Abstract

Objectives

To assess the occurrence, risk factors, morbidity and mortality associated with lower extremity (LE) ulcers in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

Methods

Retrospective review of Olmsted County, Minnesota residents who first fulfilled 1987 American College of Rheumatology criteria for RA in 1980–2007 with follow-up to death, migration or April 2012. Only LE ulcers that developed after the diagnosis of RA were included.

Results

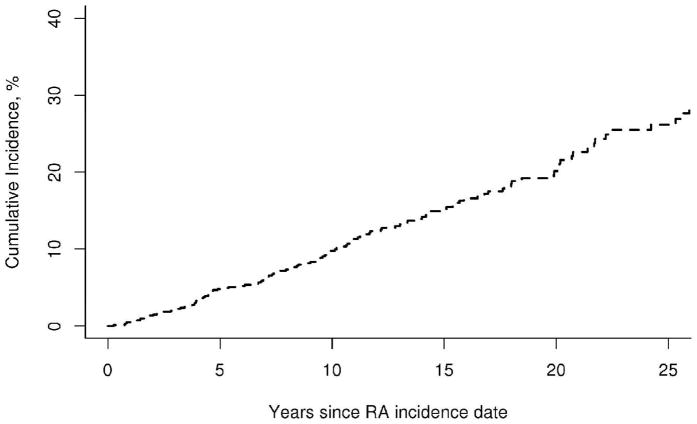

The study included 813 patients with 9771 total person-years of follow-up. 125 patients developed LE ulcers (total of 171 episodes), corresponding to a rate of occurrence of 1.8 episodes per 100 person-years (95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.5, 2.0 per 100 person-years). The cumulative incidence of first LE ulcers was 4.8% at 5 years after diagnosis of RA and increased to 26.2% by 25 years. Median time for the LE ulcer to heal was 30 days. Ten of 171 (6%) episodes led to amputation. LE ulcers in RA were associated with increased mortality (HR 2.42; 95% CI: 1.71, 3.42) adjusted for age, sex and calendar year. Risk factors for LE ulcers included age (HR 1.73 per 10 year increase; 95% CI: 1.47, 2.04); rheumatoid factor positivity (HR 1.63; 95% CI: 1.05, 2.53); presence of rheumatoid nodules (HR 2.14; 95% CI: 1.39, 3.31); and venous thromboembolism (HR 2.16; 95% CI: 1.07, 4.36).

Conclusions

LE ulcers are common among patients with RA. The cumulative incidence increased by 1% per year. A significant number require amputation. Patients with RA who have LE ulcers are at two-fold risk for premature mortality.

Key indexing terms: rheumatoid arthritis, incidence, lower extremity ulcer

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a common systemic inflammatory disorder which primarily affects the joints (1). Lower extremity (LE) ulcer is one of the known common complications of long standing RA. Based upon self-report, the point prevalence of foot ulceration in RA has been estimated to be 3.13% (2). An overall prevalence of 10.08% was reported in a study from the United Kingdom (UK), as opposed to a prevalence of chronic leg ulcers in 1% of the general adult population (2, 3). In contrast to diabetic foot ulcers, little is known regarding the magnitude and morbidity associated with LE ulcers in RA. We aimed to assess the occurrence, risk factors, morbidity and mortality associated with lower extremity ulcers in RA.

Materials and Methods

Study setting

This is a retrospective population-based study performed using resources of the Rochester Epidemiology Project (REP) medical record linkage system (4). The REP allows virtually complete access to medical records from all community medical providers including Mayo Clinic, Olmsted Medical Center and their affiliated hospitals, local nursing homes, and the few private practitioners in Olmsted County, MN. The uniqueness of the REP and its advantages in performing population-based studies in rheumatic diseases has been previously described (5, 6).

Study subjects and data collection

Cases of RA incident between January 1, 1980 and December 31, 2007 among residents of Olmsted County, Minnesota were previously identified using the REP. RA was defined according to the 1987 American College of Rheumatology criteria as previously described (7, 8). All medical records of patients with RA were retrospectively reviewed and longitudinally followed until death, migration or April 2012. Medical records were reviewed for episodes of LE ulcers. For the purpose of the study, LE ulcer was defined as a full thickness skin defect occurring in isolation on or below the mid-level of thighs supported by physician diagnosis, clinical history and physical exam. LE ulcers due to surgery, biopsy, burns, animal bites, in grown toe nail, toe nail removal, abrasion, cellulitis, foreign body or herpes zoster were excluded. Further categorization of the LE ulcer according to ischemic, pressure, venous, vasculitic and diabetic neuropathic was done based on physician diagnosis supported by available information such as ankle-brachial index, peripheral arterial angiogram, duplex ultrasound, location of the ulcer, history of trauma, biopsy results or impression of rheumatologist, podiatrist, wound care or vascular medicine specialist. Smoking status at the onset of LE ulcer was obtained. The use of antirheumatic medications at the onset of the LE ulcer including disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs; i.e., methotrexate, hydroxychloroquine and other DMARDs and biologic response modifiers), systemic glucocorticosteroids, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs, including COX-2 inhibitors) was recorded.

Information regarding ulcer treatment including conservative, medical or surgical measures was obtained. Information regarding RA disease in this cohort of patients was already collected for previous epidemiological studies (8, 9). This included results of clinically performed tests for rheumatoid factor and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), persistently high ESR (≥ 3 ESR values ≥ 60 mm/hour with ≥ 30 days between measurements), large joint swelling, joint erosions/destructive changes on radiographs, joint surgery (i.e., synovectomy and arthroplasty), and severe extraarticular manifestations of RA (defined according to the Malmö criteria) (10).

Statistical methods

Descriptive statistics (means, percentages, etc.) were used to summarize characteristics of the patients. Person-year methods were used to estimate the rate of occurrence of LE ulcers. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals (95% CI) for the rates were calculated assuming the observed LE ulcers follow a Poisson distribution. Cumulative incidence of LE ulcers adjusted for the competing risk of death was estimated (11). These methods are similar to Kaplan-Meier method with censoring of patients who are still alive at last follow-up. However, patients who die before experiencing LE ulcers are appropriately accounted for to avoid the overestimation of the rate of occurrence of LE ulcers, which can happen if such subjects are simply censored.

Cox proportional hazards models were used to assess the association of risk factors with LE ulcers. These models were adjusted for age, sex and calendar year of RA incidence. Time-dependent covariates were used to model risk factors that developed over time (e.g., joint surgery, rheumatoid nodules, severe extra-articular manifestations, medication exposures), allowing patients to be modeled as “unexposed” to the risk factor during the follow-up time prior to development of the risk factor, then change to “exposed” following development of the risk factor. Since risk factor data was collected previously, it was only available through 12/31/2008 for patients who were still alive and living in Olmsted County on that date. Therefore, follow-up was truncated at the last follow-up of available risk factor data for the risk factor analyses, and LE ulcers occurring after this data were not included in these analyses.

The influence of LE ulcers on mortality was examined using Cox models with time-dependent covariates for the first LE ulcer occurring during followup. First, the influence of LE ulcers on mortality was assessed in a model adjusted for age, sex, and calendar year of RA incidence. Then the influence of LE ulcers was assessed in a model that was additionally adjusted for factors known to be related to mortality: BMI, history of smoking, RF positivity, severe extra-articular manifestations, comorbidities (diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, venous thromboembolism, renal disease, liver disease, dementia, and cancer), history of alcohol abuse, exposure to glucocorticosteroids, DMARDs and/or biologic agents. This additional list of adjustors was obtained from a previous study (12) and augmented with factors found to be associated with the occurrence of LE ulcers, in an attempt to provide a comprehensive adjustment while avoiding issues of bias related to variable selection. Poisson regression models were used to examine trends in LE ulcers over time. Both calendar time and disease duration were examined. In these models, smoothing splines were used to allow examination of potential non-linear time trends, and the models were adjusted for age and sex.

Results

The study included 813 patients with incident RA between January 1, 1980 and December 31, 2007. The characteristics of the 813 patients with RA are listed in table 1. All patients were 18 years or older. There were 556 women (68%) and 257 men (32%). The mean age at diagnosis of RA was 56 years. The average length of follow up was 12.0 years with 9771 total person years of follow up for the cohort. Rheumatoid factor was positive in 537 (66%) patients. The mean ESR at diagnosis of RA was 24.8 mm/hour.

Table 1.

Characteristics of 813 patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA)

| Characteristics | Mean (± SD) or n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age at RA incidence, years | 55.9 (± 15.7) |

| Female | 556 (68) |

| Length of follow-up, years | 12.0 (± 7.2) |

| Smoking Status at RA incidence | |

| Never | 364 (45) |

| Current | 178 (22) |

| Former | 271 (33) |

| Rheumatoid nodules | 267 (33) |

| ESR at RA incidence, mm/1hr | 24.8 (± 20.5) |

| Rheumatoid factor positive | 537 (66) |

ESR = Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (Westergren); SD = standard deviation

LE ulcer occurred in 125 patients with a total of 171 episodes, which corresponds to a rate of occurrence of 1.8 episodes per 100 person-years (95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.5, 2.0 per 100 person-years). The rate of occurrence of a first LE ulcer was 1.4 per 100 person-years (95% CI: 1.1, 1.6 per 100 person-years). Among patients with a first LE ulcer, the rate of occurrence of a second LE ulcer was substantially increased (7.9 per 100 person-years; 95% CI: 5.5, 10.9). The cumulative incidence of first LE ulcers in RA patients was 4.8% (95% CI: 3.2%, 6.4%) at 5 years after diagnosis of RA and increased to 26.2% (95% CI: 21.3%, 31.1%) by 25 years (see figure 1). The constant rate of increase of 1% per year in the cumulative incidence of first LE ulcers suggests that there was no association between RA disease duration and the occurrence of LE ulcers. There was no apparent change in the rate of development of LE ulcers over the range of RA disease duration (p=0.71). Analyses of disease duration trends in rate of LE ulcers by type revealed a significant decline in the rates of venous LE ulcers (p=0.007), which appeared to be most common in the first few years after RA incidence. A marginal increase in the rate of pressure LE ulcers over disease duration (p=0.12) was also noted.

Figure 1.

Cumulative incidence of foot ulcers among 813 patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA)

The LE ulcers were located between ankle and knee in 58 episodes (34%), tip of toes in 46 episodes (27%), plantar metatarsal in 18 episodes (11%), heel in 18 episodes (11%), lateral malleolus in 18 episodes (11%), and medial malleolus in 13 episodes (8%).

Comorbidities included varicose veins in 32 episodes (19%), diabetes mellitus in 42 episodes (25%), coronary artery disease in 54 episodes (32%) and peripheral arterial disease in 33 episodes (19%). Pressure ulcers were noted in 62 episodes (36%), ischemic ulcers in 22 episodes (18%), venous ulcers in 20 episodes (12%), neuropathic ulcer in 18 episodes (11%), vasculitic ulcers in 2 episodes (1%). Etiology was unclear or unknown in 10 episodes (6%). A history of current smoking was noted in 15 episodes (9%) at diagnosis of LE ulcer (see table 2). A history of recent local trauma was noted in 69 episodes (40%).

Table 2.

Characteristics of 171 lower extremity ulcer episodes in 125 patients with rheumatoid arthritis

| Characteristics | N (%), unless specified |

|---|---|

| Time to heal in days, median (25th, 75th percentile) | 30.5 (14.0, 115.0) |

| Current smokers at diagnosis of LE ulcer | 15 (9) |

| History of recent local trauma | 69 (40) |

| Comorbidities | |

| Varicose veins | 32 (19) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 42 (25) |

| Coronary artery disease | 54 (32) |

| Peripheral artery disease | 33 (19) |

| Location of lover extremity ulcer | |

| Between ankle and knee | 58 (34) |

| Tip of toes | 46 (27) |

| Plantar/metatarsal | 18 (11) |

| Heel | 18 (11) |

| Lateral malleolus | 18 (11) |

| Medial malleolus | 13 (8) |

| Other location | 19 (11) |

| Type of lower extremity ulcer | |

| Pressure ulcer | 62 (36) |

| Ischemic ulcer | 22 (18) |

| Venous ulcer | 20 (12) |

| Neuropathic ulcer | 18 (11) |

| Vasculitic (biopsy-proven) | 2 (1) |

| Traumatic ulcer | 49 (29) |

| Unknown etiology | 10 (6) |

| Anti-rheumatic medications used at onset of lower extremity ulcer ulcer | |

| Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs | 70 (41) |

| Glucocorticosteroids | 79 (46) |

| Methotrexate | 63 (37) |

| Other disease modifying antirheumatic drugs | 49 (29) |

| Biologics | 12 (7) |

Vascular imaging was performed in 49 episodes (29%). Biopsy of the ulcer was done in 9 episodes (5%). Some of the episodes fell under more than one category of type of ulcer. Anti-rheumatic medications used at the onset of LE ulcer included NSAIDs in 70 episodes (41%), glucocorticosteroids in 79 episodes (46%), methotrexate in 63 episodes (37%), leflunomide in 9 episodes (5%), infliximab in 4 episodes (2%), etanercept in 5 episodes (3%), rituximab in 3 episodes (2%), and cyclophosphamide in 2 episodes (1%). At the onset of LE ulcer, infliximab was stopped in 1 episode and etanercept in 2 episodes.

LE ulcer treatment included conservative methods such as elevation of foot, cleaning, moist sterile dressing and/or compression bandages in almost all cases (169 episodes). The LE ulcers healed spontaneously with conservative therapy in 18 episodes (11%). Antibiotic was used in 147 (86%) episodes. Topical glucocorticosteroid therapy was used in 4 episodes (2%). Surgical skin grafting was done in 5 episodes (3%); surgical debridement in 44 episodes (26%). Surgical limb amputation was required in 10 episodes (6%). The mean time for the ulcers to heal was 120 days [standard deviation (SD) 290; median time 30 days (25th percentile 14, 75th percentile 115)].

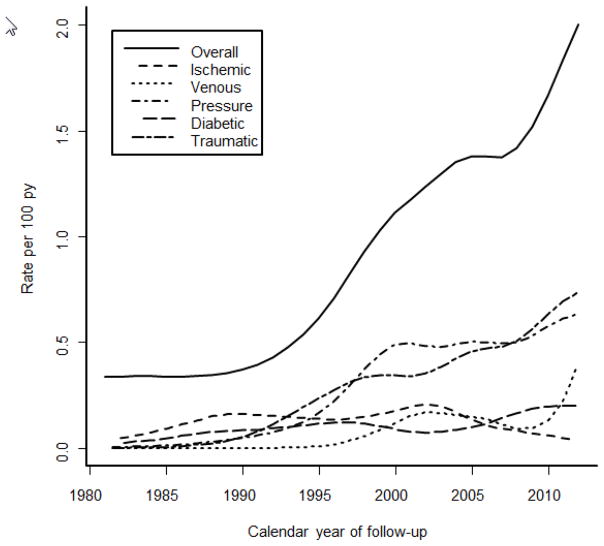

The incidence of LE ulcers in RA increased among patients with incident RA in the 1995–2007 period compared to those with incident RA in the 1980–1994 period (hazard ratio [HR] 2.14; 95% CI: 1.27, 3.58; table 3). The incidence of LE ulcers increased 6% per year over the range of calendar years of follow-up (rate ratio: 1.06 per year, 95% CI: 1.03, 1.10, p<0.001; Figure 2). Analyses of time trends by type of LE ulcer revealed significant increases in the rates of venous (p=0.027), pressure (p=0.002) and traumatic (p=0.003) LE ulcers, but no trends over time in ischemic (p=0.30) or diabetic (p=0.53) LE ulcers.

Table 3.

Risk factors for lower extremity ulcers in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA)

| Variable | Value* | Hazard Ratio [95% confidence interval (CI)] |

|---|---|---|

| At RA incidence | ||

| Age (per 10 year increase) | 55.9 (± 15.7) | 1.73 (1.47, 2.04)** |

| Sex, female | 556 (68) | 1.22 (0.77, 1.94) |

| Calendar year of RA incidence in 1995–2007 (vs. 1980–1994) | 464 (57) | 2.14 (1.27, 3.58)** |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) at RA incidence date (per 10 mm/1hr increase) | 32.7 (±25.7) | 1.05 (0.94, 1.18) |

| Highest ESR in 1st year of RA (per 10 mm/1hr increase) | 105 (13) | 1.03 (0.94, 1.12) |

| Rheumatoid factor positive | 537 (66) | 1.63 (1.05, 2.53)** |

| Current smoker | 178 (22) | 1.46 (0.92, 2.34) |

| Ever smoker | 449 (55) | 1.02 (0.66, 1.58) |

| At RA incidence or at any time during follow-up | ||

| History of body mass index (BMI) ≥30 kg/m2 | 388 (48) | 1.12 (0.73, 1.71) |

| History of BMI<20 kg/m2 | 190 (23) | 1.68 (1.03, 2.75)** |

| Rheumatoid nodules | 267 (33) | 2.14 (1.39, 3.31)** |

| Radiological erosions/destructive changes | 433 (53) | 1.59 (1.03, 2.47)** |

| Severe extra-articular RA*** | 90 (11) | 1.96 (1.11, 3.47)** |

| Large joint swelling | 639 (79) | 1.58 (0.89, 2.82) |

| Ever 3 ESR ≥60 mm/hour | 105 (13) | 2.39 (1.40, 4.07)** |

| Arthroplasty or synovectomy | 190 (23) | 1.36 (0.86, 2.15) |

| Ever exposure to medications | ||

| Methotrexate | 469 (58) | 1.58 (1.01, 2.47)** |

| Hydroxychloroquine | 480 (59) | 1.09 (0.70, 1.70) |

| Other DMARDs | 258 (32) | 1.36 (0.84, 2.19) |

| Biologic agents | 137 (17) | 1.95 (0.99, 3.83) |

| Systemic glucocorticosteroids | 627 (77) | 1.54 (0.93, 2.54) |

| Comorbidities | ||

| Hypertension | 709 (87) | 1.94 (0.76, 4.93) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 154 (19) | 1.56 (0.96, 2.51) |

| Cardiovascular disease | 231 (28) | 1.51 (0.92, 2.47) |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 28 (3) | 1.29 (0.52, 3.25) |

| Venous thromboembolism | 69 (8) | 2.16 (1.07, 4.36)** |

mean (± standard deviation) or n(%)

statistically significant at p< .05

as defined in reference 10

Figure 2.

Rate of LE ulcer incidence overall and by type of LE ulcer by calendar year of follow-up among patients with incident rheumatoid arthritis.

The following were identified as risk factors for LE ulcers in RA: age; rheumatoid factor positivity, history of BMI<20 kg/m2, presence of rheumatoid nodules, radiological erosions/destructive changes, ESR ≥ 60 mm per hour on three occasions, and severe extra-articular RA. Venous thromboembolism was also significantly associated with the development of LE ulcers, and several other comorbidities (diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease) had elevated hazard ratios, but did not reach statistical significance. Regarding medications, methotrexate exposure was significantly associated with the development of LE ulcers, and both biologic agents and glucocorticosteroids demonstrated elevated risks that did not reach statistical significance.

During follow-up 229 patients died. LE ulcers in RA were associated with an increased mortality rate (HR: 2.42; 95% CI: 1.71, 3.42) adjusted for age, sex and calendar year. This increased risk persisted following additional adjustment for RA disease characteristics and comorbidities known to influence mortality in RA (HR: 2.38; 95% CI: 1.63, 3.46), indicating the influence of LE ulcers on mortality in RA may not be explained by other factors.

Discussion

Though the association of LE ulcer with RA was recognized by the 1950s (13, 14), LE ulcers in RA continue to be a major concern with prolonged wound healing and morbidity, but are understudied as opposed to, for example, diabetic foot ulcers (2).

A postal survey of all patients with RA under the care of rheumatologists at the Bradford teaching hospitals in the UK estimated an overall prevalence of foot ulcers as 9.73% with a point prevalence of 3.39% in RA (2). This postal survey was not a population-based study and had 78% response rate and excluded ulcers above the level of malleolus. Thirty four percent of the episodes of LE ulcers in our study were located above the level of malleolus. The other common locations of ulceration noted in our study were tips of toes and plantar aspect of metatarsal heads which is consistent with the UK study (2). More than one site in the lower extremity was involved in a significant proportion of patients in our study. Pressure ulcers were the most common type in our study, followed by ischemic ulcers. This may be related to the fact that RA is associated with subclinical peripheral arterial disease (15). Immobility, reduced ankle movement and venous thrombosis can predispose the patients with RA to calf pump failure which is associated with formation of venous ulcers, which are usually located over the medial malleolus and often associated with pedal edema (16).

Only 1% of the episodes had biopsy proven rheumatoid vasculitis (RV) in our study. Since majority of the patients did not undergo biopsy, it is unclear whether vasculitis was underdiagnosed. In an institution-based study on lower extremity ulcers in RA, 16 of 366 patients had active LE ulcers in a 3 year period and 12 of the 16 underwent biopsy. Of these 12, 3 had histopathological evidence of vasculitis (17). RV typically presents as a painful deep cutaneous ulcer with a punched out appearance in the area of medial or lateral malleoli. Medium vessel vasculitis could also potentially lead to digital ischemia and gangrene (18). In a small prospective study from Sweden, 11 of 19 patients with RA and chronic leg ulcers had histopathological evidence of vasculitis (19). However, this study included exclusively patients with non-healing leg ulcers for >2 months duration.

We assessed risk factors for LE ulcers in RA, although a formal cohort study with a control group was not performed. Age and venous thromboembolism were identified as risk factors for LE ulcers in RA which is not surprising as they are known risk factors for LE ulcers in general population. It is unclear if increased disease activity of RA is associated with LE ulcer though disease severity indicators, such as presence of rheumatoid nodules, ESR ≥ 60 mm per hour on three occasions and presence of extra-articular features were identified as risk factors. Other factors such as deformities secondary to RA, and reduced mobility of these patients may also play a role in the development and healing of the LE ulcers.

A preliminary investigation in UK with a small sample population compared 15 patients with RA and foot ulcer with 66 control RA patients without foot ulcer and suggested that active RA disease and current glucocorticosteroid therapy were associated with foot ulcer, whereas abnormal sensation, foot deformity and raised plantar pressures were not (20). Foot deformity, ill-fitting shoes and appliances can predispose these patients to ulcers from local trauma or pressure (21).

While skin atrophy in RA with prolonged glucocorticosteroid use may predispose the skin to break or tear with minor trauma, we found a marginal association between glucocorticosteroid use and LE ulcers in our subjects, which did not reach statistical significance (22). The impact of glucocorticosteroid and other medications on the development of LE ulcers is unclear, and may be confounded by disease activity. Use of DMARDs and biologics in RA were also marginally associated with LE ulcer in our study, but these associations did not reach statistical significance. Others have reported treatment with a biological agent was associated with an increased likelihood of healing of LE ulcers in patients with RA (17). Three of the 16 patients with LE ulcers in this study (17) had biopsy proven vasculitis but it is unclear whether these results can be generalized as the sample size was small. Vasculitis was less common in LE ulcers in patients with RA in another institution-based retrospective study of hospitalized patients from a dermatology servicedivision (23).

The cumulative incidence of LE ulcers steadily increased by 1% every year after RA diagnosis. We found no increased risk of LE ulcers with increasing duration of RA, which is in contrast to the UK study (2). The recurrence rate was high among the patients with RA who had already experienced an episode of LE ulcer. LE ulcers occurred more frequently in recent years (1995 to 2007) than previous years (1980 to 1994). The reasons for this increase in occurrence are unclear; it cannot be excluded that improved documentation in the electronic medical records in the recent years may have affected this result.

LE ulcers may negatively impact the quality of life for the patients with RA due to their protracted course. A significant proportion of patients in our study required surgical limb amputation which emphasizes on the magnitude of morbidity in these patients. RA itself has increased risk of mortality when compared to the general population mostly attributed to increased risk of cardiovascular death (24). In our study, LE ulcers were associated with double the mortality rate in RA. This is the first study to find an association with LE ulcers and increased mortality in RA. The reasons for increased mortality are unclear and the increased risk persisted after adjusting for factors previously known to be related to mortality. Thromboembolism, one of the adjusted factors was also found to be a risk factor for LE ulcers.

The strengths of this study are that it is population -based and targets an understudied yet not uncommon problem in patients with RA. A major strength is that the study includes both nonhospitalized and hospitalized patients, so does not suffer from hospital or geographic referral bias. With the exception of a higher proportion of the working population employed in the health care industry, and correspondingly higher education levels, on the whole, results of this study utilizing the population of Olmsted County, Minnesota are generalizable to the populations of interest elsewhere.(25) Study weaknesses are those inherent in the retrospective design. Only those persons who had a medical encounter during a leg ulcer event could be identified and included. Events of leg ulcers in persons not seeking medical care for this problem or whose diagnosis was miscoded would not be captured. The wound characteristics were not well described in the charts of several of the LE ulcers. Some of the minor LE ulcers may not have been reported to the physician by the patient and hence not documented in the records.

Since the LE ulcers are a major problem for the patients with RA, a good lower extremity examination, and early diagnosis and treatment may help reduce the morbidity associated with them. Heightened awareness of this complication and on the part of patients and health care providers is vital to ulcer prevention and management. RA patients with LE ulcers need to be managed using multi-disciplinary approach involving rheumatologists, wound care nurse, podiatrist and other disciplines such as vascular medicine or dermatology as needed.

Significance and Innovation.

Lower extremity (LE) ulcers are a relatively common yet understudied complication of rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Risk factors for the occurrence of LE ulcers in RA as assessed in this first ever study in a population-based setting include age, disease severity, and history of venous thromboembolism.

LE ulcers are associated with significant morbidity including long healing time and a two-fold increased risk of premature death in patients with RA.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health, NIAMS (R01 AR46849), the Rochester Epidemiology Project (R01 AG034676 from the National Institute on Aging), and Grant Number UL1 TR000135 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS).

Footnotes

Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

References

- 1.Aletaha D, Neogi T, Silman AJ, Funovits J, Felson DT, Bingham CO, 3rd, et al. 2010 rheumatoid arthritis classification criteria: an American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(9):1580–8. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.138461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Firth J, Hale C, Helliwell P, Hill J, Nelson EA. The prevalence of foot ulceration in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59(2):200–5. doi: 10.1002/art.23335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dale JJ, Callam MJ, Ruckley CV, Harper DR, Berrey PN. Chronic ulcers of the leg: a study of prevalence in a Scottish community. Health Bull (Edinb) 1983;41(6):310– 4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.St Sauver JL, Grossardt BR, Yawn BP, Melton LJ, 3rd, Rocca WA. Use of a medical records linkage system to enumerate a dynamic population over time: the Rochester epidemiology project. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173(9):1059–68. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kremers HM, Myasoedova E, Crowson CS, Savova G, Gabriel SE, Matteson EL. The Rochester Epidemiology Project: exploiting the capabilities for population-based research in rheumatic diseases. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2011;50(1):6–15. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keq199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maradit Kremers H, Crowson CS, Gabriel SE. Rochester Epidemiology Project: a unique resource for research in the rheumatic diseases. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2004;30(4):819–34. vii. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2004.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arnett FC, Edworthy SM, Bloch DA, McShane DJ, Fries JF, Cooper NS, et al. The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1988;31(3):315–24. doi: 10.1002/art.1780310302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bacani AK, Gabriel SE, Crowson CS, Heit JA, Matteson EL. Noncardiac vascular disease in rheumatoid arthritis: increase in venous thromboembolic events? Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64(1):53–61. doi: 10.1002/art.33322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Myasoedova E, Matteson EL, Talley NJ, Crowson CS. Increased incidence and impact of upper and lower gastrointestinal events in patients with rheumatoid arthritis in Olmsted County, Minnesota: a longitudinal population-based study. J Rheumatol. 2012;39(7):1355–62. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.111311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Turesson C, Jacobsson L, Bergstrom U. Extra-articular rheumatoid arthritis: prevalence and mortality. Rheumatology (Oxford) 1999;38(7):668–74. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/38.7.668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gooley TA, Leisenring W, Crowley J, Storer BE. Estimation of failure probabilities in the presence of competing risks: new representations of old estimators. Stat Med. 1999;18(6):695–706. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19990330)18:6<695::aid-sim60>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gabriel SE, Crowson CS, Kremers HM, Doran MF, Turesson C, O’Fallon WM, et al. Survival in rheumatoid arthritis: a population-based analysis of trends over 40 years. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48(1):54–8. doi: 10.1002/art.10705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laine VA, Vainio KJ. Ulceration of the skin in rheumatoid arthritis. Acta Rheumatol Scand. 1955;1(2):113–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Allison JH, Bettley FR. Rheumatoid arthritis with chronic leg ulceration. Lancet. 1957;272(6963):288–90. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(57)90357-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stamatelopoulos KS, Kitas GD, Papamichael CM, Kyrkou K, Zampeli E, Fragiadaki K, et al. Subclinical peripheral arterial disease in rheumatoid arthritis. Atherosclerosis. 2010;212(1):305–9. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2010.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McRorie ER, Jobanputra P, Ruckley CV, Nuki G. Leg ulceration in rheumatoid arthritis. Br J Rheumatol. 1994;33(11):1078–84. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/33.11.1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shanmugam VK, DeMaria DM, Attinger CE. Lower extremity ulcers in rheumatoid arthritis: features and response to immunosuppression. Clin Rheumatol. 2011;30(6):849–53. doi: 10.1007/s10067-011-1710-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sayah A, English JC., 3rd Rheumatoid arthritis: a review of the cutaneous manifestations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53(2):191–209. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2004.07.023. quiz 10-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oien RF, Hakansson A, Hansen BU. Leg ulcers in patients with rheumatoid arthritis--a prospective study of aetiology, wound healing and pain reduction after pinch grafting. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2001;40(7):816–20. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/40.7.816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Firth J, Helliwell P, Hale C, Hill J, Nelson EA. The predictors of foot ulceration in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a preliminary investigation. Clin Rheumatol. 2008;27(11):1423–8. doi: 10.1007/s10067-008-0940-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pun YL, Barraclough DR, Muirden KD. Leg ulcers in rheumatoid arthritis. Med J Aust. 1990;153(10):585–7. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1990.tb126267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cawley MI. Vasculitis and ulceration in rheumatic diseases of the foot. Baillieres Clin Rheumatol. 1987;1(2):315–33. doi: 10.1016/s0950-3579(87)80006-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seitz CS, Berens N, Bröcker EB, Trautmann A. Leg ulceration in rheumatoid arthritis--an underreported multicausal complication with considerable morbidity: analysis of thirty-six patients and review of the literature. Dermatology. 2010;220(3):268–73. doi: 10.1159/000284583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gabriel SE. Cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in rheumatoid arthritis. Am J Med. 2008;121(10 Suppl 1):S9–14. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.St Sauver JL, Grossardt BR, Leibson CL, Yawn BP, Melton LJ, 3rd, Rocca WA. Generalizability of epidemiological findings and public health decisions: an illustration from the Rochester Epidemiology Project. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87(2):151–60. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2011.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]