Abstract

Susceptibility and resistance to systemic autoimmunity are genetically regulated. This is particularly true for murine mercury-induced autoimmunity (mHgIA) where DBA/2J mice are considered resistant to disease including polyclonal B cell activation, autoantibody responses, and immune complex deposits. To identify possible mechanisms for the resistance to mHgIA, we exposed mHgIA sensitive B10.S and resistant DBA/2J mice to HgCl2 and assessed inflammation and pro-inflammatory responses at the site of exposure and subsequent development of markers of systemic autoimmunity. DBA/2J mice showed little evidence of induration at the site of exposure, expression of proinflammatory cytokines, T cell activation, or autoantibody production, although they did exhibit increased levels of total serum IgG and IgG1. In contrast B10.S mice developed significant inflammation together with increased expression of inflammasome component NLRP3, proinflammatory cytokines IL-1β, TNF-α, and IFN-γ, hypergammaglobulinemia, splenomegaly, CD4+ T-cell activation, and production of autoantibodies. Inflammation in B10.S mice was associated with a selective increase in activity of cysteine cathepsin B but not cathepsins L or S. Increased cathepsin B activity was not dependent on cytokines required for mHgIA but treatment with CA-074, a cathepsin B inhibitor, led to transient reduction of local induration, expression of inflammatory cytokines, and subsequent attenuation of the systemic adaptive immune response. These findings demonstrate that sensitivity to mHgIA is linked to an early cathepsin B regulated inflammatory response which can be pharmacologically exploited to abrogate the subsequent adaptive autoimmune response which leads to disease.

Keywords: autoimmunity, inflammation, mercuric chloride, cytokines, T-cell activation, cathepsin B.

Human exposure to mercury is an environmental trigger in the induction of autoimmunity including production of autoantibodies and proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, TNF-α, and IFN-γ and membranous nephropathy (Pollard, 2012). Animal model studies of murine mercury-induced autoimmunity (mHgIA) have contributed significantly to our understanding of the systemic autoimmunity induced by this environmental agent (Germolec et al., 2012). These studies have revealed that the features of mHgIA, which include lymphadenopathy, hypergammaglobulinemia, humoral autoimmunity, and immune-complex disease, are consistent with the systemic autoimmunity of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).

Sensitivity to mHgIA is influenced by both MHC and non-MHC genes and covers the spectrum from non-responsiveness to overt systemic autoimmunity (Schiraldi and Monestier, 2009). All forms of inorganic mercury, including HgCl2, vapor, or dental amalgam, elicit the same disease as do different routes of administration (Pollard et al., 2010). Disease expression is influenced by costimulatory molecules (Pollard et al., 2004), cytokines (Kono et al., 1998), and modulators of innate immunity (Vas et al., 2008) demonstrating that multiple checkpoints and pathways can be exploited to regulate disease. In addition, lupus prone strains exhibit accelerated and more severe systemic autoimmunity following mercury exposure (Pollard et al., 1999).

Resistance to mHgIA lies with non-MHC genes as mouse strains with the same H-2 can have significantly different responses (Hultman et al., 1992). We have shown that DBA/2J mice are resistant to mHgIA and that some of the genes involved lie within the Hmr1 locus at the distal end of chromosome 1 (Kono et al., 2001). However, resistance to mHgIA in DBA/2J mice can be overcome by co-administration of lipopolysaccharides (LPS) (Abedi-Valugerdi et al., 2005) or anti-CTLA-4 treatment (Zheng and Monestier, 2003) arguing that modulation of both innate and adaptive immune pathways contributes to resistance to mHgIA. The DBA/2J is also resistant to experimental autoimmune orchitis (Tokunaga et al., 1993) and experimental allergic encephalomyelitis (Levine and Sowinski, 1973) suggesting that the mechanism of resistance is relevant to identifying therapeutic targets in both systemic- and organ-specific autoimmunity.

Elevated proinflammatory cytokines in humans with mercury-induced autoimmunity (Gardner et al., 2010) and a dependence on IFN-γ- and IFN-γ-related genes (Pollard et al., 2012) in mHgIA suggest that inflammatory events may be important markers of sensitivity to mercury-induced autoimmunity. This is supported by studies showing that subcutaneous injection of HgCl2 results in production of multiple cytokines in the skin overlying the injection site but not in draining lymph nodes or spleen (Pollard et al., 2011). These studies suggest that mercury-induced inflammation may be important in the development of mHgIA.

To test this hypothesis, mHgIA sensitive B10.S and resistant DBA/2J mice exposed to HgCl2 were examined for inflammation and pro-inflammatory markers at the site of exposure. Unlike B10.S mice, DBA/2J had little evidence of induration and expression of proinflammatory cytokines. DBA/2J also lacked splenomegaly, CD4+ T-cell activation, and production of autoantibodies. The inflammatory response in B10.S mice was characterized by elevated cathepsin B activity. Cathepsin B, a lysosomal cysteine protease, involved in the degradation of cellular proteins, influences a variety of immunological processes including inflammasome activation, Toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling, antigen processing, cytokine regulation, T-cell differentiation, and apoptosis (Colbert et al., 2009; Hornung et al., 2008; Maekawa et al., 1998). The cathepsin B inhibitor, CA-074 (Towatari et al., 1991), reduces inflammasome-mediated IL-1β production (Duncan et al., 2009), and inflammation (Menzel et al., 2006) suggesting that it may be effective in inhibiting the local inflammatory response in mHgIA. Short-term treatment with CA-074 dramatically reduced expression of markers of inflammation in mHgIA including the inflammasome component NLRP3 (NLR family, pyrin domain containing 3), and cytokines IL-1β, TNF-α, and IFN-γ. Longer treatment with CA-074 reduced signs of splenomegaly, lymphocyte activation, hypergammaglobulinemia, and autoantibodies compared with mice exposed to HgCl2 alone. Our findings demonstrate that sensitivity to mHgIA is linked to an early cathepsin B regulated inflammatory response which is necessary for the subsequent adaptive autoimmune response leading to disease.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

B10.S-H2s/SgMcdJ, B10.S-H2s-Ifng−/−, B10.S-H2s-Il6−/−, and B10.S-H2s-Casp1−/− were as described previously (Havarinasab et al., 2009; Pollard et al., 2012). Breeding and maintenance were performed under specific pathogen-free conditions at The Scripps Research Institute Animal Facility (La Jolla, California). DBA/2J and C57BL/6.SJL (H-2s) mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory. Experiments were carried out with 5- to 8-week-old animals with 4–12 animals/group. All procedures were approved by The Scripps Research Institute Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Animal rooms were kept at 68°F–72°F and 60%–70% humidity and sterilized cages were replaced each week with fresh water and food.

Induction of mHgIA

Mice were injected subcutaneously (s.c.) through the loose skin over the neck and shoulders with 40 µg HgCl2 (Mallinckrodt Baker Inc, Phillipsburg, New Jersey) in PBS twice/week for either 7 or 14 days as previously described (Kono et al., 1998). Controls received PBS alone. Mice were bled by cardiac puncture following sacrifice and serum was obtained via BD microtainer serum separation tubes (BD Pharmingen, La Jolla, California). Use of HgCl2 was approved by The Scripps Research Institute Department of Environmental Health and Safety.

Histology

Mice were sacrificed at either 7 or 14 days and skin overlying the site of mercury or PBS injection was excised and placed in 10% zinc formalin (Fisher Diagnostics, Middletown, Virginia). Briefly, sections (7 μm) were cut in a cryostat. Slides were placed in Harris Hematoxylin for 45 s, rinsed in double distilled water (ddH20), washed in warm water for 4 min, placed in 1% Eosin for 1 min, washed in ddH20 and then a series of washes was performed in 70% ethanol, 95% ethanol, 100% ethanol and xylene. Slides were mounted in permount (Sigma) and viewed under 10× power.

Skin score determination

B10.S and DBA/2J mice were exposed to mercury for 7 or 14 days. Skin lesion score was determined by estimation of induration at the site of injection. The loose skin over the upper neck and back were grasped between thumb and forefinger to allow an assessment of the skin thickness and the presence of any lesion at the site of injection noted. Animals were scored on a 1–4 scale (1—no induration/no lesion, 2—mild induration/no lesion, 3—moderate induration/with lesion, and 4—severe induration/with lesion). A score of 1 was defined as the preinjection induration for each individual mouse.

Real-time PCR

B10.S and DBA/2J mice were sacrificed after 7 or 14 days exposure and hair around injection site was removed by using Nair hair remover (Church & Dwight Co, Princeton, New Jersey). A 1.34 cm2 piece of skin centered on the site of PBS or HgCl2 injection was then excised and placed directly in TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen Life Technologies, La Jolla, California). Skin was homogenized by first cutting with a scalpel into fine slices and then vortexed vigorously for 1 min. Total RNA was purified using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen Life Technologies) and contaminant DNA was removed using DNase I treatment at 37°C for 10 min (RNase Free DNase I, Invitrogen Life Technologies). One microgram of RNA was reverse transcribed in a total volume of 21 µl using random hexamers, dNTPs, RNase inhibitor (RNaseOUT; Invitrogen Life Technologies), and 200U of SuperScript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen Life Technologies). The cDNA levels of IFN-γ, NALP3, IL-lβ, and TNF-α were measured by real-time PCR using primer sequences as previously described (Giulietti et al., 2001; Sutterwala et al., 2006; Toomey et al., 2010). Levels of cytokines were analyzed using iQ SYBR-Green (Bio-Rad, Hercules, California). The reaction conditions were 94°C for 5 min, followed by 55 cycles of 20 s at 94°C and 30 s at 60°C, the melt curve used 70 cycles of 10 s at 60 + 0.5°C. All PCR reactions were performed using an iCycler iQ (Bio-Rad). The reactions were run in duplicate and values are expressed as attomoles per microgram of RNA.

Determination of cathepsin activity

B10.S, B10.S-Ifng−/−, B10.S-Il6−/−, B10.S-Casp1−/−, C57BL/6.SJL, and DBA/2J mice were sacrificed after 7 days of exposure and hair around injection site removed by Nair hair remover. An 8 mm biopsy punch (Miltex, Inc, York, Pennsylvania) was used to obtain a piece of skin centered on the site of PBS or HgCl2 injection. The tissues were snap frozen and stored at −80°C. Tissues were homogenized in cold 88 mM KH2PO4, 12 mM Na2HPO4, 1.33 mM disodiumEDTA, pH 6.0 using a Mini-BeadBeater-1 and 2 mm zirconia beads (BioSpec Products, Inc, Bartlesville, Oklahoma). Each tissue was beaten for four 30 s pulses interspersed by cooling on ice. Insoluble material was removed by centrifugation and protein content of the supernatant determined by bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, Illinois). Cathepsin B, L, and S activity was determined by fluorescence-based assay using cathepsin-specific substrates (cathepsin B, Arg-Arg; cathepsin L, Phe-Arg; cathepsin S, Val-Val-Arg) labeled with amino-4-trifluoromethyl coumarin according to the manufacturer’s instructions (BioVision, Inc, Milpitas, California). Results were expressed as relative fluorescence units per 2 µg of protein.

Determination of TGFβ1

B10.S and DBA/2J mice were sacrificed after 7 days of exposure and a skin biopsy taken centered on the site of PBS or HgCl2 injection, snap frozen, and stored at −80°C as described above. Tissues were homogenized in 50 mM Tris [pH 7.4], 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 0.5% Nonidet P40, 0.5% deoxycholic acid, and 0.02% NaN3 with protease inhibitor mixture (cOmplete EDTA free, Roche Diagnostics) using a Mini-BeadBeater-1 and 2 mm zirconia beads and soluble protein obtained and quantified as described above. TGFβ1 was determined by ELISA according to the manufacturer’s instructions (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, Minnesota).

Treatment with cathepsin-B inhibitor CA-074

CA-074 (l-3-trans-(Propylcarbamoyl)oxirane-2-carbonyl)-l-isoleucyl-l-proline) (MW 383.44) (Peptide Institute Inc, Japan or EMD4Biosciences, Gibbstown, New Jersey) was used as a cathepsin B inhibitor as it is a more selective inhibitor that its methyl ester CA-074Me (Montaser et al., 2002). As recommended by the manufacturer, CA-074 was diluted in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). The compound was further diluted to 5% DMSO in PBS and 0.1 mg and 0.2 mg in 25 µl injected s.c. between the shoulder blades of B10.S mice every day for 7 or 14 days, respectively. Control B10.S mice received 5% DMSO in PBS alone. CA-074 has been solubilized in PBS (Maekawa et al., 1998) however this proved difficult in our hands.

Flow cytometry

B10.S and DBA/2J mice were sacrificed after 14 days of mercury exposure and total splenocyte numbers as well as T-cell numbers and activation status was assessed by flow cytometry as previously described with minor modifications (Pollard et al., 2011). Prior to isolation, single cell suspensions of mouse spleens were obtained by manual mechanical homogenization, 35 µm cell filtration (Evergreen Scientific, Los Angeles, California) and red blood cells were depleted by 10 min at room temperature in red blood cell lysis buffer (eBiosciences, San Diego, California). Cell suspensions were stained with PerCP-conjugated anti-CD4, FITC-conjugated anti-CD3, and conjugated anti-CD44 (BD Pharmingen). Fluorescence analysis was done using a dual laser BD FACSCalibur flow cytometer using CELLQuest Pro software (BD Biosciences, San Jose, California). Further analysis was done using FlowJo software (Tree Star, Ashland, Oregon). Dead cells were excluded on the basis of forward and side scatter.

Serum IgG, IgG1, and IgG2a

B10.S and DBA/2J mice were sacrificed after 14 days of mercury exposure and serum levels of IgG, IgG1, and IgG2a antibodies were determined by ELISA, according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Immunology Consultants Laboratory, Inc, Newburg, Oregon) as previously described (Pollard et al., 2011). Briefly, serum was diluted 1/50 000 and incubated on polystyrene microtitre wells coated with anti-IgG, -IgG1, or -IgG2a. After a series of wash steps, the presence of bound immunoglobulin was determined by anti-IgG HRP conjugate. Chromogenic substrate was added and the assay was evaluated spectrophotometrically at 450 nm by the SPECTRA Max PLUS384 spectrophotometer using Softmax Pro 3.1.1 software (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, California). Total serum levels were determined by linear regression analysis of the provided standard curve dilutions.

Antinuclear antibody test

B10.S and DBA/2J mice were treated with HgCl2 for 14 days and serum antinuclear antibodies (ANA) determined by indirect immunofluoresence as described previously (Pollard et al., 2004). Briefly, HEp-2 cells on glass slides (INOVA diagnostics, San Diego, California) were incubated with serum diluted 1/100. The presence of bound IgG was detected by a 1/200 dilution of Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (H+L) Abs (Molecular Probes, Carlsbad, California). Anti-nuclear antibody fluorescence intensity was graded on a 0–4+ scale under blinded conditions by an experienced observer. An intensity of 1+ or greater was called positive. The gradations in staining intensity were 1+ = a clearly discernable nuclear staining, dull green in color, 2+ = definite green fluorescence, 3+ = bright green fluorescence tending toward yellow, and 4+ = maximal fluorescence, brilliant yellow-green in color.

Anti-chromatin ELISA test

B10.S and DBA/2J mice were sacrificed after 14 days of mercury exposure and serum levels of anti-chromatin autoantibodies were determined using the QUANTA Lite Chromatin ELISA system (INOVA Diagnostics) modified to suit detection of murine antibodies as previously described (Pollard et al., 2012). Briefly, serum was incubated at a dilution of 1/100. After a series of wash steps, the presence of bound anti-chromatin antibodies was determined by goat anti-mouse IgG HRPO conjugate (Caltag Labs, Burlingame, CA) diluted 1/200. After addition of the chromogenic substrate, the assay was evaluated spectrophotometrically at 450 nm by a SPECTRA Max PLUS384 spectrophotometer using Softmax Pro 3.1.1 software (Molecular Devices). Data were expressed as total absorbance.

Statistical analysis

All data were expressed as the mean and SE. Analysis was done using GraphPad Prism5 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, California). P values less than 0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

mHgIA-Resistant DBA/2 Mice Lack Evidence of Induration at the Site of HgCl2 Exposure

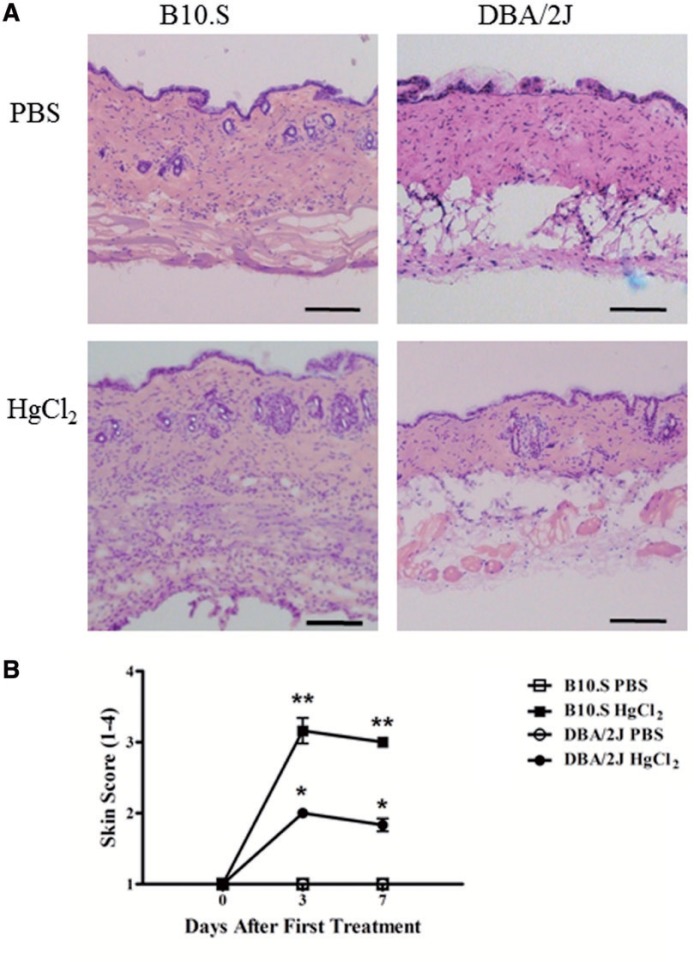

Mercury exposure induces an inflammatory response, particularly at the site of exposure (Pollard et al., 2011), however the contribution of such inflammation to mHgIA is unclear. Histological examination of skin overlying the injection site revealed that HgCl2 exposure resulted in a much more dramatic thickening of the dermis and hypodermis of mHgIA sensitive B10.S compared with mHgIA-resistant DBA/2J mice (Figure 1A). This thickening of the skin was supported by increases in skin score in B10.S mice on days 3 and 7 (P < 0.0001) (Figure 1B). DBA/2J mice also showed increases in skin score on days 3 and 7 (P < 0.05), however, skin scores were greater in the B10.S mice (P < 0.05). Thus, mHgIA-resistant DBA/2J mice have significantly less skin inflammation than mHgIA-sensitive B10.S mice following HgCl2 injection.

FIG. 1.

A, Hematoxylin and Eosin staining of B10.S and DBA/2J skin after 7 days of mercury exposure. B, Skin score assessment of B10.S and DBA/2J skin during 7 days of mercury or PBS exposure. Assessment was performed according to the Materials and Methods. P values compare HgCl2-treated mice compared with PBS controls; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.0001. N = 6/group. Scale bar = 200 µm.

mHgIA-Resistant DBA/2 Mice Lack Markers of Inflammation at the Site of HgCl2 Exposure

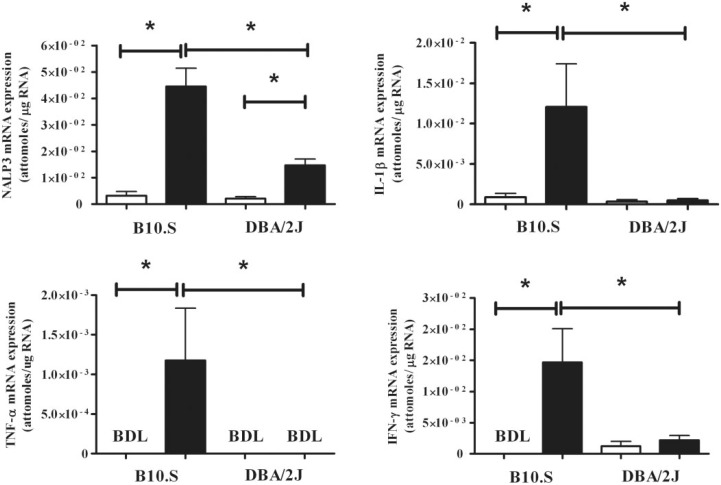

To determine whether the differences in HgCl2-induced inflammation between DBA/2J and B10.S are also reflected in the expression of proinflammatory cytokines and inflammasome components, mRNA expression was determined using real-time PCR. In B10.S mice, HgCl2 exposure resulted in significant increases in IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-1β, and the inflammasome component NRLP3 (P < 0.05) compared with PBS controls (Figure 2). DBA/2J mice showed no increase in IFN-γ, TNF-α, or IL-1β expression following HgCl2 exposure, although they did have a modest increase in NLRP3 (P < 0.05) (Figure 2). Additionally, compared with the DBA/2J mice, HgCl2 exposure in B10.S mice resulted in increased expression of IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-1β, and NRLP3 (P < 0.05) (Figure 2). Thus, mercury exposure in the mHgIA-sensitive B10.S mice leads to increases in mRNA expression of proinflammatory cytokines and the inflammasome component NRLP3, consistent with the greater induration observed in the skin (Figure 1). In contrast, the mHgIA-resistant DBA/2J showed no evidence of increased expression of proinflammatory cytokines including IL-1β even though there was a modest increase in NLRP3 expression.

FIG. 2.

Skin mRNA cytokine profile in B10.S and DBA/2J mice after 7 days of mercury exposure. Mice were treated with PBS (open bar) or HgCl2 (filled bar) for 1 week, skin RNA was purified and analyzed for expression of IFN-γ, IL-1β, TNF-α, and NLRP3 by real-time PCR as described in the Materials and Methods. *P < 0.05. BDL, below detection limit. N = 5/group.

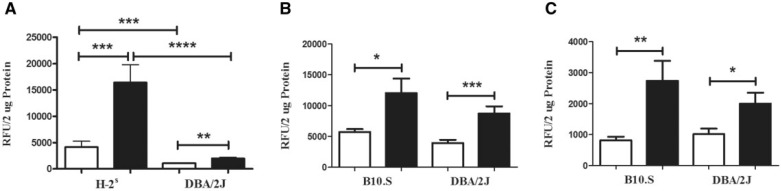

mHgIA-Sensitive Mice Have a Selective Increase in Cathepsin B Activity Compared with mHgIA-Resistant Mice

Cathepsins help regulate inflammatory responses via effects on IL-1β and the NLRP3 inflammasome (Duncan et al., 2009), and other proinflammatory cytokines via processing of TLRs (Garcia-Cattaneo et al., 2012). This suggested that the increased inflammation in mHgIA-sensitive B10.S mice might be explained by increased activity of cathepsins. This was assessed by determining the activity of cathepsins B, L, and S at the site of exposure in mHgIA-sensitive mice (B10.S and C57BL/6.SJL) compared with the mHgIA-resistant DBA/2J. Although DBA/2J mice had increased cathepsin B activity following mercury exposure (P < 0.01), this was significantly less than that found in mercury exposed B10.S (P < 0.002) or C57BL/6.SJL (P < 0.01) and dramatically less when compared with pooled data from B10.S and C57BL/6.SJL (H-2s) (P < 0.0001) (Figure 3A). Background levels of cathepsin B were elevated in B10.S and C57BL/6.SJL compared with DBA/2J mice (P < 0.0002). B10.S and C57BL/6.SJL showed no differences in their cathepsin B responses to mercury or PBS. In contrast, HgCl2 exposure increased the activity of cathepsin L (Figure 3B) and cathepsin S (Figure 3C) in both B10.S and DBA/2J mice. These studies show that the presence of a HgCl2-induced inflammatory response in B10.S mice is associated with a selective increase in cathepsin B activity which is significantly attenuated in the HgCl2-resistant DBA/2J strain.

FIG. 3.

Cathepsin activity in skin of B10.S, C57BL/6.SJL, and DBA/2J mice after 7 days of mercury exposure. Mice were treated with PBS (open bar) or HgCl2 (filled bar) for 1 week, skin was isolated, protein extracted by bead beating and soluble material analyzed for cathepsin activity as described in the Materials and Methods. A, Cathepsin B activity in B10.S and C57BL/6.SJL (shown as H-2s) and DBA/2J mice. B, Cathepsin L activity in B10.S and DBA/2J mice. C, Cathepsin S activity in B10.S and DBA/2J mice. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.002; ****P < 0.0001. N = 6–8/group for B10.S, N = 4/group for C57BL/6.SJL, N = 8 for DBA/2J receiving PBS and 7 for DBA/2J receiving HgCl2.

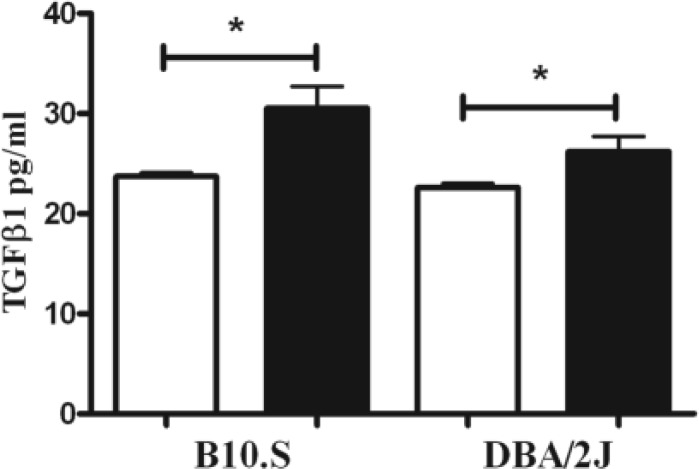

Increased TGF-β1 Does Not Explain the Reduced Cathepsin B Activity in DBA/2 Mice

As TGF-β1 suppresses cathepsin B activity (Gerber et al., 2001), we asked if an increase in TGF-β1 explains the difference in cathepsin B activity between B10.S and DBA/2 mice following mercury exposure. As shown in Figure 4, mercury exposure significantly increased TGF-β1 levels in both DBA/2 and B10.S mice suggesting that increased TGF-β1 is not responsible for failure of HgCl2 to increase cathepsin B activity in the DBA/2.

FIG. 4.

TGF-β1 in skin of B10.S and DBA/2J mice after 7 days of mercury exposure. Mice were treated with PBS (open bar) or HgCl2 (filled bar) for 1 week, skin was isolated, protein extracted by bead beating and soluble material analyzed for TGF-β1 as described in the Materials and Methods. *P < 0.05. N = 4/group.

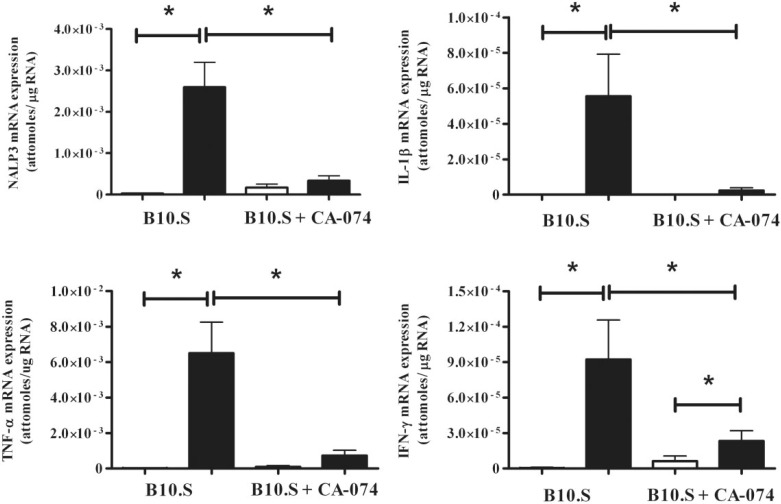

Cathepsin B Inhibitor CA-074 Suppresses Inflammatory Markers in Skin of B10.S Mice After 7 Days of HgCl2 Exposure

To ascertain if inhibition of cathepsin B could suppress expression of proinflammatory cytokines and inflammasome components in HgCl2-induced inflammation, B10.S mice were injected with the cathepsin B inhibitor CA-074. Consistent with the observations in Figure 2 mercury exposure of B10.S mice resulted in significant increases in the expression of IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-1β, and NRLP3 (P < 0.05) compared with PBS controls (Figure 5). In striking contrast mice treated with HgCl2 and CA-074 failed to develop increased expression of TNF-α, IL-1β, or NRLP3 but did have an increase in IFN-γ (P < 0.05) (Figure 5). Compared with mercury alone, treatment with CA-074 and mercury resulted in decreases expression of TNF-α, IL-1β, IFN-γ, and NRLP3 (P < 0.05). The data show that inhibition of cathepsin B suppresses the expression of proinflammatory cytokines and the inflammasome component NRLP3 in mHgIA-sensitive B10.S mice following exposure to mercury.

FIG. 5.

Effect of CA-074 on skin mRNA cytokine profile in B10.S mice after 7 days of exposure to HgCl2. Mice were treated with PBS (open bar) or HgCl2 (filled bar) for 7 days with or without CA-074 (0.1 mg/day). Skin RNA was purified and analyzed for expression of IFN-γ, IL-1β, TNF-α, and NLRP3 by real-time PCR as described in the Materials and Methods. *P < 0.05. N = 4/group.

CA-074 Reduces Features of Autoimmunity in mHgIA-Sensitive B10.S Mice After 14 Days of HgCl2 Exposure

The ability of CA-074 to suppress markers of inflammation in the skin of HgCl2-exposed B10.S mice implied that this compound might reduce features of humoral autoimmunity. To test this possibility, we first determined that a 2-week exposure to HgCl2 could induce features of autoimmunity in B10.S but not DBA/2J mice. As shown in Table 1, HgCl2 exposure produced splenomegaly and an increase in activated CD4+ T cells in B10.S mice but not DBA/2J mice. Mercury exposure also resulted in hypergammaglobulinemia, with increases in IgG (P < 0.002), IgG1 (P < 0.006), and IgG2a (P < 0.0002), in B10.S mice (Table 2). Mercury exposed DBA/2J mice also showed evidence of hypergammaglobulinemia, with significant increases in IgG (P < 0.02) and IgG1 (P < 0.0001) but not IgG2a. However, unlike B10.S mice this was not associated with the presence of ANA or anti-chromatin autoantibodies (Table 2).

TABLE 1.

Effect of HgCl2 and CA-074 on Spleen and T-Lymphocyte Populations in B10.S and DBA/2J Mice After 14 Days of Mercury Exposure

| Mice | N | Age (weeks) | Spleen Cells (×106) | Treatment | Percent of Live Gated Population |

Percent of CD3+CD4+ Population | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD3+CD4- | CD3+CD4+ | CD3+CD4+CD44high | |||||

| B10.S | 6 | 5.0 ± 0.0 | 90.0 ± 12.4 | PBS | 15.6 ± 1.4 | 14.8 ± 0.3 | 20.9 ± 2.1 |

| B10.S | 6 | 5.5 ± 0.6 | 131.5 ± 8.1a,b | HgCl2 | 18.2 ± 1.8a | 17.3 ± 0.7b | 32.5 ± 3.7a,b |

| B10.S | 5 | 5.4 ± 0.4 | 93.9 ± 16.9 | PBS + CA-074 | 13.0 ± 1.0 | 15.7 ± 0.8 | 20.1 ± 1.6 |

| B10.S | 6 | 5.5 ± 0.2 | 94.5 ± 12.2 | HgCl2 + CA-074 | 16.1 ± 1.7b | 16.0 ± 0.7 | 23.9 ± 1.8 |

| DBA/2J | 7 | 5.5 ± 0.0 | 81.2 ± 6.4 | PBS | 4.3 ± 0.3c | 14.2 ± 0.5 | 31.5 ± 1.5c |

| DBA/2J | 7 | 5.5 ± 0.0 | 85.0 ± 8.3c | HgCl2 | 4.9 ± 0.4c | 12.5 ± 1.0 | 34.7 ± 2.4 |

aStatistical significance comparing untreated PBS or mercury exposed mice to the respective PBS or mercury exposed treatment of CA-074 treatment group (P < 0.05).

bStatistical significance compared with the mercury exposed group to the respective PBS control group (P < 0.05).

cStatistical significance comparing DBA/2J mice to the respective PBS or mercury exposed B10.S strain (P < 0.05). Data are presented as mean ± SE.

TABLE 2.

Effect of HgCl2 and CA-074 on Serum IgG, IgG1, IgG2a, and Autoantibodies in B10.S and DBA/2J After 14 Days of Mercury Exposure

| Mice | N | Age (weeks) | Treatment | IgG (µg/ml) | Serum IgG Antibodies and Autoantibodies |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IgG1 (µg/ml) | IgG2a (µg/ml) | ANA (AU) | Anti-Chromatin (OD450 nm) | |||||

| B10.S | 6 | 5.0 ± 0.0 | PBS | 404.2 ± 31.1a | 179.2 ± 9.7 | 90.9 ± 31.3 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.1 ± 0.0 |

| B10.S | 6 | 5.5 ± 0.6 | HgCl2 | 854.2 ± 75.8a,b | 362.5 ± 50.2b | 660.3 ± 85.7a,b | 2.4 ± 0.4b | 3.1 ± 0.4a,b |

| B10.S | 5 | 5.4 ± 0.4 | PBS + CA-074 | 225.0 ± 29.2 | 155.0 ± 84.7 | 173.2 ± 45.8 | 0.2 ± 0.2 | 0.2 ± 0.1 |

| B10.S | 6 | 5.5 ± 0.2 | HgCl2 + CA-074 | 550.0 ± 30.9b | 229.5 ± 62.5 | 300.4 ± 49.5b | 1.5 ± 0.1a,b | 1.6 ± 0.1b |

| DBA/2J | 7 | 5.5 ± 0.0 | PBS | 157.1 ± 52.0c | 146.4 ± 18.5 | 178.6 ± 28.5c | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.1 ± 0.0 |

| DBA/2J | 7 | 5.5 ± 0.0 | HgCl2 | 618.6 ± 111.1b | 532.1 ± 75.3b | 346.4 ± 74.1 | 0.1 ± 0.1c | 0.1 ± 0.0c |

aStatistical significance comparing untreated PBS or mercury exposed mice to the respective PBS or mercury exposed treatment of CA-074 treatment group (P < 0.05).

bStatistical significance compared with the mercury exposed group to the respective PBS control group (P < 0.05).

cStatistical significance comparing DBA/2J mice to the respective PBS or mercury exposed B10.S strain (P < 0.05). Data are presented as mean ± SE AU, arbitrary unit.

Two week treatment of B10.S mice with CA-074 (0.2 mg/day) lowered mean values of IgG (P < 0.005) compared with control B10.S mice treated with PBS only (Table 2) suggesting that CA-074 changes baseline serum immunoglobulin levels. Mercury exposure significantly increased IgG (P < 0.0001), IgG1 (P < 0.0001), and IgG2a (P < 0.0001), and autoantibodies (ANA, P < 0.0005 and anti-chromatin abs, P < 0.0001). Although the levels of IgG (P < 0.01), IgG2a (P < 0.01), and autoantibodies (ANA, P < 0.05 and anti-chromatin abs, P < 0.01) remained elevated in mercury exposed mice treated with CA-074 they were nevertheless significantly decreased from mice receiving mercury alone (Table 2). Treatment of mercury exposed B10.S mice with CA-074 suppressed splenomegaly and the HgCl2-induced increase in CD4+ T-cell activation (Table 1). Thus, inhibition of cathepsin B significantly reduces features of the adaptive immune response of mHgIA.

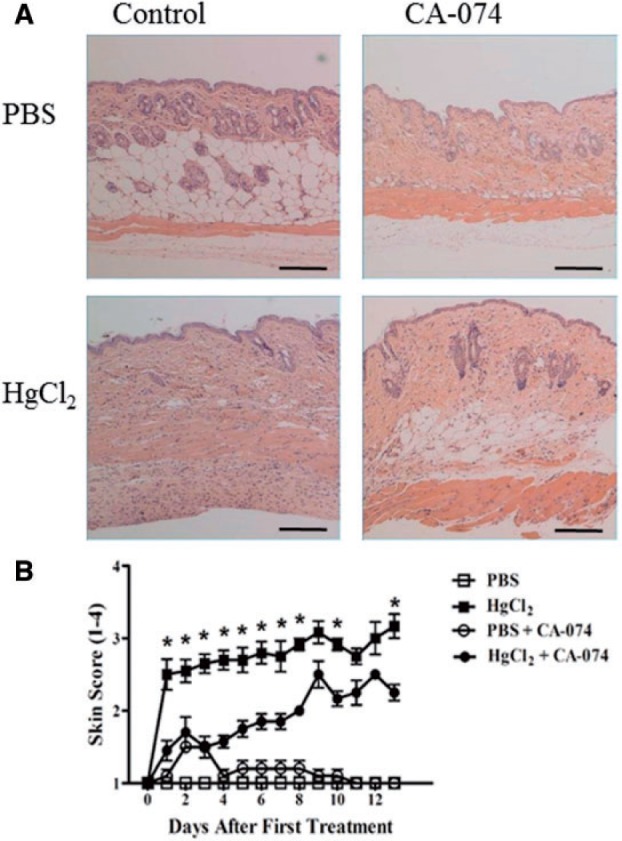

CA-074 Delays Appearance of Skin Induration in mHgIA-Sensitive B10.S Mice After 14 Days of HgCl2 Exposure

Reduction in features of autoimmunity in mice treated with CA-074 for 2 weeks suggested that CA-074 mediated inhibition of cathepsin B may also reduce the magnitude of the inflammatory response in the skin (Figure 6A). CA-074 treatment significantly decreased the severity of skin scores compared with mercury exposed controls particularly during the first week of exposure (P < 0.05) (Figure 6B). HgCl2- and CA-074-treated mice did have significant increases in skin score from day 5–13 (P < 0.05) when compared with PBS- and CA-074-treated mice. As expected, mercury exposure of B10.S mice led to significant increases in skin score assessments from day 1 to the final day 13 (P < 0.0001). Thus, CA-074 treatment delayed the appearance and severity of skin induration and inflammation following exposure to HgCl2.

FIG. 6.

A, Hematoxylin and Eosin staining of B10.S skin after 14 days of mercury exposure with or without CA-074 treatment. B10.S mice were injected with HgCl2 or PBS with or without CA-074 compound (0.2 mg/day) for 14 days. B, Skin score inflammation assessment during mercury exposure in CA-074-treated B10.S mice. Assessment was performed according to the Materials and Methods. Asterisks (*) indicate statistical significance comparing HgCl2-treated B10.S mice with or without CA-074 (P < 0.05). N = 6/group. Scale bar = 200 μm.

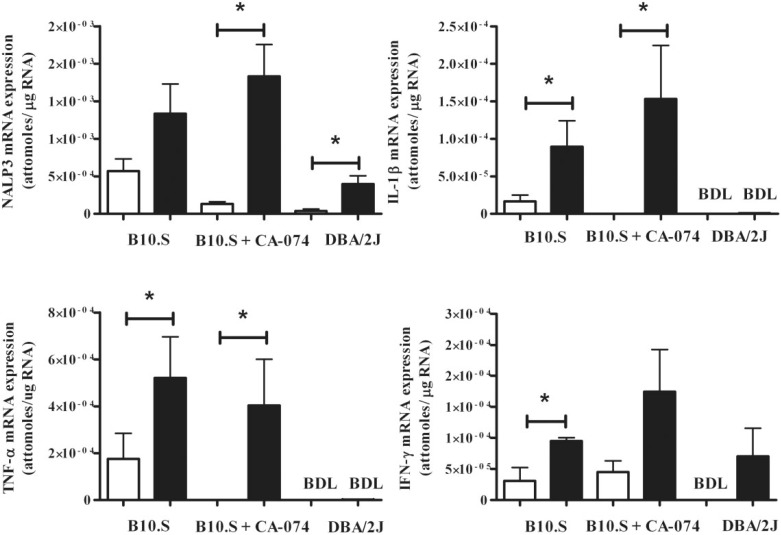

Longer Exposure to HgCl2 Overcomes CA-074 Suppression of Inflammatory Markers in Skin of mHgIA-Sensitive B10.S Mice

The increase in the magnitude of the skin score in CA-074-treated mice (Figure 6B) during a 2-week exposure to mercury suggested a restoration of proinflammatory cytokine expression. This was confirmed by real-time PCR measurement of TNF-α, IL-1β, and NRLP3 (P < 0.05) in mice treated with CA-074 and mercury (Figure 7). Two weeks of mercury exposure in B10.S mice resulted in statistically significant increases in IFN-γ, IL-1β, and TNF-α expression (P < 0.05) (Figure 7) which were not different from mercury exposed B10.S treated with CA-074. Thus, the early inhibition of proinflammatory markers in B10.S mice by CA-074 (Figure 5) was overcome by longer exposure to HgCl2. This supports the observation that CA-074 delays the severity of skin induration and inflammation following longer exposure to HgCl2 (Figure 6B) and suggests that CA-074 impedes the HgCl2-induced inflammatory response but does not suppress it. DBA/2J mice exposed to mercury for 2 weeks showed significant increases in expression of NRLP3 (P < 0.05) but no changes in the expression of IFN-γ, IL-1β, or TNF-α. Thus, mHgIA-resistant DBA/2J mice show a consistent lack of markers of inflammation. These results demonstrate that inhibition of cathepsin B delayed the appearance and severity of the localized inflammatory response induced by exposure to HgCl2.

FIG. 7.

Skin mRNA cytokine profile in B10.S and DBA/2J mice after 14 days of mercury exposure with or without CA-074 treatment. B10.S mice were treated with PBS (open bar) or HgCl2 (filled bar) for 2 weeks with or without CA-074 (0.2 mg/day). DBA/2 mice were treated with PBS (open bar) or HgCl2 (filled bar) for 2 weeks. Skin RNA was purified and analyzed for expression of IFN-γ, IL-1β, TNF-α, and NLRP3 by real-time PCR as described in the Materials and Methods. *P < 0.05. BDL, below detection limit. N = 4/group for B10.S and N = 5/group for DBA/2J.

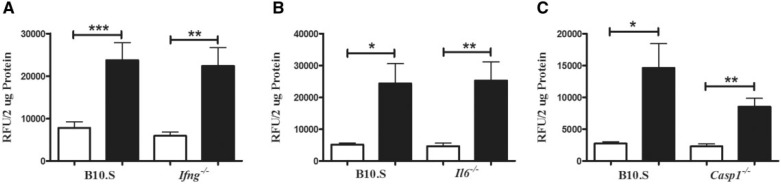

Proinflammatory Cytokines Required for mHgIA Are Not Required for HgCl2 Mediated Increased Cathepsin B Activity

Both IFN-γ and IL-6 are required for mHgIA whereas caspase 1, which is responsible for the processing of IL-1β, is not (Havarinasab et al., 2009; Pollard et al., 2012). To determine whether these proinflammatory mediators are required for HgCl2-induced increase in cathepsin B activity B10.S-Ifng−/−, B10.S-Il6−/−, and B10.S-Casp1−/− mice were exposed to HgCl2 before determining cathepsin B activity (Figure 8). Absence of IFN-γ and IL-6 had no effect on the induction of cathepsin B activity (Figures 8A and 8B), and although activity was somewhat reduced in B10.S-Casp1−/−compared with wild-type mice, this was not significant (Figure 8C). These findings suggest that proinflammatory mediators required for HgCl2-induced autoimmunity affect events downstream of the activation of cathepsin B.

FIG. 8.

Cathepsin B activity in skin of B10.S, B10.S-Ifng−/−, B10.S-Il6−/−, and B10.S-Casp1−/− mice after 7 days of mercury exposure. Mice were treated with PBS (open bar) or HgCl2 (filled bar) for 1 week, skin was isolated, protein extracted by bead beating and soluble material analyzed for cathepsin B activity as described in the Materials and Methods. A, B10.S-Ifng−/−, B, B10.S-Il6−/−, and C, B10.S-Casp1−/−. *P < 0.01; **P < 0.002; ***P < 0.005. N = 7–12/group.

DISCUSSION

Among the spectrum of autoimmune features induced in various strains of mice by mercury, the DBA/2J stands out as one of the most resistant. It does not develop the polyclonal B-cell activation (Abedi-Valugerdi et al., 2005), autoantibody responses, or immune complex deposits (Kono et al., 2001) seen in mHgIA-sensitive strains. Although resistance of the DBA/2J to glomerular immune complex deposits has been linked to a single major quantitative trait locus on chromosome 1, designated Hmr1 (Kono et al., 2001), the failure to develop earlier stages of disease, including inflammation and humoral autoimmunity, has not been addressed. In this study, we noted that the DBA/2J, unlike the mHgIA-sensitive B10.S, fails to develop induration at the site of exposure. Instead the skin over the upper neck and back of DBA/2J mice remained loose and pliable indicating a lack of inflammation. Furthermore, apart from modest increases in NLRP3 expression and cathepsin B activity, DBA/2J mice lack the increase in expression of markers of inflammation seen in the mHgIA-sensitive B10.S. Unlike previous reports (Abedi-Valugerdi et al., 2005), the mercury exposed DBA/2J mice in this study did show evidence of hypergammaglobulinemia although this was not accompanied by T-cell activation or autoantibodies.

In a previous study, mHgIA-sensitive B10.S showed evidence of increased expression of multiple proinflammatory cytokines in the skin overlying the injection site but not in draining lymph nodes or spleen (Pollard et al., 2011); IL-4 was increased in the spleen (Kono et al., 1998). As shown here this localized inflammatory response includes increased expression of proinflammatory cytokines IL-1β and TNF-α prior to the appearance of humoral autoimmunity. This suggests significant contribution by the innate immune response which is supported by the increased expression of NLRP3, which leads to caspase-1 activation and cleavage of pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18, via lysosomal membrane destabilization and activation of the lysosomal cysteine protease cathepsin B (Franchi et al., 2009). Cathepsins can also regulate inflammatory responses via effects on processing of TLRs (Garcia-Cattaneo et al., 2012). Our examination of several cysteine cathepsins revealed a selective increase in cathepsin B activity in B10.S mice compared with DBA/2J. Furthermore, our data show that this selective increase in cathepsin B is an early event in the proinflammatory response following HgCl2 exposure making cathepsin B an attractive pharmacologic target. The cathepsin B-specific inhibitor CA-074 prevents caspase-1 activation (Newman et al., 2009), signaling activities of the NLRP3 and ASC-containing inflammasome and IL-1β and IL-18 maturation (Duncan et al., 2009). Mercury has been shown to localize in lysosomes of macrophages and endothelial cells (Christensen, 1996) and to mediate cathepsin B release from microglia (Sakamoto et al., 2008) leading us to hypothesize that CA-074 might inhibit early events in mercury-induced inflammation and provide insight into the mechanism leading to lack of inflammation in DBA/2J mice. CA-074 did significantly reduce mRNA production of the inflammatory cytokines IL-1β, TNF-α, and IFN-γ and the inflammasome component NRLP3 during 7 days of HgCl2 exposure. Inhibition of cathepsin B by CA-074 has been shown to modulate cytokine expression (Duncan et al., 2009), however it is unlikely that the mechanism is a direct effect on mRNA levels although an influence on posttranslational processing events is a possibility, especially for TNF-α (Ha et al., 2008). The most plausible explanation for the CA-074-mediated reduction of mRNA levels of inflammatory markers found in this study is a reduction in cellular infiltrates at the site of HgCl2 injection.

Inhibition of the HgCl2-induced inflammatory response was transient as CA-074-treated mice did show evidence of proinflammatory cytokine expression with a longer exposure to mercury. Nonetheless, compared with mice exposed to HgCl2 alone, concurrent CA-074 treatment reduced splenomegaly, T-cell activation, and serum immunoglobulins and autoantibodies. The exact mechanism of action of CA-074 in dampening the severity of mHgIA is unclear as cathepsin B impacts immune responses in many ways including antigen processing and presentation, cytokine activation and turnover, T-cell differentiation, TLR signaling and lysosomal-mediated apoptosis (Colbert et al., 2009; Lalanne et al., 2010). Even though IL-1β is increased in mHgIA, a role for the NLRP3 inflammasome is unlikely as absence of either NLRP3 or caspase 1 has little effect on development of disease (Pollard et al., 2012). Effects on inflammation, apoptosis, export of TNF-α, and cell migration have all been proposed as possible mechanisms for reduced incidence of diabetes in cathepsin B-deficient NOD mice (Hsing et al., 2010). The same dose of CA-074 used here (0.2 mg/day) suppressed immune responses to hepatitis B and rabies vaccines in mice (Matsunaga et al., 1993). Higher doses led to a shift toward a Th1-dominated immune response in mice infected with Leishmania major (Maekawa et al., 1998); IL-4, IgE, and IgG1 responses were suppressed and IFN-γ and IgG2a increased. This may explain why CA-074 was not able to reduce the expression of IFN-γ and IgG2a antibodies to control levels, although, these levels were significantly lower than in mice exposed to mercury alone. More importantly, the presence of a Th1 response in CA-074-treated mice may explain the development of proinflammatory cytokine expression with longer treatment as induction of mHgIA is dependent upon IFN-γ. Absence of IFN-γ suppresses hypergammaglobulinemia, autoantibodies, and immune complex deposition but not T-cell activation (Pollard et al., 2012). It is possible that the suppression of inflammatory factors by CA-074 during the first 7 days involves events that are not IFN-γ dependent as absence of IFN-γ did not affect HgCl2-induced increase in cathepsin B activity. Similar observations were made with IL-6- and caspase 1-deficient mice suggesting that the effects of these proinflammatory mediators on mHgIA are downstream of the regulation of cathepsin B activity.

In conclusion, we report that resistance to mHgIA in DBA/2J mice is associated with the absence of a local inflammatory response at the site of HgCl2 exposure. Attempts to model such resistance using CA-074, a cathepsin B inhibitor, in mHgIA-sensitive mice delayed the inflammatory response and dampened the severity of mHgIA. The data demonstrate that development of mHgIA is coupled to an inflammatory response the magnitude of which is influenced by cathepsin B.

FUNDING

The National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (grant numbers ES007511, ES021464, and ES022625 to K.M.P.); An NIEHS Supplement to Support High School and Undergraduate Research Experiences [grant number ES007511-S1 to C.B.T], and a Amylin Pharmaceuticals Research Scholarship, and a Julia Brown Research Scholarship to C.B.T. while an undergraduate at the University of California at San Diego.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors acknowledge the excellent technical services of the Histology Core Laboratory of The Scripps Research Institute. They thank Dwight H. Kono for his comments on the article. This is publication number 20976 from The Scripps Research Institute.

REFERENCES

- Abedi-Valugerdi M., Nilsson C., Zargari A., Gharibdoost F., DePierre J. W., Hassan M. (2005). Bacterial lipopolysaccharide both renders resistant mice susceptible to mercury-induced autoimmunity and exacerbates such autoimmunity in susceptible mice. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 141, 238–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen M. M. (1996). Histochemical localization of autometallographically detectable mercury in tissues of the immune system from mice exposed to mercuric chloride. Histochem. J. 28, 217–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colbert J. D., Matthews S. P., Miller G., Watts C. (2009). Diverse regulatory roles for lysosomal proteases in the immune response. Eur. J. Immunol. 39, 2955–2965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan J. A., Gao X., Huang M. T., O’Connor B. P., Thomas C. E., Willingham S. B., Bergstralh D. T., Jarvis G. A., et al. (2009). Neisseria gonorrhoeae activates the proteinase cathepsin B to mediate the signaling activities of the NLRP3 and ASC-containing inflammasome. J. Immunol. 182, 6460–6469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franchi L., Eigenbrod T., Munoz-Planillo R., Nunez G. (2009). The inflammasome: a caspase-1-activation platform that regulates immune responses and disease pathogenesis. Nat. Immunol. 10, 241–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Cattaneo A., Gobert F. X., Muller M., Toscano F., Flores M., Lescure A., Del Nery E., Benaroch P. (2012). Cleavage of Toll-like receptor 3 by cathepsins B and H is essential for signaling. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 109, 9053–9058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner R. M., Nyland J. F., Silva I. A., Ventura A. M., de Souza J. M., Silbergeld E. K. (2010). Mercury exposure, serum antinuclear/antinucleolar antibodies, and serum cytokine levels in mining populations in Amazonian Brazil: a cross-sectional study. Environ. Res. 110, 345–354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerber A., Wille A., Welte T., Ansorge S., Buhling F. (2001). Interleukin-6 and transforming growth factor-beta 1 control expression of cathepsins B and L in human lung epithelial cells. J. Interferon Cytokine Res. 21, 11–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Germolec D., Kono D. H., Pfau J. C., Pollard K. M. (2012). Animal models used to examine the role of the environment in the development of autoimmune disease: findings from an NIEHS Expert Panel Workshop. J. Autoimmun. 39, 285–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giulietti A., Overbergh L., Valckx D., Decallonne B., Bouillon R., Mathieu C. (2001). An overview of real-time quantitative PCR: applications to quantify cytokine gene expression. Methods 25, 386–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha S. D., Martins A., Khazaie K., Han J., Chan B. M., Kim S. O. (2008). Cathepsin B is involved in the trafficking of TNF-alpha-containing vesicles to the plasma membrane in macrophages. J. Immunol. 181, 690–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havarinasab S., Pollard K. M., Hultman P. (2009). Gold- and silver-induced murine autoimmunity—requirement for cytokines and CD28 in murine heavy metal-induced autoimmunity. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 155, 567–576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornung V., Bauernfeind F., Halle A., Samstad E. O., Kono H., Rock K. L., Fitzgerald K. A., Latz E. (2008). Silica crystals and aluminum salts activate the NALP3 inflammasome through phagosomal destabilization. Nat. Immunol. 9, 847–856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsing L. C., Kirk E. A., McMillen T. S., Hsiao S. H., Caldwell M., Houston B., Rudensky A. Y., LeBoeuf R. C. (2010). Roles for cathepsins S, L, and B in insulitis and diabetes in the NOD mouse. J. Autoimmun. 34, 96–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hultman P., Bell L. J., Enestrom S., Pollard K. M. (1992). Murine susceptibility to mercury. I. Autoantibody profiles and systemic immune deposits in inbred, congenic, and intra-H-2 recombinant strains. Clin. Immunol. Immunopathol. 65, 98–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kono D. H., Balomenos D., Pearson D. L., Park M. S., Hildebrandt B., Hultman P., Pollard K. M. (1998). The prototypic Th2 autoimmunity induced by mercury is dependent on IFN- gamma and not Th1/Th2 imbalance. J. Immunol. 161, 234–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kono D. H., Park M. S., Szydlik A., Haraldsson K. M., Kuan J. D., Pearson D. L., Hultman P., Pollard K. M. (2001). Resistance to xenobiotic-induced autoimmunity maps to chromosome 1. J. Immunol. 167, 2396–2403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lalanne A. I., Moraga I., Hao Y., Pereira J. P., Alves N. L., Huntington N. D., Freitas A. A., Cumano A., Vieira P. (2010). CpG inhibits pro-B cell expansion through a cathepsin B-dependent mechanism. J. Immunol. 184, 5678–5685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine S., Sowinski R. (1973). Experimental allergic encephalomyelitis in inbred and outbred mice. J. Immunol. 110, 139–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maekawa Y., Himeno K., Ishikawa H., Hisaeda H., Sakai T., Dainichi T., Asao T., Good R. A., Katunuma N. (1998). Switch of CD4+ T cell differentiation from Th2 to Th1 by treatment with cathepsin B inhibitor in experimental leishmaniasis. J. Immunol. 161, 2120–2127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsunaga Y., Saibara T., Kido H., Katunuma N. (1993). Participation of cathepsin B in processing of antigen presentation to MHC class II. FEBS Lett. 324, 325–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menzel K., Hausmann M., Obermeier F., Schreiter K., Dunger N., Bataille F., Falk W., Scholmerich J., Herfarth H., Rogler G. (2006). Cathepsins B, L and D in inflammatory bowel disease macrophages and potential therapeutic effects of cathepsin inhibition in vivo. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 146, 169–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montaser M., Lalmanach G., Mach L. (2002). CA-074, but not its methyl ester CA-074Me, is a selective inhibitor of cathepsin B within living cells. Biol. Chem. 383, 1305–1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman Z. L., Leppla S. H., Moayeri M. (2009). CA-074Me protection against anthrax lethal toxin. Infect. Immun. 77, 4327–4336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard K. M. (2012). Gender differences in autoimmunity associated with exposure to environmental factors. J. Autoimmun. 38, J177–J186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard K. M., Arnush M., Hultman P., Kono D. H. (2004). Costimulation requirements of induced murine systemic autoimmune disease. J. Immunol. 173, 5880–5887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard K. M., Hultman P., Kono D. H. (2010). Toxicology of autoimmune diseases. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 23, 455–466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard K. M., Hultman P., Toomey C. B., Cauvi D. M., Hoffman H. M., Hamel J. C., Kono D. H. (2012). Definition of IFN-gamma-related pathways critical for chemically-induced systemic autoimmunity. J. Autoimmun. 39, 323–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard K. M., Hultman P., Toomey C. B., Cauvi D. M., Konoc D. H. (2011). beta2-microglobulin is required for the full expression of xenobiotic-induced systemic autoimmunity. J. Immunotoxicol. 8, 228–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollard K. M., Pearson D. L., Hultman P., Hildebrandt B., Kono D. H. (1999). Lupus-prone mice as models to study xenobiotic-induced acceleration of systemic autoimmunity. Environ. Health Perspect. 107(Suppl. 5), 729–735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto M., Miyamoto K., Wu Z., Nakanishi H. (2008). Possible involvement of cathepsin B released by microglia in methylmercury-induced cerebellar pathological changes in the adult rat. Neurosci. Lett. 442, 292–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiraldi M., Monestier M. (2009). How can a chemical element elicit complex immunopathology? Lessons from mercury-induced autoimmunity. Trends Immunol. 30, 502–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutterwala F. S., Ogura Y., Szczepanik M., Lara-Tejero M., Lichtenberger G. S., Grant E. P., Bertin J., Coyle A. J., Galan J. E., Askenase P. W., et al. (2006). Critical role for NALP3/CIAS1/Cryopyrin in innate and adaptive immunity through its regulation of caspase-1. Immunity 24, 317–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokunaga Y., Hiramine C., Itoh M., Mukasa A., Hojo K. (1993). Genetic susceptibility to the induction of murine experimental autoimmune orchitis (EAO) without adjuvant. I. Comparison of pathology, delayed type hypersensitivity, and antibody. Clin. Immunol. Immunopathol. 66, 239–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toomey C. B., Cauvi D. M., Song W. C., Pollard K. M. (2010). Decay-accelerating factor 1 (Daf1) deficiency exacerbates xenobiotic-induced autoimmunity. Immunology 131, 99–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Towatari T., Nikawa T., Murata M., Yokoo C., Tamai M., Hanada K., Katunuma N. (1991). Novel epoxysuccinyl peptides. A selective inhibitor of cathepsin B, in vivo. FEBS Lett. 280, 311–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vas J., Mattner J., Richardson S., Ndonye R., Gaughan J. P., Howell A., Monestier M. (2008). Regulatory roles for NKT cell ligands in environmentally induced autoimmunity. J. Immunol. 181, 6779–6788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Y., Monestier M. (2003). Inhibitory signal override increases susceptibility to mercury-induced autoimmunity. J. Immunol. 171, 1596–1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]