Abstract

To identify possible explanations for the recent global emergence of Escherichia coli sequence type (ST) 131 (ST131), we analyzed temporal trends within ST131 O25 for antimicrobial resistance, virulence genes, biofilm formation, and the H30 and H30-Rx subclones. For this, we surveyed the WHO E. coli and Klebsiella Centre's E. coli collection (1957 to 2011) for ST131 isolates, characterized them extensively, and assessed them for temporal trends. Overall, antimicrobial resistance increased temporally in prevalence and extent, due mainly to the recent appearance of the H30 (1997) and H30-Rx (2005) ST131 subclones. In contrast, neither the total virulence gene content nor the prevalence of biofilm production increased temporally, although non-H30 isolates increasingly qualified as extraintestinal pathogenic E. coli (ExPEC). Whereas virotype D occurred from 1968 forward, virotypes A and C occurred only after 2000 and 2002, respectively, in association with the H30 and H30-Rx subclones, which were characterized by multidrug resistance (including extended-spectrum-beta-lactamase [ESBL] production: H30-Rx) and absence of biofilm production. Capsular antigen K100 occurred exclusively among H30-Rx isolates (55% prevalence). Pulsotypes corresponded broadly with subclones and virotypes. Thus, ST131 should be regarded not as a unitary entity but as a group of distinctive subclones, with its increasing antimicrobial resistance having a strong clonal basis, i.e., the emergence of the H30 and H30-Rx ST131 subclones, rather than representing acquisition of resistance by diverse ST131 strains. Distinctive characteristics of the H30-Rx subclone—including specific virulence genes (iutA, afa and dra, kpsII), the K100 capsule, multidrug resistance, and ESBL production—possibly contributed to epidemiologic success, and some (e.g., K100) might serve as vaccine targets.

INTRODUCTION

Sequence type (ST) 131 (ST131) of Escherichia coli, most members of which exhibit serotype O25:H4, is a recently emerged, globally disseminated cause of multidrug-resistant (MDR) extraintestinal infections (1). ST131 is closely associated with fluoroquinolone resistance and the CTX-M-15 extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) (2, 3). ST131 has two prominent multidrug-resistance-associated subclones, defined on allele 30 of fimH, i.e., H30, which reportedly accounts for almost all fluoroquinolone resistance within ST131, and H30-Rx, a subset within H30 that reportedly accounts for almost all ST131-associated CTX-M-15 production (3–7).

Despite the large number of reports on ST131, no clear explanation has emerged for the clone's dramatic expansion and global epidemic spread after the year 2000. We recently documented diverse capsular antigens among ESBL-producing ST131 isolates (8). However, little is known regarding temporal trends within this successful extraintestinal pathogenic E. coli (ExPEC) clonal group and its principal subclones for virulence gene content (including the recently described virotypes [9]), antimicrobial resistance phenotypes, biofilm production, and K antigens, particularly with regard to the trends that were prevalent before 1990 (5).

We hypothesized that the overall clonal group has become both more extensively antibiotic resistant and more virulent over time, as reflected in virulence gene content (10) and biofilm production capability (11). To test these hypotheses, we used a large archival E. coli isolate collection to define (i) temporal trends of emergence of the principal clonal subsets within ST131-O25:H4, i.e., non-H30, H30 (non-Rx), and H30-Rx; (ii) the characteristics of these clonal subsets with respect to antimicrobial resistance, virulence-associated genes and phenotypes, biofilm production, and capsular antigens; and (iii) temporal trends for these characteristics, both overall and within each clonal subset. Additionally, since we recently documented the presence of enteroaggregative Escherichia coli (EAEC; a diarrheagenic pathotype) among various non-ST131 extraintestinal E. coli clinical isolates (8, 12, 13), we assessed whether any historic or recent ST131 clonal group members represent EAEC.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Clinical and epidemiological information.

The WHO Collaborating Centre for Reference and Research on Escherichia and Klebsiella (www.ssi.dk) functions as an international reference center for O:K:H serotyping and participates in various highly selected national and international projects. It holds more than 75,000 E. coli isolates, as received from more than 85 different countries since 1951, from both humans (≥33,000) and animals (≥9,500).

To identify all available E. coli O25:H4 and O25:H- ST131 isolates held by the Centre, the Centre's E. coli database (1951 to 2011) was searched for serotypes O25:H4 and O25:H- and for serogroup O25 (H antigen not tested for). In total, 367 nonduplicate isolates meeting these criteria were recovered and were retested for O25 antigen expression, which confirmed 291 serogroup O25 isolates (with or without the H4 antigen). A two-stage, PCR-based screen for ST131 status involving detection of the ST131-associated pabB allele and the O25b rfb (lipopolysaccharide-encoding) variant (14), plus ST131-specific polymorphisms in gyrB and mdh (15), yielded 119 confirmed O25 ST131 E. coli isolates from 1968 through 2011. Additionally, nine previously reported O-rough:H4 ST131 isolates (8) were included, giving a total of 128 archival ST131 isolates. Of these, 55 isolates were previously published but not with respect to clonal subset (8) or clonal subset plus virulence factors (16). The 128 isolates, all of which were sent to the WHO Centre for serotyping, originated from 16 countries: Denmark (80 isolates), Norway (12 isolates), Peru (8 isolates), Sweden (7 isolates), France (4 isolates), the United States (3 isolates), Germany (3 isolates), the United Kingdom (2 isolates), South Africa (2 isolates), and Belgium, Finland, Taiwan, Canada, Slovakia, Argentina, and Guatemala (1 isolate each). The Centre's database contained information regarding the source of isolation for 91 (71%) of the 128 ST131 E. coli isolates and information regarding clinical condition for 27 (21%) of the isolates.

Phenotypic characteristics.

Serotyping was done according to Ørskov and Ørskov (17). K antigens were determined by countercurrent immunoelectrophoresis involving K-specific antisera, except for the K1 and K5 antigens, which were detected using K1- and K5-specific phages. Verocytotoxin was detected by the Verocell assay (18). Vero cytotoxin-producing E. coli or Shiga toxin-producing E. coli (VTEC or STEC) is a diarrheagenic pathotype associated with diarrhea and hemolytic-uremic syndrome (HUS). Biofilm production was assessed by detection of crystal violet retention after overnight broth growth in polystyrene microtiter plates (8). Isolates with higher biofilm-forming capacity than the E. coli K-12 MG1655 strain were considered biofilm producers.

ESBL variants.

The gene encoding CTX-M-15 was detected by using a blaCTX-M-15-specific PCR assay (19).

Virulence genotyping.

Isolates were tested for multiple extraintestinal and diarrheagenic virulence genes by two different PCR-based methods (19). First, 50 virulence markers of ExPEC were detected using established multiplex PCR assays (20–23). Testing was done in duplicate using independently prepared boiled lysates of each isolate, together with appropriate positive and negative controls. Isolates were regarded as ExPEC if positive for ≥2 of papA and/or papC (P fimbriae; counted as one), sfa and foc (S and F1C fimbriae), afa and dra (Dr-binding adhesins), kpsMII (group 2 capsule), and iutA (aerobactin system) (24). The combination “kpsMII positive, kii negative” was interpreted as indicative of the presence of the K2 or K100 capsule (8, 25). Virotypes and subtypes thereof were defined by specific gene combinations (9). The virulence score was the number of extraintestinal virulence genes detected, adjusted for multiple detection of the pap, sfa and foc, and kps operons. Second, a multiplex PCR was used to screen for the diarrheagenic enteroaggregative Escherichia coli (EAEC)-associated putative virulence genes aggR, aatA, and aaiC (26). Strains exhibiting ≥1 of these genes were considered EAEC (26).

H30 and H30-Rx subclone detection.

According to PCR-based screening, ST131 isolates were classified into the H30 subclone if they contained H30-specific polymorphisms in fimH (10) and were further classified into the H30-Rx subclone if they also contained an H30-Rx-specific polymorphism in the allantoin protein-encoding gene (3).

PFGE analysis.

XbaI pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) analysis was done according to the PulseNet protocol (27). Pulsotypes were defined at the ≥94% profile similarity level in comparison with index isolates, corresponding to an approximately ≤3-band difference, suggesting genetic relatedness (28). Study isolate profiles were compared with the entries in a large private PFGE profile library (29).

Susceptibility testing.

ESBL production was screened for by cefpodoxime resistance analysis and the double-disk synergy test, with disks containing cefotaxime and ceftazidime with or without clavulanate (30). MICs for 18 antibiotics (amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, ampicillin, apramycin, cefotaxime, ceftiofur, chloramphenicol, ciprofloxacin, colistin, florfenicol, gentamicin, meropenem, nalidixic acid, neomycin, spectinomycin, streptomycin, sulfamethoxazole, tetracycline, and trimethoprim) were determined by broth microdilution using a Sensititre system (Trek Diagnostic Systems Ltd., United Kingdom) according to the manufacturer's instructions and Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute guidelines. Results were interpreted according to the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) (http://www.eucast.org) epidemiologic breakpoints, except for amoxicillin-clavulanate and sulfamethoxazole (which lack EUCAST epidemiologic breakpoints), for which Statens Serum Institut resistance breakpoints (>16 mg/liter and >256 mg/liter, respectively) were used. E. coli ATCC 25922 was used as a control. Isolates resistant to ≥3 antimicrobial classes, counting penicillins and cephalosporins separately, were classified as multidrug resistant (MDR) (5). The resistance score was the number of individual drugs to which an isolate was resistant (19).

Statistical methods.

Comparisons of proportions were tested using Fisher's (2-tailed) exact test. Comparisons involving continuous variables were tested using the Mann-Whitney U test. Changes over time in specific traits were assessed by generalized linear regression models, using year as the predictor variable. Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05.

RESULTS

ST131 prevalence and distribution by year and source.

According to PCR-based screening, ST131 accounted for 119 (32%) of the WHO Centre's 367 recoverable nonduplicate E. coli isolates of serotype O25:H4 or O25:H- (1968 to 2011). These 119 isolates, plus 9 previously identified O-rough:H4 ST131 isolates, gave 128 total ST131 isolates of serotype O25 (or O-rough):H4 or O25:H- (or H unknown) for analysis here.

The numbers and percentages of ST131 isolates compared to the total number of isolates received in the WHO Centre per decade were as follows: 5/6,169 (0.08%) (1968 to 1970), 5/17,316 (0.03%) (1971 to 1980), 10/14,026 (0.07%) (1981 to 1990), 27/13,737 (0.20%) (1991 to 2000), 79/10,221 (0.77%) (2001 to 2010), and 2/2,272 (0.09%) (2011). The source was known for 91 (71%) of these isolates and included the following in sequential order by number of isolates (percentage of 128): urine, 53 (41%); feces, 18 (14%); blood, 6 (5%); poultry or food, 7 (5%); respiratory tract, 5 (4%); peritoneum, 1 (1%). The 3 earliest ST131 isolates overall were all 1968 unknown-source isolates from England and Peru, whereas the earliest ST131 isolate of known source was a 1981 human fecal isolate from Guatemala.

ST131 subclones.

Subclonal typing of the 128 ST131 isolates showed that 62 (48%) were non-H30, 17 (13%) were H30 (non-Rx), and 49 (38%) were H30-Rx, for a total of 66 H30 subclone isolates. The temporal distribution of ST131 and its 3 clonal subsets was as follows, by median year of submission (range): ST131 overall, median, 2006 (1968 to 2011); non-H30, median, 1998 (range, 1968 to 2005); H30 (non-Rx), median, 2010 (range, 1997 to 2011); and H30-Rx, median, 2010 (range, 2005 to 2010).

Capsular antigens.

In total, 13 different capsular antigens were identified (Table 1), most commonly K100 (n = 27, 21%), K2 (n = 22, 17%), and K16 (n = 14, 11%). Whereas K2 and K16 were present since the earliest years of ST131 (K2 from 1968, K16 from 1972), K100 appeared first in 2005.

TABLE 1.

Prevalence of capsular (K) antigens according to clonal subset among 128 archival ST131 Escherichia coli isolates (1968 to 2011)

| K antigen(s) | No. (column %) of isolates harboring K antigens |

P valuea |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n = 128) | Non-H30 (n = 62) | H30 (non-Rx) (n = 17) | H30-Rx (n = 49) | Non-H30 vs H30 (non-Rx) | Non-H30 vs H30-Rx | H30 (non-Rx) vs H30-Rx | |

| K2 | 22 (17) | 14 (23) | 0 (0) | 8 (16) | 0.03 | ||

| K4 | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |||

| K5 | 10 (8) | 1 (2) | 6 (35) | 3 (6) | <0.001 | ||

| K12 | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |||

| K13 | 2 (2) | 2 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |||

| K14 | 2 (2) | 2 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |||

| K16 | 14 (11) | 14 (23) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.03 | <0.001 | |

| K20 | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | 1 (6) | 1 (2) | |||

| K20, K23 | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | |||

| K22 | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | |||

| K97 | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |||

| K98 | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | |||

| K100 | 27 (21) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 27 (55) | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| K+b | 28 (22) | 20 (32) | 5 (29) | 3 (6) | <0.001 | 0.022 | |

| K−c | 15 (12) | 6 (10) | 5 (29) | 4 (8) | 0.042 | ||

P values, by Fisher's (2-tailed) exact test, are shown where P < 0.05.

Capsular antigen of unknown type present.

No capsular antigen present.

K antigens tracked closely with clonal subset (Table 1). Specifically, the 66 H30 isolates (i.e., H30 [non-Rx] and H30-Rx combined) exhibited higher prevalences of K100 (41% versus 0%; P < 0.001) and K5 (2% versus 14%; P = 0.02) than the 62 non-H30 ST131 isolates but a lower prevalence of K16 (23% versus 0%; P < 0.001). Likewise, among the 66 H30 isolates, K100 occurred exclusively among H30-Rx isolates (55% H30-Rx versus 0% H30 [non-Rx]; P < 0.001).

Other phenotypes.

No isolate produced verotoxin. Nineteen (15%) isolates produced biofilm, which was strongly associated with non-H30 isolates (17/62 [27%] versus 2/66 [3%]; P < 0.001).

Antimicrobial susceptibility and ESBL production.

Of the total of 128 ST131 isolates, 112 (88%) were resistant to ≥1 antimicrobial agent, 96 (75%) were MDR, and 60 (47%) were ESBL producers (Table 2). Resistance scores varied significantly in relation to clonal subset, being much lower among non-H30 isolates (median, 4; range, 0 to 10) than among H30 (non-Rx) isolates (median, 9; range, 2 to 12) or H30-Rx isolates (median, 9; range, 3 to 13) (P < 0.001 for both comparisons), whereas the latter groups did not differ from one another (P = 0.23).

TABLE 2.

Prevalence of antimicrobial resistance characteristics according to clonal subset among 128 archival Escherichia coli ST131 isolates (1968 to 2011)

| Antimicrobial agent(s) or isolate categoryb | No. (column %) of isolates showing antimicrobial resistance |

P valuea |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n = 128) | non-H30 (n = 62) | H30 (non-Rx) (n = 17) | H30 Rx (n = 49) | Non-H30 vs H30 (non-Rx) | Non-H30 vs H30-Rx | H30 (non-Rx) vs H30-Rx | |

| Amoxicillin-clavulanate | 62 (48) | 24 (39) | 10 (59) | 28 (57) | |||

| Ampicillin | 102 (80) | 39 (63) | 16 (94) | 47 (96) | 0.016 | <0.001 | |

| Cefotaxime | 63 (49) | 7 (11) | 10 (59) | 46 (94) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.002 |

| Ceftiofur | 59 (46) | 6 (10) | 9 (53) | 44 (90) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Chloramphenicol | 24 (19) | 19 (31) | 0 (0) | 5 (10) | 0.008 | 0.011 | |

| Ciprofloxacin | 71 (56) | 6 (10) | 16 (94) | 49 (100) | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Gentamicin | 36 (28) | 15 (24) | 8 (47) | 13 (27) | |||

| Nalidixic acid | 71 (56) | 7 (11) | 15 (88) | 49 (100) | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Neomycin | 5 (4) | 5 (8) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |||

| Spectinomycin | 55 (43) | 23 (37) | 5 (29) | 27 (55) | |||

| Streptomycin | 61 (48) | 28 (45) | 12 (71) | 21 (43) | |||

| Sulfamethoxazole | 74 (58) | 19 (31) | 14 (82) | 41 (84) | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Tetracycline | 68 (53) | 21 (34) | 12 (71) | 35 (71) | 0.011 | <0.001 | |

| Trimethoprim | 68 (53) | 20 (32) | 10 (59) | 38 (78) | <0.001 | ||

| MDRc | 96 (75) | 32 (52) | 16 (94) | 48 (98) | 0.001 | <0.001 | |

| ESBLd | 60 (47) | 4 (6) | 10 (59) | 46 (94) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.002 |

| CTX-M-15 | 50 (39) | 1 (2) | 4 (24) | 45 (92) | 0.007 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

P values, by Fisher's (2-tailed) exact test, are shown where P < 0.05.

All isolates were susceptible to apramycin, colistin, and florfenicol.

MDR, multidrug resistant (resistant to ≥3 antimicrobial classes, with penicillins and cephalosporins counted separately).

ESBL, extended-spectrum beta-lactamase.

Most resistance phenotypes (i.e., ampicillin, ampicillin-sulbactam, cefotaxime, ciprofloxacin, nalidixic acid, sulfonamides, tetracycline, trimethoprim, ESBL production, and MDR status) were significantly associated with one or both H30 subclones compared with non-H30 isolates (Table 2). Additionally, within the H30 subclone, ESBL production and cefotaxime resistance were significantly associated with the H30-Rx subclone (Table 2).

Of the 60 (47%) ESBL producers, 50 (83%) contained blaCTX-M-15, the earliest being from 2005. blaCTX-M-15 was significantly associated with the H30 subclone (49/66 [74%] versus 1/62 [2%] others; P < 0.001) and, among H30 isolates, with H30-Rx (45/49 [92%] versus 4/17 [24%]; P < 0.001). Notably, all 7 food source or poultry source ST131 isolates, including 1 from meat (1996) and 6 from poultry (1997 and 2007), were ESBL negative.

Regarding the temporal sequence of appearance of specific resistance traits within ST131, of the 3 earliest ST131 isolates (all from 1968; non-H30 subset), 2 were pan-susceptible and 1 was MDR (resistant to ampicillin, amoxicillin-clavulanate, chloramphenicol, streptomycin, and spectinomycin) but susceptible to fluoroquinolones and extended-spectrum cephalosporins. Resistance to other antimicrobials within the non-H30 subset was first observed in 1972 (ciprofloxacin, nalidixic acid, neomycin, and tetracycline), 1981 (trimethoprim), 1985 (sulfonamides), and 2004 (extended-spectrum cephalosporins), i.e., ESBL phenotype. Whereas the earliest ESBL-producing isolate overall was a CTX-M-15-negative non-H30 isolate from 2004, the first ESBL-producing H30 isolate was a CTX-M-15-positive H30-Rx isolate from 2005.

Virulence genes.

Of the 50 ExPEC-associated virulence genes sought, all but 11 were detected in at least 1 isolate each, ranging in prevalence from 100% (usp [uropathogenic-specific protein], fyuA [yersiniabactin system], and fimH [type 1 fimbriae]) to 2% (sfaS [S fimbriae]) (Table 3). The 3 ST131 subgroups differed significantly with respect to virulence gene prevalence. Compared with non-H30 isolates, the H30 subclone was associated positively with iha (adhesin-siderophore), sat (secreted autotransporter toxin), and kpsM K2 and K100 (group 2 capsule variants) and negatively with pap genes (P fimbriae), hlyD (alpha hemolysin), hlyF (variant hemolysin), iroN (salmochelin receptor), cvaC (microcin V), iss (increased serum survival), and ibeA (invasion of brain endothelium). Within the H30 subclone, compared to H30 (non-Rx) isolates, the H30-Rx isolates were associated positively with afa and dra, kpsMII, and kpsM K2 and K100 but negatively with kfiC (K5 capsule).

TABLE 3.

Prevalence of virulence genotype subclone according to clonal subset among 128 archival ST131 Escherichia coli isolates (1968 to 2011)

| Virulence category | Specific virulence trait(s)b,c,d | No. (column %) of isolates with indicated trait |

P valuea |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n = 128) | Non-H30 (n = 62) | H30 (non-Rx) (n = 17) | H30-Rx (n = 49) | Non-H30 vs H30 (non-Rx) | Non-H30 vs H30-Rx | H30 (non-Rx) vs H30-Rx | ||

| Adhesins | afa and dra | 56 (44) | 19 (31) | 0 (0) | 37 (76) | 0.008 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| iha | 88 (69) | 24 (39) | 15 (88) | 49 (100) | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| papAH | 32 (25) | 27 (44) | 1 (6) | 4 (8) | 0.004 | <0.001 | ||

| papC | 38 (30) | 31 (50) | 1 (6) | 6 (12) | 0.002 | <0.001 | ||

| papEF | 36 (28) | 31 (50) | 1 (6) | 4 (8) | 0.002 | <0.001 | ||

| papG | 33 (26) | 28 (45) | 1 (6) | 4 (8) | 0.004 | <0.001 | ||

| papG II | 25 (20) | 19 (31) | 1 (6) | 5 (10) | 0.001 | |||

| Toxins | cdtB | 11 (9) | 11 (18) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.001 | ||

| hlyD | 22 (17) | 20 (32) | 1 (6) | 1 (2) | 0.03 | <0.001 | ||

| hlyF | 17 (13) | 14 (23) | 0 (0) | 3 (6) | 0.03 | 0.02 | ||

| sat | 84 (66) | 20 (32) | 15 (88) | 49 (100) | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| Siderophores | iron | 23 (18) | 20 (32) | 0 (0) | 3 (6) | 0.009 | <0.001 | |

| iutA | 108 (84) | 45 (72) | 15 (88) | 48 (98) | <0.001 | |||

| Protectins | cvaC | 16 (13) | 15 (24) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | 0.032 | 0.001 | |

| iss | 25 (20) | 22 (36) | 0 (0) | 3 (6) | 0.002 | <0.001 | ||

| K2 and K100 | 54 (42) | 16 (26) | 0 (0) | 38 (78) | 0.035 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| K5 | 16 (13) | 2 (3) | 8 (47) | 6 (12) | <0.001 | 0.005 | ||

| kpsM II | 113 (88) | 54 (87) | 10 (59) | 49 (100) | 0.015 | 0.009 | <0.001 | |

| Invasins | ibeA | 50 (39) | 49 (79) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

P values, by Fisher's (2-tailed) exact test, are shown where P < 0.05.

Traits shown in the table (where they are listed alphabetically by functional category): afa and dra (Dr family adhesins), cdtB (cytolethal distending toxin), cvaC (microcin V), hlyD (hemolysin), hlyF (hemolysin F), ibeA (invasion of brain endothelium), iha (adhesin-siderophore), iroN (siderophore receptor), iss (increased serum survival), iutA (aerobactin receptor), K2 and K100 (capsular antigen), kfiC (K5 capsular antigen), kpsM II (group 2 capsule), pap genes (operon corresponding to P fimbriae, including papAH [structural subunit], papC [assembly], papEF [tip pilins], and papG [adhesin], with allele II), sat (secreted autotransporter toxin).

Traits detected in ≥1 isolate each but not yielding a significant between-group difference (median occurrence level, 5%; range, 1% to 100%): astA (enteroaggregative heat-stable enterotoxin), cnf1 (cytotoxic necrotizing factor); fimH (type 1 fimbriae), fyuA (yersiniabactin receptor), hra (heat-resistant agglutinin), ireA (siderophore receptor), K1 capsular antigen, K15 capsular antigen, malX (pathogenicity island marker), ompT (outer membrane protease), papG allele III (cystitis-associated adhesins), sfaS (S fimbriae), traT (serum resistance associated), tsh (temperature-sensitive hemagglutinin), usp (uropathogen-specific protein).

Traits screened for but not detected in any isolate (definition, associated pathotype): afaA8, (afimbrial adhesin VIII), bmaE (M fimbriae), clbB and clbN (peptide-polyketide synthase), clpG (fimbrial adhesin CS31A), gafD (G fimbriae), f17 (F17 fimbriae), fliC (H7 flagellin), focG (F1C fimbriae), kpsMT III (group 3 capsules), papG allele I, vat (vacolating autotransporter), pic (protein involved in intestinal colonization), rfc (O4 lipopolysaccharide), sfa and focDE (S and F1C fimbriae).

Virulence scores ranged overall from 5 to 17 (median, 11). All 3 clonal subgroups differed significantly from one another, with non-H30 isolates having the highest scores (median virulence score, 12; range, 5 to 17), followed by H30-Rx isolates (median, 11; range, 9 to 15) and then H30 (non-Rx) isolates (median, 10; range, 7 to 12) (P < 0.001 for all pairwise comparisons).

Overall, 105 (82%) isolates fulfilled molecular criteria for ExPEC. These included 100% of the 49 H30-Rx isolates versus 77% of the 62 non-H30 isolates (P < 0.001) and 47% of the 17 H30 (non-Rx) isolates (P < 0.001).

Similarly, 96 (75%) isolates corresponded with 1 of the 9 virotypes and subtypes described recently by Mora et al. (9). These included, in order of descending frequency, virotypes A (n = 40), D (n = 32 [D1, 5; D2, 5; D3, 18; D4, 4; D5, 0]), C (n = 22), and B and E (n = 1 each) (Table 4). A different virotype predominated within each ST131 clonal subset, i.e., virotype D (52%) among non-H30 isolates, virotype C (76%) among H30 (non-Rx) isolates, and virotype A (67%) among H30-Rx isolates (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Prevalence of virotypes according to H30 subclone status among 128 archival ST131 Escherichia coli isolates (1968 to 2011)

| Virotype | No. (column %) of isolates with indicated virotype |

P valuea |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n = 128) | Non-H30 (n = 62) | H30, (non-Rx) (n = 17) | H30-Rx (n = 49) | Non-H30 vs H30 (non-Rx) | Non-H30 vs H30-Rx | H30 (non-Rx) vs H30-Rx | |

| Ab | 40 (31) | 7 (11) | 0 (0) | 33 (67) | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Bc | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | |||

| Cd | 22 (17) | 0 (0) | 13 (77) | 9 (18) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| D1 to D5e | 32 (25) | 32 (52) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Ef | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (<1) | 0 (0) | |||

| Other | 32 (25) | 23 (37) | 3 (18) | 6 (12) | 0.004 | ||

P values, by Fisher's (2-tailed) exact test, are shown where P < 0.05.

Virotype A: positive or negative for sat, positive for afa and draBC, positive for afa operon FM955459, negative for ibeA, ironN, papGII, papGIII, cnf1, hlyA, cdtB, and neuCK1.

Virotype B: positive for ironN, positive or negative for sat, negative for all of the other genes listed.

Virotype C: positive for sat, negative for all of the other genes listed.

Virotype D: positive for ibeA, positive or negative for ironN, positive or negative for sat, positive or negative for afa and draBC, positive or negative for afa operon FM955459, positive or negative for papGIII, positive or negative for cnf1, positive or negative for hlyA, positive or negative for cdtB, positive or negative for neuCK1, negative for papGII. D subtypes (number of isolates): D1 (5), D2 (5), D3 (18), D4 (4), and D5 (0).

Virotype E: positive for sat, positive for papGII, positive for cnf1, positive for hlyA, negative for all of the other genes listed.

Additionally, 12 (19%) non-H30 ST131 isolates (all from 1998 to 2004), versus no (0%) H30 subclone isolates, fulfilled molecular criteria for EAEC (P < 0.001). Eleven of these were gentamicin-resistant isolates from the Copenhagen area collected in 1998 to 2000. Of the 11, 6 were pap-positive urine isolates from patients with a urinary tract infection (UTI) and 3 were pap-negative fecal isolates from patients with diarrhea. Biofilm production was significantly associated with EAEC isolates, being present in 8/12 (67%) EAEC isolates versus 10/116 (9%) other isolates (P < 0.001).

Temporal trends.

Resistance scores increased significantly over time within ST131 overall by an estimated 33% per decade according to regression analysis (P < 0.001). However, the individual clonal subsets exhibited no such temporal increase (Table 5). In contrast, biofilm production was associated with earlier years of submission (P = 0.01). Virulence scores did not change significantly over time, within either ST131 overall or the individual clonal subsets. ExPEC status increased significantly in frequency over time, both overall (by an estimated 65% per decade; P = 0.005) and specifically within the non-H30 subset (by an estimated 33% per decade; P = 0.039), but not within the 2 H30-associated subclones. Virotype D (non-H30-associated) was found earliest, i.e., from 1968 onward (median year, 1998; P < 0.001 versus other isolates), and with a single exception was the sole virotype present until 2000. In contrast, virotype A (H30-Rx-associated) was found predominantly after 2000 (median year, 2010; P < 0.001 versus other isolates) and virotype C (H30 [non-Rx-associated]) only after 2002.

TABLE 5.

Association of feature with clonal subset and with temporal trend within the subset among 128 archival ST131 Escherichia coli isolates (1968 to 2011)

| Parameter or feature | Relative score or prevalence or level of feature within clonal subset, temporal trend |

Temporal trend overall | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-H30 (n = 62) | H30 (non-Rx) (n = 17) | H30-Rx (n = 49) | ||

| Virulence score | Highest (median, 12), stable | Lowest (median, 10), stable | Medium (median, 11), stable | None |

| ExPECa | Medium, rising | Low, stable | High, stable | Rising |

| Virotype A | None | Low, stable | High, stable | Rising |

| Virotype C | None | High, stable | Low, stable | Rising |

| Virotype D | Medium, stable | None | None | Falling |

| EAECb | Low, stable | None | None | Falling |

| Capsular antigen K100 | None | None | High, stable | Rising |

| Capsular antigen K2 | Low | None | Low | Stable |

| Capsular antigen K5 | Low | Medium | Low | Stable |

| Capsular antigen K16 | Low | None | None | Falling |

| Resistance score | Medium, stable | High, stable | High, stable | Rising |

| ESBLc | Low, rising | Medium, stable | High, stable | Rising |

| Biofilm production | Low, stable | None | None | Falling |

ExPEC, extraintestinal pathogenic E. coli.

EAEC, (diarrheagenic) enteroaggregative E. coli.

ESBL, extended-spectrum-beta-lactamase production.

PFGE analysis.

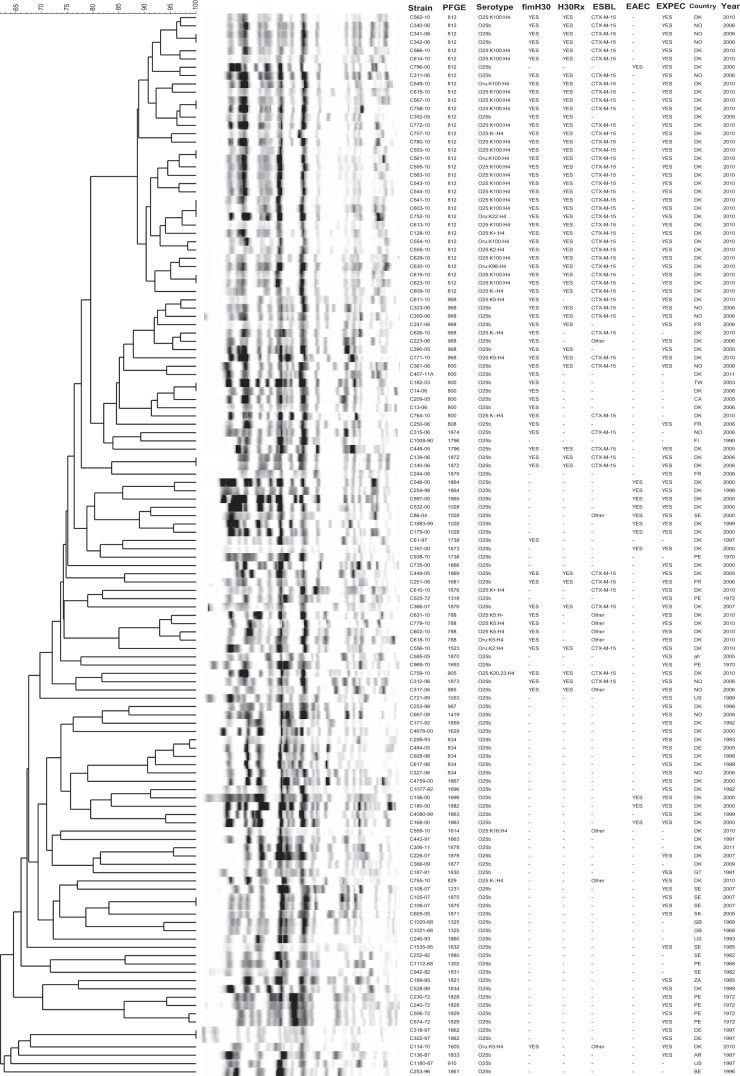

Overall, the 128 study isolates exhibited 59 different pulsotypes, each represented by from 1 to 34 isolates. The most prevalent pulsotypes (pulsotypes 812, 968, 800, 834, 1028, and 788) were also among the most prevalent pulsotypes in a large private library of global ST131 PFGE profiles (29). In a PFGE dendrogram (Fig. 1), earlier isolates tended to occupy the lower, more basal region of the tree and to have highly dissimilar profiles that represented novel (higher-number) pulsotypes. In contrast, the more recent isolates tended to occupy the upper region of the tree and to have more highly similar profiles that represented established (lower-number) pulsotypes.

FIG 1.

Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) analysis of 128 archival ST131 Escherichia coli isolates (1968 to 2011). The dendrogram was inferred within the Bionumerics program according to the unweighted pair group method based on Dice similarity coefficients. Designation abbreviations: PFGE, pulsotype; fimH30, H30 ST131 subclone; H30Rx, H30-Rx ST131 subclone; ESBL, extended-spectrum-beta-lactamase production; EAEC, (diarrheagenic) enteroaggregative Escherichia coli; year, year in which isolate was received at the WHO Reference Centre. Country abbreviations: afr, Afghanistan; AR, Argentina; BE, Belgium; CA, Canada; DE, Germany; DK, Denmark; FI, Finland; FR, France; GB, United Kingdom; GT, Guatemala; NO, Norway; PE, Peru; SE, Sweden; SK, Slovakia; TW, Taiwan; US, United States; ZA, South Africa.

Eight clusters of isolates with indistinguishable profiles, each containing 2 to 3 isolates, were found. Of these 8 clusters, 6 were in the upper (more homogeneous) region of the tree and 2 in the lower (more diverse) region of the tree. In 7 of 8 such clusters, the grouped isolates were from the same locale and year (Denmark 2010 [n = 3]; Denmark 2006; Norway 2006; Sweden 2007; Germany 1997), suggesting local endemicity or repeated isolation from the same source. The exceptional set comprised an isolate from Taiwan collected in 2003 and another from Denmark collected in 2006, suggesting international transmission.

The H30-Rx isolates, most of which exhibited virotype A and CTX-M-15, largely clustered together, as generally did the representatives of other specific virotypes. Eight (67%) of the 12 EAEC isolates, all non-H30, from1998 to 2004, also clustered tightly together. Of these, 7, including 3 urine isolates from patients with UTI, 3 fecal isolates from patients with diarrhea, and 1 lower respiratory tract isolate, were from the Copenhagen area (1998 to 2000).

DISCUSSION

In this molecular epidemiological study, to gain insights into why ST131 has become so epidemiologically successful since 2000, we analyzed a unique, 43-year archival collection of 128 historic and recent E. coli ST131 isolates (1968 to 2011) for temporal trends involving fitness-associated traits and clonal subsets. We found that antimicrobial resistance has become progressively more prevalent and extensive within ST131 over time, particularly over the past decade, but that the change is the result of the recent appearance of the H30 and H30-Rx subclones (3–5), with their extensive resistance profiles, rather than of a generalized temporal increase in resistance. We also found temporal increases in the proportion of isolates qualifying as ExPEC and representing virulence-associated virotypes A and C (9); these likewise were explained by temporal shifts in subgroup prevalence. In contrast, we found no overall temporal increases in total virulence gene content or the prevalence of EAEC or biofilm production; indeed, the latter two characteristics actually decreased significantly over time. These findings support the idea that ST131's recent expansion may be attributable to the enhanced antimicrobial resistance and virulence capabilities of the recently emerged H30 and H30-Rx ST131 subclones.

Regarding antimicrobial resistance, whereas resistance scores increased over time in the total population by an estimated 33% per decade (P < 0.001), no such temporal increase occurred within the individual clonal subsets, i.e., the non-H30, H30 (non-Rx), and H30-Rx subsets. However, the clonal subsets differed greatly with respect to the extent of resistance, with H30 and its two subcomponents having much higher resistance scores (median, 9; range, 2 to 13) than non-H30 isolates (median, 4; range, 0 to 10). Thus, the seeming overall temporal trend toward more-extensive resistance was attributable to the recent appearance of the H30 subclone. In accordance with previous studies, fluoroquinolone resistance was associated with the entire H30 subclone, whereas both ESBL production and CTX-M-15 were associated specifically with its H30-Rx subset (3–5).

Fluoroquinolone resistance, a hallmark of the current ST131 pandemic, appeared first in 1972, in a non-H30 isolate. However, this apparently led to no epidemic expansion, suggesting that fluoroquinolone resistance per se is unlikely to have been the main driver of the (later-appearing) H30 ST131 subclone's striking epidemiologic success. The intensity of fluoroquinolone resistance also may be important, since although this isolate's ciprofloxacin MIC of 0.25 μg/ml greatly exceeded the epidemiologic resistance cutoff point (>0.06 μg/ml), current (H30 subclone) ciprofloxacin-resistant ST131 isolates typically have much higher ciprofloxacin MICs (31). Additionally, although this “pioneer” fluoroquinolone-resistant non-H30 ST131 isolate qualified molecularly as ExPEC, it did not belong to a defined virotype, contained relatively few virulence genes (n = 5), and was ESBL negative, features possibly contributing to it being an apparent evolutionary dead end.

Among the present study isolates, non-H30 isolates came first historically, from as early as 1968, which corresponds closely with the appearance of the earliest previously reported ST131 isolate, collected in 1967 (5). The H30 subclone first appeared here 30 years later, in 1997, represented by what to our knowledge is the earliest reported H30 subclone isolate, an MDR, non-ESBL Danish poultry isolate. In contrast to all subsequent H30 subclone study isolates, that isolate was fluoroquinolone susceptible; the first fluoroquinolone-resistant H30 isolate was from 6 years later, in 2003. Finally, the H30-Rx subset was not observed until 2005, accompanied by CTX-M-15—although previous studies have identified H30-Rx isolates from as early as 2002. This chronological sequence of appearance, i.e., non-H30, then H30 (non-Rx), and then H30-Rx, corresponds with the molecular phylogeny of ST131, which shows the H30 lineage to be an offshoot from the ancestral (non-H30) ST131 trunk, initially fluoroquinolone susceptible but later developing fluoroquinolone resistance and subsequently giving rise to the (CTX-M-15-associated) H30-Rx subclone. Our findings thus are in accordance with recent reports suggesting that the high prevalence of blaCTX-M-15 among ST131 isolates is due primarily to the expansion of a single, highly virulent subclone, H30-Rx, within which blaCTX-M-15 is transmitted vertically (4, 32).

Regarding virulence genes, we found that, paradoxically, ancestral non-H30 strains actually had significantly higher virulence scores than did members of the more recent and successful H30 (non-Rx) and H30-Rx subclones. This suggests that, if the studied virulence genes have contributed to the H30 subclone's success, this effect must have been mediated by particular virulence genes, specific combinations thereof, and/or different levels of expression, rather than by the total number of virulence genes.

Our findings regarding virulence scores conflict with those of Banerjee et al. (33), according to which H30 and H30-Rx isolates had higher scores than non-H30 ST131 isolates. Although we studied considerably more non-H30 isolates than did Banerjee et al. (i.e., 62 versus 9), providing more-reliable prevalence estimates, the present isolates also were submitted to the WHO Centre for diverse, often unknown reasons, which introduces possible (undefined) biases. The ideal substrate for such an analysis would be a large and systematically assembled collection of concurrent H30 and non-H30 isolates from similar sources.

ExPEC status is inferred from specific combinations of virulence genes (24). Although the prevalence of ExPEC increased significantly over time overall and was highest among H30-Rx isolates (100%), it paradoxically was lowest among the H30 (non-Rx) isolates, despite the known epidemic success of this subclone. Moreover, at the clonal subset level, ExPEC prevalence increased significantly over time only among non-H30 isolates, which have not been particularly epidemiologically successful. This suggests that, within ST131, fulfillment of the study's molecular definition of ExPEC does not correspond closely with epidemic success.

Likewise, specific virulence gene combinations define the so-called virotypes of ST131, of which Blanco et al. initially delineated four (34) and Mora et al. later delineated nine, including subtypes (9). Here, virotype D (earliest appearance; median year, 1998) was associated with non-H30 isolates, virotype C (intermediate appearance; median year, 2006) with H30 (non-Rx) isolates, and virotype A (most recent appearance; median year, 2010) with H30-Rx isolates (Table 4). The observed overall temporal trends for virotypes were explained by shifts in subgroup distributions within ST131 resulting from the emergence of the H30 subclone and, subsequently, its H30-Rx subset.

As for biofilm production, we found a much lower prevalence of this phenotype among the present ST131 study isolates, both overall (15%) and, especially, among those from the H30 subclone (3%), than Kudinha et al. found among fecal and urine ST131 isolates from women in Australia (96%) (35). This discrepancy could be due to differences in methods, definitions, and/or the clonal compositions of the respective study populations, since here biofilm production was significantly associated with non-H30 isolates. Regardless, our findings clearly point away from biofilm as an explanation for the epidemiologic success of the H30 subclone.

In contrast, we found that biofilm production was strongly associated with EAEC (P < 0.001), a diarrheagenic pathotype. This is, to our knowledge, the first report of ST131 isolates being EAEC. The cluster of eight EAEC ST131 isolates in the PFGE dendrogram (Fig. 1) supports the hypothesis of the occurrence of an unrecognized UTI outbreak and possibly also of a diarrhea outbreak in the Copenhagen area in 1998 to 2000. Three fecal isolates from patients with diarrhea in 2000 from the same area clustered with the UTI isolates, indicating that this subclone is possibly able to cause both UTI and diarrhea. This possible ST131 EAEC outbreak is reminiscent of a recently reported UTI outbreak in Copenhagen caused by an E. coli O78:H10 clonal group that both fulfilled molecular criteria for EAEC and contained multiple ExPEC virulence genes (12). That outbreak strain's EAEC-associated virulence factors were found to increase uropathogenicity (13), suggesting that this may be true also for ST131 EAEC strains.

We also uniquely documented here a significant temporal shift in capsular antigens within ST131. The most striking of these involved the K100 antigen, which was not observed until 2005 and occurred exclusively among H30-Rx isolates, accounting for 55% of this subclone, versus no other ST131 isolates (P < 0.001). It is plausible that the K100 capsule confers enhanced virulence to H30-Rx subclone members, analogous to the well-known contribution of the K1 capsule to the pathogenesis of E. coli neonatal meningitis (36), and could be used as a vaccine target for a risk population.

There was a generally good, yet incomplete, correspondence of PFGE with H30 and H30-Rx status, which illustrates the limited phylogenetic validity of PFGE analysis, as demonstrated by Price et al. (4). In the PFGE dendrogram (Fig. 1), earlier isolates tended to occupy the lower region of the tree and to have highly dissimilar profiles that represented novel (higher-number) pulsotypes, consistent with greater genetic diversity, possibly reflecting a longer time for diversification. In contrast, more-recent isolates tended to occupy the upper region of the tree and to have profiles that were more highly similar, consistent with greater genetic homogeneity, possibly reflecting more recent emergence. Thus, the tree serves as a timeline for the clonal group, moving from older/more diverse at the base (bottom) to newer/more homogeneous at the top, with H30 and H30-Rx “topping the tree” as the newest variants within the clonal group.

Table 5 summarizes the divergent trends for the multiple study variables. Both the overall extent of antimicrobial resistance among ST131 isolates and the prevalence specifically of fluoroquinolone resistance and ESBL production have risen significantly over time. Likewise, despite stable aggregate virulence scores, temporal shifts in the prevalence of particular virulence factors have resulted in an increasing prevalence of ExPEC status, a switch from virotype D toward virotypes A and C, and a rising prevalence of capsular antigen K100. These overall temporal trends can be explained by shifts in the prevalence of important clonal subsets within ST131. In contrast, the only documented temporal trend within an individual clonal subgroup was the rising prevalence of ExPEC status among the members of the (epidemiologically unsuccessful) non-H30 subset.

This study had several limitations. The relatively small sample size, especially for H30 (non-Rx) isolates, limited its statistical power, whereas the use of multiple comparisons increased the likelihood of finding significant differences by chance alone. The convenience sample approach and unknown clinical background of most isolates introduced possible biases and limited generalizability. For example, although the higher number of ST131 isolates detected after 2000 probably reflects mainly the widespread emergence of ST131 as a multidrug-resistant pathogen, the two ESBL studies conducted in this decade contributed some of the present study isolates. Finally, only a subset of possible bacterial characteristics was assessed.

The study also had notable strengths. The unique strain set spanned a 43-year sampling interval, allowing temporal trend analyses plus identification of the earliest ST131 isolate of known source (from 1981), the earliest known fluoroquinolone-resistant ST131 isolate (from 1972), and the earliest known H30 ST131 isolate (from 1997). The extensive characterization of the isolates allowed novel comparisons between clonal subsets according to resistance and virulence profiles, capsular antigens, ExPEC and EAEC status, virotypes, biofilm production, and serotypes.

In summary, our findings confirm that ST131 O25 should be regarded not as a unified entity but as a cluster of distinct clonal subsets. Accordingly, the overall temporal increase in resistance within ST131 has a strong clonal basis, being attributable mainly to the emergence of the H30 and H30-Rx ST131 subclones rather than to a generalized acquisition of resistance by diverse ST131 strains. Virotypes A and C, combined with high-level fluoroquinolone resistance, might have contributed to the success of the H30 subclone overall. The distinctive characteristics associated with the H30-Rx subclone, i.e., specific ExPEC virulence factors (iutA, afa and dra, kpsII), virotype A, the K100 capsule (which might serve as a vaccine target), and multidrug resistance, including ESBL production, possibly contributed to this subclone's recent epidemiologic success.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This material is based on work supported by Office of Research and Development, Medical Research Service, Department of Veterans Affairs, grant 1 I01 CX000192 01 (J.R.J.). B.O. received grants from Herlev Hospital.

We thank Neil Woodford, Head, Antimicrobial Resistance and Healthcare Associated Infections Reference Unit, Public Health England, London, United Kingdom, and Arnfinn Sundsfjord, National Reference Laboratory for Detection of Antimicrobial Resistance (K-res), Department of Clinical Microbiology and Infection Control, University Hospital of North Norway, Tromsø, Norway, for contributing isolates of ST131.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 8 September 2014

REFERENCES

- 1.Rogers BA, Sidjabat HE, Paterson DL. 2011. Escherichia coli O25b-ST131: a pandemic, multiresistant, community-associated strain. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 66:1–14. 10.1093/jac/dkq415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnson JR, Johnston B, Clabots C, Kuskowski MA, Castanheira M. 2010. Escherichia coli sequence type ST131 as the major cause of serious multidrug-resistant E. coli infections in the United States. Clin. Infect. Dis. 51:286–294. 10.1086/653932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banerjee R, Strahilevitz J, Johnson JR, Nagwekar PP, Schora DM, Shevrin I, Du H, Peterson LR, Robicsek A. 2013. Predictors and molecular epidemiology of community-onset extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli infection in a midwestern community. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 34:947–953. 10.1086/671725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Price LB, Johnson JR, Aziz M, Clabots C, Johnston B, Tchesnokova V, Nordstrom L, Billig M, Chattopadhyay S, Stegger M, Andersen PS, Pearson T, Riddell K, Rogers P, Scholes D, Kahl B, Keim P, Sokurenko EV. 2013. The epidemic of extended-spectrum-beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli ST131 is driven by a single highly pathogenic subclone, H30-Rx. mBio 4:e00377-13. 10.1128/mBio.00377-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson JR, Tchesnokova V, Johnston B, Clabots C, Roberts PL, Billig M, Riddell K, Rogers P, Qin X, Butler-Wu S, Price LB, Aziz M, Nicolas-Chanoine MH, Debroy C, Robicsek A, Hansen G, Urban C, Platell J, Trott D, Zhanel G, Weissman SJ, Cookson BT, Fang FC, Limaye A, Scholes D, Chattopadhyay S, Hooper DC, Sokurenko EV. 3 January 2013. Abrupt emergence of a single dominant multi-drug-resistant strain of Escherichia coli. J. Infect. Dis 10.1093/infdis/jis933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nicolas-Chanoine MH, Bertrand X, Madec JY. 2014. Escherichia coli ST131, an intriguing clonal group. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 27:543–574. 10.1128/CMR.00125-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Banerjee R, Johnson JR. 2014. A new clone sweeps clean: the enigmatic emergence of Escherichia coli sequence type 131. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 58:4997–5004. 10.1128/AAC.02824-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Olesen B, Hansen DS, Nilsson F, Frimodt-Møller J, Leihof RF, Struve C, Scheutz F, Johnston B, Krogfelt KA, Johnson JR. 2013. Prevalence and characteristics of the epidemic multiresistant Escherichia coli ST131 clonal group among extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing E. coli isolates in Copenhagen, Denmark. J. Clin. Microbiol. 51:1779–1785. 10.1128/JCM.00346-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mora A, Dahbi G, Lopez C, Mamani R, Marzoa J, Dion S, Picard B, Blanco M, Alonso MP, Denamur E, Blanco J. 2014. Virulence patterns in a murine sepsis model of ST131 Escherichia coli clinical isolates belonging to serotypes O25b:H4 and O16:H5 are associated to specific virotypes. PLoS One 9:e87025. 10.1371/journal.pone.0087025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Colpan A, Johnston B, Porter S, Clabots C, Anway R, Thao L, Kuskowski MA, Tchesnokova V, Sokurenko EV, Johnson JR, VICTORY (Veterans Influence of Clonal Types on Resistance: Year 2011) Investigators 2013. Escherichia coli sequence type 131 (ST131) subclone H30 as an emergent multidrug-resistant pathogen among US veterans. Clin. Infect. Dis. 57:1256–1265. 10.1093/cid/cit503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kudinha T, Johnson JR, Andrew SD, Kong F, Anderson P, Gilbert GL. 2013. Genotypic and phenotypic characterization of Escherichia coli isolates from children with urinary tract infection and from healthy carriers. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 32:543–548. 10.1097/INF.0b013e31828ba3f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Olesen B, Scheutz F, Andersen RL, Menard M, Boisen N, Johnston B, Hansen DS, Krogfelt KA, Nataro JP, Johnson JR. 2012. Enteroaggregative Escherichia coli O78:H10, the cause of an outbreak of urinary tract infection. J. Clin. Microbiol. 50:3703–3711. 10.1128/JCM.01909-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boll EJ, Struve C, Boisen N, Olesen B, Stahlhut SG, Krogfelt KA. 2013. Role of enteroaggregative Escherichia coli virulence factors in uropathogenesis. Infect. Immun. 81:1164–1171. 10.1128/IAI.01376-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dhanji H, Doumith M, Clermont O, Denamur E, Hope R, Livermore DM, Woodford N. 2010. Real-time PCR for detection of the O25b-ST131 clone of Escherichia coli and its CTX-M-15-like extended-spectrum beta-lactamases. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 36:355–358. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2010.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnson JR, Menard M, Johnston B, Kuskowski MA, Nichol K, Zhanel GG. 2009. Epidemic clonal groups of Escherichia coli as a cause of antimicrobial-resistant urinary tract infections in Canada, 2002 to 2004. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:2733–2739. 10.1128/AAC.00297-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Naseer U, Haldorsen B, Tofteland S, Hegstad K, Scheutz F, Simonsen GS, Sundsfjord A, ESBL Norwegian Study Group 2009. Molecular characterization of CTX-M-15-producing clinical isolates of Escherichia coli reveals the spread of multidrug-resistant ST131 (O25:H4) and ST964 (O102:H6) strains in Norway. APMIS 117:526–536. 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2009.02465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ørskov F, Ørskov I. 1984. Serotyping of Escherichia coli, p 43–112 In Bergan T. (ed), Methods in microbiology, vol. 14 Academic Press, London, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Konowalchuk J, Speirs JI, Stavric S. 1977. Vero response to a cytotoxin of Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 18:775–779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnson JR, Urban C, Weissman SJ, Jorgensen JH, Lewis JS, II, Hansen G, Edelstein PH, Robicsek A, Cleary T, Adachi J, Paterson D, Quinn J, Hanson ND, Johnston BD, Clabots C, Kuskowski MA, AMERECUS Investigators 2012. Molecular epidemiological analysis of Escherichia coli sequence type ST131 (O25:H4) and blaCTX-M-15 among extended-spectrum-beta-lactamase-producing E. coli from the United States, 2000 to 2009. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56:2364–2370. 10.1128/AAC.05824-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson JR, Owens K, Manges AR, Riley LW. 2004. Rapid and specific detection of Escherichia coli clonal group A by gene-specific PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:2618–2622. 10.1128/JCM.42.6.2618-2622.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson JR, Owens KL, Clabots CR, Weissman SJ, Cannon SB. 2006. Phylogenetic relationships among clonal groups of extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli as assessed by multi-locus sequence analysis. Microbes Infect. 8:1702–1713. 10.1016/j.micinf.2006.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnson JR, Stell AL. 2000. Extended virulence genotypes of Escherichia coli strains from patients with urosepsis in relation to phylogeny and host compromise. J. Infect. Dis. 181:261–272. 10.1086/315217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson JR, Stell AL, Scheutz F, O'Bryan TT, Russo TA, Carlino UB, Fasching C, Kavle J, Van Dijk L, Gaastra W. 2000. Analysis of the F antigen-specific papA alleles of extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli using a novel multiplex PCR-based assay. Infect. Immun. 68:1587–1599. 10.1128/IAI.68.3.1587-1599.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnson JR, Murray AC, Gajewski A, Sullivan M, Snippes P, Kuskowski MA, Smith KE. 2003. Isolation and molecular characterization of nalidixic acid-resistant extraintestinal pathogenic Escherichia coli from retail chicken products. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:2161–2168. 10.1128/AAC.47.7.2161-2168.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnson JR, O'Bryan TT. 2004. Detection of the Escherichia coli group 2 polysaccharide capsule synthesis gene kpsM by a rapid and specific PCR-based assay. J. Clin. Microbiol. 42:1773–1776. 10.1128/JCM.42.4.1773-1776.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boisen N, Scheutz F, Rasko DA, Redman JC, Persson S, Simon J, Kotloff KL, Levine MM, Sow S, Tamboura B, Toure A, Malle D, Panchalingam S, Krogfelt KA, Nataro JP. 2012. Genomic characterization of enteroaggregative Escherichia coli from children in Mali. J. Infect. Dis. 205:431–444. 10.1093/infdis/jir757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ribot EM, Fair MA, Gautom R, Cameron DN, Hunter SB, Swaminathan B, Barrett TJ. 2006. Standardization of pulsed-field gel electrophoresis protocols for the subtyping of Escherichia coli O157:H7, Salmonella, and Shigella for PulseNet. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 3:59–67. 10.1089/fpd.2006.3.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tenover FC, Arbeit RD, Goering RV, Mickelsen PA, Murray BE, Persing DH, Swaminathan B. 1995. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial strain typing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 33:2233–2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johnson JR, Nicolas-Chanoine MH, DebRoy C, Castanheira M, Robicsek A, Hansen G, Weissman S, Urban C, Platell J, Trott D, Zhanel G, Clabots C, Johnston BD, Kuskowski MA, MASTER Investigators 2012. Comparison of Escherichia coli ST131 pulsotypes, by epidemiologic traits, 1967–2009. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 18:598–607. 10.3201/eid1804.111627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hansen DS, Schumacher H, Hansen F, Stegger M, Hertz FB, Schønning K, Justesen US, Frimodt-Møller N, DANRES Study Group 2012. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) in Danish clinical isolates of Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae: prevalence, beta-lactamase distribution, phylogroups, and co-resistance. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 44:174–181. 10.3109/00365548.2011.632642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cerquetti M, Giufre M, Garcia-Fernandez A, Accogli M, Fortini D, Luzzi I, Carattoli A. 2010. Ciprofloxacin-resistant, CTX-M-15-producing Escherichia coli ST131 clone in extraintestinal infections in Italy. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 16:1555–1558. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2010.03162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Petty NK, Ben Zakour NL, Stanton-Cook M, Skippington E, Totsika M, Forde BM, Phan MD, Gomes Moriel D, Peters KM, Davies M, Rogers BA, Dougan G, Rodriguez-Bano J, Pascual A, Pitout JD, Upton M, Paterson DL, Walsh TR, Schembri MA, Beatson SA. 31 March 2014. Global dissemination of a multidrug resistant Escherichia coli clone. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 10.1073/pnas.1322678111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Banerjee R, Robicsek A, Kuskowski MA, Porter S, Johnston BD, Sokurenko E, Tchesnokova V, Price LB, Johnson JR. 2013. Molecular epidemiology of Escherichia coli sequence type 131 and its H30 and H30-Rx subclones among extended-spectrum-beta-lactamase-positive and -negative E. coli clinical isolates from the Chicago region, 2007 to 2010. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57:6385–6388. 10.1128/AAC.01604-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Blanco J, Mora A, Mamani R, López C, Blanco M, Dahbi G, Herrera A, Marzoa J, Fernández V, de la Cruz F, Martínez-Martínez L, Alonso MP, Nicolas-Chanoine MH, Johnson JR, Johnston B, López-Cerero L, Pascual A, Rodríguez-Baño J, Spanish Group for Nosocomial Infections (GEIH) 2013. Four main virotypes among extended-spectrum-beta-lactamase-producing isolates of Escherichia coli O25b:H4-B2-ST131: bacterial, epidemiological, and clinical characteristics. J. Clin. Microbiol. 51:3358–3367. 10.1128/JCM.01555-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kudinha T, Johnson JR, Andrew SD, Kong F, Anderson P, Gilbert GL. 2013. Distribution of phylogenetic groups, sequence type ST131, and virulence-associated traits among Escherichia coli isolates from men with pyelonephritis or cystitis and healthy controls. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 19:E173–E180. 10.1111/1469-0691.12123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Korhonen TK, Valtonen MV, Parkkinen J, Väisänen-Rhen V, Finne J, Orskov F, Orskov I, Svenson SB, Mäkelä PH. 1985. Serotypes, hemolysin production, and receptor recognition of Escherichia coli strains associated with neonatal sepsis and meningitis. Infect. Immun. 48:486–491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]