Abstract

Objective

This cross-sectional study investigated the relationships between psychiatric and substance-related disorders, high-risk behaviors, and the onset, duration, and frequency of homelessness among homeless youth in Chicago.

Methods

Sixty-six homeless youth were recruited from two shelters in Chicago. Demographic characteristics, psychopathology, substance use, and risk behaviors were assessed for each participant.

Results

Increased frequency and duration of homeless episodes were positively correlated with higher rates of psychiatric diagnoses. Increased number of psychiatric diagnoses was positively correlated with increased high-risk behaviors. Participants with diagnoses of Current Suicidality, Manic Episodes, Obsessive Compulsive Disorder, Substance Abuse, and Psychotic Disorder had a higher chronicity of homelessness than those without diagnoses.

Conclusions

Significant differences were evident between the three time parameters, suggesting that stratification of data by different time variables may benefit homelessness research by identifying meaningful subgroups who may benefit from individualized interventions.

Keywords: Homelessness, youth, psychopathology, substance use

Adolescents constitute 12% of the total U.S. homeless population and have the highest prevalence of homelessness among all age groups, at 9–15%.1,2 This translates to an estimated 1.6 to 2 million youth who are without stable housing each night. Youth homelessness (with youth defined as a person under age 25, due to the developmental nature of this experience) is associated with an array of adverse outcomes, including poorer physical and mental health, high rates of abuse and trauma, elevated rates of substance use and high-risk sexual behaviors, irregular nutrition and sleep, poorer cognitive and academic functioning, elevated school dropout rates, and high rates of mortality, especially from suicide, trauma, and overdose.3–5

Currently, 50% of homeless youth do not escape homelessness prior to adulthood.6 Improved understanding of homeless youth risk profiles would allow service providers to more effectively identify youth who require specialized support services in order to make a transition to stable housing.7 Some researchers have specifically highlighted the need for better characterization of the differences between those who tend to be short-term, long-term, or episodically homeless,8 in order to design more effective targeted interventions.

The purpose of this study is to investigate more closely the relationships among psychiatric and substance-related disorders, high-risk behaviors, and the onset, duration, and frequency of homelessness among homeless youth in Chicago. Past studies have shown that increased cumulative time homeless correlates with increased substance use.3,9,10,21 Most of these studies have been able to distinguish between “newly” and “long-term” homeless youth, or those having experienced less or more than six months of homelessness, respectively. More detailed analytics of the chronicity of homelessness for youth populations have not been done in these studies.

Relatedly, research has demonstrated that substance-using homeless youth are more likely than their non-using peers to experience mental health problems, exacerbating the fact that homeless youth already exhibit high rates of anxiety and mood disorders at baseline.3,11 One study found that 89% of homeless 16–19 year olds met criteria for one or more mental health disorders, compared with 30% for the national population of the same age range.12 However, current research has yet to establish the relationship between length and frequency of homelessness and their impact on mental health functioning and substance use.

In relation to sexual health, studies have shown that more than six months of homelessness correlates with an earlier onset of sexual activity as well as a higher likelihood of participation in and greater length of time during which the person engaged in high-risk sexual behaviors.3,13 Consistent homelessness for six months or longer has also been associated with more HIV-risk behaviors,14 which is unsurprising in light of homeless youth’s overall higher likelihood of multiple sexual partners and greater risk of STIs compared with national norms.4,15,16 HIV/AIDS prevalence among U.S. homeless and runaway youth is estimated to be up to 11.5%.17,18 Nonetheless, some studies have failed to find a correlation between length of homelessness and sexual risk behaviors,15 indicating a need for further research.

Finally, age of onset of first homeless episode seems to play a role, as early experience of homelessness, specifically by running away from home, is associated with elevated rates of high risk behaviors, including survival sex, theft, and using and selling drugs.19 Younger homeless youth are also at greater likelihood of having experienced domestic violence and to continue experiencing violence when homeless. In addition, earlier age of homelessness is associated with an elevated risk of depression and adverse mental health sequelae.19

Yet, due to the transient nature of homeless populations, ethical issues surrounding their study, as well as a lack of funding for research, prevention, and intervention, there are significant knowledge gaps about the cycles of violence and developmental trauma faced by these youth.3 A more specific understanding of length of time and frequency of homelessness in relation to mental health, along with substance use and high-risk sexual behaviors, will better inform the development of interventions. In this study of Chicago homeless youth, it is hypothesized that rates of psychiatric disorders, substance use disorders, and other self-reported high-risk behaviors will be correlated with increased duration, frequency, and early onset of homelessness episodes.

Methods

Recruitment

Sixty-six homeless youth were recruited from two shelters in Chicago: the Night Ministry and Teen Living Program. To meet criteria for homelessness in our study, youth had to meet the U.S. Department of Education definition of homelessness. The Night Ministry (NM) is a non-profit organization providing short-term and emergency housing to youth ages 14–20 in West Town. Case managers at this site were responsible for initiating contact with potential participants. Teen Living Program (TLP), located on the south side of Chicago in Bronzeville, provides transitional housing and services to help youth ages 17–24 acquire stable housing and self-sufficiency. Recruitment at TLP involved a research team member visiting the shelter weekly and asking residents if they would be interested in participating in a study about homeless youth.

Human subject protections

A research team member met with all interested youth to provide a full description of the study, and written informed consent was obtained. The research protocol was approved by the University of Chicago Institutional Review Board.

Eligibility

Participants were 18–24 year-old homeless youth living in Chicago without “a fixed, regular, and adequate nighttime residence.”20 Youth younger than 18 were not recruited because underage youth in Illinois are removed from homeless shelters by the Department of Child & Family Services and placed in foster care. Individuals of any ethnic or cultural groups, or gender or gender-identification were considered eligible for this study. Youth with IQ <55 were not considered capable of providing informed consent, and their data were not included in the study.

Data collection

Data collection used for these analyses occurred between March 2011 and July 2012. Data collection was cross sectional in design. Each participant was administered a demographic questionnaire chronicling race/ethnicity, sex, age, family background, and the onset, number and length of homeless episodes in the youth’s life, as well as other assessments detailed below.

Measures

The experience of homelessness was assessed in five time measures that were self-reported by the participants: 1. age at first homeless episode, 2. number of homeless episodes in the last year, 3. length of the longest homeless episode in participant’s lifetime, 4. length of the current homeless episode, 5. number of homeless episodes in participant’s lifetime.

A trained research team member administered the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview, version 6 (M.I.N.I. 6.0). The M.I.N.I. allows for the assessment of DSM-IV-TR and ICD-10 major psychiatric diagnoses and substance use disorders via a semi-structured interview. It has high reliability (kappa 0.88–1.0) and validity (kappa usually greater than 0.5), and its design allows for rapid exclusion of diagnoses by using pertinent negatives22.

An amended version of the CDC’s 2011 National Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) was completed independently by the youth. This survey inquires about sexual risk behaviors and substance use patterns. The findings from the CDC YRBS were transformed to produce risk scales. There is no perfect method of creating a risk scale, which is essentially the conversion of ordinal and dichotomous variables into continuous, scale variables. The YRBS has a mix of dichotomous and ordinal variables. Given that the groups of questions in each risk area (smoking, cannabis, alcohol, sex) do provide insight and even some quantification of risky behaviors, it seemed appropriate to scale the variables for analytical purposes. Subjective YRBS questions were excluded from this analysis. Five risk scales were produced: Smoking, Alcohol, Marijuana, Hard Drug, and Sexual Behaviors (see Appendix for a full explanation of how the scales were created).

Finally, the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (WASI-I) was administered to measure verbal, performance, and full scale IQ scores, which allowed the research team to obtain an initial index of current level of cognitive functioning and to ascertain whether or not the participant met exclusion criteria for the study. In addition to the WASI, further neuropsychological data was collected from patients in a second session of testing, the results of which were unrelated to this analysis.

Compensation

Participants were given a $10 gift card to local stores in return for completing the 1–1.5 hour interview. If the participant completed a neuropsychological evaluation in a second session, he/she also received a more detailed assessment of psychiatric status, neurocognitive function, and academic strengths and weaknesses, which could be used to demonstrate need for additional supportive services at the youth shelter or in an academic setting if the participant chose to share it.

Analytic strategy

First, an examination of Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests and Q-Q plots were used to determine normality of the risk and psychopathology data. Because they were not normally distributed, non-parametric analyses were used for all analysis.

Spearman’s rho, which is used to calculate correlations in non-parametric data, was used to analyze relationships between the three time variables, as well as to identify correlations between the time variables and the results of each of the risk scales.

Next, Spearman’s rho was also utilized to examine the relationship between the time variables and psychopathology. The total number of M.I.N.I. diagnoses per participant (both with and without alcohol and drug abuse or dependence included) was correlated with each of the time variables.

Last, analysis was performed to identify significant differences in means of time variables for each individual psychiatric diagnosis. For example, the mean total number of homeless episodes for those who met criteria for Major Depressive Disorder was compared with the mean total number of homeless episodes for those who did not meet criteria for the disorder; and Fisher’s exact test and Mann-Whitney rank-sum tests were used to determine whether the difference in frequency or mean rank was significant, respectively. Appropriate effect size measures were determined next. This analysis was performed for each psychiatric diagnosis and the means of each of the three time variables.

Results

Demographic characteristics of the study sample are described in Table 1. Sixty-six youth were recruited from two Chicago homeless shelters. The mean age was 19.3 years old, with no participants between 22 and 24, and 56.1% female. The average highest grade completed was eleventh grade. The mean IQ was 86, with a range of 61–117. The race and ethnicity breakdown included 80.3% African American, 3.0% White, 3.0% Latino, 7.6% Multiracial, and 6.1% Other. Prevalence rates of major psychiatric disorders among the sample are listed in Table 2. Overall, 81.5% of youth met criteria for at least one psychiatric disorder, 66.2% for a mood disorder, 34.4% for an anxiety disorder, and 7.9% for a psychotic disorder. (see Appendix for specific diagnoses included within each category). Prevalence rates of risk behaviors among the sample are shown in Table 3. Overall, 34.8% were daily cigarette smokers, 48.5% had recently consumed alcohol, 73% had used marijuana at some point throughout their lifetime, and 31.7% had not used a condom during the most recent sexual encounter. The number of participants (N) is included in each table; any omitted responses were not included in calculations.

Table 1.

Study population characteristics

| Demographic data, N=66 | |

|---|---|

| Average age, yrs. | 19.26 (SD 0.87) |

| Age range, yrs. | 18–21 |

| Female, % | 56.1 |

| Male, % | 43.9 |

| African American, % | 80.3 |

| Caucasian, % | 3.0 |

| Latino, % | 3.0 |

| Multiracial, % | 7.6 |

| Other, % | 6.1 |

| Highest grade completed, avg. | 11.2 (SD 1.5) |

| IQ, avg. | 86 (Range 61–117) |

| Experiences of homelessness | |

| Age at first experience, avg. | 16.4 (SD 3.1) |

| No. of times in past year, avg. | 1.9 (SD 1.8) |

| Length of longest experience, avg. | 15.2 mos. (SD 15.7 mos.) |

| Current length of homelessness, avg. | 10.6 mos. (SD 13.7 mos.) |

| Total lifetime times homeless | |

| 1–3 (%) | 87.9 |

| 4–6 (%) | 7.6 |

| 7–9 (%) | 3.0 |

| >9 (%) | 1.5 |

Table 2.

Prevalence of Psychiatric Disorders in Youth, N = 66

| Diagnosis | N | % ** |

|---|---|---|

| Any psychiatric disorder* | 53 | 81.5 |

| Any mood disorder | 43 | 66.2 |

| Any anxiety disorder | 22 | 34.4 |

| Any psychotic disorder | 5 | 7.9 |

| Major Depressive Episode | 35 | 53.8 |

| Major Depressive Episode, Current | 15 | 23.1 |

| Major Depressive Episode, Past | 29 | 44.6 |

| Major Depressive Episode, Recurrent | 13 | 20.0 |

| Suicidality, Current | 41 | 63.1 |

| Manic Episode | 12 | 19.0 |

| Manic Episode, Current | 5 | 7.9 |

| Manic Episode, Past | 11 | 17.5 |

| Hypomanic Episode Current | 0 | 0 |

| Hypomanic Episode, Past | 8 | 12.7 |

| Hypomanic Symptoms, Current | 2 | 3.2 |

| Hypomanic Symptoms, Past | 6 | 9.5 |

| Panic Disorder w/Agoraphobia Current | 2 | 3.1 |

| Agoraphobia w/o history of Panic Disorder | 10 | 15.6 |

| Social Phobia Current (Social Anxiety Disorder) | 8 | 12.5 |

| Social Phobia Current (Generalization) | 3 | 4.6 |

| Obsessive Compulsive Disorder | 5 | 7.8 |

| Posttraumatic Stress Disorder | 8 | 12.5 |

| Psychotic Disorder | 3 | 4.8 |

| Mood Disorder, with psychotic features | 2 | 3.1 |

| Anorexia Nervosa | 0 | 0 |

| Bulimia Nervosa | 2 | 3.1 |

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder | 7 | 11.1 |

| Anti-Social Personality Disorder | 14 | 21.9 |

| Substance Dependence (non-alcohol) | 10 | 15.6 |

| Substance Abuse (non-alcohol) | 8 | 12.5 |

| Alcohol Dependence | 5 | 7.8 |

| Alcohol Abuse | 7 | 10.9 |

| Comorbid Substance or Alcohol Abuse and/or Dependence | 11 | 18.0 |

Any positive screen on M.I.N.I

Percentages are calculated based upon all respondents, and so any questions unanswered or not applicable are left out of calculations.

Table 3.

Prevalence of Self-reported High Risk Behaviors in Youth, N = 66

| Self-reported risk behaviors | N | % |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Has tried cigarette smoking | 48 | 72.7 |

|

| ||

| Daily cigarette smoker (lifetime) | 23 | 34.8 |

|

| ||

| Age of first alcohol use | ||

| Never | 11 | 17.4 |

| <8 | 2 | 3.2 |

| 9–10 | 5 | 7.9 |

| 11–12 | 7 | 11.1 |

| 13–14 | 6 | 9.5 |

| 15–16 | 14 | 22.2 |

| >17 | 18 | 28.6 |

|

| ||

| Recent* alcohol use | 32 | 48.5 |

|

| ||

| Recently* consumed >5 drinks of alcohol in a row | 14 | 22.2 |

|

| ||

| Marijuana use | 46 | 73.0 |

|

| ||

| Age of first marijuana use | ||

| Never | 15 | 23.8 |

| <8 | 2 | 3.2 |

| 9–10 | 2 | 3.2 |

| 11–12 | 3 | 4.8 |

| 13–14 | 12 | 19.0 |

| 15–16 | 10 | 15.9 |

| >17 | 19 | 30.2 |

|

| ||

| Recent* marijuana use | 29 | 46.0 |

|

| ||

| Cocaine use | 1 | 1.6 |

|

| ||

| Inhalant use | 1 | 1.6 |

|

| ||

| Heroin use | 0 | 0 |

|

| ||

| Methamphetamine use | 0 | 0 |

|

| ||

| Ecstasy use | 11 | 17.5 |

|

| ||

| Hallucinogenic drugs use | 3 | 4.8 |

|

| ||

| Steroid pill/shot use | 1 | 1.6 |

|

| ||

| Prescription drug misuse | 8 | 12.7 |

|

| ||

| Injection drug use | 1 | 1.6 |

|

| ||

| Has engaged in sexual intercourse | 55 | 87.3 |

|

| ||

| Age of first sexual intercourse | ||

| Never | 4 | 6.3 |

| <12 | 3 | 4.8 |

| 12–13 | 12 | 19 |

| 14–15 | 23 | 36.5 |

| 16 | 6 | 9.5 |

| 17 or older | 15 | 23.8 |

|

| ||

| Number of lifetime partners | ||

| 0 | 4 | 6.3 |

| 1 | 3 | 4.8 |

| 2–3 | 15 | 23.8 |

| 4–5 | 9 | 14.2 |

| 6 or more | 32 | 50.8 |

|

| ||

| Average number of sexual partners in the past 3 months | ||

| 0 | 14 | 22.2 |

| 1 | 27 | 42.9 |

| 2–3 | 16 | 25.4 |

| 4–5 | 4 | 6.4 |

| 6 or more | 2 | 3.2 |

|

| ||

| Recent* drug or alcohol use prior to intercourse | 18 | 28.6 |

|

| ||

| Condom use during most recent instance of sexual intercourse | 43 | 68.3 |

|

| ||

| Has engaged in exchange sex | 7 | 11.1 |

|

| ||

| Sex with high-risk partner | 1 | 1.6 |

|

| ||

| Recent* sexual experience with unknown partner | 6 | 9.5 |

“Recent” indicates within the past 30 days

Table 4 presents data from the three time variables (Age at First Homeless Episode, Longest Homeless Episode, and Total Lifetime Homeless Episodes) compared with total number of psychiatric diagnoses per participant, both with and without alcohol and drug abuse or dependence included. Non-parametric analysis was used, as variables were either ordinal or not normally distributed according to Kolmogorov-Smirnov analysis.

Table 4.

Non-parametric correlations between Homeless Time Variables and Total Number of M.I.N.I. Diagnoses Per Participant (Spearman’s rho)

| Age at first homeless experience | Total lifetime homeless episodes | Longest episode of homelessness (mos). | Number of M.I.N.I. diagnoses | Number of M.I.N.I. diagnoses except Alcohol or Substance Abuse/Dependence | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at first homeless experience | 1.000 | −.507** | −.546** | −0.229 | −.250 |

| Total lifetime homeless episodes | −.507** | 1.000 | .229 | .319** | .288* |

| Longest episode of homelessness (mos.) | −.546** | .229 | 1.000 | .279* | .249* |

| Number of M.I.N.I. diagnoses | −0.229 | .319** | .279* | 1.000 | .976** |

| Number of M.I.N.I. diagnoses except Alcohol or Substance Abuse/Dependence | −0.187 | .288* | .249* | .976** | 1.000 |

Correlation is significant at the p<0.05 level (2-tailed).

Correlation is significant at the p<0.01 level (2-tailed).

Age of onset of first homeless episode was negatively correlated with the number of total lifetime homeless episodes and length of homeless episode. This means that the younger the individual was when he/she became homeless, the higher the incidence of total lifetime homeless episodes and the longer the average length per episode. Age of onset of first homeless episode failed to correlate with the presence of psychiatric diagnoses even when substance use disorders were not included.

Lifetime homeless episodes were positively correlated with the number of psychiatric diagnoses, both with and without substance use disorders. The length of the longest homeless episode was positively correlated with the number of psychiatric diagnoses, and this relationship continued to be significant even when substance use disorders were not included in the analysis.

Table 5 presents the correlations between the time variables and risk behaviors. Younger age at first homeless episode was positively correlated with Smoking Scale risk behaviors, and increased total lifetime homeless episodes was significantly correlated with increased risk behaviors on the Smoking Scale, Marijuana Scale, and Hard Drug Scale. Increased length of longest homeless episode did not result in a significant correlation with the Risk Behavior scale data, although increased number of MINI diagnoses was positively correlated with all five of the risk scales.

Table 5.

Non-parametric correlations between Homeless Time Variables and Behavior Risk Scales (Spearman’s rho)

| Smoking Risk Sum | Alcohol Risk Sum | Marijuana Risk Sum | Hard Drug Risk Sum | Sexual Behaviors Risk Sum | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at first homeless experience | −.251* | −.084 | −.145 | −.205 | −.091 |

| Total lifetime homeless episodes | .405** | .239 | .284* | .267* | .235 |

| Longest episode of homelessness (mos.) | .090 | .010 | .038 | .055 | .086 |

| Number of M.I.N.I. diagnoses | .324** | .387** | .439** | .440** | .435** |

Correlation is significant at the p<0.01 level (2-tailed)

Last, analysis was performed to compare time variables to specific psychiatric diagnoses. Table 6 presents total lifetime homeless episodes data, showing that participants with MINI diagnoses of Current Suicidality, Manic Episodes, Obsessive Compulsive Disorder, Substance Abuse, and Psychotic Disorder have significantly higher numbers of total lifetime homeless episodes. Effect sizes indicated that the difference between those with and without psychotic disorders was moderate, and the differences between all other disorders was small.

Table 6.

Significant Associations between Total lifetime homeless episodes and Outcome Variables (Fisher exact test and Cramer’s V)

| Outcome Variable | N | p | Cramer’s V |

|---|---|---|---|

| MINI Current Suicidality | 64 | 0.027 | 0.36 |

| MINI Manic Episodes | 62 | 0.025 | 0.36 |

| MINI Obsessive Compulsive Disorder | 63 | 0.019 | 0.43 |

| MINI Substance Abuse | 63 | 0.025 | 0.40 |

| MINI Psychotic Disorder | 62 | 0.035 | 0.40 |

Similarly, Table 7 shows that receiving MINI diagnoses of Current, Past or Lifetime Major Depressive Episodes, Generalized Anxiety Disorder, Social Phobia, and Substance Abuse was associated with increased length of longest homeless episode. Among these, Current Major Depressive Episode and Generalized Anxiety Disorder showed moderate effect sizes with other diagnoses having small effects.

Table 7.

Significant Associations between Longest Episode of Homelessness and Psychiatric Diagnoses (Mann-Whitney rank-sum test)

| Outcome Variable | Z | p | r |

|---|---|---|---|

| MINI Major Depressive Episodes, Past | −2.186 | 0.03 | − 0.27 |

| MINI Major Depressive Episodes, Lifetime | − 2.132 | 0.03 | − 0.27 |

| MINI Hypomanic Symptoms, Past | −2.132 | 0.03 | −0.27 |

| MINI Social Phobia, Current | −3.150 | 0.002 | − 0.40 |

| MINI Social Phobia, Current Generalized | − 3.150 | 0.002 | − 0.40 |

| MINI Substance Abuse | −2.031 | 0.04 | −0.26 |

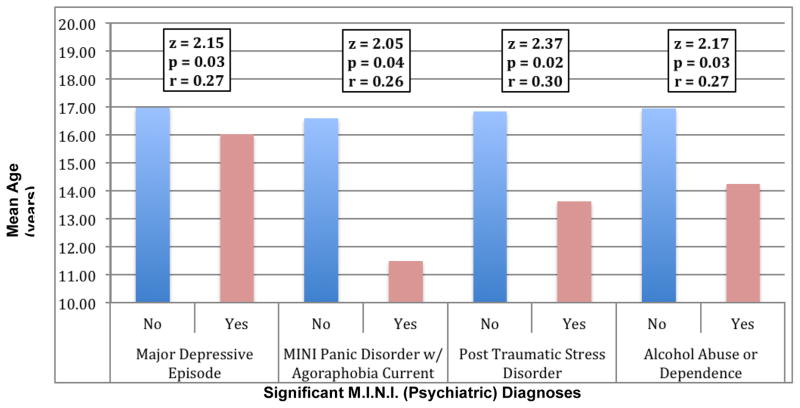

Figure 1 shows the results for mean age at first homeless episode for all those with and without the four MINI Diagnoses that emerged as statistically significant: Major Depressive Episode, Panic Disorder with Agoraphobia, Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, and Alcohol Abuse or Dependence.

Figure 1.

Significant differences in mean age of first homeless episode for four adverse mental health outcomes

Z, p, and r values are reported for Mann-Whitney U analysis. r > 0.1 indicates a small effect, r > 0.3 indicates a medium effect, and r > 0.5 indicates a large effect.

Discussion

Similar to other studies of homeless youth, the preliminary results in this study population demonstrated high overall prevalence of psychiatric disorders and self-reported high-risk behaviors, from substance use (most commonly alcohol, marijuana, ecstasy, and misuse of prescription drugs) to sexual high-risk behaviors. Hard drug use report rates were lower than in other studies, which could be due to underreporting, economic barriers, or the fact that both shelters we worked with are long-term facilities, and so for some youth, increased time “homeless” may have meant more time in supported housing with treatment and health education/prevention services available. Future work that includes more youth who are living on the streets—through mobile devices as a vehicle for research, for example—may yield different results.

Time variables

The three major time variables were chosen in order to examine the effects of homelessness early in life, long-term versus short-term duration of homelessness, and the instability of frequent homeless episodes. These parameters are related; those homeless at earlier ages are more likely to have experienced more frequent and longer episodes of homelessness.

Age at first homeless episode

Younger age of first homeless episode was the only time variable not significantly correlated with increased prevalence of multiple psychiatric illnesses in this preliminary data; however, closer examination of individual disorders (Major Depressive Disorder, Panic Disorder with Agoraphobia, and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder) showed that their occurrence was correlated with younger age of first episode of homelessness. In some respects, this is not surprising, given the traumatic histories that many of these youth have encountered. One participant, for example, identified panic attacks and agoraphobic symptoms following previous experiences of violence at the hands of gang members on the streets. With fewer years of life in supportive environments to develop effective coping skills for such trauma, younger homeless youth appear at greater risk for these psychiatric pathologies. Moreover, given the relation between younger age of first homeless episode and increased MINI Alcohol Abuse/Dependence, they also appear at risk for the development of alternative, unhealthy coping mechanisms.

Analysis of risk scale results also yielded specific associations between early age of onset and smoking risk behaviors, as well as an increased (but non-significant) association between prescription drug misuse and early age of homelessness, which will merit further exploration.

Longest homeless episode

Increased length of homelessness was significantly correlated with a greater number of psychiatric diagnoses, consistent with findings from Slesnick and colleagues1, and others. Specifically, those who met criteria for Major Depressive Episodes (Past and Lifetime), Social Phobia (Current and Generalized) and Substance Abuse had significantly longer lifetime homeless episodes. The cross-sectional nature of our study makes it impossible to determine whether these psychopathologies are a cause or a result of the increased time homeless.

Total lifetime homeless episodes

Results supported the hypothesis that youth who are homeless with greater frequency are different from the majority of youth who have only experienced a couple of homeless episodes. While increased lifetime homeless episodes was positively correlated with higher prevalence of psychiatric illnesses, these correlate disorders were diverse, spanning a variety of psychopathology categories: Current Suicidality, Manic Episodes, Psychotic Disorder, Substance Abuse, and Obsessive Compulsive Disorder. These conditions, particularly the first four, may increase the likelihood of hospitalization and institutionalization, thereby providing brief respites from unstable housing. Alternatively, they may be particularly volatile conditions, which improve and worsen over time, causing youth being more or less capable of staying in stable housing at different periods of their lives.

Furthermore, total lifetime episodes was the time factor most strongly correlated with higher scores on the high-risk behavior scales (smoking, marijuana, and hard drugs). There are various ways to interpret these data. Given that increased number of MINI diagnoses were correlated with increased risk scores on all of the scales, it seems most likely that risk behaviors are both coping mechanisms and products of impaired judgment caused by psychiatric diagnoses.

There were several limitations in this study, including the cross-sectional design, which limits conclusions about causation, as well as the small sample size. Our sample was drawn from two residential youth programs whose standards for acceptance might artificially narrow the population. Future study using mobile vans will be helpful in broadening our scope to include more street-based youth. Additionally, all of the survey tools are based on self-report, which is subject to recall bias. As data collection is still in process, we anticipate that larger sample sizes will better compensate for bias.

Conclusion

These preliminary data from a Chicago homeless youth population identified high prevalence of psychiatric diagnoses and high-risk behaviors, confirming expectations based on previous studies—although not without unexpected findings to prompt future study. Specifically, the significant differences shown between the long-term and frequently episodically homeless suggest that stratification of the data by frequency as well as time is needed in future research in order to characterize more accurately the homeless youth population overall, providing richer context and targets for interventions. We foresee the development of a temporal risk index after further replication of these findings. This index ideally would allow frontline intake workers and case manager to enter data such as age of first homelessness, episodes of homelessness, and length of periods of homelessness and enable rapid screening of high-yield domains that correlate with the risk index such as suicidality, mood disorders, anxiety disorders, and substance use disorders.

Acknowledgments

During the time of this research, Anne Castro was supported by a medical student fellowship from the Campaign for America’s Kids (CFAK) of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry (AACAP). Ashley Ford was supported by a Jeanne Spurlock Minority Medical Student Research Fellowship in Substance Abuse and Addiction from AACAP and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). From 2011–13, Dr. Karnik was supported by Grant Number KL2TR000431 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS). Additional support was provided by the University of Chicago and Rush University. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of AACAP, University of Chicago, Rush University, NIDA, NCATS or the National Institutes of Health.

Appendix

The Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) has five sections that ask questions pertaining to tobacco, alcohol, cannabis, and hard drug use as well as sex behaviors. Five risk scales were created based on these five categories using questions about age at first use/experience and frequency of use/experience. For example, high risk sexual behaviors include younger age at sexual debut, higher number of lifetime sexual partners, use of alcohol or drugs prior to sexual intercourse, not using a condom with sexual use, trading sex for money, food, drugs, or shelter, having sex with a partner who has a known risk (HIV, STD, etc.), or not knowing one’s sexual partner. Responses to each question were quantified by assigning points to each response option such that successively riskier behaviors had successively higher values. Specifically, for every question the possible responses were ranked from least risky to most risky, and then assigned a point value starting at 1 for the least risky behavior and increasing by increments of one for each successively riskier behavior. The risk score for each scale was then calculated by summing the points of the participant’s selected responses to the questions in each category. Some questions were not included in the scales because they were more descriptive in nature and did not provide information about the degree of risk-taking.

The following questions were used to create the risk scales. The scores were then converted so that they all start at 0.

| Smoking Risk: Questions 1–4, 6–11 |

| Possible Point Range 10–55 |

| Converted to 0–45 |

| Alcohol Risk: Questions 12–15, 17 |

| Possible Point Range 5–35 |

| Converted to 0–30 |

| Cannabis Risk: Questions 18–21 |

| Possible Point Range 4–26 |

| Converted to 0–22 |

| Hard Drug Risk: Questions 11–59 |

| Possible Point Range 11–59 |

| Converted to 0–48 |

| Sexual Behaviors Risk: Questions 33–41, 42a, 44a, 44b, 44c |

| Possible Point Range 13–52 |

| Converted to 0–39 |

Next, in analyzing results of the M.I.N.I. to determine prevalence of psychopathology, three major categories were considered: Mood Disorders, Anxiety Disorders, and Psychotic Disorders. The specific diagnoses grouped under “Mood Disorders” included Major Depressive Episode (Past, Present, or Recurrent) and Mood Disorder with Psychotic features. The specific diagnoses grouped under “Anxiety Disorders” included Panic Disorder, Agoraphobia, Social Phobia, Post-traumatic Stress Disorder, Obsessive Compulsive Disorder, and Generalized Anxiety disorder. The specific diagnoses grouped under “Psychotic disorders” included Psychotic Disorder and Mood Disorder with psychotic features.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors have no interests to disclose in relation to the research described here.

References

- 1.Slesnick N, Kang MJ, Bonomi AE, Prestopnik JL. Six- and twelve-month outcomes among homeless youth accessing therapy and case management services through an urban drop-in center. Health services research. 2008;43(1 Pt 1):211–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2007.00755.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nyamathi A, Hudson A, Greengold B, Leake B. Characteristics of homeless youth who use cocaine and methamphetamine. Am J Addict. 2012;21(3):243–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2012.00233.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Edidin JP, Ganim Z, Hunter SJ, Karnik NS. The Mental and Physical Health of Homeless Youth: A Literature Review. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s10578-011-0270-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Naranbhai V, Abdool Karim Q, Meyer-Weitz A. Interventions to modify sexual risk behaviours for preventing HIV in homeless youth. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(1):CD007501. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007501.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kulik DM, Gaetz S, Crowe C, Ford-Jones EL. Homeless youth’s overwhelming health burden: A review of the literature. Paediatr Child Health. 2011;16(6):e43–7. doi: 10.1093/pch/16.6.e43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hein LC. Survival strategies of male homeless adolescents. J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc. 2011;17(4):274–82. doi: 10.1177/1078390311407913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caton CLM, Dominguez B, Schanzer B, et al. Risk factors for long-term homelessness: findings from a longitudinal study of first-time homeless single adults. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(10):1753–9. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.063321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kertesz SG, Larson MJ, Horton NJ, Winter M, Saitz R, Samet JH. Homeless chronicity and health-related quality of life trajectories among adults with addictions. Med Care. 2005;43(6):574–85. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000163652.91463.b4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kipke MD, Montgomery SB, Simon TR, Iverson EF. “Substance abuse” disorders among runaway and homeless youth. Substance use & misuse. 1997;32(7–8):969–86. doi: 10.3109/10826089709055866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferguson KM, Jun J, Bender K, Thompson S, Pollio D. A comparison of addiction and transience among street youth: Los Angeles, California, Austin, Texas, and St. Louis, Missouri Community Ment Health J. 2010;46(3):296–307. doi: 10.1007/s10597-009-9264-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morrell-Bellai T, Goering PN, Boydell KM. Becoming and remaining homeless: a qualitative investigation. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2000;21(6):581–604. doi: 10.1080/01612840050110290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Whitbeck LB, Johnson KD, Hoyt DR, Cauce AM. Mental disorder and comorbidity among runaway and homeless adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2004;35(2):132–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rew L, Grady M, Whittaker TA, Bowman K. Interaction of duration of homelessness and gender on adolescent sexual health indicators. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2008;40(2):109–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2008.00214.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Slesnick N, Bartle-Haring S, Dashora P, Kang MJ, Aukward E. Predictors of Homelessness Among Street Living Youth. J Youth Adolesc. 2008;37(4):465–74. doi: 10.1007/s10964-007-9188-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosenthal D, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Batterham P, Mallett S, Rice E, Milburn NG. Housing stability over two years and HIV risk among newly homeless youth. AIDS Behav. 2007;11(6):831–41. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9235-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Steele RW, Ramgoolam A, Evans J. Health services for homeless adolescents. Semin Pediatr Infect Dis. 2003;14(1):38–42. doi: 10.1053/spid.2003.127216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rice E, Monro W, Barman-Adhikari A, Young SD. Internet use, social networking, and HIV/AIDS risk for homeless adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2010;47(6):610–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Milburn NG, Iribarren FJ, Rice E, et al. A family intervention to reduce sexual risk behavior, substance use, and delinquency among newly homeless youth. J Adolesc Health. 2012;50(4):358–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berdahl TA, Hoyt DR, Whitbeck LB. Predictors of first mental health service utilization among homeless and runaway adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2005;37(2):145–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.The McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act [Internet] 2001 Available from: http://www2.ed.gov/policy/elsec/leg/esea02/pg116.html.

- 21.Kirst MJ, Frederick T, Erickson PG. Concurrent mental health and substance use problems among street-involved youth. Int J of Ment Health and Addict. 2011;9(5):543–553. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sheehan DV, et al. Reliability and Validity of the MINI International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): According to the SCID-P. European Psychiatry. 1997;12:232–241. [Google Scholar]