Abstract

Dendritic cell (DC)-based cancer immunotherapy is a promising method but so far has demonstrated limited clinical benefits. Regulatory T cells (Treg) represent a major obstacle to cancer immunotherapy approaches. Here we show that inhibiting p38 MAPK during DC differentiation enables DCs to activate tumor-specific effector T cells (Teff), inhibiting the conversion of Treg and compromising Treg inhibitory effects on Teff. Inhibition of p38 MAPK in DCs lowers expression of PPARγ, activating p50 and upregulation of OX40L expression in DCs. OX40L/OX40 interactions between DCs and Teff and/or Treg are critical for priming effective and therapeutic antitumor responses. Similarly, p38 MAPK inhibition also augments the T cell-stimulatory capacity of human monocyte-derived DCs in the presence of Treg. These findings contribute to ongoing efforts to improve DC-based immunotherapy in human cancers.

Introduction

DC-based immunotherapy holds great promise for treating malignancies1. However, the results of most DC-based clinical trials have been disappointing2. In cancer patients, CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells (Treg) accumulate in tumors and secondary lymphoid organs by the mechanisms of expansion of Treg or the conversion of effector T cells (Teff)3, 4. Tumor-associated Treg likely contribute to the suppressive milieu, leading to the suppression of T-cell responses partly via the inhibition of DC functions5. Thus, modulating the suppressive function of Treg is essential for induction of effective antitumor immunity6, 7.

Among the possible strategies to target Treg in vivo, depletion of CD25+ T cells by anti-CD25 antibodies may not be a viable approach because both Treg and activated Teff are depleted, inducing conversion of peripheral precursors into Treg4, 8, 9, 10. A unique surface marker for Treg has not been identified, and an alternative approach to target Treg is the use of cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA4)-blocking antibodies or glucocorticoid-induced TNF receptor (GITR) agonist antibodies to revert Treg-mediated suppression8, 11. However, these strategies can result in over-activating of non-specific T-cell immunity and have been linked to severe autoimmunity in multiple organs, thus limiting their further clinical applications12, 13. Therefore, a more desirable approach is needed to modulate the suppressive function of Treg and activate Teff in an antigen-specific manner.

In an earlier study, we demonstrated that lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced activation of p38 MAPK has a detrimental effect on the generation of immature DCs in vitro14. We and others have also shown that tumor-derived suppressive factors inhibit the differentiation and function of DCs by upregulating p38 MAPK activity in DC precursors in both murine tumor models and cancer patients15, 16, 17, 18. These abnormalities in the phenotype and T-cell stimulatory capacity of DCs could be restored by inhibiting p38 MAPK activity in progenitor cells15, 16, 17, 18. Based on these observations, we hypothesized that p38 MAPK may attenuate antigen presentation and have an essential role in maintenance of self-tolerance in DC.

In this study, we inhibited p38 MAPK activity in DC precursors using the inhibitor SB202190, and inhibitor SB203580 and/or p38α-specific siRNA transfection for confirmation. The inhibition of p38 MAPK results in sharply decreased PPARγ expression in DCs, which reduces functional inhibition of p50 transcriptional activities by PPARγ. In turn, p50 activation upregulates surface expression of OX40L on DCs, increasing their immunostimulatory potency, activatingantigen-specific Teff and inhibiting Treg conversion and function, and facilitating tumor rejection.

RESULTS

Inhibition of p38 MAPK in dendritic cells activate Teff in the presence of Tregs

Among the four different p38 isoenzymes, p38α was the only p38 MAPK isoenzyme detected in the isolated bone marrow (BM) cells and generated immature DCs (iDCs) and mature DCs (mDCs) from wild-type C57BL/6 mice (WT-B6 mice) (Supplementary Fig. 1a). We chose to use SB202190 and SB203580, two specific inhibitors of the α- and β-isoforms of p38 MAPK19. Treatment with 1.5 μM SB202190 or SB203580, but not the inactive analogue SB20247420, was sufficient to inhibit the p38 MAPK activity in BM cells, as determined by our previous studies16, 21 and by the blockage of the phosphorylation of its downstream kinase MAPKAPK-2 (Supplementary Fig. 1b). To examine the role of p38 MAPK in regulating DC generation and maturation (all generated from BM cells from WT-B6 mice unless indicated specifically), flow cytometry was used to analyze the surface expression of various molecules related to antigen presentation. SB202190- and SB203580-treated, but not SB202474-treated iDCs expressed higher levels of DC-related molecules than control iDCs (Supplementary Fig. 1c). After maturation, SB202190-treated mDCs (mSBDCs) and SB203580-treated mDCs (mSB80DCs) showed significantly higher levels of MHC class II, CD80, CD86, CD40 and OX40L than dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO)-treated control mDCs and SB202474-treated mDCs (mSB74DCs) (Fig. 1a–b and Supplementary Fig. 1d). In addition, p38 MAPK inhibition enhanced IL-12 production by mSBDCs and mSB80DCs (Supplementary Fig. 1e). All these cells produced undetectable or very low levels of cytokines such as IL-6, TNF-α, IL-10 and IFN-γ (range from 0 to 50 pg/ml). In line with these results, knockdown of p38α in DC progenitor cells by p38α-specific siRNA during the differentiation also induced the upregulated expression of DC-related surface molecules as compared with non-specific siRNA-treated (Si-non-) mDCs (Supplementary Fig. 2). Collectively, these results suggested that p38 MAPK negatively regulated the generation and immunogenicity of BM–derived DCs (BMDCs).

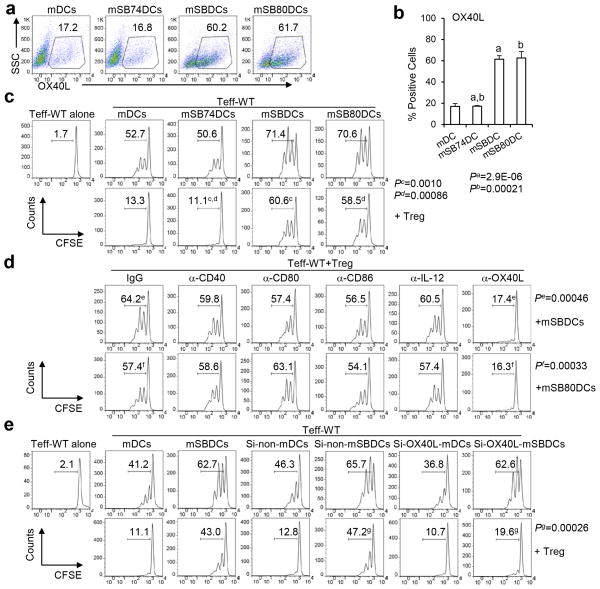

Figure 1.

OX40L expression by mSBDC is critical for mSBDC-induced Teff proliferation in the presence of Treg. (a) Expression of OX40L on treated murine BMDCs. Gates were preset on CD11c+ cells as determined by FACS analysis. Numbers are percentages of OX40L-expressing DCs. (b) Pooled data (n = 3) depicting the percentages of OX40L-positive cells among CD11c+ mDCs, mSB74DCs, mSBDCs and mSB80DCs. Error bars represent s.d. (c–e) Proliferation of CFSE-labeled wild-type (WT) CD4+CD25− Teff (1 × 105) in the absence or presence of unlabeled CD4+CD25+ Treg (1 × 105) induced by various mDCs (1 × 104) plus anti-CD3 antibody (1 μg/ml). Both Teff and Treg were isolated from spleens of naïve C57BL/6 mice. (c) CD4+CD25− Teff were cocultured with mDCs, mSB74DCs, mSBDCs or mSB80DCs. CD4+CD25+ Treg were added as indicated. Sixty hours later, CFSE intensity of Teff was measured by FACS. Numbers indicate percent CFSElo/proliferated Teff. (d) Control IgG or the specific mAbs were added to the coculture of Teff, Treg and mSBDCs or mSB80DCs. Sixty hours later, Teff proliferation was measured by FACS. (e) CD4+CD25− Teff were cocultured with untreated, non-specific siRNA- or OX40L-specific siRNA-treated mDCs or mSBDCs. CD4+CD25+ Treg were added as indicated. Sixty hours later, Teff proliferation was measured by FACS. Representative results from one of three performed experiments are shown. P values were calculated with Student’s t-test.

The enhanced immunogenicity of mSBDCs and mSB80DCs may enable them to promote proliferation of activate Teff in the presence of Treg. We used a carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE)-dilution assay to test the proliferation of Teff. As shown in Fig. 1c and Supplementary Fig. 3, mSBDCs, mSB80DCs or p38α-specific siRNA-treated (Si-p38α-) mDCs induced a profound proliferation of CD4+ Teff in the presence of Treg, whereas the proliferation of CD4+ Teff stimulated by mDCs, mSB74DCs or Si-non-mDCs was largely inhibited. Of note, the proliferation of CD4+ Teff stimulated by mSBDCs or mSB80DCs in the presence of Treg was even stronger than those stimulated by mDCs in the absence of Treg. We found that CD4+ Teff proliferation induced by mSBDCs, mSB80DCs or Si-p38α-mDCs was inhibited significantly by Treg when OX40L-blocking mAb was added (Fig. 1d and Supplementary Fig. 3). We also screened other molecules that might have contributed to this effect by using functional grade blocking mAbs targeting CD80, CD86, CD40 or IL-12 (Supplementary Fig. 1f–h), and excluded their involvement (Fig. 1d). These data suggest that the enhanced stimulatory function of mSBDCs and mSB80DCs is mediated exclusively by upregulated OX40L expression.

Flow cytometry analysis showed that mSBDCs expressed significantly higher levels of surface OX40L, and Teff stimulated by mSBDCs expressed significantly upregulated OX40L than T cells stimulated by mDCs (Supplementary Fig. 4a–b). As Treg do not express OX40L27, we next examined the contribution of cell expression of OX40L. We used OX40L-specific siRNA-treated mSBDCs (Si-OX40L-mSBDCs, Supplementary Fig. 4b), and found that CD4+ Teff proliferation induced by Si-OX40L-mSBDCs was subject to Treg-mediated suppression (Fig. 1e). This Si-OX40L-mSBDC-induced Teff proliferation decreased further to the level of mDC-induced CD4+ Teff proliferation in the presence of Treg when OX40L-blocking antibody was added (Supplementary Fig. 4c), indicating that mSBDC-expressed OX40L played a major role in counteracting Treg-mediated suppression of Teff proliferation, and that Teff-expressed OX40L may also be important. These results suggested that mSBDCs may be able to induce tumor-specific T-cell responses even in the presence of Treg.

OX40 costimulation inhibits Treg and activates Teff

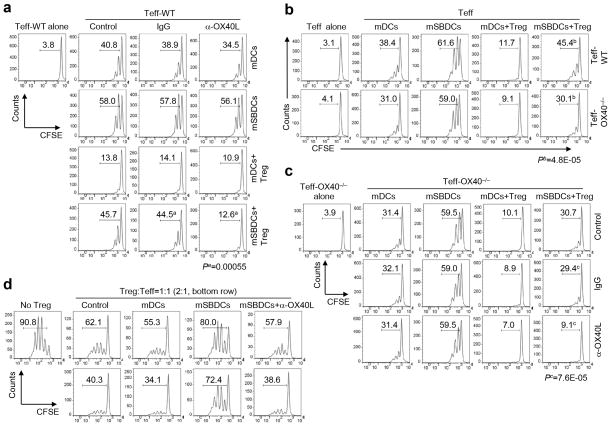

In the absence of Treg, the OX40/OX40L signaling appears to only have a minimal effect on proliferation of CD4+ Teff (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 3). As Treg constitutively express OX40 and activated Teff but not DCs express OX4021, 22, 23, 24, we next determined the contribution of cell expression of OX40 for the activation of Teff by mSBDCs in the presence of Treg. We first examined the role of OX40 expression on Teff. As shown in Fig. 2b, there was only a marginal decrease in the proliferation of OX40−/− CD4+ Teff, as compared with wild-type Teff, in response to mSBDCs or mDCs. However, when Treg were present, the proliferation of the OX40−/− CD4+ Teff stimulated by mSBDCs decreased significantly as compared with those of wild-type Teff, indicating that loss of OX40 on CD4+ Teff rendered them more sensitive to Treg-mediated suppression as compared to their wild-type counterparts when stimulated by mSBDCs. In addition, we also investigated the role of Treg-expressed OX40 in Treg-mediated suppressive function. Since OX40−/− Treg from OX40−/− mice showed impaired suppressive function23, we could not use OX40−/− Treg in our studies. We cocultured mSBDCs, OX40−/− CD4+ Teff, and Treg, in which OX40/OX40L costimulation only occurs between mSBDCs and Treg, and found that the proliferation of OX40−/− CD4+ Teff induced by mSBDCs was significantly inhibited when OX40L-blocking antibody was added (Fig. 2c), suggesting that interaction between mSBDCs and Treg via OX40/OX40L costimulation may lead to reduced inhibitory ability of Treg. Furthermore, mSBDC-pretreated Treg became less effective in inhibiting the proliferation of OT-II Teff compared with control or mDC-pretreated Treg in an OX40L-dependent manner (Fig. 2d). Similar results were also obtained from CD8+ T cells stimulated by mSBDCs in the presence or absence of Treg (Supplementary Fig. 5). Thus, these findings indicate the importance of OX40/OX40L signaling in mSBDC-induced resistance to Treg inhibition of Teff proliferation.

Figure 2.

Role of OX40 signaling in counteracting Treg-mediated suppression by mSBDCs. (a–c) Proliferation of splenic CD4+CD25− Teff in the absence or presence of CD4+CD25+ Treg isolated from naïve C57BL/6 mice. CD4+CD25− Teff (1 × 105) from wild-type C57BL/6 mice (a), wild-type or OX40−/− C57BL/6 mice (b), or OX40−/− C57BL/6 mice (c) were labeled with CFSE and cocultured with mDCs or mSBDCs (1 × 104) plus anti-CD3 antibody (1 μg/ml). Control medium, antibodies and/or unlabeled CD4+CD25+ Treg (1 × 105) were added as indicated. Sixty hours later, CFSE intensity of Teff was measured by FACS. Numbers indicate percent CFSElo/proliferated Teff. Results are representative of three independent experiments. (d) CD4+CD25+ Treg isolated from C57BL/6 mice were pretreated with medium, mDCs, mSBDCs or mSBDCs plus anti-OX40L antibody for 5 hours. CFSE-labeled OT-II Teff (1 × 105) and peptide-pulsed mDCs (1 × 104) were cocultured in the presence of medium or with CD4+CD25+ Treg isolated from the pretreatment condition at the indicated Treg to OT-II Teff ratios. Seventy-two hours later, CFSE intensity of OT-II Teff was examined by FACS. Representative data from one of two repeated experiments are shown. P values were calculated with Student’s t-test.

OX40 costimulation by mSBDCs inhibits Teff conversion to Treg

We found a significantly smaller Treg population (CD4+CD25+Foxp3+) among CD4+ T cells in the lymph nodes of mSBDC-immunized mice as compared to mDC-immunized mice (Fig. 3a), indicating that mSBDCs inhibited the expansion of preexisting Treg and/or conversion of CD4+CD25− Teff to Treg. Since mSBDCs and mDCs had similar stimulatory effects on expansion of Treg (Supplementary Fig. 6a), we hypothesized that mSBDCs may inhibit the conversion of CD4+CD25− Teff to Treg. As shown in Fig. 3b, mSBDCs generated significantly fewer CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Treg than mDCs in vitro cultures of CD4+CD25− Teff without exogenous TGF-β1. Surprisingly, when TGF-β1 induced a large number of Treg from Teff when stimulated with mDCs, mSB74DCs or Si-non-mDCs, mSBDCs, mSB80DCs and Si-p38α-mDCs strongly inhibited the conversion of Teff to Treg (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Fig. 6b–c).

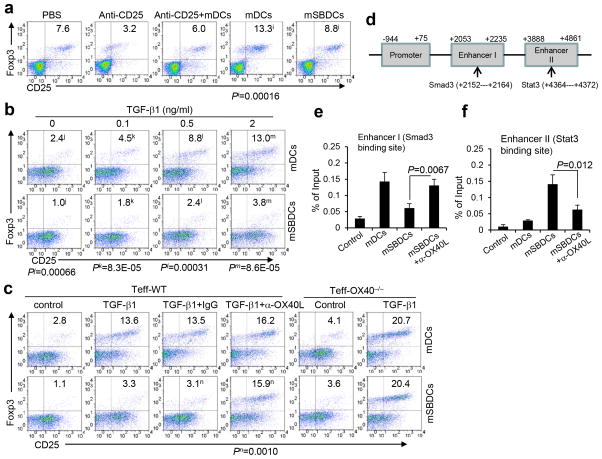

Figure 3.

mSBDCs inhibit Teff-to-Treg conversion by OX40-costimulation. (a) FACS analysis of Treg population in pooled draining lymph nodes 10 days after the second immunization. C57BL/6 mice were immunized twice with 1 × 106 OT-II peptide-loaded mDCs or mSBDCs with or without anti-CD25 antibody treatment. Numbers represent the percentages of CD25+Foxp3+ Treg among gated CD4+ T cells. (b,c) Conversion of Teff into Treg was suppressed by mSBDC stimulation. CD4+CD25−Foxp3− Teff (1 × 105) isolated from wild-type or OX40−/− C57BL/6 mice were cocultured with mDCs or mSBDCs (1 × 104) in the presence of anti-CD3 antibody (1 μg/ml) and IL-2 (20 U/ml) with the addition of varying doses of TGF-β1 (b), or TGF-β1 (2 ng/ml) plus antibodies indicated (c). Numbers indicate the percentages of CD25+Foxp3+ Treg gated on CD4+ T cells in 4-day cultures. (d) Schematic diagram of Smad3 binding site in Foxp3 enhancer I region and Stat3 binding site in Foxp3 enhancer II region. (e–f) CD4+CD25− Teff were cocultured with mDCs or mSBDCs in the presence of TGF-β1 and IL-2 for 4 days. CD4+ T cells were purified for analyses. (e) ChIP assay was performed using Smad3 antibody or control IgG. Precipitated DNA was subjected to RT-PCR using primers targeting enhancer I region. Error bars represent s.d. (n = 3). (f) ChIP assay was performed using Stat3 antibody or control IgG. Precipitated DNA was subjected to RT-PCR using primers targeting enhancer II region. Error bars represent s.d. (n = 3). Data are representative of three (a–c) or two (e–f) independent experiments. P values were calculated with Student’s t-test.

To shed light on the mechanisms driving these effects, we screened IFN-γ, IL-4, IL-12, IL-6, OX40L and other molecules, in mSBDCs for their potential contribution to the inhibition of Teff conversion to Treg7, 25. Our results showed that mAbs blocking OX40L, but not other molecules (Supplementary Fig. 6d), almost completely abrogated the inhibitory effect of mSBDCs on Treg conversion (Fig. 3c), indicating that OX40/OX40L signaling may be involved. In addition, mSBDCs and mDCs had similar ability in conversion of OX40−/− Teff into Treg in the presence or absence of exogenous TGF-β1 (Fig. 3c). Moreover, in vivo blocking OX40/OX40L pathway by injecting OX40L-blocking antibodies restored the generation of Treg population in tumor-draining lymph nodes from mSBDC-immunized mice to the same level of mice immunized with mDCs (Supplementary Fig. 7). To elucidate the mechanism underlying mSBDC-inhibited conversion of Treg, we investigated the binding of phosphorylated (p)Smad3 to the enhancer region I of Foxp3 promoter, in light of a previous study showing that the binding of pSmad3 to the enhancer region I increases Foxp3 transcription whereas the binding of pStat3 to the conserved enhancer region II works as a gene silencer during Foxp3 transcription (Fig. 3d)26. Our results show that, although the level of pSmad3 and pStat3 did not change in CD4+ T cells cocultured with mDCs or mSBDCs in the presence of TGF-β1 (Supplementary Fig. 6e), binding of pSmad3 to the enhancer region I and pStat3 to the enhancer region II were significantly suppressed or enhanced, respectively, in mSBDC-cocultured CD4+ T cells in an OX40L-dependent manner (Fig. 3e and 3f). These results suggest epigenetic inhibition of Treg generation by mSBDCs. Together, these findings show that OX40/OX40L signaling provided by mSBDCs may contribute to the reduced generation of immunosuppressive cells in vitro and in vivo.

Sustained p50 activation mediates OX40L expression in mSBDCs

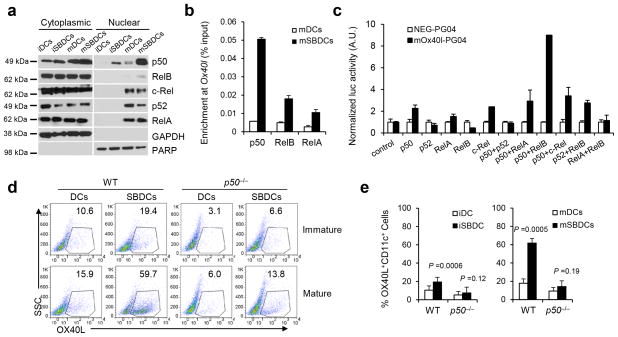

Our results indicate that both enhanced stimulatory function of mSBDCs and the inhibition of Teff conversion into Treg by mSBDCs are mediated exclusively by OX40L. We next elucidated the molecular mechanism underlying p38 inhibition-mediated upregulation of OX40L in mSBDCs. Because NF-κB pathway contributes to the immunogenicity of DCs and Ox40l promoter contains a potential NF-κB binding site (GGGAAATTCA, −84 to −75, upstream of Ox40l), we hypothesized that the NF-κB pathway plays an important role in the increased expression of OX40L on mSBDCs. By comparing NF-κB molecules in the nuclear fractions of mDCs and mSBDCs, we found that inhibition of p38 MAPK resulted in slightly increased nuclear translocation of RelA and RelB and robust nuclear translocation of p50 (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. 8). Similarly, as compared with untreated mDCs and Si-non-mDCs, Si-p38α-mDCs also demonstrated a substantially upregulated nuclear translocation of p50 (Supplementary Fig. 9a). Next, by ChIP assay, we detected an increased physiological binding of RelA, RelB and especially p50 to the Ox40l promoter in mSBDCs (Fig. 4b). To examine whether these NF-κB molecules could activate the Ox40l promoter, we performed luciferase reporter gene assays in HEK 293T cells. RelA, RelB or p52 alone did not activate the Ox40l promoter, whereas p50 together with RelB, and to a lesser extent, with RelA or c-Rel, did (Fig. 4c). Considering that these NF-κB molecules were increased in the nuclear fraction of mSBDCs, these data indicate that nuclear translocation of p50, which formed transcriptionally active complexes with RelA, c-Rel and especially with RelB, were responsible for the upregulation of OX40L expression in mSBDCs.

Figure 4.

Inhibition of p38 MAPK activates p50-dependent pathways that result in increased surface expression of OX40L on mSBDCs. (a) Western blot analysis of the cytoplasmic and nuclear localization of NF-κB molecules in iDCs, mDCs, iSBDCs and mSBDCs. (b) ChIP assay of p50, RelA and RelB binding to the Ox40l promoter in mDCs and mSBDCs. Error bars represent s.d. (n = 3). (c) Luciferase reporter assay showed NF-κB-dependent activation of the Ox40l promoter in HEK 293T cells. HEK293T cells in triplicated wells were transiently transfected with mouse Ox40l promoter-inserted vector mOx40l-PG04 or empty plasmid NEG-PG04, followed by transfection with vectors for NF-κB molecules. Error bars represent s.d. (n = 3). (d) Surface expression of OX40L on iDCs, iSBDCs, mDCs and mSBDCs generated from wild-type and p50−/− C57BL/6 mice analyzed by FACS. Numbers showed the percentage of OX40L-positive DCs gated on CD11c+ cells. (e) Summarized data (n = 4) from (d). Error bars represent s.d. Representative data from one of two repeated experiments are shown. P values were calculated with Student’s t-test.

To further verify the p50-dependent upregulation of surface expression of OX40L on mSBDCs, we generated BMDCs from BM cells of p50−/− B6-mice. The expression of OX40L on p50−/− iDCs and p50−/− mDCs was significantly reduced as compared with those generated from BM cells of WT-B6 mice (Fig. 4d–e). Furthermore, SB202190-treated p50−/− iDCs or p50−/− mDCs failed to upregulate the expression of surface OX40L. The surface OX40L expression level was similar between p50−/− mDCs and p50−/− mSBDCs, confirming a crucial role of p50 in modulating OX40L expression of mSBDCs.

Inhibition of PPARγ contributes to p50 activation in mSBDCs

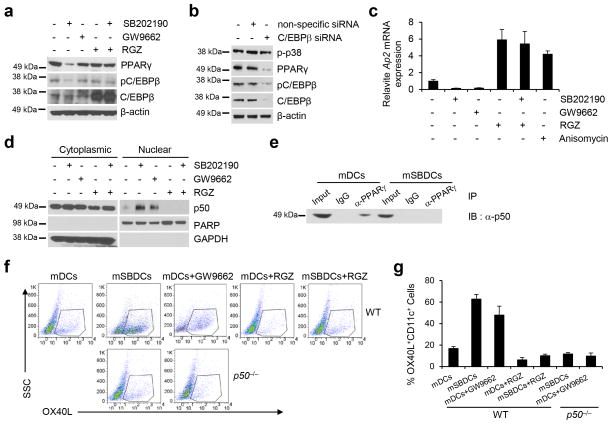

Next we examined the signaling pathways that may lead to activation of p50 following p38 inhibition. As IκB-α did not decrease in mSBDCs (Supplementary Fig. 9b), we performed gene array analysis to investigate the potential molecules that may have contributed to the nuclear translocation of p50. We hypothesized that the decreased PPARγ expression we observed in gene array analysis, may play a role in activating p5027. First, we verified that the protein level of PPARγ was sharply decreased in mSBDCs as compared with mDCs (Fig. 5a and Supplementary Fig. 10) and in Si-p38α-mDCs as compared with Si-non-mDCs (Supplementary Fig. 9c). Also the level of pC/EBPβ, a known downstream target of p38 MAPK28, was reduced in mSBDCs and in Si-p38α-mDCs (Fig. 5a and Supplementary Fig. 9c and 10), which could potentially be responsible for decreased levels of PPARγ, considering it is the master transcriptional factor of PPARγ29. As a confirmation for the observations, knockdown of C/EBPβ by siRNA diminished PPARγ level in mDCs (Fig. 5b and Supplementary Fig. 10).

Figure 5.

Downregulation of PPARγ expression/activity in mSBDCs contributes to the p50-mediated increased expression of surface OX40L. (a) Western blot analysis of the PPARγ, pC/EBPβ and C/EBPβ in mDCs and mSBDCs treated with or without p38 inhibitor SB202190, PPARγ inhibitor GW9662, and/or PPARγ activator RGZ. (b) The protein level of PPARγ, pC/EBPβ and C/EBPβ in mDCs treated with C/EBPβ-specific siRNA. (c) RT-PCR analysis of Ap2 mRNA expression in mDCs treated with or without p38 inhibitor SB202190, PPARγ inhibitor GW9662, PPARγ activator RGZ, and/or p38 activator anisomycin. Data shown (n = 3) were normalized to the Gapdh gene. Error bars represent s.d. (d) Western blot analysis of the cytoplasmic and nuclear localization of p50 molecule in treated mDCs and mSBDCs. (e) Coimmunoprecipitation of endogenous p50 and PPARγ. mDCs and mSBDCs lysates were immunoprecipitated with PPARγ antibody or isotype control IgG and immunoblotted with p50 antibody. (f) Surface expression of OX40L on treated mDCs and mSBDCs generated from wild-type and p50−/− mice analyzed by FACS. Numbers showed the percentage of OX40L-positive DCs gated on CD11c+ cells. (g) Summarized data (n = 4) from (f). Error bars represent s.d. Representative data from one of two performed experiments are shown. P values were calculated with Student’s t-test.

Second, we measured PPARγ activity by detection of mRNA levels of Ap2, which has been described as a direct PPARγ target30. As expected, inhibition of p38 MAPK reduced Ap2 levels in mDCs as well as the PPARγ inhibitor, while both rosiglitazone (RGZ), a PPARγ activator, and the p38 activator, anisomycin31, enhanced Ap2 expression (Fig. 5c). In addition, inhibition of p38 MAPK failed to suppress PPARγ activity directly induced by RGZ (Fig. 5c). By analysis of the nuclear translocation of p50, we found that p50 activity was retroactively correlated with PPARγ activity in mDCs (Fig. 5c–d and Supplementary Fig. 10). Moreover, we detected the presence of p50 in PPARγ immunoprecipitate from mDCs but not from mSBDCs (Fig. 5e and Supplementary Fig. 10), suggesting a possible mechanism of transrepression of p50 activity by PPARγ by complex formation27, which antagonizes p50 signaling in DCs.

Finally, we also found that PPARγ inhibitor-induced p50 activation led to upregulated expression of surface OX40L on mDCs, while p50 deficiency abrogated this effect (Fig. 5f–g). As inhibition of p38 MAPK could not reverse RGZ-mediated PPARγ activation, RGZ-treated mSBDCs failed to express the high levels of OX40L observed on mSBDCs (Fig. 5f–g). These results suggest that inhibition of p38 MAPK suppresses PPARγ expression and activity in mSBDCs by decreasing C/EBPβ phosphorylation, thereby leading to reduced functional inhibition of PPARγ on p50 transcription-factor activity and increased expression of OX40L on mSBDCs.

mSBDCs overcome Treg-mediated immunosuppression in vivo

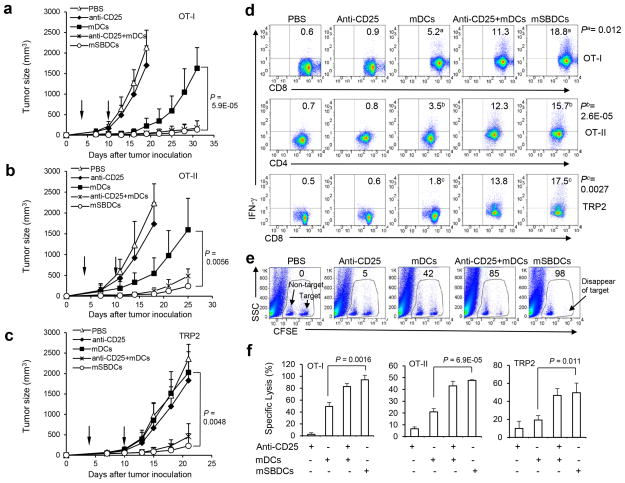

The observed regulatory role of p38 MAPK in DC differentiation and immunogenicity promoted us to examine if p38 inhibited-mDC can induce potent antigen-specific antitumor immunity and facilitate tumor rejection. Similar to other reports of the B16-OVA32 and B1633 tumor model, mice were immunized with OT-I peptide-pulsed mSBDCs (mSBDCs-OT-I), mDCs-OT-I, mSBDCs-OT-II, mDCs-OT-II, mSBDC-TRP2 or mDC-TRP2 at days 3 and 10 after tumor cell inoculation. Groups of mice were depleted of CD25+ Treg with an intraperitoneal injection of CD25-specific antibody or treated with combined Treg-cell depletion (3 days before immunization) and DC immunization. We (Supplementary Fig. 11a) and others34 have found that a single injection of CD25-specific antibody can deplete more than 90% of Treg for a week by examining CD25+Foxp3+ T cells in the spleens. Tumor growth was significantly inhibited by immunization with mSBDCs-OT-I, mSBDCs-OT-II or mSBDC-TRP2, whereas immunization with non-pulsed mSBDCs or Treg depletion had marginal effects, and mDCs-OT-I, mDCs-OT-II or mDC-TRP2 immunization had moderate antitumor effects (Fig. 6a–c and Supplementary Fig. 11b). Of note, mSBDCs immunization alone was at least as effective as the combined treatments of Treg depletion and mDC immunization in inhibiting the growth of pre-established tumor (Fig. 6a–c). In addition, the enhanced antitumor effects of antigen-pulsed mSBDCs were correlated with the significantly higher frequencies of antigen-specific CD4+ or CD8+ IFN-γ-secreting T cells in spleens and the significantly increased CTL activity in immunized mice (Fig. 6d–f, Supplementary Fig. 11c). Importantly, Si-p38α-mDCs-OT-I, mSBDCs-OT-I and mSB80DCs-OT-I, but not the Si-non-mDCs-OT-I, mDCs-OT-I and mSB74DCs-OT-I, could prevent the outgrowth of pre-established B16-OVA tumor (Supplementary Fig. 11d–g), further demonstrating the crucial role of inhibiting p38 MAPK signaling in DCs to induce superior antitumor response after immunization.

Figure 6.

Antitumor activity of DC immunization and Treg depletion using anti-CD25 antibody. (a–c) Comparison of antitumor activity against pre-established tumors. C57BL/6 mice (5 per group) were inoculated subcutaneously with B16-OVA (a,b) or B16 (c) tumor cells (3 × 105) and 3 days later were immunized with 1 × 106 OT-I peptide-loaded (a), OT-II peptide-loaded (b) or TRP2 peptide-loaded (c) mDCs or mSBDCs twice at a weekly interval. Arrows represent the timing of DC-therapy. Anti-CD25 antibodies (50 μg/mouse) were administered intraperitoneally into some groups of mice 3 days before immunization. Error bars represent s.d. Representative results from one of three repeated experiments are shown. (d) IFN-γ ICS of splenocytes from tumor-bearing mice 10 days after second immunization was performed after restimulation with the immunizing peptides overnight in vitro. Numbers represent percentages of IFN-γ secreting lymphocytes gated on CD4+ or CD8+ T cells from one representative experiment of three performed. (e) In vivo CTL assay. CFSElo (left population in gates, non-target) and CFSEhi (right population in gates, target) cells were pulsed with control peptide and OT-I peptide, respectively, and were injected into mice 7 days after OT-I peptide-pulsed DC immunization. Splenocytes were collected 6 hours later for detection of CFSE-labeled cells. Numbers represents percentages of specific killing. Results are representative of one of three independent experiments. (f) Pooled data (n = 3) for in vivo CTL assay. Splenocytes were collected 36 hours later for detection of CFSE-labeled cells in OT-II and TRP2 peptide-loaded DC immunization. Error bars represent s.d. P values were calculated with Student’s t-test.

We also examined the contribution of OX40L signal delivered by mSBDCs in activating T-cell immunity. We found that OX40L antibody treatment could abrogate the proliferation of activated OT-II T cells induced by mSBDC-OT-II in tumor-draining lymph nodes (Supplementary Fig. 12), and substantially reduced the ability of mSBDCs-OT-II and mSBDCs-OT-I to induce tumor regression (Supplementary Fig. 13). Furthermore, p50−/− mSBDCs-OT-I expressed low levels of OX40L and failed to induce an effective antitumor response compared with mSBDCs-OT-I from wild-type mice (Supplementary Fig. 11f). These observations reveal the importance of OX40 costimulation initiated by mSBDCs in inducing antitumor immunity in vivo.

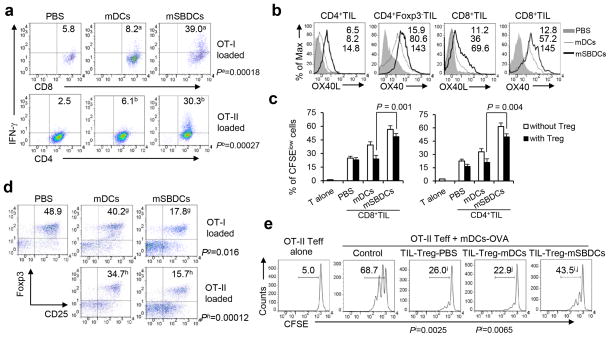

mSBDCs activate antitumor immunity in the effector phase

We then examined the in vivo effects of mSBDCs in the effector phase of antitumor immune response. Tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) were isolated from B16-OVA tumor-bearing C57BL/6 mice receiving different treatments. The numbers of tumor-infiltrating, IFN-γ-secreting CD8+ or CD4+ T cells were significantly increased in mSBDCs-OT-I- or mSBDCs-OT-II-immunized mice, respectively, than the other groups (Fig. 7a). We observed a significantly upregulated expression of OX40 and OX40L on both CD8+ and CD4+ Teff, which might amplify the OX40/OX40L signal on the effector phase of antitumor immune response (Fig. 7b). Tumor-infiltrating CD8+ or CD4+CD25− (Fig. 7c) Teff isolated from mice immunized with mSBDCs-OT-I or mSBDCs-OT-II, respectively, had significantly enhanced proliferation when restimulated in vitro with OT-I or OT-II peptide-loaded mDCs than those from other groups, even in the presence of CD4+CD25+ Treg from naïve mice. We also analyzed tumor-infiltrating CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Treg population, and to our surprise, mSBDCs-OT-I or mSBDCs-OT-II immunization resulted in significantly decreased percentages of Treg in gated CD4+ TILs (Fig. 7d). Moreover, CD4+CD25hi Treg isolated from TILs in mSBDCs-OT-II-immunized mice had significantly decreased suppressive function as compared with those from mDC-immunized or PBS-treated mice in inhibiting the proliferation of CD4+CD25− OT-II cells stimulated with mDCs-OVA (Fig. 7e). In addition, as compared with mSBDCs-OT-I, mSB74DCs-OT-I and p50−/− mSBDCs-OT-I displayed significantly decreased capacity to activate tumor-infiltrating Teff, reduce Treg cell population and compromise the suppressive function of tumor-infiltrating Treg (Supplementary Fig. 14). Taken together, these data indicate that the inhibited p38 MAPK signaling, as well as the subsequently activated p50 NF-κB pathway, are indispensable for mSBDC-stimulated activation of tumor-infiltrating Teff during the effector phase.

Figure 7.

Effects of mSBDCs on TILs. (a) IFN-γ ICS of pooled CD8+ T cells or CD4+ T cells isolated from TILs of mice 10 days after final immunization was performed after overnight in vitro restimulation with OT-I peptide- or OT-II peptide-loaded mDCs. Numbers represent percentages of IFN-γ-secreting lymphocytes gated on CD4+ or CD8+ T cells. (b) Expression (mean fluorescence intensity, MFI) of OX40 and OX40L on CD4+ or CD8+ T cells isolated from TILs of mice immunized with OT-II peptide- or OT-I peptide-loaded mDCs and mSBDCs, respectively. (c) Enhanced proliferation of TILs in the absence or presence of Treg. CFSE-labeled 1 × 105 CD8+ Teff (left) or CD4+CD25− Teff (right) from TILs were cocultured with 1 × 104 OT-I peptide- or OT-II peptide-loaded mDCs, respectively, in the absence or presence of 1 × 105 unlabeled CD4+CD25+ Treg from naïve mice in triplicates. Error bars represent s.d. (n = 3). (d) FACS analysis of the frequency of tumor-infiltrating Treg. Numbers represent the percentages of CD25+Foxp3+ Treg in gated CD4+ T cells. (e) Reduced suppressive activity of tumor-infiltrating Treg. Splenic CD4+CD25− Teff (1 × 105) from OT-II mice were cocultured with 1 × 104 OVA-loaded mDCs in the absence or presence of CD4+CD25+ Treg (1 × 105) from TILs. CFSE intensity of Teff was measured by FACS sixty hours later. Numbers indicate percent CFSElo/proliferated Teff. Representative data from one of two (c–e) or three (a–b) repeated experiments are shown. P values were calculated with Student’s t-test.

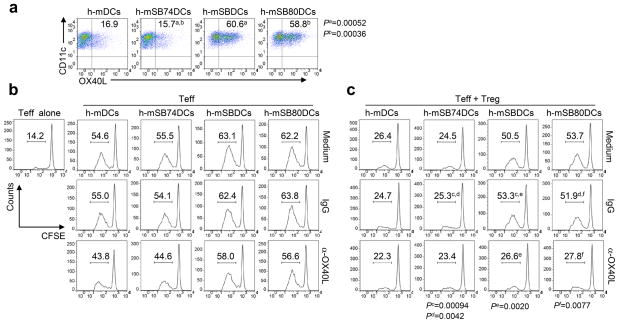

p38 MAPK negatively controls the function of human MoDCs

We further asked if p38 MAPK inhibition could enhance the Teff-stimulatory capacity of human monocyte-derived DCs (h-DCs) in the presence of Treg. Inhibition of p38 MAPK during the differentiation of h-DCs by 1 μM SB202190 or SB203580, but not SB202474 or DMSO, significantly upregulated the surface expression of OX40L on these cells after maturation (Fig. 8a). In the absence of Treg, the OX40/OX40L signaling appears to only have a minimal effect on the proliferation of alloreactive CD4+ Teff induced by p38 MAPK inhibitor-treated h-mDCs (Fig. 8b). Importantly, similar to murine p38 MAPK-inhibited BMDCs, p38 MAPK inhibitor-treated h-mDCs induced a profound proliferation of alloreactive CD4+ Teff in the presence of autologous Treg, whereas the proliferation of CD4+ Teff stimulated by SB202474- or DMSO-treated h-mDCs was largely inhibited (Fig. 8c). OX40-costimulation is crucial to p38 MAPK inhibitor-treated h-mDC-mediated activation of Teff in the presence of Treg, because OX40L blockage abrogated this effect (Fig. 8c). Overall, these results highlight the translational potential of inhibition of p38 MAPK during the differentiation of h-DCs for improving DC-based immunotherapy in human cancers.

Figure 8.

Effects of p38 MAPK inhibition on h-DCs. (a) Expression of OX40L on treated h-mDCs. Inhibitors were added during the differentiation of h-DCs. Numbers are percentages of OX40L-expressing CD11c+ DCs as determined by FACS analysis. (b–c) Proliferation of CFSE-labeled CD4+CD25− Teff (1 × 105) in the absence (b) or presence (c) of unlabeled CD4+CD25+ Treg (1 × 105) induced by various h-mDCs (1 × 104). Teff and Treg were isolated from different donors of peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Treg and h-mDCs were derived from the same donors. Control IgG or anti-OX40L mAbs were added to the coculture. Six days later, CFSE intensity of Teff was measured by FACS. Numbers indicate percent CFSElo/proliferated Teff. Representative results from one of two performed experiments are shown. P values were calculated with Student’s t-test.

DISCUSSION

p38 MAPK activity is required for LPS-, TNF-α- and CD40L-induced maturation of iDCs35, 36. However, the present study shows that p38 MAPK activity in DC progenitor cells acts as an antigen presentation attenuator, and disabling this critical brake during DC differentiation endows DCs with superior activity in antigen presentation and induction of immune responses. Our results further demonstrate the crucial role of inhibition of p38 MAPK activity in DCs in activating CD8+ and CD4+ T cells during both priming and effector phases of the immune response in an antigen-specific manner, possibly owing to the improved maturation status37 of mSBDCs as shown by the significantly enhanced expression of MHC class II, CD80, CD86, CD40 and OX40L as well as IL-12 production. When p38 MAPK signaling in DC progenitor cells was inhibited, the remarkably improved maturation status of mSBDCs was not limited to maturation induced by TNF-α/IL-1β, but could also extend to other stimuli-induced maturation, such as LPS, Poly I:C, CpG, sCD40L and TNF-α/IL-1β/IL-6/PGE2 (Supplementary Fig. 15). Additional inhibition of p38 MAPK during maturation had no obvious effect in improving SBDC maturation status when matured by TNF-α/IL-1β, sCD40L or TNF-α/IL-1β/IL-6/PGE2, but to some extent, suppressed the maturation of SBDCs stimulated by LPS, Poly I:C or CpG (Supplementary Fig. 15), indicating the important role of p38 MAPK in TLR agonist-induced maturation of iSBDCs. Hence, this study provides new insights into an intracellular negative feedback mechanism and indicates that DC generation and activation is self-limiting through p38 MAPK activation in DC progenitor cells.

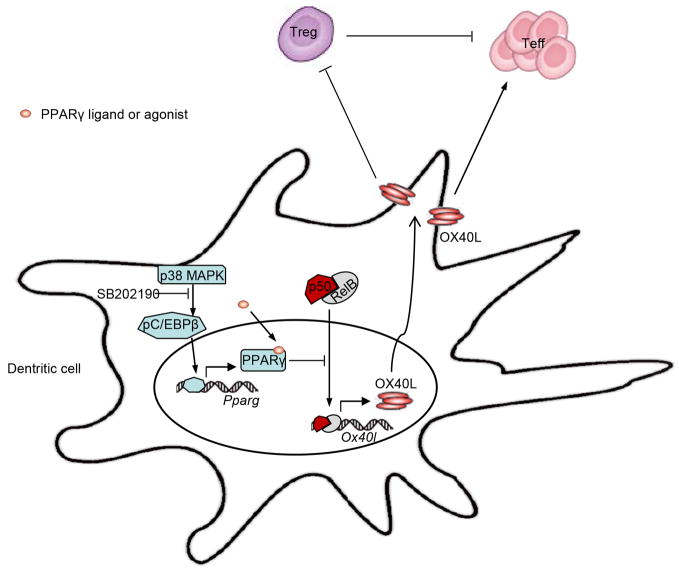

We also found that the self-limiting regulation of DC immunogenicity, controlled by p38 MAPK, is mediated through transcriptional repression of NF-κB family members (Fig. 9). We showed that p38 MAPK phosphorylates C/EBPβ and pC/EBPβ induces the expression of PPARγ, whose activity affects the maturation and function of DCs38, 39. PPARγ has been reported to physically associate with many distinct families of transcription factors, prevent the transcription factors from binding to their response elements and thus suppress their ability to induce gene transcription27. In line with this finding, our results revealed a physical interaction between PPARγ and NF-κB p50, which may repress the transactivation of p50. Inhibition of p38 MAPK in DCs abrogated this self-limiting regulation and resulted in a robust p50 nuclear translocation. This sustained activated p50 forms transcriptionally active complexes with RelA, c-Rel and especially with RelB, which bind the Ox40l promoter and induce the substantially increased expression of surface OX40L on mSBDCs. Our result that p50-deficiency abrogated the enhanced expression of OX40L on mSBDCs further supports this conclusion.

Figure 9.

The role of p38 MAPK signaling in the regulation of DC immunogenicity. p38 MAPK phosphorylates C/EBPβ and pC/EBPβ induces the production of PPARγ, PPARγ can be activated by its ligand or agonist, which can then repress the transactivation of p50 by physical interaction with p50 to prevent its binding to the response elements such as Ox40l promoter. p38 MAPK inhibitor, such as SB202190, could abrogate this self-limitation break and result in a robust p50 nuclear translocation. p50, after forming transcriptionally active complexes with RelB, induces the strikingly increased surface OX40L expression, which is crucial to activation of Teff and inhibition of Treg.

Treg play a major role in tumor-related immune suppression, and have been considered one of the most crucial hurdles to overcome for successful antitumor immunotherapy40. A recent report has shown an attenuated IL-10-secreting Treg induced by TLR agonists through inhibition of p38 MAPK signaling in DCs during maturation, owing to the decreased IL-10 production in DCs stimulated with TLR agonists41. In addition, others also showed that constitutive activation of p38 MAPK is responsible for inducing a tolerogenic profile in DCs during melanoma progression in tumor-bearing mice, with DCs secreting significantly more IL-10 and less IL-1242. Indeed, IL-12 might be down-regulated by p38 MAPK signaling in many different antigen-presenting cells, especially following TLR agonists stimulation41, 42, 43, 44, 45. Our findings differ from these reports because we used cytokine cocktails, not TLR agonists, to mature DCs; the former are more relevant to the cells that are being used in clinical trials. A surprising effect of mSBDCs in inhibiting conversion of Teff to CD4+CD25+Fop3+ Treg has been described in this study. The enhanced OX40/OX40L signals provided by mSBDCs may be responsible for the significantly decreased Treg cell population in the tumor and lymph nodes. In line with these result, several groups have reported that the generation of induced Treg is affected by OX40 costimulation24, 46.

In addition to inhibition of Treg conversion, mSBDCs were more resistant to cancer- and Treg cell-derived suppressive factors (Supplementary Fig. 16). Of note, mSBDCs partially abrogated Treg-mediated immunosuppression by activating CD4+ or CD8+ Teff in the presence of Treg and by inhibiting the suppressive function of Treg, probably via the mechanism of enhanced OX40 signal on both Teff and Treg. Our results show that mSBDCs were as effective as combined treatments of mDC immunization and Treg depletion by anti-CD25 antibodies in controlling the growth of pre-established tumors. Importantly, we also evidenced profound effects of mSBDCs on the effector phase of antitumor immunity, as demonstrated by substantially increased antigen-specific, activated tumor-infiltrating CD4+ or CD8+ Teff which were more resistant to Treg-mediated suppression, and by the reduced suppressive function of tumor-infiltrating Treg which may be a result of the increased OX40 signaling delivered by mSBDCs and/or activated Teff within the tumors. OX40L expression is only observed on cells present at sites of inflammation and not in those invading tumors or on tumor cells themselves, and this insufficient ligation of OX40 could be a limiting factor for immune-mediated destruction of tumor cells47. In support of our findings, OX40L expressed by mDCs has been shown to be important for induction of antitumor immunity48, and other groups also demonstrated that OX40 signaling triggered by agonist antibodies facilitates tumor rejection by blocking the suppression of Treg49. Taken together, in addition to its strong immunostimulatory effects on Teff, mSBDCs can induce efficient antitumor immune responses by counteracting Treg-mediated immune suppression. Hence, mSBDCs should be very useful as a tool for DC-based immunotherapy to induce strong antitumor immune responses in cancer patients.

METHODS

Mice

C57BL/6 mice were purchased from the NCI, and OX40−/− (B6.129S4-Tnfrsf4tm1Nik/J), OT-II (C57BL/6-Tg(TcraTcrb)425Cbn/J), OT-I (C57BL/6-Tg(TcraTcrb)1100Mjb/J) and p50−/− (C57BL/6-129P-Nfkb1tm1Bal/J) mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory. Male, 6–8 week-old mice were used in the beginning of each animal experiment. The studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Cleveland Clinic Foundation.

Cell lines and reagents

The wild-type B16 and B16 transfected with OVA (B16-OVA) melanoma cell lines (ATCC) were cultured in Iscove’s modified dulbecco’s media (IMDM; Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS; Thermo Scientific), 100 U/ml penicillin-streptomycin, and 2 mM L-glutamine (both from Invitrogen). p38 MAPK inhibitor SB202190 and SB203580 and their inactive analogue SB202474 were purchased from EMD Biosciences. Prostaglandin E2 (PGE-2), p38 MAPK activator anisomycin, PPARγ activator rosiglitazone and PPARγ inhibitor GW9662 were purchased from Sigma. MHC class II–restricted TRP1 (SGHNCGTCRPGWRGAACNQKILTVR), H2-Kb–restricted TRP2 (SVYDFFVWL), H2-Kb–restricted OT-I (SIINFEKL), and MHC class II–restricted OT-II (ISQAVHAAHAEINEAGR) peptides were purchased from GenScript. Murine OX40L-blocking antibody (RM134L), CD40-blocking antibody (16-0402), CD80-blocking antibody (16-10A1), CD86-blocking antibody (GL1), IL-12-blocking antibody (C17.8) and anti-CD25 antibody (PC6.1) were purchased from eBioscience. Human OX40L-blocking antibody (159403) was purchased from R&D systems. Mouse or human GM-CSF, TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-4, IL-6, IL-2, sCD40L and human TNF-β1 were purchased from R&D Systems. LPS, CpG, Poly I:C were purchased from InvivoGen.

BMDC generation

Mouse BMDCs were prepared as described previously50. Briefly, BM cells were cultured with 2.5 ml of RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% FBS and mGM-CSF (20 ng/ml). At day 4, 2.5 ml fresh medium containing mGM-CSF (20 ng/ml) was added. At day 7, semi-adherent cells were collected as iDCs. In some cultures, 1.5 μM of SB202190, SB203580 or SB202474 was added to the cultures on day 0, and cultures with addition of DMSO (0.1%; Sigma) served as control. iDCs collected at day 7 were extensively washed and maintained in medium containing mGM-CSF (10 ng/ml) before adding TNF-α (10 ng/ml) and IL-1β (10 ng/ml) to mature the cells. After 48 hours, semi-adherent cells were collected as mDCs. No additional DMSO, SB202190, SB203580 or SB202474 was added during the culture or during maturation. Flow cytometry analysis showed that both iDCs and mDCs contain more than 90% of CD11c+ cells, while mDCs express significantly upregulated surface expression of DC-related molecules than iDCs (Supplementary Fig. 1).

h-MoDC generation

h-MoDCs were generated as described previously51. Monocytes were positively selected from peripheral blood mononuclear cells of healthy donors using anti-CD14-conjugated magnetic microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec). Monocytes were cultured in AIM-V medium supplemented with 50 ng/ml hGM-CSF and hIL-4. In some cultures, 1 μM of SB202190, SB20358052 or SB202474 was added to the cultures on day 0. After 5 days, semi-adherent cells iDCs were extensively washed and then matured for 2 days by adding hTNF-α (10 ng/ml), hIL-1β (10 ng/ml), hIL-6 (10 ng/ml) and 0.5 μg/ml PGE2. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board Committee of Cleveland Clinic Foundation.

Flow cytometric analysis

Cells were stained with FITC, PE, APC-conjugated monoclonal antibodies (mAbs, 1:100 dilution) after pre-blocking FCγ receptors. Rat mAbs specific for mouse CD4 (GK1.5), CD8 (53-6.7), CD25 (PC6.1), CD11c (N418), CD40 (1C10), CD80 (16-10A1), CD86 (GL1), OX40L (RM134L), OX40 (OX86) and matched isotype controls were purchased from eBioscience. Intracellular IFN-γ staining for T cells was performed using a Cytofix/Cytoperm kit (BD Biosciences), with anti-IFN-γ (XMG1.2) antibodies (eBioscience). Before intracellular IFN-γ staining, splenocytes were restimulated by peptides (5 μg/ml) or peptide-loaded mDCs at a 10:1 T cells to DCs ratio overnight, and for the final 6 hours of culture, GolgiPlug (BD Biosciences-Pharmingen) was added. Foxp3 staining was performed using a Foxp3 staining kit (eBioscience) with anti-Foxp3 (FJK-16s) antibodies (eBioscience). For flow cytometric analysis, stained cells were analyzed on a FACSCalibur (Becton Dickinson) and CELLQuest software.

In vivo CTL assay

In vivo CTL assay was performed as described previously53 with some modifications. Spleen cells from C57BL/6 mice were pulsed with 5 μg/ml OT-I peptide, OT-II peptide, TRP1 peptide or TRP2 peptide. Pulsed splenocytes were labeled with CFSE at a final concentration of 1 μM (CFSEhi) or at a final concentration of 0.1 μM (CFSElo). Two cell populations were mixed at 1:1 ratio and 2 × 107 total cells were injected intravenously into treated mice. The percentage of antigen-specific lysis was determined 6 hours later after target cell injection in OT-I peptide-loaded DC-immunized mice (OT-I peptide-pulsed CFSEhi target + TRP2 peptide-pulsed CFSElo non-target), 36 hours later in TRP2 peptide-loaded DC-immunized mice (TRP2 peptide-pulsed CFSEhi target + OT-1 peptide-pulsed CFSElo non-target), and 36 hours later in OT-II peptide-loaded DC-immunized mice (OT-II peptide-pulsed CFSEhi target + TRP1 peptide-pulsed CFSElo non-target), by analyzing the relative proportion of CFSEhi target cells and CFSElo non-target cells in splenocytes, based on CFSE-labeling intensity. The percentage of specific lysis was calculated as follows: [1 − R × M2/M1] × 100, where M1 = non-target events, M2 = target events, R = M1 in untreated mice/M2 in untreated mice.

Isolation of TILs

On different days after DC immunization, mice were sacrificed, and TILs were isolated from tumor-cell suspensions after a Ficoll gradient centrifugation to eliminate dead cells. Subsets of TILs (CD8+, CD4+CD25− and CD4+CD25+ T cells) were sorted with flow cytometer after staining.

ELISA and Western blot

ELISA for IFN-γ and IL-12p70 production was performed by ELISA kits (R&D Systems). For Westernblot, anti-mouse p38α (Cat#9218), p38γ (Cat#2307), p38 (Cat#8690), p-p38 (Cat#4631), MAPKAPK-2 (Cat#3042), pMAPKAPK-2 (Cat#3041), RelA (Cat#4764), RelB (Cat#4954), p52 (Cat#4882), GAPDH (Cat#2118), PARP (Cat#9532), C/EBP-β (Cat#3087), pC/EBP-β (Cat#3084), PPARγ (Cat#2430), pStat3 (Cat#9145), Stat3 (Cat#12640), pSmad3 (Cat#9520), Smad3 (Cat#9523), IκB-α (Cat#4812) and β-actin (Cat#4970) from Cell Signaling (1:1000 dilution), and anti-mouse p38β, (Cat#sc-6187), p38δ,(Cat#sc-7587), p50 (Cat#sc-7178) and c-Rel (Cat#sc-70) from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (1:250 dilution) were used.

T-cell proliferation and suppression assays

Splenic CD8+, CD4+CD25− or CD4+CD25+ T cells from wild-type, OX40−/−, OT-I- or OT-II-transgenic mice were isolated by using the MACS T-cell isolation kits (Miltenyi Biotec). T-cell proliferation was measured with CFSE dilution assay. CD8+ or CD4+CD25− T cells were incubated for 5 minutes at 37 °C with 1 μM CFSE in PBS, and then washed extensively. For antigenic stimulation using TCR-transgenic OT-I or OT-II T cells and antigen-pulsed DCs, 1 × 105 purified T cells and 1 × 104 DCs pulsed with OT-I or OT-II peptides (1 μg/ml) were seeded in each well of a round-bottom 96-well microtiter plate in triplicate in 200 ml RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% FBS. For stimulation using wild-type or OX40−/− T-cells, 1 × 105 purified T cells and 1 × 104 unpulsed DCs were cocultured in the presence of anti-CD3 antibodies (1 μg/ml). For suppression assays, 1–2 × 105 unlabeled CD4+CD25+ Treg were added in the cocultures. Isotype-matched control IgG and blocking mAbs were added at a concentration of 10 μg/ml. We measured proliferation by relative CFSE dilution after 60 hours of culture. For human T cell proliferation, h-MoDCs were mixed with CFSE-labeled alloreactive CD4+CD25− Teff in Aim-V medium, in the presence or absence of autologous CD4+CD25+ Treg. Human T cell proliferation was assessed 6 days after coculture.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

ChIP assay were performed with the ChIP assay kit (Millipore) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Chromatin was extracted from CD4+Foxp3− T cells cocultured for 4 days with mDCs or mSBDCs in the presence of TGF-β1, mDCs and mSBDCs after fixation with formaldehyde. Anti-pSmad3, anti-pStat3, anti-RelA, anti-RelB, anti-p50 and isotype-matched control antibodies (all from Cell Signaling, 1:20 dilution) were used for the immunoprecipitation of chromatin. The precipitated DNA was analyzed by RT-PCR with the following primer sets: surrounding region of NF-κB binding site at Ox40l promoter, 5′-CTTCAGAGCACACGTTTGTGAAT-3′ and 5′-TGAAGGAGCAGAGCAGAGTCTCTT-3′; enhancer I region: 5′-CAGGCTGACCTCAAACTCACAAAG-′3; 5′-CATACCCACACTTTTGACCTCTGC-′3; 5′-GCTTCTGTGTATGGTTTTGTGT-′3; 5′-ATCATCACAGTACATACGAGGA-3′; enhancer II region: 5′-GGACGTCACCTACCACATCC-3′; 5′-CTACCCCACAGGTTTCGTTC-3′; 5′-AGAACTTGGGTTTTGCATGG-3′; 5′-TCTACCCCACAGGTTTCGTT-3′. Values were subtracted with the amount from IgG control and were normalized to corresponding input control.

Luciferase reporter assays

HEK 293T cells were transiently transfected with a 1121-bp mouse Ox40l promoter (Genecopoeia)-inserted luciferase reporter vector pEZX-PG04 (mOx40l-PG40), or control vector (NEG-PG40) and expression vectors for NF-κB molecules (p50, p52, RelA, RelB and c-Rel, Add gene) by Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Promoter activity was measured with Secrete-Pair Dual Luminescence Assay Kit (GeneCopoeia) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Values are expressed as the mean ± S.D. of relative luciferase units normalized to internal control.

DC immunization and tumor models

iDCs, iSBDCs, p50−/− iSBDCs, iSB74DCs, iSB80DCs and si-RNA treated-iDCs were pulsed with OT-I (5 μg/ml), OT-II (15 μg/ml), or TRP2 peptides (30 μg/ml) for 8 hours, and matured for additional 48 hours in the presence of TNF-α and IL-1β. After washing with PBS, mDCs or treated-mDCs were prepared for immunization of mice (5 per group). In the therapeutic model, 3 × 105 B16-OVA or B16 tumor cells were injected subcutaneously into the right flank of wild-type C57BL/6 mice. Mice were then randomly divided into groups and injected with 1 × 106 mDCs or treated-mDCs subcutaneously in the left back 3 and 10 days later. Tumor volumes were measured two or three times per week with an electronic caliper.

Statistical analyses

For statistical analysis, Student’s t-test was used. A P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. In some Figures, the actual P values were shown as superscript numbers. Results are typically presented as means ± s.d.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by startup fund from Cleveland Clinic and grants from the National Cancer Institute (R01 CA138402, R01 CA138398, R01 CA163881, and P50 CA142509), the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society, and Multiple Myeloma Research Foundation.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

Y.L. and Q.Y. initiated the study, designed the experiments and wrote the paper. Y.L. performed the majority of experiments and statistical analyses. M.Z., B.H., S.W. and. H.L. helped with ChIP and Luciferase assay. Y.Z., J.Q., J.H and J.Y. provided critical suggestions to this study. Q.Y. and J.H. contributed to the conceptual idea and to the writing and editing of the paper.

Accession codes

The microarray data were deposited in the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database under accession numbers GSE57879.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Kalinski P, Muthuswamy R, Urban J. Dendritic cells in cancer immunotherapy: vaccines and combination immunotherapies. Expert review of vaccines. 2013;12:285–295. doi: 10.1586/erv.13.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heiro Yi D, Appel S. Current status and future perspectives of dendritic cell-based cancer immunotherapy. Scandinavian journal of immunology. 2013 doi: 10.1111/sji.12060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zou W. Regulatory T cells, tumour immunity and immunotherapy. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:295–307. doi: 10.1038/nri1806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Menetrier-Caux C, Gobert M, Caux C. Differences in tumor regulatory T-cell localization and activation status impact patient outcome. Cancer Res. 2009;69:7895–7898. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zou W. Immunosuppressive networks in the tumour environment and their therapeutic relevance. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:263–274. doi: 10.1038/nrc1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feng LL, Wang X. Targeting Foxp3+ regulatory T cells-related immunosuppression for cancer immunotherapy. Chinese medical journal. 2010;123:3334–3342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Byrne WL, Mills KH, Lederer JA, O’Sullivan GC. Targeting regulatory T cells in cancer. Cancer Res. 2011;71:6915–6920. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shimizu J, Yamazaki S, Takahashi T, Ishida Y, Sakaguchi S. Stimulation of CD25(+)CD4(+) regulatory T cells through GITR breaks immunological self-tolerance. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:135–142. doi: 10.1038/ni759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Piconese S, Valzasina B, Colombo MP. OX40 triggering blocks suppression by regulatory T cells and facilitates tumor rejection. J Exp Med. 2008;205:825–839. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Valzasina B, Piconese S, Guiducci C, Colombo MP. Tumor-induced expansion of regulatory T cells by conversion of CD4+CD25− lymphocytes is thymus and proliferation independent. Cancer Res. 2006;66:4488–4495. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ramirez-Montagut T, et al. Glucocorticoid-induced TNF receptor family related gene activation overcomes tolerance/ignorance to melanoma differentiation antigens and enhances antitumor immunity. J Immunol. 2006;176:6434–6442. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.11.6434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cohen AD, et al. Agonist anti-GITR antibody enhances vaccine-induced CD8(+) T-cell responses and tumor immunity. Cancer Res. 2006;66:4904–4912. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Attia P, et al. Autoimmunity correlates with tumor regression in patients with metastatic melanoma treated with anti-cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2005;23:6043–6053. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.06.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xie J, Qian J, Wang S, Freeman ME, 3rd, Epstein J, Yi Q. Novel and detrimental effects of lipopolysaccharide on in vitro generation of immature dendritic cells: involvement of mitogen-activated protein kinase p38. J Immunol. 2003;171:4792–4800. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.9.4792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang S, et al. Optimizing immunotherapy in multiple myeloma: Restoring the function of patients’ monocyte-derived dendritic cells by inhibiting p38 or activating MEK/ERK MAPK and neutralizing interleukin-6 in progenitor cells. Blood. 2006;108:4071–4077. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-016980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang S, Yang J, Qian J, Wezeman M, Kwak LW, Yi Q. Tumor evasion of the immune system: inhibiting p38 MAPK signaling restores the function of dendritic cells in multiple myeloma. Blood. 2006;107:2432–2439. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-06-2486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oosterhoff D, et al. Tumor-mediated inhibition of human dendritic cell differentiation and function is consistently counteracted by combined p38 MAPK and STAT3 inhibition. Oncoimmunology. 2012;1:649–658. doi: 10.4161/onci.20365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cirone M, et al. Dendritic cell differentiation blocked by primary effusion lymphoma-released factors is partially restored by inhibition of P38 MAPK. International journal of immunopathology and pharmacology. 2010;23:1079–1086. doi: 10.1177/039463201002300412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee JC, et al. A protein kinase involved in the regulation of inflammatory cytokine biosynthesis. Nature. 1994;372:739–746. doi: 10.1038/372739a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tabuchi K, et al. Cochlear protection from acoustic injury by inhibitors of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase and sequestosome 1 stress protein. Neuroscience. 2010;166:665–670. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.12.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Croft M. Control of immunity by the TNFR-related molecule OX40 (CD134) Annu Rev Immunol. 28:57–78. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-030409-101243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Watts TH. TNF/TNFR family members in costimulation of T cell responses. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23:23–68. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.23.021704.115839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takeda I, et al. Distinct roles for the OX40-OX40 ligand interaction in regulatory and nonregulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2004;172:3580–3589. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.6.3580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jensen SM, et al. Signaling through OX40 enhances antitumor immunity. Semin Oncol. 2010;37:524–532. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2010.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.So T, Croft M. Cutting edge: OX40 inhibits TGF-beta- and antigen-driven conversion of naive CD4 T cells into CD25+Foxp3+ T cells. J Immunol. 2007;179:1427–1430. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.3.1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xu L, Kitani A, Stuelten C, McGrady G, Fuss I, Strober W. Positive and negative transcriptional regulation of the Foxp3 gene is mediated by access and binding of the Smad3 protein to enhancer I. Immunity. 2010;33:313–325. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Daynes RA, Jones DC. Emerging roles of PPARs in inflammation and immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:748–759. doi: 10.1038/nri912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Trempolec N, Dave-Coll N, Nebreda AR. SnapShot: p38 MAPK signaling. Cell. 2013;152:656–656. e651. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu Z, Bucher NL, Farmer SR. Induction of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma during the conversion of 3T3 fibroblasts into adipocytes is mediated by C/EBPbeta, C/EBPdelta, and glucocorticoids. Molecular and cellular biology. 1996;16:4128–4136. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.8.4128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Szatmari I, Rajnavolgyi E, Nagy L. PPARgamma, a lipid-activated transcription factor as a regulator of dendritic cell function. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2006;1088:207–218. doi: 10.1196/annals.1366.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.He J, et al. p38 MAPK in myeloma cells regulates osteoclast and osteoblast activity and induces bone destruction. Cancer Res. 2012;72:6393–6402. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Song XT, Evel-Kabler K, Shen L, Rollins L, Huang XF, Chen SY. A20 is an antigen presentation attenuator, and its inhibition overcomes regulatory T cell-mediated suppression. Nat Med. 2008;14:258–265. doi: 10.1038/nm1721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Evel-Kabler K, Song XT, Aldrich M, Huang XF, Chen SY. SOCS1 restricts dendritic cells’ ability to break self tolerance and induce antitumor immunity by regulating IL-12 production and signaling. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:90–100. doi: 10.1172/JCI26169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Prasad SJ, Farrand KJ, Matthews SA, Chang JH, McHugh RS, Ronchese F. Dendritic cells loaded with stressed tumor cells elicit long-lasting protective tumor immunity in mice depleted of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2005;174:90–98. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.1.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arrighi JF, Rebsamen M, Rousset F, Kindler V, Hauser C. A critical role for p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase in the maturation of human blood-derived dendritic cells induced by lipopolysaccharide, TNF-alpha, and contact sensitizers. J Immunol. 2001;166:3837–3845. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.6.3837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yu Q, Kovacs C, Yue FY, Ostrowski MA. The role of the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase, extracellular signal-regulated kinase, and phosphoinositide-3-OH kinase signal transduction pathways in CD40 ligand-induced dendritic cell activation and expansion of virus-specific CD8+ T cell memory responses. J Immunol. 2004;172:6047–6056. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.10.6047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Villadangos JA, Schnorrer P. Intrinsic and cooperative antigen-presenting functions of dendritic-cell subsets in vivo. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:543–555. doi: 10.1038/nri2103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Szatmari I, et al. PPARgamma regulates the function of human dendritic cells primarily by altering lipid metabolism. Blood. 2007;110:3271–3280. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-096222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kock G, Bringmann A, Held SA, Daecke S, Heine A, Brossart P. Regulation of dectin-1-mediated dendritic cell activation by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma ligand troglitazone. Blood. 2011;117:3569–3574. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-08-302224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zitvogel L, Tesniere A, Kroemer G. Cancer despite immunosurveillance: immunoselection and immunosubversion. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:715–727. doi: 10.1038/nri1936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jarnicki AG, et al. Attenuating regulatory T cell induction by TLR agonists through inhibition of p38 MAPK signaling in dendritic cells enhances their efficacy as vaccine adjuvants and cancer immunotherapeutics. J Immunol. 2008;180:3797–3806. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.6.3797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhao F, Falk C, Osen W, Kato M, Schadendorf D, Umansky V. Activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase drives dendritic cells to become tolerogenic in ret transgenic mice spontaneously developing melanoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:4382–4390. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang Z, Zhang X, Darrah PA, Mosser DM. The regulation of Th1 responses by the p38 MAPK. J Immunol. 2010;185:6205–6213. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Franks HA, et al. Novel function for the p38-MK2 signaling pathway in circulating CD1c+ (BDCA-1+) myeloid dendritic cells from healthy donors and advanced cancer patients; inhibition of p38 enhances IL-12 whilst suppressing IL-10. Int J Cancer. 2014;134:575–586. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kuhnol C, Herbarth M, Foll J, Staege MS, Kramm C. CD137 stimulation and p38 MAPK inhibition improve reactivity in an in vitro model of glioblastoma immunotherapy. Cancer immunology, immunotherapy: CII. 2013;62:1797–1809. doi: 10.1007/s00262-013-1484-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vu MD, et al. OX40 costimulation turns off Foxp3+ Tregs. Blood. 2007;110:2501–2510. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-01-070748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gough MJ, Weinberg AD. OX40 (CD134) and OX40L. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2009;647:94–107. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-89520-8_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zaini J, et al. OX40 ligand expressed by DCs costimulates NKT and CD4+ Th cell antitumor immunity in mice. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:3330–3338. doi: 10.1172/JCI32693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Moran AE, Kovacsovics-Bankowski M, Weinberg AD. The TNFRs OX40, 4-1BB, and CD40 as targets for cancer immunotherapy. Current opinion in immunology. 2013;25:230–237. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2013.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hong S, Li H, Qian J, Yang J, Lu Y, Yi Q. Optimizing dendritic cell vaccine for immunotherapy in multiple myeloma: tumour lysates are more potent tumour antigens than idiotype protein to promote anti-tumour immunity. Clinical and experimental immunology. 2012;170:167–177. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2012.04642.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Legler DF, Krause P, Scandella E, Singer E, Groettrup M. Prostaglandin E2 is generally required for human dendritic cell migration and exerts its effect via EP2 and EP4 receptors. J Immunol. 2006;176:966–973. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.2.966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Xie J, Qian J, Yang J, Wang S, Freeman ME, 3rd, Yi Q. Critical roles of Raf/MEK/ERK and PI3K/AKT signaling and inactivation of p38 MAP kinase in the differentiation and survival of monocyte-derived immature dendritic cells. Experimental hematology. 2005;33:564–572. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2005.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Keller AM, Schildknecht A, Xiao Y, van den Broek M, Borst J. Expression of costimulatory ligand CD70 on steady-state dendritic cells breaks CD8+ T cell tolerance and permits effective immunity. Immunity. 2008;29:934–946. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.