Abstract

Trypanosoma cruzi, the agent of Chagas disease, binds to diverse extracellular matrix proteins. Such an ability prevails in the parasite forms that circulate in the bloodstream and contributes to host cell invasion. Whether this also applies to the insect-stage metacyclic trypomastigotes, the developmental forms that initiate infection in the mammalian host, is not clear. Using T. cruzi CL strain metacyclic forms, we investigated whether fibronectin bound to the parasites and affected target cell invasion. Fibronectin present in cell culture medium bound to metacyclic forms and was digested by cruzipain, the major T. cruzi cysteine proteinase. G strain, with negligible cruzipain activity, displayed a minimal fibronectin-degrading effect. Binding to fibronectin was mediated by gp82, the metacyclic stage-specific surface molecule implicated in parasite internalization. When exogenous fibronectin was present at concentrations higher than cruzipain can properly digest, or fibronectin expression was stimulated by treatment of epithelial HeLa cells with transforming growth factor beta, the parasite invasion was reduced. Treatment of HeLa cells with purified recombinant cruzipain increased parasite internalization, whereas the treatment of parasites with cysteine proteinase inhibitor had the opposite effect. Metacyclic trypomastigote entry into HeLa cells was not affected by anti-β1 integrin antibody but was inhibited by anti-fibronectin antibody. Overall, our results have indicated that the cysteine proteinase of T. cruzi metacyclic forms, through its fibronectin-degrading activity, is implicated in host cell invasion.

INTRODUCTION

Extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins, which serve as substrates for diverse adhesion molecules and are involved in many important physiological processes, also may mediate cell attachment and/or invasion of pathogenic microorganisms. Among these molecules, fibronectin (FN) has been reported to play a role in adherence to and invasion of host cells by bacteria such as Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pyogenes, and Campylobacter jejuni (1–6). The interaction of fibronectin with Trypanosoma cruzi, the protozoan parasite that causes Chagas disease, also has been described. T. cruzi infection is initiated by metacyclic trypomastigote (MT) from the insect vector. This parasite form is responsible for the initial T. cruzi-host cell interaction upon entering the mammalian host through the skin or by the oral route. Following MT internalization in a membrane-bound vacuole and escape to the cytoplasm, the parasite differentiates into amastigote form. After several rounds of replication, amastigotes transform into trypomastigotes that are released in the circulation upon host cell rupture. Experiments with tissue culture trypomastigote (TCT), which corresponds to the bloodstream trypomastigote, revealed the involvement of fibronectin in target cell adhesion/invasion. The treatment of 3T3 fibroblasts or rat peritoneal macrophages, or TCT, with human plasma FN increased parasite-cell association (7), and binding to the TCT surface of the peptide RGDS, corresponding to the FN cell attachment site, inhibited parasite internalization (8). An 85-kDa protein from TCT was identified as the ligand for FN (9). In murine macrophages or human blood monocytes, the uptake of amastigotes increased in the presence of exogenous FN or by pretreatment of either parasite or host cell with FN (10). There is no information on whether FN is required for MT internalization. As different T. cruzi developmental forms may differentially interact with ECM components, we investigated the participation of FN in MT entry into human epithelial cells, as well as the FN-binding property of gp82, the metacyclic-stage surface molecule implicated in T. cruzi infection in vitro as well as in vivo (11–13). Gp82 is an adhesion molecule that binds to host cells in a receptor-mediated manner and promotes MT internalization (11). Previous studies have shown that the ability of MT gp82 in binding ECM components, such as collagen, heparan sulfate, and laminin, is either null or very low (11, 14), in contrast to 80- to 85-kDa glycoproteins expressed in TCT that bind to these compounds (15, 16). We also examined the role played in MT internalization by cruzipain, the major T. cruzi cysteine proteinase that is a member of a large family of closely related isoforms (17, 18). Cruzipain has been implicated in host cell invasion by TCT (19) through its activity on kininogen and bradykinin release (20), which is increased up to 35-fold in the presence of heparan sulfate (21). Using metacyclic forms of a T. cruzi strain that enter target cells in a manner mediated by gp82, in this study we tested the possibility that cruzipain interacted with fibronectin and modulated the T. cruzi invasion of host cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Parasites, mammalian cells, and cell invasion assay.

T. cruzi strain CL (22) was used throughout. In some experiments, G strain (23) also was used. Parasites were maintained by cyclic passage in mice and in axenic cultures in liver infusion tryptose medium. Metacyclic forms, at the stationary growth phase in liver infusion tryptose medium (G strain) or in Grace's medium (CL strain), were purified by passage through a DEAE-cellulose column (24). HeLa cells, the human carcinoma-derived epithelial cells, were grown at 37°C in Dulbecco's minimum essential medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), streptomycin (100 μg/ml), and penicillin (100 U/ml) in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere. Cell invasion assays were carried out as previously described (25) by incubating parasites with HeLa cells for 1 h at a multiplicity of infection of 10:1 (CL strain) or 20:1 (G strain), either in serum-containing DMEM, bovine serum albumin (BSA)-containing DMEM, or PBS++ (PBS containing, per liter, 140 mg CaCl2, 400 mg KCl, 100 mg MgCl2 · 6H2O, 100 mg MgSO4 · 7H2O, 350 mg NaHCO3). For intracellular parasite counting, HeLa cells were washed in PBS, fixed in Bouin solution, stained with Giemsa, and sequentially dehydrated in acetone, a graded series of acetone-xylol and xylol. A total of 250 stained cells were counted.

Indirect immunofluorescence assay for visualization of fibronectin in mammalian cells and in parasites.

HeLa cells and A549 cells, grown in 13-mm glass slides, were incubated for 1 h at 4°C with polyclonal anti-human FN antibody produced in rabbit and diluted 1:100 in PGN (0.15% gelatin in PBS containing 0.1% sodium azide). Following washings in PBS, 30 min of fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS, and treatment with 50 mM NH4CL for 30 min, the cells were incubated for 1 h with Alexa Fluor 568-conjugated anti-rabbit-IgG (Invitrogen) in PGN. After 1 h of incubation with phalloidin-fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC; Invitrogen) diluted 1:2,000 in PGN containing 0.1% saponin and 10 μg/ml DAPI (4′,6′1-diamino-2-phenylindole dihydrochloride) for visualization of actin cytoskeleton and nucleus, respectively, the cells were examined in a confocal laser scanning microscope (Leica TCS SP8; Germany) equipped with a Plan-Apochromat 63× objective (numerical aperture, 1.4) under oil immersion. The z-series images were processed and analyzed using Leica LAS AF software (2012 version; Leica, Germany). For the visualization of FN on the parasite surface, purified metacyclic forms were incubated for 1 h at 37°C in DMEM containing 10% FBS (DMEM-FBS). After washings in PBS, anti-FN antibodies (Sigma-Aldrich), diluted 1:100 in PGN, were added, and the incubation proceeded for 1 h at room temperature. Followings washings in PBS, 30 min of fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS, and 30 min of treatment with 50 mM NH4CL, the parasites were washed in PBS, placed onto glass slides, and dried. Upon 1 h of incubation with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-IgG (Invitrogen) diluted in PGN containing 0.1% saponin and 10 μg/ml DAPI for visualization of kinetoplast and nucleus, images were acquired with a Nikon E600 fluorescence microscope coupled to a Nikon DXM 1200F digital camera using ACT-1 software. For the detection of the T. cruzi surface molecule gp82, metacyclic forms were incubated for 1 h on ice with monoclonal antibody directed to gp82. After washings in PBS and fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde, the parasites were processed as described above for visualization with the fluorescence microscope.

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis of T. cruzi MT treated with E-64.

Live metacyclic trypomastigotes (1 × 107) were left untreated or were incubated with 100 μM cysteine proteinase inhibitor E-64 in PBS for 30 min at 37°C. After washings in PBS, E-64-treated parasites were maintained for 1 h at 37°C in DMEM-FBS in the presence of E-64, and the controls were maintained in the absence of inhibitor. Thereafter, the parasites were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min. Following washings in PBS, the parasites were sequentially incubated for 1 h at room temperature with anti-FN antibodies and Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-IgG, and the number of fluorescence parasites was estimated with a BD Accuri C6 flow cytometer.

Production and purification of recombinant cruzipain and gp82.

The recombinant protein based on T. cruzi major cysteine protease (cruzipain), expressed in Escherichia coli DH5α without the COOH terminal, was purified, and its activity was tested by fluorometric assay as described previously (17). The production and purification of the recombinant gp82 protein, containing the full-length T. cruzi gp82 sequence (GenBank accession number L14824) in frame with glutathione S-transferase (GST), were performed as detailed previously (26).

Binding of recombinant protein gp82 to FN.

Microtiter plates were coated with fibronectin (Sigma-Aldrich) at 2 μg/well. After blocking with PBS containing 2 mg/ml bovine serum albumin (PBS-BSA) for 1 h at 37°C, the plates were sequentially incubated for 1 h with the recombinant gp82 and the polyclonal monospecific antibody directed to gp82, produced by immunizing mice with the recombinant protein, all diluted in PBS-BSA. Upon reaction with peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse IgG in PBS-BSA, the final reaction was revealed by o-phenilenediamine and the absorbance at 492 nm read in a Multiscan MS enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) reader.

Treatment of FN with recombinant cruzipain or with T. cruzi metacyclic forms.

Fibronectin was treated for 1 h at 37°C with 170 nM recombinant cruzipain in 50 mM Na2PO4, 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, pH 6.5, 2.5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), and 5% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). The control FN sample was incubated under the same conditions in the absence of enzyme, and the samples were analyzed by the silver staining of SDS-PAGE gel. The effect of T. cruzi on FN was examined by incubating FN with 3 ×107 metacyclic trypomastigotes in l00 mM sodium citrate, pH 6.5. After centrifugation, the pellet was discarded and the supernatant was analyzed, along with the control FN, by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie blue staining of the gel.

Determination of T. cruzi cysteine proteinase activity.

Metacyclic forms were lysed in 0.4% Triton X-100, solubilized in a sample buffer without 2-mercaptoethanol, and then loaded onto 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel copolymerized with 0.1% gelatin as the substrate. After electrophoresis, the gel was subjected to two 30-min washings with 2.5% Triton X-100 in acetate buffer, pH 6.0, to remove SDS and incubated overnight in the same buffer without detergent. The gel was stained with Coomassie blue R250 and destained for visualization of white bands against a blue background.

Statistical analysis.

The significance level of experimental data was calculated using the Student t test, as implemented in the program GraphPad Prism.

RESULTS

FN inhibits T. cruzi MT entry into host cells.

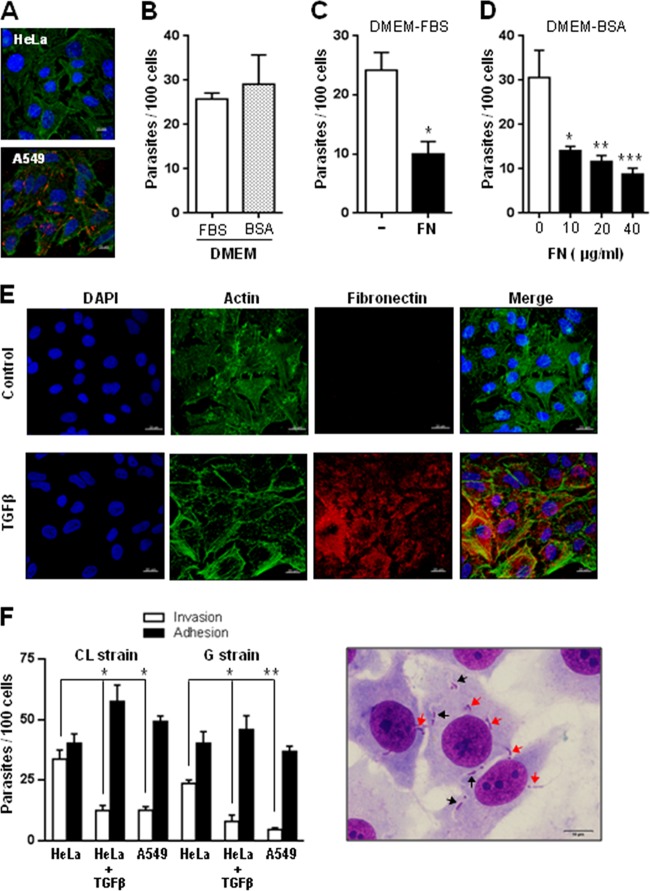

We first examined whether FN was present on the surface of HeLa cells. By indirect immunofluorescence microscopy, a positive reaction with anti-FN antibodies was observed in human alveolar epithelial A549 cells but not in HeLa cells (Fig. 1A), confirming reports that FN is undetectable on HeLa cell surfaces (27) or that it binds severalfold less to HeLa cells than to fibroblastic MRC-5 cells (28). According to another study, HeLa cells do not synthesize fibronectin and form focal contacts in FN-depleted medium (29). To determine whether FN was required for MT entry into HeLa cells, the following sets of experiments were performed. CL strain metacyclic forms were incubated with HeLa cells in DMEM containing 10% FBS (DMEM-FBS) or in serum-free DMEM supplemented with 1% BSA (DMEM-BSA). FN was estimated to be present in DMEM-FBS at approximately 3 μg/ml on the basis of a report that FN concentration in FBS is 25 to 30 μg/ml (30). After 1 h of incubation, the number of intracellular parasites was counted. MT internalization was lower in DMEM-FBS than in DMEM-BSA, but the difference was not statistically significant (Fig. 1B). This indicated that FN is not required for MT invasion. The next experiment consisted of incubating MT with HeLa cells for 1 h in DMEM-FBS that had been left unsupplemented or supplemented with 40 μg/ml bovine FN. Supplementation with FN significantly diminished parasite invasion (Fig. 1C). In these assays, human FN exhibited an inhibitory effect similar to that of bovine FN and was preferentially used in subsequent experiments. FN concentrations lower than 40 μg/ml were equally effective in inhibiting MT entry into HeLa cells in DMEM-BSA (Fig. 1D). Other extracellular matrix components, such as laminin and collagen, at 40 μg/ml, had no inhibitory effect. To further assess the effect of FN on MT invasion, assays also were performed with HeLa cells treated with transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β). Treatment of primary cultures and established cell lines from various types with TGF-β stimulates the expression of fibronectin and collagen, as well as their incorporation into the extracellular matrix (31). HeLa cells were left untreated or were treated for 24 h with 20 ng/ml TGF-β and then were processed for immunofluorescence using anti-FN antibodies. Confocal microscopy images showed that TGF-β induced FN expression in HeLa cells (Fig. 1E). Invasion assays with HeLa cells treated with TGF-β were performed with MT of CL and G strains. Human alveolar epithelial A549 cells also were tested. Parasites were incubated for 1 h with untreated or TGF-β-treated HeLa cells, or with A549 cells, in fibronectin-free PBS++ solution, and the rate of invasion as well as the levels of parasite adhesion were measured. Through Giemsa staining followed by sequential dehydration, internalized parasites were discriminated from those merely adherent to cells (Fig. 1F). HeLa cells treated with TGF-β were significantly more resistant to invasion by MT of both strains, and the ratio of adherent to internalized parasites was much higher than that in untreated controls (Fig. 1F). The susceptibility to invasion of A549 cells was comparable to that of TGF-β-treated HeLa cells (Fig. 1F). Taken together, these results indicated that FN functions as a barrier for MT-target cell interaction.

FIG 1.

Inhibitory effect of fibronectin (FN) on T. cruzi MT entry into host cells. (A) Semiconfluent monolayers of HeLa and A549 cells were processed for confocal fluorescence analysis using anti-FN antibodies and Alexa Fluor 568-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (red), phalloidin-FITC (green) for F-actin visualization, and DAPI (blue) for DNA. Bar, 10 μm. Note the lack of FN expression in HeLa cells. (B) Metacyclic forms (CL strain) were incubated for 1 h with HeLa cells in DMEM containing either 10% FBS (DMEM-FBS) or 1% BSA (DMEM-BSA), and the number of internalized parasites was counted in 250 Giemsa-stained cells. Values are the means ± standard deviations (SD) from four independent assays. (C and D) MT invasion assays were performed in DMEM-FBS in the absence or presence of 40 μg/ml bovine FN (C) or in DMEM-BSA containing human FN at the indicated concentrations (D). Values in panels C and D are the means ± SD from three independent assays. The inhibition of MT invasion by FN was significant in panels C (*, P < 0.005) and D (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***P < 0.005). (E) HeLa cells were either left untreated or treated with TGF-β for 24 h and processed as described for panel A). Note the FN expression in TGF-β-treated cells. (F) Untreated and TGF-β-treated HeLa cells, as well as A549 cells, were incubated with MT of the indicated T. cruzi strains. After 1 h, the number of internalized and adherent parasites was counted in a total of 250 cells after Giemsa staining and sequential dehydration. The values are the means ± SD from three independent assays performed in duplicate. Values are the means ± SD from three independent assays. TGF-β treatment significantly reduced MT internalization (*, P < 0.01). The difference in invasion rate between HeLa and A549 cells was significant (**, P < 0.005). Shown on the right are Giemsa-stained HeLa cells with internalized metacyclic forms surrounded by a clear space (black arrows), clearly distinguishable from adherent parasites (red arrow). Scale bar, 10 μm.

MT surface molecule gp82 binds to FN.

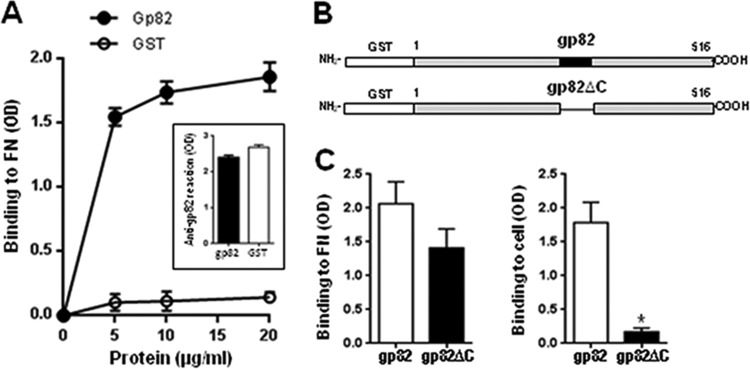

Metacyclic forms of T. cruzi CL strain used in this study engage the surface molecule gp82 to efficiently enter host cells (11). Therefore, binding of gp82 to FN before interaction with target cells could impair parasite internalization. To determine whether gp82 binds to FN, ELISA was performed by incubating FN-coated plates for 1 h with the recombinant protein containing gp82 sequence fused to GST, or with GST as a control, at various concentrations, followed by reaction with antibodies directed to the recombinant gp82. These antibodies that also recognized GST revealed that the recombinant gp82, but not GST, binds to FN in a dose-dependent and saturable manner (Fig. 2A). To examine the possibility that the FN-binding site was nested in the gp82 central domain, where the host cell adhesion sites are located (32), the GST-fused construct containing the entire gp82 sequence and its counterpart lacking the central domain, which are schematically depicted in Fig. 2B, were used for FN- and host cell-binding assays. Microtiter plates coated with FN or with HeLa cells were incubated with either recombinant protein at 10 μg/ml, and binding was revealed using polyclonal anti-gp82 antibodies that react equally with both proteins. In repeated experiments, the recombinant protein lacking the central domain exhibited negligible adhesion capacity toward HeLa cells while preserving the FN-binding property (Fig. 2C). Although the binding of the truncated construct to FN apparently was less efficient than that of the full-length gp82 construct, the difference was not statistically significant. An additional experiment confirmed that the FN-binding site of gp82 is not nested in the central domain of the molecule. Inhibition binding assays, performed by incubating FN-coated plates with the recombinant gp82 in the presence of individual 20-mer synthetic peptides with an overlap of 10 residues, spanning the gp82 central domain (32), revealed that none of the 10 peptides tested was capable of significantly inhibiting gp82 binding to FN (data not shown).

FIG 2.

Binding of T. cruzi gp82 to FN. (A) The recombinant gp82 protein, containing the full-length gp82 peptide sequence, was added to microtiter plates coated with FN at the indicated concentrations, and the binding was assayed as described in Materials and Methods. The reaction was revealed by sequential incubation with polyclonal antibodies directed to the recombinant gp82, which reacted equally with the recombinant gp82 and GST (inset), and anti-mouse IgG conjugated to peroxidase. Values are the means ± SD from triplicates of one representative assay out of three. Note the FB binding of gp82 but not of GST. Shown in the inset is the equal binding of the recombinant gp82 and GST (10 μg/ml) to anti-gp82 antibody. OD, optical density. (B) Schematic representation of recombinant proteins based on gp82 molecule. Shown are the GST-fused constructs containing the full-length gp82 sequence or lacking the central domain of the molecule, where the cell adhesion sites are located. (C) Microtiter plates coated with FN or with HeLa cells were incubated with the indicated recombinant protein, at 10 g/ml, and the reaction proceeded as described for panel A. Values are the means ± SD from three experiments performed in triplicate. The binding of gp82 protein lacking the central domain was significantly reduced (*, P < 0.001) compared to that of full-length gp82.

FN-degrading capacity of metacyclic forms is associated with cruzipain activity.

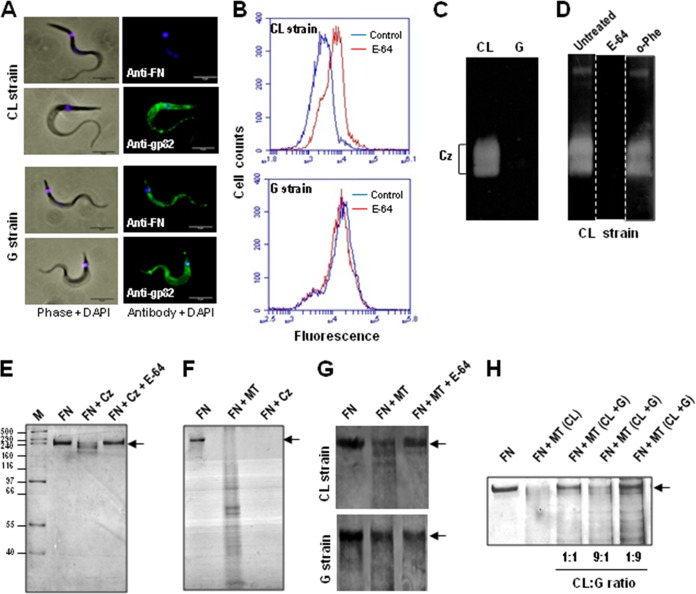

To certify that FN from cell culture medium binds to the MT surface, the parasites were incubated for 1 h in DMEM-FBS and subsequently processed for immunofluorescence using anti-FN antibodies. In this assay, we also used a T. cruzi strain (G) from the wild transmission cycle (23) that was genetically divergent from the CL strain (33). FN was undetectable in the CL strain but could be visualized on the G strain MT surface (Fig. 3A). Provided that FN binding is mediated by gp82 and the gp82 molecules expressed in CL and G strains share 97.9% sequence identity (34), what could explain the observed difference? Unequal gp82 distribution on the surface was unlikely. By immunofluorescence, using monoclonal antibody directed to gp82, both parasite strains displayed a similar profile of reactivity (Fig. 3A). We examined the possibility that CL strain MT digested FN and that cruzipain was involved in the process. CL strain metacyclic forms express cruzipain, which is inhibited by the cysteine proteinase inhibitor E-64 (35). To determine whether E-64 impaired the dissociation of FN from MT, the parasites were treated for 30 min with E-64 before incubation with DMEM-FBS. After 1 h in the culture medium, the untreated control and E-64-treated parasites were processed for FACS analysis using anti-FN antibodies. As shown in Fig. 3B, association with FN increased in E-64-treated parasites. The same procedure used to analyze G strain MT did not reveal any difference of reactivity to anti-FN antibodies between untreated and E-64-treated parasites (Fig. 3B). The possibility that cruzipain is implicated in promoting the dissociation of FN from CL strain MT was reinforced by analyzing the cysteine proteinase activity of CL and G strains. Electrophoresis of parasite extracts in gelatin-containing SDS-PAGE gel, followed by Coomassie blue staining, revealed in CL strain, but not in G strain, bands of 57 and 51 kDa corresponding to cruzipain (Fig. 3C). To confirm the identity of these bands as cruzipain, gel strips were left untreated or were treated with E-64 or with the metalloproteinase inhibitor o-phenanthroline. No proteinase activity was detected in the gel strip treated with E-64, whereas the gel strip treated with o-phenanthroline revealed bands indistinguishable from those in the untreated control (Fig. 3D). It should be mentioned that the lack of detection of G strain cruzipain activity in gelatin gel presumably is not due to deficient expression but rather to the inhibitory effect of chagasin bound to cruzipain. According to Santos et al. (36), the molar ratio of cruzipain and chagasin in G strain (5:1) differs from that of several other T. cruzi strains (∼50:1).

FIG 3.

Fibronectin-degrading activity of T. cruzi cysteine proteinase. (A) Metacyclic forms of the indicated strains were incubated for 1 h in DMEM-FBS and processed for immunofluorescence using anti-FN antibodies or the monoclonal antibody directed to gp82, followed by anti-mouse IgG conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488 (green) and DAPI (blue). Phase-contrast and immunofluorescence images of MT are shown. Bar, 5 μm. (B) Metacyclic forms were incubated for 1 h in DMEM-FBS in the absence (control) or in the presence of the cysteine proteinase inhibitor E-64. Subsequently, the parasites were processed for FACS analysis using anti-FN antibodies. (C) To detect cruzipain activity, Triton X-100 extracts, equivalent to 2 × 107 MT of the indicated T. cruzi strains, were electrophoresed in 10% SDS-PAGE gel containing gelatin and processed as described in Materials and Methods. Note the lack of activity in G strain. (D) After electrophoresis, gel strips were either left untreated or were treated with 1 μM E-64 or with 10 mM metalloproteinase inhibitor o-phenanthroline. Proteinase activity, undetectable in the gel strip treated with E-64, was preserved after treatment with o-phenanthroline. (E) Human FN (30 ng) was incubated in the absence or in the presence of 170 nM recombinant cruzipain (Cz) for 1 h at 37°C. The samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE, and the gel was silver stained. (F) Human FN (500 ng) was incubated with MT for 1 h. After centrifugation, the pellet was discarded and the supernatant was analyzed by SDS-PAGE and staining of the gel with Coomassie R250, along with the control FN and Cz-treated FN. (G) FN (1 μg) was incubated for 1 h with CL or G strain MT in the absence or in the presence of E-64 and processed as described for panel F. (H) Samples of CL strain MT alone or mixed with G strain MT at a ratio of 1:1, 1:9, or 9:1 were maintained for 30 min at 37°C in DTT-containing solution, pH 6.5. FN (1 μg) was added, and incubation proceeded for 1 h before analysis by SDS-PAGE, followed by silver staining of the gel. Note the extensive inhibition of FN degradation at a CL/G ratio of 1:9.

To ascertain that cruzipain possessed FN-degrading activity, 1 μg fibronectin was incubated in DTT-containing solution, pH 6.5, either alone or with recombinant cruzipain that was untreated or pretreated with E-64. After 1 h at 37°C, the samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE and the gel was silver stained. FN was extensively degraded by cruzipain in a manner inhibitable by E-64 (Fig. 3E). The FN-digesting activity of MT was ascertained by incubating 3 × 107 parasites (CL strain) with 500 ng FN in sodium citrate, pH 6.5. After centrifugation, the pellet was discarded and the supernatant was analyzed by SDS-PAGE and staining of the gel with Coomassie R250 along with the control FN and cruzipain-treated FN. Metacyclic forms were capable of degrading FN in the same manner as the recombinant cruzipain (Fig. 3F). To further assess the association of cruzipain with the FN-degrading activity of MT, the cruzipain-deficient G strain also was examined by incubating 3 × 107 parasites with 1 μg FN by following the procedure described above. Metacyclic forms of the CL strain, but not of the G strain, extensively degraded FN in a manner inhibitable by E-64 (Fig. 3G). FN, ranging from 2 to 8 μg, exhibited increasing resistance but still was susceptible to degradation by CL strain MT (data not shown). An additional experiment was performed to investigate whether the FN-degrading activity of CL strain could be affected by G strain. Samples of 3 × 107 CL strain MT alone or mixed with G strain MT at a ratio of 1:1, 1:9, or 9:1 were maintained for 30 min at 37°C in DTT-containing solution, pH 6.5. FN (1 μg) was added, and incubation proceeded for 1 h before analysis by SDS-PAGE followed by silver staining of the gel. Inhibition of FN degradation was minimal at a CL-to-G ratio of 9:1, considerable at 1:1, and very pronounced at 1:9 (Fig. 3H), suggesting that this inhibitory effect is due to chagasin secreted by G strain.

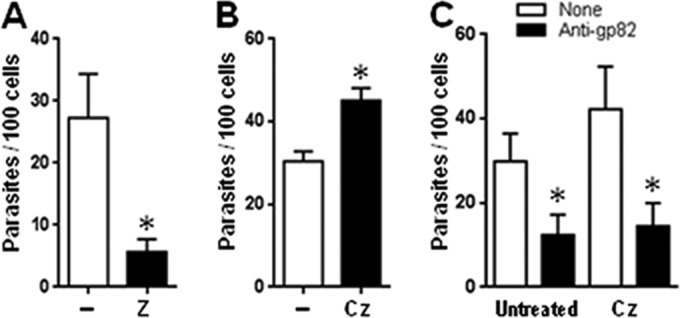

Cruzipain is involved in CL strain MT invasion of host cells.

We assumed that the FN-digesting activity of cruzipain facilitated MT invasion. To confirm that assumption, we tested the effect of Z-(S-Bzl)Cys-Phe-CNH2, an irreversible inhibitor of cysteine proteinase that was previously shown to impair TCT entry into heart muscle cells (19). CL strain metacyclic forms were treated for 15 min with this inhibitor at 10 μM in PBS (diluted from a stock solution at 200 mM in DMSO) or with DMSO at a 1:20,000 dilution in PBS as a control and then incubated for 1 h with HeLa cells. Treatment with the inhibitor significantly reduced MT invasion (Fig. 4A). In a parallel experiment, HeLa cells cultured in DMEM-FBS were treated with 170 nM recombinant cruzipain for 1 h, and after washing in PBS, the untreated and cruzipain-treated cells were incubated with MT for 1 h in serum-free DMEM-BSA medium. The cell susceptibility to MT invasion increased significantly upon cruzipain treatment (Fig. 4B). To check whether binding of gp82 to HeLa cells was altered after treatment with cruzipain, untreated and cruzipain-treated cells were tested for the binding of recombinant gp82. No difference in gp82 binding was observed between untreated and cruzipain-treated cells (data not shown). Invasion assays also were performed in which untreated and cruzipain-treated cells were incubated for 1 with metacyclic forms that were untreated or were pretreated with anti-gp82 monoclonal antibody, and the number of internalized parasites was counted. MT entry into untreated and cruzipain-treated cells was inhibited similarly by anti-gp82 antibody (Fig. 4C). These data indicate that, at least as far as the gp82 receptor is concerned, HeLa cells were not greatly affected by cruzipain action.

FIG 4.

Involvement of T. cruzi cruzipain in host cell invasion. (A) Metacyclic forms (CL strain) were treated for 15 min with the cysteine proteinase inhibitor Z-(S-Bzl)Cys-Phe-CNH2 at 10 μM and then incubated for 1 h with HeLa cells. Values are the means ± SD from five experiments performed in triplicate. Treatment with the inhibitor significantly reduced MT invasion (*, P < 0.0005). (B) HeLa cells cultured in DMEM-FBS were treated with 170 nM recombinant cruzipain for 1 h at 37°C. After washing in PBS, the untreated and cruzipain-treated cells were incubated with MT for 1 h in serum-free DMEM-BSA medium. Values are the means ± SD from three experiments performed in triplicate. Treatment with cruzipain significantly increased the HeLa cell susceptibility to MT invasion (*, P < 0.005). (C) HeLa cells, untreated or treated with recombinant cruzipain as described for panel B, were incubated in DMEM-BSA medium with MT pretreated with anti-gp82 monoclonal antibody or left untreated. Values are the means ± SD from three assays performed in duplicate. Anti-gp82 antibody significantly inhibited the MT invasion of untreated or cruzipain-treated HeLa cells (*, P < 0.05).

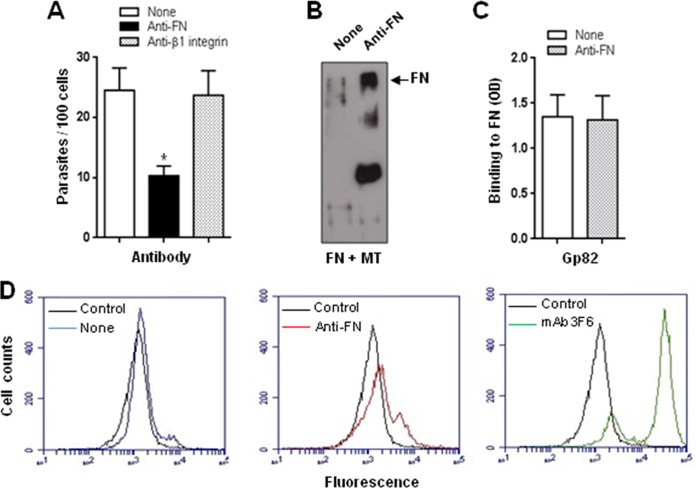

Integrin is not implicated in CL strain MT invasion of host cells.

The β1 family of integrins includes receptors for extracellular matrix ligands, and fibronectin is among them. The involvement of β1 integrin in bacterial and viral internalization has been demonstrated using antibody specific for β1 integrin (3, 4, 37). FN-dependent S. aureus invasion of different cell types is mediated by integrin α5β1 (3, 4), and either FN antiserum or monoclonal antibody specific for β1 integrins dramatically reduces bacterial invasion (2). In the case of T. cruzi MT invasion that apparently is FN independent, β1 integrin would not be implicated. To check the validity of that assumption, we performed experiments in which HeLa cells in DMEM-FBS were treated with anti-FN or anti-β1 integrin antibodies for 15 min, and then, without washing, metacyclic forms were added and incubations proceeded for 1 h before processing for intracellular parasite counting. MT invasion was not inhibited by anti-β1 integrin antibodies but was significantly inhibited by anti-FN antibodies (Fig. 5A). In an attempt to understand why MT invasion is affected by anti-FN antibodies, the following experiments were performed. Metacyclic forms (3 × 107) were incubated for 1 h with 2 μg FN in the absence or presence of anti-FN antibody. After centrifugation, the supernatant was collected and analyzed by immunoblotting using anti-FN antibodies. As in previous assays (Fig. 3F and G), FN was extensively degraded upon incubation with MT, but anti-FN antibody inhibited the process (Fig. 5B). To test the possibility that anti-FN antibody blocked gp82 binding to FN, microtiter plates coated with FN (2 μg/well) were incubated with the recombinant cruzipain gp82 (10 μg/ml) in the absence or in the presence of anti-FN antibody diluted 1:50. Binding of the recombinant gp82 to FN in the absence or in the presence of anti-FN antibody was comparable (Fig. 5C). An additional experiment consisted of incubating MT for 1 h in DMEM-FBS in the absence or in the presence of anti-FN antibody generated in rabbit, followed by processing for FACS analysis. As shown in Fig. 5D, there was a small increase in FN association with parasites in the presence of anti-FN antibody.

FIG 5.

Effect of anti-FN antibody on T. cruzi entry into host cells and on the FN-degrading activity of cruzipain. (A) HeLa cells were left untreated or were treated for 15 min with anti-FN or anti-β1 integrin antibody and diluted 1:100, and then metacyclic forms (CL strain) were added. After 1 h of incubation, the cells were processed for Giemsa staining for intracellular parasite counting. Values are the means ± SD from four experiments performed in duplicate. Anti-FN antibody exhibited a significant inhibitory effect on MT invasion (*, P < 0.0005). (B) Metacyclic forms (CL strain) were incubated for 1 h with 2 μg FN in the absence or presence of anti-FN antibody. Following centrifugation, the supernatant was collected and analyzed by immunoblotting using anti-FN antibody. (C) The recombinant gp82 protein was added to microtiter plates coated with FN and incubated for 1 h in the absence or presence of anti-FN antibody. Values are the means ± SD from three assays performed in triplicate. (D) Metacyclic forms were incubated for 1 h in DMEM-FBS in the absence or presence of anti-FN antibody generated in rabbits and processed for FACS analysis using anti-FN antibody raised in mice. The control refers to parasites that were incubated only with secondary anti-Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-mouse IgG. Parasites that were incubated with monoclonal antibody 3F6 directed to gp82 also are shown.

DISCUSSION

Among the diverse host molecules that T. cruzi encounters before reaching the target cells are the extracellular matrix components, such as fibronectin, laminin, and collagen, which may either facilitate or function as a barrier for parasite migration or interaction with the target cell. Our study using CL strain metacyclic forms has indicated that the parasites do not require FN for target HeLa cell invasion; rather, FN may hinder MT interaction with host cells. The amount of FN from serum present in cell cultures does not preclude MT invasion, because the parasite cruzipain activity is capable of digesting FN. However, the presence of FN at concentrations higher than those of T. cruzi cysteine protease can properly degrade impairs the parasite internalization. Cruzipain has been implicated in host cell entry of TCT through a mechanism that involves the action on the cell-bound kininogen and generation of bradykinin that, upon recognition by the B2 type of bradykinin receptor, triggers the Ca2+ mobilization required for parasite internalization (35). There is no report on FN-digesting activity of TCT cruzipain associated with enhanced TCT invasion capacity. What has been reported is that an 80-kDa enzyme, which is a member of the prolyl oligopeptidase family of serine proteases with specificity for human collagen types I and IV and is found in cell extracts of trypomastigotes, amastigotes, and epimastigotes (16, 38), also hydrolyzes FN, and irreversible inhibitors of that enzyme block TCT entry into nonphagocytic mammalian cells (38, 39).

Studies by several authors, working with blood trypomastigotes or with TCT, have shown that FN enhances the association of parasites with host cells. In addition to the findings that treatment of either mouse peritoneal macrophages or blood trypomastigotes with human plasma FN increased parasite internalization (40), there are reports that nonphagocytic cells, such as cardiomyocytes and fibroblasts, have their association with TCT augmented by FN (7, 41). Based on these observations, it has been suggested that FN bridges parasite-target cell association, leading to enhanced infection. FN also would bridge the interaction of amastigotes with host cells. The addition of exogenous FN, at 200 μg/ml, was reported to increase the uptake of amastigotes by macrophages (10). In our experiments, a 10-fold lower FN concentration was inhibitory for MT invasion of HeLa cells. The observations that TCT and amastigotes use FN as a bridge to interact with target cells are similar to those described for the invasion of bacteria such as S. aureus. Through the FN-binding protein that functions as an invasin, S. aureus interacts with integrin α5β1 through FN-dependent bridging to this host cell receptor (3). A similar mode of interaction may occur in the uptake of TCT by human macrophages, which was blocked by monoclonal antibodies specific for the β1 subunit of the VLA integrin family, with this inhibition correlating with their respective ability to block FN binding to macrophages (42). Different from the finding that antibodies to β1 integrins inhibit S. aureus or TCT entry into target cells, by blocking the formation of FN bridge (2, 42), antibodies to β1 integrins failed to inhibit T. cruzi MT internalization, consistent with the fact that the cell invasion process in this case is FN independent.

MT surface molecule gp82 binds to FN. As gp82 interacts with the host cell receptor and triggers the activation of signaling cascades that lead to Ca2+-mediated actin cytoskeleton disruption and lysosome exocytosis, events that facilitate MT invasion (26, 43), gp82-mediated binding to FN would hamper parasite-host cell interaction. FN may protect host epithelial cells from being invaded by MT if gp82 remains bound to it, but this protective effect can be overcome by the FN-degrading activity of cruzipain. Unlike FN-dependent S. aureus entry into bovine mammary gland epithelial cell lines, which relies on the host cell signaling system associated with protein tyrosine kinase (PTK) activation and is reduced by 95% by the PTK inhibitor genistein (1), the gp82-dependent T. cruzi MT invasion does not require PTK activation (44), it requires the activation of target cell signaling pathways that involve the participation of protein kinase C, mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (43). We have previously found that gp82 binding to target cells is not mediated by extracellular matrix components, such as collagen, laminin, and heparan sulfate (11, 14).

The FN-degrading activity of cruzipain may play an important role in host cell invasion by metacyclic forms of T. cruzi strains that rely on the gp82 molecule to enter target cells. Experiments with metacyclic forms of T. cruzi strain Y82, which also engage gp82 to invade host cells (45), revealed that FN inhibits parasite entry into host cells when present at concentrations higher than the cruzipain activity can fully digest, and that treatment of target cells with the recombinant cruzipain increases parasite internalization, whereas the cysteine proteinase inhibitor has the opposite effect (data not shown). Unlike CL and Y82 strains, G strain metacyclic forms, which are less invasive toward human epithelial cells, lacked cruzipain activity. In G strain, cruzipain is bound to its natural inhibitor, chagasin (36), so that its contribution to the infection process probably is null or negligible. Even secreted chagasin is bound to cruzipain, which would preclude, for instance, its potential inhibitory activity on host cysteine proteinases (36). Apparently, under full nutrient conditions in serum-containing medium, G strain MT enter target cells in a gp82-independent manner (46), compatible with the observation that they are unable to degrade FN and release FN-bound gp82 for interaction with its receptor.

Taken together, the results described here indicate that the gp82-mediated internalization of T. cruzi metacyclic forms does not require an extracellular matrix component to bridge the interaction with the host cell receptor.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP) (grant 11/51475-3) and Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) (grant 300578/2010-5).

We thank Hellena Bonciani Nader for providing TGF-β and for access to the INFAR/UNIFESP Confocal and Flow Cytometry Facility, Pollyana Maria Saud Melo for help in measuring cruzipain activity, and Silene Macedo for technical assistance.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 29 September 2014

REFERENCES

- 1.Dziewanowska K, Patti JM, Deobald CF, Bayles KW, Trumble WR, Bohach GA. 1999. Fibronectin binding protein and host cell tyrosine kinase are required for internalization of Staphylococcus aureus by epithelial cells. Infect. Immun. 67:4673–4678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dziewanowska K, Carson AR, Patti JM, Deobald CF, Bayles KW, Bohach GA. 2000. Staphylococcal fibronectin binding protein interacts with heat shock protein 60 and integrins: role in internalization by epithelial cells. Infect. Immun. 68:6321–6328. 10.1128/IAI.68.11.6321-6328.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sinha B, François PP, Nüsse O, Foti M, Hartford OM, Vaudaux P, Foster TJ, Lew DP, Herrmann M, Krause KH. 1999. Fibronectin-binding protein acts as Staphylococcus aureus invasin via fibronectin bridging to integrin α5β. Cell. Microbiol. 1:101–117. 10.1046/j.1462-5822.1999.00011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Massey RC, Kantzanou MN, Fowler T, Day NP, Schofield K, Wann ER, Berendt AR, Höök M, Peacock SJ. 2001. Fibronectin-binding protein A of Staphylococcus aureus has multiple, substituting, binding regions that mediate adherence to fibronectin and invasion of endothelial cells. Cell. Microbiol. 3:839–851. 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2001.00157.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Molinari G, Talay SR, Valentin-Weigand P, Rohde M, Chhatwal GS. 1997. The fibronectin-binding protein of Streptococcus pyogenes, SfbI, is involved in the internalization of group A streptococci by epithelial cells. Infect. Immun. 65:1357–1363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eucker TP, Konkel ME. The cooperative action of bacterial fibronectin-binding proteins and secreted proteins promote maximal Campylobacter jejuni invasion of host cells by stimulating membrane ruffling. Cell. Microbiol. 14:226–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ouaissi MA, Cornette J, Capron A. 1985. Trypanosoma cruzi: modulation of parasite-cell interaction by plasma fibronectin. Eur. J. Immunol. 15:1096–1101. 10.1002/eji.1830151106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ouaissi MA, Cornette J, Afchain D, Capron A, Gras-Masse H, Tartar A. 1986. Trypanosoma cruzi infection inhibited by peptides modeled from a fibronectin cell attachment domain. Science 234:603–607. 10.1126/science.3094145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ouaissi MA, Cornette J, Capron A. 1986. Identification and isolation of Trypanosoma cruzi trypomastigote cell surface protein with properties expected of a fibronectin receptor. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 19:201–211. 10.1016/0166-6851(86)90002-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Noisin EL, Villalta F. 1989. Fibronectin increases Trypanosoma cruzi amastigote binding to and uptake by murine macrophages and human monocytes. Infect. Immun. 57:1030–1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ramirez MI, Ruiz RC, Araya JE, Franco da Silveira J, Yoshida N. 1993. Involvement of the stage-specific 82-kilodalton adhesion molecule of Trypanosoma cruzi metacyclic trypomastigotes in host cell invasion. Infect. Immun. 61:3636–3641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Neira I, Silva FA, Cortez M, Yoshida N. 2003. Involvement of Trypanosoma cruzi metacyclic trypomastigote surface molecule gp82 in adhesion to gastric mucin and invasion of epithelial cells. Infect. Immun. 71:557–561. 10.1128/IAI.71.1.557-561.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Staquicini DI, Martins RMM, Macedo S, Sasso GRS, Atayde VD, Juliano MA, Yoshida N. 2010. Role of gp82 in the selective binding to gastric mucin during infection with Trypanosoma cruzi. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 4(3):e613. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cortez C, Yoshida N, Bahia D, Sobreira TJ. 2012. Structural basis of the interaction of a Trypanosoma cruzi surface molecule implicated in oral infection with host cells and gastric mucin. PLoS One 7(7):e42153. 10.1371/journal.pone.0042153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giordano R, Chammas R, Veiga SS, Colli W, Alves MJ. 1994. An acidic component of the heterogeneous Tc-85 protein family from the surface of Trypanosoma cruzi is a laminin binding glycoprotein. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 65:85–94. 10.1016/0166-6851(94)90117-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Santana JM, Grellier P, Schrevel J, Teixeira AR. 1997. A Trypanosoma cruzi-secreted 80 kDa proteinase with specificity for human collagen types I and IV. Biochem. J. 325:129–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eakin AE, Mills AA, Harth G, McKerrow JH, Craik CC. 1992. The sequence, organization, and expression of the major cysteine protease (cruzain) from Trypanosoma cruzi. J. Biol. Chem. 267:7411–7420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kosec G, Alvarez V, Cazzulo JJ. 2006. Cysteine proteinases of Trypanosoma cruzi: from digestive enzymes to programmed cell death mediators. Biocell 30:479–490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meirelles MN, Juliano L, Carmona E, Silva SG, Costa EM, Murta AC, Scharfstein J. 1992. Inhibitors of the major cysteinyl proteinase (gp57/51) impair host cell invasion and arrest the intracellular development of Trypanosoma cruzi in vivo. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 52:175–184. 10.1016/0166-6851(92)90050-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scharfstein J, Schmitz V, Morandi V, Capella MMA, Lima APCA, Morrot A, Juliano, Muller-Ester W. 2000. Host cell invasion by Trypanosoma cruzi is potentiated by activation of bradykinin B2 receptors. J. Exp. Med. 192:1289–1299. 10.1084/jem.192.9.1289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lima APCA, Almeida PC, Tersariol ILS, Schmitz V, Schmaier AH, Juliano L, Hirata IY, Müller-Esterl W, Chagas JHR, Scharfstein J. 2002. Heparan sulfate modulates kinin release by Trypanosoma cruzi through the activity of cruzipain. J. Biol. Chem. 277:5875–5881. 10.1074/jbc.M108518200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brener Z, Chiari E. 1963. Variações morfológicas observadas em diferentes amostras de Trypanosoma cruzi. Rev. Inst. Med. Trop. São Paulo 5:220–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yoshida N. 1983. Surface antigens of metacyclic trypomastigotes of Trypanosoma cruzi. Infect. Immun. 40:836–839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Teixeira MMG, Yoshida N. 1986. Stage-specific surface antigens of metacyclic trypomastigotes of Trypanosoma cruzi identified by monoclonal antibodies. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 18:271–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yoshida N, Mortara RA, Araguth MF, Gonzalez JC, Russo M. 1989. Metacyclic neutralizing effect of monoclonal antibody 10D8 directed to the 35- and 50-kilodalton surface glycoconjugates of Trypanosoma cruzi. Infect. Immun. 57:1663–1667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cortez M, Atayde V, Yoshida N. 2006. Host cell invasion mediated by Trypanosoma cruzi surface molecule gp82 is associated with F-actin disassembly and is inhibited by enteroinvasive Escherichia coli. Microbes Infect. 8:1502–1512. 10.1016/j.micinf.2006.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zerlauth G, Wesierska G, Sauermann G. 1988. Fibronectin observed in the nuclear matrix of HeLa tumour cells. J. Cell Sci. 89:415–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tyrrell GJ, Kennedy A, Shokoples SE, Sherburne RK. 2002. Binding and invasion of HeLa and MRC-5 cells by Streptococcus agalactiae. Microbiology 148:3921–3931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morgan J, Garrod D. 1984. HeLa cells form focal contacts that are not fibronectin dependent. J. Cell Sci. 66:133–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hayman EG, Ruoslahti E. 1979. Distribution of fetal bovine serum fibronectin and endogenous rat cell fibronectin in extracellular matrix. J. Cell Biol. 83:255–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ignotz RA, Massagué J. 1986. Transforming growth factor-β stimulates the expression of fibronectin and collagen and their incorporation into the extracellular matrix. J. Biol. Chem. 261:4337–4345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Manque PM, Eichinger D, Juliano MA, Juliano L, Araya J, Yoshida N. 2000. Characterization of the cell adhesion site of Trypanosoma cruzi metacyclic stage surface glycoprotein gp82. Infect. Immun. 68:478–484. 10.1128/IAI.68.2.478-484.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Briones MRS, Souto RP, Stolf BS, Zingales B. 1999. The evolution of two Trypanosoma cruzi subgroups inferred from rRNA genes can be correlated with the interchange of American mammalian fauna in the Cenozoic and has implications to pathogenicity and host specificity. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 104:219–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yoshida N. 2006. Molecular basis of mammalian cell invasion of Trypanosoma cruzi. An. Acad. Bras. Ciênc. 78:87–111. 10.1590/S0001-37652006000100010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Atayde VD, Neira I, Cortez M, Ferreira D, Freymuller E, Yoshida N. 2004. Molecular basis of non virulence of Trypanosoma cruzi clone CL-14. Int. J. Parasitol. 34:851–860. 10.1016/j.ijpara.2004.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Santos CC, Sant'Anna C, Terres A, Cunha-e-Silva NL, Scharfstein J, Lima APCA. 2005. Chagasin, the endogenous cysteine-protease inhibitor of Trypanosoma cruzi, modulates parasite differentiation and invasion of mammalian cells. J. Cell Sci. 118:901–915. 10.1242/jcs.01677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maginnis MS, Forrest JC, Kopecky-Bromberg SA, Dickeson SK, Santoro SA, Zutter MM, Nemerow GR, Bergelson JM, Dermody TS. 2006. β1 1integrin mediates internalization of mammalian reovirus. Virology 80:2760–2770. 10.1128/JVI.80.6.2760-2770.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grellier P, Vendeville S, Joyeau R, Bastos IM, Droberg H, Frappier F, Teixeira AR, Schrevel J, Davioud-Chervet E, Sergheraert C, Santana JM. 2001. Trypanosoma cruzi prolyl oligopeptidase Tc80 is involved in nonphagocytic mammalian cell invasion by trypomastigotes. J. Biol. Chem. 276:47078–47080. 10.1074/jbc.M106017200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bastos IM, Grellier P, Martins NF, Cadavid-Restrepo G, Souza-Ault MR, Augustyns K, Teixeira AR, Schrevel J, Maigret B, Silveira JF, Santana JM. 2005. Molecular, functional and structural properties of the prolyl oligopeptidase of Trypanosoma cruzi (POP Tc80) that is required for parasite entry into mammalian cells. Biochem. J. 388:29–38. 10.1042/BJ20041049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wirth JJ, Kierszenbaum F. 1984. Fibronectin enhances macrophage association with invasive forms of Trypanosoma cruzi. J. Immunol. 133:460–464. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Calvet CM, Meuser M, Almeida D, Meirelles MN, Pereira MC. 2004. Trypanosoma cruzi-cardiomyocyte interaction: role of fibronectin in the recognition process and extracellular matrix expression in vitro and in vivo. Exp. Parasitol. 107:20–30. 10.1016/j.exppara.2004.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fernández MA, Muñoz-Fernández MA, Fresno M. 1993. Involvement of beta 1 integrins in the binding and entry of Trypanosoma cruzi into human macrophages. Eur. J. Immunol. 23:552–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Martins RM, Alves RM, Macedo S, Yoshida N. 2011. Starvation and rapamycin differentially regulate host cell lysosome exocytosis and invasion by Trypanosoma cruzi metacyclic forms. Cell. Microbiol. 13:943–954. 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2011.01590.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Neira I, Ferreira AT, Yoshida N. 2002. Activation of distinct signal transduction pathways in Trypanosoma cruzi isolates with differential capacity to invade host cells. Int. J. Parasitol. 32:405–414. 10.1016/S0020-7519(02)00004-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cortez C, Martins RM, Alves RM, Silva RC, Bilches LC, Macedo S, Atayde VD, Kawashita SY, Briones MRS, Yoshida N. 2012. Differential infectivity by the oral route of Trypanosoma cruzi lineages derived from Y strain. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 6(10):e1804. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ferreira D, Cortez M, Atayde VD, Yoshida N. 2006. Actin cytoskeleton-dependent and -independent host cell invasion by Trypanosoma cruzi is mediated by distinct parasite surface molecules. Infect. Immun. 74:5522–5528. 10.1128/IAI.00518-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]