Abstract

Background

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) causes gastrointestinal dysfunction and increased intestinal permeability. Regulation of the gut barrier may involve the central nervous system. We hypothesize that vagal nerve stimulation prevents an increase in intestinal permeability after TBI.

Methods

Balb/c mice underwent a weight drop TBI. Selected mice had electrical stimulation of the cervical vagus nerve before TBI. Intestinal permeability to 4.4 kDa FITC-Dextran was measured 6 hours after injury. Ileum was harvested and intestinal tumor necrosis factor-α and glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), a marker of glial activity, were measured.

Results

TBI increased intestinal permeability compared with sham, 6 hours after injury (98.5 μg/mL ± 12.5 vs. 29.5 μg/mL ±5.9 μg/mL; p < 0.01). Vagal stimulation prevented TBI-induced intestinal permeability (55.8 ±4.8 μg/mL vs. 98.49 μg/mL ±12.5; p < 0.02). TBI animals had an increase in intestinal tumor necrosis factor-α 6 hours after injury compared with vagal stimulation + TBI (45.6 ± 8.6 pg/mL vs. 24.1 ± 1.4 pg/mL; p < 0.001). TBI increased intestinal GFAP 6.2-fold higher than sham at 2 hours and 11.5-fold higher at 4 hours after injury (p < 0.05). Intestinal GFAP in vagal stimulation + TBI animals was also 6.7-fold higher than sham at 2 hours, however, intestinal GFAP was 18.0-fold higher at 4 hours compared with sham and 1.6-fold higher than TBI alone (p < 0.05).

Conclusion

In a mouse model of TBI, vagal stimulation prevented TBI-induced intestinal permeability. Furthermore, vagal stimulation increased enteric glial activity and may represent the pathway for central nervous system regulation of intestinal permeability.

Keywords: Traumatic brain injury, Intestinal permeability, Vagus nerve, TNF-α

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) continues to be a major medical problem in the United States contributing over 4 billion dollars annually to healthcare cost and loss of productivity.1 Patients surviving the initial TBI often succumb to a natural systemic and extraneural physiologic cascade of inflammatory mediators that alter physiologic homeostasis leading to sepsis, multisystem organ failure, and eventually death.2,3 We and others have shown intestinal dysfunction, specifically blunting and necrosis of intestinal villi and increased intestinal permeability, can occur as early as 6 hours after TBI.4,5 The resultant loss in intestinal homeostasis may lead to bacterial translocation and subsequent sepsis. Several mechanisms have been implicated in the genesis of intestinal dysfunction after TBI, including the release of pro-inflammatory cytokine, loss of intestinal tight junction proteins, and increased adrenergic tone.5–7 However, as the concept of the neuroenteric axis emerges as a mechanism in the pathogenesis of gastrointestinal disease, further studies investigating the role of the central nervous system in maintaining intestinal homeostasis after TBI is warranted. The vagus nerve serves as the major conduit linking the central nervous system to the gastrointestinal system.8 Histologic evidence has shown close juxtaposition of gastrointestinal glial cells to intestinal mucosa and intestinal lymphoid tissue in mice, including the presence of vagus nerve nicotinic acetylcholine receptors at the junction of the nerve endings.9 Therefore, we hypothesized, that electrical stimulation of the vagus nerve would prevent intestinal dysfunction and injury after TBI.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mouse TBI Model

Animal experiments, including anesthesia, TBI, and recuperation, were approved through the University of California San Diego Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Male balb/c mice (20–24 g) were used and placed under a 12-hour light and dark cycle (Jackson Laboratory, Sacramento, CA). A weight drop TBI model, as previously described, was used to create a well-defined cerebral contusion.5,10 Animals were anesthetized with 3% inhaled isoflurane. Each animal (n ≥4 in each group) was manually secured and its head shaved with an electric clipper. A vertical incision was made over the cranium and using a surgical drill, a burr hole, 4 mm in diameter, 1 mm lateral, and 1 mm posterior to the bregma was created to expose the dura mater. A 250 g metal rod was dropped from a height of 2 cm onto exposed dura mater. The incision was closed with vet bond and buprenorphine (100 μL) was injected subcutaneously for analgesia in all animals. Food and water were provided ad libitum. Sham animals underwent an identical procedure, excluding the weight drop. Vagal stimulation animals underwent electrical nerve stimulation immediately preceding TBI (described in detail below). Six hours after TBI or sham procedure, animals underwent an in vivo intestinal permeability assay (described in detail below) or were sacrificed with inhaled isoflurane and underwent removal of the terminal ileum, which was either snap frozen for protein extraction or stored in formalin for histologic evaluation.

Vagal Nerve Stimulation

After induction of general anesthesia with inhaled isoflurane, a right cervical neck incision was performed and the right cervical vagus nerve exposed. Vagal nerve stimulation was performed using a VariStim III probe (Medtronic Xomed, Jacksonville, FL) at 2 mA for 10 minutes. The incision was closed with interrupted silk sutures and the animal was immediately subjected to TBI as previously described. Sham animals underwent right cervical incision and exposure of the vagus nerve but did not receive stimulation.

Histologic Evaluation

Segments of distal ileum, previously stored in formalin, were embedded in paraffin blocks. Sections were cut, placed onto glass slides, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H & E, Richard Allen Scientific). Images were later obtained using Q-imaging software and an Olympus IX70 light microscope. A pathologist, blinded to the groups, examined each ileum specimen and scored each specimen using a modified histopathologic score as described by Cuzzocrea et al.11 A scale of 0 to 3 was used to assess intestinal damage: 0 = normal, no damage; 1 = mild, focal epithelial edema and necrosis; 2 = moderate, diffuse swelling or necrosis of the villi; 3 = severe, diffuse necrosis of the villi; with evidence of neutrophil infiltration in the submucosa or hemorrhage.

In Vivo Intestinal Permeability Assay

Animals underwent an in vivo intestinal permeability assay at 6 hours after TBI according to the method previously described by Costantini et al.12 Six hours after TBI or vagal stimulation + TBI or sham operation, animals were anesthetized by inhaled isoflurane. A midline laparotomy was performed, the cecum was located, and a 5 cm segment of distal ileum was eviscerated and isolated between silk ties. Previously prepared FITC-Dextran (25 mg 4.4 kDa FITC-Dextran in 200 μL phosphate-buffered saline) was injected into the lumen of the isolated ileum. The eviscerated intestine was returned into the abdominal cavity and the abdominal wall was closed using silk suture. Thirty minutes after FITC-Dextran injection, blood was collected by cardiac puncture. Blood samples were placed into heparinized eppendorf tubes and centrifuged at 10,000 g for 10 minutes. Plasma was removed and subsequently assayed using a SpectraMax M5 fluorescence spectrophotometer (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) to determine the concentration of FITC-Dextran. A standard curve for the assay was obtained through the serial dilution of FITC-Dextran in mouse serum.

Polymerase Chain Reaction of Intestinal Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein (GFAP)

Distal ileum was preserved in RNA later solution and stored at −20°C for no longer than 6 months. RNA was extracted from tissue and treated with DNAse using the RNAqueous 4 polymerase chain reaction (PCR) kit (Ambion, Austin, TX). Reverse transcription was performed using the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription kit (Applied Biosciences, Pleasanton, CA). Control for ± Reverse Transcriptase PCR was performed separately using Platinum PCR Supermix (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Reverse transcription quantitative PCR reactions were run with iQ Sybr Green Supermix (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) for 40 cycles on a Bio-Rad iQ5 Real-time PCR detection system. Cycles were run at 95°C for 3 minutes, 95°C for 10 seconds, 60°C for 30 seconds, 72°C for 30 seconds. Steps 2 to 4 were repeated for 40 cycles. A melt curve was obtained to ensure that only a single species was amplified. The GFAP primer forward 5′-GAGGAGGAGATCCAGTTCTTAAGGA-3′, reverse 5′-GCCTCGTATTGAGTGCGAATC-3′was used. Samples were normalized against Beta-actin and relative expression levels were calculated using the ΔΔCT method.

Levels of Intestinal TNF-α

Protein was extracted from terminal ileum by homogenizing tissue in 500 μL of ice cold tissue protein extraction reagent containing 1% protease inhibitor and 1% phosphatase inhibitor (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL). Homogenates were centrifuged at 10,000 g for 5 minutes. The supernatant was obtained and stored at −70°C. Intestinal tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) were measured in sham or at 2, 4, and 6 hours after TBI ± vagal stimulation using a commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) assay (R & D system, Minneapolis, MN). Values are reported as pg/mL.

Statistical Analysis

Values are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean. The statistical significance among groups was determined by t test or analysis of variance with Bonferroni correction where appropriate, and a p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

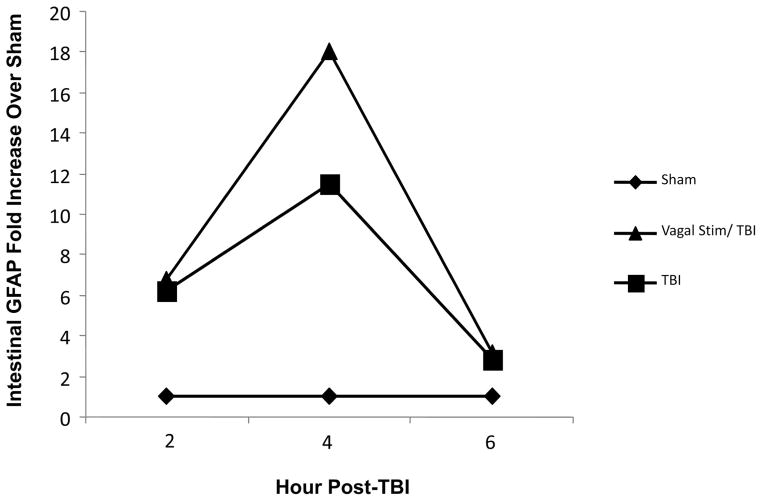

Intestinal Permeability

In vivo intestinal permeability was determined 6 hours after either sham or TBI ± vagal nerve stimulation by spectrophotometric measurement of plasma 4.4 kDa FITC-dextran. TBI caused a marked increase in intestinal permeability (98.5 ± 12.5 μg/mL) compared with sham (29.5 ± 5.9 μg/mL) after 6 hours (p < 0.001) (Fig. 1). In animals undergoing vagus stimulation +TBI, intestinal permeability was significantly reduced when compared with TBI alone (55.8 ± 4.8 μg/mL vs. 98.49 ± 12.5 μg/mL; p < 0.02).

Figure 1.

Intestinal permeability (25 mg 4.4 kDa FITC-Dextran in 200 μL phosphate-buffered saline) injected into the terminal ileum 6 hours after procedure. TBI increased intestinal permeability (98.5 μg/mL ± 12.5) compared with sham (29.5 μg/mL ± 5.9); (*p < 0.001). Vagus stimulation + TBI significantly reduced intestinal permeability when compared with TBI alone (55.8 μg/mL ± 4.8 vs. 98.49 μg/mL ± 12.5; **p < 0.02).

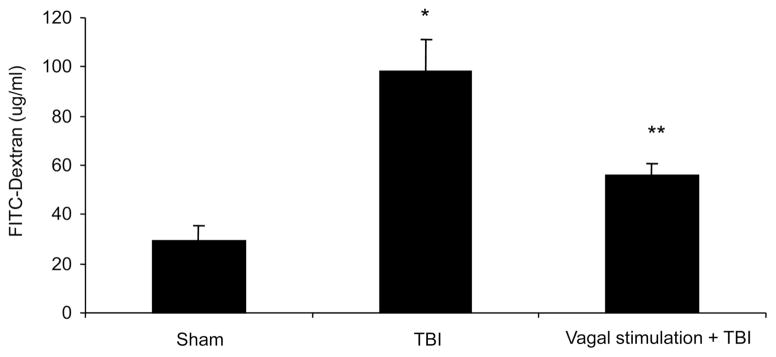

Histopathologic Evaluation

The terminal ileum was harvested 6 hours after sham, TBI, and vagal stimulation + TBI for histologic analysis using H & E staining (Fig. 2). Sham animals had normal appearing villi with normal villous height and no evidence of intestinal necrosis. The histologic appearance of intestinal specimens from TBI animals were notable for marked intestinal villi architectural deformity and necrosis The degree of mean intestinal injury was increased in the TBI group (2.8 ± 0.5) when compared with sham animals (0.3 ± 0.5; p < 0.001). In comparison, vagal nerve stimulation preserved intestinal architecture (0.5 ± 0.6) and terminal ileum histopathology was unchanged in the vagal nerve + TBI groups compared with sham (p = 0.62).

Figure 2.

Representative H & E staining and microscopy (60×) from terminal ileum was harvested 6 hours after sham, TBI, or vagal stimulation + TBI. Sham animals had normal appearing villi with consistent villous height. TBI caused blunting of intestinal villi and necrosis. Vagal stimulation prevented intestinal injury with histology showing intestinal architecture unchanged from sham.

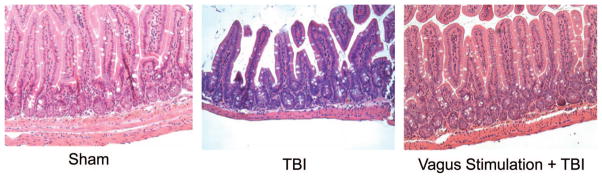

Intestinal TNF-α Levels

Levels of TNF-α were measured by ELISA in intestinal extracts at 2, 4, and 6 hour intervals after injury (Fig. 3). TBI animals had a consistent increase in intestinal TNF-α at each hourly interval (2 hour: 36.9 ± 5.3 pg/mL; 4 hour: 40.5 ± 1.8 pg/mL; 6 hour: 45.6 ± 8.6 pg/mL). Vagal stimulation prevented an increase in TNF-α after TBI at each time-point (2 hour: 24.7 ± 4.8 pg/mL; 4 hour: 23.9 ± 3.4 pg/mL; 6 hour: 24.1 ± 1.4 pg/mL; p < 0.001).

Figure 3.

TNF-α as measured by ELISA in intestinal extracts at 2, 4, and 6 hour intervals after injury. TBI animals increased in intestinal TNF-αat each hourly interval (2 hour: 36.9 ± 5.3 pg/mL; 4 hour: 40.5 ± 1.8 pg/mL; 6 hour: 45.6 ± 8.6 pg/mL). Vagal stimulation prevented an increase in TNF-αafter TBI at each time-point (2 hour: 24.7 ± 4.8 pg/mL; 4 hour: 23.9 ± 3.4 pg/mL; 6 hour: 24.1 ± 1.4 pg/ mL; *p < 0.01; **p < 0.001).

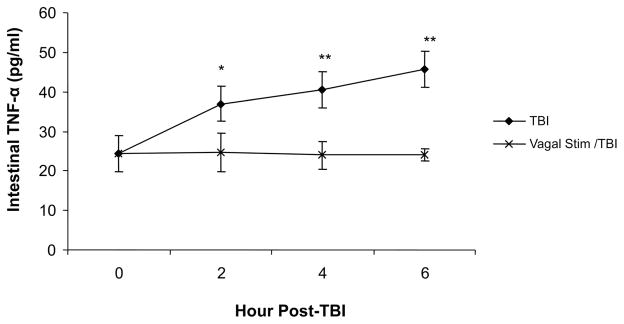

PCR of Intestinal GFAP

To depict trends of intestinal GFAP activation after TBI and vagus stimulation + TBI, GFAP was measured at 2, 4, and 6 hour intervals after injury through PCR in harvested terminal ileum (Fig. 4). Intestinal GFAP in the TBI group was 6.2-fold higher than sham at 2 hours and 11.5-fold higher at 4 hours after injury. In vagal stimulation + TBI animals, intestinal GFAP was 6.7-fold higher than sham at 2 hours, however, intestinal GFAP was 18.0-fold at 4 hours after injury compared with sham and 1.6-fold higher than TBI alone. At 6 hours after injury TBI and vagal stimulation + TBI equalized relatively and were 2.9 and 3.1-fold higher than sham alone.

Figure 4.

Quantitative PCR was performed on intestinal extracts obtained at several time points after procedure. Relative expression of intestinal GFAP mRNA is shown as fold increase over sham animals. TBI increased intestinal GFAP 6.2-fold higher than sham at 2 hours and 11.5-fold higher at 4 hours after injury. In vagal stimulation + TBI animals, intestinal GFAP was 6.7-fold higher than sham at 2 hours and was 18.0-fold at 4 hours after injury compared with sham. At 6 hours after injury, TBI and vagal stimulation + TBI equalized and were 2.9 and 3.1-fold higher than sham alone.

DISCUSSION

The physiologic consequences after TBI are variable and unique especially given the surge in adrenergic tone and pro-inflammatory cytokines.13,14 These acute changes may contribute to the systemic alterations involving specific organ systems most notably the cardiopulmonary system and the gastrointestinal tract.3 We have previously described a nearly threefold increase in intestinal permeability after TBI that, at least in part, is instigated by a decrease in cell to cell integrity manifested by attenuation of specific tight junction proteins 5. Preventing TBI-related intestinal dysfunction may ultimately decrease infectious complications, such as pneumonia, however, the severity of intestinal dysfunction needed that lead to these complications is unknown.15 The mechanism causing post-TBI related intestinal dysfunction is likely multifactorial and probably include an unchecked inflammatory cytokine milieu, altered intestinal cellular architecture, epithelial cell apoptosis, and changes in tight junction integrity. In a recent article, Costantini et al.12 showed that pentoxifyline, a known anti-inflammatory agent, significantly decreased TNF-α levels and prevented an increase in intestinal permeability after a severe burn model. Therefore, other approaches that may decrease intestinal TNF-α levels may have a similar effect.

In this study, we have shown that vagal stimulation before TBI prevented an increase in intestinal permeability, preserved intestinal architecture and decreased intestinal TNF-α after TBI. Zolotarevsky et al.16 have shown that intestinal epithelial cells, treated with TNF-α, have increased permeability that likely involves phosphorylation of myosin light chain kinase causing enterocyte cytoskeleton changes. Therefore, we hypothesized that preventing the surge of intestinal TNF-α after TBI would also result in decreased intestinal permeability. It is now well accepted that signaling from the vagus nerve has potent anti-inflammatory effects.17 Tracey has shown, in a murine model, that vagal stimulation before endotoxin injection significantly decreases serum TNF-α and improves animal survival.18 Current evidence suggests that vagal stimulation increases levels of synaptic acytelcholine specifically at the α-7 muscuranic receptor of immune cells (i.e. macrophages), which consequently decreases the release of TNF-α.19 In contrast, vagotomized animals exhibited elevated levels of TNF-α with aggravation of lethal shock. Similarly, we have shown that vagal stimulation resulted in a nearly twofold decrease of TNF-α after TBI and a subsequent decrease in intestinal permeability and intestinal injury. Whether this decrease is a result of a blunted release of TNF-α from resident intestinal immune cells will need to be further investigated. It is also plausible that intestinal injury, and the observed increase in TNF-α, is mediated by post-TBI vasoconstriction and consequent tissue ischemia. It is unknown what effect vagal stimulation has on the vascular tone of specific tissue beds after TBI. Future experiments investigating the effects of TBI and vagal stimulation on tissue perfusion would address these questions. Even though our studies are preliminary, to our knowledge, electrically stimulating the vagus nerve to prevent intestinal injury after TBI has not been previously reported.

Intestinal dysfunction after TBI is yet another pathway in the developing paradigm of the neuroenteric axis. In this paradigm, communication between the brain and the gut (or vice versa) is modulated mostly through vagus nerve and enteric glia synaptic connections. Ammori et al.20 have recently reported a decrease in neuron proliferation of the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus (DMNV) from adult rats with chemically induced colitis compared with normal adult rat intestine, suggesting that intestinal inflammation adversely affects neuronal survival and function in the DMNV. If the brain, and specifically the DMNV, is responsible for maintaining intestinal homeostasis, TBI-induced intestinal dysfunction may be a result of dysregulation of the neuroenteric axis. In our study, we have assessed the affect of TBI and vagal stimulation + TBI on the enteric nervous system by measuring the relative increase of GFAP. Enteric glial cells are activated in response to injury and inflammation, resulting in increased expression of the glial marker GFAP. GFAP expression is a surrogate for glial cell activation indicative of increased central nervous system activity. The greater than 1.6-fold increase of enteric GFAP that vagal stimulation + TBI caused compared with TBI alone may be indicative of heightened enteric glial expression preventing TBI-induced intestinal changes. In an experiment by Bush et al.,21 transgenic mice, undergoing ablation of enteric glial cell activity and reduced levels of GFAP demonstrated fulminate jejunalileitis. Hence, these findings demonstrate the importance of an enteric glia link in maintaining bowel integrity and, furthermore, loss of enteric glia may contribute to bowel injury and inflammation.

Our experiments support the concept that vagal stimulation prevents intestinal injury after TBI. Whether these experiments can be applicable to a clinical setting has yet to be determined. However, current therapeutic modalities in managing severe and moderate TBI may affect central nervous system tone specifically by altering the parasympathetic and sympathetic balance. Decreasing adrenergic tone through beta-blockade has been hypothesized as a mechanism to improve outcome after TBI.14 A recent, retrospective study has shown that exposure to beta blockade during hospitalization for TBI decreases the risk of mortality despite the fact that patients were older, had higher injury severity scores and had greater co-morbidities.22 Vagal stimulation has other physiologic effects, most notably on the cardiopulmonary system causing transient bradycardia and possibly hypotension.17 Our experiments stimulate the vagus nerve for only 10 minutes, therefore it would be interesting to see what effects this short stimulation period would have on post-TBI blood pressure, heart rate, and adrenergic tone.

Finally, early enteral nutrition has been shown to decrease infectious complications and improve outcomes in severe TBI patients.23,24 The benefits of early feeding are multiple; enhancing immune cell activity and gut barrier integrity, which likely prevents immune dysfunction and bacterial translocation, respectively.23 The nervous system and endocrine alterations after enteral feeding may help attenuate massive inflammation through a vagus nerve mediated mechanism. Luyer et al.25 has shown that enteral feeding, specifically dietary fats, stimulates the release of cholecystokinin (CCK) and binding to CCK receptors eventually leading to activation of the efferent vagal system. This activation triggers an increase of acetylcholine at the intestinal synaptic level and decreases TNF-α production by way of acetylcholine binding to α-7 nicotinic receptors on macrophages and other immune cells. Therefore, the positive immunologic benefits of early enteral feeding after TBI may also be a result of decreased inflammatory cytokine production by way of intraluminal feeds inducing vagus nerve activity. Whether vagus nerve stimulation alone could ever be used to improve patient outcome after TBI is unknown and further studies clearly focusing on other systemic effects of vagus nerve stimulation need to be conducted.

CONCLUSIONS

In a mouse model of TBI, our preliminary results show vagal nerve stimulation prevented TBI-induced intestinal permeability, prevented intestinal injury, and significantly reduced intestinal TNF-α. Vagal nerve stimulation also increased enteric glial activity as measured by an increase of enteric GFAP and may represent a pathway for central nervous system regulation of intestinal barrier dysfunction.

Footnotes

Presented at the 68th Annual Meeting of the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma, October 1–3, 2009, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

References

- 1.McGarry LJ, Thompson D, Millham FH, et al. Outcomes and costs of acute treatment of traumatic brain injury. J Trauma. 2002;53:1152–1159. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200212000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beal AL, Cerra FB. Multiple organ failure syndrome in the 1990s. Systemic inflammatory response and organ dysfunction. JAMA. 1994;271:226–233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kemp CD, Johnson JC, Riordan WP, Cotton BA. How we die: the impact of nonneurologic organ dysfunction after severe traumatic brain injury. Am Surg. 2008;74:866–872. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feighery L, Smyth A, Keely S, et al. Increased intestinal permeability in rats subjected to traumatic frontal lobe percussion brain injury. J Trauma. 2008;64:131–137. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181568d9f. discussion 137–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bansal V, Costantini T, Kroll L, et al. Traumatic brain injury and intestinal dysfunction: uncovering the neuroenteric axis. J Neurotrauma. 2009 Apr 6; doi: 10.1089/neu.2008.0858. [Epub ahead of print.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hang CH, Shi JX, Li JS, Li WQ, Wu W. Expressions of intestinal NF-kappaB, TNF-alpha, and IL-6 following traumatic brain injury in rats. J Surg Res. 2005;123:188–193. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2004.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hang CH, Shi JX, Sun BW, Li JS. Apoptosis and functional changes of dipeptide transporter (PepT1) in the rat small intestine after traumatic brain injury. J Surg Res. 2007;137:53–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2006.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berthoud HR, Blackshaw LA, Brookes SJ, Grundy D. Neuroanatomy of extrinsic afferents supplying the gastrointestinal tract. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2004;16(Suppl 1):28–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-3150.2004.00471.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ma B, von Wasielewski R, Lindenmaier W, Dittmar KE. Immmunohistochemical study of the blood and lymphatic vasculature and the innervation of mouse gut and gut-associated lymphoid tissue. Anat Histol Embryol. 2007;36:62–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0264.2006.00741.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stahel PF, Shohami E, Younis FM, et al. Experimental closed head injury: analysis of neurological outcome, blood-brain barrier dysfunction, intracranial neutrophil infiltration, and neuronal cell death in mice deficient in genes for pro-inflammatory cytokines. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2000;20:369–380. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200002000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cuzzocrea S, Chatterjee PK, Mazzon E, et al. Role of induced nitric oxide in the initiation of the inflammatory response after postischemic injury. Shock. 2002;18:169–176. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200208000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Costantini TW, Loomis WH, Putnam JG, et al. Burn-induced gut barrier injury is attenuated by phosphodiesterase inhibition: effects on tight junction structural proteins. Shock. 2009;31:416–422. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3181863080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vitarbo EA, Chatzipanteli K, Kinoshita K, Truettner JS, Alonso OF, Dietrich WD. Tumor necrosis factor alpha expression and protein levels after fluid percussion injury in rats: the effect of injury severity and brain temperature. Neurosurgery. 2004;55:416–424. doi: 10.1227/01.neu.0000130036.52521.2c. discussion 424–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baguley IJ, Heriseanu RE, Cameron ID, Nott MT, Slewa-Younan S. A critical review of the pathophysiology of dysautonomia following traumatic brain injury. Neurocrit Care. 2008;8:293–300. doi: 10.1007/s12028-007-9021-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Woiciechowsky C, Schoning B, Cobanov J, Lanksch WR, Volk HD, Döcke WD. Early IL-6 plasma concentrations correlate with severity of brain injury and pneumonia in brain-injured patients. J Trauma. 2002;52:339–345. doi: 10.1097/00005373-200202000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zolotarevsky Y, Hecht G, Koutsouris A, et al. A membrane-permeant peptide that inhibits MLC kinase restores barrier function in in vitro models of intestinal disease. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:163–172. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.34235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tracey KJ. The inflammatory reflex. Nature. 2002;420:853–859. doi: 10.1038/nature01321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Borovikova LV, Ivanova S, Zhang M, et al. Vagus nerve stimulation attenuates the systemic inflammatory response to endotoxin. Nature. 2000;405:458–462. doi: 10.1038/35013070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang H, Yu M, Ochani M, et al. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor alpha7 subunit is an essential regulator of inflammation. Nature. 2003;421:384–388. doi: 10.1038/nature01339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ammori JB, Zhang WZ, Li JY, Chai BX, Mulholland MW. Effects of ghrelin on neuronal survival in cells derived from dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus. Surgery. 2008;144:159–167. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2008.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bush TG, Savidge TC, Freeman TC, et al. Fulminant jejunoileitis following ablation of enteric glia in adult transgenic mice. Cell. 1998;93:189–201. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81571-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cotton BA, Snodgrass KB, Fleming SB, et al. Beta-blocker exposure is associated with improved survival after severe traumatic brain injury. J Trauma. 2007;62:26–33. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31802d02d0. discussion 33–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Todd SR, Gonzalez EA, Turner K, Kozar RA. Update on postinjury nutrition. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2008;14:690–695. doi: 10.1097/MCC.0b013e3283196562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Taylor SJ, Fettes SB, Jewkes C, Nelson RJ. Prospective, randomized, controlled trial to determine the effect of early enhanced enteral nutrition on clinical outcome in mechanically ventilated patients suffering head injury. Crit Care Med. 1999;27:2525–2531. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199911000-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Luyer MD, Greve JW, Hadfoune M, Jacobs JA, Dejong CH, Buurman WA. Nutritional stimulation of cholecystokinin receptors inhibits inflammation via the vagus nerve. J Exp Med. 2005;202:1023–1029. doi: 10.1084/jem.20042397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]