Abstract

Mutations in the nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-containing protein 2 (NOD2) play an important role in the pathogenesis of Crohn's disease. NOD2 is an intracellular pattern recognition receptor (PRR) that senses bacterial peptidoglycan (PGN) structures, e.g., muramyl dipeptide (MDP). Here we focused on the effect of more-cross-linked, polymeric PGN fragments (PGNpol) in the activation of the innate immune system. In this study, the effect of combined NOD2 and Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) stimulation was examined compared to single stimulation of the NOD2 receptor alone. PGNpol species derived from a lipoprotein-containing Staphylococcus aureus strain (SA113) and a lipoprotein-deficient strain (SA113 Δlgt) were isolated. While PGNpol constitutes a combined NOD2 and TLR2 ligand, lipoprotein-deficient PGNpolΔlgt leads to activation of the immune system only via the NOD2 receptor. Murine bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (BMDCs), J774 cells, and Mono Mac 6 (MM6) cells were stimulated with these ligands. Cytokines (interleukin-6 [IL-6], IL-12p40, and tumor necrosis factor alpha [TNF-α]) as well as DC activation and maturation parameters were measured. Stimulation with PGNpolΔlgt did not lead to enhanced cytokine secretion or DC activation and maturation. However, stimulation with PGNpol led to strong cytokine secretion and subsequent DC maturation. These results were confirmed in MM6 and J774 cells. We showed that the NOD2-mediated activation of DCs with PGNpol was dependent on TLR2 costimulation. Therefore, signaling via both receptors leads to a more potent activation of the immune system than that with stimulation via each receptor alone.

INTRODUCTION

Crohn's disease is a systemic inflammatory disease, and together with ulcerative colitis, it forms the complex of inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD). Mutations within the NOD2 gene, encoding nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-containing protein 2 (NOD2), have been identified as risk factors for the development of Crohn's disease (1–3). NOD2 is an intracellular pattern recognition receptor that senses peptidoglycan (PGN) fragments, such as muramyl dipeptide (MDP), derived from Gram-positive bacteria, to activate a cascade of reactions which consecutively lead to the activation of the transcription factor NF-κB (4).

Dendritic cells (DCs) are important professional antigen-presenting cells (APCs) in the intestine (5, 6) and are crucial for T cell activation and polarization (7, 8). Depending on the antigen, DCs can promote either inflammation or tolerance (9). DCs are thought to contribute to the pathogenesis of Crohn's disease (10, 11) by inducing T cell activation via antigen presentation. As an example, colonic CD11c+ DCs isolated from inflamed parts of the gut from IBD patients showed an increased expression of Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2), TLR4, and the costimulatory molecule CD40 compared to DCs from noninflamed areas or DCs from healthy controls (12). Also, the ability of DCs to induce tolerogenic regulatory T cells might be lost in Crohn's disease patients (13).

PGN fragments with a low degree of cross-linking, such as PGN monomers, have been shown to be natural ligands for the NOD2 receptor (14). However, the role of more-cross-linked PGN fragments, so called polymeric PGN (PGNpol), and their effect in stimulating immune cells are still unclear, as even highly purified PGNpol might be contaminated with potent immune-stimulating lipoproteins (15). Using Bacillus anthracis peptidoglycan, it has been shown that polymeric PGN is a more potent activator of innate immune cells than MDP or monomeric PGN (16).

The importance of PGN in inflammation was recently demonstrated in mice infected with wild-type (WT) Staphylococcus aureus and corresponding O-acetyltransferase A (OatA) mutants. In S. aureus, PGN is modified by an O-acetyltransferase at the C-6 OH position of N-acetylmuramic acid (17). This modification, which occurs only in pathogenic staphylococcal strains (18), confers complete resistance of PGN to lysozyme, while mutations of the oatA gene result in a PGN that is sensitive to lysozyme (17, 19). In comparing PGNpol from WT S. aureus with PGN from the oatA-deficient mutant (S. aureus ΔoatA), it turned out that WT PGNpol strongly suppressed interleukin-1β (IL-1β) secretion and inflammasome activation, while the PGNpol of the S. aureus ΔoatA strain strongly increased IL-1β secretion and inflammasome activation (20). In the absence of oatA, PGN is degraded by lysozyme, resulting in a number of PGN breakdown products which boost inflammation. Thus, modification of PGN by O-acetylation in S. aureus is an efficient immune escape mechanism.

The interplay between the NOD2 and TLR2 pathways is complex, and interactions between both receptors seem to contribute to activation or inhibition of the immune system (21). NOD2 was shown to be part of an inhibitory system which blocks TLR2-mediated inflammation, resulting in less Th1 cytokine production after stimulation (22). Additionally, activation of mouse peritoneal macrophages with the NOD2 ligand MDP resulted in downregulation of TLR2/1 signaling-mediated IL-1β expression (23). However, different studies suggest a synergistic role for NOD2 and TLR2 (24).

Additionally, it is still controversially discussed whether PGN interacts with TLR2. PGN isolated from either Gram-negative or Gram-positive bacteria is reported not to be sensed by TLR2 (25). However, stimulation of primary mouse keratinocytes (MKs) with PGNpol from S. aureus SA113 resulted in internalization of the molecule and colocalization with NOD2 and TLR2 receptors and induced subsequent host immune responses (26). Additionally, lipoproteins of S. aureus have been shown to activate TLR2 (26–29).

To further elucidate the interaction between the NOD2 and TLR2 pathways, we investigated the innate immune sensing of two different types of naturally occurring S. aureus-derived PGN polymers. PGN of S. aureus SA113 contains traces of lipoproteins. This PGN is referred to as the wild-type PGN. The other PGNpol fraction was derived from the S. aureus SA113 Δlgt mutant, which is unable to lipidate prolipoproteins and whose PGNpol therefore does not contain lipoproteins (30).

By studying the effects of PGNpol from the wild type and that from the Δlgt mutant (PGNpolΔlgt) on DC maturation and activation as well as cytokine secretion, we showed that PGNpol is a potent stimulator of the immune system, through both NOD2 and TLR2, while PGNpolΔlgt, as a selective NOD2 ligand, does not induce host immune responses. However, the addition of the synthetic TLR2 ligand Pam3Cys (P3C) to PGNpolΔlgt resulted in activation of the host immune response. Costimulation with the NOD2 ligand PGNpolΔlgt and the TLR2 ligand P3C had a synergistic effect on cytokine production, suggesting that NOD2-dependent activation of DCs with PGN requires TLR2 costimulation by lipoproteins.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Charles River (Sulzfeld, Germany). NOD2−/− mice were a kind gift from Tilo Biedermann (Department of Dermatology, Eberhard Karls University, Tübingen, Germany). All mice were housed under specific-pathogen-free conditions at the animal facilities of the University of Tübingen according to German law and European guidelines. All experiments were approved by the local authorities (Regierungspräsidium Tübingen; Anzeigenummer 1.12.11).

Isolation of BMDCs.

Bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (BMDCs) were isolated by flushing the bone marrow from the femurs and tibias of 8- to 14-week-old WT and NOD2−/− mice according to a previously described method (31), with minor modifications.

Cells were harvested at day 8 and used to evaluate the effects of stimulation with different bacterial PGN products on cytokine release and expression of surface markers, as described below.

Stimulation of BMDCs.

DCs were stimulated with different ligands, e.g., P3C for TLR2, lipopolysaccharide (LPS) for TLR4, or MDP and PGNpolΔlgt for NOD2, or stimulated with the combined NOD2 and TLR2 ligand PGNpol, at a dose of 1 μg/ml if not otherwise mentioned. The different PGN types were used at a concentration of 10 μg/ml if not otherwise mentioned. After 24 h, supernatants were harvested and analyzed for tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), IL-6, and IL-12p40 cytokine concentrations. Additionally, the expression of DC activation and maturation surface markers major histocompatibility complex class II (MHC-II) and CD40 was determined by flow cytometry.

Cytokine analysis by ELISA.

Concentrations of murine IL-6, IL-8, IL-12p40, and TNF-α in cell culture supernatants were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) according to the manufacturer's protocol (BD Bioscience, Heidelberg, Germany).

Fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis.

Immature DCs were harvested and stimulated for 24 h with different NOD2 or TLR ligands. Cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and 1% fetal calf serum (FCS). Fc-Block was used to prevent nonspecific binding of antibodies. DCs were incubated for 30 min at 4°C with a fluorochrome-conjugated antibody. The following antibodies were used for staining: allophycocyanin-conjugated anti-mouse CD11c, fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-mouse CD40, CD80, and CD86, phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated anti-mouse TLR2 and TLR4 (all antibodies from BD Pharmingen), and appropriate isotype controls. After another washing step (twice), the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA). A total of 5 × 104 cells were analyzed using a FACS LSR Fortessa flow cytometer (BD Bioscience, Heidelberg, Germany). Data were analyzed with FlowJo 7.6.4 (TreeStar Inc.).

Culture and stimulation of J774 cells and MM6 cells.

J774 cells were grown in VLE-RPMI 1640 medium with stable glutamine (Biochrom, Berlin, Germany), 10% FCS, 1% nonessential amino acids, 1% sodium pyruvate, and 0.5% mercaptoethanol. A total of 1 × 106 cells were seeded per well and incubated for 1 h. J774 cells were stimulated with Pam3Cys or PGNpolΔlgt for 48 h. After stimulation, supernatants were collected, and cytokine (TNF-α) concentrations were determined by ELISA (BD Bioscience, Heidelberg, Germany). Mono Mac 6 (MM6) cells were cultured in VLE-RPMI 1640 medium with stable glutamine (Biochrom, Berlin, Germany), 10% FCS, 1% nonessential amino acids, and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. After stimulation of the Mono Mac 6 cells with Pam3Cys and PGNpolΔlgt for 48 h, the supernatants were collected, and the concentration of IL-8 was analyzed by use of an ELISA kit (BD Biosciences) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Strains and growth conditions.

Staphylococcus aureus SA113 (wild type) and the Δlgt mutant (no expression of mature lipoproteins) were grown in tryptic soy broth (Sigma, Steinheim, Germany) at 37°C with aeration for 16 h. The optical density at 578 nm was 12 (Heλios α spectrophotometer; Thermo Scientific).

Isolation of polymeric peptidoglycan (PGNpol).

The isolation of ultrapure PGN, free of DNA, RNA, proteins, wall teichoic acids, lipoteichoic acids, and salts, was done according to the method of de Jonge et al. (32), with some modifications. These modifications included the usage of three different buffers (buffers A to C). The pellet of a 50-ml overnight culture was boiled in 10 ml buffer A (2.5% SDS in 0.1 M Tris-HCl, pH 6.8) for 20 min at 100°C. The SDS was removed by several washing steps with double-distilled water at 4,700 rpm at room temperature. The pellet was resuspended with 20 ml 0.1 M Tris-HCl, pH 6.8. Cells were disrupted by vortexing with glass beads (150 to 212 μm). The supernatant was subsequently incubated with buffer B for 1 h (10 μg/ml DNase and 50 μg/ml RNase in 0.1 M Tris-HCl, pH 6.8), with buffer C overnight (50 μg/ml trypsin in double-distilled water), and, finally, with hydrofluoric acid (HF) for 4 h. HF was washed out with double-distilled water, and the PGN was lyophilized overnight.

Lyophilized PGN (10 mg/ml) was digested with 500 U mutanolysin of Streptomyces globisporus ATCC 21553 (Sigma) in a 12.5 mM phosphate buffer (pH 5.5) at 37°C for 16 h. The sample was boiled for 3 min and centrifuged for 5 min at 10,000 rpm. The supernatant was reduced with sodium borohydride in 0.5 M borate buffer (pH 9) for 20 min at room temperature. The pH was subsequently adjusted to 2 with orthophosphoric acid. Samples were further processed or stored at −20°C.

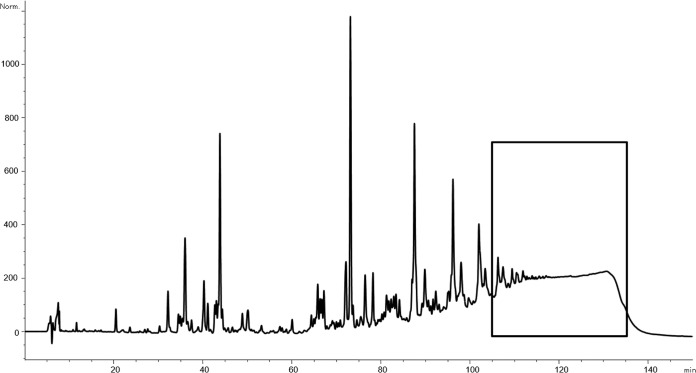

The separation and analysis of the peptidoglycan polymer were performed by high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC), based on the method of Glauner (33), using an Agilent 1200 analytical HPLC system. A 250- by 4.6-mm reversed-phase column (Prontosil 120-3-C18 AQ; Bischoff) guarded by a 20- by 4.6-mm precolumn was used. The samples were eluted at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min, using a linear gradient starting from 100% buffer A (100 mM NaH2PO4, 5% [vol/vol] methanol, pH 2.5) to 100% buffer B (100 mM NaH2PO4, 30% [vol/vol] methanol, pH 2.8) within 155 min. The column temperature was set to 52°C. The eluted muropeptides were detected by UV absorption at 205 nm. The corresponding polymer peak (rt = 105 to 135 min) (Fig. 1) was collected and desalted on the same column, using a water-acetonitrile gradient.

FIG 1.

Separation and analysis of polymeric PGN. Separation and analysis of the peptidoglycan polymer were performed using an Agilent 1200 analytical HPLC system. The corresponding polymer peak (rt = 105 to 135 min) was collected and desalted. Remaining LPS impurities were removed. Shown is the pattern for muramidase-digested PGN from an S. aureus SA113 wild-type overnight culture. The boxed sequence indicates the collected polymeric PGN fragments.

LPS contamination was checked using an Endosafe-PTS system (Charles River, Sulzfeld, Germany). Remaining LPS impurities were removed using an Endo Trap Red endotoxin removal kit (Hyglos). Very low LPS contents could be detected (<0.005 endotoxin unit [EU]/mg).

Statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA). Parameters were analyzed by a nonparametric one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) model for repeated measurements, with the Bonferroni adjustment (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; and ***, P < 0.001). P values of <0.05 were considered significant. Error bars represent standard errors of the means (SEM). If not otherwise mentioned, figures show means ± SEM of values from three experiments per group. Stimulated DCs from WT mice were compared to unstimulated DCs from WT mice, and stimulated DCs from NOD2−/− mice were compared to unstimulated DCs from NOD2−/− mice.

RESULTS

Purification of polymeric peptidoglycan (PGNpol) from S. aureus and its Δlgt mutant.

To address the importance of lipopeptide impurities within the PGN fractions in signaling, we isolated polymeric PGN from two S. aureus SA113 strains. On the one hand, we isolated PGN from wild-type SA113, containing residual mature lipoproteins within the polymeric PGN meshwork. On the other hand, we isolated PGN from SA113 Δlgt, which is considered lipoprotein free because of its inability to produce mature lipoproteins. A typical pattern for PGN from WT SA113 after muramidase digestion is shown in Fig. 1. The pattern for PGN from SA113 Δlgt was identical to the WT pattern and is therefore not shown.

Activation and maturation of DCs by PGNpol are due to residual lipoproteins.

In order to elucidate the role of S. aureus-derived polymeric PGN in the NOD2-mediated activation of BMDCs, these cells were stimulated with PGN isolated from either WT S. aureus SA113 (PGNpol) or SA113 Δlgt (PGNpolΔlgt). PGNpol is a ligand of NOD2, but while PGNpolΔlgt is lipoprotein free, the PGNpol preparation contains lipoproteins of S. aureus, which are known to be ligands of TLR2 (30).

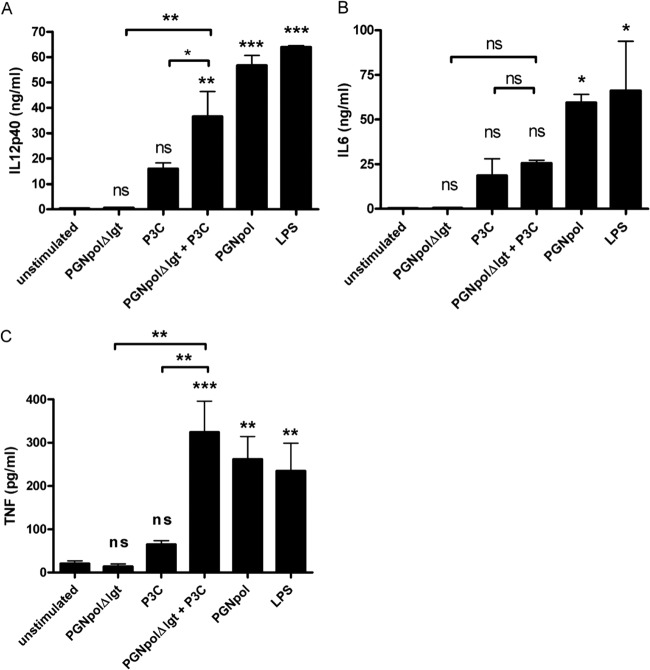

For control purposes, Pam3Cys (a synthetic triacylated lipopeptide), LPS, and MDP were used as specific ligands for TLR2, TLR4, and NOD2, respectively. Incubation of DCs with increasing concentrations of PGNpolΔlgt (up to 100 μg/ml) did not stimulate secretion of IL-6, as indicated in Fig. 2A. In contrast, PGNpol (10 μg/ml) strongly stimulated IL-6 secretion, to a degree that was comparable with that induced by LPS or Pam3Cys. Furthermore, incubation with PGNpolΔlgt (up to 100 μg/ml) did not induce secretion of IL-12p40 (Fig. 2B), while PGNpol (10 μg/ml) strongly stimulated IL-12p40 secretion.

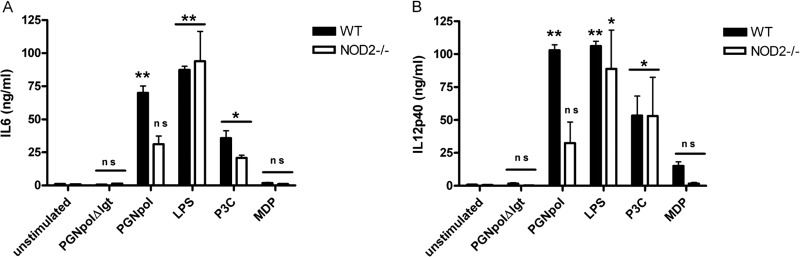

FIG 2.

Stimulation with PGNpol, but not PGNpolΔlgt, leads to significant secretion of IL-6 and IL-12p40 in DCs. Incubation of DCs with PGNpol, but not PGNpolΔlgt, stimulated IL-6 (A) and IL-12p40 (B) secretion, which was comparable to that induced by LPS or Pam3Cys. DCs were stimulated with PGNpolΔlgt at concentrations of up to 100 μg/ml. Stimulation with 10 μg/ml PGNpol led to high levels of secretion of IL-6 and IL-12p40. A comparison was made between unstimulated cells and each stimulant by using a nonparametric one-way ANOVA model for repeated measurements, with the Bonferroni adjustment. ns, not significant.

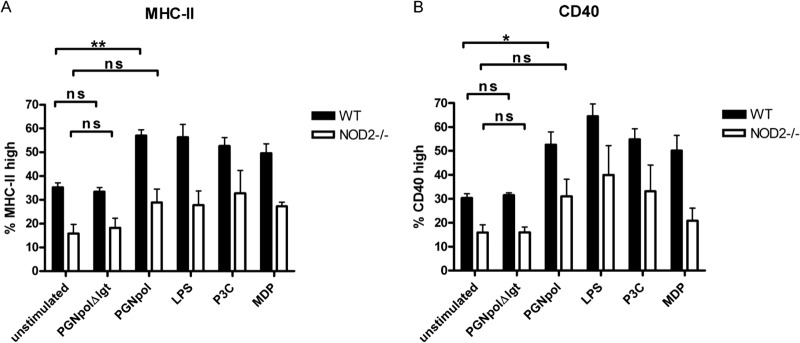

In order to find out whether PGNpol and PGNpolΔlgt lead to DC maturation, DCs were stimulated with PGNpolΔlgt or PGNpol and afterwards analyzed for MHC-II and CD40 surface expression by flow cytometry. DCs stimulated with PGNpol expressed high levels of MHC-II and CD40, resulting in highly activated and mature DCs. In contrast, expression of these surface molecules was nearly unaffected in DCs exposed to PGNpolΔlgt, suggesting a reduced ability of PGNpolΔlgt to activate and mature DCs (Fig. 3).

FIG 3.

Stimulation with PGNpol, but not PGNpolΔlgt, leads to increased MHC-II and CD40 expression in DCs. Immature BMDCs were activated with several NOD2 or TLR2 ligands. Maturation was quantified by FACS analysis to assess the levels of MHC-II (A) and CD40 (B). The quantification was based on isotype controls. Stimulation of DCs with PGNpol (10 μg/ml) led to strong MHC-II and CD40 signals. In contrast, stimulation of DCs with PGNpolΔlgt (10 μg/ml) did not lead to increased expression of MHC-II and CD40. A comparison was made between unstimulated cells and each stimulant by using a nonparametric one-way ANOVA model for repeated measurements, with the Bonferroni adjustment.

Stimulation with PGNpol leads to increased activation and maturation of DCs compared to the case with PGNpolΔlgt.

To further elucidate the effect of a bacterial NOD2 ligand and the potentially costimulatory effect of a TLR2 ligand, DCs from NOD2−/− mice were compared to DCs from WT mice.

First, secretion of IL-12p40 was tested after stimulation with PGNpolΔlgt and PGNpol. Consistent with the data shown in Fig. 2A, there was no detectable secretion of IL-12p40 after stimulation with PGNpolΔlgt in DCs from either WT mice or NOD2−/− mice.

In contrast, stimulation with PGNpol induced a significantly smaller IL-12p40 signal in DCs from NOD2−/− mice than in DCs from WT mice (Fig. 4). These data strongly suggest that a combined NOD2 and TLR2 signal is necessary to induce a strong secretion of IL-12p40 and that the smaller signal in the DCs from NOD2−/− mice was the result of the sole activation of TLR2. Similar results were obtained with IL-6 after stimulation of DCs from NOD2−/− mice with PGNpolΔlgt and PGNpol (data not shown).

FIG 4.

Stimulation with PGNpol in DCs is dependent on a NOD2 costimulus. Stimulation with PGNpol led to significantly increased secretion of IL-6 (A) and IL-12p40 (B) in DCs from WT mice compared to unstimulated controls. In contrast, DCs derived from NOD2−/− mice failed to show increased IL-6 and IL-12p40 secretion upon stimulation with PGNpol. Stimulated DCs from WT mice were compared to unstimulated DCs from WT mice, and stimulated DCs from NOD2−/− mice were compared to unstimulated DCs from NOD2−/− mice.

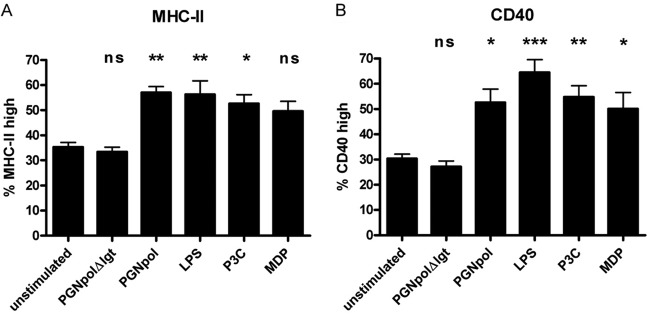

To further test the effect of combined TLR2 and NOD2 stimulation on DC activation and maturation, we analyzed the expression of the DC surface markers MHC-II and CD40 by flow cytometry. In NOD2−/− DCs, incubation with PGNpol led to a significantly smaller proportion of MHC-IIhigh cells than the case in stimulated WT DCs (Fig. 5A). Furthermore, there was an increased expression of CD40 in DCs after stimulation with PGNpol compared to PGNpolΔlgt (Fig. 5B). Taken together, our data strongly suggest that a combined stimulation of the TLR2 and NOD2 pathways by PGNpol is important for the activation and maturation of DCs.

FIG 5.

DC stimulation with PGNpol in WT mice leads to increased expression of MHC-II and CD40 compared to that in NOD2−/− mice. Stimulation of DCs from NOD2−/− mice with PGNpol (10 μg/ml) did not lead to significantly more expression of MHC-II (A) or CD40 (B), indicating that the costimulatory effect of NOD2 and TLR2 is necessary for effective maturation of DCs. Stimulated DCs from WT mice were compared to unstimulated DCs from WT mice, and unstimulated DCs from NOD2−/− mice were compared to stimulated DCs from NOD−/− mice. In addition, a comparison between DCs from WT and NOD2−/− mice was made by using a nonparametric one-way ANOVA model for repeated measurements, with the Bonferroni adjustment.

Combined stimulation of DCs with PGNpolΔlgt and Pam3Cys reveals synergistic effects on TNF-α secretion pattern.

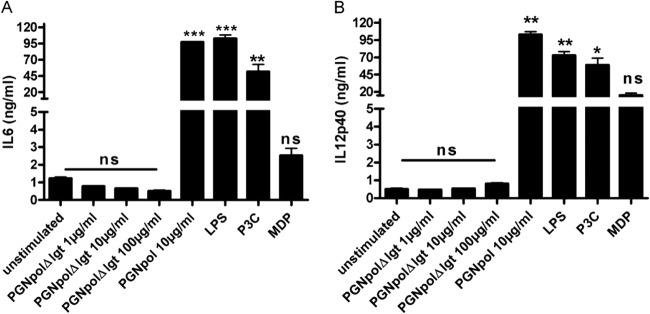

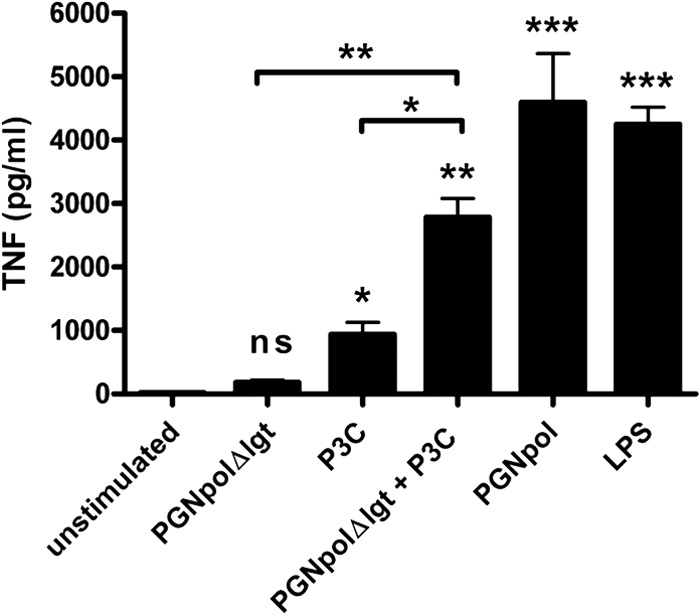

TNF-α is a key cytokine in IBD and is well known for its role in mediating innate immune responses (34). To confirm our hypothesis that combined stimulation with TLR2 and NOD2 ligands acts synergistically on DC cytokine secretion, we costimulated DCs with the NOD2 ligand PGNpolΔlgt and the TLR2 ligand Pam3Cys and determined the secretion of TNF-α. In line with our hypothesis, the costimulation induced a significantly enhanced expression of TNF-α in DCs compared to the case in PGNpolΔlgt- or P3C-monostimulated DCs (Fig. 6).

FIG 6.

Combined stimulation of DCs with NOD2 and TLR2 ligands leads to stronger secretion of IL-12p40 and TNF than stimulation with each of the stimuli alone. DCs were stimulated with PGNpolΔlgt (10 μg/ml), Pam3Cys (1 μg/ml), and LPS (1 μg/ml). After stimulation with both PGNpolΔlgt and Pam3Cys, there were significantly higher signals for IL-12p40 (A) and TNF (C) than the case for stimulation with the single components alone. (B) There was not a significantly higher signal of IL-6 than that for stimulation with the single components. Unstimulated DCs from WT mice were compared to stimulated DCs from WT mice by using a nonparametric one-way ANOVA model for repeated measurements, with the Bonferroni adjustment.

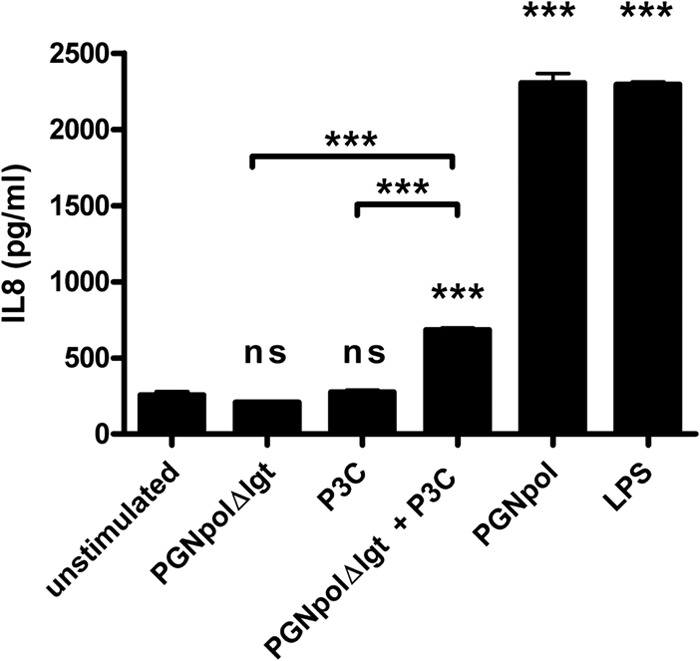

To further confirm these findings, the experiments were extended to additional immune cells, i.e., a murine macrophage cell line (J774 cells) (Fig. 7) and a human monocyte cell line (MM6 cells) (Fig. 8). In both cell lines, the synergistic costimulation with PGNpolΔlgt and P3C resulted in an increased expression of proinflammatory cytokines, indicating that the observed effect is not restricted to mouse DCs but seems to be relevant for the activation of different types of innate immune cells.

FIG 7.

Combined stimulation of J774 cells with NOD2 and TLR2 ligands leads to significant TNF-α secretion. J774 cells were stimulated with Pam3Cys (1 ng/ml), PGNpolΔlgt (10 μg/ml), PGNpol (10 μg/ml), and LPS (1 μg/ml) for 48 h. After stimulation with both PGNpolΔlgt and Pam3Cys, there was a significant increase of TNF-α, which seemed to be higher than stimulation with the single components. Unstimulated DCs from WT mice were compared to stimulated DCs from WT mice by using a nonparametric one-way ANOVA model for repeated measurements, with the Bonferroni adjustment.

FIG 8.

Combined but not single stimulation of MM6 cells with NOD2 and TLR2 ligands leads to a significant increase of IL-8. MM6 cells were stimulated with Pam3Cys (10 ng/ml), PGNpolΔlgt (10 μg/ml), PGNpol (10 μg/ml), and LPS (1 μg/ml) for 48 h. After stimulation with both PGNpolΔlgt and Pam3Cys, there was a significant increase of IL-8, whereas stimulation with single components did not lead to IL-8 secretion. Stimulated DCs from WT mice were compared to unstimulated DCs from WT mice. Unstimulated DCs from WT mice were compared to stimulated DCs from WT mice by using a nonparametric one-way ANOVA model for repeated measurements, with the Bonferroni adjustment.

DISCUSSION

NOD2 mutations play an important role in Crohn's disease (1, 2). However, how exactly these mutations contribute to this specific disease still remains uncovered. NOD2, as an important intracellular receptor of the innate immune system, senses bacterial cell wall products, such as MDP, and activates NF-κB (35). While MDP was the first NOD2 ligand described (36, 37), it later became clear that polymeric (16, 38) as well as monomeric (14) PGN also activates NOD2. DCs are the most potent APCs in the intestinal mucosa and have important functions in the mucosa-associated immune system (39). Because of their important role in activating and also regulating the immune system, they also seem to play an important role in Crohn's disease (11). Therefore, we studied the role of NOD2-mediated activation of DCs via natural S. aureus-derived PGN. In the present study, we focused on the role of polymeric PGN, which is an important part of the bacterial cell wall. Defined isogenic S. aureus mutant strains were used to elucidate the effect of NOD2 ligand (PGNpolΔlgt) monostimulation or the synergistic effect of NOD2 and TLR2 ligand (PGNpol) costimulation. While monostimulation with a natural NOD2 ligand (PGNpolΔlgt) did not lead to activation and maturation of DCs, costimulation with a NOD2 and TLR2 ligand (PGNpol) led to strong activation and increased cytokine secretion (IL-6 and IL-12p40) of DCs in vivo. This effect was seen not only in isolated DCs but also in J774 cells (macrophages) and MM6 cells (monocytes). In addition to already published work by Müller-Anstett et al. (26), our data indicate that singular NOD2 activation seems to play a minor role in activating immune cells. However, synergistic costimulation of the NOD2 and TLR2 pathways results in potent activation of DCs, macrophages, and monocytes.

In patients with Crohn's disease, an exaggerated Th1-mediated immune response may contribute to mucosal inflammation (40). In vivo, MDP itself is not able to induce a Th1 cytokine profile but rather invokes a Th2 immune response (41). Additionally, in support of our results, it has been demonstrated that combined stimulation with MDP plus a TLR2 or TLR4 ligand leads to a synergistic release of IL-6 and IL-12p40 in BMDCs, which is abolished in NOD2−/− DCs (41). While stimulation of the innate immune system with a sole NOD2 ligand, in our case S. aureus-derived polymeric PGNpolΔlgt, does not lead to an immune response, such a response is markedly enhanced after dual stimulation via the NOD2 and TLR2 pathways. The complex interplay between NOD2 and TLR2 signaling might have an influence on intestinal homeostasis.

However, how can these results be translated into the clinical entity of Crohn's disease? Activation of NOD2 by MDP protects mice from experimental colitis (42), thus promoting intestinal homeostasis. Additionally, PGN from specific lactobacilli features anti-inflammatory effects and thus seems to be crucial for the probiotic action of these specific strains (43). These studies further support the hypothesis that stimulation of NOD2 alone—as opposed to costimulation of NOD2 and TLR2—can possibly lead to downregulation of inflammatory pathways. A “loss of function” in the NOD2 gene might therefore be an important part of the pathogenesis of Crohn's disease.

In summary, we showed that in DCs, synergistic costimulation of the NOD2 and TLR2 signaling cascades leads to an increased activation and maturation of DCs, and also to increased cytokine secretion, compared to the case with monostimulation. These results might be important for a better understanding of the complex interplay between these receptors in maintaining homeostasis in the intestinal immune system.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by Glykobiologie/Glykomik contract research of the Baden-Württemberg Stiftung, by DFG grants SFB 685 and SPP1656, and by the BMBF.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 25 August 2014

REFERENCES

- 1.Hampe J, Cuthbert A, Croucher PJ, Mirza MM, Mascheretti S, Fisher S, Frenzel H, King K, Hasselmeyer A, MacPherson AJ, Bridger S, van Deventer S, Forbes A, Nikolaus S, Lennard-Jones JE, Foelsch UR, Krawczak M, Lewis C, Schreiber S, Mathew CG. 2001. Association between insertion mutation in NOD2 gene and Crohn's disease in German and British populations. Lancet 357:1925–1928. 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)05063-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hugot JP, Chamaillard M, Zouali H, Lesage S, Cezard JP, Belaiche J, Almer S, Tysk C, O'Morain CA, Gassull M, Binder V, Finkel Y, Cortot A, Modigliani R, Laurent-Puig P, Gower-Rousseau C, Macry J, Colombel JF, Sahbatou M, Thomas G. 2001. Association of NOD2 leucine-rich repeat variants with susceptibility to Crohn's disease. Nature 411:599–603. 10.1038/35079107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ogura Y, Bonen DK, Inohara N, Nicolae DL, Chen FF, Ramos R, Britton H, Moran T, Karaliuskas R, Duerr RH, Achkar JP, Brant SR, Bayless TM, Kirschner BS, Hanauer SB, Nunez G, Cho JH. 2001. A frameshift mutation in NOD2 associated with susceptibility to Crohn's disease. Nature 411:603–606. 10.1038/35079114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Strober W, Murray PJ, Kitani A, Watanabe T. 2006. Signalling pathways and molecular interactions of NOD1 and NOD2. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 6:9–20. 10.1038/nri1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ng SC, Kamm MA, Stagg AJ, Knight SC. 2010. Intestinal dendritic cells: their role in bacterial recognition, lymphocyte homing, and intestinal inflammation. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 16:1787–1807. 10.1002/ibd.21247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Niess JH, Brand S, Gu X, Landsman L, Jung S, McCormick BA, Vyas JM, Boes M, Ploegh HL, Fox JG, Littman DR, Reinecker HC. 2005. CX3CR1-mediated dendritic cell access to the intestinal lumen and bacterial clearance. Science 307:254–258. 10.1126/science.1102901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coombes JL, Powrie F. 2008. Dendritic cells in intestinal immune regulation. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 8:435–446. 10.1038/nri2335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Strober W. 2009. The multifaceted influence of the mucosal microflora on mucosal dendritic cell responses. Immunity 31:377–388. 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iwasaki A, Medzhitov R. 2004. Toll-like receptor control of the adaptive immune responses. Nat. Immunol. 5:987–995. 10.1038/ni1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baumgart DC, Sandborn WJ. 2012. Crohn's disease. Lancet 380:1590–1605. 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60026-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Niess JH. 2008. Role of mucosal dendritic cells in inflammatory bowel disease. World J. Gastroenterol. 14:5138–5148. 10.3748/wjg.14.5138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hart AL, Al-Hassi HO, Rigby RJ, Bell SJ, Emmanuel AV, Knight SC, Kamm MA, Stagg AJ. 2005. Characteristics of intestinal dendritic cells in inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology 129:50–65. 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iliev ID, Spadoni I, Mileti E, Matteoli G, Sonzogni A, Sampietro GM, Foschi D, Caprioli F, Viale G, Rescigno M. 2009. Human intestinal epithelial cells promote the differentiation of tolerogenic dendritic cells. Gut 58:1481–1489. 10.1136/gut.2008.175166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Volz T, Nega M, Buschmann J, Kaesler S, Guenova E, Peschel A, Rocken M, Götz F, Biedermann T. 2010. Natural Staphylococcus aureus-derived peptidoglycan fragments activate NOD2 and act as potent costimulators of the innate immune system exclusively in the presence of TLR signals. FASEB J. 24:4089–4102. 10.1096/fj.09-151001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hashimoto M, Tawaratsumida K, Kariya H, Kiyohara A, Suda Y, Krikae F, Kirikae T, Götz F. 2006. Not lipoteichoic acid but lipoproteins appear to be the dominant immunobiologically active compounds in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Immunol. 177:3162–3169. 10.4049/jimmunol.177.5.3162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iyer JK, Coggeshall KM. 2011. Cutting edge: primary innate immune cells respond efficiently to polymeric peptidoglycan, but not to peptidoglycan monomers. J. Immunol. 186:3841–3845. 10.4049/jimmunol.1004058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bera A, Herbert S, Jakob A, Vollmer W, Götz F. 2005. Why are pathogenic staphylococci so lysozyme resistant? The peptidoglycan O-acetyltransferase OatA is the major determinant for lysozyme resistance of Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Microbiol. 55:778–787. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04446.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bera A, Biswas R, Herbert S, Götz F. 2006. The presence of peptidoglycan O-acetyltransferase in various staphylococcal species correlates with lysozyme resistance and pathogenicity. Infect. Immun. 74:4598–4604. 10.1128/IAI.00301-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Herbert S, Bera A, Nerz C, Kraus D, Peschel A, Goerke C, Meehl M, Cheung A, Götz F. 2007. Molecular basis of resistance to muramidase and cationic antimicrobial peptide activity of lysozyme in staphylococci. PLoS Pathog. 3:e102. 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shimada T, Park BG, Wolf AJ, Brikos C, Goodridge HS, Becker CA, Reyes CN, Miao EA, Aderem A, Götz F, Liu GY, Underhill DM. 2010. Staphylococcus aureus evades lysozyme-based peptidoglycan digestion that links phagocytosis, inflammasome activation, and IL-1beta secretion. Cell Host Microbe 7:38–49. 10.1016/j.chom.2009.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Netea MG, Kullberg BJ, de Jong DJ, Franke B, Sprong T, Naber TH, Drenth JP, Van der Meer JW. 2004. NOD2 mediates anti-inflammatory signals induced by TLR2 ligands: implications for Crohn's disease. Eur. J. Immunol. 34:2052–2059. 10.1002/eji.200425229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Watanabe T, Kitani A, Murray PJ, Strober W. 2004. NOD2 is a negative regulator of Toll-like receptor 2-mediated T helper type 1 responses. Nat. Immunol. 5:800–808. 10.1038/ni1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dahiya Y, Pandey RK, Sodhi A. 2011. Nod2 downregulates TLR2/1 mediated IL1beta gene expression in mouse peritoneal macrophages. PLoS One 6:e27828. 10.1371/journal.pone.0027828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kobayashi KS, Chamaillard M, Ogura Y, Henegariu O, Inohara N, Nunez G, Flavell RA. 2005. Nod2-dependent regulation of innate and adaptive immunity in the intestinal tract. Science 307:731–734. 10.1126/science.1104911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Travassos LH, Girardin SE, Philpott DJ, Blanot D, Nahori MA, Werts C, Boneca IG. 2004. Toll-like receptor 2-dependent bacterial sensing does not occur via peptidoglycan recognition. EMBO Rep. 5:1000–1006. 10.1038/sj.embor.7400248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Müller-Anstett MA, Muller P, Albrecht T, Nega M, Wagener J, Gao Q, Kaesler S, Schaller M, Biedermann T, Götz F. 2010. Staphylococcal peptidoglycan co-localizes with Nod2 and TLR2 and activates innate immune response via both receptors in primary murine keratinocytes. PLoS One 5:e13153. 10.1371/journal.pone.0013153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hashimoto M, Tawaratsumida K, Kariya H, Aoyama K, Tamura T, Suda Y. 2006. Lipoprotein is a predominant Toll-like receptor 2 ligand in Staphylococcus aureus cell wall components. Int. Immunol. 18:355–362. 10.1093/intimm/dxh374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schmaler M, Jann NJ, Ferracin F, Landolt LZ, Biswas L, Götz F, Landmann R. 2009. Lipoproteins in Staphylococcus aureus mediate inflammation by TLR2 and iron-dependent growth in vivo. J. Immunol. 182:7110–7118. 10.4049/jimmunol.0804292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zahringer U, Lindner B, Inamura S, Heine H, Alexander C. 2008. TLR2—promiscuous or specific? A critical re-evaluation of a receptor expressing apparent broad specificity. Immunobiology 213:205–224. 10.1016/j.imbio.2008.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stoll H, Dengjel J, Nerz C, Götz F. 2005. Staphylococcus aureus deficient in lipidation of prelipoproteins is attenuated in growth and immune activation. Infect. Immun. 73:2411–2423. 10.1128/IAI.73.4.2411-2423.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lutz MB, Kukutsch N, Ogilvie AL, Rossner S, Koch F, Romani N, Schuler G. 1999. An advanced culture method for generating large quantities of highly pure dendritic cells from mouse bone marrow. J. Immunol. Methods 223:77–92. 10.1016/S0022-1759(98)00204-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.de Jonge BL, Chang YS, Gage D, Tomasz A. 1992. Peptidoglycan composition of a highly methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strain. The role of penicillin binding protein 2A. J. Biol. Chem. 267:11248–11254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Glauner B. 1988. Separation and quantification of muropeptides with high-performance liquid chromatography. Anal. Biochem. 172:451–464. 10.1016/0003-2697(88)90468-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mizgerd JP, Spieker MR, Doerschuk CM. 2001. Early response cytokines and innate immunity: essential roles for TNF receptor 1 and type I IL-1 receptor during Escherichia coli pneumonia in mice. J. Immunol. 166:4042–4048. 10.4049/jimmunol.166.6.4042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Strober W, Kitani A, Fuss I, Asano N, Watanabe T. 2008. The molecular basis of NOD2 susceptibility mutations in Crohn's disease. Mucosal Immunol. 1(Suppl 1):S5–S9. 10.1038/mi.2008.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Girardin SE, Boneca IG, Viala J, Chamaillard M, Labigne A, Thomas G, Philpott DJ, Sansonetti PJ. 2003. Nod2 is a general sensor of peptidoglycan through muramyl dipeptide (MDP) detection. J. Biol. Chem. 278:8869–8872. 10.1074/jbc.C200651200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Inohara N, Ogura Y, Fontalba A, Gutierrez O, Pons F, Crespo J, Fukase K, Inamura S, Kusumoto S, Hashimoto M, Foster SJ, Moran AP, Fernandez-Luna JL, Nunez G. 2003. Host recognition of bacterial muramyl dipeptide mediated through NOD2. Implications for Crohn's disease. J. Biol. Chem. 278:5509–5512. 10.1074/jbc.C200673200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Natsuka M, Uehara A, Yang S, Echigo S, Takada H. 2008. A polymer-type water-soluble peptidoglycan exhibited both Toll-like receptor 2- and NOD2-agonistic activities, resulting in synergistic activation of human monocytic cells. Innate Immun. 14:298–308. 10.1177/1753425908096518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cella M, Sallusto F, Lanzavecchia A. 1997. Origin, maturation and antigen presenting function of dendritic cells. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 9:10–16. 10.1016/S0952-7915(97)80153-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Peluso I, Pallone F, Monteleone G. 2006. Interleukin-12 and Th1 immune response in Crohn's disease: pathogenetic relevance and therapeutic implication. World J. Gastroenterol. 12:5606–5610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Magalhaes JG, Fritz JH, Le Bourhis L, Sellge G, Travassos LH, Selvanantham T, Girardin SE, Gommerman JL, Philpott DJ. 2008. Nod2-dependent Th2 polarization of antigen-specific immunity. J. Immunol. 181:7925–7935. 10.4049/jimmunol.181.11.7925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Watanabe T, Asano N, Murray PJ, Ozato K, Tailor P, Fuss IJ, Kitani A, Strober W. 2008. Muramyl dipeptide activation of nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain 2 protects mice from experimental colitis. J. Clin. Invest. 118:545–559. 10.1172/JCI33145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Macho Fernandez E, Valenti V, Rockel C, Hermann C, Pot B, Boneca IG, Grangette C. 2011. Anti-inflammatory capacity of selected lactobacilli in experimental colitis is driven by NOD2-mediated recognition of a specific peptidoglycan-derived muropeptide. Gut 60:1050–1059. 10.1136/gut.2010.232918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]