig. 1D; see also Table S12 in the supplemental material). μmax was not affected by the alternative σ factor-encoding genes (Fig. 2D; see also Table S13 in the supplemental material), while ODmax was negatively affected by the presence of sigC and sigL (Fig. 3D; see also Table S14 in the supplemental material). These results suggested that the effects of the presence or absence of alternative σ factors on growth in DM with glycerol may not necessarily be identified in strain level analysis but can be identified with linear regression, since only significant variables and their interactions are retained in the final model (e.g., only 4 of the 15 predictor variables and their interactions are included in the final model for ODmax in DM with glycerol at 37°C).

Overall, our data showed that in DM with PTS-dependent carbon sources, the presence of sigB significantly increases λ, while in DM with a non-PTS-dependent carbon source (i.e., glycerol), the presence of sigB significantly reduces λ. Moreover, with the exception of mannose, ODmax in a PTS-dependent carbon source was positively affected by the presence of sigB. The presence of sigH significantly reduced μmax in DM with any of the three PTS-dependent carbon sources. The presence of sigL, on the other hand, showed a PTS-dependent carbon-specific effect on μmax; while μmax was positively affected by sigL in DM with glucose or cellobiose, this parameter was negatively affected by sigL in DM with mannose. Interactions between alternative σ factor-encoding genes were also dependent on carbon sources. These results collectively suggested a complex regulatory network among σB, σH, and σL for the growth of L. monocytogenes in PTS-dependent carbon sources. This is not surprising, because there are considerable regulon overlaps among the alternative σ factors (14). For example, the PTSMan-2 encoded by lmo0096 to lmo0098 is the major transporter for glucose, followed by the PTSMan-3 encoded by the mpoABCD (lmo0781-to-lmo0784) operon (11, 18). It has been reported that lmo0096 to lmo0098 are positively regulated by σL (19, 33), while mpoABCD showed evidence of positive regulation by σB (13, 14). σB also has been reported to be involved in the regulation of other pts genes, including lmo0021, lmo0027, lmo0398 to lmo0400, lmo2733, lmo0631, and lmo2665 (13, 14).

The growth of L. monocytogenes is positively affected by the presence of σH and negatively affected by the presence of σL in PTS-dependent carbon sources, but not in a non-PTS-dependent carbon source, at 37°C.

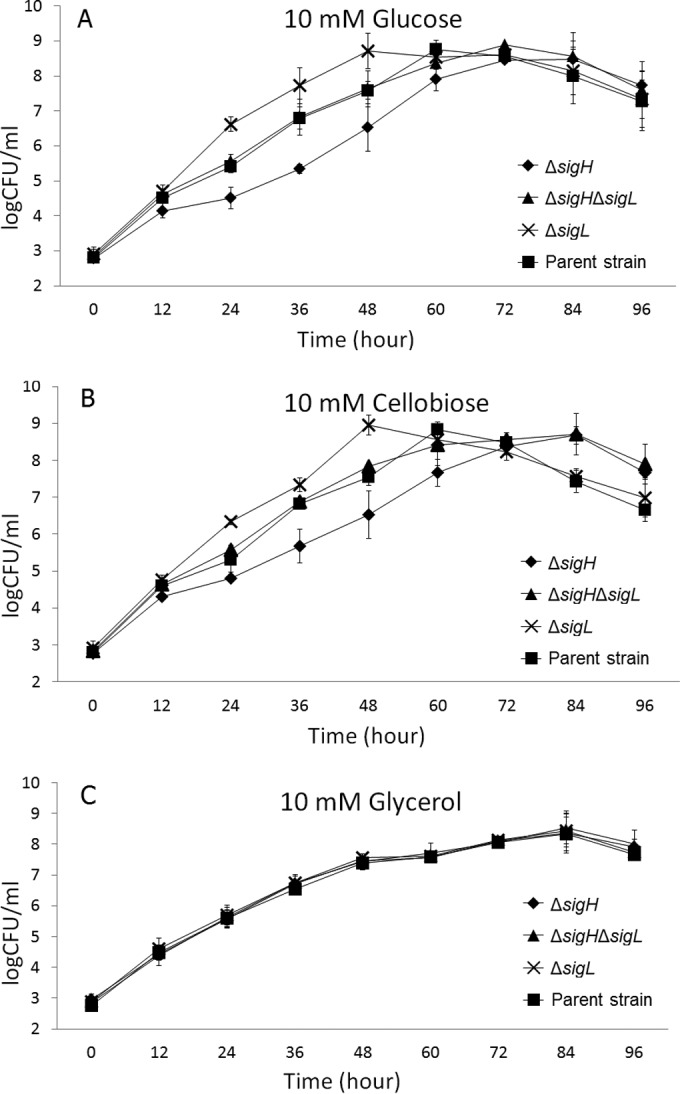

Unlike that of σB, which is well known to play a role in the stress response and virulence of L. monocytogenes, the functional roles of σL and σH have not been clearly defined to date (12). We recognize that OD cannot be used as the sole indicator for the evaluation of growth rates for L. monocytogenes (34). Therefore, in order to confirm the roles of σL and σH in the growth of L. monocytogenes, we used spread plating to compare the growth of the ΔsigH, ΔsigL, and ΔsigH ΔsigL mutants to that of the parent strain 10403S in PTS-dependent carbon sources (glucose and cellobiose) and a non-PTS-dependent carbon source (glycerol) at 37°C (Table 4; Fig. 4). In DM with glucose or cellobiose, the μmax of the ΔsigH strain decreased significantly (P < 0.01) from that of the parent strain, while the growth rate of the ΔsigL strain increased significantly (P < 0.01). In contrast, the μmax of the ΔsigH ΔsigL mutant was similar to that of the parent strain (P > 0.05) (Table 4; Fig. 4A and B). While the plate-counting results were generally consistent with the OD-based growth results, OD- and plate-counting-based parameters yielded different conclusions about μmax for the ΔsigL strain grown in DM with cellobiose. Specifically, the OD-based data indicated a significantly higher μmax for the ΔsigL strain than for the parent strain, while the plate count-based data indicated a significantly lower μmax than for the parent strain (P < 0.05). Since OD-based results are highly dependent on bacterial culture conditions (e.g., cell geometry, presence and concentrations of secreted compounds) (35), these data may suggest that the ΔsigL strain shows distinct cell geometry or physiology when exposed to cellobiose. This is consistent with a previous study that reported that the surfaces of certain rumen bacterial strains became smoother and contained fewer protuberant structures when grown in cellobiose (36). Further morphological studies on L. monocytogenes grown in DM with cellobiose will be needed to elucidate this phenomenon. In DM with glycerol, the plate-counting-based μmax values of the ΔsigH, ΔsigL, and ΔsigH ΔsigL mutants were not significantly different from that of the parent strain (P > 0.05) (Table 4; Fig. 4C). Also, deletion of sigH and/or sigL did not affect Nmax in any carbon source at 37°C (Table 4; Fig. 4).

TABLE 4.

Colony enumeration-derived growth parameters of L. monocytogenes 10403S and mutants at 37°Ca

| Carbon source | PTS dependentb | Strain or genotype | μmax [log(CFU/ml)/h] | Nmax [log(CFU/ml)] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose | Y | 10403S | 0.23 ± 0.01 C | 8.36 ± 0.34 A |

| ΔsigH | 0.18 ± 0.02 DEF | 8.27 ± 0.17 A | ||

| ΔsigL | 0.32 ± 0.03 A | 8.63 ± 0.14 A | ||

| ΔsigH ΔsigL | 0.22 ± 0.02 CDE | 8.72 ± 0.08 A | ||

| Δlmo0027 | 0.24 ± 0.01 BC | 8.62 ± 0.07 A | ||

| ΔsigH Δlmo0027 | 0.17 ± 0.01 DEF | 8.88 ± 0.04 A | ||

| ΔsigL Δlmo0027 | 0.15 ± 0.01 F | 8.96 ± 0.06 A | ||

| ΔsigH ΔsigL Δlmo0027 | 0.15 ± 0.01 F | 8.83 ± 0.15 A | ||

| Cellobiose | Y | 10403S | 0.22 ± 0.01 CD | 8.43 ± 0.41 A |

| ΔsigH | 0.17 ± 0.01 EF | 8.41 ± 0.21 A | ||

| ΔsigL | 0.28 ± 0.01 AB | 8.71 ± 0.11 A | ||

| ΔsigH ΔsigL | 0.22 ± 0.03 CD | 8.63 ± 0.26 A | ||

| Glycerol | N | 10403S | 0.20 ± 0.01 CD | 7.99 ± 0.20 A |

| ΔsigH | 0.22 ± 0.02 CDE | 8.09 ± 0.37 A | ||

| ΔsigL | 0.21 ± 0.02 CDE | 8.09 ± 0.20 A | ||

| ΔsigH ΔsigL | 0.21 ± 0.02 CDE | 8.21 ± 0.35 A | ||

| Δlmo0027 | 0.20 ± 0.01 CDE | 8.07 ± 0.23 A | ||

| ΔsigH Δlmo0027 | 0.19 ± 0.01 CDEF | 8.13 ± 0.22 A | ||

| ΔsigL Δlmo0027 | 0.18 ± 0.01 DEF | 8.25 ± 0.23 A | ||

| ΔsigH ΔsigL Δlmo0027 | 0.21 ± 0.01 CDE | 8.16 ± 0.20 A |

Results are means ± standard deviations for each bacterial strain tested in triplicate. Means followed by the same letter within a given column are not statistically different from each other (overall α, 0.05 by Tukey's honestly significant difference test).

Y, yes; N, no.

FIG 4.

Growth of the parent strain 10403S and the ΔsigH, ΔsigL, and ΔsigH ΔsigL mutants at 37°C in DM with 10 mM glucose (A), DM with 10 mM cellobiose (B), or DM with 10 mM glycerol (C).

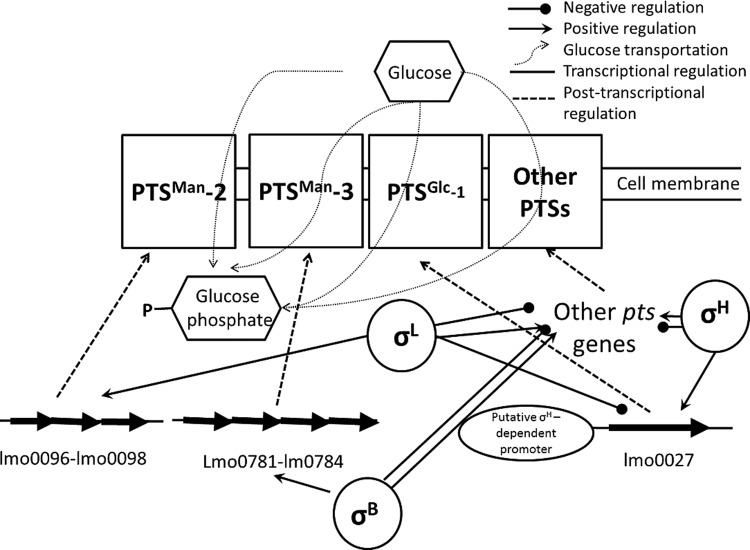

These findings indicated that σH and σL play positive and negative roles, respectively, in the utilization of PTS-dependent carbon sources for the growth of L. monocytogenes. However, previous studies have suggested that σL plays multiple roles in the regulation of PTSs. Among the genes encoding three major PTSs for glucose transport (i.e., PTSMan-2, PTSMan-3, and PTSGlc-1), lmo0096 to lmo0098, which encode PTSMan-2, have been reported to be positively regulated by σL (19), and lmo0781 to lmo0784, which encode PTSMan-3, have been reported to be constitutively transcribed with additional positive regulation by σB (11). On the other hand, lmo0027, which encodes PTSGlc-1, has not only been reported to be negatively regulated by σL (14, 19) but also is preceded by two putative σA-dependent and one putative σH-dependent promoter (20). Rea et al. also found that deletion of sigH resulted in reduced growth in minimal medium but not in BHIB (21), suggesting a role for σH in the acquisition or utilization of nutrients in minimal medium. However, the role of σH in PTS-dependent carbon source acquisition or utilization was not elucidated in previous studies.

No significant regulatory effect of σH or σL on the growth in DM with glycerol was observed at 37°C, even though the transcription of genes involved in glycerol catabolism has been shown to be σB dependent in L. monocytogenes (37). Joseph et al. specifically reported that genes known to be involved in glycerol uptake and metabolism (glpFK and glpD) showed significantly higher transcript levels with σB in the presence of glycerol than in the presence of glucose or cellobiose (2). Chaturongakul et al. reported that the transcription of glpFK and glpD was not dependent on σH or σL at 37°C (14). Arous et al. found that glpD and glpF were significantly upregulated with the loss of σL in BHIB at 42°C (19), suggesting negative regulation of these genes by σL at 42°C but not at 37°C. Collectively, these findings suggest a temperature-dependent regulation by σL of L. monocytogenes growth in glycerol.

The growth of L. monocytogenes in glucose is dependent on the regulation of lmo0027 by σL.

Since lmo0027 encodes an important glucose transporter (i.e., PTSGlc-1), and prior evidence for σH- and σL-dependent transcription has been shown, qPCR was used to quantify the change in lmo0027 transcript levels in the absence of sigH and sigL. The transcript levels of lmo0027 were 14.3- ± 3.1-fold (P < 0.01) and 10.1- ± 5.5-fold (P < 0.01) higher in the ΔsigL and ΔsigH ΔsigL strains, respectively, than in the parent strain. In the ΔsigH mutant, the lmo0027 transcript level was 2.2- ± 1.5-fold lower (P < 0.05) than that in the parent strain. These results are consistent with previous findings (19, 20), suggesting a weak positive regulatory effect of σH, and a strong negative regulatory effect of σL, on lmo0027 (Fig. 5). While σL has also been found to positively regulate other pts genes (14, 19), we hypothesized that the negative regulation of lmo0027 by σL plays a role in the reduced μmax in glucose associated with the sigL deletion.

FIG 5.

Proposed mode of regulation of PTS-dependent L. monocytogenes growth in glucose by σB, σH, and σL. Solid lines indicate transcriptional regulation (i.e., regulation at the DNA level); dotted lines indicate posttranscriptional regulation (i.e., regulation at the RNA level).

To further test the effect of lmo0027 on the growth of L. monocytogenes in DM with glucose and glycerol at 37°C, Δlmo0027, ΔsigH Δlmo0027, ΔsigL Δlmo0027, and ΔsigH ΔsigL Δlmo0027 deletion mutants of the parent strain 10403S were generated and evaluated. In agreement with the findings by Stoll and Goebel (11), the μmax of the Δlmo0027 mutant was similar to that of the parent strain in glucose (P > 0.05). However, the ΔsigL Δlmo0027 and ΔsigH ΔsigL Δlmo0027 mutants showed significantly lower μmax values at 37°C (P < 0.05) than did the parent strain, although the deletion of sigL alone resulted in significantly increased μmax at 37°C (Table 4). A previous study suggested that the loss of lmo0027 alone did not result in a reduced growth rate but that the loss of lmo0027 along with deletion of the PTSMan-2 operon and the PTSMan-3 operon led to a drastically reduced growth rate in DM with glucose (11). Taken together, these observations suggested that the negative regulation of lmo0027 by σL indeed plays a role in the growth of L. monocytogenes in glucose, even though the absence of lmo0027 alone did not impact the growth of L. monocytogenes in DM with glucose (Table 4; Fig. 5), likely because lmo0027 transcription was repressed by σL under these conditions in the parent strain.

The ΔsigH Δlmo0027 strain demonstrated a μmax similar to that of the ΔsigH strain, which was significantly lower than that of the parent strain (P < 0.05) (Table 4). This suggests that σH does not regulate lmo0027 to an extent that affects the growth of L. monocytogenes in DM with glucose. The reduced μmax of the ΔsigH mutant relative to that of the parent strain in DM with glucose is possibly associated with the positive regulation by σH of other pts genes, such as lmo0738, encoding PTSGlc-2, and lmo2355, encoding PTSFru-6 (14). The expression of lmo0738 has been reported previously to be upregulated in an hprK mutant, which was defective in carbon catabolite repression (CCR) control (10). The expression of lmo2355 was downregulated in DM with glycerol relative to DM with glucose (2). Yet the biological significance of these genes in the growth of L. monocytogenes using glucose requires further elucidation.

Conclusions.

Our present study suggests that the regulation of the growth of L. monocytogenes by alternative σ factors is both temperature and carbon source dependent. Besides σB, σL and σH coregulate PTS-dependent carbon source uptake for L. monocytogenes through complex, temperature-dependent regulatory networks that allow L. monocytogenes to fine-tune its response to changing growth conditions. σH positively regulates the growth of L. monocytogenes, and σL negatively regulates the growth of L. monocytogenes, in PTS-dependent carbon sources at 37°C. The negative regulatory effect of σL on the growth of L. monocytogenes is associated with the negative regulation of the PTSGlc-1-encoding gene, lmo0027. While lmo0027 transcription is positively regulated by σH, this regulatory effect does not seem to affect the growth of L. monocytogenes in DM with glucose at 37°C, possibly due to transcription from two identified putative σA-dependent promoters, in addition to a putative σH-dependent promoter, upstream of lmo0027. Due to the complexities of transcriptional regulation and the considerable gaps in knowledge about the function of pts genes in L. monocytogenes, further work on elucidating the regulatory effects of alternative σ factors on these pts genes will be necessary for better understanding of the carbon metabolism regulation of this important bacterial pathogen.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was funded by NIH-NIAID R01A1052151 (to K.J.B.) and by a University of British Columbia start-up award (to S.W.).

The alternative σ factor mutants used in this study were constructed by Soraya Chaturongakul and Barbara Bowen. We thank Barbara Bowen for assistance in constructing the lmo0027 deletion mutants and Matthew Stasiewicz for kindly providing technical support on the application of grofit in R.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 3 October 2014

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AEM.02530-14.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gray MJ, Freitag NE, Boor KJ. 2006. How the bacterial pathogen Listeria monocytogenes mediates the switch from environmental Dr. Jekyll to pathogenic Mr. Hyde. Infect. Immun. 74:2505–2512. 10.1128/IAI.74.5.2505-2512.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Joseph B, Mertins S, Stoll R, Schar J, Umesha KR, Luo Q, Muller-Altrock S, Goebel W. 2008. Glycerol metabolism and PrfA activity in Listeria monocytogenes. J. Bacteriol. 190:5412–5430. 10.1128/JB.00259-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johansson J, Mandin P, Renzoni A, Chiaruttini C, Springer M, Cossart P. 2002. An RNA thermosensor controls expression of virulence genes in Listeria monocytogenes. Cell 110:551–561. 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00905-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agaisse H, Burrack LS, Philips JA, Rubin EJ, Perrimon N, Higgins DE. 2005. Genome-wide RNAi screen for host factors required for intracellular bacterial infection. Science 309:1248–1251. 10.1126/science.1116008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Renzoni A, Klarsfeld A, Dramsi S, Cossart P. 1997. Evidence that PrfA, the pleiotropic activator of virulence genes in Listeria monocytogenes, can be present but inactive. Infect. Immun. 65:1515–1518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Freitag NE, Port GC, Miner MD. 2009. Listeria monocytogenes—from saprophyte to intracellular pathogen. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 7:623–628. 10.1038/nrmicro2171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goerke B, Stulke J. 2008. Carbon catabolite repression in bacteria: many ways to make the most out of nutrients. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 6:613–624. 10.1038/nrmicro1932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stoll R, Mertins S, Joseph B, Muller-Altrock S, Goebel W. 2008. Modulation of PrfA activity in Listeria monocytogenes upon growth in different culture media. Microbiology 154:3856–3876. 10.1099/mic.0.2008/018283-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Joseph B, Przybilla K, Stuhler C, Schauer K, Slaghuis J, Fuchs TM, Goebel W. 2006. Identification of Listeria monocytogenes genes contributing to intracellular replication by expression profiling and mutant screening. J. Bacteriol. 188:556–568. 10.1128/JB.188.2.556-568.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mertins S, Joseph B, Goetz M, Ecke R, Seidel G, Sprehe M, Hillen W, Goebel W, Muller-Altrock S. 2007. Interference of components of the phosphoenolpyruvate phosphotransferase system with the central virulence gene regulator PrfA of Listeria monocytogenes. J. Bacteriol. 189:473–490. 10.1128/JB.00972-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stoll R, Goebel W. 2010. The major PEP-phosphotransferase systems (PTSs) for glucose, mannose and cellobiose of Listeria monocytogenes, and their significance for extra- and intracellular growth. Microbiology 156:1069–1083. 10.1099/mic.0.034934-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chaturongakul S, Raengpradub S, Wiedmann M, Boor KJ. 2008. Modulation of stress and virulence in Listeria monocytogenes. Trends Microbiol. 16:388–396. 10.1016/j.tim.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oliver HF, Orsi RH, Wiedmann M, Boor KJ. 2010. Listeria monocytogenes σB has a small core regulon and a conserved role in virulence but makes differential contributions to stress tolerance across a diverse collection of strains. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76:4216–4232. 10.1128/AEM.00031-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chaturongakul S, Raengpradub S, Palmer ME, Bergholz TM, Orsi RH, Hu YW, Ollinger J, Wiedmann M, Boor KJ. 2011. Transcriptomic and phenotypic analyses identify coregulated, overlapping regulons among PrfA, CtsR, HrcA, and the alternative sigma factors σB, σC, σH, and σL in Listeria monocytogenes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77:187–200. 10.1128/AEM.00952-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Becker LA, Evans SN, Hutkins RW, Benson AK. 2000. Role of σB in adaptation of Listeria monocytogenes to growth at low temperature. J. Bacteriol. 182:7083–7087. 10.1128/JB.182.24.7083-7087.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oliver HF, Orsi RH, Ponnala L, Keich U, Wang W, Sun Q, Cartinhour SW, Filiatrault MJ, Wiedmann M, Boor KJ. 2009. Deep RNA sequencing of L. monocytogenes reveals overlapping and extensive stationary phase and sigma B-dependent transcriptomes, including multiple highly transcribed noncoding RNAs. BMC Genomics 10:641. 10.1186/1471-2164-10-641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abram F, Starr E, Karatzas KAG, Matlawska-Wasowska K, Boyd A, Wiedmann M, Boor KJ, Connally D, O'Byrne CP. 2008. Identification of components of the σB regulon in Listeria monocytogenes that contribute to acid and salt tolerance. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:6848–6858. 10.1128/AEM.00442-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ake FMD, Joyet P, Deutscher J, Milohanic E. 2011. Mutational analysis of glucose transport regulation and glucose-mediated virulence gene repression in Listeria monocytogenes. Mol. Microbiol. 81:274–293. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07692.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arous S, Buchrieser C, Folio P, Glaser P, Namane A, Hebraud M, Hechard Y. 2004. Global analysis of gene expression in an rpoN mutant of Listeria monocytogenes. Microbiology 150:1581–1590. 10.1099/mic.0.26860-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mujahid S, Orsi RH, Boor KJ, Wiedmann M. 2013. Protein level identification of the Listeria monocytogenes sigma H, sigma L, and sigma C regulons. BMC Microbiol. 13:156. 10.1186/1471-2180-13-156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rea RB, Gahan CGM, Hill C. 2004. Disruption of putative regulatory loci in Listeria monocytogenes demonstrates a significant role for fur and PerR in virulence. Infect. Immun. 72:717–727. 10.1128/IAI.72.2.717-727.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang CM, Nietfeldt J, Zhang M, Benson AK. 2005. Functional consequences of genome evolution in Listeria monocytogenes: the lmo0423 and lmo0422 genes encode σC and LstR, a lineage II-specific heat shock system. J. Bacteriol. 187:7243–7253. 10.1128/JB.187.21.7243-7253.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Amezaga MR, Davidson I, McLaggan D, Verheul A, Abee T, Booth IR. 1995. The role of peptide metabolism in the growth of Listeria monocytogenes ATCC 23074 at high osmolarity. Microbiology 141(Part 1):41–49. 10.1099/00221287-141-1-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kahm M, Hasenbrink G, Lichtenberg-Fraté H, Ludwig J, Kschischo M. 2010. grofit: fitting biological growth curves with R. J. Stat. Softw. 33(7). http://www.jstatsoft.org/v33/i07. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baranyi J, Roberts TA. 1994. A dynamic approach to predicting bacterial-growth in food. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 23:277–294. 10.1016/0168-1605(94)90157-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vu-Khac H, Miller KW. 2009. Regulation of mannose phosphotransferase system permease and virulence gene expression in Listeria monocytogenes by the EIItMan transporter. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75:6671–6678. 10.1128/AEM.01104-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mellin JR, Tiensuu T, Becavin C, Gouin E, Johansson J, Cossart P. 2013. A riboswitch-regulated antisense RNA in Listeria monocytogenes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 110:13132–13137. 10.1073/pnas.1304795110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chan YC, Hu Y, Chaturongakul S, Files KD, Bowen BM, Boor KJ, Wiedmann M. 2008. Contributions of two-component regulatory systems, alternative sigma factors, and negative regulators to Listeria monocytogenes cold adaptation and cold growth. J. Food Prot. 71:420–425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu SQ, Graham JE, Bigelow L, Morse PD, Wilkinson BJ. 2002. Identification of Listeria monocytogenes genes expressed in response to growth at low temperature. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 68:1697–1705. 10.1128/AEM.68.4.1697-1705.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chan YC, Raengpradub S, Boor KJ, Wiedmann M. 2007. Microarray-based characterization of the Listeria monocytogenes cold regulon in log- and stationary-phase cells. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:6484–6498. 10.1128/AEM.00897-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Toledo-Arana A, Dussurget O, Nikitas G, Sesto N, Guet-Revillet H, Balestrino D, Loh E, Gripenland J, Tiensuu T, Vaitkevicius K, Barthelemy M, Vergassola M, Nahori MA, Soubigou G, Regnault B, Coppee JY, Lecuit M, Johansson J, Cossart P. 2009. The Listeria transcriptional landscape from saprophytism to virulence. Nature 459:950–956. 10.1038/nature08080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McGann P, Ivanek R, Wiedmann M, Boor KJ. 2007. Temperature-dependent expression of Listeria monocytogenes internalin and internalin-like genes suggests functional diversity of these proteins among the listeriae. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:2806–2814. 10.1128/AEM.02923-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dalet K, Cenatiempo Y, Cossart P, Hechard Y, European Listeria Genome Consortium 2001. A σ54-dependent PTS permease of the mannose family is responsible for sensitivity of Listeria monocytogenes to mesentericin Y105. Microbiology 147:3263–3269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Francois K, Devlieghere F, Standaert AR, Geeraerd AH, Cools I, Van Impe JF, Debevere J. 2005. Environmental factors influencing the relationship between optical density and cell count for Listeria monocytogenes. J. Appl. Microbiol. 99:1503–1515. 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2005.02727.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Biesta-Peters EG, Reij MW, Joosten H, Gorris LGM, Zwietering MH. 2010. Comparison of two optical-density-based methods and a plate count method for estimation of growth parameters of Bacillus cereus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76:1399–1405. 10.1128/AEM.02336-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miron J, Ben-Ghedalia D, Yokoyama MT, Lamed R. 1990. Some aspects of cellobiose effect on bacterial cell surface structures involved in lucerne cell walls utilization by fresh isolates of rumen bacteria. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 30:107–120. 10.1016/0377-8401(90)90055-D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Abram F, Wan-Lin S, Wiedmann M, Boor KJ, Coote P, Botting C, Karatzas KAG, O'Byrne CP. 2008. Proteomic analyses of a Listeria monocytogenes mutant lacking σB identify new components of the σB regulon and highlight a role for σB in the utilization of glycerol. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:594–604. 10.1128/AEM.01921-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bishop DK, Hinrichs DJ. 1987. Adoptive transfer of immunity to Listeria monocytogenes. The influence of in vitro stimulation on lymphocyte subset requirements. J. Immunol. 139:2005–2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wiedmann M, Arvik TJ, Hurley RJ, Boor KJ. 1998. General stress transcription factor σB and its role in acid tolerance and virulence of Listeria monocytogenes. J. Bacteriol. 180:3650–3656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.