Abstract

Background

The increased use of opioid analgesics, sedative hypnotics and stimulants, coupled with the associated risks of overdose have raised concerns around the inappropriate prescribing of these monitored drugs. We assessed the impact of new legislation, the Narcotics Safety and Awareness Act, and a centralized Narcotics Monitoring System (implemented November 2011 and May 2012, respectively), on the dispensing of prescriptions suggestive of misuse.

Methods

We conducted a time series analysis of publicly funded prescriptions for opioids, benzodiazepines and stimulants dispensed monthly in Ontario from January 2007 to May 2013, based on information in the Ontario Public Drug Benefit Database. In the primary analysis, a prescription was deemed potentially inappropriate if it was dispensed within 7 days of an earlier prescription and was for at least 30 tablets of a drug in the same class as the earlier prescription, but originated from a different physician and a different pharmacy.

Results

After enactment of the new legislation, the prevalence of potentially inappropriate opioid prescriptions decreased by 12.5% in 6 months (from 1.6% in October 2011 to 1.4% in April 2012; p = 0.01). No further significant change was observed after the introduction of the narcotic monitoring system (p = 0.8). By May 2013, the prevalence had dropped to 1.0%. Inappropriate benzodiazepine prescribing was significantly influenced by both the legislation (p < 0.001) and the monitoring system (p = 0.05), which together reduced potentially inappropriate prescribing by 50.0% between October 2011 and May 2013 (from 0.4% to 0.2%). The prevalence of potentially inappropriate prescribing of stimulants was significantly influenced by the introduction of the monitoring system in May 2012, falling from 0.7% in April 2012 to 0.3% in May 2013 (p = 0.02).

Interpretation

For a select group of drugs prone to misuse and diversion, legislation and a prescription monitoring program reduced the prevalence of prescriptions suggestive of misuse. This suggests that regulatory interventions can promote appropriate prescribing which could potentially be applied to other jurisdictions and drugs of concern.

Misuse of drugs, including opioid analgesics, sedative hypnotics and stimulants can have serious consequences: in the United States, more than 20 000 deaths are ascribed to prescription drug overdose each year.1 Furthermore, Canada has one of the highest rates of opioid use per capita in the world.2,3 Increased use of these prescription drugs, along with trends highlighting the substantial risks of death from overdose among those receiving prescriptions for these medications in Ontario, has led to considerable concern among physicians, public health officials and regulatory authorities. As governments attempt to curb inappropriate use of prescribed drugs, the regulation and monitoring of these medications has become increasingly important. Prescription monitoring programs that track detailed patient and prescriber information related to controlled substances have been implemented in many jurisdictions across North America, with varying degrees of success.4–7 Although some studies have suggested that these programs have a substantial impact on the supply of monitored drugs and the rates of drug abuse and misuse,8–10 their quality is variable, and their success relies on a variety of factors, including access to data by health care providers, engagement of pharmacists and the involvement of law enforcement.6,8,11,12

In November 2011, the Narcotics Safety and Awareness Act (NSAA) was implemented in Ontario, Canada, requiring physicians to identify themselves by their college registration number and pharmacists to record and verify patient information (including name, address, age, sex and government-issued identification number) on prescriptions for all narcotics and other controlled substances dispensed in the province. Furthermore, this information must be disclosed to government officials on request.13

Another key component of this legislation is the Narcotics Monitoring System (NMS), which captures prescriber, pharmacist and patient information for all narcotics and other controlled drugs dispensed in Ontario, regardless of payment type (e.g., cash, private insurance or public drug program). The NMS was created to provide provincial policy-makers with the tools to identify potentially inappropriate prescribing of monitored drugs. This information could lead to educational interventions and the reporting of potential misconduct or criminal activity to regulatory and law enforcement agencies.14 Although full patient profiles associated with all prescriptions in the NMS system are accessible to physicians and pharmacists, pharmacists are now provided with more information in drug utilization review messages (alerts), including conflicting drugs, quantities and other dispensing pharmacies.14 Pharmacies began submitting dispensing information through the NMS on April 16, 2012, with full implementation on May 12, 2012.

The objective of this study was to evaluate the impact of the NSAA and the NMS on the rate of dispensing monitored drugs to beneficiaries of the public drug plan in Ontario that was highly likely to represent misuse.

Methods

We conducted a population-based, cross-sectional, time-series analysis of all publicly funded prescriptions for drugs monitored by the NMS between Jan. 1, 2007 and May 31, 2013. Ontario residents are eligible for public drug coverage if they are unemployed or disabled, have high prescription drug costs in relation to their net household income, receive home care, reside in a long-term care facility or are 65 years of age or older. All Ontario residents have universal access to hospital care and physician services.

Data sources

We used the computerized records of the Ontario Public Drug Benefit Database to identify all prescriptions dispensed to Ontario public drug plan beneficiaries for drugs monitored by the NMS.15 This database contains the date, quantity and days supplied for each prescription, as well as encrypted patient, prescriber and pharmacy identifiers. It has an error rate of less than 1%16 and is regularly used to study drug use at the population level. To restrict our study to adults receiving these drugs in the community, we excluded prescriptions dispensed to residents in long-term care homes and people younger than 18 years. We restricted our analysis to opioids, benzodiazepines and stimulants monitored by the NMS. (See Appendix at www.cmajopen.ca/content/2/4/E256/suppl/DC1).We excluded prescriptions with missing prescriber identifiers and non-tablet formulations with the exception of fentanyl. To test the robustness of our analysis, we also examined prescriptions for non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), which are not monitored by the NMS, reasoning that the rate of inappropriate prescribing of these medications should not change because they are not prone to abuse.

Definition of potentially inappropriate prescribing

We defined potentially inappropriate prescriptions of monitored drugs as those we believed were highly likely to represent misuse. This was measured in 2 ways. In our primary analysis, we defined a prescription as potentially inappropriate based on previously used criteria.9 We first identified all prescriptions for a monitored drug where at least 30 tablets (or 6 transdermal fentanyl patches) were dispensed. We then identified all prescriptions for drugs within the same drug class (i.e., opioid, benzodiazepine, stimulant or NSAID) that were dispensed in the 7 days following the initial prescription. The subsequent prescription was deemed inappropriate if it was issued by a different physician and dispensed at a different pharmacy from the initial prescription.

In a secondary analysis, we defined potentially inappropriate prescribing using the drug utilization review criteria incorporated into the NMS. These criteria warn pharmacists of potential multi-doctoring and polypharmacy based on prescription patterns over a 28-day period. Specifically, a prescription raises a warning of multi-doctoring if a patient obtains any combination of monitored drugs prescribed by 3 or more different physicians over a 28-day period. Similarly, polypharmacy warnings appear when monitored drugs are dispensed by 3 or more different pharmacies over 28 days. We defined potentially inappropriate prescriptions as those that would have led to the issuance of both a double-doctoring warning and a polypharmacy warning.

In sensitivity analyses, we broadened the definition used in the primary analysis, such that prescriptions were flagged as potentially inappropriate if they were issued by either a different doctor or a different pharmacy. We conducted all analyses at the prescription level; therefore, if a patient was treated with drugs from multiple classes (i.e., opioids, benzodiazepines and stimulants), we considered all such prescriptions separately.

Statistical analysis

We calculated the monthly number and prevalence (percentage of all prescriptions) of potentially inappropriate prescriptions by drug class. We used interventional autoregressive integrated moving average models to examine the impact of the enactment of the NSAA (November 2011) and the full implementation of the NMS (May 2012) on the prevalence of potentially inappropriate prescribing of monitored drugs in Ontario (see Appendix at www.cmajopen.ca/content/2/4/E256/suppl/DC1 for details of study design and time-series analyses). The effects of the NSAA and NMS were assessed using a ramp intervention function in the autoregressive integrated moving average model. The autocorrelation, partial autocorrelation and inverse autocorrelation functions were assessed for model parameter appropriateness and seasonality, and stationarity was examined using autocorrelation functions and the augmented Dickey-Fuller test. Finally, the presence of white noise was assessed by examining the autocorrelations at various lag times using the Ljung–Box test. Final model specifications can be found in the Appendix at www.cmajopen.ca/content/2/4/E256/suppl/DC1 (eTable 1). All analyses used a type 1 error rate of 0.05 as the threshold for statistical significance and were carried out using SAS statistical software (v 9.3; SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Ethics approval

This project was approved by the Research Ethics Board of Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, Toronto.

Results

Over the 77-month study period, 49 578 359 opioid prescriptions were dispensed to 1 706 502 public drug plan beneficiaries, 21 469 883 benzodiazepine prescriptions to 928 240 beneficiaries and 1 066 834 stimulant prescriptions to 34 902 beneficiaries. Of these, 801 882 (1.6%) opioid prescriptions, 75 789 (0.4%) benzodiazepine prescriptions and 7794 (0.7%) stimulant prescriptions were deemed to be potentially inappropriate according to our primary definition.

Primary analysis

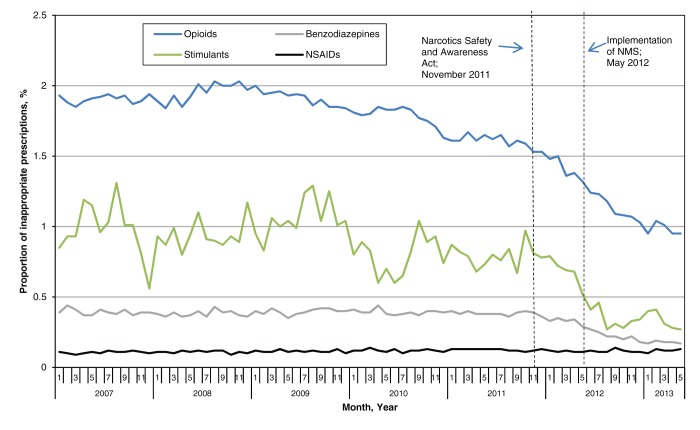

Before enactment of the NSAA (January 2007 to October 2011), a monthly average of 10 487/575 815 (1.8%) of opioid prescriptions, 102/11 450 (0.9%) of stimulant prescriptions and 1053/270 194 (0.4%) of benzodiazepine prescriptions were deemed potentially inappropriate according to our primary definition (Figure 1).

Figure 1:

Prevalence of potentially inappropriate prescriptions in Ontario, by monitored drug, before and after introduction of safety legislation and a monitoring program, January 2007 to May 2013.

The prevalence of potentially inappropriate opioid prescriptions decreased 40.3%, from 1.6% to 1.0%, between October 2011 (before any regulatory changes) and the end of our study period. In particular, this prevalence fell by 12.5% following the enactment of the NSAA, from 1.6% (12 346/777 950) in October 2011 to 1.4% (11 046/802 143) in April 2012 (p = 0.01). Although the subsequent implementation of the NMS did not lead to any further statistically significant reduction in the rate of inappropriate prescribing (p = 0.8), the prevalence of potentially inappropriate prescriptions continued to fall another 31.2% between April 2012 and May 2013, reaching 1.0% (9138/959 898) by the end of the study period.

In comparison, the prevalence of potentially inappropriate prescriptions for benzodiazepines decreased significantly following both the enactment of the NSAA (p < 0.001) and implementation of the NMS (p = 0.05). Overall, the prevalence of potentially inappropriate benzodiazepine prescriptions decreased 50.0%, from 0.4% (1198/302 716) in October 2011 (before any changes) to 0.2% (580/331 852) in May 2013 (the end of the study period).

Finally, the prevalence of potentially inappropriate stimulant prescriptions did not decrease significantly following the regulatory requirements imposed in November 2011 (p = 0.06), but did decrease significantly following implementation of the NMS (p = 0.02). Specifically, the prevalence of potentially inappropriate stimulant prescriptions decreased 57.1%, from 0.7% (138/20 242) in April 2012 (before implementation of NMS) to 0.3% (67/24 879) in May 2013.

The prevalence of potentially inappropriate NSAID prescribing was low over the entire study period, with a monthly average of 0.11% (n = 232 prescriptions) (0.09% [n = 181] to 0.14% [n = 297]). As expected, we found no change in rates of inappropriate NSAID prescribing following the introduction of either the NSAA or the NMS (Figure 1; p = 0.3 and p = 0.9, respectively).

Secondary analysis: drug utilization review warnings

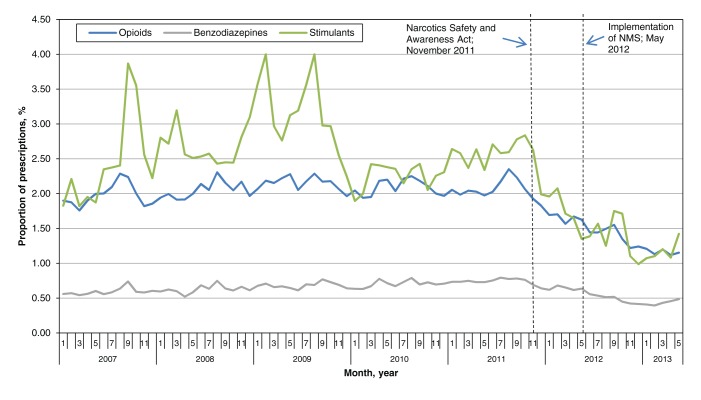

The findings of an analysis of the prevalence of prescriptions triggering drug utilization review warnings for both polypharmacy and multi-doctoring were generally consistent with our primary analyses. Overall, the prevalence of opioid prescriptions that would have triggered both types of warnings decreased 19.0% following enactment of the NSAA, from 2.1% (16 060/777 950) in October 2011 to 1.7% (13 420/802 143) in April 2012 (p < 0.001). This prevalence dropped a further 31.1% following implementation of the NMS, to 1.2% (11 062/959 898) in May 2013 (p < 0.001; Figure 2). Similarly, the 36.5% reduction in benzodiazepine prescriptions that would have triggered both types of warnings, from 0.8% (2312/302 716) in October 2011 to 0.5% (1609/331 852) in May 2013, was driven by both the enactment of the NSAA (19.1% reduction from October 2011 to April 2012; p = 0.01) and the implementation of the NMS (21.5% reduction from April 2012 to May 2013; p = 0.02). Finally, the prevalence of stimulant prescriptions that would have triggered both warnings decreased 41.8% following the regulatory changes in November 2011, from 2.8% (546/19 251) in October 2011 to 1.7% (334/20 242) in April 2012 (p = 0.04), but was not affected by the implementation of the NMS (1.4%, 354/24 879 in May 2013; p = 0.1).

Figure 2:

Prevalence of opioid, benzodiazepine and stimulant prescriptions triggering drug utilization review warnings of both double-doctoring and polypharmacy in Ontario before and after introduction of safety legislation and a monitoring program, January 2007 to May 2013.

Sensitivity analysis

In our sensitivity analysis, we loosened the criteria for potentially inappropriate prescriptions to require only a warning of double-doctoring or polypharmacy. Using these loosened criteria, 2.8% of opioid prescriptions, 1.0% of benzodiazepine prescriptions and 1.2% of stimulant prescriptions were deemed potentially inappropriate over the study period. For both opioids and benzodiazepines, the results were consistent with the primary analysis. For opioids, we found a significant reduction in the proportion of potentially inappropriate prescriptions following the enactment of the NSAA (5.6% reduction from October 2011 to April 2012; p = 0.03), but no further significant reduction after the implementation of the NMS (p = 0.4). Similarly, for benzodiazepines, we found a significant reduction in the proportion of potentially inappropriate prescriptions after both the enactment of the NSAA (12.5% reduction from October 2011 to April 2012; p < 0.001) and the implementation of the NMS (19.8% reduction from April 2012 to May 2013; p = 0.03). However, for stimulant prescriptions, the sensitivity analysis found a significant impact of the enactment of the NSAA (28.0% reduction from October 2011 to April 2012; p = 0.02), but no further impact from the NMS (p = 0.2). This is in contrast to the primary analysis, where the NSAA had a marginally non-significant impact and the NMS had a significant impact on reducing potentially inappropriate prescribing of stimulants.

Interpretation

In this population-based study, we found that both a legislative intervention and the introduction of a prescription monitoring program specifically developed for opioids and controlled substances resulted in significant reductions in the prevalence of potentially inappropriate prescribing of monitored drugs in Ontario, ranging between 40% and 60%. Because of our strict definitions of misuse, the monthly proportion of potentially inappropriate prescriptions seldom exceeded 2%. However, more than 70 million prescriptions for monitored drugs were dispensed over the 6.5-year study period; of these, almost 1 million were deemed highly likely to represent misuse. Given our conservative definitions, the true number of inappropriate prescriptions is likely to be even higher. As a result, despite the relatively small absolute prevalence of inappropriate prescriptions observed in this study, the public health impact of reductions in this prevalence is likely substantial. These findings show the potential for regulatory interventions driven by policy-makers to influence prescribing and dispensing patterns of controlled substances, and suggest that the impacts of these interventions can be quickly realized.

Comparison with other studies

The findings of this study align with another Canadian study that used similar methods to assess the impact of the implementation of British Columbia’s PharmaNet system in 1995 on inappropriate prescribing.9 Although the PharmaNet system captures all drugs (compared with the limited list of drugs monitored by Ontario’s NMS), the researchers reported a 33% reduction in inappropriate opioid prescribing and a 49% reduction in inappropriate benzodiazepine prescribing, which is consistent with, but slightly lower than our findings of 40% and 58%, respectively. This suggests that, although the products available and the rates of use and abuse of these drugs (particularly opioids) have changed substantially since that time,17 the value of prescription monitoring programs that allow pharmacists access to real-time data on patient prescribing history remains high.

Limitations

Several limitations of the analyses merit emphasis. First, our findings are limited to publicly funded prescription drugs (approximately 43% of all drug costs in Ontario18) and may not be applicable more generally. However, because the NMS tracks prescriptions for all monitored drugs dispensed in Ontario, it is likely that these findings extend to those paying through private insurance or out of pocket. Regardless, because we only identify publicly funded prescriptions, the number of potentially inappropriate prescriptions estimated in this study is likely a substantial underestimate of the true number of inappropriate prescriptions dispensed in Ontario, highlighting the public health importance of these findings.

Second, defining inappropriate prescriptions using administrative databases can be difficult, and it is possible that some prescriptions defined as inappropriate were the result of appropriate switching of medications. However, we expect that this would apply equally before and after implementation of the NMS, and, therefore, this limitation would not likely influence the trends observed in this study. We developed 2 definitions of potentially inappropriate prescribing that incorporated early prescription refills, multi-doctoring and polypharmacy. These definitions were designed to be conservative and specific and are likely to misclassify prescriptions of shorter duration or those that met only one of the multi-doctoring or polypharmacy requirements. Furthermore, our study excluded prescriptions with missing prescriber identifiers, which may be more likely to be inappropriate. Therefore, our study likely underestimates the true prevalence of inappropriate prescribing of monitored drugs in Ontario. However, the consistency of findings between the 2 definitions of potentially inappropriate use, along with the null finding for our tracer drug class (NSAIDs), suggest a true association between regulatory and prescription monitoring changes in Ontario and reductions in inappropriate prescribing.

Third, because of the small number of prescriptions for stimulants identified in this analysis, there is considerable variation in estimates of potentially inappropriate use of these drugs over time. Despite this, we were able to specify robust time-series models that evaluated the impact of the policy interventions.

Finally, we did not assess whether these changes in prescribing patterns resulted in fewer hospital admissions or deaths related to drug overdoses. Studies evaluating the impact of the legislation and NMS on patient outcomes should be done as soon as sufficient data are available.

Conclusion

The enactment of legislation requiring patient identification on prescriptions for monitored drugs and a prescription monitoring program providing real-time data access to pharmacists led to substantial reductions in the prevalence of prescriptions for opioids and controlled substances that were highly likely to represent misuse. Given that hundreds of thousands of inappropriate prescriptions for these drugs are dispensed each year in Ontario, these findings highlight the potential impact that drug policy-makers, legislators and front-line health care professionals can have in reducing harmful prescribing behaviours.

Supplemental information

For reviewer comments and the original submission of this manuscript, please see www.cmajopen.ca/content/2/4/E256/suppl/DC1

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Diana Martins for her assistance with the analyses in this study. This study was supported by a grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care’s Drug Innovation Fund and the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences, a non-profit research institute sponsored by the ministry. The design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data; and preparation and review of the manuscript were conducted by the authors independent of the funding sources. No endorsement by the institute or the Ontario ministry is intended or should be inferred. Dr. Muhammad Mamdani has received honoraria from Boehringer Ingelheim, Pfizer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Bayer. All other authors report no conflicts of interest. We thank Brogan Inc., Ottawa for use of their Drug Product and Therapeutic Class Database.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) . Vital signs: overdoses of prescription opioid pain relievers — United States, 1999–2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2011;60:1487-92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Opioid consumption motion chart Vienna (Austria): International Narcotics Control Board; 2012. Available: http://ppsg-production.heroku.com/chart (accessed 2013 Nov. 18)

- 3.Estimated World Requirements for 2014. Vienna (Austria): International Narcotics Control Board, United Nations; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4.State prescription drug monitoring programs [serial online]. Springfield (VA): Office of Diversion Control, US Department of Justice; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reisman RM, Shenoy PJ, Atherly AJ, et al. Prescription opioid usage and abuse relationships: an evaluation of state prescription drug monitoring program efficacy. Subst Abuse 2009;3:41-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Green TC, Mann MR, Bowman SE, et al. How does use of a prescription monitoring program change pharmacy practice? J Am Pharm Assoc (2003) 2013;53:273-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Green TC, Mann MR, Bowman SE, et al. How does use of a prescription monitoring program change medical practice? Pain Med 2012;13:1314-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Simeone R, Holland L. An evaluation of prescription drug monitoring programs Albany (NY): Simeone Associates; 2006. Available: www.simeoneassociates.com/simeone3.pdf (accessed 2013 Nov. 18).

- 9.Dormuth CR, Miller TA, Huang A, et al. Effect of a centralized prescription network on inappropriate prescriptions for opioid analgesics and benzodiazepines. CMAJ 2012;184:E852-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reifler LM, Droz D, Bailey JE, et al. Do prescription monitoring programs impact state trends in opioid abuse/misuse? Pain Med 2012;13:434-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gilson AM, Fishman SM, Wilsey BL, et al. Time series analysis of California’s prescription monitoring program: impact on prescribing and multiple provider episodes. J Pain 2012;13:103-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Green TC, Zaller N, Rich J, et al. Revisiting Paulozzi et al.’s “Prescription drug monitoring programs and death rates from drug overdose.” Pain Med 2011;12:982-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.The Narcotics Safety and Awareness Act, 2010 Toronto: Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care; 2010. Available: www.health.gov.on.ca/en/public/programs/drugs/ons/ons_legislation.aspx (accessed 2013 Nov. 18)

- 14.Narcotic monitoring system (NMS): pharmacy reference manual [version 1.2]. Toronto: Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Monitored drugs list. Toronto: Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care; 2014. Available: www.health.gov.on.ca/en/pro/programs/drugs/monitored_productlist.aspx (accessed 2013 Jun. 14).

- 16.Goel, V, Williams, J, Anderson, G, et al. Patterns of health care in Ontario. 2nd ed. Ottawa: Canadian Medical Association; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gomes T, Juurlink DN, Dhalla IA, et al. Trends in opioid use and dosing among socio-economically disadvantaged patients. Open Med 2011;5:e13-22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.2011/12 report card — Ontario drug benefit program Toronto: Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care; 2012. Available: www.health.gov.on.ca/en/public/programs/drugs/publications/opdp/docs/odb_report_11.pdf (accessed 2013 Nov. 18)

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.