Abstract

Limited data exist regarding attitudes and acceptability of topical and oral HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) among US black women. This investigation explored interest in HIV chemoprophylaxis and modes of use. Five focus groups enrolled 26 black women recruited from an inner-city community health center and affiliated HIV testing sites. Thematic analysis utilized Atlas.ti. Most women expressed interest in PrEP, as many reported condom failure concerns. Most women preferred a pill formulation to intravaginal gel because of greater perceived privacy and concerns about vaginal side effects and gel leakage. Women who had taken pills previously advocated daily dosing and indicated adherence concerns about episodic or post-coital PrEP. Many women desired prophylactic strategies that included partner testing. Urban black women are interested in utilizing PrEP; however, misgivings exist about gel inconvenience and potential side effects for themselves and their partners. Most women preferred oral PrEP, dosed daily.

Introduction

Dramatic health care disparities exist in the US HIV epidemic in which black women, who comprise 14% of the total number of women in the US, account for 66% of incident HIV infections among US women.1 As of 2009, HIV was the third leading cause of death among black women between the ages of 35 and 44.2,3 The high prevalence of HIV in the sexual networks of black women4 increases their risk for acquiring HIV, even when they are monogamous or have limited numbers of partners.5 Influential factors among women of color unaware of their HIV status that limit self-protective behaviors include autonomy loss, powerlessness, particularly in the context of rape or partner infidelity, as well as a need for increased health related knowledge.6 Structural factors such as poor access to health care, unstable housing, and limited HIV prevention education may contribute to increased prevalence of HIV,4 as do the increased prevalence of other sexually transmitted infections and alcohol and drug use.7

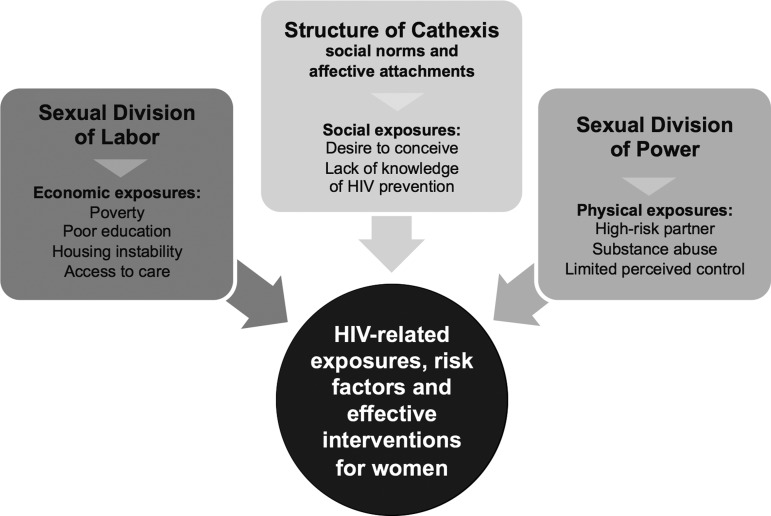

The Theory of Gender and Power (TGP) (Fig. 1) is a theoretical model that has been used to examine HIV-related exposures, risk factors, and effective preventive interventions for women.7,8 This model describes three structures: (1) the sexual division of labor manifest as economic exposures such as poverty, poor access to health insurance, being uninsured or underinsured, and being unemployed or having a high demand, low control work environment; (2) the sexual division of power manifest as physical exposures, such as having a partner or partners at high risk of HIV acquisition, history of substance abuse, and limited perceived control; and (3) the structure of cathexis, which refers to social norms and affective attachments, manifest as social exposures such as desire to conceive, and lack of knowledge of HIV prevention.

FIG. 1.

Theoretical model: Theory of Gender and Power.

Current US HIV prevention strategies for black women include culturally tailored health messages and behavioral strategies that attempt to reduce stigma, promote HIV testing, facilitate linkage to HIV care and treatment, and increase the use of condoms and sterile syringes.9 For heterosexual women, barriers to condom use include fear of perceived unfaithfulness,10 financial barriers,10 personal perception of being low-risk,11 educational status,12 and desire to conceive.12 Women subjected to intimate partner violence13 or who experience high partner-related barriers to condom use are also more likely to report risky sexual behaviors.13 Therefore, additional prevention strategies are needed for black women who may not be able to negotiate condom use.

The use of antiretroviral medications by at-risk persons, either orally or as a topical vaginal microbicide, is a novel HIV prevention strategy known as pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). In the CAPRISA 004 trial, high-risk women assigned to use a pericoital intravaginal gel containing 1% tenofovir had a 39% decrease in new HIV infections compared to women randomized to use a placebo gel.14 Clinical trials of oral PrEP among women have shown varying results: two trials demonstrated 49–68% efficacy,15,16 whereas two others did not demonstrate efficacy.17–19 Ongoing investigations suggest that adherence is strongly correlated with prophylactic effectiveness.20 Further exploration will clarify the biomedical and behavioral correlates of PrEP effectiveness for at-risk women, and acceptability should be a key component of that investigation.

Although studies have assessed PrEP acceptability among men who have sex with men,21,22 men and women in international settings,23–26 and high risk heterosexuals in the US,27,28 there is a critical need to understand PrEP acceptability and product preferences among US black women,29–32 given the high HIV incidence in this population. A national survey of adult women in the US found that African American women were more likely than white women to consider using oral PrEP and that cost, peer perspectives, and physician input would influence their decision making.32 This qualitative study explores the factors that influence PrEP acceptability and preferences for oral or vaginal administration of PrEP among a sample of urban black women in Boston.

Methods

Focus group methodology

The qualitative investigation included five focus groups comprised of a total of 26 English-speaking black women between the ages of 18 and 50 recruited from the Dimock Community Health Center, an inner-city primary care facility in Boston, Massachusetts, and its affiliated HIV testing sites. The HIV testing sites afforded access to a community-based sample of women who might not be in care. Potential participants responded to a recruitment flyer posted in waiting rooms at the health center and at 15 affiliated off-site HIV testing locations. Eligible subjects self-identified as female, of black race, and were between the ages of 18 and 50. Forty-four people responded to the recruitment flyer. Five were ineligible, and thirteen ultimately did not attend a session. Each focus group involved between three and seven participants. The five focus groups were conducted between January and March 2012.

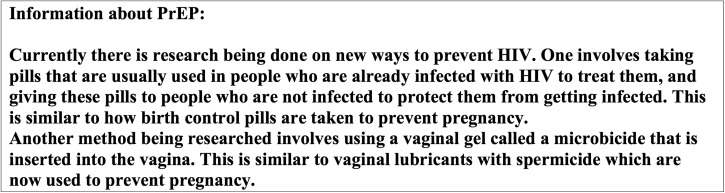

Each participant participated in a 2-h focus group. Informed consent was obtained from participants at the beginning of each focus group. Participants completed a brief self-administered demographic survey at the beginning of the focus group session that recorded age, race, education, zip code, prior focus group experience, and HIV risk perception. Focus groups were facilitated by black women on the study team using a semi-structured discussion guide.The first portion of the discussions centered on HIV risk perception and perception of the ideal prevention strategy. In the second portion, a brief description of PrEP was provided (Fig. 2), followed by questions about hypothetical PrEP acceptability and product preferences. Sessions were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim.

FIG. 2.

Information about PrEP.

A $25 gift card and a meal during the focus group were provided to each participant. Funding for the gift cards was provided by the AMA Foundation Seed Grant Program. The study was approved by the Dimock Community Health Center Institutional Review Board (IRB).

Theoretical model: The Theory of Gender and Power

In this study, the Theory of Gender and Power (Fig. 1) was used as a framework for focus group discussions and analyses to identify key domains related to HIV risk perception and hypothetical acceptability of PrEP, including socioeconomic factors, physical exposures, and social norms. Socioeconomic factors that were explored included poverty and access to care.33 Physical exposures manifest as behavioral risk factors including having one or more partners at high risk for HIV acquisition,34 history of sexual abuse,35 degree of perceived control,33 current HIV risk perception and use of preventive interventions such as condoms,11 and partner communication36 Social norms included religious affiliations,37 desire to conceive,38 and lack of knowledge of HIV prevention strategies.39 Discussions explored how these domains influenced acceptability of PrEP, preferred setting and provider type for accessing PrEP,40 and hypothetical preferences for oral vs. topical PrEP administered as an intravaginal gel. We also explored reasons why participants would try to protect themselves from HIV, how partner dynamics influenced interest in or use of other HIV prevention strategies, and characteristics of prophylactic interventions that would alter acceptability or uptake.

Data analysis

Audio recordings of the focus groups were transcribed verbatim and checked for accuracy during the recruitment period by the PI who attended each focus group. Transcripts were coded with extraction of themes subjected to directed content analysis41 using ATLAS.ti software. Coding of the data highlighted group consensus and deviant case analysis. Illustrative quotations from participants were highlighted where appropriate.36 An initial coding scheme was developed by the PI. Then, three investigators coded 20% of the raw data to ensure reproducibility and authenticity of the coding scheme with approximately 80% inter-coder reliability. Discrepancies were discussed and resolved, and the coding scheme adjusted as needed. The finalized coding scheme was then applied to the rest of the data, and the coded data were analyzed for higher-order themes that form the basis for the results and discussion presented here. The study was closed once thematic saturation was achieved.

Results

Demographic data

The five focus groups yielded a total of twenty-six participants. One study participant did not complete the demographic survey. The median age of study participants was 40 years; ages ranged from 20 to 50 years (Table 1). Twenty-eight percent had less than a high school education, 44% completed high school or its equivalent, 20% completed some college, and 4% completed some graduate or professional school. All participants self-identified as black or African American, with the exception of one, who self-identified as Cape Verdean. The 74% of participants who responded to the question about ethnicity described themselves as non-Hispanic. On the brief demographic survey, of those who responded, 24% described themselves as at-risk for HIV acquisition, 12% described uncertainty, and 52% described themselves as not at-risk. HIV status was not asked of the participants and was not an exclusion criterion; however, during the focus groups two participants self-identified as HIV positive.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics

| Characteristic | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 25 | 100 |

| Race | ||

| Black/African American | 25 | 100 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Hispanic | 0 | |

| Non-Hispanic | 18 | 72 |

| No response | 7 | 28 |

| Education | ||

| Less than high school | 7 | 28 |

| High school/GED | 11 | 44 |

| Some college or more | 6 | 24 |

| No response | 1 | 4 |

| Age in years | ||

| 20–29 | 4 | 16 |

| 30–39 | 3 | 12 |

| 40 or above | 16 | 64 |

N=25; one participant did not fill out the demographic survey.

Ideal prevention strategy

To investigate how PrEP might function as part of a comprehensive prevention strategy, open-ended questions regarding the ideal HIV prevention strategy were asked prior to information about PrEP being given to study participants. The majority of the women reported that they perceived condoms, HIV testing, and abstinence as cornerstones of HIV prevention. For most participants, condoms were described as an accessible, low cost HIV prevention strategy, particularly when abstinence was not an acceptable option. There were varied perceptions of when condoms should be used. One woman felt that consistent condom use was important even for women in stable partnerships.

“I don't think you should trust anyone even if you are married, or something like that. I mean you should, because it's like your partner but., they can step out the marriage just like a single person. You should use a condom regardless of anything.”—age 20

Some women did not use condoms with their main partner, but noted that they would favor condom use when having intercourse with partners outside of their primary relationship. Some women were pleased that their partner usually provided his own condoms, where others noted the need for a female-controlled strategy. Negotiating condom use highlights the Sexual Division of Power described in the Theory of Gender and Power.

“…like a woman's condom. You can put that on before you can go to a club and get your party on. Bring a dude home and he gonna’ act stupid and not want to put a condom on … But you know you gonna’ have sex! You are already protected.”—age 43

Nonetheless, women expressed concerns about condoms breaking or becoming dislodged or getting stuck inside the vaginal vault or rectum. Some women wondered if thicker condoms or if using multiple condoms might be beneficial for some of these issues; however, other women, particularly those in stable relationships, had misgivings about the use of condoms, given decreased sexual pleasure.

“I just think that even though you protect yourself, condoms are not 100%. Condoms do break…I don't put 100% into condoms because they are not always effective, but it is what it is, cause that's all we have. You have to use what you have.”—age 45

Participants reported that they perceived HIV testing as an important component in the ideal prevention strategy. One 20-year-old woman thought frequent and “universal” testing was optimal. She stated that, in the absence of a prevention method that was 100% protective, being aware of a potential partner's HIV status was essential. She described the optimal prevention strategy as having a device in one's home that would allow you to be immediately informed of your prospective partner's HIV status. Some participants felt that frequent testing was optimal, such as after sexual encounters outside of a primary relationship, after changing partners, and every 3 months.

Many women favored abstinence for prevention. Others preferred stable relationships with open communication about outside sexual partners. One woman who had previously been in a high-risk relationship, described the ideal strategy as avoiding such relationships. Other women described alternative routes to sexual pleasure, such as the use of sex toys for self-pleasure, to enable abstinence.

Participants also described novel technologies such as an HIV vaccine or a protective pill to be taken before intercourse or after intercourse in a manner comparable to emergency contraception. One woman described this strategy as the “end of night pill.” Several women desired an antidote to, and a cure for, HIV.

Among women who described that their partner may react negatively at the introduction of condom use, many reported that they felt empowered by the focus group to advocate for condom use. Although some women's actual prevention practices differed from their ideals, some participants shifted their perspectives on personal prevention habits during the discussions.

“I am gonna’ start, you know, using a condom. Then he's probably gonna’ be like, “what's this?” and I'll be like I've been going to class…and my sistah's done schooled me!”—age 47

Pre-exposure prophylaxis acceptability and product preferences

After a brief description of oral and topical PrEP was provided (Fig. 2), participants were asked about their interest in PrEP overall and in the two formulations. A majority of participants expressed interest in PrEP. Most preferred pills to a microbicide gel, given the perception that pills were easy to use and provided greater privacy, whereas gels seemed less private and inconvenient and might cause vaginal irritation, leakage, and general messiness. Participants noted that condoms are free and readily accessible, and that the potential cost of PrEP might be a barrier. Other women were insistent that Medicaid or Mass Health should pay for it.

Preference for pills over gel

Women who were not interested in using condoms due to potential decreased sexual pleasure or condom failure were open to using oral PrEP. Women thought a pill would be easy to conceal and to ingest surreptitiously, thus eliminating the need to discuss concerns about their partner's level of risk.

“…with a pill [if] he says ‘what's that baby?’ you can say ‘my vitamin’. You could always get away with taking the pill. You can always say this is my ‘birth control.”

When asked about her thoughts about potential adverse effects, one participant said:

“If it was some liver damage or kidney damage, you know things like that, then no I would not take it, but something minor…then I would not mind taking it because I take like nine pills a day now. Because I have migraines, I take a lot of medication now.”—age 39

Despite the possibility of adverse effects, most women still indicated interest in oral PrEP. Participants felt that even if pills had adverse effects that those adverse effects would be more tolerable than gel adverse effects, particularly vaginal symptoms.

“Not getting HIV sure is better than the little side effects that you might get, a headache, a flu-like symptom or lose your hair. It's worth it!”

Women who had taken other oral medications were amenable to daily pill use and expressed adherence concerns about episodic or post-coital dosing. Women described how it would fit into their daily routines.

“If it were consistent…like if it were an everyday thing, maybe. I think I would be more comfortable with the pill than with the gel…if I were just taking it every day. I think it would be more easier with the pill.”—age 46

A self-described high-risk woman noted that she takes other medications as prescribed, even when her schedule was chaotic.

“Well, when I was addicted to crack…well I still am addicted, but when I was still using you know I would still take my psych meds though.”—age 27

A 24-year-old college student noted that she would prefer daily over episodic dosing based on whether she were having sex. She noted that if the dosing were episodic she would likely not take it every time it was indicated. She compared this pattern of use to her pattern of episodic use of emergency contraception. Others echoed concerns about adherence to post-coital dosing and pointed out that adherence is more likely when a product requires consistent use. One woman described a sense of security that comes with knowing you are protecting yourself on a daily basis. Participants expressed concerns about how they would access PrEP once available for prescription, noting that if not available, particularly for impromptu intercourse, then they would not be used, particularly in the setting of trading sex for drugs or money.

“When I was out there using, if I did not have it [a condom] I did not have it…If I didn't have a condom I didn't have one but if I had it I would use it.”—age 27

Despite a consensus that pills would be preferable to gels, some women expressed barriers to pill use, particularly if they had a history of negative oral medication experiences, such as intolerable side effects or difficulty swallowing pills. One woman noted that she would be less tolerant of side effects with PrEP because it was being used to prevent a disease, as compared to treating one she already had.

“I don't think they should even bring that pill thing here, because there are gonna’ be side effects too! I think people should just be protected by using condoms.”—age 42

This participant had suffered severe side effects with birth control pills and therefore avoided taking pills. She was hesitant to try anything new as a result of this experience.

Barriers to vaginal gel use

Less than half of the women expressed strong interest in a vaginal microbicide gel and two said they “might” try it. Many women had difficulty envisioning the physical consistency and method of administration of the microbicide gel. The highest risk participants, women trading sex for money or drugs, wondered about the time it would take to insert the gel. Many women thought a gel might be “messy” and potentially would leak throughout the course of the day. One participant suggested an insertion device to contain the medication and prevent leaking. Women were very concerned about the possibility of vaginal symptoms of any sort, inconvenience during oral sex, and potential adverse effects on her sexual partner's penis. One participant wondered if the gel's physical consistency would decrease her or her partner's pleasure during sexual intercourse. There were concerns that sexual partners might detect the gel during intercourse. Another concern was that a gel applied vaginally would not afford protection during anal sex.

Preference for using both pills and gels, or neither

A few of the women would consider using both pills and a gel, in conjunction with a condom, if this strategy would provide enhanced protection.

“Both. Just because, the condom should never go away. Just because you should always regardless of what you are taking, use a condom, plus the pill, plus anything else.”—age 20

Women under 30 were more open to consider using combination approaches (e.g., pill and condoms) than older women, even amongst those who reported less risky behaviors. These women were willing to try either a gel or a pill or would be interested in using both.

A few participants were not interested in using PrEP in any form, largely due to mistrust. Some women felt that PrEP might be a ploy by pharmaceutical companies to make money. Others were concerned that product side effects would not be fully explored prior to the products being brought to market and were worried about being used as “guinea pigs,” as they relayed the many drug recalls advertised on television.

Discussion

The findings in this study of urban black women in Boston demonstrated that women were amenable to using oral PrEP, but had considerable misgivings about using a gel. These findings are consistent with perspectives of the US women enrolled in an open-label cross-over trial of oral and topical PrEP in which a greater proportion of US women as compared to African women preferred oral PrEP to topical PrEP.29 These results are also consistent with studies of women's product preferences for contraception, in which women were more accepting of oral contraceptives than of topical contraceptives, without counseling from a provider.42 One Indian study noted that women preferred an oral formulation of PrEP because of their perception that it offered greater potential for undisclosed use.43

In this study, women generally preferred daily dosing and believed it would enhance the likelihood of adherence. This finding is consistent with a qualitative study of women enrolled in an oral PrEP acceptability trial in which women reported that adherence to a daily pill became easier over time.25

The Theory of Gender and Power describes exposures, social/behavioral risk factors, and biological properties that create vulnerability to HIV; however, these women emphasized perceived product experience and personal beliefs about risk over other social norms and economic exposures when formulating their preferences. Of note, some of the socioeconomic pressures in this group may have been balanced by having access to care via the existing healthcare reform in Massachusetts where the study was conducted.

Among US black women, oral PrEP may provide an acceptable female-controlled complement to condoms,44 needle exchange, behavioral strategies, and enhanced testing.28 The Theory of Gender and Power (TGP) describes power differentials that limit a woman's capacity to influence men to use condoms. Choices between oral and topical PrEP may also influence condom acceptability. Prior mixed methods data revealed that some people feel topical agents in particular might make condom use more appealing by enhancing sexual pleasure.31 Partnership status and partner experience may also influence decisions about using condoms.45 Women's preferences regarding condom use is influenced by numerous contextual factors (personal, behavioral, and socioeconomic).10–12,46–48 The current investigation provides novel insights about how these same factors may also influence the uptake of oral or topical PrEP in an at-risk US population.

In clinical trials of PrEP, adherence has proven to be a critical component of effectiveness.14–20 For example, the lack of oral PrEP effectiveness among African women in the VOICE trial was likely a result of poor adherence as demonstrated by the infrequent detection of study drug in the blood of study participants.19 The finding in the current study that black women perceive that daily dosing could facilitate adherence as compared to episodic dosing suggests that implementing daily oral PrEP among at-risk women may be feasible and acceptable. Provider emphasis of the need for daily pill use, as opposed to pericoital use, may also facilitate adherence. If topical PrEP is to play a role in a comprehensive HIV prevention strategy among black women, education about gel consistency and the specifics of vaginal gel use will be important in enhancing acceptability. Importantly, confirmation of the effectiveness of pericoitally administered topical PrEP is needed before this intervention can be recommended, and this confirmation may come from the ongoing FACTS trial.49

As data emerge on the effectiveness and uptake of PrEP, further investigation of the parameters of acceptability among US black women will be needed. These focus groups were conducted prior to US Food and Drug Administration approval of tenofovir-emtricitabine for use as daily oral HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis in 201250 and before US Public Health Service Guidelines regarding PrEP provision were released in May 2014,51 so perceptions and norms may have evolved subsequently. The beliefs and attitudes of this limited sample of women may not generalize to other at-risk US women with different demographic or geographic characteristics. In particular, the presence of health care reform in Massachusetts, a structural change that may have eased some of the inequities emphasized in TGP, provided access to care to most residents, and is likely to have influenced the perspectives of the study participants, even those recruited from HIV testing sites who may have not been actively engaged in longitudinal care. Nonetheless, with the advent of the US Affordable Care Act and the potential expansion of health care access, these study participants may offer key insights on changing perspectives among at-risk women. The women in these focus groups also alert us to the ethical concerns of potential PrEP users regarding disclosure of PrEP use to their sexual partner when a topical agent is used to which the male partner will be exposed. Consideration of their partner's experience of topical PrEP and the potential influence of partner experience on a woman's decisions highlights another social norm that influences women's preventive behaviors. Further qualitative and/or quantitative studies of PrEP acceptability and product preferences amongst at-risk urban black women are warranted.

The complexities of choice are an important consideration as women weigh competing priorities. In clinical trials, some PrEP users found the benefits of protection outweighed “nuisance factors” such as gel messiness or consistency;52 however, the lack of adherence in other trials suggests this thought process may not be universal among women.19 Exploring women's perspectives in light of social structural theory such as The Theory of Gender and Power may help explain some of the complexities of individual behaviors in the context of social norms and structural constructs. Qualitative studies provide important information for assessing product acceptability,28,44 and qualitative methodology is particularly well-suited to explaining why women choose to use or not to use PrEP in a “real-world” context, where products are less than 100% effective, and adherence may be imperfect.53

Conclusions

Analyses of focus groups among black women from an inner-city clinic in Boston suggest that women find oral and topical PrEP to be acceptable. Daily use of oral formulations are generally preferred to topical PrEP due to perceptions of fewer undesirable consequences of topical product use and the possibility of taking oral medications without disclosure to male sexual partners, among other reasons. When considering these results in the context of the complex gender and power dynamics that limit utilization of condoms and other HIV prevention strategies among black women in the US, this study suggests that PrEP may be a feasible and effective intervention that offers unique advantages for this population.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the AMA Foundation for providing grant support for this research, the Dimock Community Health Center, Marguerite Gunning for transcription, and Rose Closson for help coordinating this study.

Author Disclosure Statement

Dr. Flash would like to disclose investigator initiated grant support from Gilead Sciences. Dr. Mayer would like to disclose unrestricted research funds from Gilead Sciences. Dr. Krakower is supported by NIMH K23 MH098795 and would like to disclose that he has conducted research with project support from Gilead Sciences and Bristol Myers Squibb.

References

- 1.CDC. HIV Surveillance Report, 2009. February2011:http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/resources/reports/, 21 (Last accessed September26, 2011) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heron M. Deaths: Leading causes for 2007. Natl Vital Stat Rep 2011;59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.CDC. Leading causes of death by age group, Black Females-United States, 2009*. Leading Causes of Death in Females [website PDF]. January2, 2013; http://www.cdc.gov/women/lcod/ (Last accessed October17, 2013)

- 4.Aral SO, Adimora AA, Fenton KA. Understanding and responding to disparities in HIV and other sexually transmitted infections in African Americans. Lancet 2008;372:337–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hallfors DD, Iritani BJ, Miller WC, Bauer DJ. Sexual and drug behavior patterns and HIV and STD racial disparities: The need for new directions. Am J Public Health 2007;97:125–132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Quinlivan EB, Messer LC, Adimora AA, et al. . Experiences with HIV testing, entry, and engagement in care by HIV-infected women of color, and the need for autonomy, competency, and relatedness. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2013;27:408–415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wingood GM, Scd , DiClemente RJ. Application of the theory of gender and power to examine HIV-related exposures, risk factors, and effective interventions for women. Health Educ Behav 2000;27:539–565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raiford JL, Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ. Correlates of consistent condom use among HIV-positive African American women. Women Health 2007;46:41–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.CDC. High Impact HIV Prevention: CDC's Approach to Reducing HIV Infections in the United States. website]. April2013; http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/strategy/hihp/report/index.htm (Last accessed July28, 2014)

- 10.Panchanadeswaran S, Frye V, Nandi V, Galea S, Vlahov D, Ompad D. Intimate partner violence and consistent condom use among drug-using heterosexual women in New York City. Women Health 2010;50:107–124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Leval A, Sundstrom K, Ploner A, Dahlstrom LA, Widmark C, Sparen P. Assessing perceived risk and STI prevention behavior: A national population-based study with special reference to HPV. PloS One 2011;6:e20624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ. Partner influences and gender-related factors associated with noncondom use among young adult African American women. Am J Community Psychol 1998;26:29–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Seth P, Raiford JL, Robinson LS, Wingood GM, Diclemente RJ. Intimate partner violence and other partner-related factors: Correlates of sexually transmissible infections and risky sexual behaviours among young adult African American women. Sex Health 2010;7:25–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abdool Karim Q, Abdool Karim SS, Frohlich JA, et al. . Effectiveness and safety of tenofovir gel, an antiretroviral microbicide, for the prevention of HIV infection in women. Science 2010;329:1168–1174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thigpen MC, Kebaabetswe PM, Paxton LA, et al. . Antiretroviral preexposure prophylaxis for heterosexual HIV transmission in Botswana. N Engl J Med 2012;367:423–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baeten JM, Donnell D, Ndase P, et al. . Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV prevention in heterosexual men and women. N Engl J Med 2012;367:399–410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Van Damme L, Corneli A, Ahmed K, et al. . Preexposure prophylaxis for HIV infection among African women. N Engl J Med 2012;367:411–422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Network MT. Fact Sheet for The VOICE Study: Vaginal and Oral Interventions to Control the Epidemic. 2011. http://www.mtnstopshiv.org/node/2003 (Last accessed July28, 2014)

- 19.Marrazzo J, Ramjee G, Nair G, et al. . Pre-exposure Prophylaxis for HIV in Women: Daily Oral Tenofovir, Oral Tenofovir/Emtricitabine, or Vaginal Tenofovir Gel in the VOICE Study (MTN 003). Paper presented at: Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; March 4, 2013, 2013, Atlanta, GA [Google Scholar]

- 20.van der Straten A, Van Damme L, Haberer JE, Bangsberg DR. Unraveling the divergent results of pre-exposure prophylaxis trials for HIV prevention. AIDS 2012;26:F13–F19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krakower DS, Mimiaga MJ, Rosenberger JG, et al. . Limited awareness and low immediate uptake of pre-exposure prophylaxis among men who have sex with men using an Internet social networking site. PLoS One 2012;7:e33119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brooks RA, Kaplan RL, Lieber E, Landovitz RJ, Lee SJ, Leibowitz AA. Motivators, concerns, and barriers to adoption of preexposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention among gay and bisexual men in HIV-serodiscordant male relationships. AIDS Care 2011;23:1136–1145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eisingerich AB, Wheelock A, Gomez GB, Garnett GP, Dybul MR, Piot PK. Attitudes and acceptance of oral and parenteral HIV preexposure prophylaxis among potential user groups: A multinational study. PLoS One 2012;7:e28238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Galea JT, Kinsler JJ, Salazar X, et al. . Acceptability of pre-exposure prophylaxis as an HIV prevention strategy: Barriers and facilitators to pre-exposure prophylaxis uptake among at-risk Peruvian populations. Int J STD AIDS 2011;22:256–262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guest G, Shattuck D, Johnson L, et al. . Acceptability of PrEP for HIV prevention among women at high risk for HIV. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2010;19:791–798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heffron R, Ngure K, Mugo N, et al. . Willingness of Kenyan HIV-1 serodiscordant couples to use antiretroviral-based HIV-1 prevention strategies. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2012;61:116–119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khawcharoenporn T, Kendrick S, Smith K. HIV risk perception and preexposure prophylaxis interest among a heterosexual population visiting a sexually transmitted infection clinic. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2012;26:222–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith DK, Toledo L, Smith DJ, Adams MA, Rothenberg R. Attitudes and program preferences of African-American urban young adults about pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). AIDS Educ Prev 2012;24:408–421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Minnis AM, Gandham S, Richardson BA, et al. . Adherence and acceptability in MTN 001: A randomized cross-over trial of daily oral and topical tenofovir for HIV prevention in women. AIDS Behav 2013;17:737–747 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Whiteside YO, Harris T, Scanlon C, Clarkson S, Duffus W. Self-perceived risk of HIV infection and attitudes about preexposure prophylaxis among sexually transmitted disease clinic attendees in South Carolina. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2011;25:365–370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hoffman S, Morrow KM, Mantell JE, Rosen RK, Carballo-Dieguez A, Gai F. Covert use, vaginal lubrication, and sexual pleasure: A qualitative study of urban U.S. women in a vaginal microbicide clinical trial. Arch Sex Behav 2010;39:748–760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wingood GM, Dunkle K, Camp C, et al. . Racial differences and correlates of potential adoption of preexposure prophylaxis: Results of a national survey. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2013;63:S95–S101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ. Application of the theory of gender and power to examine HIV-related exposures, risk factors, and effective interventions for women. Health Edu Behav 2000;27:539–565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wagstaff DA, Kelly JA, Perry MJ, et al. . Multiple partners, risky partners and HIV risk among low-income urban women. Family Planning Perspect 1995;27:241–245 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ, Raj A. Adverse consequences of intimate partner abuse among women in non-urban domestic violence shelters. Am J Prev Med 2000;19:270–275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kitzinger J. Qualitative research—Introducing focus groups. Br Med J 1995;311:299–302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Washington TA, Wang Y, Browne D. Difference in condom use among sexually active males at historically black colleges and universities. J Am Coll Health 2009;57:411–416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Matthews LT, Baeten JM, Celum C, Bangsberg DR. Periconception pre-exposure prophylaxis to prevent HIV transmission: Benefits, risks, and challenges to implementation. AIDS 2010;24:1975–1982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sutton MY, Hardnett FP, Wright P, et al. . HIV/AIDS knowledge scores and perceptions of risk among African American sudents attending historically black colleges and universities. Public Health Rep 2011;126:653–663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Myers GM, Mayer KH. Oral preexposure anti-HIV prophylaxis for high-risk US populations: Current considerations in light of new findings. Aids Patient Care Stds 2011;25:63–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res 2005;15:1277–1288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Harper CC, Brown BA, Foster-Rosales A, Raine TR. Hormonal contraceptive method choice among young, low-income women: How important is the provider? Patient Educ Couns 2010;81:349–354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chandhiok N, Joshi SN, Gangakhedkar R. Acceptability of oral and topical HIV chemoprophylaxis in India: Implications for at-risk women and men who have sex with men. Sex Health October112013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rosen RK, Morrow KM, Carballo-Dieguez A, et al. . Acceptability of tenofovir gel as a vaginal microbicide among women in a phase I trial: A mixed-methods study. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2008;17:383–392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mason TH, Foster SE, Finlinson HA, et al. . Perspectives related to the potential use of vaginal microbicides among drug-involved women: Focus groups in three cities in the United States and Puerto Rico. AIDS Behav 2003;7:339–351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Macaluso M, Demand MJ, Artz LM, Hook EW, 3rd., Partner type and condom use. AIDS 2000;14:537–546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ghimire L, Smith WC, van Teijlingen ER, Dahal R, Luitel NP. Reasons for non-use of condoms and self- efficacy among female sex workers: A qualitative study in Nepal. BMC Womens Health 2011;11:42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kalichman SC, Williams EA, Cherry C, Belcher L, Nachimson D. Sexual coercion, domestic violence, and negotiating condom use among low-income African American women. J Womens Health 1998;7:371–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Network MT. Microbicide Trials Network Fact Sheet: About Microbicides. March25, 2014; http://www.mtnstopshiv.org/node/706 (Last accessed July28, 2014)

- 50.United States Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves first drug for reducing the risk of sexually acquired HIV infection. July17, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 51.United States Public Health Service. Pre-exposure Prophylaxis for the Prevention of HIV Infection in the United States–2014. May19, 2014; http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/PrEPguidelines2014.pdf (Last accessed July17, 2014)

- 52.Bentley ME, Morrow KM, Fullem A, et al. . Acceptability of a novel vaginal microbicide during a safety trial among low-risk women. Fam Plann Perspect 2000;32:184–188 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.van der Straten A, Stadler J, Montgomery E, et al. . Women's experiences with oral and vaginal pre-exposure prophylaxis: The VOICE-C qualitative study in Johannesburg, South Africa. PloS One 2014;9:e89118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]