Abstract

Background

Rates of suicide attempts and non-suicidal self-injury ([NSSI]; e.g., cutting, burning) peak in adolescence and early adulthood; females and individuals with psychiatric symptoms and diagnoses appear to be at particular risk. Hinshaw and colleagues (2012) reported that young women with histories of childhood ADHD diagnoses reported higher rates of suicide attempts and NSSI than non-diagnosed, comparison women.

Methods

Via analyses of an ongoing longitudinal investigation, our aims are to examine, with respect to both aspects of self-harmful behavior, (a) ADHD subtype differences and effects of diagnostic persistence (versus transient and non-diagnosed classifications) and (b) potential mediating effects of impulsivity and comorbid psychopathology, ascertained during adolescence.

Results

Young adult women with a childhood diagnosis of ADHD-Combined type were at highest risk for suicide attempts as well as the most varied and severe forms of NSSI compared to those with ADHD-Inattentive type and those in the comparison group; participants with a persistent ADHD diagnosis were at higher risk than those with a transient diagnosis or those never meeting criteria for ADHD. Mediator analyses revealed that, during adolescence, an objective measure of impulsivity plus comorbid externalizing symptoms were simultaneous, partial mediators of the childhood ADHD-young adult NSSI linkage. Adolescent internalizing symptoms emerged as a partial mediator of the childhood ADHD-young adult suicide attempt linkage.

Conclusions

ADHD in females, especially when featuring childhood impulsivity and especially with persistent symptomatology, carries high risk for self-harm. Psychiatric comorbidity and response inhibition are important mediators of this clinically important longitudinal association. We discuss limitations and implications for prevention and intervention.

Keywords: attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, self-harm, self-injury, adulthood, comorbidity

Prospective research has revealed impairments for boys with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) that persist into adolescence and adulthood (e.g., Barkley, Murphy, & Fischer, 2008; Klein et al., 2012). Yet far less is known about adolescent and adult outcomes among girls. Accumulating evidence reveals that they are also at increased risk for persistent ADHD symptoms, comorbidities, and major life impairments (Babinski et al., 2011; Biederman et al., 2010; Hinshaw, Owens, Sami, & Fargeon, 2006; Hinshaw et al., 2012; Mannuzza, & Klein, 2000). Yet there is surprisingly little research on the association between ADHD and self-harmful actions, defined as behaviors that reflect (a) an attempt to die (i.e., suicide attempts) or (b) a deliberate and direct destruction of one's body tissue without reported suicidal intent (i.e., non-suicidal self-injury [NSSI]). Self-harmful behaviors are a significant public-health concern (Nock, 2012). We focus on (a) careful analysis of the prospective, longitudinal links of childhood ADHD with young-adult suicidal behavior and NSSI and (b) potential childhood risk factors and adolescent mediators of this association, including impulsivity, comorbidity, and diagnostic persistence of ADHD over time.

Rates of suicide attempts in adolescence and early adulthood are distressingly high. Suicide is the third leading cause of death among 15-24 year-olds and the second highest among college students (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2006). In a key synthesis of worldwide age trends in self-harm, Nock and colleagues (2008) found escalating rates of suicide attempts through the age range of the 20's. In terms of NSSI, rates in community (15%-25%; Ross & Heath, 2002) and clinically referred samples (21%-61%; Darche, 1990) are distressingly high. Both suicide attempts and NSSI are heterogeneous and overdetermined (Prinstein, 2008). The developmental stage of adolescence, preceded by the biological changes related to puberty, represents a particularly vulnerable period, marked by high levels of emotional distress, increased risk-taking behaviors, and heightened interpersonal stress (Brausch & Gutierrez, 2010; Goldston et al., 2009; Lloyd-Richardson, 2008; Nock, 2009). During this period, changes in sensation seeking and impulse-control problems are distinguishable from those related to mood and distress (see Dahl, 2004). Risk is particularly high for individuals with increased emotionality and decreased inhibitions related to psychiatric diagnoses (e.g., mood and impulse-control problems, alcohol/substance use, and multiple concurrent psychiatric diagnoses). Adolescence and early adulthood are an exceptionally vulnerable time period for girls and young women (Guerry & Prinstein, 2010; Ross & Heath, 2002).

Prinstein (2008) defined NSSI as self-harmful behaviors that are widely considered to be socially unacceptable (as opposed to piercing and tattooing) and lacking suicidal intent, whereas suicide attempts involve an explicit desire to die. Yet ambivalence may be normative regarding such intentions (Rodham, Hawton, & Evans, 2004). Indeed, NSSI and suicide attempts often co-occur, either concurrently or sequentially: 50-75% of adolescents with a history of NSSI make a suicide attempt at some point (Joiner, 2005; Nock, Joiner, Gordon, Lloyd-Richardson, & Prinstein, 2006). Still, compared to adolescents engaging in NSSI alone, those engaging in NSSI with at least one suicide attempt (a) report a longer history of NSSI, (b) use more varied methods of NSSI, (c) have less perceived parental support and lower self-esteem, and (d) are likely to meet criteria for major depression and/or conduct disorder (see Brausch & Gutierrez, 2010).

There are three key reasons to believe that young adults with histories of ADHD may be at particularly high risk for NSSI and suicide attempts. First, impulsivity—a cardinal symptom of ADHD—is a common risk factor for and correlate of suicidal behavior and NSSI (Gvion & Apter, 2011). Impulsivity is a definitional criterion for the Combined type of ADHD, or ADHD-C (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). Salient aspects of impulsivity include increased urgency (e.g., tendency to act impulsively when experiencing negative affect) and lack of premeditation (e.g., failure to reflect on consequences of an act before engaging in that act; see Miller, Derefinko, Lynam, Milich, & Fillmore, 2010). Second, individuals with ADHD demonstrate poor performance on laboratory inhibitory control tasks (Hinshaw, Carte, Sami, Treuting, & Zupan, 2002; Lijffijt, Kenemans, Verbaten, & van Engeland, 2005; O'Brien, Dowell, Mostofsky, Denckla, & Mahone, 2010). Third, the impulsivity characterizing ADHD contributes to pathological eating behaviors (Mikami & Hinshaw, 2008), antisocial behavior (Colledge & Blair, 2001; Mathias et al., 2007), alcohol consumption (Weafer, Milich & Fillmore, 2011), and low social competence (Miller & Hinshaw, 2010). Thus, deficits in this area may render an adolescent—particularly one with ADHD—vulnerable to self-harmful behaviors through both direct and indirect (e.g., comorbidity; social rejection) pathways.

Regarding comorbidity, internalizing problems (e.g., depression, anxiety) are concurrently and prospectively associated with both suicide attempts and NSSI (e.g., Brausch & Gutierrez, 2010; Goldston et al., 2009; Gould et al., 1998; Guerry & Prinstein, 2010; Hilt, Cha, & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2008). Beginning in adolescence, girls are at particular risk for internalizing problems (Hankin et al., 1998; Twenge & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2002). Yet the combination of an externalizing disorder, such as conduct disorder, and an internalizing disorder, such as major depression, is uniquely associated with suicide attempts and NSSI, beyond other individual and comorbid diagnostic profiles (Goldston et al., 2009; Kovacs, Goldston & Gatsonis, 1993). Nock et al. (2006) found that more than half of an inpatient sample of adolescents with a recent history of NSSI met criteria for both an internalizing and an externalizing disorder. Girls with ADHD are far more likely than non-diagnosed peers to maintain or develop internalizing and/or externalizing disorders in adolescence (Biederman et al., 2008; Biederman et al., 2010; Hinshaw et al., 2006; Hinshaw et al., 2012), amplifying the risk for suicide attempts and NSSI in this population.

In terms of suicide attempts, Barkley et al. (2008) found that severity of childhood hyperactivity and number of CD symptoms in adolescence emerged as marginally significant mediators of suicide attempts among young adults with ADHD. In a longitudinal study of a predominantly male sample, children with ADHD-C or ADHD-HI (predominately hyperactive-impulsive subtype), but not ADHD-I (predominantly inattentive subtype), were at greater risk for adolescent suicide attempts than a comparison sample (Chronis-Tuscano et al., 2010). Crucially, girls with childhood-diagnosed ADHD (n = 18) were at far greater risk for depression and suicide attempts than boys. A key follow-up paper reported that the relation between ADHD and suicidal behavior was mediated by poor emotion regulation (Seymour, Chronis-Tuscano, Halldorsdottir, Stupica, Owens, & Sacks, 2012). Replication of these findings is needed in larger samples.

Hinshaw et al. (2012) presented findings from a prospective follow-up of girls with and without ADHD. Young women with a childhood diagnosis had higher rates of psychiatric symptoms and functional impairments by early adulthood than the comparison group, despite stringent control of age, IQ, demographics, comorbidities, medication status and despite desistance from formal ADHD in many instances. Crucially, those with a childhood diagnosis of ADHD-C had significantly higher reports of NSSI frequency and suicide attempts than those with ADHD-I or comparisons.

We aim to pursue these clinically and conceptually significant findings in greater depth. First, because impulsivity is particularly relevant for ADHD-Combined type, we hypothesize that salient aspects of impulsivity, such as increased urgency, lack of premeditation, and poor inhibitory control, may render girls with ADHD-C more likely to indiscriminately use any easily available means of self-harm. Therefore, we predict that young women with childhood-diagnosed ADHD-C will have the most varied and severe forms of NSSI, followed by participants with ADHD-I and the comparison group, respectively. Second, compared to those with a transient ADHD diagnosis and individuals never meeting criteria for ADHD, young women with persistent ADHD will show the highest risk for suicide attempts and all aspects of NSSI. Third, the prospective, longitudinal nature of this investigation affords examination of pathways between childhood ADHD diagnosis (Wave 1), candidate mediators in adolescence (Wave 2), and NSSI severity and suicide attempts in young adulthood (Wave 3). We examine three individual candidate mediators (impulsivity, internalizing comorbidity, and externalizing comorbidity) and build more complex models in instances with two or more significant mediators.

Method

Participants

The initial recruitment process, featuring girls referred from schools, pediatricians, and clinics as well as via direct advertisements, involved a multi-gated screening and diagnostic procedure to ascertain participants, aged 6-12 years (M = 9.1 years), comprising a carefully diagnosed ADHD group and a comparison sample matched on age and ethnicity. The final sample included 140 girls with ADHD (ADHD-C = 93, ADHD-I = 47) and 88 comparison girls (see Hinshaw, 2002, for details).

Final inclusion criteria for the clinical group required participants to meet full DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for ADHD via the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (4th ed., DISC-IV; Shaffer, Fisher, Lucas, Dulcan, & Schwab-Stone, 2000). Common comorbidities were permitted (e.g., major depressive disorder [MDD], anxiety disorders, learning disorders, oppositional defiant disorder [ODD], and conduct disorder [CD]). Comparison girls could not meet diagnostic criteria for ADHD. Exclusion criteria for all participants were psychosis or overt neurological disorder, mental retardation, pervasive developmental disorder, lack of English spoken at home, or any medical problems that prevented participation in the summer camp. All girls participated in research summer programs.

The sample represented diverse socioeconomic and ethnic backgrounds (53% White, 27% African- American, 11% Latina, 9% Asian-American). The average family income was $50,000 to $60,000, with 13.6% receiving public assistance. On average, mothers had completed “some college.” There were no ADHD versus comparison group differences for any demographic variables. Participants were then invited for a 5-year follow-up (Wave 2; M age = 14.2 years; 92% retention) and a 10-year follow-up (Wave 3; M age = 19.6 years; 95% retention). Details are found in Hinshaw et al. (2006) and Hinshaw et al. (2012). At each wave, girls and parents completed informed consent and/or assent procedures prior to participation. All waves of data collection received full approval from the UC Berkeley Committee for Protection of Human Subjects.

Measures

At each wave, highly trained bachelor-level research assistants and doctoral students performed assessments. Staff members changed at each wave of data collection; staff members during Wave 2 and Wave 3 were not informed of participants' Wave 1 diagnostic status.

Independent Variable: Childhood (Wave 1) ADHD Diagnosis

The DISC-IV is a well-validated, highly structured diagnostic interview. At Wave 1, on the parent-completed version, girls in the clinical group met full criteria for either ADHD-C or ADHD-I.

Independent Variable: Persistence or Remission of ADHD Diagnosis

We created a dummy variable to reflect remission or persistence of ADHD diagnosis from Wave 1 to Wave 3. Wave 1 diagnosis was established via the guidelines described above; at Wave 3, we used both parent and youth report from the DISC-IV to establish the presence of ADHD via the “or” criterion, symptom by symptom (Piacentini, Cohen, & Cohen, 1992). Young women who did not meet ADHD criteria at Wave 1 or Wave 3 were coded as 0; those who met ADHD criteria at Wave 1 or Wave 3 were coded as 1 (transient ADHD); and those who met ADHD criteria at Wave 1 and Wave 3 were coded as 2 (persistent ADHD).

Wave 3 Criterion Variables

Nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI)

We administered the Self-Injury Questionnaire (SIQ), an interviewer-administered measure based on a modification of Claes, Vandereycken, and Vertommen's (2001) SIQ. Validity and reliability within samples of individuals with eating disorders are available (Vanderlinden & Vendereycken, 1997). Participants were asked whether, in the past year, they deliberately injured themselves using six different methods. When a behavior was endorsed, respondents were also asked about frequency (1 = only once; 6 = a couple times a day). We analyzed three scores: (1) variety (0-6), based on the number of methods tried; (2) frequency, an average frequency score across the 6 items; and (3) severity (0-3), informed by a lethality continuum of potential tissue damage postulated by Skegg (2005) and confirmed by factor analysis. We created a 4-point, ordinal severity score based on the highest level of severity endorsed on the SIQ. A score of 0 = non-endorsement of any NSSI behaviors; 1 = endorsement of low-severity NSSI methods (“constantly pick at scabs until they scar” and/or “pull or play with your hair so much that it comes out”); 2 = endorsement of the mild-to-moderate severity NSSI methods: “cut, scratch, or poke skin with pins or other sharp objects until you bleed/scar on purpose,” “cut words, shapes or initials into your skin,” “hit yourself so hard or so frequently on purpose to the point of bruising”; and 3 = endorsement of the highest level of severity on this scale: “burn yourself on purpose.” All 11 young women with a score of 3 also endorsed between two and five lower-severity NSSI methods.

Number of suicide attempts

Suicide attempts were queried via the Barkley Suicide Questionnaire and Family Information Packet (FIP). The former (Barkley, 2006) is a self-report questionnaire with three yes/no items: (e.g., “Have you ever considered suicide?” “Have you ever attempted suicide?” and “Have you ever been hospitalized for an attempt?”). A positive endorsement to any question is followed up with a frequency question (e.g., “How many times?”). We analyzed the dichotomous suicide attempts item. The FIP, completed by the primary caregiver (sometimes with assistance by the young adult), inquired about a number of life events, including suicide attempts, between Wave 2 and Wave 3. In the single case for which the FIP yielded an attempt but the Barkley scale did not, the individual was counted as positive for attempted suicide.

Wave 2 Hypothesized Mediators

Swanson, Nolan, and Pelham Rating Scale – 4 edition (SNAP-IV; Swanson, 1992)

The SNAP is an informant-report checklist of the nine DSM-IV items for inattention, the six items for hyperactivity, and the three items for impulsivity, with each scored on a 0 (not at all) to 3 (very much) metric. The SNAP-IV is used extensively in ADHD treatment and assessment research (e.g., MTA Cooperative Group, 1999). It has good internal consistency and test-retest reliability. Mean parent and teacher scores for the three impulsivity items were used (or individual scores if only one informant report was available), employing the “or” rule.

Conners' Continuous Performance Task (CPT; Conners 1995)

The CPT is a 14-minute computerized visual task for which participants press the spacebar when a target letter appears on the screen (all letters except ‘X’) and avoid pressing the spacebar when they see the letter ‘X.’ Failing to inhibit the bar-pressing response to the letter “X” is considered an error of commission. Percentage of commission errors is a commonly used measure of behavioral impulsivity (Janis & Nock, 2009; McGee, Clark, & Symons, 2000); girls with ADHD exhibit higher percentages of commission errors than comparisons, with effect sizes in the medium range (Hinshaw et al., 2002; Hinshaw et al., 2007). We reverse-scored this variable such that higher scores signified less impulsive performance.

Cancel Underline Task (CUL)

The CUL is a modified version of the Underlining Task (see Rourke & Orr, 1977). It measures inhibitory control and rapid, accurate visual discrimination. Participants were asked to underline targets (shape or consonant sequences) and cancel non-targets (ratio of 1:5). Scores are derived from correct minus incorrect responses (Nigg, Hinshaw, Carte, & Treuting, 1998). Individuals with ADHD make more errors than do comparisons (e.g., Hinshaw et al., 2002; Hinshaw et al., 2007; Nigg et al., 1998). We analyzed CUL-shapes and CUL-consonant scores separately.

Internalizing symptoms

We created a composite score to form a continuous measure of internalizing symptoms. This composite was formed from parent and teacher ratings of the Internalizing broadband factor from the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) and Teacher Report Form, respectively (TRF) (Achenbach 1991a; Achenbach, 1991b) and the total score from the adolescent-reported Children's Depression Inventory (CDI; Kovacs, 1992). Measures were combined or used individually when only one informant was available. Component measures were z-scored before we calculated summed composite scores. All instruments have excellent validity, test-retest reliability, and internal consistency. Correlations among the three scales were small to moderate (r = .27-.36).

Externalizing symptoms

In parallel, we formed a continuous composite score of externalizing symptoms from parent and teacher ratings of the Externalizing broadband factor from the CBCL and TRF. Measures were summed or were used individually when only one informant was available. These two scales were moderately correlated (r = .52) and z-scored before calculating the composite scores. Psychometrics for these CBCL factors are also excellent.

Covariates

We included several important background variables as covariates: (1) Full Scale IQ at Wave 1, indexed by the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, third edition (WISC-III; Wechsler, 1991), which has well-established psychometric properties; (2) race; (3) a composite of parent report of family income and maternal education at Wave 1 to indicate socioeconomic status (SES); (4) the presence versus absence of stimulant medications and of SSRIs/antidepressants during the year preceding the Wave 3 follow-up; and (5) age in years at the Wave 3 follow-up.

Data Analytic Plan

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS for Mac (Version 19; SPSS, 2010). First, we calculated one-way analyses of variance (ANOVA) to assess group differences between ADHD subtypes and the comparison group, diagnosed at Wave 1, with respect to the Wave 3 NSSI variables (frequency, variety, and lethality) as well as reports of suicide attempts (the latter is a confirmation of findings reported in Hinshaw et al., 2012). We then performed analyses of covariance (ANCOVAs) to address the potential effects of covariates. In both cases, Tukey post-hoc tests were used to examine pairwise differences between subgroups (ADHD-C, ADHD-I, and comparison). Second, we conducted parallel ANOVAs/ANCOVAs to assess group differences among young women with a persistent ADHD diagnosis, young women with a transient ADHD diagnosis, and a lifetime non-diagnosed group. Third, for mediational analyses, we used a bootstrap procedure to investigate the effects of single and multiple mediators on the Wave 1 ADHD-Wave 3 NSSI and Wave 1 ADHD-Wave 3 suicide attempt links (Preacher & Hayes, 2008; Shrout & Bolger, 2002). The predictor was Wave 1 ADHD status; potential mediators were Wave 2 measures of impulsivity, response inhibition, and externalizing and/or internalizing behaviors; and the criterion measures of NSSI or suicide attempts were measured at Wave 3. The bootstrap procedure is a statistical simulation in which a new mathematical sample is created by randomly sampling observations from the original data with replacement. Next, a point estimate of the mediated effect (a-prime × b-prime) is determined for the sample and repeated 10,000 times, with all point estimates aggregated to arrive at an overall estimate of the effect. We formed 95% bias-corrected and accelerated confidence intervals based upon the distribution of these effects and inferred statistical significance if this interval did not contain 0 (see Preacher & Hayes, 2008; Shrout & Bolger, 2002). All models included the covariates noted above, which functioned as statistical controls of the mediator and outcome variable. We also conducted separate analyses using ordinary least squares (OLS) regression to ensure that the predictor-mediator and mediator-outcome pathways were in the hypothesized directions.

Results

Predicting Self-harm from Wave 1 ADHD Status

Table 1 presents mean values of NSSI frequency, variety, and severity, plus the percentage of young women who reported at least one suicide attempt, for the two childhood-diagnosed ADHD subtypes (i.e., ADHD-C and ADHD-I) and the comparison group. The findings remained significant after controlling for age, race, IQ, SES, and medication treatment. Tukey post-hoc comparisons revealed that young women with childhood-diagnosed ADHD-C reported more frequent NSSI than comparison girls (with a large effect size), but the two ADHD subtypes did not significantly differ. Young women with childhood-diagnosed ADHD-C used a wider variety of methods and engaged in more severe NSSI than those in the comparison and ADHD-I groups, who did not differ. Effect sizes (Cohen's d) were small for NSSI variety and medium (or even large) for NSSI frequency and severity.

Table 1. Wave 3 Non-Suicidal Self-Harm and Suicide Attempts by Wave I ADHD Diagnostic Status.

| Dependent variable (DV) | Comparison | ADHD-I | ADHD-C | Pa | ESb and post-hoc | Covariatcs | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | M (SD) | N | M (SD) | N | M (SD) | 0-1 | 0-2 | 1-2 | pc | ||

| NSSI Frequency | 78 | 0.9 (1.8) | 38 | 2.0 (4.1) | 80 | 3.5 (4.9) | .000 | .35, ns | .71*** | .33, ns | .029 |

| NSSI Variety | 79 | 0.3 (0.7) | 38 | 0.6 (1.2) | 81 | 1.1 (1.4) | .000 | .28, ns | .35*** | .20* | .022 |

| NSSI Severity | 79 | .33 (.67) | 38 | .47 (.86) | 81 | 1.1 (1.1) | .000 | .20, ns | .85*** | .64** | .014 |

| Suicide Attempts | 85 | 6.0% | 39 | 7.0% | 85 | 22.0% | .004 | 1.3, ns | 4.5** | 3.5* | .004 |

ADHD-C = Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder – Combined Type; 0 = Comparison; 1 = ADHD-I; 2 = ADHD-C; NSSI = Non-suicidal self-injurious behavior.

Significance: ANOVA.

Effect size is Cohen's d, reflecting subgroup contrasts.

Significance: ANCOVA.

Prediction of Self-harm from Diagnostic Persistence of ADHD over Time

Table 2 presents differences for the three NSSI variables and reports of suicide attempts in young women from the persistent ADHD, transient ADHD, and lifetime never-diagnosed groups. Young women with persistent ADHD had significantly higher reports of NSSI frequency, variety, and severity relative to those in the transient ADHD and lifetime comparison groups, who did not significantly differ on any variable. The persistent ADHD group had significantly higher reports of suicide attempts relative to the lifetime comparison group but did not differ from the transient ADHD group. Effect sizes (Cohen's d) ranged from small to medium for the NSSI frequency variable and medium to large for the NSSI variety and NSSI severity variables. These findings withstood adjustment of all key covariates with the exception of NSSI severity, which lost significance in the ANCOVA. Consideration of individual covariates revealed that treatment with stimulant or SSRI/antidepressant medication in the past year contributed to the lack of group differences for NSSI severity. As for suicide attempts, the persistent ADHD group had a higher rate (22%) than the lifetime comparison group (4%), but did not significantly differ from the transient ADHD group (13%). The latter two groups did not differ significantly. The odds ratio for the persistent ADHD versus the lifetime comparison group was 6.7. These findings remained consistent after controlling for key covariates.

Table 2. Wave 3 Non-Suicidal Self-Harm and Suicide Attempts by Diagnostic Persistence.

| Dependent variable (DV) | Lifetime Comparison (W1/W3) | Transient ADHD (W1 or W3) | Persistent ADHD (W1 and W3) | Pa | ESb and post-hoc | Covariates | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | M (SD) | N | M (SD) | N | M (SD) | c-t | c-p | t-p | Pc | ||

| NSSI Frequency | 67 | 0.8(1.7) | 60 | 1.4(2.5) | 69 | 4.3 (5.4) | .000 | .28, ns | 40*** | .32*** | .008 |

| NSSI Variety | 68 | 0.3 (0.6) | 60 | 0.5 (0.9) | 70 | 1.3(1.5) | .000 | .27, ns | .88*** | .66*** | .016 |

| NSSI Severity | 68 | 0.3 (0.7) | 60 | 0.5 (0.9) | 70 | 1.1(1.1) | .000 | .25, ns | .87*** | .60*** | .075 |

| Suicide Attempts | 73 | 4.0% | 63 | 13% | 72 | 22.0% | .005 | 3.4, ns | 6.7** | 2.0. ns | .012 |

Note. ADHD = Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder; W1 = Wave 1; W3 = Wave 3; NSSI = Non-suicidal self-injurious” behavior; c = lifetime comparison group; t = transient ADHD; p = persistent ADHD.

Significance: ANOVA.

Effect size is Cohen's d, reflecting subgroup contrasts.

Significance: ANCOVA.

Mediational Analyses

Bootstrap analyses were used to test the association between Wave 1 ADHD status-Wave 3 NSSI severity linkage and Wave 1 ADHD status-Wave 3 suicide attempts linkage with respect to candidate mediators measured at Wave 2. For each linkage, we examined six mediation models with the following candidate mediators: (1) SNAP impulsivity subscale; (2) CPT commission errors percentage; (3) CUL shape scores; (4) CUL consonant scores; (5) internalizing symptoms composite; and (6) externalizing symptoms composite. If more than one significant mediator emerged in the individual models, they were then entered simultaneously into more complex models.

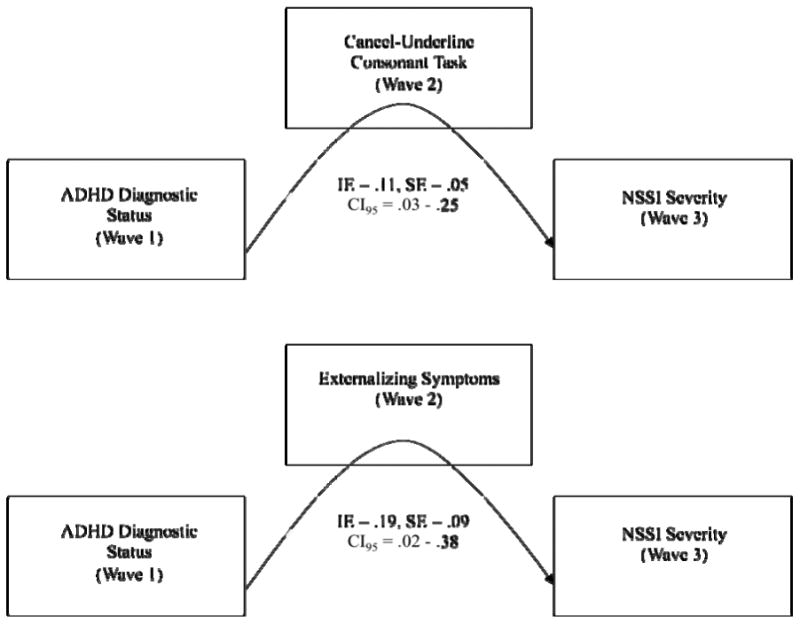

ADHD-NSSI severity linkage

There was a significant and positive relation between Wave 1 ADHD status and Wave 3 NSSI severity scores, b= .28, standard error [SE] = 13, t(195) 2 = 4.12, p < .001, R2 = .08. The Wave 2 CUL consonant scores variable was a significant partial mediator of the relation between Wave 1 ADHD status and Wave 3 NSSI severity, indirect effect [IE] = .11, SE = .05, CI95 = .03 - .25. Importantly, given concerns about demands on phonological awareness skills associated with the CUL consonant task (McGee, Clark & Symons, 2000), this finding remained significant after controlling for childhood (Wave 1) reading disorder status (defined as presence vs. absence of Wechsler Individual Achievement Test reading score < 85; see Hinshaw, 2002). The Wave 2 externalizing symptoms composite was also a significant partial mediator of the relation between Wave 1 ADHD status and W3 NSSI severity scores, IE = .19, SE =.09, CI95 = .02 = .38. None of the other candidate mediators were significant (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

(top panel) The relation between Wave 1 ADHD diagnostic status and Wave 3 NSSI severity scores partially mediated by the Wave 2 Cancel Underline Consonant task. (bottom panel) The relation between Wave 1 ADHD diagnostic status and Wave 3 NSSI severity scores partially mediated by Wave 2 externalizing symptoms. (both panels) Data represent indirect effect and standard errors using 10,000 bootstrap samples to obtain bias-corrected and accelerated ninety-five percent confidence intervals.

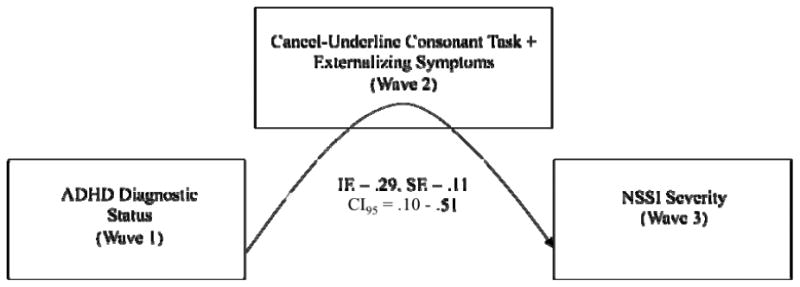

We then entered the CUL consonant and externalizing composite scores simultaneously into the model (see Figure 2). Both variables significantly mediated the relation between Wave 1 ADHD status and W3 NSSI severity scores, IE = .29, SE = .11, CI95 = .10 – .51 (see Figure 2). When we compared the model fit to determine whether the two-mediator model explained more variance than either of the single-mediator models, it did in each instance: F-ratio = 5.14, F(1, 175) = 3.84, p < .05 contrasting the two-mediator model with CUL consonant only; F-ratio = 7.801, F(1, 175) = 3.84, p < .05 contrasting the two-mediator model with externalizing composite only. In all, a lab-based measure of response inhibition, along with externalizing symptoms, both measured in adolescence, were simultaneous partial mediators of the ADHD-NSSI severity link.

Figure 2.

The relation between Wave 1 ADHD diagnostic status and Wave 3 NSSI severity scores mediated by the Wave 2 Cancel Underline Consonant task and Wave 2 externalizing symptoms. Data represent indirect effect and standard errors using 10,000 bootstrap samples to obtain bias-corrected and accelerated ninety-five percent confidence intervals.

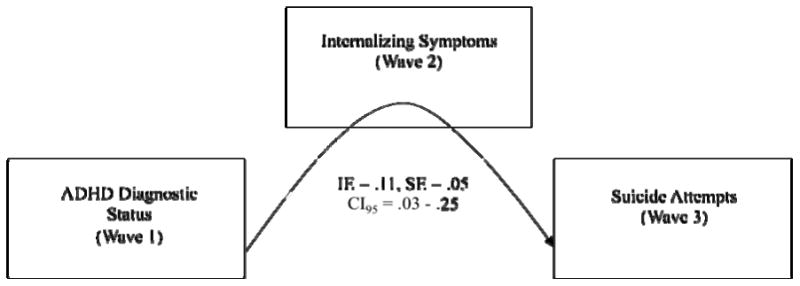

ADHD-suicide attempt linkage

There was a significant positive relation between Wave 1 ADHD status and Wave 3 suicide attempts, b= .28, standard error [SE] = 13, t(195) = 4.12, p < .001, R2 = .08. Wave 2 internalizing composite was a significant partial mediator, indirect effect [IE] = .11, SE = .05, CI95 = .03 - .25. None of the other candidate mediators attained significance (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The relation between Wave 1 ADHD diagnostic status and Wave 3 suicide attempts mediated by Wave 2 internalizing symptoms. Data represent indirect effect and standard errors using 10,000 bootstrap samples to obtain bias- corrected and accelerated ninety-five percent confidence intervals.

Discussion

In this examination of NSSI and suicide attempts, we greatly expanded on the preliminary findings reported by Hinshaw et al. (2012) of high rates in girls diagnosed with ADHD-C during childhood. Specifically, we examined NSSI frequency, number of NSSI methods tried, and NSSI severity; we also investigated whether the NSSI indicators and the suicide attempts variable were linked with ADHD diagnostic persistence from childhood through young adulthood. Crucially, we aimed to elucidate the pathways between ADHD and self-harming behaviors by examining theoretically driven candidate mediator processes measured during adolescence: comorbid psychopathology and impulsivity.

Key findings are as follows: (1) Young women with childhood-diagnosed ADHD-C engaged in the most severe forms of NSSI and experimented with the widest variety of methods, relative to the childhood-diagnosed ADHD-I and comparison groups. Both ADHD subtypes engaged in more frequent NSSI than the comparison group but did not significantly differ from each other. All of these findings survived stringent statistical control of key covariates. (2) Young women with a persistent ADHD diagnosis (i.e., Wave 1 and Wave 3) reported greater NSSI frequency, used a wider variety of NSSI methods, and engaged in more severe NSSI than those with transient ADHD and the comparison group, which did not differ significantly. Young women with persistent ADHD also had a higher rate of suicide attempts than the lifetime comparison group but did not significantly differ from the transient ADHD group. Nearly all findings survived control of key covariates, except for NSSI severity, for which recent medication treatment contributed to the loss of group differences this variable. (3) Externalizing symptoms and a lab-based measure of response inhibition/impulsivity ascertained during adolescence emerged as significant partial mediators of the ADHD-NSSI severity link; internalizing symptoms during adolescence emerged as a significant partial mediator of the ADHD-suicide attempt linkage.

Our findings are consistent with those of Chronis-Tuscano et al. (2010), who found that children (particularly girls) with ADHD-C and ADHD-HI, but not ADHD-I, were at increased risk for adolescent suicide attempts. HI is clearly implicated in the path from childhood ADHD to young-adult self-harm. Persistence of ADHD between childhood and adulthood was associated with the most dangerous pattern of self-harming behaviors, relative to transient ADHD and the lifetime comparison group. This finding is consistent with the perspective of Cicchetti and Rogosch (2002) regarding cascading chains of difficulties across development. Individuals with persistent ADHD-related impairments appear to be at risk for increased difficulty beyond adolescence.

We presented novel mediation analyses of pathways from childhood (Wave 1) ADHD status and young-adult (Wave 3) reports of NSSI severity or suicide attempt, via adolescent (Wave 2) variables. NSSI was moderately associated with suicide attempts (r = .51), yet different symptoms (internalizing versus externalizing) mediated the two pathways. It is noteworthy that concurrent externalizing and internalizing diagnoses may be more strongly associated with suicide attempts and NSSI than either alone (Goldston et al., 2009; Nock et al., 2006). Sample size limitations may have precluded our attempt to find mediation via concurrent internalizing and externalizing symptoms.1

The pattern of findings regarding the mediating role of impulsivity/response inhibition was intriguing. First, none of the impulsivity measures mediated the ADHD-suicide attempt linkage, and only one lab-based measure of impulsivity emerged as a significant partial mediator of the ADHD-NSSI severity link. Although McCloskey, Look, Chen, Pajoumand, and Berman (2012) found that individuals who engage in NSSI did not show higher laboratory impulsivity than comparisons, we found a significant mediational effect of a lab measure. The CUL-consonant task may tap a particular aspect of impulsivity linked to NSSI (i.e., response inhibition). It also requires scanning multiple letters in a sequence versus one shape at a time, requiring greater effort than CUL-shapes. Importantly, the mediator effect withstood adding the covariate of reading disorder status. Finally, we note that the three impulsivity items from the SNAP, directly tapping the three impulsivity items in the DSM criteria for ADHD, do not appear to cover this broad, multidimensional construct.

Our investigation should be viewed in the context of limitations, many of which provide important launching points for future research efforts. First, it is unclear whether these findings generalize to males with ADHD, for whom self-harming profiles and key mediating factors are not well known. Second, in terms of associations between ADHD persistence and self-harming behaviors, we lacked adequate power to investigate persistence of the individual subtypes (i.e., ADHD-C and ADHD-I). Future research efforts may also consider utilizing other definitions of persistence. Indeed, Barkley and colleagues (2002, 2008) suggest strongly that the prognosis of ADHD depends largely on the definition of persistence (e.g., diagnostic, symptomatic, persistence of functional impairment); even subsyndromal forms of ADHD are associated with significant impairment (e.g., Faraone et al., 2006).

Limitations in measurement frequency limited our analytic options and explanatory scope. For example, the only time point at which we inquired about NSSI and suicidal behavior was Wave 3, when we asked about lifetime occurrence of the behaviors in question. We were therefore unable provide crucial information about rates and hazard of these behaviors or establish temporal associations between ADHD and self-harmful behaviors. We assume that our adolescent mediators preceded the occurrence of these outcomes, but we cannot be absolutely certain. Moreover, the SIQ covered a somewhat narrow range of NSSI behaviors. At the next wave of data collection, we plan to administer the Self-Injurious Thoughts and Behaviors Interview (SITBI), developed by Nock, Holmberg, Photos, and Michel (2007), comprising a comprehensive structured interview that queries a wider range of self-injurious thoughts and behaviors. We also plan to include a broader assessment of impulsivity, including self-report questionnaires, lab-based performance tests, and personality measures. See, for example, the UPPS scale of Whiteside and Lynam (2001), which assesses urgency, lack of perseverance, lack of premeditation, and sensation-seeking.

Crucially, there are many known risk factors for self-harming behaviors. In particular, peer victimization may be a particularly salient risk factor for females with ADHD, who have elevated rates of both overt and relational peer victimization relative to comparison peers (Cardoos & Hinshaw, 2011; Hinshaw, 2002; Wiener & Mak, 2009). Multiple lines of research suggest that overt and relational peer victimization is associated with long-term global maladjustment in children and adolescents (Cullerton-Sen & Crick, 2005; Ladd & Ladd, 2001), including NSSI and suicide attempts (e.g., Hilt et al., 2008; Klomek, Marrocco, Kleinman, Schonfeld & Gould, 2008). It will also be useful to explore protective factors that may decrease the probability of NSSI and suicide attempts in young women with ADHD. For example, religious beliefs/practices and spirituality are associated with fewer suicide attempts, as are perceptions of social and family support and connectedness (Nock et al., 2008).

Overall, our findings underscore the importance of thorough and frequent monitoring of self- harmful behaviors among girls and young women with ADHD, particularly those with ADHD-C and those with persistent diagnostic profiles. Evidence-based treatment to reduce high levels of impulsivity and comorbid symptoms may help to reduce risk. Given the devastating nature of self- harmful behavior, further work in both basic science and clinical science is urgently needed.

Key points.

Girls with a history of ADHD show continued impairments through young adulthood, and some of these may surpass those of boys with such a history.

Across a 10-year prospective interval from childhood through early adulthood, girls with ADHD-Combined type (featuring prominent symptoms of impulsivity) were at strikingly high risk for self-harm—including (a) frequency, severity and variety of non-suicidal self-injurious behavior (NSSI) and (b) suicide attempts. Participants with persistent ADHD were at higher risk for such behaviors than those with transient ADHD.

Adolescent factors mediating the childhood ADHD to young adult self-harm linkages were as follows: (a) for NSSI, externalizing behavior and an objective measure of poor response inhibition; and (b) for suicide attempts, internalizing behavior.

Further understanding of life-course pathways for girls with severe impulse control problems is a key priority for basic and applied research efforts.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by National Institute of Mental Health Grant R01 MH45064. It is based on a doctoral dissertation conducted by Erika N. Swanson at UC Berkeley. We gratefully acknowledge the girls—now young women—who have participated in our ongoing investigation, along with their caregivers and our large numbers of graduate students and research assistants. Their remarkable dedication has made this research possible. We also thank Fred Loya, Meghan Miller, and Christine Zalecki for their great assistance.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: No conflicts declared.

The authors have declared that they have no competing or potential conflicts of interest.

For the ADHD-NSSI severity linkage, a sample size of 445 would be required to detect a significant mediated effect with a power of .8 (Fritz & MacKinnon, 2007). Thus, power issues preclude a definitive statement of whether internalizing symptoms may indeed be an additional mediator of the ADHD-NSSI severity link.

References

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist and Revised Child Behavior Profile. Burlington, VT: University Associates in Psychiatry; 1991a. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the Teacher Report Form and 1991 Profile. Burlington, VT: University Associates in Psychiatry; 1991b. [Google Scholar]

- Babinski DE, Pelham WE, Molina BSG, Gnagny EM, Waschbusch DA, Yu J, Karch KM. Late adolescent and young adult outcomes of girls diagnosed with ADHD in childhood: An exploratory investigation. Journal of Attention Disorders. 2011;15(3):204–214. doi: 10.1177/1087054710361586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkley RA, Fischer M, Smallish L, Fletcher K. The persistence of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder into young adulthood as a function of reporting source and definition of disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;111(2):279–289. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.111.2.279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkley RA, Murphy KR. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: A clinical workbook. 3rd. New York: Guilford; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Barkley RA, Murphy KR, Fischer M. ADHD in adults: What the science says. New York: Guilford; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J, Ball SW, Monuteaux MC, Mick E, Spencer TJ, McCreary M, Faraone SV. New insights into the comorbidity between ADHD and major depression in adolescent and young adult females. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2008;47(4):426–434. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e31816429d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J, Petty CR, Monuteaux MC, Fried R, Byrne D, Mirto T, Faraone SV. Adult psychiatric outcomes of girls with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: 11-year follow-up in a longitudinal case-control study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;167:409–417. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09050736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brausch AM, Gutierrez PM. Differences in non-suicidal self-injury and suicide attempts in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2010;39:233–242. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9482-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardoos SL, Hinshaw SP. Friendship as protection from peer victimization for girls with and without ADHD. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2011;39(7):1035–1045. doi: 10.1007/s10802-011-9517-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Web-based Injury Statistics Query And Reporting System (WISQARS) 2006 Available from: http://www.cdc.gov.injury/

- Chronis-Tuscano A, Molina BSG, Pelham WE, Applegate B, Dahlke A, Overmeyer M, Lahey B. Very early predictors of adolescent depression and suicide attempts in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2010;67(10):1044–1051. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Rogosch FA. A developmental psychopathology perspective in adolescence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70(1):6–20. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.70.1.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claes L, Vandereycken W, Vertommen H. Self-injurious behavior in eatingdisordered patients. Eating Behaviors. 2001;2:263–272. doi: 10.1016/S1471-0153(01)00033-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colledge E, Blair RJR. The relationship between the inattention and impulsivity component of attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder and psychopathic tendencies. Personality and Individual Differences. 2001;30(7):1175–1187. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00101-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Conners CK. Conners' continuous performance test computer program: User's manual. Toronto: Multi-Health Systems; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Cullerton-Sen C, Crick NR. Understanding the effects of physical and relational victimization: The utility of multiple perspectives in predicting social-emotional adjustment. School Psychology Review. 2005;34(2):147–160. 17407203. [Google Scholar]

- Dahl RE. Adolescent brain development: A period of vulnerabilities and opportunities. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2004;1021:1–22. doi: 10.1196/annals.1308.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darche MA. Psychological factors differentiating self-mutilating and non-self-mutilating adolescent inpatient females. Psychiatric Hospital. 1990;21:31–35. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/617747575?accountid=14496. [Google Scholar]

- Faraone SV, Biederman J, Spencer T, Mick E, Murray K, Petty C, et al. Diagnosing adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: Are late onset and subthreshold diagnoses valid? American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163(10):1720–1729. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.10.1720. AJP/3778/06aj1720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritz MS, MacKinnon DP. Required sample size to detect the mediated effect. Psychological Science. 2007;18(3):233–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01882.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldston DB, Daniel SS, Erkanli A, Reboussin BA, Mayfield A, Frazier PH, Treadway SL. Psychiatric diagnoses as contemporaneous risk factors for suicide attempts among adolescents and young adults: Developmental changes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77(2):281–290. doi: 10.1037/a0014732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould MS, King R, Greenwald S, Fisher P, Scwab-Stone M, Kramer R, Shaffer D. Psychopathology associated with suicidal ideation and attempts among children and adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1998;37(9):915–923. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199809000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerry JD, Prinstein MJ. Longitudinal prediction of adolescent nonsuicidal self-injury: Examination of a cognitive vulnerability-stress model. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2010;39(1):77–89. doi: 10.1080/15374410903401195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gvion Y, Apter A. Aggression, impulsivity, and suicide behavior: A review of the literature. Archives of Suicide Reseach. 2011;15(2):93–112. doi: 10.1080/13811118.2011.565265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Abramson LY, Moffitt TE, Silva PA, McGee R, Angell KE. Development of depression from preadolescence to young adulthood: Emerging gender differences in a 10-year longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1998;107:128–140. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.107.1.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilt LM, Cha CB, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Nonsuicidal self-injury in young adolescent girls: Moderators of the distress-function relationship. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76(1):63–71. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.1.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinshaw SP. Preadolescent girls with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: I. Background characteristics, comorbidity, cognitive and social functioning, and parenting practices. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70(5):1086–1098. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.70.5.1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinshaw SP, Carte ET, Fan C, Jassy JS, Owens EB. Neuropsyhological functioning of girls with attnention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder followed prospectively into adolescence: Evidence for continuing deficits? Neuropsychology. 2007;21(2):263–273. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.21.2.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinshaw SP, Carte ET, Sami N, Treuting JJ, Zupan BA. Preadolescent girls with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: II. Neuropsychological performance in relation to subtypes and individual classification. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70(5):1099–1111. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.70.5.1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinshaw SP, Owens EB, Sami N, Fargeon S. Prospective follow-up of girls with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder into adolescence: Evidence for continuing crossdomain impairment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74(3):489–499. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.3.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinshaw SP, Owens EB, Zalecki C, Huggins SP, Montenegro-Nevado AJ, Schrodek E, Swanson EN. Prospective follow-up of girls with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder into early adulthood: Continuing impairment includes elevated risk for suicide attempts and self-injury. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2012;80(6):1041–1051. doi: 10.1037/a0029451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janis IB, Nock MK. Are self-injurers impulsive?: Results from two behavioral laboratory studies. Psychiatry Research. 2009;169:261–267. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2008.06.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE. Why people die by suicide. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Klein RG, Ramos OMA, Castellanos FX, Lashua EC, Roizen E, Hutchison JA, Mannuzza S. Clinical and functional outcome of childhood attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder 33 years later. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2012;69(12):1295–1303. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2012.271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klomek AB, Marrocco F, Kleinman M, Schonfeld IS, Gould MS. Peer victimization, depression, and suicidality in adolescents. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2008;38(2):166–180. doi: 10.1521/suli.2008.38.2.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M. Children's depression inventory (CDI) manual. Toronto, CA: Multi-Health Systems, Inc; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M, Goldston D, Gatsonis C. Suicidal behaviors and childhood-onset depressive disorders: A longitudinal investigation. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1993;32(1):8–20. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199301000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladd BK, Ladd GW. Variations in peer victimization: Relations to children's maladjustment. In: Juvonen J, Graham S, editors. Peer harassment in school: The plight of the vulnerable and victimized. New York: Guilford; 2001. pp. 25–48. [Google Scholar]

- Lijffijt M, Kenemans JL, Verbaten MN, van Engeland H. A meta-analytic review of stopping performance in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: Deficient inhibitory motor control? Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005;114(2):216–222. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.2.216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd-Richardson EE. Adolescent nonsuicidal self-injury: Who is doing it and why? Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2008;29(3):216–218. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2008.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannuzza S, Klein RG. Long-term prognosis in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2000;9:711–726. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathias CW, Furr MR, Daniel SS, Marsh DM, Shannon EE, Dougherty DM. The relationship of inattentiveness, hyperactivity, and psychopathy among adolescents. Personality and Individual Differences. 2007;43(6):1333–1343. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2007.04.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McCloskey MS, Look AE, Chen EY, Pajoumand G, Berman ME. Nonsuicidal self-injury: Relationship to behavioral and self-rating measures of impulsivity and self-aggression. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2012;42(2):197–209. doi: 10.1111/j.1943-278X.2012.00082.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGee RA, Clark SE, Symons DK. Does the Conners' continuous performance test aid in ADHD diagnosis? Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2000;28:415–424. doi: 10.1023/A:1005127504982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikami AY, Hinshaw SP. Eating pathology among adolescent girls with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2008;117(1):225–235. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.117.1.225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller M, Hinshaw SP. Does childhood executive function predict adolescent functional outcomes in girls with ADHD? Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2010;38:315–326. doi: 10.1007/s10802-009-9369-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller DJ, Derefinko KJ, Lynam DR, Milich R, Fillmore MT. Impulsivity and attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder: Subtype classification using the UPPS impulsive behavior scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2010;32:323–332. doi: 10.1007/s10862-009-9155-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MTA Cooperative Group. Fourteen-month randomized clinical trial of treatment strategies for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1999;56:1073–1086. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.12.1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigg JT, Hinshaw SP, Carte ET, Treuting JJ. Neuropsychological correlates of childhood attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: Explaining by comorbid disruptive behavior or reading problems? Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1998;107:468–480. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.107.3.468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK. Why do people hurt themselves? New insights into the nature and functions of self-injury. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2009;18(2):78–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01613.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK. Future directions for the study of suicide and self-injury. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2012;41:255–259. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2012.652001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Borges G, Bromet EJ, Cha CB, Kessler RC, Lee S. Suicide and suicidal behavior. Epidemiologic Reviews. 2008;30:133–154. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxn002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Holmberg EB, Photos VI, Michel BD. Self-injurious thoughts and behaviors interview: Development, reliability, and validity in an adolescent sample. Psychological Assessment. 2007;19(3):309–317. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.19.3.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK, Joiner TE, Gordon KH, Lloyd-Richardson E, Prinstein MJ. Non-suicidal self-injury among adolescents: Diagnostic correlates and relation to suicide attempts. Psychiatry Research. 2006;144:65–72. doi: 10.1016/j.psychred.2006.05.010.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien JW, Dowell LR, Mostofsky SH, Denckla MB, Mahone ME. Neuropsychological profile of executive function in girls with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology. 2010;25(7):656–670. doi: 10.1093/arclin/acq050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piacentini JC, Cohen P, Cohen J. Combining discrepant diagnostic information from multiple sources: Are complex algorithms better than simple ones? Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1992;20(1):51–63. doi: 10.1007/BF00927116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods. 2008;40(3):879–891. doi: 10.3758/BRM.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinstein MJ. Introduction to the special section on suicide and nonsuicidal self-injury: A review of unique challenges and important directions for self-injury science. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76(1):1–8. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodham K, Hawton K, Evans E. Reasons for deliberate self-harm: Comparison of self-poisoners and self-cutters in a community sample of adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004;43(1):80–87. doi: 10.1097/00004383-200401000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross S, Heath N. A study of the frequency of self-mutilation in a community sample of adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2002;31:67–77. doi: 10.1023/A:1014089117419. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rourke BP, Orr RR. Prediction of reading and spelling performance of normal and retarded readers: A 4-year follow-up. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1977;5:9–20. doi: 10.1007/BF00915756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seymour KE, Chronis-Tuscano A, Halldorsdottir T, Stupica B, Owens K, Sacks T. Emotion regulation mediates the relationship between ADHD and depressive symptoms in youth. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2012;40:595–606. doi: 10.1007/s10802-011-9593-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer D, Fisher P, Lucas C, Dulcan MK, Schwab-Stone M. NIMH Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children, Version IV: Description, differences from previous versions, and reliability of some common diagnoses. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39:28–38. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200001000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shrout PE, Bolger N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods. 2002;7(4):422–445. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.7.4.422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skegg K. Self-harm. Lancet. 2005;366:1471–1483. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67600-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson JM. Assessment and treatment of ADD students. Irvine, CA: K.C. Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Twenge JM, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Age, gender, race, socioeconomic status, and birth cohort difference on the children's depression inventory: A meta-analysis. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;111:578–588. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.111.4.578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderlinden J, Vandereycken W. Trauma, dissociation, and impulsive dyscontrol in eating disorders. Philadelphia, PA: Taylor & Francis Group; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Weafer J, Milich R, Fillmore MT. Behavioral components of impulsivity predict alcohol consumption in adults with ADHD and healthy controls. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2011;113(2-3):139–146. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.07.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Manual for the Wechsler intelligence scale for children. 3rd. New York, NY: Psychological Corporation/Harcourt Brace; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside SP, Lynam DR. The five factor model and impulsivity: Using a structural model of personality to understand impulsivity. Personality and Individual Differences. 2001;30(4):669–689. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00064-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wiener J, Mak M. Peer victimization in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Psychology in the Schools. 2009;46(2):116–131. doi: 10.1002/pits.20358. [DOI] [Google Scholar]