Abstract

Ixodes scapularis (Black-legged Tick) has expanded its range in recent decades. To establish baseline data on the abundance of the Black-legged Tick and Borrelia burgdorferi (causative agent of Lyme disease) at the edge of a putative range expansion we collected 1398 ticks from five locations along the Connecticut River in Vermont. Collection locations were approximately evenly distributed between the villages of Ascutney and Guildhall. Relative abundance and distribution by species varied across sites. Black-legged Ticks dominated our collections (n = 1348, 96%), followed by Haemaphysalis leporispalustris (Rabbit Tick, n = 45, 3%) and Dermacentor variabilis (American Dog Tick, n = 5, <1%). Black-legged Tick abundance ranged from 6198 ticks per survey hectare (all life stages combined) at the Thetford site to zero at the Guildhall site. There was little to no overlap of tick species across sites. Phenology of Black-legged Ticks matched published information from other regions of the northeastern USA. Prevalence of B. burgdorferi in adult Black-legged Ticks was 8.9% (n = 112).

Introduction

Evidence indicates that Lyme disease (LD), already the most common vector-borne disease in the United States, is spreading across broad areas of northeastern North America (CDC 2011). While the overall ecology of LD is complex (Ostfeld 2011), two essential players are the causative spirochete bacterium, Borrelia burgdorfi Johnson, Schmid, Hyde, Steigerwalt and Brenner (Johnson et al. 1984), and the principle arthropod vector Ixodes scapularis Say (Black-legged Tick). Since the 1960s the range of the Black-legged Tick has expanded from what are thought to have been relatively small population foci in Wisconsin and coastal New England (Ginsberg 1993). Lyme disease has followed a parallel pattern of expansion.

Environmentally based attempts to control or limit LD have met with mixed and limited success (reviewed by Ostfeld 2011). Additionally, LD treatment is most successful when caught early, but early diagnosis can be problematic because symptoms may mirror other common ailments. Limiting the incidence of LD thus depends on predicting and managing exposure to Black-legged Ticks. This in turn relies on knowledge of both the current status and the ongoing dynamics of tick range limits, tick population densities, and B. burgdorferi infection rates.

Range expansion of the Black-legged Tick may be due to a constellation of non-mutually exclusive factors. These include climate change, reforestation following the abandonment of agriculture, habitat fragmentation and exurban development, reestablishment of Odocoileus virginianus Zimmermann (White-tailed Deer), and variation in local biodiversity (Ostfeld 2011). The relative importance of these factors may vary regionally, and understanding Black-legged Tick population dynamics may require rigorous local data.

Public health information suggests that Vermont may be at the current edge of this putative range expansion. The number of LD cases reported annually in Vermont has increased from 105 to 623 since 2006 (VT Department of Health 2012). Additionally, there is a strong geographical pattern of incidence ranging from >200 cases per 100,000 people in the southwestern corner of the state to near zero in the northeastern corner (VT Department of Health 2012). This suggests that Vermont may be well positioned as a location from which to study additional changes in range of the Black-legged Tick. However, detailed information on the extent and relative abundance of ticks and B. burgdorferi in Vermont is lacking. This study was designed to collect descriptive, baseline data on the prevalence of B. burgdorferi, and the relative abundance, distribution and phenology of ticks in eastern Vermont. We know of no similarly rigorous surveys of ticks and B. burgdorferi in the areas covered by the present study.

Methods

Study site

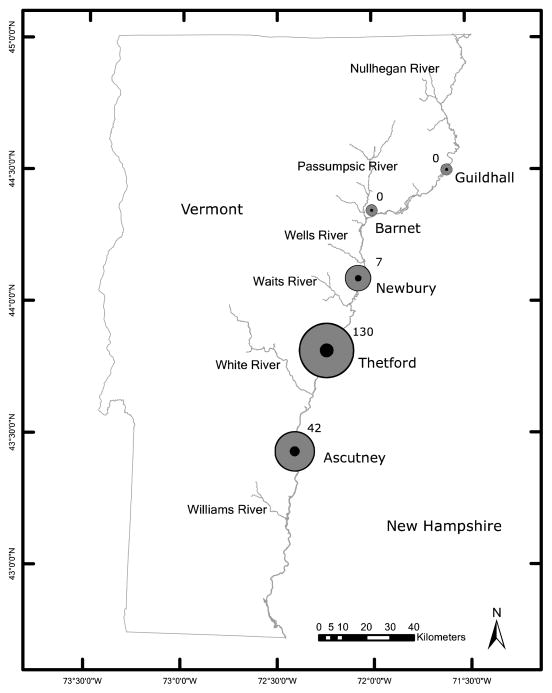

We used traditional maps and digital aerial imagery (GoogleEarth, Google Inc., Mountain View, CA) to identify candidate sampling locations at approximate 30-km intervals along the Vermont side of the Connecticut River from Ascutney in the south to Guildhall in the north (Fig. 1). We selected the Connecticut River Valley because we wanted a north-south transect in Vermont with minimal elevation change between sites. Additionally, anecdotal accounts from long time residents suggested that survey sites along this valley might successfully bracket the current range limit of the Black-legged Tick. In order to maintain consistency across sites we limited selection to areas <5 km from the Connecticut River, with reasonable proximity to a public road, eastern exposure, a diverse forest canopy, >50% deciduous species, and an elevation of 100–300 m. We visited each candidate site and determined exact locations for sampling transects by visual inspection of forest structure. Sampling transects were centered on a single point in mature forest >50 m from the nearest edge (to ensure that the entire sampling space would be in forest cover). We looked for transect locations that would minimize differences in forest structure across all five sites. Site names from south to north (GPS coordinates) are: Ascutney (N43° 26.042′ W072° 24.525′), Thetford (N43° 49.028′ W072° 14.406′), Newbury (N44° 05.572′ W072° 04.417′), Barnet (N44° 20.960′ W072° 00.047), and Guildhall (N44° 30.157′ W071° 36.154′). Forest composition at each site was mixed northern hardwood with variable amounts of American Beech, Balsam Fir, Eastern Hemlock, Red Maple, Red Oak, Sugar Maple, White Ash, White Birch and White Pine. Typical understory vegetation consisted of tree seedlings and saplings with variable amounts of Blueberry, Common Buckthorn, Japanese Barberry, and Tartarian Honeysuckle. Ground cover was a mix of leaf litter, forbs, and ferns.

Figure 1.

Number of adult Black-legged Ticks collected at five locations along the Connecticut River from June 2011–June 2012.

Sampling protocol

We established four 45×1 m sampling transects radiating in the cardinal directions from the center point at each site. We collected ticks by dragging a 1.0×1.5 m panel of white flannel cloth tacked to a wooden dowel at the leading edge, and weighted with a second wooden slat 0.5 m from the trailing edge. Each transect was sampled once per two weeks from June–December 2011, and from March–June 2012. Sampling was conducted during the driest weather window available in each two-week period. Transects were sampled by dragging over vegetation <1.5 m high and around larger vegetation, maintaining as direct a line as possible. We inspected the cloth for ticks at 10 m intervals. Ticks were removed with tweezers and placed in 70% isopropyl alcohol. We identified ticks to species with the assistance of qualified entomologists at the Vermont Department of Forests, Parks and Recreation and the Maine Medical Center.

Borrelia testing

Total DNA was extracted from 112 adult Black-legged Ticks, 49 from Thetford and 63 from Ascutney, using a proprietary extraction protocol (Total Nucleic Acid Extraction Tick or Tissue 002.8, Ibis Biosciences/Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL), previously published in modified form by Crowder et al. (2010). Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) based B. burgdorferi tests were performed at Analytical Services, Inc. (ASI), Williston VT, in accordance with ASI SOP #385, which is based on procedures described by Marconi and Garon (1992) and Mouritsen, et al. (1996). Primers were specific to the outer surface protein A (ospA) gene of B. burgdorferi. Primer sequences were as follows (BERG primers; oligonucleotides obtained from IDTDNA.com): BERG-Forward: TGG ATC TGG AGT ACT TGA AGG CGT and BERG-Reverse: AGT GCC TGA ATT CCA AGC TGC AGT. PCR was performed on a Perkin Elmer 2400 thermocycler and visualized by gel electrophoresis. Samples were divided into paired aliquots, one of which was spiked with B. burgdorferi DNA as a positive control. In the event that the positive control failed, the PCR test was repeated for that sample. The decision to test 112 ticks from two sites was based on a combination of specimen availability and cost considerations.

Statistical analysis

We used summary statistics to describe most aspects of the data. Raw counts were standardized by area surveyed. Area surveyed was obtained by multiplying the number of visits by the area surveyed per visit (typically 0.018 ha, see Results). We used a William’s-corrected G-test for independence between frequencies of Borrelia-positive Black-legged Ticks from Ascutney vs. Thetford (Sokal and Rohlf 2012).

Results

We sampled each location 12–15 times and collected a grand total of 1398 ticks. On two visits to the Thetford site the time required to remove large numbers of larval Blacklegged Ticks from the cloth meant that we only managed to cover half of the full transect distance. Standardization by area surveyed for the Thetford site was adjusted accordingly. Black-legged Ticks dominated our collections (n = 1348, 96%), followed by Haemaphysalis leporispalustris (Rabbit Tick, n = 45, 3%) and Dermacentor variabilis (American Dog Tick, n = 5, <1%). The relative abundance of ticks varied across sites. The abundance of Black-legged Ticks ranged from a minimum estimate of zero ticks per sample hectare (all life stages combined) at the Guildhall site to a maximum of nearly 6200 at the Thetford site (Table 1). Fifty Rabbit Ticks were collected from the Guildhall site, and 5 American Dog Ticks were collected from the Newbury and Barnet sites combined (Table 1).

Table 1.

Number of ticks collected per sample hectare (raw counts in parentheses) at five locations along the Connecticut River from June 2011–June 2012. Sites were sampled 12–15 times and per hectare values are aggregated across all visits. Black-legged = Ixodes scapularis, Rabbit = Haemaphysalis leporispalustris, Am. Dog = Dermacentor variabilis.

| Site | Black-legged | Rabbit | Am. Dog | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adult | Nymph | Larva | Nymph | Larva | Adult | |

| Guildhall | - | - | - | 14 (3) | 194 (42) | - |

| Barnet | - | 5 (1) | - | - | - | 14 (3) |

| Newbury | 26 (7) | 19 (5) | 196 (53) | - | - | 7 (2) |

| Thetford | 657 (130) | 677 (134) | 4864 (963) | - | - | - |

| Ascutney | 179 (42) | 38 (9) | 17 (4) | - | - | - |

Maximum collection rates for adult Black-legged Ticks occurred in March–May, followed by peak collection rates of nymphs in June–July, larva in August, and adults again in September–December. Collection periods overlapped across Black-legged Tick life stages. Adults were collected from March 20–July 19, and again from September 23–December 5. Nymphs were collected from May 21–October 10, and larval from May 21–October 18.

Three of 63 and 7 of 49 adult Blacklegged Ticks tested positive for B. burgdorferi from Ascutney and Thetford, respectively. The combined prevalence of B. burgdorferi was 8.9%. We failed to find evidence of a difference in infection rates between sites (p = 0.09, Gadj = 2.93, df = 1).

Discussion

Our data are the first of their kind for the areas surveyed. They provide preliminary description of current Black-legged Tick abundance and distribution, and they establish a baseline for comparisons with future surveys. Our results revealed a sharp decline in the abundance of Black-legged Ticks north of Newbury near latitude 44°05′. The total number of adult Black-legged Ticks collected at five sites from south to north was: 42, 130, 7, 0 and 0 (Fig. 1). Results for larvae and nymphs followed a similar pattern (Table 1). Interestingly, we collected different tick species at different sites. At the northernmost site, Guildhall, we found only Rabbit Ticks. At the next site south, Barnet, we found mostly American Dog Ticks. In contrast, at the southern three sites, Newbury, Thetford and Ascutney we found nearly 100% Black-legged ticks (Table 1). Also, where Blacklegged Ticks were found they were often in great abundance, while collections of the other two species were always in the single digits per sampling visit (per-visit collection data not shown). Our decision to sample in deciduous forests likely biased our results away from grassland species such as the American Dog Tick (Diuk-Wasser et al. 2006). Nevertheless, these results suggest that our collection sites may have successfully bracketed the current northern extent of the Black-legged Tick range in the Connecticut River Valley, and they support the value of continued collection in these areas.

In a series of recent publications Diuk-Wasser and colleagues (Diuk-Wasser et al. 2012, 2010, 2006) report on a large-scale tick survey that included 304 sample sites, 37 states, and three years of sampling. Four of their sites were in Vermont and New Hampshire at latitudes comparable to our collection sites. Although sampling regimes differed in some ways, the per-visit survey effort between the two studies is roughly comparable. In multiple visits from May–Oct, 2004–2006 the Diuk-Wasser group found no Black-legged Ticks at their three northernmost VT/NH sites, and 16 nymphs at the fourth site.

Our results revealed a different, although not contradictory picture. We visited each of our sites 12–15 times, May–Oct, 2011–2012 and found a grand total of 149 Blacklegged Tick nymphs. While our survey effort during the same months exceeded that of the Diuk-Wasser group by two- to three-fold, we collected nine-fold the number of Black-legged Tick nymphs. Site-specific ecological variation might explain the observed differences in collection rates, and their model classified the areas we surveyed as low to moderate risk areas for LD, with some high risk foci (Diuk-Wasser et al. 2012). If site variation were responsible for the observed differences in collection rates, our data could be interpreted as confirming the predictive power of their model. Another possibility is that Black-legged Tick populations expanded in the years between the two survey efforts. Continued collection will shed light on the effects of local site variation, and on the degree to which Black-legged Ticks may be increasing in abundance and distribution.

Consistent with well-established phenology patterns, we found differences in the timing of peak activity for different Black-legged Tick life stages (Fish 1993). Adult activity peaked in May, dropped off through the bulk of the summer, and peaked again in October. Nymphal activity peaked in June, and larval activity peaked in August. More data will facilitate rigorous phenology comparisons. However, as a preliminary finding our data indicate that phenology patterns from neighboring states are broadly applicable in the areas we surveyed.

Our finding of a 4.7% B. burgdorferi infection rate for Ascutney and 14.1% for Thetford (8.9% for both sites combined) is low compared with the 50% infection rates of hyper-endemic regions such as southern New Hampshire and areas of New York (NH Health Alert Network 2012, NYC Dpt. of Health and Mental Hygiene 2011). While any level of prevalence may be concerning, the current risk of LD in the areas we surveyed appears to be low in relation to some neighboring areas. Previous studies have reported positive correlations between B. burgdorferi prevelance and tick abundance (e.g. Williams et al. 2009). However, the difference that we observed between two of our sites was not significant.

Acknowledgments

Gene Piper, Tom Dubreuil, and the VT State Park System allowed sampling on their land. Trish Hanson, VT Dept. Parks and Rec. and Charles Lubelczyk, Maine Med. Ctr., assisted with tick identification. The Vermont Genetics Network, Ibis Laboratories, Dr. Steven Schutzer U. Medicine and Dentistry NJ, and Kara Pivarski, Norwich U., helped with nucleic acid extraction. Ellen Serra assisted with counting larval ticks. Funding was provided by grants to ARG from the Lyme Disease Association and the Lyndon State College Advanced Study program. Helpful, detailed comments were provided by two anonymous reviewers.

Appendix A. Names of woody plant species

| Common Name

|

Scientific Name

|

Authority

|

|---|---|---|

| Balsam Fir | Abies balsamea | (L.) Mill. |

| Blueberry | Vaccinium angustifolium | Aiton |

| Common Buckthorn | Rhamnus cathartica | L. |

| Eastern Hemlock | Tsuga canadensis | (L.) Carriere |

| Japanese Barberry | Berberis thunbergii | DC. |

| Red Maple | Acer rubrum | L. |

| Sugar Maple | Acer saccharum | Marshall |

| Tartarian Honeysuckle | Lonicera tatarica | L. |

| White Birch | Betula papyrifera | Marshall |

| Eastern White Pine | Pinus strobus | L. |

Literature Cited

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [Accessed May 16, 2012];Lyme disease data. 2011 Available online at http://www.cdc.gov/lyme/stats/index.html.

- Crowder CD, Rounds MA, Phillipson CA, Picuri JM, Matthews HE, Halverson J, Schutzer SE, Ecker DJ, Eshoo MW. Extraction of total nucleic acids from ticks for the detection of bacterial and viral pathogens. Journal of Medical Entomology. 2010;47:89–94. doi: 10.1603/033.047.0112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diuk-Wasser MA, Hoen AG, Cislo P, Brinkerhoff R, Hamer S, Rowland M. Human risk of infection with Borrelia burgdorferi, the Lyme disease agent, in eastern United States. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2012;86(2):320–327. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2012.11-0395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duik-Wasser MA, Vourc’h G, Cislo P, Hoen AG, Melton F, Hamer S. Field and climate based model for predicting the density of host seeking Ixodes scapularis, an important vector of tick-borne disease agents in the eastern United States. Global Ecology and Biogeography. 2010;19:504–514. [Google Scholar]

- Duik-Wasser MA, Cortinas MR, Yaremych-Hamer S, Tsao J, Kitron U. Spateotemporal patterns of host-seeking Ixodes scapularis nymphs (Acari: Ixodidae) in the United States. Journal of Medical Entomology. 2006;43(2):166–176. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585(2006)043[0166:spohis]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fish D. Population ecology of Ixodes dammini. In: Ginsberg HS, editor. Ecology and Environmental Management of Lyme Disease. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press; 1993. pp. 25–42.pp. 224 [Google Scholar]

- Ginsberg HS. Geographic spread of Ixodes dammini and Borrelia burgdorferi. In: Ginsberg HS, editor. Ecology and Environmental Management of Lyme Disease. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press; 1993. pp. 63–82.pp. 224 [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RC, Schmid GP, Hyde FW, Steigerwalt AG, Brenner DJ. Borrelia burgdorferi sp. nov.: Etiologic agent of Lyme disease. International Journal of Systematic Bacteriology. 1984;34:496–497. [Google Scholar]

- Marconi RT, Garon CF. Development of Polymerase Chain Reaction Primer Sets for Diagnosis of Lyme Disease and for Species-Specific Identification of Lyme Disease Isolates by 16S rRNA Signature Nucleotide Analysis. Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 1992;30(11):2830–2834. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.11.2830-2834.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouritsen CL, Wittwer CT, Litwin CM, Yang LM, Weis JJ, Martins TB, Jaskowski TD, Hill HR. Polymerase chain reaction detection of Lyme disease: correlation with clinical manifestations and serologic responses. American Journal of Clinical Pathology. 1996;105:647–654. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/105.5.647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- New Hampshire Health Alert Network. Lyme disease and other tick-borne diseases. 2012 Available online at http://epsomnh.org/Departments/Health/Lyme%20Disease%202012%2005%2024.pdf.

- New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. 2011 DOHMH advisory #10: tick-borne disease advisory. 2011 Available online at http://www.emblemhealth.com/pdf/2011_Tick_Alert_FINAL.pdf.

- Ostfeld RS. Lyme Disease: the Ecology of a Complex System. New York, New York: Oxford University Press; 2011. p. 216. [Google Scholar]

- Sokal RR, Rohlf FJ. Biometry. 4. W.H. Freeman and Company; New York, NY: 2012. p. 937. [Google Scholar]

- VT Department of Health. Lyme Disease Surveillance Report–Vermont 2011. 2012 Available online at http://healthvermont.gov/prevent/lyme/documents/LymeSurveillanceReport2011.pdf.

- Williams SC, Ward JS, Worthley TE, Stafford KC., III Managing Japanese barberry (Ranunculales: Berberidaceae) infestations reduces blacklegged tick (Acari: Ixodidae) abundance and infection prevalence with Borrelia burgdorferi (Spirochaetales: Spirochaetaceae) Environmental Entomology. 2009;38(4):977–84. doi: 10.1603/022.038.0404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]