Abstract

It is well accepted that recognition memory reflects the contribution of two separable memory retrieval processes, namely recollection and familiarity. However, fundamental questions remain regarding the functional nature and neural substrates of these processes. In this article, we describe a simple quantitative model of recognition memory (i.e., the dual-process signal detection model) that has been useful in integrating findings from a broad range of cognitive studies, and that is now being applied in a growing number of neuroscientific investigations of memory. The model makes several strong assumptions about the behavioral nature and neural substrates of recollection and familiarity. A review of the literature indicates that these assumptions are generally well supported, but that there are clear boundary conditions in which these assumptions break down. We argue that these findings provide important insights into the operation of the processes underlying recognition. Finally, we consider how the dual-process approach relates to recent neuroanatomical and computational models and how it might be integrated with recent findings concerning the role of medial temporal lobe regions in other cognitive functions such as novelty detection, perception, implicit memory and short-term memory.

Keywords: recognition, hippocampus, dual-process, signal-detection, threshold

I enter a friend’s room and see on the wall a painting. At first I have the strange, wondering consciousness, ‘surely I have seen that before,’ but when or how does not become clear. There only clings to the picture a sort of penumbra of familiarity, - when suddenly I exclaim: “I have it, it is a copy of part of one of the Fra Angelicos in the Florentine Academy - I recollect it there!”

from The Principles of Psychology (p 658) by William James

INTRODUCTION

The capability to remember our past is one of the most remarkable and mysterious cognitive abilities we possess. As illustrated above by the passage from William James, introspection suggests that recognition memory of stimuli we have encountered before can be based on recollection or familiarity. Recollection reflects the retrieval of qualitative information about a specific study episode, such as when or where an event took place, whereas familiarity reflects a more global measure of memory strength or stimulus recency. Results from behavioral, animal, neuropsychological, electophysiological, and neuroimaging studies have now provided strong support for the distinction between recollection and familiarity (for reviews, see Yonelinas, 2002; Aggleton and Brown, 2006; Diana et al., 2007), and have led to the development of a number of dual-process theories of recognition (e.g., Atkinson and Juola, 1974; Mandler, 1980; Jacoby, 1991; Yonelinas, 1994; Aggleton and Brown, 1999; Reder et al., 2000; Kelley and Wixted, 2001; Rotello et al., 2004).

One quantitative model that has been used extensively in behavioral studies of recognition and is now being increasingly applied in neuroscience studies, is the “dual-process signal detection model” (DPSD; Yonelinas, 1994). In the DPSD model, familiarity is assumed to reflect a signal detection process whereby the memory strength of studied items is temporarily increased, enabling individuals to select the most familiar items as having been recently studied. On the other hand, recollection reflects a threshold retrieval process whereby individuals recall detailed qualitative information about studied events (e.g., remembering where or when a painting was seen before). Motivated in part by prior work showing that amnesics exhibit severe deficits in their ability to recollect details about prior events, but often show remarkably preserved familiarity-based discrimination (Huppert and Piercy, 1978), the DPSD model assumes that the hippocampus is particularly important in forming and retrieving the arbitrary associations that support recollection, whereas familiarity depends on regions outside the hippocampus and reflects a byproduct of repeated neural processing (e.g., Yonelinas et al., 1998, 2002).

One of the strengths of the DPSD model is that it provides a single theoretical framework for integrating and understanding results from a wide variety of test methods currently used in the recognition memory literature, including receiver operating characteristic (ROC), remember/know, source, and associative recognition tests (each of these methods is described in more detail below) (Yonelinas, 2002; Yonelinas and Parks, 2007). In contrast, earlier models of recognition memory are not able to account for results across these various different recognition tests, although they might provide an adequate account of a single type of recognition test. For example, it is now well established that the unequal-variance signal detection model, which is often treated as the classical single-process model (e.g., Egan, 1958; Donaldson, 1996; Dunn, 2004), does not provide an adequate account for results from associative or source memory tests (e.g., Kelley and Wixted, 2001; Decarlo, 2002; Rotello et al., 2004; for a review see Yonelinas and Parks, 2007), although it can account for results from some item recognition tests. For this reason, we do not spend a great deal of time discussing those earlier models here (for the reader interested in assessments of these various models in light of behavioral and neural studies, see Yonelinas and Parks, 2007, 2008).

As useful as the DPSD model has proven to be, it makes a number of very strong assumptions about the nature of recollection and familiarity, and these assumptions are considered by some to be quite controversial. Critically evaluating these assumptions is essential for accurately characterizing the processes involved in recognition memory, and for interpreting the results of studies that have made use of the model. In the current paper, we evaluate the three most controversial assumptions of the model: (i) the two retrieval processes differ in the sense that recollection is a threshold process, whereas familiarity is a signal detection process; (ii) familiarity can support accurate associative and source recognition under certain conditions; and (iii) the hippocampus is critical for recollection, but not familiarity (for earlier discussions of the model see Yonelinas, 2001a, 2002). We review the empirical evidence and show that these assumptions are well supported. Nonetheless, as will be discussed, there are a number of findings that indicate that there are important boundary conditions for when the model’s assumptions will hold true. Finally, we describe several emerging issues that prompt us to speculate about how the model might be further developed, and how it may be integrated with current ideas about the role of the medial temporal lobes (MTLs) in other cognitive functions such as perception and short-term memory.

RECOLLECTION IS A THRESHOLD RETRIEVAL PROCESS, WHEREAS FAMILIARITY IS A SIGNAL DETECTION PROCESS

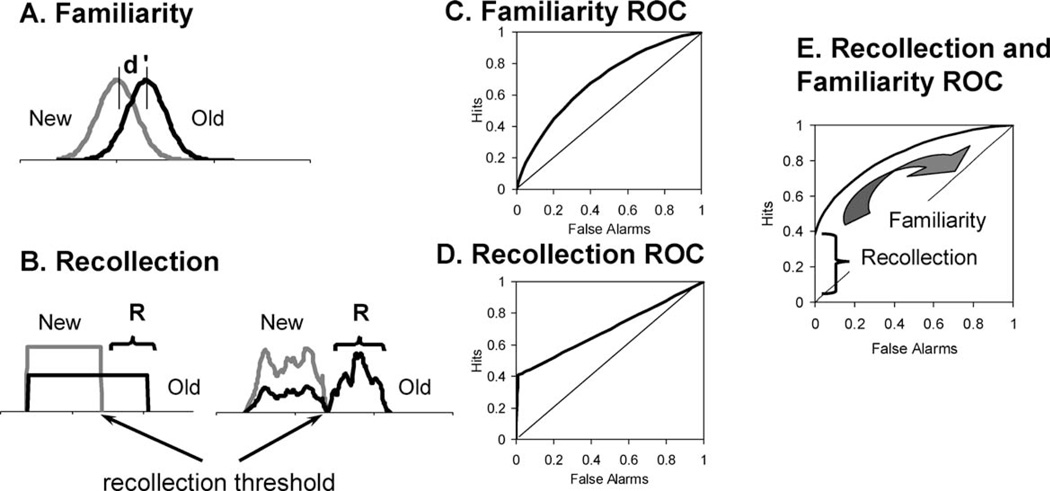

One of the core assumptions of the DPSD model is that recollection and familiarity differ in terms of the type of memory information that they provide. Familiarity is assumed to reflect the assessment of “quantitative” memory strength in a manner similar to that described by signal detection theory (Fig. 1A). Thus, all items have some familiarity value, but items that have been recently studied are, on average, more familiar than items that were not studied. In contrast, recollection reflects a threshold retrieval process whereby “qualitative” information about a previous event is retrieved. Recollection is not well described by a signal detection process because individuals do not recollect information about every event that they have studied. Rather, on some trials, recollective strength may fall below a threshold, such that recollection fails to provide any discriminating evidence that an item has been previously encountered. For this reason, recollection is assumed to reflect a threshold process, as illustrated in Figure 1B. It is important to note that threshold theory does not make any specific commitment about the shape of the recollective strength distributions (i.e., although the distributions are often illustrated as being square, they can take on any number of different shapes). The critical point is that there is a recollective threshold below which individuals are not recollecting any information that discriminates between old and new items—something that cannot happen according to signal detection theory.

FIGURE 1.

The dual process signal detection model. (A) Familiarity reflects a signal detection process whereby new items form a Gaussian distribution of familiarity values. Old items are on average more familiar than new items (d′ is the distance between the means of the two equal-variance distributions), and thus individuals can discriminate between old and new items by selecting a response criterion and accepting the more familiar items as having been studied. (B) Recollection reflects a threshold process whereby some proportion of studied items will be recollected (Recollection (R) is measured as a probability) whereas some items will fall below the recollective threshold (i.e., some items will not be recollected). Threshold theory does not specify the shape of the recollective strength distributions, but two possible types of distributions are illustrated. Receiver operating characteristics produced by the familiarity process (C) and the recollection process (D). Familiarity produces curved functions that are symmetrical along the chance diagonal, whereas recollection produces a ‘hockey stick’ function that is linear for most of the range. ROCs are generated by varying the response criterion from very strict such that only the strongest items are accepted as old to very lax such that more items are accepted as old. (E) ROCs produced when both recollection and familiarity contribute to performance. The intercept provides a measure of recollection whereas the degree of curvilinearity provides a measure of familiarity.

The signal detection and threshold assumptions are consistent with recent neurocomputational models of recognition (e.g., Norman and O’Reilly, 2003; Elfman et al., 2008 also see Murdock, 1974). For example, if familiarity arises as a product of gradual changes in distributed cortical networks involved in the identification or categorization of incoming stimuli, the memory strength distributions associated with old and new items will be approximately Gaussian and can be equal in variance. In contrast, if recollection is based on the pattern separation and completion mechanisms believed to underlie hippocampal functioning, then recollected information tends to be strongly retrieved for some proportion of the items, whereas little or no recollected information is retrieved for other items, thus producing threshold strength distributions (for potential exceptions, see Elfman et al., 2008).

To test the model’s assumptions, it is necessary to specify how these underlying retrieval processes mediate overt behavior. Below, we focus on how the model has been applied to the most common recognition memory paradigms including item recognition, remember/know, source, and associative recognition tests.

In item recognition tests, individuals must discriminate between old and new items. It is assumed that individuals will respond “old” to an item if they can recollect qualitative information about the specific study event, or if the item is judged to be sufficiently familiar. If individuals are required to rate confidence, as is common in ROC studies, then it is assumed that recollection will lead to relatively high confidence responses, whereas familiarity strength will be mapped monotonically across a wider range of confidence, with the more familiar items leading to more confident recognition responses. The idea is that if one can remember specific details about studying an item, then one should be quite sure it was studied, particularly when compared to items that are only familiar in the absence of any recollected information. Note that although recollection is assumed to be associated with higher confidence judgments on average compared to familiarity, familiarity can also support high confidence responses. Thus, high confidence responses cannot be used as a process pure measure of recollection.

If an individual were to rely exclusively on familiarity, changes in the response criterion would produce a curved, symmetrical ROC as in Figure 1C. In contrast, relying exclusively on recollection would produce a hockey-stick shaped ROC with a major linear component, as in Figure 1D. If, as is typically the case, performance reflects the contribution of both recollection and familiarity, the resulting ROC would be a mixture of the two previous ROCs, as in Figure 1E. Familiarity leads the ROC to exhibit an inverted U-shape, whereas recollection pushes the curve up so that it intersects the y-axis and then drops, resulting in an ROC that is asymmetrical along the chance diagonal. On the basis of these assumptions, one can develop a quantitative measurement model which can then be fit to observed recognition confidence ROCs to derive quantitative estimates of recollection and familiarity. The method is analogous to conducting a linear regression, but rather than estimating slope and intercept, one estimates familiarity in terms of d′ (i.e., the degree of curve in the ROC) and recollection (i.e., the intercept at the y-axis) (e.g., see Macho, 2002; Yonelinas, 1994, 2002; Yonelinas and Parks, 2007).

Consistent with the DPSD model, empirical item recognition ROCs are almost always curved and asymmetrical (see Fig. 1E, for reviews, see Ratcliff et al., 1992; Yonelinas and Parks, 2007). Moreover, the model provides a very good fit for item recognition ROCs, and rarely deviates from the observed ROC points by more than one or two percent. In addition, manipulations expected to lead to relatively selective increases in recollection lead the ROCs to become more asymmetrical, whereas manipulations expected to increase familiarity lead the ROCs to become more curved (e.g., Yonelinas 1994, 2002; Koen and Yonelinas, in press). Observed dissociations between overall performance level and the degree of ROC asymmetry, rule against simple strength accounts of recognition (Yonelinas, 1994). Moreover, as far as we know, no other viable explanations have been developed to account for the systematic relationship that is seen between ROC shape and the contributions of recollection and familiarity.

In a remember/know (RK) test (e.g., Tulving, 1985) individuals are required to indicate if their recognition responses are based on recollection of qualitative details (i.e., remembering) or on the basis of familiarity in the absence of recollection (i.e., knowing). If individuals are aware of the products of the recollection and familiarity processes, and if they comply with the test instructions, these introspective reports can be used to assess recollection and familiarity. That is, ‘remember’ responses can be used as a measure of recollection (R), and ‘know’ responses can be used as a measure of familiarity in the absence of recollection (K = F(1 − R)) (Yonelinas and Jacoby, 1995). Note that although individuals typically make very few remember responses to new items (i.e., false remember rates are often between 0 and 5%) recollection accuracy can be measured under a threshold assumption by subtracting false remember from correct remember responses. Estimates of familiarity for the old and new items can be used to calculate d’, which is the distance between the old and new item familiarity distributions.

Although there is good reason to be cautious when interpreting introspective reports about underlying psychological processes, an extensive body of research has now shown that results from these methods typically converge quite well with more objective measures of recollection and familiarity (Yonelinas, 2001b, 2002). However, remember/know instructions can sometimes be misunderstood by individuals, and under some conditions individuals make ‘remember’ responses even when they cannot report any specific details about the study event (Baddeley et al., 2001; Yonelinas, 2001b; Rotello et al., 2005). Under such conditions, the procedure cannot be expected to accurately separate recollection and familiarity. This has likely been responsible for much of the current controversy regarding whether remember/know reports reflect recollection and familiarity, or just memory strength (e.g., Donaldson, 1996; Dunn, 2004). For this reason, it is important to include some manipulation check, such as a training procedure in which individuals provide verbal justifications of their remember responses, to verify that individuals understand the instructions (e.g., Yonelinas et al., 2001b; Rotello et al., 2005).

In source and associative tests, individuals must indicate the source that was associated with an item at study (e.g., was the item originally studied in location A or B; or was the item originally studied in list A or B?), or indicate whether a pair of items were associated with each other at encoding (e.g., were A and B studied together?). Recollection and familiarity both contribute to performance on these types of tasks, and thus confidence responses can be used to plot ROCs to estimate recollection and familiarity, as in item recognition.

However, source and associative tests differ from item recognition in several important ways. First, because all of the critical test items were studied, familiarity is expected to be less useful in supporting these discriminations than in item recognition. So in general, estimates of familiarity should be lower in tests of source and associative recognition than in tests of item recognition. In addition, with source and associative tests, a second recollection parameter is needed because there are two different types of old items (e.g., the probability of recollecting items from source A may be different from the probability of recollecting items from source B; or the probability of recollecting an intact pair may be different than the probability of recollecting that a pair is rearranged).

One limitation of source and associative tests that is often overlooked is that these tests provide very restrictive measures of recollection compared to item recognition tests. That is, individuals may remember aspects of the study event that do not support the discrimination required by the test, and this would not be captured in the estimate of recollection. For example, in a test of object location, individuals may remember what they thought about when they studied the object, but may be unable to remember its location. This has been referred to as “noncriterial recollection” (Yonelinas and Jacoby, 1996; Parks, 2007), and it can bias estimates of recollection and familiarity, and can play havoc with imaging or patient studies that use very restrictive measures of source memory to assess recollection and familiarity (e.g., Wais et al., 2010). Thus, when using tests such as source memory to measure recollection and familiarity, it is important to use a task in which individuals are very likely to recollect the criterial information if they recollect any information about a particular item (for additional discussion of noncriterial recollection, see Yonelinas and Jacoby, 1996).

A misunderstanding that has led to a great deal of confusion in the source memory literature is the belief that threshold models assume that recollective strength is not continuous, or that it is all-or-none in the sense that individuals recollect either everything about a study event or nothing about the event. Thus, findings that individuals can recollect more or fewer aspects of a study event, or the fact that items that are associated with correct source recollection can lead to different levels of recognition confidence, have sometimes been interpreted as evidence against threshold-based models (Slotnick et al., 2000; Slotnick and Dodson, 2005; Wixted, 2007; Mickes et al., 2009). However, this assumption is not true of threshold theories in general, and it is most definitely not true of the DPSD model. In fact, threshold models assume that memory strength is continuous and varies from weak to strong, but that there is a memory strength threshold below which the process fails to discriminate between studied and nonstudied items. Recollection can vary in several ways. For instance, individuals may recollect various different aspects about a study event. As an example, if recollection is measured using an easy discrimination task (e.g., what list was the item studied in?) the probability of recollection is much higher than when tested under conditions in which the recollective discrimination is very difficult (e.g., what was the size of the font the item was studied in?; Dodson and Johnson, 1996; Yonelinas and Jacoby, 1996). In addition, different types of recollection may be differentially diagnostic and so may support different levels of confidence (cf. Yonelinas, 1999).

The DPSD model offers a unified account for studies of remember/know recognition, as well as ROC studies of item, source, and associative recognition. But what direct evidence is there supporting the threshold and signal detection assumptions underlying the model? Below, we describe five relevant lines of evidence.

Flattened Source and Associative ROCs

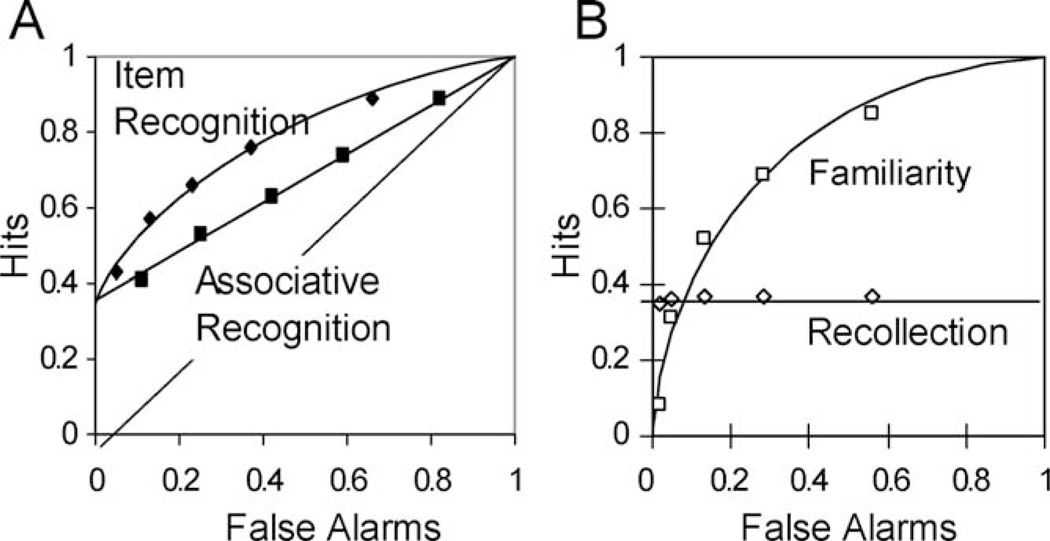

The strongest support for any scientific theory is when it generates novel predictions that are subsequently confirmed experimentally. One early example of this with the DPSD model was that it predicted that under conditions in which recollection is expected to dominate performance, the resulting ROCs should be flatter (or more linear) than a pure signal detection process would predict (Fig. 1D). In 1997, this type of ROC had never been reported, and the general consensus was that signal detection theory provided a very good account for recognition ROCs. In the context of this consensus, we tested the contradictory prediction of the DPSD model by examining ROCs in an associative recognition memory test in which individuals studied pairs of words and were required to discriminate between intact and rearranged pairs at test. The expectation was that familiarity should be less useful in this test than in a standard item recognition test because all the words were familiar from the study phase. As predicted, the associative ROCs were very linear in probability space, whereas the item recognition ROCs exhibited a pronounced curve (Fig. 2A). Note that a common way of assessing the ROC shape is to plot ROCs in z-space. The observed associative memory zROCs exhibited a pronounced U-shape in z-space, in contrast to the linear zROCs predicted by a pure signal detection process. Flattened ROCs were subsequently observed in tests of source memory, in which individuals were required to discriminate between items spoken by a male or female voice at study, or to remember the spatial locations of studied items (Yonelinas, 1999). This pattern of results has now been replicated in well over 50 published experiments (for a review, see Yonelinas and Parks, 2007; for similar results in studies of rats see Sauvage et al., 2008).

FIGURE 2.

(A) ROCs in tests of item recognition are curved, whereas ROCs in test of associative recognition tests are much flatter (from Yonelinas, 1997). (B) Item ROCs plotted separately for items related to recollection and familiarity as measured using the remember/know procedure (from Yonelinas, 2001b). As response criterion is relaxed familiarity increases in a curvilinear manner in agreement with an equal variance signal detection model, whereas recollection supports high confidence responses and remains relatively constant.

One criticism of these results has been that the source and associative ROCs often still exhibit some degree of curvilinearity, which has been taken as evidence against the DPSD model (Slotnick et al., 2000; Slotnick and Dodson, 2005; Wixted, 2007). The argument is that source tests should provide a pure measure of recollection, and if recollection is a threshold process as the model assumes, then the source and associative ROCs must be perfectly linear. However, as discussed in more detail below, these tests are not expected to provide process-pure measures of recollection, since there are various ways in which familiarity can support source and associative recognition performance (for earlier discussion of this point see Yonelinas et al., 1999 and Yonelinas, 1999). Thus, the ROCs are not expected to be perfectly linear. In fact, if the ROCs were perfectly linear then there would be no need to postulate a dual-process model for these tests, because a single recollection process would be sufficient to account for recognition performance. Another argument has been that the source ROC results arise not because recollection is a threshold process at retrieval, but because the encoding of information that supports source recollection judgments can sometimes fail entirely, resulting in a mixture of recollected and nonrecollected items (Slotnick and Dodson, 2005). However, to argue that recollection can sometimes fail is effectively the same thing as arguing that recollection strength can fall below a threshold, so this notion is not at odds with the DPSD model.

Plotting Recollection and Familiarity ROCs

Another way of assessing the threshold and signal detection assumptions of the DPSD model is to use methods designed to separate the effects of recollection and familiarity, and examine the ROCs produced by these two processes. For example, in an item recognition test, if individuals are required to make remember/know responses in addition to recognition confidence judgments, one can plot confidence ROCs separately for recollected and familiar items. These studies have shown that recognition responses associated with remembering are primarily assigned the highest confidence responses, and correct remember responses do not increase as the response criterion is relaxed (Fig. 2B). In contrast, correct familiarity-based responses do increase gradually and produce the symmetrical, curved ROCs that are expected if familiarity was an equal-variance signal detection process (Yonelinas 2001b; Koen and Yonelinas, in press). Similar results have also been observed when recollection is measured using source discrimination paradigms (Yonelinas, 1994, 2002).

Second-choice Recognition Responses

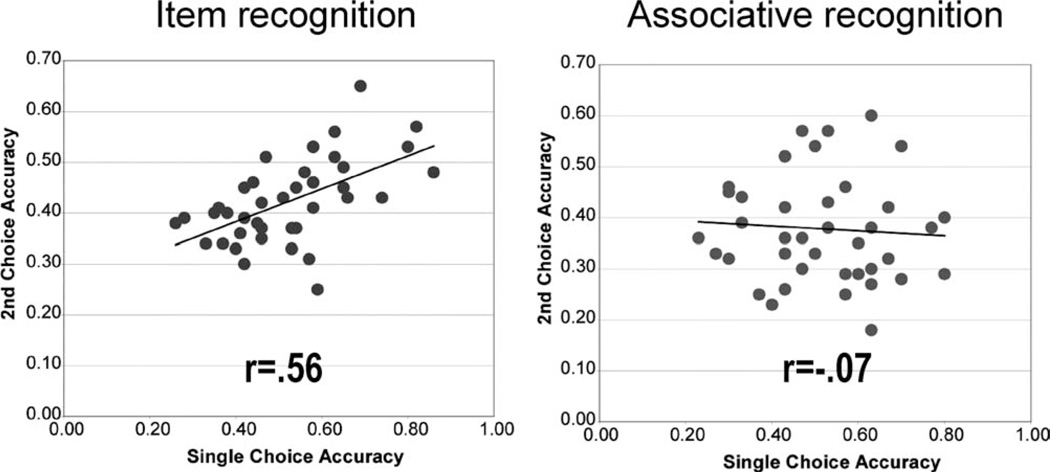

A different way of assessing the threshold and signal detection assumptions is to use a second-choice forced-choice procedure (Swets, 1964; Parks and Yonelinas, 2009). Recognition is assessed using a four-alternative forced-choice recognition test in which individuals make a first choice and a second choice in case their first response is incorrect. If performance reflects the assessment of a signal detection process, then on some trials the strongest of the four alternatives may be a nonstudied item. On these occasions, the individual’s first choice will be incorrect, but familiarity strength will still be useful in making the second choice, and second-choice accuracy will therefore be above chance. Moreover, second-choice accuracy should be correlated with first choice accuracy across individuals because presumably both responses are based on the same underlying familiarity strength distributions. In contrast, if performance relies heavily on a high threshold recollective process, then when recollection occurs, an individual’s first choice will be accurate, and second-choice responses will reflect cases in which recollection had failed. Consequently, second-choice accuracy should be poor, and not correlated with first-choice accuracy.

In a study examining first- and second-choice accuracy (Parks and Yonelinas, 2009), second-choice performance in a test of item recognition increased as a function of performance on the first choice, as expected if performance was relying heavily on a signal detection process (Swets et al., 1964). In contrast, in a test of associative recognition, second-choice performance was close to chance and was not strongly related to first-choice performance, as expected if performance was dominated by a threshold process (Fig. 3).

FIGURE 3.

Second-choice accuracy plotted against single-choice accuracy in 4-alternative forced choice test of item recognition and associative recognition (Parks and Yonelinas, 2007). Second and single-choice scores in item recognition are correlated across subjects as indicative of a signal detection process. In contrast, in associative recognition second and single-choices are unrelated as expected if performance reflected a high threshold process.

ROCs in Patients With Amnesia

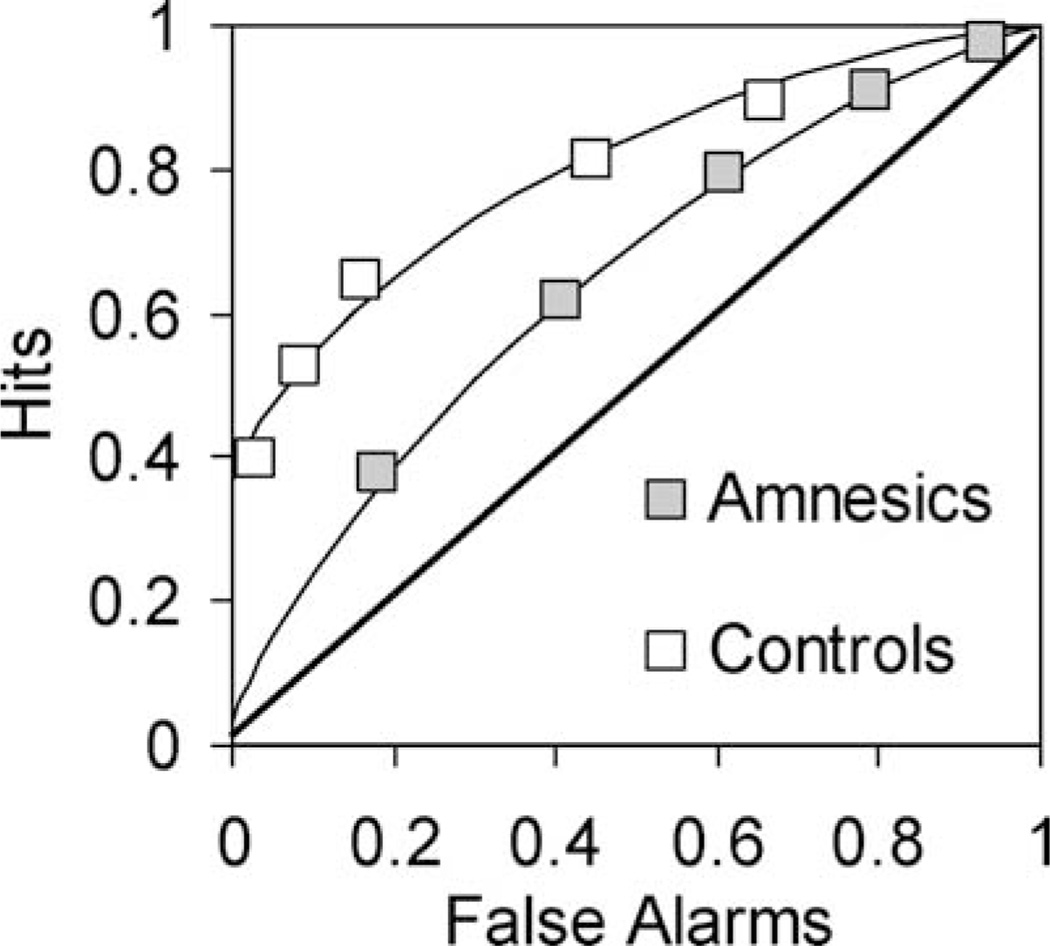

The DPSD model predicts that if familiarity reflects an equal-variance signal detection process, then patients with severe recollection impairments should produce ROCs that are curved and symmetrical (Fig. 1C). This prediction was initially tested by examining recognition ROCs in patients with amnesia with extensive medial temporal lobe (MTL) damage (Yonelinas et al., 1998). The study showed that in contrast to healthy controls, who exhibited asymmetrical ROCs, the amnesics’ functions were curved and symmetrical (see Fig. 4A). Importantly, even when performance was reduced in a control group by decreasing study duration to match patients’ performance, controls still exhibited asymmetrical ROCs, indicating that the resulting symmetrical ROCs in amnesia were not simply a consequence of lower levels of performance. The results indicate that amnesia cannot be described as a reduction in overall memory strength; rather it involves the loss of the memory component that underlies the asymmetry observed in the ROCs of healthy individuals (i.e., recollection). Note that even if one adopted an unequal-variance signal detection model, the implications of the amnesia ROC results are largely the same. That is, amnesia does not eliminate the use of familiarity in recognition, rather it eliminates the process or component that adds extra variance to the old items. The finding that MTL amnesia leads to symmetrical item recognition ROCs has now been replicated numerous times (e.g., Yonelinas et al., 2002; Aggleton et al., 2005; Cipolotti et al., 2006; Wais et al., 2006; Kirwan et al., 2010).

FIGURE 4.

Item recognition ROCs in patients with MTL damage and healthy control subjects (Yonelinas et al., 1998). Healthy control subjects exhibit asymmetrical ROCs, whereas MTL amnesic patients produce symmetrical item recognition ROCs, indicating that the recollection process producing ROC asymmetry is effectively eliminated.

Note that the only apparent exceptions to this rule are quite informative. First, a group of severely impaired amnesic patients were tested in a standard long-term memory item recognition test, and produced symmetrical ROCs (Wais et al., 2006); but when they were tested using very short study lists (i.e., 10 words) the ROCs became slightly asymmetrical. The results do not challenge the notion that familiarity is an equal-variance signal detection process, but they suggest that with very short lists, amnesics can maintain and recollect two to three words.

A second exception comes from a patient with an unusual MTL lesion (i.e., the lesion did not impact the hippocampus, as is usually the case in amnesia, but rather affected the surrounding PRc). In collaboration with Stefan Kohler and Ben Bowles (Bowles et al., 2007), we recently had the opportunity to test this patient, who appeared on the basis of remember/know reports to have suffered a selective deficit in familiarity. One prediction of the DPSD model that had been difficult to assess before then was that if one could find an individual who had a selective deficit in familiarity, the individual’s item memory ROC should be asymmetrical and flatter than what is typically observed in item recognition. When this patient’s item recognition ROCs were examined, they were indeed found to be flattened, precisely as predicted by the DPSD model. While one must always be cautious in interpreting single case reports, these results converge with a great deal of earlier work indicating that recollection does operate like a threshold process. Furthermore, the double dissociation between this patient and the amnesics who demonstrate impaired recollection but spared familiarity adds support to the notion that these processes are indeed separable, behaviorally and neurally.

When the Threshold Nature of Recollection Breaks Down: Identifying Boundary Conditions

As mentioned earlier, threshold models do not make explicit assumptions about the precise shape of the recollection distributions (i.e., they could take on any number of different shapes, as shown in Fig. 1B). In the past, we have refrained from speculating about the shape of the recollection distribution for two primary reasons. The first reason is that the shape of the recollection distribution does not make that much of a difference. As long as recollection leads to recognition responses that are of equal or higher confidence as those produced by familiarity, then the shape of the above-threshold recollected distribution has no impact on the shape of the observed recognition ROCs. The second reason is that it is particularly difficult to empirically assess the shape of the recollective distribution. The problem is that in standard item recognition memory studies, the false recollection rate is extremely low, and this limits ones ability to make inferences about the shape of the underlying strength distributions. That is, one can infer the shape of the familiarity distributions because one can plot familiarity- based hits against familiarity-based false alarms across a wide range of false alarms. However, because false recollection rates typically only vary from 0% to about 5%, one cannot draw strong conclusions about the shape of the underlying distributions.

However, others have speculated about what the shape of the recollection distribution might look like. For example,Sherman et al. (2003) extended the DPSD model by proposing a “variable recollection dual-process model” in which recollection is assumed to be a threshold process, but the items that are above the recollective threshold form a Gaussian distribution (for related ideas see Macho, 2002; Healy et al., 2005; Sherman, 2010; Wixted, 2010). Because recollection is assumed to provide stronger evidence than familiarity, it leads to higher confidence responses than familiarity. However, some recollected items can be associated with lower levels of confidence depending on the strength and the variance of the recollection distribution. The model is able to produce U-shaped zROCs like those generated by the DPSD model, but it is also able to produce s-shaped zROCs. Although there is little evidence of s-shaped zROCs as of yet, one study reported such a zROC in individuals under the influence of scopolamine (Sherman et al., 2003). Future work exploring the generalizability of these results may be extremely useful in informing us about the shape of the recollective distribution.

In a related series of studies, we have found that there are conditions under which the threshold nature of recollection seems to break down. That is, under conditions of high feature overlap, the threshold strength distributions produced by recollection appear to become more Gaussian in nature. For example, under conditions in which all of the studied items are made highly similar (e.g., a study list consisting of 200 photos of very similar suburban houses), source recognition ROCs (i.e., was the picture initially on the left or right side of the screen?) become much more curved than is typically the case in tests of source memory (Elfman et al., 2008).

This discovery was based on predictions of the complementary learning systems model (CLS)—a neurocomputational model of the MTL, developed by Norman and O’Reilly (2003; also see Norman, this issue). The model assumes that the hippocampus supports recollection of episodic associations, whereas the surrounding MTL cortex supports familiarity-based recognition. The model is in agreement with the DPSD model in the sense that recollection generally acts as a threshold process (i.e., some studied items lead to accurate pattern completion of episodic associations, whereas pattern completion fails entirely for other items), whereas familiarity acts like a signal detection process. Note that their model was not designed to produce threshold or signal detection outputs; rather the threshold and signal detection properties were found to emerge naturally from the neural properties of the MTL regions they were modeling.

The results from the feature overlap studies suggest that there are important boundary conditions beyond which the threshold nature of recollection breaks down, and it starts to approximate Gaussian distributions. We believe that these results point to a critical shortcoming of the DPSD model, which is that it makes no explicit assumptions about the representations and mechanisms underlying the hippocampal network. Although these high feature overlap conditions may seem fairly artificial, the success of the Norman and O’Reilly model in predicting conditions under which the threshold assumption will and will not hold attests to the utility of adopting a detailed neurocomputational approach. We believe that additional work with this type of model will continue to be fruitful, particularly as we gain a better understanding of the function of the different subregions within the hippocampus. In addition, it seems to us that neurocomputational models and macrolevel models like the DPSD model provide complementary insights, and together they provide great promise in furthering our understanding of the processes involved in recognition memory.

FAMILIARITY CAN SUPPORT MEMORY FOR NOVEL ASSOCIATIONS: SOURCE AND ASSOCIATIVE TESTS DO NOT PROVIDE PROCESS-PURE MEASURES OF RECOLLECTION

As previously discussed, tests of source and associative recognition rely heavily on recollection, whereas tests of item recognition rely to a great extent on familiarity. However, neither of these tests can be relied upon to provide process-pure measures of recollection or familiarity. For example, if individuals can recollect details about a study event, they can use this as a basis for item recognition judgments. Conversely, it is now apparent that familiarity can contribute to source and associative tests. Two general examples are described below.

Differences in Source Strength

Perhaps the most obvious way in which familiarity can contribute to source recognition is when the familiarity of the items from two different sources is unequal. For example, if memory is better for items from one of the sources, then familiarity can serve as a basis for accurate source decisions. Evidence for this was obtained in a study in which one source was studied before another (e.g., list 1 was spoken by a male voice, followed by list 2, which was spoken by a female voice; Yonelinas, 1999). The source memory ROCs were generally quite linear, but many individuals exhibited curved ROCs, suggesting that familiarity-based memory was useful in discriminating between the two sources. The curved source ROCs might have occurred because items from list 2 were more familiar than items from list 1, and thus list 2 items were attributed to the list 2 source (e.g., female voice) on the basis of familiarity. This possibility was tested in an experiment in which the first source was presented 5 days before the second source to induce large differences in the familiarity of the two different sources. The resulting ROCs were highly curved, as expected if familiarity made a significant contribution to source decisions (Yonelinas, 1999).

Although it is tempting to try to design experiments to match overall memory for the different sources to eliminate familiarity-based discrimination, this approach is unlikely to be completely successful. First, some individuals are likely to have better memory for one source, whereas other individuals will have better memory for the other. Thus, even if overall memory for the two sources is well matched at the group level, familiarity may still be useful in source discriminations at the individual level. Moreover, as we describe next, other factors can lead to familiarity-based source and associative recognition.

Unitization of Item–Item or Item–Source Associations

Familiarity can contribute to accurate associative and source recognition judgments when pairs of items, or items and sources, are “unitized” (i.e., treated as single items rather than as arbitrary pairings; Yonelinas et al., 1999; Yonelinas, 1999; Quamme et al., 2007). The assumption underlying the DPSD model is that the familiarity of a test “item” is used to support familiarity-based recognition, whereas recollection serves to retrieve the related study source or some association made during study. Familiarity should be able to support recognition of arbitrary associations if individuals treat the two items, or the item and source, as a single unitized item, rather than as two separate items that need to be bound together. This prediction has now been verified in a number of behavioral, patient, and neuroimaging studies.

Arbitrary associations can be unitized in various ways. For example, in an associative recognition test for random word pairs, if the word pairs are encoded as novel compound words (e.g., CLOUD-LAWN: A yard used for sky-gazing) the two words are treated as a single conceptual unit. In this way, the familiarity of the concept cloud-lawn should be useful in discriminating between intact and rearranged word pairs in an associative test. In contrast, if the words are treated as separate items (e.g., He watched the CLOUD float by as he sat on the LAWN), the meanings of the two words remain relatively separate, and thus familiarity should be less useful in supporting associative recognition. Similarly, in a test of source memory in which individuals must remember the background color that items were presented on (e.g., red or green), items and sources that are encoded as single units (e.g., the ELEPHANT was RED because it had a sunburn) should be supported by familiarity to a greater degree then when the item and source are treated as separate entities (e.g., the ELEPHANT stood by the RED stop sign). In the first case, the source becomes a feature of the item to be remembered, whereas in the second, the source and item are two separate pieces of information.

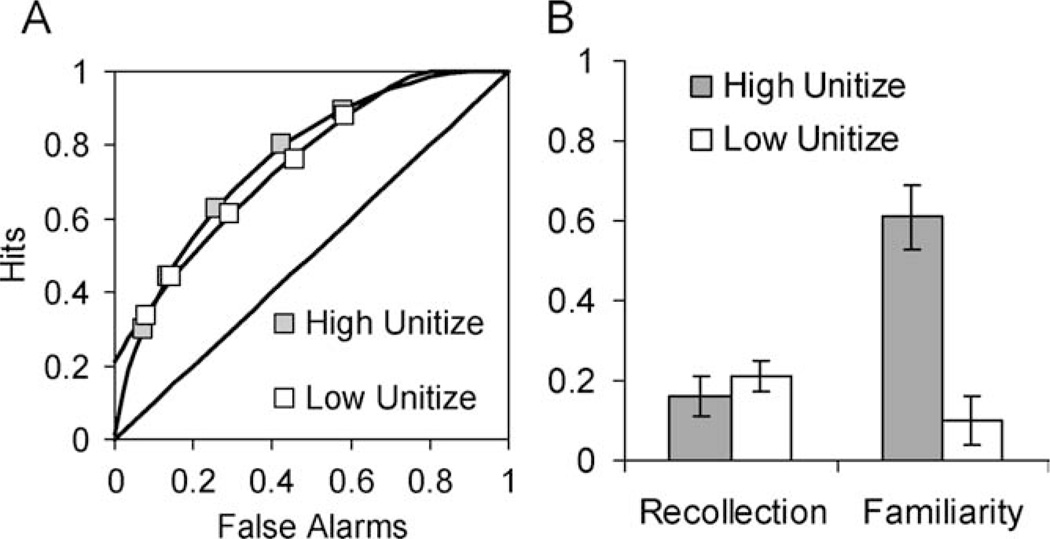

In behavioral ROC studies, encoding conditions that promote unitization lead to increased curvilinearity in the observed ROCs, and to an increase in parameter estimates of familiarity (Figs. 5A,B). This has been observed in studies of source recognition (Diana et al., 2008, 2010), associative recognition of word pairs (e.g., Quamme et al., 2007; Haskins et al., 2008; for related ERP results see Rhodes and Donaldson, 2007, 2008), and associative recognition for intact and rearranged faces (Yonelinas et al., 1999). In addition to these ROC results, similar conclusions were reached using the second-choice procedure in an associative recognition test (Parks and Yonelinas, 2009).

FIGURE 5.

(A) Source recognition ROCs for items encoded under high and low unitization conditions (Diana et al., 2008). Encoding that promotes unitization leads the source ROCs to become more curved, and (B) leads to an increase in familiarity-based source memory discrimination.

If unitization enables familiarity to support associative recognition, then unitization should attenuate the associative memory impairments of amnesics with severe recollection deficits. This has been verified in studies of associative recognition (Giovanello et al., 2006; Quamme et al., 2007) and source recognition (Diana et al., 2008). For example, in one study (Quamme et al., 2007), patients studied word pairs under conditions that either promoted unitization (e.g., encoding word pairs as novel compound words) or did not promote unitization (e.g., encoding word pairs as separate words in a sentence). Patients who had selective deficits in recollection showed pronounced associative recognition deficits when the encoding conditions did not promote unitization, but they showed relatively preserved associative memory when encoding conditions promoted unitization. In contrast, patients with deficits in recollection and familiarity showed impairments in associative memory regardless of the encoding conditions.

Further evidence comes from fMRI studies that manipulated the degree to which pairs of items or item–source associations were unitized. As described in more detail later, hippocampal activity during encoding is typically predictive of accurate source and associative recognition, whereas activity in the surrounding pererhinal cortex (PRc) is predictive of familiarity-based item recognition (e.g., Ranganath et al., 2004). However, in a recent fMRI study (Haskins et al., 2008), word pairs encoded in a unitized fashion were associated with increased activity in the PRc, and activation in this region during encoding predicted subsequent familiarity-based associative recognition responses (for similar results at retrieval, see Diana et al., 2010).

Two important points about unitization should be made. First, unitization is a continuous variable rather than a dichotomous one, and so we refer to it as a ‘levels of unitization’ manipulation. That is, conditions can be made more or less likely to promote unitization, but it may be impossible to know in any absolute sense whether an individual has treated a stimulus as a single item or as a set of associated features. Importantly, however, as described above, we can manipulate conditions and materials such that there is little ambiguity as to whether unitization is more or less likely to occur in one condition than another. Second, it is likely that factors other than unitization may influence the extent to which familiarity contributes to associative recognition. For example,Mayes et al. (2007) have argued that individuals are able to use familiarity to link aspects of an event that come from the same processing domain (e.g., a face–face pair), whereas across-domain associations (e.g., a face–name pair) require recollection. This ‘domain dichotomy’ view is similar to the unitization hypothesis in the sense that within-domain pairs may be easier to treat as single units than across-domain pairs. However, we see no reason to believe that one could not unitize across-domain pairs. Further research into this question will be important in determining if the ability to unitize stimuli is moderated by the domain of the materials being associated.

THE HIPPOCAMPUS IS CRITICAL FOR RECOLLECTION, BUT NOT FAMILIARITY

We have argued that recollection and familiarity are separate processes that make independent contributions to recognition memory, and that they are supported by partially independent brain regions. More specifically, the hippocampus is assumed to play a critical role in supporting the encoding and retrieval of the arbitrary associations that support recollection, whereas familiarity is supported by other brain regions involved in identifying the stimulus (Yonelinas, 2001). Evidence from a broad range of paradigms has provided support for these claims (for earlier reviews, see Aggleton and Brown, 1999, 2001; Yonelinas, 2002; Eichenbaum et al., 2007). In this section, we focus on results from human lesion and volumetric studies, but briefly relate these to recent fMRI and animal results (see the Ranganath (2010) and Brown (2010) papers in the current volume for thorough discussions of the fMRI and animal literatures, respectively).

Task Dissociation Methods

Early evidence that the hippocampus was particularly important for recollection came from task dissociation methods in which one contrasts performance on two memory tests that are expected to rely differentially on recollection and familiarity. For example, free recall is expected to rely primarily on recollection, whereas item recognition is expected to rely on both recollection and familiarity (Mandler, 1980). Thus, a selective recollection impairment should produce a slightly greater deficit in recall than in recognition. In studies of patients with relatively selective hippocampal damage, recall is often found to be disrupted to a greater extent than recognition (Vargha-Khadem et al., 1997; Holdstock et al., 2000; Baddeley et al., 2001; Mayes et al., 2001; Bastin et al., 2004; Holdstock et al., 2008; Adlam et al., 2009; but see Reed and Squire, 1997; Manns and Squire, 1999; Kopelman et al., 2007). Similarly, because source memory and associative recognition are expected to rely heavily on recollection, amnesics should be slightly more impaired on these tests than on item recognition. Consistent with these expectations, hippocampal patients often exhibit more pronounced deficits on associative and source memory tests than on item recognition tests (e.g., Gold et al., 2006a, experiment 1; Holdstock et al., 2005, Mayes et al., 2002; Turriziani et al., 2004; but see Gold et al., 2006a, experiment 2; Stark et al., 2002; Gold et al., 2006b). However, since these tests are not process pure, the differences in task performance may not be large enough for differential impairment to be observed. It is therefore encouraging to find such differences since they may be difficult to detect, but more precise methods of examining recollection and familiarity are more informative.

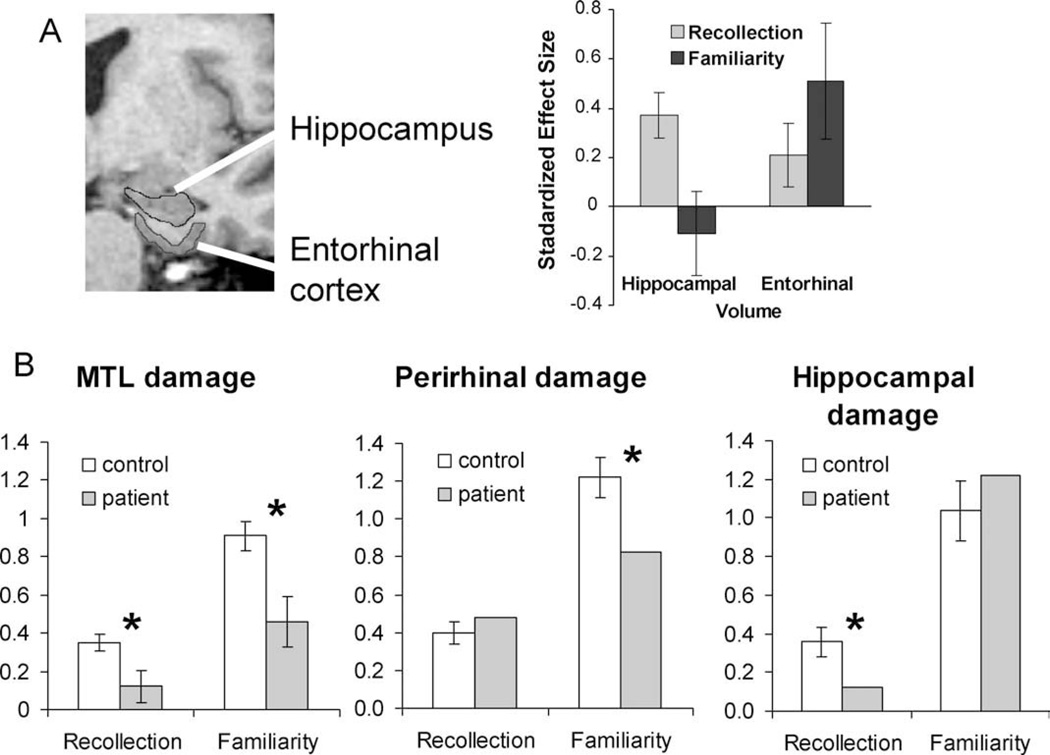

Process Estimation Methods

A more powerful way of assessing recollection and familiarity is to use methods designed to estimate the contribution of the processes underlying overall performance. For example, Yonelinas et al. (2002; also see Quamme et al., 2004) obtained recall and recognition data from a large group of mild hypoxic patients expected to have selective hippocampal damage, and used structural equation modeling to examine the effects of hypoxia on the latent variables underlying recall and recognition performance. The results indicated that the severity of the hypoxic event negatively predicted recollection but did not correlate with familiarity. In two further experiments that examined recollection and familiarity using remember/know and ROC procedures, patients with hypoxia were again found to exhibit selective deficits in recollection, whereas patients with damage to the hippocampus and the surrounding MTL had deficits in both recollection and familiarity. Together, these results suggest that the hippocampus is critical for recollection and that the surrounding MTL is critical for familiarity.

Volumetric data linking hypoxia to hippocampal atrophy were not available in the previous study, but this was directly addressed in a similar study of healthy aging (Yonelinas et al., 2007), which showed that reductions in hippocampal volume were associated with declines in recollection, but not familiarity. Conversely, differences in cortical volume within the entorhinal cortex (EC) were related to familiarity, but not recollection (see Fig. 6A). A similar double dissociation was recently reported in a study using the source memory procedure to estimate recollection and familiarity (Wolk et al., 2010). Recollection was most strongly related to hippocampal volume, whereas familiarity was most directly related to the surrounding entorhinal and perirhinal volume. Further support for these results comes from studies of a patient with a lesion to the perirhinal cortex that did not impact the hippocampus. This patient has a selective deficit in familiarity, but intact recollection, as measured by ROC and remember/know methods (see Fig. 6B; Bowles et al., 2007). Such double dissociations are strong evidence that recollection and familiarity depend on distinct neural structures in the medial temporal lobe, and argue against earlier proposals that medial temporal lobe damage simply leads to weaker memories.

FIGURE 6.

The involvement of different MTL regions in recognition memory. (A) In healthy aging, hippocampal volume is related to standardized measures of recollection, whereas entorhinal volume is related to familiarity (from Yonelinas et al., 2007). (B) Estimates of recollection and familiarity derived from ROCs indicate that extensive MTL damage disrupts both recollection and familiarity (Yonelinas et al., 1998), whereas perirhinal damage selectively disrupts familiarity (Bowles et al., 2008), and hippocampal damage selectively disrupts recollection (Aggleton et al., 2005).

As illustrated in Figure 6B, additional studies using process estimation methods such as remember/know, ROC, and process dissociation procedures have now verified that selective hippocampal damage disrupts recollection but not familiarity (e.g., Bastin et al., 2004; Aggleton et al., 2005; Bird et al., 2008; Brandt et al., 2008; Peters et al., 2008; Turriziani et al., 2008b; Jager et al., 2009), whereas damage that includes both the hippocampus and the surrounding MTL leads to deficits in both recollection and familiarity (e.g., Verfaellie and Treadwell, 1993; Knowlton and Squire, 1995; Blaxton and Theodore, 1997; Schacter et al., 1996, Schacter et al., 1997; Yonelinas et al., 1997).

Note that some studies of patients presumed to have focal hippocampal damage have shown deficits in both recollection and familiarity. For example,Cipolotti et al. (2006) reported a hypoxic patient who exhibited deficits in recollection and familiarity. However, in addition to hippocampal atrophy, the patient exhibited atrophy in the surrounding MTL, which could explain the familiarity deficit. Similarly, impairments in familiarity and recollection have also been reported in a group of severely impaired amnesic patients with diverse etiologies including heroin overdose and carbon monoxide poisoning (e.g., Manns et al., 2003, Stark and Squire, 2003; Wais et al., 2006; Gold et al., 2006b, Kirwan et al., 2010). In the absence of histological evidence, however, it is possible that the familiarity deficits observed in this group were due to damage outside the hippocampus (Yonelinas et al., 2004).

Additional evidence linking the hippocampus to recollection comes from studies examining the effects of damage to the fornix, a major fiber tract connecting the hippocampus to the thalamus. Several studies examining patients with fornix lesions have indicated that these patients exhibit selective deficits in recollection (e.g., Carlesimo et al., 2007; Vann et al., 2009). In fact, fornix damage appears to lead to selective recollection impairments in both anterograde and retrograde amnesia (Gilboa et al., 2006). Moreover, converging neuroimaging evidence has recently demonstrated that fornix white matter microstructural integrity, as measured with diffusion weighted imaging, is correlated with recollection, not familiarity (Rudebeck et al., 2009).

The human lesion results show that the hippocampus plays a particularly important role in recollection. Moreover, when damage includes the hippocampus and the surrounding MTL cortex, the deficits invariably involve both recollection and familiarity. Finally, damage or volume reduction in the surrounding MTL cortex that spares the hippocampus can be related to selective reductions in familiarity.

Animal Studies

The results from the human studies of amnesia have been supported by convergent results from studies of rats. Although procedures like free recall and remember/know tests do not easily lend themselves to animal studies, the ROC procedures can be readily adapted (for a review, see Eichenbaum et al., 2010). ROCs have been examined in odor recognition studies in rats, and have indicated that selective hippocampal lesions impair recollection but spare familiarity-based recognition (Fortin et al., 2004). Similarly, in tests of associative recognition, hippocampal lesions selectively eliminate the contribution of recollection and lead to ROCs indicative of familiarity-based memory (Sauvage et al., 2008). These results are important in directly linking the animal and human literatures, and they help address potential concerns that deficits in human amnesic patients may be due to hidden damage. An important question for future studies is whether selective damage to the regions surrounding the hippocampus leads to selective familiarity-based deficits, as has been suggested in the human studies.

Related fMRI Studies

The advent of fMRI has provided a powerful methodology for investigating the neural correlates of recollection and familiarity in healthy adults. A large number of such studies have now been published and they provide converging evidence that the hippocampus is involved primarily in recollection (for reviews, see Eichenbaum et al., 2007; Skinner and Fernandes, 2007; Wais, 2008). Although there are individual neuroimaging experiments that do not fit this pattern, there is general consensus that the hippocampus is critical for recollection and that it plays little or no role in familiarity. For example, in a review of remember/know, source memory and ROC studies that included recollection and familiarity contrasts, 16 of 19 studies showed that the hippocampus was involved in recollection, whereas only two showed hippocampal involvement in familiarity (Eichenbaum et al., 2007). In contrast, 13 of 15 studies showed that the PRc was associated with familiarity, whereas only four showed relationships to recollection. The convergence across these different paradigms and experiments is important because it rules against alternative interpretations that can arise when considering only one experiment or one experimental paradigm. Nonetheless, the fMRI literature has been somewhat less clear about the role of other brain regions, and we return to this issue below.

The results from the human neuropsychological studies of memory are in good agreement with those from animal lesion and human neuroimaging studies, and together they leave no doubt that the hippocampus plays a distinct mnemonic role from that supported by the surrounding MTL regions. Results from across these methods converge in showing that the hippocampus plays an essential role in recollection and that it plays little or no role in familiarity. Although the results from any single methodological approach are always open to alternative interpretations, when examined together the convergence across these literatures presents a very clear picture, particularly with respect to the role of the hippocampus.

EMERGING ISSUES

Thus far, we have considered three of the most controversial assumptions of the DPSD model and have agued that the existing literature provides strong support for those assumptions. However, it is also evident that there are some important boundary conditions to when those assumptions hold, and that there are a number of unanswered questions about the nature of recollection and familiarity that need to be more fully addressed. Nevertheless, there seems to be little question that the model has been useful thus far in helping to integrate diverse literatures, in generating novel predictions, and in leading to new discoveries.

The above-mentioned assessment of the model has focused primarily on recognition memory tasks and the role played by the hippocampus. However, there is growing evidence for the involvement of other brain regions in recollection and familiarity, and evidence that the same MTL regions that have been implicated in recognition memory also play critical roles in other cognitive processes. In this final section, we briefly discuss three questions that emerge when considering the model in light of these findings: (i) How does the prefrontal cortex (PFC) contribute to recollection and familiarity? (ii) What are the functional contributions of the perirhinal cortex (PRc) and parahippocampal cortex (PHc) to recognition memory? and (iii) What functions other than long-term recognition memory are supported by the MTL?

Recollection, Familiarity, and the PFC

A number of studies have suggested that the PFC might be particularly important for recollection (Janowsky et al., 1989; Wheeler et al., 1997; Davidson and Glisky, 2002; Wheeler and Stuss, 2003). This idea is supported by evidence that PFC lesions disrupt recall more than recognition (for reviews, see Wheeler et al., 1995, 1997; but see Kopelman and Stanhope, 1998; Kopelman et al., 2007), and damage to the PFC is associated with more pronounced deficits in tests of source memory than tests of item recognition (e.g., Milner, 1971; Milner et al., 1985; Janowsky et al., 1989; Shimamura et al., 1990; Johnson et al., 1997; but see Swick et al., 2006). However, studies that have used methods to directly examine recollection and familiarity have suggested that the role of the PFC may be more complex than this initial view suggests. For example, studies using a variety of process estimation methods, such as the remember/know, ROC, and source recognition paradigms have indicated that PFC damage can impair both recollection and familiarity (Duarte et al., 2005; Farovik et al., 2008; MacPherson et al., 2008; Kishiyama et al., 2009). In agreement with the patient lesion evidence, temporary PFC lesions induced by transcranial magnetic stimulation lead to deficits in both recollection and familiarity- based recognition responses (Turriziani et al., 2008a, 2010). Interestingly, however, these studies have suggested that whereas stimulation during encoding disrupts both recollection and familiarity, similar effects are not seen when stimulating at time of retrieval, suggesting that the PFCs contribution to item recognition memory may be restricted primarily to the time of encoding. However, the neuroimaging literature suggests that the PFC is involved in both recollection and familiarity during encoding and retrieval (Henson et al., 2000; Dobbins et al., 2004; Yonelinas et al., 2005; Blumenfeld and Ranganath, 2007). Determining the precise role or roles that the PFC plays in recollection and familiarity will require additional studies, but the existing literature provides little or no support for the earlier claims that the PFC is selectively important for recollection.

Contributions of the PRc and PHc to Recognition Memory

We have argued that the hippocampus is critical for recollection, but it is less clear how other MTL regions, such as the PRc and PHc, support recollection and/or familiarity. However, several general findings have emerged over the past few years that provide some important insights into the contribution of these different regions to recognition. First, as previously described, the PRc is generally related to familiarity-based item recognition responses (for reviews, see Eichenbaum et al., 2007), and it can play a role in associative and source memory under conditions that promote unitization of item–item or item–source information (Staresina and Davachi, 2006; Haskins et al., 2008; Diana et al., 2010). Second, the PHc is often associated with recollection, even in cases in which there are little or no spatial retrieval demands (e.g., Ranganath et al., 2003; Dolcos et al., 2005; Fenker et al., 2005; Yonelinas et al., 2005). The latter finding is interesting in light of prior work suggesting that the PRc and PHc seem to be particularly important for processing of object and spatial information, respectively (Bar and Aminoff, 2003; Pihlajamaki et al., 2004; Buffalo et al., 2006; Litman et al., 2009).

In collaboration with Howard Eichenbaum, Charan Ranganath, and Rachel Diana, we have taken preliminary steps toward integrating these results with the DPSD model (Eichenbaum et al., 2007; Diana et al., 2007). In the ‘binding of item and context’ (BIC) model (Diana et al., 2007; Ranganath, this issue), the PRc, PHc, and hippocampus work together to support recollection and familiarity. The PRc is proposed to be important in encoding and retrieving items (e.g., objects, words, and ideas), whereas the PHc is responsible for representing contextual information (e.g., spatial, semantic, and temporal context). The hippocampus supports memory for episodes by binding the item and context information together. Thus, the BIC model is consistent with the DPSD model and the existing data linking recollection to the hippocampus. In addition, because recollection is expected to involve the retrieval of contextual information, the BIC model predicts that the PHc should also be involved in recollection. Moreover, to the extent that the PRc supports item memory, it should be capable of supporting familiarity in the absence of recollection. Finally, the PRc should be involved in associative and source recognition under conditions in which associated items, or items and sources, are encoded as single units (i.e., they are unitized).

In general, the BIC model can account for findings suggesting that different MTL regions are sensitive to different types of materials (e.g., object vs. spatial information in the PRc and PHc, respectively) and with the notion that there is functional specialization in the MTL for different recognition processes (i.e., recollection and familiarity). Although this model provides a way of integrating existing data on the functional roles of various MTL regions, the important question that we are now only beginning to address is whether the model is useful in generating novel predictions, and whether the experimental findings will support these predictions (see Diana et al., 2007).

The Role of the MTL in Other Cognitive Functions

To the extent that familiarity arises as a byproduct of item identification, the brain regions supporting familiarity should be involved in cognitive tasks other than long-term recognition memory (Mandler, 1980; Jacoby, 1991). For example, if the PRc supports the processing of high-level item representations, this region may also play a role in the perception and identification of incoming stimuli, and consequently may also be involved in some forms of implicit memory for those stimuli. In fact, there is now evidence that the PRc is important in complex visual discrimination tasks that make little explicit demands on long-term memory (Bussey et al., 2002; Lee et al., 2005a,b, 2007; for a review, see Bussey and Saksida, 2007). Moreover, the PRc has been shown to be sensitive to stimulus repetition in semantic judgment tasks (O’Kane et al., 2005; Voss et al., 2009), and it appears to be necessary for conceptual implicit memory (Wang et al., in press).

Similarly, given the proposed role of the hippocampus in supporting the binding of item and context information, this region may play a role in the perception and short-term maintenance of complex spatial and relational information. A number of recent studies suggest that hippocampal damage is associated with deficits in perceptual or short-term memory tasks involving complex spatial scenes or relational stimuli (Lee et al., 2005a,b; Hannula et al., 2006; Olson et al., 2006; Piekema et al., 2006; for reviews, see Bussey and Saksida, 2007; Graham et al., 2010). If the hippocampus is involved in the initial construction of a given spatial representation, then hippocampal damage may lead both recollection- and familiarity- based recognition memory to be impaired for that spatial representation. Although this issue has yet to be systematically examined, evidence from several single case studies demonstrates that right hemisphere hippocampal damage is sufficient to impair both recollection and familiarity for scenes (Carlesimo et al., 2001, Cipolotti et al., 2006; Bird et al., 2007, 2008).

In addition to perception and short-term memory, the MTL also appears to play a role in the processing and detection of novelty (for reviews, see Ranganath and Rainer, 2003; Nyberg, 2005; Kumaran and Maguire, 2007, 2009). It has been suggested that the PRc supports item-based novelty detection, which is consistent with its importance in discriminating between familiar and new items. In contrast, the hippocampus is thought to play a role in signaling configural or relational novelty, in line with its importance in binding together item and context information. The relationship between novelty detection and recognition memory processes is not yet fully understood, but one possibility is that the efficacy of encoding is directly related to the novelty of the study item (Tulving et al., 1994; Tulving and Kroll, 1995). If this ‘novelty encoding hypothesis’ is correct, the hippocampus may lead to enhanced encoding of novel items and configurations, which could augment subsequent recollection- and familiarity-based recognition. Behavioral evidence indicates that both recollection and familiarity are increased when items are processed or presented in a novel manner at study (Dobbins et al., 1998; Kishiyama and Yonelinas, 2003). Moreover, patients with lesions to the hippocampus do not benefit from stimulus novelty, as indexed using the von Restorff paradigm, in either recollection or familiarity (Kishiyama et al., 2004). Thus, this appears to be a case where hippocampal damage leads to deficits in both recollection and familiarity-based responses. Note that this familiarity deficit does not indicate that the hippocampus is directly supporting familiarity-based retrieval; instead, the hippocampus may have a general, indirect effect on subsequent memory by signaling novelty, thus leading to enhanced encoding in other MTL regions (e.g., the PRc).

CONCLUSIONS

The goal of this article was to critically examine current assumptions about recollection and familiarity and highlight important advancements and new directions. The existing literature indicates that the three most controversial assumptions of the DPSD model are well supported. First, recollection and familiarity are well characterized as threshold and signal detection processes, respectively. Second, although source and associative recognition tasks often rely heavily on recollection, familiarity can support memory judgments for associations, particularly under conditions when the unitization of arbitrary associations is promoted. Finally, the hippocampus is critical for recollection and plays little or no role in familiarity-based recognition.

Nonetheless, it has become apparent that there are important boundary conditions to when these assumptions will hold. For example, the threshold nature of recollection can break down when there is high feature overlap among studied items. It is also clear that a more complete model of recognition memory will need to account for the distinct contributions of brain regions other than the hippocampus, such as the PRc, the PHc, and the PFC. Such a comprehensive model should also provide a way of integrating findings linking perception, implicit memory and novelty detection to the medial temporal lobe. We believe that the ongoing work with the BIC model and the CLS model represents important steps in this direction.

If William James were to see what we have learned about recollection and familiarity over the past 100 years, what would he think? Our guess is that he would be happy to see that the questions he concerned himself with have led to such a productive field of scientific study, and he may well take some pride in realizing that the questions he contemplated are sufficiently deep that they will keep us busy for a long time to come.

Acknowledgments

Grant sponsor: National Institute of Mental Health; Grant number: MH59325.

REFERENCES

- Adlam ALR, Malloy M, Mishkin M, Vargha-Khadem F. Dissociation between recognition and recall in developmental amnesia. Neuropsychologia. 2009;47:2207–2210. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2009.01.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aggleton JP, Brown MW. Episodic memory, amnesia, and the hippocampal anterior thalamic axis. Behav Brain Sci. 1999;22:425–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aggleton JP, Brown MW. Recognition memory: What are the roles of the perirhinal cortex and hippocampus? Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:51–61. doi: 10.1038/35049064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aggleton JP, Brown MW. Interleaving brain systems for episodic and recognition memory. Trends Cogn Sci. 2006;10:455–463. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aggleton JP, Vann SD, Denby C, Dix S, Mayes AR, Roberts N, Yonelinas AP. Sparing of the familiarity component of recogntion memory in a patient with hippocampal pathology. Neuropsychologia. 2005;43:1810–1823. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2005.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson RC, Juola JF. Search and decision processes in recognition memory. In: Krantz DH, Atkinson RC, Luce RD, Suppes P, editors. Contemporary Developments in Mathematical Psychology, Vol. 1: Learning, Memory, Thinking. San Francisco: Freeman; 1974. pp. 239–289. [Google Scholar]

- Baddeley A, Vargha-Khadem F, Mishkin M. Preserved recognition in a case of developmental amnesia: Implications for the acquisition of semantic memory? J Cogn Neurol. 2001;13:357–369. doi: 10.1162/08989290151137403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar M, Aminoff E. Cortical analysis of visual context. Neuron. 2003;38:347–358. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00167-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastin C, Van der Linden M, Charnallet A, Denby C, Montaldi D, Roberts N, Mayes AR. Dissociation between recall and recognition memory performance in an amnesic patient with hippo- campal damage following carbon monoxide poisoning. Neurocase. 2004;10:330–344. doi: 10.1080/13554790490507650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird CM, Shallice T, Cipolotti L. Fractionation of memory in medial temporal lobe amnesia. Neuropsychologia. 2007;45:1160–1171. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2006.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird CM, Varga-Khadem F, Burgess N. Impaired memory for scenes but not faces in developmental hippocampal amnesia: A case study. Neuropsychologia. 2008;46:1050–1059. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2007.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaxton TA, Theodore WH. The role of the temporal lobes in recognizing visuospatial materials: Remembering versus knowing. Brain Cogn. 1997;35:5–25. doi: 10.1006/brcg.1997.0902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumenfeld RS, Ranganath C. Prefrontal cortex and long-term memory encoding: An integrative review of findings from neuropsychology and neuroimaging. Neuroscientist. 2007;13:280–291. doi: 10.1177/1073858407299290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowles B, Crupi C, Mirsattari SM, Pigott S, Parrent AG, Pruessner JC, Yonelinas AP, Kohler S. Impaired familiarity with preserved recollection after anterior temporal-lobe resection that spares hippocampus. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:16382–16387. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705273104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt KR, Gardiner JM, Vargha-Khadem F, Baddeley AD, Mishkin M. Impairment of recollection but not familiarity in a case of developmental amnesia. Neurocase. 2009;15:60–65. doi: 10.1080/13554790802613025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bricker PD, Chapanis A. Do incorrectly perceived tachistoscopic stimuli convey some information? Psychol Rev. 1953;60:181–188. doi: 10.1037/h0054901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buffalo EA, Bellgowan PS, Martin A. Distinct roles for medial temporal lobe structures in memory for objects and their locations. Learn Mem. 2006;13:638–643. doi: 10.1101/lm.251906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bussey TJ, Saksida LM. Memory, perception, and the ventral visual-perirhinal-hippocampal stream: Thinking outside of the boxes. Hippocampus. 2007;17:898–908. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bussey TJ, Saksida LM, Murray EA. Perirhinal cortex resolves feature ambiguity in complex visual discriminations. Eur J Neurosci. 2002;15:365–374. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01851.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlesimo GA, Fadda L, Turriziani P, Tomaiuolo F, Caltagirone C. Selective sparing of face learning in a global amnesic patient. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2001;71:340–346. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.71.3.340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlesimo GA, Serrab L, Faddaa L, Cherubinic A, Bozzalic M, Caltagirone C. Bilateral damage to the mammillo-thalamic tract impairs recollection but not familiarity in the recognition process: A single case investigation. Neuropsychologia. 2007;45:2467–2479. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2007.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cipolotti L, Bird C, Good T, Macmanus D, Rudge P, Shalliace T. Recollection and familiarity in dense hippocampal amnesia: A case study. Neuropsychologia. 2006;44:489–506. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2005.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson PSR, Glisky EL. Neuropsychological correlates of recollection and familiarity in normal aging. Cogn Affect Behav Neurol. 2002;2:174–186. doi: 10.3758/cabn.2.2.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeCarlo LT. Signal detection theory with finite mixture distributions: Theoretical developments with applications to recognition memory. Psychol Rev. 2002;109:710–721. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.109.4.710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diana RA, Yonelinas AP, Ranganath C. Imaging recollection and familiarity in the medial temporal lobe: A three-component model. Trends Cogn Sci. 2007;11:379–386. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2007.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diana RA, Yonelinas AP, Ranganath C. The effects of unitization on familiarity-based source memory: Testing a behavioral prediction derived from neuroimaging data. J Exp Psychol Learn Mem Cogn. 2008;34:730–740. doi: 10.1037/0278-7393.34.4.730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diana RA, Yonelinas AP, Ranganath C. Medial temporal lobe activity during source retrieval reflects information type, not memory strength. J Cognitive Neurosci. 2010;22:1808–1818. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2009.21335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobbins IG, Kroll NEA, Yonelinas AP, Liu Q. Distinctiveness in recognition and free recall: The role of recollection in the rejection of the familiar. J Mem Lang. 1998;38:381–400. [Google Scholar]

- Dobbins IG, Simons JS, Schacter DL. fMRI evidence for separable and lateralized prefrontal memory monitoring processes. J Cogn Neurosci. 2004;16:908–920. doi: 10.1162/0898929041502751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodson CS, Johnson MK. Some problems with the process-dissociation approach to memory. J Exp Psychol Gen. 1996;125:181–194. doi: 10.1037//0096-3445.125.2.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]