Abstract

Hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) is a by-product of glycerol metabolism in mycoplasmas and has been shown to cause cytotoxicity for cocultured eukaryotic cells. There appears to be selective pressure for mycoplasmas to retain the genes needed for glycerol metabolism. This has generated interest and speculation as to their function during infection. However, the actual effects of glycerol metabolism and H2O2 production on virulence in vivo have never been assessed in any Mycoplasma species. To this end, we determined that the wild-type (WT) Rlow strain of the avian pathogen Mycoplasma gallisepticum is capable of producing H2O2 when grown in glycerol and is cytotoxic to eukaryotic cells in culture. Transposon mutants with mutations in the genes present in the glycerol transport and utilization pathway, namely, glpO, glpK, and glpF, were identified. All mutants assessed were incapable of producing H2O2 and were not cytotoxic when grown in glycerol. We also determined that vaccine strains ts-11 and 6/85 produce little to no H2O2 when grown in glycerol, while the naturally attenuated F strain does produce H2O2. Chickens were infected with one of two glpO mutants, a glpK mutant, Rlow, or growth medium, and tracheal mucosal thickness and lesion scores were assessed. Interestingly, all glp mutants were reproducibly virulent in the respiratory tracts of the chickens. Thus, there appears to be no link between glycerol metabolism/H2O2 production/cytotoxicity and virulence for this Mycoplasma species in its natural host. However, it is possible that glycerol metabolism is required by M. gallisepticum in a niche that we have yet to study.

INTRODUCTION

Pathogenic mycoplasmas have evolved a strategy for survival within specific niches in their hosts that involves mechanisms such as the loss of unnecessary genes via reductive evolution. Selective pressures exerted on these bacteria dictate that most intact genes should be functional and necessary for some aspect of the mycoplasma's life cycle. During their evolution, most mycoplasmas have lost the genes involved in the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP) and the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, leaving only glycolysis intact for the utilization of their primary carbon source, glucose (1). However, many mycoplasmas (including the avian pathogen Mycoplasma gallisepticum) carry genes that encode transporters and enzymes for the utilization of alternative carbon sources, such as fructose and glycerol (2). Glycerol utilization in Mycoplasma spp. has been a topic of much interest recently, because one of the primary by-products of glycerol metabolism is the cytotoxic reactive oxygen species hydrogen peroxide (H2O2).

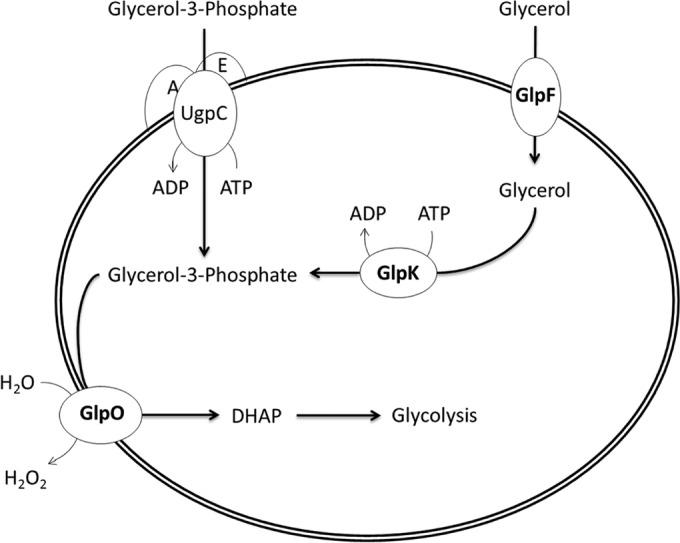

Glycerol catabolism is associated primarily with the proteins encoded by the glp genes (for an overview, see Fig. 1). GlpF is responsible for the transportation of glycerol into the cell. GlpK then phosphorylates glycerol to glycerol-3-phosphate, and GlpO enzymatically converts glycerol-3-phosphate to dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DHAP), which is utilized during glycolysis, and H2O2 (by using water as an electron acceptor [1]). In addition to the Glp proteins, the UgpACE transport system can take up glycerol-3-phosphate directly into the cytoplasm of the bacterium, and the GlpQ protein in Mycoplasma pneumoniae can catabolize glycerophosphocholine into glycerol-3-phosphate as well (3). Grosshennig et al. (4) recently identified an additional glycerol transport protein in M. pneumoniae (GlpU) and characterized the roles of lipoproteins MPN133 and MPN284 in glycerol binding, leading to speculation that they act as a means of capturing glycerol and delivering it to the membrane transport proteins. While glycerol is a potential alternative carbon source, empirical evidence from M. pneumoniae (5, 6) and metabolomic analysis of the M. gallisepticum genome (7) indicate that these pathogens can also utilize glycerol in conjunction with fatty acids to produce cardiolipin, a lipid used for membrane biosynthesis. Thus, there are multiple potential uses for glycerol in mycoplasmas to aid in their survival, but thus far, its actual utilization has been elucidated only for a few Mycoplasma species.

FIG 1.

Overview of glycerol metabolism in Mycoplasma gallisepticum. Free glycerol is transported into the bacterial cell by the uptake facilitator GlpF. Glycerol is then phosphorylated by the glycerol kinase GlpK, producing glycerol-3-phosphate. Alternatively, if the UgpACE ABC transport system is functional in M. gallisepticum, it can take up and transport free glycerol-3-phosphate. Based on the work of others (6), we presume that the glycerol oxidase GlpO is a transmembrane enzyme that converts glycerol-3-phosphate to dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DHAP) and releases hydrogen peroxide as a by-product outside the bacterial cell.

It has long been known that H2O2 is cytotoxic to cells grown in culture, and measuring cytotoxicity has been a common tool in determining the abilities of Mycoplasma spp. to grow in the presence of glycerol as a carbon source. Indeed, in vitro analyses of the growth and cytotoxicity of a Mycoplasma mycoides subsp. mycoides SC GlpO mutant (8) and of both GlpQ (3) and GlpD (9) (homologous to GlpO in other Mycoplasma spp.) mutants of M. pneumoniae have revealed that the loss of these enzymes results in abrogated H2O2 production and a concomitant loss of cytotoxicity toward cocultured eukaryotic cells. Molecular analysis of GlpO in M. mycoides subsp. mycoides SC demonstrated that the “FAD” domain (responsible for binding the flavin adenine dinucleotide cofactor) is essential for its enzymatic activity, H2O2 production, and cytotoxicity (8). Further insight into the mechanism by which H2O2 production may actually cause cytotoxicity toward host cells was gained by immunogold labeling of virulent M. mycoides subsp. mycoides SC cells with anti-GlpO antibodies, which demonstrated that this protein is in fact membrane bound (10) and thus may allow the bacterium to produce H2O2 in the extracellular domain. Hence, H2O2 may be released into the growth medium or may also be directly transferred to attached host cells.

While we know that glycerol metabolism is active in many Mycoplasma spp. (1, 11), glycerol production (and H2O2 production) has never been demonstrated to be associated with the virulence of any mycoplasma in vivo. We sought to bridge this gap by directly assessing the correlation of glycerol metabolism and H2O2 production in vitro with the virulence of M. gallisepticum in vivo. Here we present the results of several genetic knockout experiments with the glpF, glpK, and glpO genes in M. gallisepticum and show that glycerol metabolism in this Mycoplasma species does result in H2O2 production and host cell cytotoxicity in vitro. However, these mutants remain fully virulent in the respiratory tract of their natural host (the chicken) during experimental infection. The implications of the discrepancy between the correlation of H2O2 production with in vitro cytotoxicity and the lack of correlation of H2O2 production with in vivo virulence are discussed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Culture conditions.

M. gallisepticum strains were cultured at 37°C in Hayflick's complete medium (12) until mid-log-phase growth was achieved, as indicated by a color shift from red to orange. Mutants were grown in complete Hayflick's medium containing 50 μg/ml of gentamicin.

M. gallisepticum Rlow transformation and identification of isogenic mutants.

A library of 3,600 Rlow transposon (Tn) mutants was generated via electroporation using plasmid pMT85, as described previously (13). The plasmid carries the mini-Tn4001-gent transposon, which encodes a gentamicin resistance gene. Pools of 30 mutants were grown, and then genomic DNA was extracted. PCR screening of mutant pools for transposon insertions in the glpO, glpF, and glpK genes was performed in 96-well plates by using a gene-specific primer in conjunction with a 5′ or 3′ transposon-specific primer. PCR was run on positive pools in the reverse orientation (reverse gene primer with the opposite-end transposon primer). Pools with positive forward and reverse PCR products that exhibited the anticipated gene size for a transposon insertion were selected for a second round of screening. DNA was extracted from each individual pool member and was screened again as described above. The Tn insertion site was identified using Sanger sequencing, as described previously (14).

Hydrogen peroxide assay.

M. gallisepticum cultures were grown to mid-log phase, and titers were determined by the optical density at 620 nm (OD620). A total of 3 × 109 CFU was then harvested and was centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. Cells were then washed twice in 1 ml HEPES buffer (67.6 mM HEPES, 140 mM NaCl, 7 mM MgCl [pH 7.3]; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) each time. After the second wash, the cells were resuspended in 1 ml HEPES and were incubated for 1 h at 37°C. Glycerol was then added to each culture at a final concentration of 10 mM. After 20 min, Merckoquant peroxide test strips (Merck Millipore International) were used, according to the manufacturer's instructions, to determine the amount of peroxide generated by each culture.

Cytotoxicity assay.

Twelve-well tissue culture plates were seeded with 2 × 105 MRC-5 human lung fibroblasts per well and were incubated at 37°C under 5% CO2 for 24 h in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (DMEM) plus 10% fetal bovine serum until the cells reached confluence. M. gallisepticum cultures were started so as to coordinate mid-log-phase growth with the time of MRC-5 confluence. Each M. gallisepticum culture was centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C and was then washed twice with 1 ml HEPES buffer. After the second wash, cells were resuspended in 1 ml DMEM plus 10% fetal bovine serum. The medium in the wells of the MRC-5 cells was removed, and 1,000 M. gallisepticum cells were inoculated into each well and were incubated at 37°C under 5% CO2 for 1 h. Glycerol was then added to wells (as indicated in Fig. 4) at a final concentration of 10 mM, and the cells were incubated for an additional 24 h. Medium was then removed from the wells, and cell monolayers were stained with 0.1% crystal violet for 15 min. Cytopathic effects (CPE) were noted when the cells rounded up and lifted off from the bottoms of the plates.

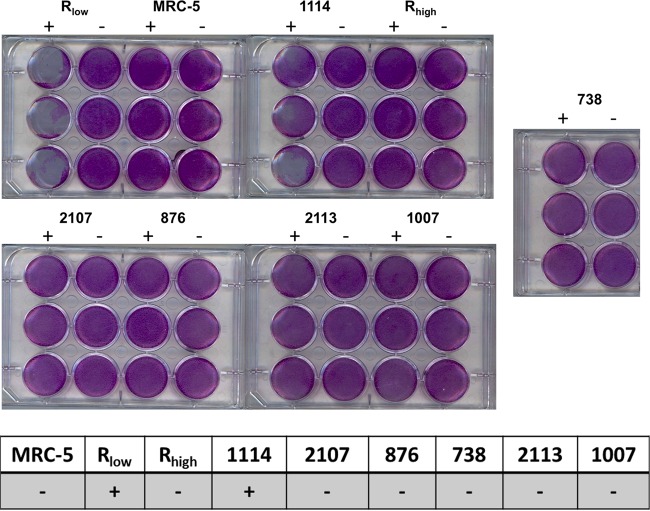

FIG 4.

Cytotoxicities of M. gallisepticum glp mutants when cultured with MRC-5 human lung fibroblasts. (Top and center) Wells of confluent MRC-5 cells stained with crystal violet after inoculation with M. gallisepticum strains in the presence (+) or absence (−) of glycerol. Cytotoxicity was determined by the presence or absence of a cytopathic effect on MRC-5 cells. One thousand M. gallisepticum cells were inoculated into 12-well plates with MRC-5 cells grown to confluence. No cytopathic effects were observed for any strain when grown in the presence of glucose instead of glycerol. (Bottom) Presence (+) or absence (−) of cytotoxicity for MRC-5 cells cultured alone or with M. gallisepticum strains.

Attachment assay.

M. gallisepticum strains were radiolabeled in Hayflick's broth supplemented with [methyl-3H]thymidine (10 μCi/ml), and the specific activity (calculated as cpm/CFU) of each culture was determined as measured by liquid scintillation (cpm) and optical density at 620 nm (CFU). MRC-5 lung fibroblasts seeded at 1 × 105/well were incubated for 24 h prior to exposure to radiolabeled M. gallisepticum (at a multiplicity of infection [MOI] of 1,000 for 1 h at 37°C) in Hayflick's broth. Monolayers were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and were lysed with 200 μl of 50 mM NaOH, and activity was measured by liquid scintillation. The numbers of attached M. gallisepticum cells per well were calculated as the test activity (measured in cpm) divided by the specific activity of each strain (initial culture cpm/CFU).

Animals.

Four-week-old female specific-pathogen-free White Leghorn chickens (Spafas, North Franklin, CT) were used in this study. Upon arrival, the chickens were divided into groups of 10, tagged, placed in HEPA-filtered isolators, and allowed to acclimate for 1 week prior to experimentation. Nonmedicated feed and water were provided M. mycoides throughout the experimental period. The chicken study procedures described here were in accordance with state and federal policies to ensure the humane use and care of research animals as approved by the University of Connecticut Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC).

In vivo infection study.

Stocks of each M. gallisepticum culture were grown at 37°C with shaking at 130 rpm in fresh Hayflick's complete medium for 5 h prior to animal inoculation. M. gallisepticum concentrations were determined by the OD620, and 10-fold serial dilutions were used to assess color-changing units (CCU) in order to ensure that the cells measured were viable. Chickens were challenged intratracheally as described previously (13), with 1 × 108 CFU in 200 μl of each M. gallisepticum culture on days −2 and 0. Control chickens received 200 μl Hayflick's complete medium on days −2 and 0. Chickens were euthanized and were immediately necropsied on day 14 postinfection (p.i.), and the trachea was collected from each bird. Gross and histopathological analyses of the tracheal lesions were conducted as described by Gates et al. (15).

Statistics.

Statistical comparisons were conducted using analysis of variance (ANOVA), or the nonparametric ANOVA on ranks for tracheal lesion scores, with a Newman-Keuls post hoc test for multiple pairwise comparisons. Data were analyzed using GraphPad Prism, version 5 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Differences were considered significant if the P value was <0.05.

RESULTS

Generation of glp mutants.

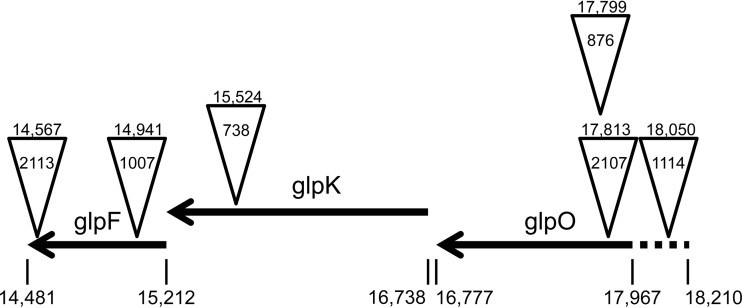

In order to assess the role of the glycerol uptake and processing enzymes in the virulence of M. gallisepticum, we screened our previously described transposon library generated from the M. gallisepticum wild-type (WT) strain Rlow (13) for isogenic mutants with alterations in the glpO, glpK, and glpF genes by using the haystack mutagenesis method. Insertion sites were mapped by Sanger sequencing using a unique outwardly directed primer. We identified two glpO mutants (mutants 2107 and 876), one glpK mutant (mutant 738), and two glpF mutants (mutants 1007 and 2113) (Fig. 2). An additional mutant was identified in the intergenic region upstream of the glp operon (mutant 1114).

FIG 2.

Map of the glp operon and Tn insertion sites for the different mutants tested. Arrows indicate open reading frames, with the genomic positions of the start and stop sites given below. Inverted triangles indicate Tn insertion sites. The mutant designation is given inside each triangle, and the insertion point is given above each triangle. The dashed line indicates the putative promoter region for the glp operon.

H2O2 production by M. gallisepticum strains and glp mutants with glycerol as a carbon source.

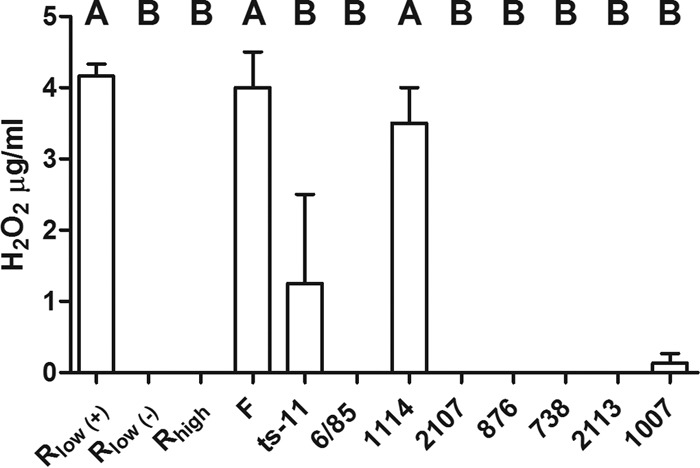

The amount of H2O2 can be measured directly in growth medium with Millipore semiquantitative test strips. We used these strips to determine the amounts of H2O2 produced by multiple strains of M. gallisepticum. When Rlow was grown in glycerol for 20 min, an average of 4.25 μg/ml of H2O2 could be detected; however, this effect was abrogated in the absence of glycerol (Fig. 3). Mutant 1114 (with a Tn insertion in the intergenic region upstream of the glp operon) produced wild-type levels of H2O2 when grown in glycerol (3.5 μg/ml), thus indicating that the mere presence of a Tn does not interfere with glycerol metabolism/H2O2 production. Inactivation of the glpO, glpK, or glpF gene by Tn insertion rendered each mutant unable to produce detectable levels of H2O2 when grown in glycerol. Additionally, we tested the abilities of attenuated vaccine strains and the high-passage-number R strain Rhigh (with a previously noted inactivating mutation in the glpK gene [16]) to produce H2O2 in the presence of glycerol. Of the attenuated strains, only the F strain was capable of producing WT levels of H2O2 (4.0 μg/ml; not significantly different from those produced by Rlow) when grown in glycerol. ts-11 produced low levels of H2O2 in some experiments (1.25 μg/ml), but its H2O2 production clustered statistically with that of Rlow grown in the absence of glycerol and was significantly different from that of Rlow grown in glycerol (P < 0.05).

FIG 3.

H2O2 production by M. gallisepticum strains and glp mutants grown in glycerol as the carbon source. The concentrations of H2O2 were measured in the growth media of M. gallisepticum strains grown in glycerol by using Merckoquant peroxide test strips. Rlow was also grown without the addition of glycerol (−). Statistical significance was determined by ANOVA with a Newman-Keuls post hoc test for multiple pairwise comparisons. Different capital letters above the data indicate statistically significant differences (P < 0.05).

Glycerol-dependent H2O2 production induces cytotoxicity in cocultured eukaryotic cells.

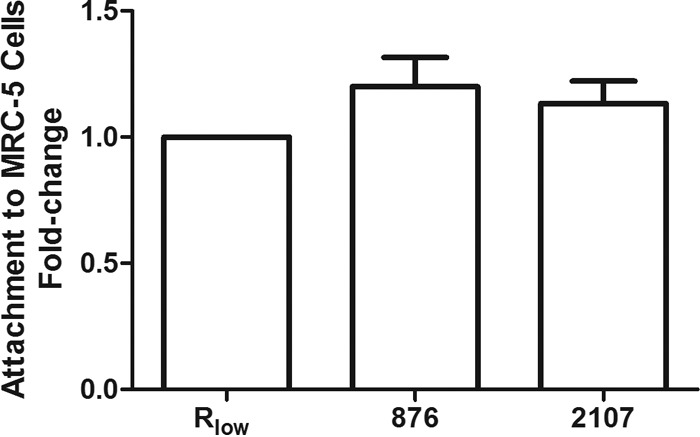

To investigate the cytotoxic nature of H2O2 released from M. gallisepticum due to glycerol metabolism, MRC-5 human lung fibroblasts were infected in the presence and absence of glycerol. Uninfected cells served as a negative control. The WT strain Rlow was able to induce cytopathic effects (CPE) in the presence of 10 mM glycerol 24 h after infection but induced no CPE without the addition of exogenous glycerol (Fig. 4). An intermediate phenotype was observed for the intergenic mutant 1114, with some wells exhibiting clearly demonstrable CPE and others less so. None of the glp mutants induced CPE in the presence of glycerol. Of note, Tn insertions in the glp genes did not affect the abilities of the mutants to bind to MRC-5 cells (Fig. 5); thus, their lack of cytotoxicity was not associated with an inability to attach to, and maintain intimate contact with, eukaryotic cells. We additionally tested the ability of strain Rhigh to induce CPE in this system, but none was detected. When strains were grouped according to the findings of the H2O2 tests, cytotoxic strains clustered together with no significant difference among them, but they were significantly different from noncytotoxic strains (which clustered together as well). Thus, there appeared to be a correlation between H2O2 production/glycerol metabolism and cytotoxicity in vitro.

FIG 5.

glp mutants 876 and 2107 maintain wild-type levels of attachment to eukaryotic cells. M. gallisepticum strains were radiolabeled, and their abilities to attach to MRC-5 cells were measured by liquid scintillation. Data represent the mean fold change (± standard error of the mean) in attachment to MRC-5 cells from Rlow (whose value is set at 1), as measured over three separate experiments. No statistical difference was observed among the groups, as determined by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's multiple-comparison post hoc test (with Rlow serving as the control group for comparison).

Glycerol metabolism and H2O2 production are not associated with M. gallisepticum virulence in the respiratory tracts of chickens.

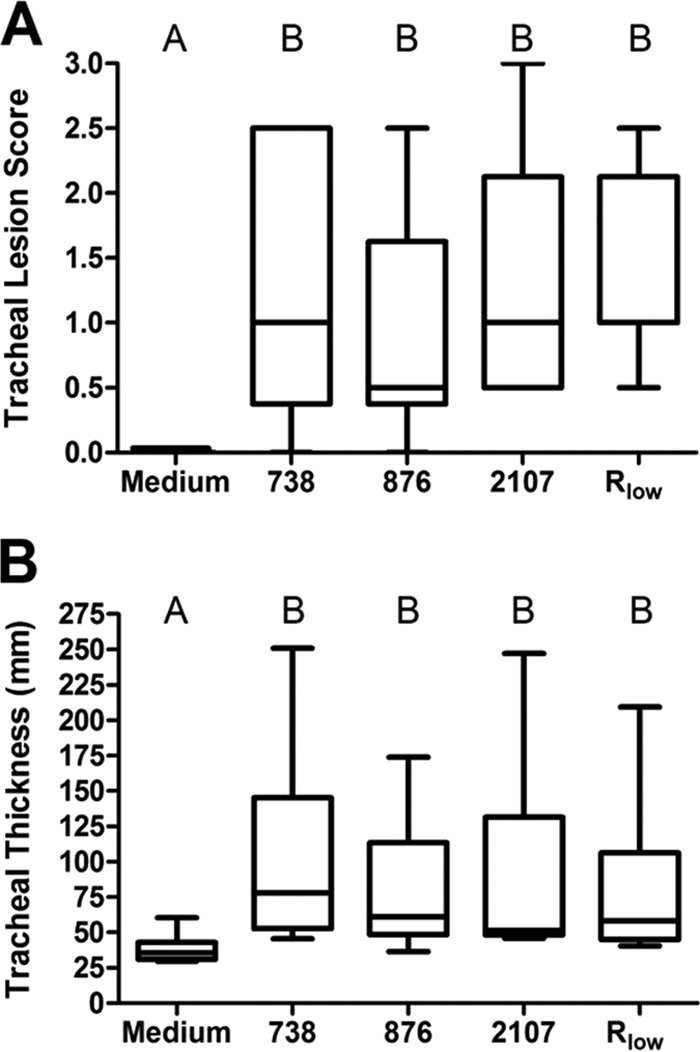

The relative virulence of the glp mutant strains was experimentally assessed in chickens as described previously (14). Groups of 10 female White Leghorn chickens were inoculated intratracheally with either Hayflick's medium as a negative control, Rlow as a positive control, glpO mutant 2107 or 876, or glpK mutant 738. Two similar experiments had been conducted previously with essentially the same results. Tracheal lesions were scored for severity, and tracheal mucosal thickness was measured (Fig. 6). Chickens inoculated with medium alone differed significantly from those inoculated with Rlow, both in terms of tracheal lesion scores and in terms of mucosal thickness (P < 0.05). All three glp mutants clustered statistically with Rlow and were different from medium alone, again both in terms of lesion scores and in terms of mucosal thickness. Thus, H2O2 production appeared to be completely dispensable for M. gallisepticum virulence in the chicken respiratory tract, a primary natural niche for this pathogen. Furthermore, while glycerol metabolism and H2O2 production appeared to correlate with in vitro cytotoxicity, there appeared to be no link between glycerol metabolism/H2O2 production and the virulence of M. gallisepticum.

FIG 6.

Tracheal lesion scores and measurements of thickness of histologic sections from chickens intratracheally infected with M. gallisepticum glp mutants. Chickens inoculated with Mycoplasma growth medium alone served as negative controls, and those inoculated with the WT strain Rlow served as positive controls. Box plots represent the 25th and 75th percentiles, with the median score in between, and whiskers show the minimum and maximum for each group. Groups were compared by ANOVA (for thickness) or ANOVA on ranks (for lesion scores), with a Newman-Keuls post hoc multiple pairwise comparison using GraphPad Prism. Different capital letters above the data indicate statistically significant differences (P < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

Much research has been dedicated recently to identifying and determining the functionality of glycerol metabolism genes and their products. Much of this work has focused on identifying H2O2 as a by-product of glycerol metabolism and demonstrating that H2O2-producing Mycoplasma spp. are cytotoxic when cocultured with eukaryotic cells. Genome sequencing has revealed that M. gallisepticum possesses the glp genes necessary for glycerol metabolism (2, 16), and earlier work showed that this pathogen can grow in the presence of glycerol (11). The studies presented here confirm these earlier reports and further demonstrate that H2O2 is produced during the metabolism of glycerol and that glycerol metabolism results in cytotoxicity toward cocultured eukaryotic cells. However, this is the first report of the assessment of the role of glycerol metabolism in the virulence of any Mycoplasma species in vivo. To our surprise, this seemingly important enzymatic reaction had no bearing on the virulence of M. gallisepticum in the trachea of its natural host. We have found that lesions in tracheas (the primary site of infection) are a more consistent indicator of virulence than lesions in air sacs or lungs. Therefore, our measure of virulence is based on tracheal lesions. We utilized three different glp mutants and repeated the in vivo experiments, with similar results in replicate experiments. Thus, we have demonstrated that there is no link between glycerol metabolism/H2O2 production/cytotoxicity and virulence in the common host of Mycoplasma gallisepticum. These results indicate that glycerol metabolism, H2O2 production, and cytotoxicity do not correlate with virulence in all mycoplasmas.

There is direct evidence for the necessity of utilization of alternative carbon sources in the virulence of the closely related insect and plant pathogens in the genus Spiroplasma. As in previous studies on Mycoplasma spp., the presence of glpO has been associated with the virulence of Spiroplasma culicicola and Spiroplasma taiwanense in mosquitoes, and its loss has been associated with attenuation of the virulence of Spiroplasma taiwanense and Spiroplasma sabaudiense (17) in these insects. Perhaps more convincingly, direct evidence of the necessity of fructose as a carbon source and its link to virulence in vivo has been provided through infection studies of fruR Tn mutants of Spiroplasma citri in its natural host, the periwinkle plant (18). The fruR mutants showed marked attenuation during infection, and virulence was restored upon complementation. Interestingly, M. gallisepticum encodes the genes necessary for fructose transport and has been shown previously to grow with fructose as a carbon source (11). Elucidation of the importance of alternative carbon sources (other than glycerol) for the growth and virulence of Mycoplasma spp. is warranted.

Given the selective pressure on Mycoplasma spp. to reduce unnecessary gene content, it is surprising that the glp genes are maintained yet are not involved in virulence in the tracheas of chickens. Multiple genomic studies have correlated the presence of genes involved in glycerol metabolism and/or H2O2 production with the relative virulence of field strains of different Mycoplasma spp. Indeed, there appears to be a direct correlation between H2O2 production during glycerol metabolism and the relative virulence of M. mycoides subsp. mycoides SC strains. Vilei and Frey (19) report that all the African field strains of M. mycoides subsp. mycoides SC contain the gts transport system (the glycerol transport system in this pathogen) and produce high levels of H2O2, while the relatively attenuated European strains are missing two of the gts genes and do not produce H2O2 in the presence of glycerol, an observation also made by Rice et al. (20). However, it is not currently known if other affected genes contribute to (or even are completely responsible for) attenuation in the European strains of M. mycoides subsp. mycoides SC.

Mycoplasma bovis and Mycoplasma agalactiae field strains appear to produce H2O2, but serial passage of one M. bovis strain (119B96) resulted in dramatically reduced H2O2 production and the loss of an associated protein (21). In a similar vein, we have shown that the high-passage-number attenuated Rhigh strain of M. gallisepticum has an inactivating mutation in the glpK gene (16), and we show in this work that this strain does not produce H2O2. Two other attenuated M. gallisepticum vaccine strains (ts-11 and 6/85) also produce little to no H2O2 in the presence of glycerol. These findings support the notion that Mycoplasma spp. experience selective pressure to maintain glycerol metabolism capabilities in the wild but often lose these genes when such pressures are removed under laboratory conditions. An interesting piece of this puzzle then arises from our findings with the naturally attenuated F strain of M. gallisepticum, which retained WT levels of H2O2 production in culture. The F strain has dramatically reduced virulence in chickens yet persists at WT levels in the respiratory tracts of chickens (22). The finding that this attenuated strain produces H2O2 supports the conclusion that H2O2 production does not affect M. gallisepticum virulence in chickens. However, it should be noted that the F strain is fully virulent in turkeys, providing a possible natural niche in which glycerol metabolism/H2O2 production may undergo the selective pressures for maintenance of this metabolic capability. Should this be the case, it is possible that glycerol metabolism is a species- or niche-specific virulence factor. This raises questions regarding the availability of glycerol in the tracheas of chickens, the relative resistance of chickens to H2O2 in their tracheas, the possibility that other tissue/organ systems in chickens (not assessed in this study) are negatively impacted by M. gallisepticum H2O2 production, and the activity of the glp genes of M. gallisepticum during infection. More work is needed to answer these questions and to test the hypothesis of species specificity as a driver of the maintenance of genes necessary for glycerol metabolism in M. gallisepticum.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Kathryn Korhonen and Kara Rogers for assistance with animal experiments, Rachel Burns for assistance in animal necropsy, and Salvatore Frasca for assistance with animal inoculations.

We thank the Center of Excellence for Vaccine Research for funding this work.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 25 August 2014

REFERENCES

- 1.Halbedel S, Hames C, Stulke J. 2007. Regulation of carbon metabolism in the mollicutes and its relation to virulence. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 12:147–154. 10.1159/000096470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Papazisi L, Gorton TS, Kutish G, Markham PF, Browning GF, Nguyen DK, Swartzell S, Madan A, Mahairas G, Geary SJ. 2003. The complete genome sequence of the avian pathogen Mycoplasma gallisepticum strain Rlow. Microbiology 149(Part 9):2307–2316. 10.1099/mic.0.26427-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schmidl SR, Otto A, Lluch-Senar M, Piñol J, Busse J, Becher D, Stülke J. 2011. A trigger enzyme in Mycoplasma pneumoniae: impact of the glycerophosphodiesterase GlpQ on virulence and gene expression. PLoS Pathog. 7:e1002263. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grosshennig S, Schmidl SR, Schmeisky G, Busse J, Stulke J. 2013. Implication of glycerol and phospholipid transporters in Mycoplasma pneumoniae growth and virulence. Infect. Immun. 81:896–904. 10.1128/IAI.01212-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yus E, Maier T, Michalodimitrakis K, van Noort V, Yamada T, Chen WH, Wodke JA, Güell M, Martínez S, Bourgeois R, Kühner S, Raineri E, Letunic I, Kalinina OV, Rode M, Herrmann R, Gutiérrez-Gallego R, Russell RB, Gavin AC, Bork P, Serrano L. 2009. Impact of genome reduction on bacterial metabolism and its regulation. Science 326:1263–1268. 10.1126/science.1177263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Snowden N, Wilson PB, Longson M, Pumphrey RS. 1990. Antiphospholipid antibodies and Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection. Postgrad. Med. J. 66:356–362. 10.1136/pgmj.66.775.356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bautista EJ, Zinski J, Szczepanek SM, Johnson EL, Tulman ER, Ching WM, Geary SJ, Srivastava R. 2013. Semi-automated curation of metabolic models via flux balance analysis: a case study with Mycoplasma gallisepticum. PLoS Comput. Biol. 9:e1003208. 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bischof DF, Vilei EM, Frey J. 2009. Functional and antigenic properties of GlpO from Mycoplasma mycoides subsp. mycoides SC: characterization of a flavin adenine dinucleotide-binding site deletion mutant. Vet. Res. 40(4):35. 10.1051/vetres/2009018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hames C, Halbedel S, Hoppert M, Frey J, Stulke J. 2009. Glycerol metabolism is important for cytotoxicity of Mycoplasma pneumoniae. J. Bacteriol. 191:747–753. 10.1128/JB.01103-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pilo P, Vilei EM, Peterhans E, Bonvin-Klotz L, Stoffel MH, Dobbelaere D, Frey J. 2005. A metabolic enzyme as a primary virulence factor of Mycoplasma mycoides subsp. mycoides small colony. J. Bacteriol. 187:6824–6831. 10.1128/JB.187.19.6824-6831.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taylor RR, Mohan K, Miles RJ. 1996. Diversity of energy-yielding substrates and metabolism in avian mycoplasmas. Vet. Microbiol. 51:291–304. 10.1016/0378-1135(96)00039-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hayflick L, Koprowski H. 1965. Direct agar isolation of mycoplasmas from human leukaemic bone marrow. Nature 205:713–714. 10.1038/205713b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Szczepanek SM, Frasca S, Jr, Schumacher VL, Liao X, Padula M, Djordjevic SP, Geary SJ. 2010. Identification of lipoprotein MslA as a neoteric virulence factor of Mycoplasma gallisepticum. Infect. Immun. 78:3475–3483. 10.1128/IAI.00154-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hudson P, Gorton TS, Papazisi L, Cecchini K, Frasca S, Jr, Geary SJ. 2006. Identification of a virulence-associated determinant, dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase (lpd), in Mycoplasma gallisepticum through in vivo screening of transposon mutants. Infect. Immun. 74:931–939. 10.1128/IAI.74.2.931-939.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gates AE, Frasca S, Nyaoke A, Gorton TS, Silbart LK, Geary SJ. 2008. Comparative assessment of a metabolically attenuated Mycoplasma gallisepticum mutant as a live vaccine for the prevention of avian respiratory mycoplasmosis. Vaccine 26:2010–2019. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Szczepanek SM, Tulman ER, Gorton TS, Liao X, Lu Z, Zinski J, Aziz F, Frasca S, Jr, Kutish GF, Geary SJ. 2010. Comparative genomic analyses of attenuated strains of Mycoplasma gallisepticum. Infect. Immun. 78:1760–1771. 10.1128/IAI.01172-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lo WS, Ku C, Chen LL, Chang TH, Kuo CH. 2013. Comparison of metabolic capacities and inference of gene content evolution in mosquito-associated Spiroplasma taiwanense and S. taiwanense. Genome Biol. Evol. 5:1512–1523. 10.1093/gbe/evt108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gaurivaud P, Danet JL, Laigret F, Garnier M, Bove JM. 2000. Fructose utilization and phytopathogenicity of Spiroplasma citri. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 13:1145–1155. 10.1094/MPMI.2000.13.10.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vilei EM, Frey J. 2001. Genetic and biochemical characterization of glycerol uptake in Mycoplasma mycoides subsp. mycoides SC: its impact on H2O2 production and virulence. Clin. Diagn. Lab. Immunol. 8:85–92. 10.1128/CDLI.8.1.85-92.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rice P, Houshaymi BM, Abu-Groun EA, Nicholas RA, Miles RJ. 2001. Rapid screening of H2O2 production by Mycoplasma mycoides and differentiation of European subsp. mycoides SC (small colony) isolates. Vet. Microbiol. 78:343–351. 10.1016/S0378-1135(00)00305-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khan LA, Miles RJ, Nicholas RA. 2005. Hydrogen peroxide production by Mycoplasma bovis and Mycoplasma agalactiae and effect of in vitro passage on a Mycoplasma bovis strain producing high levels of H2O2. Vet. Res. Commun. 29:181–188. 10.1023/B:VERC.0000047506.04096.06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kleven SH, Fan HH, Turner KS. 1998. Pen trial studies on the use of live vaccines to displace virulent Mycoplasma gallisepticum in chickens. Avian Dis. 42:300–306. 10.2307/1592480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]