Abstract

MicroRNAs are small noncoding ribonucleotides that regulate mRNA translation or degradation and have major roles in cellular function. MicroRNA (miRNA) levels are deregulated or altered in many diseases. There is overwhelming evidence that miRNAs also play an important role in the regulation of glucose homeostasis and thereby may contribute to the establishment of diabetes. MiRNAs have been shown to affect insulin levels by regulating insulin production, insulin exocytosis, and endocrine pancreas development. Although a large number of miRNAs have been identified from pancreatic β-cells using various screens, functional studies that link most of the identified miRNAs to regulation of pancreatic β-cell function are lacking. This review focuses on miRNAs with important roles in regulation of insulin production, insulin secretion, and β-cell development, and will discuss only miRNAs with established roles in β-cell function.

Mature microRNAs (miRNAs) are small noncoding ribonucleotides (∼22 nt) capable of recognizing and binding to partially complementary sequences within the 3′ untranslated region (UTR) of specific mRNAs. Most miRNAs function by mediating the degradation or translational inhibition of mRNAs (1, 2). In rare cases, miRNAs also can affect translation and gene expression in a positive manner (3–5). They pair with the target mRNA through their seed region at the 5′ end (6). MiRNAs are transcribed as pri-miRNAs and processed to pre-miRNAs by the enzyme complex Drosha and DGCR8 within the nucleus (6). After transport into the cytoplasm pre-miRNAs are processed to mature miRNAs by the Dicer complex, and the obtained double-stranded RNA associates with the RNA-induced silencing complex that mediates the interaction of miRNAs with target mRNAs.

Most of the initial studies on miRNA function used deletions of Dicer (7), Drosha (8), DGCR8 (9), and Ago2 (10) genes. Although the homozygous deletion of Dicer is embryonic lethal in mice (11) and zebrafish (12), tissue-specific deletions of Dicer have been used to study the role of miRNAs in various cell types. The human genome contains more than 2500 mature miRNA sequences, which constitute greater than 5% of all genes. Many miRNAs exist in miRNA families with identical seed sequences (6). It is predicted that each miRNA family regulates more than 300 different target mRNAs and close to 50% of target mRNAs have binding sites for two or more miRNAs (6, 13, 14). It is estimated that miRNAs regulate greater than 75% of mRNAs in a cell (15). Thus, miRNAs play a critical role in the regulation of entire protein networks and signaling pathways. They are involved in development, neuronal cell fate, apoptosis, and cell proliferation. The abundance of many miRNAs is altered in various diseases including cancer, diabetes, neurological disorders, autoimmune and cardiovascular diseases. Although miRNAs play important roles in diverse aspects of signaling and metabolic control, the exact function and targets of most of the identified miRNAs remain unknown.

Maintaining normoglycemia requires the production and secretion of insulin, which then acts on insulin-sensitive tissues, including muscle, liver, and adipocytes. The first miRNA involved in glucose homeostasis was identified in pancreatic islets as micro-RNA (miR)-375 (16). Since then, many miRNAs have been identified with important functions in pancreatic β-cells (17, 18). This article focuses on miRNAs critical for β-cell function and reviews the current state of knowledge about miRNAs that regulate insulin gene expression, insulin secretion, and endocrine pancreas development. Therefore, this review discusses only a selected number of miRNAs that are abundant in pancreatic β cells and have established roles in modulation of β-cell function (Table 1).

Table 1.

List of miRs Important for Pancreatic β-Cell Function

| miRNA | Function | Targets | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| miR-7 | Endocrine pancreas development, Adult β-cell replication Insulin secretion | GATA6, Pax6 | 31–35, 40 |

| S6k1, eIF4E, Mknk1, Mknk2, Mapkap1 | 36 | ||

| Snca, Cplx1, Pfne2, Wipf2, Basp1 | 40 | ||

| miR-9 | Insulin secretion | Onecut-2, Sirt1 | 41, 45 |

| miR-15a/b | Endocrine pancreas regeneration | Ngn3 | 48 |

| miR-21 | Insulin secretion | 51 | |

| β-Cell apoptosis | Pdcd4 | 56 | |

| miR-24 | β-Cell proliferation | Men1 | 63 |

| Insulin biosynthesis | Sox6 | 23 | |

| β-Cell lipotoxicity | NeuroD, HNFa | 61 | |

| miR-29 | Insulin secretion | Mct1, Onecut2 | 63, 66 |

| β-Cell apoptosis | Mcl1 | 66 | |

| miR-30 | β-Cell differentiation Insulin secretion Insulin biosynthesis |

Vimentin, Snail1, Rfx6 | 32, 76 |

| NeuroD | 77 | ||

| Map4k4 | 75 | ||

| miR-33a/miR-145 | Insulin secretion | Abca1 | 78,79 |

| miR-124a | Endocrine pancreas development | FoxA2, Ngn3 | 48, 81 |

| Insulin secretion | Rap27 | 83 | |

| Islet amyloid polypeptide synthesis | FoxA2 | 84 | |

| miR-184 | Compensatory β-cell expansion | Ago2 | 29 |

| miR-200 | β-Cell specification | c-Maf, Fog2, Zeb1, Zeb2, Sox17 | 76, 85 |

| miR-375 | Pancreas development/compensatory β-cell expansion Insulin biosynthesis Insulin secretion |

Cadm1 | 88, 89 |

| Pdk-1 | 44 | ||

| Mtpn, HuD, Gephyrin, Ywhaz, Aifm1 | 16, 30, 89 |

Dicer1

Analysis of mice with β-cell specific deletion of Dicer1 provided the first evidence that miRNAs are important for pancreatic β-cell function (11, 19). Dicer1 was initially deleted in the developing endocrine pancreas around the embryonic day (E) 10.5 using the Pdx-1-Cre mice (20). These Dicer1-deficient mice were defective in all pancreatic lineages and displayed a significant loss of pancreatic β-cells and died shortly after birth by postnatal day 3. They had an abnormal islet structure and displayed a significant reduction in the number of neurogenin-3 (Ngn3)-expressing endocrine progenitors (19). This was the first evidence demonstrating that miRNAs are critical for endocrine pancreas development.

Although Dicer1 whole-body knockout mice are embryonic lethal (11), Dicer1-hypomorphic mice with 20% of Dicer1 expression in all tissues were found to be viable (21). Analysis of these Dicer1-hypomorphic mice revealed that all of the tissues of 8- to 10-week-old mice were histologically normal except for the pancreas. Although the development of the pancreas at the fetal and neonatal stages was normal, at 4 weeks of age, pancreas morphology was abnormal with the presence of small islets and cells that were double positive for insulin and glucagon (21). Despite this abnormal islet morphology, the mice displayed normal glucose tolerance and had normal insulin levels. It is not clear whether these mice developed some compensatory mechanisms or whether a low expression of Dicer1 is sufficient for normal development.

A different study found that mice with ablation of Dicer1 in adult endocrine pancreas using an inducible CreER transgene driven by the rat insulin promoter (RIP) (22) developed hyperglycemia and diabetes as adults (23). This was due to reduced insulin consent and insulin mRNA in Dicer1-deficient β-cells. However, β-cell mass and islet size were normal, whereas insulin1 and insulin2 mRNA levels were decreased by 70% (23). The reduction in insulin gene expression was associated with an increased expression of the transcriptional repressors Bhlhe22 and Sox6 (23).

The importance of miRNAs for normal β-cell function was further confirmed by two other studies that used RIP-Cre to delete Dicer1 (24, 25). The first study found that 80% of the Dicer1-deficient animals developed diabetes by 12 weeks of age. The development of the endocrine pancreas in these animals was normal; however, they were defective in insulin gene expression and glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS) (24). Immunostaining of the pancreas revealed that these mice had altered islet morphology and decreased β-cell mass. Furthermore, the number of insulin granules, including the docked granules, were decreased (24). The second study also found that RIP-Cre Dicer1 animals have reduced β-cell mass, decreased insulin biosynthesis, and impaired glucose tolerance (25). Thus, both studies confirmed that miRNAs are important for β-cell survival and for insulin biosynthesis in adult endocrine pancreas.

In a recent study, Dicer1 was deleted in NGN3+ endocrine progenitor cells (26). Although pancreas development in these mice was normal, they developed diabetes due to diminished insulin gene expression and β-cell mass. Interestingly, Dicer1-deficient mice displayed increased levels of neuronal transcripts preceding the onset of diabetes (26). The up-regulated neuronal genes were targets of the neuronal transcriptional repressor, RE1-silencing transcription factor REST. This suggests that miRNAs play a critical role in maintaining islet cell identity by suppressing neuronal gene expression via a direct targeting of the repressor, RE1-silencing transcription factor (26). In summary, the ablation of Dicer1 at various stages of endocrine pancreas development suggests that miRNAs play critical roles in insulin biosynthesis, insulin secretion, and β-cell development and survival.

Argonaute 2 (Ago2)

Ago2 is one of the four members of the argonaute family involved in mediating the interaction of miRNAs with their target mRNAs (27, 28). It also is the most abundant one in many tissues, including pancreatic β-cells. Ago2 has been recently shown to play an important role in insulin secretion and β-cell compensatory expansion (29, 30). The first study on Ago2 function in pancreatic β-cells found that miR-375 was the most enriched miRNA in Ago2-associated complexes in MIN6 cells. Using RNA interference experiments, it was shown that silencing of Ago2 in MIN6 cells enhances insulin secretion by increasing the expression of many of the miR-375 target genes, including Myotrophin, Gephryn, Ywhaz, and Aif1 (30). The same group later investigated Ago2 function in more detail using Ago2 knockout mice (29). Mice lacking Ago2 were unable to compensate for insulin resistance by expanding β-cell mass. This defect in compensatory β-cell expansion was due to the up-regulation of miR-375 target genes, including Cadm1, which is a negative regulator of proliferation (29). Furthermore, it was discovered that Ago2 levels are elevated during insulin resistance, which may be essential for the compensatory β-cell expansion observed in insulin-resistant state.

miR-7

Mir-7 is one of the evolutionarily conserved miRNAs that is encoded by three different genomic loci in mice and humans. MiR-7 is the most abundant and differentially expressed miRNA in both rodent and human islets (31–34). It also is highly expressed during human fetal pancreas development (31, 32). In the human developing pancreas, miR-7 expression was first detected at approximately 9 weeks of gestational age, and its expression peaked at approximately 14 and 18 weeks of gestational age in endocrine cells with rising hormone levels (31). Immunostaining data demonstrated that miR-7 colocalizes with insulin and glucagon in differentiating endocrine pancreas and is not expressed in acinar or ductal cells (31, 34).

Initial studies on miR-7 function have established a critical role for this miRNA in the regulation of differentiation of α- and β-cells in early endocrine pancreas development (34). MiR-7 is expressed in endocrine precursors in which it targets the paired box transcription factor 6 (Pax6), which is important for endocrine pancreas differentiation and acts downstream of Ngn3 (35). Consistent with the idea that miR-7 is an endocrine-specific miRNA, its expression is significantly reduced in Ngn3 knockout mice (34). Overexpression of miR-7 in the developing pancreas explants (E12.5 pancreatic buds) resulted in decreased insulin and Pax6 mRNA and protein levels. The effect of miR-7 overexpression on endocrine pancreas development was further studied using a knock-in model, in which the miR-7a-1 genomic sequence was inserted into the Rosa26 locus. To induce the expression of miR-7 in the pancreatic lineage, the Rosa26-miR-7 animals were crossed with Pdx-1-Cre mice. Overexpression of miR-7 in E13.5 pancreatic cells resulted in a significant down-regulation of insulin and glucagon mRNA levels. Furthermore, the Pax6 levels were decreased by 49%, but the expression of Cpa1 and Ptf1a, which are markers of exocrine lineage were not changed (34). Consistent with this, knockdown of miR-7 led to increased Pax6 levels, which was associated with increased insulin and glucagon RNA and protein levels (34). In conclusion, miR-7 functions as an inhibitor of α- and β-cell differentiation during endocrine pancreas development by acting upstream of Pax6.

Recent data suggest that miR-7a is the major mature isoform out of the two miR-7a and miR-7b isoforms, and mir-7a-2 is the major precursor that is expressed in adult pancreatic β-cells (36). Using mouse and human primary islets, it was demonstrated that miR-7a negatively regulates adult β-cell proliferation (36). Inhibition of miR-7a activated mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling and promoted the replication of adult β-cells both in mice and human primary islets (36). Activation of mTOR signaling by inhibition of miR-7a in β-cells was blocked by rapamycin, an inhibitor of mTOR. This confirmed that the effect of miR-7 on β-cell proliferation is by targeting mTOR signaling. The mTOR signaling pathway regulates cell proliferation and metabolism in response to various stimuli (37). Surprisingly, it was shown that miR-7a targets five of the mTOR signaling pathway components at the translational level, which include S6k1, eIF4E, Mknk1, Mknk2, and Mapkap1 (36). Previous data suggest that the activation of mTOR signaling using various strategies induces β-cell replication and expansion (38, 39). Thus, the modulation of miR-7a levels could be used as a new strategy to promote β-cell replication to replace the lost β-cells in persons with type 2 diabetes. Taken together, these data suggest that miR-7 negatively regulates endocrine pancreas development by targeting Pax6 (34) and adult β-cell replication by inhibiting mTOR signaling (36).

A very recent study in which miR-7a2 was either deleted or overexpressed in mice implicates miR-7a2 as a negative regulator of GSIS (Figure 1) (40). MiR-7a2-deficient mice displayed increased insulin secretion and the up-regulation of proteins that mediate the fusion of insulin granules with the plasma membrane in pancreatic β-cells. This included proteins involved in vesicle fusion (Snca, Cspa, and Cplx1), cytoskeleton dynamics (Pfne2, Wipf2, and Phactr1), and membrane targeting (Zdhhc9), which have been validated as direct targets of miR-7 (40). Overexpression of miR-7a2 in mice led to the inhibition of insulin secretion and β-cell dedifferentiation, which resulted in the development of diabetes. Interestingly, miR-7a levels were decreased in human islets of obese and diabetic patients. A decrease in miR-7a levels also was confirmed in islets of obese and diabetic mice (40). Thus, these data suggest that miR-7a is critical for GSIS and for β-cell adaptation to obesity and diabetes (Figure 2).

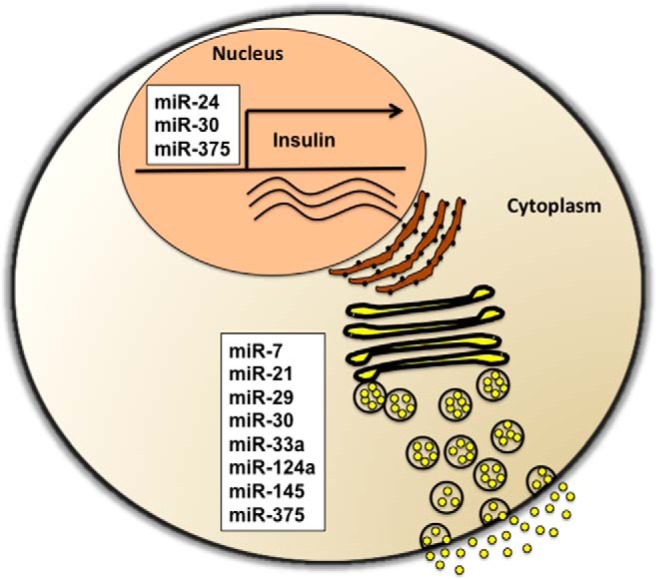

Figure 1.

MiRNAs involved in the regulation of insulin biosynthesis and insulin secretion in pancreatic β-cells. Insulin biosynthesis is regulated by miR-24, miR-30, and miR-375, whereas insulin exocytosis is modulated by miR-7, miR-29, miR-30, miR-33a, miR-124a, miR-145, and miR-375.

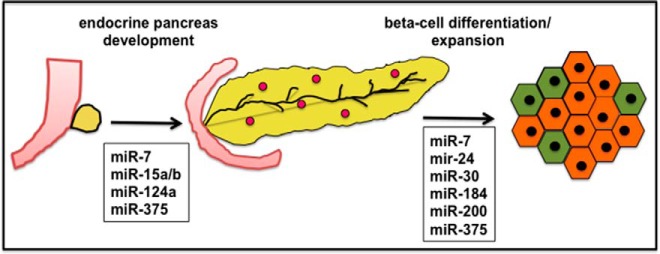

Figure 2.

MiRNAs important for endocrine pancreas development and β-cell differentiation and compensatory expansion. MiR-7, miR15a/b, miR124a, and miR-375 have been shown to regulate endocrine pancreas development. MiRNAs important for β-cell differentiation or expansion are miR-7, miR-24, miR-30, miR-184, miR-200, and miR-375.

miR-9

Analysis of miR-9 expression revealed that it is restricted to brain and pancreatic islets (41), and it is highly expressed during human pancreatic islet development (32). Detailed studies on miR-9 function demonstrated that the overexpression of miR-9 inhibits insulin secretion in response to glucose or potassium (KCl) in pancreatic INS-1E β-cells (41). The impaired insulin secretion in response to KCl by overexpression of miR-9 suggested that it regulates the insulin exocytosis machinery. Further analysis revealed that overexpression of miR-9 causes a 14-fold increase in granuphilin mRNA levels, whereas the levels of other Rab effectors were unchanged (41). Granuphilin is a Rab3/Rab27 GTPase effector that is associated with dense-core secretory granules and negatively regulates insulin exocytosis by controlling the docking of insulin granules (42). Granuphilin-deficient mice display abnormally increased insulin secretion (43). Using the TargetScan algorithm, the transcription factor Onecut2 was identified as a potential miR-9 target with three binding sites at 3′ UTR. Consistent with the idea that Onecut2 is a miR-9 target, its expression was reduced by the overexpression of miR-9. Furthermore, silencing of Onecut2 increased granuphilin expression and diminished insulin secretion by glucose (41). These data suggest that miR-9 negatively regulates insulin secretion mainly by inhibiting the translation of Onecut2 mRNA and by increasing the level of the Rab effector Granuphilin.

MiR-9 is encoded from three different genomic loci in humans as well as in mice that result in the same mature miR-9. Previous data suggest that miR-9 levels are induced by high glucose in INS-1E β-cells (44). This finding was recently confirmed in mouse pancreatic islets after the ip administration of glucose. Interestingly, mature miR-9 as well as miR-9–1 and miR-9–2 precursor levels were increased significantly only 60 minutes after the glucose injection, coinciding with the decline of insulin levels (45). Based on online prediction tools, sirtuin-1 (Sirt1) emerged as a potential miR-9 target. This was confirmed in the insulinoma β-TC-6 line, in which the transfection with pre-miR-9 caused a decrease in Sirt1 protein levels (45). This finding is consistent with a previous report that identified Sirt1 as miR-9 target in mouse embryonic stem cells (46). Sirt1 is a nuclear protein that deacetylates histones, transcription factors, and other proteins in a NAD-dependent manner. Sirt1 has been implicated in the regulation of GSIS and mice that overexpress Sirt1 in β-cells display enhanced GSIS (47). In summary, studies on miR-9 function in β-cells suggest that it negatively controls insulin secretion in part by targeting the transcription factor Onecut2 (41) as well as the NAD-dependent deacetylase Sirt1 (45).

miR-15

MiR-15a and miR-15b were identified in a screen for miRNAs that are up-regulated during pancreas regeneration and shown to be 200-fold up-regulated in the regenerating compared with the developing pancreas (48). Furthermore, it was shown that miR-15a/b targets Ngn3, which is normally expressed in all proendocrine cells during pancreas development (20, 48). Ngn3 is present in pancreatic endocrine progenitor cells but is not expressed in the mature islets or during pancreas regeneration (49), and Ngn3 null mice lack islets (50). Although Ngn3 transcript was detectable during endocrine pancreas regeneration after partial pancreatectomy, there was no Ngn3 protein present as previously reported (49). This suggested a posttranscriptional inhibition of Ngn3 levels during pancreas regeneration. The microRNAs, miR-15a and miR-15b, were highly expressed at day 3 of postpancreatectomy and shown to target Ngn3 (48). Inhibition of miR-15 increased Ngn3 levels in regenerating pancreatic endocrine cells and also increased the levels of (NeuroD) and Nkx2.2, two downstream targets of Ngn3. Furthermore, the overexpression of miR-15a/b in E12.5 pancreatic buds reduced the number of insulin- and glucagon-positive cells (48). Based on these data, it was concluded that increased expression of miR15a/b during pancreas regeneration down-regulates Ngn3 levels to induce the regeneration process.

miR-21

A screen for miRNAs that are up-regulated by exposure to proinflammatory cytokines or in prediabetic (NOD) mice led to the identification of miR-21 (51, 52). Treatment of MIN6 β-cells with either IL-1β or a cytokine mixture containing IL-1β, TNF-α, and IFN-γ led to an approximately 3-fold increase in miR-21 levels (51, 52). After testing various combinations of cytokines, IL-1β alone was the most potent inducer of miR-21. Proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β and TNF-α are produced by infiltrating leukocytes and islets and contribute to β-cell failure and establishment of diabetes (53). Analysis of miR-21 levels in prediabetic female NOD mice with normal blood glucose levels revealed a significant increase of miR-21 levels in islets of 8- and 13-week animals compared with 4-week animals. Overexpression of miR-21 in MIN6 β-cells did not have a significant effect on proinsulin mRNA levels or insulin content but decreased GSIS (51). MiR-21 overexpression also was associated with a decrease in (VAMP2), a SNARE protein essential for β-cell exocytosis and of the Rab3a GTPase (54–56). Treatment of MIN6 β-cells with 1 ng/mL IL-1β for 24 hours also resulted in decreased GSIS and VAMP2 and Rab3a levels. However, the inhibition of miR-21 in MIN6 β-cells treated with IL-1β prevented the decrease in the GSIS and VAMP2 but not Rab3a levels (51). The 3′ UTR of VAMP2 does not contain miR-21 binding sites, suggesting an indirect regulation of VAMP2 by miR-21. In summary, miR-21 plays a negative role in the regulation of β-cell function by reducing insulin exocytosis in response to cytokines.

MiR-21 also is critical in the regulation of β-cell apoptosis during type 1 diabetes (57). Expression of miR-21 is induced by members of the NF-κB family, c-Rel and p65 (58), and this increase in miR-21 levels results in the suppression of β-cell death by reducing the levels of the tumor suppressor protein programmed cell death 4 (Pdcd4) (52, 57, 59). Pdcd4 stimulates cell death by activating the apoptotic Bax family of proteins. The inactivation of Pdcd4 in pancreatic β-cells protects them from cell death in NOD and in streptozotocin (STZ)-treated C57BL/6 mice (57). These data suggest that the NF-κB-miR-21-Pdcd4 axis regulates β-cell death during type 1 diabetes. Thus, both studies found that miR-21 is up-regulated in response to inflammation in pancreatic β-cells and inhibits insulin exocytosis and β-cell death.

miR-24

Conditional deletion of Dicer1 in adult β-cells using tamoxifen-inducible RIP Cre-recombinase led to the development of diabetes due to significant decreases in insulin mRNA and insulin content (23). MiR-24 was identified as one of the four miRNAs (miR-26, miR-182, and miR-148) in β-cell Dicer1-deficient mice that are involved in regulation of insulin biosynthesis (23). Deletion of Dicer1 in adult β-cells resulted in a 70% reduction of insulin mRNA levels that was associated with elevated levels of the transcriptional repressors Sox6 and Bhlhe22 (60, 61). Inhibition of miR-24 in primary islet cultures resulted in a down-regulation of insulin mRNA and increased the levels of Sox6. Thus, conditional inactivation of Dicer1 decreases miR-24 levels and thereby increases Sox6 protein levels, which then represses insulin gene expression (23).

A different study implicated miR-24 in the suppression of two maturity-onset diabetes of the young (MODY) genes, HNF1α and NeuroD (62). MiR-24 levels were found to be up-regulated in the obese and diabetic db/db mice compared with the control mice and in HFD-fed mice. Additionally, miR-24 levels were increased by oxidative stress and high glucose. Overexpression of miR-24 in the MIN6 β-cell line reduced cell proliferation and decreased GSIS. These findings suggest that the up-regulation of miR-24 as seen in db/db or HFD-fed mice is likely via the ROS/PKC pathway and results in pancreatic β-cell dysfunction and thereby links glucolipotoxicity to type 2 diabetes (62). In this case, miR-24 has been shown to down-regulate the MODY proteins NeuroD1 and Hnf1-α.

Recently miR-24 also has been implicated in regulation of β-cell proliferation by controlling the availability of the tumor suppressor protein menin or multiple endocrine neoplasia-1 (MEN1) (63). Menin negatively regulates islet expansion and adaptation by increasing the production of cell cycle inhibitors (64). Ablation of MEN1 in mice results in pancreatic islet hyperplasia (65, 66), whereas its overexpression leads to the inability of islets to undergo proliferation and increase insulin production during pregnancy (67). Overexpression of miR-24 in the human β-cell line βlox5 decreased menin mRNA as well as protein levels. Furthermore, it decreased the expression of the cell cycle inhibitor p27, which is transcriptionally regulated by menin (63). Transfection of the βlox5 cell line with pre-miR-24 led to increased cell viability and proliferation. MiR-24 is encoded by two different loci, and menin has been shown to regulate miR-24 expression from both loci, suggesting the presence of a feedback loop between menin and miR-24 (63). These data suggest that miR-24 promotes β-cell proliferation in the endocrine pancreas by decreasing the levels of cell cycle inhibitors by directly targeting menin. In summary, miR-24 has multiple targets in β-cells and regulates β-cell proliferation and insulin production as well as glucolipotoxicity.

miR-29

There are three isoforms of miR-29 and all three are highly expressed in primary mouse islets (68). MiR-29 levels are increased in many tissues of diabetic animals, and recent data suggest that miR-29 negatively regulates GSIS (69). Studies in mouse islets have shown that miR-29 targets the plasma membrane monocarboxylate transporter-1 (MCT1; SLC16A1) and thereby affects insulin secretion (68). Although MCT1 is widely expressed in other tissues, its levels in β-cells are tightly regulated and kept low to avoid the uptake of circulating pyruvate or its export by MCT1, which would interfere with insulin release (68, 70, 71). Thus, this study suggests that miR-29 may control insulin release via the regulation of MCT1 transporter levels.

Increased miR-29 levels also have been observed in the islets of prediabetic NOD mice and in isolated mouse and human islets in response to exposure to proinflammatory cytokines (72). In this study, overexpression of miR-29 isoforms in MIN6 β-cells and islets interfered with GSIS, which was due to the suppression of the transcription factor Onecut2 expression. This led to an increase in granuphilin levels, which inhibits insulin release. Overproduction of miR-29 also promoted apoptosis by diminishing the levels of the antiapoptotic protein Mcl1 (72). Collectively these data suggest that miR-29 plays a critical role in cytokine-induced β-cell dysfunction during prediabetes.

A recent analysis of 5′-shifted isomiRs in β-cells identified miR-29 as one of most significant miRNA families that regulates β-cell function and is associated with type 2 diabetes (73). MiR-29a levels are up-regulated in skeletal muscle, liver, and white adipose tissue, and this up-regulation is associated with insulin resistance in GK rats (74–77). In conclusion, the up-regulation of miR-29 levels may contribute to type 2 diabetes via decreased GSIS as well as by mediating insulin resistance in peripheral tissues. In agreement with this idea, miR-29a levels also are increased in the serum of type 2 diabetes patients (78), suggesting that miR-29 family of miRNAs may serve as potential biomarkers for diabetes.

miR-30

The members of the miR-30 family are highly expressed in human fetal pancreas and are involved in the regulation of epithelial-mesenchymal transition (32, 79). They inhibit the translation of mesenchymal mRNAs, such as vimentin and Snail1, and thereby enable the differentiation of pancreatic mesenchymal cells into insulin-producing islet-like cells (32).

The miR-30 family members have different functions and targets. MiR-30d has been previously shown to be high glucose induced and to regulate the levels of the β-cell transcription factor MafA but has no effect on Pdx-1 and NeuroD1 expression (80, 81). MafA is not a direct target of miR-30d. Instead, miR-30d suppresses the levels of the TNF-α-activated kinase Map4k4 and thereby leads to increased MafA levels and insulin gene transcription (81). However, how the regulation of Map4k4 levels by miR-30d in the end leads to increased expression of MafA remains unknown. In a different study, miR-30d was identified as one of the miRNAs that is up-regulated during differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells (hPSCs) to insulin-producing β islet-like cells and shown to target the transcription factor Rfx6 (82). Interestingly, in both studies miR-30d regulates the levels of β-cell transcription factors.

MiR-30a-5p has the same seed sequence as miR-30d and has been implicated in glucotoxicity-induced β-cell dysfunction. MiR-30a-5p levels increase in response to glucotoxic conditions, and the overexpression of mir-30a-5p decreases insulin production and GSIS by suppressing the expression of the transcription factor Beta2/NeuroD (83). MiR-30a-5p levels also were increased in db/db mice and injection of anti-miR-30a-5p into db/db animals led to a significant reduction of nonfasting blood glucose levels (83). It is interesting that despite the fact that miR-30d and miR-30a-5p have the same seed region and differ only in one nucleotide, they target different genes in β-cells. In summary, the existing data suggest that the miR-30 family regulates the expression of various transcription factors in β-cells.

miR-33a and miR-145

MicroRNAs involved in regulation of cholesterol homeostasis in pancreatic β-cells have been shown to negatively regulate GSIS. Increased expression of the miRNAs miR-33a and miR-145 in murine islets cause a reduction in GSIS by increasing cholesterol levels by targeting the expression of the ATP-binding cassette transporter 1 (Abca1) (84, 85). Abca1 is important for the regulation of cholesterol homeostasis and regulates plasma HDL levels by causing cholesterol efflux. β-Cell-specific deletion of Abca1 leads to impaired glucose tolerance and β-cell function (86). On the other hand, inhibition of miR-33a or miR-145 expression in isolated islets increases Abca1 and decreases cholesterol levels, leading to enhanced GSIS (84, 85). Interestingly, miR-145 levels are decreased in response to high levels of glucose, which stimulates GSIS (85). These findings suggest that miR-33a and miR-145 may negatively impact GSIS by suppressing the levels of the Abca1 transporter and thereby reducing cholesterol efflux.

miR-124a

miR-124a consists of three isoforms (miR-124a1, miR-124a2, and miR-124a3) encoded by different genes and has been implicated in the regulation of insulin secretion and expression of β-cell-specific genes as well as pancreas development (48, 87, 88). The first study that implicated miR-124a in the regulation of β-cell function showed that the expression of miR-124a2 isoform increases during pancreas development. Furthermore, it was shown that it targets FoxA2, a transcription factor that plays an important role in β-cell differentiation (87). Consistent with this finding, the FoxA2 target genes Pdx-1, Kir6.2, and Sur-1 also were regulated by miR-124a2 (87). A role for miR-124a in endocrine pancreas development was confirmed by another group that showed that Ngn3, a transcription factor essential for β-cell differentiation, is a target of miR-124a (48). In this study miR-124a and other miRNAs were found to be expressed after a partial pancreatectomy in mice and to inhibit Ngn3 expression to allow β-cell regeneration.

Later in a separate study, miR-124a was identified as one of several miRNAs that regulate basal insulin secretion by increasing the levels of insulin exocytosis proteins SNAP25 Rab3A, and synapsin-1A and by decreasing Rab27A and Noc2 levels. Of these proteins, only Rab27A was shown to be a direct target of miR-124a (89). It is likely that the effect of miR-124a on insulin exocytosis may be partly mediated by directly targeting FoxA2, which regulates the expression of the channel subunits, Kir6.2 and Sur1. A recent publication suggests that the thioredoxin-interacting protein negatively regulates miR-124a expression (90). Inhibition of miR-124a by TXNIP stimulates the expression of the IAPP by blocking the suppression of FoxA2 (90). Based on these published data, miR-124a has important functions in β-cell development as well as insulin secretion and β-cell gene expression. All of these functions of miR-124a may be due to its ability to target FoxA2 in pancreatic β-cells.

miR-184

MiR-184 is important for the regulation of β-cell expansion during the insulin-resistant state (29). In pancreatic islets, miR-184 targets Ago2, which is part of the RNA-induced silencing complex required for targeting of mRNAs by miRNAs. Loss of Ago2 blocks the compensatory expansion of β-cells in response to insulin resistance by causing an increased expression of miR-375 targets (29, 30). Interestingly, miR-184 is silenced in the islets of insulin-resistant mice and humans, which results in an increased expression of Ago2 and in compensatory β-cell expansion (29). Forced expression of miR-184 in ob/ob diabetic mice decreases Ago2 levels and blocks the compensatory expansion of β-cells. However, the exact mechanisms that regulate miR-184 levels during normal or insulin-resistant states remain to be determined. In summary, miR-184 plays a key role in the regulation β-cell expansion by targeting Ago2 during the insulin-resistant state.

miR-200

The miR-200 family members (miR200a, miR-200b, miR-200c, miR-141, and miR-429) have been shown to play a role in β-cell specification. A recently published study shows that miR-200c is highly abundant in β-cells and functions to repress glucagon expression by targeting the transcription factors cMaf and Fog2, which normally stimulate glucagon gene expression (91). As expected, the level of miR-200c in α-cells was barely detectable. Forced expression of miR-200c in the α-cell line αTC6 led to a decreased expression of glucagon by the down-regulation of cMaf and Fog2 levels (91).

MiR-200a was found to be induced during the differentiation of hPSCs to insulin-producing β-islet-like cells (82). In this system, miR-200a was shown to target ZEB 1 and ZEB2 transcription factors involved in epithelial-mesenchymal transition by repressing E-cadherin (CDH1) expression (82, 92). Furthermore, miR-200a also has been shown to target Sox17 in hPSCs, a transcription factor critical for endoderm specification of definitive endoderm. Altogether these findings implicate the members of miR-200 family in the regulation of β-cell specification and development.

miR-375

MiR-375 was the first miRNA identified from pancreatic β-cells because of its high abundance in the endocrine pancreas. Initial studies on miR-375 demonstrated that it as a negative regulator of insulin secretion and targets myotrophin (Mtpn) expression (16). Mtpn is an important regulator of actin depolymerization and granule fusion (16, 93). Thus, in mature β-cells, miR-375 regulates insulin secretion at the level of vesicle fusion with the plasma membrane (16). A recent follow-up of miR-375 function in MIN6 cells suggests that miR-375 globally affects glucose-induced insulin secretion by suppressing the expression of Gephyrin, Ywhaz, Aifm1, and Mtpn (30). This study also demonstrated that miR-375 is one of the most enriched miRNAs present in Ago2-associated complexes. Interestingly, similar to the inhibition of miR-375, the loss of Ago2 in MIN6 cells results in enhanced insulin release and increased expression of miR-375 target genes (30). In conclusion, miR-375 and Ago2 appear to have similar roles in pancreatic β-cells and negatively regulate GSIS.

Another target of miR-375 is 3′-phosphoinositide-dependent kinase-1 or Pdk1 in pancreatic β-cells (44). By targeting PDK-1, miR-375 causes a decrease in the glucose regulation of insulin gene expression and DNA synthesis in INS-1E β-cells. Interestingly, miR-375 precursor levels were decreased by glucose itself in INS-1E cells as well as in primary rat islets (44). Moreover, miR-375 levels were decreased in the islets of the diabetic GK rats.

A different group found that miR-375 is highly expressed in the developing endocrine pancreas at E14.5, in which it was colocalized with Pdx-1. This suggested that miR-375 plays an important role during endocrine pancreas development (19, 32). Studies conducted in zebrafish demonstrated that miR-375 indeed plays a critical role in endocrine pancreas development and is essential for normal islet formation (94). These data were later confirmed in mice by the generation of miR-375 knockout mice, which had an increased number of α-cells but a reduced number of β-cells, causing excess glucagon production relative to insulin (95). The miR-375 knockout animals had hyperglycemia caused by hyperactivation of the glucagon axis and decreased β-cell proliferation. Ablation of miR-375 in the obese ob/ob mice blocked the ability of these mice to expand their β-cell mass in response to insulin resistance (95). Moreover, DNA microarray screens combined with a bioinformatics analysis revealed several potential miR-375 targets that are involved in the negative regulation of cell proliferation (95). It also is likely that miR-375 may promote β-cell proliferation by suppressing the proliferation of non-β-cells within the islet. Consistent with this idea, the expression of miR-375 together with miR-7 was induced during the differentiation of human embryonic stem cells to insulin-producing cells. In this study, the overexpression of miR-375 caused a decreased expression of gut-endoderm/pancreatic progenitor-specific markers, Hnf1β and Sox9 (96).

Interestingly, miR-375 has the potential to serve as a marker for β-cell death and diabetes (97). MiR-375 was present at high levels in the circulation of STZ-treated and nonobese diabetic NOD mice. In the STZ-administered mice, miR-375 levels dramatically increased prior to the onset of hyperglycemia. In the NOD mice, miR-375 in the circulation increased 2 weeks prior to diabetes onset (97). Thus, circulating levels of miR-375 may serve as a potential biomarker for diagnosis of prediabetes.

Concluding remarks

Recent studies clearly established a role for miRNAs in regulation of pancreatic β-cell function. Although the human genome encodes for more than 2500 mature miRNAs, only a few of these miRNAs have been implicated to have a role in β-cell function. Thus, the role of most miRNAs in β-cells is unknown and requires further investigation.

Analysis of miRNA function in β-cells and other tissues is complicated by the fact that the manipulation of a single miRNA may not have a drastic effect because miRNAs exist in families that contain the same seed region. Furthermore, almost 50% of miRNA targets contain binding sites for two or more miRNAs. Thus, miRNAs can synergize or antagonize the expression of target mRNAs, complicating studies on single miRNA function. Another complexity associated with miRNAs is that there are many miRNA isomers that have varied seed regions and target a different set of genes than the original miRNA (73). It is interesting that many miRNAs are encoded by different genomic loci that result in the same mature miRNA and target mainly the same set of genes. Both miR-7 and miR-9 are encoded by three different genomic loci, leading to the same mature miRNA. This raises the question of whether pre- or pri-miRNAs also may have a function that is different from that of the mature miRNA.

The complex action of miRNAs is demonstrated by the fact that they may regulate different processes within the same cell. For example, miRNA-375 has been shown to be involved in β-cell development as well as in insulin secretion by targeting different mRNAs (16, 30, 95). The same is true for miR-24, which causes glucolipotoxicity when up-regulated by targeting the Hnf1α and NeuroD1 MODY mRNAs (62, 92). However, it also can regulate insulin gene transcription by targeting the transcriptional repressors Sox6 and Bhlhe22 (62, 92) and β-cell proliferation by altering the levels of the transcriptional regulator menin (63).

MiRNAs have been shown to be abundant in circulation, released either from dead cells or the exosomes, and represent important biomarkers for the progression of many diseases. The number of circulating miRNAs that are associated with diabetes are steadily increasing. Some of these miRNAs including miR-375 may be useful biomarkers for the prognosis of prediabetes (97).

One future challenge for the miRNA field will be to determine the mechanisms that regulate miRNA levels in pancreatic β-cells during development and in mature β-cells. The abundance of many miRNAs is altered during diabetes, including miR-184, which is silenced during insulin resistance to allow for compensatory β-cell expansion (29). However, the mechanisms that lead to the silencing of miR-184 during the insulin-resistant state remain unknown. A detailed understanding of the regulation of miRNA levels during physiological as well as pathophysiological conditions will be critical in the development of novel strategies for combating miRNA-related diseases. Furthermore, the development of new techniques that allows the analysis of genome-wide transcription and the proteome in a single cell will accelerate our understanding of metabolic regulation by miRNAs. Advances in miRNA-based therapies can be extremely powerful in combating diseases, such as diabetes, especially if they are cell type specific because most miRNAs are ubiquitously expressed (98). There are already several ongoing clinical trials using miRNA-based therapies, indicating that the manipulation of miRNA levels in human patients is a feasible strategy to treat various diseases.

Acknowledgments

We apologize to all authors whose original publications could not be cited or discussed in this review due to space limitations.

This work was supported by Grant R01DK067581 from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; Grant P20RR020171 from the National Institutes of Health/National Center for Research Resources; Grant 1-05-CD-15 from the American Diabetes Association; and Grant UL1TR000117 from the National Institutes of Health Clinical and Translational Science Awards.

Disclosure Summary: The author has nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- Abca1

- ATP-binding cassette transporter 1

- Ago2

- argonaute 2

- E

- embryonic day

- GSIS

- glucose-stimulated insulin secretion

- FoxA2

- Forkhead A2

- Hnf1

- hepatocyte nuclear factor-1

- hPSC

- human pluripotent stem cell

- MCT1

- monocarboxylate transporter-1

- MEN1

- multiple endocrine neoplasia-1

- miR

- microRNA

- miRNA

- microRNA

- MODY

- maturity-onset diabetes of the young

- mTOR

- mammalian target of rapamycin

- Mtpn

- myotrophin

- NeuroD

- neurogenic differentiation

- Ngn3

- neurogenin-3

- NOD

- nonobese mouse model of autoimmune diabetes

- Pax6

- paired box transcription factor 6

- Pdcd4

- programmed cell death 4

- PDK-1

- protein kinase-1

- Rab

- renin-angiotensin system oncogene family

- RIP

- rat insulin promoter

- Sirt1

- sirtuin-1

- STZ

- streptozotocin

- UTR

- untranlsated region

- VAMP2

- vesicle-associated membrane protein-2

- ZEB

- zinc finger E-box binding homeobox.

References

- 1. Lau NC, Lim LP, Weinstein EG, Bartel DP. An abundant class of tiny RNAs with probable regulatory roles in Caenorhabditis elegans. Science. 2001;294(5543):858–862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lagos-Quintana M, Rauhut R, Lendeckel W, Tuschl T. Identification of novel genes coding for small expressed RNAs. Science. 2001;294(5543):853–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Orom UA, Nielsen FC, Lund AH. MicroRNA-10a binds the 5′UTR of ribosomal protein mRNAs and enhances their translation. Mol Cell. 2008;30(4):460–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Place RF, Li LC, Pookot D, Noonan EJ, Dahiya R. MicroRNA-373 induces expression of genes with complementary promoter sequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(5):1608–1613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Vasudevan S, Tong Y, Steitz JA. Switching from repression to activation: microRNAs can up-regulate translation. Science. 2007;318(5858):1931–1934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell. 2009;136(2):215–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Harfe BD, McManus MT, Mansfield JH, Hornstein E, Tabin CJ. The RNaseIII enzyme Dicer is required for morphogenesis but not patterning of the vertebrate limb. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(31):10898–10903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chong MM, Rasmussen JP, Rudensky AY, Littman DR. The RNAseIII enzyme Drosha is critical in T cells for preventing lethal inflammatory disease. J Exp Med. 2008;205(9):2005–2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wang Y, Medvid R, Melton C, Jaenisch R, Blelloch R. DGCR8 is essential for microRNA biogenesis and silencing of embryonic stem cell self-renewal. Nat Genet. 2007;39(3):380–385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. O'Carroll D, Mecklenbrauker I, Das PP, et al. A Slicer-independent role for Argonaute 2 in hematopoiesis and the microRNA pathway. Genes Dev. 2007;21(16):1999–2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bernstein E, Kim SY, Carmell MA, et al. Dicer is essential for mouse development. Nat Genet. 2003;35(3):215–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wienholds E, Koudijs MJ, van Eeden FJ, Cuppen E, Plasterk RH. The microRNA-producing enzyme Dicer1 is essential for zebrafish development. Nat Genet. 2003;35(3):217–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Selbach M, Schwanhausser B, Thierfelder N, Fang Z, Khanin R, Rajewsky N. Widespread changes in protein synthesis induced by microRNAs. Nature. 2008;455(7209):58–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lim LP, Lau NC, Garrett-Engele P, et al. Microarray analysis shows that some microRNAs downregulate large numbers of target mRNAs. Nature. 2005;433(7027):769–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Miranda KC, Huynh T, Tay Y, et al. A pattern-based method for the identification of MicroRNA binding sites and their corresponding heteroduplexes. Cell. 2006;126(6):1203–1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Poy MN, Eliasson L, Krutzfeldt J, et al. A pancreatic islet-specific microRNA regulates insulin secretion. Nature. 2004;432(7014):226–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dumortier O, Van Obberghen E. MicroRNAs in pancreas development. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2012;14(suppl 3):22–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Guay C, Jacovetti C, Nesca V, Motterle A, Tugay K, Regazzi R. Emerging roles of non-coding RNAs in pancreatic β-cell function and dysfunction. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2012;14(suppl 3):12–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lynn FC, Skewes-Cox P, Kosaka Y, McManus MT, Harfe BD, German MS. MicroRNA expression is required for pancreatic islet cell genesis in the mouse. Diabetes. 2007;56(12):2938–2945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gu G, Dubauskaite J, Melton DA. Direct evidence for the pancreatic lineage: NGN3+ cells are islet progenitors and are distinct from duct progenitors. Development. 2002;129(10):2447–2457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Morita S, Hara A, Kojima I, et al. Dicer is required for maintaining adult pancreas. PLoS One. 2009;4(1):e4212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dor Y, Brown J, Martinez OI, Melton DA. Adult pancreatic β-cells are formed by self-duplication rather than stem-cell differentiation. Nature. 2004;429(6987):41–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Melkman-Zehavi T, Oren R, Kredo-Russo S, et al. miRNAs control insulin content in pancreatic β-cells via downregulation of transcriptional repressors. EMBO J. 2011;30(5):835–845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kalis M, Bolmeson C, Esguerra JL, et al. β-Cell specific deletion of Dicer1 leads to defective insulin secretion and diabetes mellitus. PLoS One. 2011;6(12):e29166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mandelbaum AD, Melkman-Zehavi T, Oren R, et al. Dysregulation of Dicer1 in β cells impairs islet architecture and glucose metabolism. Exp Diabetes Res. 2012;2012:470302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kanji MS, Martin MG, Bhushan A. Dicer1 is required to repress neuronal fate during endocrine cell maturation. Diabetes. 2013;62(5):1602–1611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dueck A, Meister G. Assembly and function of small RNA-argonaute protein complexes. Biol Chem. 2014;395(6):611–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Meister G. Argonaute proteins: functional insights and emerging roles. Nat Rev Genet. 2013;14(7):447–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tattikota SG, Rathjen T, McAnulty SJ, et al. Argonaute2 mediates compensatory expansion of the pancreatic β cell. Cell Metab. 2014;19(1):122–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Tattikota SG, Sury MD, Rathjen T, et al. Argonaute2 regulates the pancreatic β-cell secretome. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2013;12(5):1214–1225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Correa-Medina M, Bravo-Egana V, Rosero S, et al. MicroRNA miR-7 is preferentially expressed in endocrine cells of the developing and adult human pancreas. Gene Expr Patterns. 2009;9(4):193–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Joglekar MV, Patil D, Joglekar VM, et al. The miR-30 family of microRNAs confer epithelial phenotype to human pancreatic cells. Islets. 2009;1(2):137–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bravo-Egana V, Rosero S, Molano RD, et al. Quantitative differential expression analysis reveals miR-7 as major islet microRNA. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;366(4):922–926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kredo-Russo S, Mandelbaum AD, Lennox KA, Behlke MA, et al. Pancreas-enriched miRNA refines endocrine cell differentiation. Development. 2012;139(16):3021–3031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Yasuda T, Kajimoto Y, Fujitani Y, et al. PAX6 mutation as a genetic factor common to aniridia and glucose intolerance. Diabetes. 2002;51(1):224–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wang Y, Liu J, Liu C, Naji A, Stoffers DA. MicroRNA-7 regulates the mTOR pathway and proliferation in adult pancreatic β-cells. Diabetes. 2013;62(3):887–895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Zoncu R, Efeyan A, Sabatini DM. mTOR: from growth signal integration to cancer, diabetes and ageing. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2011;12(1):21–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bernal-Mizrachi E, Wen W, Stahlhut S, Welling CM, Permutt MA. Islet β cell expression of constitutively active Akt1/PKBα induces striking hypertrophy, hyperplasia, and hyperinsulinemia. J Clin Invest. 2001;108(11):1631–1638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hamada S, Hara K, Hamada T, et al. Upregulation of the mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 pathway by Ras homolog enriched in brain in pancreatic β-cells leads to increased β-cell mass and prevention of hyperglycemia. Diabetes. 2009;58(6):1321–1332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Latreille M, Hausser J, Stutzer I, et al. MicroRNA-7a regulates pancreatic β cell function. J Clin Invest. 2014;124(6):2722–2735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Plaisance V, Abderrahmani A, Perret-Menoud V, Jacquemin P, Lemaigre F, Regazzi R. MicroRNA-9 controls the expression of Granuphilin/Slp4 and the secretory response of insulin-producing cells. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(37):26932–26942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Fukuda M. Rab27 and its effectors in secretory granule exocytosis: a novel docking machinery composed of a Rab27.effector complex. Biochem Soc Trans. 2006;34Pt 5:691–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Gomi H, Mizutani S, Kasai K, Itohara S, Izumi T. Granuphilin molecularly docks insulin granules to the fusion machinery. J Cell Biol. 2005;171(1):99–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. El Ouaamari A, Baroukh N, Martens GA, Lebrun P, Pipeleers D, van Obberghen E. miR-375 targets 3′-phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase-1 and regulates glucose-induced biological responses in pancreatic β-cells. Diabetes. 2008;57(10):2708–2717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ramachandran D, Roy U, Garg S, Ghosh S, Pathak S, Kolthur-Seetharam U. Sirt1 and mir-9 expression is regulated during glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in pancreatic β-islets. FEBS J. 2011;278(7):1167–1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Saunders LR, Sharma AD, Tawney J, et al. miRNAs regulate SIRT1 expression during mouse embryonic stem cell differentiation and in adult mouse tissues. Aging (Albany NY). 2010;2(7):415–431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Moynihan KA, Grimm AA, Plueger MM, et al. Increased dosage of mammalian Sir2 in pancreatic β cells enhances glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in mice. Cell Metab. 2005;2(2):105–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Joglekar MV, Parekh VS, Mehta S, Bhonde RR, Hardikar AA. MicroRNA profiling of developing and regenerating pancreas reveal post-transcriptional regulation of neurogenin 3. Dev Biol. 2007;311(2):603–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Lee CS, De Leon DD, Kaestner KH, Stoffers DA. Regeneration of pancreatic islets after partial pancreatectomy in mice does not involve the reactivation of neurogenin-3. Diabetes. 2006;55(2):269–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Gradwohl G, Dierich A, LeMeur M, Guillemot F. neurogenin3 is required for the development of the four endocrine cell lineages of the pancreas. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97(4):1607–1611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Roggli E, Britan A, Gattesco S, et al. Involvement of microRNAs in the cytotoxic effects exerted by proinflammatory cytokines on pancreatic β-cells. Diabetes. 2010;59(4):978–986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Bravo-Egana V, Rosero S, Klein D, et al. Inflammation-mediated regulation of MicroRNA expression in transplanted pancreatic islets. J Transplant. 2012;2012:723614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Eizirik DL, Colli ML, Ortis F. The role of inflammation in insulitis and β-cell loss in type 1 diabetes. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2009;5(4):219–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Regazzi R, Sadoul K, Meda P, Kelly RB, Halban PA, Wollheim CB. Mutational analysis of VAMP domains implicated in Ca2+-induced insulin exocytosis. EMBO J. 1996;15(24):6951–6959. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Wheeler MB, Sheu L, Ghai M, et al. Characterization of SNARE protein expression in β cell lines and pancreatic islets. Endocrinology. 1996;137(4):1340–1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Yaekura K, Julyan R, Wicksteed BL, et al. Insulin secretory deficiency and glucose intolerance in Rab3A null mice. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(11):9715–9721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Ruan Q, Wang T, Kameswaran V, et al. The microRNA-21-PDCD4 axis prevents type 1 diabetes by blocking pancreatic β cell death. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(29):12030–12035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Vinciguerra M, Sgroi A, Veyrat-Durebex C, Rubbia-Brandt L, Buhler LH, Foti M. Unsaturated fatty acids inhibit the expression of tumor suppressor phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) via microRNA-21 up-regulation in hepatocytes. Hepatology. 2009;49(4):1176–1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Frankel LB, Christoffersen NR, Jacobsen A, Lindow M, Krogh A, Lund AH. Programmed cell death 4 (PDCD4) is an important functional target of the microRNA miR-21 in breast cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(2):1026–1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Peyton M, Stellrecht CM, Naya FJ, Huang HP, Samora PJ, Tsai MJ. β3, a novel helix-loop-helix protein, can act as a negative regulator of β2 and MyoD-responsive genes. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16(2):626–633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Iguchi H, Ikeda Y, Okamura M, et al. SOX6 attenuates glucose-stimulated insulin secretion by repressing PDX1 transcriptional activity and is down-regulated in hyperinsulinemic obese mice. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(45):37669–37680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Zhu Y, You W, Wang H, et al. MicroRNA-24/MODY gene regulatory pathway mediates pancreatic β-cell dysfunction. Diabetes. 2013;62(9):3194–3206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Vijayaraghavan J, Maggi EC, Crabtree JS. miR-24 regulates menin in the endocrine pancreas. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2014;307(1):E84–E92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Karnik SK, Hughes CM, Gu X, et al. Menin regulates pancreatic islet growth by promoting histone methylation and expression of genes encoding p27Kip1 and p18INK4c. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(41):14659–14664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Crabtree JS, Scacheri PC, Ward JM, et al. A mouse model of multiple endocrine neoplasia, type 1, develops multiple endocrine tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98(3):1118–1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Crabtree JS, Scacheri PC, Ward JM, et al. Of mice and MEN1: Insulinomas in a conditional mouse knockout. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23(17):6075–6085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Karnik SK, Chen H, McLean GW, et al. Menin controls growth of pancreatic β-cells in pregnant mice and promotes gestational diabetes mellitus. Science. 2007;318(5851):806–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Pullen TJ, da Silva Xavier G, Kelsey G, Rutter GA. miR-29a and miR-29b contribute to pancreatic β-cell-specific silencing of monocarboxylate transporter 1 (Mct1). Mol Cell Biol. 2011;31(15):3182–3194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Bagge A, Clausen TR, Larsen S, et al. MicroRNA-29a is up-regulated in β-cells by glucose and decreases glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;426(2):266–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Ishihara H, Wang H, Drewes LR, Wollheim CB. Overexpression of monocarboxylate transporter and lactate dehydrogenase alters insulin secretory responses to pyruvate and lactate in β cells. J Clin Invest. 1999;104(11):1621–1629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Zhao C, Wilson MC, Schuit F, Halestrap AP, Rutter GA. Expression and distribution of lactate/monocarboxylate transporter isoforms in pancreatic islets and the exocrine pancreas. Diabetes. 2001;50(2):361–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Roggli E, Gattesco S, Caille D, et al. Changes in microRNA expression contribute to pancreatic β-cell dysfunction in prediabetic NOD mice. Diabetes. 2012;61(7):1742–1751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Baran-Gale J, Fannin EE, Kurtz CL, Sethupathy P. β Cell 5′-shifted isomiRs are candidate regulatory hubs in type 2 diabetes. PLoS One. 2013;8(9):e73240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. He A, Zhu L, Gupta N, Chang Y, Fang F. Overexpression of micro ribonucleic acid 29, highly up-regulated in diabetic rats, leads to insulin resistance in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Mol Endocrinol. 2007;21(11):2785–2794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Herrera BM, Lockstone HE, Taylor JM, et al. MicroRNA-125a is over-expressed in insulin target tissues in a spontaneous rat model of type 2 diabetes. BMC Med Genomics. 2009;2:54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Pandey AK, Verma G, Vig S, Srivastava S, Srivastava AK, Datta M. miR-29a levels are elevated in the db/db mice liver and its overexpression leads to attenuation of insulin action on PEPCK gene expression in HepG2 cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2011;332(1–2):125–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Kurtz CL, Peck BC, Fannin EE, et al. MicroRNA-29 fine-tunes the expression of key FOXA2-activated lipid metabolism genes and is dysregulated in animal models of insulin resistance and diabetes. Diabetes. 2014;63(9):3141–3148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Kong L, Zhu J, Han W, et al. Significance of serum microRNAs in pre-diabetes and newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes: a clinical study. Acta Diabetol. 2011;48(1):61–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Ozcan S. MiR-30 family and EMT in human fetal pancreatic islets. Islets. 2009;1(3):283–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Tang X, Muniappan L, Tang G, Ozcan S. Identification of glucose-regulated miRNAs from pancreatic β cells reveals a role for miR-30d in insulin transcription. RNA. 2009;15(2):287–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Zhao X, Mohan R, Ozcan S, Tang X. MicroRNA-30d induces insulin transcription factor MafA and insulin production by targeting mitogen-activated protein 4 kinase 4 (MAP4K4) in pancreatic β-cells. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(37):31155–31164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Liao X, Xue H, Wang YC, et al. Matched miRNA and mRNA signatures from an hESC-based in vitro model of pancreatic differentiation reveal novel regulatory interactions. J Cell Sci. 2013;126(Pt 17):3848–3861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Kim JW, You YH, Jung S, et al. miRNA-30a–5p-mediated silencing of Beta2/NeuroD expression is an important initial event of glucotoxicity-induced β cell dysfunction in rodent models. Diabetologia. 2013;56(4):847–855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Wijesekara N, Zhang LH, Kang MH, Abraham T, Bhattacharjee A, Warnock GL, Verchere CB, Hayden MR. miR-33a modulates ABCA1 expression, cholesterol accumulation, and insulin secretion in pancreatic islets. Diabetes. 2012;61(3):653–658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Kang MH, Zhang LH, Wijesekara N, et al. Regulation of ABCA1 protein expression and function in hepatic and pancreatic islet cells by miR-145. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2013;33(12):2724–2732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Brunham LR, Kruit JK, Pape TD, et al. β-Cell ABCA1 influences insulin secretion, glucose homeostasis and response to thiazolidinedione treatment. Nat Med. 2007;13(3):340–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Baroukh N, Ravier MA, Loder MK, et al. MicroRNA-124a regulates Foxa2 expression and intracellular signaling in pancreatic β-cell lines. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(27):19575–19588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Joglekar MV, Parekh VS, Hardikar AA. New pancreas from old: microregulators of pancreas regeneration. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2007;18(10):393–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Lovis P, Gattesco S, Regazzi R. Regulation of the expression of components of the exocytotic machinery of insulin-secreting cells by microRNAs. Biol Chem. 2008;389(3):305–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Jing G, Westwell-Roper C, Chen J, Xu G, Verchere CB, Shalev A. Thioredoxin-interacting protein promotes islet amyloid polypeptide expression through miR-124a and FoxA2. J Biol Chem. 2014;289(17):11807–11815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Klein D, Misawa R, Bravo-Egana V, et al. MicroRNA expression in α and β cells of human pancreatic islets. PLoS One. 2013;8(1):e55064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Gregory PA, Bert AG, Paterson EL, et al. The miR-200 family and miR-205 regulate epithelial to mesenchymal transition by targeting ZEB1 and SIP1. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10(5):593–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Poy MN, Spranger M, Stoffel M. microRNAs and the regulation of glucose and lipid metabolism. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2007;9(suppl 2):67–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Kloosterman WP, Lagendijk AK, Ketting RF, Moulton JD, Plasterk RH. Targeted inhibition of miRNA maturation with morpholinos reveals a role for miR-375 in pancreatic islet development. PLoS Biol. 2007;5(8):e203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Poy MN, Hausser J, Trajkovski M, et al. miR-375 maintains normal pancreatic α- and β-cell mass. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(14):5813–5818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Wei R, Yang J, Liu GQ, et al. Dynamic expression of microRNAs during the differentiation of human embryonic stem cells into insulin-producing cells. Gene. 2013;518(2):246–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Erener S, Mojibian M, Fox JK, Denroche HC, Kieffer TJ. Circulating miR-375 as a biomarker of β-cell death and diabetes in mice. Endocrinology. 2013;154(2):603–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. van Rooij E, Kauppinen S. Development of microRNA therapeutics is coming of age. EMBO Mol Med. 2014;6(7):851–864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]