Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the genetic findings, demographic features and clinical presentation of tumour necrosis factor receptor-associated autoinflammatory syndrome (TRAPS) in patients from the Eurofever/EUROTRAPS international registry.

Methods

A web-based registry collected retrospective data on patients with TNFRSF1A sequence variants and inflammatory symptoms. Participating hospitals included paediatric rheumatology centres and adult centres with a specific interest in autoinflammatory diseases. Cases were independently validated by experts in the disease.

Results

Complete information on 158 validated patients was available. The most common TNFRSF1A variant was R92Q (34% of cases), followed by T50M (10%). Cysteine residues were disrupted in 27% of cases, accounting for 39% of sequence variants. A family history was present in 19% of patients with R92Q and 64% of those with other variants. The median age at which symptoms began was 4.3 years but 9.1% of patients presented after 30 years of age. Attacks were recurrent in 88% and the commonest features associated with the pathogenic variants were fever (88%), limb pain (85%), abdominal pain (74%), rash (63%) and eye manifestations (45%). Disease associated with R92Q presented slightly later at a median of 5.7 years with significantly less rash or eye signs and more headaches. Children were more likely than adults to present with lymphadenopathy, periorbital oedema and abdominal pains. AA amyloidosis has developed in 16 (10%) patients at a median age of 43 years.

Conclusions

In this, the largest reported case series to date, the genetic heterogeneity of TRAPS is accompanied by a variable phenotype at presentation. Patients had a median 70 symptomatic days a year, with fever, limb and abdominal pain and rash the commonest symptoms. Overall, there is little evidence of a significant effect of age or genotype on disease features at presentation.

Keywords: Fever Syndromes, Inflammation, Amyloidosis

Introduction

The tumour necrosis factor receptor-associated periodic fever syndrome (TRAPS) was first described as familial Hibernian fever in 19821 but was renamed after the discovery that it is associated with mutations in the gene for tumour necrosis factor receptor superfamily member 1A (TNFRSF1A), on chromosome 12.2 3 It is now recognised as one of the hereditary recurrent fever syndromes, a group of autoinflammatory diseases caused by inappropriate activity of the innate immune system.4 5 Most sequence variants (SVs) underlying TRAPS lie within exons 2 to 4, and there appears to be over-representation of missense substitutions which disrupt structurally important cysteine–cysteine disulfide bonds in the extracellular domain (Infevers database: http://fmf.igh.cnrs.fr/ISSAID/infevers/).6–8 The mechanism(s) by which heterozygous TNFRSF1A SVs cause TRAPS remain(s) unclear and probably differ(s) between variants.9–13 The two commonest TNFRSF1A variants, P46L and R92Q, which are only associated with symptoms in a minority of people, are present in about 10% of West Africans and 2% of Caucasians, respectively.14 There is haplotype evidence of a common founder in R92Q5 and it may be a minor susceptibility factor for development of multiple sclerosis.15 The vast majority of carriers of these two variants are entirely well, and how they cause inflammatory disease in a minority remains obscure.

TRAPS is a very rare disease with an estimated prevalence of about one per million.16 It has been more frequently reported in Caucasians but whether this reflects true increased incidence or ascertainment bias is uncertain. TRAPS is a far less distinct disease entity than familial Mediterranean fever; attacks can be discrete or near continuous and are often prolonged, lasting several weeks and accompanied by a variety of features, including fever, abdominal pain, rash, eye manifestations, headache, pleuritic pain and lymphadenopathy.5 Symptoms are almost universally accompanied by a marked acute phase response and leucocytosis.

Diagnosis relies on clinical suspicion supported by genetic testing, but this has been severely hampered by the absence of any large-scale description of disease manifestations and by the absence of any validated diagnostic criteria.17 To further complicate the diagnosis, it is not known whether clinical features vary with age and thus if the disease presents differently in children. It is also unknown whether features at presentation predict the subsequent course of the disease and complications, or whether there is genotype-–phenotype correlation in relation to clinical presentation and/or severity.

The combined European Union-funded projects of Eurofever and EUROTRAPS sought to answer these questions by collecting data on large numbers of patients in a common registry.18 We here describe the clinical manifestations at presentation in 158 patients, of whom 53 were children (aged <18 at data collection) and 105 adults.

Patients and methods

The data analysed in this study were extracted from the Eurofever/EUROTRAPS registry (EAHC project numbers: 2007332 and 200923), which has been enrolling since November 2009.18 19 Ethical committee approval for entering patients in the registry and informed consent or assent was obtained in the participating countries according to local regulatory requirements.

Inclusion criteria were symptomatic inflammatory disease associated with a TNFRSF1A variant. Demographic information, clinical manifestations and laboratory findings at presentation were collected. Information about molecular genetic analysis was also collected, including the sequence variants found (Infevers database, http://fmf.igh.cnrs.fr/ISSAID/infevers/). Clinical details were sought about the features at disease onset rather than at diagnosis and included (i) characteristics of fever episodes (duration, frequency, triggers, etc), (ii) presence and frequency (always or often/sometimes) of clinical manifestations. All completed cases were anonymously and independently validated by at least one expert in the disease (HJL, PW, MG) in order to confirm the diagnosis. This analysis includes all cases validated before June 2012.

Statistics

Frequencies and percentages were used as descriptive statistics for categorical variables. To describe numerical variables median and range were used. Differences among groups were assessed by Mann–Whitney U test or Kruskal–Wallis test when evaluating continuous variables and by χ2 tests for discrete variables. Post hoc analysis between groups was performed by Mann–Whitney U test or χ2 test; no adjustments for multiple comparisons were performed. In order to analyse the clinical phenotype of the patients according to the type of gene variants, we divided the patients into three subgroups: (A) patients carrying cysteine or T50M variants, (B) patients with other variants and (C) patients with the low-penetrance variants R92Q and P46L.

Results

Demographic data

In June 2012, 224 patients with TRAPS were available in the registry. Of these, 59 patients were excluded as only baseline demographic data without clinical information were available, and seven patients were excluded at the validation stage. None of these had mutations detected in TNFRSF1A, four had no specific symptoms, one responded well to broad-spectrum immunosuppressant agents with extremely short attacks of systemic inflammation, one had recurrent pericarditis and the final patient had a new NLRP3 mutation and non-specific mild symptoms. A total of 158 analysed patients were enrolled by 18 centres in 11 countries. All patients but one were enrolled by European centres: UK (64 patients), Italy (38), France (17), Germany (16), Spain (8), Netherlands (6), Ireland (4), Greece (2), Slovenia (1) and Turkey (1). One patient born in the UK was enrolled in Australia. Eight patients had immigrated to the country of the referral centre and originated from Portugal, Slovakia, Canada, the Congo, Nigeria, Mauritius, Kuwait and Iraq. Most of the patients (147, 93%) were European Caucasians. Four were Arab originating from the Middle East or North Africa; three were sub-Saharan African and two South Asians. Two patients had a mixed origin: Caucasian/Asian and Caucasian/African, respectively.

Demographic details are summarised in table 1. The median age at enrolment was 33.8 years (range 3–77). The majority of the patients were adults (105, 66%). Fifty-three patients (34%) were children or adolescents aged <18 years. Across the whole cohort the median age at symptom onset was 4.3 years (range 0.2–63); it was 4 years (range 0–49) in patients with a SV and a median of 5.7 years (range 0–53) in patients with R92Q (not significant). Development of symptoms after the age of 30 years was seen in 9.1% of patients with no difference between those with low-penetrant variants and those carrying other SVs. Median disease duration at enrolment was 15.6 years, in the children it was 6.6 years and in adults 27.7 years. The median age at diagnosis with TRAPS for the whole group was 25.9 years; children were diagnosed at 6.2 years; whereas diagnosis in adults was at a median of 37.9 years, reflecting a median diagnostic delay of 10.3 years, which was almost 10 times higher than in the study paediatric patients.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of patients with TRAPS at the time of enrolment

| Characteristics | Whole TRAPS population | Paediatric patients | Adult patients |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 158 | 53 | 105 |

| Male:female | 78:80 | 31:22 | 47:58 |

| Age at onset (years) | 4.3 (0–63) | 1.5 (0–13) | 8 (0–63) |

| Age at diagnosis (years) | 25.9 (0–77) | 6.2 (0–15) | 37.9 (1–77) |

| Age at enrolment (years) | 33.8 (3–77) | 11.2 (3–18) | 42.3 (19–77) |

| Diagnostic delay (years) | 10.3 (0–77) | 2.7 (0–14) | 22.4 (0–77) |

| Disease duration (years) | 15.6 (1–77) | 6.6 (1–17) | 27.7 (1–77) |

| Disease onset at <18 years, n (%) | 123 (78) | 53 | 70 (67) |

| Disease onset aged ≥18 years, n (%) | 35 (22) | – | 35 (33) |

Results are shown as median (range) unless stated otherwise.

Genotypic characterisation

All patients had SVs in TNFRSF1A. Sequencing of the whole gene was performed in nine patients (6%) and a search for a single mutation was performed in five patients (3%). In the majority of patients (134, 85%) selected exons, mainly from 1 to 4, had been analysed. In total 46 variants were found, the complete list is reported in table 2. The vast majority of the patients were heterozygous for missense mutations involving exon 2 (29 patients), exon 3 (59 patients) and exon 4 (64 patients). Five patients carried variants in non-coding intronic regions of the gene. One patient displayed a large deletion in exon 6. Only 19 variants (41.3%) were identified in more than one unrelated individual.

Table 2.

The TNFRSF1A variants in the 158 patients

| Variant (protein variant) | Location | Number of cases (%) | Ethnicity |

|---|---|---|---|

| D12E (p.Asp41Glu) | Exon 2 | 3 (2) | Caucasian |

| H22Q (p.His51Gln) | 2 (1) | Caucasian | |

| H22R (p.His51Arg) | 3 (2) | Caucasian | |

| C29F (p.Cys58Phe) | 1 (0.5) | Caucasian | |

| C29Y (p.Cys58Tyr) | 1 (0.5) | Asian | |

| C30F (p.Cys59Phe) | 1 (0.5) | Caucasian | |

| C30R (p.Cys59Arg) | 4 (3) | Caucasian | |

| C30Y (p.Cys59Tyr) | 1 (0.5) | Caucasian | |

| C33G (p.Cys62Gly) | 1 (0.5) | Arab | |

| C33Y (p.Cys62Tyr) | 12 (8) | Caucasian | |

| c.193-14G>A | Intron 2 | 1 (0.5) | Caucasian |

| c.194-15C>T | 1 (0.5) | Caucasian | |

| T37I (p.Thr66Ile) | Exon 3 | 2 (1) | Arab |

| 1 (0.5) | Caucasian | ||

| Y38S (c.200A>C) | 1 (0.5) | Caucasian | |

| L39F (p.Leu68Phe) | 4 (3) | Caucasian | |

| D42DEL (p.Asp71del) | 1 (0.5) | Caucasian | |

| C43G (c214T>G) | 3 (2) | Caucasian | |

| C43R (p.Cys72Arg) | 1 (0.5) | Caucasian | |

| C43S (p.Cys72Ser) | 1 (0.5) | Caucasian | |

| C43Y (p.Cys72Tyr) | 5 (3) | Arab, Sub-Saharan African×2, Caucasian×2 | |

| P46L (p.Pro75Leu) | Caucasian | ||

| Caucasian×15, African×1 | |||

| T50K (p.Thr79Lys) | 2 (1) | Caucasian Caucasian×3, Arab×1 | |

| T50M (p.Thr79Met) | 16 (10) | Caucasian | |

| Caucasian | |||

| C52Y (p.Cys81Tyr) | 5 (3) | Caucasian | |

| C55Y (p.Cys84Tyr) | 4 (3) | Caucasian | |

| Caucasian | |||

| S59P (p.Ser88Pro) | 1 (0.5) | Caucasian | |

| F60L (p.Phe89Leu) | 2 (1) | Caucasian | |

| T61N (p.Thr90Asn) | 2 (1) | ||

| N65I (p.Asn94Ile) | 2 (1) | Caucasian | |

| H66L (p.His95Leu) | 1 (0.5) | Caucasian | |

| L67P (p.Leu96Pro) | 1 (0.5) | ||

| H69fs (p.His98_Cys99delinsArg) | 1 (0.5) | ||

| C73R (p.Cys102Arg) | |||

| C73W (p.Cys102Trp) | 1 (0.5) | ||

| 2 (1) | |||

| C88Y (p.Cys117Tyr) | Exon 4 | 1 (0.5) | Caucasian |

| R92P (p.Arg121Pro) | 1 (0.5) | Caucasian | |

| R92Q (p.Arg121Gln) | 54 (34) | Caucasian | |

| V95M (p.Val124Met) | 2 (1) | Caucasian | |

| C96Y (p.Cys125Tyr) | 1 (0.5) | Caucasian | |

| Y103_R104DEL (p.Tyr132_Arg133del) | 1 (0.5) | Caucasian | |

| E109A (p.Glu138Ala) | |||

| C114W (p.Cys143Trp | 2 (1) | Caucasian | |

| N116S (p.Asn145Ser) | 1 (0.5) | Caucasian | |

| 1 (0.5) | Caucasian | ||

| c.472+6C>T | Intron 4 | 2 (1) | Caucasian |

| L167_G175del (c.586_612del127 | Exon 6 | 1 (0.5) | Asian |

| Intronic substitution c626-32G>T | Intron 6 | 1 (0.5) | Caucasian |

The distribution of the genotype according to age and disease onset is shown in table 3. T50M was the single commonest variant, found in 16 patients including five unrelated kindreds from five different countries. Eighteen different variants involving cysteine residues were found in 42 patients. In 30 patients (19%) other missense variants previously reported to be associated with a TRAPS phenotype were seen (Infevers: http://fmf.igh.cnrs.fr/ISSAID/infevers/); another 12 patients carried variants for which the association with the clinical phenotype had not previously been considered certain. The low-penetrant variants, R92Q and P46L, were found in 54 and five patients, respectively. Four of the P46L cases also had sequencing of additional fever genes; MEFV in three cases, and MEFV, NLRP3 and MVK in the other with no variants found. Of the patients carrying R92Q, 24 patients underwent additional sequencing: MEFV in 22 cases, MVK in 11 and NLRP3 in two. Two patients were found to carry MEFV variants, one case each of E148Q and R121Q.

Table 3.

Major groups of genetic variants in the different age groups of patients with TRAPS

| Whole TRAPS population | Paediatric patients | Adults with paediatric onset | Adults with adult onset | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number (%) | Number (%) | Number (%) | Number (%) | |

| Sequence variants involving a cysteine residue or T50M | 58 (37) | 14 (26) | 26 (37) | 8 (23) |

| Other sequence variants | 41 (26) | 12 (23) | 19 (27) | 10 (29) |

| R92Q or P46L | 59 (37) | 27 (51) | 15 (21) | 17 (49) |

| Total number of patients (% of total) | 158 (100) | 53 (34) | 70 (44) | 35 (22) |

In adult patients a SV involving T50M or a cysteine residue was seen in 26 (51%) of those with disease onset in childhood and eight patients (22.9%) with an adult onset (p<0.001). Conversely, in the adults in this study the prevalence of the low-penetrant variants, R92Q and P46L, was twice as high in those with an adult onset (49%) compared with those with a paediatric onset (21%) (p<0.001). In paediatric patients the distribution of mutation types was similar to that seen in adult-onset TRAPS (table 3). A family history of TRAPS was reported by 11 (19%) patients with the lower-penetrance R92Q variant. In patients with other SVs 64% had a suggestive family history, and this was exactly the same in the subgroup of T50M and variants involving a cysteine residue.

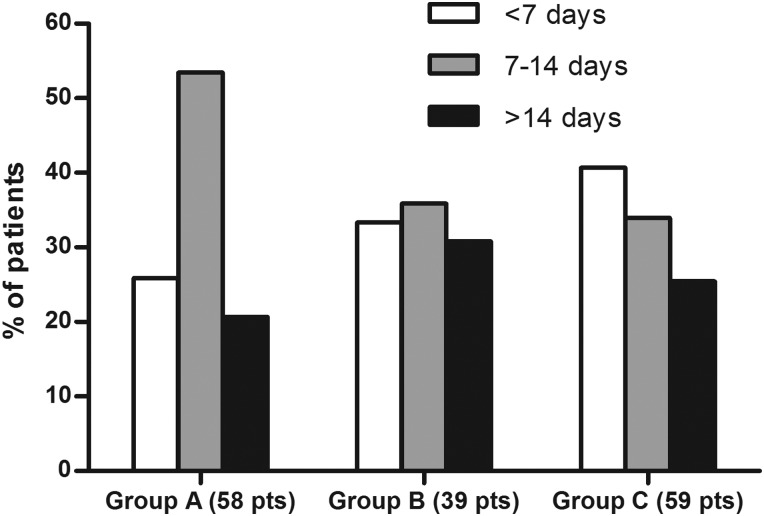

Clinical features at presentation

At presentation 139 patients (88%) reported that their symptoms occurred in recurrent episodes and only 11 (7%) had continuous symptoms (three C33Y, two C73W, five R92Q, one P46L) (table 4). In the remaining eight patients disease was continuous with episodic flares. The disease burden was high with an average of 70 symptomatic days a year. Median attack duration was 10.8 days for the whole cohort with no significant differences in the duration or number of attacks between the paediatric and adult populations. There was considerable variation in attack duration with a third of attacks lasting less than a week, shorter attacks were more frequent in patients with low-penetrance SVs, accounting for 40% compared with 26% in patients with mutations affecting T50M or cysteine residues (p<0.05) (figure 1). Only 12% of patients reported regular predictable attacks, but these were commoner in paediatric patients than in adults (26.4% and 4.8% respectively, p<0.05). Just over a quarter of patients (40 cases) could identify triggers for their attacks. The commonest reported triggers were emotional stress (21 patients); menstrual cycle (17); fatigue (10); infections (9); exercise (7) and vaccinations (6). There were no significant differences between the incidence and type of triggers in children and adults except for the entirely explicable findings that vaccination and infections were reported more commonly in children (who are more exposed to them) and the menstrual cycle in females after menarche. A fever of >38°C was reported by 83.5% of patients with no difference between adult and paediatric cases, and rigours occurred in 30%.

Table 4.

Characteristics of fever episodes according to the age and disease onset

| Whole TRAPS population | Paediatric patients | Adults with paediatric onset | Adults with adult onset | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n=158) | (n=53) | (n=70) | (n=35) | |

| Number of patients | Number (%) | Number (%) | Number (%) | Number (%) |

| Disease course | ||||

| Recurrent* | 139 (88) | 48 (91) | 57 (81) | 34 (97) |

| Continuous† | 11 (7) | 4 (8) | 6 (9) | 1 (3) |

| Continuous with flares | 8 (5) | 1 (2) | 7 (10) | 0 |

| Characteristics of the disease episodes | ||||

| Duration | ||||

| >14 days | 32 (25) | 10 (24) | 14 (24) | 8 (27) |

| 7–14 days | 55 (43) | 18 (43) | 26 (46) | 11 (37) |

| <7 days | 42 (33) | 14 (33) | 17 (29) | 11 (37) |

| Mean duration (days) | 10.8 | 10.7 | 10.9 | 10.9 |

| Mean number of episodes/year | 7.7 | 7.7 | 7.6 | 6.9 |

| Fever (>38°C) | 132 (84) | 48 (91) | 56 (80) | 28 (80) |

| Low-grade fever (<38°C) | 57 (36) | 16 (30) | 27 (39) | 14 (40) |

| Rigours/chills at fever onset | 48 (30) | 18 (34) | 25 (36) | 5 (14) |

| Pattern of attacks | ||||

| Irregular | 91 (58) | 32 (60) | 39 (56) | 20 (57) |

| Regular | 19 (12) | 14 (26) | 4 (6) | 1 (3) |

| Seasonal changes | 4 (2.5) | 1 (3) | 3 (4) | 0 |

| Triggers | 40 (25) | 15 (28) | 19 (27) | 6 (17) |

*Recurrent manifestations with disease-free intervals.

†Continuous/subchronic manifestations with possible episodic flares.

Figure 1.

Duration of the episodes according to the major groups of genetic variants in patients with TRAPS expressed as a percentage of attacks. Group A patients carry a sequence variant involving a cysteine residue or T50M; group B patients carry other sequence variants; group C patients carry R92Q or P46L.

The most common symptoms accompanying episodes are reported in table 5. The dominant classes of symptoms: fever, limb pain, abdominal pain and rash were seen in 88%, 85%, 74% and 63% of patients with clear-cut variants; and 94%, 79%, 64% and 30% of patients with the R92Q variant, respectively. Periorbital oedema, a pathognomic feature of TRAPS was seen in 20% of the whole cohort. Comparison of the different variant groups ((A) variants affecting cysteine residues and T50M, (C) the low-penetrance variants R92Q and P46L and (B) all other SVs) showed remarkably few differences which reached significance. Patients in groups A and B were more likely than patients with R92Q to have a rash (63% vs 30% (p<0.001)) and eye symptoms (45% vs 26% (p<0.05)). Patients with R92Q had significantly more headaches (40% vs 13% (p<0.001) and a non-significant trend towards more oropharyngeal symptoms (30% vs 19%) (table 5).

Table 5.

Clinical manifestations reported in patients with TRAPS at disease presentation by age and mutation group

| Whole TRAPS population | Pediatric patients (A) | Adults with pediatric onset (B) | Adults with adult onset (C) | Cysteine or T50M (D) | Other mutations (E) | Low-penetrance mutations (F) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n=158) | (n=53) | (n=70) | (n=35) | (n=58) | (n=39) | (n=59) | |||

| Number of patients | Number (%) | Number (%) | Number (%) | Number (%) | p Value* | Number (%) | Number (%) | Number (%) | p Value* |

| Mucocutaneous | |||||||||

| Exudative pharyngitis | 5 (3) | 3 (6) | 1 (1.5) | 1 (3) | NS | 2 (3) | 0 | 3 (5) | NS |

| Erythematous pharyngitis | 28 (18) | 12 (23) | 11 (16) | 5 (14) | NS | 7 (12) | 7 (18) | 14 (24) | NS |

| Aphthous stomatitis | 15 (9.5) | 7 (13) | 4 (6) | 4 (11) | NS | 3 (5) | 4 (10) | 8 (14) | NS |

| Palpable purpura | 1 (0.5) | 1 (2) | 0 | 0 | NS | 0 | 0 | 1 (2) | NS |

| Maculopapular rash | 41 (26) | 17 (32) | 17 (24) | 7 (20) | NS | 14 (24) | 15 (38) | 12 (20) | NS |

| Urticarial rash | 39 (25) | 12 (23) | 20 (29) | 7 (20) | NS | 15 (26) | 11 (28) | 13 (22) | NS |

| Migratory rash | 28 (18) | 9 (17) | 16 (23) | 3 (9) | NS | 16 (28)* | 7 (18) | 5 (8) | 0.01 |

| Erysipelas-like erythema | 7 (4) | 1 (2) | 6 (9) | 0 | 0.04 | 6 (10)† | 0 | 1 (2) | 0.03 |

| Localised erythema | 4 (2.5) | 1 (2) | 2 (3) | 1 (3) | NS | 0 | 2 (5) | 2 (3) | NS |

| Generalised erythema | 3 (2) | 1 (2) | 1 (1.5) | 1 (3) | NS | 0 | 1 (3) | 2 (3) | NS |

| Pseudo-folliculitis | 3 (2) | 1 (2) | 1 (1.5) | 1 (3) | NS | 0 | 1 (3) | 2 (3) | NS |

| Musculoskeletal | |||||||||

| Arthralgia | 101 (64) | 34 (64) | 48 (69) | 19 (54) | NS | 34 (58) | 28 (72) | 39 (66) | NS |

| Myalgia | 111 (70) | 36 (68) | 53 (76) | 22 (63) | NS | 43 (74) | 29 (74) | 39 (66) | NS |

| Myositis | 3 (1.5) | 1 (2) | 2 (3) | 0 | NS | 3 (5) | 0 | 0 | 0.04 |

| Fasciitis | 6 (4) | 0* | 5 (7) | 1 (3) | 0.04 | 4 (7) | 1 (3) | 1 (2) | NS |

| Bone pain | 6 (4) | 2 (4) | 2 (3) | 2 (6) | NS | 2 (3) | 0 | 4 (7) | NS |

| Monoarthritis | 9 (6) | 4 (8) | 2 (3) | 2 (4) | NS | 4 (7) | 1 (3) | 4 (7) | NS |

| Oligoarthritis | 15 (9.5) | 2 (4) | 9 (13) | 4 (11) | NS | 8 (14) | 2 (5) | 5 (8) | NS |

| Polyarthritis | 2 (4) | 1 (1.2) | 2 (3) | 5 (14) | 0.04 | 2 (3) | 1 (3) | 1 (2) | NS |

| Ocular | |||||||||

| Periorbital oedema | 32 (20) | 8 (15) | 21 (30) | 2 (4) | NS | 14 (24) | 8 (20) | 10 (17) | NS |

| Periorbital pain | 20 (13) | 6 (11) | 10 (14) | 4 (11) | NS | 12 (21)* | 2 (5) | 6 (10) | 0.03 |

| Conjunctivitis | 35 (22) | 6 (11) | 23 (33) | 6 (17) | NS | 18 (31)† | 17 (44)‡ | 10 (17) | 0.02 |

| Gastrointestinal | |||||||||

| Vomiting | 28 (18) | 13 (25) | 9 (13) | 6 (17) | NS | 6 (10) | 7 (18) | 15 (26) | NS |

| Abdominal pain | 110 (70) | 38 (72) | 53 (76)‡ | 19 (54) | 0.05 | 47 (81) | 27 (69) | 36 (61) | NS |

| Constipation | 21 (13) | 2 (3.8)*† | 12 (17) | 7 (20) | 0.01 | 13 (22)* | 2 (5) | 6 (10) | 0.02 |

| Diarrhoea | 28 (18) | 12 (23) | 10 (14) | 6 (17) | NS | 11 (19) | 7 (18) | 10 (17) | NS |

| GI bleeding | 3 (1.5) | 0 | 1 (1.5) | 2 (6) | NS | 3 (5.1) | 0 | 1 (2) | NS |

| Aseptic peritonitis | 10 (6) | 0 | 9 (13) | 1 (3) | 0.01 | 5 (9) | 2 (5) | 3 (5) | NS |

| Lymphoid organs | |||||||||

| Generalised enlargement | 12 (8) | 6 (11) | 5 (7) | 1 (3) | NS | 5 (9) | 3 (8) | 4 (7) | NS |

| Enlarged cervical lymph nodes | 41 (26) | 23 (43) | 15 (21) | 2 (4) | 0.01 | 16 (28) | 10 (26) | 15 (25) | NS |

| Inguinal lymphadenopathy | 2 (1) | 1 (2) | 0 | 1 (3) | NS | 0 | 0 | 2 (3) | NS |

| Lymph node pain | 21 (13) | 10 (19) | 10 (14) | 1 (3) | NS | 9 (16) | 5 (13) | 7 (12) | NS |

| Hepatomegaly | 9 (6) | 5 (9) | 4 (6) | 0 | NS | 4 (7) | 3 (8) | 2 (3) | NS |

| Splenomegaly | 12 (8) | 6 (11) | 4 (6) | 2 (6) | NS | 3 (5) | 5 (13) | 4 (7) | NS |

| Cardiorespiratory | |||||||||

| Chest pain | 40 (25) | 7 (13)*† | 17 (24)‡ | 16 (46) | 0.002 | 13 (22) | 14 (36) | 13 (22) | NS |

| Pericarditis | 11 (7) | 1 (2)† | 2 (3)‡ | 8 (23) | 0.001 | 0*† | 5 (13) | 6 (10) | 0.005 |

| Pleurisy | 19 (12) | 1 (2)*† | 8 (11) | 10 (29) | 0.001 | 3 (5)* | 10 (26) | 6 (10) | 0.02 |

| Pneumonia | 2 (1) | 1 (2) | 0 | 1 (3) | NS | 0 | 2 (5) | 0 | NS |

| Persistent cough | 7 (4) | 0*† | 4 (6) | 3 (9) | 0.03 | 3 (5) | 1 (3) | 3 (5) | NS |

| Neurological | |||||||||

| Headache | 36 (23) | 17 (32) | 10 (14) | 9 (26) | NS | 5 (9)*† | 8 (21) | 23 (39) | 0.001 |

| Seizures | 2 (1) | 1 (2) | 1 (1.5) | 0 | NS | 1 (2) | 0 | 1 (2) | NS |

| Vertigo | 2 (1) | 2 (4) | 0 | 0 | NS | 0 | 0 | 0 | NS |

| Genitourinary | |||||||||

| Gonadal pain | 4 (3) | 0 | 4 (6) | 0 | NS | 1 (2) | 2 (5) | 1 (2) | NS |

| Amyloidosis | 16 (10) | 1 (2)* | 13 (18) | 2 (6) | 0.003 | 8 (16)* | 7 (18)‡ | 1 (2) | 0.008 |

p, Pearson χ2 for heterogeneity.

Post hoc analysis for pairwise comparison for age of onset: *group A versus group B, p<0.05; †group A versus C p<0.05; ‡group B versus group C, p<0.05.

Post hoc analysis for pairwise comparison for genotype: *group D versus group E, p<0.05; †group D versus group F, p<0.05; ‡group E versus group F, p<0.05.

A comparison of patients who presented in childhood (the 53 paediatric patients and 70 adult patients with childhood onset) with the 30 adult patients (with first symptoms after the age of 18 years) showed that the only significant differences were cervical lymphadenopathy, which was present in 31% of attacks presenting in childhood and 9% of adults; periorbital oedema and abdominal pain were also commoner in childhood presentation occurring in 24% and 74%, respectively (p<0.05). Only chest pain with attacks was significantly more frequent in adult presentation, occurring in 54% compared with 20% in childhood (p<0.05); in general, chest pain was most frequent in patients with T50M (6/16 cases), although they reported neither pericarditis nor pleurisy (table 5).

AA amyloidosis occurred in 16 cases (10%) at a median age of 43 years (range 20–77). This group included seven cysteine variants (44%), two T50M (13%) and no patients with R92Q. Patients who developed AA amyloidosis had significantly longer disease duration than those who did not (39 vs 19.4 years (p<0.001) and 13 of the 16 cases had their first symptoms in childhood.

Discussion

This is the largest reported series of patients with symptoms and confirmed variants in the TNFRSF1A gene and shows the strength of international cooperation in the study of an extremely uncommon condition which can present to a wide variety of specialties, and to both paediatric and adult services. The diagnosis of very rare diseases relies on a high ‘index of suspicion’ followed by specific testing. In diseases where the diagnostic test is both expensive and of limited availability we hope that definition of what constitutes a ‘target group’ will facilitate early recognition of probable cases and appropriate use of limited resources. These results show that TRAPS is a pleiomorphic condition characterised by attacks of fever in >83% accompanied by symptoms including diffuse limb pain, abdominal pain and rash. In many respects our data confirm the case descriptions from earlier publications,5 20–24 but it is also important to recognise that by no means all patients fall into a tightly circumscribed phenotype. In particular, despite its autosomal dominant nature, a family history of TRAPS is reported by fewer than two-thirds of patients, and symptoms begin after the age of 18 years in 22%. In addition, although the average disease attack lasts for >10 days, 30% last for less than a week, and hence brief febrile episodes cannot be used to exclude the diagnosis.

The size of this series allows, for the first time, an exploration of genotype–phenotype associations and also of the effect of patient age on disease features at presentation. Mutations affecting cysteine residues and the T50M variant were among the first identified in TRAPS.25 They have been widely regarded as associated with higher penetrance, a more severe disease phenotype and a high risk of AA amyloidosis. Our series includes 58 such patients and has found that a family history was no commoner in them than in other non-R92Q P46L sequence variants, but that their disease was more likely to persist into adulthood. No particular pattern of clinical features was commoner in patients with these sequence variants, and they did not appear to be over-represented among patients who developed AA amyloidosis.

Analysis of patients with the R92Q variant showed that these patients had a slightly different disease phenotype, with a lower proportion of familial disease, more headaches and fewer rash and eye manifestations. The lower percentage in adult patients with paediatric onset compared with both the children and patients who presented in adulthood, suggests that manifestation of R92Q-associated disease tends to be either as febrile attacks in children, which ameliorate as they mature, or as a genuinely later-onset disease. Both these clinical scenarios are consistent with a milder phenotype,26 and certainly no patients with R92Q have developed the most feared complication of TRAPS, AA amyloidosis.27 The role of low-penetrance variants in TRAPS disease aetiology has long been contentious. It remains possible that TNFRSF1A R92Q is simply acting as a modifier in patients with other, as yet, unidentified causes of an inflammatory phenotype. In this series 24 (44%) patients had undergone sequencing of at least one other fever gene with only two cases found to carry the equally controversial MEFV sequence variants E148Q and R121Q, suggesting that we were not missing other common clear-cut inherited autoinflammatory conditions. The very high proportion of patients with R92Q in this series supports the view that R92Q-associated disease is a genuine phenomenon, although one that affects only a minority of carriers. Our results are more equivocal for P46L. We recruited only five patients; two of these were Caucasian but the other three were from populations with a known high gene carriage rate, one Arab and two of West African origin. It remains possible that their genetic findings are entirely incidental to their symptoms. Next-generation sequencing may help to clarify the significance of such common relatively low-penetrance variants.

Although disease features seem to be similar in children and adults at presentation, there is a suggestion that some clinical manifestations, such as serositis, arthritis and constipation might be related to disease in adulthood (table 5).

Our study has a number of obvious limitations. Although multiple centres were involved most of these were specialist, and recruitment was unequally distributed, introducing a risk of geographical or centre-specific bias. The marked disparity in the number of patients from each country demonstrates this, since it seems very unlikely that TRAPS is several-fold more common in the UK and Italy. In addition this is a ‘Eurocentric’ cohort. TRAPS has been reported to occur in a wide spectrum of populations and given the large number of variants reported, the high rate of family-specific variants (58% occurred in only one individual or family in this cohort) and absence of any postulated specific selective advantage in Europe, it seems likely that TRAPS occurs throughout the world and that variations between populations reflect ascertainment bias due a combination of lack of awareness of a rare condition and difficulties in accessing or financing genetic testing. Using rather limited ethnic groups to define TRAPS disease has potential drawbacks. The most obvious of these arises if rash is made a central component of the diagnostic criteria, particularly as the rashes seen in TRAPS are often evanescent and macular, therefore much more prominent on paler-skinned individuals. We also have some concerns that there may be bias in the selection of patients entered into this study favouring patients with more severe disease and perhaps also patients with systemic symptoms as isolated rash or abdominal pain may be managed without considering the diagnosis. This may be most evident in patients with the lower-penetrant variants where only patients with particularly severe features have been referred to specialist centres and our data may therefore reflect only the most severe end of the spectrum of R92Q-associated disease. In addition, two-thirds of the study group were adults at recruitment and their recollection of their disease at presentation might have been imprecise, especially in older adults recollecting childhood illness many decades earlier.26

Finally, although we report disease features at presentation here, other aims of the registry are to follow-up patients over the long term. This should allow description of treatment responses and long-term outcomes (both medical and socioeconomic), and also the opportunity to identify prognostic factors and raise disease awareness.

Footnotes

Contributors: HJL and MG: design and coordination of the study, data collection and paper writing. RP and PW: analysis of the data and manuscript revision. NR, AM: coordination of the study and manuscript editing. KG, LO, IT, LC, JF, JA, IK-P, MC, BB-M, AI, VH, RM, CM, NT, RB, SO, RC, AJ, PAB and PNH: data collection and manuscript revision.

Funding: This project is supported by the Executive Agency for Health and Consumers of the European Union (EAHC, Project Nos 2007332 and 200923) and by Coordination Theme 1 (Health) of the European Community's FP7, grant agreement number HEALTH-F2-2008-200923. Unrestricted educational grants were also kindly provided by PRINTO and Novartis.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: G Gaslini Institute institutional review board.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Williamson LM, Hull D, Mehta Ret al. Familial Hibernian fever. Q J Med. 1982;51:469–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McDermott MF. Autosomal dominant recurrent fevers. Clinical and genetic aspects. Rev Rhum [Engl Ed] 1999;66:484–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aganna E, Hammond L, Hawkins PN, et al. Heterogeneity among patients with tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated periodic syndrome phenotypes. Arthritis Rheum 2003;48:2632–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McGonagle D, McDermott MF. A proposed classification of the immunological diseases. PLoS Medicine 2006;3:1242–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hull KM, Drewe E, Aksentijevich I, et al. The TNF receptor-associated periodic syndrome (TRAPS): emerging concepts of an autoinflammatory disorder. Medicine (Baltimore) 2002;81:349–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Milhavet F, Cuisset L, Hoffman HM, et al. The infevers autoinflammatory mutation online registry: update with new genes and functions. Hum Mutat 2008;29:803–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Touitou I, Lesage S, McDermott M, et al. Infevers: an evolving mutation database for auto-inflammatory syndromes. Hum Mutat 2004;24:194–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sarrauste de Menthiere C, Terriere S, Pugnere D, et al. INFEVERS: the Registry for FMF and hereditary inflammatory disorders mutations. Nucleic Acids Res 2003;31:282–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rebelo SL, Bainbridge SE, Amel-Kashipaz MR, et al. Modeling of tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily 1A mutants associated with tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated periodic syndrome indicates misfolding consistent with abnormal function. Arthritis Rheum 2006;54:2674–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Todd I, Radford PM, Daffa N, et al. Mutant tumor necrosis factor receptor associated with tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated periodic syndrome is altered antigenically and is retained within patients’ leukocytes. Arthritis Rheum 2007;56:2765–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nedjai B, Hitman GA, Yousaf N, et al. Abnormal tumor necrosis factor receptor I cell surface expression and NF-κB activation in tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated periodic syndrome. Arthritis Rheum 2008;58:273–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bachetti T, Chiesa S, Castagnola P, et al. Autophagy contributes to inflammation in patients with TNFR-associated periodic syndrome (TRAPS). Ann Rheum Dis 2012. Epub 2012/11/03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simon A, Park H, Maddipati R, et al. Concerted action of wild-type and mutant TNF receptors enhances inflammation in TNF receptor 1-associated periodic fever syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2010;107:9801–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ravet N, Rouaghe S, Dode C, et al. Clinical significance of P46L and R92Q substitutions in the tumour necrosis factor superfamily 1A gene. Ann Rheum Dis 2006;65:1158–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kumpfel T, Hohlfeld R. Multiple sclerosis. TNFRSF1A, TRAPS and multiple sclerosis. Nat Rev Neurol 2009;5:528–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lainka E, Neudorf U, Lohse P, et al. Incidence of TNFRSF1A mutations in German children: epidemiological, clinical and genetic characteristics. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2009;48:987–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kallinich T, Gattorno M, Grattan CE, et al. Unexplained recurrent fever: when is autoinflammation the explanation? Allergy 2013;68:285–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Toplak N, Frenkel J, Ozen S, et al. An international registry on autoinflammatory diseases: the Eurofever experience. Ann Rheum Dis 2012;71:1177–82 Epub 2012/03/02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ter Haar N, Lachmann H, Ozen S, et al. Treatment of autoinflammatory diseases: results from the Eurofever Registry and a literature review. Ann Rheum Dis 2012. Epub 2012/07/04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haas SL, Lohse P, Schmitt WH, et al. Severe TNF receptor-associated periodic syndrome due to 2 TNFRSF1A mutations including a new F60V substitution. Gastroenterology 2006;130:172–8 eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosen-Wolff A, Kreth HW, Hofmann S, et al. Periodic fever (TRAPS) caused by mutations in the TNFalpha receptor 1 (TNFRSF1A) gene of three German patients. Eur JHaematol 2001;67:105–9 eng. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stojanov S, Dejaco C, Lohse P, et al. Clinical and functional characterisation of a novel TNFRSF1A c.605T>A/V173D cleavage site mutation associated with tumour necrosis factor receptor-associated periodic fever syndrome (TRAPS), cardiovascular complications and excellent response to etanercept treatment. Ann Rheum Dis 2008;67:1292–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McDermott MF, Aksentijevich I, Galon J, et al. Germline mutations in the extracellular domains of the 55 kDa TNF receptor, TNFR1, define a family of dominantly inherited autoinflammatory syndromes. Cell 1999;97: 133–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Drewe E, McDermott EM, Powell PT, et al. Prospective study of anti-tumour necrosis factor receptor superfamily 1B fusion protein, and case study of anti-tumour necrosis factor receptor superfamily 1A fusion protein, in tumour necrosis factor receptor associated periodic syndrome (TRAPS): clinical and laboratory findings in a series of seven patients. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2003;42:235–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McDermott MF, Aganna E, Hitman GA, et al. An autosomal dominant periodic fever associated with AA amyloidosis in a north Indian family maps to distal chromosome 1q. Arthritis Rheum 2000;43:2034–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pelagatti MA, Meini A, Caorsi R, et al. Long-term clinical profile of children with the low-penetrance R92Q mutation of the TNFRSF1A gene. Arthritis Rheum 2011;63:1141–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aksentijevich I, Galon J, Soares M, et al. The tumor-necrosis-factor receptor-associated periodic syndrome: new mutations in TNFRSF1A, ancestral origins, genotype-phenotype studies, and evidence for further genetic heterogeneity of periodic fevers. Am J Hum Genet 2001;69:301–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]