Abstract

AIM: To investigate whether vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) was over-expressed in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) or in surrounding cirrhotic liver tissues.

METHODS: Immunohistochemistry was performed to investigate the expression of VEGF proteins in HCC tissues from 105 consecutive patients undergoing curative resection for HCC. The immunostaining results and related clinicopathologic materials were analyzed with statistical methods. Kaplan–Meier method was used to calculate survival curves, and Log-rank test was performed to compare differences in survival rates of the patients with positive HCC staining and negative VEGF.

RESULTS: VEGF-positive expression was found in 72 of 105 HCC patients (68.6%). Capsular infiltration (P = 0.005), vascular invasion (P = 0.035) and intrahepatic metastasis (P = 0.008) were observed more frequently in patients with VEGF-positive expression than in those with VEGF-negative expression. Kaplan–Meier curves showed that VEGF-positive expression was associated with a shorter overall survival (P = 0.014). VEGF-positive expression was found in 47 of tissues 68 HCC (69.1%), and VEGF-positive expression was found in 54 of 68 surrounding cirrhotic liver tissues (79.4%). VEGF-positive expression was significantly higher in surrounding cirrhotic liver tissues than in HCC (P = 0.017).

CONCLUSION: VEGF may play an important role in the angiogenesis and prognosis of HCC, as well as in the angiogenesis of liver cirrhosis.

Keywords: Angiogenesis, Vascular endothelial growth factor, Hepatocellular carcinoma, Surrounding cirrhotic liver tissues

INTRODUCTION

Angiogenesis is a fundamental process involved in normal organ physiology, development and tissue repair, as well as, in a variety of pathological processes[1]. When blood vessels grow, angiogenesis becomes pathologic and sustains the progression of many neoplastic and non-neoplastic diseases[2]. VEGF is a potent mitogen specific for vascular endothelial cells and may directly stimulate the growth of new blood vessels[3]. VEGF has been reported to play an important role in the angiogenesis of HCC[4,5]. Studies have demonstrated that increasing expression of VEGF is correlated with aggressive behaviors and a poor prognosis of various human cancers including breast, gastric, esophageal and colorectal cancer[6-9]. Recent, evidence indicates that angiogenesis also plays an important role in the development of liver fibrosis[10]. It has been shown that VEGF expression significantly increases during the course of liver fibrosis in experimental studies and VEGF participates in sinusoidal capillarization in the liver[11]. It is reported that expression of VEGF in HCC is correlated with cirrhotic liver[12]. In this study, VEGF expressions in HCC and surrounding cirrhotic liver tissues were examined by immunohistochemical method.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

One hundred and five patients (79 males and 26 females, mean age 63±9 years, range 16-83 years) with singular nodule of HCC who had undergone curative hepatectomy from January 1993 to December 1997 at the Hepato-Biliary-Pancreatic Surgery Division, Graduate School of Medicine, University of Tokyo, Japan, were included in the study. Patients, who had previously a hepatectomy or hepatic arterial chemoembolization (TACE), were excluded. HCC tissues were obtained from all patients. HCC tissues and surrounding cirrhotic liver tissues were examined for VEGF. We also investigated the VEGF expression in normal liver tissue, that was surgically obtained from seven patients with metastatic liver tumors derived from colon cancer, which were not associated with HCC, chronic viral hepatitis and autoimmune hepatitis. The patients were strictly followed up. The mean period of follow-up was 38.7 mo (38.7±18.1, range 2-75 mo).

The pathologic diagnosis and classification of variables were based on the criteria recommended in the General Rules for Clinical and Pathological Study of Primary Liver Cancer (Liver Cancer Study Group of Japan 1992). Clinicopathological parameters analyzed included sex, age, liver pathology (hepatitis vs cirrhosis), tumor size (<5 cm vs ≥ 5 cm), tumor differentiation (high, moderate, poor), capsule formation (presence vs absence), capsule infiltration (presence vs absence), vascular invasion (including vascular invasion and/or tumor thrombi in portal or hepatic vein), and intrahepatic metastasis (presence vs absence) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Relationship between VEGF expression and clinicopathological Features of HCC (n=105).

| Variables | Number of patients |

VEGF expression |

P | |

| Positive (n = 72) | Negative (n = 33) | |||

| Sex | NS | |||

| Male | 79 | 54 | 25 | |

| Female | 26 | 18 | 8 | 0.003 |

| Age (yr) | NS | |||

| ≤60 | 51 | 42 | 9 | |

| >60 | 54 | 30 | 24 | |

| Liver pathology | ||||

| Cirrhosis | 68 | 47 | 21 | |

| Hepatitis | 37 | 25 | 12 | |

| Tumor size | NS | |||

| <5 | 71 | 47 | 24 | |

| ≥5 | 34 | 25 | 9 | |

| Tumor differentiation | NS | |||

| High | 27 | 18 | 9 | |

| Moderate | 65 | 45 | 20 | |

| Poor | 13 | 9 | 4 | |

| Capsule formation | NS | |||

| Presence | 31 | 20 | 11 | |

| Absence | 74 | 52 | 22 | |

| Capsule infiltration | 0.005 | |||

| Presence | 65 | 51 | 14 | |

| Absence | 40 | 21 | 19 | |

| Vascular invasion | 0.035 | |||

| Presence | 34 | 28 | 6 | |

| Absence | 71 | 44 | 27 | |

| Intrahepatic metastasis | 0.008 | |||

| Presence | 23 | 21 | 2 | |

| Absence | 82 | 51 | 31 | |

NS: no significant difference.

Immunohistochemistry

To obtain more accurate VEGF staining, we selected the tissue blocks containing HCC and surrounding liver tissues that were exposed to the same period of hypoxia. Five-micrometer thick sections were cut from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue blocks, deparaffinized and rehydrated in ethanol. The sections were incubated in 0.3% hydrogen peroxide in methanol for 30 min and in normal horse serum for 30 min at room temperature, followed by incubation overnight at 4 °C with anti-VEGF polyclonal antibody (A-20, sc-152G; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) diluted at 1:100. Bound anti-body was detected by the avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex method, using a commercial kit as recommended by the manufacturer (Vestastain ABC Elite kit; Vector, Burlingame, CA). 3,3’-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride was used as the chromogen and hematoxylin was used as a counterstain[13]. For negative control, 1.5% normal horse serum was used.

Evaluation of VEGF immunohistochemical staining

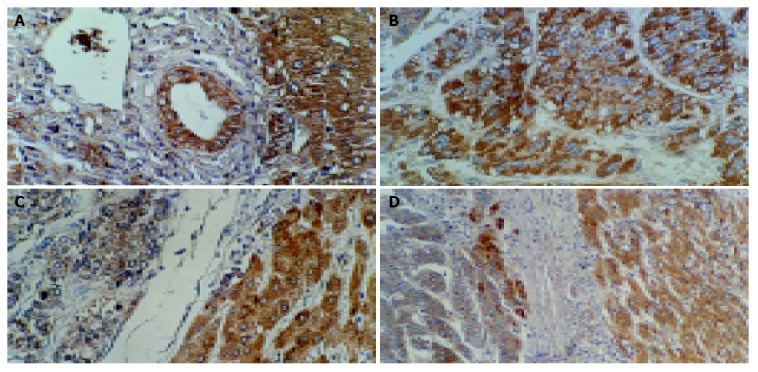

Positive staining for VEGF was located in cell cytoplasm. The percentage of cells stained positively for VEGF was evaluated by assessing 10 high-power microscopic fields (×400) in each section. In seven normal liver tissue specimens, the percentage of positively stained hepatocytes ranged from 90% to 100% (98.57±3.78) (Figure 1A). The expressions were graded as follows: negative if <60% of cancerous cells in a given specimen were positively stained; positive if ≥60% of cancerous cells in a given specimen were positively stained; negative if <96% of surrounding cirrhotic liver cells in a given specimen were positively stained; positive if ≥96% of surrounding cirrhotic liver cells in a given specimen were positively stained.

Figure 1.

Positive expression of VEGF in normal epithelial and hepatic cells (A) (ABC, ×200), and in hepatocellular carcinoma cells (B) (ABC, ×200), negative expression of VEGF in hepatocellular carcinoma cells and positive expression of VEGF in surrounding cirrhotic liver cells (C, D) (ABC, ×200, ×100).

Statistical analysis

Quantitative data were expressed as mean±SD. Chi-square test was used for comparison between groups. Kaplan-Meier method was used to calculate survival curves, and Log-rank test was performed to compare differences in survival rates of the patient groups. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Expression of VEGF in HCC tissue

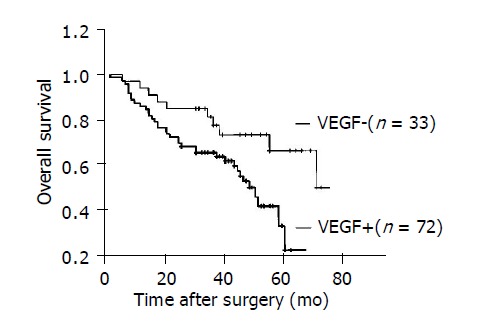

The percentage of positively- stained HCC ranged 0-90% (58.67±25.51) (Figure 1B). VEGF-positive expression was found in 72 of 105 HCC patients (68.6%). Capsular infiltration (P = 0.005), vascular invasion (P = 0.035) and intrahepatic metastasis (P = 0.008) were observed more frequently in patients with VEGF-positive expression than in those with VEGF-negative expression (Table 1). Kaplan-Meier curves showed that VEGF-positive expression was associated with a shorter overall survival (P = 0.014) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier curves for overall survival in 105 patients with HCC after operation (P = 0.014).

Expression of VEGF in HCC tissue and surrounding cirrhotic liver tissue

In the 68 patients with HCC accompanied with liver cirrhosis, the percentage of positive staining in surrounding cirrhotic liver tissues ranged 50-100% (95.59±1.46). VEGF-positive expression was found in 47 of 68 HCC tissues (69.1%) and in 54 of 68 surrounding cirrhotic liver tissues (79.4%) (Figures 1C, D). VEGF-positive expression was significantly higher in surrounding cirrhotic liver tissues than in HCC tissues (P = 0.017) (Table 2).

Table 2.

VEGF expression in HCC and surrounding cirrhotic liver tissues (n=68).

|

VEGF expression |

P | ||

| Positive n (%) | Negative n (%) | ||

| HCC | 47 (69.1) | 21 (30.9) | |

| Surrounding Cirrhotic liver | 54 (79.4) | 14 (20.6) | 0.017 |

DISCUSSION

VEGF is a potential tumor angiogenesis factor. In 1993, Kim et al[14] demonstrated that blocking the action of a paracrine mediator VEGF, that acts on the vasculature, may have a significant or even dramatic inhibitory effect on tumor growth and emphasized the significance of VEGF as an important mediator of tumor angiogenesis. Our study demonstrated that VEGF expression in 105 HCC patients had a significant correlation with capsular infiltration, vascular invasion, and intrahepatic metastasis. Furthermore, in our follow-up data, Kaplan-Meier curves showed that positive VEGF expressions in HCC correlated with shortened survival rates. These results suggest that VEGF may play an important role in angiogenesis and prognosis of HCC.

Strong evidence supports the hypothesis that VEGF is a key mediator of angiogenesis associated with various disorders[15]. Oxygen tension is a key regulator of VEGF gene expression both in vitro and in vivo[16]. VEGF as a hypoxia-inducible angiogenic factor has been extensively described in recent years[17, 18]. In 1998, El-Assal et al[12] showed that VEGF expression is significantly higher in cirrhotic liver tissues than in noncirrhotic liver tissues. In 1999, Shimoda et al[19] found a higher VEGF expression in cirrhosis but not in HCC. In 2000, Feng et al[20] reported that the positive rate of VEGF in HCC is significantly lower than in surrounding cirrhotic liver tissues (66.7% vs 85.4%). In this study, VEGF-positive expression was found in 47 of 68 HCC tissues (69.1%) and in 54 of 68 surrounding cirrhotic liver tissues (79.4%). Our data provides evidence that VEGF-positive expression is significantly higher in surrounding cirrhotic liver tissues than in HCC. It is possible that hepatocytes, in cirrhotic liver, are in a sustained mechanically-reduced blood flow, and the decreased oxygen pressure strongly up-regulates VEGF transcription and protein synthesis in the cirrhotic liver[12]. The excessive VEGF produced and secreted by hepatocytes and HCC cells may subsequently act on endothelial cells, resulting in growth of new blood vessels and capillarization of sinusoidal endothelial cells[21]. In addition, VEGF-positive expression is higher in HCC marginal areas than in HCC central areas[22]. Tumor cells expressing VEGF may have a growth advantage and proliferate more rapidly than cells that do not express VEGF. Rapid cell proliferation in the center of a tumor can lead to increased interstitial fluid pressure, which may result in compression closure of capillaries and consecutive tissue necrosis[23]. Central necrosis areas cause a suppression of VEGF protein synthesis[24]. Moreover, VEGF expression in surrounding cirrhotic liver tissues is also modulated by inflammatory cytokines released from infiltrating inflammatory cells. Several cytokines, such as basic fibroblast growth factor, transforming growth factor α and β, epidermal growth factor and platelet-derived growth factor have been reported to act cooperatively on VEGF expression[25-31]. These results suggest that VEGF also plays an important role in the development of liver cirrhosis.

In conclusion, VEGF-positive expression in HCC has a significant correlation with capsular infiltration, vascular invasion, and intrahepatic metastasis. VEGF may play an important role in the angiogenesis and prognosis of HCC, as well as in the angiogenesis of liver cirrhosis.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors are grateful to Dr Ai-Min Hui, Dr Ya-Zhou Shi and Dr Xin Li for their valuable assistance.

Footnotes

Supported by the China Scholarship Council, No. 98915009

Co-first-authors: Can-Hao Jin

Co-correspondents: Rong Mu

References

- 1.Folkman J, Shing Y. Angiogenesis. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:10931–10934. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Folkman J. Seminars in Medicine of the Beth Israel Hospital, Boston. Clinical applications of research on angiogenesis. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1757–1763. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199512283332608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leung DW, Cachianes G, Kuang WJ, Goeddel DV, Ferrara N. Vascular endothelial growth factor is a secreted angiogenic mitogen. Science. 1989;246:1306–1309. doi: 10.1126/science.2479986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mise M, Arii S, Higashituji H, Furutani M, Niwano M, Harada T, Ishigami S, Toda Y, Nakayama H, Fukumoto M, et al. Clinical significance of vascular endothelial growth factor and basic fibroblast growth factor gene expression in liver tumor. Hepatology. 1996;23:455–464. doi: 10.1053/jhep.1996.v23.pm0008617424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Park YN, Kim YB, Yang KM, Park C. Increased expression of vascular endothelial growth factor and angiogenesis in the early stage of multistep hepatocarcinogenesis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2000;124:1061–1065. doi: 10.5858/2000-124-1061-IEOVEG. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Linderholm BK, Lindh B, Beckman L, Erlanson M, Edin K, Travelin B, Bergh J, Grankvist K, Henriksson R. Prognostic correlation of basic fibroblast growth factor and vascular endothelial growth factor in 1307 primary breast cancers. Clin Breast Cancer. 2003;4:340–347. doi: 10.3816/cbc.2003.n.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maeda K, Kang SM, Ogawa M, Onoda N, Sawada T, Nakata B, Kato Y, Chung YS, Sowa M. Combined analysis of vascular endothelial growth factor and platelet-derived endothelial cell growth factor expression in gastric carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 1997;74:545–550. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19971021)74:5<545::aid-ijc12>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Inoue K, Ozeki Y, Suganuma T, Sugiura Y, Tanaka S. Vascular endothelial growth factor expression in primary esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Association with angiogenesis and tumor progression. Cancer. 1997;79:206–213. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19970115)79:2<206::aid-cncr2>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ishigami SI, Arii S, Furutani M, Niwano M, Harada T, Mizumoto M, Mori A, Onodera H, Imamura M. Predictive value of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in metastasis and prognosis of human colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 1998;78:1379–1384. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1998.688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yoshiji H, Kuriyama S, Yoshii J, Ikenaka Y, Noguchi R, Hicklin DJ, Wu Y, Yanase K, Namisaki T, Yamazaki M, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor and receptor interaction is a prerequisite for murine hepatic fibrogenesis. Gut. 2003;52:1347–1354. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.9.1347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Corpechot C, Barbu V, Wendum D, Kinnman N, Rey C, Poupon R, Housset C, Rosmorduc O. Hypoxia-induced VEGF and collagen I expressions are associated with angiogenesis and fibrogenesis in experimental cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2002;35:1010–1021. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.32524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.El-Assal ON, Yamanoi A, Soda Y, Yamaguchi M, Igarashi M, Yamamoto A, Nabika T, Nagasue N. Clinical significance of microvessel density and vascular endothelial growth factor expression in hepatocellular carcinoma and surrounding liver: possible involvement of vascular endothelial growth factor in the angiogenesis of cirrhotic liver. Hepatology. 1998;27:1554–1562. doi: 10.1002/hep.510270613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hui AM, Li X, Makuuchi M, Takayama T, Kubota K. Over-expression and lack of retinoblastoma protein are associated with tumor progression and metastasis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 1999;84:604–608. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19991222)84:6<604::aid-ijc11>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim KJ, Li B, Winer J, Armanini M, Gillett N, Phillips HS, Ferrara N. Inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor-induced angiogenesis suppresses tumour growth in vivo. Nature. 1993;362:841–844. doi: 10.1038/362841a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yancopoulos GD, Davis S, Gale NW, Rudge JS, Wiegand SJ, Holash J. Vascular-specific growth factors and blood vessel formation. Nature. 2000;407:242–248. doi: 10.1038/35025215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ferrara N. Molecular and biological properties of vascular endothelial growth factor. J Mol Med (Berl) 1999;77:527–543. doi: 10.1007/s001099900019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim KR, Moon HE, Kim KW. Hypoxia-induced angiogenesis in human hepatocellular carcinoma. J Mol Med (Berl) 2002;80:703–714. doi: 10.1007/s00109-002-0380-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cejudo-Martín P, Morales-Ruiz M, Ros J, Navasa M, Fernández-Varo G, Fuster J, Rivera F, Arroyo V, Rodés J, Jiménez W. Hypoxia is an inducer of vasodilator agents in peritoneal macrophages of cirrhotic patients. Hepatology. 2002;36:1172–1179. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.36371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shimoda K, Mori M, Shibuta K, Banner BF, Barnard GF. Vascular endothelial growth factor/vascular permeability factor mRNA expression in patients with chronic hepatitis C and hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Oncol. 1999;14:353–359. doi: 10.3892/ijo.14.2.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Feng DY, Shen M, Zheng H, Cheng RX. Relationship between vascular endothelial growth factor expression and microvessel density in hepatocellular carcinomas and their surrounding liver tissue. Hunan YiKe DaXue XueBao. 2000;25:132–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jeng KS, Sheen IS, Wang YC, Gu SL, Chu CM, Shih SC, Wang PC, Chang WH, Wang HY. Prognostic significance of preoperative circulating vascular endothelial growth factor messenger RNA expression in resectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a prospective study. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:643–648. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v10.i5.643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.An FQ, Matsuda M, Fujii H, Matsumoto Y. Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor in surgical specimens of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2000;126:153–160. doi: 10.1007/s004320050025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Plate KH, Breier G, Weich HA, Risau W. Vascular endothelial growth factor is a potential tumour angiogenesis factor in human gliomas in vivo. Nature. 1992;359:845–848. doi: 10.1038/359845a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lang KJ, Kappel A, Goodall GJ. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha mRNA contains an internal ribosome entry site that allows efficient translation during normoxia and hypoxia. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:1792–1801. doi: 10.1091/mbc.02-02-0017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yamaguchi R, Yano H, Iemura A, Ogasawara S, Haramaki M, Kojiro M. Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 1998;28:68–77. doi: 10.1002/hep.510280111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Steinbrech DS, Longaker MT, Mehrara BJ, Saadeh PB, Chin GS, Gerrets RP, Chau DC, Rowe NM, Gittes GK. Fibroblast response to hypoxia: the relationship between angiogenesis and matrix regulation. J Surg Res. 1999;84:127–133. doi: 10.1006/jsre.1999.5627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pepper MS, Ferrara N, Orci L, Montesano R. Potent synergism between vascular endothelial growth factor and basic fibroblast growth factor in the induction of angiogenesis in vitro. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1992;189:824–831. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(92)92277-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Finkenzeller G, Marmé D, Weich HA, Hug H. Platelet-derived growth factor-induced transcription of the vascular endothelial growth factor gene is mediated by protein kinase C. Cancer Res. 1992;52:4821–4823. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pertovaara L, Kaipainen A, Mustonen T, Orpana A, Ferrara N, Saksela O, Alitalo K. Vascular endothelial growth factor is induced in response to transforming growth factor-beta in fibroblastic and epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:6271–6274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pepper MS. Manipulating angiogenesis. From basic science to the bedside. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1997;17:605–619. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.17.4.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mandriota SJ, Pepper MS. Vascular endothelial growth factor-induced in vitro angiogenesis and plasminogen activator expression are dependent on endogenous basic fibroblast growth factor. J Cell Sci. 1997;110(Pt 18):2293–2302. doi: 10.1242/jcs.110.18.2293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]