Abstract

Heart failure is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality and its prevalence continues to rise. Because obesity has been linked with heart failure, the increasing prevalence of obesity may presage further rise in heart failure in the future. Obesity-related factors are estimated to cause 11% of heart failure cases in men and 14% in women. Obesity may result in heart failure by inducing hemodynamic and myocardial changes that lead to cardiac dysfunction, or due to an increased predisposition to other heart failure risk factors. Direct cardiac lipotoxicity has been described where lipid accumulation in the heart results in cardiac dysfunction inexplicable of other heart failure risk factors. In this overview, we discussed various pathophysiological mechanisms that could lead to heart failure in obesity, including the molecular mechanisms underlying cardiac lipotoxicity. We defined the obesity paradox and enumerated various premises for the paradoxical associations observed in the relationship between obesity and heart failure.

Keywords: Obesity, heart failure, mechanisms

Introduction

Heart failure (HF) is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in the United States, and its prevalence continues to rise despite the overall decline in cardiovascular disease (CVD) related morbidity and mortality [1]. The prevalence of HF is 2-3% of the population in industrialized countries [2]. Approximately 5.7 million American adults have HF and require frequent hospitalizations [3]. After a hospital discharge for HF, there is a high risk of rehospitalization or death with 3-month rates of nearly 25% for rehospitalization and 14% for death [2]. Although survival has improved, as shown in the Framingham Heart and Olmsted County Studies, the death rate remains high with approximately 50% of people diagnosed with HF dying within 5 years [3].

The prevalence of obesity is also increasing. The increasing prevalence of obesity affects men and women of all ages, racial and ethnic groups [4]. Adult obesity is associated with excess mortality and morbidity due to development of CVD risk factors, increased incidence of diabetes, CVD events [such as HF], and other health conditions [3]. Obesity-related cardiomyopathy is estimated to cause 11% of HF cases in males and up to 14% in women [5]. The increasing prevalence of obesity especially among younger populations may presage further increase in HF in the future. The aim of this review is to discuss various pathophysiological mechanisms that could lead to HF in the obese state.

Pathophysiological Mechanisms Linking Obesity to Heart Failure

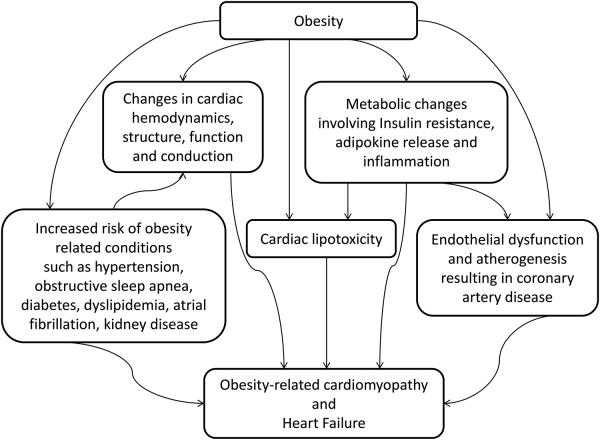

HF in obesity may be due to an increased predisposition to other HF risk factors such as coronary artery disease (CAD), diabetes mellitus, hypertension, dyslipidemia, insulin resistance (IR), metabolic syndrome, kidney disease, obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), and cardiac conduction abnormalities, or occur solely as a result of obesity. When obese individuals develop myocardial dysfunction inexplicable of other causes of HF, they are considered to have “obesity cardiomyopathy” [6]. Our conceptual model of the mechanisms of HF in obesity is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

An illustration of the mechanisms of heart failure in obesity

Changes in cardiac hemodynamics, structure, function and conduction

Hemodynamic changes

The increased metabolic demands resulting from excess adipose tissue and fat-free mass in obesity leads to a hyperdynamic circulation, increased blood volume and cardiac output [7]. The increase in blood volume increases venous return to the right and left ventricles, resulting in increased wall tension and dilatation of these chambers [8]. Heart rate is unchanged or mildly increased but stroke volume increases in proportion to the excess body weight, leading to increases in cardiac work above that predicted for the ideal body weight [9, 10]. The arteriovenous oxygen difference is widened because increased left ventricular (LV) pressure and volume increases oxygen consumption [9, 10] and causes a leftward shift in the Frank-Starling curve [11]. These changes result in hemodynamic overload [12] and increased cardiac stroke work [9] that eventually causes the LV to fail.

LV afterload is increased in obesity due to increases in peripheral vascular resistance and greater aortic stiffness [7, 13], particularly in hypertensive obese individuals. Right ventricular (RV) afterload may also be increased due to LV changes or OSA and/or obesity hypoventilation syndrome (OHS), which leads to hypoxia-induced vasoconstriction and pulmonary hypertension [7, 13, 14].

Alterations in Cardiac Structure

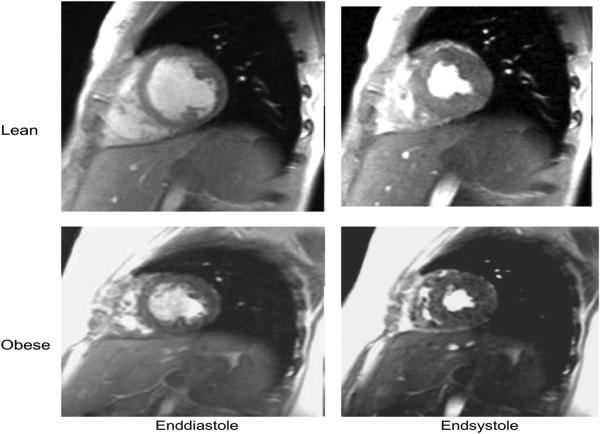

Heart weight and body weight exhibit a linear relationship [6], and long standing obesity especially when accompanied by systemic hypertension is associated with left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) and dilatation, and to a smaller extent, RV hypertrophy and dilatation [9]. Both eccentric and concentric patterns of LVH have been described in obesity [12, 13], and the extent of cardiac remodelling increases with the severity and duration of obesity [13]. A strong positive correlation has been demonstrated between left ventricular mass (LVM) and body mass index (BMI) by Lauer et al, and between LVM and both waist circumference and waist hip ratio by Rasooly et al [9]. Friberg et al. have shown that obese adolescents have a greater LVM than age-matched lean individuals (Figure 2)[15]. Left atrial enlargement may occur from increased circulating blood volume, LVH, increased LV stiffness, and increased LV end diastolic pressures [16]. Excessive epicardial fat is common in obesity and though it may not be strongly related to overall adiposity, epicardial fat mass has a strong relationship with visceral adiposity [6]. Epicardial fat extension into the ventricular and atrial myocardium may result in fatty infiltration, which is most commonly seen in the RV, perivascular regions and cardiac skeleton [9].

Figure 2.

Magnetic resonance images at end-diastole and end-systole in one lean and one obese subject, respectively (reproduced with permission from oxford university press) [15].

There is an increase in the prevalence of myocardial fibrosis in obesity that is proportional to the extent of obesity and usually accompanied by tissue degeneration and inflammation [6]. Myocardial fibrosis is an important structural alteration in the development of LVH, and also contributes to cardiac dysfunction [17, 18]. LVH involves changes in myocardial tissue architecture consisting of peri-vacuolar and myocardial fibrosis, medial thickening of intramyocardial coronary arteries and myocyte hypertrophy [17]. Although increased afterload (commonly from elevated blood pressure) is the initiating stimulus, neurohormonal factors such as sympathetic nervous system (SNS) activation and the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) are important in the development of LVH in obese persons [12, 17]. The development of LVH in obese individuals is also potentiated by the trophic effects of fat secreted hormones such as leptin [12, 19] or a training effect on the heart because of the extreme amount of body weight that has to be lifted during normal activities [12].

Diastolic and systolic cardiac function

Obesity adversely affects diastolic cardiac function [13, 20] and the changes in LV filling indices seen in obesity may be due to altered loading conditions, and/or an increased LVM that reduces ventricular compliance [13]. Obese individuals commonly have a decreased E/A ratio (early [E] to late or atrial [A] diastolic filling velocity) [6, 20-22] and prolonged isovolumetric relaxation times on 2-dimensional echocardiography [6, 20, 21]. Reductions in mitral annular velocity and myocardial early diastolic velocity have also been demonstrated on tissue doppler echocardiography in obese persons [6].

Impairment of ventricular systolic function is not consistently present in obese persons [9, 23], and myocardial fat infiltration even when present does not predispose to LV dysfunction [9]. However, obese individuals may fail to increase their ejection fraction with exercise [7, 13], and newer echocardiographic techniques (tissue doppler and strain imaging) have identified subclinical depression of LV systolic function in obese individuals [6, 12, 20].

Cardiac arrhythmia and conduction system abnormalities

Obesity affects the cardiac conduction system [6, 11] and even in the absence of LV dysfunction, there is a significant increase in the incidence of arrhythmias in obese persons [11, 16]. Obesity is linked to the cardiac autonomic system [11], and may result in abnormalities in the sympathovagal balance [11, 16]. Increased plasma catecholamine levels in obese persons may directly decrease the threshold for arrhythmias or lead to elevated free fatty acid (FFA) levels, that may affect cardiac repolarization [11]. High glucose concentrations (frequently seen in obesity) may increase ventricular irritability by causing an increase in vasomotor tone and a decrease in nitric oxide (NO) availability [11]. The anatomical cardiac changes seen in obesity result in physiological alterations such as disturbances of myocardial blood flow and development of an arrhythmogenic myocardial substrate [17]. Specifically, there is a 3-8% higher risk of developing new onset atrial fibrillation (AF) independent of other CVD risk factors with each unit increase in BMI [24, 25].

Metaplastic and infiltrative changes involving the sinus node, atrioventricular node, right bundle branch and myocardium adjacent to the atrioventricular ring may also lead to cardiac conduction abnormalities [9, 11]. These changes occur when cords of cells (which sometimes arise from epicardial fat) slowly accumulate fat between cardiac muscle fibers or lead to cardiac muscle degeneration [11]. Abnormalities in cardiac conduction and arrhythmias such as AF [11] increase the risk of developing HF. AF for instance may result in HF by causing a tachycardia-induced cardiomyopathy [26] through multiple mechanisms such as uncontrolled heart rate, loss of atrioventricular synchrony, irregularity in the ventricular rhythm, valvular regurgitation, and neurohormonal effects [27].

Endothelial dysfunction and vascular changes

Endothelial dysfunction and inflammation of the vessel wall is an important event in the development of atherosclerosis, and obesity directly contributes to atherogenesis by creating a prothrombotic and pro-inflammatory state [28]. Obesity is an independent risk factor for atherosclerosis [11, 16, 28]. In the Pathobiological Determinants of Atherosclerosis in Youth study it was shown that obesity in young adults accelerated the progression of atherosclerosis decades before the appearance of clinical manifestations [28]. Excess circulating lipids including triglycerides, non-esterified fatty acids, and low density lipoprotein-cholesterol causes lipotoxicity which damages vascular tissues and their functions [29]. Lipotoxicity acts independently and synergistically with hyperglycemia, oxidative stress, an upregulated RAAS and increased pro-inflammatory cytokines to cause endothelial dysfunction in obesity [30]. This process involves a decrease in endothelial NO synthase gene expression and catalytic activity, which leads to reduced NO bioavailability [30].

Obesity increases the risk of hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, IR, metabolic syndrome, OSA, and kidney disease [11, 13, 16, 28, 31-33], all of which are risk factors for CAD, a predisposing factor for HF [13]. In addition to increasing the risk of atherogenesis, these conditions can directly increase the risk of HF [13]. The complexity in these relationships is obvious because obesity, hypertension and nocturnal hypoxemia (commonly seen in OSA) are predictors of LVH [12], another potent risk factor for HF [17], and CAD also plays a role in the development of LVH [18].

Changes in lung mechanics and function

OSA and OHS are co-morbidities frequently seen in obesity that may contribute to cardiac disease [6]. Alveolar hypoventilation and ventilation-perfusion mismatch occur in obesity due to an increased demand for ventilation and breathing workload, respiratory muscle inefficiency, decreased functional reserve capacity and expiratory reserve volume, and closure of the peripheral lung units [11]. Pulmonary hypertension develops as a result of hypoxia induced vasoconstriction [11, 34] and leads to RV failure.

The precise mechanisms by which OSA results in LV failure are unclear [11]. OSA has been proposed to contribute to LVH (a precursor of LV failure) because of increased heart rate, blood pressure, sympathetic tone, intermittent hypoxia, and large negative intrathoracic pressure changes during periods of airway obstruction [12, 35]. OSA may also contribute to HF indirectly by increasing the risk of arrhythmias such as AF [6, 16, 35], hypertension [6, 11, 16, 35], CAD (and myocardial infarction) [11, 16, 35], possibly through pathways linked to oxidative stress, endothelial dysfunction, and inflammation [35].

Metabolic changes

Insulin resistance

IR predicts HF incidence independent of established risk factors [36]. Obesity is highly correlated with IR states [37], which may potentiate the link between obesity and HF [38]. IR leads to alterations in myocardial substrate metabolism by decreasing glucose utilization and increasing FFA oxidation [37, 39-41]. Increased fatty acid oxidation causes increased myocardial oxygen consumption due to uncoupling of oxidative phosphorylation, inhibition of membrane bound adenosine triphosphatase (ATPase), ceramide production and generation of reactive oxygen species [40, 42]. The resulting decrease in oxidative capacity impairs cardiac efficiency and contractility by causing changes in sarcoplasmic reticular calcium stores, and promoting mitochondrial dysfunction [37, 41].

The metabolic adaptation in myocardial IR is mediated by alterations in myocyte gene expression, and though initially compensatory, results in further impairment of insulin signaling and metabolic flexibility [37, 40-42]. Because ATP generation is necessary for cardiac work [43], IR ultimately leads to cardiac dysfunction and increases susceptibility to pressure overload and ischemic injury [39]. Increased cardiac work (as seen in HF states) further stimulates myocardial metabolism [42] and sets up a vicious cycle.

By stimulating global IR, obesity leads to hyperinsulinemia and chronic systemic hyperglycemia which results in hyperglycemia-induced cellular injury or glucotoxicity [37]. Glucotoxicty causes cardiac injury through direct and indirect effects on cardiac myocytes, fibroblasts, endothelial cells and overproduction of reactive oxygen species which induces apoptosis [37]. Hyperglycemia also contributes to altered cardiac structure and function by the creation of advanced glycation end-products and posttranslational modification of extracellular matrix proteins which leads to altered expression/function of intramyocellular calcium channels [37]. These processes contribute to systolic and diastolic cardiac dysfunction [37].

Hyperinsulinemia also increases hepatic production of angiotensinogen, a precursor of angiotensin II [34, 40]. Angiotensin II is a growth factor for cardiac myocytes and results in cellular proliferation, hypertrophy, apoptosis, fibrosis and myocardial dysfunction [34, 40]. RAAS is activated early in HF causing volume overload and further myocardial damage [40]. Both IR and stimulation of RAAS activates the SNS [34, 40]. This causes a progressive loss of cardiac myocytes, further myocardial dysfunction, impairment of signaling transduction of β-adrenergic receptors and down-regulation of sarcoplasmic reticular calcium ATPase, a cardiac inotropic protein [34].

Inflammation

Obesity is characterized by a state of chronic inflammation, with raised circulating levels of inflammatory markers, and increased expression and release of inflammation-related adipokines (except adiponectin) [44]. Adipokines, including leptin, adiponectin, resistin, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin-1β, interleukin-6, monocyte chemotactic protein-1, macrophage migration inhibitory factor, nerve growth factor, vascular endothelial growth factor, plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 and haptoglobin, are linked to inflammation and the inflammatory response [44, 45]. The production of the inflammatory marker, C-reactive peptide by the liver is modulated by interleukin-6 [11]. Previous studies have shown that interleukin-6, interleukin-2, C-reactive peptide and tumor necrosis factor-α are associated with HF and subclinical LV dysfunction [46]. In the Multi-Ethnic study of Atherosclerosis, the association between obesity and HF was related to inflammatory pathways, and interleukin-6 had the strongest prediction for incident HF [46]. FFA in the interstitium of epicardial adipose tissue contributes to obesity-related inflammation by activation of inflammatory responses in epicardial macrophages [47]. Persistent inflammation promotes IR [40] and contributes to fibrotic changes in the heart [34] which promotes cardiac dysfunction. The accumulation of inflammatory mediators from epicardial and visceral adipose tissue promotes the development of LVH which leads to HF [37]. Epicardial FFA also promote cardiac impairment through their adverse paracrine role in promoting cardiac arrhythmias and lipotoxic cardiomyopathy [47].

Adipokines

The cardiovascular effects of adipokines include direct actions on target tissues and effects occurring as a result of central stimulation of the SNS [19]. Adipokines play a regulatory role in myocardial function through their involvement in myocardial metabolism, myocyte hypertrophy, cell death, and changes in the structure and composition of the extracellular matrix [48]. The direct regulation of myocardial remodelling components (matrix metalloproteins, tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases and collagens) by adipokines has been demonstrated in in-vitro and in-vivo studies [48].

Adiponectin and leptin have been implicated in heart disease and myocardial remodelling [19, 48]. Adiponectin levels are reduced in obese people while leptin levels are positively related with BMI and adiposity [19]. Adiponectin regulates cardiac injury by modulating antiinflammatory and prosurvival reactions, and inhibiting cardiac remodelling [49, 50]. The effects of adiponectin are mediated via its potentiation of insulin action, increase in NO production, stimulation of prostaglandin synthesis via inducible cycloxygenase-2, and activation of adenosine monophosphate, which also activates protein kinase and inhibits α-adrenergic-receptor-stimulated hypertrophy of cardiac myocytes [19, 40, 50]. Adiponectin modulates tissue ceramide levels by activating ceramidase which hydrolyses ceramide[30, 51].

Leptin stimulates cardiac hypertrophy directly through complex cell signalling mechanisms and indirectly through its effects on hypertension and the SNS [19, 50, 52]. Leptin exerts cardioprotective effects directly against ischemic-reperfusion injury [19, 50, 53] and indirectly by producing a signal which limits cardiac lipotoxicity [19]. Leptin also has a negative inotropic effect on cardiomyocytes through endogenous production of NO [19]. The effects of leptin are mediated by leptin binding to its receptors and subsequent activation of various kinases in cardiomyocytes [19]. Because leptin and adiponectin appear to have opposite effects, it is speculated that the leptin/adiponectin ratio may play a role in myocardial remodelling and heart failure development [19].

Resistin, an adipokine involved in inflammation and IR has also been associated with the development of HF after accounting for obesity, IR, and coronary heart disease [38, 54] The precise role of resistin in cardiac pathology and ischemic-reperfusion injury is yet to be defined, although, resistin has been linked to IR and dyslipidemia, and shown to inhibit vesicular transport of glucose [19, 50]. The cardiac effects of other adipokines such as apelin, visfatin, vastin, omentin and chemerin are less extensively studied [19].

Cardiac lipotoxicity

Adiposity promotes ectopic deposition of triglyceride in the heart, by a process called cardiac steatosis [55]. Lipid accumulation occurs due to high plasma FFAs and triglyceride levels or due to defects in lipid oxidation [56]. In humans, cardiac steatosis increases progressively with BMI and the extent of adiposity [55, 57], and is accompanied by elevated LVM and suppressed septal wall thickening on cardiac imaging [55, 58]. Myocardial triglyceride by itself is non-toxic, and may initially act as a buffer by diverting FFAs from toxic pathways [56]. Cardiomyocytes have limited storage capacity and excess FFAs are shunted into non-oxidative pathways that result in lipotoxicity [11, 56, 59], and apoptosis of lipid-filled cardiomyocytes [11]. Intervening fat may also cause pressure-induced atrophy of adjacent myocardial cells and lead to a restrictive pattern of cardiomyopathy [11].

Molecular mechanisms underlying cardiac lipotoxicity

The proposed mechanisms underlying cardiac lipotoxicity are complex and interlinked [29]. Several lipids have been implicated including fatty acids (particularly saturated long chain fatty acids like palmitic acid) and fatty acid coenzyme-A, acylcarnithine, unesterified cholesterol, lysolecithin, ceramide and diacylglycerol [29, 41]. Collectively, these lipids cause defective intracellular signalling, create oxidative stress, promote inflammation, induce mitochondrial dysfunction and endoplasmic reticulum stress, activate apoptosis, and lead to abnormal myofibrillar function [41, 51, 58, 60]. The concept of cardiac lipotoxicity has been demonstrated in several transgenic animal models [41, 45, 51, 58, 60, 61]. In these models, Park et al. showed that increased myocardial ceramide production from excess fatty acids was associated with diastolic dysfunction, but, improvement in cardiac dysfunction was achieved by pharmacologic and genetic interventions that resulted in reduction of myocardial ceramide [51, 60].

Obesity paradox

Various obesity paradoxes have been described when increased body fat does not increase morbidity or mortality [37, 62]. In HF, this paradoxical association has mostly been described with short and long-term survival after the development of HF [63]. However, paradoxical relationships between BMI and HF incidence have been reported among Hispanic males in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis [64]. It has been suggested that the obesity paradox may be artifactual and resulting from residual statistical confounding, comorbidities, differences in treatments/management strategies by BMI groups, survival bias, lead time bias, and diagnostic bias [37]. Current evidence however adduces that it is a real biological phenomenon [37]. This concept has been described with BMI, a measure of generalized obesity and waist circumference, a measure of central obesity in both genders [65, 66].

Multiple explanations have been proposed for the obesity paradox [65-68]. HF is a catabolic state, and cachexia implies a poorer prognosis [65]. Obese individuals have greater muscle mass and metabolic reserve [66, 67]. Cytokines (including adipokines) [19] and neuroendocrine profiles in obese HF patients may be cardioprotective [67]. Obesity is associated with decreased catecholamine response [65], and production of stable TNF-α receptors which could also be protective [67]. Higher circulating serum lipoproteins in obesity may have antiinflammatory effects by binding and neutralizing circulating bacterial endotoxins and cytokines [65, 67]. Obese patients have lower brain natriuretic peptide(BNP) levels [67] and BNP is prognostic marker in patients with CVD and HF [69-71].

Conclusion

The rising prevalence of obesity increases the number of individuals at subsequent risk of developing HF. Obesity may result in HF by inducing changes in cardiac hemodynamics, structure, function and conduction, promoting endothelial dysfunction and vascular changes, contributing to metabolic derangements involving IR, secretion of adipokines and inflammatory markers, and cardiac lipotoxicity, or by increasing the risk of other HF risk factors such as OSA/OHS. An understanding of these mechanisms is necessary for effective HF prevention. Comprehension of the paradoxical associations between obesity and HF is necessary for the development of weight loss guidelines for HF management.

Acknowledgments

T32 training grant on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research in Cardiovascular Disease and Stroke was supported by grant 5 T32 HL087730-03 from the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Bahrami H, Kronmal R, Bluemke DA, Olson J, Shea S, Liu K, Burke GL, Lima JA. Differences in the Incidence of Congestive Heart Failure by Ethnicity. The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(19):2138–45. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.19.2138. [PMID: 18955644] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Braunschweig F, Cowie MR, Auricchio A. What are the costs of heart failure? Europace. 2011;13(Suppl 2):ii13–ii17. doi: 10.1093/europace/eur081. [PMID: 21518742] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, Adams RJ, Berry JD, Brown TM, Carnethon MR, Dai S, de Simone G, Ford ES, Fox CS, Fullerton HJ, Gillespie C, Greenlund KJ, Hailpern SM, Heit JA, Ho PM, Howard VJ, Kissela BM, Kittner SJ, Lackland DT, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Makuc DM, Marcus GM, Marelli A, Matchar DB, McDermott MM, Meigs JB, Moy CS, Mozaffarian D, Mussolino ME, Nichol G, Paynter NP, Rosamond WD, Sorlie PD, Stafford RS, Turan TN, Turner MB, Wong ND, Wylie-Rosett J, American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2011 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;123(4):e18–209. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182009701. [PMID: 21160056] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baskin ML, Ard J, Franklin F, Allison DB. Prevalence of Obesity in the United States. Obesity reviews. 2005;6(1):5–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2005.00165.x. [PMID: 156555032] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glenn DJ, Wang F, Nishimoto M, Cruz MC, Uchida Y, Holleran WM, Zhang Y, Yeghiazarians Y, Gardner DG. A Murine Model of Isolated Cardiac Steatosis Leads to Cardiomyopathy. Hypertension. 2011;57(2):216–22. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.160655. [PMID: 21220706] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ashrafian H, le Roux CW, Darzi A, Athanasiou T. Effects of Bariatric Surgery on Cardiovascular Function. Circulation. 2008;118(20):2091–102. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.721027. [PMID: 19001033] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vasan RS. Cardiac Function and Obesity. Heart. 2003;89(10):1127–9. doi: 10.1136/heart.89.10.1127. [PMID: 12975393] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Poirier P, Giles TD, Bray GA, Hong Y, Stern JS, Pi-Sunyer FX, Eckel RH. Obesity and Cardiovascular Disease. Pathophysiology, Evaluation and Effect of Weight Loss. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26(5):968–76. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000216787.85457.f3. [PMID: 16627822] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alpert MA. Obesity Cardiomyopathy: Pathophysiology and Evolution of the Clinical Syndrome. Am J Med Sci. 2001;321(4):225–36. doi: 10.1097/00000441-200104000-00003. [PMID: 11307864] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alpert MA, Fraley MA, Birchem JA, Senkottaiyan N. Management of Obesity Cardiomyopathy. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2005;3(2):225–30. doi: 10.1586/14779072.3.2.225. [PMID: 15853596] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Poirier P, Giles TD, Bray GA, Hong Y, Stern JS, Pi-Sunyer FX, Eckel RH, American Heart Association. Obesity Committee of the Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism Obesity and Cardiovascular Disease: Pathophysiology, Evaluation, and Effect of Weight Loss: An Update of the 1997 American Heart Association Scientific Statement on Obesity and Heart Disease From the Obesity Committee of the Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism. Circulation. 2006;113(6):898–918. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.171016. [PMID: 16380542] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Avelar E, Cloward TV, Walker JM, Farney RJ, Strong M, Pendleton RC, Segerson N, Adams TD, Gress RE, Hunt SC, Litwin SE. Left Ventricular Hypertrophy in Severe Obesity. Interactions Among Blood Pressure, Nocturnal Hypoxemia, and Body Mass. Hypertension. 2007;49(1):34–9. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000251711.92482.14. [PMID: 17130310] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kenchaiah S, Gaziano JM, Vasan RS. Impact of obesity on the risk of heart failure and survival after the onset of heart failure. Med Clin N Am. 2004;88(5):1273–94. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2004.04.011. [PMID: 15331317] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eckel RH. Obesity and Heart Disease. A Statement for Healthcare Proffessionals From the Nutrition Committee, American Heart Association. Circulation. 1997;96(9):3248–50. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.9.3248. [PMID: 9386201] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Friberg P, Allansdotter-Johnsson A, Ambring A, Ahl R, Arheden H, Framme J, Johansson D, Holmgren H, Wahlander H, Marild S. Increased left ventricular mass in obese adolescents. Eur Heart J. 2004;25(11):987–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ehj.2004.03.018. [PMID: 15172471] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lavie CJ, Milani RV, Ventura HO. Obesity and Cardiovascular Disease. Risk Factor, Paradox and Impact of Weight loss. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53(21):1925–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.12.068. [PMID: 19460605] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gradman AH, Alfayoumi F. From Left Ventricular Hypertrophy to Congestive Heart Failure: Management of Hypertensive Heart Disease. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2006;48(5):326–41. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2006.02.001. [PMID: 16627048] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bauml MA, Underwood DA. Left ventricular hypertrophy: An overlooked cardiovascular risk factor. Clev Clin J Med. 2010;77(6):381–7. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.77a.09158. [PMID: 20516249] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karmazyn M, Purdham DM, Rajapurohitam V, Zeidan A. Signalling mechanisms underlying the metabolic and other effects of adipokines on the heart. Cardiovasc Res. 2008;79(2):279–86. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvn115. [PMID: 18474523] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wong CY, O’Moore-Sullivan T, Leano R, Byrne N, Beller E, Marwick TH. Alterations of Left Ventricular Myocardial Characteristics Associated With Obesity. Circulation. 2004;110(19):3081–87. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000147184.13872.0F. [PMID: 15520317] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berkalp B, Cesur V, Corapcioglu D, Erol C, Baskal N. Obesity and left ventricular diastolic dysfunction. Int J Cardiol. 1995;52(1):23–6. doi: 10.1016/0167-5273(95)02431-u. [PMID: 8707431] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Russo C, Jin Z, Homma S, Rundek T, Elkind MS, Sacco RI, Di tullio MR. Effect of Obesity and Overweight on Left Ventricular Diastolic Function: A community-based study in an elderly cohort. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57(12):1368–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.10.042. [PMID: 16490446] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dorbala S, Crugnale S, Yang D, Di Carli MF. Effect of Body Mass Index on Left Ventricular Cavity Size and Ejection Fraction. Am J Cardiol. 2006;97(5):725–29. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.09.122. [PMID: 16490446] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schoonderwoerd BA, Smit MD, Pen L, Van Gelder IC. New risk factors for atrial fibrillation: causes of ‘not-so-lone atrial fibrillation’. Europace. 2008;10(6):668–73. doi: 10.1093/europace/eun124. [PMID: 18480076] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Asghar O, Alam U, Hayat SA, Aghamohammadzadeh R, Heagerty AM, Malik RA. Obesity, Diabetes and Atrial Fibrillation; Epidemiology, Mechanisms and Interventions. Curr Cardiol Rev. 2012;8(4):253–64. doi: 10.2174/157340312803760749. [PMID: 22920475] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Piot O. Atrial fibrillation and heart failure: a dangerous criminal conspiracy. Annales de Cardiologie et d’Angeiologie. 2009;58(Suppl 1):S14–S16. doi: 10.1016/S0003-3928(09)73391-8. [PMID: 20103171] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Scardi S, Mazzone C. Atrial fibrillation and heart failure: cause or effect? Ital Heart J Suppl. 2002;3(9):899–907. [PMID: 12407857] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Poirier P, Despres J-P. Waist Circumference, Visceral Obesity, and Cardiovascular Risk. J Cardiopulm Rehabil. 2003;23(3):161–9. doi: 10.1097/00008483-200305000-00001. [PMID: 12782898] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim JA, Montagnani M, Chandrasekran S, Quon MJ. Role of Lipotoxicity in Endothelial Dysfunction. Heart Fail Clin. 2012;8(4):589–607. doi: 10.1016/j.hfc.2012.06.012. [PMID: 22999242] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Symons JD, Abel ED. Lipotoxicity contributes to endothelial dysfunction: A focus on the contribution from ceramide. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2013;14(1):59–68. doi: 10.1007/s11154-012-9235-3. [PMID: 23292334] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Russell GV, Pierce CW, Nunley L. Financial Implications of Obesity. Orthop Clin N Am. 2011;42(1):123–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2010.09.003. [PMID: 21095441] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hammond RA, Levine R. The economic impact of obesity in the United States. Diabetes, Metab Syndr Obes. 2010;3:285–95. doi: 10.2147/DMSOTT.S7384. [PMID: 21437097] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang Y, Chen X, Song Y, Caballero B, Cheskin LJ. Association between obesity and kidney disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Kidney Int. 2008;73(1):19–33. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002586. [PMID: 17928825] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dela Cruz CS, Matthay RA. Role of Obesity in Cardiomyopathy and Pulmonary Hypertension. Clin Chest Med. 2009;30(3):509–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2009.06.001. [PMID: 19700049] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baguet J-P, Barone-Rochette G, Tamisier R, Levy P, Pepin JL. Mechanisms of cardiac dysfunction in obstructive sleep apnea. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2012;9(12):679–88. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2012.141. [PMID: 23007221] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ingelsson E, Sundstrom J, Arnlov J, Zethelius B, Lind L. Insulin Resistance and Risk of Congestive Heart Failure. JAMA. 2005;294(3):334–41. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.3.334. [PMID: 16030278] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Turer AT, Hill JA, Elmquist JK, Scherer PE. Adipose Tissue Biology and Cardiomyopathy. Translational Implications. Circ Res. 2012;111(12):1565–77. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.262493. [PMID: 23223931] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Horwich TB, Fonarow GC. Glucose, Obesity, Metabolic Syndrome, and Diabetes relevance to Incidence of Heart Failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55(4):283–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.07.029. [PMID: 20117431] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Voulgari C, Tentolouris N, Dilaveris P, Tousoulis D, Katsilambros N, Stefanadis C. Increased Heart Failure Risk in Normal-Weight People With Metabolic Syndrome Compared With Metabolically Healthy Obese Individuals. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58(13):1343–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.04.047. [PMID: 21920263] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wong C, Marwick TH. Obesity cardiomyopathy: pathogenesis and pathophysiology. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med. 2007;4(8):436–43. doi: 10.1038/ncpcardio0943. [PMID: 17653116] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Drosatos K, Schulze PC. Cardiac Lipotoxicity: Molecular Pathways and Therapeutic Implications. Curr Heart Fail Rep. 2013;10(2):109–21. doi: 10.1007/s11897-013-0133-0. [PMID: 2350876] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Banerjeee S, Peterson LR. Myocardial Metabolism and Cardiac Performance in Obesity and Insulin Resistance. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2007;9(2):143–9. doi: 10.1007/BF02938341. [PMID: 17430682] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Peterson LR. Obesity and Insulin Resistance: Effects on Cardiac Structure, Function, and Substrate Metabolism. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2006;8(6):451–6. doi: 10.1007/s11906-006-0022-y. [PMID: 17087855] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Trayhurn P, Wood IS. Signalling role of adipose tissue: adipokines and inflammation in obesity. Biochem Soc Trans. 2005;33(Pt 5):1078–81. doi: 10.1042/BST0331078. [PMID: 23761785] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kang SC, Kim BR, Lee SY, Park TS. Sphingolipid metabolism and obesity-induced inflammation. Front Endocrinol. 2013;4:67. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2013.00067. [PMID: 23761785] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bahrami H, Bluemke DA, Kronmal R, Bertoni AG, Lloyd-Jones DM, Shahar E, Szklo M, Lima JA. Novel Metabolic Risk Factors for Incident Heart Failure and Their Relationship With Obesity. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51(18):1775–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.12.048. [PMID: 18452784] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sacks HS, Fain JN. Human epicardial fat: wht is new and what is missing? Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2011;38(12):879–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2011.05601.x. [PMID: 21895738] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schram K, Sweeney G. Implications of Myocardial Matrix Remodeling by Adipokines in Obesity-Related Heart Failure. Cardiovasc Med. 2008;18(6):199–205. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2008.10.001. [PMID: 19185809] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ouchi N, Shibata R, Walsh K. Cardioprotectio by Adiponectin. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2006;16(5):141–6. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2006.03.001. [PMID: 16781946] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Smith CCT, Yellon DM. Adipocytokines, cardiovascular pathophysiology and myocardial protection. Pharmacol Ther. 2011;129(2):206–19. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2010.09.003. [PMID: 20920528] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Park TS, Goldberg IJ. Sphingolipids, Lipotoxic Cardiomyopathy, and Cardiac Failure. Heart Failure Clin. 2012;8(4):633–41. doi: 10.1016/j.hfc.2012.06.003. [PMID: 22999245] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Karmazyn M, Purdham DM, Rajapurohitam V, Zeidan A. Leptin as a Cardiac Hypertrophic Factor: A Potential Target for Therapeutics. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2007;17(6):206–11. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2007.06.001. [PMID: 17662916] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Smith CC, Mocanu MM, Davidson SM, Wynne AM, Simpkin JC, Yellon DM. Leptin, the obesity-associated hormone, exhibits direct cardioprotective effects. Br J Pharmacol. 2006;149(1):5–13. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706834. [PMID: 16847434] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Frankel DS, Vasan RS, D’Agostino RB, Sr, Benjamin EJ, Levy D, Wang TJ, Meigs JB. Resistin, Adiponectin and Risk of Heart Failure. The Framingham Offspring Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53(9):754–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.07.073. [PMID: 19245965] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Szczepaniak LS, Dobbins RL, Metzger GJ, Sartoni-D’Ambrosia G, Arbique D, Vongpatanasin W, Unger R, Victor RG. Myocardial Triglycerides and Systolic Function in Humans: In Vivo Evaluation by Localized Proton Spectroscopy and Cardiac Imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2003;49(3):417–23. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10372. [PMID: 12594743] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ebong IA, Goff DC, Rodriguez CJ, Chen H, Sibley CT, Bertoni AG. Association of Lipids with Incident Heart Failure among adults with and without Diabetes Mellitus. Multiethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Circ Heart Fail. 2013;6(3):371–8. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.112.000093. [PMID: 23529112] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McGavock JM, Victor RJ, Unger RH, Szczepaniak, American College of Physicians and Ameican Physiological Society Adiposity of the Heart*, Revisited. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(7):517–24. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-7-200604040-00011. [PMID: 16585666] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wende AR, Abel ED. Lipotoxicity in the heart. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2009;1801(3):311–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2009.09.023. [PMID: 19818871] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Schaffer JE. Lipotoxicity: when tissues overeat. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2003;14(3):281–7. doi: 10.1097/00041433-200306000-00008. [PMID: 12840659] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Park TS, Hu Y, Noh HL, Drosatos K, Okajima K, Buchanan J, Tuinei J, Homma S, Jiang XC, Abel ED, Goldberg IJ. Ceramide is a cardiotoxin in lipotoxic cardiomyopathy. J Lipid Res. 2008;49(10):2101–12. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M800147-JLR200. [PMID: 18515784] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Baranowski M, Gorski J. Heart Sphingolipids in Health and Disease. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2011;721:41–56. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-0650-1_3. [PMID: 21910081] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bays HE. Adisopathy: Is “Sick Fat” a Cardiovascular Disease? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57(25):2461–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.02.038. [PMID: 21679848] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zamora E, Lupon J, de Antonio M, Urrutia A, Coll R, Diez C, Altimir S, Bayes-Genis A. The obesity paradox in heart failure: Is etiology a key factor? Int J Cardiol. 2013;166(3):601–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2011.11.022. [PMID: 22204855] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ebong IA, Goff DC, Rodriguez CJ, Chen H, Bluemke DA, Szklo M, Bertoni AG. The Relationship Between Measures of Obesity and Incident Heart Failure: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Obesity. 2013;21(9):1915–22. doi: 10.1002/oby.20298. [PMID: 23441088] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Clark AL, Chyu J, Horwich TB. The Obesity Paradox in Men versus Women with Systolic Heart Failure. Am J Cardiol. 2012;110(1):77–82. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.02.050. [PMID: 22497678] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Clark AL, Fonarow GC, Horwich TB. Waist Circumference, Body Mass Index and Survival in Systolic Heart Failure: The Obesity Paradox Revisited. J Cardiac Fail. 2011;17(5):374–80. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2011.01.009. [PMID: 21549293] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lavie CJ, Milani RV, Ventura HO, Romero-Corral A. Body Composition and Heart Failure Prevalence and Prognosis: Getting to the Fat of the Matter in “Obesity Paradox”. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85(7):605–8. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2010.0333. [PMID: 20592168] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Soeters PB, Sobotka L. The pathophysiology underlying the obesity paradox. Nutrition. 2012;28(6):613–5. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2011.10.010. [PMID: 22222294] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Linssen GC, Bakker SJ, Voors AA, Gansevoort RT, Hillege HL, de Jong PE, van Veldhuisen DJ, Gans RO, de Zeeuw N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide is an independent predictor of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in the general population. Eur Heart J. 2010;31(1):120–7. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp420. [PMID: 19854731] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Palazzuoli A, Gallota M, Quatrini I, Nuti R. Natriuretic peptides (BNP and NT-proBNP): measurement and relevance in heart failure. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2010;6:411–8. doi: 10.2147/vhrm.s5789. [PMID: 20539843] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bertoni AG, Wagenknecht LE, Kitzman DW, Marcovina SM, Rushing JT, Espeland MA, brain Natriuretic Peptide Subgroup of the Look Ahead Research Group Impact of the Look AHEAD intervention on NT-pro Brain Natriuretic Peptide in overweight and obese adults with diabetes. Obesity. 2012;20(7):1511–8. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.296. [PMID: 21959345] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]