Abstract

Dehydrins are thought to play an essential role in the plant response, acclimation and tolerance to different abiotic stresses, such as cold and drought. These proteins contain conserved and repeated segments in their amino acid sequence, used for their classification. Thus, dehydrins from angiosperms present different repetitions of the segments Y, S, and K, while gymnosperm dehydrins show A, E, S, and K segments. The only fragment present in all the dehydrins described to date is the K-segment. Different works suggest the K-segment is involved in key protective functions during dehydration stress, mainly stabilizing membranes. In this work, we describe for the first time two Pinus pinaster proteins with truncated K-segments and a third one completely lacking K-segments, but whose sequence homology leads us to consider them still as dehydrins. qRT-PCR expression analysis show a significant induction of these dehydrins during a severe and prolonged drought stress. By in silico analysis we confirmed the presence of these dehydrins in other Pinaceae species, breaking the convention regarding the compulsory presence of K-segments in these proteins. The way of action of these unusual dehydrins remains unrevealed.

Keywords: dehydrins, K-segments, drought, gene expression, qRT-PCR, Pinus

Introduction

Late embryogenesis abundant (LEA) 2 or dehydrin proteins are one of the main components of the response to several abiotic stresses (such as cold or drought) in the Plant kingdom. They constitute a highly complex multigenic family. Dehydrin proteins from angiosperm species are traditionally classified according to the number and order of three highly conserved segments in their amino acid sequence, named Y-, S-, and K-segments (Close, 1996, 1997). On their side, gymnosperm dehydrins are characterized by the absence of Y-segments and, at least in some families, the presence of A- and E-segments (Perdiguero et al., 2012a).

The only segment present in every dehydrin described to date is the K-segment. In angiosperms it consists in a highly conserved lysine rich 15-mer, with a consensus sequence EKKGIMDKIKEKLPG (Close, 1996), while in gymnosperms it shows a more variable sequence: (Q/E)K(P/A)G(M/L)LDKIK(A/Q)(K/M)(I/L)PG (Jarvis et al., 1996).

Although the biological role of the highly conserved K-segment is not yet established it is thought to play an essential role during abiotic stress responses (Close, 1996; Svensson et al., 2002). It may be involved in conformational changes through the formation of class A2 amphipathic α-helix. This helix is supposed to establish hydrophobic interactions with other proteins, stabilizing cell membranes (Campbell and Close, 1997; Danyluk et al., 1998; Koag et al., 2003). A study with dhn1 from maize concluded that the K-segment is necessary and sufficient for binding to anionic phospholipid vesicles (Koag et al., 2009). Also, the K-segments of dhn5 from wheat have been described as essential for the protection of two enzymes, lactate dehydrogenase and β-glycosidase (Drira et al., 2013). Similar results were reported for dhn5 from Rhododendron catawbiense and ERD10 from Arabidopsis, in which a deleterious effect on protective capacity of lactate dehydrogenase were observed when K-segments of these dehydrins were total or partially removed (Reyes et al., 2008). Antibacterial activity has also been reported for A. thaliana ERD10: a deletion study showed that K-segments are responsible of in vivo inhibition on E. coli cells (Campos et al., 2006). This effect was later validated using synthetic K-segments from a rice dehydrin which showed in vitro antibacterial activity, particularly against Gram-positive bacteria (Zhai et al., 2011).

Some peculiarities have been reported for three unusual dehydrins from citrus, COR11, COR15, and COR19, responsive to low temperature. These proteins differ from most other plant dehydrins by having a K-segment similar to that of gymnosperms and by having a serine cluster (S-segment) at an unusual position at the carboxy-terminus (Cai et al., 1995; Porat et al., 2002; Talon and Gmitter, 2008).

Here we report the identification and structural characterization of three novel dehydrin genes in Pinus pinaster which are characterized by the absence of a complete K-segment in the amino acid sequence. We have also confirmed by in silico analysis the presence of this unusual dehydrin in other conifer species. Additionally, we report that transcription of these genes is inducible by dehydration, as confirmed by quantitative RT-PCR analysis of their expression patterns in different organs during a severe and prolonged drought stress.

Materials and methods

Plant material and treatment conditions

The plant material and drought treatment described in Perdiguero et al. (2012a) was used for this study. P. pinaster clonal material of three different genotypes (F1P3, F2P2, F4P4) from Oria provenance (37° 30′ 30″ N 2° 20′ 20″ W, southeastern Spain) was grown in containers with peat:perlite:vermiculite (3:1:1). One year old cuttings were kept in growth chambers for 2 months with a photoperiod of 16/8 (day/night), with a temperature of 24°C and 60% of relative humidity during the day and 20°C and 80% of relative humidity during the night, and watered at field capacity prior to drought treatment.

Four ramets per genotype were collected at each sampling point. Unstressed plants were harvested 1 h after the last watering. The remaining plants were maintained without irrigation and collected every 10 days (five sampling points, S1–S5). Needles, stem and roots from each plant were collected separately, immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C.

Sequence analysis

Tentative contigs (TCs) assembled from ESTs corresponding to putative dehydrins of pines were searched in the Pine Gene Index 9.0 (http://compbio.dfci.harvard.edu/tgi/; release March 2011). TCs corresponding to unusual putative dehydrins from Pinus sp never reported in the literature were selected and used as query in SustainPineDB (version 3.0), a database containing the de novo assembled transcriptome from Pinus pinaster (Canales et al., 2013). Unigenes obtained this way were used to manually design primers (following Innis and Gelfand, 1990, recommendations) flanking the complete ORF for further PCR amplification from both gDNA and cDNA.

Identification of putative orthologous sequences was performed using BLASTP and TBLASTN software in GenBank databases as well as in High Confidence Genes database version 1.0 of Norway spruce genome project, available in ConGenIE website. BioEdit was used to transcribe nucleotide sequences to amino acid sequences and MUSCLE software (Edgar, 2004) was used to align deduced amino acid sequences. Maximum likelihood methods were applied to estimate phylogeny of Pinus pinaster dehydrins using the software PhyML 3.0 (Guindon et al., 2010). Both alignment and phylogeny analysis were performed in the website Phylogeny.fr (Dereeper et al., 2008). DISOPRED3 (Ward et al., 2004) and Phyre2 (Kelley and Sternberg, 2009) softwares were used to identify the putative secondary structure and disordered regions.

DNA and RNA isolation and gene searching

Genomic DNA was extracted from needles and megagametophytes following Doyle (1990), with slight modifications. Total RNA was isolated separately from roots, stem and needles following a CTAB–LiCl precipitation method (Chang et al., 1993). cDNA was synthesized from 1μg of total RNA using PowerScriptIII reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). Complete sequences for each studied dehydrin were amplified by PCR, using cDNA and genomic DNA as templates and specific primers (Table 1). The PCR products were cloned into pGEM®T-easy vector (Promega, WI, USA) and transformed into Escherichia coli DH5α cells. The obtained clones were sequenced and aligned using Spidey mRNA-to-genomic software (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/spidey/) to reveal the exon-intron structure of the genes.

Table 1.

Specific primers used in isolation of complete ORF and RT-PCR.

| Dehydrin | Forward | Sequence (5 ′-3 ′) | Reverse | Sequence (5 ′-3 ′) | Length genomic | Length cDNA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Specific primers used in isolation of complete ORF | ||||||

| Ppter_dhn_SK′a | SK′a_FW | ATATTTGAATTTGCAGGTTGATAACT | SK′a_RV | CGCTCCTCCTTCCGTTTCTA | 708 bp | 545 bp |

| Ppter_dhn_SK′b | SK′b_FW | GGTTGATAGCTTTTCAAATTACC | SK′b_RV | CTTCCGTTACCATGGACTTC | 665 bp | 522 bp |

| Ppter_dhn_S | S_FW | GAATTTGCAGGTTGATAGCTT | S_RV | GGATCTTCCTGCTGTTACTTA | 687 bp | 544 bp |

| Specific primers used in RT-PCR | Length amplicon | |||||

| Ppter_dhn_SK′a | SK′a_RT_FW | AAGGAGAAAATGCACGTTGG | SK′a_RT_RV | GCTGGATGATGATAAGGTGC | 89 bp | |

| Ppter_dhn_SK′b | SK′b_RT _FW | GGCAGGAAAAAGGAAGAAAGGA | SK′b_RT _RV | TGCAGCAGCAGCAGCTAGATA | 120 bp | |

| Ppter_dhn_S | S_RT _FW | CGGCAAGAATAAGGACGGAAAT | S_RT _RV | GCGGAGCAGCCACAGCTA | 122 bp | |

| Ri18S | Ri18S_RT_FW | GCGAAAGCATTTGCCAAGG | Ri18S_RT_RV | ATTCCTGGTCGGCATCGTTTA | 110 bp | |

Real-time quantitative PCR

Total RNA from roots, stem and needles of each plant was treated with DNAse Turbo (Ambion; Applied Biosystems, Life Technologies, CA, USA). First-strand cDNA was synthesized from 2μg of total RNA from each sample using PowerScriptIII reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen, Life Technologies, Paisley, UK) according to the supplier's manual. 18S rRNA was used as a control, after verifying that the signal intensity remained unchanged across all treatments. Primer Express v. 3.0.0 (Applied Biosystems Life Technologies, CA, USA) software was used to design PCR primers. Amplified fragments were sequenced to check reaction specificity, and primers were modified when needed in order to avoid cross amplification. Final primers are shown in Table 1. Polymerase chain reactions were performed in an optical 96-well plate with a CFX 96 Detection system (BIO-RAD), using EvaGreen to monitor dsDNA synthesis. Reactions containing 2x SsoFast EvaGreen Supermix reagent (BIO-RAD, CA, USA), 12.5 ng cDNA and 500 nM of primers in a final volume of 10μl were subjected to the specific thermal profile. Three technical replicates were performed for each PCR run. The expression ratios were then obtained using the ΔΔCT method corrected for the PCR efficiency for each gene (Pfaffl, 2001).

Sequences deposition

The sequences obtained in this study were submitted to the GenBank with the following accessions numbers; KM033833–KM033835 for mRNA and KM033843–KM033845 for genomic DNA.

Results

In silico identification of K-segment lacking dehydrins

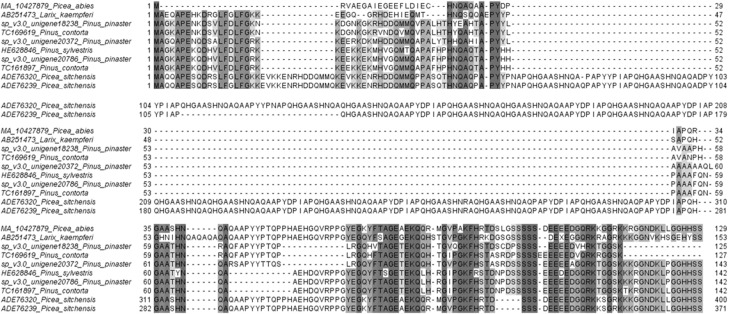

Exhaustive search of dehydrin sequences in the Pine Gene Index allowed the identification of 47 full amino acid sequences in a previous work (Perdiguero et al., 2012a). Analysis of the sequences considered incomplete then, led to the identification of two TCs from Pinus contorta (TC169619 and TC161897), which do not present a complete K-segment. Blast searching in SustainPineDB using these sequences as query resulted in three unigenes from P. pinaster that encoded putative full dehydrins (sp_v3.0_unigene20786, sp_v3.0_unigene18238 and sp_v3.0_unigene20372). Other homologous were found in different conifer species (such as Pinus sylvestris, Picea abies, Picea sitchensis or Larix kaempferi) by searching in Genbank databases. Figure 1 shows an alignment of these amino acid sequences.

Figure 1.

Optimized alignment performed with MUSCLE software of dehydrins from conifer species identified in different databases. All dehydrins share the absence of complete K-segments in their amino acid sequences.

Isolation and analysis of K-segment lacking dehydrins from pinus pinaster

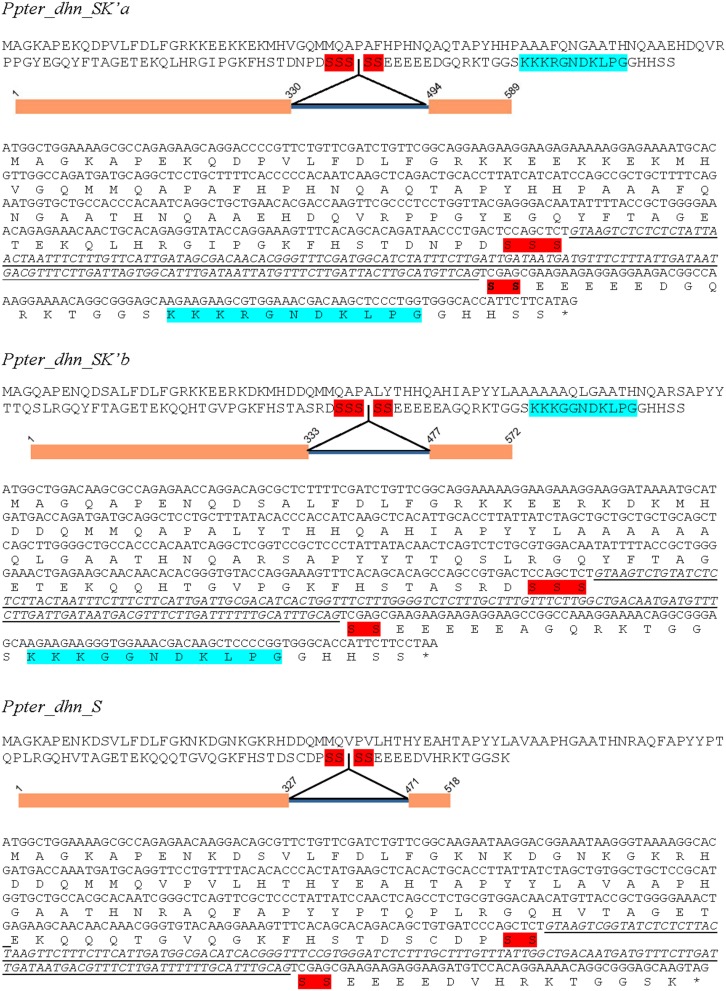

Pinus pinaster sequences were used to design specific PCR primers (Table 1). PCR amplification from genomic DNA and cDNA from water stressed P. pinaster plants have led to the isolation of three full ORF (Supplementary Figure S1). Sequencing of haploid genomic DNA from megagametophytes confirmed their presence at three different loci within the P. pinaster genome. They were named as Ppter_dhn_SK'a (sp_v3.0_unigene20786) Ppter_dhn_SK'b (sp_v3.0_unigene20372) and Ppter_dhn_S (sp_v3.0_unigene18238), according to the conserved segments present in their amino acid sequences (Figure 2). All of them show a very short S-segment and two of them also have a modified and truncated K-segment (K').

Figure 2.

Nucleotide and amino acid sequences of Ppter_dhn_SK'a, Ppter_dhn_SK'b, and Ppter_dhn_S. A schematic figure shows the exon-intron structure. Conserved amino acid segments are highlighted. Red, S-segments; Blue, partial K-segments.

Ppter_dhn_SK'a has a 426 nucleotide-long ORF encoding a protein with 142 amino acids, and pI 7.20. This sequence accumulates several modifications in the region corresponding to the A-segment, showing the sequence QAQTAPYH (in bold the conserved residues, compared with the consensus sequence EAASYYP). It has a very short S-segment composed by 5 serine residues. Comparison of the genomic and cDNA sequences allowed the identification of a 163 nucleotide-long intron within the S-segment. It also presents a modified K-segment with 11 amino acids (KKKRGND—-KLPG; in bold the conserved residues). On its side, the deduced amino acid sequence of Ppter_dhn_SK'b is formed by 143 amino acids, with pI 8.00. It presents two putative modified A-segments (QAHIAPYYL and QARSAPYYT). This sequence also presents a 5 serine-long S-segment with an intron of 143 nucleotides in it and a similar modified K-segment (KKKGGND—-KLPG). Finally, Ppter_dhn_S has an ORF with 375 nucleotides, encoding a 125 amino acids long protein, with pI 6.76. The two putative A-segments present several modifications, as in the other two sequences (EAHTAPYYL and RAQFAPYYP). It shows a very short S-segment, with only 4 serine residues, and a 143 nucleotide-long intron in it. No K-segment can be detected in this sequence.

High percentages of disordered regions, ranging from 64 to 77%, were predicted for the three sequences; several fragments were identified as potential region for α-helix whereas few places were identified to produce β-strand (Supplementary Figure S2).

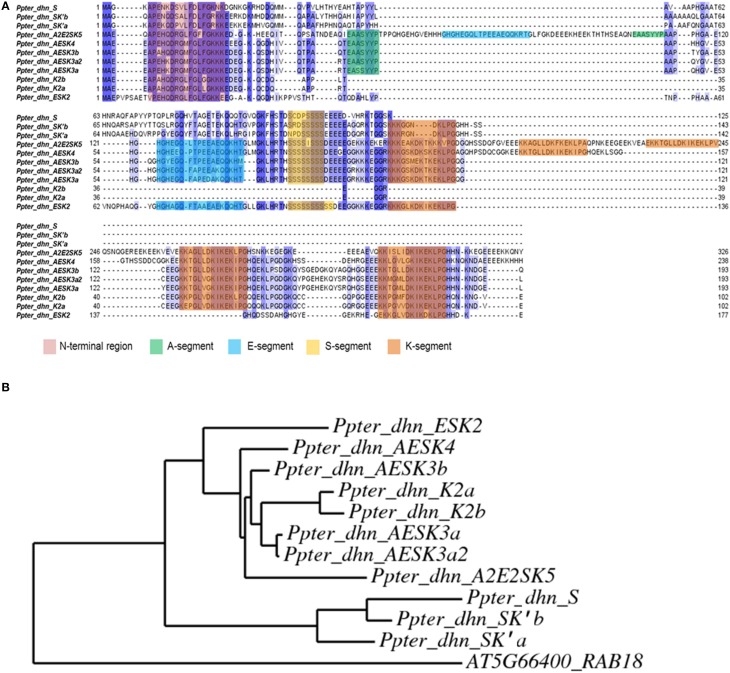

The alignment of the amino acid sequences of these three novel dehydrins with the eight dehydrins described previously in P. pinaster and their phylogenetic relationships are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

(A) Alignment (performed with MUSCLE software) of amino acid sequences corresponding to Pinus pinaster dehydrins from Perdiguero et al. (2012a) and dehydrins isolated in the present work. Conserved segments (N-terminal, A, E, S, and K) are highlighted. (B) Phylogenetic tree (performed with PhyML software) of Pinus pinaster dehydrins. AT5G66400_RAB18 from Arabidopsis thaliana has been used as outgroup.

Expression of dhn-S from pinus pinaster

Quantitative RT-PCR analysis of the expression patterns of Ppter_dhn_SK'a, Ppter_dhn_SK'b, and Ppter_dhn_S during a severe and prolonged drought stress were carried out independently in roots, stems and needles of three genotypes from Oria. This provenance, in southeastern Spain, has previously been shown to have a good inducible response to water stress (Sánchez-Gómez et al., 2010) and has been used for the selection of candidate genes involved in the response to water deficit (Perdiguero et al., 2012b).

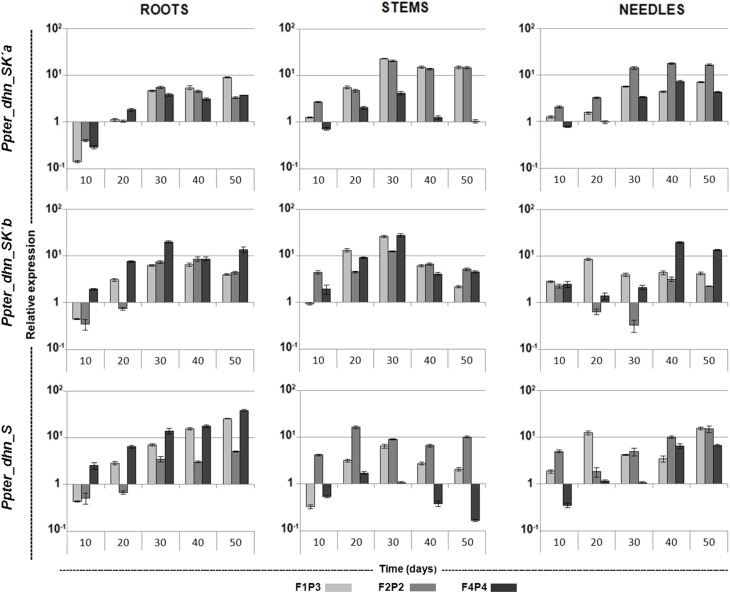

Noticeable increases in transcription level have been detected for the three dehydrins during the drought stress (Figure 4). Thus, transcription levels of Ppter_dhn_SK'a increased during the first steps of the experiment. Maximum inductions were detected after 30 days without watering, when transcription levels in roots, leaves and stems of stressed plants reached average values 5-, 8-, and 16-fold higher, respectively, than in unstressed plants. After that, transcription levels were roughly maintained in roots and needles, and decreased slowly in stems. On its side, transcription of Ppter_dhn_SK'b in roots also increased with drought stress, reaching its maximum value at 30–40 days (approximately 8-fold higher compared with unstressed plants, and even 20-fold higher for one of the genotypes). Transcription induction was faster and stronger in stems, reaching maximum values at 30 days (more than 20-fold higher levels) and decreasing afterwards. On the contrary, the pattern was less consistent in needles, with noticeable variability among genotypes. Finally, Ppter_dhn_S showed a continuously increasing transcription in roots throughout the experiment, reaching values more than 25-fold higher in two of the genotypes after 50 days without watering. Maximum values were also attained at the end of the experiment in needles, while the pattern was less consistent in stems, with maximum inductions at 20–30 days. Afterwards, transcription decreased, reaching values even 6-fold lower than in control plants at the fifth sampling point for one of the genotypes, while the others still showed values 2- and 10-fold higher than in control plants.

Figure 4.

qRT-PCR expression profiles of Ppter_dhn_SK'a, Ppter_dhn_SK'b, and Ppter_dhn_S in roots, stems and needles of three different genotypes along a drought stress treatment, relative to unstressed (control) plants. Three technical replicates per genotype (F1P3, F2P2, and F4P4) were used at each point. Standard errors are shown.

Discussion

In this work we identified and characterized three novel proteins from Pinus pinaster whose overall homology leads us to consider them as dehydrins. However, they present several noticeable differences with usual dehydrins. For instance, they show several modifications in the N-terminal region (Figure 3), rather well conserved among Pinaceae dehydrins (Perdiguero et al., 2012a). They also accumulate discrepancies in the A-segment and present extremely short S-segments, with 4–5 serine residues, while other P. pinaster dehydrins have 7–9 residues. The three genes include an intron within the S-segment, a feature also found in other P. pinaster dehydrins (Perdiguero et al., 2012a), as well as in SKn-type dehydrins from angiosperms (Jiménez-Bremont et al., 2013).

However, the most remarkable difference appears in the short C-terminal region (starting from the S-segment), with the absence of a proper K-segment. Close (1996) provided a detailed description of dehydrins, analyzing the complete sequences available at the moment (67 from angiosperm and 3 from gymnosperm). He concluded that the dehydrin family is unified by the presence of one or more copies of the K-segment. This characteristic has been confirmed in all dehydrins described in plants up to date, including several studies analyzing complete genomes. For instance, the dehydrin protein family has been analyzed in the moss Phycomitrella patens (Ruibal et al., 2012), in herbaceous species as Arabidopsis thaliana (Bies-Ethève et al., 2008; Hundertmark and Hincha, 2008) or Oryza sativa (Wang et al., 2007), in different legumes (Battaglia and Covarrubias, 2013) and tree species as Prunus mume (Du et al., 2013) or Populus trichocarpa (Liu et al., 2012; Lan et al., 2013). All the dehydrins identified in these works present K-segments in their amino acid sequences, although with different modifications in certain cases. The information available is so robust that the presence of at least one K-segment have been assumed as necessary in recent reviews (Kosová et al., 2010; Eriksson and Harryson, 2011; Hanin et al., 2011), while other homologous genomic sequences lacking K-segment have been annotated as uncharacterized or hypothetical proteins and not as dehydrins (f.i., XP_008240561 from Prunus mume, XP_007201808.1 from Prunus persica or XP_004234737.1 from Solanum lycopersicon).

Strikingly, two of the proteins described here present shortened and modified K-segments, which we have called K'-segments, while the third one absolutely lacks this region. However, these three proteins show high overall homology levels with typical dehydrins, especially in certain regions (N-terminal region, S-segment and modified K-segment; Figure 3), which leads us to consider them still as dehydrins. They also share structural characteristics with usual dehydrins. For instance, regarding their predicted secondary structure, several putative α-helix are identified, but a high proportion (70%) of their sequences, especially in the less conserved regions, is classified as disordered. These percentages are comparable to the ones predicted for other dehydrins, not only in P. pinaster but also in angiosperm species as Populus trichocarpa or Arabidopsis thaliana (Supplementary Figure S2). It is believed that this feature, the high percentage of disordered secondary structure, is relevant to the fulfillment of the protective role of dehydrins during water stress (Mouillon et al., 2008; Hughes and Graether, 2011).

Additionally, the three genes described here have shown a noticeable increase in transcription levels under drought stress. This induction is similar or even higher than those reported for other “orthodox,” K and AESK dehydrins in P. pinaster (Perdiguero et al., 2012a). In general, transcription increases throughout the experiment, reaching a maximum at 30–50 days without watering. Expression patterns are more consistent in roots, which could be related to the key role played by this organ in detecting and triggering the response to water stress. On the contrary, more variability is detected in the expression patterns in stems and leaves. In all the cases, the overall transcription levels are low and, certainly, induction is not comparable to that of the drought-responsive Ppter_dhn_ESK2 (Perdiguero et al., 2012a). However, as reported for other dehydrins, we cannot discard that these K-segment lacking dehydrins are effective in protection against drought stress even at low concentrations, and/or that they could be involved in other processes different from drought stress.

Consistently, in silico analysis of available RNA-seq data from different libraries of Picea abies (Nystedt et al., 2013) shows also differential expression of MA_10427879g0010, the putative orthologous gene of the ones reported here. For instance, noticeable transcription induction is detected in needles at midday, as well as in stems and needles of girdled twigs, in which hydraulic conductivity is affected and dehydration processes are registered (Supplementary Figure S3).

Pines have abundant repetitions and pseudogenes in their huge genomes (Morse et al., 2009). At a first glance these loci might seem an example of this sort of repetitions, which eventually could, in the course of evolution, further diverge or even become pseudogenes. Two of the sequences reported here present a degenerated K-segment and the third one completely lacks this segment, which is considered to be relevant for dehydrin functionality. Additionally, high variability in their transcription under water stress has been observed among genotypes and organs, which could be seen as an indirect evidence of the no functionality of these three proteins. Nevertheless, maybe the 8 conserved residues in the K-segments of two of them (KKKXGX-D—-KLPG) could be determinant for α-helix formation and protective activity. Further in vivo and in vitro experiments are needed to clarify the effect of these modifications and to confirm if these proteins are actually functional or not.

Author contributions

Pedro Perdiguero performed the laboratory work. Pedro Perdiguero and Álvaro Soto drafted the manuscript. Carmen Collada and Álvaro Soto conceived and designed the experiments. All authors contributed to writing the article and approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the three anonymous reviewers and the editor for their helpful comments and suggestions. This work has been funded through the projects AGL2006-03242/FOR (Spanish Ministry of Education and Science), CCG07-UPM/AMB-1932 and CCG10-UPM/AMB-5038 (Madrid Regional Government-UPM).

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://www.frontiersin.org/journal/10.3389/fpls.2014.00682/abstract

References

- Battaglia M., Covarrubias A. A. (2013). Late Embryogenesis Abundant (LEA) proteins in legumes. Front. Plant Sci. 4:190. 10.3389/fpls.2013.00190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bies-Ethève N., Gaubier-Comella P., Debures A., Lasserre E., Jobet E., Raynal M., et al. (2008). Inventory, evolution and expression profiling diversity of the LEA (late embryogenesis abundant) protein gene family in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Mol. Biol. 67, 107–124. 10.1007/s11103-008-9304-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Q., Moore G. A., Guy C. L. (1995). An unusual group 2 LEA gene family in citrus responsive to low temperature. Plant Mol. Biol. 29, 11–23. 10.1007/BF00019115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell S. A., Close T. J. (1997). Dehydrins: genes, proteins, and associations with phenotypic traits. New Phytol. 137, 61–74 10.1046/j.1469-8137.1997.00831.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Campos F., Zamudio F., Covarrubias A. A. (2006). Two different late embryogenesis abundant proteins from Arabidopsis thaliana contain specific domains that inhibit Escherichia coli growth. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 342, 406–413. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.01.151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canales J., Bautista R., Label P., Gómez-Maldonado J., Lesur I., Fernández-Pozo N., et al. (2013). De novo assembly of maritime pine transcriptome: implications for forest breeding and biotechnology. Plant Biotechnol. J. 12, 286–299. 10.1111/pbi.12136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang S., Puryear J., Cairney J. (1993). A simple and efficient method for isolating RNA from pine trees. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 11, 113–116. 10.1007/BF0267046811725489 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Close T. J. (1996). Dehydrins: emergence of a biochemical role of a family of plant dehydration proteins. Physiol. Plant. 97, 795–803 10.1111/j.1399-3054.1996.tb00546.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Close T. J. (1997). Dehydrins: a commonality in the response of plants to dehydration and low temperature. Physiol. Plant. 100, 291–296 10.1111/j.1399-3054.1997.tb04785.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Danyluk J., Perron A., Houde M., Limin A., Fowler B., Benhamou N., et al. (1998). Accumulation of an acidic dehydrin in the vicinity of the plasma membrane during cold acclimation of wheat. Plant Cell Online 10, 623–638. 10.1105/tpc.10.4.623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dereeper A., Guignon V., Blanc G., Audic S., Buffet S., Chevenet F., et al. (2008). Phylogeny.fr: robust phylogenetic analysis for the non-specialist. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, W465–W469. 10.1093/nar/gkn180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle J. J. (1990). Isolation of plant DNA from fresh tissue. Focus 12, 13–15. [Google Scholar]

- Drira M., Saibi W., Brini F., Gargouri A., Masmoudi K., Hanin M. (2013). The K-segments of the wheat dehydrin DHN-5 are essential for the protection of lactate dehydrogenase and β-glucosidase activities In Vitro. Mol. Biotechnol. 54, 643–650. 10.1007/s12033-012-9606-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du D., Zhang Q., Cheng T., Pan H., Yang W., Sun L. (2013). Genome-wide identification and analysis of late embryogenesis abundant (LEA) genes in Prunus mume. Mol. Biol. Rep. 40, 1937–1946. 10.1007/s11033-012-2250-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar R. C. (2004). MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, 1792–1797. 10.1093/nar/gkh340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson S. K., Harryson P. (2011). Dehydrins: molecular biology, structure and function, in Plant Desiccation Tolerance, eds Luttge U., Beck E., Bartels D. (New York, NY: Springer; ), 289–305. [Google Scholar]

- Guindon S., Dufayard J. F., Lefort V., Anisimova M., Hordijk W., Gascuel O. (2010). New algorithms and methods to estimate maximum-likelihood phylogeny: assessing the performance of PhyML3.0. Syst. Biol. 59, 307–321. 10.1093/sysbio/syq010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanin M., Brini F., Ebel C., Toda Y., Takeda S., Masmoudi K. (2011). Plant dehydrins and stress tolerance: versatile proteins for complex mechanisms. Plant Signal. Behav. 6, 1503–1509. 10.4161/psb.6.10.17088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes S., Graether S. P. (2011). Cryoprotective mechanism of a small intrinsically disordered dehydrin protein. Protein Sci. 20, 42–50. 10.1002/pro.534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hundertmark M., Hincha D. K. (2008). LEA (late embryogenesis abundant) proteins and their encoding genes in Arabidopsis thaliana. BMC Genomics 9:118. 10.1186/1471-2164-9-118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Innis M. A., Gelfand D. H. (1990). Optimization of PCRs, in PCR Protocols: A Guide to Methods and Applications, eds Innis M. A., Gelfand D. H., Sninsky J. J., White T. J. (San Diego, CA: Academic Press; ), 3–12. [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis S. B., Taylor M. A., Macleod M. R., Davies H. V. (1996). Cloning and characterisation of the cDNA clones of three genes that are differentially expressed during dormancy-breakage in the seeds of Douglas Fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii). J. Plant Physiol. 147, 559–566 10.1016/S0176-1617(96)80046-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez-Bremont J. F., Maruri-López I., Ochoa-Alfaro A. E., Delgado-Sánchez P., Bravo J., Rodríguez-Kessler M. (2013). LEA gene introns: is the intron of dehydrin genes a characteristic of the serine-segment? Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 31, 128–140 10.1007/s11105-012-0483-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley L. A., Sternberg M. J. (2009). Protein structure prediction on the Web: a case study using the Phyre server. Nat. Protoc. 4, 363–371. 10.1038/nprot.2009.2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koag M. C., Fenton R. D., Wilkens S., Close T. J. (2003). The binding of Maize DHN1 to lipid vesicles. Gain of structure and lipid specificity. Plant Physiol. 131, 309–316. 10.1104/pp.011171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koag M.-C., Wilkens S., Fenton R. D., Resnik J., Vo E., Close T. J. (2009). The K-segment of maize DHN1 mediates binding to anionic phospholipid vesicles and concomitant structural changes. Plant Physiol. 150, 1503–1514. 10.1104/pp.109.136697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosová K., Prásil I. T., Vítámvás P. (2010). Role of dehydrins in plant stress response, in Handbook of Plant and Crop Stress, 3rd Edn., ed Pessarakli M. (Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; ), 239–285. [Google Scholar]

- Lan T., Gao J., Zeng Q.-Y. (2013). Genome-wide analysis of the LEA (late embryogenesis abundant) protein gene family in Populus trichocarpa. Tree Genet. Genomes 9, 253–264 10.1007/s11295-012-0551-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C.-C., Li C.-M., Liu B.-G., Ge S.-J., Dong X.-M., Li W., et al. (2012). Genome-wide identification and characterization of a dehydrin gene family in poplar (Populus trichocarpa). Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 30, 848–859 10.1007/s11105-011-0395-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morse A. M., Peterson D. G., Islam-Faridi M. N., Smith K. E., Magbanua Z., Garcia S. A., et al. (2009). Evolution of genome size and complexity in Pinus. PLoS ONE 4:e4332. 10.1371/journal.pone.0004332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouillon J.-M., Eriksson S. K., Harryson P. (2008). Mimicking the plant cell interior under water stress by macromolecular crowding: disordered dehydrin proteins are highly resistant to structural collapse. Plant Physiol. 148, 1925–1937. 10.1104/pp.108.124099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nystedt B., Street N. R., Wetterbom A., Zuccolo A., Lin Y.-C., Scofield D. G., et al. (2013). The Norway spruce genome sequence and conifer genome evolution. Nature 497, 579–584. 10.1038/nature12211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perdiguero P., Barbero M. C., Cervera M. T., Soto Á., Collada C. (2012a). Novel conserved segments are associated with differential expression patterns for Pinaceae dehydrins. Planta 236, 1863–1874. 10.1007/s00425-012-1737-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perdiguero P., Collada C., Barbero M. C., García Casado G., Cervera M. T., Soto Á. (2012b). Identification of water stress genes in Pinus pinaster Ait. by controlled progressive stress and suppression-subtractive hybridization. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 50, 44–53. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2011.09.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaffl M. W. (2001). A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 29:e45. 10.1093/nar/29.9.e45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porat R., Pavoncello D., Lurie S., McCollum T. G. (2002). Identification of a grapefruit cDNA belonging to a unique class of citrus dehydrins and characterization of its expression patterns under temperature stress conditions. Physiol. Plant. 115, 598–603. 10.1034/j.1399-3054.2002.1150414.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes J. L., Campos F., Wei H. U. I., Arora R., Yang Y., Karlson D. T., et al. (2008). Functional dissection of Hydrophilins during in vitro freeze protection. Plant Cell Environ. 31, 1781–1790. 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2008.01879.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruibal C., Salamó I. P., Carballo V., Castro A., Bentancor M., Borsani O., et al. (2012). Differential contribution of individual dehydrin genes from Physcomitrella patens to salt and osmotic stress tolerance. Plant Sci. 190, 89–102. 10.1016/j.plantsci.2012.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Gómez D., Majada J., Alía R., Feito I., Aranda I. (2010). Intraspecific variation in growth and allocation patterns in seedlings of Pinus pinaster Ait. submitted to contrasting watering regimes: can water availability explain regional variation? Ann. For. Sci. 67, 8 10.1051/forest/2010007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Svensson J., Ismail A. M., Tapio Palva E., Close T. J. (2002). Dehydrins. Cell Mol. Response Stress 3, 155–171. 10.1016/S1568-1254(02)80013-419842064 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Talon M., Gmitter F. G., Jr.. (2008). Citrus genomics. Int. J. Plant Genomics 2008:528361. 10.1155/2008/528361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X.-S., Zhu H.-B., Jin G.-L., Liu H.-L., Wu W.-R., Zhu J. (2007). Genome-scale identification and analysis of LEA genes in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Plant Sci. 172, 414–420 10.1016/j.plantsci.2006.10.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ward J. J., McGuffin L. J., Bryson K., Buxton B. F., Jones D. T. (2004). The DISOPRED server for the prediction of protein disorder. Bioinformatics 20, 2138–2139. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhai C., Lan J., Wang H., Li L., Cheng X., Liu G. (2011). Rice dehydrin K-segments have in vitro antibacterial activity. Biochemistry (Moscow) 76, 645–650. 10.1134/S0006297911060046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.