Abstract

The relationship between cannabis use and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) has received increased scientific scrutiny in recent years. Consistent with this research, studies provide evidence that many individuals with PTSD use cannabis to reduce negative affect and other unpleasant internal experiences associated with PTSD. However, no research to date has explored factors that may be associated with an increased likelihood of cannabis misuse among individuals with PTSD. Consequently, this study explored the moderating role of experiential avoidance (EA; defined as the tendency to engage in strategies to reduce unpleasant private experiences) in the PTSD-cannabis dependence relationship among a sample of 123 Criterion A trauma-exposed patients in residential substance abuse treatment. Moderation analyses indicated an interactive effect of PTSD symptom severity and EA on current cannabis dependence. Specifically, results revealed a conditional effect of PTSD symptom severity on cannabis dependence only when EA was average or higher, with higher levels of PTSD symptom severity associated with a greater risk of cannabis dependence. These findings are consistent with evidence that cannabis use may serve an avoidant function among some individuals with PTSD and suggest that acceptance-based behavioral approaches might be effective in targeting both cannabis use and PTSD-related impairment.

Keywords: cannabis misuse, comorbidity, emotion regulation; marijuana dependence, substance use disorders, trauma

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is characterized by the presence of re-experiencing, avoidance, negative alterations in cognition and mood, and hyperarousal symptoms following exposure to a traumatic event (American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013). The symptoms of PTSD can be debilitating, increasing risk for functional impairment across multiple domains (Rodriguez, Holowka, & Marx, 2012) and the development of other psychiatric disorders (Kessler, Sonnega, Bromet, Hughes, & Nelson, 1995), particularly substance use disorders (SUD; Chilcoat & Menard, 2003). Although most studies exploring the relation between PTSD and substance use have focused on alcohol or cocaine use (e.g., Coffey, Schumacher, Brady, & Cotton, 2007; Jakupcak et al., 2010; Waldrop, Back, Verduin, & Brady, 2007), there is an emerging body of literature exploring the connection between PTSD and cannabis use (the most commonly used illicit substance in the United States and worldwide; SAMHSA, 2012; UNODC, 2012).

This body of research has demonstrated that PTSD is associated with increased risk for cannabis use. In a large subsample of the National Comorbidity Survey, lifetime PTSD symptoms were uniquely associated with increased rates of lifetime cannabis use, past year cannabis use, and past year daily cannabis use (Cougle, Bonn-Miller, Vujanovic, Zvolensky, & Hawkins, 2011). Furthermore, the relation between PTSD and cannabis use is clinically relevant. For example, among a sample of Veterans with PTSD, Bonn-Miller, Boden, Vujanovic, and Drescher (2013) found that a pretreatment diagnosis of a cannabis use disorder was associated with weaker response to residential PTSD treatment, even when taking into account other relevant factors (e.g., trauma severity). This research is consistent with extant research on problematic cannabis use in general, which reveals robust associations between cannabis misuse and an array of poor mental and physical health outcomes (Degenhardt, Hall, & Lynskey, 2003; Hall & Degenhardt, 2009; Moore et al., 2007). Given both its relatively high prevalence (compared to other illicit substances) and its demonstrated relations to a number of negative outcomes, additional research aimed at elucidating the relation between cannabis use and PTSD has great public health significance.

Existing literature suggests that cannabis use within the context of PTSD may function to ameliorate negative affect and other distress associated with PTSD symptoms (albeit at the longterm cost of continued experiencing and exacerbation of symptoms; see Boden, Babson, Vujanovic, Short, & Bonn-Miller, 2013; Bonn-Miller et al., 2007, 2010). This literature is consistent with both the negative reinforcement model of substance use (which proposes that the primary motive for substance use is the avoidance of or escape from emotional distress; Baker, Piper, McCarthy, Majeskie, & Fiore, 2004) and research suggesting that individuals with PTSD may use substances to regulate emotional distress (e.g., Tull, McDermott, Gratz, Coffey, & Lejuez, 2011; Waldrop et al., 2007). Cannabis use motives related to reducing negative affect (i.e., coping motives) have been found to be more common in individuals with (vs. without) PTSD (Boden et al., 2013; Bonn-Miller, Babson, & Vandrey, 2014) and positively associated with PTSD symptom severity among individuals exposed to a traumatic event (Bonn-Miller, Vujanovic, Boden, & Gross, 2011; Bonn-Miller et al., 2010). Moreover, higher levels of emotion regulation difficulties and lower levels of non-judgmental acceptance have been found to mediate the relationship between PTSD symptom severity and cannabis use coping motives (Bonn-Miller et al., 2011; Bonn-Miller et al., 2010).

Despite evidence for a robust association between PTSD and cannabis use, not all individuals with PTSD rely on cannabis as a method for regulating distress. Consequently, research is needed to clarify factors that may moderate this association and increase the likelihood of cannabis misuse among individuals with PTSD. One factor that may be central to understanding the relation between PTSD and cannabis misuse is experiential avoidance (EA), defined as efforts to eliminate or alter the frequency, intensity, or other dimensions of unwanted thoughts, feelings, or bodily sensations (Hayes, Wilson, Gifford, Follette, & Strosahl, 1996). Research indicates a robust association between EA and a broad range of psychopathology and distress, including PTSD (Meyer, Morissette, Kimbrel, Kruse, & Gulliver, 2013; see Ruiz, 2010 for a general review). EA has also been found to account for the relationship between social anxiety and coping motives for cannabis use (Buckner, Zvolensky, Farris, & Hogan, 2013). In addition, treatments targeting EA have been found to result in reductions in substance use in general (Hayes et al., 2004; Lanza & Menendez, 2013) and cannabis use in particular (Twohig, Shoenberger, & Hayes, 2007).

The purpose of the current investigation was to explore the role of EA in the relationship between PTSD symptom severity and cannabis dependence within a sample of SUD patients in residential substance abuse treatment – a patient population at high-risk for PTSD, EA, and cannabis dependence (Chen et al., 2011; Gratz, Bornovalova, Delany-Brumsey, Nick, & Lejuez, 2007). To accomplish this aim, a moderation analysis was used to examine whether the relationship between PTSD symptoms and cannabis dependence varies as a function of EA. Given that higher EA is associated with greater unwillingness to experience negative internal events (such as those consistent with PTSD symptoms), it was hypothesized that the relationship between PTSD symptom severity and cannabis use would be strongest when EA is high, and not necessarily present when EA is low.

Methods

Participants

Participants were 123 SUD patients (mean age = 35.72 ± 9.72) reporting at least one Criterion A traumatic event and at least one current symptom of PTSD (see Measures). The most common Criterion A traumatic events were the unexpected death or injury of another (26.8%), sexual assault (24.4%), and physical assault (13.8%). Most participants (84.6%) met current substance dependence criteria for one or more substances and 67.5% met criteria for at least one additional (non-SUD) current psychiatric diagnosis. On average, the most recent period of abstinence from any substance reported by participants was 19 months ago (SD = 28.77), and the number of times participants had received treatment for substance use problems in the past was three (SD = 4.47). Demographic and diagnostic characteristics are presented in Table 1 for both the overall sample and by cannabis dependence classification.

Table 1.

Demographic Variables and Current Disorder Diagnostic Classifications for the Overall Sample and by Cannabis Dependence Classification

| Cannabis Dependence | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Overall N = 123 n (%) |

Present n = 23 n (%) |

Absent n = 100 n (%) |

χ2 (1) |

| Gender | 6.69** | |||

| Male | 61(50%) | 17 (74%) | 44 (44%) | |

| Female | 62 (50%) | 6 (26%) | 56 (56%) | |

| Race/Ethnicity | 0.01 | |||

| White | 70 (57%) | 13 (57%) | 57 (57%) | |

| Non-white | 53 (43%) | 10 (43%) | 43 (43%) | |

| Educational Obtainment | 17.32** | |||

| High school diploma/GED or less | 70 (57%) | 22 (96%) | 48 (48%) | |

| Some college or more | 53 (43%) | 1 (4%) | 52 (52%) | |

| Income | 0.03 | |||

| $9,999 a year or less | 66 (54%) | 12 (52%) | 54 (54%) | |

| $10,000 a year or greater | 57 (46%) | 11 (48%) | 46 (46%) | |

| Occupational Status | 0.10 | |||

| Employed | 29 (24%) | 6 (26%) | 23 (23%) | |

| Unemployed | 94 (76%) | 17 (74% | 77 (77%) | |

| Court-mandated for treatment | 4.52* | |||

| Yes | 41 (33%) | 12 (52%) | 29 (29%) | |

| No | 82 (67%) | 11 (48%) | 71 (71%) | |

| Current psychotropic medication | 3.48 | |||

| Yes | 59 (48%) | 7 (30%) | 52 (52%) | |

| No | 64 (52%) | 16 (70%) | 48 (48%) | |

| Alcohol Dependencea | 1.85 | |||

| Present | 53 (43%) | 7 (30%) | 46 (46%) | |

| Absent | 70 (57%) | 16 (70%) | 54 (54%) | |

| Cocaine Dependencea | 0.67 | |||

| Present | 41 (33%) | 6 (26%) | 35 (35%) | |

| Absent | 82 (67%) | 17 (74%) | 65 (65%) | |

| Major Depressive Disordera | 0.04 | |||

| Present | 30 (24%) | 6 (26%) | 24 (24%) | |

| Absent | 93 (76%) | 17 (74%) | 76 (76%) | |

| Generalized Anxiety Disordera | 0.45 | |||

| Present | 46 (37%) | 10 (44%) | 36 (36%) | |

| Absent | 77 (63%) | 13 (57%) | 64 (64%) | |

| Panic Disordera | 0.19 | |||

| Present | 32 (26%) | 5 (22%) | 27 (27%) | |

| Absent | 91 (74%) | 18 (78%) | 73 (73%) | |

| Posttraumatic Stress Disorderb | 2.40 | |||

| Present | 57 (46%) | 14 (61%) | 43 (43%) | |

| Absent | 66 (54%) | 9 (39%) | 57 (57%) | |

Note: Current Axis I disorders assessed by the SCID-I are reported for all diagnoses with a prevalence of 15% or greater in the study sample. Disorders assessed but not reported above, with sample prevalence in parentheses, include: Social Phobia (14.6%), Stimulant Dependence (13.8%), Opioid Dependence (13.0%), Specific Phobia (13.0%), Bipolar I Disorder (8.1%), Sedative Dependence (7.3%), Dysthymic Disorder (4.9%), Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (4.9%), Polysubstance Dependence (3.3%), Bipolar II disorder (2.4%), Substance-Induced Mood Disorder (2.4%), Substance-Induced Anxiety Disorder (2.4%), and Hallucinogen/Phencyclidine(PCP) Dependence (0.8%).

Current disorder assessed by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID-I);

Current disorder assessed by the Clinician Administered Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Scale (CAPS)

p < .05,

p < .01

Measures

Clinician Administered PTSD Scale

The CAPS (Blake, Weathers, Nagy, & Kaloupek, 1995) is a widely used structured clinical interview for DSM-IV PTSD symptoms and Criterion A traumatic exposure. The CAPS separately assesses the frequency and severity of symptoms on a 4-point rating scale, with higher scores indicating greater frequency/severity. Specifically, frequency items are rated from 0 (never/none/not at all) to 4 (daily or almost every day or more than 80%), and intensity items are rated from 0 (none) to 4 (extreme). A total PTSD symptom severity score was calculated for the current study by summing the frequency and severity ratings of the 17 criterion B–D symptoms (range = 0–136). There is extensive support for the reliability and validity of the CAPS (see Weathers, Keane, & Davidson, 2001). Prior to administering the CAPS, participants complete the Life Events Checklist (LEC; Blake et al., 1995), a self-report instrument developed concurrently with the CAPS that assesses the occurrence of 17 potentially traumatic events.

Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders

The SCID-I (First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 2002) is the gold standard semi-structured assessment instrument for psychiatric disorders. The interview has been found to yield valid and reliable current and lifetime diagnoses across a variety of common psychiatric disorders, including current cannabis dependence. A recent assessment of inter-rater reliability of the SCID-I found evidence of moderate to excellent reliability across major diagnostic categories, including a kappa of .75 across drug abuse/dependence diagnoses (Lobbestael, Leurgans, & Arntz, 2011).

Both the CAPS and SCID-I interviews were conducted by bachelors- or masters-level clinical assessors trained to reliability with the principal investigator (MTT) and co-investigator (KLG). All interviews were reviewed by the principal investigator, with diagnoses confirmed in consensus meetings.

Cannabis withdrawal symptoms

Following completion of the SCID-I, participants were asked to complete a self-report measure assessing 28 withdrawal symptoms associated with the discontinuation of a variety of different substances (e.g., sedatives, alcohol, opioids, cocaine). The severity of each withdrawal symptom was rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely severe). Six of these items were used to create a composite score reflecting the severity of DSM-5 (APA, 2013) current cannabis withdrawal symptoms (e.g., sleep problems, depression, restlessness, nervousness, physical symptoms, etc.). This score was used to evaluate and confirm the absence of current cannabis withdrawal symptoms among participants.

Acceptance and Action Questionnaire

The AAQ (Hayes et al., 2004) is a 9-item measure of EA, with higher scores indicating greater EA. Sample items include “ anxiety is bad,” “when I feel depressed or anxious, I am unable to take care of my responsibilities,” and “I’m not afraid of my feelings [reverse-scored].” Evidence for the construct validity of this measure has been provided, with a single factor solution consistently displaying good model fit across confirmatory factor analyses on independent samples (Hayes, Strosahl, et al., 2004). The AAQ is associated with theoretically-related constructs (e.g., thought suppression; Hayes, Strosahl, et al., 2004; Hayes, Luoma, Bond, Masuda, & Lillis, 2006), as well as behavioral indicators of EA (Gratz, Rosenthal, Tull, Lejuez, & Gunderson, 2006). In the original validation sample, the AAQ was found to have adequate internal consistency (α = .70) and test-retest reliability (r = .64; Hayes, Strosahl, et al., 2004). Internal consistency in the current study was low (α = .47), which is consistent with findings from several recent studies employing this measure in clinical samples (see Bond et al., 2011 for a discussion of this limitation).

Procedure

All procedures were reviewed and approved by the institution’s Institutional Review Board. Data for this study were drawn from a larger study examining emotion-related factors associated with residential substance abuse treatment dropout among SUD patients with and without PTSD (see Tull, Gratz, Coffey, Weiss, & McDermott, 2013). To be eligible for inclusion in the larger study, participants were required to have: 1) obtained a Mini-Mental Status Exam (Folstein, Folstein, & McHugh, 1975) score of ≥ 24; and 2) exhibited no current psychotic disorders (as determined by the SCID-I). Eligible participants were recruited no sooner than 72 hours after entry in the facility (to limit the interference of withdrawal symptoms on study engagement). Those meeting inclusion criteria were provided with information about study procedures and associated risks, following which informed consent was obtained. To be included in the present study, participants needed to report at least one Criterion A traumatic event on the LEC (the CAPS is not completed in the absence of endorsement of a Criterion A traumatic event), and at least one current symptom of PTSD (i.e., a CAPS total PTSD symptom severity score of one or greater). On average, participants took part in the study 8.62 days (range of 3 to 42 days) following treatment entry (SD = 6.41).

Analytic Strategy

Analyses were conducted using SPSS version 22, and PROCESS version 2.10 (Hayes, 2013) was used to test the potential moderating role of experiential avoidance (AAQ) in the relationship between PTSD symptom severity (CAPS) and cannabis dependence. An ANOVA for age and a series of chi-squared tests of independence for other demographic variables were used to identify significant differences between participants with and without a diagnosis of cannabis dependence. Pearson product-moment, point-biserial, and phi correlation coefficients were used to assess relationships between study variables. AAQ and CAPS scores were mean centered prior to analysis to allow for meaningful interpretation of conditional effects. The Johnson-Neyman regions of significance analysis (Johnson & Neyman, 1936) was planned as the primary follow up tool to explore the hypothesized interaction. In addition, the pick-a-point technique (Rogosa, 1980) at the AAQ mean and one standard deviation below and above the mean was planned to provide a visual depiction of the interaction.

Results

Participants reported negligible cannabis withdrawal symptoms (mean item rating = 0.14, SD = .46). Preliminary analyses revealed that participants meeting criteria for cannabis dependence were significantly more likely to be male, of lower educational obtainment, and court-mandated to treatment (ps < .05; see Table 1). Thus, these demographic variables were retained as covariates in the following analyses.

See Table 2 for means, standard deviations, and correlations among study variables. The overall logistic regression model predicting current cannabis dependence using identified covariates, CAPS, AAQ, and AAQ × CAPS as predictors was significant, χ2(6, N = 123) = 41.27, p < .001, Nagelkerke R2 = .46. In addition, the classifications made by the overall model were a good fit to the obtained data, Hosmer & Lemeshow χ2(8) = 2.44, p = .96. Both the conditional effect of PTSD symptom severity (CAPS) and the interactive effect of EA and PTSD symptom severity (AAQ × CAPS) were significant predictors of current cannabis dependence (see Table 3). These findings indicate that EA moderated the relationship between PTSD symptom severity and current cannabis dependence.

Table 2.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations Among Variables

| Variable | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. PTSD Symptoms (CAPS) | 49.61 | 32.56 | -- | .30* | .12 | −.18* | .05 | .08 |

| 2. Experiential Avoidance (AAQ) | 39.61 | 7.66 | -- | -- | −.03 | −.16 | −.10 | −.12 |

| 3. Cannabis Dependence (Yes = 1) | 18.7% dependent | -- | -- | -- | .23** | −.38** | .19* | |

| 4. Gender (Male = 1) | 49.6% male | -- | -- | -- | -- | −.17 | −.05 | |

| 5. Education (≥ Some College = 1) | 43.1% ≥ some college | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | −.13 | |

| 6. Court-mandated (Mandated = 1) | 33.3% mandated | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | |

Note: CAPS = Clinician Administered Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Scale; AAQ = Acceptance and Action Questionnaire; Cannabis Dependence assessed by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV. Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient used for correlations between continuous variable, point-biserial correlation coefficients used for correlations between continuous and dichotomous variables, and phi coefficient used for correlations between dichotomous variables.

p < .05,

p <.01

Table 3.

Conditional and Interaction Effects Estimating Current Cannabis Dependence (Current Dependence = 1)

| ln(odds) | SE | Wald | p | Exp(B) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | −2.531 | 0.667 | 14.41 | <.001 | 0.080 |

| PTSD Symptoms (CAPS) | 0.026 | 0.010 | 6.27 | .012 | 1.026 |

| Experiential Avoidance (AAQ) | −0.052 | 0.042 | 1.54 | .215 | 0.949 |

| CAPS × AAQ | 0.003 | 0.001 | 6.13 | .013 | 1.003 |

| Gender (Male = 1) | 1.754 | 0.677 | 6.71 | .010 | 5.78 |

| Education (≥ some college = 1) | −3.510 | 1.137 | 9.53 | .002 | 0.030 |

| Court-mandated (Mandated = 1) | 0.671 | 0.587 | 1.31 | .253 | 1.955 |

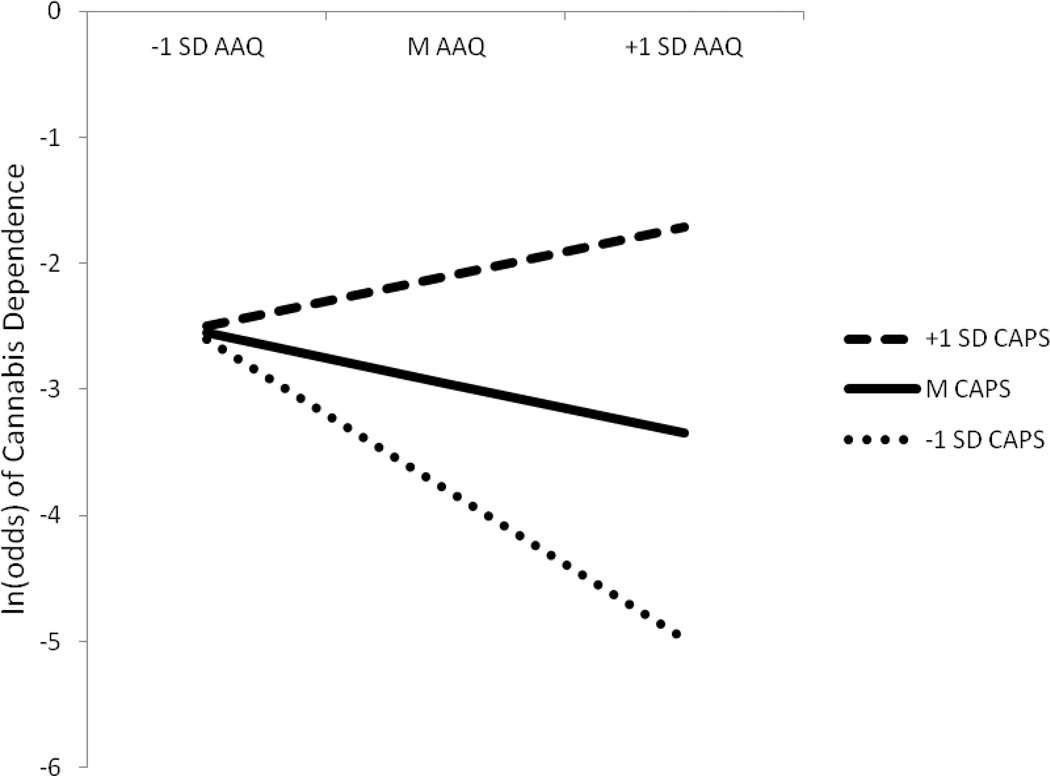

The Johnson-Neyman regions of significance analysis revealed that PTSD symptom severity was significantly associated with current cannabis dependence when AAQ scores were greater than or equal to 37.52 (0.27 standard deviations below the AAQ mean). The pick-a-point follow-up analysis revealed a significant conditional relationship between PTSD symptom severity and current cannabis dependence when AAQ scores were held to one standard deviation above the mean (47.27), B = 0.050, z = 3.072, p = .002, and at the mean (39.61), B = 0.026, z = 2.504, p = .012. The conditional relationship between PTSD symptom severity and current cannabis dependence was non-significant when AAQ scores were held at one standard deviation below the mean (31.95), B = 0.017, z = 0.143, p = .867. Predicted logit values of current cannabis dependence as estimated by the pick-a-point follow-up analysis are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Predicted logit values of current cannabis dependence as a function of scores fixed at the mean, one standard deviation above the mean, and one standard deviation below the mean on the Clinician Administered Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Scale (CAPS) and Acceptance and Action Questionnaire (AAQ), respectively. Covariates in the model included gender, educational obtainment, and court-mandated status. Larger logit values indicate a greater likelihood of current cannabis dependence.

Discussion

Findings from this study provide evidence for the moderating role of EA in the relationship between PTSD symptom severity and cannabis dependence within a sample of patients in residential substance abuse treatment. Consistent with extant theoretical literature, there was a significant relationship between PTSD symptom severity and current cannabis dependence only when EA was average or higher. With regard to the direction of the relationship in the moderated region, high PTSD symptom severity was associated with greater likelihood of cannabis dependence whereas low PTSD symptom severity appeared to be a protective factor for cannabis dependence. These findings are consistent with previous research that has found an association between higher PTSD symptom severity and increased frequency of cannabis use (Bonn-Miller, Vujanovic, & Drescher, 2011).

Negative affect reduction has consistently been found to be a major motive for cannabis use among individuals with PTSD (Bonn-Miller et al., 2007, 2010, 2011, 2014). Findings from this study extend this literature by demonstrating that the tendency to avoid aversive internal experiences interacts with PTSD symptoms to increase the likelihood of cannabis dependence. In particular, increased likelihood of cannabis dependence was found to be conditional on both high severity of PTSD symptoms and average or higher levels of EA, suggesting that it is both the presence of PTSD symptoms and the unwillingness to experience internal states perceived as aversive that relates to problematic cannabis use. Findings that PTSD symptom severity and EA alone were not associated with cannabis dependence in the current sample provide further support that it is the confluence of PTSD symptoms and an unwillingness to experience internal sensations that is essential for understanding the PTSD-cannabis misuse relationship. Results also add to the broader literature on the negative consequences associated with a co-occurring PTSD-SUD diagnosis. Specifically, recent studies have demonstrated that the negative outcomes observed among PTSD-SUD patients may be most prominent among those who exhibit difficulties effectively regulating emotional experiences. For example, Tull et al. (2012) demonstrated that substance abuse treatment non-completion was greatest among male substance dependent patients with PTSD and low distress tolerance. Likewise, Dixon-Gordon, Tull, and Gratz (2014) found that the relationship between PTSD and deliberate self-harm was stronger among substance dependent patients with greater emotion regulation difficulties. Finally, coping drinking motives (i.e., drinking to alleviate negative emotions) has been found to moderate the relationship between PTSD and alcohol consumption, such that, among individuals high (vs. low) on coping drinking motives, increased PTSD symptoms were associated with a greater consumption of alcohol (Simpson, Stappenbeck, Luterek, Lehavot, & Kaysen, 2014).

Although coping motives were not directly assessed in the current study, the obtained findings are suggestive of the function of cannabis misuse within the context of PTSD. Findings from this study suggest that problematic cannabis use may at least partially serve an EA function in the current sample, consistent with past findings linking increased coping (i.e., avoidance) motives for cannabis use to both difficulties in emotion regulation and difficulties in adopting a non-judgmental stance toward experiences (Bonn-Miller et al., 2011; Bonn-Miller et al., 2010). Given that avoidance is also considered to be a core mechanism underlying the maintenance and negative outcomes associated with PTSD (Kashdan, Morina, & Priebe, 2009; Plumb, Orsillo, & Luterek, 2004; Tull, Gratz, Salters, & Roemer, 2004), treatment approaches that target acceptance of or a nonjudgmental stance towards unwanted internal experiences (e.g., Acceptance and Commitment Therapy [Hayes, Stroshal, & Wilson, 2012] or Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction [Grossman, Niemann, Schmidt, & Walach, 2004]) may be effective in reducing problematic cannabis use in individuals with PTSD, as well as PTSD-related functional impairments.

Although promising, it is important to evaluate our findings in the context of limitations present. Most notably, the low internal consistency of the AAQ in the current sample limits the confidence in the measure of EA. Poor reliability of this instrument has been found in numerous other samples and it could be the case that the relatively low level of educational achievement in the current sample (28.5% reported some high school or less) may have contributed to low internal consistency (Bond et al., 2011). Nonetheless, the AAQ has demonstrated clinical and research utility across a variety of samples (see Hayes et al., 2006; Ruiz, 2010) and appears to provide valuable insight in this study despite its poor internal consistency. Future studies should consider employing more psychometrically sound measures of EA, such as the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II (AAQ-II; Bond et al., 2011) or the substance use specific variant of the AAQ (AAQ-SA; Luoma, Drake, Kohlenberg, & Hayes, 2011). Behavioral measures may also hold promise in this regard (e.g., the Computerized Paced Auditory Serial Addition Task; Gratz et al., 2006, 2007). Other limitations include the cross-sectional nature of the data and the lack of direct assessment of cannabis use motives. Future inquiry into this area should consider employing longitudinal designs and measures of cannabis use motives (e.g., the Comprehensive Marijuana Motives Questionnaire; Lee, Neighbors, Hendershot, & Grossbard, 2009, or Marijuana Motives Measure; Simons, Correia, Carey, & Borsari, 1998). Finally, findings require replication in other PTSD populations (e.g., Veterans, civilian outpatient PTSD samples).

Despite limitations, findings highlight the role of EA in the relationship between PTSD symptom severity and cannabis dependence within a high-risk clinical sample. Findings also suggest that it is not simply the presence of PTSD symptoms per se, but the experience of PTSD symptoms in the context of an unwillingness to experience internal sensations perceived as aversive that predicts problematic cannabis use. Consequently, results from this study highlight a particular subset of patients that may be especially at risk for cannabis misuse, as well as a potential target for PTSD-SUD interventions.

Highlights.

Examined moderating role of experiential avoidance (EA) in PTSD-cannabis relation.

PTSD and cannabis dependence associated only when EA was average or higher.

Results support cannabis may be used to reduce negative affect in PTSD.

Results suggest utility of acceptance-based treatment for this population.

Acknowledgments

Preparation of this manuscript was supported in part by R21 DA022383 awarded to the second author (MTT) from the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Michael J. Bordieri, University of Mississippi Medical Center

Matthew T. Tull, University of Mississippi Medical Center.

Michael J. McDermott, University of Mississippi

Kim L. Gratz, University of Mississippi Medical Center

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Baker TB, Piper ME, McCarthy DE, Majeskie MR, Fiore MC. Addiction motivation reformulated: An affective processing model of negative reinforcement. Psychological Review. 2004;111:33–51. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.111.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake DD, Weathers FW, Nagy LM, Kaloupek DG. The development of a clinician-administered PTSD scale. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1995;8:75–90. doi: 10.1007/BF02105408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake DD, Weathers F, Nagy LM, Kaloupek DG, Klauminzer G, Charney DS, Keane TM. A clinician rating scale for assessing current and lifetime PTSD: The CAPS-1. The Behavior Therapist. 1990;13:187–188. [Google Scholar]

- Boden MT, Babson KA, Vujanovic AA, Short NA, Bonn-Miller MO. Posttraumatic stress disorder and cannabis use characteristics among military veterans with cannabis dependence. The American Journal on Addictions. 2013;22:277–284. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2012.12018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond FW, Hayes SC, Baer RA, Carpenter KC, Guenole N, Zettle RD. Preliminary psychometric properties of the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire – II: A revised measure of psychological flexibility and acceptance. Behavior Therapy. 2011;42:676–688. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2011.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonn-Miller MO, Babson KA, Vandrey R. Using cannabis to help you sleep: Heightened frequency of medical cannabis use among those with PTSD. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2014;136:162–165. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonn-Miller MO, Boden MT, Vujanovic AA, Drescher KD. Prospective investigation of the impact of cannabis use disorders on posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms among veterans in residential treatment. Psychological Trauma: Therapy, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2013;5:193–200. [Google Scholar]

- Bonn-Miller MO, Vujanovic AA, Boden MT, Gross JJ. Posttraumatic stress, difficulties in emotion regulation, and coping-oriented marijuana use. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. 2011;40:34–44. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2010.525253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonn-Miller MO, Vujanovic AA, Drescher KD. Cannabis use among military veterans after residential treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2011;25:485–491. doi: 10.1037/a0021945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonn-Miller MO, Vujanovic AA, Feldner MT, Bernstein A, Zvolensky MJ. Posttraumatic stress symptom severity predicts marijuana use coping motives among traumatic event-exposed marijuana users. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2007;20:577–586. doi: 10.1002/jts.20243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonn-Miller MO, Vujanovic AA, Twohig MP, Medina JL, Huggins JL. Posttraumatic stress symptom severity and marijuana use coping motives: A test of the mediating role of non-judgmental acceptance within a trauma-exposed community sample. Mindfulness. 2010;1:98–106. [Google Scholar]

- Buckner JD, Zvolensky MJ, Farris SG, Hogan J. Psychology of Addictive behaviors. Advance online publication; 2013. Social anxiety and coping motives for cannabis use: The impact of experiential avoidance. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen KW, Banducci AN, Guller L, Macatee RJ, Lavelle A, Daughters SB, Lejuez CW. An examination of psychiatric comorbidities as a function of gender and substance type within an inpatient substance use treatment program. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2011;118:92–99. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chilcoat HD, Menard C. Epidemiological investigations: Comorbidity of posttraumatic stress disorder and substance use disorder. In: Ouimette P, Brown PJ, editors. Trauma and substance abuse: Causes, consequences, and treatment of comorbid disorders. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2003. pp. 9–28. [Google Scholar]

- Coffey SF, Schumacher JA, Brady KT, Cotton BD. Changes in PTSD symptomatology during acute and protracted alcohol and cocaine abstinence. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;87:241–248. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cougle JR, Bonn-Miller MO, Vujanovic AA, Zvolensky MJ, Hawkins KA. Posttraumatic stress disorder and cannabis use in a nationally representative sample. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2011;25:554–558. doi: 10.1037/a0023076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degenhardt L, Hall W, Lynskey M. Exploring the association between cannabis use and depression. Addiction. 2003;98:1493–1504. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00437.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon-Gordon KL, Tull MT, Gratz KL. Self-injurious behaviors in posttraumatic stress disorder: An examination of potential moderators. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2014;166:359–367. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.05.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams J. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV-TR axis I disorders, research version, patient edition (SCID-I/P) New York: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini-mental state: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL, Bornovalova MA, Delany-Brumsey A, Nick B, Lejuez CW. A laboratory-based study of the relationship between childhood abuse and experiential avoidance among inner-city substance users: The role of emotional non-acceptance. Behavior Therapy. 2007;38:256–268. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2006.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL, Rosenthal MZ, Tull MT, Lejuez CW, Gunderson JG. An experimental investigation of emotion dysregulation in borderline personality disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2006;115:850–855. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.115.4.850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman P, Niemann L, Schmidt S, Walach H. Mindfulness-based stress reduction and health benefits: A mea-analysis. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2004;57:35–43. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(03)00573-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall W, Degenhardt L. Adverse health effects of non-medical cannabis use. The Lancet. 2009;374:1383–1391. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61037-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York: Guilford Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes SC, Luoma JB, Bond FW, Masuda A, Lillis J. Acceptance and commitment therapy: Model, processes and outcomes. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2006;44:1–25. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes SC, Strosahl K, Wilson KG. Acceptance and commitment therapy: The process and practice of mindful change. 2nd edition. New York: Guilford Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes SC, Strosahl K, Wilson KG, Bissett RT, Pistorello J, McCurry SM. Measuring experiential avoidance: A preliminary test of a working model. The Psychological Record. 2004;54:553–578. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes SC, Wilson KG, Gifford EV, Bissett R, Piasecki M, Gregg J. A preliminary trial of twelve-step facilitation and acceptance and commitment therapy with polysubstance-abusing methadone-maintained opiate addicts. Behavior Therapy. 2004;35:667–688. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes SC, Wilson KG, Gifford EV, Follette VM, Strosahl K. Experiential avoidance and behavioral disorders: A functional dimensional approach to diagnosis and treatment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64:1152–1168. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.6.1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakupcak M, Tull MT, McDermott MJ, Kaysen D, Hunt S, Simpson T. PTSD symptom clusters in relationship to alcohol misuse among Iraq and Afghanistan war veterans seeking post-deployment VA health care. Addictive Behaviors. 2010;35:840–843. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson P, Neyman J. Tests of certain linear hypotheses and their application to some educational problems. Statistical Research Memoirs. 1936;1:57–93. [Google Scholar]

- Kashdan TB, Morina N, Priebe S. Post-traumatic stress disorder, social anxiety disorder, and depression in survivors of the Kosovo War: Experiential avoidance as a contributor to distress and quality of life. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2009;23:185–196. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2008.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes M, Nelson CB. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1995;52:1048–1060. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950240066012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanza PV, Menendez AG. Acceptance and commitment therapy for drug abuse in incarcerated women. Psicothema. 2013;25:307–312. doi: 10.7334/psicothema2012.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CM, Neighbors C, Hendershot CS, Grossbard JR. Development and preliminary validation of a comprehensive marijuana motive questionnaire. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2009;70:279–287. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2009.70.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lobbestael J, Leurgans M, Arntz A. Inter-rater reliability of the structured clinical interview for DSM-IV axis I disorders (SCID I) and axis II disorders (SCID II) Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy. 2011;18:75–79. doi: 10.1002/cpp.693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luoma JB, Drake C, Kohlenberg B, Hayes SC. Substance abuse and psychological flexibility: The development of a new measure. Addiction Research and Theory. 2011;19:3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer EC, Morissette SB, Kimbrel NA, Kruse MI, Gulliver SB. Acceptance and action questionnaire-II scores as a predictor of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms among war veterans. Psychology Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2013;5:521–528. [Google Scholar]

- Moore TH, Zammit S, Lingford-Hughes A, Barnes TR, Jones PB, Lewis G. Cannabis use and risk of psychotic or affective mental health outcomes: A systematic review. The Lancet. 2007;370:319–328. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61162-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plumb JC, Orsillo SM, Luterek JA. A preliminary test of the role of experiential avoidance in post-event functioning. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 2004;35:245–257. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2004.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez P, Holowka DW, Marx BP. Assessment of posttraumatic stress disorder-related functional impairment: a review. Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development. 2012;49:649–665. doi: 10.1682/jrrd.2011.09.0162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogosa D. Comparing nonparallel regression lines. Psychological Bulletin. 1980;88:307–321. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz FJ. A review of acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) empirical evidence: Correlational, experimental psychopathology, component and outcome studies. International Journal of Psychology and Psychological Therapy. 2010;10:125–162. [Google Scholar]

- Simons J, Correia CJ, Carey KB, Borsari BE. Validating a five-factor marijuana motives measure: Relations with use, problems, and alcohol motives. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 1998;45:265–273. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson TL, Stappenbeck CA, Luterek JA, Lehavot K, Kaysen DL. Drinking motives moderate daily relationships between PTSD symptoms and alcohol use. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2014;123:237–247. doi: 10.1037/a0035193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2012 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings. Rockville, MD: 2013. pp. 13–4795. NSDUH Series H-46, HHS Publication No. (SMA) [Google Scholar]

- Tull MT, Gratz KL, Coffey SF, Weiss NH, McDermott MJ. Examining the interactive effect of posttraumatic stress disorder, distress tolerance, and gender on residential substance use disorder treatment retention. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2013;27:763–773. doi: 10.1037/a0029911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tull MT, Gratz KL, Salters K, Roemer L. The role of experiential avoidance in posttraumatic stress symptoms and symptoms of depression, anxiety, and somatization. Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease. 2004;11:754–761. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000144694.30121.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tull MT, McDermott MJ, Gratz KL, Coffey SF, Lejuez CW. Cocaine-related attentional bias following trauma cue exposure among cocaine dependent inpatients with and without posttraumatic stress disorder. Addiction. 2011;106:1810–1818. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03508.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twohig MP, Shoenberger D, Hayes SC. A preliminary investigation of acceptance and commitment therapy as a treatment for marijuana dependence in adults. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2007;40:619–632. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2007.619-632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. World Drug Report 2012. United Nations publication; 2012. Sales No. E.12.XI.1. [Google Scholar]

- Waldrop AE, Back SE, Verduin ML, Brady KT. Triggers for cocaine and alcohol use in the presence and absence of posttraumatic stress disorder. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:634–639. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weathers FW, Keane TM, Davidson JRT. Clinician-administered PTSD scale: A review of the first ten years of research. Depression and Anxiety. 2001;13:132–156. doi: 10.1002/da.1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]