Abstract

Background

People with disability, multiple chronic conditions or both may experience challenges in accessing primary care. We aimed to determine the association between appropriate cervical cancer screening and level of disability among women eligible for screening in Ontario and the influence of relevant sociodemographic and health-related variables, including level of morbidity (measured by number of chronic conditions), on screening.

Methods

We used multiple linked databases, including 2 waves of the Canadian Community Health Survey (2005 and 2007/08). Of the 22 824 women included in the study, 7600 reported some level of disability. We used Ontario Health Insurance Plan fee codes to identify appropriate cervical cancer screening.

Results

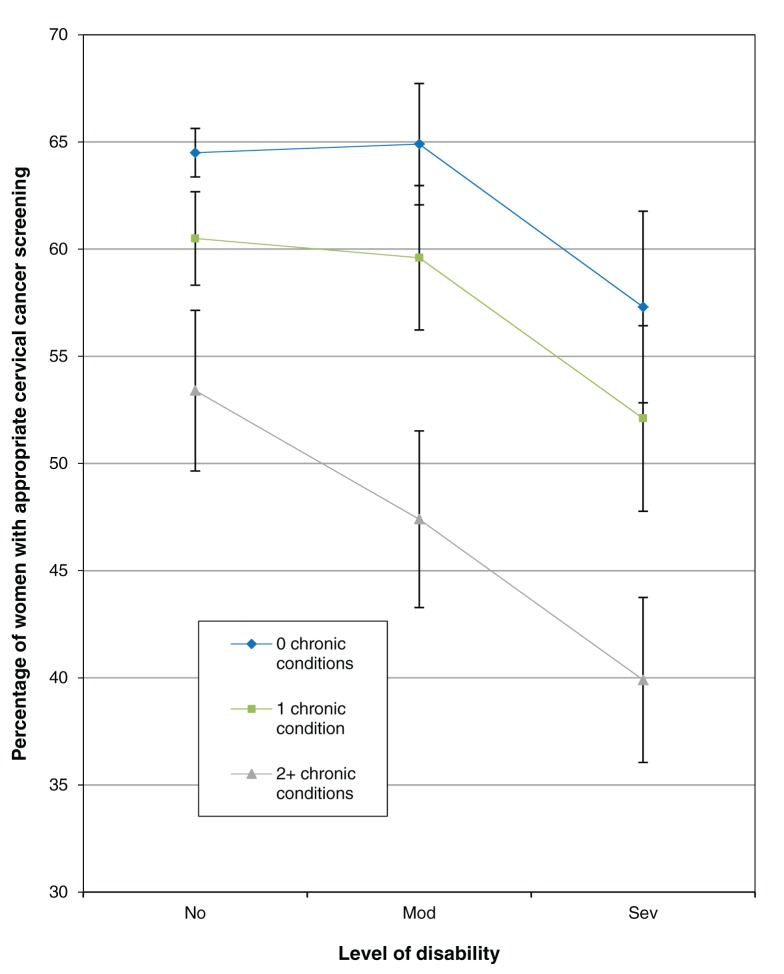

Compared with women without disability, women with disability were older, less educated, had lower income and had more chronic conditions (36.2% had at least 2 conditions v. 8.4% of women without disability). Women with no disability and no chronic conditions were more frequently screened appropriately than those with severe disability and 2 or more chronic conditions (64.5% v. 39.8%). In multivariable logistic regression analysis, age, rurality, education, marital status and household income were each independently associated with cervical cancer screening. There was a significant interaction between level of morbidity and level of disability. Women with a higher level of disability were less likely to be screened than women with lower level of disability as their level of morbidity increased.

Conclusion

The rate of screening for cervical cancer is low among women with both disability and multimorbidity. Policymakers should note these results as they work toward improving cancer screening rates for an aging population with complex medical needs.

It is estimated that up to 90% of invasive cervical cancers can be prevented by regular screening.1 Cervical cancer screening has been highly effective in Canada, where annual incidence and mortality rates have steeply declined in recent decades to among the lowest in the world.1–3 This decline has been attributed to widespread use of the Papanicolaou (Pap) test.3 In Ontario, current guidelines recommend that women 21 years and over who have ever been sexually active be screened every 3 years until the age of 70.4

Cervical cancer screening, with its proven effectiveness, strong advocacy in clinical guidelines4 and broad applicability, is an important example of a preventive intervention that should be equally accessible to all eligible women, regardless of concurrent illness or disability. However, the literature suggests that people with disabilities or multiple chronic conditions may experience challenges in accessing high-quality preventive health care. Those with multimorbidity and complex health care needs often receive incomplete care and may be less likely to receive preventive health services, despite using health services more frequently.5–11 Although disability and multimorbidity have been studied individually, there is a gap in the literature with regard to understanding how disability and multimorbidity interact to influence screening.

Therefore, we linked provincial survey and administrative data in a retrospective cohort study to determine the association between appropriate cervical cancer screening and levels of disability and multimorbidity among women eligible for screening in Ontario. We also examined the influence of additional sociodemographic and health-related variables on appropriate screening for these women.

Methods

Data sources

The data sources used in this study were accessed at the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences and included the 2005 and 2007/08 Canadian Community Health Surveys. The Canadian Community Health Survey is a cross-sectional self-report survey administered by Statistics Canada. It gathers information on health status, health care utilization and health determinants for the Canadian population.

The Ontario Health Insurance Plan’s Claims Database contains physicians’ fee-for-service claims and its Registered Persons Database documents the age, sex, date of birth, date of death and postal code of each health card holder in the province. The Ontario Cancer Registry includes all Ontario residents who have been newly diagnosed with cancer or who have died of cancer. The Canadian Institute for Health Information Discharge Abstract Database contains information on all hospital discharges and corresponding diagnostic and procedure codes. Ontario residents were linked through all administrative databases and to the Canadian Community Health Survey by a unique anonymized identifying number.

Study population

The study population was drawn from respondents to the 2005 and 2007/08 Canadian Community Health Surveys who agreed to have their responses linked with their personal health information (approximately 30 000 people per survey cycle). We included female residents of Ontario who were 21–69 years of age and alive during an entire 3-year observation window (i.e., the 3 calendar years after completion of the survey: Jan. 1, 2006 to Dec. 31, 2008 or Jan. 1, 2009 to Dec. 31, 2011), were eligible for health care during the entire observation window and answered the survey’s Participation and Activity Limitation questions. Any woman with a diagnosis of an invasive cervical cancer before the end of the observation window or with a prior hysterectomy was excluded, as she would not be eligible for screening for the entire 3-year period.

Definitions and measures

Following Statistics Canada, we defined disability as a limitation on performing daily activities because of a condition or health problem.12,13 We measured the level of disability using the Participation and Activity Limitation items in the Canadian Community Health Survey.12–14 These items classify respondents by the frequency with which they experience activity limitations because of a condition (or conditions) or a long-term health problem that has lasted or is expected to last 6 months or more. We classified women who reported never, sometimes and often experiencing activity limitations as having no, moderate and severe disability, respectively.

We followed a definition of multimorbidity used in the literature as the co-existence of at least 2 chronic conditions in 1 patient.15 We measured morbidity based on self-reported diagnoses of chronic conditions included in the Canadian Community Health Survey, namely arthritis, hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder, diabetes, heart disease, cancer, stroke, dementia and mood/anxiety disorder. In 2009, more than 40% of Canadian adults reported having at least 1 of these conditions.16 We classified level of morbidity as 0, 1 or at least 2 of these chronic conditions.

Sociodemographic measures documented for each cohort member from the Canadian Community Health Survey included age, immigrant status, education level, household income and marital status. We obtained Rurality Index of Ontario scores and neighbourhood income quintile from administrative databases based on women’s postal codes.17 Other health-related measures drawn from administrative databases included health care use during the study period, namely the overall number of physician visits, family physician visits, specialist visits, emergency department visits and admissions to hospital.

We used Ontario Health Insurance Plan fee codes for Pap tests to identify appropriate cervical cancer screening. We examined screening rates over a 3-year period according to provincial guidelines,4 specifically the 3 calendar years following each cohort member’s completion of the survey.

Data analysis

We used descriptive statistics to characterize the study cohort. We also conducted parametric and non-parametric bivariable analyses. All statistical tests were performed at the 5% level of significance, were 2-sided and were carried out using SAS version 9.1.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). We employed multivariable logistic regression to examine differences in cervical screening rates. Predictor variables included household income, age as a continuous variable, education, rurality, marital status, level of morbidity and level of disability. We also tested for an interaction effect between level of morbidity and level of disability. We excluded cases with missing data from the bivariable and multivariable analyses.

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Board of Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre.

Results

Data were initially stratified by year of completion of the Canadian Community Health Survey; however, because differences were negligible, the survey cohorts were subsequently combined. Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of the study cohort. A total of 22 824 women were included, 7600 of whom had some level of disability (moderate or severe). Women with disability tended to be older, less educated and have a lower income than women without disability. They were more likely to be separated or divorced and more than 4 times as likely to have at least 2 chronic conditions: 36.2% had at least 2 chronic conditions versus 8.4% of women without disability. Differences in sociodemographic characteristics tended to be more pronounced as level of disability increased from moderate to severe. During the study period, women with disability had significantly more family physician visits (mean 15.1 v. 10.7, p < 0.001), specialist visits (mean 8.1 v. 4.8, p < 0.001) and emergency department visits (mean 2.5 v. 1.6, p < 0.001) than women without disability.

Table 1: Participant characteristics (n = 22 824).

| Characteristic | No. (%) or mean ± SD |

p value* | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No disability n = 15 224 |

Yes disability n = 7 600 |

Moderate disability n = 4 242 |

Severe disability n = 3 358 |

||||||

|

Age, yr |

42.9 ± 13.5 |

48.8 ± 13.5 |

47.6 ± 13.7 |

50.4 ± 13.1 |

< 0.001 |

||||

| ≤ 29 |

2 945 |

(19.3) |

892 |

(11.7) |

567 |

(13.4) |

325 |

(9.7) |

|

| 30–39 |

4 106 |

(27.0) |

1 166 |

(15.3) |

734 |

(17.3) |

432 |

(12.9) |

|

| 40–49 |

3 029 |

(19.9) |

1 492 |

(19.6) |

874 |

(20.6) |

618 |

(18.4) |

|

| 50–59 |

2 748 |

(18.1) |

2 000 |

(26.3) |

1 031 |

(24.3) |

969 |

(28.9) |

|

| 60–69 |

2 396 |

(15.7) |

2 050 |

(27.0) |

1 036 |

(24.4) |

1 014 |

(30.2) |

|

| Missing |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|||||

|

Country of birth |

< 0.001 |

||||||||

| Canada |

11 899 |

(78.2) |

6 222 |

(81.9) |

3 408 |

(80.3) |

2 814 |

(83.8) |

|

| Other |

2 967 |

(19.5) |

1 253 |

(16.5) |

756 |

(17.8) |

497 |

(14.8) |

|

| Missing |

358 |

(2.4) |

125 |

(1.6) |

78 |

(1.8) |

47 |

(1.4) |

|

|

Education |

< 0.001 |

||||||||

| Less than secondary |

1 369 |

(9.0) |

1 201 |

(15.8) |

549 |

(12.9) |

652 |

(19.4) |

|

| Secondary/some postsecondary |

3 788 |

(24.9) |

1 935 |

(25.5) |

1 063 |

(25.1) |

872 |

(26.0) |

|

| Postsecondary |

10 028 |

(65.9) |

4 438 |

(58.4) |

2 620 |

(61.8) |

1 818 |

(54.1) |

|

| Missing |

39 |

(0.3) |

26 |

(0.3) |

10 |

(0.2) |

16 |

(0.5) |

|

|

Household income, $ |

< 0.001 |

||||||||

| < 30 000 |

2 170 |

(14.3) |

1 993 |

(26.2) |

879 |

(20.7) |

1 114 |

(33.2) |

|

| 30 000–59 999 |

4 056 |

(26.6) |

2 129 |

(28.0) |

1 171 |

(27.6) |

958 |

(28.5) |

|

| 60 000–99 999 |

4 288 |

(28.2) |

1 731 |

(22.8) |

1 104 |

(26.0) |

627 |

(18.7) |

|

| ≥ 100 000 |

3 569 |

(23.4) |

1 149 |

(15.1) |

761 |

(17.9) |

388 |

(11.6) |

|

| Missing |

1 141 |

(7.5) |

598 |

(7.9) |

327 |

(7.7) |

271 |

(8.1) |

|

|

Marital status |

< 0.001 |

||||||||

| Married/common Law |

9 756 |

(64.1) |

4 339 |

(57.1) |

2 544 |

(60.0) |

1 795 |

(53.5) |

|

| Widowed/single |

3 821 |

(25.1) |

2 036 |

(26.8) |

1 110 |

(26.2) |

926 |

(27.6) |

|

| Separated/divorced |

1 643 |

(10.8) |

1 222 |

(16.1) |

587 |

(13.8) |

635 |

(18.9) |

|

| Missing |

4 |

(< 0.1) |

3 |

(< 0.1) |

1 |

(< 0.1) |

2 |

(< 0.1) |

|

|

Chronic conditions |

< 0.001 |

||||||||

| 0 |

10 774 |

(70.8) |

2 502 |

(32.9) |

1 682 |

(39.7) |

820 |

(24.4) |

|

| 1 |

3 178 |

(20.9) |

2 350 |

(30.9) |

1 368 |

(32.2) |

982 |

(29.2) |

|

| ≥ 2 |

1 272 |

(8.4) |

2 748 |

(36.2) |

1 192 |

(28.1) |

1 556 |

(46.3) |

|

| Missing |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|||||

|

Rurality index |

< 0.001 |

||||||||

| 0–9 (large urban) |

8 377 |

(55.0) |

3 878 |

(51.0) |

2 200 |

(51.9) |

1 678 |

(50.0) |

|

| 10–44 (small urban) |

5 001 |

(32.8) |

2 771 |

(36.5) |

1 513 |

(35.7) |

1 258 |

(37.5) |

|

| ≥ 45 (rural) |

1 674 |

(11.0) |

862 |

(11.3) |

467 |

(11.0) |

395 |

(11.8) |

|

| Missing |

172 |

(1.1) |

89 |

(1.2) |

62 |

(1.5) |

27 |

(0.8) |

|

|

Health system contact during study period |

|||||||||

| Physician visits |

15.5 |

± 16.1 |

23.2 |

± 21.4 |

20.7 |

± 19.5 |

26.4 |

± 23.2 |

< 0.001 |

| Family physician visits |

10.7 |

± 11.7 |

15.1 |

± 15.2 |

13.8 |

± 14.3 |

16.7 |

± 16.2 |

< 0.001 |

| Specialist visits |

4.8 |

± 8.5 |

8.1 |

± 11.7 |

6.9 |

± 10.0 |

9.6 |

± 13.5 |

< 0.001 |

| Emergency department visits |

1.6 |

± 3.1 |

2.5 |

± 4.9 |

2.2 |

± 4.1 |

2.9 |

± 5.7 |

< 0.001 |

| Hospital admissions | 0.4 | ± 0.7 | 0.6 | ± 1.0 | 0.5 | ± 0.9 | 0.7 | ± 1.1 | < 0.001 |

Note: SD = standard deviation. *p values represent comparison between “no disability” and “yes disability.”

Overall, 9549/15 224(62.7%) of women with no disability had been appropriately screened for cervical cancer compared with 4073/7600 (53.6%) of women with some level of disability. Bivariable analyses were conducted for all sociodemographic variables versus level of disability (Table 2). Screening rates were persistently significantly lower for women with disability than for those without disability across sociodemographic subgroups. As well, screening rates decreased across all levels of disability as age category increased, as level of education decreased, as household income decreased, as rurality increased and as number of chronic conditions increased. Screening rates were higher for married women than for women who were widowed, single, separated or divorced. Overall, the lowest screening rate was seen among women with severe disability and less than secondary school education (33.0%) and the highest rate was seen among women with no disability and a household income of at least $100 000 per year (72.4%).

Table 2: Participants appropriately screened for cervical cancer by level of disability and sociodemographic characteristics (n = 22 824).

| Characteristic | No. screened/no. in group (%) |

p value* | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No disability n = 15 224 |

Yes disability n = 7 600 |

Moderate disability n = 4 242 |

Severe disability n = 3 358 |

||||||

|

Age, yr |

|||||||||

| ≤ 29 |

1 951/2 945 |

(66.2) |

576/892 |

(64.6) |

392/567 |

(69.1) |

184/325 |

(56.6) |

0.363 |

| 30–39 |

2 854/4 106 |

(69.5) |

751/1 166 |

(64.4) |

492/734 |

(67.0) |

259/432 |

(60.0) |

< 0.001 |

| 40–49 |

2 002/3 029 |

(66.1) |

903/1 492 |

(60.5) |

559/874 |

(64.0) |

344/618 |

(55.7) |

< 0.001 |

| 50–59 |

1 599/2 748 |

(58.2) |

1 056/2 000 |

(52.8) |

580/1 031 |

(56.3) |

476/969 |

(49.1) |

< 0.001 |

| 60–69 |

1 143/2 396 |

(47.7) |

787/2 050 |

(38.4) |

448/1 036 |

(43.2) |

339/1 014 |

(33.4) |

< 0.001 |

|

Country of birth |

|||||||||

| Canada |

7 507/11 899 |

(63.1) |

3 326/6 222 |

(53.5) |

1 999/3 408 |

(58.7) |

1 327/2 814 |

(47.2) |

< 0.001 |

| Other |

1 827/2 967 |

(61.6) |

681/1 253 |

(54.3) |

433/756 |

(57.3) |

248/497 |

(50.0) |

< 0.001 |

|

Education |

|||||||||

| Less than secondary |

621/1 369 |

(45.4) |

454/1 201 |

(37.8) |

239/549 |

(43.5) |

215/652 |

(33.0) |

0.232 |

| Secondary/some postsecondary |

2 256/3 788 |

(59.6) |

1 004/1 935 |

(51.9) |

579/1 063 |

(54.5) |

425/872 |

(48.7) |

0.001 |

| Postsecondary |

6 653/10 028 |

(66.3) |

2 602/4 438 |

(58.6) |

1 647/2 620 |

(62.9) |

955/1 818 |

(52.5) |

< 0.001 |

|

Household income, $ |

|||||||||

| < 30 000 |

1 127/2 170 |

(51.9) |

843/1 993 |

(42.3) |

411/879 |

(46.8) |

432/1 114 |

(38.8) |

< 0.001 |

| 30 000–59 999 |

2 368/4 056 |

(58.4) |

1 098/2 129 |

(51.6) |

670/1 171 |

(57.2) |

428/958 |

(44.7) |

< 0.001 |

| 60 000–99 999 |

2 837/4 288 |

(66.2) |

1 076/1 731 |

(62.2) |

706/1 104 |

(63.9) |

370/627 |

(59.0) |

0.003 |

| ≥ 100 000 |

2 583/3 569 |

(72.4) |

772/1 149 |

(67.2) |

520/761 |

(68.3) |

252/388 |

(64.9) |

0.001 |

|

Marital status |

|||||||||

| Married/common law |

6 374/9 756 |

(65.3) |

2 444/4 339 |

(56.3) |

1 542/2 544 |

(60.6) |

902/1 795 |

(50.3) |

< 0.001 |

| Widowed/single |

2 216/3 821 |

(58.0) |

1 029/2 036 |

(50.5) |

619/1 110 |

(55.8) |

410/926 |

(44.3) |

< 0.001 |

| Separated/divorced |

956/1 643 |

(58.2) |

598/1 222 |

(48.9) |

309/587 |

(52.6) |

289/635 |

(45.5) |

< 0.001 |

|

Chronic conditions |

|||||||||

| 0 |

6 948/10 744 |

(64.5) |

1 561/2 502 |

(62.4) |

1 091/1 682 |

(64.9) |

470/820 |

(57.3) |

0.049 |

| 1 |

1 922/3 178 |

(60.5) |

1 327/2 350 |

(56.5) |

815/1 368 |

(59.6) |

512/982 |

(52.1) |

0.003 |

| > 2 |

679/1 272 |

(53.4) |

1 185/2 748 |

(43.1) |

565/1 192 |

(47.4) |

620/1 556 |

(39.8) |

< 0.001 |

|

Rurality index |

|||||||||

| 0–9 (large urban) |

5 597/8 377 |

(66.8) |

2 223/3 878 |

(57.3) |

1 363/2 200 |

(62.0) |

860/1 678 |

(51.3) |

< 0.001 |

| 10–44 (small urban) |

2 997/5 001 |

(59.9) |

1 464/2 771 |

(52.8) |

874/1 513 |

(57.8) |

590/1 258 |

(46.9) |

< 0.001 |

| > 45 (rural) | 780/1 674 | (46.6) | 346/862 | (40.1) | 206/467 | (44.1) | 140/395 | (35.4) | < 0.001 |

*p values represent comparison between “no disability” and “yes disability.”

An interaction was observed between morbidity and disability with regard to cervical cancer screening (Figure 1). Across all levels of morbidity, screening rates decreased as level of disability increased, especially from moderate to severe disability. Differences in screening rates were most pronounced among women with at least 2 chronic conditions, compared with those with 1 or none, particularly between those with moderate disability versus those with no disability. Comparing the best-case and worst-case scenarios for disability and morbidity, 64.5% of women with no disability and no chronic conditions were appropriately screened compared with only 39.8% of women with severe disability and 2 or more chronic conditions.

Figure 1:

Appropriate screening for cervical cancer by level of disability and number of chronic conditions among participants (n = 22 824) in Ontario.

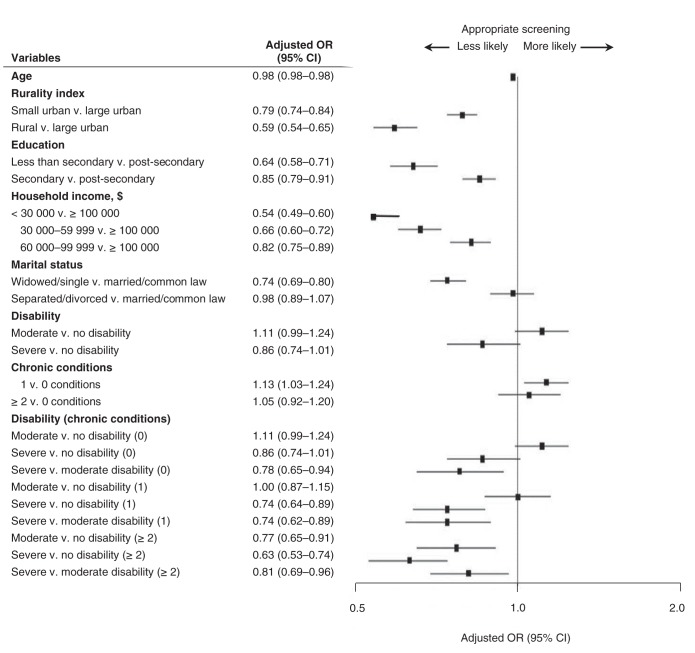

Multivariable logistic regression results are illustrated in Figure 2. The interaction between level of morbidity and level of disability remained statistically significant after adjusting for other variables (p = 0.005). Age, rurality, education, marital status and household income were also each independently associated with cervical cancer screening.

Figure 2:

Multivariable logistic regression of associations between appropriate screening for cervical cancer and demographic characteristics and levels of disability and morbidity. OR = odds ratios, CI = confidence interval.

Interpretation

In this retrospective cohort study, we found that women with disability had lower income, less education and fewer marital or common-law supports than women without disability. Socioeconomic status, disability and multimorbidity together placed them at risk of low rates of cervical cancer screening. For example, only 33.0% of women with both severe disability and less than secondary school education were screened appropriately. We found a strong interaction effect between disability and morbidity, such that increased morbidity resulted in the greatest inequalities in screening among women with severe disability.

Explanation and comparison with other studies

Our findings suggest that women with disability, particularly those with multiple chronic conditions, are not consistently receiving appropriate cervical cancer screening in Ontario, despite having more contact with the health care system and with their primary care providers than their peers. There may be several reasons for these findings. Time constraints because of competing demands during primary care visits may play a major role, namely a focus on acute medical management of the patient’s chronic conditions or disabilities.6,15,18–21 Physical limitations, both in getting to physicians’ offices and within physicians’ offices, such as getting on the examination table, have also been identified as potentially influencing screening practices for women with disabilities.8,22–25 Physicians’ “self-identified lack of confidence” (in appropriately treating patients with disabilities) has been noted in the literature.26–28 Physician recommendation is known to be an important predictor of cervical cancer screening.29,30 Our findings also suggest that there is a significant effect on screening when women with 2 or more chronic conditions move from no disability to moderate disability, but not for women with no chronic conditions or only 1. This may show that increased health care needs only become detrimental to screening at a threshold level of competing demands.

In our cohort, women were also vulnerable to under-screening because of their socioeconomic disadvantage. Women with less income and education are known to have lower cervical cancer screening rates relative to their more affluent and more educated peers,31–36 a disparity that is evident even within a universal health care system, such as Ontario’s. Research has also suggested that married women are more likely to be screened,37–42 which is consistent with our finding that women who were less likely to be screened were also less likely to be in a married or common-law relationship. These women might perceive themselves as not being at risk of cervical cancer, but current guidelines recommend triennial screening for all women who have ever been vaginally sexually active.4 Barriers to screening for socioeconomically disadvantaged women include not being able to afford transportation or child care, lack of awareness of the need for screening, low health literacy and, again, lack of physician recommendation.29,30,43–45

Our results are consistent with other Canadian and international literature. A recent multi-country study showed that disability was consistently more prevalent in the poorest than richest quintiles.46 In their population-based study, Cobigo and colleagues47 showed that the proportion of Ontario women with intellectual and developmental disabilities who were not screened for cervical cancer was nearly twice that of women without these disabilities. Multimorbidity has been strongly associated with preventable hospital admissions, and this risk is exacerbated by socioeconomic deprivation.48 Cervical cancer screening inequalities in Ontario have previously been shown among women of low income and foreign-born women,32,49,50 and cervical cancer screening rates among Ontario women with traumatic spinal cord injury have been shown to be significantly influenced by income.15 Women with an intermediate level of comorbidity have been found to have higher rates of cervical cancer screening than those with either a higher or lower level of comorbidity.51

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, some women with disability in our study may not have been appropriate candidates for cancer screening if they were not expected to live long enough to qualify for screening or were never sexually active. However, we suspect that patients in the former category would have been less likely to complete the Canadian Community Health Survey and that those in the latter category would be few, as 73% of women with a disability reported currently or previously being married or in a common-law relationship; we suspect that many of the remaining 27% (including widows) were also previously sexually active. Second, we used common definitions of disability and multimorbidity, but there is no consensus regarding a normative definition of either. Nevertheless, we found strong effects with relatively conservative cut-off values. Third, disability and multimorbidity were measured at the beginning of each woman’s 3-year study period, and these might not have remained consistent over time. However, for most women, medical complexity would likely have remained the same or worsened over time. Fourth, the potential for selection bias exists with the Canadian Community Health Survey given its voluntary nature. Fifth, we did not examine race or ethnicity; however, we did examine immigrant status. Finally, we relied on secondary administrative data that were not expressly collected for research purposes, and we were limited by what is available. For example, it is not possible to know whether the disability was primarily physical or mental, whether a patient or the provider instigated screening or how women perceived their risk of cervical cancer. Similarly, administrative data do not allow us to identify how many women were offered a Pap test but declined. However, using administrative data allowed us to conduct a large, population-based study.

Implications for practice and future research

The disparities in screening that we observed may extend to other forms of preventive health care, such as screening for other cancers and other preventable chronic conditions. Therefore, in future research, we plan to examine breast and colorectal cancer screening and screening for diabetes and hyperlipidemia. It will be important to determine whether the inequalities we observed in this study are only applicable to preventive care procedures, such as cancer screening, or if they also extend to screening that is performed by simpler measures such as blood tests.

Conclusion

In this study, we found that women with disability, especially those with comorbid conditions, were not being screened for cervical cancer at the same rate as their peers. Women with disability were also more likely to have low income and low educational attainment, both of which were associated with lower rates of cervical cancer screening independent of disability and comorbidity. With the population aging and the number of people in Ontario with complex medical and social needs increasing, policymakers should take note of these results as they work toward improving cancer screening rates.

Supplemental information

For reviewers comments and the original submission of this manuscript, please see www.cmajopen.ca/content/2/4/E240/supplDC1

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Duarte-Franco E, Franco EL. Cancer of the uterine cervix. BMC Womens Health 2004;4(Suppl 1):S13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mohar A, Frias-Mendívil M. Epidemiology of cervical cancer. Cancer Invest 2000;18:584-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Canadian cancer statistics 2006. Toronto: Canadian Cancer Society/National Cancer Institute of Canada; 2006. Available: http://publications.gc.ca/collections/Collection/CS2-37-2006E.pdf (accessed 2014 Jul. 25).

- 4.Cervical cancer screening Toronto: Cancer Care Ontario; 2012. Available: www.cancercare.on.ca/pcs/screening/cervscreening/ (accessed 2013 Oct. 28).

- 5.Guilcher SJ, Newman A, Jaglal SB. A comparison of cervical cancer screening rates among women with traumatic spinal cord injury and the general population. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2010;19:57-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boult C, Counsell SR, Leipzig RM, et al. The urgency of preparing primary care physicians to care for older people with chronic illnesses. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010;29:811-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sinnott C, Mc Hugh S, Browne J, et al. GPs’ perspectives on the management of patients with multimorbidity: systematic review and synthesis of qualitative research. BMJ Open 2013;3:e003610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smeltzer SC. Preventive health screening for breast and cervical cancer and osteoporosis in women with physical disabilities. Fam Community Health 2006;29(Suppl):35S-43S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kroll T, Jones GC, Kehn M, et al. Barriers and strategies affecting the utilisation of primary preventive services for people with physical disabilities: a qualitative inquiry. Health Soc Care Community 2006;14:284-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kiefe CI, Funkhouser E, Fouad MN, et al. Chronic disease as a barrier to breast and cervical cancer screening. J Gen Intern Med 1998;13:357-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marshall JG, Cowell JM, Campbell ES, et al. Regional variations in cancer screening rates found in women with diabetes. Nurs Res 2010;59:34-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Socio-demographic profiles of Saskatchewan women: women with disabilities Regina: Saskatchewan Ministry of Advanced Education, Employment and Labour; 2009. Available: www.socialservices.gov.sk.ca/disabled-women.pdf (accessed 2014 Mar. 20).

- 13.A profile of disability in Canada, 2001 Ottawa: Statistics Canada; 2003. Available: www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/89-577-x/index-eng.htm (accessed 2014 Mar. 20)

- 14.Participation and activity limitation survey 2006: technical and methodological report Ottawa: Statistics Canada; 2007. Available: www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/89-628-x/89-628-x2007001-eng.htm (accessed 2014 Mar. 20)

- 15.Fortin M, Lapointe L, Hudon C, et al. Multimorbidity and quality of life in primary care: a systematic review. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2004;2:51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nasmith L, Kupka S, Ballem P, et al. Achieving care goals for people with chronic health conditions. Can Fam Physician 2013;59:11-3, 15-7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kralj B. Measuring “rurality” for purposes of health-care planning: an empirical measure for Ontario. Toronto: Ontario Medical Association; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dryden DM, Saunders LD, Rowe BH, et al. Utilization of health services following spinal cord injury: a 6-year follow-up study. Spinal Cord 2004;42:513-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coyle CP, Santiago MC, Shank JW, et al. Secondary complications and women with physical disabilities: a descriptive study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2000;81:1380-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Noreau L, Proulx P, Gagnon L, et al. Secondary impairments after spinal cord injury: a population-based study. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2000;79:526-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roland M, Paddison C. Better management of patients with multimorbidity. BMJ 2013;346:f2510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schopp LH, Kirkpatrick HA, Sanford TC, et al. Impact of comprehensive gynecologic services on health maintenance behaviours among women with spinal cord injury. Disabil Rehabil 2002;24:899-903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schopp LH, Sanford TC, Hagglund KJ, et al. Removing service barriers for women with physical disabilities: promoting accessibility in the gynecologic care setting. J Midwifery Womens Health 2002;47:74-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Diab ME, Johnston MV. Relationships between level of disability and receipt of preventive health services. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2004;85:749-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Iezzoni LI, McCarthy EP, Davis RB, et al. Mobility impairments and use of screening and preventive services. Am J Public Health 2000;90:955-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Currie DM. Primary care for persons with disabilities. The physiatrist’s perspective. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 1997;76(Suppl):S25-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Werner P. Primary care for persons with disabilities. The family practice perspective. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 1997;76(Suppl):S21-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oshima S, Kirschner KL, Heinemann A, et al. Assessing the knowledge of future internists and gynecologists in caring for a women with tetraplegia. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1998;79:1270-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Akers AY, Newmann SJ, Smith JS. Factors underlying disparities in cervical cancer incidence, screening, and treatment in the United States. Curr Probl Cancer 2007;31:157-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garner EI. Cervical cancer: disparities in screening, treatment, and survival. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2003;12:242-7s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lofters A, Glazier RH, Agha MM, et al. Inadequacy of cervical cancer screening among urban recent immigrants: a population-based study of physician and laboratory claims in Toronto, Canada. Prev Med 2007;44:536-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lofters AK, Moineddin R, Hwang SW, et al. Low rates of cervical cancer screening among urban immigrants: a population-based study in Ontario, Canada. Med Care 2010;48:611-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maxwell CJ, Bancej CM, Snider J, et al. Factors important in promoting cervical cancer screening among Canadian women: findings from the 1996-97 National Population Health Survey (NPHS). Can J Public Health 2001;92:127-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Qi V, Phillips SP, Hopman WM. Determinants of a healthy lifestyle and use of preventive screening in Canada. BMC Public Health 2006;6:275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Damba C, Vahabi M. Toronto health system monitoring: equity analysis. Toronto: Toronto District Health Council; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ontario Cervical Screening Program. Program Report 2001-5. Toronto: Cancer Care Ontario; 2006.

- 37.Wang PD, Lin RS. Sociodemographic factors of Pap smear screening in Taiwan. Public Health 1996;110:123-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zambrana RE, Breen N, Fox SA, et al. Use of cancer screening practices by Hispanic women: analyses by subgroup. Prev Med 1999;29:466-77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mishra SI, Luce-Aoelua PH, Hubbell FA. Predictors of Papanicolaou smear use among American Samoan women. J Gen Intern Med 2001;16:320-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sohn L, Harada ND. Knowledge and use of preventive health practices among Korean women in Los Angeles county. Prev Med 2005;41:167-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liao CC, Wang HY, Lin RS, et al. Addressing Taiwan’s high incidence of cervical cancer: factors associated with the Nation’s low compliance with Papanicolaou screening in Taiwan. Public Health 2006;120:1170-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rodvall Y, Kemetli L, Tishelman C, et al. Factors related to participation in a cervical cancer screening programme in urban Sweden. Eur J Cancer Prev 2005;14:459-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Coughlin SS, King J, Richards TB, et al. Cervical cancer screening among women in metropolitan areas of the United States by individual-level and area-based measures of socioeconomic status, 2000 to 2002. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2006;15:2154-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Van Til L, MacQuarrie C, Herbert R. Understanding the barriers to cervical cancer screening among older women. Qual Health Res 2003;13:1116-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.De Alba I, Sweningson JM. English proficiency and physicians’ recommendation of Pap smears among Hispanics. Cancer Detect Prev 2006;30:292-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hosseinpoor AR, Stewart Williams JA, Gautam J, et al. Socioeconomic inequality in disability among adults: a multicountry study using the World Health Survey. Am J Public Health 2013;103:1278-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cobigo V, Ouellette-Kuntz H, Balogh R, et al. Are cervical and breast cancer screening programmes equitable? The case of women with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Journal of intellectual disability research. J Intellect Disabil Res 2013;57:478-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Payne RA, Abel GA, Guthrie B, et al. The effect of physical multimorbidity, mental health conditions and socioeconomic deprivation on unplanned admissions to hospital: a retrospective cohort study. CMAJ 2013;185:E221-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lofters AK, Hwang SW, Moineddin R, et al. Cervical cancer screening among urban immigrants by region of origin: a population-based cohort study. Prev Med 2010;51:509-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lofters AK, Moineddin R, Hwang SW, et al. Predictors of low cervical cancer screening among immigrant women in Ontario, Canada. BMC Womens Health 2011;11:20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lofters AK, Hwang SW, Moineddin R, et al. Cervical cancer screening among urban immigrants by region of origin: a population-based cohort study. Prev Med 2010;51:509-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.