Abstract

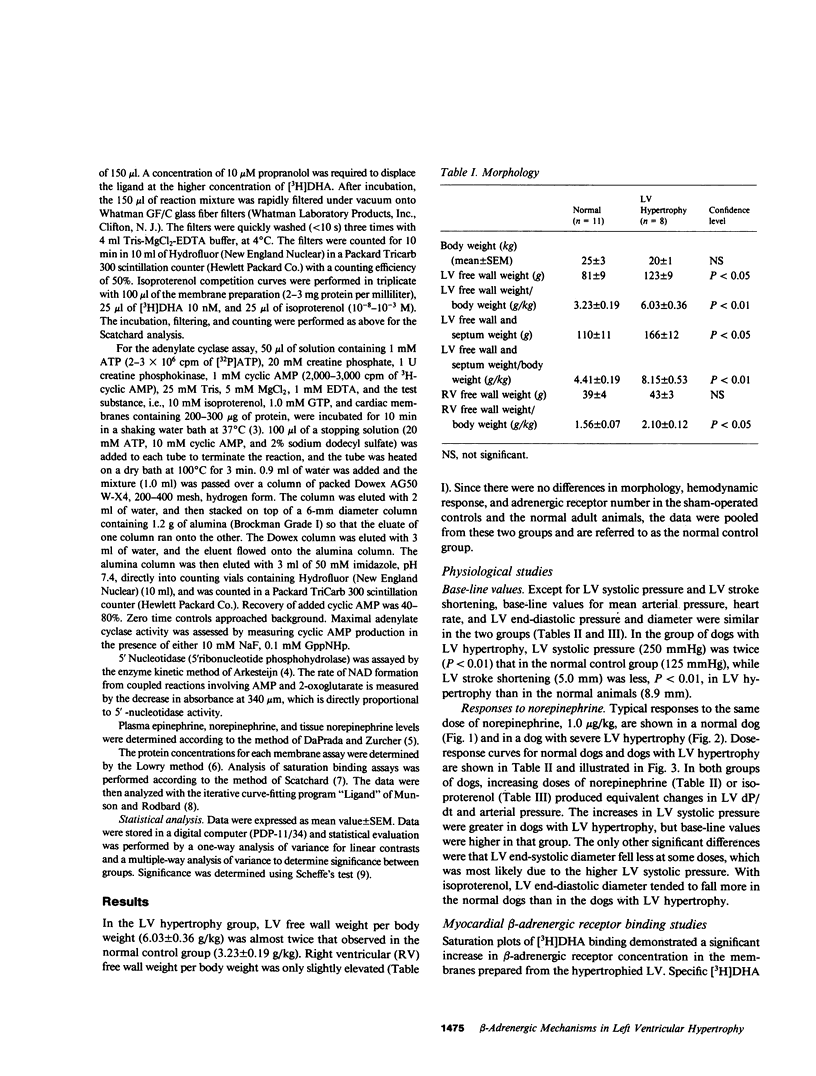

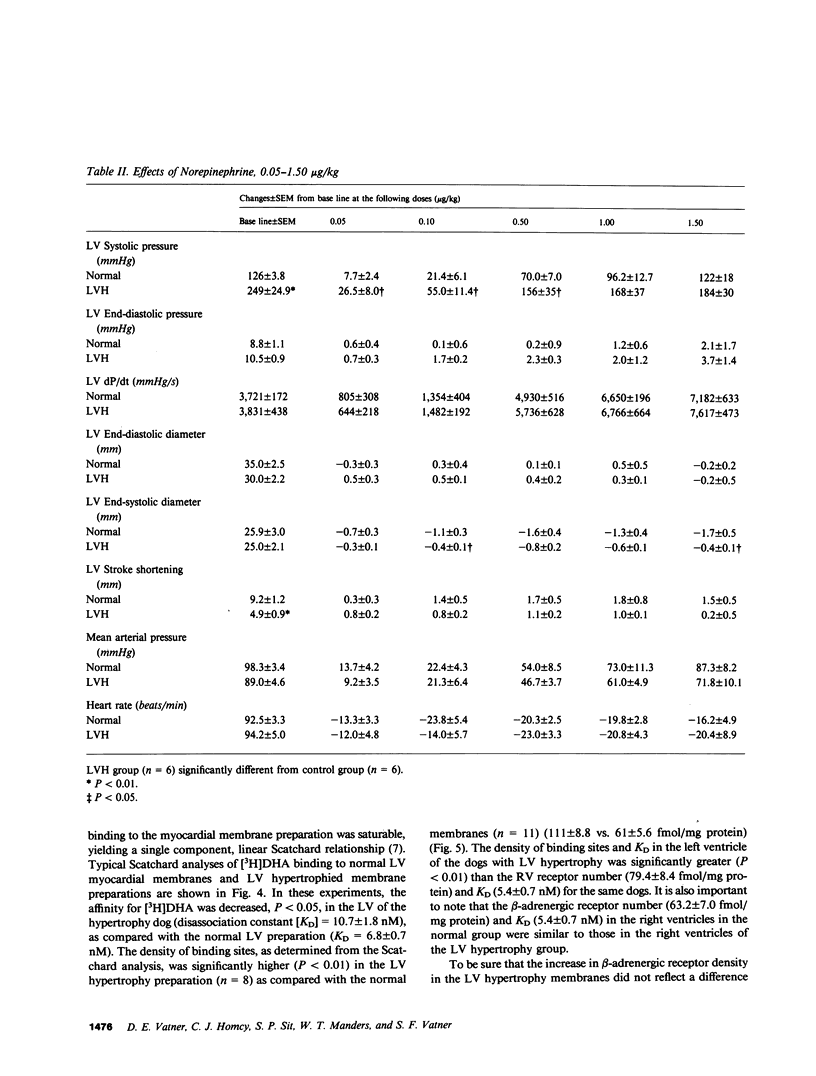

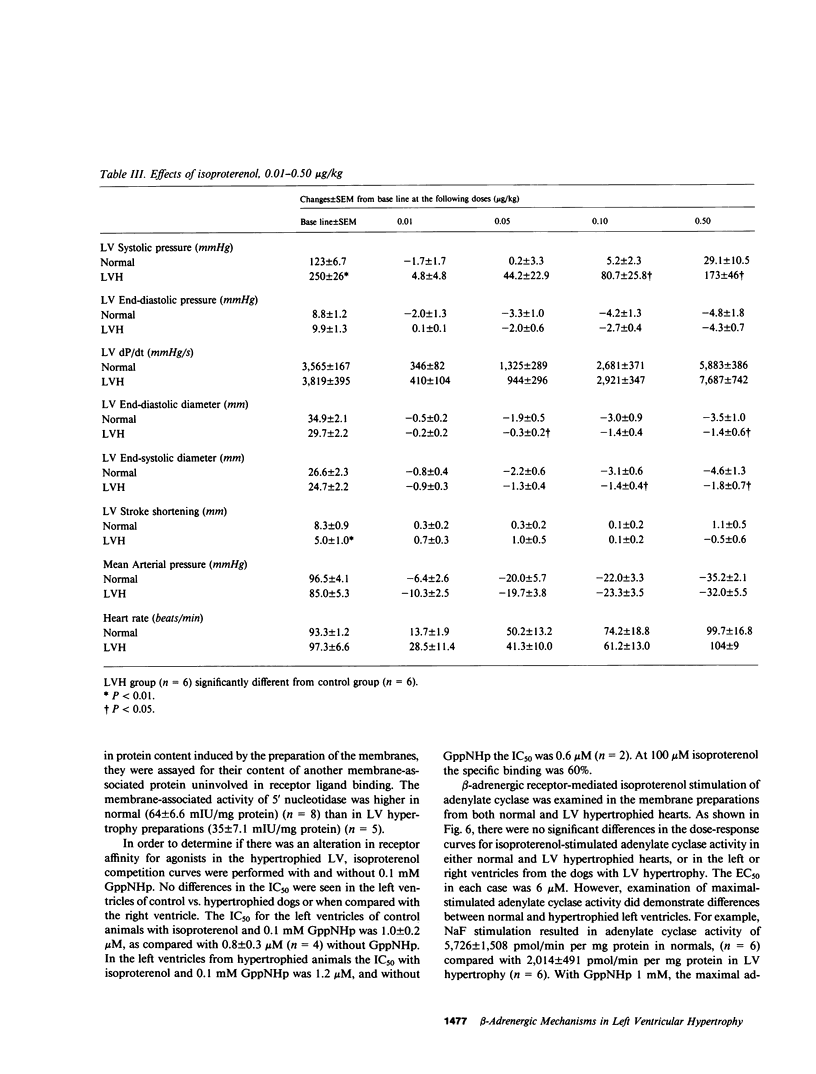

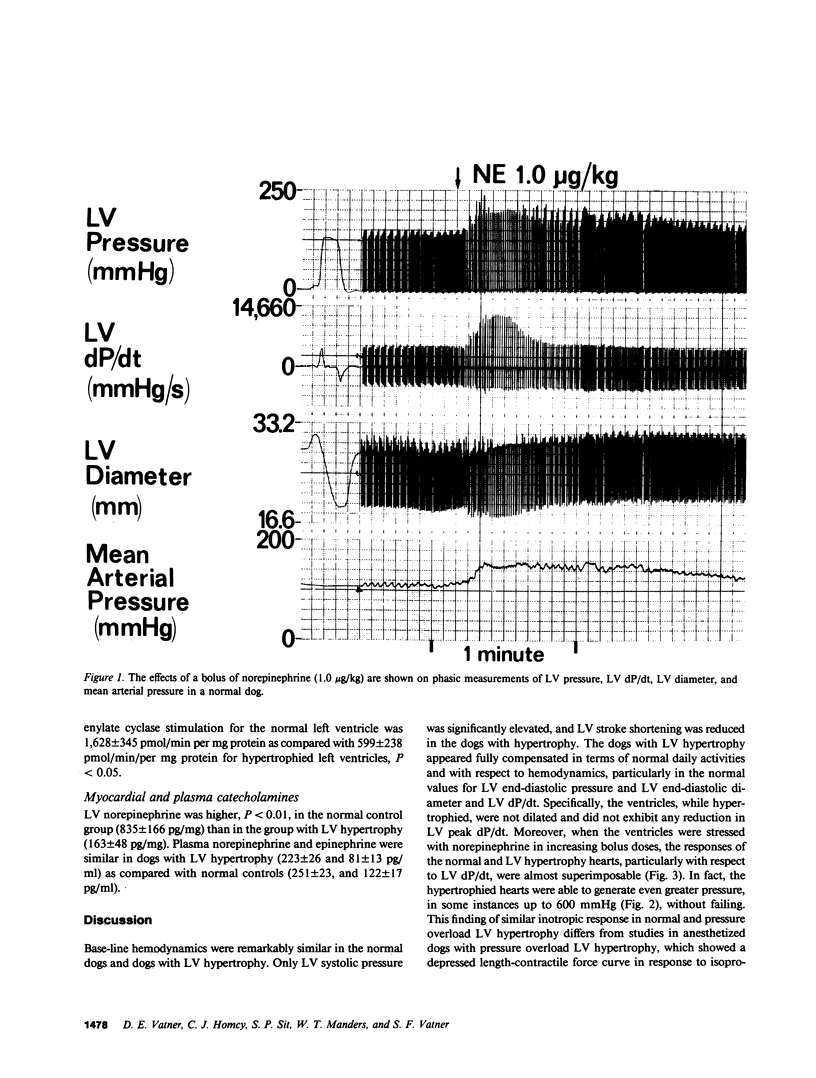

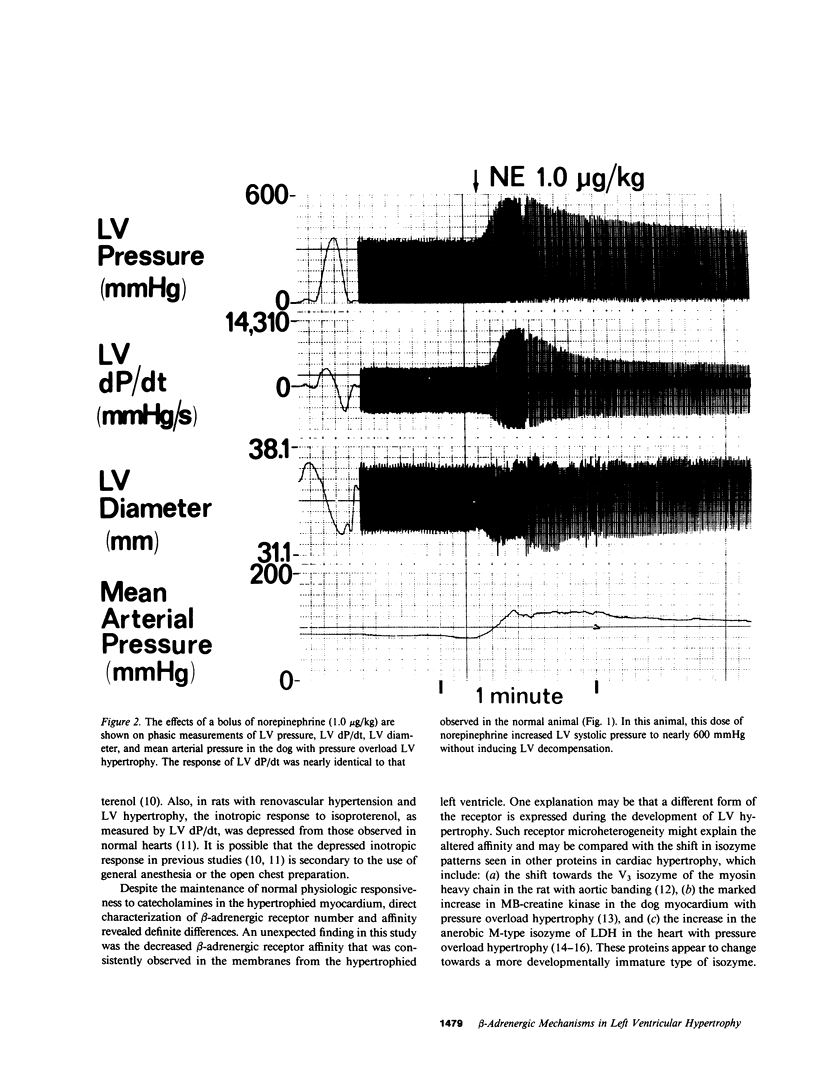

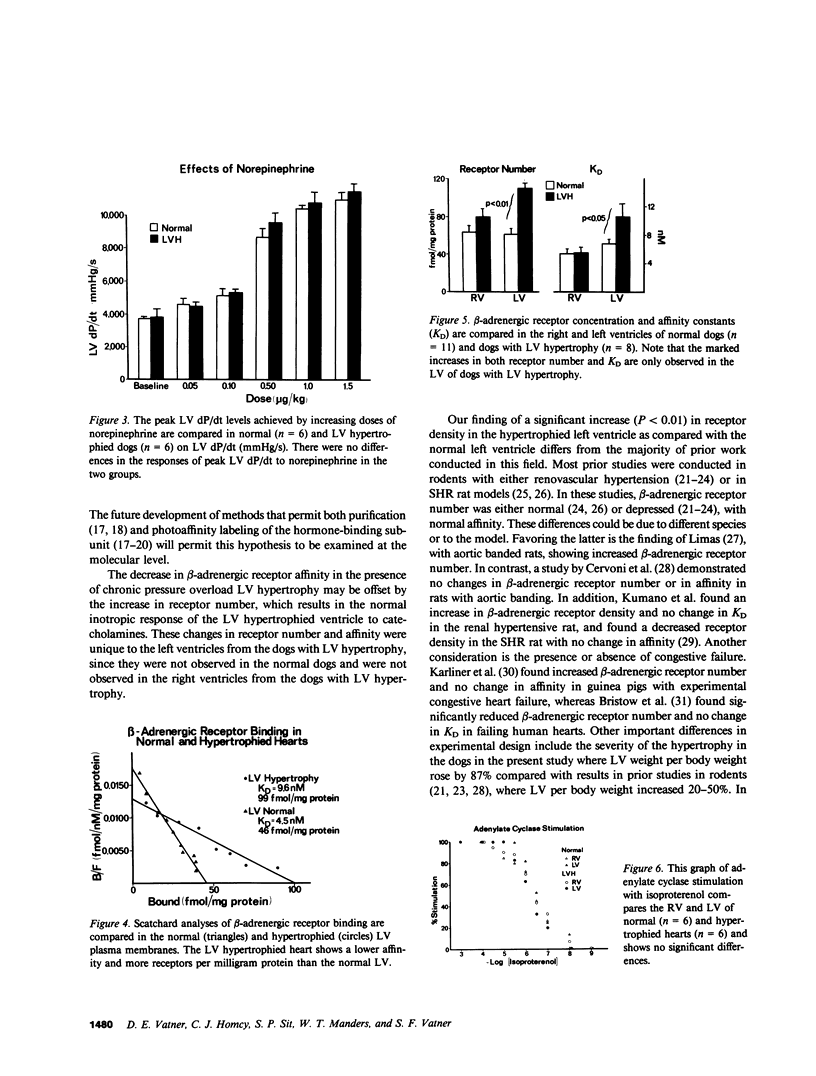

Pressure overload left ventricular (LV) hypertrophy was produced by banding the ascending aorta of puppies and allowing them to grow to adulthood. LV free wall weight per body weight increased by 87% from a normal value of 3.23 +/- 0.19 g/kg. Hemodynamic studies of conscious dogs with LV hypertrophy and of normal, conscious dogs without LV hypertrophy showed similar base-line values for mean arterial pressure, heart rate, and LV end-diastolic pressure and diameter. LV systolic pressure was significantly greater, P less than 0.01, and LV stroke shortening was significantly lss, P less than 0.01, in the LV hypertrophy group. In both normal and LV hypertrophy groups, increasing bolus doses of norepinephrine or isoproterenol produced equivalent changes in LV dP/dt. beta-adrenergic receptor binding studies with [3H]-dihydroalprenolol ( [3H]DHA) indicated that the density of binding sites was significantly elevated, P less than 0.01, in the hypertrophied LV plasma membranes (111 +/- 8.8, n = 8), as compared with normal LV (61 +/- 5.6 fmol/mg protein, n = 11). The receptor affinity decreased, i.e., disassociation constant (KD) increased, selectively in the LV of the hypertrophy group; the KD in the normal LV was 6.8 +/- 0.7 nM compared with 10.7 +/- 1.8 nM in the hypertrophied LV. These effects were observed only in the LV of the LV hypertrophy group and not in the right ventricles from the same dogs. The plasma membrane marker, 5' -nucleotidase activity, was slightly lower per milligram protein in the LV hypertrophy group, indicating that the differences in beta-adrenergic receptor binding and affinity were not due to an increase in plasma membrane protein in the LV hypertrophy group. The EC50 for isoproterenol-stimulated adenylate cyclase activity was similar in both the right and left ventricles and in the two groups. However, maximal-stimulated adenylate cyclase was lower in the hypertrophied left ventricle. Plasma catecholamines were similar in the normal and hypertrophied groups, but myocardial norepinephrine was depressed in the dogs with LV hypertrophy (163 +/- 48 pg/mg) compared with normal dogs (835 +/- 166 pg/mg). Thus, severe, but compensated LV hypertrophy, induced by aortic banding in puppies, is characterized by essentially normal hemodynamics in adult dogs studied at rest and in response to catecholamines in the conscious state. At the cellular level, reduced affinity and increased beta-adrenergic receptor number characterized the LV hypertrophy group, while the EC50 for isoproterenol-stimulated adenylate cyclase activity was normal. By these mechanisms, adequate responsiveness to catecholamines is retained in conscious dogs with severe LV hypertrophy.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Arkesteijn C. L. A kinetic method for serum 5'-nucleotidase using stabilised glutamate dehydrogenase. J Clin Chem Clin Biochem. 1976 Mar;14(3):155–158. doi: 10.1515/cclm.1976.14.1-12.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop S. P., Altschuld R. A. Increased glycolytic metabolism in cardiac hypertrophy and congestive failure. Am J Physiol. 1970 Jan;218(1):153–159. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1970.218.1.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobik A., Korner P. Cardiac beta adrenoceptors and adenylate cyclase in normotensive and renal hypertensive rabbits during changes in autonomic activity. Clin Exp Hypertens. 1981;3(2):257–280. doi: 10.3109/10641968109033664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bristow M. R., Ginsburg R., Minobe W., Cubicciotti R. S., Sageman W. S., Lurie K., Billingham M. E., Harrison D. C., Stinson E. B. Decreased catecholamine sensitivity and beta-adrenergic-receptor density in failing human hearts. N Engl J Med. 1982 Jul 22;307(4):205–211. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198207223070401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cervoni P., Herzlinger H., Lai F. M., Tanikella T. A comparison of cardiac reactivity and beta-adrenoceptor number and affinity between aorta-coarcted hypertensive and normotensive rats. Br J Pharmacol. 1981 Nov;74(3):517–523. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1981.tb10459.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Da Prada M., Zürcher Simultaneous radioenzymatic determination of plasma and tissue adrenaline, noradrenaline and dopamine within the femtomole range. Life Sci. 1976 Oct 15;19(8):1161–1174. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(76)90251-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox A. C., Reed G. E. Changes in lactate dehydrogenase composition of hearts with right ventricular hypertrophy. Am J Physiol. 1969 May;216(5):1026–1033. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1969.216.5.1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giachetti A., Clark T. L., Berti F. Subsensitivity of cardiac beta-adrenoceptors in renal hypertensive rats. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1979 Jul-Aug;1(4):467–471. doi: 10.1097/00005344-197907000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homcy C. J., Rockson S. G., Countaway J., Egan D. A. Purification and characterization of the mammalian beta 2-adrenergic receptor. Biochemistry. 1983 Feb 1;22(3):660–668. doi: 10.1021/bi00272a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homcy C. J., Wrenn S. M., Haber E. Demonstration of the hydrophilic character of adenylate cyclase following hydrophobic resolution on immobilized alkyl residues. Critical role of alkyl chain length. J Biol Chem. 1977 Dec 25;252(24):8957–8964. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karliner J. S., Barnes P., Brown M., Dollery C. Chronic heart failure in the guinea pig increases cardiac alpha 1- and beta-adrenoceptors. Eur J Pharmacol. 1980 Oct 3;67(1):115–118. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(80)90017-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LOWRY O. H., ROSEBROUGH N. J., FARR A. L., RANDALL R. J. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951 Nov;193(1):265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavin T. N., Nambi P., Heald S. L., Jeffs P. W., Lefkowitz R. J., Caron M. G. 125I-labeled p-azidobenzylcarazolol, a photoaffinity label for the beta-adrenergic receptor. Characterization of the ligand and photoaffinity labeling of beta 1- and beta 2-adrenergic receptors. J Biol Chem. 1982 Oct 25;257(20):12332–12340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limas C. J. Increased number of beta-adrenergic receptors in the hypertrophied myocardium. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1979 Nov 15;588(1):174–178. doi: 10.1016/0304-4165(79)90382-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limas C., Limas C. J. Reduced number of beta-adrenergic receptors in the myocardium of spontaneously hypertensive rats. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1978 Jul 28;83(2):710–714. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(78)91047-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lompre A. M., Schwartz K., d'Albis A., Lacombe G., Van Thiem N., Swynghedauw B. Myosin isoenzyme redistribution in chronic heart overload. Nature. 1979 Nov 1;282(5734):105–107. doi: 10.1038/282105a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee A., Graham R. M., Sagalowsky A. I., Pettinger W., McCoy K. E. Myocardial beta-adrenergic receptors in the stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rat. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1980 Nov;12(11):1263–1272. doi: 10.1016/0022-2828(80)90070-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munson P. J., Rodbard D. Ligand: a versatile computerized approach for characterization of ligand-binding systems. Anal Biochem. 1980 Sep 1;107(1):220–239. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(80)90515-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman W. H., Webb J. G. Adaptation of left ventricle to chronic pressure overload: response to inotropic drugs. Am J Physiol. 1980 Feb;238(2):H134–H143. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1980.238.2.H134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagani M., Baig H., Sherman A., Manders W. T., Quinn P., Patrick T., Franklin D., Vatner S. F. Measurement of multiple simultaneous small dimensions and study of arterial pressure-dimension relations in conscious animals. Am J Physiol. 1978 Nov;235(5):H610–H617. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1978.235.5.H610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick T. A., Vatner S. F., Kemper W. S., Franklin D. Telemetry of left ventricular diameter and pressure measurements from unrestrained animals. J Appl Physiol. 1974 Aug;37(2):276–281. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1974.37.2.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rashidbaigi A., Ruoho A. E. Iodoazidobenzylpindolol, a photoaffinity probe for the beta-adrenergic receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1981 Mar;78(3):1609–1613. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.3.1609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saragoça M. A., Tarazi R. C. Left ventricular hypertrophy in rats with renovascular hypertension. Alterations in cardiac function and adrenergic responses. Hypertension. 1981 Nov-Dec;3(6 Pt 2):II–171-6. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.3.6_pt_2.ii-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shorr R. G., Strohsacker M. W., Lavin T. N., Lefkowitz R. J., Caron M. G. The beta 1-adrenergic receptor of the turkey erythrocyte. Molecular heterogeneity revealed by purification and photoaffinity labeling. J Biol Chem. 1982 Oct 25;257(20):12341–12350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobel B. E., Henry P. D., Ehrlich B. J., Bloor C. M. Altered myocardial lactic dehydrogenase isoenzymes in experimental cardiac hypertrophy. Lab Invest. 1970 Jan;22(1):23–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spann J. F., Jr, Chidsey C. A., Pool P. E., Braunwald E. Mechanism of norepinephrine depletion in experimental heart failure produced by aortic constriction in the guinea pig. Circ Res. 1965 Oct;17(4):312–321. doi: 10.1161/01.res.17.4.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodcock E. A., Johnston C. I. Changes in tissue alpha- and beta-adrenergic receptors in renal hypertension in the rat. Hypertension. 1980 Mar-Apr;2(2):156–161. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.2.2.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]