Abstract

Background

Burn injury can result in loss of intestinal barrier function, leading to systemic inflammatory response syndrome and multiorgan failure. Myosin light chain kinase (MLCK), a tight junction protein involved in the regulation of barrier function, increases intestinal epithelial permeability when activated. Prior studies have shown that tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α activates MLCK, in part through a nuclear factor (NF)-κ B-dependent pathway. We have previously shown that pentoxifylline (PTX) decreases both TNF-α synthesis and NF-κB activation in models of shock. Therefore, we postulate that PTX will attenuate activation of the tight junction protein MLCK, which may decrease intestinal tight junction permeability after severe burn.

Methods

Male balb/c mice undergoing a severe burn were randomized to resuscitation with normal saline (NS) or NS + PTX (12.5 mg/kg). Intestinal TNF-α levels were evaluated using enzyme linked immunosorbent assay. Gut extracts were obtained to assess MLCK, phosphorylated IKK, IκB-α, and NF-κB p65 levels by immunoblotting.

Results

Burn injury increased intestinal MLCK protein levels threefold in animals resuscitated with NS, whereas those receiving PTX had MLCK levels similar to control (p < 0.01). Treatment with PTX attenuated burn-induced intestinal permeability. PTX decreased cytoplasmic IKK, IκB-α phosphorylation, and nuclear NF-κB p65 translocation to sham levels (p < 0.05 vs. NS).

Conclusion

Treatment with PTX attenuates activation of the tight junction protein MLCK, likely through its ability to decrease local TNF-α synthesis and NF-κB activation after burn. PTX may have therapeutic utility by decreasing intestinal barrier breakdown after burn.

Keywords: Phosphodiesterase inhibition, Pentoxifylline, Burn, Myosin light chain kinase, TNF-α, Nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB), Tight junction, Intestinal permeability

The intestinal tight junction regulates intestinal epithelial barrier function, and can be modulated by proinflammatory cytokines which are generated following severe burn, hemorrhagic shock, and sepsis. An intact intestinal barrier is essential to protect the gut from the potential damaging luminal contents. Increased epithelial barrier permeability can allow the harmful luminal contents to access normally protected layers of the intestinal wall. This can lead to intestinal inflammation and may result in a systemic inflammatory response (SIRS) because of the circulation of gut-derived inflammatory cytokines, ultimately leading to distant organ injury.1 Therefore, therapies directed at limiting intestinal barrier breakdown may attenuate the SIRS response after burn and may decrease morbidity and mortality.

The intestinal epithelial barrier is a highly regulated structure requiring the coordination of several key tight junction proteins to maintain an intact barrier. Actin filaments are found encircling the intestinal epithelial cell at the level of the tight junction. The perijunctional actin ring associates with the tight junction protein occludin and zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1) to maintain a barrier between adjacent cells. These actin filaments appear to be key regulators of the intestinal tight junction. Studies have documented that contraction of the actin-myosin ring can lead to tight junction disruption.2 Myosin light chain kinase (MLCK) regulates contraction of the perijunctional actin ring by causing phosphorylation of myosin II regulatory light chain (MLC). Activation of MLCK is sufficient to induce increased tight junction permeability and also cause the breakdown of the tight junction structural proteins occludin and ZO-1.3 Interestingly, the nuclear factor (NF)-κB signaling pathway has been shown to mediate increases in MLCK expression in response to proinflammatory stimuli, resulting in barrier breakdown.4

Pentoxifylline (1-{5-oxohexyl}-3,7-dimethylxanthine, PTX) is a nonspecific phosphodiesterase inhibitor know to increase intracellular levels of cyclic AMP (cAMP).5 Our laboratory has extensively studied PTX as an immunomodulatory adjunct to resuscitation fluid in various models of shock. We have previously shown that treatment with PTX decreases intestinal permeability and breakdown of the tight junction proteins occludin and ZO-1 in a murine model of severe burn.6 PTX has also been shown to inhibit proinflammatory cytokine synthesis and attenuate signaling via the NF-κB pathway in a small animal model of hemorrhagic shock.7,8

In this study, we investigate the effects of PTX on MLCK activation after severe cutaneous burn. We postulate that burn injury will increase intestinal MLCK and phosphorylated MLC. We also hypothesize that treatment with PTX immediately after burn will attenuate MLCK activation, MLC phosphorylation, and will decrease signaling through the NF-κB pathway.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental Model

Male balb/c mice (20–24 g) were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Sacramento, CA). Animals were anesthetized using inhaled isoflurane. A large area of the dorsal fur was removed using a clipper. A template was made to estimate a 30% total body surface area (TBSA) based on the Walker-Mason burn model.9 Animals were then placed in the template and subjected to a 7-second steam burn. After burn, animals were randomized to receive an intraperitoneal injection of PTX (12.5 mg/kg, Sigma, St. Louis, MO) dissolved in 500 μL normal saline (NS), or NS alone. All animals received a subcutaneous injection of 1.5 mL of NS with buprenorphine in a nonburned area. Sham animals underwent induction of general anesthesia, dorsal fur clipping, intraperitoneal injection of NS, and subcutaneous injection of buprenorphine in NS but were not subjected to burn. After the experiment, animals were returned to their cages and allowed to recover from anesthesia. They were provided food and water ad libitum.

These experiments were approved by the University of California Animal Subjects Committee and are in accordance with guidelines established by the National Institutes for Health.

Tissue Procurement

At 2 hours after burn, animals were anesthetized with isoflurane. After killing, the distal ileum was immediately harvested through a midline laparotomy and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen. Tissue specimens were stored at −70°C for later analysis. Samples of ileum were also preserved in both formalin and optimal cutting technique (OCT) embedding media (Sakura Finetek, Torrance, CA) for later histologic analysis.

Intestinal Protein Extraction

The distal ileum was homogenized in 500 μL of ice cold tissue protein extraction reagent (T-PER) containing 1% protease inhibitor and 1% phosphatase inhibitor (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL). Homogenates were centrifuged at 10,000g for 5 minutes. The supernatant was obtained and stored at −70°C until used for further studies.

The NE-PER Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction Reagent kit (Pierce) was used to analyze changes in cytoplasmic IKK and IκB-α, and nuclear NF-κB p65. Once obtained, the nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts were placed into Eppendorf tubes and stored at −70°C until used for Western blot analysis.

Histopathologic Evaluation

Segments of distal ileum (n ≥ 3 per group) were stored in 10% phosphate buffered saline (PBS) buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin blocks using an automated processor. Sections were cut 7 μm thick, placed onto glass slides, and stained with hematoxylineosin (H&E, Richard Allen Scientific). Images were obtained using an Olympus IX70 light microscope at 20× magnification with Q-imaging software.

Intestinal Permeability Assay

Four hours after burn, animals from each experimental group (n ≥ 3 per group) were once again placed under general anesthesia with isoflurane. A midline laparotomy was performed and the distal ileum exposed. A 5-cm segment of distal ileum was isolated between silk ties. A solution containing 25 mg of 4 kDa FITC-Dextran diluted in 200 μL PBS was injected into the intestinal lumen. The bowel was then returned to the abdominal cavity and the underlying skin was closed. The animal was maintained under general anesthesia. At 30 minutes after injection of FITC-Dextran, blood was drawn via cardiac puncture. Blood was placed in heparinized tubes on ice and centrifuged at 10,000g for 10 minutes. The plasma was then analyzed for the concentration of FITC-Dextran using a SpectraMax M5 fluorescence spectrophotometer (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). A standard curve was obtained by diluting serial concentrations of FITC-dextran in mouse serum.

Intestinal Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF)-α Levels

Intestinal TNF-α levels were measured in intestinal extracts 2 hours after burn injury (n ≥ 3 per group) using a commercially available sandwich enzyme immunoassay technique (ELISA, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). TNF-α levels were measured in pg/mL.

Immunoblotting

The protein concentration of each sample was determined using the bicinchoninic acid protein assay (Pierce) using a microplate reader protocol. Samples (n ≥ 3 per group) containing 15 μg of protein were suspended in sodium dodecyl sulfate sample buffer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and boiled at 100°C for 5 minutes. Proteins were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis using 8% to 16% trisglycine polyacrylamide gradient gels and subsequently transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Invitrogen). The membranes were blocked with 5% BSA in trisbuffered saline/Tween 20 for 1 hour. Primary antibodies specific for MLCK (1:250, Sigma), phosphorylated NF-κB p65 (1:500, cell signaling), IKK α/β (1:500 cell signaling), phosphorylated IKK α/ β (1:500 cell signaling), IκB-α (1: 500, cell signaling), phosphorylated IκB-α (1:500, cell signaling), or β-actin (1:500, cell signaling) were incubated with the membranes overnight at 4°C in 5% BSA with trisbuffered saline/Tween 20. Membranes were washed and incubated for 1 hour at room temperature with the secondary antibody (1:2,000, cell signaling) prepared in blocking solution. After thorough washing, the Pierce Supersignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Kit was applied for antibody detection with X-ray film (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ). Mean pixel density was estimated using UN-SCAN-IT Gel Digitizing software (Silk Scientific, Orem, UT). Data are expressed as relative pixel density for each experimental group after obtaining the mean pixel density for each group and dividing it by the mean pixel density of sham animals.

Immunohistochemical Evaluation of Myosin Light Chain Phosphorylation

Samples of distal ileum from each experimental group (n ≥ 3 per group) were fixed in OCT and stored at −70°C. Ten micrometer sections were sectioned using the Reichert-Jung Cryocut 1800 (Reichert Microscopes, Depew, NY). Sections of ileum were fixed onto glass slides with 3.7% paraformaldehyde (Electron Microscopy Series, Hatfield, PA) for 10 minutes. Glass slides were washed with PBS, then the intestinal cells were permeabilized with 0.01% Triton X-100 (Sigma) in PBS for 1 minute. After washing with PBS, sections were blocked for 1 hour using 3% BSA. Sections were incubated overnight with the primary antibody, phosphorylated myosin light chain (1:100, cell signaling) in 1% BSA. After washing with PBS, the sections were treated with the secondary antibody, Alexa Fluor 488 (1:100, invitrogen) or rhodamine phalloidin (1:100, invitrogen), in 1% BSA for 1 hour. Cover slips were placed onto glass slides after the addition of prolong fade (invitrogen). Glass slides were cured overnight in the dark. Images were viewed using an Olympus Fluoroview laser scanning confocal microscope (Olympus, Melville, NY) using exposure matched settings (Advanced Software V1.6, Olympus, Center Valley, PA) at 60× magnification with a 2.3× zoom.

Statistical Analysis

Values are expressed as the mean ± standard error mean (SEM) of n observations, where n represents the number of animals in each experimental group. Each assay was performed in duplicate where appropriate. The statistical significance among groups was determined using analysis of variance with Bonferonni correction. A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Histopathologic Evaluation

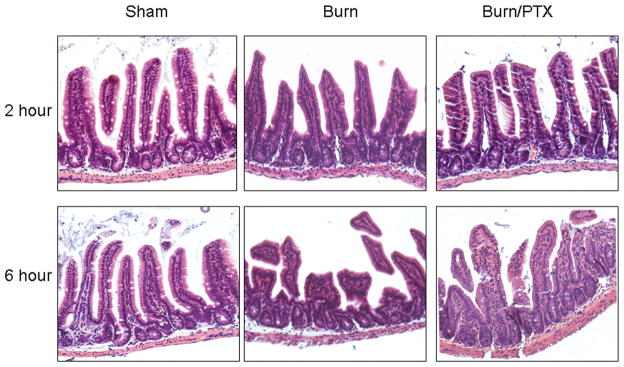

Sections of distal ileum from each experimental group were assessed for evidence of histologic injury at 2 and 6 hours after burn (Fig. 1). There was no evidence of histologic gut injury in the burn or the burn/PTX groups at 2 hours. The histologic appearance of the intestine of burned animals demonstrated marked blunting of the villi at 6 hours after burn. Burned animals treated with PTX had an appearance similar to sham, with minimal changes to the villi. These findings suggest that burn-induced alterations in intracellular signaling at 2 hours precede changes in gut architecture, which do not appear until 6 hours after burn.

Fig. 1.

Histologic appearance of the distal ileum at 2 and 6 hours after 30% TBSA burn. Sections of distal ileum stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and viewed at 20× magnification using a light microscope. There is no evidence of histologic gut injury at 2 hours after burn. Histologic injury is noted in animals 6 hours after burn, characterized by blunting of the villi and necrosis. Treatment with PTX attenuates these burn-induced histologic changes at 6 hours.

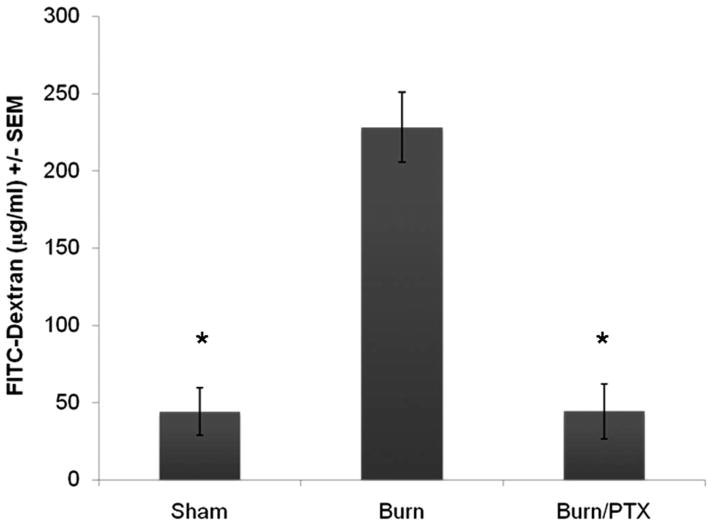

Intestinal Permeability Assay

We used a classic intestinal permeability assay to measure the movement of small molecules across the intestinal epithelium, into the systemic circulation 4 hours after burn (Fig. 2). We chose this intermediate time point to compare our results with a previously published intestinal permeability assay performed after 30% TBSA burn.10 Four hours after severe burn there was a significant increase in 4 kDa FITC-Dextran measured in the systemic circulation after intraluminal injection into a loop of distal ileum (228 μg/mL ± 23 μg/mL vs. 44 μg/mL ± 15 μg/mL, p < 0.01). Treatment with PTX immediately after burn prevented intestinal permeability (44 μg/mL ± 18 μg/mL, p < 0.01 vs. burn).

Fig. 2.

Effects of severe full thickness burn on intestinal permeability. The systemic concentration of 4 kDa FITC-Dextran was measured after intraluminal injection 4 hours after burn (n ≥ 3 animals per group). Severe burn resulted in a significant increase in intestinal permeability to 4 kDa FITC-Dextran compared with sham (228 μg/mL ± 23 μg/mL vs. 44 μg/mL ± 15 μg/mL). In animals treated with PTX, intestinal permeability decreased to sham levels (44 μg/mL ± 18 μg/mL). *p < 0.01 versus burn.

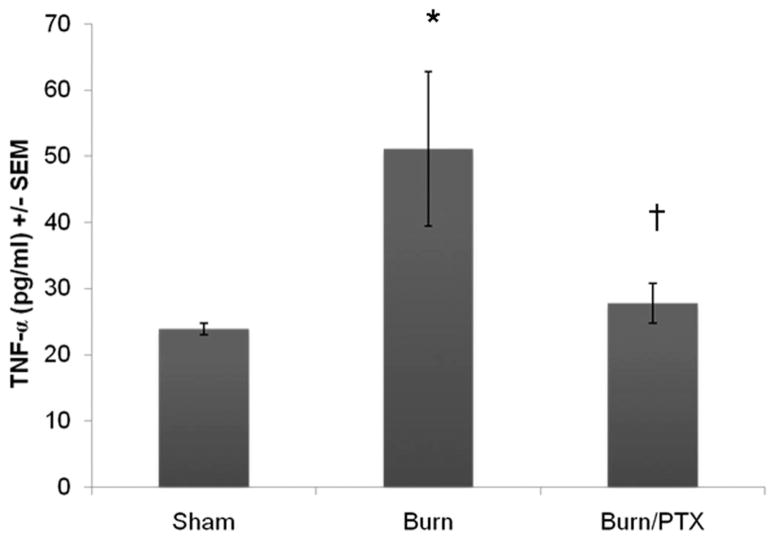

Intestinal TNF-α Levels

TNF-α is known to induce increases in intestinal tight junction permeability.11 Therefore, we measured intestinal TNF-α levels 2 hours after burn (Fig. 3). Severe burn resulted in a significant increase in intestinal TNF-α (51 pg/mL ± 11 pg/mL vs. 24 pg/mL ± 1 pg/mL, p < 0.01). Animals given PTX had intestinal TNF-α levels that were unchanged compared with sham (28 pg/mL ± 3 pg/mL, p < 0.05 vs. burn).

Fig. 3.

Intestinal TNF-α after severe burn injury. Quantification of TNF-α from intestinal extracts 2 hours after burn using enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (n ≥ 3 animals per group). Thirty percent TBSA full thickness burn resulted in a significant increase in intestinal TNF-α (51 pg/mL ± 11 pg/mL). Intraperitoneal injection of PTX immediately after burn attenuated the burn-induced increase in TNF-α. *p < 0.01 versus sham. †p < 0.05 versus burn.

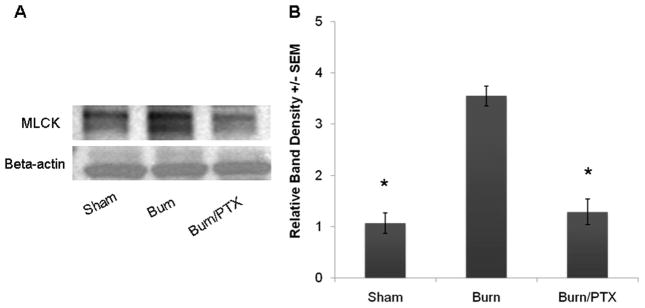

Intestinal MLCK Protein

Changes in MLCK protein expression have been shown to regulate tight junction barrier function in response to cytokines and other proinflammatory stimuli.12 Therefore, we performed Western blot analysis of intestinal extracts after 30% TBSA burn injury to investigate changes in MLCK protein expression (Fig. 4). There was a significant increase in MLCK expression 2 hours after severe burn (3.6 ± 0.2-fold increase vs. sham, p < 0.01). Phosphodiesterase inhibition with PTX prevented the burn-induced increase in MLCK. There was no significant difference between sham and burned animals treated with PTX.

Fig. 4.

Changes in intestinal myosin light chain kinase (MLCK) expression after 30% TBSA burn. (A) Representative Western blots for MLCK protein expression 2 hours after burn. β-Actin was used as a loading control. (B) Severe burn resulted in a greater than threefold increase in MLCK expression compared with sham. Treatment with 12.5 mg/kg PTX attenuated the burn-induced increase in MLCK (n ≥ 3 animals per group). *p <0.01 versus burn.

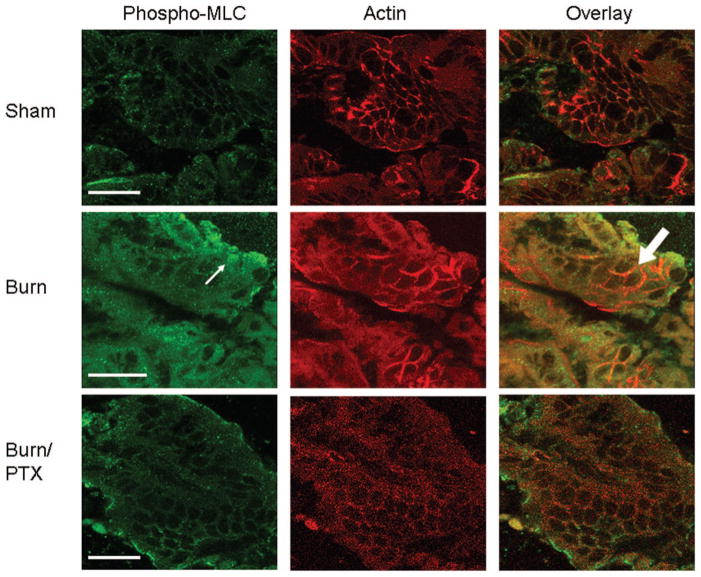

Immunohistochemical Staining for Phosphorylated Myosin Light Chain

Increased MLCK activity results in increased phosphorylation of myosin light chain (MLC), and has been shown to regulate barrier function.13 To confirm our results indicating increased activation of MLCK, we evaluated changes in distribution of phosphorylated myosin light chain using exposure-matched confocal microscopy images (Fig. 5). There was increased staining for phosphorylated MLC in burned animals compared with sham. The images show the colocalization of phosphorylated MLC with actin at the periphery of the intestinal epithelial cell. There was a decreased amount of staining seen in burned animals treated with PTX, which correlates with the changes in MLCK protein seen by Western blot.

Fig. 5.

Immunohistochemical staining of intestinal sections for phosphorylated myosin light chain (MLC) and actin after burn. These are exposure-matched confocal microscopy images from sections of distal ileum that were obtained 2 hours after 30% TBSA burn. Sections were stained for phosphorylated MLC (left column) and rhodamine phalloidin which stains for actin (middle column). An overlay of phosphorylated MLC and actin staining is shown to demonstrate colocalization (right column). Increased staining for phosphorylated MLC is seen in burn animals (arrow). There is colocalization of phosphorylated MLC with the actin cytoskeleton at the periphery of the intestinal epithelial cells after burn (block arrow). In burned animals treated with PTX, there is a decrease in staining for phosphorylated MLC. Bar = 20 μm.

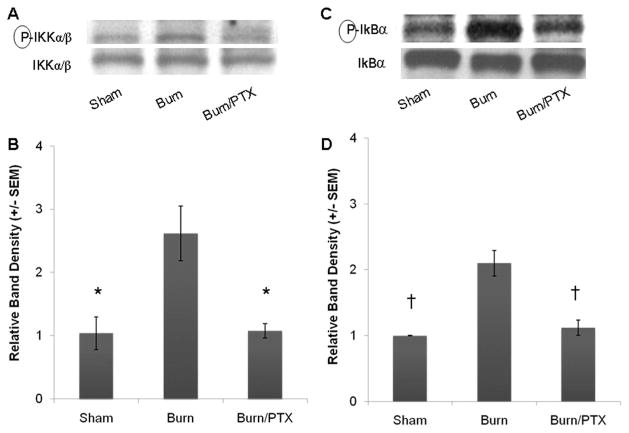

Phosphorylation of Cytoplasmic IKK and IκB-α

In its inactive state, NF-κB p65 is sequestered in the cytoplasm bound to its inhibitor, IκB-α. Proinflammatory stimulation results in phosphorylation of IKK. Once activated, IKK phosphorylates IκB-α resulting in the ubiquitination and degradation of this inhibitory subunit. Cytoplasmic extracts from intestinal cells were obtained to evaluate for changes in the phosphorylation of IKK and IκB-α after burn (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Changes in cytoplasmic IKK and IκB-α phosphorylation from intestinal extracts 2 hours after severe burn (n ≥ 3 animals per group). (A) Representative Western blots for phosphorylated and total IKK using cytoplasmic extracts from intestinal specimens. (B) Severe burn resulted in nearly a threefold increase in phosphorylation of IKK, which was attenuated in animals treated with PTX. (C) Western blots for phosphorylated and total IκB-α from the cytoplasmic fraction of intestinal extracts. (D) Burn injury caused a twofold increase in the activation of IκB-α. Treatment with PTX (12.5 mg/kg), returned intestinal phosphorylated IκB-α to sham levels. *p < 0.05 versus burn. †p < 0.02 versus burn.

Treatment with PTX prevented the burn-induced increase in phosphorylation of IKK. Burn injury resulted in a 3.4 ± 0.6-fold increase over sham at 2 hours ( p < 0.05). Treatment with PTX resulted in a significant decrease in IKK phosphorylation ( p < 0.05 vs. burn). There was no significant difference between sham and burned animals treated with PTX.

Similar results were seen when phosphorylation of cytoplasmic IκB-α was analyzed. There was a greater than twofold increase in phosphorylated IκB-α in burned animals compared with sham (p < 0.02). PTX treated animals had phosphorylated IκB-α levels similar to sham.

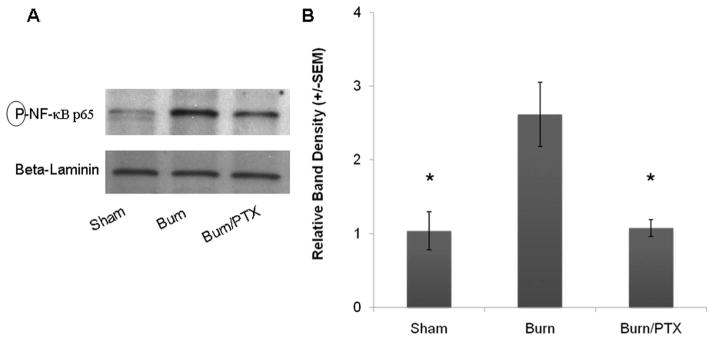

Nuclear Phosphorylated NF-κB p65

Once activated, NF-κB p65 is freed from its inhibitory subunit and able to translocate into the nucleus where it binds transcriptional promoters. Intestinal nuclear extracts were obtained 2 hours after severe burn, and analyzed for NF-κB p65 translocation (Fig. 7). Burn injury resulted in a 2.6 ± 0.4-fold increase in nuclear phosphorylated NF-κB p65 compared with sham ( p < 0.03). Treatment with PTX immediately after burn significantly decreased nuclear phosphorylated NF-κB p65 (1.1 ± 0.1-fold increase over sham) compared with burn alone ( p < 0.03). There was no difference seen between sham animals and burned animals treated with PTX.

Fig. 7.

Effects of full thickness burn injury on NF-κB nuclear translocation in intestinal epithelial cells. NF-κB measured from the nuclear fraction of intestinal extracts 2 hours after 30% TBSA burn (n ≥ 3 animals per group). (A) Western blot for nuclear phosphorylated NF-κB p65. Nuclear β-laminin was used as a loading control. (B) Severe burn results in a 2.6-fold increase in nuclear phosphorylated NF-κB. Injection of PTX (12.5 mg/kg IP) immediately after burn prevents the burn-induced nuclear translocation of NF-κB. *p < 0.03 versus burn.

DISCUSSION

Intestinal epithelial barrier breakdown plays a key role in the SIRS response after shock. Intestinal permeability has been shown to increase in response to proinflammatory stimuli, which are known to exist after severe burn or hemorrhagic shock, and can result in a significant host response because of the potentially cytotoxic contents contained in the intestinal lumen. Research indicates that the inflammatory cascade initiated in the gut may potentiate systemic inflammation and result in distant organ injury.14 Regulation of the intestinal tight junction, the key determinant of intestinal permeability, may serve as an important target for therapy.

MLCK is an important regulator of intestinal barrier function because of its ability to modulate the actin-myosin ring. Actin filaments are associated with tight junction proteins in intestinal epithelial cells, and disruption of the actin filaments is known to induce tight junction disruption.15 MLCK has been studied extensively in relation to inflammatory bowel disease, because MLCK is activated by proinflammatory cytokines. TNF-α is known to activate MLCK, which results in phosphorylation of MLC, and subsequent increases in permeability across the intestinal barrier.16 MLCK clearly plays a central role in the regulation of the tight junction. Activation of MLCK has not only been shown to cause an increase in permeability, but also results in modulation of the other key tight junction proteins, occludin and ZO-1.3 Here, we show for the first time that intestinal MLCK increases in response to severe burn. Insights into the regulation of MLCK may be important in developing strategies to modulate barrier breakdown in shock.

The NF-κB signaling cascade is a common pathway involved in the inflammatory response to diverse stimuli. Phosphorylation of the IKK complex results in phosphorylation of IκB-α, the cytoplasmic inhibitor of the NF-κB p65 subunit. Once phosphorylated, IκB-α is rapidly ubiquitinated and degraded, freeing NF-κB p65 to translocate to the nucleus to bind to its transcriptional promoter. This results in propagation of the inflammatory response through the production of proinflammatory cytokines and activation of other inflammatory cells. In this series of experiments, we showed that 30% TBSA full thickness burn results in increased phosphorylation of the cytoplasmic regulators IKK and IκB-α, resulting in increased levels of phosphorylated nuclear NF-κB p65. The TNF-α-induced increase in MLCK activity is mediated by NF-κB activation. In fact, an NF-κB binding site has been identified upstream of the MLCK promoter region, indicating that NF-κB can regulate MLCK transcription.17 Ye et al.4 have shown that MLCK activity is mediated by binding of phosphorylated NF-κB p65 to a downstream binding site on the MLCK promoter. To confirm this, they revealed that deletion of the NF-κB binding site on the MLCK promoter prevented the increase in MLCK activation caused by TNF-α, and prevented increases in permeability.

Inhibition of MLCK activity may be an ideal method of limiting intestinal barrier breakdown, and decreasing the SIRS response after severe trauma or burn. Previous studies have demonstrated that inhibition of MLCK results in decreased phosphorylation of MLC, and a decrease in the TNF-α induced increases in barrier permeability.18,19 Here, we demonstrated that treatment with PTX immediately after burn prevented the increased MLCK expression seen after severe full thickness burn. This was confirmed with immunohistochemistry of intestinal epithelial cells showing a decrease in phosphorylated MLC.

PTX has previously been used extensively in the treatment of intermittent claudication. PTX has also generated interest because of its anti-inflammatory properties, and has clinically been shown to decrease liver inflammation in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis.20 A recent prospective, randomized study in cardiac surgery patients demonstrated that PTX decreased circulating TNF-α, and improved hospital and Intensive Care Unit length of stay.21 We have demonstrated the use of PTX as an immunomodulator after various forms of shock. Data from animal models of hemorrhagic shock and sepsis has shown that PTX decreases proinflammatory cytokine synthesis and decreases end organ injury.22,23 PTX has also been shown to decrease intestinal bacterial translocation in an animal model of intestinal obstruction.24,25

PTX may limit MLCK activation after severe burn because of its ability to decrease NF-κB activation. In this study, we found that treatment with PTX decreases phosphorylation and activation of cytoplasmic IKK and IκB-α. Importantly, this resulted in a decrease in nuclear translocation of NF-κB p65. PTX is known to increase intracellular levels of cAMP, and exerts its effects through both protein kinase A-dependent and independent mechanisms.26 Both increases in cAMP and protein kinase A activation have been shown to inhibit signaling via the NF-κB pathway and decrease TNF-α production.27,28 This correlates with our previous findings that treatment with PTX results in decreased NF-κB activation in the liver, lung, and intestine after hemorrhagic shock.7,8,29 We have previously evaluated the effects of PTX on NF-κB signaling in human mononuclear cells, finding that PTX inhibits signaling at the level of, or upstream of, phosphorylation of IKK.30 The exact inhibitory mechanism exerted by PTX on NF-κB signaling has yet to be fully elucidated.

In this study we chose our dose of PTX (12.5 mg/kg) based on our prior experience in animal models of shock, as this dose is well tolerated and is adequate for the attenuation of inflammatory signaling. Although we did not study the effect of PTX alone on sham animals in this study, we recently documented that this group had no significant change in intestinal permeability.6 We, therefore, did not repeat those experiments in this study.

We have shown for the first time that severe burn results in increased MLCK protein expression and increased phosphorylation of MLC at 2 hours after burn, which corresponds with increased phosphorylation and nuclear translocation of NF-κB p65. Importantly, these changes resulted in increased intestinal permeability. Treatment with the nonspecific phosphodiesterase inhibitor PTX attenuated MLCK activation and decreased phosphorylated MLC, possibly through its ability to decrease NF-κB activation and TNF-α production. This modulation of postburn inflammatory signaling resulted in improved intestinal barrier function.

The use of immunomodulatory adjuncts after severe trauma or burn represent an important therapeutic strategy aimed at limiting the SIRS response. Specifically limiting intestinal barrier breakdown may be a key intervention, as the gut is thought to be central in the generation of the inflammatory response. Because of its ability to limit intestinal epithelial breakdown and intestinal inflammation, PTX may be a suitable candidate for use as an immunomodulator after severe burn injury.

Footnotes

Presented at the 67th Annual Meeting of the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma, September 24–27, 2008, Maui, Hawaii.

References

- 1.Magnotti LJ, Upperman JS, Xu DZ, Lu Q, Deitch EA. Gut-derived mesenteric lymph but not portal blood increases endothelial cell permeability and promotes lung injury after hemorrhagic shock. Ann Surg. 1998;228:518–527. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199810000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Madara JL, Moore R, Carlson S. Alteration of intestinal tight junction structure and permeability by cytoskeletal contraction. Am J Physiol. 1987;253:C854–C861. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1987.253.6.C854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shen L, Black ED, Witkowski ED, et al. Myosin light chain phosphorylation regulates barrier function by remodeling tight junction structure. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:2095–2106. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ye D, Ma I, Ma TY. Molecular mechanism of tumor necrosis factor-alpha modulation of intestinal epithelial tight junction barrier. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2006;290:496–504. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00318.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Endres S, Fulle HJ, Sinha B, et al. Cyclic nucleotides differentially regulate the synthesis of tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interleukin-1 beta by human mononuclear cells. Immunology. 1991;72:56–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Costantini TW, Loomis WH, Putnam JG, et al. Burn-induced injury is attenuated by phosphodiesterase inhibition: effects on tight junction structural proteins. Shock. 2008 doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3181863080. epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deree J, Wolf P, Loomis WH, Coimbra R. Hepatic transcription factor activation and proinflammatory mediator production is attenuated by hypertonic saline and pentoxifylline resuscitation after hemorrhagic shock. J Trauma. 2008;64:1230–1238. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31816a4391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deree J, de Campos T, Shenvi E, Loomis WH, Hoyt DB, Coimbra R. Hypertonic saline and pentoxifylline attenuates gut injury after hemorrhagic shock: the kinder, gentler resuscitation. J Trauma. 2007;62:818–828. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31802d9745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walker HL, Mason AD. A standard animal burn. J Trauma. 1968;8:1049–1051. doi: 10.1097/00005373-196811000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen LW, Wang JS, Hwang B, Chen JS, Hsu CM. Reversal of the effect of albumin on gut barrier function in burn by the inhibition of inducible isoform of nitric oxide synthase. Arch Surg. 2003;138:1219–1225. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.138.11.1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bruewer M, Luegering A, Kucharzik T, et al. Proinflammatory cytokines disrupt epithelial barrier function by apoptosis-independent mechanisms. J Immunol. 2003;171:6164–6172. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.11.6164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nusrat A, Turner JR, Madara JL. Molecular physiology and pathophysiology of tight junctions. IV. Regulation of tight junctions by extracellular stimuli: nutrients, cytokines, and immune cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2000;279:G851–G857. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2000.279.5.G851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Turner JR. Molecular basis of epithelial barrier regulation: from basic mechanisms to clinical application. Am J Pathol. 2006;169:1901–1909. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.060681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Swank GM, Deitch EA. Role of the gut in multiple organ failure: bacterial translocation and permeability changes. World J Surg. 1996;20:411–417. doi: 10.1007/s002689900065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Madara JL. Intestinal absorptive cell tight junctions are linked to cytoskeleton. Am J Physiol. 1987;253:C171–C175. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1987.253.1.C171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ma TY, Boivin MA, Ye D, Pedram A, Said HM. Mechanism of TNF-{alpha} modulation of Caco-2 intestinal epithelial tight junction barrier: role of myosin light-chain kinase protein expression. Am J Physiol. 2005;288:G422–G430. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00412.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Graham WV, Wang F, Clayburgh DR, et al. TNF induced long myosin light chain kinase transcription is regulated by differentiation dependent signaling events: Characterization of the human long myosin light chain kinase promoter. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:26205–26215. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602164200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zolotarevsky Y, Hecht G, Koutsouris A, et al. A membrane-permeant peptide that inhibits MLC kinase restores barrier function in in vitro models of intestinal disease. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:163–172. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.34235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Turner JR, Rill BK, Carlson SL, et al. Physiological regulation of epithelial tight junctions is associated with myosin light-chain phosphorylation. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:C1378–C1385. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.273.4.C1378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Satapathy SK, Sakhuja P, Malhotra V, Sharma BC, Sarin SK. Beneficial effects of pentoxifylline on hepatic steatosis, fibrosis and necroinflammation in patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:634–638. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04756.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heinze H, Rosemann C, Weber C, et al. A single prophylactic dose of pentoxifylline reduces high dependency unit time in cardiac surgery—a prospective randomized and controlled study. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2007;32:83–89. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2007.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coimbra R, Porcides R, Loomis W, et al. HSPTX protects against hemorrhagic shock resuscitation-induced tissue injury: an attractive alternative to Ringer’s lactate. J Trauma. 2006;60:41–51. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000197417.03460.0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deree J, Martins JO, Leedom A, et al. Hypertonic saline and pentoxifylline reduces hemorrhagic shock resuscitation-induced pulmonary inflammation through attenuation of neutrophil degranulation and proinflammatory mediator synthesis. J Trauma. 2007;62:104–111. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31802d96cb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kocdor MA, Kocdor H, Guay Z, Gokce O. The effects of pentoxifylline on bacterial translocation after intestinal obstruction. Shock. 2002;18:148–151. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200208000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yada-Langui MM, Coimbra R, Lancellotti C, et al. Hypertonic saline and pentoxifylline prevent lung injury and bacterial translocation after hemorrhagic shock. Shock. 2000;14:594–598. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200014060-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deree J, Melbostad H, Loomis W, Putnam JG, Coimbra R. The effects of a novel resuscitation strategy combining Pentoxifylline and hypertonic saline on neutrophil MAPK signaling. Surgery. 2007;142:276–283. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2007.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.von Bulow V, Dubben S, Engelhardt G, et al. Zinc-dependent suppression of TNF-α production is mediated by protein kinase A-induced inhibition of Raf-1, IκB kinase, and NF-κB. J Immunol. 2007;179:4180–4186. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.6.4180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Minguet S, Huber M, Rosenkranz L, Schamel WW, Reth M, Brummer Adenosine and cAMP are potent inhibitors of the NF-kappa B pathway downstream of immunoreceptors. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:31–41. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deree J, Martins JO, de Campos T, et al. Pentoxifylline attenuates lung injury and modulates transcription factor activity in hemorrhagic shock. J Surg Res. 2007;143:99–108. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2007.03.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Deree J, Martins JO, Melbostad H, Loomis WH, Coimbra R. Insights into the regulation of TNF-alpha production in human mononuclear cells: the effects of non-specific phosphodiesterase inhibition. Clinics. 2008;63:321–328. doi: 10.1590/S1807-59322008000300006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]