Abstract

AIM: Cysteine peptidase (CP) and its inhibitor (CPI) are a matrix protease that may be associated with colorectal carcinoma invasion and progression, and vitamin E is also a stimulator of the immunological system. Our purpose was to determine the correlation between the expression of cysteine peptidases and their endogenous inhibitors, and the level of vitamin E in sera of patients with colorectal cancer in comparison with healthy individuals.

METHODS: The levels of cysteine peptidases and their inhibitors were determined in the sera of patients with primary and metastatic colorectal carcinoma and healthy individuals using fluorogenic substrate, and the level of vitamin E was determined by HPLC.

RESULTS: The levels of cysteine peptidases and their inhibitors were significantly higher in the metastatic colorectal cancer patients than that in the healthy controls (P<0.05). The activity of CP increased 2.2-fold, CPI 2.8-fold and vitamin E decreased 3.4-fold in sera of patients with metastasis in comparison with controls. The level of vitamin E in healthy individuals was higher, whereas the activity of cysteine peptidases and their inhibitors associated with complexes was lower than that in patients with cancer of the digestive tract.

CONCLUSION: These results suggest that the serum levels of CP and their inhibitors could be an indicator of the prognosis for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Vitamin E can be administered prophylactically to prevent digestive tract neoplasmas.

Keywords: Cysteine peptidases, Inhibitors, Vitamin E, Colorectal cancers

INTRODUCTION

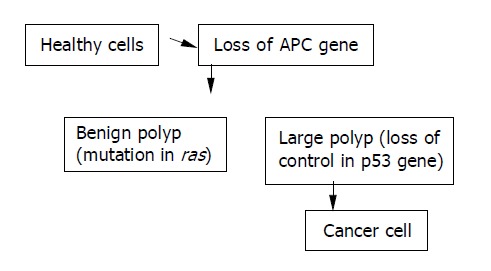

The first pathologic changes taking place in the organs of patients who presently are regarded as having neoplastic changes were recorded[1]. The results of diagnostic and statistical data have shown that in Poland, neoplastic diseases occurr in about 75000 people yearly and account for about 40% of these neoplastic changes in the digestive system. It is assumed that by the year 2010 the number of people with neoplastic changes will reach up to 80%[2]. It is also assumed that one of the basic causes of neoplastic changes is environmental pollution as a result of advances in industrialization[3]. Epidemiologic data were from the Centre of Oncology in Heidelberg, where examinations on the level of pollution in water, on land, and in the air by carcinogenic substances in Europe were carried out, and showed that the highest level of pollution caused by substances leading to cancer were observed in the region of Legnica and Głgow[4]. These results were supported by genetic test researches, showing that these substances could cause mutation of the digestive tract epithelial cells. It has also been shown that the mutated suppressor gene APC could take place in chromosome 5 (MCC - mutated in colorectal carcinoma), and the DCC gene (deleted in colorectal carcinoma) codes for proteins determining adhesion between mutated and unmutated cells. The information obtained from these examinations has made it possible to prepare a hypothetic scheme of neoplastic cell induction in the digestive tract (Figure 1)[5].

Figure 1.

Hypothetic scheme of neoplastic cell induction in digestive tract.

For the further development of cancer, an important role is played by proteolytic enzymes like elastase, collagenase, metalloproteinases, cysteine peptidase, cathepsins B and L as well as cathepsin D. The researches carried out by many research groups have confirmed the fact that enzymes taking part in the process of carcinogenesis can autoactivate enzymatic transformation cascade in which cysteine peptidase plays a key role[6,7]. At the same time, it has also been shown that the relationship between cathepsins and caspases which are responsible for necrosis and apoptosis in cells helps the development of cancer[8]. A rise in the activity of cysteine peptidase was observed in the sera of patients[9] and in cell cultures and cancer tissues of the digestive tract[10]. We assumed that they could be used as components in the new generation of drugs referred to as inhibitotherapy which could be used in cancer therapy as well as inhibiting the growth of pathogenic microorganisms[11,12].

It was found that vitamin E could inhibit cysteine endopeptidase activities by increasing endogen inhibitor level. The level of vitamin E in healthy individuals was higher than that in patients who were exposed to the action of toxic substances as well as in patients with cancer[13]. In cell cultures, vitamin E could inhibit the expression of oncogenes H-ras and c-myc in cells, which are the factors determining the initiation of neoplastic processes[14]. Sakamoto et al[15,16]. suggested that they could activate macrophages leading to the production of interleukin-1, which acts on fibroblasts, lymphocytes catalyzing the secretion of interleukin 6, which increases the level of kininogen T, an autogenic inhibitor of cysteine peptidase.

The level of cysteine peptidases and their inhibitors and the level of vitamin E in the sera of patients with different degrees of digestive tract cancer were determined as compared to analogous markers in healthy individuals.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

All patients whose sera were tested were inhabitants of Legnica and Glogow, which is the most polluted region of Poland by carcinogenic substances, who had been living in this region for at least five years and the exposure level to the action of carcinogenic substances was the same (this concerns both healthy individuals and those with neoplastic changes in the digestive tract).

We purposely did not choose the people performing jobs which made them at a higher risk of exposure to toxic and carcinogenic elements. The aim was to eliminate the effect of toxic substances present in the working environment especially when it was a threat to the health of workers.

Blood samples were collected from the cubital veins of healthy males and females as well as those with neoplastic changes in the group aged 35-70 years. We determined the active cysteine peptidases and their inhibitors in each serum sample and the amount (free, total amount produced in the organism) bound to the enzyme-inhibitor complex. After routine diagnostic tests were carried out, the patients taking part in the research were divided into 5 groups, 25 in each group, so that the results obtained could be tested statistically. Group A: healthy individuals without neoplastic changes, not genetically developing malignant cancer of the digestive tract; group B: patients with changes that did not show the qualities of malignancy (6 gastric adenomas, 13 colorectal adenomas, 5 ulcerative colitis, 1 patient with Crohn’s disease); group C: patients with cancer before operation and chemotherapy; group D: patients operated once after chemotherapy; group E: patients with non-operative cancer and metastases.

Cysteine peptidase activity (CP)

Sample probes of sera were filled up to 950 μL of 0.01 mol/L phosphate-buffered solution at pH 6.0 containing 2 nmol/L DL of cysteine and 2 nmol/L EDTA. Next, 50 μL 1.5 mmol/L of substrate benzoilo-arginylo β-naftylo amid (BANA) was added. The whole probe was incubated at 37 °C. After a 12-h reaction, a break was taken during which β-naftyloamine was released. As a unit of activity, we chose the amount of enzyme which hydrolyzed 1 nmoL β-naftyloamine[17] within an hour.

Cysteine peptidase inhibitor activity

Fifty microliters of 0.01% papain solution with activities of 3-4 units/mg protein was added to sera samples, and preincubated for 10 min at 37 °C, and then filled 950 μL 0.01 mol/L of phosphate buffered solution at pH of 6.0 containing 2 nmol/L DL cysteine and 2 nmol/L EDTA. Fifty microliters of 1.5 nmol/L of substrate solution was incubated at 37 °C, after 30 min the amount of released β- aftyloamine was determined. We assumed that a unit of inhibition was the amount of inhibitors in sera samples which inhibited one unit of papain[18].

Total amount of cysteine peptidase inhibitors in sera

Twenty to 200 μL sera samples each with the same amount of 0.02 mol/L HCl was preincubated for 20 min at 80 °C, cooled to room temperature and then filled up to 1.0 mL of 0.02 mol/L of phosphate-buffered solution at pH 6.0 containing 2 nmol/L DL cysteine and 2 nmol/L EDTA. One hundred microliters of each sample was collected and the inhibitory activity with respect to papain was determined as described in ICP37[18].

Cysteine peptidase inhibitors associated with complexes △ICP

The amount of inhibitors associated with enzyme-inhibitor complexes was calculated in each serum sample as a difference between the total amount of inhibitors and their active forms (△ICP = ICP80-ICP37).

Determination of vitamin E level

Vitamine E was determined in sera samples by liquid chromatographic methods using HPLC apparatus from Philips and a detector Pye Unicam PU 4020 UV using a computer program, the peak simple chromatography data system[19].

In all the samples tested, the enzymatic activity and the level of inhibitors and the amount of vitamin E were calculated and converted to 1.0 mL sera.

Statistical analysis

Statistical determination was carried out with the help of the programe Statgraf. Distribution analysis of results was done using Colmogorov-Smirnoffs test. The examined parameters possessed a normal distribution in which parametric tests were used. The results obtained were compared using Student’s t-test and Vilcox or Kruskal-Walis. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

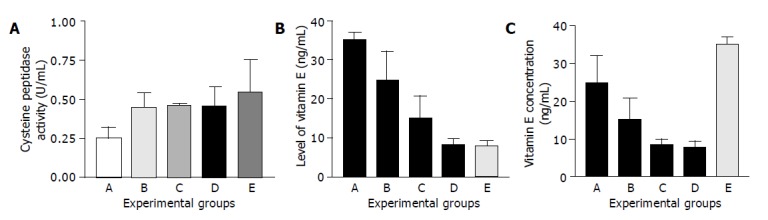

Figure 2A shows the activity of cysteine peptidases (cathepsins B and L) in sera of patients with different stages of colorectal cancer before and after chemotherapy and operation in comparison with control healthy blood. The mean activity of cysteine peptidases and their inhibitors was highly significant in comparison with controls (P<0.05). The activity increased 2.2-fold in sera of patients with metastasis in comparison with controls. The mean activity value of cysteine peptidases was 0.250±0.077 U/mL in group A, 0.448±0.092 U/mL in group B, 0.461±0.0100 U/mL in group C, 0.452±0.132 U/mL in group D, and 0.547±0.212 U/mL in group E. The mean value of inhibitor activity as a complex form (ΔCPI) in each group was as follows: 20.54±9.72 U/mL in group A, 32.92±11.17 U/mL in group B, 44.18±19.0 U/mL in group C, 27.64±8.23 U/mL in group D, and 58.22±20.12 U/mL in group E. The differences were statistically significant (Figure 2B). The activity increased 2.8-fold in patients with metastasis in comparison with control group. By examining the level of free inhibitors of cysteine peptidase as well as the total amount, we were unable to show any statistically significant difference in the examined groups A, B, C, D and E. Compared with the level of vitamin E in the sera of examined patients, the highest value of vitamin E was observed in healthy individuals. It was 35.0±0.03 ng/mL in group A, 24.71±7.41 ng/mL in group B, 15.08±5.67 ng/mL in group C, 8.42±1.54 ng/mL in group D, and 7.78±1.54 ng/mL in group E. The difference was statistically significant in comparison with controls (P<0.05) and the results are presented in Figure 2C.

Figure 2.

Changes in cysteine peptidases and their inhibitor activities and vitamin E concentration in patients with colorectal cancer in comparison with controls. A: Healthy individuals (control); B: Patients with primary neoplasms; C: Patients with cancer before operation and chemotherapy; D: Patients operated once after chemotherapy; E: Patients with non operative cancer and metastases (A) Cysteine peptidase activities (U/mL) (B) level of vitamin E (ng/mL) (C) vitamin E concentration (ng/mL).

DISCUSSION

In the research we wanted to find out if there was any relationship between active cysteine peptidases, their autogenic inhibitors and the level of vitamin E. An examination of all these parameters was carried out on the same samples obtained from patients with neoplasmas of the digestive tract and healthy individuals.

In the organs of healthy people, equilibrium was observed between active enzymes from the cysteine peptidases and their autogenic inhibitors. In determining the activity of the inhibitors, we used papain which in laboratory examinations was used in stead of other cysteine peptidases such as cathepsins B and L[20]. The activity of cysteine peptidases (cathepsins B and L) in sera of patients with different stages of colorectal cancer before and after chemotherapy and operation was compared with controls. The mean activity of cysteine peptidases and their inhibitors was highly significant in comparison with controls (P<0.05). The activity of CP increased 2.2-fold and CPI 2.8-fold in sera of patients with metastasis in comparison with controls. During the development process of neoplastic diseases, the activity of these enzymes increased, and other activated proteolytic enzymes like elastase, kolagenase causing catalytic degradation of healthy tissues initiated the development of a disease and their autogenic inhibitors were not able to stop the developing changes[21,22]. The aim of many researchers was to know the cause of a shift in equilibrium between enzyme-inhibitors. It is assumed that the answer to this question may help gain a better knowledge of accompanying neoplasmic changes. Information on this topic may support the conventional methods of treating malignant cancers[23,24]. Our research group dealt with the role of cysteine peptidases and their inhibitors in diagnosis and therapy of neoplastic changes[7,17,24,25]. The essence of information on enzymatic changes accompanying neoplastic processes was shown in the results obtained by a Japanese research group. They discovered that it was possible to increase the level of autogenic cysteine peptidase inhibitors after administration of large doses of vitamin E[15]. Our results showed that the level of vitamin E decreased 3.4-fold in patients with metastasis in comparison with healthy controls. Earlier researches showed that the level of vitamin E was lower in patients with cancer than in healthy people. This research was carried out in healthy individuals and patients with cancer[13]. Our research was based on this work and connected two independent research areas. The first was associated with the role of enzymatic processes and their inhibitors as well as vitamin E in neoplastic processes. Our research was limited to know the role of substances in initiating neoplasmas of the digestive tract in the inhabitants of Legnica and Głogow, which is the most polluted region of Poland by carcinogenic substances. In our research, we presented the assay results of the level of active enzymes determining the autogenic intensity of neoplastic processes, and the autogenic inhibitors controlling these changes and vitamin E, which may affect the enzyme-inhibitor equilibrium[26,27]. The present research was to give an answer to the questions like the relationship between the level of neoplasm and the activity of enzymes belonging to the cysteine peptidase group, their autogenic inhibitors and vitamin E. The results obtained confirmed that in healthy people the level of vitamin E was the highest and the activity of cysteine peptidases and their inhibitors had the least values. We therefore believe that this idea has a close relationship with the research by Sakamoto et al[15]. It is possible that vitamin E could induce an increase of the level of kininogen (an autogenic inhibitor of cysteine peptidase) in the organs, which play a key role in the transformation of neoplastic cells, invasion and metastases and in controlling the formation of apoptotic and necrotic changes in cells[28].

In conclusion, the level of vitamin E in healthy individuals is higher, whereas the activity of cysteine peptidases and their inhibitors associated with complexes is lower than that in patients with cancer of the digestive tract. Vitamin E can be prophylactically administered to prevent digestive tract neoplasmas.

Footnotes

Assistant Editor Li WZ Edited by Wang XL

References

- 1.Strauli P. Strauli P, Barrett AJ, Baici A. eds. Proteinase and tumor invasion. wdy. Raven Press, New York. 1980. A concept of tumor invasion; pp. 157–170. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zatoński W, Tuczyński J.red. Institute of Oncology, Institute M. Skłodowskie Curie, Warsaw, Poland. 1993. Progression of cancer in Poland in 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zatoński W, Tyczyński J. Institute of Oncology, Institute M. Sk³odowskie Curie, Warsaw, Poland. 1993. Progression expect death in cancer in Poland to 2010r. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hohensee E. IIARC scientific publications No134, Lyon. 1995. Map of the cancer atlas “Atlas of cancer mortality in Central Europe. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fearon ER, Vogelstein B. A genetic model for colorectal tumorigenesis. Cell. 1990;61:759–767. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90186-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harbeck N, Alt U, Berger U, Krüger A, Thomssen C, Jänicke F, Höfler H, Kates RE, Schmitt M. Prognostic impact of proteolytic factors (urokinase-type plasminogen activator, plasminogen activator inhibitor 1, and cathepsins B, D, and L) in primary breast cancer reflects effects of adjuvant systemic therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:2757–2764. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berdowska I, Siewiński M, Zarzycki-Reich A, Jarmułowicz J, Noga L. Activity of cysteine protease inhibitors in human brain tumors. Med Sci Monit. 2001;7:675–679. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schotte P, Van Criekinge W, Van de Craen M, Van Loo G, Desmedt M, Grooten J, Cornelissen M, De Ridder L, Vandekerckhove J, Fiers W, et al. Cathepsin B-mediated activation of the proinflammatory caspase-11. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;251:379–387. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adenis A, Huet G, Zerimech F, Hecquet B, Balduyck M, Peyrat JP. Cathepsin B, L, and D activities in colorectal carcinomas: relationship with clinico-pathological parameters. Cancer Lett. 1995;96:267–275. doi: 10.1016/0304-3835(95)03930-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Herszényi L, Farinati F, Plebani M, Carraro P, Roveroni G, De Paoli M, Cardin R, Naccarato R, Tulassay Z. Prognostic role of cisteine and serin proteases in gastric cancer. Orv Hetil. 1996;137:1637–1641. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Siewiński M. Autologous cysteine peptidase inhibitors as potential anticancer drugs. Anticancer Drugs. 1993;4:97–98. doi: 10.1097/00001813-199302000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hugli TE. Protease inhibitors: novel therapeutic application and development. Trends Biotechnol. 1996;14:409–412. doi: 10.1016/0167-7799(96)30020-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Longnecker MP, Martin-Moreno JM, Knekt P, Nomura AM, Schober SE, Stähelin HB, Wald NJ, Gey KF, Willett WC. Serum alpha-tocopherol concentration in relation to subsequent colorectal cancer: pooled data from five cohorts. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1992;84:430–435. doi: 10.1093/jnci/84.6.430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prasad KN, Cohrs RJ, Sharma OK. Decreased expressions of c-myc and H-ras oncogenes in vitamin E succinate induced morphologically differentiated murine B-16 melanoma cells in culture. Biochem Cell Biol. 1990;68:1250–1255. doi: 10.1139/o90-185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sakamoto W, Yoshikawa K, Shindoh M, Amemiya A, Handa H, Saeki T, Nagasawa S, Koyama J, Ogihara T, Mino M. In vivo effects of vitamin E on peritoneal macrophages and T-kininogen level in rats. Int J Vitam Nutr Res. 1989;59:131–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cascinu S, Ligi M, Del Ferro E, Foglietti G, Cioccolini P, Staccioli MP, Carnevali A, Luigi Rocchi MB, Alessandroni P, Giordani P, et al. Effects of calcium and vitamin supplementation on colon cell proliferation in colorectal cancer. Cancer Invest. 2000;18:411–416. doi: 10.3109/07357900009032811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krecicki T, Siewiński M. Serum cathepsin B-like activity as a potential marker of laryngeal carcinoma. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 1992;249:293–295. doi: 10.1007/BF00714496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Siewiński M, Gutowicz J, Kielan W, Bolanowski M. Cysteine peptidase inhibitors and activator(s) in urine of patients with colorectal cancer. Oncology. 1994;51:446–449. doi: 10.1159/000227381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nilsson B, Johansson B, Jansson L, Holmberg L. Determination of plasma alpha-tocopherol by high-performance liquid chromatography. J Chromatogr. 1978;145:169–172. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(00)81683-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kos J, Werle B, Lah T, Brunner N. Cysteine proteinases and their inhibitors in extracellular fluids: markers for diagnosis and prognosis in cancer. Int J Biol Markers. 2000;15:84–89. doi: 10.1177/172460080001500116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Storer AC, Ménard R. Catalytic mechanism in papain family of cysteine peptidases. Methods Enzymol. 1994;244:486–500. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(94)44035-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kos J, Lah TT. Cysteine proteinases and their endogenous inhibitors: target proteins for prognosis, diagnosis and therapy in cancer (review) Oncol Rep. 1998;5:1349–1361. doi: 10.3892/or.5.6.1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lah TT, Kos J. Cysteine proteinases in cancer progression and their clinical relevance for prognosis. Biol Chem. 1998;379:125–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Troy AM, Sheahan K, Mulcahy HE, Duffy MJ, Hyland JM, O'Donoghue DP. Expression of Cathepsin B and L antigen and activity is associated with early colorectal cancer progression. Eur J Cancer. 2004;40:1610–1616. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2004.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Iacobuzio-Donahue C, Shuja S, Cai J, Peng P, Willett J, Murnane MJ. Cathepsin D protein levels in colorectal tumors: divergent expression patterns suggest complex regulation and function. Int J Oncol. 2004;24:473–485. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leonetti C, Biroccio A, Gabellini C, Scarsella M, Maresca V, Flori E, Bove L, Pace A, Stoppacciaro A, Zupi G, et al. Alpha-tocopherol protects against cisplatin-induced toxicity without interfering with antitumor efficacy. Int J Cancer. 2003;104:243–250. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yam D, Peled A, Shinitzky M. Suppression of tumor growth and metastasis by dietary fish oil combined with vitamins E and C and cisplatin. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2001;47:34–40. doi: 10.1007/s002800000205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saleh Y, Siewiñski M, Sebzda T, Grybos M, Pawelec M, Janocha A. Effects of combined in vivo treatment of transplantable solid mammary carcinoma in wistar rats using vitamin E and cysteine peptidase inhibitors from human placenta. J Exp Ther Oncol. 2003;3:95–102. doi: 10.1046/j.1359-4117.2003.01077.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]