Abstract

Background

Ceruloplasmin (Cp) is a copper-binding acute-phase protein that is increased in inflammatory states and deficient in Wilson’s disease. Recent studies demonstrate increased levels of Cp are associated with increased risk of developing heart failure. Our objective is to test the hypothesis that serum Cp provides incremental and independent prediction of survival in stable patients with heart failure.

Methods and Results

We measured serum Cp levels in 890 patients with stable heart failure undergoing elective cardiac evaluation that included coronary angiography. We examine the role of Cp levels in predicting survival over 5-years of follow-up. Mean Cp level was 26.6±6.9 mg/dL, and demonstrated relatively weak correlation with BNP (r=0.187, p<0.001). Increased Cp levels were associated with increased 5 year all-cause mortality (Q4 vs Q1 HR 1.9, 95%CI 1.4–2.8, p<0.001). When controlled for coronary disease traditional risk factors, creatinine clearance, dialysis, body mass index, medications, history of myocardial infarction, BNP, LVEF, heart rate, QRS duration, left bundle branch blockage and ICD, higher Cp remained an independent predictor of increased mortality (Q4 vs Q1 HR1.7, 95%CI 1.1 – 2.6, p<0.05). Model quality was improved with addition of Cp to aforementioned co-variables (NRI of 9.3%, p<0.001)

Conclusions

Ceruloplasmin is an independent predictor of all-cause mortality in patients with heart failure. Use of Cp may help to identify patients at heightened mortality risk.

Keywords: Heart failure, Ceruloplasmin, biomarkers, outcomes

INTRODUCTION

Ceruloplasmin (Cp) is a 151 kDa glycoprotein that is predominantly synthesized in the liver [1, 2]. Ceruloplasmin transports over 95% of the body’s copper, an essential cofactor for cytochromes and enzymes. Over the past decades, Cp became increasingly recognized as a multi-functional metalloprotein besides maintaining copper homeostasis. Furthermore, Cp can directly mobilize iron into the serum and provides the major molecular link between copper and iron metabolism [3]. However, recent studies have demonstrated that Cp may act as an oxidase to nitric oxide [4], and may adversely impact on endothelial function [5]. An emerging literature also supports an important role of Cp in the development of neurodegenerative diseases [6] and in atrial fibrillation [7], suggesting a potential pathogenic role of Cp.

The potential mechanistic link between Cp and cardiovascular disease has been debated [8], although the focus has been primarily on its contribution to the development of atherosclerosis and lipid oxidation rather than its protective capacity [2, 9]. High levels of Cp were observed to be an independent risk for CAD [10], and our group has further demonstrated that elevated Cp is an independent predictor of major adverse cardiovascular events [8]. Several recent reports have indicated that Cp levels are elevated in patients with heart failure (HF), both in acute and chronic states and regardless of etiology [11, 12]. Furthermore, serum Cp levels appeared to be inversely correlated with LV ejection fraction but directly correlated with symptom severity especially in the non-ischemic group [11]. Herein, the objective of this study is to examine the prognostic value of Cp in a large, well-characterized cohort of patients with a history of HF, particularly in its clinical utility in the context of standard cardio-renal biomarkers such as B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP).

METHODS

Study Population

The Cleveland Clinic GeneBank study is a large, prospective cohort study from 2001 to 2006 comprised of stable 9,880 subjects undergoing elective diagnostic cardiac catheterization procedure. All research subjects, 18 years old and above, gave written informed consent that has been approved by the Cleveland Clinic Institutional Review Board. 1,909 patients have a history of HF detected by three methods: a) Directly asking patient by research personnel regarding past medical problems, including self-reporting history of HF. b) reviewing medical records for confirmation, especially outpatient visit to cardiology department (all patients were seen by cardiologist at Cleveland Clinic before the left heart cath. c) ICD codes and adjudication by research personnel. This analysis included 890 subjects with a history of HF and without evidence of recent acute coronary syndrome (cardiac troponin I <0.03 ng/mL), and with plasma samples available for Cp measurements. An estimate of creatinine clearance was calculated using the Cockcroft-Gault equation. The presence of clinically-relevant coronary artery disease (CAD) was confirmed by luminal stenosis of at least 50% in any major coronary arteries. Adjudicated 5 year all-cause survival was ascertained for all subjects following enrollment by prospective patient contact as well as chart review and Social Security Death Index data ascertainment up to 2011.

Sample storing and Ceruloplasmin Assay

About 70 cc of fasting arterial blood was drawn for each patient on day of enrollment. Blood was spun and serum samples were placed in small 5 cc tubes. About 7–10 small tubes were stored at −80° C for each patient. Quantitative determination of Cp mass was performed using an immunoturbidimetric assay (Architect ci8200, Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park IL), as previously described [8]. All samples either had not previously thawed or only thawed once prior to the analysis, which is within the specifications of this FDA-approved assay as intended. This assay provides highly sensitive measurement of Cp levels with an intra-assay coefficient of variation of 3.7%, inter-assay precision of up to 4%, and a reference range of 20 to 60 mg/dL. Serum BNP levels were measured by an immunoassay on the same platform.

Statistical Analyses and patients grouping

The Student t test or Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous variable and Chi square test for categorical variables were used to examine the difference between assigned groups. We also studied Cp in combination with BNP. In this combination model, Receiver Operator Characteristic (ROC) curve analyses and five-fold cross validation were used to determine the optimal Cp cutoffs. For a given cutoff, we used a Cox model to estimate the risk 5-year mortality. The five-fold cross validation divides the data into five approximately equally-sized portions. A Cox model is trained on four parts of the data and then estimates the risk of 5-year mortality in the fifth part. This is repeated for each of the five parts. We calculated the area under the curve (AUC) with the estimated risk. The optimal cutoff is chosen to maximize AUC values. Patients were grouped based on BNP levels into those with low BNP (<100 pg/mL), borderline “gray-zone” BNP (100 – 400 pg/mL) and high BNP (>400 pg/mL), which had previously been reported to be associated with increased risk of mortality in HF patients [13]. Kaplan-Meier analysis and Cox proportional hazards regression was used for time-to-event analysis to determine hazard ratio and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) for 5-year survival. Levels of Cp were then adjusted for traditional coronary heart disease risk factors in a multivariable model, including age, gender, systolic blood pressure, BMI, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, smoking, diabetics mellitus, creatinine clearance, dialysis use and medications (ACE inhibitors, beta-blockers, statin, nitrate and aspirin). Analyses were repeated after adjusting for prior history of myocardial infarction (MI), logarithm-transformed BNP, LVEF, EKG data (heart rate, QRS duration and left bundle branch block) and presence of implantable cardioverter defibrillator. Net reclassification index for evaluating the improvement in prediction performance gained by adding Cp to all aforementioned risk factors was calculated according to the Pencina method [14]. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC) and R 2.15.1 (Vienna, Austria).

RESULTS

Study Population

Baseline characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 1. The mean and median serum Cp levels were 26.6 and 25.6 mg/dL, respectively (interquartile range 21.5–30.2 mg/dL). Patients with elevated Cp levels were more likely to be female and with a history of diabetes mellitus, but they were also less likely to have history of coronary artery disease or history of MI.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Total (n=890) | Quartile 1 (n=225) | Quartile 2 (n=222) | Quartile 3 (n=221) | Quartile 4 (n=222) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range (mg/dL) | < 21.5 | 21.5 – 25.6 | 25.6 – 30.1 | >30.1 | ||

| Age, in years (SD) | 66.6 (10) | 65.7 (10) | 67.1 (10) | 67.5 (10) | 66 (10) | .232 |

| Male, n(%) | 543 (61) | 194 (86) | 148 (67) | 116 (52) | 85 (38) | <0.001 |

| BMI, mean in kg/m2(SD) | 30 (7) | 29 (6) | 29 (6) | 30 (7) | 31 (8) | .107 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n(%) | 269 (30) | 40 (18) | 61 (28) | 74 (33) | 94 (43) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension, n(%) | 670 (76) | 175 (79) | 167 (76) | 161 (74) | 167 (77) | 0.572 |

| Hyperlipidemia, n(%) | 700 (81) | 194 (87) | 175 (80) | 165 (78) | 166 (77) | 0.041 |

| CAD, n(%) | 684 (77) | 190 (85) | 165 (74) | 167 (76) | 162 (75) | 0.022 |

| MI, n(%) | 493 (59) | 146 (69) | 117 (56) | 115 (56) | 115 (55) | 0.008 |

| CABG, n(%) | 384 (43) | 122 (54) | 91 (41) | 90 (41) | 81 (36) | 0.001 |

| Cigarette smoking, n(%) | 620 (70) | 163 (72) | 157 (71) | 155 (70) | 145 (65) | 0.381 |

| Baseline medications | ||||||

| ACE inhibitors, n(%) | 601 (68) | 167 (74) | 154 (69) | 144 (65) | 136 (61) | 0.024 |

| Beta-blocker, n(%) | 592 (67) | 168 (75) | 137 (62) | 151 (68) | 136 (61) | 0.007 |

| Statin, n(%) | 534 (60) | 152 (68) | 140 (63) | 123 (56) | 119 (54) | 0.008 |

| Aspirin, n(%) | 566 (64) | 154 (68) | 142 (64) | 135 (61) | 135 (61) | 0.303 |

| Nitrate, n(%) | 347 (39) | 97 (43) | 83 (37) | 90 (41) | 77 (35) | 0.278 |

| B-type natriuretic peptide, median in pg/mL(IQR) | 300 (114 – 678) | 233 (87–497) | 255 (102–563) | 371 (162–880) | 381 (151–930) | <0.001 |

| LVEF, median (IQR) | 35(25–50) | 40(30–50) | 35(25–50) | 35(25–55) | 38(25–50) | 0.904 |

| Creatinine clearance, median in ml/min/1.73m2(IQR) | 83 (60–110) | 88.1 (69.4 – 117.2) | 81.7 (57.2 – 113.1) | 78.4 (55.4 – 98.5) | 80 (54.7 – 111.2) | <0.001 |

| Dialysis use, n(%) | 19 (2) | 8 (4) | 6 (3) | 3 (1) | 2 (1) | 0.013 |

| EKG Data | ||||||

| Heart rate, b/min(IQR) | 71 (62–83) | 69 (57–81) | 72 (63–82) | 71 (63–81) | 75 (66–86) | <0.001 |

| QRS duration, ms (IQR) | 108 (94–138) | 108 (96–135) | 108(94–138) | 108 (94–142) | 106 (92–142) | 0.908 |

| LBBB, n(%) | 101 (12) | 23 (10) | 29 (13) | 25 (12) | 24 (11) | 0.794 |

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; IQR, interquartile range; BMI, body mass index; CAD, coronary artery disease; MI, myocardial infarction; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft surgery; ACE, angiotensin converting enzyme

Correlation with cardiac and inflammatory indices

There was no statistically significant correlation between Cp levels and LV ejection fraction (r=0.05, p =0.174). Also, there was no statistically significant association between Cp and extent of underlying CAD (number of vessels affected). However, there was a weak correlation between Cp and plasma BNP levels (r=0.187, p<0.001).

Association of serum ceruloplasmin levels with survival

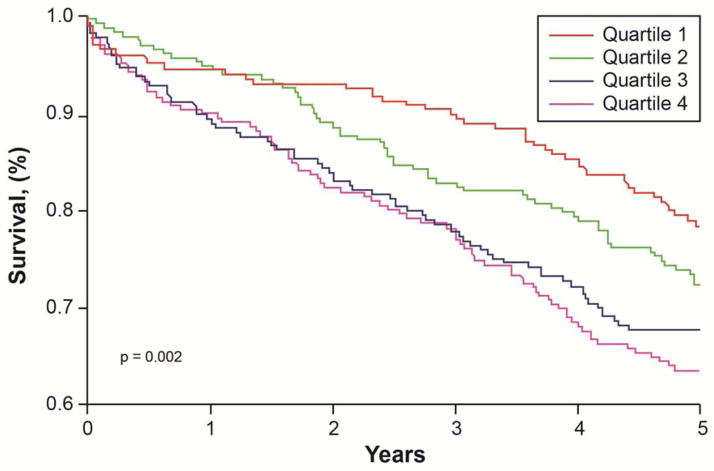

A number of 261 (29%) patients died at the 5 year follow up. The average time-to-event was 1,535 days. Table 2 illustrates the Cox proportional Hazard analysis of increased levels of Cp with 5-year all-cause mortality outcomes. In comparison to patients with the lowest Cp levels (quartile 1), patient with increased Cp levels had higher risk of 5-year all-cause mortality (quartile 4 vs quartile 1, unadjusted Hazard ratio [HR] 1.94, 95% confidence interval [95%CI] 1.36–2.77, p<0.001, Table 2 and Figure 1). After adjusting for coronary heart disease traditional risk factors, medications, creatinine clearance, dialysis use, BMI, history of MI, BNP and LVEF, higher Cp remained a significant predictor of increased 5 year mortality (adjusted HR 1.71, 95%CI 1.15 – 2.55, p<0.01). Analysis was also repeated after adjustment for heart rate, QRS duration, LBBB and ICD placement. In this model, Cp remained also an independent predictor of worse 5 year outcome (Table 2). We also stratified the analysis by previous history of MI (n=493). In both MI and no MI patients, Cp was associated with increased 5 year mortality, Q4 vs Q1 of 1.95(1.03–3.7), p=0.041 for no-MI group and 1.98 (1.3–3.1) p=0.003 for MI group.

Table 2.

Hazard ratio for 5 year mortality by Cp quartiles

| Serum Ceruloplasmin Level (range) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quartile 1 | Quartile 2 | Quartile 3 | Quartile 4 | |

| Range (mgldL) | <21.5 | 21.5–25.6 | 25.6–30.2 | >=30.2 |

| Unadjusted HR | 1 | 1.34 (0.92–1.95) | 1.71 (1.18– 2.46)** | 1.94 (1.36– 2.77)*** |

| Adjusted HR Model 1 | 1 | 1.19 (0.81–1.74) | 1.64(1.12–2.41)* | 1.93 (1.31– 2.85)*** |

| Adjusted HR Model 2 | 1 | 1.22 (0.83–1.78) | 1.62(1.11–2.37)* | 1.9 (1.29–2.81)*** |

| Adjusted HR Model 3 | 1 | 1.3 (0.87–1.94) | 1.55(1.04–2.3)* | 1.71 (1.15–2.55)** |

| Adjusted HR Model 4 | 1 | 1.36 (0.91–2.05) | 1.57(1.04–2.37)* | 1.68(1.11–2.53)* |

| Adjuster HR Model 5 | 1 | 1.34 (0.88–2.03) | 1.45 (0.95–2.22) | 1.68(1.1–2.55)* |

| Event rate | 47/221 | 61/223 | 72/223 | 81/223 |

Model 1: Adjusted for coronary heart disease traditional risk factors: age, Gender, systolic blood pressure, diabetes, high density lipoprotein, low density lipoprotein, body mass index, smoking, creatinine clearance and dialysis use; Model 2: Model 1 plus medications (ACEi, beta blockers, statins, nitrate and aspirin); Model 3: Model 2 plus MI, log transformed BNP and EF; Model 4: Model 3 plus ventricular rate, QRS duration and left bundle branch block; Model 5: Model 4 plus ICD.

p value <0.05;

p value <0.01;

p value <0.001

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier analysis of 5 year survival stratified according to ceruloplasmin quartiles.

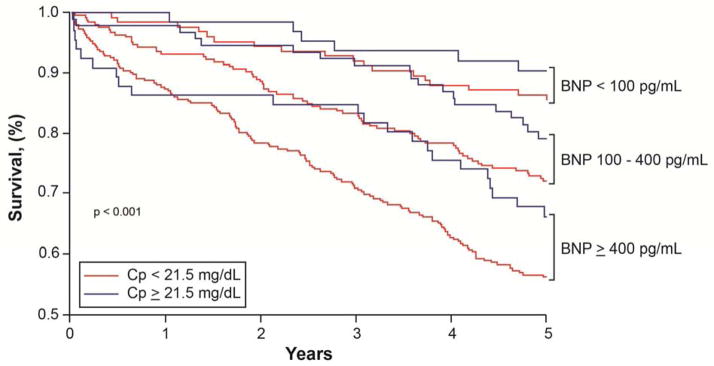

We further explore the prognostic value of Cp within specific BNP ranges. As illustrated in Figure 2, higher Cp levels are associated with poorer outcomes compared to lower Cp levels within each clinically-defined BNP range. The optimal cut-off was 21.5 mg/dL based on ROC curve analysis. Higher Cp levels showing increased risk of 5-year mortality within the borderline BNP range (unadjusted HR 3.2, 95% CI 1.40 – 7.5, p=0.006) as well as in the high BNP range (unadjusted HR 5.8, 95% CI 2.6 –13.1, p<0.001). After adjusting for aforementioned risk factors, higher Cp still showed increased mortality risk when within the borderline BNP range (adjusted HR 3, 95%CI 1.1–8.5, p=0.036) or the high BNP range (adjusted HR 4.3, 95%CI 1.5–11.9, p=0.006, Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier analysis of 5 year survival in patients with heart failure based on Cp and BNP levels.

Using Cp in patient with different BNP levels (low <100 pg/mL, borderline 100–400 pg/mL or high >400 pg/mL) can help in identifying heightened risk HF patients.

Association between Ceruloplasmin levels and liver congestion

Most of our patients had normal levels of liver enzymes: median (IQR) ALT of 20 (16–26) U/mL and AST of 18 (16–26) U/mL. Slight positive correlation was found between Cp and ALT (R2=0.004, p=0.048). However, no significant correlation was found between Cp and AST (R2=0.003, p=0.188). Defining hepatic congestion as having x2 upper normal range of liver enzymes [AST reference range of (7–40) U/L; ALT reference range (0–45) U/L], only 8 patients had hepatic congestion. Levels of Cp were not significantly different between groups (median of 25.9 mg/dL for hepatic congestion group vs 25.6 mg/dL for non-congestion group, p=0.99). Cp is one the synthetic function of the liver which would be expected to be low in setting of liver congestion suggesting our observation is independent of liver involvement by heart failure

Discrimination testing

Both net reclassification improvement (NRI) and Integrated Discrimination Improvement (IDI) were used to quantify improvement in model performance. P values compare models with/without Cp. Both models were adjusted for traditional coronary heart disease risk factors including: age, gender, systolic blood pressure, diabetes, high density lipoprotein, low density lipoprotein, BMI, smoking, creatinine clearance, dialysis use, MI, log transformed BNP, EF, heart rate, QRS duration, left bundle branch block and ICD placement. Cutoff values for NRI estimation used a ratio of 6:2:2 for low, medium and high risk categories. The risk of mortality was estimated using the Cox model. The net reclassification improvement of Cp for 5-year mortality was 9.33% (p<0.001). The relative integrated discrimination improvement for this model was 18% (p<0.001). This is responsible for 6.52 % and 2.81 for correctly reclassifying events and non-events respectively. The C-statistic of the model also improved from 0.687 to 0.701 with the addition of Cp but did not reach statistical significance (p=0.18).

DISCUSSION

Being one of the most abundant circulating glycoproteins with a widely available biochemical measurement of its concentration, clinicians have associated low (rather than high) levels of Cp with Wilson’s disease - a rare, recessive autosomal hepato-lenticular degeneration disease leading to pathological deposition of copper in the liver, nervous system, and kidneys. At the other end of the spectrum, Cp is often considered as an acute phase reactant that is elevated in the setting of acute inflammatory conditions and in pregnancy [1], and has been widely available in clinical practice. Our group and others have previously observed that Cp has been reported to be an independent risk factor for CAD [8, 10, 15–17] and higher levels of Cp was associated with adverse outcomes [8]. However, despite early reports of elevated Cp levels and its catalytic activities in the setting of acute MI in the 1950s [18], there have been limited investigations regarding the potential contribution of this relatively abundant circulating glycoprotein in the development and progression of myocardial dysfunction in humans. There are several key findings from our study. For the first time especially in a contemporary patient cohort, we observed that Cp provides prognostic value of 5-year mortality in patients with HF that was independent of coronary heart disease traditional risk factors, and the availability of Cp levels can reclassify risk for 5-year mortality by 9.33%. Second, the lack of strong relationship between Cp and measures of HF severity such as LV ejection fraction and BNP implies that Cp may provide distinct information of underlying pathophysiology. Taken together, using Cp (in combination with BNP) may help to identify patients at heightened long-term mortality risk. These findings, together with earlier reports suggesting the association between elevated Cp and increased likelihood of developing heart failure [19], imply that the mechanistic underpinnings of the pathophysiologic role of Cp in myocardial dysfunction warrant further investigations.

The connection between Cp expression and development of HF in humans are based primarily on epidemiologic data. Data from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study also confirmed the ability of Cp to predict future development of HF [19]. Only few studies about association between Cp and HF were done. Another study also found increased incidence of HF in patients with high Cp levels over 22 years of follow up [20]. Meanwhile, in patients who were admitted with ST-segment elevated MI, increased Cp levels was shown to be associated with increased incidence of acute HF and decreased LV ejection fraction [21].

Mechanism of Cardiac involvement in Wilson disease is still not very well understood; however, copper deposition is the likely mechanism causing myocardial inflammation and interstitial fibrosis. Interestingly, defect in Wilsons disease is related to impairment in hepatic copper transport protein, which impairs copper binding to apo-ceruloplasmin to form Cp, resulting in low levels of serum Cp [22]. Cp levels do not seem to be related to amount of copper deposition in the liver or other tissues, giving the fact that many Wilson patients who responded to medical treatment had persistently low levels of Cp levels. Furthermore, patients with aceruloplaminemia tend to have higher iron deposition in tissue rather than copper [23, 24].

The underlying mechanisms for increased in Cp expression in heart failure are not well understood, but the lack of tight association with standard cardiac indices may suggest an underlying metabolic defect at play. Over the past decades, Cp has been shown to have multiple roles in copper transportation, coagulation, angiogenesis, defense against oxidant stress, and iron homeostasis [2, 25]. In addition to transporting copper, Cp exhibits a copper-dependent ferroxidase activity, which is associated with possible oxidation of Fe2+ (ferrous iron) into Fe3+ (ferric iron), playing a possible fundamental mechanism of protection from iron-mediated free radical injury [4, 26], inhibit lipid oxidation [27, 28], block protein and DNA damage [2, 25, 29–32]. Despite these promising effects, most of these protective enzymatic activities have only been demonstrated in vitro, and thus warrants further demonstration in humans particularly in disease states such as HF. It is important to point out that although widely available and inexpensive to measure, clinically available assays including the one used in this study only represents the concentration of Cp mass in the circulation rather than its activity. Interestingly, diminished Cp ferroxidase activities were observed in substantia nigra tissues of Parkinson’s disease patients versus control [33], as well as in blood samples of pre-eclampsia patients versus controls [34] despite similar or increased Cp mass concentrations. This was also seen in a small HF group (n=96), where patients with low Cp ferroxidase activities were found to have worse disease severity and outcomes [26, 35]. Hence, there remains an intriguing possibility that the quality rather than the quantity of Cp may exert a stronger influence to the function of Cp, and the imbalance of pro- and anti-oxidant Cp enzymatic activities may link to heightened rather than diminished downstream nitrative stress.

In more advanced stages, HF promotes impaired tissue perfusion. It has been well established that the Cp gene exhibits multiple hypoxia-responsive elements, and up-regulation of Cp gene transcription was noticed during hypoxia [36, 37]. Activation of Cp expression is mechanistically linked to hypoxia-inducible factor, whereby hypoxia-response element-dependent gene regulation leads to transcriptional induction of the Cp gene promoter [37, 38]. Recently, Cp has also been shown to have NO oxidase activity in vivo, converting NO, potent short living vasodilator and anti-oxidant, to less active reservoir form, nitrite [39]. It’s possible that increased levels of Cp can decrease available plasma NO, thus enhancing reactive oxidant species formation and oxidative cell injury [4, 5, 39]. Interestingly, nitrite cad be reduced back to NO mainly during hypoxic situations [40]. Cp knockout animals have lower nitrite reservoir, and they were found to have more hepatocellular infarction after ischemia and reperfusion than wild-type animals. Nitrate supplementation seems to reduce the injury [4]. Therefore, increased heart failure mortality with increased Cp levels could be related to decrease NO availability in the plasma, or Cp levels increase being a result of relative tissue hypoxia giving close gene location to hypoxia-response element.

Study Limitations

Despite being the largest HF cohort reported with Cp levels and long-term outcomes, our study population represents a selected group of patients undergoing elective coronary angiogram (about 77% of our population has underlying CAD) with a relatively high proportion of patients with ischemic HF etiology. Despite finding significant association between Cp levels and all-cause mortality, we do not have complete data about cause of death, hospitalization, or consistent echocardiographic indices (like LV hypertrophy or diastolic indices). We also did not have direct measures of Cp function (such as ferroxidase or NO oxidase activities). Despite these limitations, our intriguing findings should prompt further investigations into how Cp contributes to the pathophysiology of heart failure.

CONCLUSION

Ceruloplasmin is an independent predictor of long-term all-cause mortality in patients with HF. Use of Cp in combination with BNP may help to identify patients at heightened mortality risk.

Table 3.

Reclassification table using Cp levels.

| Whole cohort (n=890) | |

|---|---|

| Events correctly reclassified | 6.52% |

| Non-events correctly reclassified | 2.81% |

| Net reclassification index (NRI) | 9.33% |

| Integrated discrimination improvement (IDI) | 18% |

Baseline model include: age, sex, systolic blood pressure, diabetes, high density lipoprotein, low density lipoprotein, body mass index, smoking, creatinine clearance, dialysis use, myocardial infarction, log transformed B-type natriuretic peptide, left ventricular ejection fraction, resting heart rate, QRS duration, left bundle branch block and implantable cardioverter defibrillator placement.

HIGHLIGHTS.

Relatively weak correlation between cerulopasmin (Cp) and natriuretic peptides in the setting of heart failure

Higher Cp levels was associated with increased risk of 5-year all-cause mortality.

Prognostic value of Cp independent of coronary heart disease risk factors and cardiac indices (natriuretic peptides, left ventricular ejection fraction, EKG indices)

Acknowledgments

FUNDING

This research was supported by grants R01HL103931, P01HL076491, and P01HL098055 from the National Institutes of Health. Clinical samples used in this study were from GeneBank, a study supported by National Institutes of Health grants R01HL103866, P20HL113452 (with the Office of Dietary Supplements), and the Cleveland Clinic Clinical Research Unit of the Case Western Reserve University CTSA (UL1TR 000439). SLH is also partially supported by a gift from the Leonard Krieger endowment and by the Foundation LeDucq.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE

Dr. Hazen is named as co-inventor on pending patents held by the Cleveland Clinic relating to cardiovascular diagnostics. Dr. Hazen reports having been paid as a consultant or speaker for the following companies: Cleveland Heart Lab, Esperion, Lilly, Liposcience Inc., Merck & Co., Inc., and Pfizer Inc. Dr. Hazen reports receiving research funds from Abbott, Cleveland Heart Lab, Liposcience Inc., Pfizer Inc, and Takeda Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Hazen reports having the right to receive royalty payments for inventions or discoveries related to cardiovascular diagnostics or therapeutics from the companies shown below: Abbott Laboratories, Inc., Cleveland Heart Lab., Esperion, Frantz Biomarkers, LLC, Liposcience Inc., and Siemens. All other authors have no relationships to disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hellman NE, Gitlin JD. Ceruloplasmin metabolism and function. Annu Rev Nutr. 2002;22:439–58. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.22.012502.114457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fox PL, Mazumder B, Ehrenwald E, Mukhopadhyay CK. Ceruloplasmin and cardiovascular disease. Free Radic Biol Med. 2000;28:1735–44. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00231-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cherukuri S, Potla R, Sarkar J, Nurko S, Harris ZL, Fox PL. Unexpected role of ceruloplasmin in intestinal iron absorption. Cell Metab. 2005;2:309–19. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2005.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shiva S, Wang X, Ringwood LA, Xu X, Yuditskaya S, Annavajjhala V, et al. Ceruloplasmin is a NO oxidase and nitrite synthase that determines endocrine NO homeostasis. Nat Chem Biol. 2006;2:486–93. doi: 10.1038/nchembio813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cappelli-Bigazzi M, Ambrosio G, Musci G, Battaglia C, Bonaccorsi di Patti MC, Golino P, et al. Ceruloplasmin impairs endothelium-dependent relaxation of rabbit aorta. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:H2843–9. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.273.6.H2843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Texel SJ, Xu X, Harris ZL. Ceruloplasmin in neurodegenerative diseases. Biochem Soc Trans. 2008;36:1277–81. doi: 10.1042/BST0361277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adamsson Eryd S, Sjogren M, Smith JG, Nilsson PM, Melander O, Hedblad B, et al. Ceruloplasmin and atrial fibrillation: evidence of causality from a population-based Mendelian randomization study. J Intern Med. 2014;275:164–71. doi: 10.1111/joim.12144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tang WH, Wu Y, Hartiala J, Fan Y, Stewart AF, Roberts R, et al. Clinical and genetic association of serum ceruloplasmin with cardiovascular risk. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2012;32:516–22. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.237040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giurgea N, Constantinescu MI, Stanciu R, Suciu S, Muresan A. Ceruloplasmin - acute-phase reactant or endogenous antioxidant? The case of cardiovascular disease. Med Sci Monit. 2005;11:RA48–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reunanen A, Knekt P, Aaran RK. Serum ceruloplasmin level and the risk of myocardial infarction and stroke. Am J Epidemiol. 1992;136:1082–90. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu Y, Lin H, Zhou Y, Cheng G, Xu G. Ceruloplasmin and the extent of heart failure in ischemic and nonischemic cardiomyopathy patients. Mediators Inflamm. 2013;2013:348145. doi: 10.1155/2013/348145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaya Z, Kaya B, Sezen H, Bilinc H, Asoglu R, Yildiz A, et al. Serum ceruloplasmin levels in acute decompensated heart failure. Clin Ter. 2013;164:e187–91. doi: 10.7417/CT.2013.1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maisel A. B-type natriuretic peptide levels: diagnostic and prognostic in congestive heart failure: what’s next? Circulation. 2002;105:2328–31. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000019121.91548.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pencina MJ, D’Agostino RB, Sr, D’Agostino RB, Jr, Vasan RS. Evaluating the added predictive ability of a new marker: from area under the ROC curve to reclassification and beyond. Stat Med. 2008;27:157–72. doi: 10.1002/sim.2929. discussion 207–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gocmen AY, Sahin E, Semiz E, Gumuslu S. Is elevated serum ceruloplasmin level associated with increased risk of coronary artery disease? Can J Cardiol. 2008;24:209–12. doi: 10.1016/s0828-282x(08)70586-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klipstein-Grobusch K, Grobbee DE, Koster JF, Lindemans J, Boeing H, Hofman A, et al. Serum caeruloplasmin as a coronary risk factor in the elderly: the Rotterdam Study. Br J Nutr. 1999;81:139–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim HJ, Yoo HS, Kim PK, Kim MR, Lee HW, Kim CW. Comparative analysis of serum proteomes of patients with cardiovascular disease. Clin Biochem. 2011;44:178–84. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2010.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adelstein SJ, Coombs TL, Vallee BL. Metalloenzymes and myocardial infarction. I. The relation between serum copper and ceruloplasmin and its catalytic activity. N Engl J Med. 1956;255:105–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM195607192550301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dadu RT, Dodge R, Nambi V, Virani SS, Hoogeveen RC, Smith NL, et al. Ceruloplasmin and heart failure in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study. Circ Heart Fail. 2013;6:936–43. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.113.000270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Engström G, Hedblad B, Tydé, et al. Inflammation-sensitive plasma proteins are associated with increased incidence of heart failure: A population-based cohort study. Atherosclerosis. 2009;202:617–22. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.05.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brunetti ND, Pellegrino PL, Correale M, Gennaro L, Cuculo A, Biase M. Acute phase proteins and systolic dysfunction in subjects with acute myocardial infarction. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2008;26:196–202. doi: 10.1007/s11239-007-0088-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kuan P. Cardiac Wilson’s disease. Chest. 1987;91:579–83. doi: 10.1378/chest.91.4.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harris ZL, Takahashi Y, Miyajima H, Serizawa M, MacGillivray RT, Gitlin JD. Aceruloplasminemia: molecular characterization of this disorder of iron metabolism. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1995;92:2539–43. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.7.2539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Azevedo EM, Scaff M, Barbosa ER, Neto AE, Canelas HM. Heart involvement in hepatolenticular degeneration. Acta neurologica Scandinavica. 1978;58:296–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1978.tb02890.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fox PL, Mukhopadhyay C, Ehrenwald E. Structure, oxidant activity, and cardiovascular mechanisms of human ceruloplasmin. Life Sci. 1995;56:1749–58. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(95)00146-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cabassi A, Binno SM, Tedeschi S, Ruzicka V, Dancelli S, Rocco R, et al. Low serum ferroxidase I activity is associated with mortality in heart failure and related to both peroxynitrite-induced cysteine oxidation and tyrosine nitration of ceruloplasmin. Circulation research. 2014;114:1723–32. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.302849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Al-Timimi DJ, Dormandy TL. The inhibition of lipid autoxidation by human caeruloplasmin. Biochem J. 1977;168:283–8. doi: 10.1042/bj1680283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yamashoji S, Kajimoto G. Antioxidant effect of caeruloplasmin on microsomal lipid peroxidation. FEBS Lett. 1983;152:168–70. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(83)80371-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goldstein IM, Kaplan HB, Edelson HS, Weissmann G. Ceruloplasmin: an acute phase reactant that scavenges oxygen-derived free radicals. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1982;389:368–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1982.tb22150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goldstein IM, Kaplan HB, Edelson HS, Weissmann G. Ceruloplasmin. A scavenger of superoxide anion radicals. J Biol Chem. 1979;254:4040–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paradis M, Gagne J, Mateescu MA, Paquin J. The effects of nitric oxide-oxidase and putative glutathione-peroxidase activities of ceruloplasmin on the viability of cardiomyocytes exposed to hydrogen peroxide. Free Radic Biol Med. 2010;49:2019–27. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chapman AL, Mocatta TJ, Shiva S, Seidel A, Chen B, Khalilova I, et al. Ceruloplasmin is an endogenous inhibitor of myeloperoxidase. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:6465–77. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.418970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ayton S, Lei P, Duce JA, Wong BX, Sedjahtera A, Adlard PA, et al. Ceruloplasmin dysfunction and therapeutic potential for parkinson disease. Ann Neurol. 2013;73:554–9. doi: 10.1002/ana.23817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shakour-Shahabi L, Abbasali-Zadeh S, Rashtchi-Zadeh N. Serum level and antioxidant activity of ceruloplasmin in preeclampsia. Pak J Biol Sci. 2010;13:621–7. doi: 10.3923/pjbs.2010.621.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cao DJ, Hill JA. Copper futures: ceruloplasmin and heart failure. Circulation research. 2014;114:1678–80. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.304091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Martin F, Linden T, Katschinski DM, Oehme F, Flamme I, Mukhopadhyay CK, et al. Copper-dependent activation of hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF)-1: implications for ceruloplasmin regulation. Blood. 2005;105:4613–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-10-3980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mukhopadhyay CK, Mazumder B, Fox PL. Role of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 in transcriptional activation of ceruloplasmin by iron deficiency. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:21048–54. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000636200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sarkar J, Seshadri V, Tripoulas NA, Ketterer ME, Fox PL. Role of ceruloplasmin in macrophage iron efflux during hypoxia. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:44018–24. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304926200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lundberg JO, Weitzberg E, Gladwin MT. The nitrate-nitrite-nitric oxide pathway in physiology and therapeutics. Nature reviews Drug discovery. 2008;7:156–67. doi: 10.1038/nrd2466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pinder A, Pittaway E, Morris K, James P. Nitrite directly vasodilates hypoxic vasculature via nitric oxide-dependent and -independent pathways. British Journal of Pharmacology. 2009;157:1523–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00340.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]