Abstract

Regional body composition changes with aging. Some of the changes in composition are considered major risk factors for developing obesity related chronic diseases which in turn may lead to increased mortality in adults. The role of anthropometry is well recognized in the screening, diagnosis and follow-up of adults for risk classification, regardless of age. Regional body composition is influenced by a number of intrinsic and extrinsic factors. Therapeutic measures recommended to lower cardiovascular disease risk include lifestyle changes. The aim of this review is to systematically summarize studies that assessed the relationships between anthropometry and regional body composition. The potential benefits and limitations of anthropometry for use in clinical practice are presented and suggestions for future research given.

Keywords: anthropometry, body composition, prediction formula

1. Anthropometry as an indicator of nutritional and health status

Prevalence of overweight and obesity is high and increasing worldwide [1, 2]. Recent evidence suggests that both fat and lean mass predict mortality in individuals with and without cardiovascular disease (CVD) [3–5]. This requires knowledge of individual tissue compartments, such as muscle and adipose tissue, and relies on accurate methods of regional body composition (BC) assessment. Since the accepted ‘gold’ standards for regional BC estimation in vivo, such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computer tomography (CT) are difficult to access in routine health care situations, it remains important to use anthropometry in the screening and diagnosis of health and nutritional risk.

The use of BC in medicine is based on its relationship with morbidity and mortality. In the 80’s it was recognized that many chronic and acute illnesses involved alterations in BC, and that these changes might be linked with morbidity and mortality [6]. The vast majority of the associations among BC and morbidity and mortality relate to obesity, a medical condition characterized by the accumulation of excess adipose tissue (AT) or fat [7]. The main impact of these associations tends to be on the cardiovascular system, although the effects on an individual can be modified or compounded by environmental or genetic factors [8]. Meta-analysis reports show that obesity is a risk factor for CVD, type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, some forms of cancer [9–11] and all-cause mortality in adults [12–14]. One of the most important confounding factors profoundly influencing the relationship between obesity and mortality is physical activity [15]. In fact, it has been shown that the mortality risk associated with obesity is offset when cardiovascular fitness is taken into account [16–18].

Fat or lipid, in regard to disease and death, can be viewed in terms of the concentrations of various lipid molecules in the blood, such as total cholesterol, triglycerides and low-density lipoproteins. High concentrations of these circulating blood lipids are significantly associated with cardiovascular disease risk [19] and increased risk of death due to myocardial infarction or stroke [20]. Thus, accurate measurements of BC lead to diagnosis, understanding of disease mechanisms and treatment [21].

In nutrition, accurate measures of BC in subjects with eating disorders are important to monitor the effects of therapeutic interventions on muscle and AT compartments [22]. Only body BC can determine how much muscle and AT are lost or gained as the result of any nutrition, exercise, or pharmaceutical prescription. By measuring BC, a person’s health status can be more accurately assessed and the effects of both dietary and physical activity programs better directed.

Anthropometry and regional body tissue distribution Measurements obtained from reference and laboratory BC methods (e.g. medical imaging systems such as MRI, CT and dual energy X-ray absorptiometry or DXA) and field methods (e.g. anthropometry) have been used to quantify body tissues and their distribution. From these anthropometry is the only technique that is readily available in the clinical setting.

2.1. Anthropometry in clinical practice

The use of anthropometry owes its popularity to its simplicity, inexpensiveness, portability and safety. Its convenience allows it to be applied in large population-based studies, in evaluating BC changes over time, as well as in clinical and field situations where access to sophisticated technology is limited. Although newly developed techniques have contributed significantly to the knowledge in BC over the last decades, their advent has not decreased the popularity of anthropometry which still remains the most widely used method for quantifying BC today. Moreover, their advent has created a renewed interest in anthropometry as imaging techniques can be used as BC standards. As a result, new potential applications of anthropometry are being explored in determining regional muscle and adipose tissue distribution. The general objective of this review is to determine the value and limitations of anthropometry in estimating regional BC for use in clinical practice.

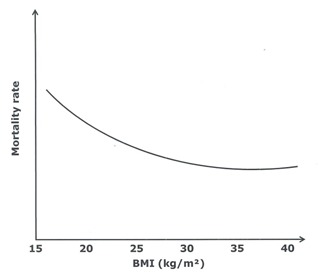

Researchers have suggested that simple regional data may often be of greater value than whole body values obtained by more sophisticated approaches [23]. The pioneer work of Vague, the importance of which has been recognized only recently [24, 25], has significantly contributed to the insight and current understanding of the relationship between obesity, body tissue distribution and health risk [26, 27]. Using anthropometry Vague constructed an index of obesity into a masculine and a feminine type, colloquially known as the “apple-shape” and “pear-shape” type respectively. He used the adipomuscular ratio, which is the ratio of AT to muscle areas on the upper and lower limbs. Despite the fact that there is still some controversy whether the total amount of AT, usually assessed by the body mass index (BMI) [28], or its distribution confers a greater risk for developing CVD [29], it has become increasingly clear that excess central or visceral AT is the key abnormality leading to CVD [30–32]. Proponents of the central obesity hypothesis have suggested that the latter could provide an explanation for the reduced mortality risk among patients with coronary heart disease and a high BMI, commonly referred to as the “obesity paradox” (Figure 1) [16, 33, 34].

Figure 1.

Association of BMI with mortality rate in patients with stable heart failure (adapted from Curtis et al. [33])

In the meta-analysis of Coutinho et al. [35], a large WC was particularly predictive of increased mortality among patients with presumably “normal” BMI values. It has been suggested that these patients might have less muscle, have a poor cardiorespiratory fitness, and most importantly characterized by an excess of visceral and by increased ectopic AT deposition for which excess liver fat and epi-/pericardial fat are salient features [36]. Studies have demonstrated that intra-abdominal or visceral AT, via a variety of mechanisms [37–40], is pro-atherogenic, but subcutaneous and/or peripheral AT is not [41–43]. In fact, recent evidence suggests that subcutaneous or peripheral AT protects against disturbed metabolism [44–46]. At the same time it has been shown that the association between mortality and high BMI decreases with advancing age [47]. Since it has been suggested that low BMI might be a sign of serious disease or a sign of the terminal phase in the oldest elderly persons, the assessment of muscle might be as important as that of AT distribution in this group [48].

Today, anthropometry remains the most widely applied method for BC quantification in clinical practice because of its distinct advantages.

2.2. Relationships between anthropometric indexes and AT distribution

Together with the BMI a number of other simple anthropometric indices such as waist circumference (WC) and waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) have been described as indices of obesity. Waist circumference-based indexes are regarded as indicators of abdominal obesity and as markers of regional AT distribution [49, 50]. Apart from WC and WHR, a number of other anthropometric indicators of abdominal obesity have been described, such as the waist-to-thigh ratio, abdominal sagittal diameter, waist-height ratio and conicity index, but these indexes are often more difficult to interpret because no reference values have been reported in the literature [51].

2.2.1. Body mass index (BMI)

The World Health organization (WHO) and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) promote the use of the BMI as a clinical index to classify overweight (BMI≥25kg/m2) and obesity (BMI≥30kg/m2) in adults [1, 52]. The use of BMI as an indicator of obesity is based on the observation that it seems to correlate well with total body adiposity at population level [53], even though it cannot discriminate between adipose and non-adipose tissue in individuals [54–56]. Moreover, the BMI cannot distinguish between different types of AT. Despite the fact that several meta-analyses, prospective and observational BMI studies have demonstrated its value in detecting increased mortality risk [14], its accuracy in diagnosing obesity is limited, especially in heavy (muscular) non obese individuals [13, 57–59]. As a result, the BMI might misclassify individuals as having normal or excessive amounts of AT [56, 60]. Thus, the BMI might be useful in the evaluation of nutritional transition trends in epidemiological research, its use as a BC tool for health assessment in individual subjects is questionable [61].

2.2.2. Waist circumference (WC)

The WHO and the NIH promote the use of sex-specific WC cut-offs to identify the increased relative risk for the development of obesity-associated morbidity in overweight (BMI≥25kg/m2) and in class I obese (30kg/m2≤BMI<35kg/m2) individuals [1, 52]. The rationale for its use is based on its apparent correlation with visceral AT [62, 63]. However, it has to be reminded that WC is a composite measure of all underlying tissues (including subcutaneous AT, muscle and organs). Therefore it has been argued that the accuracy of WC in quantifying visceral AT is influenced by inter-individual variability in AT composition [64–66] and measurement site [67]. In fact, the distribution of subcutaneous and visceral AT have proven to be related to an individual’s risk for CVD [68–70], since subcutaneous AT has a lower lypolitic activity compared to visceral AT [71]. Moreover, Hsieh and Yoshinaga [72] showed that metabolic risks differed between people of similar WC with different heights.

2.2.3. Waist-to-hip ratio (WHR)

There is a well-documented sex dimorphism in regional adipose distribution women having higher proportions of AT in the legs compared to men who more frequently accumulate excess AT within their abdominal cavity [73]. The WHR ratio is used as a clinical surrogate for regional AT distribution, hip circumference being representative for lower limb subcutaneous AT [49, 74–76]. Comparative cross-sectional evaluations of simple anthropometric indexes have suggested WC to be the best single indicator of cardiovascular risk [77], although recent evidence obtained from follow-up studies showed that adding hip circumference substantially increases predictive power for all cause and CVD mortality [78, 79]. However, it has been suggested that the WHR is not helpful in practical risk management because both the waist and hip circumference can decrease following weight reduction, with very little changes in WHR [80]. In summary, among the three adiposity indexes described here, the BMI seems to be the best correlate of total and subcutaneous AT in both genders [81, 82]. The WC is the anthropometric index that best correlates with absolute amounts of several abdominal AT compartments (e.g. intra-peritoneal, retro-peritoneal, and subcutaneous AT) [83], while the WHR best relates to relative AT distribution [80]. Although anthropometric indexes significantly correlate with adiposity measures in groups, inter-individual variability in tissue composition may lead to erroneous classification of subjects.

2.3. Prediction of tissue distribution with anthropometric variables

In order to improve the accuracy of body component estimations by indexes, multiple anthropometric variables, including skinfolds, circumferences, lengths, widths, weight, height and age have been combined to develop prediction equations. A number of anthropometric variables vary by age, sex and ethnicity [84]. For example, it has been shown that the BMI represents a higher level of adiposity in Asians compared to whites. Skinfold thicknesses are consistently higher in females compared to males and abdominal circumferences increase with increasing age in both genders.

The literature concerning the prediction of total body components, e.g. total body fat percentage, is very extensive, but equations were often validated against methods which today are no longer considered BC references methods [85, 86]. With regard to the estimation of regional components by anthropometry the scientific literature is much more limited, and mainly concentrated on the prediction of visceral adiposity and upper arm muscle mass. Again, it has to be reminded that the majority of anthropometric predictions are validated against indirect estimations of body components, with a few exceptions [87, 88].

2.3.1. Adipose tissue compartments

Adipose tissue compartments can be classified at the tissue–system level based on their distribution within the body. A classification proposed by Shen et al. [89] is given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Classification of adipose tissue compartments

| AT compartment | Definition |

|---|---|

| Total AT | Sum of adipose tissue, usually excluding bone marrow and adipose tissue in the head, hands, and feet |

| Subcutaneous AT | The layer found between the dermis and the aponeuroses and fasciae of the muscles. Includes mammary adipose tissue |

| Superficial subcutaneous AT | The layer found between the skin and a fascial plane in the lower trunk and gluteal-thigh area |

| Deep subcutaneous AT | The layer found between the muscle fascia and a fascial plane in the lower trunk and gluteal-thigh areas |

| Internal AT | Total adipose tissue minus subcutaneous adipose tissue |

| Visceral AT | Adipose tissue within the chest, abdomen, and pelvis |

| Intrathoracic | Sum of adipose tissue in the chest. Includes intrapericardial and extrapericardial adipose tissue |

| Intraabdominopelvic AT | Visceral adipose tissue minus intrathoracic adipose tissue |

| Intraperitoneal AT | Adipose tissue within the peritoneum of the abdomen. Includes omental and mesenteric adipose tissue |

| Extraperitoneal AT | Sum of adipose tissue outside the peritoneum and inside the abdomen or pelvis |

| Intraabdominal AT | Adipose tissue outside the peritoneum and inside the abdomen. Includes preperitoneal and retroperitoneal (e.g., perirenal, pararenal, periaortic, and peripancreatic) adipose tissue |

| Intrapelvic AT | Adipose tissue outside the peritoneum and inside the pelvis. Includes parametrial, retropubic, paravesical, retrouterine, pararectal and retrorectal adipose tissue |

| Nonvisceral internal AT | Internal adipose tissue minus visceral adipose tissue |

| Intramuscular AT | Adipose tissue within a muscle (between fascicles) |

| Perimuscular AT | Adipose tissue inside the muscle fascia (deep fascia), excluding intramuscular adipose tissue |

| Intermuscular AT | Adipose tissue between muscles |

| Paraosseal AT | Adipose tissue in the interface between muscle and bone (e.g., paravertebral) |

| Other nonvisceral AT | Orbital adipose tissue; aberrant adipose tissue associated with pathological conditions (e.g., lipoma) |

AT=adipose tissue

Some of the AT compartments defined above have aroused considerable research interest because of their relationship with metabolic disorders (e.g. visceral AT and intermuscular AT). Other smaller AT compartments have shown little interest to investigators, mainly because they are difficult to measure (e.g. intramuscular AT) or because they seemed to be irrelevant to health assessment (e.g. orbital AT).

In this section the amount and distribution of AT in the trunk, including visceral and subcutaneous AT, and AT mass quantification in the limbs using anthropometric variables will be reviewed.

2.3.1.1. Trunk adipose tissue

Adipose tissue in the trunk can be defined as the sum of the internal and subcutaneous AT compartments. Since it is well known that visceral AT concentration carries greater cardiovascular health risk compared to subcutaneous AT accumulation [90], it might be important to accurately quantify both compartments separately. In general, subcutaneous AT area can be approximated by BMI, skinfold thicknesses and/or age [91]. The prediction of visceral AT area appears to vary by sex and age. Together with these non-modifiable factors, BMI, WC and/or WHR seem to explain a large percentage of the variance in visceral AT area in both men and women [76, 91].

2.3.1.1.1. Visceral adipose tissue (VAT)

The amount of VAT increases with age in both genders [92], and this increase is present in normal weight (BMI, 18.5 to 24.9) as well as in overweight (BMI, 25 to 29.9) and obese subjects (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2) but more so in men than in women [71]. In general, adult men have more VAT compared to women of the same age [93]. In anthropometric validation studies the VAT compartment is generally assessed using single CT or MRI slices at a predefined lumbar level (e.g. L4–L5 or L3–L4), which is being used as a surrogate for total VAT volume [94]. This procedure may result in estimation errors of 7% to 9% in women and men respectively.

Although comparing results across studies remains a difficult task because of differences in methodology and sample characteristics, a number of similarities between anthropometric validation studies can be recognized. The most important observation is that among all AT compartments, the visceral VAT compartment is the hardest to assess accurately [95–97]. Seidell et al. [91] and Ferland et al. [98] reported that the VAT area (cm2) could be accurately predicted from anthropometry, but did not cross-validate their equations. Kvist et al. [94], who used the abdominal sagittal diameter as the single predictor for VAT volume reported estimation errors up to ±20%.

Even though anthropometric measurements may provide a useful indication of AT deposition in a clinical setting [99–101], most studies concluded that the estimation of VAT using anthropometry is limited, explaining between 50% and 80% of the variance in VAT area in both sexes [76, 102–106]. An overview of the predictive capacity of anthropometry for trunk visceral AT is given in Table 2. In spite of the errors associated with the anthropometric prediction of VAT it has been suggested that a cut-off value of 130cm2for VAT area could be used as an estimate of an increased risk for metabolic abnormality (e.g dyslipidemia, raised glucose concentration, systemic inflammation) in clinical practice [107].

Table 2.

Predictive capacity of anthropometric equations for visceral AT area of the trunk in adults

| Author | Method | VAT area equations | R2(%) | Age range (y) | Cross-validation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seidell et al. [91] | CT | = (0.35*BMI) + (1.48*∑ umbiliusSF and suprailiacSF) + (34.122*WHR) + (0.06*age) – 37.322 (M) | 81.9 | 19–85 | no |

| = (0.367*BMI) + (WTR*10.911) + (0.994*menopausal statea) – 15.083 (F) | 79.5 | ||||

| Kvist et al. [94] | CT | VAT (cm3) = (0.731*sagittal diameterb) – 11.5 (M) | 81.0 | 24–64 | yes |

| VAT (cm3) = (0.370*sagittal diameterb) – 4.85 (F) | 79.6 | ||||

| Weits et al. [99] | CT | = (3.27071*WC) + (3.74794*HC) – 558.25696 (M) | 74.0 | 16–81 | yes |

| = (2.00558*WC) + (2.32435*HC) – 319.21927 (F) | 56.0 | ||||

| Ferland et al. [98] | CT | = (1.0652*weight) + (1.6649*abdominalSF) + (1.6934*subscapularSF) + (200.9726*WHR) + (1.7137*age) – 292.1026 (F) | 73.7 | 23–50 | no |

| Despés et al. [102] | CT | = (2.843*WC) + (2.125*age) – 225.39 (M) | 74.0 | 18–42 | no |

| Koester et al. [103] | CT | = (3.4838*WC) – (67.0158*log chest ratioc) – 157.7378 (M) | 67.0 | 18–30 | yes |

| Kekes–Szabo et al. [95] | CT | = (4.37*WC) +(0.75*age) + (1.26*abdominalSF) – (1.55*∑legCCd) – 202.04 (M) | 73.0 | 18–71 | yes |

| Bonora et al. [76] | MRI | = (6.37*WC) – 453.7 (M) | 56.0 | 22–70 | no |

| = (4.04*WC) + (2.62*age) – 370.5 (F) | 68.0 | ||||

| Kekes-Szabo et al. [96] | CT | = (2.57*umbilicusCC) + (0.69*suprailiacSF) + (0.92*age) – 188.61 (F) | 75.0 | 17–76 | yes |

| Schreiner et al. [97] | MRI | eWHR, age (M) | 32.9 | 48–68 | no |

| eWC (F) | 42.8 | ||||

| Stanforth et al. [107] | CT | Ln (VAT) = (0.05*BMI) + (3.2*WHR) + (0.02*age) + (0.36*racef) – 0.70 (M) | 78.0 73.0 |

17–65 | yes |

| Ln (VAT) = (0.05*BMI) + (1.85*WHR) + (0.02*age) + (0.22*racef) + 0.33 (F) | |||||

| Brundavani et al. [104] | CT | = (1.09*weight) – (2.29*BMI) + (6.04*WC) – 382.9 (M) | 74.2 | 40–79 | no |

| = (5.19*WC) – (0.86*weight) – 278 (F) | 62.6 | ||||

| Bouza et al. [105] | CT | = (3.413*WC) – (2.281*HC) + (3.306*age) – 27.765 (M+F) | 62.0 | 18–78 | no |

| Goel et al. [106] | MRI | = (16.9*age) + (934.18*sexg) + (578.09*BMI) – (441.06*HC) + (434.2*WC) – 238.7 (M+F) | 52.1 | 15–50 | no |

| Eastwood et al. [108] | CT | = h (1.87*age) + (2.80*weight) – (1.79*height) + (7.57*WC) – (4.91*HC) – (2.85*TC) + 67.88 (M) | 69.0 | 58–85 | yes |

| = h (0.90*age) + (2.71*weight) + (2.62*WC) – (1.75*TC) – 250.86 (F) | 62.0 | ||||

| = i (0.94*age) + (8.63*WC) + (1.47*TC) – (3.86*HC) – 422.31 (M) | 73.0 | ||||

| = i (2.20*age) + (3.20*weight) – (2.42*height) + (3.35*WC) – (4.93*HC) + 323.39 (F) | 56.0 | ||||

| = j (1.18*age) + (2.16*weight) – (2.35*height) + (6.56*WC) – (2.15*HC) – (1.81*TC) + 39.24 (M) | 61.0 | ||||

| = j (1.13*age) + (6.28*weight) – (2.47*height) + (1.85*WC) – (3.71*HC) – (4.35*TC) + 475.69 (F) | 55.0 |

AT=adipose tissue; BMI = body mass index (kg/m2); WC = waist circumference (cm); HC = hip circumference (cm); TC = thigh circumference (cm); CC= circumference (cm); WHR = waist-to-hip ratio; WTR = waist-to-thigh ratio; VAT = visceral adipose tissue (cm2); CT = computed tomography; MRI = magnetic resonance imaging; M = for men, F = for women;

1 = postmenopausal, 0 = premenopausal;

obtained by CT (cm);

logarithm of the chest circumference divided by the chest skinfold thickness;

∑legCC = sum of the mid-thigh and lower thigh circumference (cm);

exact equation not given;

black = 0, white = 1;

male = 1, female = 2;

white European;

African Caribbean;

South Asian; sagittal diameter (cm); age (years).

2.3.1.1.2. Abdominal subcutaneous adipose tissue (SAT)

The amount of whole body SAT increases until the age of 55–65 and decreases afterwards in both genders [84]. In men the changes in SAT thickness occur predominantly in the abdominal area, while in women they are more general. This might explain the inclusion of suprailiac and abdominal skinfolds in male prediction equations. Table 3 shows that abdominal SAT can be estimated accurately using anthropometric variables such as BMI, age, abdominal skinfolds and/or trunk circumferences, explaining approximately 75% to 90% of the variance in SAT area in both genders.

Table 3.

Predictive capacity of anthropometric equations for subcutaneous AT area of the trunk in adults

| Author | Method | SAT area equations | R2(%) | Age range (y) | Cross-validation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seidell et al. [91] | CT | = (0.157*BMI) + (1.63*∑ umbiliusSF and suprailiacSF) + (29.159*WHR) + (0.051*age*) – (10.694*WTR) – 18.798 (M) | 79.4 | 19–85 | no |

| = (0.373*BMI) + (1.301*∑ umbiliusSF and suprailiacSF) – 3.327 (F) | 84.2 | ||||

| Weits et al. [99] | CT | = (10.58479*BMI) + (3.20392*HC) – 430.0784 (M) | 71.0 | 16–81 | yes |

| = (12.47853*BMI) + (4.43236*HC) – 505.06653 (F) | 77.0 | ||||

| Koester et al. [103] | CT | = (3.9545*WC) + (1.0041*∑ abdominalSF and suprailiac SF) – 297.2438 (M) | 78.0 | 18–30 | yes |

| Kekes-Szabo et al. [95] | CT | = (3.98*umbilicusCC) + (2.31*chestSF) + (3.41*suprailiacSF) + (1.84*age) – 398.78 (M) | 77.0 | 18–71 | yes |

| Bonora et al. [76] | MRI | = (9.37*BMI) + (5.51*HC) – 621.0 (M) | 87.0 | 22–70 | no |

| = (24.5*BMI) + (2.26*age) – 332.9 (F) | 87.0 | ||||

| Kekes-Szabo et al. [96] | CT | = (11.86*BMI) + (3.12*umbilicusCC) + (2.22*suprailiacSF) + (1.32*horizontal abdominalSF) – (2.63*shoulderCC) – 155.85 (F) | 81.0 | 17–76 | yes |

| Schreiner et al. [97] | MRI | a WC2, tricepsSF, HC, height, age2(M) | 74.1 | 48–68 | no |

| aWC, HC (F) | 75.5 | ||||

| Bouza et al. [105] | CT | = (7.245*BMI) + (8.653*HC) – (78.262*sexb) – (1.765*age) – 683.11 (M+F) | 76.0 | 18–78 | no |

| Goel et al. [106] | MRI | = (783.3*BMI) + (466*HC) – (17.15*age) + (1016.5*sexc) – 49376.4 (M+F) | 67.1 | 15–50 | no |

| Eastwood et al. [108] | CT | = d (2.29*weight) + (2.34*WC) + (2.49*HC) – (1.19*age) – (2.00*height) – 28.95 (M) | 72.0 | 58–85 | yes |

| = d (3.76*weight) + (7.01*HC) – (0.99*age) – (3.07*height) – (3.03*TC) + 24.98 (F) | 80.0 | ||||

| = e (3.83*WC) + (6.52*HC) – (0.08*age) – (2.09*height) – (1.23*TC) – 373.61 (M) | 81.0 | ||||

| = e (0.23*age) + (2.24*WC) + (9.48*HC) – 896.27 (F) | 86.0 | ||||

| = f (0.63*age) + (3.88*weight) – (3.21*height) + (1.43*WC) + (2.54*HC) + 48.58 (M) | 75.0 | ||||

| = f (3.94*weight) + (5.63*HC) – (1.72*age) – (5.21*height) + 404.25 | 81.0 |

AT = adipose tissue; BMI = body mass index (kg/m2); WC = waist circumference (cm); HC = hip circumference (cm); TC = thigh circumference (cm); CC= circumference (cm); WHR = waist-to-hip ratio; WTR = waist-to-thigh ratio; SF = skinfold (mm); SAT = abdominal subcutaneous adipose tissue (cm2); CT = computed tomography; MRI = magnetic resonance imaging; M = for men, F = for women;

exact equation not given;

male = 1, female = 0;

male = 1, female = 2; ;

white European;

African Caribbean;

South Asian; age (years).

In summary, SAT can be estimated more accurately than VAT from anthropometry in both genders. A number of sex specific variables can be identified as best predictors of trunk AT compartments, but no ‘gold’ standard prediction equation exists. The VAT:SAT ratio cannot be accurately predicted [91].

2.3.1.1.3. Total trunk adipose tissue

Total trunk AT is the sum of SAT, VAT and nonvisceral AT (e.g. intermuscular AT). It has been shown that trunk AT can be estimated at the tissue-system level using the same anthropometric variables used for the prediction of VAT or SAT, but with higher predictive accuracy (R2≥0.85) [91, 94–96].

Total trunk adiposity has also been quantified at the molecular BC level. It has been shown that trunk AT assessed by CT is strongly correlated to trunk fat mass (FM) by DXA [109]. Predicting trunk FM using two or more anthropometric indices (BMI, WC, WHR and conicity index) resulted in higher accuracy than using BMI or WC alone [110–112]. Studies have also shown that age has important effects on the relationship between fat mass of the trunk and these anthropometric indices.

2.3.1.2. Upper and lower limb adipose tissue

Limb AT consists mainly of subcutaneous and intermuscular AT (IMAT). It has recently been suggested that IMAT represents an AT depot with similar metabolic characteristics as the VAT depot [113–115]. Intermuscular AT is associated with poor physical performance [116] and with impaired glucose tolerance [117]. To the knowledge of the author there are no anthropometric prediction equations for estimating the IMAT compartment. Anthropometric prediction equations for the estimation of total AT in the upper and lower limb segments have been validated against cadaver dissection [87, 88]. Accurate predictions (R2between 0.80 and 0.98) of limb AT were obtained using intra-segmental lengths and (corrected) skinfolds.

At the molecular BC level, anthropometric prediction equations for leg and arm FM have been developed and cross-validated against DXA. These equations explained 69% and 87% of the variance in leg and arm FM respectively [118–120].

2.3.2. Muscle tissue compartments

Muscle mass varies by sex, age and ethnicity. It is well known that men have more muscle in absolute and relative terms compared to women at all adult ages and for all body regions [121, 122], the proportional difference being the greatest in the arm segment [123]. Cross-sectional data indicate that skeletal muscle atrophy may start around the age of 30–40 years and progresses at an average rate of 1% per year until the age of 70 years, above which the process accelerates dramatically up to 3% per year [124]. Age-related muscle wasting appears to affect all muscle compartments, but most noticeably the leg compartment [125]. With regard to racial differences, it has been shown that black persons have approximately 5% more lean tissue compared to white ones [126].

Muscle tissue compartments can be subdivided according to anatomical region (e.g. arm, trunk or leg) and physiological function (e.g. skeletal and non-skeletal muscle). The amount and distribution of skeletal muscle mass has been related to physical performance in sports and aging [127, 128] and to long-term mortality in elderly persons [129]. Non-skeletal muscle mass (organ mass) is currently being investigated as a means of quantifying resting energy expenditure [130, 131].

In this section the quantification of muscle distribution in the limbs and trunk using anthropometry will be reviewed.

2.3.2.1. Upper and lower limb muscle mass

Historically, estimates of upper arm muscle circumference have served as a functional index of protein-energy malnutrition [132]. The anthropometric method for estimating muscle is based on the conceptual assumption that human extremities are modeled as concentric cylinders of bone, muscle and subcutaneous AT plus skin. Hence, limb circumference (CC) and its corresponding skinfold thickness (SF) can be used to calculate skinfold-corrected circumference (i.e. muscle plus bone) [133, 134]. Since the skinfold measurement includes two thicknesses of AT [135]:

| (1) |

Squaring the skinfold-corrected circumference provides the muscle plus bone tissue area (A).

| (2) |

Correcting the bone plus muscle area for assumed bone and AT area within the lean tissue area yields the “true” muscle area [136].

| (3) |

Multiplying the muscle area by length (L) and reference density (ρ) of 1.04 g/cm3[137] gives limb muscle mass (M).

| (4) |

The anthropometric prediction of limb muscle has been performed against estimates of muscle area (equation 3) obtained by single slice CT or MRI, with or without correcting for bone and AT area within the lean tissue cylinder.

Intra- and interindividual variations in AT patterning often led to inaccuracies (over- or underestimation) in muscle tissue estimates. For example, elderly and obese persons may have a considerable amount of IMAT within the lean tissue compartment, leading to an overestimation of muscle if not corrected appropriately. Also, in malnutrition or wasting the assumption of concentricity of compartments may not be valid. Last but not least the skinfold measure is subjected to a non-negligible interobserver measurement error. Despite the fact that correction factors for the overestimation of arm muscle area in patients were proposed, an average estimation error of ±8% had to be taken into account [136]. Buckley et al. [138] and Forbes et al. [139] stated that anthropometry yields inaccurate estimates of limb component areas. All assumptions and errors considered, the validity of anthropometry in predicting muscle cross-sectional area has been confirmed in young healthy individuals [140, 141], but its accuracy in obese, elderly and undernourished persons has been repeatedly criticized [139, 142–145].

There have been also a number of attempts to quantify limb muscle mass in elderly [87, 88] and limb lean mass (molecular level) in young adults [112, 118, 119, 146, 147] using regression analysis. Although most of these regression based equations showed high predictive capacity (R2>0.80), their validity is largely unknown since they were not always cross-validated on separate samples.

It is suggested that anthropometry may provide accurate predictions of regional muscle estimates in young healthy adults, but additional work needs to be done in order to establish its validity in other groups.

2.3.2.2. Trunk muscle mass

Muscle mass in the trunk mainly consists of skeletal muscle located around the vertebrae and smooth muscle found within the walls of the organs. Skeletal muscle of the trunk accounts for about 25 to 30% of the total weight of the musculature at maturity. At the same time it may represent between 20 and 30% of total trunk weight in elderly persons [121]. Loss of trunk muscle mass has been associated with chronic low back pain [148].

Recent evidence suggests that non-skeletal muscle varies by age independent of sex or ethnicity [149]. For example, it has been shown that kidneys, liver, spleen, and heart mass decrease with increasing age. Organ mass also appears to be related to weight and height, explaining about 80% of the between subject variability in REE [150]. Thus, accurate estimates of trunk muscle composition may provide useful information regarding the energy an individual spends at rest.

To the knowledge of the author there are no anthropometric prediction formulae that estimate the muscle compartments in the trunk.

In summary, no work has been performed with regard to the prediction of trunk muscle quantities and/or tissue distribution by anthropometry.

3. Use and interpretation of regional tissue distribution measurement by anthropometry in clinical practice

Body mass index, WC and WHR are used to classify individuals in terms of overweight and abdominal obesity, respectively [151]. These anthropometry based indexes are used across sexes, age groups and ethnicities. In clinical practice health risk assessment is based on the use of cut-off values that have been proposed for a number of these anthropometric indexes. However, anthropometric index numbers or values do not necessarily represent the same quantitative components among different groups because of the variation in BC. Therefore group specific cut-off values have been proposed for defining health risk. In order to account for the obvious gender differences in BC cut-off values based on WC and WHR are proposed for men and women separately [152–155]. Similarly and in order to account for BC differences between races it has been suggested to lower BMI ranges by 1 to 2 kg/m2for diagnosing overweight and obesity in Asians compared to whites [153, 156]. These examples suggest that the relationship of anthropometry with physiological and metabolic characteristics is partially determined by non-modifiable factors such as gender and ethnicity. However, there are also a number of other modifiable factors influencing the relationship between anthropometry, body composition and health such as physical activity, smoking status and alcohol consumption. When interpreting anthropometric measures in clinical practice BC changes that occur during lifetime and confounding variables with regard to health assessment should also be taken into account. In the following paragraphs a number of factors that affect the relationship between anthropometry and regional BC are briefly discussed.

3.1. Relationship between anthropometry and regional body composition: influence of age and gender, physical activity, ethnicity and genetics

3.1.1. Age and gender differences

The rather common practice to extrapolate anthropometric measures collected on young adults to the elderly is prone to criticism as physical characteristics and BC change significantly during life [157].

Height decreases with age in adults, mainly because of spinal shrinkage [158]. The rate of decline is 1–2 cm/decade and more rapid at older ages [151]. The Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging showed that the degree of height loss would account for an “artificial” increase in BMI of approximately 1.4 kg/m2for men and 2.6 kg/m2 for women by the age of 80 years [159]. This shows that height loss with aging must be taken into account when anthropometric indexes based on height (e.g. BMI, fat-free mass index, waist-height ratio) are used in BC studies [160].

Weight also changes during lifetime, but the pattern is different from that of height and varies by gender. Cross-sectional analyses of body weight suggest that mean body weight increases with age until late middle age, then stabilizes and decreases at older ages [161]. However, the decline appears to initiate at an earlier age interval for men (60–64 years) than for women (65–69 years). Weight changes are the resultant of quantitative and qualitative changes in body compartments [162, 163].

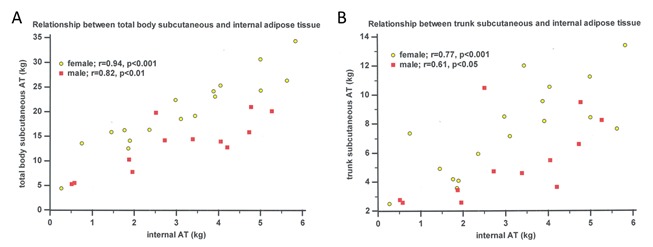

Body composition changes in middle age are mainly the resultant of an increase in adipose tissue. At the same time the lipid content of various tissues increases with aging. In old age weight loss results from a reduction of muscle, bone and organ mass which reflects the qualitative loss of mineral, protein and water content of the forenamed tissues [162, 164, 165]. In addition to the changes in whole body composition, adipose tissue is redistributed. As AT increases more pronouncedly in the abdominal region with advancing age, lipids also tend to be stored preferentially in internal compartments (e.g. in visceral and intermuscular AT) [166, 167]. It should be kept in mind that the latter is not reflected in anthropometric measurements of subcutaneous AT, since there is considerable between-subject variability in the relationship between subcutaneous AT and internal AT, particularly in men (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Relation between subcutaneous and internal AT in elderly persons (n=29). AT = adipose tissue, internal AT = sum of intraperitoneal, retroperitoneal and intermuscular AT (adapted from Martin et al. [168] & Clarys et al. [169])

Lean body tissue is replaced by AT in aging, while a redistribution of AT between and within body regions occurs. In the light of the above-mentioned changes in BC it is obvious that simple anthropometric variables, for example BMI, WC and WHR which are being used as surrogates for overall and/or regional adiposity, cannot represent the same BC compartments in young and old persons.

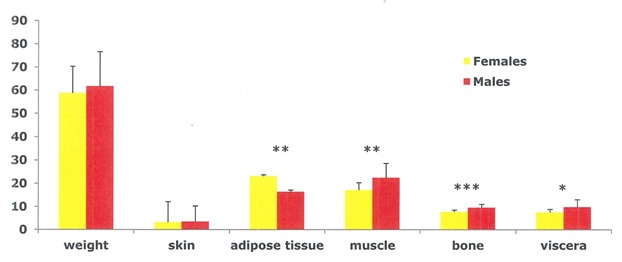

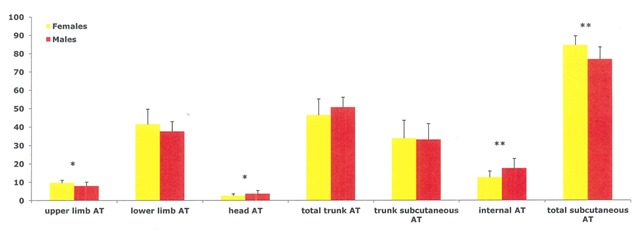

It has become almost superfluous to stress that BC differs significantly between genders from puberty to old age, males having greater muscle and bone mass and lower AT mass compared to women [56, 60, 73, 121, 169–172]. The observed whole BC differences are complemented by major differences in regional tissue distribution which are less obvious (Figures 3–4).

Figure 3.

Sex differences in tissue composition (kg) in weight and age-matched elderly men and women. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 (adapted from Scafoglieri et al. [60])

Figure 4.

Sex differences in regional AT composition (as a percentage of total AT) in weight and age-matched elderly men and women. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 (adapted from Scafoglieri et al. [60])

Before menopause women tend to store AT in the subcutaneous compartment, whereas after menopause they exhibit a more android fat distribution as seen in males. Despite the fact that women have more AT compared to men, a larger proportion is stored subcutaneously and in the limbs. There is evidence that catecholamine mediated leg free fatty acid (FFA) release is lower in women than in men, whereas FFA release from the upper body depots is comparable [173]. Moreover, FFA release by the upper body subcutaneous AT depots is higher in men than in women, indicating a higher resistance to the antilipolytic effect of meal ingestion in the upper body AT depots in men. Furthermore, a time-delay exists concerning the internalization (i.e. the preferential accumulation of lipids in the deep AT compartments) as opposed to storing fat in the subcutaneous AT compartment of AT that persists in old age [174]. Therefore it has been suggested that ageing women exhibit a lower cardiovascular risk compared to ageing men [175].

3.1.2. Physical activity

One of the most important confounding factors profoundly influencing the relationship between obesity and mortality is physical activity [15]. In fact, it has been shown that the mortality risk associated with obesity is offset when cardiovascular fitness is taken into account [16, 17]. Physical activity attenuates quantitative and qualitative BC changes with aging. Firstly, exercise promotes the mobilization of lipids (triglycerols) from adipose and muscle tissue preventing hyperplasia and/or hypertrophy of AT and excessive storage of lipids in ectopic sites such as in the liver and muscles, which are deleterious to health [176]. For example, recent evidence suggests that physical activity may either prevent or reduce the age-related gain in VAT [177]. Also, visceral adipocytes are more sensitive than subcutaneous adipocytes to lipolytic stimulation [178]. In this context it has been pointed out that higher activity or fitness attenuates the health risks of obesity [179]. Moreover, active obese individuals have lower morbidity and mortality than normal weight individuals who are sedentary [180]. Therefore, it has been suggested that using adiposity to assess mortality risk may be misleading unless fitness is considered [18].

Secondly, it has been shown that regular physical activity preserves protein content of muscle conditional to an abundant amino acid supply and mineral content of bone tissue, counteracting the increasing risk of disability and fracture in old age [181]. Furthermore, by contracting the skeletal muscle releases “myokines” in a dose-response related manner, influencing both the immune system and AT metabolism. As a result, physically active people have lower cardiovascular risk and lower circulating inflammatory markers [182].

All the above suggests that physical activity modifies the relationship between anthropometry, BC and health risk [18, 183, 184].

3.1.3. Ethnicity

It is well known that BC is influenced by ethnicity [185]. Compared to white and black people, Asians have higher whole body and visceral adiposity with similar BMI [186]. Therefore it is suggested that Asians are subjected to a higher cardiovascular risk compared to other races of similar BMI [187].

It has been shown that black people have significantly higher amounts of bone and lean mass compared to other ethnic groups [188, 189]. Evidence also suggests that the former are at decreased relative osteoporosis and osteoporotic fracture risk.

3.1.4. Genetics

Although it is estimated that more than 300 genes may intervene in obesity, only a few are directly involved in the aetiology of obesity [190]. The Québec Family Study and the Heritage Family Study have provided evidence for a genetic effect on abdominal AT (total, subcutaneous and visceral) levels [191, 192]. In both studies a major gene effect was found for VAT, but the effect disappeared after adjustment for total AT mass [193]. This suggests that there are shared familial determinants for total and visceral AT mass. For all measures of abdominal AT there are consistent heritabilities of 25% to 70% [190]. Several markers in genomic scans have shown linkages with abdominal AT, in particular with subcutaneous AT [194, 195]. For example, it has recently been shown that after adjustment for age and sex, carriers of the rare allele rs11680012 in the LRRFIP1 gene have ∼30% more abdominal adiposity and 75% higher C-reactive protein levels than carriers of the common allele [196]. Therefore, it has been suggested that genetic variation contributes to the aetiology of obesity and increased cardiovascular risk [197].

In summary, anthropometric variables including simple indexes, circumferences but also skinfolds are likely to relate differently to quantitative and qualitative BC aspects during lifetime. Their association with BC is influenced by modifiable and non-modifiable factors. The results presented in this work are therefore only appropriate for age, gender, physical activity and ethnicity-matched groups and should not be extrapolated to other groups.

3.2. Using anthropometry in individuals

As discussed above a number of intrinsic limitations are common to the use of anthropometry in all age groups. These include the interpretation of anthropometric variables with regard to the changes in BC, but the measurement error should not be ignored either [199]. In clinical practice it is important to ascertain that BC indices are subject to intra- and inter-observer variability [200]. In general, the reliability of weight-height indexes (e.g. BMI) is greater than that for circumferences, whose reliability in turn is greater than for skinfold measurements and bone breadths [201–204]. It has been shown that reliability of skinfold measurement decreases linearly with skinfold thickness corresponding to a coefficient of variation of 13–19 per cent [205]. When used in prediction equations inter-observer differences may lead to mean errors ranging from 3% to 24% for regional BC [206].

The interpretation of anthropometric variables with regard to BC is affected by inter-individual variability in tissue composition. In anthropometry it is commonly assumed that the tissues included in the measurement are in a ‘standard’ state [207]. If these conditions are not met, interpretation of the data may be invalid. For example, body circumferences may be affected by oedema. Since extracellular fluid cannot be measured with anthropometry, circumferences should not be used for BC assessment in persons with visible signs of limb swelling or ascites. Furthermore, it is recognized that tension of the abdominal wall influences the accuracy of WC measurement [208]. Some overweight or obese persons may present significant laxity of the anterior abdominal wall. This condition is accompanied by movement of the small intestine and transverse colon to the lower vertebral levels during standing. Consequently, muscle weakness of the anterior abdominal wall increases waist circumference.

Skinfold thicknesses are affected by the compressibility of SAT, which varies by site, age and sex [135]. The variations in compressibility reflect differences in fluid content, connective tissue content and skin thickness. Although skinfolds are less affected by water content than circumferences because caliper pressure reduces the fluid content of the SAT, inter-individual differences in skinfold compressibility may increase measurement error of skinfold thicknesses [207]. Finally, it has been shown that skin thickness may represent between 1/10th and 1/3rd of the total skinfold reading [135]. Since skinfold sites may represent different proportions of skin between subjects, this may also lead to errors in estimating the underlying SAT.

As a result of between-observer measurement error and between-subject variability in tissue composition, misclassification may occur [58, 209]. Despite the fact that standardization of circumference and skinfold assessment may decrease the measurement error, inaccuracies due to inter-individual differences in tissue composition cannot be solved [67]. However, misclassification of individuals based on simple anthropometric indexes, such as BMI or WC, may be limited using a combination of AT distribution measurements and/or by interpreting results in combination with metabolic risk factors [151, 210, 211]. In summary, evidence suggests that anthropometry might be useful in clinical practice as a screening tool for health risk assessment, especially if regional tissue distribution can be measured accurately and provided that results are applied to the appropriate populations.

4. Concluding remarks and future research suggestions

Today, BC assessment is routinely carried out in clinical settings. Anthropometry is used in the evaluation of growth, aging, physical performance and health risk assessment. Whether it is the study of childhood or adult obesity, weight gain or loss, or metabolic function or disease, understanding which components of BC contribute to clinical relevancy or performance is of paramount importance. Observations that regional accumulation or depletion of AT or fat are indicative for an increased risk of chronic disease and that wasting of muscle or lean tissue is linked to loss of mobility have prompted an advance in the use of methods to assess regional BC in humans [212]. The search of a practical tool to accurately assess regional BC is an ongoing process that is constantly triggered by the development of new methodologies.

Anthropometric equations might prove useful in quantifying regional lean and fat from young to middle-age or in screening for abnormal fat distribution. Since these equations are only valid for similar populations as the ones they were developed and validated on they cannot be generalized.

Clinicians should be on the alert for potential errors and threats associated to the use of readily available techniques and/or methodologies for BC assessment in elderly persons. They confirm earlier observations that accurate quantification of deep compartments using anthropometry is delicate because of important interindividual variability in tissue distribution (e.g. intermuscular AT). On the other hand, these findings also highlight the need for developing valid practical alternatives to assess regional BC in elderly persons.

It has been demonstrated that the search for an accurate and practical method to quantify tissue distribution in the elderly presents an important challenge. Prediction equations for regional tissue distribution in the elderly may be established in a similar way as the ones presented in this review for other groups. However, there are indications that achieving a high accuracy for predicting BC components using anthropometry in elderly persons is more difficult compared to young subjects. Therefore it should also be investigated whether a combination of anthropometry and other accepted field methods (e.g. segmental bio-electrical impedance analysis, ultrasound) can improve the prediction of tissue distribution. This might possibly be achieved by incorporating ‘raw’ (i.e. manufacturer independent) measures in the anthropometric prediction equations.

Finally, it is suggested to develop and cross-validate regional prediction equations using other criterion methods than DXA (e.g. MRI) as it remains unclear whether DXA is an appropriate tool for assess metabolically different compartments. In addition, new technologies in the field of BC, such as the recent development of quantitative MRI, may add significant knowledge in search of a practical tool for regional BC assessment [213].

References

- [1]. WHO Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic Report of a WHO Consultation. WHO Technical Report Series 894, Geneva, World Health Organization, 2000. [PubMed]

- [2].WHO. Report of a WHO consultation. Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 2000;894:1–253. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Romero-Corral A, Lopez-Jimenez F, Sierra-Johnson J, Somers VK. Differentiating between body fat and lean mass-how should we measure obesity? Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab. 2008;4:322–323. doi: 10.1038/ncpendmet0809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Szabó T, von Haehling S, Doehner W. Differentiating between body fat and lean mass--how should we measure obesity? Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab. 2008;4:E1. doi: 10.1038/ncpendmet0999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Lavie CJ, De Schutter A, Patel DA, Romero-Corral A, Artham SM, Milani RV. Body composition and survival in stable coronary heart disease: impact of lean mass index and body fat in the “obesity paradox”. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:1374–1380. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.05.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Larsson B, Svärdsudd K, Welin L, Wilhelmsen L, Björntorp P, Tibblin G. Abdominal adipose tissue distribution, obesity, and risk of cardiovascular disease and death: 13 year follow up of participants in the study of men born in 1913. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1984;288:1401–1404. doi: 10.1136/bmj.288.6428.1401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Marriott BM, Grumstrup-Scott J. Body composition and physical performance Applications for the Military Services. National Academy Press; Washington D.C.: 1992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Wells JC. An evolutionary perspective on the trans-generational basis of obesity. Ann Hum Biol. 2011;38:400–409. doi: 10.3109/03014460.2011.580781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Guh DP, Zhang W, Bansback N, Amarsi Z, Birmingham CL, Anis AH. The incidence of co-morbidities related to obesity and overweight: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:88. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Abdullah A, Peeters A, de Courten M, Stoelwinder J. The magnitude of association between overweight and obesity and the risk of diabetes: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2010;89:309–319. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2010.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Wolin KY, Carson K, Colditz GA. Obesity and cancer. The oncologist. 2010;15:556–565. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2009-0285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Lenz M, Richter T, Mühlhauser I. The morbidity and mortality associated with overweight and obesity in adulthood: a systematic review. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2009;106:641–648. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2009.0641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].McGee DL, Diverse Populations Collaboration Body mass index and mortality: a meta-analysis based on person-level data from twenty-six observational studies. Ann Epidemiol. 2005;15:87–97. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2004.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Prospective Studies Collaboration. Whitlock G, Lewington S, Sherliker P, Clarke R, Emberson J, Halsey J, Qizilbash N, Collins R, Peto R. Body-mass index and cause-specific mortality in 900 000 adults: collaborative analyses of 57 prospective studies. Lancet. 2009;373:1083–1096. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60318-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Ortega FB, Lee DC, Katzmarzyk PT, Ruiz JR, Sui X, Church TS, Blair SN. The intriguing metabolically healthy but obese phenotype: cardiovascular prognosis and role of fitness. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:389–397. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].McAuley PA, Blair SN. Obesity paradoxes. J Sports Sci. 2011;29:773–782. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2011.553965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].McAuley PA, Artero EG, Sui X, Lee DC, Church TS, Lavie CJ, Myers JN, España-Romero V, Blair SN. The obesity paradox, cardiorespiratory fitness, and coronary heart disease. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87:443–451. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].McAuley PA, Smith NS, Emerson BT, Myers JN. The obesity paradox and cardiorespiratory fitness. J Obes. 2012;2012:951582. doi: 10.1155/2012/951582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Scafoglieri A, Tresignie J, Provyn S, Clarys JP, Bautmans I. Reproducibility, accuracy and concordance of Accutrend Plus for measuring circulating lipid concentration in adults. Biochem Med (Zagreb) 2012;22:100–108. doi: 10.11613/bm.2012.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation. 2002;106:3143–3421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Pierson RN., Jr A brief history of body composition – from F.D. Moore to the new Reference man. Acta Diabetol. 2003;40:S114–S116. doi: 10.1007/s00592-003-0041-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Bredella MA, Ghomi RH, Thomas BJ, Torriani M, Brick DJ, Gerweck AV, Misra M, Klibanski A, Miller KK. Comparison of DXA and CT in the assessment of body composition in premenopausal women with obesity and anorexia nervosa. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2010;18:2227–2233. doi: 10.1038/oby.2010.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Wells JC, Fewtrell MS. Measuring body composition. Arch Dis Child. 2006;91:612–617. doi: 10.1136/adc.2005.085522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Vague J. Sexual differentiation. A determinant factor of the forms of obesity. 1947. Obes Res. 1996;4:201–203. doi: 10.1002/j.1550-8528.1996.tb00535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Vague J. The degree of masculine differentiation of obesities: a factor determining predisposition to diabetes, atherosclerosis, gout, and uric calculous disease. 1956 Nutrition. 1999;15:89–90. doi: 10.1016/s0899-9007(98)00131-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Vague J. La differenciation sexuelle, facteur déterminant des formes de l’obesité. Presse Med. 1947;55:339–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Vague J. The degree of masculine differentiation of obesities: a factor determining predisposition to diabetes, atherosclerosis, gout and uric calculous disease. Am J Clin Nutr. 1956;4:20–34. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/4.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Keys A, Fidanza F, Karvonen MJ, Kimura N, Taylor HL. Indices of relative weight and obesity. J Chronic Dis. 1972;25:329–343. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(72)90027-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Sheldon EL. Which Measures of Obesity Best Predict Cardiovascular Risk? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:616–619. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Stern MP, Haffner SM. Body fat distribution and hyperinsulinemia as risk factors for diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Arteriosclerosis. 1986;6:123–130. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.6.2.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Stevens J. Obesity, fat patterning and cardiovascular risk. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1995;369:21–27. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-1957-7_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Demerath EW, Reed D, Rogers N, Sun SS, Lee M, Choh AC, Couch W, Czerwinski SA, Chumlea WC, Siervogel RM, Towne B. Visceral adiposity and its anatomical distribution as predictors of the metabolic syndrome and cardiometabolic risk factor levels. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88:1263–1271. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.26546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Curtis JP, Selter JG, Wang Y, Rathore SS, Jovin IS, Jadbabaie F, Kosiborod M, Portnay EL, Sokol SI, Bader F, Krumholz HM. The obesity paradox: body mass index and outcomes in patients with heart failure. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:55–61. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Després J-P. Excess visceral adipose tissue/ectopic fat. The missing link in the obesity paradox? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:1887–1889. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.10.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Coutinho T, Goel K, Corrêa de Sá D, Kragelund C, Kanaya AM, Zeller M, Park JS, Kober L, Torp-Pedersen C, Cottin Y, Lorgis L, Lee SH, Kim YJ, Thomas R, Roger VL, Somers VK, Lopez-Jimenez F. Central obesity and survival in subjects with coronary artery disease: a systematic review of the literature and collaborative analysis with individual subject data. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:1877–1886. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.11.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Després JP, Lemieux I, Bergeron J, Pibarot P, Mathieu P, Larose E, Rodés-Cabau J, Bertrand OF, Poirier P. Abdominal obesity and the metabolic syndrome: contribution to global cardiometabolic risk. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:1039–1049. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.159228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Arner P. Not all fat is alike. Lancet. 1998;351:1301–1302. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)79052-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Bergman RN, Kim SP, Catalano KJ, Hsu IR, Chiu JD, Kabir M, Hucking K, Ader M. Why visceral fat is bad: mechanisms of the metabolic syndrome. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006;14:16S–19S. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Sniderman AD, Bhopal R, Prabhakaran D, Sarrafzadegan N, Tchernof A. Why might South Asians be so susceptible to central obesity and its atherogenic consequences? The adipose tissue overflow hypothesis. Int J Epidemiol. 2007;36:220–225. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyl245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Ibrahim MM. Subcutaneous and visceral adipose tissue: structural and functional differences. Obes Rev. 2010;11:11–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2009.00623.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Canoy D, Wareham N, Luben R, Welch A, Bingham S, Day N, Khaw KT. Serum lipid concentration in relation to anthropometric indices of central and peripheral fat distribution in 20.021 British men and women: results from the EPIC-Norfolk population-based cohort study. Atherosclerosis. 2006;189:420–427. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ounpuu S, Bautista L, Franzosi MG, Commerford P, Lang CC, Rumboldt Z, Onen CL, Lisheng L, Tanomsup S, Wangai P, Jr, Razak F, Sharma AM, Anand SS, INTERHEART Study Investigators Obesity and the risk of myocardial infarction in 27,000 participants from 52 countries: a case-control study. Lancet. 2005;366:1640–1649. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67663-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Dalton M, Cameron AJ, Zimmet PZ, Shaw JE, Jolley D, Dunstan DW, Welborn TA, AusDiab Steering Committee Waist circumference, waist-hip ratio and body mass index and their correlation with cardiovascular disease risk factors in Australian adults. J Intern Med. 2003;254:555–563. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2003.01229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Snijder MB, Dekker JM, Visser M, Bouter LM, Stehouwer CDA, Yudkin JS, Heine RJ, Nijpels G, Seidell JC. Trunk fat and leg fat have independent and opposite associations with fasting and postload glucose levels. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:372–377. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.2.372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Tanko LB, Bagger YZ, Alexandersen P, Larsen PJ, Christiansen C. Central and peripheral fat mass have contrasting effect on the progression of aortic calcification in postmenopausal women. Eur Heart J. 2003;24:1531–1537. doi: 10.1016/s0195-668x(03)00319-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Wu H, Qi Q, Yu Z, Sun Q, Wang J, Franco OH, Sun L, Li H, Liu Y, Hu FB, Lin X. Independent and opposite associations of trunk and leg fat depots with adipokines, inflammatory markers, and metabolic syndrome in middle-aged and older Chinese men and women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:4389–4398. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-0181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Thinggaard M, Jacobsen R, Jeune B, Martinussen T, Christensen K. Is the relationship between BMI and mortality increasingly U-shaped with advancing age? A 10-year follow-up of persons aged 70-95 years. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2010;65:526–531. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glp214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Zamboni M, Mazzali G, Fantin F, Rossi A, Di Francesco V. Sarcopenic obesity: a new category of obesity in the elderly. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2008;18:388–395. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2007.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Martin AD, Daniel M, Clarys JP, Marfell-Jones MJ. Cadaver-assessed validity of anthropometric indicators of adipose tissue distribution. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003;27:1052–1058. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Pouliot MC, Després JP, Lemieux S, Moorjani S, Bouchard C, Tremblay A, Nadeau A, Lupien PJ. Waist circumference and abdominal sagittal diameter: best simple anthropometric indexes of abdominal visceral adipose tissue accumulation and related cardiovascular risk in men and women. Am J Cardiol. 1994;73:460–468. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(94)90676-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Molarius A, Seidell JC. Selection of anthropometric indicators for classification of abdominal fatness--a critical review. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1998;22:719–727. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].National Institutes of Health. Clinical Guidelines on the Identification, Evaluation, and Treatment of Overweight and Obesity in Adults--The Evidence Report. Obes Res. 1998;6:51S–209S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Gallagher D, Heymsfield SB, Heo M, Jebb SA, Murgatroyd PR, Sakamoto Y. Healthy percentage body fat ranges: an approach for developing guidelines based on body mass index. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;72:694–701. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/72.3.694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Clarys JP, Scafoglieri A, Provyn S, Bautmans I. Body mass index as a measure of bone mass. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2010;50:202–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Scafoglieri A, Provyn S, Bautmans I, Wallace J, Sutton L, Tresignie J, Louis O, De Mey J, Clarys JP. Vadursi M, editor. Critical appraisal of data acquisition in body composition: evaluation of methods, techniques and technologies on the anatomical tissue-system level. Data Acquisition. 2010. pp. 281–312. Reijka: Sciyo.

- [56].Scafoglieri A, Provyn S, Bautmans I, Van Roy P, Clarys JP. Direct relationship of body mass index and waist circumference with body tissue distribution in elderly persons. J Nutr Health Aging. 2011;15:924–931. doi: 10.1007/s12603-010-0272-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Romero-Corral A, Somers VK, Sierra-Johnson J, Jensen MD, Thomas RJ, Squires RW, Allison TG, Korinek J, Lopez-Jimenez F. Diagnostic performance of body mass index to detect obesity in patients with coronary artery disease. Eur Heart J. 2007;28:2087–2093. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Romero-Corral A, Somers VK, Sierra-Johnson J, Thomas RJ, Collazo-Clavell ML, Korinek J, Allison TG, Batsis JA, Sert-Kuniyoshi FH, Lopez-Jimenez F. Accuracy of body mass index in diagnosing obesity in the adult general population. Int J Obes (Lond) 2008;32:959–966. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Romero-Corral A, Somers VK, Sierra-Johnson J, Korenfeld Y, Boarin S, Korinek J, Jensen MD, Parati G, Lopez-Jimenez F. Normal weight obesity: a risk factor for cardiometabolic dysregulation and cardiovascular mortality. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:737–746. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Scafoglieri A, Provyn S, Bautmans I, Tresignie J, Clarys JP. Individual body tissue distribution varies considerably within and between adjacent BMI classifications in the elderly. In: Vermeulen A, Desmet E, editors. New trends in body mass index research. Novapublishers; 2012. pp. 59–80. [Google Scholar]

- [61].Piers LS, Soares MJ, Frandsen SL, O’Dea K. Indirect estimates of body composition are useful for groups but unreliable in individuals. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2000;24:1145–1152. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Rankinen T, Kim SY, Pérusse L, Després JP, Bouchard C. The prediction of abdominal visceral fat level from body composition and anthropometry: ROC analysis. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1999;238:801–809. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Berentzen TL, Ängquist L, Kotronen A, Borra R, Yki-Järvinen H, Iozzo P, Parkkola R, Nuutila P, Ross R, Allison DB, Heymsfield SB, Overvad K, Sørensen TI, Jakobsen MU. Waist circumference adjusted for body mass index and intra-abdominal fat mass. PLoS One. 2012;7:e32213. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Yim JY, Kim D, Lim SH, Park MJ, Choi SH, Lee CH, Kim SS, Cho SH. Sagittal abdominal diameter is a strong anthropometric measure of visceral adipose tissue in the Asian general population. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:2665–2670. doi: 10.2337/dc10-0606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Burton RF. Waist circumference as an indicator of adiposity and the relevance of body height. Med Hypotheses. 2010;75:115–119. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2010.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Oka R, Miura K, Sakurai M, Nakamura K, Yagi K, Miyamoto S, Moriuchi T, Mabuchi H, Yamagishi M, Takeda Y, Hifumi S, Inazu A, Nohara A, Kawashiri MA, Kobayashi J. Comparison of waist circumference with body mass index for predicting abdominal adipose tissue. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2009;83:100–105. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Bosy-Westphal A, Booke CA, Blöcker T, Kossel E, Goele K, Later W, Hitze B, Heller M, Glüer CC, Müller MJ. Measurement site for waist circumference affects its accuracy as an index of visceral and abdominal subcutaneous fat in a Caucasian population. J Nutr. 2010;140:954–961. doi: 10.3945/jn.109.118737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Lapidus L, Bengtsson C, Larsson B, Pennert K, Rybo E, Sjöström L. Distribution of adipose tissue and risk of cardiovascular disease and death: a 12 year follow up of participants in the population study of women in Gothenburg, Sweden. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1984;289:1257–1261. doi: 10.1136/bmj.289.6454.1257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Lemieux S, Després JP, Moorjani S, Nadeau A, Thériault G, Prud’homme D, Tremblay A, Bouchard C, Lupien PJ. Are gender differences in cardiovascular disease risk factors explained by the level of visceral adipose tissue? Diabetologia. 1994;37:757–764. doi: 10.1007/BF00404332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Imbeault P, Lemieux S, Prud’homme D, Tremblay A, Nadeau A, Després JP, Mauriège P. Relationship of visceral adipose tissue to metabolic risk factors for coronary heart disease: is there a contribution of subcutaneous fat cell hypertrophy? Metabolism. 1999;48:355–362. doi: 10.1016/s0026-0495(99)90085-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Wajchenberg BL. Subcutaneous and visceral adipose tissue: their relation to the metabolic syndrome. Endocr Rev. 2000;21:697–738. doi: 10.1210/edrv.21.6.0415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Hsieh S, Yoshinaga H. Do people with similar waist circumference share similar health risks irrespective of height? Tohoku J Exp Med. 1999;188:55–60. doi: 10.1620/tjem.188.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Wells JC. Sexual dimorphism of body composition. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;21:415–430. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2007.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Daniel M, Martin AD, Drinkwater DT, Clarys JP, Marfell-Jones MJ. Waist-to-hip ratio and adipose tissue distribution: contribution of subcutaneous adiposity. Am J Hum Biol. 2003;15:428–432. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.10165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Heyward VH, Stolarczyk LM, editors. Applied Body composition assessment. Human Kinetics; Champaign IL: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- [76].Bonora E, Micciolo R, Ghiatas AA, Lancaster JL, Alyassin A, Muggeo M, DeFronzo RA. Is it possible to derive a reliable estimate of human visceral and subcutaneous abdominal adipose tissue from simple anthropometric measurements? Metabolism. 1995;44:1617–1625. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(95)90084-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Dobbelsteyn CJ, Joffres MR, MacLean DR, Flowerdew G. A comparative evaluation of waist circumference, waist-to-hip ratio and body mass index as indicators of cardiovascular risk factors. The Canadian Heart Health Surveys Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2001;25:652–661. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Cameron AJ, Magliano DJ, Shaw JE, Zimmet PZ, Carstensen B, Alberti KG, Tuomilehto J, Barr EL, Pauvaday VK, Kowlessur S, Söderberg S. The influence of hip circumference on the relationship between abdominal obesity and mortality. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41:484–494. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyr198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Petursson H, Sigurdsson JA, Bengtsson C, Nilsen TI, Getz L. Body configuration as a predictor of mortality: comparison of five anthropometric measures in a 12 year follow-up of the Norwegian HUNT 2 study. PLoS One. 2011;6:e26621. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Ashwell M. Obesity risk: importance of the waist-to-height ratio. Nurs Stand. 2009;23:49–54. doi: 10.7748/ns2009.06.23.41.49.c7050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Ludescher B, Rommel M, Willmer T, Fritsche A, Schick F, Machann J. Subcutaneous adipose tissue thickness in adults - correlation with BMI and recommendations for pen needle lengths for subcutaneous self-injection. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2011;75:786–790. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2011.04132.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Springer F, Ehehalt S, Sommer J, Ballweg V, Machann J, Binder G, Claussen CD, Schick F, DISKUS-Study Group Predicting volumes of metabolically important whole-body adipose tissue compartments in overweight and obese adolescents by different MRI approaches and anthropometry. Eur J Radiol. 2012;81:1488–1494. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2011.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Chan DC, Watts GF, Barrett PH, Burke V. Waist circumference, waist-to-hip ratio and body mass index as predictors of adipose tissue compartments in men. QJM. 2003;96:441–447. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcg069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Wang J, Thornton JC, Kolesnik S, Pierson RN., Jr Anthropometry in body composition. An overview. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2000;904:317–326. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06474.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Provyn S, Wallace J, Scafoglieri A, Sesboüé B, Marfell-Jones M, Bautmans I, Clarys JP. Adipose tissue prediction equations in women – quality control [Formules de prediction de l’adiposité chez la femme – contrôle de qualité] Sci Sport. 2010;25:291–303. [Google Scholar]

- [86].Provyn S, Scafoglieri A, Tresignie J, Bautmans I, Reilly T, Clarys JP. Quality control of 157 whole body adiposity prediction formulae in age and activity matched men. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2011;51:426–434. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Clarys JP, Marfell-Jones MJ. Anthropometric prediction of component tissue masses in the minor limb segments of the human body. Hum Biol. 1986;58:761–769. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Clarys JP, Marfell-Jones MJ. Soft tissue segmentation of the body and fractionation of the upper and lower limbs. Ergonomics. 1994;37:217–229. doi: 10.1080/00140139408963640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Shen W, Wang Z, Punyanita M, Lei J, Sinav A, Kral JG, Imielinska C, Ross R, Heymsfield SB. Adipose tissue quantification by imaging methods: a proposed classification. Obes Res. 2003;11:5–16. doi: 10.1038/oby.2003.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Larsson B, Bengtsson C, Björntorp P, Lapidus L, Sjöström L, Svärdsudd K, Tibblin G, Wedel H, Welin L, Wilhelmsen L. Is abdominal body fat distribution a major explanation for the sex difference in the incidence of myocardial infarction? The study of men born in 1913 and the study of women, Göteborg, Sweden. Am J Epidemiol. 1992;135:266–273. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Seidell JC, Oosterlee A, Thijssen MA, Burema J, Deurenberg P, Hautvast JG, Ruijs JH. Assessment of intra-abdominal and subcutaneous abdominal fat: relation between anthropometry and computed tomography. Am J Clin Nutr. 1987;45:7–13. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/45.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Han TS, McNeill G, Seidell JC, Lean ME. Predicting intra-abdominal fatness from anthropometric measures: the influence of stature. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1997;21:587–593. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Lemieux S, Prud’homme D, Bouchard C, Tremblay A, Després JP. Sex differences in the relation of visceral adipose tissue accumulation to total body fatness. Am J Clin Nutr. 1993;58:463–467. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/58.4.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Kvist H, Chowdhury B, Grangård U, Tylén U, Sjöström L. Total and visceral adipose-tissue volumes derived from measurements with computed tomography in adult men and women: predictive equations. Am J Clin Nutr. 1988;48:1351–1361. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/48.6.1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Kekes-Szabo T, Hunter GR, Nyikos I, Nicholson C, Snyder S, Berland L. Development and validation of computed tomography derived anthropometric regression equations for estimating abdominal adipose tissue distribution. Obes Res. 1994;2:450–457. doi: 10.1002/j.1550-8528.1994.tb00092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Kekes-Szabo T, Hunter GR, Nyikos I, Williams M, Blaudeau T, Snyder S. Anthropometric equations for estimating abdominal adipose tissue distribution in women. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1996;20:753–758. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Schreiner PJ, Terry JG, Evans GW, Hinson WH, Crouse JR, 3rd, Heiss G. Sex-specific associations of magnetic resonance imaging-derived intra-abdominal and subcutaneous fat areas with conventional anthropometric indices. The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Am J Epidemiol. 1996;144:335–345. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a008934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Ferland M, Després JP, Tremblay A, Pinault S, Nadeau A, Moorjani S, Lupien PJ, Thériault G, Bouchard C. Assessment of adipose tissue distribution by computed axial tomography in obese women: association with body density and anthropometric measurements. Br J Nutr. 1989;61:139–148. doi: 10.1079/bjn19890104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Weits T, van der Beek EJ, Wedel M, Ter Haar Romeny BM. Computed tomography measurement of abdominal fat deposition in relation to anthropometry. Int J Obes. 1988;12:217–225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]