Significance

Oceanic dissolved organic carbon (DOC) contains as much carbon as Earth’s atmosphere, yet its cycling timescales and composition remain poorly constrained. We use serial oxidation experiments to measure the quantitative distribution of carbon isotopes inside the DOC reservoir, allowing us to estimate both its cycling timescales and source distribution. We find that a large portion of deep water DOC has a modern radiocarbon age and a fast turnover time supported by particle dissolution. In addition, stable carbon isotopes allow for diverse sources of carbon, besides microbial production, to quantitatively feed this reservoir. Our work suggests a DOC cycle that is far more intricate, and potentially variable on shorter timescales, than previously envisioned.

Keywords: carbon cycle, carbon isotopes, dissolved organic carbon, radiocarbon, oceanography

Abstract

Marine dissolved organic carbon (DOC) is a large (660 Pg C) reactive carbon reservoir that mediates the oceanic microbial food web and interacts with climate on both short and long timescales. Carbon isotopic content provides information on the DOC source via δ13C and age via Δ14C. Bulk isotope measurements suggest a microbially sourced DOC reservoir with two distinct components of differing radiocarbon age. However, such measurements cannot determine internal dynamics and fluxes. Here we analyze serial oxidation experiments to quantify the isotopic diversity of DOC at an oligotrophic site in the central Pacific Ocean. Our results show diversity in both stable and radio isotopes at all depths, confirming DOC cycling hidden within bulk analyses. We confirm the presence of isotopically enriched, modern DOC cocycling with an isotopically depleted older fraction in the upper ocean. However, our results show that up to 30% of the deep DOC reservoir is modern and supported by a 1 Pg/y carbon flux, which is 10 times higher than inferred from bulk isotope measurements. Isotopically depleted material turns over at an apparent time scale of 30,000 y, which is far slower than indicated by bulk isotope measurements. These results are consistent with global DOC measurements and explain both the fluctuations in deep DOC concentration and the anomalous radiocarbon values of DOC in the Southern Ocean. Collectively these results provide an unprecedented view of the ways in which DOC moves through the marine carbon cycle.

Radiocarbon is a natural tracer of carbon flow through dissolved organic carbon (DOC) (1). As plankton grow and are consumed by grazers, organic matter with a modern radiocarbon value is released into surface waters where it accumulates as semilabile DOC (2–4). Semilabile DOC undergoes net remineralization below the euphotic zone and gradually diminishes in concentration with depth to approximately 1,000 m, below which it appears to vanish. Oceanic profiles of total DOC and DOC radiocarbon (DOC) are therefore characterized by high values (60–80 μM carbon; to ) in surface waters and lower values at depth (35–40 μM; to ) (2). The to ‰ depletion in DOC values in surface seawater relative to semilabile DOC indicates the presence of a second refractory DOC fraction with an old radiocarbon age. The inverse proportionality between DOC concentration and radiocarbon value in depth profiles suggests that refractory DOC is well mixed throughout the entire water column (2, 3, 5, 6). The origin of the refractory DOC fraction is obscure, but stable isotopes show little change with depth (2, 7–9), indicating a common, autochthonous planktonic source for both fractions (2).

DOC and DOC profiles can be reproduced in a simple two-component model (TCM) that includes a variable amount of semilabile DOC cycling in the upper ocean (<1,000 m) superimposed on a ubiquitous background of radiocarbon-depleted refractory DOC (2, 3). In the TCM, semilabile DOC cycles on timescales of months to years, whereas refractory DOC cycles over several millennia (2, 3, 10). The TCM provides an excellent 1D representation of DOC and isotope values in seawater.

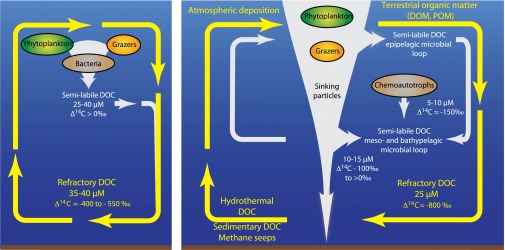

The simple mixing of two isotopically distinct components implicit in the TCM can be contrasted with the wide range of mass fluxes and isotope values measured in potential sources of marine DOC. These sources include terrestrial organic matter from C3 and C4 plants delivered by rivers (1, 4, 11), chemosynthetic organic matter from hydrothermal vent systems (12), organic matter derived from the oxidation of sedimentary methane (13), atmospheric deposition of black carbon from fossil fuel and biomass burning (14, 15), chemoautotrophy in the mesopelagic zone (16), and organic matter released from sinking particles (17–19). Together these sources represent a range of to , a range of 150 to , and a carbon flux of >3.5 Pg/y. It is unlikely that all of these sources are highly labile and nonaccumulating, and past studies have recognized that deep DOC is most likely a complex mixture of refractory carbon with a range of potential sources and cycling timescales (1, 4, 6, 8, 9, 11, 20). Evidence for the presence of a significant semilabile component within deep sea DOC is lacking (8). Simple isotope mass balance models have been used to explore relationships between the mass and isotopic value of components within deep sea DOC (6, 8), and efforts have been made to isolate DOC components for isotopic characterization (21, 22). Compound and class specific isotope analyses have shown diversity within a very small fraction of DOC, but these studies have not been able to connect specific isotope values to a corresponding inventory or mass flux. Studies based on bulk radiocarbon leave room for dynamic cycling, but with few exceptions (20, 23) conclude that the TCM is sufficient to explain their data. The discrepancy between the isotopic diversity in DOC sources and the narrow isotopic range of bulk DOC measurements has two resolutions. Either significant cycling of DOC is hidden by the TCM or many of these sources do not accumulate within the marine DOC reservoir. This paper provides a means for evaluating these two distinct hypotheses.

Materials and Methods

Samples were collected in July 2010 from Station ALOHA (22° 45′N; 158°W), site of the Hawaii Ocean Time-series (HOT) program. Whole seawater was frozen and returned to the National Ocean Sciences Accelerator Mass Spectrometer facility in Woods Hole, MA, for processing. Stepwise oxidation was performed using radiocarbon clean procedures on a customized, large volume UV apparatus. The total mass and mean isotopic value of DOC in surface, mid-depth, and deep seawater agrees with earlier results from a remote site in the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre (NPSG) used to establish the TCM (2, 3). The depletion in our surface water value, relative to those measured two decades ago, is due to the location of station ALOHA on the southern flank of the NPSG and the slow removal of bomb radiocarbon (radiocarbon produced during atmospheric testing of nuclear weapons) from the surface ocean over the last two decades (24). Further details can be found in SI Materials and Methods.

To estimate the isotopic distributions of components within DOC and quantify carbon fluxes that may be obscured by the TCM, we used the stepwise oxidation of DOC under high-intensity UV light (25, 26). Our experimental approach is not designed to mimic natural photo-oxidative processes. Rather, we use photo-oxidation as a tool to generate an isotopic time series of DOC components from which we derive evidence for a distribution of isotopic abundances among the components of DOC. Carbon from components that are readily oxidized by UV light will appear early in the time series, whereas carbon from components resistant to UV light will appear later, as oxidation proceeds to completion. The approach is analogous to using chemical oxidation techniques to remove a specific chemical fraction (22) or to using spatial gradients to infer internal distributions (5). These time series were modeled in terms of parallel first-order reactions to estimate the radiocarbon distribution (SI Materials and Methods and SI Text).

The Isotope Time Series

Fig. 1 shows the serial oxidation time series for our samples (numeric values in SI Text) and includes concentration, , , and . We use in our analysis rather than because our methods require linear isotope units. It should, however, be noted that the and the time series are similar, with the only substantial deviation being the final time point. was calculated using the and separately measured values. Time points were chosen to minimize mass differences between each fraction to equalize statistical errors and keep mass-dependent errors systematic (25). Mass values were blank corrected by subtracting the amount of carbon recovered at each time point from a separate time series using previously UV-oxidized seawater.

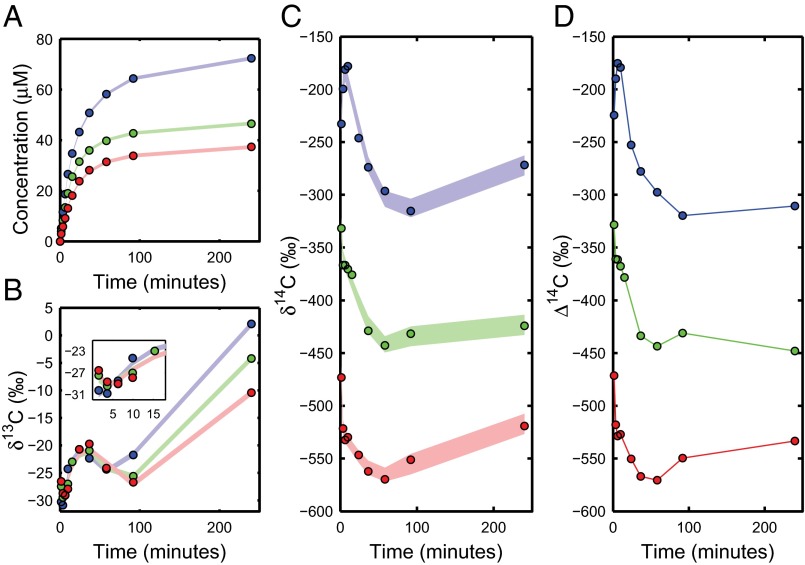

Fig. 1.

Oxidation data and fit. Time series showing cumulative mass oxidized per liter of seawater (A), along with the measured isotope values (B–D) of carbon dioxide generated at each time point during stepwise UV oxidation of Station ALOHA DOC. The isotope data is for (Inset shows decrease at early times) (B), (C), and (D). Samples are from 50- (blue), 500- (green), and 2,000-m (red) depths. The CIs for our component fit are shown by the shaded regions. The connecting line for the data is a guide for the eye, as these data are not suitable for our fitting procedure.

The structure of the isotope time series provides direct information on the isotopic composition of DOC. The time series has two local minima at all three depths suggesting at least three distinct fractions. One minimum occurs after approximately 5 min of total oxidation time (see data in SI Text to resolve early times), whereas the other occurs after nearly 90 min. The strong enrichment in values at the final time point results from isotopic fractionation during UV oxidation, with measured fractionation factors for small organic compounds being as great as (27). If this fractionation is taken into account, the intrinsic isotopic variations underlying the fluctuations at all three depths must still be at least . Taking into account the attenuation caused by mixing of multiple components, this range allows for significant contributions to deep water DOC from terrestrial organic matter, black carbon, hydrothermal vents, and methane seeps. Exceptionally efficient sinks for these external sources of carbon are not required.

Fractionation is less relevant for as the dynamic range is 10 times larger than for . For the time series, the local extremal values, along with the decreasing trend, also suggest three isotopic groups with a minimal spread of , , and for the surface, mid-depth, and deep water, respectively. However, the large changes in (Fig. 1D) over relatively short periods of time suggest DOC components with a much larger isotopic range. To estimate the full radiocarbon range, we require a kinetic model for oxidation under UV light.

Modeling the Radiocarbon Distribution

The oxidation of DOC by UV light has been modeled as both a parallel first-order (25) and second-order kinetic process (26). For parallel first-order processes, the initial oxidation rate will scale linearly with DOC concentration, whereas second-order kinetics predicts that the initial decay rate scales quadratically with DOC concentration. To directly test the kinetic form, we performed serial oxidation experiments under multiple dilutions of filtered Woods Hole seawater and showed that the initial decay rate scales linearly with concentration (28). Therefore, DOC photo-oxidation in our high-intensity apparatus is best described by parallel first-order kinetics rather than second-order kinetics (26) (SI Text).

To estimate the isotopic values of the different DOC components, we therefore represent the oxidation progression as a superposition of parallel first-order reactions (29)

| [1] |

The function is the amount of iC, where , remaining in the DOC sample after a time t; and is the amount of iC associated with a first-order rate constant between k and . After correcting for isotopic fractionation, the relevant isotopic ratios are . The isotopic ratios along with the concentration as a function of rate constant allow us to estimate the distribution of isotopic values. This estimate is made by matching concentrations with isotopic ratios through their common rate constants.

To render the problem numerically tractable, we approximate the integral as a sum of n discrete components

| [2] |

where the doubly subscripted and are the fractionation factor and initial concentration, respectively, of the jth component of iC. We solve for the parameter values that minimize the error between our model and the serial oxidation data. Independent of fractionation, each inflection point in the isotope time series suggests an additional required component, leading to six (three each from the inflection points in the and time series). We thus compute the best fit solution using six exponential components, constraining the solution to fall within measured isotopic values of marine organic matter at each depth (; ). Unlike earlier radiocarbon mixing models, which assume end member values or infer them from plots, the approach taken here is to let all of the parameters vary until an optimal fit to the concentration, , and time series is obtained. As high-parameter, nonlinear fits are sensitive to noise, we use a Monte-Carlo approach, repeating the procedure on many (1,000) realizations of the data by perturbing the original data with random error and look for general patterns in isotope space for all 1,000 sets of mass and isotope pairs (6,000 pairs). The mass estimates are not tied to the number of exponential components used in the fitting procedure. The ensuing mass and DOC values were grouped into modern , depleted , and highly depleted fractions. The estimated isotope distributions (Fig. 2) show the average concentration density (micromoles of DOC per liter of seawater divided by the isotope range of each interval) estimate within each fraction. The concentration of DOC in each of the three fractions is equal to the area under each bar in Fig. 2 (value in micromolar given above each bar). Further technical details can be found in SI Text.

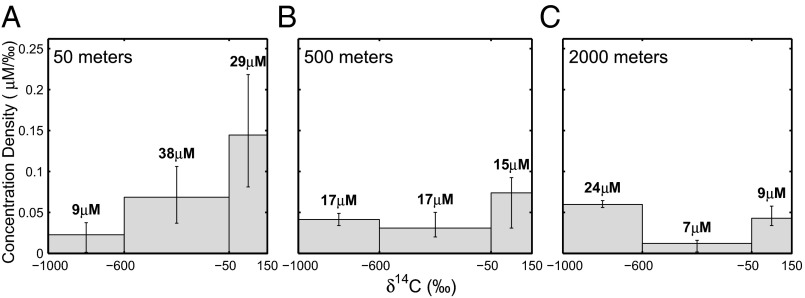

Fig. 2.

Radiocarbon composition of DOC, expressed as a scaled probability distribution. The estimated isotopic distributions for 50- (A), 500- (B), and 2,000-m (C) depths. The area under each bar corresponds to the average concentration of the modern , depleted , and highly depleted fractions. Error bars are the and percentiles of our estimate for that fraction. Bold values above each bar are the concentration (μM) values (area of each bar). For example, our plot for 2,000 m suggests that approximately 24 μM is highly depleted, 7 μM is depleted, and 9 μM modern organic carbon make up DOC at that depth.

DOC for all samples includes modern , depleted (; ), and highly depleted (; ) DOC, where is the lowest radiocarbon value found in deep Pacific water. The broad range of DOC values for the depleted and highly depleted DOC suggests a wide range of turnover times for these fractions. Surface seawater at Station ALOHA contains approximately 29 μM radiocarbon modern DOC, which decreases in concentration to 15 μM at 500 m and 9 μM at 2,000 m. The high relative abundance ( total DOC) and enriched isotope values of modern DOC limits the resolution of depleted and highly depleted fractions in our surface and mid-depth samples. The higher total amount of depleted and highly depleted carbon at the surface (∼47 μM) relative to 500 and 2,000 m (∼34 and 31 μM, respectively) could be due in part to inputs of depleted atmospheric and riverine carbon, but is most likely due to limitations in the resolution of isotope values by our measurements and model. This interpretation is consistent with the values for highly depleted carbon, which appear to increase with depth from less than 10 μM at 50 m to ∼15 μM at 500 m and ∼24 μM at 2,000 m. Our separation between the highly depleted and modern fractions becomes better with decreasing concentration and bulk radiocarbon value.

Radiocarbon and DOC Cycling

The persistence of modern DOC at all depths requires a decoupling of DOC cycling from the advective transport of water masses through the ocean’s interior (Fig. 3). In surface water, the radiocarbon modern fraction has a value consistent with the value of surface water dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC), supporting autochthonous production by marine microbes. At depth, this fraction has a value , decoupling its source from either in situ production by chemoautotrophy or advection from high latitudes, both of which would impart an isotopic value equal to DIC. The dissolution of sinking particles provides a straightforward mechanism to transfer radiocarbon modern material to the deep ocean (17). Global shallow export production estimated from sediment trap measurements and ocean models is approximately 11 Pg C/y, with between 2.3 and 5.5 Pg C/y falling through 500 m (30, 31). The modern radiocarbon value of ∼10 μM of deep DOC suggests that this material has a turnover timescale less than 50 y and is thus semilabile. If deep, semilabile DOC is in a steady state governed by first-order kinetics, at least 1 Pg C/y flows through this fraction. Our measurements therefore suggest that 20–50% of sinking particulate organic matter is solubilized during export and sequestered for decadal time scales as semilabile DOC within the deep ocean. The carbon flux through deep semilabile DOC is one to two orders of magnitude higher than the flux through DOC calculated from bulk radiocarbon values and dominates the carbon flux through deep sea DOC.

Fig. 3.

Physical interpretation. Schematic contrasting DOC cycling in the two-component model (Left) and the multicomponent model proposed here (Right). In the two-component model, DOC with a modern radiocarbon value is added to surface seawater as a byproduct of microbial carbon production and cycling, such that surface DOC concentrations are relatively high (typically 60–80 μM) and enriched in radiocarbon ( to ). The semilabile component of DOC (25–40 μM; ) is removed in the mesopelagic ocean, leaving a background fraction of refractory DOC (35–40 μM; to ) that cycles through the ocean over several millennia. Our results (Right) show that a large fraction of the sinking particle flux through 500 m, with a modern radiocarbon value from to , accumulates in the deep ocean where it cycles over decadal timescales through the meso- and bathypelagic microbial loops. Chemo- and lithoautotrophy, as well as advection, also contribute to deep semilabile DOC. The refractory fraction of DOC (yellow arrow) has a lower concentration and older mean radiocarbon age than predicted by the TCM. The direct input of refractory carbon, or microbial cycling of semilabile carbon from terrestrial organic matter (atmospheric deposition, rivers, groundwater, desorption from particulate POC), hydrothermal vents, methane, and fossil carbon from seeps, sediments, and the atmosphere is consistent with stable carbon isotopic distributions.

The depleted DOC fraction would include contributions from in situ chemoautotrophy, chemolithotrophy (16, 20, 32), and the advection of DOC from higher latitudes (33–35). It is also likely that some modern and highly depleted carbon is not fully resolved in our measurements and therefore contributes to the depleted fraction. Highly depleted DOC is near 25 μM and at 2,000 m. This fraction is significantly depleted relative to the mean value for DOC in the deep ocean ( vs. , respectively) (2), suggesting a radiocarbon age near 12,000 y. Current models suggest that this refractory portion of DOC survives multiple ocean mixing cycles and is in an approximate steady state with modern inputs.

In this case, it is important to realize that the radiocarbon age does not equate to the mean age of the DOC. When a reservoir containing a single component with turnover time τ is in steady state, its mean age equals its turnover time, and the age distribution is exponential (36). Similar reasoning leads to the following relationship between the radiocarbon age of the reservoir and its turnover time τ (SI Text)

| [3] |

where λ is the decay constant of radiocarbon. Inserting y, we calculate the turnover time τ to be 30,000 y for refractory DOC. This time scale suggests either DOC cycling takes much longer than the currently believed 6,000 y (3) or that an external source of isotopically depleted (pre-aged and potentially labile) carbon supports the refractory DOC.

Global Context

The current form of the TCM is sufficient to explain many open ocean DOC measurements. Chief among its accomplishments are an explanation for the depleted radiocarbon values found in surface ocean DOC and the slow decrease in DOC concentration between the deep North Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. The fundamental tenet of the TCM, that radiocarbon-depleted DOC persists throughout the water column, is well supported by our data. However, certain measurements remain hard to explain unless one allows for a semilabile reservoir of DOC in the deep ocean.

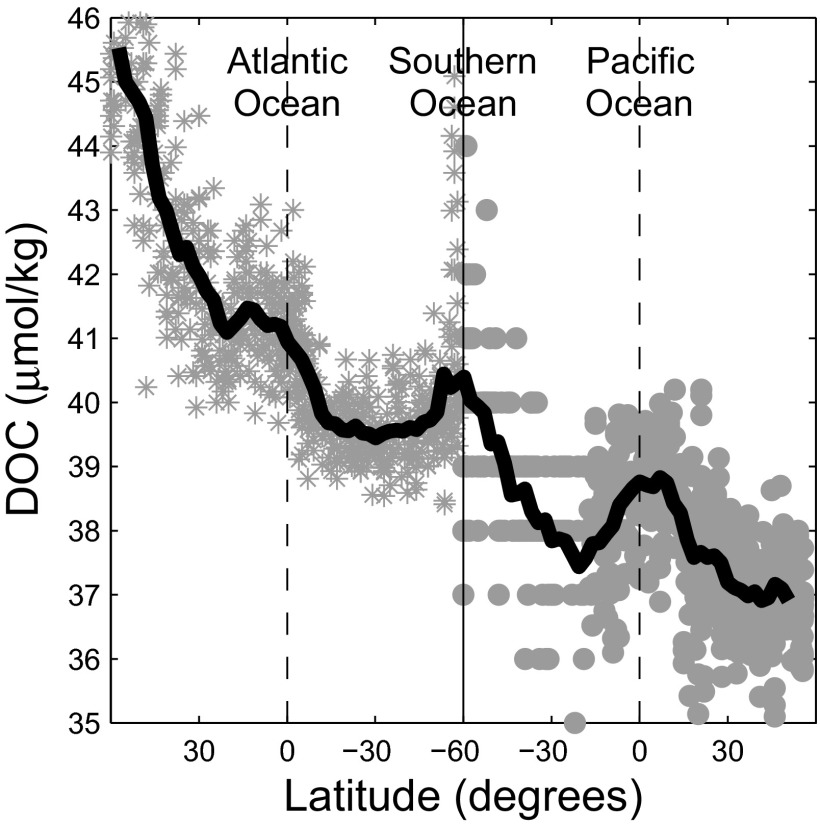

DOC concentrations in the deep ocean for a nominal global ocean transit (Fig. 4) show a general decrease consistent with the slow decay models used to explain them (33). These models use a superposition of material with different first-order decay rates to explain the slowdown of net DOC degradation in the ocean. Decay in these model systems is completely monotonic and fails to accommodate increases in either bulk DOC concentration or decay rate. Deep ocean transfer of particulate organic carbon (POC) into the DOC reservoir predicts that in areas of higher export production there should be local elevations in deep sea DOC concentrations due to a larger reservoir of semilabile DOC. Global DOC data plotted along density surfaces (34) as it travels from the North Atlantic to the North Pacific Ocean (Fig. 4) provide evidence for these systematic fluctuations. In equatorial regions and the Southern Ocean, we find increases in DOC concentration of 1–2 μM or of the semilabile reservoir. Post-nuclear bomb testing radiocarbon values for the deep semilabile reservoir of DOC suggest a turnover time of y for this portion. Any large impulse of semilabile DOC should thus persist over 15°–20° N-S based on a mean drift in the deep ocean of 0.3°–0.4° per year, which is consistent with the observed spatial fluctuations in deep DOC concentrations (Fig. 4). A recent reanalysis of deep Pacific data provides additional evidence that loss of refractory DOC is not a gradual, monotonic process but is localized to mid-depth regions in the North and South Pacific basins (37). Spatial differences in deep transport or release of semilabile DOC could result in the lowered observed DOC concentrations in these regions.

Fig. 4.

Changes in DOC concentration (micromoles per kilogram). DOC (34) in the core of the North Atlantic Deep Water along Atlantic transect A16 (*) and in the Circumpolar Deep Water along Pacific transect P16 . Water samples were used from the neutral density surfaces consistent with these water masses: in the Atlantic and in the Pacific (34). The running mean across N-S (solid line) is superimposed on the individual DOC measurements (single points). The 1- to 2-μM increase in DOC at the equator relative to the background trend in both basins is consistent with increased particle export from enhanced primary production at the equator. Data from cdiac.esd.ornl.gov/oceans/RepeatSections/.

A continual supply of semilabile DOC into the deep ocean from the sinking of large particles should also drive regional fluctuations in deep DOC values. The turnover time of semilabile DOC in surface waters is short relative to radioactive decay so that semilabile . DIC values can therefore be used as a proxy for semilabile DOC (2, 8). Large latitudinal changes in surface water DIC (and hence semilabile DOC) (1) should affect deep sea DOC values as semilabile organic matter is cycled through the deep DOC reservoir. This effect should be especially clear as one travels from the Sargasso Sea, through the Southern Ocean, and into the North Central Pacific. Along this journey, surface DIC ranges from in the North Atlantic to in the Southern Ocean and in the North Pacific (38). Assuming an average background concentration of refractory DOC at ∼25 μM and (Fig. 2), deep semilabile DOC would have a radiocarbon value of in the Sargasso Sea, in the Southern Ocean, and in the North Central Pacific, consistent with measured surface DIC values and trends.

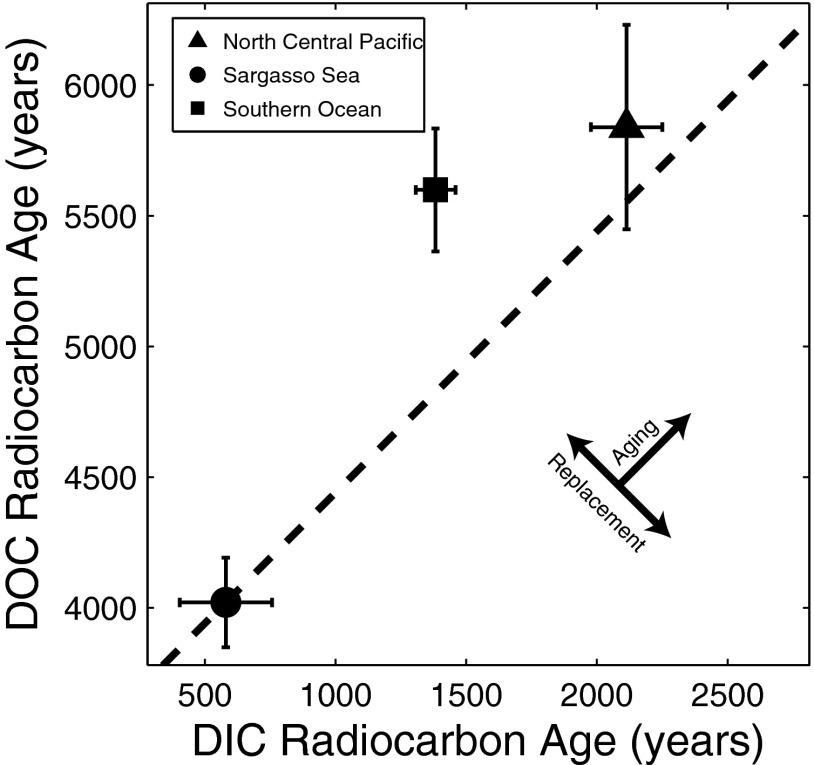

If DOC conservatively ages in the deep ocean, its radiocarbon age and that of DIC should change at the same rate. A plot of mean radiocarbon ages of deep water DOC and DIC (Fig. 5) in the Sargasso Sea (2), Southern Ocean (23), and North Central Pacific Ocean (2) shows that, although radiocarbon values in the North Pacific are consistent with conservative aging, the DOC in the Southern Ocean is 500–1,500 y too old (23). Compared with DIC, DOC ages more rapidly as water moves from the North Atlantic to the Southern Ocean and then more slowly as water moves from the Southern Ocean into the North Pacific (23). These trends are straightforwardly explained if semilabile DOC in the deep Sargasso Sea is replaced by surface derived, isotopically depleted, semilabile DOC in the Southern Ocean (more rapid apparent aging of DOC) and then replaced again by modern DOC in the deep North Pacific (slower apparent aging of DOC).

Fig. 5.

Bulk radioisotopes and the TCM: DOC radiocarbon age is plotted vs. DIC radiocarbon age for the deep (>1,000 m) North Central Pacific Ocean (2), Sargasso Sea (2), and Southern Ocean (23). Mean values are plotted where missing DIC radiocarbon values were linearly interpolated from the depth profile. Error bars represent SEM. Points on the dotted line are consistent with conservative aging of both DOC and DIC.

The current paradigm of DOC cycling assumes that the dynamics of DOC in the deep ocean are advectively controlled; that once photosynthetically derived DOC is exported from the surface, it undergoes purely degradative processes (33, 34). This assumption allows one to calculate the net DOC flux from deep concentration gradients and equate it with the gross carbon flux (33, 34). If the dissolution of POC supports a large, semilabile portion of deep DOC, however, then the gross flux is no longer calculable from deep sea gradients in DOC. Under this scenario, the dynamics of deep ocean DOC is affected by surface processes like primary and export production. In this case, the flux through the reservoir could be substantially higher. Regional changes in the global DOC concentration and radioisotope data support this perspective.

Carbon flux from POC to DOC could provide a unifying framework for DOC cycling in disparate environments. POC-DOC transfer from terrestrial sources are believed to affect the bulk DOC values in the Mid-Atlantic bight, Western North Pacific, and Arctic Ocean (7, 20, 39). Griffith et al. (20) used isotopic evidence to suggest that of deep DOC in Canada Basin water could be terrestrially derived, which would leave the background, refractory, marine-derived DOC fraction at a concentration of 28 μM, well below DOC values in the deep North Pacific but similar to the values determined by our measurements. This amount of background carbon requires that deep Pacific DOC (35–40 μM) contains 7–12 μM semilabile DOC. The Mediteranean Sea may also be unified within the POC-DOC framework. Although the turnover time for Mediteranean deep water is an order of magnitude less than in the global oceans (100s vs. 1,000s of years), deep DOC values reach those found in the North Central Pacific (40). Unique decay conditions may be present. However, low DOC values are consistent with the ultra-oligotrophic surface conditions and low inputs of deep semilabile DOC from particles (41).

Conclusion

The contrast between the large number of diverse sources that supply carbon to marine DOC and the isotopic uniformity measured in stable and radiocarbon analyses and inferred from the TCM has long been considered as a paradox in ocean carbon cycling. Our results show that marine DOC is isotopically diverse, with a broad range of potential sources and cycling timescales. Deep DOC has a range of at least 10‰, allowing for significant contributions from terrestrial organic matter, black carbon, DOC from hydrothermal sources, and methane seeps. Exceptionally efficient sinks for these external sources of carbon do not need to be invoked to explain the isotopic value of DOC in the deep sea. Furthermore, we suggest that the total flux of carbon through DOC in the deep ocean is at least an order of magnitude higher than the net carbon flux derived from abyssal concentration gradients (33) and bulk radiocarbon measurements (3). Current flux estimates that equate total flux with net flux assume that inputs from the dissolution of sinking particles and chemoautotrophy are small. Our data suggest otherwise. Active cycling of carbon and large annual carbon fluxes through DOC are not restricted to the surface ocean but occur throughout the water column (Fig. 3). Our work suggests a DOC cycle that is far more intricate, and potentially variable on shorter timescales, than previously envisioned.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank David Forney for advice concerning the extraction of kinetic information from a time series and Ann McNichol and S. Beaupré for lending experimental expertise. We further thank the entire staff at National Ocean Sciences Accelerator Mass Spectrometry for help with isotope measurements and Ben Van Mooy for the collection of our water samples. We acknowledge support from National Science Foundation (NSF) Grants OCE-0930866 and OCE-0930551. D.J.R. was supported in part by the NSF National Science and Technology Center for Microbial Oceanography Research and Education Grant CFF-424599 and by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation’s Marine Microbiology Initiative.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1407445111/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.McNichol AP, Aluwihare LI. The power of radiocarbon in biogeochemical studies of the marine carbon cycle: Insights from studies of dissolved and particulate organic carbon (DOC and POC) Chem Rev. 2007;107(2):443–466. doi: 10.1021/cr050374g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Druffel E, Williams P, Bauer J, Ertel J. Cycling of dissolved and particulate organic matter in the open ocean. J Geophys Res. 1992;97(C10):15639–15659. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williams P, Druffel E. Radiocarbon in dissolved organic matter in the central north pacific ocean. Nature. 1987;330(6145):246–248. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eglinton T, Repeta DJ. 2003. Organic matter in the contemporary ocean. Treatise on Geochemistry, eds Turekian K, Holland H (Elsevier, London), pp 145–180.

- 5.Mortazavi B, Chanton J. 2004. Use of keeling plots to determine sources of dissolved organic carbon in nearshore and open ocean systems. Limnology and Oceanography 49(1):102–108.

- 6.Beaupré S, Aluwihare L. Constraining the 2-component model of marine dissolved organic radiocarbon. Deep Sea Res Part II Top Stud Oceanogr. 2010;57(16):1494–1503. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tanaka T, Otosaka S, Wakita M, Amano H, Togawa O. Preliminary result of dissolved organic radiocarbon in the western north pacific ocean. Nucl Instrum Methods Phys Res B. 2010;268(7):1219–1221. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beaupré S, Druffel E. Constraining the propagation of bomb-radiocarbon through the dissolved organic carbon (doc) pool in the northeast Pacific Ocean. Deep Sea Res Part I Oceanogr Res Pap. 2009;56(10):1717–1726. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bauer JE, Reimers CE, Druffel ER, Williams PM. Isotopic constraints on carbon exchange between deep ocean sediments and sea water. Nature. 1995;373(6516):686–689. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carlson C, Ducklow H, Michaels A. Annual flux of dissolved organic carbon from the euphotic zone in the northwestern sargasso sea. Nature. 1994;371(6496):405–408. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raymond PA, Bauer JE. Use of and natural abundances for evaluating riverine, estuarine, and coastal doc and poc sources and cycling: A review and synthesis. Org Geochem. 2001;32(4):469–485. [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCarthy M, et al. Chemosynthetic origin of 14c-depleted dissolved organic matter in a ridge-flank hydrothermal system. Nat Geosci. 2011;4(1):32–36. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pohlman J, Bauer J, Waite W, Osburn C, Chapman N. Methane hydrate-bearing seeps as a source of aged dissolved organic carbon to the oceans. Nat Geosci. 2011;4(1):37–41. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Masiello CA, Druffel ERM. Black carbon in deep-Sea sediments. Science. 1998;280(5371):1911–1913. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5371.1911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuhlbusch T. Black carbon and the carbon cycle. Science. 1998;280(5371):1903. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ingalls AE, et al. Quantifying archaeal community autotrophy in the mesopelagic ocean using natural radiocarbon. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(17):6442–6447. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510157103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith D, Simon M, Alldredge A, Azam F. Intense hydrolytic enzyme activity on marine aggregates and implications for rapid particle dissolution. Nature. 1992;359(6391):139–142. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cho B, Azam F. Major role of bacteria in biogeochemical fluxes in the ocean’s interior. Nature. 1988;332(6163):441–443. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Druffel E, Bauer J, Williams P, Griffin S, Wolgast D. Seasonal variability of particulate organic radiocarbon in the northeast pacific ocean. J Geophys Res. 1996;101:20543–20. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Griffith DR, et al. Carbon dynamics in the western arctic ocean: Insights from full-depth carbon isotope profiles of dic, doc, and poc. Biogeosciences. 2012;9:1217–1224. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Loh AN, Bauer JE, Druffel ER. Variable ageing and storage of dissolved organic components in the open ocean. Nature. 2004;430(7002):877–881. doi: 10.1038/nature02780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Repeta D, Aluwihare L. 2006. Radiocarbon analysis of neutral sugars in high-molecular-weight dissolved organic carbon: Implications for organic carbon cycling. Limnology and Oceanography 51(2):1045–1053.

- 23.Druffel ER, Bauer JE. Radiocarbon distributions in southern ocean dissolved and particulate organic matter. Geophys Res Lett. 2000;27(10):1495–1498. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mahadevan A. An analysis of bomb radiocarbon trends in the pacific. Mar Chem. 2001;73(3):273–290. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beaupré S, Druffel E, Griffin S. A low-blank photochemical extraction system for concentration and isotopic analyses of marine dissolved organic carbon. Limnol Oceanogr Methods. 2007;5:174–184. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beaupré SR, Druffel ER. Photochemical reactivity of ancient marine dissolved organic carbon. Geophys Res Lett. 2012;39(18):L18602. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oba Y, Naraoka H. Carbon and hydrogen isotopic fractionation of low molecular weight organic compounds during ultraviolet degradation. Org Geochem. 2008;39(5):501–509. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tombari E, Salvetti G, Ferrari C, Johari GP. Kinetics and thermodynamics of sucrose hydrolysis from real-time enthalpy and heat capacity measurements. J Phys Chem B. 2007;111(3):496–501. doi: 10.1021/jp067061p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Forney DC, Rothman DH. Common structure in the heterogeneity of plant-matter decay. J R Soc Interface. 2012;9(74):2255–2267. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2012.0122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Laws E, Falkowski P, Smith W, Ducklow H, McCarthy J. Temperature effects on export production in the open ocean. Global Biogeochem Cycles. 2000;14(4):1231–1246. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Buesseler KO, et al. Revisiting carbon flux through the ocean’s twilight zone. Science. 2007;316(5824):567–570. doi: 10.1126/science.1137959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Swan BK, et al. Potential for chemolithoautotrophy among ubiquitous bacteria lineages in the dark ocean. Science. 2011;333(6047):1296–1300. doi: 10.1126/science.1203690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hansell D, Carlson C, Schlitzer R. Net removal of major marine dissolved organic carbon fractions in the subsurface ocean. Global Biogeochem Cycles. 2012;26(1):GB1016. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hansell D, Carlson C, Repeta D, Schlitzer R. Dissolved organic matter in the ocean: A controversy stimulates new insights. Oceanography (Wash DC) 2009;22(4):32–36. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hansell D, Carlson C. Deep-ocean gradients in the concentration of dissolved organic carbon. Nature. 1998;395(6699):263–266. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bolin B, Rodhe H. A note on the concepts of age distribution and transit time in natural reservoirs. Tellus. 1973;25(1):58–62. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hansell DA, Carlson CA. Localized refractory dissolved organic carbon sinks in the deep ocean. Global Biogeochem Cycles. 2013;27(3):705–710. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Key RM, et al. A global ocean carbon climatology: Results from global data analysis project (GLODAP) Global Biogeochem Cycles. 2004;18(GB4031):1–23. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bauer JE, Druffel ER. Ocean margins as a significant source of organic matter to the deep open ocean. Nature. 1998;392(6675):482–485. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Santinelli C, Nannicini L, Seritti A. Doc dynamics in the meso and bathypelagic layers of the mediterranean sea. Deep Sea Res Part II Top Stud Oceanogr. 2010;57(16):1446–1459. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Speicher EA, et al. Particulate organic carbon export fluxes and size-fractionated poc/234th ratios in the ligurian, tyrrhenian and aegean seas. Deep Sea Res Part I Oceanogr Res Pap. 2006;53(11):1810–1830. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.