Abstract

Background

More information is needed about time between sexual initiation and human papillomavirus (HPV) infection and development of cervical precancer.

Methods

The objectives were to investigate the time between first sexual activity and detection of first cervical HPV infection or development of first cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN), and associated factors in women from the double-blind, multinational, 4-year PATRICIA trial. PATRICIA enroled women aged 15-25 years with no more than 6 lifetime sexual partners. Women were randomized 1:1 to the HPV-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine or to control, but only women from the control arm who began sexual intercourse during the study or within 6 months before enrolment, and had no HPV infection detected before the recorded date of their first sexual intercourse, were included in the present analysis. The time between onset of sexual activity and detection of the first cervical HPV infection or development of the first CIN lesion was analyzed using Kaplan-Meier and univariate and multivariable Cox proportional-hazards models.

Results

A total of 9337 women were enroled in the control arm of PATRICIA of whom 982 fulfilled the required inclusion criteria for analysis. A cumulative total of 28%, 44%, and 62% of the subjects had HPV infection within 12, 24, and 48 months, respectively. The overall incidence rate was 27.08 per 100 person-years. The most common oncogenic types associated with 6-month persistent infection were HPV-16 (incidence rate: 2.74 per 100 person-years), HPV-51 (2.70), HPV-52 (1.66), HPV-66 (1.14), and HPV-18 (1.09). Increased infection risk was associated with more lifetime sexual partners, being single, Chlamydia trachomatis history, and duration of hormone use. CIN1+ and CIN2+ lesions were most commonly associated with HPV-16, with an overall incidence rate of 1.87 and 1.07 per 100 person-years, respectively. Previous cervical HPV infection was most strongly associated with CIN development.

Conclusions

More than 25% of women were infected with HPV within 1 year of beginning sexual activity. Without underestimating the value of vaccination at older ages, our findings emphasize its importance before sexual initiation.

Trial registration

clinicaltrials.gov: NCT00122681.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12879-014-0551-y) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: HPV, CIN, Sexual intercourse, Time, Risk

Background

Human papillomavirus (HPV), the causal agent of cervical cancer, is believed to be the most common sexually transmitted infection worldwide, with up to 75% of sexually active people being infected during their life [1]. A persistent infection with an oncogenic HPV type is almost always required before development of cervical pre-cancer or cancer [2]-[4]. Fortunately, most HPV infections are transient and clear naturally within a few months [5]. Individual immune responses are important in determining the path of an infection, and a limited number of other non-viral determinants with modest risks for HPV infection and progression have been well established [6]-[11].

HPV vaccination programs have been introduced in many countries worldwide and are primarily targeted at adolescent girls. Vaccination before first sexual intercourse is important because HPV infection is frequently detected in sexually active adolescent girls and young women [12],[13]. HPV infection often occurs shortly after onset of sexual activity, and many girls and women acquire an infection with their first sexual relationship [13]-[16].

To add to the body of knowledge concerning the natural history of HPV, more data are needed about the time between onset of sexual activity and first acquisition of HPV infection and first development of detectable lesions under surveillance using defined referral algorithms. However, few prospective data are available [13],[15],[16]. The control arms of large trials of prophylactic HPV vaccines are well placed to inform such questions, with large samples of women with relatively diverse behavioral characteristics, and data collected on acquisition of different HPV types, development of pre-cancerous lesions, and factors potentially influencing infection and progression to the first pre-cancerous lesion.

We have previously reported an analysis of the risk of progression from cervical HPV infection to pre-cancerous lesions or clearance of infection from the PApilloma TRial against Cancer In young Adults (PATRICIA), a phase III trial of the HPV-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine (Cervarix®) in over 18,000 young women [17]. Here, we report an analysis of the time between first sexual intercourse and acquisition of the first cervical HPV infection or development of the first pre-cancerous lesion.

Methods

This analysis was based on data obtained from the control arm of the double-blind, randomized, multinational (14 countries), controlled, 4-year PATRICIA trial which enrolled women aged 15-25 years. The objectives were to investigate the time between first sexual activity and either detection of the first cervical HPV infection or development of the first cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN), and associated factors.

Study population and procedures

The PATRICIA trial design has been described previously [18],[19]. Written informed consent to participate in the clinical trial was obtained from all adult participants; for minors, written informed consent was obtained from their parents or guardians and assent from the participants themselves.The protocol and other materials were approved by local independent ethics committees or institutional review boards (Additional file 1). The clinical trial was carried out in accordance with The Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki) and is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov under number NCT00122681.

PATRICIA enrolled women with no more than 6 lifetime sexual partners. The exclusion criterion of no more than six lifetime sexual partners was not applied in Finland, in accordance with local regulatory and ethical requirements, so women with more than six lifetime sexual partners enrolled in Finland were included in the trial [20]. The analysis was based on women from the control arm of the total vaccinated cohort for efficacy (TVC-E) which included all women who received at least one dose of control vaccine and had normal or low grade cytology at baseline. The present analysis included women who began sexual intercourse either during the follow-up period or less than 6 months before enrolment. Women beginning sexual intercourse during the study must not have had HPV infection detected before the first recorded date of sexual intercourse. However, women who began sexual intercourse within 6 months before enrolment were included regardless of whether they had a prevalent HPV infection at baseline or not.HPV genotyping of cervical liquid-based cytology samples by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was done at baseline and every 6 months. The Bethesda system was used for cytologic classification approximately every 12 months, with histologic classification of any biopsies. We tested for the following oncogenic HPV types: HPV-16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 66, and 68, and for the following non-oncogenic types: HPV-6, 11, 34, 40, 42, 43, 44, 53, 54, 70, and 74 [21].

A self-administered behavioral questionnaire collecting data on smoking, sexual activity, and contraception was completed 1 month after first vaccination and yearly thereafter during the follow-up period [22]. Participants were informed that the term sexual intercourse included penetrative, genital-to-genital, or oral-genital sexual contact.

Endpoint definitions

The first HPV infection detected or first CIN detected was used in the analysis. HPV infections were classified as an infection of any duration (HPVI) and as a 6-month persistent infection (6MPI). A 6MPI was defined as detection of the same HPV genotype in cervical samples at two consecutive evaluations over approximately a 6-month period i.e. a sequence of positive samples with the same HPV type not interrupted by negative samples over a total range of >5 months (>150 days). The start of the 6MPI was defined as the date of the first positive sample in the sequence. Histopathologically confirmed CIN was detected in biopsy samples after colposcopy or excision samples after treatment. Endpoints were defined as CIN grade 1 or greater (CIN1+) and CIN grade 2 or greater (CIN2+). Only HPV-positive lesions were included in the analysis.

Statistical analysis

Incidence rates for HPVI, 6MPI and CIN were calculated per 100 person-years (PY) according to individual HPV type, with 95% confidence intervals (CI). The time to detection of the first cervical HPV infection or development of the first CIN lesion was measured from the date of first sexual intercourse reported by the woman. Thus, although visits were scheduled for every 6 months, it was possible to establish a duration of infection of less than 6 months. The time between onset of sexual activity and detection of the first infection or CIN lesion was analysed using the Kaplan-Meier method as well as univariate and multivariable Cox proportional-hazards models. The statistical unit was the subject.

Nine potential factors (covariates) associated with acquisition of HPV infection were included in the models: region, tobacco exposure measured as number of pack-years (one pack-year was equivalent to 365 packs of cigarettes), age at first sexual intercourse (15-17 years and ≥18 years), number of sexual partners during the past 12 months, number of lifetime sexual partners, history of Chlamydia trachomatis during the past 12 months, marital/partner status, use of hormones for contraception or other indication, and duration of use of hormones for contraception or other indication. The number of lifetime sexual partners was determined from the behavioral questionnaire. All behavioural covariates were considered as time dependent and therefore no proportional hazard checks were required. Region and age were considered as time-fixed covariates and the hazard assumptions were assessed directly from the Kaplan-Meier curves. In addition, for the time to detection of a 6MPI, CIN1+ and CIN2+, the models also included previous cervical HPV infection as a time-varying covariate. Previous cervical HPV infection was defined as an HPV infection preceding the onset of the referent 6MPI or preceding the onset of the referent infection associated with a CIN1+ or CIN2 +.

Data were censored for women who completed the study at 54 months after first sexual intercourse (although follow-up lasted for 48 months, women were included in the analysis if they had their first sexual experience within 6 months before enrolment). For women who did not complete the study, data were censored at their last recorded visit. Covariates with a p-value <0.2 in the univariate model were included in the multivariable models, with the exception of region which was always included regardless of the p-value obtained. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.2.

Results

Subject disposition and characteristics

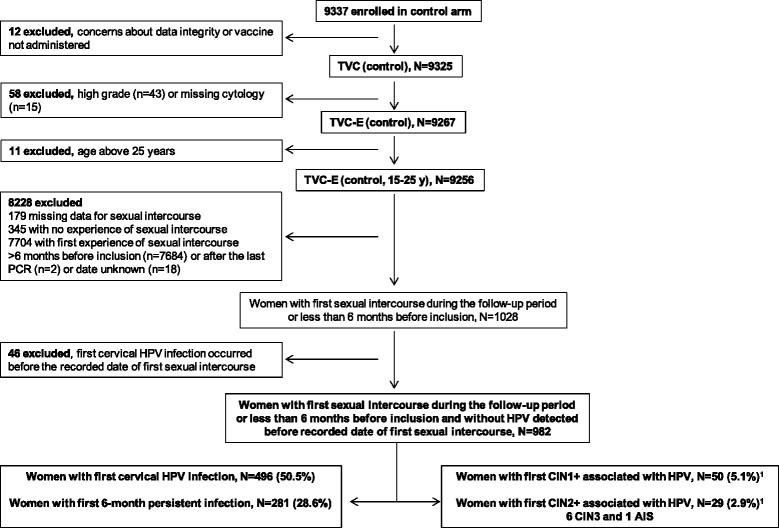

A total of 982 women who experienced first sexual intercourse during the study and had no HPV infection detected before the recorded date of their first experience of sexual intercourse, and women who experienced first sexual intercourse less than 6 months before inclusion, were included in the analysis (Figure 1). Among these 982 women, mean age was 17.4 years (standard deviation 2.13), and most were from Europe (65.6%, with 60.8% from Finland), followed by Asia-Pacific (17.1%), North America (9.6%) and Latin America (7.7%). Most women included in the present analysis had not experienced sexual intercourse before study entry (n = 793, 80.8%), 169 women (17.2%) had experienced first sexual intercourse within 6 months prior to study entry, and data on sexual history were missing for 20 women (2.0%). Eight (4.7%) and nine (5.3%) of the women who experienced first sexual intercourse prior to study entry were seropositive for HPV-16 or HPV-18, respectively, at study entry.

Figure 1.

Subject disposition.

First cervical HPV infection of any duration and 6-month persistent infection: incidence and association of covariates

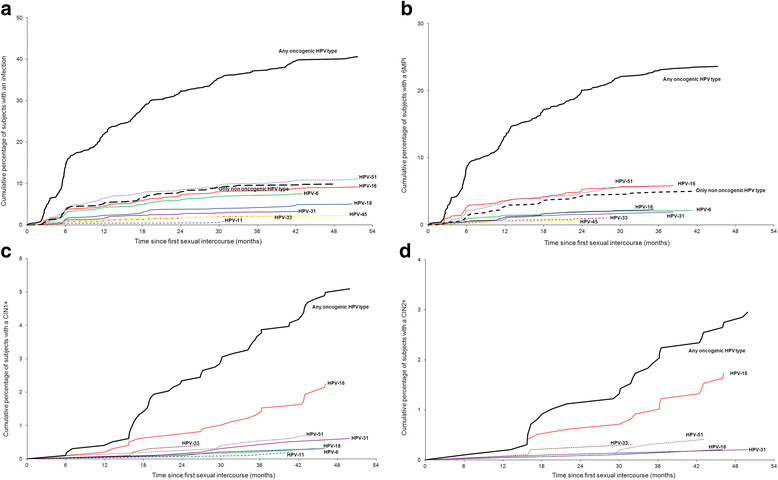

An HPVI was detected in 496 women (50.5%; 27.08 per 100 person-years) (Table 1). No HPVI had been detected by the end of the follow-up period in 446 women (45.4%) who completed the study, and no HPVI had been detected by the time of their last visit in 40 women (4.1%) who discontinued before the end of the study. Corresponding values for 6MPI were 281 (28.6%; 13.29 per 100 person-years), 648 (66.0%) and 53 (5.4%). The first cases of HPV infections were detected within 2-3 months after sexual initiation and the cumulative number of women with an infection increased progressively throughout follow-up for both HPVI and 6MPI (Figure 2a and b). The cumulative percentage of women infected with any HPV type at 12, 18, 24, 36 and 48 months was 28%, 36%, 44%, 53% and 62%, respectively (Figure 2a).

Table 1.

Incidence of first cervical HPVI, 6MPI, CIN1+ and CIN2+

| HPV type | HPVI (N = 496) | 6MPI (N = 281) | CIN1+ (N = 50) | CIN2+ (N = 29) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | Incidence per 100 PY (95% CI) 1 | n (%) | Incidence per 100 PY (95% CI) 1 | n (%) | Incidence per 100 PY (95% CI) 1 | n (%) | Incidence per 100 PY (95% CI) 1 | |

| All | 496 (50.5)2 | 27.08 (24.75-29.57) | 281 (28.6)2 | 13.29 (11.78-14.94) | 50 (5.1)2 | 1.87 (1.39-2.46) | 29 (3.0)2 | 1.07 (0.72-1.54) |

| Oncogenic HPV types | ||||||||

| 16 | 90 (18.2) | 4.91 (3.95-6.04) | 58 (20.6) | 2.74 (2.08-3.55) | 22 (44.0) | 0.82 (0.52-1.24) | 17 (58.6) | 0.63 (0.37-1.01) |

| 18 | 50 (10.1) | 2.73 (2.03-3.60) | 23 (8.2) | 1.09 (0.69-1.63) | 3 (6.0) | 0.11 (0.02-0.33) | 2 (6.9) | 0.07 (0.01-0.27) |

| 31 | 32 (6.5) | 1.75 (1.20-2.47) | 19 (6.8) | 0.90 (0.54-1.40) | 6 (12.0) | 0.22 (0.08-0.49) | 2 (6.9) | 0.07 (0.01-0.27) |

| 33 | 21 (4.2) | 1.15 (0.71-1.75) | 10 (3.6) | 0.47 (0.23-0.87) | 4 (8.0) | 0.15 (0.04-0.38) | 3 (10.3) | 0.11 (0.02-0.32) |

| 35 | 9 (1.8) | 0.49 (0.22-0.93) | 3 (1.1) | 0.14 (0.03-0.41) | 1 (2.0) | 0.04 (0.00-0.21) | 0 | 0.00 (0.00-0.14) |

| 39 | 34 (6.9) | 1.86 (1.29-2.59) | 20 (7.1) | 0.95 (0.58-1.46) | 3 (6.0) | 0.11 (0.02-0.33) | 2 (6.9) | 0.07 (0.01-0.27) |

| 45 | 22 (4.4) | 1.20 (0.75-1.82) | 6 (2.1) | 0.28 (0.10-0.62) | 1 (2.0) | 0.04 (0.00-0.21) | 0 | 0.00 (0.00-0.14) |

| 51 | 109 (22.0) | 5.95 (4.89-7.18) | 57 (20.3) | 2.70 (2.04-3.49) | 7 (14.0) | 0.26 (0.11-0.54) | 4 (13.8) | 0.15 (0.04-0.38) |

| 52 | 61 (12.3) | 3.33 (2.55-4.28) | 35 (12.5) | 1.66 (1.15-2.30) | 4 (8.0) | 0.15 (0.04-0.38) | 2 (6.9) | 0.07 (0.01-0.27) |

| 56 | 44 (8.9) | 2.40 (1.75-3.23) | 19 (6.8) | 0.90 (0.54-1.40) | 5 (10.0) | 0.19 (0.06-0.44) | 3 (10.3) | 0.11 (0.02-0.32) |

| 58 | 22 (4.4) | 1.20 (0.75-1.82) | 14 (5.0) | 0.66 (0.36-1.11) | 7 (14.0) | 0.26 (0.11-0.54) | 2 (6.9) | 0.07 (0.01-0.27) |

| 59 | 26 (5.2) | 1.42 (0.93-2.08) | 1 (0.4) | 0.05 (0.00-0.26) | 0 | 0.00 (0.00-0.14) | 0 | 0.00 (0.00-0.14) |

| 66 | 46 (9.3) | 2.51 (1.84-3.35) | 24 (8.5) | 1.14 (0.73-1.69) | 4 (8.0) | 0.15 (0.04-0.38) | 1 (3.5) | 0.04 (0.00-0.21) |

| 68 | 37 (7.5) | 2.02 (1.42-2.78) | 17 (6.1) | 0.80 (0.47-1.29) | 4 (8.0) | 0.15 (0.04-0.38) | 3 (10.3) | 0.11 (0.02-0.32) |

| At least 1 oncogenic type | 399 (80.4) | 21.79 (19.70-24.03) | 232 (82.6) | 10.97 (9.61-12.48) | 50 (100.0) | 1.87 (1.39-2.46) | 29 (100) | 1.07 (0.72-1.54) |

| Non-oncogenic HPV types | ||||||||

| 6 | 74 (14.9) | 4.04 (3.17-5.07) | 21 (7.5) | 0.99 (0.61-1.52) | 3 (6.0) | 0.11 (0.02-0.33) | 1 (3.5) | 0.04 (0.00-0.21) |

| 11 | 9 (1.8) | 0.49 (0.22-0.93) | 1 (0.4) | 0.05 (0.00-0.26) | 2 (4.0) | 0.07 (0.01-0.27) | 0 | 0.00 (0.00-0.14) |

| 34 | 7 (1.4) | 0.38 (0.15-0.79) | 1 (0.4) | 0.05 (0.00-0.26) | 0 | 0.00 (0.00-0.14) | 0 | 0.00 (0.00-0.14) |

| 40 | 16 (3.2) | 0.87 (0.50-1.42) | 1 (0.4) | 0.05 (0.00-0.26) | 2 (4.0) | 0.07 (0.01-0.27) | 1 (3.5) | 0.04 (0.00-0.21) |

| 42 | 7 (1.4) | 0.38 (0.15-0.79) | 0 | 0.00 (0.00-0.17) | 0 | 0.00 (0.00-0.14) | 0 | 0.00 (0.00-0.14) |

| 43 | 27 (5.4) | 1.47 (0.97-2.14) | 3 (1.1) | 0.14 (0.03-0.41) | 0 | 0.00 (0.00-0.14) | 0 | 0.00 (0.00-0.14) |

| 44 | 4 (0.8) | 0.22 (0.06-0.56) | 1 (0.4) | 0.05 (0.00-0.26) | 0 | 0.00 (0.00-0.14) | 0 | 0.00 (0.00-0.14) |

| 53 | 56 (11.3) | 3.06 (2.31-3.97) | 28 (10.0) | 1.32 (0.88-1.91) | 3 (6.0) | 0.11 (0.02-0.33) | 2 (6.9) | 0.07 (0.01-0.27) |

| 54 | 16 (3.2) | 0.87 (0.50-1.42) | 8 (2.9) | 0.38 (0.16-0.75) | 3 (6.0) | 0.11 (0.02-0.33) | 2 (6.9) | 0.07 (0.01-0.27) |

| 70 | 6 (1.2) | 0.33 (0.12-0.71) | 6 (2.1) | 0.28 (0.10-0.62) | 1 (2.0) | 0.04 (0.00-0.21) | 0 | 0.00 (0.00-0.14) |

| 74 | 13 (2.6) | 0.71 (0.38-1.21) | 6 (2.1) | 0.28 (0.10-0.62) | 0 | 0.00 (0.00-0.14) | 0 | 0.00 (0.00-0.14) |

| Only non-oncogenic type | 97 (19.6) | 5.30 (4.29-6.46) | 49 (17.4) | 2.32 (1.71-3.06) | 0 | 0.00 (0.00-0.14) | 0 | 0.00 (0.00-0.14) |

1Number of person-years: 1831.46 (HPVI); 2114.51 (6MPI); 2676.71 (CIN1+); 2703.47 (CIN2+).

2 N = 982.

Some women experienced concomitant HPV infections, concomitant CIN lesions and/or CIN lesions associated with more than 1 HPV type. Therefore the number of observations for each individual HPV type do not add up to the total number of women experiencing an infection or lesion (N).

6MPI: 6-month persistent HPV infection; CI: confidence interval; CIN: cervical intraepithelial neoplasia; HPV: human papillomavirus; HPVI: HPV infection of any duration; PY: person-years.

Figure 2.

Risk of developing a first cervical HPV infection or lesion following first sexual intercourse. a. HPVI. b. 6MPI. c. CIN1+. d. CIN2+. Any oncogenic HPV type: HPV-16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 66, and 68.

Among oncogenic HPV types, the most commonly detected HPVIs were HPV-51 (5.95 per 100 PY), HPV-16 (4.91 per 100 PY), HPV-52 (3.33 per 100 PY), HPV-18 (2.73 per 100 PY), and HPV-66 (2.51 per 100 PY) (Table 1). These types were also the most commonly detected 6MPIs, although HPV-18 was slightly less common than HPV-66 (Table 1). HPV-6 and HPV-53 were the most common non-oncogenic HPV types detected in HPVI (4.04 and 3.06 per 100 PY, respectively) and 6MPI (0.99 and 1.32 per 100 PY, respectively) (Table 1). The incidence of infection with at least one oncogenic HPV type was considerably higher than the incidence of infection with only non-oncogenic types: 21.79 versus 5.30 per 100 PY, respectively, for HPVI, and 10.97 versus 2.32 per 100 PY, respectively, for 6MPI (Table 1; Figure 2a and b).

In the multivariable analysis, the main covariate associated with increased risk of acquiring an HPVI was a higher number of lifetime sexual partners. The hazard ratio [HR] was 4.76 (95% CI: 3.82-5.95) and 19.22 (14.02-26.34) for 2-3 partners and ≥4 partners, respectively (Table 2). Other covariates significantly associated with increased risk were history of infection with Chlamydia trachomatis (HR: 3.00 [2.07-4.36]) and cumulative duration of hormone use (HR: 2.18 [1.68-2.83] for 1-12 months, 3.26 [2.45-4.34] for 13-48 months and 5.42 [2.84-10.36] for >48 months). Being a single woman was significantly associated with an increased risk of acquiring an HPVI (HR: 1.45 [1.04-2.04]) compared with living with a partner currently or in the past. Tobacco exposure did not increase the risk in the multivariable analysis, although it was significant in the univariate analysis (HR: 1.66 [1.33-2.08], p < 0.0001).

Table 2.

Factors associated with risk of the first cervical HPVI or 6MPI (multivariable Cox proportional-hazards analysis)

| Covariate | Category | HPVI | 6MPI | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of women (N = 982) | No. of women with HPVI (N = 496) | HR (95% CI) | p-value | No. of women (N = 982) | No. of women with 6MPI (N = 281) | HR (95% CI) | p-value | ||

| Region | Europe | 644 | 345 | 1 | 644 | 201 | 1 | ||

| Asia Pacific | 168 | 58 | 1.11 (0.81-1.52) | 0.5055 | 168 | 36 | 1.21 (0.78-1.86) | 0.3995 | |

| Latin America | 76 | 46 | 1.16 (0.84-1.60) | 0.3627 | 76 | 24 | 0.99 (0.63-1.57) | 0.9773 | |

| North America | 94 | 47 | 0.88 (0.64-1.20) | 0.4273 | 94 | 20 | 0.75 (0.47-1.20) | 0.2283 | |

| 0.5498 | 0.4934 | ||||||||

| Number of lifetime sexual partners1 | 1 | 800 | 234 | 1 | 800 | 127 | 1 | ||

| 2-3 | 430 | 190 | 4.76 (3.82-5.95) | <0.0001 | 470 | 111 | 4.19 (3.12-5.63) | <0.0001 | |

| ≥4 | 125 | 72 | 19.22 (14.02-26.34) | <0.0001 | 166 | 43 | 14.14 (9.35-21.37) | <0.0001 | |

| <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||||||

| History of Chlamydia trachomatis during the past 12 months1 | No | 977 | 463 | 1 | 978 | 257 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 60 | 33 | 3.00 (2.07-4.36) | <0.0001 | 73 | 24 | 2.50 (1.57-4.00) | 0.0001 | |

| <0.0001 | 0.0001 | ||||||||

| Cumulative duration of hormone use for contraception or other indication1 | No use | 804 | 105 | 1 | 804 | 59 | 1 | ||

| 1-12 months | 727 | 173 | 2.18 (1.68-2.83) | <0.0001 | 746 | 111 | 2.10 (1.48-2.98) | <0.0001 | |

| 13-48 months | 536 | 206 | 3.26 (2.45-4.34) | <0.0001 | 590 | 108 | 2.79 (1.91-4.09) | <0.0001 | |

| >48 months | 56 | 11 | 5.42 (2.84-10.36) | <0.0001 | 69 | 2 | 1.62 (0.39-6.74) | 0.5107 | |

| <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||||||||

| Marital/partner status1 | Living or lived with partner | 238 | 42 | 1 | 271 | 19 | 1 | ||

| Single | 961 | 454 | 1.45 (1.04-2.04) | 0.0291 | 963 | 262 | 1.75 (1.01-3.03) | 0.0445 | |

| 0.0291 | 0.0445 | ||||||||

| Tobacco exposure (number of pack-years)1 | <0.5 | 862 | 402 | 1 | 862 | 223 | 1 | ||

| ≥0.5 | 153 | 94 | 1.17 (0.92-1.47) | 0.1936 | 161 | 58 | 1.22 (0.90-1.66) | 0.2085 | |

| 0.1936 | 0.2085 | ||||||||

| Previous cervical HPV infection1 | No | - | - | - | - | 965 | 231 | 1 | |

| Yes | - | - | - | - | 188 | 38 | 0.49 (0.33-0.72) | 0.0003 | |

| - | 0.0003 | ||||||||

1Time-varying covariates. The number of women represents the number of observations that appeared at least once during the follow-up period. One woman can be counted in several categories. The number of events (HPVI or 6MPI) corresponds to the value recorded at the most recent visit before the endpoint.

Values in italics are the overall p-value.

Age at first sexual intercourse was not included in the multivariable analyses because p-values of >0.2 were obtained in the univariate analyses. The covariates of number of sexual partners during the past 12 months and hormone use or not for contraception or another indication were not included in the multivariable analyses because of overlap with the covariates of number of lifetime sexual partners and cumulative duration of hormone use or other indication, respectively.

6MPI: 6-month persistent HPV infection; CI: confidence interval; HPV: human papillomavirus; HPVI: HPV infection of any duration; HR: Hazard ratio.

The same covariates were significantly associated with higher risk of a 6MPI in the multivariable analysis, with the exception of hormone use for >48 months (Table 2). Being single was again significantly associated with higher risk of a 6MPI (HR: 1.75 [1.01-3.03]); previous cervical HPV infection was associated with lower risk (HR: 0.49 [0.33-0.72]) (Table 2).

First cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 1 or greater and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 or greater: incidence and association of covariates

Few cases of CIN1+ or CIN2+ were observed. A CIN1+ was detected in 50 women (5.1%; 1.87 per 100 person-years) (Table 1). No CIN1+ had been detected by the end of the follow-up period in 866 women (88.2%) who completed the study, and no CIN1+ had been detected by the time of their last visit in 66 women (6.7%) who discontinued before the end of the study. Corresponding values for CIN2+ were 29 (3.0%; 1.07 per 100 person-years), 886 (90.2%) and 67 (6.8%). The first cases of CIN1+ lesions were detected approximately 6 months following sexual initiation. The cumulative proportion of women developing a CIN1+ lesion was 3% at 24 months and 10% at 48 months (Figure 2c). The first cases of CIN2+ lesions were detected within approximately 12-18 months after sexual initiation; the cumulative proportion of women developing a CIN2+ lesion was 1% at 24 months and 6% at 48 months (Figure 2d). CIN lesions were most commonly associated with HPV-16 (Table 1; Figure 2c and d). Other oncogenic HPV types most often detected in a CIN lesion were HPV-51, HPV-58, and HPV-31. No lesions associated only with non-oncogenic HPV types were found (Table 1).

The covariate most strongly associated with increased risk of CIN1+ in the multivariable analysis was previous cervical HPV infection (HR: 35.70 [95% CI: 8.47-150.50]) (Table 3). Having ≥4 lifetime sexual partners was also significantly associated with increased risk (HR: 5.60 [2.28-13.77]). Cumulative duration of hormone use was associated with higher risk, but just failed to achieve statistical significance (HR: 3.61 [0.94-13.86], 3.84 [1.00-14.77] and 6.09 [0.89-41.63] for 1-12, 13-48 and >48 months, respectively). Being from the Asia-Pacific region was significantly associated with increased risk (HR: 2.99 [1.03-8.70]), although it should be noted that only six women from this region experienced CIN1 +.

Table 3.

Factors associated with risk of the first CIN1+ or CIN2+ (multivariable Cox proportional-hazards analysis)

| Covariate | Category | CIN1+ | CIN2+ | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of women (N = 982) | No. of women with CIN1+ (N = 50) | HR (95% CI) | p-value | No. of women (N = 982) | No. of women with CIN2+ (N = 29) | HR (95% CI) | p-value | ||

| Region | Europe | 644 | 35 | 1 | 644 | 21 | 1 | ||

| Asia Pacific | 168 | 6 | 2.99 (1.03-8.70) | 0.0441 | 168 | 3 | 0.76 (0.20-2.93) | 0.6942 | |

| Latin America | 76 | 3 | 1.18 (0.34-4.05) | 0.7932 | 76 | 1 | 0.57 (0.07-4.37) | 0.5869 | |

| North America | 94 | 6 | 1.93 (0.80-4.68) | 0.1439 | 94 | 4 | 1.73 (0.58-5.18) | 0.3238 | |

| 0.1480 | 0.6452 | ||||||||

| Age at first sexual intercourse | ≥18 years | 801 | 41 | 1 | 801 | 26 | 1 | ||

| 15-17 years | 181 | 9 | 0.46 (0.21-1.02) | 0.0545 | 181 | 3 | 0.18 (0.05-0.64) | 0.0086 | |

| 0.0545 | 0.0086 | ||||||||

| Number of lifetime sexual partners1 | 1 | 800 | 9 | 1 | 800 | 5 | 1 | ||

| 2-3 | 537 | 15 | 1.73 (0.72-4.15) | 0.2213 | 537 | 10 | 1.93 (0.63-5.92) | 0.2529 | |

| ≥4 | 245 | 26 | 5.60 (2.28-13.77) | 0.0002 | 248 | 14 | 4.02 (1.24-13.05) | 0.0203 | |

| 0.0001 | 0.0504 | ||||||||

| Cumulative duration of hormone use for contraception or other indication1 | No use | 804 | 3 | 1 | Not included | ||||

| 1-12 months | 786 | 13 | 3.61 (0.94-13.86) | 0.0614 | |||||

| 13-48 months | 707 | 32 | 3.84 (1.00-14.77) | 0.0502 | |||||

| >48 months | 102 | 2 | 6.09 (0.89-41.63) | 0.0653 | |||||

| 0.2157 | |||||||||

| Tobacco exposure (number of pack-years)1 | <0.5 | 862 | 36 | 1 | Not included | ||||

| ≥0.5 | 177 | 14 | 1.44 (0.76-2.74) | 0.2622 | |||||

| 0.2622 | |||||||||

| Previous cervical HPV infection1 | No | 974 | 2 | 1 | 975 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 431 | 48 | 35.70 (8.47-150.50) | <0.0001 | 432 | 28 | 42.30 (5.61-318.63) | 0.0003 | |

| <0.0001 | 0.0003 | ||||||||

1Time-varying covariates. The number of women represents the number of observations that appeared at least once during the follow-up period. One woman can be counted in several categories. The number of events (CIN1+ or CIN2+) corresponds to the value recorded at the most recent visit before the endpoint.

Values in italics are the global p-value.

History of Chlamydia trachomatis (CIN1+ and CIN2+), cumulative duration of hormone use (CIN2+), marital/partner status (CIN1+ and CIN2+) and tobacco exposure (CIN2+) were not included in the multivariable analyses because p-values of >0.2 were obtained in the univariate analyses. The covariates of number of sexual partners during the past 12 months and hormone use or not for contraception or another indication were not included in the multivariable analyses because of overlap with the covariates of number of lifetime sexual partners and cumulative duration of hormone use or other indication, respectively.

CI: confidence interval; CIN: cervical intraepithelial neoplasia; HPV: human papillomavirus; HR: hazard ratio.

Previous cervical HPV infection also had the greatest influence on risk of developing CIN2+, with a HR of 42.30 (5.61-318.63), and having ≥4 lifetime sexual partners was also associated with higher risk (HR: 4.02 [1.24-13.05]) (Table 3). Age 15-17 years at first sexual intercourse was significantly associated with lower risk of developing CIN2+ compared with age ≥18 years; however, only 3 women with first experience of sexual intercourse at age 15-17 years experienced a CIN2 +.

A sensitivity analysis not including the factor of previous infection in the model did not change the HR for the other covariates for CIN1+ and CIN2+ (data not shown). Likewise, a sensitivity analysis of all lesions (including both HPV-positive and HPV-negative cases) revealed similar results except for CIN2+ where the cumulative duration of hormone use had a univariate p-value <0.2 and was thus included in the multivariable analysis (whereas it was not included in the multivariable analysis of HPV-positive CIN2+). However, it was not significant in the multivariable analysis.

Discussion

The analysis confirmed that HPV infection may be acquired relatively quickly following first sexual intercourse. The first cases of HPV infections were detected within 2-3 months following sexual initiation, and two thirds of women had acquired an infection within the 48 month follow-up period. Persistent infections were less common, detected in approximately one-quarter of women. The first cases of CIN1+ lesions were detected approximately 6 months following sexual initiation, and the first CIN2+ lesions approximately 12-18 months, but both were experienced by very few women.

Other studies of virginal women experiencing sexual intercourse for the first time have shown broadly similar rates of oncogenic HPV acquisition, although it is difficult to compare estimates directly because of differences across studies in outcomes and follow-up times. At 2 years after sexual initiation, we found an incidence of HPV infection of 44%. Two previous studies have found slightly lower incidences at this time point. A population-based cohort study conducted in Denmark found an incidence of 35% among 70 women recruited as virgins and experiencing first sexual intercourse within the follow-up period [15], whilst a study of 444 HPV DNA-negative female students from the US (94 recruited as virgins and experiencing first sexual intercourse within the follow-up period) found an incidence of 39% for both women who were virgin and those who were sexually active at enrolment [13]. In the latter study, the minimum time between first sexual intercourse and detection of HPV was less than 1 month [13]. Likewise, the incidence of HPV infection at 3 years was 53% in our analysis, slightly higher than the 46% incidence at the same time point found among 242 women from the UK recruited within 6 months of first sexual intercourse and with only one partner [14]. In a study of 206 women from the Guanacaste cohort recruited as virgins and experiencing first sexual intercourse within the follow-up, the incidence of cervical HPV infection was 53% after a median follow-up of 3.6 years [16], compared with an incidence of 62% after 4 years in our analysis.

In our analysis, the most common oncogenic HPV types in HPVI and 6MPI were HPV-16 and HPV-51, followed by HPV-52, and then by HPV-18 and HPV-66. HPV-6 was the most common non-oncogenic type; however, its incidence may be underestimated because the study did not systematically evaluate the external genital tract. In the overall PATRICIA cohort, the most common prevalent HPV types at study entry were HPV-16, followed by HPV-51, HPV-18, and HPV-31 [22]. This is in line with previous studies of the occurrence of different HPV types, although there is considerable variation between studies and regions in the exact ranking and incidence of the different types, and 95% confidence intervals of incidence are broad. In the Guanacaste subcohort of women recruited as virgins, the most common oncogenic HPV types detected were HPV-16, HPV-66, and HPV-52; HPV-53 was the most common non-oncogenic type detected [16]. Amongst HPV DNA-negative students from the US, the most common HPV types detected at first infection were HPV-16, HPV-56, and HPV-6 [13]. A meta-analysis of more than 1 million women worldwide found HPV-16 to be by far the most common type in women with normal cytology, followed by HPV-18, HPV-52, HPV-31, and HPV-58 [23].

Few women experienced CIN1+ and even fewer experienced CIN2+, so estimates of time to lesion development and the most common HPV type associated with CIN lesions have somewhat low precision. However, it was clear that HPV-16 was by far the most frequent type found in CIN1+ and CIN2+, as seen in other studies [24],[25].

In our analysis, higher number of lifetime sexual partners was most strongly associated with a higher risk of an HPVI or 6MPI. History of Chlamydia trachomatis infection and longer cumulative duration of hormone use also significantly increased the risk of acquisition. Although the univariate analysis indicated an increased risk for HPVI with tobacco exposure, the multivariable analysis showed no significant association. For the overall PATRICIA cohort, infection with HPV at entry was significantly associated with not being married or living with a partner, tobacco exposure, age <15 years at first sexual intercourse, higher number of sexual partners during the past 12 months, longer duration of hormone use, and history of a sexually transmitted infection [22]. The PATRICIA findings are in line with previous studies of risk factors influencing acquisition of HPV infection. In the Danish study of women experiencing first sexual intercourse mentioned previously, having ≥3 sexual partners increased the risk of infection 9-fold; age, smoking habits, oral contraceptive use, and age at first sexual intercourse were not significantly associated with infection [15]. In the US study of students, current smoking, current oral contraceptive use, higher number of lifetime sexual partners, male partners’ number of prior sexual partners, and knowing a partner for less than 8 months before sexual intercourse were predictors of HPV infection [13].

Previous cervical HPV infection was associated with lower risk of a 6MPI with any HPV type, perhaps indicating a protective effect of naturally acquired antibodies to the prior infection. In contrast, previous cervical HPV infection was strongly associated with increased risk of developing CIN1+ and CIN2+. In another analysis of the whole PATRICIA control group, previous infection with an oncogenic HPV type was also significantly associated with increased risk of developing CIN1+ and CIN2+ [17]. Accumulation of HPV infections may indicate that an individual's immune system may have limited ability to clear infections, thus increasing their risk of developing CIN. In contrast to our findings, some studies have shown that there is a higher chance of acquiring a new HPV type if already infected [26]-[28]. Unfortunately, in the PATRICIA trial, information on HPV serology over time was only available for a sub-cohort of women, and the number of women in the control group of the immunogenicity cohort who had not initiated sexual intercourse at enrolment was too small for meaningful analysis to explore the role of serology in the risk of HPV infections and CIN.

Four or more lifetime sexual partners was also associated with increased risk of CIN1+ and CIN2+. An association between cervical cancer and higher number of sexual partners has been seen in previous studies [8]. Younger age at first sexual intercourse was associated with lower risk of CIN2+; however, as there were only three cases of CIN2+ in the 15-17 year age group, this finding should be interpreted cautiously. Younger age at first sexual intercourse has been previously shown to be associated with increased risk of cervical cancer [8].

A strength of our analysis is that participants of the PATRICIA study were well-characterized, with high follow-up rates over 4 years and standardized virologic and histologic sampling methods. Although the population of the present analysis was a relatively small subset of the entire PATRICIA population, more women were included in this analysis than in any other study of virginal women. Study limitations included the fact that women from Finland made up approximately two thirds of the population who had not had experience of sexual intercourse before enrolment, a consequence of the school-based trial recruitment strategy in Finland. In addition, PATRICIA included only women aged 15-25 years with no history of immunosuppressive disease, limiting its generalizability. The smaller population in the present analysis meant that the 4-year follow-up period was long enough to detect only a small number of CIN cases, limiting the conclusions that can be drawn about the time between first sexual intercourse and development of pre-cancerous lesions.

Conclusion

Infection with HPV can occur within 2-3 months following first sexual intercourse, and the first CIN1+ lesions within approximately 6 months. The role of previous cervical HPV infection in increasing the risk of developing a pre-cancerous lesion is confirmed, as is the role of the number of lifetime sexual partners in acquisition of an HPV infection. Our estimates of time to infection and time to CIN after sexual initiation are important as they will inform modeling exercises on the natural history of cervical carcinogenesis and the impact of HPV vaccination programs. Furthermore, without underestimating the value of vaccination at older ages, our findings emphasize the importance of vaccinating at a young age, well before girls begin sexual activity, most likely achieved via school-based vaccination programs.

Additional file

Electronic supplementary material

Additional file 1: List of Independent Ethics Committees/ Institutional Review Boards. (DOC 572 KB)

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Acknowledgements

We thank all study participants and their families. We gratefully acknowledge the work of the central and local study coordinators, and staff members of the sites that participated in this study.

Contribution to statistical support was provided by D Rosillon and M-P David (GlaxoSmithKline Vaccines, Wavre, Belgium), A Raillard, S Collas De Souza, M-Cecile Bozonnat (4 Clinics, Paris, France) on behalf of GlaxoSmithKline Vaccines, Wavre, Belgium.

Writing support services were provided by M Greenacre PhD (An Sgriobhadair Ltd) on behalf of GlaxoSmithKline Vaccines, Wavre, Belgium; editing and publication co-ordinating services were provided by J Andersson PhD (CROMSOURCE Ltd, UK) on behalf of GlaxoSmithKline Vaccines, Wavre, Belgium.

The HPV PATRICIA Study Group: Collaborators

Principal investigators/co-investigators : Australia I Denham, S M Garland, A Mindel, S R Skinner. Belgium P De Sutter, W A J Poppe, W Tjalma. Brazil N S De Carvalho, P Naud, J C Teixeira. Canada F Y Aoki, F Diaz-Mitoma, M Dionne, L Ferguson, M Miller, K Papp, B Ramjattan, B Romanowski, P H Orr, R Somani Finland D Apter, T Karppa, N Kudjoi, L Kyha-Österlund, M Lehtinen, K Lönnberg, T Lunnas, J Paavonen, J Palmroth, T Petaja, M Vilkki. Germany T Gent, T Grubert, W D Höpker, K Peters, K Schulze, TF Schwarz. Mexico J Salmerón. Philippines C Crisostomo, MR Del Rosario-Raymundo, JE Raymundo, M J Germar, G Limson, C Remollino, G Villanueva, S Villanueva, J D Zamora. Spain J Bajo-Arenas, J Bayas, M Campins, X Castellsagué, M Castro, C Centeno, ML Rodríguez de la Pinta, A Torné, J A Vidart. Taiwan S N Chow, M H Yu. Thailand S Angsuwathana, U Jaisamrarn. UK M Cruickshank, E A Hakim, H Kitchener, D Lewis, A Szarewski (deceased). USA R Ackerman, M Caldwell, C Chambers, A Chatterjee, L DeMars, L Downs, D Ferris, P Fine, J Hedrick, W Huh,T Klein, J Lalezari, S Luber, M Martens, C Peterson, J Rosen, L Seidman, M Sperling, R Sperling, M Stager, J Stapleton, K Swenson, C Thoming, L Twiggs, A Waldbaum, C M Wheeler.

Other contributors:

GlaxoSmithKline clinical study support: A Camier, B Colau, S Genevrois, P Marius, N Martens, T Ouammou, M Rahier, B Spiessens, A Meurée, N Houard, F Dessy, A Tonglet , A S Vilain, C Van Hoof (Xpe Pharma), D Descamps, K Hardt, V Xhenseval.

Laboratory contribution: E Alt, B Iskaros, A Limaye, R D Luff, M McNeeley, B Winkler (Quest Diagnostics Clinical Trials, Teterboro, NJ, USA). A Molijn, W Quint, L Struijk, M Van de Sandt, L J Van Doorn (DDL Diagnostic Laboratory, Voorburg, The Netherlands).

Endpoint committee: N Kiviat, K P Klugman, P Nieminen.

Independent Data Monitoring Committee: C Bergeron, E Eisenstein, R Marks,T Nolan, S K Tay.

Funding

This work was supported by GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals SA. GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals SA was the funding source and was involved in all stages of the study conduct and analysis (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT00122681). GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals SA also took in charge all costs associated with the development and the publishing of the present manuscript.--CERVARIX is a registered trademark of the GlaxoSmithKline group of companies.

Footnotes

Competing interests

DR, GD, FS and LB are paid employees of the GlaxoSmithKline group of companies, the funder of this study. GD, FS and LB own stocks or shares in GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals SA. GD has a patent issued in the HPV field, and a patent issued in the herpes simplex virus vaccine field. MCB has received consulting fees to 4Clinics (employer). XC reports grants via his institution from GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals SA during the conduct of the study, and grants and personal fees from GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals SA, grants and personal fees from Sanofi Pasteur, Merck Sharp & Dohme (SPMSD). TFS reports personal fees from GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals SA. NSDC has received grants from IPAMI and personal fees from Instituto de Ensino e Pesquisas Clinicas, Brazil, and travel support during the conduct of the study. PN has received grants from GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals SA. ML has received grants for HPV vaccination studies through his employer University of Tampere, Finland and from Merck & Co. Inc. and GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals SA. BR reports grants received by her institution for research studies from GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals SA and from Merck & Co. Inc., and she received grants via her professional corporation from GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals SA for speaking engagements and travel support to attend international meetings and present research data. CMW reports grants from GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals SA who funded the University of New Mexico to conduct the trial in which the women were enroled, and CMW has received reagents and equipment from Roche Molecular Systems through the University of New Mexico for HPV genotyping, and funding from GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals SA for HPV vaccine trials and travel related to publication activities through the University of New Mexico. JCT reports grants, personal fees and non-financial support from GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals SA, during the conduct of the study; grants, personal fees and non-financial support from GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals SA, outside the submitted work. JP (Paavonen) reports research funding from GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals SA through the Helsinki University Hospital Research Institute to conduct clinical trials on HPV vaccines. JP (Paavonen) has also received research funding from Merck Sharp & Dohme (MSD) through the Helsinki University Hospital Research Institute to conduct clinical trials on HPV vaccines, outside the submitted work. SRS reports grants from GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals SA during the conduct of the study and reimbursement to her institution for costs associated with travel to conferences to present data from this clinical trial and she received grants from CSL Ltd and an honorarium was paid to her institution from GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals SA for attendance at Advisory Board meeting. UJ received grants from GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals SA for the study through Chulalongkorn University, and also support for traveling to investigator meetings. SMG reports grants to perform phase III clinical trials via her institution from GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals SA, Merck & Co. Inc and from CSL, and she has received payment from GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals SA for development of an educational programme and received honorarium from Merck & Co. Inc, Sanofi Pasteur. FXB reports grants and personal fees from GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals for attending Advisory Boards, speakers bureau and research, grants and personal fees from Merck Sharp & Dohme, Sanofi Pasteur, and grants from Qiagen outside the submitted work. MRDRR reports payment of honorarium as Principal Investigator and support for travel to meetings for the study from GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals SA during the conduct of the study and payment for lectures including service on speakers bureaus from GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals SA outside the submitted work. JP (Palmroth) reports to have received travel support from Roche and Merck Sharp & Dohme for medical congresses abroad. KP, MJVG, SNC, and WAJP and WAAT have nothing to disclose.

Authors' contributions

XC, JP (Paavonen), UJ, CMW, SRS, LB and DR formed the manuscript core writing team. The corresponding author and the core writing team had full access to all the trial data including existing analyses and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. All other authors contributed to conception and design, or acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data. All authors reviewed and commented upon a draft of the manuscript and gave final approval to submit for publication. AS (deceased) reviewed and contributed to the development of the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Xavier Castellsagué, Email: xcastellsague@iconcologia.net.

Jorma Paavonen, Email: Jorma.Paavonen@hus.fi.

Unnop Jaisamrarn, Email: dr.unnop@yahoo.com.

Cosette M Wheeler, Email: CWheeler@salud.unm.edu.

S Rachel Skinner, Email: rachels5@chw.edu.au.

Matti Lehtinen, Email: matti.lehtinen@uta.fi.

Paulo Naud, Email: cacontrol@hcpa.ufrgs.br.

Song-Nan Chow, Email: snchow@ntu.edu.tw.

Maria Rowena Del Rosario-Raymundo, Email: runnymeadow@yahoo.com.

Julio C Teixeira, Email: juliotex@uol.com.br.

Johanna Palmroth, Email: johanna.palmroth@dnainternet.net.

Newton S de Carvalho, Email: infectogin@ufpr.br.

Maria Julieta V Germar, Email: jvgermar@yahoo.com.

Klaus Peters, Email: klaus@dr-peters.net.

Suzanne M Garland, Email: suzanne.garland@thewomens.org.au.

Willy AJ Poppe, Email: willy.Poppe@uz.kuleuven.ac.be.

Barbara Romanowski, Email: broman@docromanowski.com.

Tino F Schwarz, Email: t.schwarz@juliusspital.de.

Wiebren AA Tjalma, Email: wiebren.tjalma@uza.be.

F Xavier Bosch, Email: x.bosch@iconcologia.net.

Marie-Cecile Bozonnat, Email: mcbozonnat@4clinics.com.

Frank Struyf, Email: FRANK.STRUYF@GSK.COM.

Gary Dubin, Email: Gary.O.Dubin@gsk.com.

Dominique Rosillon, Email: DOMINIQUE.X.ROSILLON@GSK.COM.

Laurence Baril, Email: LAURENCE.X.BARIL@GSK.COM.

References

- 1.World Health Organization: Human papillomavirus laboratory manual. First edition. In 2009 , [http://www.who.int/immunization/documents/WHO_IVB_10.12/en/]

- 2.Koshiol J, Lindsey L, Pimenta JM, Poole C, Jenkins D, Smith JS. Persistent human papillomavirus infection and cervical neoplasia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;168:123–137. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Woodman CBJ, Collins S, Winter H, Bailey A, Ellis J, Prior P, Yates M, Rollason TP, Young LS. Natural history of cervical human papillomavirus infection in young women: a longitudinal cohort study. Lancet. 2001;357:1831–1836. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04956-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Walboomers JM, Jacobs MV, Manos MM, Bosch FX, Kummer JA, Shah KV, Snijders PJ, Peto J, Meijer CJ, Muñoz N. Human papillomavirus is a necessary cause of invasive cervical cancer worldwide. J Pathol. 1999;189:12–19. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199909)189:1<12::AID-PATH431>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hildesheim A, Schiffman MH, Gravitt PE, Glass AG, Greer CE, Zhang T, Scott DR, Rush BB, Lawler P, Sherman ME, Kurman RJ, Manos MM. Persistence of type-specific human papillomavirus infection among cytologically normal women. J Infect Dis. 1994;169:235–240. doi: 10.1093/infdis/169.2.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Appleby P, Beral V, de Berrington González A, Colin D, Franceschi S, Goodill A, Green J, Peto J, Plummer M, Sweetland S. Carcinoma of the cervix and tobacco smoking: collaborative reanalysis of individual data on 13,541 women with carcinoma of the cervix and 23,017 women without carcinoma of the cervix from 23 epidemiological studies. Int J Cancer. 2006;118:1481–1495. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Comparison of risk factors for invasive squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma of the cervix: collaborative reanalysis of individual data on 8,097 women with squamous cell carcinoma and 1,374 women with adenocarcinoma from 12 epidemiological studies. Int J Cancer. 2006, 120: 885-891. 10.1002/ijc.22357. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Cervical carcinoma and sexual behavior: collaborative reanalysis of individual data on 15,461 women with cervical carcinoma and 29,164 women without cervical carcinoma from 21 epidemiological studies. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009, 18: 1060-1069. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-1186. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Smith JS, Muñoz N, Herrero R, Eluf-Neto J, Ngelangel C, Franceschi S, Bosch FX, Walboomers JM, Peeling RW. Evidence for Chlamydia trachomatisas a human papillomavirus cofactor in the etiology of invasive cervical cancer in Brazil and the Philippines. J Infect Dis. 2002;185:324–331. doi: 10.1086/338569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Silins I, Ryd W, Strand A, Wadell G, Törnberg S, Hansson BG, Wang X, Arnheim L, Dahl V, Bremell D, Persson K, Dillner J, Rylander E. Chlamydia trachomatis infection and persistence of human papillomavirus. Int J Cancer. 2005;116:110–115. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wallin KL, Wiklund F, Luostarinen T, Angström T, Anttila T, Bergman F, Hallmans G, Ikäheimo I, Koskela P, Lehtinen M, Stendahl U, Paavonen J, Dillner J. A population-based prospective study of Chlamydia trachomatis infection and cervical carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2002;101:371–374. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown DR, Shew ML, Qadadri B, Neptune N, Vargas M, Tu W, Juliar BE, Breen TE, Fortenberry JD. A longitudinal study of genital human papillomavirus infection in a cohort of closely followed adolescent women. J Infect Dis. 2005;191:182–192. doi: 10.1086/426867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Winer RL, Lee SK, Hughes JP, Adam DE, Kiviat NB, Koutsky LA. Genital human papillomavirus infection: incidence and risk factors in a cohort of female university students. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157:218–226. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Collins S, Mazloomzadeh S, Winter H, Blomfield P, Bailey A, Young LS, Woodman CB. High incidence of cervical human papillomavirus infection in women during their first sexual relationship. BJOG. 2002;109:96–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2002.01053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kjaer SK, Chackerian B, van den Brule AJ, Svare EI, Paull G, Walbomers JM, Schiller JT, Bock JE, Sherman ME, Lowy DR, Meijer CL. High-risk human papillomavirus is sexually transmitted: evidence from a follow-up study of virgins starting sexual activity (intercourse) Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2001;10:101–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rodriguez AC, Burk R, Herrero R, Hildesheim A, Bratti C, Sherman ME, Solomon D, Guillen D, Alfaro M, Viscidi R, Morales J, Hutchinson M, Wacholder S, Schiffman M. The natural history of human papillomavirus infection and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia among young women in the Guanacaste cohort shortly after initiation of sexual life. Sex Transm Dis. 2007;34:494–502. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000251241.03088.a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jaisamrarn U, Castellsagué X, Garland SM, Naud P, Palmroth J, Del Rosario-Raymundo MR, Wheeler CM, Salmerón J, Chow S-N, Apter D, Teixeira JC, Skinner SR, Hedrick J, Szarewski A, Romanowski B, Aoki FY, Schwarz TF, Poppe WAJ, Bosch FX, de Carvalho NS, Germar MJ, Peters K, Paavonen J, Bozonnat M-C, Descamps D, Struyf F, Dubin GO, Rosillon D, Baril L, for the HPV PATRICIA Study Group: Natural history of progression of HPV infection to cervical lesion or clearance: analysis of the control arm of the large, randomised PATRICIA study. PLoS One 2013, doi:10.1371/annotation/cea59317-929c-464a-b3f7-e095248f229a., [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Paavonen J, Jenkins D, Bosch FX, Naud P, Salmerón J, Wheeler CM, Chow SN, Apter DL, Kitchener HC, Castellsague X, de Carvalho NS, Skinner SR, Harper DM, Hedrick JA, Jaisamrarn U, Limson GA, Dionne M, Quint W, Spiessens B, Peeters P, Struyf F, Wieting SL, Lehtinen MO, Dubin G. Efficacy of a prophylactic adjuvanted bivalent L1 virus-like-particle vaccine against infection with human papillomavirus types 16 and 18 in young women: an interim analysis of a phase III double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2007;369:2161–2170. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60946-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paavonen J, Naud P, Salmerón J, Wheeler CM, Chow SN, Apter D, Kitchener H, Castellsague X, Teixeira JC, Skinner SR, Hedrick J, Jaisamrarn U, Limson G, Garland S, Szarewski A, Romanowski B, Aoki FY, Schwarz TF, Poppe WA, Bosch FX, Jenkins D, Hardt K, Zahaf T, Descamps D, Struyf F, Lehtinen M, Dubin G. Efficacy of human papillomavirus (HPV)-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine against cervical infection and precancer caused by oncogenic HPV types (PATRICIA): final analysis of a double-blind, randomised study in young women. Lancet. 2009;374:301–314. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61248-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lehtinen M, Apter D, Dubin G, Kosunen E, Isaksson R, Korpivaara EL, Kyhä-Osterlund L, Lunnas T, Luostarinen T, Niemi L, Palmroth J, Petäjä T, Rekonen S, Salmivesi S, Siitari-Mattila M, Svartsjö S, Tuomivaara L, Vilkki M, Pukkala E, Paavonen J. Enrolment of 22,000 adolescent women to cancer registry follow-up for long-term human papillomavirus vaccine efficacy: guarding against guessing. Int J STD AIDS. 2006;17:517–521. doi: 10.1258/095646206778145550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van Doorn L-J, Molijn A, Kleter B, Quint W, Colau B. Highly effective detection of human papillomavirus 16 and 18 DNA by a testing algorithm combining broad-spectrum and type-specific PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:3292–3298. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00539-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roset Bahmanyar E, Paavonen J, Naud P, Salmerón J, Chow SN, Apter D, Kitchener H, Castellsagué X, Teixeira JC, Skinner SR, Jaisamrarn U, Limson GA, Garland SM, Szarewski A, Romanowski B, Aoki F, Schwarz TF, Poppe WA, De Carvalho NS, Harper DM, Bosch FX, Raillard A, Descamps D, Struyf F, Lehtinen M, Dubin G. Prevalence and risk factors for cervical HPV infection and abnormalities in young adult women enrolled in the multinational PATRICIA trial. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;127:440–450. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2012.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bruni L, Diaz M, Castellsagué X, Ferrer E, Bosch FX, de Sanjosé S. Cervical human papillomavirus prevalence in 5 continents: meta-analysis of 1 million women with normal cytological findings. J Infect Dis. 2010;202:1789–1799. doi: 10.1086/657321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bosch FX, Burchell AN, Schiffman M, Giuliano AR, de Sanjose S, Bruni L, Tortolero-Luna G, Kjaer SK, Muñoz N. Epidemiology and natural history of human papillomavirus infections and type-specific implications in cervical neoplasia. Vaccine. 2008;26(Suppl 10):K1–K16. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.05.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wheeler CM, Hunt WC, Schiffman M, Castle PE. Human papillomavirus genotypes and the cumulative risk of cervical precancer. J Infect Dis. 2006;194:1291–1299. doi: 10.1086/507909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liaw KL, Hildesheim A, Burk RD, Gravitt P, Wacholder S, Manos MM, Scott DR, Sherman ME, Kurman RJ, Glass AG, Anderson SM, Schiffman M. A prospective study of human papillomavirus (HPV) type 16 DNA detection by polymerase chain reaction and its association with acquisition and persistence of other HPV types. J Infect Dis. 2001;183:8–15. doi: 10.1086/317638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mendez F, Munoz N, Posso H, Molano M, Moreno V, van den Brule AJ, Ronderos M, Meijer C, Munoz A. Cervical coinfection with human papillomavirus (HPV) types and possible implications for the prevention of cervical cancer by HPV vaccines. J Infect Dis. 2005;192:1158–1165. doi: 10.1086/444391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rousseau MC, Pereira JS, Prado JC, Villa LL, Rohan TE, Franco EL. Cervical coinfection with human papillomavirus (HPV) types as a predictor of acquisition and persistence of HPV infection. J Infect Dis. 2001;184:1508–1517. doi: 10.1086/324579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: List of Independent Ethics Committees/ Institutional Review Boards. (DOC 572 KB)