Abstract

Poor access to buprenorphine maintenance treatment (BMT) may contribute to illicit buprenorphine use. This study investigated illicit buprenorphine use and barriers to BMT among syringe exchange participants. Computer-based interviews conducted at a New York City harm reduction agency determined: prior buprenorphine use; barriers to BMT; and interest in BMT. Of 102 opioid users, 57 had used illicit buprenorphine and 32 had used prescribed buprenorphine. When illicit buprenorphine users were compared to non-users: barriers to BMT (“did not know where to get treatment”) were more common (64% vs. 36%, p < 0.01); mean levels of interest in BMT were greater (3.37 ± 1.29 vs. 2.80 ± 1.34, p = 0.03); and more participants reported themselves likely to initiate treatment (82% vs. 50%, p < 0.01). Illicit buprenorphine users were interested in BMT but did not know where to go for treatment. Addressing barriers to BMT could reduce illicit buprenorphine use.

Keywords: buprenorphine, syringe exchange, access to care, opioid addiction

1. Introduction

The epidemic of opioid addiction has grown rapidly with opioid overdose-related deaths more than tripling over the past decade (CDC, 2011; CDC, 2013). Expansion of treatment for opioid addiction has failed to keep pace, and only one quarter of those who need treatment receive treatment leaving a large treatment gap (SAMHSA, 2012a ; SAMHSA, 2012b). Buprenorphine maintenance treatment (BMT), an option for opioid addiction treatment that has been available in the United States since 2002, is effective and may be more acceptable to patients than methadone maintenance, but it has failed to substantially reduce the treatment gap (Awgu, Magura, & Rosenblum, 2010; Mattick, Kimber, Breen, & Davoli, 2008). To date, most studies of barriers to BMT have examined the challenges of physicians or health systems to provide treatment (Korthuis et al., 2010; Roman, Abraham, & Knudsen, 2011; Savage et al., 2012; Schuman-Olivier et al., 2013), but many of the factors that prevent more people who use drugs (PWUD) from initiating BMT are still unknown.

Among potential barriers to BMT, access to treatment has been understudied. White race, private insurance, dependence on opioid analgesics, and living in an area with a high density of physicians waivered to prescribe buprenorphine are all associated with receipt of BMT, but access may be more limited for marginalized groups, such as the uninsured or heroin users (Ducharme & Abraham, 2008; Kissin, McLeod, Sonnefeld, & Stanton, 2006; Murphy et al., 2014; Stein et al., 2012). As recently as 2011, data from New York City demonstrated high levels of interest but low levels of enrollment in BMT among participants of syringe exchange programs, a marginalized group of PWUD with particularly high treatment needs (Fox et al., 2014). PWUD may not know how to find a buprenorphine provider; costs may be prohibitive; and the most marginalized PWUDs may be completely disconnected from traditional health care systems. Understanding these patient-level barriers to BMT will aid in developing strategies to overcome them.

While access to BMT has failed to meet demand, use of diverted or illicit buprenorphine is increasing and has recently received more attention (Dasgupta et al., 2010; Johanson, Arfken, di Menza, & Schuster, 2012). Existing data suggest that many illicit buprenorphine users take diverted buprenorphine to reduce symptoms of opioid withdrawal, not for intoxication or euphoria; thus, illicit buprenorphine use may in part be due to lack of access to BMT (Bazazi et al., 2011; Genberg et al., 2013; Gwin Mitchell et al., 2009; Lofwall & Havens, 2012; Monte et al., 2009; Sohler et al., 2013). Among BMT patients, prioir illicit buprenorphine use has not been associated with negative treatment outcomes (Cunningham et al., 2013), and clinical experience suggests that PWUD attempt to cut down or stop using opioids with illicit buprenorphine for a period of time before they actually initiate BMT. Therefore, illicit buprenorphine users who could benefit from BMT may be ready for treatment but experiencing barriers to care; however, additional data is necessary to confirm these clinical observations.

In this study we investigated illicit buprenorphine use, barriers to BMT, and interest in initiating BMT among syringe exchange participants. Our two main research questions were: are illicit buprenorphine users: 1.) experiencing barriers to BMT; and 2) interested in initiating treatment with BMT? Findings can guide the development of interventions to improve access to BMT.

2. Materials and methods

The Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Montefiore Medical Center and Washington Heights CORNER Project (WHCP) collaborated on this cross-sectional study. The study was deemed exempt by affiliated institutional review boards.

2.1 Setting

WHCP is a community-based harm reduction agency that provides syringe exchange and diverse social services within an area of New York City that is severely impacted by drug use, HIV/AIDS, and Hepatitis C. Its mission is to improve the health and quality of life of people who use drugs. From its office, WHCP provides: sterile syringes; case management; referrals for medical, dental, or addiction treatment; HIV risk reduction education and interventions; and harm reduction counseling. WHCP serves more than 1,500 clients, the majority of whom are Hispanic or Black, male, 40–49 years old, and use injection drugs. Over a six week period, we recruited a convenience sample of WHCP’s syringe exchange participants who received office-based services.

2.2 Participants

Between July and August 2013, WHCP staff informed all clients receiving office-based services about the study and those interested were referred to the research staff. Eligibility criteria included: 1) at least 18 years of age; 2) fluent in English or Spanish; and 3) history of opioid use. Following referral to the study, research staff described study goals and procedures and obtained informed consent.

2.3 Data Collection

Participants completed a 25-minute 100-item interview in a private room at the WHCP office. Interviews were conducted in English or Spanish using audio computer-assisted self-interview (ACASI) technology, which plays an audio recording of questions as items are displayed on a computer screen. Participants entered responses directly on the computer. After completing the interview, participants were compensated with $10 in cash and a $5 transit pass.

2.4 Measures

Interviews focused on three domains: 1) prior use of buprenorphine (illicit and prescribed); 2) barriers to BMT; 3) interest in initiating BMT (overall interest in BMT, motivation, and likelihood of initiating BMT).

2.4.1 Illicit Buprenorphine Use

The Addiction Severity Index (ASI) was adapted to assess recent (i.e. within the previous 30 days) and lifetime (i.e. any regular use for ≥1 year) buprenorphine use (McLellan et al., 1992). For buprenorphine (and other substances on the ASI that can be prescribed), when participants answered that they had used at least one day of a substance, they were asked a follow-up question about whether the substance was prescribed to them. Participants were also asked directly, “Have you ever taken Suboxone that was NOT prescribed to you? (For example, have you ever taken Suboxone that was from the streets, from a friend, or from a family member?)” Participants reporting non-prescribed buprenorphine use on the ASI or answering yes to the previous question were considered to have used illicit buprenorphine. Participants were also asked whether they had been prescribed buprenorphine by a doctor, so participants could have had illicit buprenorphine use only, prescribed buprenorphine use only, or both illicit and prescribed buprenorphine use.

2.4.2 Barriers to BMT

We adapted a previously published questionnaire to measure self-perceived barriers to BMT (Kalichman, Catz, & Ramachandran, 1999). Participants were asked whether the following seven barriers had prevented them from receiving BMT, if they had wanted to start or continue treatment: inability to pay, unsure of where to obtain care, lack of transportation, having been treated poorly at the clinic, wanting to avoid being seen at the clinic, distrusting doctors, or lack of child care. Responses to each item were dichotomous (yes/no).

2.4.3 Interest in initiating BMT

We assessed overall interest in BMT, motivation for opioid addiction treatment, and likelihood of initiating BMT at three potential treatment locations.

2.4.3.1 Overall Interest

Agreement with the statement, “I am interested in starting treatment with Suboxone” was assessed on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). Those agreeing or strongly agreeing were considered to have overall interest in BMT.

2.4.3.2 Motivation

Motivation for opioid addiction treatment was assessed using three items that were adapted from the Stages of Change Readiness and Treatment Eagerness Scale (SOCRATES) (Miller & Tonigan, 1996). These items assessed problem recognition, desire to make changes, and taking action to reduce opioid use, which are important steps in changing addiction-related behaviors (Prochaska, 1996). Agreement with each statement was assessed on a 5-point Likert scale as above, and those agreeing or strongly agreeing to each item were considered to endorse that statement, and those endorsing all three items were considered to be motivated for treatment.

2.4.3.3 Likelihood of Initiating Treatment by Location

Likelihood of initiating BMT at different treatment locations was assessed in three items that each referenced a different location where BMT could potentially be prescribed (harm reduction agency, general medical clinic, or drug treatment program). Participants were asked whether they agreed with the statement, “It is very likely that I would start treatment,” if BMT was available at each location. Agreement with each statement was assessed on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree), and those agreeing or strongly agreeing were considered likely to initiate treatment at the potential location.

2.4.4 Covariates

Other data collected during the interviews included: demographic characteristics (age, gender, race/ethnicity, education, health insurance); current and lifetime substance use (from the Addiction Severity Index); presence of psychiatric co-morbidities (depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, other); experiences with different treatment options for opioid dependence (methadone maintenance, residential or inpatient, self-help groups, or other forms of group treatment) ; and awareness of BMT.

2.5 Data Analysis

To examine how illicit buprenorphine use was associated with barriers to BMT, we first excluded those who were unaware of buprenorphine. Then we compared the presence of each potential barrier to BMT between those with and without lifetime illicit buprenorphine use using chi-square tests. We conducted two sensitivity analyses. First, we excluded those who were prescribed buprenorphine at the time of the interview and repeated analyses. Then we excluded those who had ever been prescribed buprenorphine and repeated analyses again. Because these exclusions did not significantly impact findings, results are not presented. To examine how illicit buprenorphine use was associated interest in initiating BMT, we compared three measures of interest in BMT between those with and without lifetime illicit buprenorphine use using chi-square tests. First, we compared the proportion reporting overall interest by illicit buprenorphine use. We also compared the mean level of interest using a Student’s t-test. Second, we compared the proportion reporting motivation for treatment by illicit buprenorphine use. Third, we compared the likelihood of initiating BMT at each location by illicit buprenorphine use. A separate comparison was made for each of the three potential treatment locations (harm reduction agencies, general medical clinics, drug treatment programs). All analyses were repeated using recent instead of lifetime illicit buprenorphine use, which did not significantly change any findings, so these data are not presented.

3. Results

3.1 Participant Characteristics

In this sample of 110 syringe exchange participants, seven had no history of regular lifetime opioid use, one had missing data, and these were excluded from analyses. Of the 102 remaining, the median age was 47 years, and most participants were male (73%), high school graduates (77%), had Medicaid (68%), and had used heroin regularly in their lifetime (98%). Active substance use was common, with 80% reporting heroin use in the past 30 days, 58% with cocaine use, 54% with methadone use, and 44% with benzodiazepine or other sedative use. Most reported a history of injection drug use (71%) and experience with opioid addiction treatment (90%) (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of syringe exchange participants by history of illicit buprenorphine use

| Sociodemographic Characteristics | Total (N = 102) N (%) |

Illicit Use (N = 57) N (%) |

No Illicit Use (N = 45) N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Age median (IQ range) | 47 (41–51) | 44 (38–49)* | 49 (44 – 55) |

| Male | 73 (72) | 44 (77) | 29 (64) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic | 43 (42) | 21 (37) | 22 (49) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 30 (29) | 21 (37) | 9 (20) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 20 (20) | 10 (18) | 10 (22) |

| Other | 9 (9) | 5 (9) | 4 (9) |

| Medicaid | 68 (67) | 34 (60) | 34 (76) |

| High School Graduate or GED | 77 (75) | 46 (81) | 31 (69) |

| Employed | 16 (16) | 9 (16) | 7 (16) |

| Stable Housing | 36 (35) | 21 (37) | 15 (33) |

| Receive services at WHCP (≥ weekly) | 77 (76) | 44 (77) | 33 (73) |

| History of incarceration | 84 (83) | 47 (82) | 37 (84) |

| Injecting drug use (ever) | 72 (71) | 46 (81)* | 26 (58) |

| Substance Use (current) | |||

| Any Opioid | 99 (97) | 56 (98) | 43 (96) |

| Heroin | 82 (80) | 53 (93)* | 29 (64) |

| Methadone | 55 (54) | 32 (56) | 23 (51) |

| Opioid Analgesics | 48 (47) | 33 (58)* | 15 (33) |

| Buprenorphine | 26 (25) | 25 (44)* | 1 (2) |

| Cocaine | 60 (58) | 33 (58) | 27 (60) |

| Amphetamine | 9 (9) | 6 (11) | 3 (7) |

| Sedatives/Benzo | 45 (44) | 31 (54)* | 14 (31) |

| Treatment History (ever) | |||

| Methadone Maintenance | 61 (60) | 36 (63) | 25 (56) |

| Residential Treatment | 80 (78) | 50 (88)* | 30 (67) |

| Self-Help Groups | 73 (72) | 47 (82)* | 26 (58) |

| Prescribed Buprenorphine | 32 (32) | 23 (41)* | 9 (20) |

| Buprenorphine Interest | |||

| Overall Interesta | 18 (55) | 29 (54) | 16 (36) |

| Overall Interest (mean ± SD)b | 3.11 (± 1.34) | 3.37 (± 1.29)* | 2.80 (± 1.34) |

| Motivated for Treatment | 46 (45) | 29 (51) | 17 (38) |

| Likely to start (Harm Reduction Agency)c | 54 (68) | 37 (82)* | 17 (50) |

| Likely to start (General Medical Clinic)c | 47 (59) | 31 (69) | 16 (47) |

| Likely to start (Drug Treatment Program)c | 49 (62) | 30 (67) | 19 (56) |

4 excluded because currently prescribed buprenorphine

Student’s T-test

N = 79

p < 0.05 (comparison vs. no illicit use)

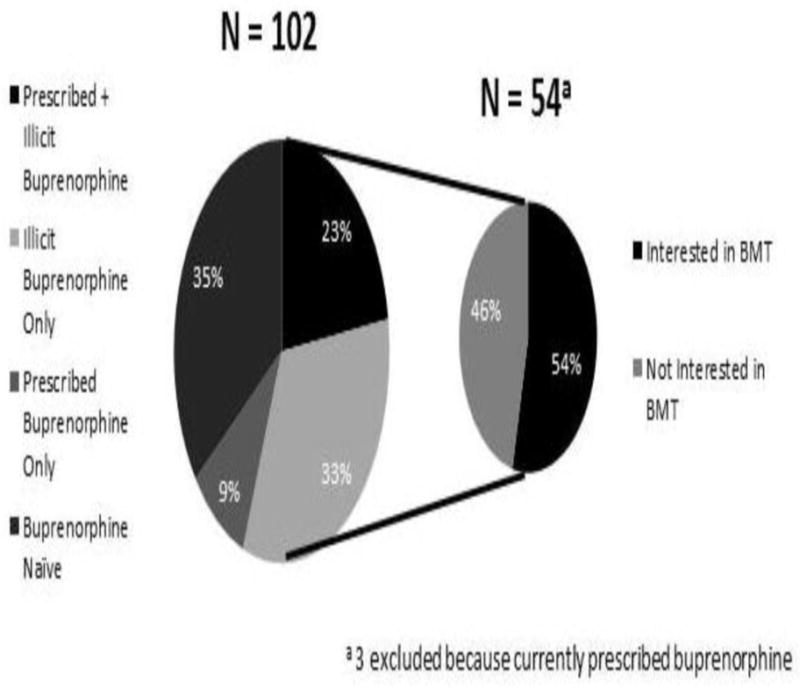

3.2 Use of Illicit Buprenorphine

Overall 57 participants had used illicit buprenorphine, including 19 within the previous 30 days. Of the 57 with illicit buprenorphine use, 34 had used illicit buprenorphine only and 23 had used both illicit and prescribed buprenorphine. Another nine participants had used prescribed buprenorphine only (see Figure 1). Those with (vs. without) illicit buprenorphine use were younger (median age: 44 vs. 49, p = 0.01), and reported higher rates of heroin (93% vs. 64%, p < 0.01), opioid analgesics (58% vs. 33%, p = 0.01), and sedative (54% vs. 31%, p = 0.02) use, and higher rates of participation in residential treatment (88% vs. 67%, p = 0.01) and self-help groups (82% vs. 58%, p < 0.01) (see Table 2). Seventy-four percent of illicit buprenorphine users reported that buprenorphine had helped them cut down or stop using illicit opioids.

Figure 1.

Illicit buprenorphine use and interest in BMT among syringe exchange participants

Table 2.

Perceived barriers to BMT by history of illicit buprenorphine use (n=93)a

| Perceived Barrier | Illicit Use (N = 56) N (%) |

No Illicit Use (N = 37) N (%) |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Did not know where to get buprenorphine treatment | 36 (64)* | 11 (30) |

| Could not pay | 21 (38) | 10 (27) |

| Did not have transportation | 17 (30) | 9 (24) |

| Treated poorly by treatment center staff | 7 (13) | 6 (16) |

| Did not want to be seen at treatment center | 7 (13) | 6 (16) |

| Did not trust treating physician | 3 (5) | 5 (14) |

| Did not have child care | 2 (4) | 4 (11) |

9 excluded because unaware of buprenorphine

p < 0.05

3.3 Barriers to BMT

Nine participants were unaware of buprenorphine. Of the 93 participants who were aware of buprenorphine, the most common barrier to BMT was “did not know where to go to get treatment,” which was reported by 51% of the sample. This barrier was significantly more common among those with (vs. without) illicit buprenorphine use (64% vs. 36%, p < 0.01). Other common barriers included “could not pay” and “lacked transportation” (see Table 2).

3.4 Interest in BMT

Of the 98 participants who were not currently prescribed buprenorphine, approximately half were interested in initiating BMT. The proportion with overall interest in BMT appeared to be greater among those with (vs. without) illicit buprenorphine use (54% vs. 36%, p = 0.09), but this difference was not statistically significant. The mean level of interest was significantly greater among those with (vs. without) illicit buprenorphine (3.37 ± 1.29 vs. 2.80 ± 1.34, p = 0.03). Among illicit buprenorphine users, 77% recognized they had a problem with opioids, 81% desired to make changes in their opioid use, 63% reported they were taking action to cut down or stop using opioids, and 51% were motivated for treatment. These attitudes were similar among those with and without illicit buprenorphine use. When harm reduction agencies were proposed as a potential treatment location, the perceived likelihood of starting BMT was higher among those with (vs. without) illicit buprenorphine use (82% vs. 50%, p < 0.01), but not when other potential treatment locations were proposed (see Table 1).

4. Discussion

Among NYC syringe exchange participants with a history of regular lifetime opioid use, more than half had used illicit buprenorphine; however, barriers to initiating BMT were common. More participants had used illicit than prescribed buprenorphine, and nearly two-thirds of illicit buprenorphine users did not know where to go for treatment. Notably, more than half of those with illicit buprenorphine use were interested in initiating BMT, and all but one of these interested participants had experienced at least one barrier to BMT (data not shown). Therefore, relatively minor interventions addressing these barriers to BMT could dramatically improve access to BMT.

Our study provides new knowledge regarding access to BMT. Overall, more than half of participants were unaware of where to go for treatment, while far fewer reported barriers such as costs, mistrust, or stigma. Internet-based tools are available to help PWUD identify buprenorphine treatment providers in their communities, but our sample of syringe exchange participants was mostly unstably housed with low educational attainment, which could have impacted utilization of internet-based resources. Referrals to BMT were available from WHCP, but infrequent prior to this study, and the agency is currently participating in an intervention to train staff to facilitate referrals to BMT. In New York City, opioid treatment programs primarily offer methadone maintenance treatment and not BMT, so even treatment experienced participants may not have known how to access BMT (Oral Communication, H. Kunins, New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene). In regards to financial barriers, New York State Medicaid covers BMT, which probably mitigated costs as a barrier. This emphasizes the importance of state-level policies to secure access to treatment (Ducharme & Abraham, 2008); however, outreach and education are also necessary to link marginalized PWUDs to buprenorphine treatment providers.

Our finding that 55% of syringe exchange participants had used illicit buprenorphine is consistent with other data demonstrating substantial buprenorphine diversion. In other settings, use of illicit buprenorphine has varied: in Baltimore, 23% of opioid users had recent use (within 3 months), while in Providence, RI and rural Appalachia, about three-quarters of opioid users had ever used illicit buprenorphine (Bazazi et al., 2011; Genberg et al., 2013; Lofwall & Havens, 2012). We did not ask participants about their reason for using illicit buprenorphine, but about half were interested in initiating BMT and motivated for opioid addiction treatment, and more than three-quarters were likely to initiate treatment if it were offered at easily accessible locations. Paradoxically, improving access to BMT could reduce buprenorphine diversion by reducing the demand for illicit buprenorphine.

The tension between increasing access to BMT and reducing diversion is critical because even if many illicit buprenorphine users are “self-treating” opioid addiction, as has been previously reported, there have been deaths from buprenorphine-related overdoses among opioid naïve persons, especially in the setting of polysubstance use or accidental ingestion among children (Kim, Smiddy, Hoffman, & Nelson, 2012). If improving access to BMT also resulted in diversion to opioid naïve polysubstance users, there could be an overall negative public health impact; however, if concern about diversion resulted in stricter regulations, access to treatment could suffer, widening the treatment gap, and making it more difficult for marginalized PWUD to initiate BMT (Clark & Baxter, 2013). Additional data are necessary to estimate the prevalence of buprenorphine abuse; however, encouraging illicit buprenorphine users to initiate BMT instead of self-treating their addiction has clear advantages, such as education about risks, monitoring for other substance use, and treatment of co-morbid chronic conditions (Rowe, Jacapraro, & Rastegar, 2012; Schuman-Olivier et al., 2013). This requires access though, and even in a setting like New York City with numerous opioid treatment programs, capacity for treatment is only half of what is needed (McNeely et al., 2012). Thus, efforts to improve access to BMT are urgently needed.

Our findings regarding acceptability of buprenorphine treatment at harm reduction agencies are also novel, and offer a potentially promising approach to improve BMT access. Those using illicit buprenorphine are a key group to target, because they often did not know where to go for BMT, but 83% reported they were very likely to initiate treatment, if BMT was offered onsite at harm reduction agencies. Previous data regarding referral to methadone maintenance treatment programs from harm reduction agencies suggest that initiation of treatment following referral may be as low as 5% (Kidorf et al., 2005). BMT may be prescribed in office-based settings, so directly initiating BMT onsite at harm reduction agencies may be a better option than referral to address the treatment gap. One pilot program that offered BMT from a harm reduction agency reported treatment retention of 42% at 12 months (Stancliff et al., 2012). Thus, additional studies regarding the safety and effectiveness of initiating BMT at harm reduction agencies are warranted.

Our study has several limitations. We sampled participants of a single community-based syringe exchange program in New York City, and findings may not be generalizable to other settings or geographic areas. Interest in treatment and likelihood of initiating treatment may be better proxies for acceptability of treatment than predictors of actually initiating treatment. Additionally, we could not differentiate between those who intended to initiate BMT as a way to cut down on opioid use, and those who had other goals for initiating treatment.

Though buprenorphine maintenance treatment is gradually entering the mainstream, treatment access continues to be problematic, especially for marginalized syringe exchange participants. These data can guide the development of interventions to facilitate initiation of BMT. Medication-assisted treatments, such as buprenorphine, continue to be the most efficacious treatments for opioid addiction, but without efforts to engage those who are out of treatment, the tragic consequences of opioid addiction will continue to grow.

Highlights.

We conducted a cross-sectional study of illicit buprenorphine use among syringe exchange participants at a harm reduction agency in New York City.

More than half of participants had used illicit buprenorphine, but only one-third had ever been prescribed buprenorphine maintenance treatment (BMT).

The most common barrier to BMT was not knowing were to go for treatment.

Most illicit buprenorphine users were interested in initiating BMT.

Prescribing BMT from harm reduction agencies could increase access to BMT.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NIH K23DA034541 (PI: Fox); NIH R34DA031066 (PI: Cunningham); the Center for AIDS Research at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine and Montefiore Medical Center (NIH AI-51519); NIH R25DA023021 (PI: Arnsten); and the David E. Rogers Fellowship Program of the New York Academy of Medicine (Chamberlain). These sources had no further role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the report for publication. We also thank Yuming Nin for his contribution to data management, the staff and participants of Washington Heights Corner Project, and the Addiction Research Affinity Group of the Division of General Internal Medicine at Montefiore Medical Center/Albert Einstein College of Medicine.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Awgu E, Magura S, Rosenblum A. Heroin-dependent inmates’ experiences with buprenorphine or methadone maintenance. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2010;42(3):339–346. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2010.10400696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazazi AR, Yokell M, Fu JJ, Rich JD, Zaller ND. Illicit use of buprenorphine/naloxone among injecting and noninjecting opioid users. J Addict Med. 2011;5(3):175–180. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0b013e3182034e31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital signs: overdoses of prescription opioid pain relievers-United States, 1999–2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60:1487–1492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital signs: overdoses of prescription opioid pain relievers and other drugs among women-United States, 1999–2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62:537–542. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark RE, Baxter JD. Responses of state Medicaid programs to buprenorphine diversion: doing more harm than good? JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(17):1571–1572. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.9059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham CO, Roose RJ, Starrels JL, Giovanniello A, Sohler NL. Prior buprenorphine experience is associated with office-based buprenorphine treatment outcomes. J Addict Med. 2013;7(4):287–293. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0b013e31829727b2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dasgupta N, Bailey EJ, Cicero T, Inciardi J, Parrino M, Rosenblum A, Dart RC. Post-marketing surveillance of methadone and buprenorphine in the United States. Pain Med. 2010;11(7):1078–1091. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2010.00877.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ducharme LJ, Abraham AJ. State policy influence on the early diffusion of buprenorphine in community treatment programs. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2008;3:17. doi: 10.1186/1747-597X-3-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox AD, Shah PA, Sohler NL, Lopez CM, Starrels JL, Cunningham CO. I Heard About It From a Friend: Assessing Interest in Buprenorphine Treatment. Subst Abuse. 2014;35(1):74–9. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2013.804484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genberg BL, Gillespie M, Schuster CR, Johanson CE, Astemborski J, Kirk GD, Vlahov D, Mehta SH. Prevalence and correlates of street-obtained buprenorphine use among current and former injectors in Baltimore, Maryland. Addict Behav. 2013;38(12):2868–2873. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwin Mitchell S, Kelly SM, Brown BS, Schacht Reisinger H, Peterson JA, Ruhf A, Agar MH, O’Grady KE, Schwartz RP. Uses of diverted methadone and buprenorphine by opioid-addicted individuals in Baltimore, Maryland. Am J Addict. 2009;18(5):346–355. doi: 10.3109/10550490903077820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johanson CE, Arfken CL, di Menza S, Schuster CR. Diversion and abuse of buprenorphine: findings from national surveys of treatment patients and physicians. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;120(1–3):190–195. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Catz S, Ramachandran B. Barriers to HIV/AIDS treatment and treatment adherence among African-American adults with disadvantaged education. J Natl Med Assoc. 1999;91(8):439–446. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidorf M, Disney E, King V, Kolodner K, Beilenson P, Brooner RK. Challenges in motivating treatment enrollment in community syringe exchange participants. J Urban Health. 2005;82(3):456–467. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jti091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HK, Smiddy M, Hoffman RS, Nelson LS. Buprenorphine may not be as safe as you think: a pediatric fatality from unintentional exposure. Pediatrics. 2012;130(6):e1700–1703. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kissin W, McLeod C, Sonnefeld J, Stanton A. Experiences of a national sample of qualified addiction specialists who have and have not prescribed buprenorphine for opioid dependence. J Addict Dis. 2006;25(4):91–103. doi: 10.1300/J069v25n04_09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korthuis PT, Gregg J, Rogers WE, McCarty D, Nicolaidis C, Boverman J. Patients’ Reasons for Choosing Office-based Buprenorphine: Preference for Patient-Centered Care. J Addict Med. 2010;4(4):204–210. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0b013e3181cc9610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lofwall MR, Havens JR. Inability to access buprenorphine treatment as a risk factor for using diverted buprenorphine. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;126(3):379–383. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.05.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattick RP, Kimber J, Breen C, Davoli M. Buprenorphine maintenance versus placebo or methadone maintenance for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(2):CD002207. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002207.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Kushner H, Metzger D, Peters R, Smith I, Grissom G, Pettinati H, Argeriou M. The Fifth Edition of the Addiction Severity Index. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1992;9(3):199–213. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(92)90062-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeely J, Gourevitch MN, Paone D, Shah S, Wright S, Heller D. Estimating the prevalence of illicit opioid use in New York City using multiple data sources. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:443. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller W, Tonigan JS. Assessing drinkers’motivation for change: The Stages of Change Readiness and Treatment Eagerness Scale (SOCRATES) Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1996;10:81–89. [Google Scholar]

- Monte AA, Mandell T, Wilford BB, Tennyson J, Boyer EW. Diversion of buprenorphine/naloxone coformulated tablets in a region with high prescribing prevalence. J Addict Dis. 2009;28(3):226–231. doi: 10.1080/10550880903014767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy SM, Fishman PA, McPherson S, Dyck DG, Roll JR. Determinants of buprenorphine treatment for opioid dependence. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2014;46(3):315–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2013.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prochaska JO. A stage paradigm for integrating clinical and public health approaches to smoking cessation. Addict Behav. 1996;21(6):721–732. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(96)00031-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roman PM, Abraham AJ, Knudsen HK. Using medication-assisted treatment for substance use disorders: evidence of barriers and facilitators of implementation. Addict Behav. 2011;36(6):584–589. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.01.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe TA, Jacapraro JS, Rastegar DA. Entry into primary care-based buprenorphine treatment is associated with identification and treatment of other chronic medical problems. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2012;7(1):22. doi: 10.1186/1940-0640-7-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAMHSA. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Service Administration. Results from the 2011 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: National Findings. Rockville, MD: 2012. pp. 12–4713. NSDUH Series H-44, HHS Publication No. (SMA) [Google Scholar]

- SAMHSA. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. Treatment Episode Data Set (TEDS): 2000–2010. State Admissions to Substance Abuse Treatment Services; Rockville, MD: 2012. DASIS Series: S-63, HHS Publication No. SMA-12-4729. [Google Scholar]

- Savage SA, Abraham AJ, Knudsen HK, Rothrauff TC, Roman PM. Timing of buprenorphine adoption by privately funded substance abuse treatment programs: the role of institutional and resource-based interorganizational linkages. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2012;42(1):16–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2011.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuman-Olivier Z, Connery H, Griffin ML, Wyatt SA, Wartenberg AA, Borodovsky J, Renner JA, Weiss RD. Clinician beliefs and attitudes about buprenorphine/naloxone diversion. Am J Addict. 2013;22(6):574–580. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2013.12024.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuman-Olivier Z, Hoeppner BB, Weiss RD, Borodovsky J, Shaffer HJ, Albanese MJ. Benzodiazepine use during buprenorphine treatment for opioid dependence: clinical and safety outcomes. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;132(3):580–586. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohler NL, Weiss L, Egan JE, Lopez CM, Favaro J, Cordero R, Cunningham CO. Consumer attitudes about opioid addiction treatment: a focus group study in New York City. J Opioid Manag. 2013;9(2):111–119. doi: 10.5055/jom.2013.0152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stancliff S, Joseph H, Fong C, Furst T, Comer SD, Roux P. Opioid maintenance treatment as a harm reduction tool for opioid-dependent individuals in New York City: the need to expand access to buprenorphine/naloxone in marginalized populations. J Addict Dis. 2012;31(3):278–287. doi: 10.1080/10550887.2012.694603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein BD, Gordon AJ, Sorbero M, Dick AW, Schuster J, Farmer C. The impact of buprenorphine on treatment of opioid dependence in a Medicaid population: recent service utilization trends in the use of buprenorphine and methadone. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;123(1–3):72–78. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]