Abstract

Metastasis begins when tumors invade into surrounding tissues. In breast cancer, the study of cell interactions has provided fundamental insights into this complex process. Powerful intravital and 3D organoid culture systems have emerged that enable biologists to model the complexity of cell interactions during cancer invasion in real-time. Recent studies utilizing these techniques reveal distinct mechanisms through which multiple cancer cell and stromal cell subpopulations interact, including paracrine signaling, direct cell–cell adhesion, and remodeling of the extracellular matrix. Three cell interaction mechanisms have emerged to explain how breast tumors become invasive: epithelial–mesenchymal transition, collective invasion, and the macrophage–tumor cell feedback loop. Future work is needed to distinguish whether these mechanisms are mutually exclusive or whether they cooperate to drive metastasis.

Introduction

Mortality in cancer is caused by the tumor’s ability to invade into surrounding tissues and metastasize to distant organs [1]. The past decade has unveiled important insights into the genetic basis, host dependence, and tissue requirements of these complex processes [2–4]. In this brief review, we examine recent progress toward understanding the cancer cell and stromal cell subpopulations that mediate tumor invasion, and the dominant mechanisms through which these different cell populations interact. We focus primarily on invasive breast tumors, the major features that define their tissue architecture and cellular organization, and discuss new concepts regarding the cellular interactions that drive the invasive and metastatic processes.

Cell interactions in breast cancer invasion: an emerging network

Invasive breast tumors exist within a complex microenvironment composed of diverse cell types and extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins, which play important roles in tumor initiation, angiogenesis, immune evasion, invasion and metastasis [2,5–8]. During tumor progression, the local tissues change significantly. In the normal breast, the mammary ductal network is composed of branched ducts and lobular structures [9]. In turn, these structures are composed of bilayered epithelial tubes, which are divided into an inner layer of luminal epithelial cells and an outer layer of myoepithelial cells that lie in contact with basement membrane [9]. Human breast cancers are thought to arise most commonly from epithelial cells in the terminal duct lobular unit [10]. Invasive breast tumors are clinically defined by the presence of cancer cells beyond the myoepithelial layer and the surrounding basement membrane [11]. Often, myoepithelial cells are no longer detectable in poorly differentiated tumors [12].

Many stromal cell populations also increase in number during cancer progression, including fibroblasts, myofibroblasts, pro-tumorigenic leukocytes, and endothelial cells [13]. The ECM in the tumor microenvironment also changes in its content, organization, and biomechanical properties, typically becoming fibrotic and rich in collagen I [14,15]. Together, this creates a rich environment for cancer cells to interact with their neighbors. In this section, we describe the broad mechanisms regulating these cells, focusing on three major classes of cell interactions: signaling through soluble factors, cell–cell adhesion, and ECM remodeling.

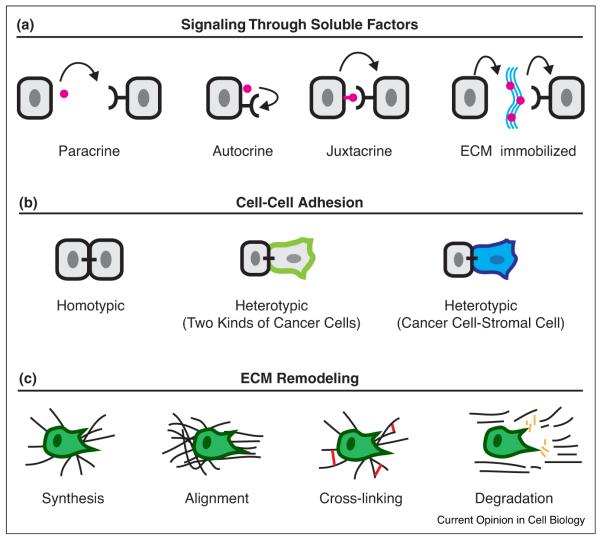

Soluble factor signaling: multiple modes

The most well recognized mechanism for cell–cell interactions is paracrine signaling (Figure 1a). Paracrine signaling enables information exchange between cells via the transmission of a diffusible soluble signal from one cell to another [16]. Paracrine signals are diverse and include growth factors, cytokines, hormones, as well as non-peptide mediators such as prostaglandins and sphingosine-1-phosphate [13,17–20]. Further, a recent study reveals that exosomes can also deliver paracrine signals [21••]. Cancer-associated fibroblasts secrete CD81+ exosomes, which are endocytosed by breast cancer cells, and induce invasion through WNT-PCP signaling [21••]. However, still more complicated signaling relationships are possible. These include autocrine signaling [22], juxtacrine signaling, in which the signal is membrane-bound and non-diffusible, such as for TGF-alpha [23–26], and ECM sequestration such as by the sequestration of TGF-beta by latent TGF-beta binding protein [27–29] (Figure 1a). These sequestered factors can be released through proteolysis and become bio-active signals [28]. Chemokine signaling gradients also play an important role in the directed migration of breast cancer cells and homing to metastatic sites [30–32]. Cumulatively, these paracrine signals create spatially distinct tumor microenvironments in vivo that modulate cancer cell behaviors locally [33]. In the complex tissue environment in vivo, bidirectional signaling networks also emerge from paracrine interactions between cells [19,34–36]. Cancer cells release soluble factors that regulate the behaviors of the cells around them, creating opportunities for signaling feedback. For example, bidirectional paracrine signaling provides a potent mechanism for macrophages and breast cancer cells to coordinate their cell movements [32,37]. Thus, soluble factors span a spectrum of sizes, from modified lipids to multi-protein exosome complexes, and mediate cell–cell communication through diverse signaling mechanisms.

Figure 1.

Three major classes of cell interactions in breast cancer invasion. (a) Breast cancer invasion arises from diverse cell interactions that fall into three major categories: soluble factor signaling, cell–cell adhesion, and ECM remodeling. These interactions often produce molecularly specific signaling consequences and more general mechanical cues. In paracrine signaling, there is diffusion of a soluble signal from one cell to another. In autocrine signaling, the soluble signal acts upon the signal-generating cell. In juxtacrine signaling, the signal is membrane immobilized and communicates with immediate neighbors. In ECM-immobilized signaling, the secreted signal becomes immobilized to ECM often with the help of extracellular binding proteins. Subsequent matrix degradation liberates the immobilized signal. (b) Cell–cell adhesion is another major category of cell interaction. Invasive breast tumors are cohesive and typically retain E-cadherin-based homotypic contacts. Heterotypic contacts can occur between phenotypically distinct cancer cells during collective invasion. In addition, heterotypic cell adhesion also occurs between cancer cells and stromal cells such as fibroblasts and macrophages. (c) The ECM undergoes significant remodeling during tumor progression and is a potent regulator of cancer cell behavior. Cells can promote remodeling in at least four ways, by increasing synthesis, alignment, and crosslinking of matrix or by facilitating its proteolysis.

Cell–cell adhesion: the epithelial paradox

Direct cell–cell adhesion is another important mechanism for cell interactions in breast cancer (Figure 1b). These cell interactions involve not only homotypic adhesion complexes between breast cancer cells but also heterotypic adhesion complexes between breast cancer cells and stromal cell populations such as fibroblasts, macrophages, and bone marrow stromal cells [38–40]. In vivo, invasive breast tumors are typically composed of cohesive nests, chains, and clusters of tumor cells [41••]. The cell cohesion of breast tumors is often underappreciated. One reason is that breast tumors are also less differentiated, display reduced apicobasal cell polarity, and lose contact with the basement membrane [42,43]. However, even in the setting of poorly differentiated breast tumors, cancer cells are typically adherent to each other and retain many epithelial features including epithelial cytokeratins, tight junctions, and desmosomes [44–49].

ECM remodeling: action at a distance

The ECM acts as an intermediate in the transmission of signals between different cells. Cells can modulate both the composition and structure of the ECM [14,50–52]. This remodeling is accomplished by multiple mechanisms including the synthesis, degradation, alignment, and cross-linking of the matrix (Figure 1c) [6–8,14]. These changes will, in turn, affect signaling from cell–matrix adhesion receptors, such as integrins and DDRs [53,54•]. Signaling by growth factor receptors will also be altered; either directly via changes in growth factor binding to the ECM (e.g. HB-EGF or TGFβ) or indirectly by cross-talk between integrins and growth factors receptors. In addition, the ECM is a physical scaffold that can act either as a barrier or conduit for breast cancer invasion. The ECM can severely restrict cancer cell migration in specific regimes of matrix porosity, elasticity, and rigidity [50,52]. For example, in collagen matrices of small pore diameter, migrating cancer cells becomes physically limited by their ability to deform their nuclei through tight spaces [52,55••]. Depending on the degree of confinement, the relative amounts of cell–cell and cell–matrix adhesion experienced by cancer cells also varies and in turn can modulate the efficiency and optimal mode of cancer invasion [56,57••]. Conversely, during tumor progression, the emergence of dense aligned collagen fibrils greatly facilitates invasion of breast cancer cells [58,59]. Because the ECM encodes a rich set of chemical and physical cues, remodeling the ECM provides a potent mechanism for cells to modulate cancer cell behaviors.

Mechanisms of breast tumor invasion and their cell interactions

In this section, we discuss recent progress in our understanding of how breast cancers invade and how cell interactions outlined in the prior section mediate these processes. Three major mechanisms have been proposed to explain how breast tumors invade into surrounding tissues: epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT), collective invasion, and the macrophage–tumor cell feedback loop. In addition, we highlight the importance of tumor cell–matrix interactions specifically involving collagen I, which plays a crucial role in breast cancer invasion across mechanisms. Throughout, we synthesize how these mechanisms operate in a commonly studied genetically engineered mouse model of breast cancer, MMTV-PyMT [60]. This tumor model has histology that resembles invasive ductal carcinoma, undergoes progression with invasion and metastasis, and has a gene expression profile that is most similar to luminal B, an aggressive and common subtype of human breast cancer [61–63].

Throughout, we also describe several powerful experimental systems that enable real-time analysis, and perturbation, of cell–cell interactions (see Box). One important system is intravital imaging, which enables study of the invasive process in its native environment in genetically engineered mouse models and more recently in patient-derived xenografts [64–67]. Tumor organoids have also emerged as a valuable experimental platform in which to isolate cell interactions and to study the invasive process from patient samples [68••,69••]. For further details on the technical aspects of these experimental systems, we recommend recent reviews [70–73].

Box 1. Understand cell interactions in breast cancer invasion: experimental models and histologic validation.

Clinically, invasion is an insidious process that is detected by biopsies and diagnostic imaging, but which is never dynamically observed at cellular resolution in human patients. This temporal blindness poses an important barrier to understanding cell interactions in these processes. There are limits to what can be inferred from the study of morphologically complex fixed human samples. Given these limitations, experimental models of invasion and metastasis have therefore been valuable [151–153]. However, even in these models, there are further challenges created by the heterogeneity of breast cancer. This heterogeneity is caused by differences not only between breast tumor subtypes and differences between host environments [153], but also by differences within individual tumors [112]. The composition of cancer cells, stroma, stromal fibroblasts, and immune cells is highly variable even in nearby regions of tumor [66]. Intra-vital imaging of xenograft model show that between 1% and 5% of tumor cells are migratory at any given time [154]. Differences in extracellular matrix composition and in paracrine signaling environments induce acute changes in invasive behavior [33,69••]. Thus, to image cell-interactions in tumors, we need to not only know where to look, but also to look enough times and in enough places to establish confidence in our conclusions.

The epithelial–mesenchymal transition

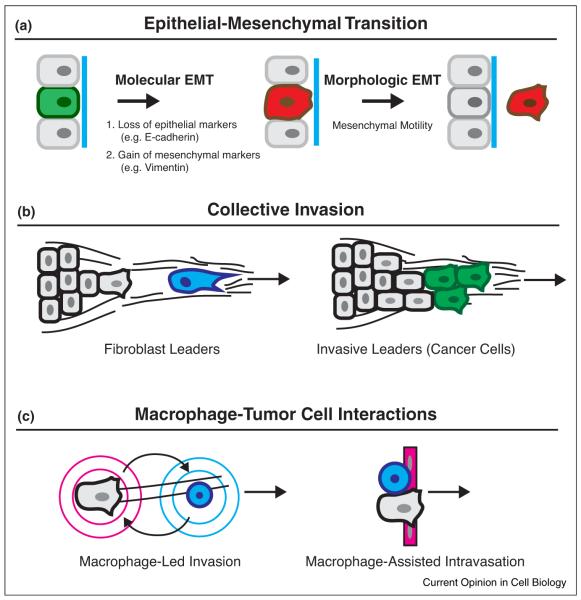

A major model by which cancer cells are proposed to acquire invasive motility is the epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) (Figure 2a). EMT is variously defined based on either a morphologic change from epithelial organization to mesenchymal cell motility or based on molecular changes, typically loss of E-cadherin and gain of mesenchymal markers such as N-cadherin and vimentin [74–76]. In cancer-associated EMT, molecular programs normally expressed during embryonic development become pathologically reactivated [74–76]. In the EMT model, the initiation of metastasis is conceptualized as a molecular switch, which induces the dissemination of epithelium to single migratory cells. Because E-cadherin is expressed in metastatic sites [77], disseminated cells that undergo EMT are proposed to experience a reverse mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition (MET) in distant organs [78].

Figure 2.

Major mechanisms for breast cancer invasion. Three major mechanisms have been identified to explain how breast cancers invade: EMT, collective invasion, and macrophage–tumor cell interactions. In addition, for all three of these mechanisms, tumor cell-matrix interactions with collagen I provide essential chemical and physical cues for breast cancer invasion. (a) In EMT, tumor cells transition from epithelial organization to mesenchymal motility. The EMT is variably defined by a molecular EMT that includes loss of E-cadherin and gain of mesenchymal markers, and by a morphologic EMT that includes a change to mesenchymal cell motility. As depicted, EMT models generally conceptualize the molecular EMT as occuring first in this sequence. However, recent studies indicate that mesenchymal motility can occur without going through a molecular EMT. (b) In vivo, breast tumors typically invade cohesively as a multicellular unit, termed collective invasion. In breast cancer, two leader cell populations have emerged, stromal fibroblasts and invasive leader cells, which are a specialized subpopulation of breast cancer cells. Stromal fibroblasts facilitate invasion by path clearing and matrix remodeling ahead of the collective invasion front. By contrast, invasive leader cells are directly coupled by cell-adhesion to trailing cells. (c) A third major mechanism for invasion is the interaction of macrophages and tumor cells. Macrophages promote invasion of cancer cells to blood vessels and assist in their intravasation. Macrophages promote the efficient migration of cancer cells along collagen fibers via the macrophage–tumor cell feedback loop. By a second mechanism, direct cell–cell adhesion between macrophage and cancer cell promote intravasation through endothelium.

In breast cancer, the core EMT gene signature is associated with the claudin-low molecular subtype, which shows low expression for genes encoding tight junction and adherens junctions proteins [79–81]. This subtype is enriched for triple negative breast tumors (ER-, PR-, HER2-) which have poor prognosis, and histologic subtypes with a prominent spindle cell component, including metaplastic carcinomas and medullary carcinomas [79–81]. Experimentally, the claudin-low gene signature clusters with a subset of invasive breast cancer cell lines that includes the widely used triple-negative cell line MDA-MB-231 [82]. However, claudin-low tumors are also the least common breast cancer subtype accounting for ~12% of tumors [83]. Thus, although the core EMT signature appears in a subset of human breast tumors, most human breast tumors do not express the core EMT signature. Concordantly, in MMTV-PyMT mammary tumor, a model of luminal B breast cancer, epithelial–mesenchymal transitions are not detected when epithelial cells are lineage marked or when RNA is analyzed in actively invading tumor organoids [69••,84]. Despite the absence of evidence for a molecular EMT in this mouse model, the large majority of mice develop lung metastases [60].

Recent studies have also identified multiple genes that promote invasion and metastatic progression without obvious EMT. When the mucin-like protein podoplanin is overexpressed in breast cancer cells, filopodia and cell migration is induced [85]. However podoplanin-over-expressing cells retain E-cadherin expression and do not upregulate N-cadherin or vimentin [85]. Two recent studies independently show that loss of the polarity regulator Par3 promotes metastasis in vivo without affecting E-cadherin expression [86••,87••]. In ErbB2 tumors, loss of Par3 did not affect E-cadherin expression or localization, but instead affected cell cohesion through reduced junctional stability [87••]. Furthermore, a recent study reveals that induction of an EMT transcription factor is sufficient to induce single cell dissemination without molecular EMT [88••]. Expression of the transcription factor Twist1 in normal mammary epithelial organiods induces extensive single cell dissemination [88••]. However, disseminated cells retain epithelial character, including cytokeratin expression and membrane-localized adherens junctions proteins, such as E-cadherin. In addition, E-cadherin knockdown strongly inhibits Twist1-induced single cell dissemination [88••]. Transcriptome analyses demonstrate that canonical EMT transcriptional targets are not differentially expressed between Twist1+ versus control organoids [88••]. Instead, concerted changes occur in a suite of genes associated with cell–matrix adhesion and the extracellular compartment. These data reveal that changes in ECM remodeling and interaction are a major functional output of Twist-mediated gene expression. In aggregate, these studies indicate that morphologic EMT can be uncoupled from canonical molecular EMT and support the concept that Twist1 can induce dissemination through expression of an epithelial migratory program without a transition to mesenchymal cell fate [88••].

Collective invasion

Cell cohesion in breast cancer is often overlooked and it is commonly assumed that during breast cancer progression, E-cadherin is uniformly lost. However, studies of human breast tumors in vivo have established that E-cadherin expression differs significantly between histologic subtypes [89–93]. ~75% of all breast cancer cases are invasive ductal carcinomas [94,95], and in these tumors, membrane E-cadherin expression is absent in <10% of cases [89–93]. By contrast, ~10% of all breast cancers are invasive lobular carcinomas, in which E-cadherin loss is a defining characteristic and genetic studies firmly establish E-cadherin as a bona-fide tumor suppressor [96,97]. Accounting for the prevalence of different histologic subtypes, E-cadherin is expressed in the majority of breast tumors. In addition, breast cancer metastases typically express membrane E-cadherin at equal and often greater levels than in the primary tumor [77,98]. Interestingly, inflammatory breast carcinomas, a rapidly invasive and metastatic form of locally advanced breast carcinoma, uniformly overexpress membrane E-cadherin in primary tumors, lymphatic tumor emboli, and metastases [99–102]. Taken together, these studies indicate that breast tumors are typically cohesive and often display membrane-localized E-cadherin in both the primary breast tumor and distant metastases.

The process by which cohesive groups of cancer cells invade into surrounding stroma is termed collective invasion [41••,103]. Direct visualization of this process has revealed collective invasion in a variety of solid tumor types and in human breast tumors [33,69••,104,105]. In the past few years, multiple mechanisms have emerged to address how epithelial breast tumors invade collectively.

Fibroblast leaders

One solution for collective cell motility is the participation of stromal fibroblasts, which are intrinsically mesenchymal and excel in ECM modeling, a potent mechanism for cell–cell communication [17,18,35,106]. In a 3D organotypic model of invasion, exogenously added fibroblasts act as leader cells for trailing cohesive squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) cells [106] (Figure 2b). These fibroblasts remodel the ECM, which creates micro-tracks for trailing cancer cells [106]. These micro-tracks were able to guide SCC invasion after the fibroblasts were ablated pharmacologically, demonstrating that fibroblasts can influence invasion even without proximity in time or space [106]. Interestingly, the migratory program of leading fibroblasts was dependent on ITGA3, ITGA5, and Rho signaling whereas in following cancer cells, motility was Cdc42 and MRCK-dependent [106]. Importantly, disruption of signaling in the fibroblasts blocked cancer cell invasion, demonstrating that targeting the leader cell population was sufficient to disrupt the entire multicellular ensemble. More recent work demonstrates that fibroblasts also support collective invasion in breast cancer models and that this mechanism is subtype dependent [107]. Fibroblast-led invasion was observed in a basal subtype breast cancer cell line but not in a luminal subtype cell line [107]. In vivo, fibroblasts promote invasion in breast cancer models including in MMTV-PyMT tumor models, and this activity is regulated by TGF-beta and YAP signaling pathways [35,108••,109].

Cancer cell leaders

Human breast tumors are composed of tumor cells that are genetically and phenotypically heterogeneous, which has implications for resistance to therapy and metastatic potential [110]. Multiple studies demonstrate that intrinsic differences in invasive motility between tumor cells affect the leader follower arrangement of collectively invading cancer cells [111,112]. For example, MT1-MMP expressing breast cancer cells generate micro-tracks that enable migration of trailing cancer cells, and collective invasion is abolished when MT1-MMP-mediated proteolysis is disrupted [112]. Similarly, when heterotypic cancer cell lines are mixed together, highly migratory MDA-MB-231 cells lead the invasion of weakly migratory MCF7 cells [111]. Together these studies have raised the question of how different subpopulations of tumor cells contribute to collective invasion in vivo.

A recent study has revealed that in primary breast tumors, collective invasion is led by a subpopulation of specialized cancer cells [68••]. A 3D organoid model was developed to identify leading cell populations from collectively invading organoids derived from primary breast tumors [68••,69••]. The cells at the front of invasive strands, denoted ‘invasive leaders cells’, were directly coupled by cell–cell adhesion to follower cells via membrane E-cadherin [68••]. Invasive leaders did not exhibit a molecular EMT [69] and instead expressed a basal epithelial gene program, which included intermediate filament cytokeratin-14 (K14) and the nuclear transcription factor p63 [68••]. Unlike normal differentiated myoepithelial cells, invasive leaders did not express a smooth muscle contractility program [68••]. K14+ invasive leaders were identified as the major leading cell population across major subtypes of breast cancer and in breast tumors from diverse patient samples [68••]. In the MMTV-PyMT model, knockdown of K14 blocked collective invasion in both 3D culture and in vivo [68••], despite detectable expression of K14 in fewer than 2% of tumor cells. Therefore, disrupting the most invasive cancer cell subpopulation abrogrates collective cell invasion throughout the tumor [68••]. This study establishes the concept of cooperation between cancer cells in different epithelial differentiation states as a driving force for collective invasion.

Although mechanisms for generating leader cells have been described in developmental processes and in wound repair [103,113,114], the mechanisms that underlie induction of leader cells in tumors are not well understood. In MMTV-PyMT mammary tumor, leader cells are generated by interconversion between cell differentiation states rather than existing as a fixed lineage [68••]. Luminal tumor organoids are initially K14−, and tumor cells in contact with the cell–matrix border can then acquire K14 expression [68••]. Interestingly, in other tumor types such as lung cancer and hepatocellular carcinoma, expression of basal cytokeratins correlated with more invasive characteristics [115•,116•]. The precise mechanism for the phenotypic switch to invasive leaders is incompletely understood. However, changes in ECM matrix composition are likely to contribute to this process [68••,117,118•]. For example, in MMTV-PyMT mice deficient for lysyl-oxidase, the frequency of K14+ cells is significantly reduced [117]. Furthermore, in a model of premalignant disease, basal-like mammary epithelial cells toggle between gene expression states and this regulation is dependent on interactions with the extracellular matrix [118•]. Interestingly, loss of cell adhesion induces KRT5, a feature of high-grade DCIS [35,118•]. Thus, signals from the tissue environment, both gained and lost, may promote the dynamic emergence of leader cell populations favorable for collective invasion and metastasis.

Macrophage–tumor cell interactions

In a number of studies, tumor-associated macrophages accumulate in areas of necrosis and increased vascularity density and are associated with worse prognosis [119–122]. In macrophage-deficient op/op;PyMT mice, tumor progression and tumor metastasis is significantly delayed [63]. These observations have provided a strong rationale to understand how tumor-associated macrophages interact with cancer cells to promote breast cancer invasion and metastasis.

The accumulated evidence indicates that tumor-associated macrophages facilitate invasion and intravasation by two mechanisms (Figure 2c). In the first mechanism, macrophages assist the migration of tumor cells toward blood vessels through bidirectional paracrine signaling, termed the macrophage–tumor cell feedback loop [32,37,123]. Cancer cells secrete CSF1, which acts on CSFR+ macrophages. In turn, these macrophages secrete EGF, which acts on EGFR+ cancer cells. Intravital imaging of breast tumor xenografts demonstrate fast coordinated multicellular streaming of tumor cells in close proximity to blood vessels with evidence for macrophage–tumor cell pairing [37]. These streaming events appear to be mediated by paracrine signaling rather than by direct cell adhesion. In 3D culture, macrophages more efficiently remodel the matrix, enabling trailing breast carcinoma cells to invade into Matrigel [124,125]. Thus, macrophages could also assist in path generation. In addition, tumor macrophages promote dissemination of tumor cells into the vasculature by a second mechanism [39••]. Perivascular macrophages are in close proximity to tumor cells and vasculature and this tripartite arrangement has prognostic significance in breast cancers [126]. A recent study has identified a mechanism for this process that requires heterotypic direct cell–cell adhesion [39••]. Using an in vitro intravasation assay modeled by para-cellular tumor cell migration through an endothelial layer, direct physical contact between macrophages and tumor cells triggers RhoA-dependent invadopodia formation in tumor cells, and migration through the endothelium [39••].

There is an additional layer of control mediated by diverse cellular components of the innate and adaptive immune system [2,127–130]. Helper T cells and cytokine IL-4 induce macrophage polarization toward the TAM-phenotype, promoting invasion and metastasis [127,129]. Our present understanding is that these immune cells exert their effects primarily by paracrine signaling, rather than direct cell adhesion or ECM remodeling.

Tumor cell matrix interactions: involvement of collagen I ECM

Increased mammographic breast density is associated with significantly increased risk of developing invasive breast cancer and correlates with an increased ECM density [131–133]. The role of ECM as a conduit for cell interactions is highlighted by recent advances in our understanding of collagen I, an abundant ECM protein in invasive ductal carcinomas and in the MMTV-PyMT tumor model [14,134]. Increased collagen density is correlated with mammographic density [135], and collagen I gene expression has been identified in a gene signature of metastasis risk [136].

Both the supramolecular organization and orientation of collagen I are important (Figure 1c). The presence of aligned and straightened collagen fibers in breast cancer patient samples is an independent negative prognostic factor for disease-free survival [137]. Collagen alignment promotes directed cell migration along the axis of alignment [58,138,139], whereas in a model of pregnancy induced protection against breast cancer, nonlinearized collagen fibers are protective [140•]. Matrix cross-linking by lysyl oxidase further increase matrix stiffness and promotes tissue fibrosis, invasion and metastasis [59,141]. In addition to these effects on the physical scaffold, collagen I also activates multiple signaling pathways downstream of β1-integrin receptor, DDR receptor, and YAP-mediated mechanotransduction [53,54•,142,143].

Importantly, collagen I can acutely unmask invasive behavior as revealed by a recent study in a 3D organoid model of invasion [69••]. In this study, organoids isolated from both primary mouse and human mammary tumors grew non-protrusively when embedded in basement membrane-rich ECM [69••]. By contrast, tumor organoids invaded vigorously when embedded in 3D collagen I. Moreover, collagen I had the same pro-invasive effect when tumor organoids were embedded first in basement membrane-rich ECM and then transferred to collagen I several days later [69••]. Because basement membrane is progressively lost in the transition from in situ to invasive breast carcinomas [11], this study suggests that breaks in basement membrane could acutely induce invasion via direct contact between cancer cells and collagen I [69••].

Consistent with these data, many cells that participate in breast cancer invasion share in common the propensity to remodel collagen matrix. For example stromal fibroblasts are significantly increased in breast tumors [144] and exhibit increased synthesis of fibrillar collagens [145]. These cells typically express proteases such as MT1-MMP/MMP14 that enable them to degrade the ECM, lysyl oxidase that enable them to cross-link collagen I, and contractile myosins that enable them to efficiently align collagen matrix [28,117,146]. In turn, cells efficient at remodeling create tracks through which less migratory cancer cells can travel [106,112]. Based on the diversity of results in different experimental cancer models, it is likely that the cell types that accomplish matrix remodeling will vary between sub-types of breast tumors. In aggregate, these studies indicate that through multiple mechanisms, cells create durable changes in the tumor microenvironment that can have long-lasting effects on cancer cell behaviors.

Putting it together

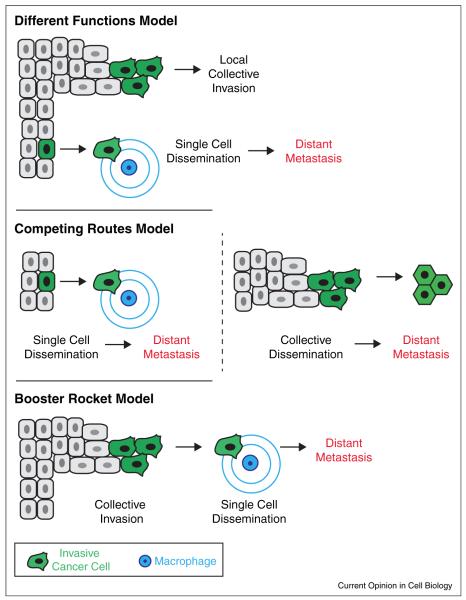

Collectively, these studies suggest multiple mechanisms operate in invasive breast tumors. In the MMTV-PyMT model, collective invasion, macrophage–tumor cell interactions, and tumor–cell interactions with collagen I ECM have been observed. So far the evidence across studies in the MMTV-PyMT model do not support a molecular EMT. However, even in this single model, it remains unresolved where, when, and how the different observed mechanisms intersect (Figure 3). One possible model is that these mechanisms execute different functions within the tumor (Model 1). Thus, collective invasion could promote local invasion whereas macrophage-led single cell dissemination could promote distant metastases. A second model is that these events represent competing pathways for metastatic spread (Model 2). Indeed there are studies to suggest that circulating tumor cell clusters are found in the bloodstream of breast cancer patients and that tumor emboli can efficiently seed metastatic sites [147,148]. A third model is that these mechanisms may reflect different stages of the invasive process (Model 3). In this scenario, collective invasion is a ‘booster-rocket’ that ultimately promotes single cell seeding and metastasis. Similarly, although interactions with collagen I are clearly important for primary tumor invasion, the importance of these interactions remains unclear in metastatic sites in which collagen I is less abundant. Additional studies to determine the requirements for collective invasion and the basal epithelial program in distant metastasis should help to tease apart the answers to these questions.

Figure 3.

An integrated model of invasion and metastasis in the MMTV-PyMT model. Three different models are possible. In the first model, collective invasion promotes local invasion whereas macrophage-led invasion promotes dissemination and distant metastasis. In the second model, metastases are generated by competing pathways that involve single cell and collective cell dissemination. In the third model, collective invasion greatly accelerates the metastatic process but metastasis obligately occurs through macrophage-led invasion and dissemination.

Cell interactions: a promising area for future research

In the past century, we have gained remarkable insight into the genes and pathways that become deranged in cancer cells [149]. However, these genes and pathways function in cancer cells that exist within a tissue and organ context [150]. An understanding of cell interactions will be important to provide a biological framework for understanding how this molecular parts list mediates cancer invasion and metastasis in a tissue context. In the invasion of breast tumors, key questions remain in these efforts: where do cells interact? Are there specific niche environments that matter for these interactions and can we recapitulate them ex vivo? What are the adhesion systems in these specific niche environments? How stable are these environments and can they be reverted? Is there one conserved route for metastasis or multiple? We expect that emerging experimental systems such as primary tumor organoids and intravital imaging will drive rapid progress toward understanding the cell interactions driving invasion and metastasis.

Acknowledgements

K.J.C. and A.J.E. thank Erik Sahai for crucial comments on the manuscript. K.J.C. is supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from the U.S. Department of Defense (W81XWH-12-1-0018 to K.J.C.) and a Burroughs Wellcome Fund Career Award for Medical Scientists. A.J.E. is supported by a Research Scholar Grant (RSG-12-141-01-CSM) from the American Cancer Society, by funds from the NIH/NCI (U01 CA155758), by a Jerome L. Greene Foundation Discovery Project, by a grant from the Mary Kay Ash Foundation (036-13), by funds from the Cindy Rosencrans Fund for Triple Negative Breast Cancer Research, and by a grant from the Breast Cancer Research Foundation.

References and recommended reading

Papers of particular interest, published within the period of review, have been highlighted as:

• of special interest

•• of outstanding interest

- 1.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63:11–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Egeblad M, Nakasone ES, Werb Z. Tumors as organs: complex tissues that interface with the entire organism. Develop Cell. 2010;18:884–901. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hunter K. Host genetics influence tumour metastasis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:141–146. doi: 10.1038/nrc1803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nguyen DX, Massague J. Genetic determinants of cancer metastasis. Nat Rev Genetics. 2007;8:341–352. doi: 10.1038/nrg2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coussens LM, Pollard JW. Leukocytes in mammary development and cancer. Cold Spring Harbor Persp Biol. 2011:3. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a003285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lu P, Weaver VM, Werb Z. The extracellular matrix: a dynamic niche in cancer progression. J Cell Biol. 2012;196:395–406. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201102147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weigelt B, Bissell MJ. Unraveling the microenvironmental influences on the normal mammary gland and breast cancer. Semin Cancer Biol. 2008;18:311–321. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2008.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wiseman BS, Werb Z. Stromal effects on mammary gland development and breast cancer. Science (New York, NY) 2002;296:1046–1049. doi: 10.1126/science.1067431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gray RS, Cheung KJ, Ewald AJ. Cellular mechanisms regulating epithelial morphogenesis and cancer invasion. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2010;22:640–650. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2010.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wellings SR, Jensen HM, Marcum RG. An atlas of subgross pathology of the human breast with special reference to possible precancerous lesions. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1975;55:231–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lerwill MF. Current practical applications of diagnostic immunohistochemistry in breast pathology. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28:1076–1091. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000126780.10029.f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Polyak K, Hu M. Do myoepithelial cells hold the key for breast tumor progression? J Mamm Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2005;10:231–247. doi: 10.1007/s10911-005-9584-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Allinen M, Beroukhim R, Cai L, Brennan C, Lahti-Domenici J, Huang H, et al. Molecular characterization of the tumor microenvironment in breast cancer. Cancer Cell. 2004;6:17–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2004.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Egeblad M, Rasch MG, Weaver VM. Dynamic interplay between the collagen scaffold and tumor evolution. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2010;22:697–706. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2010.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dvorak HF. Tumors: wounds that do not heal. Similarities between tumor stroma generation and wound healing. N Engl J Med. 1986;315:1650–1659. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198612253152606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hu M, Polyak K. Microenvironmental regulation of cancer development. Curr Opin Genetics Dev. 2008;18:27–34. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2007.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bhowmick NA, Chytil A, Plieth D, Gorska AE, Dumont N, Shappell S, et al. TGF-beta signaling in fibroblasts modulates the oncogenic potential of adjacent epithelia. Science (New York, NY) 2004;303:848–851. doi: 10.1126/science.1090922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Orimo A, Gupta PB, Sgroi DC, Arenzana-Seisdedos F, Delaunay T, Naeem R, et al. Stromal fibroblasts present in invasive human breast carcinomas promote tumor growth and angiogenesis through elevated SDF-1/CXCL12 secretion. Cell. 2005;121:335–348. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hu M, Peluffo G, Chen H, Gelman R, Schnitt S, Polyak K. Role of COX-2 in epithelial-stromal cell interactions and progression of ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:3372–3377. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813306106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pyne NJ, Pyne S. Sphingosine 1-phosphate and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:489–503. doi: 10.1038/nrc2875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21 ••.Luga V, Zhang L, Viloria-Petit AM, Ogunjimi AA, Inanlou MR, Chiu E, et al. Exosomes mediate stromal mobilization of autocrine Wnt-PCP signaling in breast cancer cell migration. Cell. 2012;151:1542–1556. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.11.024. This study reveals a novel mechanism for paracrine signaling in cancer invasion in which exosomes are the diffusible signal between fibroblasts and breast cancer cells.

- 22.Singh AB, Harris RC. Autocrine, paracrine and juxtacrine signaling by EGFR ligands. Cell Signal. 2005;17:1183–1193. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2005.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brachmann R, Lindquist PB, Nagashima M, Kohr W, Lipari T, Napier M, et al. Transmembrane TGF-alpha precursors activate EGF/TGF-alpha receptors. Cell. 1989;56:691–700. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90591-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wong ST, Winchell LF, McCune BK, Earp HS, Teixido J, Massague J, et al. The TGF-alpha precursor expressed on the cell surface binds to the EGF receptor on adjacent cells, leading to signal transduction. Cell. 1989;56:495–506. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90252-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Anklesaria P, Teixido J, Laiho M, Pierce JH, Greenberger JS, Massague J. Cell–cell adhesion mediated by binding of membrane-anchored transforming growth factor alpha to epidermal growth factor receptors promotes cell proliferation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:3289–3293. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.9.3289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shi W, Fan H, Shum L, Derynck R. The tetraspanin CD9 associates with transmembrane TGF-alpha and regulates TGF-alpha-induced EGF receptor activation and cell proliferation. J Cell Biol. 2000;148:591–602. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.3.591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dallas SL, Rosser JL, Mundy GR, Bonewald LF. Proteolysis of latent transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-beta)-binding protein-1 by osteoclasts. A cellular mechanism for release of TGF-beta from bone matrix. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:21352–21360. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111663200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kessenbrock K, Plaks V, Werb Z. Matrix metalloproteinases: regulators of the tumor microenvironment. Cell. 2010;141:52–67. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tatti O, Vehvilainen P, Lehti K, Keski-Oja J. MT1-MMP releases latent TGF-beta1 from endothelial cell extracellular matrix via proteolytic processing of LTBP-1. Exp Cell Res. 2008;314:2501–2514. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2008.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Muller A, Homey B, Soto H, Ge N, Catron D, Buchanan ME, et al. Involvement of chemokine receptors in breast cancer metastasis. Nature. 2001;410:50–56. doi: 10.1038/35065016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roussos ET, Condeelis JS, Patsialou A. Chemotaxis in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:573–587. doi: 10.1038/nrc3078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wyckoff J, Wang W, Lin EY, Wang Y, Pixley F, Stanley ER, et al. A paracrine loop between tumor cells and macrophages is required for tumor cell migration in mammary tumors. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7022–7029. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Giampieri S, Manning C, Hooper S, Jones L, Hill CS, Sahai E. Localized and reversible TGFbeta signalling switches breast cancer cells from cohesive to single cell motility. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:1287–1296. doi: 10.1038/ncb1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rajaram M, Li J, Egeblad M, Powers RS. System-wide analysis reveals a complex network of tumor–fibroblast interactions involved in tumorigenicity. PLoS Genetics. 2013;9:e1003789. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hu M, Yao J, Carroll DK, Weremowicz S, Chen H, Carrasco D, et al. Regulation of in situ to invasive breast carcinoma transition. Cancer Cell. 2008;13:394–406. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chaturvedi P, Gilkes DM, Wong CC, Luo W, Zhang H, Wei H, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor-dependent breast cancer-mesenchymal stem cell bidirectional signaling promotes metastasis. J Clin Investig. 2013;123:189–205. doi: 10.1172/JCI64993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Patsialou A, Wyckoff J, Wang Y, Goswami S, Stanley ER, Condeelis JS. Invasion of human breast cancer cells in vivo requires both paracrine and autocrine loops involving the colony-stimulating factor-1 receptor. Cancer Res. 2009;69:9498–9506. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Apostolopoulou M, Ligon L. Cadherin-23 mediates heterotypic cell–cell adhesion between breast cancer epithelial cells and fibroblasts. PloS One. 2012;7:e33289. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39 ••.Roh-Johnson M, Bravo-Cordero JJ, Patsialou A, Sharma VP, Guo P, Liu H, et al. Macrophage contact induces RhoA GTPase signaling to trigger tumor cell intravasation. Oncogene. 2013 doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.377. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/onc.2013.377. This study reveals a novel mechanism for intravasation in which direct cell–cell contact between macrophage and breast cancer cells induces RhoA activity and invadopodia induction.

- 40.Tamura D, Hiraga T, Myoui A, Yoshikawa H, Yoneda T. Cadherin-11-mediated interactions with bone marrow stromal/osteoblastic cells support selective colonization of breast cancer cells in bone. Int J Oncol. 2008;33:17–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41 ••.Friedl P, Locker J, Sahai E, Segall JE. Classifying collective cancer cell invasion. Nat Cell Biol. 2012;14:777–783. doi: 10.1038/ncb2548. This review outlines the defining cellular features of collective cancer invasion and describes experimental approaches to distinguish this process from other forms of invasion.

- 42.Bloom HJ, Richardson WW. Histological grading and prognosis in breast cancer; a study of 1409 cases of which 359 have been followed for 15 years. Br J Cancer. 1957;11:359–377. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1957.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Contesso G, Mouriesse H, Friedman S, Genin J, Sarrazin D, Rouesse J. The importance of histologic grade in long-term prognosis of breast cancer: a study of 1,010 patients, uniformly treated at the Institut Gustave-Roussy. J Clin Oncol. 1987;5:1378–1386. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1987.5.9.1378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Barton AA. An electron microscope study of human breast cells in fibroadenosis and carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 1964;18:682–685. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1964.78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Buehring GC, Hackett AJ. Human breast tumor cell lines: identity evaluation by ultrastructure. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1974;53:621–629. doi: 10.1093/jnci/53.3.621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cailleau R, Olive M, Cruciger QV. Long-term human breast carcinoma cell lines of metastatic origin: preliminary characterization. In Vitro. 1978;14:911–915. doi: 10.1007/BF02616120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Engel LW, Young NA, Tralka TS, Lippman ME, O’Brien SJ, Joyce MJ. Establishment and characterization of three new continuous cell lines derived from human breast carcinomas. Cancer Res. 1978;38:3352–3364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gabbiani G, Kapanci Y, Barazzone P, Franke WW. Immunochemical identification of intermediate-sized filaments in human neoplastic cells. A diagnostic aid for the surgical pathologist. Am J Pathol. 1981;104:206–216. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Keydar I, Chen L, Karby S, Weiss FR, Delarea J, Radu M, et al. Establishment and characterization of a cell line of human breast carcinoma origin. Eur J Cancer (Oxford, England: 1990) 1979;15:659–670. doi: 10.1016/0014-2964(79)90139-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Friedl P, Wolf K. Tumour-cell invasion and migration: diversity and escape mechanisms. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:362–374. doi: 10.1038/nrc1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lu P, Takai K, Weaver VM, Werb Z. Extracellular matrix degradation and remodeling in development and disease. Cold Spring Harbor Persp Biol. 2011:3. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a005058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Willis AL, Sabeh F, Li XY, Weiss SJ. Extracellular matrix determinants and the regulation of cancer cell invasion stratagems. J Microsc. 2013;251:250–260. doi: 10.1111/jmi.12064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Weaver VM, Petersen OW, Wang F, Larabell CA, Briand P, Damsky C, et al. Reversion of the malignant phenotype of human breast cells in three-dimensional culture and in vivo by integrin blocking antibodies. J Cell Biol. 1997;137:231–245. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.1.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54 •.Zhang K, Corsa CA, Ponik SM, Prior JL, Piwnica-Worms D, Eliceiri KW, et al. The collagen receptor discoidin domain receptor 2 stabilizes SNAIL1 to facilitate breast cancer metastasis. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15:677–687. doi: 10.1038/ncb2743. In this study, the authors identify a mechanism by which collagen I signaling through DDR2 receptor stabilizes SNAIL1 protein expression in invasive breast cancer cells that have undergone EMT, thereby promoting invasion and metastasis.

- 55 ••.Wolf K, Te Lindert M, Krause M, Alexander S, Te Riet J, Willis AL, et al. Physical limits of cell migration: control by ECM space and nuclear deformation and tuning by proteolysis and traction force. J Cell Biol. 2013;201:1069–1084. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201210152. This study defines important features of interstitial cancer cell migration under confinement and identifies nuclear deformation as an important parameter for crawling through tight spaces.

- 56.Haeger A, Krause M, Wolf K, Friedl P. Cell jamming: collective invasion of mesenchymal tumor cells imposed by tissue confinement. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1840:2386–2395. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2014.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57 ••.Tozluoglu M, Tournier AL, Jenkins RP, Hooper S, Bates PA, Sahai E. Matrix geometry determines optimal cancer cell migration strategy and modulates response to interventions. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15:751–762. doi: 10.1038/ncb2775. Cancer cells can demonstrate remarkable flexibility when invading through changing matrix geometries. In this study, computer simulation and experiment identify matrix geometries that favor adhesion-dependent F-actin protrusions or adhesion-independent cell blebbing driven cancer cell migration.

- 58.Provenzano PP, Eliceiri KW, Campbell JM, Inman DR, White JG, Keely PJ. Collagen reorganization at the tumor–stromal interface facilitates local invasion. BMC Med. 2006;4:38. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-4-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Levental KR, Yu H, Kass L, Lakins JN, Egeblad M, Erler JT, et al. Matrix crosslinking forces tumor progression by enhancing integrin signaling. Cell. 2009;139:891–906. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Guy CT, Cardiff RD, Muller WJ. Induction of mammary tumors by expression of polyomavirus middle T oncogene: a transgenic mouse model for metastatic disease. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:954–961. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.3.954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Herschkowitz JI, Simin K, Weigman VJ, Mikaelian I, Usary J, Hu Z, et al. Identification of conserved gene expression features between murine mammary carcinoma models and human breast tumors. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R76. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-5-r76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pfefferle AD, Herschkowitz JI, Usary J, Harrell JC, Spike BT, Adams JR, et al. Transcriptomic classification of genetically engineered mouse models of breast cancer identifies human subtype counterparts. Genome Biol. 2013;14:R125. doi: 10.1186/gb-2013-14-11-r125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lin EY, Nguyen AV, Russell RG, Pollard JW. Colony-stimulating factor 1 promotes progression of mammary tumors to malignancy. J Exp Med. 2001;193:727–740. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.6.727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Condeelis J, Segall JE. Intravital imaging of cell movement in tumours. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:921–930. doi: 10.1038/nrc1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Alexander S, Koehl GE, Hirschberg M, Geissler EK, Friedl P. Dynamic imaging of cancer growth and invasion: a modified skin-fold chamber model. Histochem Cell Biol. 2008;130:1147–1154. doi: 10.1007/s00418-008-0529-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Egeblad M, Ewald AJ, Askautrud HA, Truitt ML, Welm BE, Bainbridge E, et al. Visualizing stromal cell dynamics in different tumor microenvironments by spinning disk confocal microscopy. Disease Models Mech. 2008;1:155–167. doi: 10.1242/dmm.000596. discussion 65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sahai E. Illuminating the metastatic process. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:737–749. doi: 10.1038/nrc2229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68 ••.Cheung KJ, Gabrielson E, Werb Z, Ewald AJ. Collective invasion in breast cancer requires a conserved basal epithelial program. Cell. 2013;155:1639–1651. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.11.029. This study establishes that cooperative cell interactions between epithelial tumor cells drive collective invasion in vivo. A 3D organoid assay was developed to identify the most invasive cells in primary tumors; through this assay, a specialized subpopulation of cancer cells was identified that leads collective invasion across subtypes of breast cancer.

- 69 ••.Nguyen-Ngoc KV, Cheung KJ, Brenot A, Shamir ER, Gray RS, Hines WC, et al. ECM microenvironment regulates collective migration and local dissemination in normal and malignant mammary epithelium. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:E2595–E2604. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1212834109. This study reveals how local differences in ECM composition can either promote or inhibit the invasive behavior of breast cancer cells. Using a 3D organoid model, organoids from highly metastatic mammary tumors invade and disseminate vigorously into collagen I and not into basement membrane-rich ECM. Interestingly, invasive tumor organoids do not express molecular features of EMT by RNA expression analysis.

- 70.Dovas A, Patsialou A, Harney AS, Condeelis J, Cox D. Imaging interactions between macrophages and tumour cells that are involved in metastasis in vivo and in vitro. J Microsc. 2013;251:261–269. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2818.2012.03667.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ewald AJ. Isolation of mouse mammary organoids for long-term time-lapse imaging. Cold Spring Harbor Protoc. 2013;2013:130–133. doi: 10.1101/pdb.prot072892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fein MR, Egeblad M. Caught in the act: revealing the metastatic process by live imaging. Disease Models Mech. 2013;6:580–593. doi: 10.1242/dmm.009282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Entenberg D, Kedrin D, Wyckoff J, Sahai E, Condeelis J, Segall JE. Imaging tumor cell movement in vivo. Curr Protoc Cell Biol. 2013 doi: 10.1002/0471143030.cb1907s58. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/0471143030.cb1907s58. Chapter 19:Unit19.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Polyak K, Weinberg RA. Transitions between epithelial and mesenchymal states: acquisition of malignant and stem cell traits. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:265–273. doi: 10.1038/nrc2620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Thiery JP, Acloque H, Huang RY, Nieto MA. Epithelial– mesenchymal transitions in development and disease. Cell. 2009;139:871–890. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tsai JH, Yang J. Epithelial–mesenchymal plasticity in carcinoma metastasis. Genes Dev. 2013;27:2192–2206. doi: 10.1101/gad.225334.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kowalski PJ, Rubin MA, Kleer CG. E-cadherin expression in primary carcinomas of the breast and its distant metastases. Breast Cancer Res: BCR. 2003;5:R217–R222. doi: 10.1186/bcr651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Thiery JP. Epithelial–mesenchymal transitions in tumour progression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:442–454. doi: 10.1038/nrc822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hennessy BT, Gonzalez-Angulo AM, Stemke-Hale K, Gilcrease MZ, Krishnamurthy S, Lee JS, et al. Characterization of a naturally occurring breast cancer subset enriched in epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and stem cell characteristics. Cancer Res. 2009;69:4116–4124. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Prat A, Parker JS, Karginova O, Fan C, Livasy C, Herschkowitz JI, et al. Phenotypic and molecular characterization of the claudin-low intrinsic subtype of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res: BCR. 2010;12:R68. doi: 10.1186/bcr2635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Taube JH, Herschkowitz JI, Komurov K, Zhou AY, Gupta S, Yang J, et al. Core epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition interactome gene-expression signature is associated with claudin-low and metaplastic breast cancer subtypes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:15449–15454. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004900107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Prat A, Karginova O, Parker JS, Fan C, He X, Bixby L, et al. Characterization of cell lines derived from breast cancers and normal mammary tissues for the study of the intrinsic molecular subtypes. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;142:237–255. doi: 10.1007/s10549-013-2743-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Prat A, Perou CM. Deconstructing the molecular portraits of breast cancer. Mol Oncol. 2011;5:5–23. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2010.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Trimboli AJ, Fukino K, de Bruin A, Wei G, Shen L, Tanner SM, et al. Direct evidence for epithelial–mesenchymal transitions in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2008;68:937–945. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wicki A, Lehembre F, Wick N, Hantusch B, Kerjaschki D, Christofori G. Tumor invasion in the absence of epithelial–mesenchymal transition: podoplanin-mediated remodeling of the actin cytoskeleton. Cancer Cell. 2006;9:261–272. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86 ••.McCaffrey LM, Montalbano J, Mihai C, Macara IG. Loss of the Par3 polarity protein promotes breast tumorigenesis and metastasis. Cancer Cell. 2012;22:601–614. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.10.003. These two studies identify how loss of Par3 polarity protein promotes metastasis without loss of E-cadherin expression. In aggregate, these studies show that loss of cell polarity and the metastatic phenotype can be uncoupled from molecular EMT.

- 87 ••.Xue B, Krishnamurthy K, Allred DC, Muthuswamy SK. Loss of Par3 promotes breast cancer metastasis by compromising cell–cell cohesion. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15:189–200. doi: 10.1038/ncb2663. See annotation to Ref. [86••].

- 88 ••.Shamir ER, Pappalardo E, Jorgens DM, Coutinho K, Tsai WT, Aziz K, et al. Twist1-induced dissemination preserves epithelial identity and requires E-cadherin. J Cell Biol. 2014;204:839–856. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201306088. Invasive tumors are genetically complex and the minimal molecular requirements for single cell dissemination have been unclear. In this study, induction of Twist1 in normal mammary organoids is sufficient to induce delamination to single cells while retaining epithelial identity.

- 89.Glukhova M, Koteliansky V, Sastre X, Thiery JP. Adhesion systems in normal breast and in invasive breast carcinoma. Am J Pathol. 1995;146:706–716. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Moll R, Mitze M, Frixen UH, Birchmeier W. Differential loss of E-cadherin expression in infiltrating ductal and lobular breast carcinomas. Am J Pathol. 1993;143:1731–1742. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Oka H, Shiozaki H, Kobayashi K, Inoue M, Tahara H, Kobayashi T, et al. Expression of E-cadherin cell adhesion molecules in human breast cancer tissues and its relationship to metastasis. Cancer Res. 1993;53:1696–1701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Rakha EA, Abd El Rehim D, Pinder SE, Lewis SA, Ellis IO. E-cadherin expression in invasive non-lobular carcinoma of the breast and its prognostic significance. Histopathology. 2005;46:685–693. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2005.02156.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Gould Rothberg BE, Bracken MB. E-cadherin immunohistochemical expression as a prognostic factor in infiltrating ductal carcinoma of the breast: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006;100:139–148. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9248-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Li CI, Uribe DJ, Daling JR. Clinical characteristics of different histologic types of breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2005;93:1046–1052. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Bertos NR, Park M. Breast cancer — one term, many entities? J Clin Investig. 2011;121:3789–3796. doi: 10.1172/JCI57100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Berx G, Van Roy F. The E-cadherin/catenin complex: an important gatekeeper in breast cancer tumorigenesis and malignant progression. Breast Cancer Res: BCR. 2001;3:289–293. doi: 10.1186/bcr309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Derksen PW, Liu X, Saridin F, van der Gulden H, Zevenhoven J, Evers B, et al. Somatic inactivation of E-cadherin and p53 in mice leads to metastatic lobular mammary carcinoma through induction of anoikis resistance and angiogenesis. Cancer Cell. 2006;10:437–449. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Bukholm IK, Nesland JM, Borresen-Dale AL. Re-expression of E-cadherin, alpha-catenin and beta-catenin, but not of gamma-catenin, in metastatic tissue from breast cancer patients [see comments] J Pathol. 2000;190:15–19. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(200001)190:1<15::AID-PATH489>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Alpaugh ML, Tomlinson JS, Shao ZM, Barsky SH. A novel human xenograft model of inflammatory breast cancer. Cancer Res. 1999;59:5079–5084. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Colpaert CG, Vermeulen PB, Benoy I, Soubry A, van Roy F, van Beest P, et al. Inflammatory breast cancer shows angiogenesis with high endothelial proliferation rate and strong E-cadherin expression. Br J Cancer. 2003;88:718–725. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Kleer CG, van Golen KL, Braun T, Merajver SD. Persistent E-cadherin expression in inflammatory breast cancer. Modern Pathol. 2001;14:458–464. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3880334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Fernandez SV, Robertson FM, Pei J, Aburto-Chumpitaz L, Mu Z, Chu K, et al. Inflammatory breast cancer (IBC): clues for targeted therapies. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;140:23–33. doi: 10.1007/s10549-013-2600-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Friedl P, Gilmour D. Collective cell migration in morphogenesis, regeneration and cancer. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:445–457. doi: 10.1038/nrm2720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Friedl P, Noble PB, Walton PA, Laird DW, Chauvin PJ, Tabah RJ, et al. Migration of coordinated cell clusters in mesenchymal and epithelial cancer explants in vitro. Cancer Res. 1995;55:4557–4560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Hegerfeldt Y, Tusch M, Brocker EB, Friedl P. Collective cell movement in primary melanoma explants: plasticity of cell–cell interaction, beta1-integrin function, and migration strategies. Cancer Res. 2002;62:2125–2130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Gaggioli C, Hooper S, Hidalgo-Carcedo C, Grosse R, Marshall JF, Harrington K, et al. Fibroblast-led collective invasion of carcinoma cells with differing roles for RhoGTPases in leading and following cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:1392–1400. doi: 10.1038/ncb1658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Dang TT, Prechtl AM, Pearson GW. Breast cancer subtypespecific interactions with the microenvironment dictate mechanisms of invasion. Cancer Res. 2011;71:6857–6866. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-1818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108 ••.Calvo F, Ege N, Grande-Garcia A, Hooper S, Jenkins RP, Chaudhry SI, et al. Mechanotransduction and YAP-dependent matrix remodeling is required for the generation and maintenance of cancer-associated fibroblasts. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15:637–646. doi: 10.1038/ncb2756. The initiation and maintenance of the CAF phenotype are not well understood. This study elegantly synthesizes how the CAF phenotype evolves from a positive feedback loop involving progressive stiffness and YAP-activation.

- 109.Matise LA, Palmer TD, Ashby WJ, Nashabi A, Chytil A, Aakre M, et al. Lack of transforming growth factor-beta signaling promotes collective cancer cell invasion through tumor-stromal crosstalk. Breast Cancer Res: BCR. 2012;14:R98. doi: 10.1186/bcr3217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Marusyk A, Polyak K. Tumor heterogeneity: causes and consequences. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1805:105–117. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Carey SP, Starchenko A, McGregor AL, Reinhart-King CA. Leading malignant cells initiate collective epithelial cell invasion in a three-dimensional heterotypic tumor spheroid model. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2013;30:615–630. doi: 10.1007/s10585-013-9565-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Wolf K, Wu YI, Liu Y, Geiger J, Tam E, Overall C, et al. Multi-step pericellular proteolysis controls the transition from individual to collective cancer cell invasion. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:893–904. doi: 10.1038/ncb1616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Reffay M, Parrini MC, Cochet-Escartin O, Ladoux B, Buguin A, Coscoy S, et al. Interplay of RhoA and mechanical forces in collective cell migration driven by leader cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2014;16:217–223. doi: 10.1038/ncb2917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Rorth P. Fellow travellers: emergent properties of collective cell migration. EMBO Rep. 2012;13:984–991. doi: 10.1038/embor.2012.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115 •.Cheung WK, Zhao M, Liu Z, Stevens LE, Cao PD, Fang JE, et al. Control of alveolar differentiation by the lineage transcription factors GATA6 and HOPX inhibits lung adenocarcinoma metastasis. Cancer Cell. 2013;23:725–738. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.04.009. These two papers reveal that basal epithelial cytokeratins are associated with more invasive subtypes in both lung cancer and liver cancer and identify a requirement for basal cytokeratins in invasion in these tumor types.

- 116 •.Govaere O, Komuta M, Berkers J, Spee B, Janssen C, de Luca F, et al. Keratin 19: a key role player in the invasion of human hepatocellular carcinomas. Gut. 2014;63:674–685. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-304351. See annotation to Ref. [115•].

- 117.Pickup MW, Laklai H, Acerbi I, Owens P, Gorska AE, Chytil A, et al. Stromally derived lysyl oxidase promotes metastasis of transforming growth factor-beta-deficient mouse mammary carcinomas. Cancer Res. 2013;73:5336–5346. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-0012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118 •.Wang CC, Bajikar SS, Jamal L, Atkins KA, Janes KA. A time- and matrix-dependent TGFBR3-JUND-KRT5 regulatory circuit in single breast epithelial cells and basal-like premalignancies. Nat Cell Biol. 2014;16:345–356. doi: 10.1038/ncb2930. In this study, a powerful approach termed stochastic sampling is leveraged to identify two distinct gene expression states that exist in cells in organoid culture, one of which includes expression of the basal cytokeratin KRT5. Cells toggle between non-basal and basal states by a mechanism dependent on ECM engagement.

- 119.Condeelis J, Pollard JW. Macrophages: obligate partners for tumor cell migration, invasion, and metastasis. Cell. 2006;124:263–266. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Leek RD, Landers RJ, Harris AL, Lewis CE. Necrosis correlates with high vascular density and focal macrophage infiltration in invasive carcinoma of the breast. Br J Cancer. 1999;79:991–995. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Qian BZ, Pollard JW. Macrophage diversity enhances tumor progression and metastasis. Cell. 2010;141:39–51. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Tsutsui S, Yasuda K, Suzuki K, Tahara K, Higashi H, Era S. Macrophage infiltration and its prognostic implications in breast cancer: the relationship with VEGF expression and microvessel density. Oncol Rep. 2005;14:425–431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Wyckoff JB, Wang Y, Lin EY, Li JF, Goswami S, Stanley ER, et al. Direct visualization of macrophage-assisted tumor cell intravasation in mammary tumors. Cancer Res. 2007;67:2649–2656. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Guiet R, Van Goethem E, Cougoule C, Balor S, Valette A, Al Saati T, et al. The process of macrophage migration promotes matrix metalloproteinase-independent invasion by tumor cells. J Immunol (Baltimore, MD: 1950) 2011;187:3806–3814. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Hagemann T, Robinson SC, Schulz M, Trumper L, Balkwill FR, Binder C. Enhanced invasiveness of breast cancer cell lines upon co-cultivation with macrophages is due to TNF-alpha dependent up-regulation of matrix metalloproteases. Carcinogenesis. 2004;25:1543–1549. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgh146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Robinson BD, Sica GL, Liu YF, Rohan TE, Gertler FB, Condeelis JS, et al. Tumor microenvironment of metastasis in human breast carcinoma:apotentialprognosticmarkerlinkedtohematogenous dissemination. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:2433–2441. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.DeNardo DG, Barreto JB, Andreu P, Vasquez L, Tawfik D, Kolhatkar N, et al. CD4(+) T cells regulate pulmonary metastasis of mammary carcinomas by enhancing protumor properties of macrophages. Cancer Cell. 2009;16:91–102. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Fridlender ZG, Sun J, Kim S, Kapoor V, Cheng G, Ling L, et al. Polarization of tumor-associated neutrophil phenotype by TGF-beta: “N1” versus “N2” TAN. Cancer Cell. 2009;16:183–194. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Gocheva V, Wang HW, Gadea BB, Shree T, Hunter KE, Garfall AL, et al. IL-4 induces cathepsin protease activity in tumor-associated macrophages to promote cancer growth and invasion. Genes Dev. 2010;24:241–255. doi: 10.1101/gad.1874010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Nozawa H, Chiu C, Hanahan D. Infiltrating neutrophils mediate the initial angiogenic switch in a mouse model of multistage carcinogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:12493–12498. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601807103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Boyd NF, Guo H, Martin LJ, Sun L, Stone J, Fishell E, et al. Mammographic density and the risk and detection of breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:227–236. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa062790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.McCormack VA, dos Santos Silva I. Breast density and parenchymal patterns as markers of breast cancer risk: a meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prevention. 2006;15:1159–1169. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Wolfe JN. Risk for breast cancer development determined by mammographic parenchymal pattern. Cancer. 1976;37:2486–2492. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197605)37:5<2486::aid-cncr2820370542>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Pucci Minafra I, Luparello C, Sciarrino S, Tomasino RM, Minafra S. Quantitative determination of collagen types present in the ductal infiltrating carcinoma of human mammary gland. Cell Biol Int Rep. 1985;9:291–296. doi: 10.1016/0309-1651(85)90047-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Li T, Sun L, Miller N, Nicklee T, Woo J, Hulse-Smith L, et al. The association of measured breast tissue characteristics with mammographic density and other risk factors forbreastcancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prevention. 2005;14:343–349. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Ramaswamy S, Ross KN, Lander ES, Golub TR. A molecular signature of metastasis in primary solid tumors. Nat Genetics. 2003;33:49–54. doi: 10.1038/ng1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Conklin MW, Eickhoff JC, Riching KM, Pehlke CA, Eliceiri KW, Provenzano PP, et al. Aligned collagen is a prognostic signature for survival in human breast carcinoma. Am J Pathol. 2011;178:1221–1232. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2010.11.076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Provenzano PP, Inman DR, Eliceiri KW, Knittel JG, Yan L, Rueden CT, et al. Collagen density promotes mammary tumor initiation and progression. BMC Med. 2008;6:11. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-6-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Lyons TR, O’Brien J, Borges VF, Conklin MW, Keely PJ, Eliceiri KW, et al. Postpartum mammary gland involution drives progression of ductal carcinoma in situ through collagen and COX-2. Nat Med. 2011;17:1109–1115. doi: 10.1038/nm.2416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140 •.Maller O, Hansen KC, Lyons TR, Acerbi I, Weaver VM, Prekeris R, et al. Collagen architecture in pregnancy-induced protection from breast cancer. J Cell Sci. 2013;126:4108–4110. doi: 10.1242/jcs.121590. Early pregnancy is protective for risk of developing breast cancer. Surprisingly, the authors find that collagen I is elevated in parous matrix relative to non-parous matrix, but by SHG are less linearized and less stiff. In 3D culture, fibrillar collagen induces invasion whereas high-density non-fibrillar collagen matrices suppressed invasion.

- 141.Erler JT, Bennewith KL, Nicolau M, Dornhofer N, Kong C, Le QT, et al. Lysyl oxidase is essential for hypoxia-induced metastasis. Nature. 2006;440:1222–1226. doi: 10.1038/nature04695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Calvo F, Ege N, Grande-Garcia A, Hooper S, Jenkins RP, Chaudhry SI, et al. Mechanotransduction and YAP-dependent matrix remodeling is required for the generation and maintenance of cancer-associated fibroblasts. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15:637–646. doi: 10.1038/ncb2756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Paszek MJ, Zahir N, Johnson KR, Lakins JN, Rozenberg GI, Gefen A, et al. Tensional homeostasis and the malignant phenotype. Cancer Cell. 2005;8:241–254. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Elenbaas B, Weinberg RA. Heterotypic signaling between epithelial tumor cells and fibroblasts in carcinoma formation. Exp Cell Res. 2001;264:169–184. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.5133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Kauppila S, Stenback F, Risteli J, Jukkola A, Risteli L. Aberrant type I and type III collagen gene expression in human breast cancer in vivo. J Pathol. 1998;186:262–268. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(1998110)186:3<262::AID-PATH191>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Sabeh F, Li XY, Saunders TL, Rowe RG, Weiss SJ. Secreted versus membrane-anchored collagenases: relative roles in fibroblast-dependent collagenolysis and invasion. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:23001–23011. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.002808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Yu M, Stott S, Toner M, Maheswaran S, Haber DA. Circulating tumor cells: approaches to isolation and characterization. J Cell Biol. 2011;192:373–382. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201010021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Stott SL, Hsu CH, Tsukrov DI, Yu M, Miyamoto DT, Waltman BA, et al. Isolation of circulating tumor cells using a microvortex-generating herringbone-chip. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:18392–18397. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012539107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Bissell MJ, Radisky D. Putting tumours in context. Nat Rev Cancer. 2001;1:46–54. doi: 10.1038/35094059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Cardiff RD, Anver MR, Gusterson BA, Hennighausen L, Jensen RA, Merino MJ, et al. The mammary pathology of genetically engineered mice: the consensus report and recommendations from the Annapolis meeting. Oncogene. 2000;19:968–988. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Jonkers J, Derksen PW. Modeling metastatic breast cancer in mice. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2007;12:191–203. doi: 10.1007/s10911-007-9050-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Vargo-Gogola T, Rosen JM. Modelling breast cancer: one size does not fit all. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:659–672. doi: 10.1038/nrc2193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Sahai E. Mechanisms of cancer cell invasion. Curr Opin Genetics Dev. 2005;15:87–96. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]