Abstract

The success of potent antiretroviral treatment (ART) for HIV infection is primarily determined by the level of medication adherence. We systematically review the evidence on effectiveness of interventions to enhance ART adherence in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), where four fifths of the more than five million people receiving ART live. We identified 26 relevant publications reporting on 25 studies, conducted between 2003 and 2010, of behavioural, cognitive, biological, structural, and combination interventions. The majority (16) of the studies took place in hospital outpatient facilities in urban settings. Studies differed widely in design, sample size, length of follow-up, and outcome measurement. Despite study diversity and limitations, the evidence to date suggest that treatment supporters, directly observed therapy, cell phone short message services, diary cards and food rations and can be effective in increasing adherence in some settings in SSA. However, our synthesis of studies also shows that some interventions are unlikely to produce large or lasting effects, while other interventions are effective in some but not in other settings, emphasizing the need for more research, in particular, RCTs, to allow examination of the influence of context and particular features of intervention content on effectiveness. Important avenues for future work include intervention targeting and selection of interventions based on behavioural theories relevant to SSA.

Introduction

Antiretroviral treatment (ART) can significantly reduce morbidity and mortality in HIV-infected people.1-6 However, the clinical effectiveness of ART depends crucially on treatment adherence.7-10 Early studies indicated that maximal treatment effectiveness can only be achieved, if patients take at least 95% of their prescribed antiretroviral doses.7, 11, 12 Several more recent studies suggest that treatment with certain potent types of ART regimens, such as those based on ritonavir-boosted proteinase inhibitor and nonnucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitor therapy, can achieve viral suppression at lower levels of adherence,13-15 and that the adherence level required to prevent viral rebound decreases with duration of viral suppression.15 However, despite these findings it is still true that only sustained high levels of adherence will ensure that both the life-prolonging benefits of ART are maximized and the risk of developing a resistant viral strain is minimized.16 Imperfect adherence is the most common cause of failure to achieve or sustain potential treatment benefits.17 Moreover, poor adherence has been shown to increase health care costs considerably in both developing and developed countries.18, 19 Additionally, adherence is essential for the reduction of HIV transmission through ART in “test and treat” approaches.20

In recent years, many national governments in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), with support from international agencies and donors, have taken on the task of providing ART to all people in need.21 At the end of 2009, almost four fifths of the more than five million people receiving ART worldwide were living in SSA.22 ART adherence in the region may be low.23 A 2006 meta-analysis of ART adherence studies found that on average 23% of patients in studies from SSA did not achieve “adequate levels of adherence”.24 This average masks substantial heterogeneity in the proportion of non-adherent patients in SSA, which ranged from 2% to 70% across studies included in the meta-analysis,25 indicating a need to substantially improve adherence in some settings in the region. Moreover, many treatment programmes in SSA have only been operating for a few years. Experience from developed countries has shown that adherence levels tend to fall with time on ART,26-28 and early reports from SSA suggest similar adherence trends with treatment time.29 It thus seems likely that average ART adherence levels in SSA will decline in the future, as treatment programmes mature.

While there is thus a clear need for effective interventions to increase ART adherence in SSA, studies of ART adherence interventions have been primarily conducted in developed countries; many of which have been previously reviewed.25, 30-39 Table 1 provides an overview of categories of adherence interventions that have been used in research throughout the developed world.30, 31, 40 Evidence on adherence interventions from developed countries, however, may have limited relevance for SSA because the effectiveness of interventions is likely to depend crucially on the context in which they are implemented. The sub-Saharan contexts share many distinct characteristics. For instance, adherence interventions in developed countries are usually provided by nurses, pharmacists, or physicians,30, 34 while in ART programmes in SSA an HIV care-specific health worker cadre is commonly responsible for monitoring and supporting patients in their ART adherence, with minimal involvement from physicians.41 Further, interventions in developed countries may be based on theories of behaviour that are not valid in SSA, and interventions that have been specifically tailored to the needs for adherence support of specific subpopulations (such as men who have sex with men42 or injection drug users30) are likely to be of limited relevance in countries with generalized HIV epidemics. Resource-intensive interventions directed toward the individual43 may be challenging to implement in SSA given the large volumes of patients, limited resources, and public health approach to treatment.

Table 1.

Categories of interventions to improve ART adherence

| Category | Definition | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Behavioural | Affecting ART adherence through direct behaviour modification | • Reminder devices (e.g., seven-day pill boxes, alarms, cell phone short message services (SMS) or pager messages) • Cues for remembering dose times • Cash incentives for pill taking • Directly observed therapy (DOT) |

| Cognitive | Affecting ART adherence through teaching, clarification, or instruction | • Media education materials (e.g., audio, video, or reading materials) • Group education • Individual patient education |

| Affective | Affecting ART adherence through emotional support | • Peer support • Optimistic future writing • Counselling |

| Biological | Affecting ART adherence through improved physical ability to take ART | • Food ration provided with ART • Vitamin or micronutrient supplements |

| Structural | Affecting ART adherence through changes in the ART delivery structure or through additional service structures | • Delivering ART in community centres • Income-generating activities for ART patients • Community mobilization |

| Combination | Using a combination of one or more of the above intervention categories | • Individual patient information, behavioural adherence strategies, and peer support |

ART = antiretroviral treatment

Evidence from SSA is thus important to inform the design and implementation of ART adherence interventions in the region. To date no review of such evidence has been published; previous reviews have focussed on studies in the developed world.30-37 We report findings from the first systematic review of studies investigating the effectiveness of ART adherence interventions in SSA.

Methods

Eligibility criteria

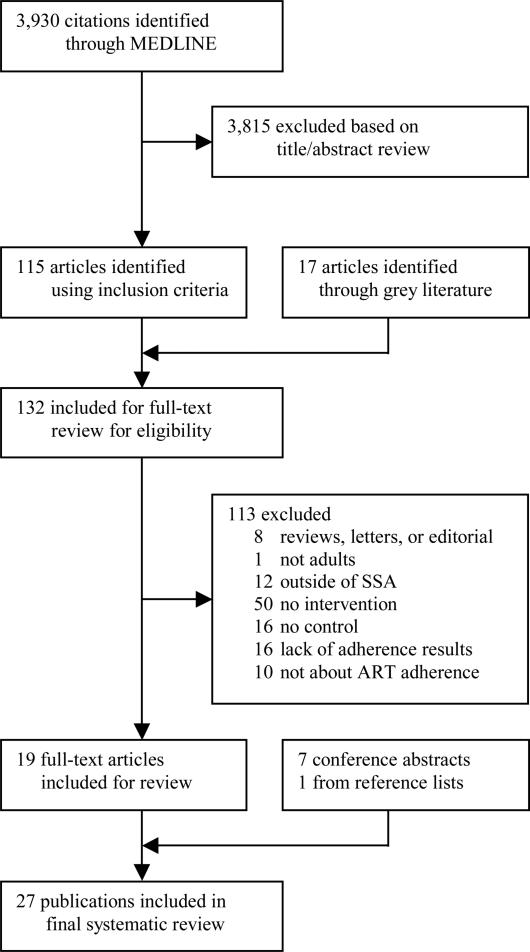

We included studies evaluating effectiveness of interventions to improve ART adherence in adults in SSA. Studies could report adherence as the primary or secondary outcome or simply report adherence measurements in the presence of an intervention. For the purposes of this review, we restricted the definition of adherence to medication adherence, i.e., the extent to which a patient takes a medication in the way intended by the healthcare provider. We did not review studies investigating the related but distinct concepts of adherence to ART appointments44 or retention within ART programmes.45, 46 We did not exclude studies based on the type of measurement used to assess ART adherence, but restricted our review to studies with a control or comparison group (i.e., a group that did not receive the intervention). We did not apply any other study design exclusion criteria, i.e., randomized controlled trials (RCTs), prospective and retrospective cohort studies, and before-after studies were acceptable study designs. On-going trials without an interim analysis were excluded from the final selection. We did not apply any language exclusion criteria. Only study results from SSA were included. For multi-site studies, data from the SSA sites were included, unless the SSA data could not be separately extracted from the study.47 Figure 1 shows the sequence we followed in applying our exclusion criteria. Studies were excluded, firstly, if they were reviews, letters to the editor, editorials, commentaries, or opinion articles, and then if they did not study populations in SSA, did not include adults (i.e., individuals 18 years of age or older), did not report an intervention, did not contain a control group, or did not report adherence results.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the systematic review

Search strategies

We carried out a systematic literature search of PubMed via MEDLINE for studies evaluating interventions to improve adherence to ART in SSA published before 31 January 2011. To identify articles for review, we combined two broad search themes using the Boolean operator “and”. The first search theme – ART – combined the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)48 “Antiretroviral Therapy, Highly Active” and “Anti-HIV Agents”, and the free text word “Antiretroviral”, using the Boolean operator “or”. The second theme – adherence – combined the MeSH term “Patient Compliance” with the free text word “Adherence”, using “or”. The MeSH terms were used in their exploded versions, that is, in addition to the selected MeSH term, all narrower terms that are categorized below it in the MeSH hierarchy were included in the PubMed search:48

((“Antiretroviral Therapy, Highly Active”[Mesh] OR “Anti-HIV Agents”[Mesh] OR antiretroviral) AND (“Patient Compliance”[Mesh] OR adherence))

In addition, we searched the reference lists of all publications included in the final review and all articles excluded from the review because they were review articles, editorials, or commentaries. We further searched the following conference databases using the conference websites: the Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI) (up to San Francisco, USA, in February 2010),49 the International AIDS Society (IAS) (up to Cape Town, South Africa, in July 2009),50 the International Conference on HIV Treatment Adherence (up to Miami, USA, in May 2010),51 and the mHealth Summit (up to Washington DC, USA, in November 2010).52 Furthermore, relevant publications in the grey literature (i.e., literature not controlled by commercial publishers53) were searched, including research reports, working papers and dissertations.54 To conduct this “grey literature” search, the terms “antiretroviral”, “therapy”, “adherence”, and “intervention” were typed into Google®'s internet search engine. Our review conformed to the PRISMA checklist for systematic reviews.55

Study selection and data extraction

Three investigators (KC, NC, and AP) worked independently, screening all abstracts from MEDLINE that suggested a study evaluating the effectiveness of interventions aimed at increasing ART adherence in adults in SSA. The same reviewers used the inclusion and exclusion criteria to independently assess the full eligibility of studies identified by MEDLINE, as well as conference abstracts, grey literature, and non-peer reviewed articles indentified via Google. Reviewers were not blinded to study authors, conclusions, or outcomes, because blinding has been shown to have little effect on systematic reviews.56 Once all potentially relevant full-text articles and abstracts were identified, three of the authors achieved consensus regarding eligibility (TB, KC, and NC) and extracted data, using a standardized extraction form.

All measures of adherence were recorded, including subjective and objectives adherence measures and biological correlates of adherence (such as CD4 count and viral load). Data from each of the studies was extracted and entered into an electronic database separately by two of three authors (KC, NC, and TB). When the two data entries did not match, consensus was reached through data checks and discussion between the data extractors, and, if necessary, consultation with one author (JH), who was not involved in the data extraction.

Assessment of risk of bias

We followed the PRISMA guidelines in assessing the risk of bias in individual studies and across studies.55 In particular, as recommended in the guidelines we assessed risk of bias separately for different components rather than in an overall scale. For the evaluation of individual RCT, we used the Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in the evaluation of individual RCTs, which proposes checks for selection bias (random generation of sequences for trial allocation and concealment of allocation before and during trial enrolment), performance bias (blinding of participants and personnel), detection bias (blinding of outcome assessment), attrition bias (completeness of data for each reported outcome), and reporting bias (completeness of reporting of assessed outcomes),57 For the evaluation of individual observational studies, we followed the GRADE recommendations.58 In addition, we compared reporting bias across studies and assessed the risk of publication bias.57

Results

We identified a total 3955 records (3930 in PubMed, 17 in an internet search of grey literature, and 8 in conference databases and reference lists) (Figure 1). Twenty-seven publications met all inclusion and exclusion criteria (17 journal articles,59-75 seven conference abstracts,76-81 one master's thesis,82 one research report,83 and one research letter84). Five publications were from Nigeria, 60, 69, 76, 78, 79 five from South Africa,74, 81-83, 85 four from Kenya,70, 73, 80, 86 three from Mozambique,63, 65, 66 three from Uganda,71, 77, 84 two from Malawi,61, 62 two from Zambia,59, 67 one from Rwanda,75 one from Tanzania,68 and one from several countries in SSA.72 All full-text articles and abstracts were published in English. A research letter84 and a conference abstract77 were from the same study in Uganda, therefore data from both sources were combined to create one study extraction. We extracted information separately – despite overlap in authors, study setting, and enrolled patients – if the studies differed in sample size,61, 62, 71, 74, 76, 77, 79, 84, 85 primary aims,61, 62 length of follow-up,61, 62, 71, 77, 84 intervention type,74, 85 or adherence measures.71, 74, 76, 77, 79, 84, 85 For example, two of the full-text articles were from the same study setting in Malawi, but the first study reported an initial three-month follow-up analysis of the overall results of an RCT,62 while the second reported a subsequent subgroup analysis with nine months of follow-up.61 As a result, information from 26 studies is reported in Tables 2 and 3.

Table 2.

Summary table of characteristics of interventions on ART adherence in sub-Saharan Africa

| First author and publication year | Source type | Intervention category | Intervention type | Study period | Study country (city or region) | Health care setting |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Busari et al. 200979 | Conference abstract | Cognitive and affective | Structured teaching programme vs. informal patient education | Not published | Nigeria (Abuja) |

Intervention: Hospital-inpatient (urban) Effect observation: Hospital-outpatient and community-based (urban) |

| Busari et al. 201076 | Conference abstract | Cognitive and affective | Structured teaching programme vs. informal patient education | Not published | Nigeria (Abuja) |

Intervention: Hospital-inpatient (urban) Effect observation: Hospital-outpatient and community-based (urban) |

| Cantrell et al. 200859 | Journal article | Biological | Food ration | 2004 | Zambia (Lusaka) | Community-based (urban) |

| Chang et al. 2008a,84 Chang et al. 2008b77 | Conference abstract and research letter | Behavioural, cognitive and affective | Treatment supporter | 2006-2008 | Uganda (Rakai) | Community-based (rural) |

| Chang et al. 201071 | Journal article | Behavioural, cognitive and affective | Treatment supporter | 2006-2008 | Uganda (Rakai) | Community-based (rural) |

| Chung et al. 200988 | Conference abstract | Behavioural and cognitive | Educational counselling vs. alarm device vs. combination vs. neither | 2006-2008 | Kenya (Nairobi) | Hospital-outpatient (urban) |

| Idoko et al. 200760 | Journal article | Behavioural | DOT (DAOT, TWOT, and WOT) | 2003 | Nigeria (Jos) | Hospital-outpatient (urban) |

| Kabore et al. 201072 | Journal article | Behavioural, cognitive, affective, biological and structural | Treatment supporter, nutritional support, financial support, psychosocial support, and educational counselling | 2005-2007 | Lesotho (Maseru), South Africa (Ladysmith), Namibia (Katima-Mulilo), and Botswana (Bobonong) | Community-based (unknown) |

| Lester et al. 201073 | Journal article | Behavioural | Mobile phone SMS | 2007-2008 | Kenya (Nairobi) | Community-based (urban and rural) |

| Mugusi et al. 200968 | Journal article | Behavioural, cognitive and affective | Treatment supporter, calendar with reminders, and educational counselling | 2004-2007 | Tanzania (Dar es Salaam) | Hospital-outpatient (urban) |

| Nachega et al. 200985 | Conference abstract | Behavioural | DOT (DAOT) | 2005-2007 | South Africa (Cape Town) | Hospital-outpatient (urban) |

| Nachega et al. 201074 | Journal article | Behavioural and cognitive | DOT (DAOT), educational counselling | 2005-2007 | South Africa (Cape Town) | Hospital-outpatient (urban) |

| Ndekha M et al. 2009a61 | Journal article | Biological | Lipid paste vs. flour supplement | 2006-2007 | Malawi (Blantyre) | Hospital-outpatient (urban) |

| Ndekha M et al. 2009b62 | Journal article | Biological | Lipid paste vs. flour supplement | 2006-2007 | Malawi (Blantyre) | Hospital-outpatient (urban) |

| Pearson et al. 200763 | Journal article | Behavioural, cognitive, and affective | Treatment supporters, with DOT (DOAT) and education | 2004 | Mozambique (Beira) | Hospital-outpatient (urban) |

| Pienaar et al. 200683 | Research report | Structural | Differing models of ART delivery | 2004-2005 | South Africa (Western Cape) | Hospital-outpatient and community-based (urban) |

| Pop-Eleches et al. 201170 | Journal article | Behavioural | Mobile phone SMS | 2007-2008 | Kenya | Community-based (rural) |

| Roux 200482 | Master's thesis | Behavioural | Diary cards vs. standard-of-care | 2004 | South Africa (North West Province) | Community-based (rural) |

| Sarna et al. 200864 | Journal article | Behavioural | DOT (TWOT) | 2003-2004 | Kenya (Mombasa) | Hospital-outpatient (urban) |

| Sherr et al. 201065 | Journal article | Structural | Non-physician provider | 2004-2007 | Mozambique (Central Region) | Hospital-outpatient (urban) |

| Stubbs et al. 200966 | Journal article | Behavioural, cognitive and affective | Treatment supporter | 2004-2006 | Mozambique (Central Region) | Hospital-outpatient (urban) |

| Taiwo et al. 201069 | Journal article | Behavioural, cognitive and affective | Treatment supporter, with DOT (DAOT) | 2006-2008 | Nigeria (Jos) | Hospital-outpatient (urban) |

| Thurman et al. 201075 | Journal article | Cognitive, affective, biological | Case manager | 2006 | Rwanda (Entire Country) | Community-based (unknown) |

| Torpey et al. 200867 | Journal article | Behavioural, cognitive and affective | Treatment supporter | 2007 | Zambia (Northern, Luapula, Central, and Copperbelt Provinces) | Hospital-outpatient (unknown) |

| Udo et al. 200778 | Conference abstract | Behavioural, cognitive and affective | Treatment supporter | 2007 | Nigeria (Lower Cross River Basin) | Community-based (rural) |

| van Loggerenberg et al. 201081 | Conference abstract | Cognitive | Individual vs. group education counselling | 2007-2009 | South Africa (Durban) | Community-based (urban) |

ART = antiretroviral treatment, SMS = short message service, DOT = directly observed therapy, DAOT = daily DOT, TWOT = twice-weekly DOT

Table 3.

Summary table of results of interventions on ART adherence in sub-Saharan Africa

| Study | Sample size | Study type | Length of follow-up (months) | Loss to follow-up | Intervention group | Comparison or control group | Adherence measurement | Adherence definition* | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Busari et al. 200979 |

420 | RCT | 8 | Not reported |

Ten structured education modules addressing “issues on adherence such as benefits of treatment, family and social support, adverse drug effects, psychological factors, substance abuse, patient- provider relationship, patient's self efficacy, and effect of traditional/cultural values” |

Standard of care; with “traditional casual patient education” by nurses on wards |

Adherence measure not reported |

“Mean adherence rate”, frequency of OI, mortality |

Mean adherence rate: 99% in intervention vs. 88% in control groups (p<0.001); number of OI per patient per month: 0.51 in intervention vs. 1.31, in control group (p=0.002). Mortality significantly lower in intervention vs. control group (p=0.008) |

| Busari et al. 201076 |

620 | RCT | 8 | Not reported |

Ten structured education modules addressing “issues on adherence such as benefits of treatment, family and social support, adverse drug effects, psychological factors, substance abuse, patient- provider relationship, patient's self efficacy, and effect of traditional/cultural values” |

Standard of care; with “casual patient education” |

CD4 count | “Mean adherence rate”; CD4 count increase |

Mean adherence rate 99% in intervention group vs. 88% in control group (p<0.001). CD4 count 238 in intervention group vs. 141 in control group (p<0.001) |

| Cantrell et al. 200859 |

636 | Before-after | 12 | 9% | Food rations. Non- primary income earners received individual rations, while primary income earners received the individual ration plus other foods sufficient for 6 additional household members |

Standard of care; without food ration |

Medication possession ratio (100% - (number of days late for pharmacy refill divided by total days on therapy in the first years)*100); CD4 count |

≥95% adherence; mean CD4 count |

Medication possession ratio higher in intervention vs. control group (RR 1.5; 95% CI 1.2- 1.8). No significant difference in CD4 count (132 vs. 129, p=0.96) |

| Chang et al. 2008a,84 Chang et al. 2008b77 |

1200 | Prospective cohort |

6 | Not reported |

Biweekly home visits by treatment supporters to address treatment benefits and side effects, and assess adherence through questions and pill count. Half of the treatment supporters received mobile phones to report clinical and adherence data to higher-trained providers for review and triage |

Standard of care; without treatment supporter |

Provider-based assessment of overall patient population improvement in adherence |

Likert scale (1-5, 1 = strongly agree, 5 = strongly disagree) |

20% “strongly agreed” and 49% “agreed” that the interventions improved patient adherence. Significance levels not reported |

| Chang et al. 201071 |

1336 | Cluster RCT; 15 ART clinics randomized 2:1 to receive the intervention |

27 | 3% | Biweekly “clinic and home-based provision of counselling, clinical, adherence to ART, and social support” |

Standard of care; without treatment supporter |

Home-based and clinic- based pill count; self- reported adherence (standard questionnaire); viral load; CD4 count |

≥95% and 100% adherence by pill count; 100% adherence by self-report; cumulative risk of virologic failure; viral load suppression (<400 copies/mL); median CD4 count |

Risk of virologic failure significantly lower in intervention vs. control group at 96 weeks (RR 0.50, 95% CI 0.31-0.81), 120 weeks (RR 0.59, 95% CI 0.22-1.60), 144 weeks (RR 0.39, 95% CI 0.16–0.95), 168 weeks (RR 0.30, 95% CI 0.097–0.92), 192 weeks (RR 0.067, 95% CI 0.0065–0.71) No significant effect on risk of virologic failure in earlier periods. No significant effect on pill count, self- reported adherence, or median CD4 count |

| Chung et al. 200988 |

400 | RCT | 18 | 13% | Patients randomized to control and one of three intervention groups: 1) educational counselling alone, 2) alarm device for first six months alone, or 3) educational counselling with alarm device for first six months |

Standard of care; no educational counselling or alarm device |

Monthly pill counts; CD4 count; viral load |

Mean adherence rate; median CD4 count; median viral load |

Mean adherence rate over 18 months similar (ranging from 89% to 95%) but significantly different between the four groups (p=0.03). Neither CD4 count nor viral load were significantly different between the groups at 18 months |

| Idoko et al. 200760 |

175 | Prospective cohort |

12 | 17% | DOT in one of three intervention groups: 1) DAOT; 2) TWOT; or 3) WOT, provided by patient-selected treatment supporters |

Standard of care; self-administered therapy |

CD4 count; viral load |

Viral load suppression (<400 copies/mL); median CD4 count; and median viral load |

No significant differences between intervention groups and comparison group in outcomes at 48 weeks |

| Kabore et al. 201072 |

587 | Prospective cohort |

18 | 14% | “Community-based support services” (home-based care or food support) |

Standard of care, no home-based care or food support |

Self-reported adherence (standard questionnaire), clinic-based pill count; CD4 count |

≥95% adherence by self-report and pill count; median CD4 count |

Receiving home- based care support services was associated with better adherence based on pill count (69% vs. 58%; p=0.035) No significant difference in median CD4 count between the two groups |

| Lester et al. 201073 |

538 | RCT | 12 | 8% | Weekly SMS from study clinicians asking “How are you?” requiring a response within 48 hours |

Standard of care; no SMS |

Self-reported adherence (standard questionnaire); viral load |

≥95% adherence; viral load suppression (<400 copies/mL) |

Compared to the control group, receiving weekly SMS was associated with a lower risk of reporting non- adherence (RR=0.81; p=0.006) and lower risk of having virologic failure (RR=0.85; p=0.04) |

| Mugusi et al. 200968 |

621 | RCT | 12 | 16% | Calendar for record- keeping of dose intake (first intervention group); treatment supporters (second intervention group) |

Standard of care; regular adherence counselling without either calendars or a treatment supporter |

Self-reported adherence (standard questionnaire); CD4 count; weight changes |

≥95% adherence; mean CD4 count; mean BMI |

No significant differences between the three groups in any of the three adherence outcomes |

| Nachega et al. 200985 |

222 | RCT | 24 | Not published |

DAOT | Self-administered ART |

CD4 count; viral load |

Mean CD4 count; viral load suppression (<400 copies/mL) |

No significant differences either at 12 or 24 months between the intervention and the control group in the mean change of CD4 or the proportion of virally suppressed patients |

| Nachega et al. 201074 |

274 | RCT | 24 | 7% | DAOT, with treatment supporter selected using a “personal network inventory instrument” “that allowed patients to identify individuals who were aware of their HIV diagnosis, supportive of their needs, and who felt could support adherence”.74 Treatment supporters underwent a baseline training session. Both treatment supporters and patients received four additional baseline educational counselling session and refresher course every three months |

Self-administered ART, with treatment supporter chosen without network inventory instrument and only one baseline educational counselling session for the treatment supporter and the patient |

Pill count; CD4 count; viral load; |

≥95% of pills taken (according to pill count); median CD4 count; viral load suppression (<400 copies/mL) |

Median CD4 count increase at 6 months significantly greater in interventions vs. control group (148 vs. 111; p=0.02), but not significantly different at any other time-points. No significant effect of intervention on viral suppression or adherence assessed by pill count |

| Ndekha et al. 2009a61 |

491 | RCT | 3 | 3% | Supplementary feeding with ready-to- use fortified, energy- dense, lipid paste |

Supplementary feeding with corn/soy blend flour |

Self-reported adherence (standard questionnaire); CD4 count; viral load |

% of missed doses within the preceding day, week, month, or ever; mean CD4 count; mean viral load |

No significant differences in self- reported adherence, CD4 count, or viral load |

| Ndekha et al. 2009b62 |

336 | RCT | 9 | 5% | Supplementary feeding with ready-to- use fortified, energy- dense, lipid paste (only in individuals having improved BMI within the first three months of the intervention) |

Supplementary feeding with corn/soy blend flour (only in individuals having improved BMI within the first three months of the intervention) |

Self-reported adherence (standard questionnaire); CD4 count; viral load |

% of missed doses within the preceding day, week, month, or ever; mean CD4 count; mean viral load |

No significant differences in self- reported adherence, CD4 count, or viral load |

| Pearson et al. 200763 |

350 | RCT | 12 | 19% | Treatment supporters delivered six weeks of DAOT, and “provided education about treatment and adherence and sought to identify and mitigate adherence barriers”63 |

Standard of care; self-administered dosing |

Self-reported adherence (standard questionnaire); CD4 count |

% of prescribed doses taken over the previous 7 days; mean CD4 change |

Mean medication adherence significantly higher in intervention group vs. control group at 6 months (93% vs. 85%) and at 12 months (94% vs. 88%). No significant difference with respect to mean CD4 change |

| Pienaar et al. 200683 |

749 | Prospective cohort |

6 | Not reported |

Five different models of ART delivery; three community- based models (doctor- led primary care clinic, nurse-led primary care clinic, integrated primary care clinic) and two hospital-based models (rural district hospital, hospital-based specialist service) |

Comparison between the five different models of care |

Self-reported adherence (standard questionnaire), viral load |

100% self- reported adherence; viral load suppression (<400 copies/mL) |

No significant differences in self- reported adherence across models of ART delivery. Virologic suppression significantly more likely in the community-based vs. hospital-based models (95% vs. 88%; p=0.02) |

| Pop-Eleches et al. 201170 |

431 | RCT | 12 | 16% | Four SMS intervention groups (short daily reminders, short weekly reminders, long daily reminders, or long weekly reminders) |

Standard of care; no SMS |

Medication events monitoring system (MEMS) |

> 90% adherence according to MEMS; treatment interruption ≥48 hours |

Adherence significantly more likely in the group receiving weekly SMS reminders vs. the control group (53% vs. 40%, p- 0.03) at 48 weeks. Treatment interruptions significantly less likely in the group receiving weekly reminders vs. the control group (81% vs. 90%, p=0.03) at 48 weeks |

| Roux 200482 | 85 | Before-after | 1 | Not reported |

Diary cards with calendars showing medication dosing schemes |

Standard of care; without diary cards |

Self-reported adherence (standard questionnaire) |

>85% adherence |

Self-reported adherence did not differ significantly before vs. after the intervention (100% vs. 99% with >85% adherence, p=0.32) |

| Sarna et al. 200864 |

234 | RCT | 18 | 4% | TWOT delivered by nurses for 24 weeks. In addition, community health workers “traced participants who missed visits and carried medications home for those who, for reasons of ill-health, were unable to visit” the ART clinic |

Standard of care; no TWOT, no tracing |

Clinic-based pill count, self- reported adherence (standard questionnaire); CD4 count; viral load; BMI |

≥95% adherence according to pill count; 100% adherence according to self-report; median CD4 count increase; viral load suppression (<400 copies/mL) |

Adherence according to pill count five times more likely in TWOT group vs. control group (p<0.001) during the interventions (weeks 1-24). No significant differences in adherence after the intervention. No significant differences in CD4 count or viral load suppression |

| Sherr et al. 201065 |

5892 | Retrospective cohort |

6 | 12% | Care provided by a non-physician clinician |

Care provided by a physician |

Pharmacy refill data |

≥90% adherence |

Adherence significantly higher in intervention group in the first 6 months after initiating ART (RR=1.05; 95% CI: 1.02-1.09) |

| Stubbs et al. 200966 |

434 | Retrospective cohort |

6 | 0% | Treatment supporters (from the community or the patient's family) provided “psycho-social support” |

No treatment supporter |

Pharmacy refill data |

≥90% adherence |

Patients in comparison group more likely to be non-adherent than patients in intervention group, after adjusting for other factors (adjusted OR=9.47; 95% CI 2.37-37.86) |

| Taiwo et al. 201069 |

499 | RCT | 12 | 10% | Treatment supporters provided DOT, assisted in reporting and managing adverse effects, and reminded patients of drug pick- up |

Standard of care; without treatment supporter |

Pharmacy refill data; CD4 count; viral load |

≥95% adherence; CD4 count increase; viral load suppression (<400 copies/mL) |

Significantly higher odds of adherence in intervention group vs. control group at 24 weeks (OR =3.06, p<0.01) and 48 weeks (OR=1.95, p<0.01). Undetectable viral load significantly more likely in intervention group at week 24 (62% vs. 50%; p<0.05). No significant differences in either viral load suppression at week 48 or CD4 count increases at weeks 24 and 48 |

| Thurman et al. 201075 |

52 case managers |

Before-after | Not reported |

Not reported |

Case managers (nurses or social workers) “identified clients’ needs, linked them with service providers in the community and met regularly with clients at the facility and clients’ homes to assess their progress and adjust the care plan as needed.” They “also worked closely with medical staff to monitor client health, and trained and supported community volunteers who conducted home- based care” |

Standard of care; before the introduction of case managers |

Provider-based assessment of overall patient population improvement in adherence |

Subjective question: “How, if at all, has the program influenced clients’ ART adherence?” |

93% of case managers “felt the program increased ART adherence” |

| Torpey et al. 200867 |

500 | Before-after | 12 | 0% | Treatment supporters (from the community) provided “support to improve adherence” and conducted “community visits to track down patients” |

Standard of care; before the introduction of treatment support workers |

Self-reported adherence (standard questionnaire) |

100% adherence |

No significant difference in self- reported adherence before and after the introduction of treatment supporters (p>0.05) |

| Udo et al. 200778 |

150 | Before-after | Not reported |

Not reported |

Treatment supporters (“family or peer group support persons”) addressed “problems accessing drugs, adherence, supportive therapies, and appointments. Support persons employed ringing bells, patting on shoulders; telephone calls to remind clients take their drugs” |

Standard of care; before the introduction of treatment support workers |

Self-reported adherence |

Yes/No statement of ability to take ART on time |

After the intervention, 80% of patients were able to take ART on time vs. 43% before the intervention |

| van Loggerenberg et al. 201081 |

297 | RCT | 9 | Not reported |

Individualized adherence counselling (two group counselling sessions prior to ART initiation, five one-on- one “motivational interviewing” sessions post-initiation, and ad- hoc counselling support) |

Group adherence counselling (three group counselling sessions prior to ART initiation and ad-hoc counselling support) |

Viral load | Viral load suppression (<400 copies/mL); |

No significant difference in viral load suppression between the intervention and the control group |

The adherence definition is either the cut-off value used to distinguish between adherent and non-adherent patients or a continuous measure of adherence. N = sample size, RCT = Randomised Clinical Trial, ART = antiretroviral treatment, DOT = directly observed therapy, DAOT = daily DOT, WOT = weekly DOT, TWOT = twice-weekly DOT, SMS = short messaging service, BMI = body mass index, OI = opportunistic infections

Study characteristics

Table 2 provides a description of study characteristics (type of publication, intervention category, intervention type, study period, geographical location and health care setting), and Table 3 shows a detailed summary of the different studies, including the number of patients enrolled in each study, the follow-up time, numbers lost to follow-up, descriptions of the intervention and the control (or comparison) group, the method of adherence assessment, the definition of adherence used, and the study results. Studies were conducted between 2003 and 2009 and published between 2004 and 2010, over two-thirds of which were published in the last two years. The median sample size was 433 individuals (interquartile range (IQR) 274-620) and the median length of follow-up was 12 months (IQR 7-18 months). Twelve studies took place exclusively in urban hospital outpatient clinics; five studies took place only in rural community-based clinics; and the remaining studies either took place in several types of settings or did not provide sufficient information to classify the setting (Table 2).

Adherence interventions

Fourteen studies used interventions combining behavioural, cognitive, and affective components (Table 1). These interventions included treatment supporters providing both emotional and instrumental adherence support.66-69, 71, 77, 78, 84, 87 One study combined behavioural, cognitive, affective, and biological interventions through combinations of treatment supporters, nutritional support, financial support, psychosocial support, and education sessions.72 Purely behavioural interventions used directly observed therapy,60, 63, 64 diary cards, 82 and cell phone short message services (SMS) to remind patients to take their ART medication.70, 73 Several interventions provided directly observed therapy (DOT) in addition to other adherence support. We classified these interventions as “treatment supporter” rather than “DOT”, and reserved the classification “DOT” for interventions confined exclusively to the direct observation of pill taking, because the observed effects of treatment supporters must be attributed to the package of interventions delivered by the treatment supporter, rather than to DOT alone. Purely biological interventions used varying types of food supplements.59, 61, 62 Structural interventions included several models of delivery,65, 83 differing in the type of health worker providing routine adherence support or the type of health care setting.

Studies of the same intervention type were heterogeneous regarding the precise intervention utilized, length of follow-up, study design, intervention characteristics, and study settings. For example, in the group of studies using DOT60, 63, 64, 69, 74, 85 the frequency of observed therapy varied from daily to once-weekly observations. In studies of treatment supporters,63, 66-69, 71, 72, 77, 78, 84 the person providing the support ranged from family and friends, to neighbours, community health workers, and HIV-infected community members. Treatment supporters performed different tasks in different studies, including psychosocial support,66, 72 education about ART,63 identification of barriers to adherence,63 adherence measurement,71, 77, 84 reminding patients to pick up or take their drugs,69, 78 DOT,63, 69 assessment of adverse events,71, 77, 84 and triage to higher-level health care providers.71, 77, 84

Adherence assessment

Adherence was assessed by a variety of approaches (Table 3), including subjective and objective adherence measurement instruments. Subjective instruments included patient recall of the number of missed doses in the past three days, seven days, or 30 days (eleven studies),61-64, 67, 68, 71-73, 82, 83 patient focus groups in which participants were asked if they “were able to take their drugs as and when due” (one study),78 and health-worker opinions on whether an intervention had improved patient adherence (two studies).75, 77, 84 Objective instruments included pharmacy refill rates (four studies),59, 65, 66, 69 pill counts in clinics (five studies),64, 71, 72, 74, 88 the Medication Event Monitoring Systems (one study),70 viral load levels or CD4 cell count (sixteen studies),59-64, 68, 69, 71-74, 76, 81, 83, 85, 88 and body mass index in (two studies).64, 68 Sixteen studies used several of these adherence assessment techniques.59-64, 68, 69, 71-74, 76, 79, 83, 88

Intervention outcomes

Seventeen of the twenty-six studies reported a significant improvement in adherence when comparing intervention and comparison group for at least one outcome measurement and at least one time point during the study's observation period (Table 3).59, 63-66, 69-76, 78, 79, 83, 85, 88 The interventions tested in the studies with significant effect included structured teaching programmes,76, 79 food rations,59 DOT,64, 85 treatment supporters with DOT,63, 69 treatment supporters without DOT,66, 71, 72, 78 non-physician providers,65 different models of ART delivery,83 and mobile phone SMS.70, 73 Two additional studies reported an improvement in adherence, one providing treatment supporters and another providing case managers;75, 77, 84 however, assessments were based on the subjective opinion of health care providers and the significance level of the effect was not reported. The remaining eight studies – which included evaluation of treatment supporters,67, 68 DOT,60, 89 food supplements,61, 62 and diary cards,82 and educational counselling90 – reported insignificant results across all time points of observation and adherence measures used.

Ten of the fifteen RCTs,63, 64, 69, 70, 74, 76, 79, 85, 88 six of the seven cohort studies,65, 66, 71, 72, 77, 83, 84 and three of the five before-after studies59, 78 found improved adherence, according to at least one outcome measure. It is important to note, however, that, with three exceptions73, 76, 79 all studies that found a significant intervention effect either did not find a significant effect consistently over time,64, 69, 85 did not find a significant effect on self-reported adherence,91 did not assess any biological outcome,65, 66, 70, 75, 78, 79, 82, 83 or did not find a significant effect on biological outcomes.59, 62-64, 67-69, 85

Risk of bias

Fifteen of the studies included in the final review were RCTs61-64, 68-71, 73, 74, 76, 79, 81, 85, 88 and eleven were observational. Of the observational studies, six were cohort studies60, 65, 66, 72, 77, 83, 84 and five used before-after comparisons to assess intervention effect.59, 67, 75, 78, 82 In most hierarchies of evidence, ordering study designs by risk of bias, RCTs rank above observational studies.92 However, this ranking could be reversed for specific studies, because RCTs can suffer from biases, limiting the strength of evidence derived from their results, and observational studies can have characteristics that increase the evidence strength, such as good control of confounding or large effect size.58

Regarding safeguards against selection bias, of the fifteen RCTs included in this review, five reported the use of both sequence generation for randomization and allocation concealment,61-64, 73 while two reported only the use of sequence generation70 and one reported only allocation concealment.69 Regarding measures to minimize performance bias, only two studies, comparing nutritional interventions, described blinding study participants and healthcare providers,61, 62 With four exceptions,61, 62, 64, 73 none of the RCT studies stated whether the outcome assessors had been blinded, which would safeguard against detection bias. Judging from the descriptions of outcome assessment, however, it is likely that in the elicitation of subjective adherence the assessors were mostly aware of the trial assignment, but that laboratory personnel measuring biological outcomes and analysts were blinded. Finally, based on the outcomes stated in the methodology section of each report, all RCTs appear to have completely reported the results of their stated outcomes. We also compared the reported outcomes of RCTs with those registered with either www.controlled-trials.com or www.clinicaltrials.gov and did not detect any evidence of selective reporting of primary or secondary adherence outcomes.63, 70, 73, 74, 81, 85, 88

In all observational studies, appropriate eligibility criteria were defined, which were applied equally to all study participants, and outcome assessment did not differ by intervention assignment. However, only one of the five before-after studies used a control group to subtract out secular time changes in the comparison of adherence before and after the intervention,59 and only three of six cohort studies controlled for different distributions of potential confounding factors between intervention and comparison groups.65, 66, 72 In the seventeen publications that reported study loss to follow-up, the loss was always less than 20%, i.e. less than the threshold proposed for potentially significant selection bias when individuals are not missing at random.93 In more than half of these reports, loss to follow-up was less than 10%.59, 61, 71, 73, 74,62, 64, 66, 67 The majority of the publications that did not report loss to follow-up were conference abstracts.76, 78, 79, 81, 84, 85

Discussion

To ensure the long-term success of the recent ART scale-up in SSA, effective interventions to achieve and maintain high levels of ART adherence are urgently needed. Our systematic review identified 26 studies investigating the effectiveness of interventions intended to improve adherence in SSA. A number of important insights emerge from the review. The studies investigate six types of adherence-enhancing interventions, comprising SMS and other reminder devices, treatment supporters, DOT, education and counselling, food supplements, and different organizations of ART delivery. For each intervention type there is at least one RCT63, 64, 70, 73, 76, 79 or one observational study 59, 72, 75, 77, 78, 83, 84, 65, 66, 69 demonstrating effectiveness. However, before policy conclusions can be drawn from this evidence, a critical examination of the evidence is required.

First, it is important to consider the magnitude of the effect, not merely the statistical significance. In studies finding significant effects, these effects constituted an improvement of 10% or less in four cases,63, 65, 83, 88an improvement between 10% and 20% in two cases,72, 73 and an improvement above 20% in 12 cases.59, 64, 66, 69-71, 74-79, 84 While relatively small effect sizes may indicate that it may not be worthwhile to invest in the intervention, investment decisions require intervention costing and economic evaluation comparing achievable effects to costs. As yet, such studies are lacking.

A second issue to consider is that initial improvement in adherence may not persist over time. Three RCTs found a significant intervention effect by some measure of adherence (viral suppression,69 CD4 count,74 and self-report of missing doses and pill count64) in the first half year of the trial, but loss of the intervention effect in later trial phases. These results suggest that evidence of effectiveness of adherence-enhancing interventions based on studies of short duration may not be generalizable to the longer term. Since ART is life-long, adherence-enhancing interventions whose effectiveness is limited to a few months would contribute little to overall treatment success. Future studies should thus attempt to observe effectiveness for at least one year. Moreover, it would be very valuable if some of the studies in this review, which found significant effect, continued for several more years to determine long-run intervention effectiveness.

In this context, it is important to consider that high levels of antiretroviral treatment adherence may be less essential in the later than in the initial phases of treatment. In a recent study, Lima et al. report that the risk of viral rebound due to imperfect adherence decreases with duration of viral suppression.15 Thus, it is possible that interventions that increase adherence in the first months after ART initiation will improve long-term biological outcomes, even if their effect vanishes over time and adherence decreases in later treatment stages. While these findings suggest that high adherence may not always be a necessary condition of viral suppression, other recent results from SSA indicate that high levels of adherence may also not be a sufficient condition for viral suppression in a proportion of patients.19, 94

Adherence is of course merely a means to achieving good health outcomes of ART, rather than a final outcome in its own right. The relationship between adherence and ART success is clearly strong. However, as the recent studies in SSA indicate, we need to better understand whether, when and why near-perfect adherence may not be necessary or sufficient to attain good ART health outcomes in all patients. In particular, we need more evidence on the factors that allow some patients to maintain good virologic and immunologic outcomes despite imperfect adherence, and the factors leading to treatment failure despite near-perfect adherence. We also need to know whether in the two groups of patients in which the close correspondence between adherence and biological measures does not appear to hold, the relationship between biological measures and health outcomes (morbidity and mortality) is as expected or deviates from the relationship observed in the overall ART patient population.

A third issue to consider in examining the collective evidence on adherence-enhancing interventions in SSA are discrepant findings. For five intervention types whose effectiveness has been demonstrated in at least one study, there are other studies that failed to detect significant effect, namely for non-SMS reminder devices,68, 82, 88 treatment supporters,67, 68 DOT,60, 95 education and counselling,68, 88, 96 and food supplements.61, 62 Because of the limited number of studies within each intervention type, we lack the data to identify sources of the discrepancies. Within each intervention type the precise intervention content can differ, leading to discrepancies. For instance, non-SMS reminder devices included alarm devices and calendars to support adherence; DOT ranged from daily to weekly observed pill taking; and treatment-supporter interventions differed in the selection of the supporter and the intensity and content of the support provided. Further, several factors may limit the ability of some intervention studies to show an effect. For instance, the standard of care in the control group may already produce high adherence in one study, but not in another.97 Ceiling effects may occur when the baseline adherence is high, limiting the potential to show improvement. For example, adherence in Roux et al.82 was 100% before the intervention and 99% after the intervention.

A case in point for discrepant findings is the adherence effect of DOT. Among studies in SSA, one high-quality RCT shows significant adherence improvement due to DOT in both self-reported adherence and biological correlates of adherence.69 A few other studies suggest that DOT may improve adherence but this evidence is comparatively weak, because it is based on subjective or objective adherence measures alone, without demonstrated impact on biological correlates,63, 64 or because it shows that initial biological effects do not last over time.74 A 2009 meta-analysis by Ford et al. of all RCTs conducted in both developed and developing countries to test the effect of DOT in increasing ART adherence concluded that there was no benefit of DOT over self-administered treatment, but emphasized that “the fact that individual trials found opposing results with respect to benefit of directly observed therapy underscores the importance of considering contextual factors in assessment of adherence interventions”.98 A 2010 meta-analysis of DOT effect based on both RCT and observational studies by Hart et al. found that DOT “had a significant effect on virologic, immunologic, and adherence outcomes, although its efficacy was not supported when restricting analysis to randomized controlled trials”.38 This study noted that “interventions varied widely” and identified features of intervention content that improved the effect on adherence (targeting the intervention to individuals at high risk of nonadherenece; maximising patient convenience in participating in the intervention; and providing adherence support in addition to DOT, such as other behavioural interventions).38 While it is thus likely that the intervention context and the precise content determine adherence effect, the robustness of conclusions drawn from analyses of study heterogeneity depends crucially on the number of available studies.99 The worldwide evidence is still limited (10 RCTs in the study by Ford et al.98 and 11 RCTs and 6 observational studies in the study by Hart et al.38). In the case of SSA, more evidence on ART DOT is clearly needed, in particular evidence based on RCTs, before meta-analysis and investigations of study heterogeneity, such as subgroup analysis or meta-regression, can be meaningfully conducted.

Another source of discrepant findings – both across and within studies – is different outcome measures. A large proportion of studies used subjective measures to assess adherence outcomes (self-report or health-worker report) , including several that did not use any other measure, and a few studies that used objective measures did not evaluate any biological correlates of adherence.

Subjective adherence measures are prone to social desirability biases100 and in several studies have not correlated well with plasma drug levels, CD4 counts, or viral loads.101-103 Health workers (including those involved in the care of the control group in a DOT intervention) usually lack direct knowledge of patients’ pill taking behaviour and may thus misestimate true adherence. Objective measurement instruments, such as pharmacy refill data, pill count or medication events monitoring system (MEMS), may not necessarily reflect true pill-taking if patients discard pills or obtain ART from friends, family members, or from pharmacies that are not captured in the refill data.104 In the absence of a ‘gold standard’ measure of adherence, future studies should assess multiple outcomes, including subjective and objective adherence measures and biological correlates of adherence. Since adherence influences CD4 count and VL, which in turn will affect morbidity and mortality, our belief in the robustness and relevance of a study result will increase with the number of distinct outcome measures demonstrating the same result. Conversely, within-study heterogeneity of findings across outcome measure will decrease our belief in study robustness and relevance.

A fourth issue to consider is in how far the studies included in our review differ from those conducted in other settings. Two important insights gained in two decades of ART adherence research outside SSA are not reflected in the studies on the sub-continent. First, interventions derived from a substantive theory of behaviour change tend to be more effective than those that are based on intuition.105, 106 However, unlike many studies in developed countries,30, 36, 107, 108 none of the studies included in this review reported a theoretical basis for the investigated intervention. This lack of theoretical foundation may reflect the poor understanding of how well existing theories of behaviour change are applicable to settings in SSA, even though some models have been explored in the region, such as the Information, Motivation, and Behavioural Skills Model.109, 110 Further research on both established and novel theories of adherence behaviour is needed in SSA and could contribute to the design of more successful interventions. Additionally, in future applications of theory-based interventions, it may be important to consider the role structural barriers may play in SSA compared to more developed regions,111 such as distance to the nearest health care facility. Second, interventions targeted at patients known to be at risk often provide better results than untargeted interventions.112 Unlike many studies in developing countries, which target ART patient sub-populations identified as at high risk for non-adherence107, 113 the articles in this review did not identify specific target populations, thus potentially limiting intervention efficacy. While some particular at-risk populations may not be relevant or difficult to identify in SSA (such as intravenous drug users or men who have sex with men), other targeting strategies employed in developed countries could be feasible, effective, and cost-effective in SSA. DOT, for example, may be appropriate for particular populations,114 such as individuals with depression,115 but not for other populations, such as individuals who are especially sensitive to stigma.116 Other targeting strategies employed commonly in developed countries may be relevant for a wide range of adherence-enhancing interventions in SSA, such as focusing interventions on persons who have failed an ART regimen117, 118 or on persons who have not yet failed a regimen but have been identified as non-adherent through an adherence screening. 119-122

A fifth important consideration for adherence-enhancing intervention in SSA is cost. A recent cost analysis in South Africa indicates that high ART adherence is associated with substantially lower mean monthly direct health care costs.19 This finding suggests that effective adherence support could decrease the cost of ART per patient, which would emphasize the importance of adherence-enhancing interventions at a time when the number of individuals requiring ART continues to grow, while ART funding levels may not increase.123, 124 Future evaluations should include costing studies to test the hypothesis that adherence-enhancing interventions can lead to a net decrease in the costs of ART delivery.

In sum, evidence is emerging that SMS and other reminder devices, treatment supporters, DOT, education and counselling, food supplements, and different organizations of ART can be effective in enhancing ART adherence in some settings in SSA. However, with the exception of SMS reminders evidence is either only based on observational studies, which are unlikely to control completely for unmeasured confounding, or discrepant findings suggest that intervention effect is strongly determined by context or the precise intervention content. Future research efforts should be directed at conducting more RCTs of adherence-enhancing interventions in routine ART delivery in SSA, be based on substantive theories of behavior, and incorporate costing studies to allow economic evaluation of the interventions. In addition to such RCTs, health workers in programmes, which have integrated adherence-enhancing interventions into routine ART delivery, should publish available evidence on the implementation of these existing interventions, using the full armamentarium of programme evaluation methods.

Sustained, high levels of ART adherence will be crucial for the long-term success of treatment programmes in SSA, where most of the people currently receiving and needing ART live and where the options for second-line therapy after first-line failure are often limited. Initial evidence has accrued as to which interventions are likely to significantly improve adherence, but further evaluation studies are clearly needed to confirm intervention effects, determine effect duration, identify the modifying effects of the intervention design and context, and establish intervention cost-effectiveness.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

TB is supported by Grant 1R01-HD058482-01 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD). The funding organization had no role in the design and conduct of the study, in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data, or in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Authors' contributions

TB and MN were jointly responsible for the design of the study. KC, NC and AP did the search of the published work and data extraction, with support from TB and JH. TB wrote the initial draft of the manuscript, all authors contributed to the writing of the paper.

Conflict of interest statements

We declare that we have no conflict of interest

References

- 1.Jerene D, Naess A, Lindtjorn B. Antiretroviral therapy at a district hospital in Ethiopia prevents death and tuberculosis in a cohort of HIV patients. AIDS Res Ther. 2006;3:10. doi: 10.1186/1742-6405-3-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chan KC, Wong KH, Lee SS. Universal decline in mortality in patients with advanced HIV-1 disease in various demographic subpopulations after the introduction of HAART in Hong Kong, from 1993 to 2002. HIV Med. 2006;7(3):186–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2006.00352.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hogg RS, Yip B, Kully C, Craib KJ, O'Shaughnessy MV, Schechter MT, et al. Improved survival among HIV-infected patients after initiation of triple-drug antiretroviral regimens. CMAJ. 1999;160(5):659–65. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hammer SM, Squires KE, Hughes MD, Grimes JM, Demeter LM, Currier JS, et al. A controlled trial of two nucleoside analogues plus indinavir in persons with human immunodeficiency virus infection and CD4 cell counts of 200 per cubic millimeter or less. AIDS Clinical Trials Group 320 Study Team. N Engl J Med. 1997;337(11):725–33. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199709113371101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Palella FJ, Jr., Delaney KM, Moorman AC, Loveless MO, Fuhrer J, Satten GA, et al. Declining morbidity and mortality among patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus infection. HIV Outpatient Study Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1998;338(13):853–60. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199803263381301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Herbst AJ, Cooke GS, Bärnighausen T, KanyKany A, Tanser F, Newell ML. Adult mortality and antiretroviral treatment roll-out in rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Bull World Health Organ. 2009;87(10):754–62. doi: 10.2471/BLT.08.058982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paterson DL, Swindells S, Mohr J, Brester M, Vergis EN, Squier C, et al. Adherence to protease inhibitor therapy and outcomes in patients with HIV infection. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133(1):21–30. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-133-1-200007040-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moore DM, Hogg RS, Yip B, Wood E, Tyndall M, Braitstein P, et al. Discordant immunologic and virologic responses to highly active antiretroviral therapy are associated with increased mortality and poor adherence to therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;40(3):288–93. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000182847.38098.d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wood E, Hogg RS, Yip B, Harrigan PR, O'Shaughnessy MV, Montaner JS. Effect of medication adherence on survival of HIV-infected adults who start highly active antiretroviral therapy when the CD4+ cell count is 0.200 to 0.350 × 10(9) cells/L. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139(10):810–6. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-10-200311180-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wood E, Hogg RS, Yip B, Harrigan PR, O'Shaughnessy MV, Montaner JS. The impact of adherence on CD4 cell count responses among HIV-infected patients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004;35(3):261–8. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200403010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arnsten JH, Demas PA, Grant RW, Gourevitch MN, Farzadegan H, Howard AA, et al. Impact of active drug use on antiretroviral therapy adherence and viral suppression in HIV-infected drug users. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17(5):377–81. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10644.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bangsberg DR, Hecht FM, Charlebois ED, Zolopa AR, Holodniy M, Sheiner L, et al. Adherence to protease inhibitors, HIV-1 viral load, and development of drug resistance in an indigent population. AIDS. 2000;14(4):357–66. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200003100-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shuter J, Sarlo JA, Kanmaz TJ, Rode RA, Zingman BS. HIV-infected patients receiving lopinavir/ritonavir-based antiretroviral therapy achieve high rates of virologic suppression despite adherence rates less than 95%. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;45(1):4–8. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318050d8c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bangsberg DR. Less than 95% adherence to nonnucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitor therapy can lead to viral suppression. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43(7):939–41. doi: 10.1086/507526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lima VD, Bangsberg DR, Harrigan PR, Deeks SG, Yip B, Hogg RS, et al. Risk of viral failure declines with duration of suppression on highly active antiretroviral therapy irrespective of adherence level. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;55(4):460–5. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181f2ac87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gardner EM, Burman WJ, Steiner JF, Anderson PL, Bangsberg DR. Antiretroviral medication adherence and the development of class-specific antiretroviral resistance. AIDS. 2009 doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32832ba8ec. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Conway B. The role of adherence to antiretroviral therapy in the management of HIV infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;45(Suppl 1):S14–8. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3180600766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goldie SJ, Paltiel AD, Weinstein MC, Losina E, Seage GR, 3rd, Kimmel AD, et al. Projecting the cost-effectiveness of adherence interventions in persons with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Am J Med. 2003;115(8):632–41. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2003.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nachega JB, Leisegang R, Bishai D, Nguyen H, Hislop M, Cleary S, et al. Association of antiretroviral therapy adherence and health care costs. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(1):18–25. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-1-201001050-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kalichman SC, Cherry C, Amaral CM, Swetzes C, Eaton L, Macy R, et al. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy and HIV transmission risks: implications for test-and-treat approaches to HIV prevention. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2010;24(5):271–7. doi: 10.1089/apc.2009.0309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bärnighausen T. Access to antiretroviral treatment in the developing world: a framework, review and health systems research agenda. Therapy. 2007;4(6):753–66. [Google Scholar]

- 22.WHO . Towards universal access: priority HIV/AIDS interventions in the health sector, progress report 2010. WHO, UNAIDS and UNICEF; Geneva: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wakabi W. Low ART adherence in Africa. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008;8(2):94. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(08)70010-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mills EJ, Nachega JB, Buchan I, Orbinski J, Attaran A, Singh S, et al. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa and North America: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2006;296(6):679–90. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.6.679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mills EJ, Nachega JB, Bangsberg DR, Singh S, Rachlis B, Wu P, et al. Adherence to HAART: a systematic review of developed and developing nation patient-reported barriers and facilitators. PLoS Med. 2006;3(11):e438. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parruti G, Manzoli L, Toro PM, D'Amico G, Rotolo S, Graziani V, et al. Long-term adherence to first-line highly active antiretroviral therapy in a hospital-based cohort: predictors and impact on virologic response and relapse. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2006;20(1):48–56. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.20.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mannheimer S, Friedland G, Matts J, Child C, Chesney M. The consistency of adherence to antiretroviral therapy predicts biologic outcomes for human immunodeficiency virus-infected persons in clinical trials. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34(8):1115–21. doi: 10.1086/339074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu H, Miller LG, Hays RD, Golin CE, Wu T, Wenger NS, et al. Repeated measures longitudinal analyses of HIV virologic response as a function of percent adherence, dose timing, genotypic sensitivity, and other factors. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;41(3):315–22. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000197071.77482.6e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Byakika-Tusiime J, Crane J, Oyugi JH, Ragland K, Kawuma A, Musoke P, et al. Longitudinal antiretroviral adherence in HIV+ Ugandan parents and their children initiating HAART in the MTCT-Plus family treatment model: role of depression in declining adherence over time. AIDS Behav. 2009;13(Suppl 1):82–91. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9546-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Simoni JM, Frick PA, Pantalone DW, Turner BJ. Antiretroviral adherence interventions: a review of current literature and ongoing studies. Top HIV Med. 2003;11(6):185–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fogarty L, Roter D, Larson S, Burke J, Gillespie J, Levy R. Patient adherence to HIV medication regimens: a review of published and abstract reports. Patient Educ Couns. 2002;46(2):93–108. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(01)00219-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haddad M, Inch C, Glazier RH, Wilkins AL, Urbshott G, Bayoumi A, et al. Patient support and education for promoting adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy for HIV/AIDS. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;(3):CD001442. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bigler S, Nicca D, Spirig R. [Interventions to enhance adherence of patients with HIV on ART: a literature review]. Pflege. 2007;20(5):268–77. doi: 10.1024/1012-5302.20.5.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rueda S, Park-Wyllie LY, Bayoumi AM, Tynan AM, Antoniou TA, Rourke SB, et al. Patient support and education for promoting adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy for HIV/AIDS. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(3):CD001442. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001442.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Machouf N, Lalonde RG. [Directly observed therapy (DOT): from tuberculosis to HIV]. Rev Epidemiol Sante Publique. 2006;54(1):73–89. doi: 10.1016/s0398-7620(06)76696-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cote JK, Godin G. Efficacy of interventions in improving adherence to antiretroviral therapy. Int J STD AIDS. 2005;16(5):335–43. doi: 10.1258/0956462053888934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wise J, Operario D. Use of electronic reminder devices to improve adherence to antiretroviral therapy: a systematic review. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2008;22(6):495–504. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.0180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hart JE, Jeon CY, Ivers LC, Behforouz HL, Caldas A, Drobac PC, et al. Effect of directly observed therapy for highly active antiretroviral therapy on virologic, immunologic, and adherence outcomes: a meta-analysis and systematic review. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;54(2):167–79. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181d9a330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ford N, Darder M, Spelman T, Maclean E, Mills E, Boulle A. Early adherence to antiretroviral medication as a predictor of long-term HIV virological suppression: five-year follow up of an observational cohort. PLoS One. 2010;5(5):e10460. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Heyer A, Ogunbanjo GA. Adherence to HIV antiretroviral therapy part II: which interventions are effective in improving adherence? South African Family Practice. 2006;48(9):6–10. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hirschhorn LR, Oguda L, Fullem A, Dreesch N, Wilson P. Estimating health workforce needs for antiretroviral therapy in resource-limited settings. Hum Resour Health. 2006;4:1. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zaric GS, Bayoumi AM, Brandeau ML, Owens DK. The cost-effectiveness of counseling strategies to improve adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy among men who have sex with men. Med Decis Making. 2008;28(3):359–76. doi: 10.1177/0272989X07312714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Safren SA, O'Cleirigh C, Tan JY, Raminani SR, Reilly LC, Otto MW, et al. A randomized controlled trial of cognitive behavioral therapy for adherence and depression (CBT-AD) in HIV-infected individuals. Health Psychol. 2009;28(1):1–10. doi: 10.1037/a0012715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sanne I, Orrell C, Fox MP, Conradie F, Ive P, Zeinecker J, et al. Nurse versus doctor management of HIV-infected patients receiving antiretroviral therapy (CIPRASA): a randomised non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2010;376(9734):33–40. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60894-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chan AK, Mateyu G, Jahn A, Schouten E, Arora P, Mlotha W, et al. Outcome assessment of decentralization of antiretroviral therapy provision in a rural district of Malawi using an integrated primary care model. Trop Med Int Health. 2010;15(Suppl 1):90–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02503.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rosen S, Fox MP, Gill CJ. Patient retention in antiretroviral therapy programs in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. PLoS Med. 2007;4(10):e298. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gross R, Tierney C, Andrade A, Lalama C, Rosenkranz S, Eshleman SH, et al. Modified directly observed antiretroviral therapy compared with self-administered therapy in treatment-naive HIV-1-infected patients: a randomized trial. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(13):1224–32. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Delmas P, Delpierre C, Cote J, Lauwers-Cances V, Delon S. [Study of the promosud cohort. Predictors of adherence to treatment plans by French patients living with HIV]. Perspect Infirm. 2008;5(7):28–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI) [27 January 2010];2010 Available from: http://retroconference.org/2010/display.asp?page=181.

- 50.International AIDS Society (IAS). Conferences. [27 January 2010];2010 Available from: http://www.iasociety.org/Default.aspx?pageId=3.

- 51.International Conference on HIV Treatment Adherence [27 January 2010];2010 Available from: http://www.iapac.org/AdherenceConference/AdherenceConf2008-info.html.

- 52.mHealthSummit [31 January 2011];2010 Available from: http://www.mhealthsummit.org/

- 53.Auger CP. Information sources in grey literature. Bowker-Saur; London: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hopewell S, McDonald S, Clarke M, Egger M. Grey literature in meta-analyses of randomized trials of health care interventions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(2):MR000010. doi: 10.1002/14651858.MR000010.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gotzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000100. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Berlin JA. Does blinding of readers affect the results of meta-analyses? University of Pennsylvania Meta-analysis Blinding Study Group. Lancet. 1997;350(9072):185–6. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(05)62352-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Sterne JAC. Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Chapter 8: Assessing risk of bias in included studies. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions: The Cochrane Collaboration. 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 58.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist G, Kunz R, Brozek J, Alonso-Coello P, et al. GRADE guidelines: 4. Rating the quality of evidence--study limitations (risk of bias). J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(4):407–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cantrell RA, Sinkala M, Megazinni K, Lawson-Marriott S, Washington S, Chi BH, et al. A pilot study of food supplementation to improve adherence to antiretroviral therapy among food-insecure adults in Lusaka, Zambia. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;49(2):190–5. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31818455d2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]