Abstract

BACKGROUND

The incidence, survival, and prevalence of neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) in children were determined as a first step in improving diagnosis and therapy. Outcomes were compared with neuroblastoma, a pediatric malignancy that shares several biomarkers.

METHODS

Incidence rates, observed survival rates and 31-year limited duration prevalence counts were obtained from SEER*Stat for diagnosis years 1975 to 2006. These rates were compared between and within NETs and neuroblastoma for demographic and tumor-related variables from 9 standard SEER registries for ages 0–29 years. Multivariate Cox regression was performed to identify prognostic factors for survival in NETs.

RESULTS

The number of NETs was 1073 compared to 1664 neuroblastomas. The most common NET sites were lung, breast, and appendix. NET five-year observed survival rates increased from 83% between 1975–1979 to 84% for the 2000–2006 period, while analogous neuroblastoma survival rates steadily increased from 45% to 73%. Five-year observed survival was less than 30% in females with NETs of the cervix and ovary. The estimated 31-year limited duration prevalence for NETs as of January 1, 2006 in the U.S. population was 7724 compared to 9960 for neuroblastomas. Age-adjusted multivariate Cox Regression demonstrated small cell histology, primary location in the breast, and distant stage as major predictors of decreased survival.

CONCLUSIONS

While survivorship has significantly increased for neuroblastoma, those diagnosed with NETs have shown no increase in survival during this 31-year period. NETs constitute an unrecognized cancer threat to children and young adults comparable to neuroblastoma in both number of affected persons and disease severity.

Keywords: Neuroendocrine tumors, Neuroblastoma, Children, SEER

INTRODUCTION

Neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) arise from the diffuse neuroendocrine system(1) and can occur in almost any endocrine or non-endocrine tissue. The most common locations for primary NETs in adults include the lung, rectum, and small intestine with a high rate of unknown primary sites(2).

Classification of a tumor as neuroendocrine is based primarily on histology showing clear cells together with positive immunohistochemistry for chromogranin A, synaptophysin and neuron specific enolase. The degree of differentiation and the proliferation marker Ki-67 are the most reliable prognostic biomarkers(3).

NETs are commonly diagnosed at a late stage, often being diagnosed on the basis of liver or bone metastases(4). Patients who are eventually diagnosed with NETs often have a multi-year history of symptoms prior to identification of the malignancy with average lag periods of 8–10 years(5). Thus, a 29-year old adult diagnosed as having a NET may well have been an adolescent when the first symptoms occurred.

Our recent evaluation of the literature yielded few published reports on NETs in children with a significant number of these children having metastatic disease with no known primary site at presentation(6–11). This observation is due in part to the wide distribution of the diffuse neuroendocrine system and to the multiple histologic diagnoses associated with NETs(12). Similarly, the primary tumor in children diagnosed with neuroblastoma can be located in adrenal or anywhere along the sympathetic nervous system chain(13). Similarities of wide distribution, wide variations in aggressiveness from benign to highly malignant, together with their shared biomarkers, namely synaptophysin, neuron specific enolase, chromogranin A, norepinephrine transporters and somatostatin receptors, provide the rationale for comparing the incidence, survival and prevalence rates for NETs and neuroblastoma in the 0–29 year age group(14).

METHODS

The National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) data were obtained from the 9 standard SEER registries (Hawaii, Seattle, San Francisco/Oakland, Utah, New Mexico, Iowa, Connecticut, Detroit, and Atlanta) for the diagnosis years of 1975 to 2006 and age groups of 0–29 years, using SEER*Stat software (version 6.5.2)(15). The identification of malignant NETs and neuroblastoma cases (9500/3) was based on the ICD-O-3 histology codes.

Incidence rates were calculated per million and age-adjusted to the 2000 US Standard Population (19 age groups - Census P25-1130). Confidence intervals used the Tiwari et al. method since this method is available and recommended for use in SEER*Stat (16). Patient characteristics considered were age (0–29 years), gender, race, year of diagnosis (1975 to 2006), primary tumor site, tumor staging based on SEER historic stage (localized, regional, distant, unstaged) and histological grading based on SEER coding manuals (17) (Grade I: well differentiated, Grade II: moderately differentiated, Grade III: poorly differentiated & Grade IV: undifferentiated/anaplastic). Joinpoint regression analysis was performed using NCI’s Joinpoint Regression Program software (version 3.3.1) (18).

Observed survival rates (5-year) and survival case listing files for NETs and neuroblastoma were obtained by using the SEER*Stat software (15); only actively followed cases of known age were selected. The observed survival rate was obtained by the actuarial method. NET cases alive at start for survival analyses were less (n=1037) as compared to NET incident cases (n=1073) as subjects with death certificate and autopsy only (n=3), with second or later primaries (n=17), and alive with no survival time (n=16) were excluded. Similarly, neuroblastoma cases alive at start for survival analysis were less (n=1633) as compared to neuroblastoma incident cases (n=1664), as subjects with death certificate and autopsy only (n=19), with second or later primaries (n=6), and alive with no survival time (n=6) were excluded.

Thirty-one-year limited duration prevalence counts for NETs and neuroblastoma as of January 1, 2006, were obtained by selecting cases of malignant behavior and known age only and excluding death certificate and autopsy only cases using the SEER*Stat software. US 2006 cancer prevalence counts were based on 2006 cancer prevalence proportions from the SEER 9 registries and 1/1/2006 US population estimates based on the average of 2005 and 2006 population estimates from the US Bureau of the Census (19).

Multivariate survival analyses were performed using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC). The Cox Regression analysis was used to assess the effect of location, histology and stage on the hazard of death, after adjusting for age.

RESULTS

As the term diffuse neuroendocrine system implies, each of these histological tumor types can occur in any organ that has endocrine cells, including thymus and thyroid in the neck region, lungs and breast in the chest, the entire intestinal tract, and gonads (ovary and testis). Among young people from 0–29 years of age, four histology codes: 8240 (malignant carcinoid), 8510 (medullary carcinoma), 8041 (small cell carcinoma), and 8246 (neuroendocrine carcinoma) accounted for 91% of the 1073 NETs reported to the SEER database from 1975–2006 (Table I). Malignant carcinoid tumors were most common in the lung while small cell carcinoma was most often found in ovary in children and young people; similarly, medullary carcinoma was more common in breast than in thyroid (Tables I and II).

Table I.

Distribution of malignant neuroendocrine tumors by 5-digit morphology code, ages 0–29, 9 Standard SEER Registries, 1975–2006

| NET ICD-0-3 codes | Count | Incidence rate* (per million) | Lower CI | Upper CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 1,073 | 2.8 | 2.6 | 3 |

| 8240/3: Carcinoid tumor, malignant | 544 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 1.6 |

| 8510/3: Medullary carcinoma, NOS | 226 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.7 |

| 8041/3: Small cell carcinoma, NOS | 109 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.3 |

| 8246/3: Neuroendocrine carcinoma | 101 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.3 |

| 8245/3: Adenocarcinoid tumor | 24 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.1 |

| 8700/3: Pheochromocytoma | 18 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.1 |

| 8680/3: Paraganglioma, malignant | 16 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 |

| 8241/3: Enterochromaffin cell carcinoid | 8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Others: 8013/3: Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma; 8044/3: Small cell carcinoma, intermediate cell; 8045/3: Combined small cell carcinoma; 8244/3: Composite carcinoid; 8247/3: Merkel cell carcinoma | 8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 8042/3: Oat cell carcinoma | 7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 8243/3: Goblet cell carcinoid | 7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 8693/3: Extra-adrenal paraganglioma, malignant | 5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

ICD-O-3 = International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, 3rd Edition;

Incidence rates are per million person-years and age-adjusted to the 2000 US standard population; Confidence intervals (Tiwari modification) are 95% for rates.

Table II.

Frequency & incidence rates for malignant neuroendocrine tumors for common sites and morphologies, 0–29 years, 9 Standard SEER Registries, 1975–2006

| Site | ICD-O-3 code | Count | Incidence rate* (per million) | Lower CI | Upper CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lung | 8240/3: Carcinoid tumor, malignant | 239 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.7 |

| Breast | 8510/3: Medullary carcinoma, NOS | 182 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 0.5 |

| Appendix | 8240/3: Carcinoid tumor, malignant | 134 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.4 |

| Hindgut | 8240/3: Carcinoid tumor, malignant | 85 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 |

| Midgut | 8240/3: Carcinoid tumor, malignant | 41 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Thyroid gland | 8510/3: Medullary carcinoma, NOS | 38 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Ovary** | 8041/3: Small cell carcinoma, NOS | 30 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Cervix | 8041/3: Small cell carcinoma, NOS | 27 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.1 |

| Foregut | 8246/3: Neuroendocrine carcinoma | 26 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.1 |

| Unknown primary site | 8246/3: Neuroendocrine carcinoma | 20 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.1 |

Incidence rates are per million person-years and age-adjusted to the 2000 US standard population; Confidence intervals (Tiwari modification) are 95% for rates;

All gonadal tumors with small cell carcinoma histology were located in ovary, none in testis.

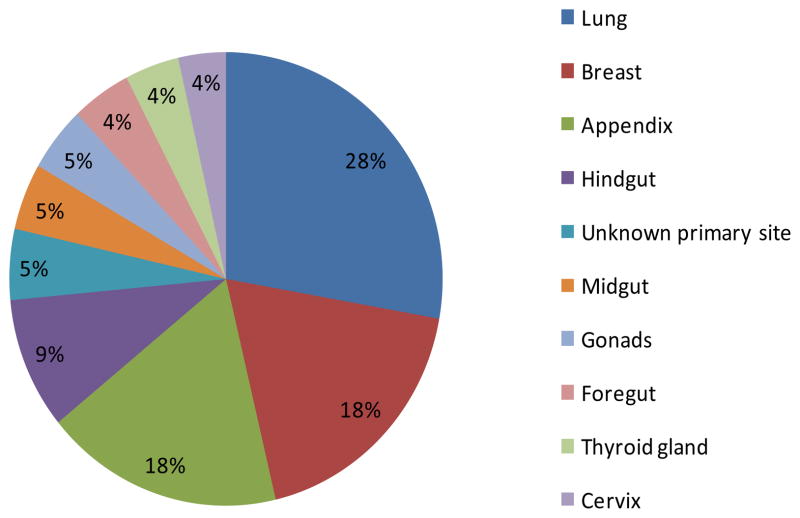

The distribution sites of NET locations in the 0–29 year age group are shown in Table II and Figure 1. Lung and breast were the most frequent anatomical sites, accounting for 39% of all NETs in this age group and reflecting the high number of neuroendocrine cells in these organs. Intestinal tissues also have a high number of endocrine cells; thus appendiceal carcinoid accounted for a significant portion of NETs. Other intestinal tissues, including colon, rectum and anal canal (hindgut); small intestine, cecum (excluding appendix), and ascending colon (midgut), and mouth, pharynx, esophagus, stomach, liver, pancreas, biliary tree and gall bladder (foregut) also contributed to the incidence rate in these young patients. Together lung (28%), breast (18%), appendix (18%), and other intestinal sites (foregut, midgut, hindgut) (18%) constituted 82% of all NETs in children and young adults (Figure 1). Gonadal NETs were located in ovary and testis, with ovary (n=40) being the more predominant organ for NET location than testis (n=6).

Figure 1.

Distribution of 1073 malignant neuroendocrine tumors by common primary sites, ages 0–29 years, 9 Standard SEER Registries, 1975–2006

To better understand the incidence rates of NETs in the context of other malignancies affecting children and young adults, we compared NET incidence with that of neuroblastoma. These two tumors express several important biomarkers in common, including the histological markers chromogranin and synaptophysin. Similarly, the norepinephrine transporter, SCL6A2, and the somatostatin receptor type 2 are utilized molecular targets for imaging and therapy in both NETs and neuroblastoma. Table III shows clear differences in incidence by age groups with neuroblastoma incidence greater in the 0–9 year’s age group, the incidence being nearly equal in the 10–14 years age group, and NETs predominantly diagnosed in adolescents and young adults. The high number of NETs in the breast and ovary (Figure 1) accounted for the female: male incidence ratio of 2:1 for NETs compared to 0.9: 1 for neuroblastoma. There appeared to be nearly equal incidence in Caucasian and African-American individuals for both tumor types. The incidence rates have been stable over the 31-year period from 1975–2006 for both NETs and neuroblastoma as joinpoint regression analysis was performed, but no joinpoints were identified for either tumor type.

Table III.

Comparing frequency and incidence rates for malignant neuroendocrine tumors versus neuroblastoma by demographic and tumor characteristics, 0–29 years, 9 Standard SEER Registries, 1975–2006.

| Variables | Neuroendocrine tumors | Neuroblastoma | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | Incidence rate* (per million) | Count | Incidence rate* (per million) | ||

| Total | 1073 | 2.8 | 1664 | 4.9 | |

| Age groups | 00–04 yrs | 6 | 0.1 | 1,437 | 25.3 |

| 05–09 yrs | 7 | 0.1 | 130 | 2.3 | |

| 10–14 yrs | 55 | 1.0 | 40 | 0.7 | |

| 15–19 yrs | 138 | 2.4 | 26 | 0.4 | |

| 20–24 yrs | 273 | 4.6 | 14 | 0.2 | |

| 25–29 yrs | 594 | 9.5 | 17 | 0.3 | |

| Gender | Female | 706 | 3.7 | 773 | 4.6 |

| Male | 367 | 1.9 | 891 | 5.1 | |

| Race | White | 856 | 2.9 | 1,338 | 5.1 |

| Black | 145 | 3.0 | 195 | 4.1 | |

| Other# | 72 | 2.0 | 131 | 3.8 | |

| Year diagnosed | 1975 to1979 | 196 | 3.4 | 211 | 4.5 |

| 1980 to 1984 | 140 | 2.2 | 238 | 4.7 | |

| 1985 to 1989 | 158 | 2.6 | 245 | 4.7 | |

| 1990 to 1994 | 154 | 2.7 | 259 | 4.6 | |

| 1995 to 1999 | 148 | 2.5 | 281 | 5.1 | |

| 2000 to 2006 | 277 | 3.4 | 430 | 5.4 | |

| Stage** | Localized | 508 | 1.3 | 215 | 0.6 |

| Regional | 233 | 0.6 | 337 | 1.0 | |

| Distant | 113 | 0.3 | 840 | 2.5 | |

| Unstaged | 100 | 0.3 | 257 | 0.8 | |

| Blank*** | 118 | 0.3 | 15 | 0.0 | |

| Grade | Well differentiated | 54 | 0.1 | 43 | 0.1 |

| Moderately differentiated | 23 | 0.0 | 22 | 0.1 | |

| Poorly differentiated | 91 | 0.2 | 254 | 0.7 | |

| Undifferentiated | 67 | 0.2 | 166 | 0.5 | |

| Unknown | 838 | 2.2 | 1,179 | 3.5 | |

Incidence rates are per million person-years and age-adjusted to the 2000 US standard population; Confidence intervals (Tiwari modification) are 95% for rates;

American Indian/Alaska Natives, Asian/Pacific Islanders, Other unspecified & Unknown;

One additional case involved the prostate and was staged as localized/regional;

“The SEER Program strives to make all Localized/Regional/Distant stage variables consistent for all cancer sites for the appropriate years. However, there are certain site/year combinations where this is not possible” (http://seer.cancer.gov/seerstat/variables/seer/yr1973_2005/lrd_stage/)

Stage and grade at diagnosis were considerably different for NETs versus neuroblastoma. Local disease was the most common diagnostic stage for NETs; yet, 22% of NETs had regional spread and 10% were disseminated at diagnosis as compared to 20% regional spread and a much higher (50%) incidence of distant metastases in neuroblastoma (Table III). Tumor grade was similarly distributed for NETs and neuroblastoma, from well differentiated to undifferentiated; both tumor types had a high proportion of tumors with unknown stage reported to SEER.

Observed survival rates for children and young adults with NETs were dependent upon both site of primary tumor and histological type. Malignant carcinoid of appendix, lung and hindgut all had 5-year survival rates of 96–100% (Table IV). Medullary carcinoma of thyroid had nearly 100% 5-year survival while medullary carcinoma in the breast was associated with 81% 5-year survival. On the other hand, small cell carcinoma of cervix and ovary had 29% and 24% 5-year observed survival rate, respectively. Neuroendocrine carcinoma with unknown primary site had a 10% 5-year survival.

Table IV.

5-year observed survival rates for neuroendocrine tumors, most common sites and morphologies, 0–29 years, 9 Standard SEER Registries, 1975–2006

| Primary site-labeled | ICD-0-3 Histology Code | Alive at start | Observed survival rate* (%) | 95% confidence interval | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower limit | Upper limit | ||||

| Appendix | 8240/3: Carcinoid tumor, malignant | 131 | 100.0 | + | + |

| Hindgut | 8240/3: Carcinoid tumor, malignant | 79 | 100.0 | + | + |

| Thyroid gland | 8510/3: Medullary carcinoma, NOS | 36 | 100.0 | + | + |

| Lung | 8240/3: Carcinoid tumor, malignant | 234 | 96.3 | 92.8 | 98.1 |

| Midgut (excluding appendix) | 8240/3: Carcinoid tumor, malignant | 38 | 90.5 | 73.0 | 96.9 |

| Breast | 8510/3: Medullary carcinoma, NOS | 177 | 80.9 | 74.2 | 86.0 |

| Foregut (excluding trachea & lungs) | 8246/3: Neuroendocrine carcinoma | 26 | 45.3 | 24.6 | 64.0 |

| Cervix | 8041/3: Small cell carcinoma, NOS | 27 | 29.4 | 13.3 | 47.6 |

| Ovary** | 8041/3: Small cell carcinoma, NOS | 30 | 24.1 | 9.8 | 41.8 |

| Unknown primary site | 8246/3: Neuroendocrine carcinoma | 19 | 10.5 | 1.4 | 30.3 |

Observed survival rates are unadjusted;

All gonadal tumors with small cell carcinoma histology were located in ovary, none in testis;

+Confidence interval cannot be calculated for 100% survival

When NET survival rates were compared with the rates in neuroblastoma, age was an important, contrasting factor, with the highest survival rate in the less than 1 year age group for neuroblastoma and in the 10–14 year pre-adolescent age group for NETs (Table V). The increase in NET incidence and decrease in survival rates in the 15–29 year age group coincides with the onset of puberty and the beginning of the breast and ovarian incidence for NETs. For neuroblastoma, survival rates declined with increasing age due to declining numbers of patients with localized-regional stage. Neither gender nor race had a significant effect on 5-year survival rates for either neuroblastoma or NETs.

Table V.

5-year observed survival rates for neuroendocrine tumors versus neuroblastoma by demographic and tumor characteristics variables, 0–29 years, 9 Standard SEER Registries, 1975–2006

| Variables | Neuroendocrine tumors | Neuroblastoma | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alive at start | Observed survival rate* (%) | 95% confidence interval | Alive at start | Observed survival rate* (%) | 95% confidence interval | ||||

| Lower limit | Upper limit | Lower limit | Upper limit | ||||||

| Total | 1037 | 79 | 76.3 | 81.5 | 1633 | 59.7 | 57.2 | 62.2 | |

| Age groups | 00–04 yrs | 5 | $ | $ | $ | 1,411 | 64.0 | 61.3 | 66.5 |

| 05–09 yrs | 7 | $ | $ | $ | 130 | 30.6 | 22.3 | 39.4 | |

| 10–14 yrs | 53 | 89.7 | 77.0 | 95.6 | 37 | 47.6 | 30.2 | 63.0 | |

| 15–19 yrs | 135 | 84.2 | 76.6 | 89.5 | 25 | 24.1 | 9.2 | 42.6 | |

| 20–24 yrs | 266 | 76.2 | 70.4 | 81.1 | 14 | $ | $ | $ | |

| 25–29 yrs | 571 | 78.7 | 74.9 | 81.9 | 16 | $ | $ | $ | |

| Gender | Male | 355 | 79.0 | 74.2 | 83.1 | 875 | 57.7 | 54.2 | 61.1 |

| Female | 682 | 79.1 | 75.7 | 82.0 | 758 | 62.0 | 58.2 | 65.5 | |

| Race | Caucasian | 825 | 79.7 | 76.6 | 82.4 | 1,311 | 60.0 | 57.2 | 62.8 |

| African-American | 142 | 72.7 | 64.3 | 79.4 | 193 | 55.7 | 48.1 | 62.6 | |

| Other# | 70 | 84.2 | 72.5 | 91.2 | 129 | 62.5 | 53.0 | 70.7 | |

| Year Diagnosed | 1975–1979 | 195 | 83.4 | 77.3 | 87.9 | 204 | 45.4 | 38.4 | 52.1 |

| 1980–1984 | 138 | 80.2 | 72.5 | 86.0 | 235 | 45.1 | 38.7 | 51.3 | |

| 1985–1989 | 153 | 78.8 | 71.4 | 84.5 | 238 | 54.0 | 47.4 | 60.2 | |

| 1990–1994 | 150 | 69.0 | 60.8 | 75.7 | 257 | 66.7 | 60.5 | 72.1 | |

| 1995–1999 | 137 | 73.4 | 65.1 | 80.0 | 277 | 64.0 | 58.0 | 69.4 | |

| 2000–2006 | 264 | 84.4 | 78.2 | 89.4 | 422 | 73.3 | 67.5 | 78.2 | |

| Stage** | Localized | 492 | 92.2 | 89.2 | 94.3 | 205 | 92.0 | 87.1 | 95.1 |

| Regional | 225 | 79.5 | 73.3 | 84.4 | 334 | 79.7 | 74.7 | 83.8 | |

| Distant | 108 | 35.3 | 26.1 | 44.6 | 833 | 45.4 | 41.7 | 48.9 | |

| Unstaged | 95 | 49.0 | 38.3 | 58.9 | 246 | 53.2 | 46.6 | 59.3 | |

| Blank*** | 117 | 89.6 | 82.3 | 93.9 | 15 | $ | $ | $ | |

| Grade | Well differentiated | 54 | 89.5 | 76.6 | 95.5 | 42 | 82.7 | 67.3 | 91.4 |

| Moderately differentiated | 23 | 80.6 | 56.1 | 92.3 | 22 | 58.8 | 35.7 | 76.0 | |

| Poorly differentiated | 88 | 55.7 | 44.4 | 65.7 | 250 | 73.1 | 65.7 | 79.2 | |

| Undifferentiated | 66 | 24.3 | 14.6 | 35.4 | 165 | 61.1 | 52.8 | 68.3 | |

| Unknown | 806 | 85.6 | 82.8 | 87.9 | 1,154 | 56.1 | 53.1 | 59.0 | |

Observed survival rates are unadjusted; $ Number of cases is too small to provide stable survival rates;

American Indian/Alaska Natives, Asian/Pacific Islanders, Other unspecified & Unknown;

One additional case involved the prostate and was staged as localized/regional;

“The SEER Program strives to make all Localized/Regional/Distant stage variables consistent for all cancer sites for the appropriate years. However, there are certain site/year combinations where this is not possible” (http://seer.cancer.gov/seerstat/variables/seer/yr1973_2005/lrd_stage/)

The major contrast shown in Table V was the near doubling of 5-year survival rates in neuroblastoma comparing 1975 to 2006 (45.4% to 73.3% respectively), while overall 5-year survival in NETs was stable over this interval from 83.4% in 1975 to 84.4% in 2006. The result is that the survival rates for these two tumors are now similar with 84% overall 5-year survival for NETs and 73% for neuroblastoma. As expected, survival for both tumors was inversely related to tumor stage. Poorly differentiated and undifferentiated NETs had markedly lower 5-year survival rates than the corresponding grade of neuroblastomas.

The higher incidence of neuroblastoma together with the longer overall survival rates for NETs resulted in a similar prevalence values for NETs compared to neuroblastoma as shown in Table VI. This indicates that equal numbers of patients with neuroendocrine tumors and neuroblastoma should be receiving long term follow-up. The prevalence values mirrored the incidence rates in terms of male to female ratio within each tumor type. As expected, the NET prevalence was highest in the 30–59 years age group compared to the 0–29 years age group for neuroblastoma.

Table VI.

31-year limited prevalence data for neuroendocrine tumors versus neuroblastoma as of January 1, 2006, 0–29 year old persons at diagnosis, US population, 1975–2006

| Variables | NETs Estimated Crude Prevalence Count | Neuroblastoma Estimated Crude Prevalence Count | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Male | Female | ||

| Age groups | 0–9 yrs | 0 | 0 | 2,002 | 1931 |

| 10–19 yrs | 149 | 162 | 1,800 | 1518 | |

| 20–29 yrs | 752 | 960 | 1,087 | 1092 | |

| 30–39 yrs | 938 | 1324 | 228 | 233 | |

| 40–49 yrs | 630 | 1439 | 12 | 41 | |

| 50–60 yrs | 256 | 1114 | 6 | 10 | |

| Total | 0–60 yrs | 2725 | 4999 | 5,135 | 4825 |

| US population | 7724 | 9960 | |||

Multivariate survival analysis was conducted for NETs to assess the joint effect of some standard prognostic factors (location, histology and stage) on the hazard of death (Table VII). Adjusting for age, location was found to be highly significant (p-value < 0.001). Breast, ovary and lung, compared to the appendix affected death significantly with breast 8.5 times higher (p value=< 0.0001), ovary 5.5 times higher (p value=0.005), and lung 3 times higher (p value=0.04). After age adjustment, histology was also highly significant (p-value < 0.0001). Small cell histology, compared to medullary carcinoma and carcinoid, had a hazard ratio 12 times higher (p value=< 0.0001) and was clearly the NET histology with the poorest prognosis. After age adjustment, stage was also highly significant (p-value = 0.0016). Compared to local stage, distant stage had a hazard ratio 3 times higher (p value=0.0009) and regional stage 1.6 times higher (p value=0.03).

Table VII.

Multivariate Cox Regression analysis for neuroendocrine tumors by age, location, stage & histology variables, 0–29 years, 9 Standard SEER Registries, 1975–2006

| Parameter* | Hazards ratio | 95% Hazard ratio confidence limits | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower limit | Upper limit | |||

| Location | Breast | 8.5 | 3.4 | 21.7 |

| Hindgut | 1.4 | 0.3 | 7.5 | |

| Lung | 2.9 | 1.1 | 8.5 | |

| Ovary | 5.5 | 1.7 | 18.1 | |

| Histology | Small cell carcinoma, NOS | 11.9 | 6.1 | 23.5 |

| Stage | Distant | 3.0 | 1.6 | 5.7 |

| Regional | 1.6 | 1.04 | 2.6 | |

| Unstaged | 0.2 | 0.03 | 1.5 | |

| Blank | 1.3 | 0.6 | 2.8 | |

The comparison group for location is the appendix, for histology it is medullary carcinoma and carcinoid, and for stage it is localized.

DISCUSSION

NETs are considered orphan tumors in adults aged 30 years or greater, with an incidence rate of 38 per million person years and a prevalence count of 103,000 in the United States (referenced to January 1, 2004). As this study shows, NETs are even rarer in children and young adults less than 30 years of age, with an incidence rate of 2.8 per million and a prevalence count of 7724. This has resulted in a lack of standards of care as well as a paucity of clinical trials for these patients(20). This analysis of the SEER database is a first step towards providing data to support guidelines for diagnosis, treatment, and long term follow-up for these children and young adults.

The diffuse neuroendocrine system includes at least 40 different cell types, all of which are characterized by production of peptides and amines(21). Though small in absolute number in any given tissue, the peptides and amines secreted from neuroendocrine cells regulate multiple neural and endocrine pathways such as milk production, pituitary and thyroid hormone production, gonadal hormone production, as well as intestinal and pancreatic function(12;22). Though the diffuse neuroendocrine system is an efficient physiological regulatory mechanism, this same diffuse distribution contributes to the distribution of care for patients with NETs among multiple medical specialties, including pulmonary, endocrinology, gastroenterology, oncology, and surgery.

Besides the wide variety of tissues in which a NET can arise, the wide range of presenting symptoms also contributes to difficulty with early diagnosis. NETs often have a delayed diagnosis with an estimated 8–10 years from first symptoms to diagnosis(5). Flushing, diarrhea, cough and abdominal pain are vague symptoms, often occurring in healthy children and young adults, and often leaving the physician and the patient frustrated, without a diagnosis. This analysis of NETs in the 0–29 years age group confirms the multiplicity of primary sites and cell types seen in adults and confirms the need for an understanding of the diffuse neuroendocrine system in order to evaluate the vague and varied symptoms that should alert caregivers to this orphan disease.

Appendiceal carcinoid is often the NET that first comes to mind in this age group; yet, the SEER data presented here indicate that NETs of the lung and breast are actually diagnosed more often than appendiceal tumors in young people. It has previously been recognized that NET is the leading primary malignant lung tumor in children(9). This SEER analysis demonstrates that medullary carcinoma of the breast is more common than medullary thyroid carcinoma in females under the age of 30 years. Similarly, small cell carcinoma of the ovary is more common than small cell lung cancer in this young age group. The heretofore unrecognized two-fold higher incidence of NETs in young women is explained by this SEER data demonstrating breast, cervix, and ovary as leading anatomical sites for NETs in young people. The small cell malignancies overall have a poor prognosis(23–27), and our data demonstrate only a 24% 5-year survival for young women with small cell carcinoma of the genital tract. Advances in neuroblastoma survival have been made by identifying the highest risk groups and directing both basic and clinical research toward development of new diagnostic and therapeutic options for these high risk tumors. This SEER database analysis has identified small cell carcinoma of the female genital tract as an extremely high risk group among young people with neuroendocrine tumors.

These SEER incidence data demonstrate that less than 50% of children and young adults with NETs are diagnosed prior to regional and distant spread of disease; an additional 5% of these patients have metastatic disease with an unknown primary site. Metastatic disease in the liver with no identifiable primary was the second most common presentation of NETs in children diagnosed at the MD Anderson Cancer Center(9). The diffuse nature of the neuroendocrine system(1) and the generally long interval from onset of symptoms to diagnosis in NETs(5) may account for the late diagnoses and may also help to explain why survival rates are not improving for young people with NETs. The long term survival rates that we were able to determine in this analysis of the SEER database as in most survival studies in the literature are only 5 years which is short in terms of the life of a child or young adult. While patients with NETs are often assumed to have longer survival rates than many other cancer survivors, data documenting this are difficult to find. A single institution study found the 10-year survival in adults with pancreatic NETs to be 40% if the patients were treated with somatostatin analogs and 22% without this supportive care (28). Modlin and Sandor found that 5-year survival for invasive and metastatic disease is 34, 41, and 55% for patients with primary pancreatic, lung, and small intestinal NETs, respectively (29). A 30-year survival in a single patient has been reported in the literature (30). Thus, a 5-year survival rate of 84% in children and young adults may be misleading as most of these patients will have an indolent disease course with late metastases and death prior to 40 years of age unless improved diagnostic, therapeutic, and follow-up guidelines are developed for these orphan tumors.

Overall, our analysis of the SEER data covering the 1975–2006 incidence, survival, and prevalence of NETs in the 0–29 year age group indicates that NETs constitute a significant cancer threat to young people in the United States. The establishment of centers of care for children and young adults diagnosed with NETs is recommended with the expectation that earlier diagnosis utilizing multiple imaging modalities(31) and biochemical markers(32) coupled with targeted therapies and life-long follow-up, will decrease the incidence of metastatic disease and improve both quantity and quality of life for these young people. Given that adolescents and young adults have seen no improvement in cancer survival rates for decades(33), establishment of NET centers of care could also serve as a model for development of care guidelines to bridge the gap between pediatric oncology and adult oncology.

Acknowledgments

Pournima Navalkele was a student at the University of Iowa School of Public Health. Research funded by R21 CA134198 (M. Sue O’Dorisio) and the University of Iowa Neuroendocrine Tumor Fund (M. Sue O’Dorisio and Thomas M. O’Dorisio).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement: None of above authors has any relevant conflict of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Modlin IM, Champaneria MC, Bornschein J, Kidd M. Evolution of the diffuse neuroendocrine system--clear cells and cloudy origins. Neuroendocrinology. 2006;84:69–82. doi: 10.1159/000096997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yao JC, Hassan M, Phan A, et al. One hundred years after “carcinoid”: epidemiology of and prognostic factors for neuroendocrine tumors in 35,825 cases in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3063–3072. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.4377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Faggiano A, Mansueto G, Ferolla P, et al. Diagnostic and prognostic implications of the World Health Organization classification of neuroendocrine tumors. J Endocrinol Invest. 2008;31:216–223. doi: 10.1007/BF03345593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hassan MM, Phan A, Li D, et al. Risk factors associated with neuroendocrine tumors: A U.S.-based case-control study. Int J Cancer. 2008;123:867–873. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vinik AI, Moattari AR. Treatment of endocrine tumors of the pancreas. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 1989;18:483–518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Corpron CA, Black CT, Herzog CE, et al. A half century of experience with carcinoid tumors in children. Am J Surg. 1995;170:606–608. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(99)80025-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ladd AP, Grosfeld JL. Gastrointestinal tumors in children and adolescents. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2006;15:37–47. doi: 10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2005.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khanna G, O’Dorisio MS, Menda Y, et al. Gastroenteropancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumors in Children and Young Adults. Pediatric Radiology. 2008;38:251–259. doi: 10.1007/s00247-007-0564-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Broaddus RR, Herzog CE, Hicks MJ. Neuroendocrine tumors (carcinoid and neuroendocrine carcinoma) presenting at extra-appendiceal sites in childhood and adolescence. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2003;127:1200–1203. doi: 10.5858/2003-127-1200-NTCANC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parham DM. Neuroectodermal and neuroendocrine tumors principally seen in children. Am J Clin Pathol. 2001;115 (Suppl):S113–S128. doi: 10.1309/2A98-GPDN-EN87-5J0L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spunt SL, Pratt CB, Rao BN, et al. Childhood carcinoid tumors: the St Jude Children’s Research Hospital experience. J Pediatr Surg. 2000;35:1282–1286. doi: 10.1053/jpsu.2000.9297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Papotti M, Rosas R, Longo M, et al. Spectrum of neuroendocrine tumors in non-endocrine organs. Pathologica. 2005;97:215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brodeur GM, Maris JM. Neuroblastoma. In: Pizzo PA, Poplack DG, editors. Principles and Practice of Pediatric Oncology. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001. pp. 895–937. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ambros PF, Ambros IM, Brodeur GM, et al. International consensus for neuroblastoma molecular diagnostics: report from the International Neuroblastoma Risk Group (INRG) Biology Committee. Br J Cancer. 2009;100:1471–1482. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Software: Surveillance Research Program. National Cancer Institute SEER*Stat software. ( www.seer.cancer.gov/seerstat) version 6.5.2. Data: Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program ( www.seer.cancer.gov) SEER*Stat Database: Incidence - SEER 9 Regs Limited-Use, Nov 2008 Sub (1973–2006) <Katrina/Rita Population Adjustment> - Linked To County Attributes -Total U.S., 1969–2006 Counties, National Cancer Institute, DCCPS, Surveillance Research Program, Cancer Statistics Branch, released April 2009, based on the November 2008 submission.

- 16.Tiwari RC, et al. Statistical Methods in Medical Research. 2006;15:547–569. doi: 10.1177/0962280206070621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.SEER Coding and Staging Manuals. National Cancer Institute; Surveillance Research Program. ( www.seer.cancer.gov/tools/codingmanuals/index.html) [Google Scholar]

- 18.Software: Joinpoint Regression Program, Version 3.3.1. Statistical Research and Applications Branch, National Cancer Institute; Apr, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 19.http://www.census.gov/main/www/cen2000.html

- 20.Modlin IM, Moss SF, Chung DC, et al. Priorities for improving the management of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:1282–1289. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pearse AGE, Polak JM. The diffuse endocrine system and the APUD concept. In: Bloom SR, editor. Gut Hormones. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1987. p. 33. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Modlin IM, Oberg K, Chung DC, et al. Gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumours. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:61–72. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70410-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Linda A, Zuiani C, Girometti R, et al. Unusual malignant tumors of the breast: MRI features and pathologic correlation. Eur J Radiol. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2009.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rakha EA, Aleskandarany M, El-Sayed ME, et al. The prognostic significance of inflammation and medullary histological type in invasive carcinoma of the breast. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:1780–1787. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2009.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim YM, Jung MH, Kim DY, et al. Small cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix: clinicopathologic study of 20 cases in a single center. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2009;30:539–542. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zivanovic O, Leitao MM, Jr, Park KJ, et al. Small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the cervix: Analysis of outcome, recurrence pattern and the impact of platinum-based combination chemotherapy. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;112:590–593. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martinez-Borges AR, Petty JK, Hurt G, et al. Familial small cell carcinoma of the ovary. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2009;53:1334–1336. doi: 10.1002/pbc.22184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Townsend A, Price T, Yeend S, et al. Metastatic Carcinoid Tumor: Changing Patterns of Care Over Two Decades. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;44(3):195–199. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181a9f10a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Modlin IM, Sandor A. An analysis of 8305 cases of carcinoid tumors. Cancer. 1997 Feb 15;79(4):813–29. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19970215)79:4<813::aid-cncr19>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kałuzny M, Bolanowski M, Sukiennik-Kujawa M, et al. Long-term survival and nearly asymptomatic course of carcinoid tumour with multiple metastases (treated by surgery, chemotherapy, (90)Y-DOTATATE, and LAR octreotide analogue): a case report. Endokrynol Pol. 2009 Sep-Oct;60(5):401–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.O’Dorisio MS, Khanna G, Bushnell D. Combining anatomic and molecularly targeted imaging in the diagnosis and surveillance of embryonal tumors of the nervous and endocrine systems in children. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2008;27:665–677. doi: 10.1007/s10555-008-9153-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vinik AI, Silva MP, Woltering G, et al. Biochemical testing for neuroendocrine tumors. Pancreas. 2009;38:876–889. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181bc0e77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Albritton K, Barr R, Bleyer A. The adolescence of young adult oncology. Semin Oncol. 2009;36:478–488. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2009.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]