Abstract

Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) is an established procedure for the complications of portal hypertension. The largest body of evidence for its use has been supported for recurrent or refractory variceal bleeding and refractory ascites. Its use has also been advocated for acute variceal bleed, hepatic hydrothorax, and hepatorenal syndrome. With the replacement of bare metal stents with polytetrafluoroethylen (PTFE) covered stents, shunt patency has improved dramatically thus improving outcomes. Therefore, reassessment of its utility, management of its complications, and understanding of various TIPS techniques is important.

Keywords: Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt, esophageal varices, ascites, hepatic hydrothorax, hepatorenal syndrome, hepatopulmonary syndrome, venoocclusive disease, Budd-Chiari syndrome

Introduction

Portal hypertension is one of the major complications of cirrhosis. It results from increased intrahepatic resistance and increased splanchnic blood flow leading to a hyperdynamic circulatory state. The transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) has been an established procedure in the treatment of the complications of portal hypertension including bleeding esophageal varices, refractory cirrhotic ascites, hepatic hydrothorax, hepatorenal and hepatopulmonary syndromes, and more recently, Budd-Chiari syndrome and veno-occlusive disease. However, despite these broad applications, refractory acute variceal hemorrhage and control of refractory cirrhotic ascites are the only two indications subjected to numerous controlled trials.

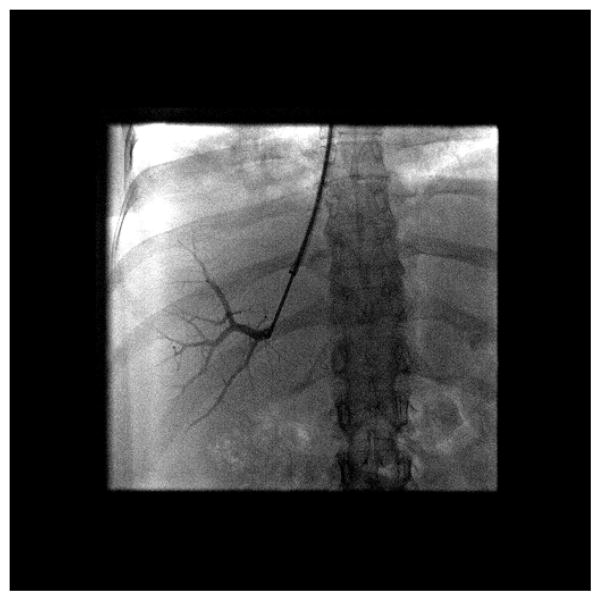

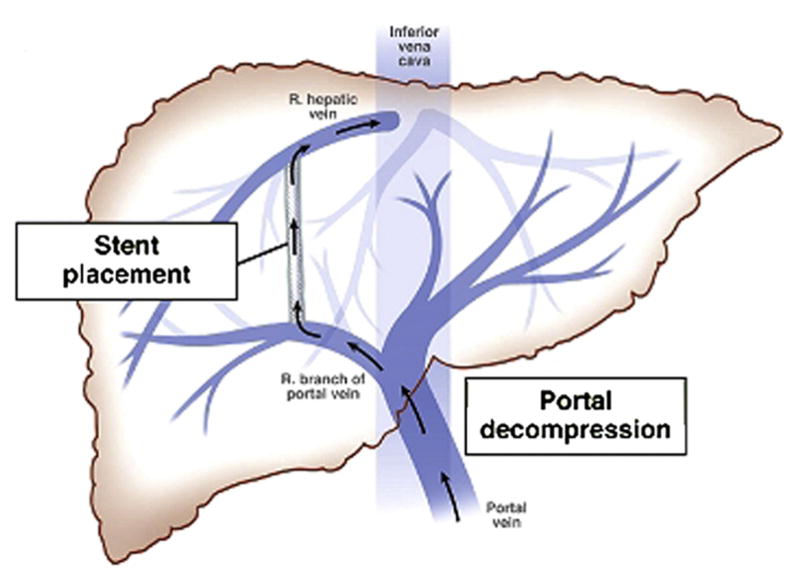

The TIPS procedure, first described by Rosch et. al1 in 1979, is a percutaneous image guided procedure in which a tract or conduit is constructed within the liver between the systemic venous system and portal system with an intent for portal decompression (Figure 1)2. The most common conduit is between the right hepatic vein (HV) and the right portal vein (PV). Patency was originally achieved by bare metal stents. The advent of Polytetrafluoroethylen (PTFE) – covered stents in recent years has dramatically improved patency rates3, and are preferred over bare metal stents4.

Figure 1. TIPS Procedure for Portal Decompression.

Adapted from Bhogal HK, Sanyal AJ. Using transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts for complications of cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9(11):936-46, with permission

In this section, we will review the indications, recommended patient selection, post-operative care, common complications and clinical outcomes related to the TIPS procedure. We also provide detailed stepwise technique to the TIPS procedure, as well as a description on advanced TIPS techniques.

Indications for TIPS Creation

TIPS reduces the portosystemic pressure gradient by shunting of blood from the PV to the HV. Its creation successfully reduces the portosytemic pressure gradient in over 90% of cases5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11. Indications for TIPS are summarized in Box 1.

Box 1. Indications for TIPS.

| INDICATION | References |

|---|---|

| Refractory or recurrent esophageal variceal hemorrhage* | 4, 7–9, 24–31 |

| Refractory Ascites* | 57–62 |

| Acute esophageal variceal bleeding | 43,44 |

| Hepatorenal syndrome (types 1 and 2) | 81–84 |

| Refractory bleeding gastric varices | 46–50 |

| Portal hypertensive gastropathy | 52, 53 |

| Hepatic hydrothorax | 70, 72–77 |

| Hepatopulmonary syndrome | 78,79 |

| Budd-Chiari syndrome | 86–89 |

| Hepatic Veno-occlusive disease | 92–95 |

Strongest evidence for TIPS based on controlled trials

Primary Prevention of Variceal Hemorrhage

The development of esophageal varices is a common complication of portal hypertension with subsequent hemorrhage representing a major cause of morbidity and mortality in patients with cirrhosis12, 13. The highest rate of development occurs in Child–Turcotte–Pugh (CTP) class B and C disease14 with an increasing risk for hemorrhage occurring in larger varices (5% for small varices and 15% for large varices15), appearance of red-whale marks11, and severity of disease (CTP class B and C). Currently beta blockers and endoscopic variceal ligation (EVL) are considered the best approach for the primary prevention for variceal hemorrhage. There are no trials to date comparing TIPS to other forms of therapy for prevention of variceal hemorrhage. Thus in the absence of evidence in light of its risks (hepatic encephalopathy, procedural complications), TIPS is not indicated for primary prevention for variceal hemorrhage.

Acute Variceal Bleeding

The use of TIPS in the setting of acute variceal hemorrhage is limited. In study by Monescillo et al, 116 cirrhotic patients were randomized within 24 hours of acute variceal hemorrhage to either receive endoscopic sclerotherapy or TIPS procedure based on HVPG of less than 20 or more respectively16. Patients who received early TIPS were found to have reduced treatment failure rates as well as better inhospital and 1-year survival. In a similar multi-center center study, comparing TIPS with PTFE-covered stents versus medical therapy with propranolol/nadolol and EVL, early use of TIPS (within 72 hours of randomization) was found have lower rates of re-bleeding with 3% in the early TIPS group and 45% in the pharmacotherapy plus EVL group17. Furthermore, survival at 1-year was significantly better in the TIPS group at 86% vs. 61 % in the pharmacotherapy plus EVL. The above studies suggest that if early risk stratification can be performed (via measurement of HVPG), early TIPS insertion could improve overall outcomes for patients who present with an acute variceal bleed.

Refractory Acute Variceal Bleeding

Combined treatment with EVL, prophylactic antibiotics, and vasoactive drugs is the suggested standard of care for the treatment for acute esophageal bleeding12. Patients who survive an initial episode of variceal hemorrhage are at a high risk for re-bleeding (over 60% at 1 year18). Factors that contribute to recurrent hemorrhage include severity of liver disease, severity of initial hemorrhage, presence of encephalopathy, impaired renal function, and increasing age19, 20, 21, 22, 23. In addition, patients with a hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG) greater than 20mm Hg are likely to have severe or recurrent bleeding, and are more likely to fail initial medical or endoscopic therapy24.

Numerous randomized controlled trials have compared the use of TIPS with endoscopic therapy for refractory or recurrent variceal bleeding 4, 7, 8, 9, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32. The results of multiple meta-analysis (Table 133, 34, 35, 36) of TIPS compared to various forms of endoscopic therapies has shown significant decrease in the risk of recurrent bleeding after the insertion of TIPS. Mortality rates were found to be similar between the endoscopy and TIPS groups, though the development of post-treatment hepatic encephalopathy (HE) was almost twofold in the TIPS group.

Table 1.

TIPS versus Endoscopic Treatment in Secondary Prophylaxis for Vacriceal Bleeding: Results from Multiple Meta-Analysis.

| Study Findings | References | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Luca et al., 199932 | Papatheodoridis et. al, 199933 | Burroughs and Vangeli, 200234 | Zheng et al, 200835 | |

|

| ||||

| No. of Pts | 750 | 811 | 948 | 883 |

| No. of Randomized Trials | 11 | 11 | 13 | 12 |

| No. of TIPS | 372 | 403 | 472 | 440 |

| No. Endoscopic Therapies

|

378 | 408 | 476 | 443 |

| Recurrent Bleeding | ||||

| TIPS, no. (%) | 81 (21) | 76 (18.9) | 88 (18.6) | 86 (19) |

| Endoscopic Therapy, no. (%) | 196 (52) | 190 (46.6) | 210 (44.1) | 194 (43.8) |

| NNT with TIPS

|

3.3 | 4 | 4 | Not Reported |

| Post-Treatment Encephalopthy | ||||

| TIPS, no. (%) | 119 (35) | 126 (34.0) | 134 (28.4) | 148 (33.6) |

| Endoscopic Therapy, no. (%)

|

65 (19) | 70 (18.7) | 83 (17.3) | 86 (19.4) |

| Mortality | ||||

| TIPS, no. (%) | 109 (28) | 110 (27.3) | 130 (27.5) | 111 (25.2) |

| Endoscopic Therapy, no. (%) | 98 (26) | 108 (26.5) | 118 (24.8) | 98 (22.1) |

NNT – Number Needed to Treat

TIPS, transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt

TIPS has also been compared to pharmacotherapy37 for the prevention of recurrent variceal hemorrhage. In a prospective, randomized controlled trial, a total of 91 cirrhotic patients (CPT B and C) who survived their first variceal hemorrhage were randomized to receive TIPS (n of 47) or pharmacotherapy (n of 44, to receive propranolol plus isosorbide-5-mononitrate). With a mean follow up of 15 months, re-bleeding rates were 39% and 17% in the pharmacotherapy and TIPS groups respectively. Survival was the same in both groups (72%); however, the authors noted improved CPT class in pharmacotherapy group (72%) versus the TIPS group (45%).

Overall, many of the aforementioned trials included bare metal stents (versus PTFE-covered stents) and endoscopic therapy mostly consisted of sclerotherapy (versus EVL); thus the literature should be kept in perspective when analyzing primary and secondary outcomes. Amid the present use of PTFE covered stents, data regarding survival, patency rates, and the development of post-treatment HE seems to be improved38, 39, 40, 41. Furthermore, the results of a recent meta-analysis of six published controlled trials comparing clinical outcomes of TIPS with PTFE covered stents versus bare metals stents showed significant improvement of primary patency rates, significant reduction in the risk of developing HE, and a significant decrease in mortality42.

Lastly, it is worth mentioning that TIPS has also been compared to surgical shunts in the management of recurrent variceal bleeding. In a meta-analysis including three prospective randomized trials and one retrospective case-controlled study, 30-day and 1-year survival were found to be the equivalent between the two groups43, though the 2-year survival rate was significantly better in the surgical patients with an odds ratio (OR) of 2.5. Less frequent shunt failure was also significantly reduced in the surgical patients with an OR of 0.3. However, with the use of PTFE covered stents, the ease and efficacy of TIPS has made surgical shunts rare and there is limited expertise in the US to perform such shunts whereas TIPS is widely available.

Refractory Bleeding from Gastric Varices and Portal Hypertensive Gastropathy

Few studies have shown the efficacy of TIPS in refractory bleeding gastric varices44,45,46,47. In one series, 28 patients with gastric fundal varices unresponsive to vasoconstrictor therapy underwent emergent TIPS placement. Bleeding was controlled in most patients, comparable to the success rate for bleeding esophageal varices45. In another small series with 32 patients with refractory bleeding gastric varices, TIPS placement achieved homeostasis in 90% in those with active bleeding, and re-bleeding rates were 14%, 26%, and 31%, respectively at 1 month, 6 months, and 1 year48. In addition, TIPS has also been compared to glue therapy for bleeding gastric varices48,49. In a prospective, randomized control trial comparing TIPS to cyanoacrylate therapy, TIPS was found to be more effective with less re-bleeding rates (11%) versus the cyanoacrylate group (38%)47. Both groups were also found to have similar survival rates and frequencies of complications. It is also important to note that another endovascular procedure, balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration for gastric varices (BRTO) has recently shown promising results for refractory bleeding from gastric varices50.

Portal hypertensive gastropathy (PHG) is common in patients in portal hypertension and its prevalence parallels with severity of liver disease51. The diagnosis of PHG is made endoscopically with gastric mucosa having a “snakeskin” appearance of the fundus and body of the stomach. Though bleeding from PHG is uncommon, TIPS has been evaluated in several small studies52,53. In these studies, there was 75–90% endoscopic improvement in PHG following TIPS, and one series demonstrated a decreased need for transfusions52.

Refractory Ascites

Management of refractory ascites includes large volume paracentesis (LVP) and TIPS. The mechanism of action of how TIPS may improve ascites is through increased natriuresis via reductions in proximal tubular sodium reabsorption and in the RAAS54. There have been a total of six randomized controlled trials comparing LVP to TIPS (Table 255, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60) involving 396 patients, of which 197 underwent TIPS. Findings from these studies have shown that TIPS improved control of ascites (range of 38–84%, mean of 64%) vs LVP (range 0–43%, mean of 24%). However, there were also increased rates of post TIPS HE (range of 23–77%, mean of 53%) with no effect on survival in four of the six studies. From the results of multiple meta-analysis61, 62, 63, 64, 65, insertion of TIPS showed similar improvement of ascites, though survival benefit seemed to be inconclusive as 3 or the 5 meta-analysis did not show improved survival.

Table 2.

TIPS versus Large Volume Paracentesis in Treatment for Refractory Ascites

| Study Findings | References | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Lebrec et al57 | Rossle et al58 | Gines et al59 | Sanyal et al60 | Salnero et al61 | Narahara et al62 | |

| No. of pts | 25 | 66 | 70 | 109 | 66 | 60 |

| No. of TIPS pts | 13 | 29 | 35 | 52 | 33 | 30 |

| No. of LVP pts

|

12 | 31 | 35 | 57 | 33 | 30 |

| Improvement of ascites | ||||||

| TIPS no. (%) | 5 (38) | 16 (84) | 18 (51) | 30 (53) | 26 (79)** | 24 (80) |

| LVP no. (%)

|

0 (0) | 9 (43) | 6 (17) | 9 (16) | 14 (42)** | 8 (27) |

| Survival | ||||||

| TIPS % | 29* | 58* | 26* | 26 | 59* | 64* |

| LVP %

|

56* | 32* | 30* | 30 | 29* | 35* |

| Post-Treatment Encephalopathy | ||||||

| TIPS no. (%) | 3 (23) | 15 (51) | 27 (77) | 22 (39) | 20 (61) | 20 (66) |

| LVP % no. (%) | 0 (0) | 11 (35) | 23 (66) | 13 (23) | 13 (39) | 5 (17) |

Transplant-free survival after two years

Defined as treatment failure, which was defined as when a patient received at least 4 LVP within 1 month for episodes of recurrent tense ascites.

TIPS, tranjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt

LVP, large volume paracentesis

Refractory Hepatic Hydrothorax

Hepatic hydrothrorax occurs in about 6–10% of patients with advanced cirrhosis66. The treatment of hepatic hydrothorax includes medical therapy, repeated thoracentesis, chest tube placement and diaphragmatic defect repair67. Refractory hepatic hydrothorax poses a significant therapeutic challenge and is limited to video-assisted thoracoscopic (VATS) and TIPS for those not who are not transplant candidates.

TIPS has been evaluated for refractory hepatic hydrothorax in numerous small non-controlled trials 70, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73. On the whole, 198 patients underwent TIPS with a response rate (both complete and partial) ranging from 59–82%. Survival, however, could not be reliably determined given that there were no control groups, and that most of the studies were retrospective studies. Nevertheless, 30-day mortality ranged from 5–25%, with 2 studies74, 75 reporting a 1 year survival of 64% and 48% respectively. In summary, given its response rate, and limited therapeutic options, TIPS is an adequate management strategy for refractory hepatic hydrothorax.

Hepatopulmonary Syndrome

Hepatopulmonary syndrome (HPS) is complication of advanced cirrhosis and is due to the development of intrapulmonary vascular dilatation resulting in hypoxia74. There have been number of case reports and small series of studies evaluating TIPS in HPS75, 76. In one series, 7 patients with HPS underwent TIPS placement, of which only 1 patient had transient improvement in arterial oxygenation78. Thus, given the limited data available, TIPS insertion is currently not recommended for the HPS3.

Hepatorenal Syndrome

There are two types of hepatorenal syndrome (HRS), type 1 and type 2, and its development confers a poor prognosis. Type 1 is a rapid, progressive decline in renal function (less than 2 weeks) and type 2 is characterized as gradual decline in renal function77. There have been 4 small studies (n of 61) evaluating the role of TIPS in HRS78,79, 80, 81. In these studies, TIPS insertion was found to improve renal function through enhanced glomerular filtration rates and renal plasma flow as well as via reductions in serum creatinine and plasma aldosterone levels. Because none of these studies were controlled, survival benefit cannot be fully elucidated. In the largest series82 1 and 2 year survival rates were 20% for type 1, and 70% and 45% for type 2, respectively. In addition, TIPS may have a role in maintenance therapy in patients who initially respond to vasoconstrictor therapy84 and as a bridge to liver transplantation83.

Budd-Chiari Syndrome

The Budd-Chiari Syndrome (BCS) is caused by hepatic venous outflow obstruction or thrombosis hepatic veins or hepatic portion of the inferior vena cava (IVC) leading to a clinical constellation of liver injury, abdominal pain, and ascites82. There have been only a small number of studies evaluating the utility of TIPS for the management of BCS83, 84, 85, 86. In one of the larger series89, 124 patients (of which included patients with severe BCS who did not respond to medical treatment and recanalization) underwent TIPS placement. Overall 5- year survival was 84% and transplant-free survival at 1 and 5 years after TIPS was 88% and 78% respectively.

From a technical aspect, creation of TIPS may be difficult if the hepatic veins are occluded. This can be overcome with a transcaval approach using ultrasound guidance through the caudate lobe with subsequent implantation of a covered stent89. Furthermore, a larger diameter of the shunt is recommended to allow for both decompression of sinusoidal and splanchnic beds89. A transmesenteric approach may also be performed in this situation, but this approach is limited to few centers87.

Hepatic Veno-occlusive disease

Veno-occlusive disease (also known as sinusoidal obstruction syndrome) is usually seen after bone marrow transplantation88. The disease is similar to BCS, however, hepatic venous outflow obstruction occurs at the level of the hepatic venules and sinusoids. In a limited number of patients89, 90, 91, 92, TIPS insertion had shown improvement in liver disease, although it did not improve survival. Given the limited data, the value of TIPS in veno-occlusive disease is unclear, and should be approached on a case by case basis.

Patient Selection and Pre-TIPS Evaluation

Patients who are being considered for a TIPS procedure should be under the care of a gastroenterologist or hepatologist with consultation from interventional radiology. Absolute and relative contraindications3 are listed in Box 2. Absolute contraindications include heart failure, severe tricuspid regurgitation, severe pulmonary hypertension (mean pulmonary wedge pressure >45 mm Hg). Relative contraindications include anatomic issues that can complicate the creation of the shunt or reduce technical success (i.e. obstruction of hepatic veins, portal vein thrombosis, hepatic masses, hepatic cysts), severe coagulopathy, and HE. Even though TIPS can be created in the aforementioned situations, the risk, benefit, and difficulty with creating the shunt needs to be balanced with patient care and the clinical scenario. Examples of this include palliative treatment for HCC patients with refractory variceal bleeding, recanalization of occluded portal veins in patients with recurrent variceal bleeding, and treatment of patients with BCS and progressive liver failure. In addition, patients with a history of HE are at an increased risk for exacerbation of HE after shunt creation93 and they should be aware of this risk-benefit scenario

Box 2. Contraindications for TIPS.

| RELATIVE | Absolute |

|---|---|

| Hepatocellular Carcinoma, especially centrally located | Primary prevention of variceal bleeding |

| Obstruction of all hepatic veins | Congestive heart failure |

| Portal vein thrombosis | Severe tricuspid regurgitation |

| Moderate pulmonary hypertension | Severe pulmonary hypertension |

| Severe coagulopathy (international normalized ration >5) | Multiple hepatic cysts |

| Thrombocytopenia of <20,000 cells/cm3 | Uncontrolled systemic infection or sepsis |

| Hepatic encephalopathy | Unrelieved biliary obstruction |

There have been numerous models created in predicting post-TIPS survival94, 95, 96, 97, 98. Among these, the modified Model for End-Stage Liver Disease score (MELD)99 has proved to be superior to CPT score and Emory score101. A MELD score above 18 predicts a significantly higher mortality 3 months after TIPS as compared to a score of less than 1899, 100. In addition, mortality is also dependent on the original TIPS indication.

Like with any procedure, the TIPS procedure carries its risks and benefits, and a clear understanding of these risks and benefits must be understood and agreed upon by the patient. A detailed history and physical examination is required. In addition, pre-TIPS laboratory studies should be obtained 24 hours prior the procedure. These include serum electrolytes, complete blood count, coagulation studies, and liver and kidney function panel.

Cross-sectional imaging (liver ultrasound with Doppler, computer tomography, or magnetic resonance imaging) should be reviewed, and if not current (>1 month), a repeat study should be obtained to evaluate vascular patency and to look for hepatic masses or other pathology that may complicate the procedure. In patients who have suspected or known cardiac or pulmonary disease, an echocardiogram should be obtained to exclude diastolic/systolic dysfunction and pulmonary arterial hypertension because TIPS is known to increase central venous pressure, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure, and exacerbate known cardiac dysfunction101. In addition, a paracenetesis should be performed for refractory ascites prior the procedure in order to reduce the risk of peri-procedural bleeding. Furthermore, a thoracentesis may benefit patients with hepatic hydrothorax as it may improve respiratory function and assist with sedation.

Conventional Technique

In the US the TIPS procedure is performed by interventional radiologists. The procedure is either performed under conscious sedation or under general anesthesia with endotracheal intubation5. The later is preferred by many for patient control and comfort due to the potentially prolonged nature of the procedure.

Hepatic Venous Access

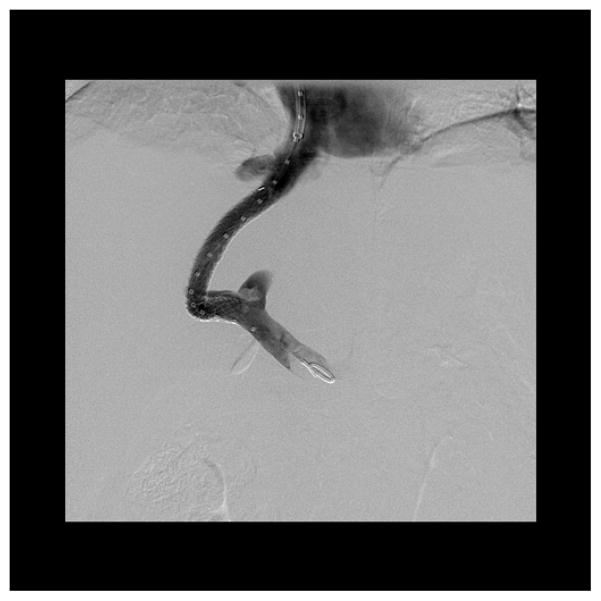

A right internal jugular (IJ) approach is preferred as it allows a direct path to the IVC. Secondary options include left IJ vein102 and femoral vein103 approaches, but these are reserved for unusual anatomy or in cases of central venous occlusive disease. After the neck is cleaned and draped in a sterile fashion, IJ venous access is obtained via sonographic guidance. A catheter is then advanced beyond the right atrium into the HV under fluoroscopic guidance. The right HV is chosen whenever possible as it allows for an anterior inferior transhepatic puncture of the right portal vein, thus providing the safest approach for the TIPS. A wedged hepatic venogram is then obtained using carbon dioxide to demonstrate the portal venous anatomy (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Wedged hepatic venogram using an occlusion balloon from the right hepatic vein demonstrating normal portal venous anatomy.

Portal Venous Access and TIPS Insertion

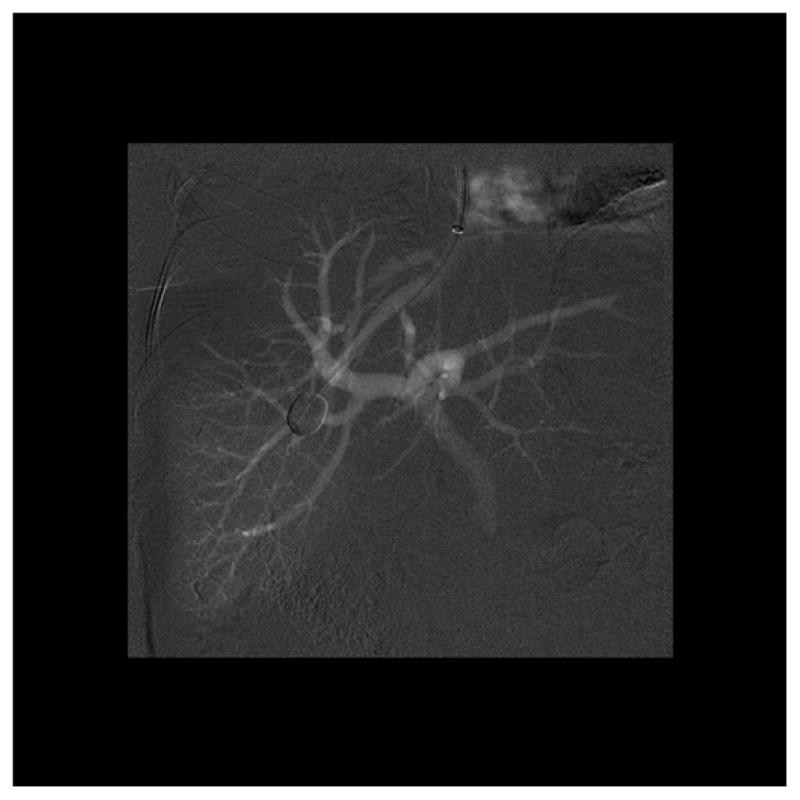

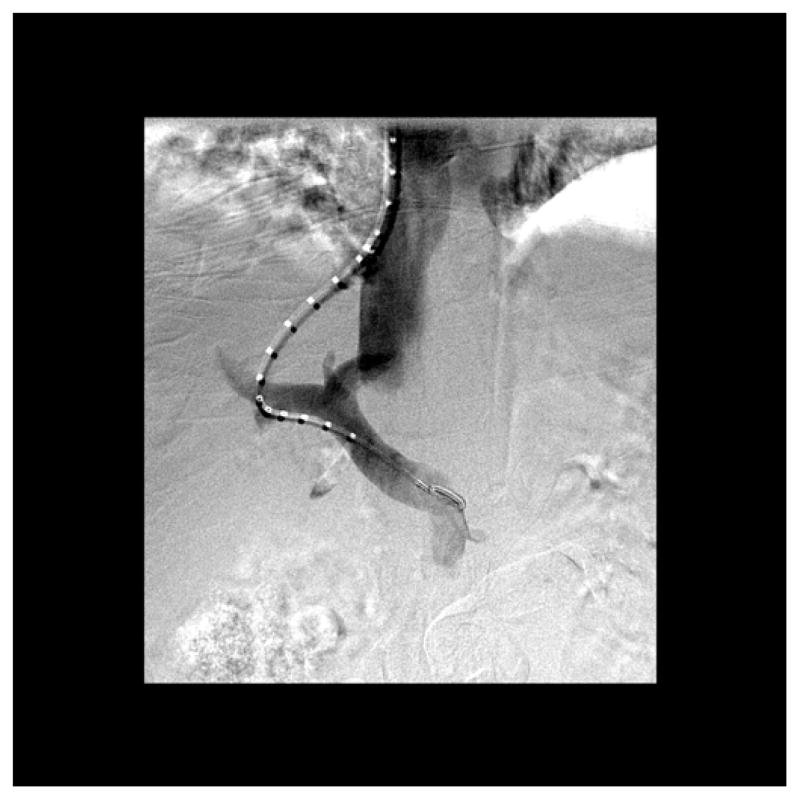

There are several commercial sets available for portal puncture: Haskal (Cook Medical) and Ring (Cook Medical) transjugular intrahepatic access sets which both includes a 16-gauge modified Colapinto puncture needle; Rosch-Uchida transjugular liver access set (Cook Medical) which contains a 14-gauge needle; and Angiodynamic transjugular access set (Angiodynamics Medical) containing 14 and 21-gauge needles. After the CO2 portogram has been performed and a target identified, the needle (which is constrained in a hard inner sheath and softer 10 French outer sheath) is directed anteriorly and inferiorly from the right HV into the right PV (Figure 3). Once access is achieved, the needle is removed and a wire and catheter are advanced into the splenic or mesenteric vein. Portal venography (Figure 4) and pressure measurements are performed.

Figure 3.

Injection of contrast confirming placement of needle in a branch of the right portal vein.

Figure 4.

Simultaneous injection of contrast through a marker pigtail catheter in the portal vein and sheath in the right hepatic vein demonstrating appropriate anatomy.

An angioplasty balloon is then used to dilate the tract (Figure 5), allowing for passage of the 10 French sheath into the PV. The PTFE-covered stent (Viatorr, W. L. Gore), which is the standard TIPS stent, is then deployed and post dilated to 8 mm. This is a unique stent because the caudal 2 cm, which resides in the PV, is uncovered, and the variable cranial length of the stent, which traverses the liver and HV, is covered by PTFE. After stent deployment and dilation, trans-TIPS portal venography (Figure 6) and pressure measurements are repeated. If the pressure remains higher than desired, the stent can be further dilated to 10 or 12 mm. A PPG less than 12 mmHg3 should be achieved in patients with a history of bleeding esophageal varices and refractory ascites. However the optimal PPG for refractory ascites is still under much debate with some authors suggesting a PPG of less than 8mmHg59. In patients with pre-existing HE, a higher gradient may be appropriate to reduce post-TIPS HE104, more data is needed to elucidate this.

Figure 5.

Angioplasty balloon dilating the transhepatic tract to 8 mm prior to stent placement.

Figure 6.

Completion venogram through the pigtail catheter demonstrating appropriate flow from the portal vein through the TIPS shunt into the right hepatic vein and right atrium.

Selective Embolization of Portosytemic Collaterals

At the discretion of the interventionalist, selective embolization of varices or other portosystemic collaterals can be performed after TIPS placement. This may benefit patients with a history of bleeding esophageal varices as embolization at the time of TIPS placement has been found to decrease the rate of recurrent esophageal bleeding (84% and 81% at 2 and 4 years respectively) vs TIPS alone (61% and 53% at 2 and 4 years respectively)105. Furthermore, selective embolization can also be performed in cases where the gradient is not reduced to less than 12 mmHg. There are a wide variety of embolic devices which can be used including coils and Amplatzer Vascular Plugs (St. Jude Medical).

Immediate Post-Procedural Management

After TIPS placement patients should be observed for a minimum of 12 hours in a hospital unit. Vital signs should be closely monitored for evidence of intraperitoneal hemorrhage. Post-TIPS laboratory values should be obtained including a complete blood count (to monitor for hemorrhage and infection), coagulation panel, and kidney and hepatic function tests. A liver sonogram with Doppler can be obtained a day after the shunt placement to evaluate for shunt patency.

Advanced and Alternative TIPS Techniques

Numerous options exist when difficult anatomy prohibits the right hepatic to right PV approach. These include a left hepatic to left portal approach or an IVC to right portal approach through the caudate lobe with or without the aid of transabdominal or intravascular ultrasound. The ‘gunsight technique’106 can be employed when success has not been achieved with traditional transvascular methods. This involves placement of a loop snare in the IVC from the IJ access and placement of a loop snare in the PV from a percutaneous approach. A needle is then advanced from a second percutaneous approach using lateral fluoroscopy through both loop snares into the IVC. A wire is passed through the needle into the IVC and snared from above, thus establishing systemic to portal access for placement of the shunt.

Occasionally, patients with PV thrombosis will present and require recanalization of the portal system. This can be achieved through a variety of techniques using a percutaneous or transhepatic approach in order to relieve the portal obstruction and facilitate flow through the shunt (Figure 7).

Figure 7. TIPS Procedure with ‘Gunsight Technique’.

A: Intravascular US has been placed in the IVC and percutaneous access into the portal system has been obtained and confirmed with an injection of contrast through the needle.

B: After puncturing through loopsnares in the right portal vein and IVC from a second percutaneous access, the wire was pulled through the IVC sheath and the tract between the two sheaths is being angioplastied with a small diameter balloon.

C: The wire was pulled into the portal vein and advanced into the splenic vein from above and the tract is now being dilated to 8mm.

D: Completion venogram through the pigtail catheter demonstrating appropriate flow from the portal vein through the TIPS shunt into the right hepatic vein and right atrium.

Complications

The most common complications following the TIPS procedure are listed in Table 32. These complications can be divided into 3 major categories: technical related, portosystemic related and other unique complications.

Table 3.

Complications from TIPS

| Technical complications |

| Related to access |

| Capsule puncture |

| Intraperitoneal bleed |

| Hepatic infarction |

| Fistula |

| Hemobilia |

| Related to the stent |

| Thrombosis |

| Occlusion |

| Stent migration |

| Sepsis |

| Related to portosystemic shunting |

| Hepatic encephalopathy |

| Hemodynamic consequences |

| Sepsis |

| Unique complications |

| Intravascular hemolysis |

| Endotipsitis |

From Bhogal HK, Sanyal AJ. Using transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts for complications of cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9(11):936–46, with permission.

Technical Access Related

Puncture of the liver capsule is common, occurring up to 30% of patients109, though serious intraperitoneal bleeding is rare. Liver capsule puncture is likely in patients with a small liver, and when multiple needle punctures are required. Biliary puncture and fistula formation is also a rare complication, occurring with an incidence of less than 5%107. Fistula formation between the biliary and vascular systems could result in hemobilia, cholangitis, sepsis, and stent infection1, 108. If fistula formation occurs between a stent and the biliary system, early stent occlusion may ensue due to marked psuedointimal hyperplasia109. Fistulous communication may be decreased by employing controlled needle passage and number of needle punctures. Biliary diversion via internal or external drainage catheter may be used to address biliary-vascular fistulas, embolization can be performed in cases of hemobilia, and biliary-stent fistulas can be treated with placement of a PTFE covered stent to reline the hepatic parenchymal tract109.

Hepatic infarction is a rare complication which can result from a reduction in sinusoidal flow. It can also occur secondary to stent compression of the hepatic artery. A low PPG after TIPS placement can increase the incidence of hepatic infarction. This problem can be treaded with placement of stents within the primary stent to reduce the shunt caliber.

Technical Stent Related

With the use of PTFE covered stents, thrombosis, occlusion, and stent migration are infrequently seen2, 3. Prior to the use of PTFE covered stents, the most common site for shunt stenosis was at the hepatic venous end. Mid-stent stenosis is thought to be secondary to pseudointimal hyperplasia within bare metal stents110, with rates of stenosis ranging from 18–78%3. In a randomized control trial111 comparing covered and bare metal stents, rates of primary patency in the covered and bare metal stent groups were 86% and 47% respectively at 1 year. At 2 years, patency rates were 80% and 19% for covered and bare metal stents respectively. In another large non-randomized series112, primary patency rates were similar with 87% and 81% at 6 and 12 months respectively.

Portosystemic Shunting Related

HE is the most frequent medical complication that usually occurs 2–3 weeks after TIPS insertion113. The pathophysiology of post-TIPS HE is complex, though mainly due to diverted portal flow away from the liver due to TIPS and into the arterial system95,114 and decreased liver metabolic capacity. Frequency of new or worsening HE ranges from 10–44%3, and factors associated with post-TIPS HE development include prior history of HE, increasing age, shunt caliber, high creatinine levels, low serum sodium concentration and liver dysfunction95, 115. Previously, studies with bare metal stents found an increased risk for the development of HE after TIPS insertion for ascites57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62. Consequently, studies with covered stents found to have lower rates of HE after TIPS placement113, 116. A meta-analysis of further confirms this statement33. However, it should be mentioned that most of these studies were not designed to test post-TIPS HE. In addition, the methodology used to access for HE was highly variable and subjective based.

Prevention of post-TIPS HE include possibly having a higher PPG106 (especially in patients with a high risk of HE), and treating precipitating factors prior to TIPS placement. Post-TIPS HE can be treated with standard therapy, and in refractory cases, the shunt can be reduced or occluded95,116, 106,117.

Unique Complications

Intravascular hemolysis and endotipsitis (infection of TIPS stent) are rare complications of TIPS109, 118, 119 and infrequently occur with covered stents. If present, intravascular hemoloysis is usually self-limiting, resolving in 3–4 weeks. Endotipsitis presents with fever, abdominal pain, and laboratory evaluation reveals positive blood cultures and an elevated white blood cell count. Treatment is with prolonged antibiotics.

Post-TIPS Follow up and Maintenance

Recurrence of portal hypertension symptoms could indicate shunt dysfunction. Prompt sonogram with Doppler of the liver should be obtained to evaluate shunt velocity. Velocities of 50 cm/s or less or 250cm/s are associated with shunt dysfunction, with greater than 90% sensitivity and specificity120. If a patient is asymptomatic, sonogram with Doppler of the liver is usually performed within 4 weeks of placement and every 6 months to a year. The gold standard to evaluate shunt patency is portal venography. However this is reserved to evaluate shunt occlusion seen on sonogram as it is invasive and carries its own complications. If a bare metal stent was used, revision with a covered stent can be performed120.

Future Considerations

The use of TIPS in the management of end stage liver disease has been refined and it is now an integral part of the treatment armamentarium for this condition. A key challenge that remains to be resolved is how to prevent further hepatic decompensation in those who already have some hyperbilirubinemia prior to TIPS. The impact of TIPS on the systemic microcirculatory dysfunction associated with cirrhosis also needs to be better understood. Although it is much less common than before, acute on chronic liver failure still occurs with TIPS and better methods to prevent this are needed. As expected, porta-systemic shunting increases the risk of infection and the role of selective gut decontamination or ways to improve intestinal barrier functions in preventing ACLF after TIPS are now needed. There have also been reports of an increased risk of HCC after TIPS. This needs to be definitively confirmed or refuted.

Conclusions

TIPS has become a valuable option in management for the complications of portal hypertension. The best available evidence for the use of TIPS includes refractory or recurrent esophageal variceal bleeding and refractory ascites. In addition, TIPS insertion could improve outcomes for patients who present with an acute variceal bleed, hepatic hydrothorax, and hepatorenal syndrome. With the use of covered stents, long term patency has dramatically improved, further advocating early use. The insertion of TIPS unfortunately comes with complications, with HE being one of the most common. A possible solution to this includes thorough selection of patients and careful attention to the final portosystemic gradient. Lastly, with advanced and alternative techniques, TIPS could play a larger role in the future treatment in patients with complications of portal hypertension.

Key Points.

The largest body of evidence supports the use of TIPS in recurrent or refractory esophageal variceal bleeding followed by refractory ascites. Its use may also be beneficial for other conditions including hepatic hydrothorax, Budd-Chiari syndrome, Hepatorenal Syndrome, and Hepatopulmonary Syndrome.

Contraindications for TIPS placement include systolic and diastolic cardiac disease, severe pulmonary hypertension, and primary prevention of variceal bleed.

Numerous innovative supporting techniques have evolved over recent years to address problematic anatomy, improve the safety profile of the procedure, and to improve outcomes.

Outline.

Indications

Patient Selection

Conventional Technique

Alternative and Advanced Techniques

Complications

Post-Tips Management

Future Considerations and Conclusion

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: Dr. Sanyal: see attached document (page 35), Dr. Sydnor: none, Dr. Patidar: none

ARUN J SANYAL M.D.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURE TABLE

JANUARY 2014 (based on incomes over last 24 months)

A: No interest

B: < $ 5000

C: $ 5001–10,000

D: $ 10,001–$50,000

E: $ 50,001–100,000

F: > $ 100,000

| Company | Stock | Employment | Speaker | Consulting advisor | Research grants | Travel grants | Intellectual property | Royalties |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abbott | A | A | A | B | A | A | A | A |

| Exhalenz | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | A |

| Conatus | A | A | A | A | C**** | A | A | A |

| Genentech | A | A | A | B^ | A | A | A | A |

| GenFit | A | A | A | A* | A | A | A | A |

| Gilead | A | A | A | B | F | A | A | A |

| Echosens-Sandhill | A | A | A | A* | A^^ | A | A | A |

| Ikaria | A | A | A | B | E | A | A | A |

| Immuron | A | A | A | A** | A | A | A | A |

| Intercept | A | A | A | A* | A | A | A | A |

| Merck | A | A | A | B | A | A | A | A |

| Norgine | A | A | A | B | A | A | A | A |

| Roche | A | A | A | B | A | A | A | A |

| Salix | A | A | A | C | E | A | A | A |

| Uptodate | A | A | A | A | A | A | A | C |

| Takeda | A | A | A | B | D | A | A | A |

| Astellas | A | A | A | A | D | A | A | A |

| Novartis | A | A | A | A*** | E | A | A | A |

| Nimbus | A | A | A | B | A | A | A | A |

| Galectin | A | A | A | A*** | E | A | A | A |

| Nitto Denko | A | A | A | B | A | A | A | A |

| Sequana | A | A | A | A* | A | A | A | A |

| Bristol Myers | A | A | A | B | A | A | A | A |

DISCLOSURES

Funding Sources: Dr. Sanyal: T32 training grant, Dr. Sydnor: none, Dr. Patidar: none

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Rosch J, Hanafee W, Snow H, Barenfus M, Gray R. Transjugular intrahepatic portacaval shunt. an experimental work. Am J Surg. 1971;121(5):588–592. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(71)90147-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bhogal HK, Sanyal AJ. Using transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts for complications of cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9(11):936–46. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2011.06.013. quiz e123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tripathi D, Redhead D. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent-shunt: Technical factors and new developments. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;18(11):1127–1133. doi: 10.1097/01.meg.0000236871.78280.a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boyer TD, Haskal ZJ American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. The role of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) in the management of portal hypertension: Update 2009. Hepatology. 2010;51(1):306. doi: 10.1002/hep.23383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rossle M, Haag K, Ochs A, et al. The transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent-shunt procedure for variceal bleeding. N Engl J Med. 1994;330(3):165–171. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199401203300303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boyer TD. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt: Current status. Gastroenterology. 2003;124(6):1700–1710. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)00377-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luketic VA, Sanyal AJ. Esophageal varices. II. TIPS (transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt) and surgical therapy. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2000;29(2):387–421. vi. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8553(05)70120-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cello JP, Ring EJ, Olcott EW, et al. Endoscopic sclerotherapy compared with percutaneous transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt after initial sclerotherapy in patients with acute variceal hemorrhage. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126(11):858–865. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-126-11-199706010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sanyal AJ, Freedman AM, Luketic VA, et al. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts compared with endoscopic sclerotherapy for the prevention of recurrent variceal hemorrhage. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126(11):849–857. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-126-11-199706010-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cabrera J, Maynar M, Granados R, et al. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt versus sclerotherapy in the elective treatment of variceal hemorrhage. Gastroenterology. 1996;110(3):832–839. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v110.pm8608893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barton RE, Rosch J, Saxon RR, Lakin PC, Petersen BD, Keller FS. TIPS: short- and long-term results: a survey of 1750 patients. Semin Interv Radiol. 1995;12:364–367. doi: 10.1016/s1051-0443(95)71180-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.North Italian Endoscopic Club for the Study and Treatment of Esophageal Varices. Prediction of the first variceal hemorrhage in patients with cirrhosis of the liver and esophageal varices. A prospective multicenter study. N Engl J Med. 1988;319(15):983–989. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198810133191505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garcia-Tsao G, Sanyal AJ, Grace ND, Carey W Practice Guidelines Committee of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Prevention and management of gastroesophageal varices and variceal hemorrhage in cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2007;46(3):922–938. doi: 10.1002/hep.21907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kovalak M, Lake J, Mattek N, Eisen G, Lieberman D, Zaman A. Endoscopic screening for varices in cirrhotic patients: Data from a national endoscopic database. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65(1):82–88. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.D’Amico G, Pagliaro L, Bosch J. Pharmacological treatment of portal hypertension: An evidence-based approach. Semin Liver Dis. 1999;19(4):475–505. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1007133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Monescillo A, Martinez-Lagares F, Ruiz-del-Arbol L, et al. Influence of portal hypertension and its early decompression by TIPS placement on the outcome of variceal bleeding. Hepatology. 2004;40(4):793–801. doi: 10.1002/hep.20386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garcia-Pagan JC, Caca K, Bureau C, et al. Early use of TIPS in patients with cirrhosis and variceal bleeding. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(25):2370–2379. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0910102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bosch J, Garcia-Pagan JC. Prevention of variceal rebleeding. Lancet. 2003;361(9361):952–954. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12778-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.D’Amico G, De Franchis R Cooperative Study Group. Upper digestive bleeding in cirrhosis. post-therapeutic outcome and prognostic indicators. Hepatology. 2003;38(3):599–612. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Franchis R, Primignani M. Why do varices bleed? Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1992;21(1):85–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Burroughs AK, Mezzanotte G, Phillips A, McCormick PA, McIntyre N. Cirrhotics with variceal hemorrhage: The importance of the time interval between admission and the start of analysis for survival and rebleeding rates. Hepatology. 1989;9(6):801–807. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840090602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Graham DY, Smith JL. The course of patients after variceal hemorrhage. Gastroenterology. 1981;80(4):800–809. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lebrec D, De Fleury P, Rueff B, Nahum H, Benhamou JP. Portal hypertension, size of esophageal varices, and risk of gastrointestinal bleeding in alcoholic cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 1980;79(6):1139–1144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moitinho E, Escorsell A, Bandi JC, et al. Prognostic value of early measurements of portal pressure in acute variceal bleeding. Gastroenterology. 1999;117(3):626–631. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70455-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sauer P, Theilmann L, Stremmel W, Benz C, Richter GM, Stiehl A. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent shunt versus sclerotherapy plus propranolol for variceal rebleeding. Gastroenterology. 1997;113(5):1623–1631. doi: 10.1053/gast.1997.v113.pm9352865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jalan R, Forrest EH, Stanley AJ, et al. A randomized trial comparing transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent-shunt with variceal band ligation in the prevention of rebleeding from esophageal varices. Hepatology. 1997;26(5):1115–1122. doi: 10.1002/hep.510260505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Merli M, Salerno F, Riggio O, et al. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt versus endoscopic sclerotherapy for the prevention of variceal bleeding in cirrhosis: A randomized multicenter trial. gruppo italiano studio TIPS (G.I.S.T.) Hepatology. 1998;27(1):48–53. doi: 10.1002/hep.510270109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sauer P, Hansmann J, Richter GM, Stremmel W, Stiehl A. Endoscopic variceal ligation plus propranolol vs. transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent shunt: A long-term randomized trial. Endoscopy. 2002;34(9):690–697. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-33565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garcia-Villarreal L, Martinez-Lagares F, Sierra A, et al. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt versus endoscopic sclerotherapy for the prevention of variceal rebleeding after recent variceal hemorrhage. Hepatology. 1999;29(1):27–32. doi: 10.1002/hep.510290125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pomier-Layrargues G, Villeneuve JP, Deschenes M, et al. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) versus endoscopic variceal ligation in the prevention of variceal rebleeding in patients with cirrhosis: A randomised trial. Gut. 2001;48(3):390–396. doi: 10.1136/gut.48.3.390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Narahara Y, Kanazawa H, Kawamata H, et al. A randomized clinical trial comparing transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt with endoscopic sclerotherapy in the long-term management of patients with cirrhosis after recent variceal hemorrhage. Hepatol Res. 2001;21(3):189–198. doi: 10.1016/s1386-6346(01)00104-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gulberg V, Schepke M, Geigenberger G, et al. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunting is not superior to endoscopic variceal band ligation for prevention of variceal rebleeding in cirrhotic patients: A randomized, controlled trial. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2002;37(3):338–343. doi: 10.1080/003655202317284255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Luca A, D’Amico G, La Galla R, Midiri M, Morabito A, Pagliaro L. TIPS for prevention of recurrent bleeding in patients with cirrhosis: Meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Radiology. 1999;212(2):411–421. doi: 10.1148/radiology.212.2.r99au46411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34*.Papatheodoridis GV, Goulis J, Leandro G, Patch D, Burroughs AK. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt compared with endoscopic treatment for prevention of variceal rebleeding: A meta-analysis. Hepatology. 1999;30(3):612–622. doi: 10.1002/hep.510300316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35*.Burroughs AK, Vangeli M. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt versus endoscopic therapy: Randomized trials for secondary prophylaxis of variceal bleeding: An updated meta-analysis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2002;37(3):249–252. doi: 10.1080/003655202317284138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36*.Zheng M, Chen Y, Bai J, et al. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt versus endoscopic therapy in the secondary prophylaxis of variceal rebleeding in cirrhotic patients: Meta-analysis update. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42(5):507–516. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31815576e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Escorsell A, Banares R, Garcia-Pagan JC, et al. TIPS versus drug therapy in preventing variceal rebleeding in advanced cirrhosis: A randomized controlled trial. Hepatology. 2002;35(2):385–392. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.30418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Angermayr B, Cejna M, Koenig F, et al. Survival in patients undergoing transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt: EPTFE-covered stentgrafts versus bare stents. Hepatology. 2003;38(4):1043–1050. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barrio J, Ripoll C, Banares R, et al. Comparison of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt dysfunction in PTFE-covered stent-grafts versus bare stents. Eur J Radiol. 2005;55(1):120–124. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2004.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tripathi D, Redhead D. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent-shunt: Technical factors and new developments. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;18(11):1127–1133. doi: 10.1097/01.meg.0000236871.78280.a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bureau C, Pagan JC, Layrargues GP, et al. Patency of stents covered with polytetrafluoroethylene in patients treated by transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts: Long-term results of a randomized multicentre study. Liver Int. 2007;27(6):742–747. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2007.01522.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang Z, Han G, Wu Q, et al. Patency and clinical outcomes of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt with polytetrafluoroethylene-covered stents versus bare stents: A meta-analysis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;25(11):1718–1725. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2010.06400.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Clark W, Hernandez J, McKeon B, et al. Surgical shunting versus transjugular intrahepatic portasystemic shunting for bleeding varices resulting from portal hypertension and cirrhosis: A meta-analysis. Am Surg. 2010;76(8):857–864. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chau TN, Patch D, Chan YW, Nagral A, Dick R, Burroughs AK. “Salvage” transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts: Gastric fundal compared with esophageal variceal bleeding. Gastroenterology. 1998;114(5):981–987. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)00640-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rees CJ, Nylander DL, Thompson NP, Rose JD, Record CO, Hudson M. Do gastric and oesophageal varices bleed at different portal pressures and is TIPS an effective treatment? Liver. 2000;20(3):253–256. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0676.2000.020003253.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tripathi D, Therapondos G, Jackson E, Redhead DN, Hayes PC. The role of the transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent shunt (TIPSS) in the management of bleeding gastric varices: Clinical and haemodynamic correlations. Gut. 2002;51(2):270–274. doi: 10.1136/gut.51.2.270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Barange K, Peron JM, Imani K, et al. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt in the treatment of refractory bleeding from ruptured gastric varices. Hepatology. 1999;30(5):1139–1143. doi: 10.1002/hep.510300523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lo GH, Liang HL, Chen WC, et al. A prospective, randomized controlled trial of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt versus cyanoacrylate injection in the prevention of gastric variceal rebleeding. Endoscopy. 2007;39(8):679–685. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-966591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Procaccini NJ, Al-Osaimi AM, Northup P, Argo C, Caldwell SH. Endoscopic cyanoacrylate versus transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt for gastric variceal bleeding: A single-center U.S. analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70(5):881–887. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.03.1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sabri SS, Swee W, Turba UC, et al. Bleeding gastric varices obliteration with balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration using sodium tetradecyl sulfate foam. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2011;22(3):309–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2010.11.022. quiz 316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Primignani M, Carpinelli L, Preatoni P, et al. Natural history of portal hypertensive gastropathy in patients with liver cirrhosis. the new italian endoscopic club for the study and treatment of esophageal varices (NIEC) Gastroenterology. 2000;119(1):181–187. doi: 10.1053/gast.2000.8555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kamath PS, Lacerda M, Ahlquist DA, McKusick MA, Andrews JC, Nagorney DA. Gastric mucosal responses to intrahepatic portosystemic shunting in patients with cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2000;118(5):905–911. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(00)70176-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Urata J, Yamashita Y, Tsuchigame T, et al. The effects of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt on portal hypertensive gastropathy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1998;13(10):1061–1067. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.1998.tb00571.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wong F, Sniderman K, Liu P, Blendis L. The mechanism of the initial natriuresis after transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt. Gastroenterology. 1997;112(3):899–907. doi: 10.1053/gast.1997.v112.pm9041252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lebrec D, Giuily N, Hadengue A, et al. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts: Comparison with paracentesis in patients with cirrhosis and refractory ascites: A randomized trial. french group of clinicians and a group of biologists. J Hepatol. 1996;25(2):135–144. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(96)80065-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rossle M, Ochs A, Gulberg V, et al. A comparison of paracentesis and transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunting in patients with ascites. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(23):1701–1707. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200006083422303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gines P, Uriz J, Calahorra B, et al. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunting versus paracentesis plus albumin for refractory ascites in cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2002;123(6):1839–1847. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.37073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sanyal AJ, Genning C, Reddy KR, et al. The north american study for the treatment of refractory ascites. Gastroenterology. 2003;124(3):634–641. doi: 10.1053/gast.2003.50088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Salerno F, Merli M, Riggio O, et al. Randomized controlled study of TIPS versus paracentesis plus albumin in cirrhosis with severe ascites. Hepatology. 2004;40(3):629–635. doi: 10.1002/hep.20364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Narahara Y, Kanazawa H, Fukuda T, et al. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt versus paracentesis plus albumin in patients with refractory ascites who have good hepatic and renal function: A prospective randomized trial. J Gastroenterol. 2011;46(1):78–85. doi: 10.1007/s00535-010-0282-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61*.D’Amico G, Luca A, Morabito A, Miraglia R, D’Amico M. Uncovered transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt for refractory ascites: A meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2005;129(4):1282–1293. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62*.Albillos A, Banares R, Gonzalez M, Catalina MV, Molinero LM. A meta-analysis of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt versus paracentesis for refractory ascites. J Hepatol. 2005;43(6):990–996. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Saab S, Nieto JM, Ly D, Runyon BA. TIPS versus paracentesis for cirrhotic patients with refractory ascites. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;(3):CD004889. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64*.Deltenre P, Mathurin P, Dharancy S, et al. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt in refractory ascites: A meta-analysis. Liver Int. 2005;25(2):349–356. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2005.01095.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65*.Salerno F, Camma C, Enea M, Rossle M, Wong F. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt for refractory ascites: A meta-analysis of individual patient data. Gastroenterology. 2007;133(3):825–834. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Alberts WM, Salem AJ, Solomon DA, Boyce G. Hepatic hydrothorax. cause and management. Arch Intern Med. 1991;151(12):2383–2388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kiafar C, Gilani N. Hepatic hydrothorax: Current concepts of pathophysiology and treatment options. Ann Hepatol. 2008;7(4):313–320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gordon FD, Anastopoulos HT, Crenshaw W, et al. The successful treatment of symptomatic, refractory hepatic hydrothorax with transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt. Hepatology. 1997;25(6):1366–1369. doi: 10.1002/hep.510250611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jeffries MA, Kazanjian S, Wilson M, Punch J, Fontana RJ. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts and liver transplantation in patients with refractory hepatic hydrothorax. Liver Transpl Surg. 1998;4(5):416–423. doi: 10.1002/lt.500040506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Siegerstetter V, Deibert P, Ochs A, Olschewski M, Blum HE, Rossle M. Treatment of refractory hepatic hydrothorax with transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt: Long-term results in 40 patients. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;13(5):529–534. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200105000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Spencer EB, Cohen DT, Darcy MD. Safety and efficacy of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt creation for the treatment of hepatic hydrothorax. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2002;13(4):385–390. doi: 10.1016/s1051-0443(07)61741-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wilputte JY, Goffette P, Zech F, Godoy-Gepert A, Geubel A. The outcome after transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) for hepatic hydrothorax is closely related to liver dysfunction: A long-term study in 28 patients. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2007;70(1):6–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dhanasekaran R, West JK, Gonzales PC, et al. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt for symptomatic refractory hepatic hydrothorax in patients with cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(3):635–641. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Machicao VI, Balakrishnan M, Fallon MB. Pulmonary complications in chronic liver disease. Hepatology. 2013 doi: 10.1002/hep.26745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Martinez-Palli G, Drake BB, Garcia-Pagan JC, et al. Effect of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt on pulmonary gas exchange in patients with portal hypertension and hepatopulmonary syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11(43):6858–6862. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i43.6858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Paramesh AS, Husain SZ, Shneider B, et al. Improvement of hepatopulmonary syndrome after transjugular intrahepatic portasystemic shunting: Case report and review of literature. Pediatr Transplant. 2003;7(2):157–162. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3046.2003.00033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Salerno F, Gerbes A, Gines P, Wong F, Arroyo V. Diagnosis, prevention and treatment of hepatorenal syndrome in cirrhosis. Gut. 2007;56(9):1310–1318. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.107789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Guevara M, Gines P, Bandi JC, et al. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt in hepatorenal syndrome: Effects on renal function and vasoactive systems. Hepatology. 1998;28(2):416–422. doi: 10.1002/hep.510280219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Brensing KA, Textor J, Perz J, et al. Long term outcome after transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent-shunt in non-transplant cirrhotics with hepatorenal syndrome: A phase II study. Gut. 2000;47(2):288–295. doi: 10.1136/gut.47.2.288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Testino G, Ferro C, Sumberaz A, et al. Type-2 hepatorenal syndrome and refractory ascites: Role of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent-shunt in eighteen patients with advanced cirrhosis awaiting orthotopic liver transplantation. Hepatogastroenterology. 2003;50(54):1753–1755. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wong F, Pantea L, Sniderman K. Midodrine, octreotide, albumin, and TIPS in selected patients with cirrhosis and type 1 hepatorenal syndrome. Hepatology. 2004;40(1):55–64. doi: 10.1002/hep.20262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Valla DC. The diagnosis and management of the budd-chiari syndrome: Consensus and controversies. Hepatology. 2003;38(4):793–803. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Perello A, Garcia-Pagan JC, Gilabert R, et al. TIPS is a useful long-term derivative therapy for patients with budd-chiari syndrome uncontrolled by medical therapy. Hepatology. 2002;35(1):132–139. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.30274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Mancuso A, Fung K, Mela M, et al. TIPS for acute and chronic budd-chiari syndrome: A single-centre experience. J Hepatol. 2003;38(6):751–754. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(03)00118-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Rossle M, Olschewski M, Siegerstetter V, Berger E, Kurz K, Grandt D. The budd-chiari syndrome: Outcome after treatment with the transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt. Surgery. 2004;135(4):394–403. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2003.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Garcia-Pagan JC, Heydtmann M, Raffa S, et al. TIPS for budd-chiari syndrome: Long-term results and prognostics factors in 124 patients. Gastroenterology. 2008;135(3):808–815. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.05.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Rozenblit G, DelGuercio LR, Savino JA, et al. Transmesenteric-transfemoral method of intrahepatic portosystemic shunt placement with minilaparotomy. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 1996;7(4):499–506. doi: 10.1016/s1051-0443(96)70790-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.DeLeve LD, Shulman HM, McDonald GB. Toxic injury to hepatic sinusoids: Sinusoidal obstruction syndrome (veno-occlusive disease) Semin Liver Dis. 2002;22(1):27–42. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-23204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Smith FO, Johnson MS, Scherer LR, et al. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunting (TIPS) for treatment of severe hepatic veno-occlusive disease. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1996;18(3):643–646. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Fried MW, Connaghan DG, Sharma S, et al. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt for the management of severe venoocclusive disease following bone marrow transplantation. Hepatology. 1996;24(3):588–591. doi: 10.1002/hep.510240321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Azoulay D, Castaing D, Lemoine A, Hargreaves GM, Bismuth H. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) for severe veno-occlusive disease of the liver following bone marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2000;25(9):987–992. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1702386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Zenz T, Rossle M, Bertz H, Siegerstetter V, Ochs A, Finke J. Severe veno-occlusive disease after allogeneic bone marrow or peripheral stem cell transplantation--role of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) Liver. 2001;21(1):31–36. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0676.2001.210105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Riggio O, Nardelli S, Moscucci F, Pasquale C, Ridola L, Merli M. Hepatic encephalopathy after transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt. Clin Liver Dis. 2012;16(1):133–146. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2011.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Jalan R, Elton RA, Redhead DN, Finlayson ND, Hayes PC. Analysis of prognostic variables in the prediction of mortality, shunt failure, variceal rebleeding and encephalopathy following the transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent-shunt for variceal haemorrhage. J Hepatol. 1995;23(2):123–128. doi: 10.1016/0168-8278(95)80325-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Chalasani N, Clark WS, Martin LG, et al. Determinants of mortality in patients with advanced cirrhosis after transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunting. Gastroenterology. 2000;118(1):138–144. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(00)70422-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Malinchoc M, Kamath PS, Gordon FD, Peine CJ, Rank J, ter Borg PC. A model to predict poor survival in patients undergoing transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts. Hepatology. 2000;31(4):864–871. doi: 10.1053/he.2000.5852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ferral H, Vasan R, Speeg KV, et al. Evaluation of a model to predict poor survival in patients undergoing elective TIPS procedures. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2002;13(11):1103–1108. doi: 10.1016/s1051-0443(07)61951-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Schepke M, Roth F, Fimmers R, et al. Comparison of MELD, child-pugh, and emory model for the prediction of survival in patients undergoing transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunting. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98(5):1167–1174. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07515.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kamath PS, Wiesner RH, Malinchoc M, et al. A model to predict survival in patients with end-stage liver disease. Hepatology. 2001;33(2):464–470. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.22172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Salerno F, Merli M, Cazzaniga M, et al. MELD score is better than child-pugh score in predicting 3-month survival of patients undergoing transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt. J Hepatol. 2002;36(4):494–500. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(01)00309-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Kovacs A, Schepke M, Heller J, Schild HH, Flacke S. Short-term effects of transjugular intrahepatic shunt on cardiac function assessed by cardiac MRI: Preliminary results. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2010;33(2):290–296. doi: 10.1007/s00270-009-9696-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Hausegger KA, Tauss J, Karaic K, Klein GE, Uggowitzer M. Use of the left internal jugular vein approach for transjugular portosystemic shunt. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;171(6):1637–1639. doi: 10.2214/ajr.171.6.9843303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Sze DY, Magsamen KE, Frisoli JK. Successful transfemoral creation of an intrahepatic portosystemic shunt with use of the viatorr device. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2006;17(3):569–572. doi: 10.1097/01.rvi.0000200054.73714.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Casado M, Bosch J, Garcia-Pagan JC, et al. Clinical events after transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt: Correlation with hemodynamic findings. Gastroenterology. 1998;114(6):1296–1303. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70436-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Tesdal IK, Filser T, Weiss C, Holm E, Dueber C, Jaschke W. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts: Adjunctive embolotherapy of gastroesophageal collateral vessels in the prevention of variceal rebleeding. Radiology. 2005;236(1):360–367. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2361040530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Haskal ZJ, Duszak R, Jr, Furth EE. Transjugular intrahepatic transcaval portosystemic shunt: The gun-sight approach. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 1996;7(1):139–142. doi: 10.1016/s1051-0443(96)70750-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Freedman AM, Sanyal AJ, Tisnado J, et al. Complications of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt: A comprehensive review. Radiographics. 1993;13(6):1185–1210. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.13.6.8290720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.LaBerge JM, Ring EJ, Gordon RL, et al. Creation of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts with the wallstent endoprosthesis: Results in 100 patients. Radiology. 1993;187(2):413–420. doi: 10.1148/radiology.187.2.8475283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Suhocki PV, Smith AD, Tendler DA, Sexton DJ. Treatment of TIPS/biliary fistula-related endotipsitis with a covered stent. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2008;19(6):937–939. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2008.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.LaBerge JM, Ferrell LD, Ring EJ, et al. Histopathologic study of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 1991;2(4):549–556. doi: 10.1016/s1051-0443(91)72241-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Bureau C, Garcia-Pagan JC, Otal P, et al. Improved clinical outcome using polytetrafluoroethylene-coated stents for TIPS: Results of a randomized study. Gastroenterology. 2004;126(2):469–475. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Hausegger KA, Karnel F, Georgieva B, et al. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt creation with the viatorr expanded polytetrafluoroethylene-covered stent-graft. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2004;15(3):239–248. doi: 10.1097/01.rvi.0000116194.44877.c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Sanyal AJ, Freedman AM, Shiffman ML, Purdum PP, 3rd, Luketic VA, Cheatham AK. Portosystemic encephalopathy after transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt: Results of a prospective controlled study. Hepatology. 1994;20(1 Pt 1):46–55. doi: 10.1016/0270-9139(94)90133-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Hauenstein KH, Haag K, Ochs A, Langer M, Rossle M. The reducing stent: Treatment for transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt-induced refractory hepatic encephalopathy and liver failure. Radiology. 1995;194(1):175–179. doi: 10.1148/radiology.194.1.7997547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Riggio O, Angeloni S, Salvatori FM, et al. Incidence, natural history, and risk factors of hepatic encephalopathy after transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt with polytetrafluoroethylene-covered stent grafts. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103(11):2738–2746. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.02102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Maleux G, Perez-Gutierrez NA, Evrard S, et al. Covered stents are better than uncovered stents for transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts in cirrhotic patients with refractory ascites: A retrospective cohort study. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2010;73(3):336–341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Haskal ZJ, Cope C, Soulen MC, Shlansky-Goldberg RD, Baum RA, Redd DC. Intentional reversible thrombosis of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts. Radiology. 1995;195(2):485–488. doi: 10.1148/radiology.195.2.7724771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Sanyal AJ, Freedman AM, Purdum PP, Shiffman ML, Luketic VA. The hematologic consequences of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts. Hepatology. 1996;23(1):32–39. doi: 10.1002/hep.510230105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Sanyal AJ, Reddy KR. Vegetative infection of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts. Gastroenterology. 1998;115(1):110–115. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70371-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Zizka J, Elias P, Krajina A, et al. Value of doppler sonography in revealing transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt malfunction: A 5-year experience in 216 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000;175(1):141–148. doi: 10.2214/ajr.175.1.1750141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]