Abstract

We here report on the in vitro activity of toremifene to inhibit biofilm formation of different fungal and bacterial pathogens, including Candida albicans, Candida glabrata, Candida dubliniensis, Candida krusei, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus, and Staphylococcus epidermidis. We validated the in vivo efficacy of orally administered toremifene against C. albicans and S. aureus biofilm formation in a rat subcutaneous catheter model. Combined, our results demonstrate the potential of toremifene as a broad-spectrum oral antibiofilm compound.

TEXT

Biofilm formation is a key process in many microbial infections, including those of the oral cavity, the gastrointestinal tract, the urinary tract, and various wound tissues. It is estimated that 60% (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) to 80% (National Institutes of Health) of all microbial infections are biofilm related. Additionally, numerous nosocomial biofilm infections arise from the increased use of implanted medical devices, like intravascular catheters, which are a preferred niche for microbial cell adherence (1). Such catheters frequently become colonized with pathogenic Candida or Staphylococcus spp., especially in intensive care units (2, 3). Biofilm-related infections are associated with a high mortality rate, and therefore, the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) suggest that infected medical devices be removed when possible (4, 5). However, removal of infected devices in less accessible locations, such as orthopedic joints or heart valves, or in patients with a reduced health condition might be impossible (2, 6, 7). Unfortunately, in the case of fungal biofilm infections, most antifungal drugs show only limited antibiofilm activity, with echinocandins (e.g., caspofungin) and liposomal formulations of amphotericin B being the most effective (2). Antifungal lock therapy to apply these compounds can be successful but is restricted to devices with an internal space. For treatment of other devices and for systemic treatments, these compounds need to be administered intravenously, as they are not absorbed after oral administration (5, 8). To combat bacterial biofilm infection, the major therapeutic strategy is the use of antibiotics. However, the intrinsic and adaptive resistance of bacterial biofilms to current antibiotics, as well as to host immune clearance mechanisms, has led to a growing problem in health care settings. Staphylococcus aureus is a major human pathogen and is one of the most common pathogens in biofilm-associated device infections (9, 10). Traditional antistaphylococcal beta-lactam antibiotics like cephalexin are ineffective in clearing methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) infections. Currently, glycopeptide antibiotics (e.g., vancomycin) are often used in patients as a first-line treatment to target both methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA) and MRSA infections (11, 12). However, the oral absorption of vancomycin is very low and, as a consequence, this agent must be administered intravenously to control systemic infections (13). Alternatives, including the recently introduced oxazolidinone linezolid and the cyclic lipopeptide daptomycin, are available but the search for novel compounds to treat S. aureus infections remains crucial (14).

In a previous study, we screened a repurposing library (i.e., a library containing drugs known for their application in specific medical domains) for compounds that can inhibit biofilm formation of Candida albicans and/or can increase the activity of well-known antifungal agents against C. albicans biofilms. This led to the identification of the FDA-approved anticancer drug toremifene citrate (referred to hereafter as toremifene) as a potent inhibitor of both C. albicans and Candida glabrata biofilm formation (15). The activity of toremifene against estrogen receptor-positive (ER+) breast cancer is based on its ability to bind the ER, thereby blocking estrogen binding and leading to inhibition of tumor growth (16). We already showed that the antibiofilm activity of toremifene against C. albicans is partly mediated by membrane permeabilization (15). Butts and colleagues further demonstrated that the fungicidal activity of toremifene against Cryptococcus neoformans is based on inhibition of calcineurin signaling via calmodulin binding (17). The findings of these two studies regarding the antifungal/antibiofilm mode of action of toremifene are in line with the well documented antifungal mechanism of action of its close analogue tamoxifen, which is based on membrane perturbation and interference with calcium homeostasis and calcineurin signaling (18–20). In the present study, we report on the broad-spectrum antibiofilm activity of toremifene in vitro. In addition, we translated these results in vivo and show activity of toremifene against C. albicans and S. aureus biofilm formation in a rat subcutaneous catheter model (21), importantly, via simple oral administration.

We used the BIC-2 value (minimal concentration of the compound that inhibits biofilm formation 2-fold) to assess the antibiofilm activity of toremifene (TCI Europe, Zwijndrecht, Belgium) for different fungal and bacterial species (Table 1). As a control treatment, we included caspofungin. The in vitro antibiofilm activities of toremifene and caspofungin against Candida spp. were assayed in RPMI 1640 medium and quantified with the 2,3-bis(2-methoxy-4-nitro-5-sulfophenyl)-5-[(phenylamino)carbonyl]-2H-tetrazolium hydroxide (XTT) assay (22). Briefly, toremifene (0.78 to 100 μM, 0.5% dimethyl sulfoxide [DMSO] background) was added during the adhesion (1 h at 37°C) and biofilm formation (24 h at 37°C) phases. Afterwards, biofilms were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and quantified with XTT as described previously (15). XTT can be metabolized within 1 h by all fungal species tested, in contrast to cell titer blue (CTB), which was used in our initial study (15). We observed comparable in vitro antibiofilm activities of toremifene against C. albicans, C. glabrata, Candida dubliniensis, and Candida krusei, albeit less potent than those of caspofungin (Table 1). Subsequently, three clinical isolates of C. albicans (2CA, 10CA, and 15CA) that form high-persister biofilms (23) were assessed. Persister cells can survive high doses of an antimicrobial agent and partly explain the recalcitrance of chronic infectious diseases against antimicrobial therapy (24, 25). Interestingly, C. albicans CA2 is susceptible to toremifene, whereas C. albicans CA10 and CA15 are more resistant (P < 0.01 and P < 0.00001, respectively, by unpaired two-tailed Student's t test). The activity of toremifene against planktonic C. albicans cells was assessed according to the CLSI M27-A3 protocol (26). The MIC-2 (i.e., the MIC of the compound that reduces growth by 2-fold relative to the results for the growth control [0.5% DMSO]) for toremifene against C. albicans is 49.7 ± 10.1 μM (mean ± standard error of the mean [SEM]), which is comparable to its BIC-2 value against C. albicans (36 ± 2 μM) (Table 1). The latter observation indicates that toremifene has no biofilm-specific activity and does not interfere specifically with the biofilm formation process. The in vitro antibiofilm activities of toremifene against bacterial spp. were assayed using a Calgary biofilm device (Nunc-Immuno TSP [transferable solid-phase] replicator; VWR International). To this end, biofilms were grown on the polystyrene pegs of the Calgary biofilm device for 24 h at 37°C in the presence of a range of concentrations of toremifene (0 to 200 μM in a 0.5% DMSO background for Staphylococcus spp. and a 1% DMSO background for Pseudomonas aeruginosa). Next, the biofilms were disrupted and cells were collected in recovery medium using sonication, after which the number of viable cells was assessed by plate counting (27). Our results indicate that toremifene prevents in vitro biofilm formation of Staphylococcus epidermidis and S. aureus, as illustrated by their low BIC-2 values, whereas the activity of toremifene against P. aeruginosa biofilm formation was approximately 10-fold less (Table 1). In conclusion, we demonstrate in vitro activity of toremifene against biofilm formation of different fungal and bacterial pathogens, including Candida and Staphylococcus spp. In view of the inhibitory activity of toremifene against the fungus C. neoformans and the Ebola virus reported previously (17, 28), our data further highlight the broad-spectrum antibiofilm activity of toremifene.

TABLE 1.

Minimal BIC-2 values of toremifene and caspofungin against fungal and bacterial pathogens

| Organism | Reference or source | Mean BIC-2 ± SEM (μM) ofa: |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Tore | CAS | ||

| Candida albicans SC5314 | 46 | 32 ± 3 | 0.22 ± 0.03 |

| Candida albicans CA2 | 23 | 36 ± 2 | ND |

| Candida albicans CA10 | 23 | 85 ± 8 | ND |

| Candida albicans CA15 | 23 | 97 ± 3 | ND |

| Candida glabrata BG2 | 47 | 30 ± 1 | 0.25 ± 0.08 |

| Candida dubliniensis NCPF 3949 | 48 | 23 ± 4 | 0.22 ± 0.05 |

| Candida krusei IHEM 6104 | BCCMb | 26 ± 3 | 0.35 ± 0.11 |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa UCBPP-PA14 | 49 | 46 ± 7 | NA |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis CH | 50 | 3.9 ± 0.3 | NA |

| Staphylococcus aureus SH1000 | 51 | 3.5 ± 0.7 | NA |

BIC-2 values were determined by XTT for Candida spp. and by counting CFU for P. aeruginosa and Staphylococcus spp. n = 3 independent biological replicates. BIC-2, biofilm inhibitory concentration that inhibits biofilm formation 2-fold; Tore, toremifene; CAS, caspofungin; ND, not determined; NA, not applicable.

BCCM, Belgian Coordinated Collections Of Microorganisms/IHEM (Brussels, Belgium).

Next, we translated these in vitro toremifene data against C. albicans and S. aureus to a relevant in vivo rat subcutaneous catheter model (21). Animal experiments were approved by the ethical committee of KU Leuven (project P125/2011) and animals were maintained in accordance with the KU Leuven animal care guidelines. We used a low toremifene dose with reported anticancer activity in rats (29–31), i.e., 3 mg/kg of body weight/day. Several studies used considerably higher doses of toremifene in rodents, ranging from 10 to 2,000 mg/kg/day (32–35). However, due to the limited solubility of toremifene in the vehicle solution (data not shown), 3 mg/kg/day was the highest feasible dose that could be tested in our experimental setup. The experimental setup of the in vivo experiment was similar to those of previously reported studies (36, 37). Briefly, nine catheter fragments, infected with C. albicans SC5314 (5 × 104 cells/ml) or S. aureus SH1000 (1 × 106 cells/ml) by static incubation in RPMI 1640 medium (90 min at 37°C), were implanted on the lower back of immunosuppressed female Sprague-Dawley rats after washing twice with PBS (21). The biofilm burdens on catheters after the adhesion period were measured by obtaining CFU counts from three catheters, showing 1,022 ± 204 adhered C. albicans and 38,000 ± 4,041 adhered S. aureus cells (mean ± SEM) per catheter prior to implantation. Starting at the day of implantation, 1 ml vehicle solution (28.8 g/liter polyethylene glycol 3000, 1.97 g/liter Tween 80, and 8.65 g/liter NaCl) with and without toremifene (0.6 mg/ml in vehicle, or 3 mg/kg/day) was given by oral gavage daily for 7 days. Six (C. albicans experiment) or 4 (S. aureus experiment) rats were treated with toremifene, and 4 rats (both experiments) were treated with the vehicle solution. Afterwards, rats were euthanized and biofilm cells were dissociated from the removed catheters by sonication and vortexing and quantified by counting CFU.

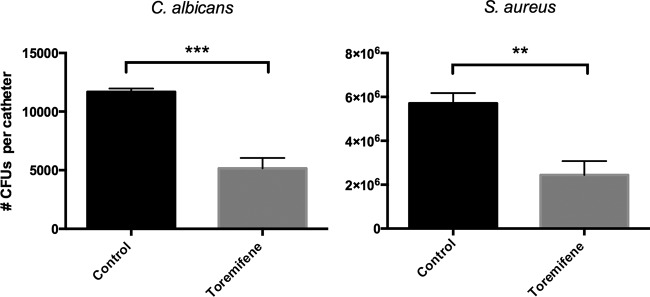

Oral administration of 3 mg/kg/day of toremifene resulted in 56% fewer C. albicans biofilm cells retrieved from the catheter fragments than for the control treatment (5,158 ± 881 CFU versus 11,682 ± 282 CFU for toremifene and the control treatment, respectively; P = 0.0004) (Fig. 1, left). Similarly, oral administration of toremifene resulted in 57% fewer S. aureus biofilm cells retrieved from the catheters than for the control treatment (2,441,701 ± 638,290 CFU versus 5,707,540 ± 468,832 CFU for toremifene and the control treatment, respectively; P = 0.0062) (Fig. 1, right). These data indicate that toremifene (3 mg/kg/day) is active in vivo against C. albicans and S. aureus biofilm formation upon oral administration. The efficacy of 3 mg/kg/day of the reference antifungal agent caspofungin against C. albicans biofilms upon intravenous injection was previously demonstrated in a similar in vivo model (37). Even upon dosing rats at 50 mg/kg caspofungin orally, no caspofungin could be detected in serum because of low oral bioavailability (<1%) (38). Hence, caspofungin can only be applied by intravenous injection.

FIG 1.

In vivo effect of toremifene on C. albicans (left) and S. aureus (right) biofilm formation on subcutaneous implanted catheters in rats. Female Sprague-Dawley immunosuppressed rats were treated for 7 days with toremifene (3 mg/kg of body weight/day; n = 6 and n = 4 rats for the C. albicans and S. aureus experiment, respectively) or vehicle solution (control; n = 4) by oral gavage after subcutaneous implantation of C. albicans- and S. aureus-infected catheters. Biofilm formation on the catheters was evaluated after 7 days by CFU counting. Error bars show SEMs. Unpaired two-tailed Student's t test was used for statistical analysis. ***, P < 0.001; **, P < 0.01.

Note that the minimal dose of toremifene resulting in 50% death (i.e., 50% lethal dose [LD50]) in rats is 3,000 mg/kg (toremifene datasheet sc-253712 [http://datasheets.scbt.com/sc-253712.pdf]; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA), i.e., 1,000-fold higher than the toremifene dose used in this study. The commonly used dose of toremifene in humans for treating ER+ breast cancer is 60 mg daily (16, 39). However, several clinical studies with higher toremifene doses (200 and 240 mg/day) in humans showed no significant increase in toxic side effects compared to the standard dose of 60 mg toremifene daily (40–45). The latter studies confirm that the toremifene dose used in this study (3 mg/kg/day) is achievable in humans. Toremifene (60 to 240 mg daily) is in general well tolerated, and adverse side effects comprise mainly hot flashes, sweating, nausea, vaginal discharge, dizziness, edema, vomiting, and vaginal bleeding. In addition, an elevated risk of thromboembolic events, endometrial cancer (higher for tamoxifen treatment), and a prolongation of the QT interval is noticed in some cases when using ER modulators such as tamoxifen and toremifene. Besides these adverse side effects, tamoxifen and toremifene have positive effects on serum lipid levels (decreased cholesterol) and bone mineral density (16, 44, 45).

In conclusion, toremifene is a broad-spectrum antibiofilm compound that prevents C. albicans and S. aureus biofilm formation in vivo upon oral administration. The good oral bioavailability of toremifene makes toremifene a valuable systemic alternative candidate for treating biofilm-associated fungal and bacterial device infections.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Industrial Research Fund of KU Leuven (postdoctoral grant IOFm/05/022 to K.T. and knowledge platform IOF/KP/11/007), the Interuniversity Attraction Poles Programme initiated by the Belgian Science Policy Office, and the Fund for Scientific Research Flanders (FWO G.0804.11 and WO.026.11N). N.D. and S.K. acknowledge the receipt of a predoctoral grant from IWT-Vlaanderen (IWT101095) and a postdoctoral grant from FWO, respectively.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 6 October 2014

REFERENCES

- 1.Costerton JW, Montanaro L, Arciola CR. 2005. Biofilm in implant infections: its production and regulation. Int. J. Artif. Organs 28:1062–1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ramage G, Robertson SN, Williams C. 2014. Strength in numbers: antifungal strategies against fungal biofilms. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 43:114–120. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2013.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walz JM, Memtsoudis SG, Heard SO. 2010. Prevention of central venous catheter bloodstream infections. J. Intensive Care Med. 25:131–138. 10.1177/0885066609358952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cornely OA, Bassetti M, Calandra T, Garbino J, Kullberg BJ, Lortholary O, Meersseman W, Akova M, Arendrup MC, Arikan-Akdagli S, Bille J, Castagnola E, Cuenca-Estrella M, Donnelly JP, Groll AH, Herbrecht R, Hope WW, Jensen HE, Lass-Florl C, Petrikkos G, Richardson MD, Roilides E, Verweij PE, Viscoli C, Ullmann AJ, ESCMID Fungal Infection Study Group 2012. ESCMID* guideline for the diagnosis and management of Candida diseases 2012: non-neutropenic adult patients. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 18(Suppl 7):S19–S37. 10.1111/1469-0691.12039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pappas PG, Kauffman CA, Andes D, Benjamin DK, Jr, Calandra TF, Edwards JE, Jr, Filler SG, Fisher JF, Kullberg BJ, Ostrosky-Zeichner L, Reboli AC, Rex JH, Walsh TJ, Sobel JD. 2009. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of candidiasis: 2009 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 48:503–535. 10.1086/596757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Falcone M, Barzaghi N, Carosi G, Grossi P, Minoli L, Ravasio V, Rizzi M, Suter F, Utili R, Viscoli C, Venditti M. 2009. Candida infective endocarditis: report of 15 cases from a prospective multicenter study. Medicine (Baltimore) 88:160–168. 10.1097/MD.0b013e3181a693f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dutronc H, Dauchy FA, Cazanave C, Rougie C, Lafarie-Castet S, Couprie B, Fabre T, Dupon M. 2010. Candida prosthetic infections: case series and literature review. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 42:890–895. 10.3109/00365548.2010.498023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pappas PG, Rex JH, Sobel JD, Filler SG, Dismukes WE, Walsh TJ, Edwards JE. 2004. Guidelines for treatment of candidiasis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 38:161–189. 10.1086/380796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Otto M. 2008. Staphylococcal biofilms. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 322:207–228. 10.1007/978-3-540-75418-3_10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Costerton JW, Stewart PS, Greenberg EP. 1999. Bacterial biofilms: a common cause of persistent infections. Science 284:1318–1322. 10.1126/science.284.5418.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu C, Bayer A, Cosgrove SE, Daum RS, Fridkin SK, Gorwitz RJ, Kaplan SL, Karchmer AW, Levine DP, Murray BE, J Rybak M, Talan DA, Chambers HF, Infectious Diseases Society of America 2011. Clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America for the treatment of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in adults and children. Clin. Infect. Dis. 52:e18–55. 10.1093/cid/ciq146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deresinski S. 2009. Vancomycin in combination with other antibiotics for the treatment of serious methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 49:1072–1079. 10.1086/605572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Janknegt R. 1997. The treatment of staphylococcal infections with special reference to pharmacokinetic, pharmacodynamic and pharmacoeconomic considerations. Pharm. World Sci. 19:133–141. 10.1023/A:1008609718457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schito GC. 2006. The importance of the development of antibiotic resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 12(Suppl 1):S3–S8. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2006.01343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Delattin N, De Brucker K, Vandamme K, Meert E, Marchand A, Chaltin P, Cammue BP, Thevissen K. 2014. Repurposing as a means to increase the activity of amphotericin B and caspofungin against Candida albicans biofilms. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 69:1035–1044. 10.1093/jac/dkt449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taras TL, Wurz GT, Linares GR, DeGregorio MW. 2000. Clinical pharmacokinetics of toremifene. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 39:327–334. 10.2165/00003088-200039050-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Butts A, Koselny K, Chabrier-Rosello Y, Semighini CP, Brown JC, Wang X, Annadurai S, Didone L, Tabroff J, Childers WE, Jr, Abou-Gharbia M, Wellington M, Cardenas ME, Madhani HD, Heitman J, Krysan DJ. 2014. Estrogen receptor antagonists are anti-cryptococcal agents that directly bind EF hand proteins and synergize with fluconazole in vivo. mBio 5(1):e00765–13. 10.1128/mBio.00765-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wiseman H, Cannon M, Arnstein HR, Halliwell B. 1993. Enhancement by tamoxifen of the membrane antioxidant action of the yeast membrane sterol ergosterol: relevance to the antiyeast and anticancer action of tamoxifen. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1181:201–206. 10.1016/0925-4439(93)90021-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parsons AB, Lopez A, Givoni IE, Williams DE, Gray CA, Porter J, Chua G, Sopko R, Brost RL, Ho CH, Wang J, Ketela T, Brenner C, Brill JA, Fernandez GE, Lorenz TC, Payne GS, Ishihara S, Ohya Y, Andrews B, Hughes TR, Frey BJ, Graham TR, Andersen RJ, Boone C. 2006. Exploring the mode-of-action of bioactive compounds by chemical-genetic profiling in yeast. Cell 126:611–625. 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dolan K, Montgomery S, Buchheit B, Didone L, Wellington M, Krysan DJ. 2009. Antifungal activity of tamoxifen: in vitro and in vivo activities and mechanistic characterization. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:3337–3346. 10.1128/AAC.01564-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ricicova M, Kucharikova S, Tournu H, Hendrix J, Bujdakova H, Van Eldere J, Lagrou K, Van Dijck P. 2010. Candida albicans biofilm formation in a new in vivo rat model. Microbiology 156:909–919. 10.1099/mic.0.033530-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Delattin N, De Brucker K, Craik DJ, Cheneval O, Frohlich M, Veber M, Girandon L, Davis TR, Weeks AE, Kumamoto CA, Cos P, Coenye T, De Coninck B, Cammue BP, Thevissen K. 2014. Plant-derived decapeptide OSIP108 interferes with Candida albicans biofilm formation without affecting cell viability. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 58:2647–2656. 10.1128/AAC.01274-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bink A, Vandenbosch D, Coenye T, Nelis H, Cammue BP, Thevissen K. 2011. Superoxide dismutases are involved in Candida albicans biofilm persistence against miconazole. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55:4033–4037. 10.1128/AAC.00280-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lewis K. 2010. Persister cells. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 64:357–372. 10.1146/annurev.micro.112408.134306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kint CI, Verstraeten N, Fauvart M, Michiels J. 2012. New-found fundamentals of bacterial persistence. Trends Microbiol. 20:577–585. 10.1016/j.tim.2012.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.CLSI. 2008. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of yeast, approved standard M27-A3. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harrison JJ, Stremick CA, Turner RJ, Allan ND, Olson ME, Ceri H. 2010. Microtiter susceptibility testing of microbes growing on peg lids: a miniaturized biofilm model for high-throughput screening. Nat. Protoc. 5:1236–1254. 10.1038/nprot.2010.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Johansen LM, Brannan JM, Delos SE, Shoemaker CJ, Stossel A, Lear C, Hoffstrom BG, Dewald LE, Schornberg KL, Scully C, Lehar J, Hensley LE, White JM, Olinger GG. 2013. FDA-approved selective estrogen receptor modulators inhibit Ebola virus infection. Sci. Transl. Med. 5:190ra79. 10.1126/scitranslmed.3005471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kangas L, Paul R, Kellokumpu-Lehtinen P, Harju-Jeanty R, Tuominen J. 1989. Rats with mammary cancer treated with toremifene and interferon: morphometry and needle aspiration biopsy for determination of ATP and 14C-fluorodeoxyglucose content. Res. Exp. Med. (Berl.) 189:113–119. 10.1007/BF01851261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huovinen R, Kellokumpu-Lehtinen PL, Collan Y. 1994. Evaluating the response to antioestrogen toremifene treatment in DMBA induced rat mammary carcinoma. Int. J. Exp. Pathol. 75:257–263. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huovinen RL, Alanen KA, Collan YU. 1995. Cell proliferation in dimethylbenz(A)anthracene(DMBA)-induced rat mammary carcinoma treated with antiestrogen toremifene. Acta Oncol. 34:479–485. 10.3109/02841869509094011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kangas L, Nieminen AL, Blanco G, Gronroos M, Kallio S, Karjalainen A, Perila M, Sodervall M, Toivola R. 1986. A new triphenylethylene compound, Fc-1157a. II. Antitumor effects. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 17:109–113. 10.1007/BF00306737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.di Salle E, Zaccheo T, Ornati G. 1990. Antiestrogenic and antitumor properties of the new triphenylethylene derivative toremifene in the rat. J. Steroid Biochem. 36:203–206. 10.1016/0022-4731(90)90005-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Williams GM, Ross PM, Jeffrey AM, Karlsson S. 1998. Genotoxicity studies with the antiestrogen toremifene. Drug Chem. Toxicol. 21:449–476. 10.3109/01480549809002216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kanaya Y, Doihara H, Shiroma K, Ogasawara Y, Date H. 2008. Effect of combined therapy with the antiestrogen agent toremifene and local hyperthermia on breast cancer cells implanted in nude mice. Surg. Today 38:911–920. 10.1007/s00595-007-3730-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kucharikova S, Tournu H, Holtappels M, Van Dijck P, Lagrou K. 2010. In vivo efficacy of anidulafungin against mature Candida albicans biofilms in a novel rat model of catheter-associated Candidiasis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54:4474–4475. 10.1128/AAC.00697-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bink A, Kucharikova S, Neirinck B, Vleugels J, Van Dijck P, Cammue BP, Thevissen K. 2012. The nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug diclofenac potentiates the in vivo activity of caspofungin against Candida albicans biofilms. J. Infect. Dis. 206:1790–1797. 10.1093/infdis/jis594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sandhu P, Xu X, Bondiskey PJ, Balani SK, Morris ML, Tang YS, Miller AR, Pearson PG. 2004. Disposition of caspofungin, a novel antifungal agent, in mice, rats, rabbits, and monkeys. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:1272–1280. 10.1128/AAC.48.4.1272-1280.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morello KC, Wurz GT, DeGregorio MW. 2003. Pharmacokinetics of selective estrogen receptor modulators. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 42:361–372. 10.2165/00003088-200342040-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gershanovich M, Hayes DF, Ellmen J, Vuorinen J. 1997. High-dose toremifene vs tamoxifen in postmenopausal advanced breast cancer. Oncology (Williston Park) 11(5 Suppl 4):29–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zejnalov RS, Musaev IN, Giyasbejli SR, Dadasheva NR, Gasanzade DA, Yusifov AI, Akhadova NA. 2006. Comparative analysis of the efficacy of toremifeine, tamoxifen and letrozole in treatment of patients with disseminated breast cancer. Onkologiya 8:1–4 (In Russian.) [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gershanovich M, Garin A, Baltina D, Kurvet A, Kangas L, Ellmen J. 1997. A phase III comparison of two toremifene doses to tamoxifen in postmenopausal women with advanced breast cancer. Eastern European Study Group. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 45:251–262. 10.1023/A:1005891506092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hayes DF, Van Zyl JA, Hacking A, Goedhals L, Bezwoda WR, Mailliard JA, Jones SE, Vogel CL, Berris RF, Shemano I. 1995. Randomized comparison of tamoxifen and two separate doses of toremifene in postmenopausal patients with metastatic breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 13:2556–2566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mustonen MV, Pyrhonen S, Kellokumpu-Lehtinen PL. 2014. Toremifene in the treatment of breast cancer. World J. Clin. Oncol. 5:393–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vogel CL, Johnston MA, Capers C, Braccia D. 2014. Toremifene for breast cancer: a review of 20 years of data. Clin. Breast Cancer 14:1–9. 10.1016/j.clbc.2013.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fonzi WA, Irwin MY. 1993. Isogenic strain construction and gene mapping in Candida albicans. Genetics 134:717–728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kaur R, Ma B, Cormack BP. 2007. A family of glycosylphosphatidylinositol-linked aspartyl proteases is required for virulence of Candida glabrata. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:7628–7633. 10.1073/pnas.0611195104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sullivan DJ, Westerneng TJ, Haynes KA, Bennett DE, Coleman DC. 1995. Candida dubliniensis sp. nov.: phenotypic and molecular characterization of a novel species associated with oral candidosis in HIV-infected individuals. Microbiology 141(Pt 7):1507–1521. 10.1099/13500872-141-7-1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee DG, Urbach JM, Wu G, Liberati NT, Feinbaum RL, Miyata S, Diggins LT, He J, Saucier M, Deziel E, Friedman L, Li L, Grills G, Montgomery K, Kucherlapati R, Rahme LG, Ausubel FM. 2006. Genomic analysis reveals that Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence is combinatorial. Genome Biol. 7:R90. 10.1186/gb-2006-7-10-r90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Costerton JW, Marrie TJ, Cheng KJ. 1985. Phenomena of bacterial adhesion, p 3–43 In Savage DC, Fletcher M. (ed), Bacterial adhesion. Springer, New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 51.O'Neill AJ. 2010. Staphylococcus aureus SH1000 and 8325-4: comparative genome sequences of key laboratory strains in staphylococcal research. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 51:358–361. 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2010.02885.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]