Abstract

Evidence from experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) suggests that CNS-infiltrating dendritic cells (DCs) are crucial for restimulation of coinfiltrating T cells. Here we systematically quantified and visualized the distribution and interaction of CNS DCs and T cells during EAE. We report marked periventricular accumulation of DCs and myelin-specific T cells during EAE disease onset prior to accumulation in the spinal cord, indicating that the choroid plexus-CSF axis is a CNS entry portal. Moreover, despite emphasis on spinal cord inflammation in EAE and in correspondence with MS pathology, inflammatory lesions containing interacting DCs and T cells are present in specific brain regions.

Keywords: Dendritic cell, Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis, Multiple sclerosis, Periventricular, Choroid plexus, Rostral migratory stream

1. INTRODUCTION

Dendritic cells (DCs) are migratory antigen- (Ag-)presenting cells (APCs) that are capable of presenting major histocompatibility complex (MHC)-restricted Ag to CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells (cross presentation) and thus play central roles in priming adaptive immune responses. DCs are found in most organ tissues where, under steady-state conditions, they continually collect tissue Ag, migrate through lymphatic ducts to regional lymph nodes, and interact with naïve T cells in order to maintain peripheral tolerance. In contrast to most tissues, brain and spinal cord are considered “immune privileged,” although this term has come under scrutiny in recent years. Nevertheless, several features of the central nervous system (CNS) have been shown to regulate immune responses generated in these tissues. For example, brain and spinal cord lack conventional lymphatics for Ag drainage and exist behind the blood brain barrier which limits immune cell ingress. Additionally, very few MHCII+ DCs can be identified within the healthy CNS parenchyma—though this may partly owe to the lack of widely recognized distinguishing surface markers for DCs (reviewed in (Clarkson et al., 2012, Zozulya et al., 2010)).

Recently, Dr. Michel Nussenzweig’s group developed several fluorescent transgene-expressing reporter mouse lines for more readily identifying and tracking DCs in vivo. Using transgenic mice expressing enhanced yellow fluorescent protein (eYFP) downstream of the DC-associated CD11c promoter (CD11c-eYFP), Bulloch et al. described a discrete network of DCs within the healthy adult, developing, and aged mouse brain as well as during disease states including seizures, stroke, viral encephalitis, and in response to intracerebral (i.c.) cytokine injection (Bulloch et al., 2008, D'Agostino et al., 2012, Felger et al., 2010, Gottfried-Blackmore et al., 2009, Kaunzner et al., 2012). DCs are also thought to accumulate in the CNS during experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE, a mouse model of multiple sclerosis), and we have shown that increasing the number of CNS DCs by i.c. injection prior to EAE induction accelerates disease onset (Zozulya et al., 2009). This suggests that CNS DCs may promote neuroinflammation and that DC number in the CNS may be a rate limiting factor in EAE disease progression.

After crossing the CNS vasculature, encephalitogenic CD4+ T cells must reencounter their cognate Ag in the context of MHCII molecules in order to carry out effector functions, such as cytokine secretion. Since CNS myelinating oligodendrocytes do not constitutively present self-Ag on surface MHCII nor do they express costimulatory molecules, other tissue APCs are thought to be required to restimulate CNS-infiltrating T cells. Reciprocal bone marrow (BM) chimera experiments with MHCII deficient (−/−) mice have revealed that MHCII expression by BM derived cells and not radio-resistant cells (such as microglia) are required for disease induction. This signifies that co-infiltrating APCs contribute to CNS T cell restimulation. Furthermore, restricting MHCII expression (and thus Ag presentation to CD4+ T cells) to cells expressing the DC-associated marker CD11c was shown to be sufficient for EAE disease induction and progression (Greter et al., 2005). These studies suggest that circulating BM-derived DCs are crucial APCs that accumulate in the CNS during EAE and are indispensable for disease onset. However, DC-T cell accumulation and interaction within the CNS are still poorly characterized. Thus, we sought to track and visualize the distribution and interaction of co-infiltrating CNS DCs and T cells during EAE using CD11c-eYFP reporter mice and purified T cells from 2D2.Dsred T cell receptor transgenic mice with MOG35-55-H2b-restricted CD4+ T cells.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Mice

C57BL/6 (H2b) wild type (WT, stock #000664), and B6.Cg-Tg(CAG-Dsred*MST)1Nagy/J (Dsred, stock #006051) transgenic mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). B6.Cg-Tg(Itgax-Venus)1Mnz/J (CD11c-eYFP) transgenic mice on the C57BL/6 background were a generous gift from Dr. Michel C. Nussenzweig (Rockefeller University, NY). C57BL/6-Tg (Tcra2D2, Tcrb2D2)1Kuch/J (2D2) T cell receptor-transgenic mice with MOG35-55-H2b-restricted CD4+ T cells were a gift from Dr. Vijay Kuchroo (BWH, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA). 2D2 mice were crossed with congenic homozygous Dsred mice to generate 2D2.Dsred mice. All F1 offspring used in experiments were screened for TCR-(Vα3Vβ11) and Dsred-transgene expression by flow cytometry on immune cells isolated from blood. Standard PCR screening was used for CD11c-eYFP mice (tgc tgg ttg ttg tgc tgt ctc atc, ggg ggt gtt ctg ctg gta gtg gtc). All animal procedures used in this study were conducted in strict compliance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and approved by the University Of Wisconsin Center for Health Sciences Research Animal Care Committee.

2.2 Induction of EAE

EAE was induced in mice by MOG immunization as previously described (Lee et al., 2009). Briefly, recombinant mouse MOG35–55 (MEVGWYRSPFSRVVHLYRNGK, 2 mg / ml, 100 μg per mouse) was mixed with an equal volume of incomplete Freund adjuvant (IFA), completed by supplementing with M. tuberculosis H37Ra (5 mg/ml, Difco, Detroit, MI). MOG-CFA mixture was emulsified by sonication using an ultrasonic homogenizer (Model 300VT equipped with a titanium cup tip, Biologics Inc. Monassas, VA) and injected subcutaneously between the shoulder blades of each mouse. Pertussis toxin (200 ng/mouse, i.p.) was injected on the day of immunization and 2 days after. Mice were monitored daily for the development of clinical signs beginning at day 7 post immunization. Clinical scores were recorded as follows: 0, no clinical disease; 1, flaccid tail; 2, gait disturbance or hind limb weakness; 3, hind limb paralysis and no weight bearing on hind limbs; 4, hind limb paralysis with forelimb paresis and reduced ability to move around the cage; and 5, moribund or dead. The mean daily clinical score and standard error of the mean were calculated for each group. The significance of differences was calculated by Student’s t and Wilcox tests as described elsewhere (Fleming et al., 2005).

2.3 Fluorescent immunohistochemistry

For preparation of fixed frozen tissues, mice were perfused with PBS followed by 3-4% formalin in PBS. Tissues were removed and post-fixed in 3% formalin/25% sucrose in PBS for > 4 hours. Tissues were embedded in optimal cutting temperature (O.C.T) compound (Tissue-Tek Sakura, Torrance, CA), frozen on dry ice, and stored at −80°C until used. Using a cryostat, sections (5-30 μm) were cut from O.C.T-embedded CNS and PLO tissue samples and affixed to TES-treated slides. Before staining sections were again fixed for 20 min in ice-cold acetone and rehydrated in PBS for 30 min. Sections were mounted using ProLong Gold anti-fade reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) with 4’, 6-diamidion-2phenylindole (DAPI). Fluorescent images were acquired at 40-400x with Picture Frame software (Optronics Inc.) using an Olympus BX41 microscope (Leeds Precision Instruments) equipped with a camera (Optronics Inc., Goleta, CA). For serial sagittal brain section arrays, images were acquired using Vectra automated multispectral imaging system in collaboration with the Translational Research in Pathology (TRIP) core facility. Digital images were processed and analyzed using Photoshop CS4 software (Adobe Systems). Color balance, brightness, and contrast settings were manipulated to generate final images. All changes were applied equally to entire image.

2.4 Mononuclear cell isolation

For isolation of immune cells from CNS tissues, whole tissues were extracted from saline-perfused mice. Brain hemispheres were separated and cerebellum, brain stem (pons, medulla, and rostral spinal cord), and olfactory bulb were dissected with micro-dissecting scissors. The caudal surface of the remaining brain hemispheres were lightly chilled on pre-chilled petri-dishes (1-2 min) and then inverted so that the midbrain and subsequently the hippocampus could be separated by making caudo-rostral incisions. After gross dissection of CNS tissues, immune cells were isolated as previously described (Karman et al., 2004, Lee, Ling, 2009, Zozulya, Ortler, 2009). Briefly, tissues were weighed, finely minced, homogenized by trituration with 18 gauge needle and incubated with collagenase Type IV (1mg/mL) and DNase (28 U/mL) at 37°C for 45 min. under continuous inversion. Samples were further triturated by passage through 20-23 gauge needles and then filtered through a 70 μm cell strainers. Immune cells were separated from tissues by gradient centrifugation. After washing, CNS homogenates were resuspended in 70% Percoll (Pharmacia, Piscataway, NY) and carefully overlaid with 30% Percoll. The gradients were centrifuged at 2,500 rpm (625xg) for 30 min at 4°C with brake left off. Immune cells were collected from the interface and washed with saline for further analysis.

2.5 Flow cytometry

Single cell suspensions (<106 cells per sample) were washed and resuspended in FACS buffer (1% BSA PBS) with 40 μg/mL unlabeled 2.4G2 monoclonal antibody (mAb) to block non-specific binding to Fc receptors and incubated for 30 min on ice with saturating concentrations of fluorochrome-labeled mAbs. Afterward, cells were washed 3 times with FACS buffer. Fluorochrome-labeled mAbs against CD45 (30-F11), CD11b (M1/70), CD4 (RM4-5), Vβ11 (RR3-15), and appropriate isotype controls were purchased from BD Biosciences. Cell staining was acquired on a FACSCalibur or LSRII (BD Biosciences) and analyzed with FlowJo (Tree Star) software version 10.0.6

2.6 T cell purification and adoptive transfer

For adoptive transfer of 2D2 T cells, 2D2 mice were immunized with 100 mg MOG35-55 emulsified in CFA and lymphocytes were isolated from PLO tissues 7 days later. To enrich for CD4+ T cells prior to fluorescent activated cell sorting (FACS), cells were stained with biotinylated mAbs against CD11b (M1/70) and B220 (RA3-6B2). Cells were then washed, incubated with Strepavidin Microbeads and separated on a MidiMACS Separator using LD columns according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Miltenyi Biotec, San Diego, CA). After negative selection, a portion of cells were stained with fluorochrome labeled mAbs against CD4 (RM4.5), Vβ11 (RR3-15). T cells were washed with PBS and transferred (i.v.) into recipients by retro-orbital injection (200 μl, 1-5 ×106 cells / mouse)

2.7 Statistical analyses

Results are given as means plus or minus standard error of the mean. Multiple comparisons were made using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Where appropriate, two-sided Student’s t-test analysis was used to compare measures made between two groups. P values < 0.05 were considered significant.

3. RESULTS

3.1 Bone marrow CD11c-eYFP+ cells accumulate within CNS during EAE

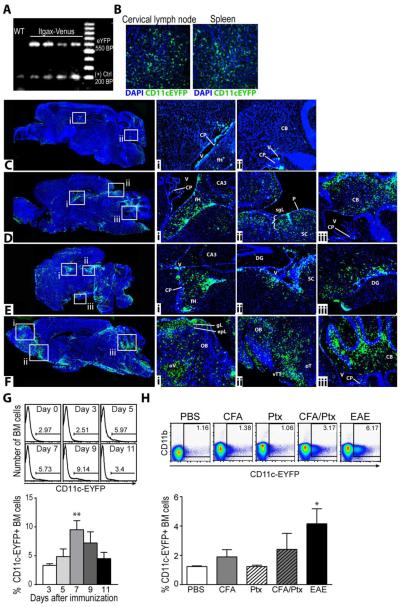

CD11c-eYFP mice (generous gift from Dr. Michel Nussenzweig) were screened for presence of eYFP transgene by standard PCR (Fig. 1A) and the visualization of eYFP-expressing DC networks in peripheral lymphoid organs was confirmed by fluorescent microscopy (Fig. 1B). In contrast to these tissues, very few CD11c-eYFP+ cells could be seen within the healthy adult CNS, as previously described ((Bulloch, Miller, 2008, Prodinger et al., 2011), Fig. 1C). These cells were restricted mostly to the meningeal areas and the choroid plexus of the lateral, third, and fourth ventricles (Fig. 1C). Upon EAE induction, we observed a pronounced increase in the distribution of CD11c-eYFP+ cells with marked accumulation of these cells in tissue bordering the ventricular system, including the fimbria of the hippocampus (DPI 12-16, Fig. 1D-E) and the white matter tracks of the cerebellum (DPI 12-20, Fig 1. D-F). We also observed an increase in the number of CD11c-eYFP+ cells in tissues bordering the meningeal compartment, including the superficial gray layer of the superior colliculus and around the olfactory bulb, especially at later time points (Fig. 1Fi-ii). CD11c-eYFP+ cells were especially concentrated within the ventral taenia tecta, the anterior olfactory cortex, as well as the dorsal granular layer of the olfactory bulb and around the olfactory ventricle. Subsequent studies with CD11c-eYFP BM chimera mice further verified that CD11c-eYFP+ cells accumulating in the CNS during EAE originated from BM (data not shown).

Figure 1. Bone marrow CD11c-eYFP+ cells accumulate within CNS during EAE.

A) Standard PCR screening of Itgax-Venus (CD11c-eYFP) mice. UV transilluminated image of eYFP PCR product (visualized with ethidium bromide) separated by size using gel electrophoresis showing eYFP amplicons (550 bp) in samples from Itgax-Venus (lanes 2-5) but not congenic wild-type mice (lane 1) relative to 100 bp DNA ladder. Endogenous reference gene is present for all samples (200 bp). B) Representative 100x images of DAPI stained fixed frozen tissue sections of cervical lymph node and spleen from CD11c-eYFP mice, showing CD11c-eyfp+ transgene expression (green) and DAPI stained cell nuclei (blue). C-F) Representative DAPI stained sagittal brain sections (merged from multiple 40X images) showing CD11c-eYFP transgene expression (green) in CD11c-eYFP mice in healthy mice (C) and 12 (D), 16 (E), or 20 (F) days after EAE induction. Cell nuclei are shown in blue. High magnification insets (100x) show regions of CD11c-eYFP+ cell accumulation (boxes on left). choroid plexus (CP), ventricle (V), fimbria of Hippocampus (fH), cerebellum (CB), CA3 are of hippocampus (CA3), dentate gyrus (DG), piamater (P), superior colliculus (SC), superficial gray layer (sgL), olfactory bulb (OB), olfactory ventricle (oV), olfactory tubercle (oT), ventral taenia tecta (vTT), glomerular layer (GL) and external plexiform layer (epL). Images are representative of 2 independent experiments with n = 3-4 mice. G) Histograms show frequency of CD11c-eYFP+ cells among total CD45+ bone marrow cells 0-11 days after MOG immunization. Mean values +/− s.e.m. plotted below. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments with n = 3-5 mice. H) Dot plots show frequency of CD11c-eYFP+ bone marrow cells 5 days after mice were treated as indicated. Mean values +/− s.e.m plotted below. Data are representative of 2 independent experiments with n = 3 mice. *p <0.05, Student’s t test.

Next, we analyzed BM cells from CD11c-eYFP mice at early time points after EAE induction. We observed a “burst” of CD11c-eYFPdim cells in BM that persisted from 5-9 days after immunization—peaking at day 7 (Fig. 1H). Further investigation revealed that immunization with complete Freund adjuvant (CFA) or pertussis toxin alone or together was insufficient to induce an increase in the frequency of CD11c-eYFPdim cells in BM, which could only be achieved by full EAE induction: immunization with myelin Ag (MOG) in CFA with pertussis toxin injection (Fig. 1G).

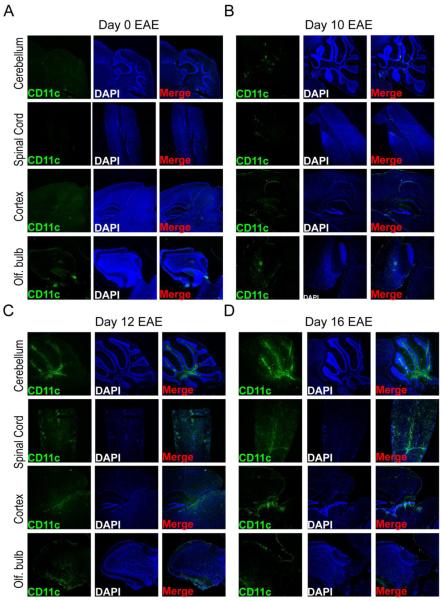

3.2 CD11c-eYFP+ cell distribution in cerebellum, spinal cord, olfactory bulb and cerebral cortex during early EAE

Next, we more closely examined CD11c-eYFP+ cell accumulation within the cerebellum, spinal cord, olfactory bulb and cortex surrounding the superior colliculus and hippocampus during early EAE by fluorescent microscopy. Compared to healthy mice (Fig. 2A), we observed very limited CD11c-eYFP+ cell accumulation in these areas at day 10 EAE (Fig. 2B), at which time CD11c-eYFP+ cells remained restricted to the lateral, third and fourth ventricles with modest accumulation in the olfactory ventricle. In contrast, by day 12 of EAE we saw marked CD11c-eYFP+ cell accumulation in the white matter tracks of the cerebellum, in the superficial layers of the superior colliculus, in the ventral areas of the olfactory bulb, and along the central canal of the cervical spinal cord (Fig. 2C). CD11c-eYFP+ cells continued to accumulate in these areas at day 16 EAE. In the spinal cord tissues in particular, we observed much more pronounced accumulation of CD11c-eYFP+ cells, which were more widely distributed at day 16 than at day 12 EAE, especially in the caudal spinal cord (Fig. 2D).

Figure 2. CD11c-eYFP+ cell distribution in cerebellum, spinal cord, olfactory bulb and cerebral cortex during early EAE.

Representative 40x images of DAPI-stained fixed frozen sections of CNS tissues from MOG-immunized CD11c-eYFP mice showing cerebellum, spinal cord, cerebral cortex surrounding the hippocampus and olfactory bulb at day 0 (A), 10 (B), 12 (C), and 16 (D) of EAE. Panels show CD11c-eYFP transgene expression in green (left), DAPI-stained cell nuclei in blue (middle), and merged image (right). Images are representative of 4 independent experiments with n = 3-5 mice.

3.3 CD11c-eYFP+ cell and MOG-specific T cell accumulation in CNS tissues during EAE

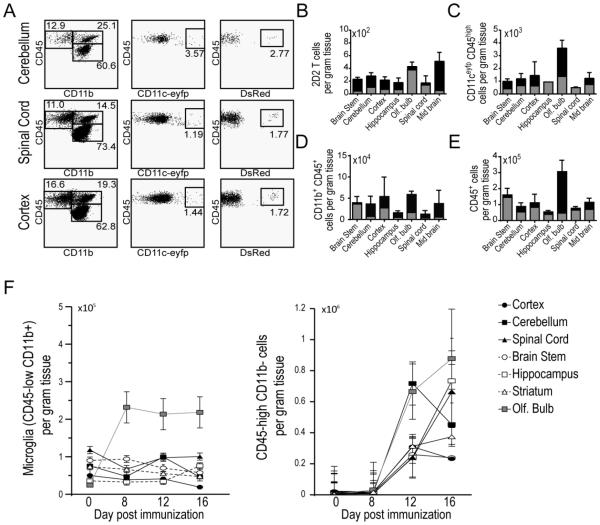

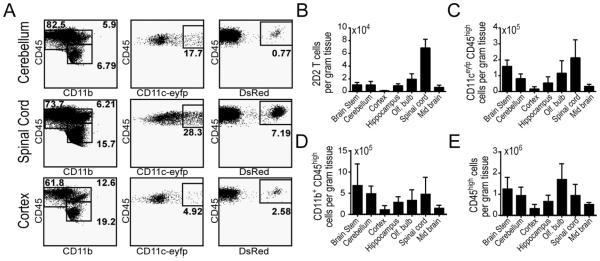

In order to compare the regional accumulation of encephalitogenic T cells and CD11c-eYFP+ cells, we purified MOG35-55-H2b-restricted CD4+ T cells from T cell receptor (TCR) transgenic 2D2 mice (generous gift from Dr. Vijay Kuchroo), which had been crossed with congenic homozygous Dsred mice (Fig. S1A). We then transferred these T cells into CD11c-eYFP mice and induced EAE by MOG immunization two days later. Using flow cytometry we tracked the accumulation of CD11c-eYFP+ cells, 2D2 T cells, CD11b+ myeloid cells and total CD45+ leukocytes at day 8 (Fig. 3), day 12 (Fig. 4), and day 16 (Fig. 5).

Figure 3. CD11c-eYFP+ cell and MOG-specific T cell accumulation in CNS tissues Day 8 EAE.

A) Representative dot plots of CD45+ immune cells isolated from cerebellum, spinal cord and cerebral cortex of CD11c-eYFP mice 8 days after EAE induction. Left column, plots show frequency of CD45low microglia and CD45high CD11b+ myeloid cells. Middle column, plots show frequency of CD11c-eYFP+ cells among all CD45high leukocytes. Right column, plots show frequency of MOG-specific 2D2.Dsred donor T cells among CD45highCD11b−leukocytes. B-E) Bar graphs show absolute number of MOG-specific 2D2.Dsred+ donor T cells (B), CD45high CD11c-eYFP+ dendritic cells (C), CD45highCD11b+ myeloid cells (D) and total CD45high leukocytes (E) in brain stem, cerebellum, cerebral cortex, hippocampus, olfactory bulb, spinal cord, and mid brain at day 0 (grey) and day 8 (black) EAE. F) Line graphs show absolute number of CD45lowCD11b+ microglia (left) and non-myeloid immune cells (CD45+CD11b-) in CNS tissues in healthy mice and day 8-16 post MOG immunization. Mean values +/− s.e.m are plotted. Data are representative of 2 independent experiments with n = 3-6 mice.

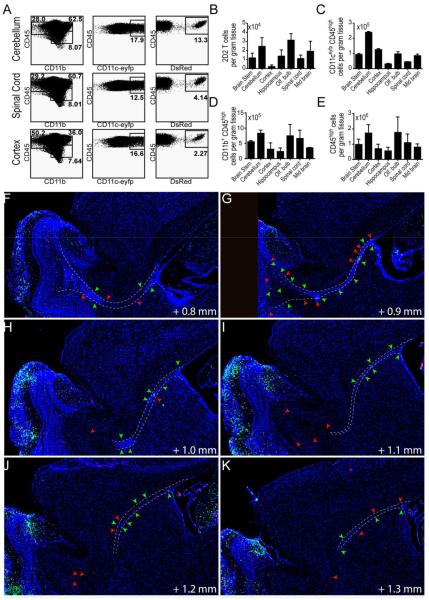

Figure 4. CD11c-eYFP+ cell and MOG-specific T cell accumulation in CNS tissues Day 12 EAE.

A) Representative dot plots of CD45+ immune cells isolated from cerebellum, spinal cord and cerebral cortex of CD11c-eYFP mice 12 days after EAE induction. Left column, plots show frequency of CD45low microglia and CD45high CD11b+ myeloid cells. Middle column, plots show frequency of CD11c-eYFP+ cells among all CD45high leukocytes. Right column, plots show frequency of MOG-specific 2D2.Dsred donor T cells among CD45highCD11b− leukocytes. B-E) Bar graphs show absolute number of MOG-specific 2D2.Dsred+ donor T cells (B), CD45high CD11c-eYFP+ dendritic cells (C), CD45highCD11b+ myeloid cells (D) and total CD45high leukocytes (E) in brain stem, cerebellum, cerebral cortex, hippocampus, olfactory bulb, spinal cord, and mid brain. Mean values +/− s.e.m plotted. Data are representative of 2 independent experiments with n = 3-6 mice. F-K) 100 micron-spaced sagittal brain sections (40x) showing distribution of CD11c+ cells (green) and MOG-specific T cells (red) in lateral ventricle, rostral migratory stream (RMS, dotted line), and olfactory bulb. Arrows indicate DCs and T cells in the RMS.

Figure 5. CD11c-eYFP+ cell and MOG-specific T cell accumulation in CNS tissues Day 16 EAE.

A) Representative dot plots of CD45+ immune cells isolated from cerebellum, spinal cord and cerebral cortex of CD11c-eYFP mice 16 days after EAE induction. Left column, plots show frequency of CD45low microglia and CD45high CD11b+ myeloid cells. Middle column, plots show frequency of CD11c-eYFP+ cells among all CD45high leukocytes. Right column, plots show frequency of MOG-specific 2D2.Dsred donor T cells among CD45highCD11b− leukocytes. B-E) Bar graphs show absolute number of MOG-specific 2D2.Dsred+ donor T cells (B), CD45high CD11c-eYFP+ dendritic cells (C), CD45highCD11b+ myeloid cells (D) and total CD45high leukocytes (E) in brain stem, cerebellum, cerebral cortex, hippocampus, olfactory bulb, spinal cord, and mid brain. Mean values +/− s.e.m plotted. Data are representative of 2 independent experiments with n = 3-6 mice.

By gross dissecting mouse brains prior to immune cell isolation and immuno-labeling, we were able to separately analyze the immune cell accumulation within the brain stem (pons, medulla, and rostral spinal cord), cerebellum, cerebral cortex, hippocampus, olfactory bulb, spinal cord, and mid brain. At day 8 after EAE induction, we observed very little increase in immune cell levels in these CNS tissues compared to healthy mice (shown in grey). MOG-specific 2D2 T cells were all but absent from the CNS with fewer than 500 cells per gram of tissue in all regions studied (Fig. 3B). At this time point CD11c-eYFP+ cells were present at very low levels with the highest concentration of cells found in the olfactory bulb (approximately 3500 cells per gram tissue, Fig. 3C), as was the case for myeloid cells (Fig. 3D) and total leukocytes (Fig. 3E). This increase in total CD45+ and CD11b+ myeloid in the olfactory bulb, was likely due to an early increase in the number of microglia in the olfactory bulb at this time point, which persisted at later time points (Fig. 3F).

As before, we saw a strong increase in immune cells in the CNS by EAE day 12. Compared to day 8, 2D2 T cells accumulated to higher levels in all CNS regions, especially in the olfactory bulb, cerebellum and midbrain (Fig. 4B). CD11c-eYFP+ cells also accumulated to around 100x higher levels at day 12 than at day 8. Remarkably in the cerebellum we observed a > 200 fold increase in the abundance of CD11c-eYFP+ cells during this time (Fig. 4C). This far outpaced the relative increase in myeloid cells (Fig. 4D), non-myeloid (CD11b-CD45+) cells (Fig. 3F), and total CD45+ leukocytes (Fig. 4E), all of which increased in most CNS tissues by a factor of 10.

Between day 12 and day 16 we observed a shift from inflammatory cells accumulating mostly in brain tissues toward predominant accumulation in spinal cord tissues. For MOG-specific 2D2 T cells this was most pronounced. We observed a 6 fold increase in 2D2 T cell abundance in spinal cord from day 12 to day 16, while 2D2 T cell levels in most brain tissues remained constant or decreased (Fig. 5B). This corresponded with an increase in the number of total non-myeloid leukocytes that were recovered from the spinal cord olfactory bulb and hippocampus (Fig. 3F). The number of CD11c-eYFP+ cells similarly increased primarily in spinal cord tissue between day 12 and day 16. Whereas CD11c-eYFP+ cell levels in most brain tissues remained relatively constant (brain stem, hippocampus, olfactory bulb) or diminished slightly (cortex, cerebellum, midbrain), CD11c-eYFP+ cell frequency increased nearly 4 fold in spinal cord (Fig. 5C). In contrast, we did not observe a large increase in the frequency of myeloid or total leukocytes in spinal cord, where—like brain tissues—cell levels remained relatively constant (Fig. 5D-E).

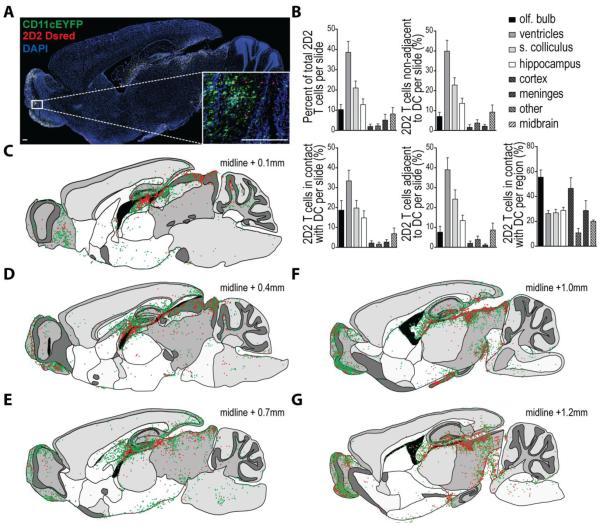

3.4 Mapping DC-T cell interactions in the brain during onset of neuroinflammation

As we had previously seen that the earliest detectable increase in T cell and DC accumulation in the CNS during EAE occurred around day 12 post immunization, we chose this time point to visualize the relative in situ distribution of CNS-infiltrating DCs and MOG-specific T cells. We imaged DAPI-stained sagittal brain sections from CD11c-eYFP mice with EAE (DPI 12) adoptively transferred with purified MOG-specific CD4+ T cells from 2D2.Dsred mice (Fig. 6A). Flow cytometry on cells isolated from various regions in the contralateral hemispheres revealed that > 80% of CD11c-eYFP+ cells in the CNS at this time point were CD45+, suggesting that these cells were chiefly non-microglial cells of hematopoietic origin (Fig. S1B). We found that at this time point CNS-infiltrating 2D2 T cells accumulated primarily in tissues adjacent to the ventricular system—especially near the hippocampus (Fig. 6C-E)—and also in the optic nerve and primary visual areas including the superior colliculus (Fig. 6F-G). Similarly, CD11c-eYFP+ DCs accumulated predominantly in tissues adjacent to the ventricular system; however, they displayed a distinct tendency to accumulate in the fimbria of the hippocampus and in the corpus collosum (Fig. 6D) as well as the pallidum adjacent to the lateral ventricles (Fig. 6F). CD11c-eYFP+ cells could also be detected within the olfactory projection of the lateral ventricles and along the rostral migratory stream (Fig. 6F-G, Fig. 4F-K). This was accompanied by strong accumulation of CD11c-eYFP+ cells in the olfactory bulb (Fig. 6E-G) and ventral taenia tecta (Fig. 6C-D).

Figure 6. Mapping DC-T cell interactions in the brain during onset of neuroinflammation.

MOG-specific 2D2.Dsred CD4+Vβ11+ T cells were purified by negative selection with magnetic beads and adoptively transferred into CD11c-eYFP mice. Two days later mice were immunized with MOG to induce EAE and brains were harvest for tissue sectioning upon clinical onset (day 12 post immunization). 15-30 micron thick sagittal sections (space 100 microns apart) were collected from throughout each brain hemisphere. A) Representative mosaic image of DAPI stained sagittal brain sections. Mosaic images were created by Vectra Automated slide scanning system by merging multiple 40x images. High magnification (100x) inset shows interaction between MOG-specific 2D2.Dsred donor T cells (red) and CD11c-eYFP transgene expressing dendritic cells (green) in olfactory bulb. DAPI-stained cell nuclei shown in blue. Scale bar 200 μm. B) 2D2.Dsred+ cells from high powered fields (n = 10 per slide) were enumerated for the various CNS anatomical regions listed and categorized based on proximity to CD11c-eYFP+ cells as follows: > 3 cell widths, isolated; < 3 cell widths but no fluorescent overlap, adjacent; green / red fluorescent overlap, contact. Bar graphs indicate percent of total MOG-specific 2D2.Dsred+ T cells counted per slide for each anatomical region as well as the absolute number of 2D2.Dsred+ T cells in contact with, adjacent to, or isolated from CD11c-eYFP+ dendritic cells. Mean values +/− s.e.m. plotted for 6191 T cells counted across n = 20 brain sections. C-G) Traced outlines of DAPI-stained sagittal brain sections as in (A—matches to F), showing distribution of CD11c-eYFP+ cells (green dots) and MOG-specific 2D2.Dsred+ donor T cells (red dots) throughout the brain at day 12 EAE. Each dot represents approximately 1 cell. Outlines taken from sections with increasing distance from the sagittal midline (C, 0.1 mm; D, 1.4 mm; E, 0.7 mm; F, 1.0 mm; G, 1.2 mm). Images are representative of 3 independent experiments with n = 3-6 mice per group.

Using high-powered fields from each tissue section we further enumerated and categorized brain-infiltrating T cells based on their proximity to CD11c-eYFP transgene expressing cells. This allowed us to more accurately quantify the accumulation of T cells in situ in various CNS regions as well as determine the level of T cell-DC interaction within these different CNS regions. Based on our classification system, we found that the around 40% of MOG-specific T cells present in the CNS at day 12 EAE were restricted to the ventricular system. Many of these cells were present in the choroid plexus or were closely associated with the ventricular wall, with limited infiltration into the CNS parenchyma (Fig. 6B). 2D2 T cells also accumulated modestly in the superior colliculus (20%), the olfactory bulb (10%), and the hippocampus (10%). Among these cells, we found that in most brain tissues approximately 50% of 2D2 T cells were non-adjacent (>3 cell widths) from CD11c-eYFP+ DCs, with 25% adjacent (<3 cell widths) to DCs and another 25% in presumable contact with DCs. As an exception to this rule, we found that in the olfactory bulb a majority (55%) of 2D2 T cells were in contact with DCs, with 10% adjacent and 30% non-adjacent to CD11c-eYFP+ DCs —owing likely to the dense network of CD11c-eYFP+ cells in this tissue (Fig. 6B, Fig. 6A inset). This increase in the frequency of T cells in contact with DCs was also true of the cerebral cortex though, unlike the olfactory bulb, there were relatively few 2D2 T cells in this tissue. Thus, of all brain infiltrating 2D2 T cells found in contact with CD11c-eYFP+ cells, 35% were found in association with the ventricular system, 20% each were located in the olfactory bulb and superior colliculus, 15% were in the hippocampus, 5% were in the midbrain, and 5% were distributed among cortex meninges and other CNS tissues (Fig. 6B).

4. DISCUSSION

Prior work has described CNS DC distribution in the quiescent state (Bulloch, Miller, 2008, Prodinger, Bunse, 2011). Bulloch et al. were the first to describe the distribution of CD11c-eYFP+ cells throughout the CNS of healthy adult mice. Here we confirm their initial report, showing that CD11c-eYFP+ cells were mostly restricted to the choroid plexus, meninges, and surfaces of the lateral, third, and forth ventricles, with low levels of CD11c-eYFP+ cells diffusely distributed throughout the CNS. More recently Prodinger and colleagues used CD11c-DTR mice expressing bicistronic GFP downstream of the CD11c promoter to identify CD11c+ cells in the healthy CNS. They similarly observed that CD11c+ cells were present in the tela of the choroid plexus and beneath the ependymal lining of the ventricles, especially in the white matter of tracts of the corpus collosum and fornix. Similarly, they also identified CD11c+ cells diffusely distributed in white matter tracts in the optic nerve, olfactory bulb, brain stem, cerebellum and spinal cord. Most of these cells expressed low levels of MHC II and co-expressed the microglial markers Iba-1 and CD11b. This is in agreement with our own findings that the majority of CD11c-eYFP+ cells within the healthy CNS express intermediate levels of CD45, which is associated with microglia (unpublished data). More interestingly, they also described a population of cells expressing the DC marker CD209 within the CNS parenchyma in close vicinity to blood vessels. Closer analysis revealed that these cells interdigitated with astroglial endfeet and integrated into the glia limitans, where they were presumably poised for interacting with cells in the perivascular space (Prodinger, Bunse, 2011). Indeed, these cells may play an important role as tissue APCs during neuroinflammation; however, their relatively limited abundance together with data showing that MHCII expression on infiltrating cells is required for EAE (Greter, Heppner, 2005) suggests that other APCs strongly contribute to T cell restimulation.

Here we describe the regional accumulation and in situ distribution of CD11c+ cells, the majority of which are CNS-infiltrating DCs, and co-infiltrating MOG-specific T cells, over the course of EAE disease onset and progression using CD11c-eYFP reporter mice and transferred 2D2.Dsred MOG-specific CD4+ T cells. This is the first report to our knowledge systematically describing the localization of CNS-infiltrating DCs and co-infiltrating myelin-specific T cells. A better understanding of DC-T cell colocalization in the CNS during neuroinflammation is important since DCs are capable of promoting specific T cell restimulation in situ through APC function. Additionally, comparison of DC and T cell immigration allows us to partially distinguish between regional expression of non-cell specific vessel / endothelial cell permeability factors and DC- or T cell-specific recruitment factors.

These findings should be integrated with similar reports by Brown et al. (2007) and Serafini et al. (2000), which respectively characterized CNS microglial activation and DC T cell infiltration throughout EAE disease course using immunohistochemical approaches (Brown and Sawchenko, 2007, Serafini et al., 2000). During preclinical EAE, we found evidence for early microglial and DC accumulation in the olfactory bulb. Similarly, Brown and colleagues observed microglial activation in olfactory bulb at early preclinical time points. In their studies, they also observed microglial activation along ependymal and pial surfaces that border the ventricular system and subarachnoid space, respectively. Serafini et al. also detected CD11c+ DEC-205+ DCs present in subpial tissues in spinal cord during preclinical EAE. However, in both their studies and ours DCs and T cells did not begin accumulating in these tissues until after disease onset (day 12 in our hands). This suggests that microglial activation, especially in olfactory bulb and periventricular tissues may precede immune cell recruitment.

In cerebellum and hippocampus, DCs were found at highest density along the ependymal walls of the lateral and fourth ventricles and occasionally deeper within parenchyma adjacent to blood vessels, indicative of recent immigration into the tissue. In contrast, DCs found in the olfactory bulb did not associate with blood vessels and were found in the granular layer and the ventral surface of the olfactory bulb adjacent to the cribriform plate, suggesting that these cells did not recently immigrate from blood and may have migrated from other brain regions. The RMS, which runs along white matter tracks from the subventricular zone of the lateral ventricles to the olfactory bulb, has been well characterized as a migratory pathway for neural progenitor cells (Tang et al., 2014, Tepavcevic et al., 2011, Ueno et al., 2000). Intriguingly, this pathway has recently been suggested to have a role in DC migration (Mohammad et al., 2014). In a series of elegant experiments, Dr. David Brown’s group has demonstrated that in the steady-state CNS DCs migrate through the RMS toward the olfactory bulb en route to the cLNs where they promote Treg activity and tolerance. Building on these data, we show here that DCs and T cells are present at high levels in the RMS pathway during EAE, suggesting elevated migration along this pathway during neuroinflammation.

Similar to observations in MS patients, MOG-specific T cells accumulated to high levels in sensory areas including olfactory bulb and optic nerve. Interestingly, as previously observed, T cells also heavily infiltrated optic tectum (superficial superior colliculus), where many optic nerve axons are known to project. This supports the scenario put forth by Brown et al. where T cells first infiltrate sensory nerves near the meningeal barrier causing trans-synatpic and Wallerian degeneration of cortical neurons leading to microglial activation and secondary inflammation in associated cortex. This is supported by studies in MS patients where optic neuritis and retinal injury were associated with increased levels of MRI abnormality in the optic radiation and visual cortex (Pfueller et al., 2011, Reich et al., 2009, Rocca et al., 2013).

More generally, prominent initial immune cell infiltration of brain tissues associated with the ventricular system, suggests a role for the choroid plexus and CSF as a gateway for immune cells into the CNS. This is consistent with previous reports of immune cell infiltration of the CNS via the choroid plexus-CSF axis (Brown and Sawchenko, 2007, Hatterer et al., 2008, Meeker et al., 2012, Schmitt et al., 2012). For example, Reboldi and colleagues demonstrated that initial T cell infiltration of the CNS occurred at the blood-CSF-barrier of the choroid plexus and was followed by a second wave of T cell infiltration across the BBB of the parenchyma. (Reboldi et al., 2009). Indeed, histological studies of brain tissues during EAE in both rats and mice have identified a gradient of lymphocytic and monocytic infiltrates in periventricular tissues, with highest cell densities near the ventricle wall—suggesting directional migration of these cells from CSF into brain parenchyma (Brown and Sawchenko, 2007, Schmitt, Strazielle, 2012). Moreover, others have shown that during EAE in rats intra-CSF injected DCs migrate toward and accumulate within parenchymal lesions adjacent to the ventricular wall (Hatterer, Touret, 2008). Together these studies suggest that initial DC and T cell recruitment to the brain during EAE proceeds through the choroid plexus and associated CSF-filled compartments.

We also report prominent DC accumulation within the spinal cord, especially at later time points. In contrast, at day 12 of EAE DC accumulation in the spinal cord is limited to tissues immediately adjacent the central canal or pial surface. It’s likely that, similar to brain tissues, these initial infiltrators are migrating into parenchyma from CSF. Others have previously demonstrated this possibility. For example, Shechter et al. showed that following spinal cord injury M2 macrophages first cross the choroid plexus of the brain and enter CSF before they are recruited to the inflammatory site along the spinal cord central canal (Shechter et al., 2013).

DCs and T cells are likely recruited to the inflamed CNS by distinct chemotactic factors. Thus, due to their capacity for differential recruitment, we sought to identify areas of common infiltration where DCs and T cells are likely to interact. DC-T cell interaction is important because T cells require restimulation by tissue APCs in order to see their cognate antigen and carry out effector functions (e.g. cytokine production). Several reports have suggested that CNS-infiltrating DCs may be crucial APCs for in situ restimulation of T cells (Bailey et al., 2007, Bartholomaus et al., 2009, Greter, Heppner, 2005, Odoardi et al., 2007, Pesic et al., 2013, Wlodarczyk et al., 2014). For example, several studies using in vivo imaging studies have shown that T cells encounter and form stable interactions with perivascular phagocytes prior to their infiltration of the CNS parenchyma (Bartholomaus, Kawakami, 2009, Odoardi, Kawakami, 2007, Pesic, Bartholomaus, 2013). Ex vivo T cell activation assays demonstrated that CD11b+ CD11c+ myeloid DCs are the most potent CNS APCs (Bailey, Schreiner, 2007), and a recent study demonstrated that while CD11c+ microglia express MHC II during EAE they do not license T cells to become Th1 and Th17 effectors cells (Wlodarczyk, Lobner, 2014). Subsequent studies have shown that CD11c+ cell MHCII expression is both sufficient (Greter, Heppner, 2005) and required (manuscript in preparation) for T cell restimulation in situ.

While 2D2 T cells predominated the cellular infiltrate of the optic nerve and optic tectum, infiltrating DCs outnumbered transferred 2D2 T cells in the cerebral cortex and olfactory bulb. We found that 25-50% of T cells colocalized with CD11c+ DCs, with the highest frequency of T cells in contact with DCs in the olfactory bulb (55%) and cerebral cortex (45%). Interestingly, in separate experiments we found that following ex vivo restimulation with MOG peptide the frequency of IL-17 producing T cells isolated from cerebral cortex and olfactory bulb was higher than other CNS regions at day 12 EAE as assessed by intracellular cytokine staining (unpublished data). Indeed, even without stimulation (media alone) the frequency of IL-17 producing T cells in the olfactory bulb was higher than that of MOG-stimulated cells from spinal cord, brainstem, meninges, or cerebellum. Together these data suggest that relative frequency of co-infiltrating DCs is key determinant of T cell cytokine production.

5. CONCLUSION

In summary, we describe marked accumulation of DCs and MOG-specific T cells in the cerebellum and tissues surrounding the ventricular system during EAE disease onset. As disease progressed, DC and T cell accumulation diminished in brain tissues and increased markedly in spinal cord, suggesting the brain may serve as a transient portal of entry into the CNS for circulating leukocytes—especially through the vasculature of the choroid plexus and ventricular system. Together these results provide evidence that despite the emphasis on spinal cord inflammation in EAE and in correspondence with MS pathology, inflammatory lesions containing interacting DCs and T cells are present in the brain in specific peri-ventricular and sub-pial white matter tissues. Furthermore, these cells accumulate in brain tissues prior to their later pronounced accumulation in spinal cord. A more complete understanding of EAE brain pathology and the factors that contribute to the transition to spinal cord inflammation at later time points may add to our understanding of MS pathogenesis.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

BMDCs and T cells accumulate and interact in specific brain regions in early EAE.

DCs and T cells accumulate in periventricular brain tissues before spinal cord.

Immune cell migration through RMS is increased during neuroinflammation.

We identify primary and secondary CNS compartments of immune cell entry in EAE.

6. ACKNOWLDEGEMENTS

We would like to thank members of our laboratory for helpful discussions and constructive criticisms of this work and Khen Macvilay for his expertise provided for cytofluorimetry. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants NS37570-01A2 (to Z.F). The authors thank the University of Wisconsin Translational Research Initiatives in Pathology laboratory, in part supported by the UW Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine and UWCCC grant P30 CA014520, for use of its facilities and services.

ABBREVIATIONS

- DC

Dendritic cell

- EAE

Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis

- MS

Multiple sclerosis

- RMS

Rostral migratory stream

- Ag

Antigen

- BM

Bone Marrow

- MHC

Majorhistocompatibility complex

- MOG

Myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein

- i.c.

Intracerebral

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors have no financial or personal conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- Bailey SL, Schreiner B, McMahon EJ, Miller SD. CNS myeloid DCs presenting endogenous myelin peptides 'preferentially' polarize CD4+ T(H)-17 cells in relapsing EAE. Nature immunology. 2007;8:172–80. doi: 10.1038/ni1430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartholomaus I, Kawakami N, Odoardi F, Schlager C, Miljkovic D, Ellwart JW, et al. Effector T cell interactions with meningeal vascular structures in nascent autoimmune CNS lesions. Nature. 2009;462:94–8. doi: 10.1038/nature08478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown DA, Sawchenko PE. Time course and distribution of inflammatory and neurodegenerative events suggest structural bases for the pathogenesis of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. The Journal of comparative neurology. 2007;502:236–60. doi: 10.1002/cne.21307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulloch K, Miller MM, Gal-Toth J, Milner TA, Gottfried-Blackmore A, Waters EM, et al. CD11c/EYFP transgene illuminates a discrete network of dendritic cells within the embryonic, neonatal, adult, and injured mouse brain. The Journal of comparative neurology. 2008;508:687–710. doi: 10.1002/cne.21668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarkson BD, Heninger E, Harris MG, Lee J, Sandor M, Fabry Z. Innate-adaptive crosstalk: how dendritic cells shape immune responses in the CNS. Advances in experimental medicine and biology. 2012;946:309–33. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-0106-3_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Agostino PM, Kwak C, Vecchiarelli HA, Toth JG, Miller JM, Masheeb Z, et al. Viral-induced encephalitis initiates distinct and functional CD103+ CD11b+ brain dendritic cell populations within the olfactory bulb. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109:6175–80. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1203941109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felger JC, Abe T, Kaunzner UW, Gottfried-Blackmore A, Gal-Toth J, McEwen BS, et al. Brain dendritic cells in ischemic stroke: time course, activation state, and origin. Brain, behavior, and immunity. 2010;24:724–37. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming KK, Bovaird JA, Mosier MC, Emerson MR, LeVine SM, Marquis JG. Statistical analysis of data from studies on experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Journal of neuroimmunology. 2005;170:71–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2005.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottfried-Blackmore A, Kaunzner UW, Idoyaga J, Felger JC, McEwen BS, Bulloch K. Acute in vivo exposure to interferon-gamma enables resident brain dendritic cells to become effective antigen presenting cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:20918–23. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911509106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greter M, Heppner FL, Lemos MP, Odermatt BM, Goebels N, Laufer T, et al. Dendritic cells permit immune invasion of the CNS in an animal model of multiple sclerosis. Nature medicine. 2005;11:328–34. doi: 10.1038/nm1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatterer E, Touret M, Belin MF, Honnorat J, Nataf S. Cerebrospinal fluid dendritic cells infiltrate the brain parenchyma and target the cervical lymph nodes under neuroinflammatory conditions. PloS one. 2008;3:e3321. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karman J, Ling C, Sandor M, Fabry Z. Initiation of immune responses in brain is promoted by local dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2004;173:2353–61. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.4.2353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaunzner UW, Miller MM, Gottfried-Blackmore A, Gal-Toth J, Felger JC, McEwen BS, et al. Accumulation of resident and peripheral dendritic cells in the aging CNS. Neurobiology of aging. 2012;33:681–93. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2010.06.007. e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Ling C, Kosmalski MM, Hulseberg P, Schreiber HA, Sandor M, et al. Intracerebral Mycobacterium bovis bacilli Calmette-Guerin infection-induced immune responses in the CNS. Journal of neuroimmunology. 2009;213:112–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2009.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meeker RB, Williams K, Killebrew DA, Hudson LC. Cell trafficking through the choroid plexus. Cell adhesion & migration. 2012;6:390–6. doi: 10.4161/cam.21054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammad MG, Tsai VW, Ruitenberg MJ, Hassanpour M, Li H, Hart PH, et al. Immune cell trafficking from the brain maintains CNS immune tolerance. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2014;124:1228–41. doi: 10.1172/JCI71544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odoardi F, Kawakami N, Klinkert WE, Wekerle H, Flugel A. Blood-borne soluble protein antigen intensifies T cell activation in autoimmune CNS lesions and exacerbates clinical disease. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:18625–30. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705033104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pesic M, Bartholomaus I, Kyratsous NI, Heissmeyer V, Wekerle H, Kawakami N. 2-photon imaging of phagocyte-mediated T cell activation in the CNS. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2013;123:1192–201. doi: 10.1172/JCI67233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfueller CF, Brandt AU, Schubert F, Bock M, Walaszek B, Waiczies H, et al. Metabolic changes in the visual cortex are linked to retinal nerve fiber layer thinning in multiple sclerosis. PloS one. 2011;6:e18019. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prodinger C, Bunse J, Kruger M, Schiefenhovel F, Brandt C, Laman JD, et al. CD11c-expressing cells reside in the juxtavascular parenchyma and extend processes into the glia limitans of the mouse nervous system. Acta neuropathologica. 2011;121:445–58. doi: 10.1007/s00401-010-0774-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reboldi A, Coisne C, Baumjohann D, Benvenuto F, Bottinelli D, Lira S, et al. C-C chemokine receptor 6-regulated entry of TH-17 cells into the CNS through the choroid plexus is required for the initiation of EAE. Nature immunology. 2009;10:514–23. doi: 10.1038/ni.1716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reich DS, Smith SA, Gordon-Lipkin EM, Ozturk A, Caffo BS, Balcer LJ, et al. Damage to the optic radiation in multiple sclerosis is associated with retinal injury and visual disability. Archives of neurology. 2009;66:998–1006. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocca MA, Mesaros S, Preziosa P, Pagani E, Stosic-Opincal T, Dujmovic-Basuroski I, et al. Wallerian and trans-synaptic degeneration contribute to optic radiation damage in multiple sclerosis: a diffusion tensor MRI study. Mult Scler. 2013;19:1610–7. doi: 10.1177/1352458513485146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt C, Strazielle N, Ghersi-Egea JF. Brain leukocyte infiltration initiated by peripheral inflammation or experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis occurs through pathways connected to the CSF-filled compartments of the forebrain and midbrain. J Neuroinflammation. 2012;9:187. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-9-187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serafini B, Columba-Cabezas S, Di Rosa F, Aloisi F. Intracerebral recruitment and maturation of dendritic cells in the onset and progression of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. The American journal of pathology. 2000;157:1991–2002. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64838-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shechter R, Miller O, Yovel G, Rosenzweig N, London A, Ruckh J, et al. Recruitment of beneficial M2 macrophages to injured spinal cord is orchestrated by remote brain choroid plexus. Immunity. 2013;38:555–69. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang SK, Knobloch RA, Maucksch C, Connor B. Redirection of doublecortin-positive cell migration by over-expression of the chemokines MCP-1, MIP-1alpha and GRO-alpha in the adult rat brain. Neuroscience. 2014;260:240–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2013.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tepavcevic V, Lazarini F, Alfaro-Cervello C, Kerninon C, Yoshikawa K, Garcia-Verdugo JM, et al. Inflammation-induced subventricular zone dysfunction leads to olfactory deficits in a targeted mouse model of multiple sclerosis. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2011;121:4722–34. doi: 10.1172/JCI59145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueno M, Tanaka S, Miyabe K, Kanenishi K, Onodera M, Yanghong W, et al. Dendritic cell-like immunoreactivity in the glomerulus of the olfactory bulb and olfactory nerves of mice. Neuroreport. 2000;11:3573–6. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200011090-00034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wlodarczyk A, Lobner M, Cedile O, Owens T. Comparison of microglia and infiltrating CD11c(+) cells as antigen presenting cells for T cell proliferation and cytokine response. J Neuroinflammation. 2014;11:57. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-11-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zozulya AL, Clarkson BD, Ortler S, Fabry Z, Wiendl H. The role of dendritic cells in CNS autoimmunity. J Mol Med (Berl) 2010;88:535–44. doi: 10.1007/s00109-010-0607-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zozulya AL, Ortler S, Lee J, Weidenfeller C, Sandor M, Wiendl H, et al. Intracerebral dendritic cells critically modulate encephalitogenic versus regulatory immune responses in the CNS. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2009;29:140–52. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2199-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.