Abstract

Introduction:

HIV-related stigma and discrimination and disrespect and abuse during childbirth are barriers to use of essential maternal and HIV health services. Greater understanding of the relationship between HIV status and disrespect and abuse during childbirth is required to design interventions to promote women's rights and to increase uptake of and retention in health services; however, few comparative studies of women living with HIV (WLWH) and HIV-negative women exist.

Methods:

Mixed methods included interviews with postpartum women (n = 2000), direct observation during childbirth (n = 208), structured questionnaires (n = 50), and in-depth interviews (n = 18) with health care providers. Bivariate and multivariate regressions analyzed associations between HIV status and disrespect and abuse, whereas questionnaires and in-depth interviews provided insight into how provider attitudes and workplace culture influence practice.

Results:

Of the WLWH and HIV-negative women, 12.2% and 15.0% reported experiencing disrespect and abuse during childbirth (P = 0.37), respectively. In adjusted analyses, no significant differences between WLWH and HIV-negative women's experiences of different types of disrespect and abuse were identified, with the exception of WLWH having greater odds of reporting non-consented care (P = 0.03). None of the WLWH reported violations of HIV confidentiality or attributed disrespect and abuse to their HIV status. Provider interviews indicated that training and supervision focused on prevention of vertical HIV transmission had contributed to changing the institutional culture and reducing HIV-related violations.

Conclusions:

In general, WLWH were not more likely to report disrespect and abuse during childbirth than HIV-negative women. However, the high overall prevalence of disrespect and abuse measured indicates a serious problem. Similar institutional priority as has been given to training and supervision to reduce HIV-related discrimination during childbirth should be focused on ensuring respectful maternity care for all women.

Key Words: HIV; pregnancy; disrespect and abuse; maternal health; stigma, discrimination; sub-Saharan Africa

INTRODUCTION

Evidence suggests that experiences or anticipation of disrespect and abuse in maternity care, including HIV-related stigma and discrimination, discourage women from seeking health services and can cause them to drop out of care.1–3 In the case of HIV-related stigma, anticipation of discrimination, internalized stigma, and having stigmatizing attitudes toward people living with HIV are associated with refusing HIV testing during antenatal care, not returning for posttest HIV counseling, not delivering in a facility, reduced adherence to antiretroviral treatment for prevention of vertical (mother-to-child) transmission of HIV, and not enrolling in HIV treatment services.3 In Tanzania, HIV-related stigma has been associated with nondisclosure of HIV status, women not accessing HIV care for their own health, and poor postnatal adherence to antiretrovirals.4,5 A recent study found that rural women in Tanzania, 60% of whom had their last birth at home, identified respectful attitudes from providers as the most important single factor that would reduce their preference for home delivery relative to facility-based delivery.6 In another study, approximately 40% of rural Tanzanian women who had their last birth at a facility reported traveling to more distant health care sites because of perceived measures of facility quality such as having the best providers, drug availability, recommendation by a relative/friend, a good previous experience, and high trust in health workers.7

Despite increasing research about and recognition of how disrespect and abuse during maternity care and HIV-related stigma and discrimination may negatively affect women's engagement with HIV and maternal health care services, few studies have explored relationships between HIV status and disrespect and abuse by comparing the experiences of women living with HIV (WLWH) and HIV-negative women during childbirth. Our analysis compares the reported and observed experiences of disrespect and abuse during labor and delivery of WLWH with HIV-negative women. Additionally, we explore relationships with health care providers' training, work experience, and conceptualizations of disrespect and abuse and equitable labor and delivery care as they pertain to WLWH.

METHODS

Study Setting and Data Collection

The data analyzed for this article are from a baseline study of disrespect and abuse conducted between April and October 2013 at a large urban regional referral hospital in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Although this hospital addresses clinical quality and interpersonal communication through its continuous quality improvement program, reducing disrespect and abuse were not specific objectives of quality improvement initiatives at the time of data collection for this study.8 The hospital serves urban and periurban women from the district with the lowest average socioeconomic status in Dar es Salaam. Although the hospital is designated within the health system to serve women with complications and those referred from primary healthcare facilities, in practice many women with low-risk pregnancies bypass the lower level facilities to deliver at this hospital. The labor and delivery ward is often overcrowded and understaffed; it is staffed by 2–3 health care providers per shift, averages 60 deliveries per day, and reports, on average, 4 maternal deaths, 125 pregnancy-related complications, and 18 neonatal deaths per month (Facility-based indicators 2013). The HIV prevalence among women attending antenatal and delivery care in Dar es Salaam is 7%.9 The conditions of overcrowding and understaffing of the maternity ward, and the relatively high HIV prevalence among women of reproductive age, are common in urban settings across sub-Saharan Africa10 meaning that this research may provide useful insights about the dynamics of disrespect and abuse related to HIV status in other similar settings.11

The study used a mixed-method design to assess disrespect and abuse during maternity care with the objective of designing interventions to reduce incidence. Adopting a pragmatic approach, we selected the research methods that seemed best suited to assessing prevalence and potential drivers of disrespect and abuse and to identifying the attitudes, training needs, and working conditions of health care providers that would be amenable to interventions.12 Women's experiences of disrespect and abuse were captured through interviews with postpartum women 3–6 hours postdelivery (n = 2000), client–provider interactions during childbirth were assessed by direct observation (n = 208), and health care provider attitudes, training, working conditions, and self-report of practice were assessed through structured questionnaires (n = 50) and in-depth interviews (n = 18). This mix of methods and our analysis aims to describe disrespect and abuse from different standpoints and to reconcile dualistic objectivist and subjectivist epistemologies through the pragmatic position that “knowledge is at the very same time constructed and real.”13 We implemented a convergent parallel mixed-method design that collected both quantitative and qualitative data before beginning the analysis, although the in-depth interviews were completed after the surveys and direct observation.12 The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Tanzanian National Institute of Medical Research. All research participants provided written or verbal informed consent.

Measures

During the postpartum interviews, women were asked about their experiences with the care provided at the hospital, including overall assessments of satisfaction and quality and more specifically about experienced disrespect and abuse, including physical abuse, nonconsented care, nonconfidential care, lack of privacy, nondignified care, abandonment during or after labor and delivery, and detention in facilities. Additionally, basic demographic and household information was collected. Nurse midwives observed client–provider interactions during the labor and delivery process to identify instances of disrespect and abuse.

Structured questionnaires asked health care providers about their training related to the clinical management of people living with HIV and prevention of vertical HIV transmission, the frequency with which they provide labor and delivery services to WLWH, and their comfort level with providing such services. In-depth interviews explored health care providers' perceptions and definitions of disrespect and abuse and any patient, provider, or facility-related factors that lead to such treatment occurring, including women's HIV status.

Data Analysis

In line with the convergent parallel mixed-method design, the qualitative and quantitative analyses were conducted independently and the results were mixed during the interpretation of the data.12 The analysis triangulates and examines convergence and divergence in results from the different methods to provide insight into how HIV status affects reported and observed disrespect and abuse during childbirth and to identify how provider perspectives and institutional culture regarding HIV status were related to experiences and practices of disrespect and abuse.

Quantitative Analysis

Categorical variables are presented in the tables as number (%) and continuous variables are presented as mean and standard deviation (SD). Eight primary outcome variables (any type of disrespect and abuse, physical abuse, nonconsented care, nondignified care, nonconfidential care, lack of privacy, abandonment and detention in facilities) were dichotomized and modeled using log binomial regression analysis. A separate binomial regression model was run for each of the 8 primary study outcomes to assess any correlation with the independent variables. The multivariate analysis controlled for age, marital status, employment status, parity, and number of antenatal care visits for the index pregnancy. A P value ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant. The analysis was performed using SAS (version 9.3; SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

Qualitative Analysis

In-depth interviews were translated into English. Qualitative analysis was conducted simultaneously with data collection to allow for modification of the interview guide to explore emerging issues, and analytic codes were defined through an inductive process based on the narratives of research participants rather than assigned a priori. To promote critical reflexivity and rigor, a team in Tanzania and a team in the United States independently developed codebooks, which were then compared to reach consensus on definitions. Qualitative data were coded and managed using the NVivo software package.

RESULTS

HIV Status and Sociodemographic Characteristics

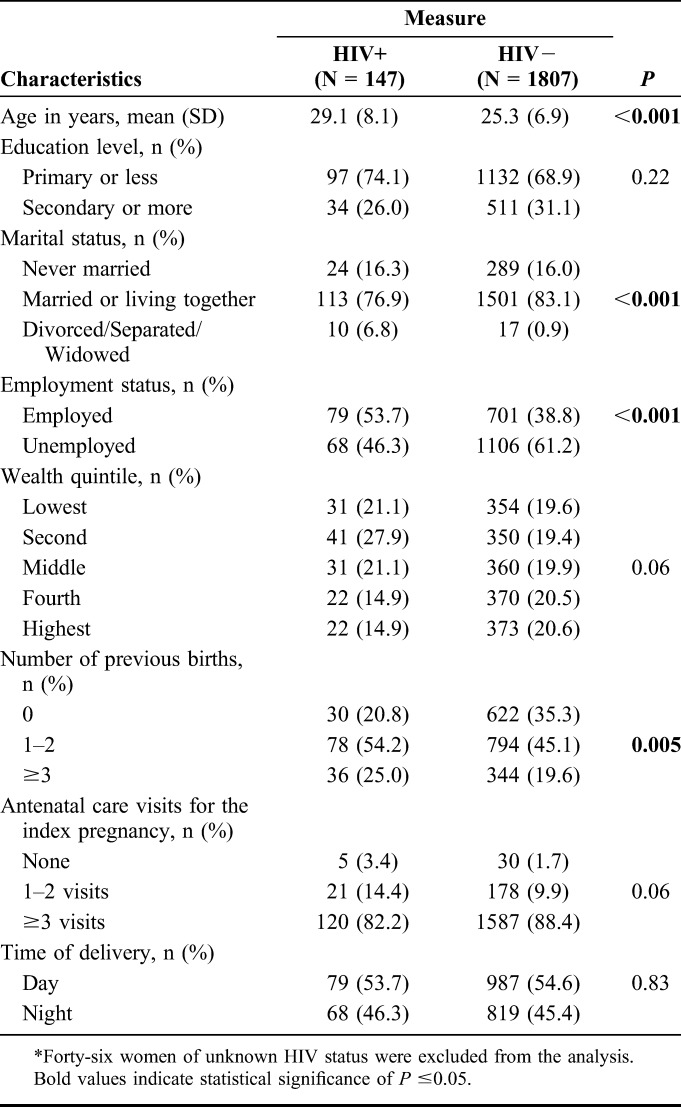

Of the women who participated in the postpartum interview, 147 (7.4%) were known to be living with HIV, 1807 (90.4%) were HIV negative, and 46 (2.3%) were of unknown HIV status. Table 1 presents the sociodemographic characteristics of women stratified by their HIV status. WLWH were slightly older [29.1 years (SD = 8.1) vs. 25.3 years (SD = 6.9); P < 0.001], higher parity (P = 0.005), less likely to be married or cohabitating (76.9% vs. 83.1%; P < 0.001), and more likely to be employed (53.7% vs. 38.8%; P < 0.001).

TABLE 1.

Sociodemographic and Delivery Characteristics of Study Participants (N = 1954)*

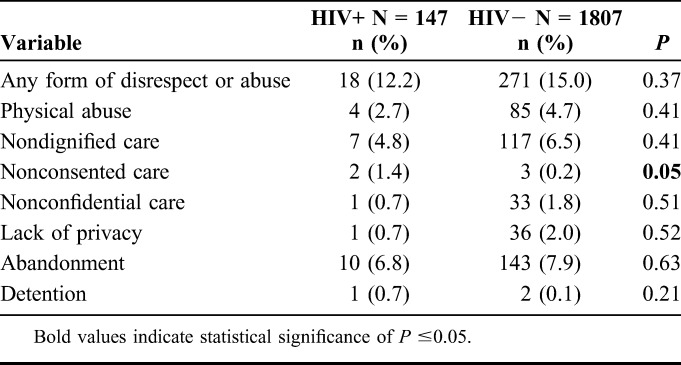

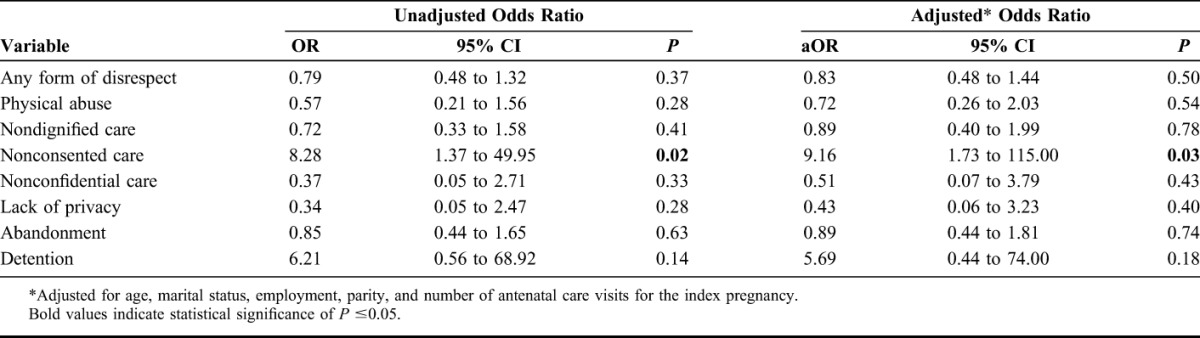

Overall, WLWH were no more or less likely to report any type of disrespect and abuse during labor and delivery (12.2%) than HIV-negative women (15.0%) (P = 0.37) (Table 2). WLWH reported lower prevalence of each category of disrespect and abuse than HIV-negative women with the exception of detention and nonconsented care (Table 2). After adjusting for age, marital status, employment status, parity, and number of antenatal care visits for the index pregnancy, WLWH were more likely to report nonconsented care than HIV-negative women (Adjusted Odds Ratio 9.16, 95% CI 1.73-115.00, P = 0.03). No other statistically significant correlations between living with HIV and reporting disrespect and abuse during maternity care were identified in the multivariate model (Table 3). Importantly, none of the 147 WLWH who completed the postpartum survey reported that their HIV confidentiality had been violated or attributed the disrespect and abuse they experienced during labor and delivery to their HIV status.

TABLE 2.

Comparison of Disrespect and Abuse Reported by WLWH and HIV-Negative Women During Childbirth

TABLE 3.

Bivariate and Multivariate Analysis of the Association Between Living with HIV and Reporting Disrespect and Abuse During Childbirth

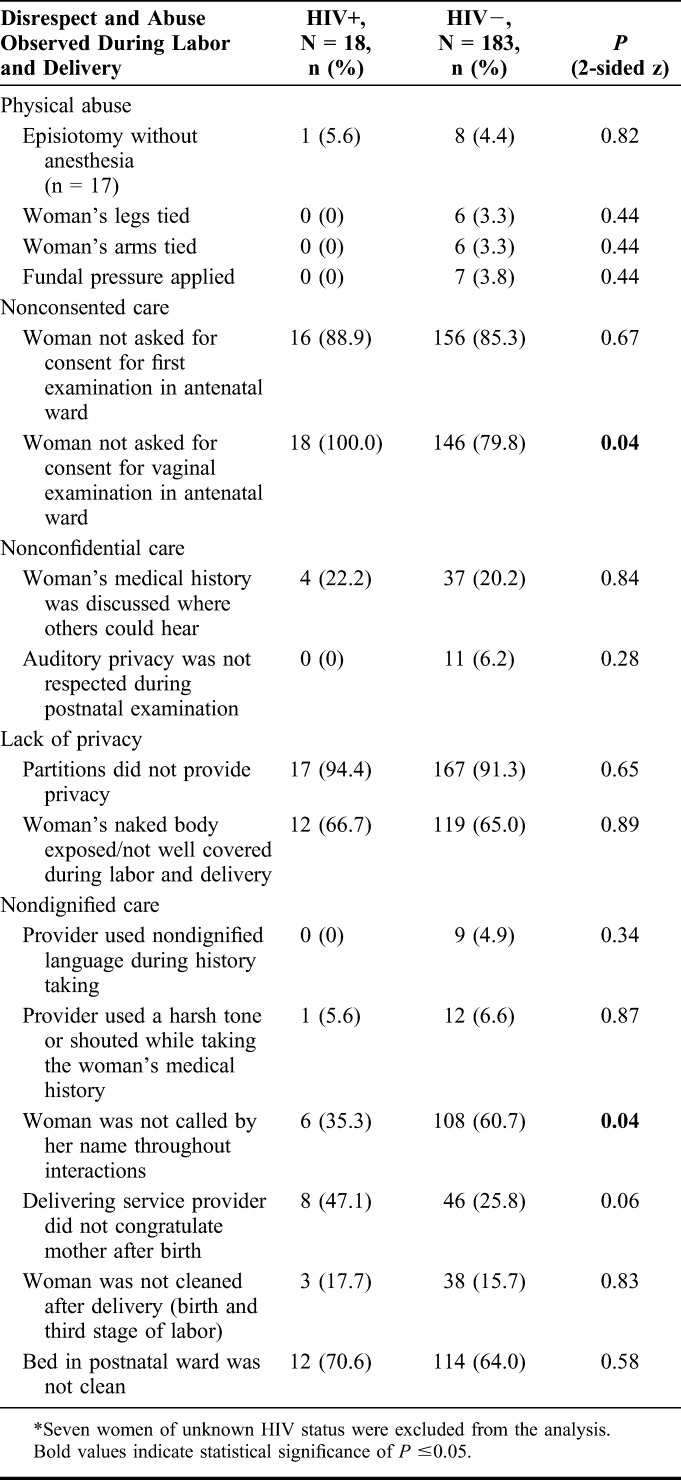

Direct observation of client–provider interactions during labor and delivery told a similar story to the interviews completed with postpartum women. Nurse midwives observed 18 WLWH and 183 HIV-negative women during childbirth. In Table 4, we present all the statistically significant observed differences and the observed measures of physical abuse, nonconsented care, nonconfidential care, lack of privacy, and selected measures of nondignified care which we hypothesized could be overt expressions of HIV-related stigma such as using nondignified language during history taking, not congratulating the woman after birth, or referring women with HIV to unclean beds in the postnatal ward. Only 2 statistically significant differences were observed. First, none of the WLWH were asked for consent before the vaginal examination in the antenatal ward, whereas 80% of HIV-negative women were not asked for consent (P = 0.04). Second, it was less common for health care providers not to call WLWH by their names during labor and delivery than other women (35.3% vs. 60.7% P = 0.04). Finally, although not significant at the 95% confidence interval, there is a trend toward health care workers being less likely to congratulate WLWH after giving birth than HIV-negative women (47.1% vs. 25.8%; P = 0.06).

TABLE 4.

Comparison of Directly Observed Disrespect and Abuse Toward WLWH and HIV-Negative Women During Childbirth*

Health Care Providers' Perspectives on HIV Status and Disrespect and Abuse During Childbirth

During in-depth interviews, health care providers working in the maternity ward demonstrated awareness of the right of WLWH to maintain the confidentiality of their HIV status during labor and delivery, spontaneously mentioning violations of HIV confidentiality to exemplify what they considered to be disrespectful or abusive care. A representative comment was made by one registered nurse who stated that “disrespect” is making “abusive statements to patients, or for instance, for the HIV-infected patients, mentioning her HIV positive status while she is with the other women, some of such patients feel bad—that is unfair” (INT007). Some respondents demonstrated sensitivity to the perceived stigma that women with HIV may feel, for instance saying “an HIV infected mother is not supposed to be abused; she will feel twenty times worse than the other mothers” (registered nurse, INT12). Providers said that HIV has been normalized to such an extent in the institution that WLWH frequently “come and tell you directly, they don't hide: ‘Nurse please help me I have this problem, please help me.’ And then after she tells you, you will take care of her with all the joy in you because she expressed her problem to you and you know how to help her prevent transmitting the infection to the baby and protect yourself” (medical attendant, INT18).

During in-depth interviews, health care providers uniformly denied that HIV status affected labor and delivery care. For example, a registered nurse said, “an HIV infected mother is cared for as usual, there are no stigmatization issues here; they get good care like any other patient” (registered nurse, INT6). Others noted that the only difference is “the medication we give the HIV infected [women], apart from that it is the same” (licensed practical nurse, INT14). Nurses described taking extra care with women with HIV to prevent occupational exposure and HIV transmission to the infant, but insisted that “the carefulness we are describing here is [done] in such a way that even the mother herself feels like it is being done for her benefit. Because nowadays anything you do to a patient you must explain to them first, so they know that the nurse is doing this to save my baby from getting the infection. It is done in a manner that makes the mother satisfied” (registered nurse INT15).

During interviews, health care providers stated that nondiscriminatory treatment had not always been the institutional status quo. They noted that in the past, health care providers had less information about preventing HIV transmission during labor and delivery and violated confidentiality, for example “indicating the patient to be HIV positive openly while others are listening” (registered nurse, INT11). However, the consensus expressed by those interviewed was that “such things nowadays they have vanished, nowadays they [WLWH] receive the usual care like others, they [providers] don't discriminate against them” (public health nurse, INT13). Providers attributed that the change in attitude to training and supervision focused on prevention of vertical HIV transmission and normalization of HIV through provision of labor and delivery services to many WLWH.

In general, confidential questionnaires completed by 50 health care providers reinforce the finding that training on HIV, including prevention of vertical HIV transmission, and providing services to women with HIV have normalized HIV in this setting. More than 38% of respondents reported receiving training in prevention of vertical HIV transmission during the past year and 36% received training in clinical management of HIV, with 46% of the providers interviewed receiving training in at least one of these issues. Additionally, 88% of providers reported having managed at least 1 WLWH during labor and delivery and 78% reported providing antiretroviral therapy to the mother and newborn to prevent vertical HIV transmission during the past 3 months. Of those who provided labor and delivery services to WLWH, 77% said they were comfortable doing so and 79% of those who provided antiretroviral therapy to prevent vertical HIV transmission said they were comfortable with this task. In a section of the confidential survey with a low response rate, a minority of responding health care providers (n = 5) said they avoided or had mixed feelings about doing vaginal examinations or repairing episiotomies for WLWH. These same 5 providers felt that WLWH should be isolated during childbirth or had mixed feelings about this practice. That such discriminatory practices were not admitted to or attributed to other health care providers during in-depth interviews further suggests that overt discrimination based on HIV status is perceived as unacceptable in the workplace culture of this facility.

Stockouts of standard commodities, such as cotton wool and gloves, and overcrowding were consistently described by providers as their greatest workplace challenges. However, during in-depth interviews, providers did not identify these institutional deficiencies—which make implementing universal infection prevention precautions difficult—as a motive for providing different care to WLWH. In practice, WLWH are not isolated during labor and delivery at this facility. One provider stated that when you have “4 mothers sharing that one bed, you can't say to the HIV infected mother ‘sleep on the floor because you have HIV’—that is not right, they all share the beds” (licensed practical nurse, INT14). In the situation of a WLWH sharing a bed with 3 others, the provider describes a general “warning” given to the occupants that, “there might be someone with HIV and you don't know so don't contaminate yourself with another persons' waters, also the blood should not touch you” as a deliberate strategy to promote infection control while preserving confidentiality (INT14). The comments made by providers about what constitutes disrespect and abuse, practices of caring for WLWH described during in-depth interviews, and this imperfect solution to overcrowding, all demonstrate provider awareness that differential treatment of WLWH is discrimination and that confidentiality of HIV status must be respected. Providers described making efforts to provide equitable care to WLWH in an institutional setting where guaranteeing universal precautions and confidentiality for any woman is a significant challenge.

DISCUSSION

Overall, WLWH who received labor and delivery services at a large urban hospital in Tanzania were no more or less likely to report any type of disrespect and abuse during labor and delivery than HIV-negative women (12.2% vs. 15.0%). However, WLWH were significantly more likely to report nonconsented care even after controlling for age, marital status, employment status, parity, and number of antenatal care visits for the index pregnancy. No other statistically significant differences in women reporting different types of disrespect and abuse were observed in the multivariate logistic regression model. During direct observation of labor and delivery, midwives recorded that WLWH were less likely to be asked for consent for vaginal examinations than HIV-negative women. It is important to note that this exploratory analysis was not specifically powered to detect differences in experiences of disrespect and abuse between WLWH and other women, and thus these results should be interpreted with caution. More research with larger samples is needed for further analysis of the relationship between HIV status and nonconsented care, and to continue to expand knowledge about associations between HIV status and experiences of disrespect and abuse during childbirth.

None of the 147 WLWH in the study reported a breach of the confidentiality of her HIV status or attributed the disrespect and abuse that she experienced to living with HIV. The absence of overt discrimination related to HIV status is likely because of the awareness health care providers demonstrated regarding the importance of maintaining confidentiality of HIV status, their affirmations that HIV status did not affect quality of care, and assertions that discriminatory acts, for example, making a woman sleep on the floor in an overcrowded labor ward because of her HIV status, were unacceptable. Although a small number of providers expressed lack of willingness or mixed feelings about providing obstetric services to WLWH in the confidential survey, in-depth interviews with providers signaled clearly that overt discrimination based on HIV status was no longer part of the institutional culture at the research site. Their descriptions of a change in institutional culture, from a time when violations of HIV confidentiality and lack of willingness to provide delivery services were common to the current situation, offer important lessons about how to discourage other forms of disrespect and abuse during maternity care. First, providers were sensitized about HIV and the rights of WLWH to confidentiality and equitable treatment, causing providers to identify HIV-related discrimination as “not right.” Second, providers received training about HIV and provided services to WLWH frequently—almost half had been trained on HIV or prevention of vertical HIV transmission within the past year, 88% had provided labor and delivery services to a WLWH in the past 3 months, and 79% of these individuals felt comfortable doing so. Third, and perhaps most importantly, providers received supervision that focused specifically on the quality of services to prevent vertical HIV transmission. Finally, addressing institutional deficiencies, like stockouts of basic commodities, may contribute to reducing provider fears related to occupational HIV exposure.

Similar to our results, a comparative study of perceived acceptability of obstetric services in South Africa found no significant differences in feeling respected by health workers between WLWH and other women.14 Nevertheless, reports of equitable treatment in obstetric services in Tanzania and South Africa do not necessarily extend to other domains of reproductive health in which HIV-related stigma has been identified as a driver of discrimination, such as in the case of coercive and forced sterilization.15–17 Lack of overt HIV-related discrimination during labor and delivery cannot be directly equated with acknowledgment of the rights of WLWH to choose the number and spacing of their children. Stigmatization of childbearing among WLWH by providers may be indicated by the trend identified in our research toward providers being less likely to congratulate WLWH after delivery than HIV-negative women. Our results suggest that research that allows for comparisons between WLWH and other women is valuable for disentangling disrespect and abuse driven by HIV stigma from other causes, and thereby permitting effective targeting of interventions.

Finally, it is important to highlight that many women reported and were observed to experience disrespect and abuse during childbirth. Abusive practices by health care providers and inadequate infrastructure18 that denies women dignity during childbirth, such as commodity stockouts, lack of adequate privacy partitions, and overcrowding that results in bed-sharing, must be transformed to guarantee respectful maternity care for all women.

CONCLUSIONS

That none of the WLWH reported violations of confidentiality or attributed the disrespect and abuse that they experienced during maternity care to their HIV status is a cause for optimism, as is the finding that providers were aware of the rights to confidentiality and nondiscrimination of WLWH. Furthermore, health care providers' descriptions of changes in institutional norms and practices that resulted in improved respect for the confidentiality of HIV status and nondiscrimination for WLWH indicate that disrespect and abuse are malleable phenomena. Our analysis suggests that creating awareness among health care providers that practices they may take for granted violate women's rights and implementing supervision and institutional quality improvement measures that take seriously the issue of disrespect and abuse during maternity care can contribute to improving women's childbirth experiences. The normalization of HIV and improvements in respect for the confidentiality of HIV status during the provision of services to prevent vertical HIV transmission documented in this study are an important achievement in the institution where the study was conducted. The political and institutional priority and resources that have been dedicated to ensuring that HIV-related discrimination is not a barrier to prevention of vertical HIV transmission should be expanded to ensure high-quality respectful maternity care for all women. Important future directions for research include conducting similar comparative studies with larger samples to explore associations between HIV-status and nonconsented care and to confirm the lack of association between HIV status and other forms of disrespect and abuse during childbirth; analysis of the effect of disrespect and abuse on willingness to return to the facility, postnatal care seeking, and intention to refer relatives or friends; and evaluation of interventions designed to reduce disrespect and abuse during childbirth.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the women and health care providers who participated in the study, as well as the Ministry of Health and Social Welfare in Tanzania, and the Population Council and Averting Maternal Death and Disability at Columbia University for providing validated research tools that were then adapted for the local context. They also acknowledge Angel Dilip (Ifakara Health Institute) and Nora Miller (HSPH) for contributions to coding of the qualitative data, as well as Dr. Adam Mrisho (MDH) for data collection coordination. The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official positions of the John and Katie Hansen Family Foundation, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research or the Pierre Elliott Trudeau Foundation.

Footnotes

Supported by the John and Katie Hansen Family Foundation (Fund 262902) and the Maternal Health Task Force which is supported through grant # 01065000621 from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

Postdoctoral fellowship of T.K. is supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the Pierre Elliott Trudeau Foundation. The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

D.S. and T.K. made equal contributions to the article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ratcliffe H. Creating an Evidence Base for the Promotion of Respectful Maternity Care. Boston, MA: Harvard School of Public Health; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bowser D, Hill K. Exploring evidence for disrespect and abuse in facility-based childbirth: report of a landscape analysis. USAID-TRAction Project, Harvard School of Public Health and University Research Co., September 20, 2010. Available at www.traction.org. Accessed July 3, 2014.

- 3.Turan JM, Nyblade L. HIV-related stigma as a barrier to achievement of global PMTCT and maternal health goals: a review of the evidence. AIDS Behav. 2013;17:2528–2539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Watson-Jones D, Balira R, Ross DA, et al. Missed opportunities: poor linkage to ongoing care for HIV-positive pregnant women in Mwanza, Tanzania. PLoS One. 2012;7:e40091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ngarina M, Popenoe R, Kilewo C, et al. Reasons for poor adherence to antiretroviral therapy postnatally in HIV-1 infected women treated for their own health: experiences from the Mitra Plus study in Tanzania. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kruk M, Paczkowski M, Mbaruku G, et al. Women's preferences for place of delivery in rural Tanzania: a population-based discrete choice experiment. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:1666–1672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kruk ME, Mbaruku G, McCord CW, et al. Bypassing primary care facilities for childbirth: a population-based study in rural Tanzania. Health Policy Plan. 2009;24:279–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ministry of Health and Social Welfare. Standards-based Management and Recognition for Improving Quality and Newborn Care: Assessment Tool. Dar Es Salaam, Tanzania: Ministry of Health and Social Welfare; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ministry of Health and Social Welfare. Surveillance of HIV and syphilis infections among antenatal clinic attendees 2008. Dar Es Salaam, Tanzania: Ministry of Health and Social Welfare; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 10.IRIN. Burundi: side effects of free maternal, child healthcare. 2006. Available at: http://www.irinnews.org/report/59267/burundi-side-effects-of-free-maternal-child-healthcare. Accessed July 3, 2014.

- 11.UNAIDS. Global report: UNAIDS Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic 2013. Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS, WHO; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cresswell J, Plano Clark VL. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research. 2 ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Biesta G. Pragmatism and the philosophical foundations of mixed methods research. In: Tashakkori A, Teddlie C, eds. Sage Handbook of Mixed Methods in Social and Behavioral Research. 2 ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc; 2010:95–118. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Silal SP, Penn-Kekana L, Harris B, et al. Exploring in equalities in access to and use of maternal health services in South Africa. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.African Commission on Human and Peoples' Rights. Resolution on Involuntary Sterilization and the Protection of Human Rights in Access to HIV Services. Banjul, The Gambia: African Commission on Human and Peoples' Rights; 2013; Available at: www.achpr.org/sessions/54th/resolutions/260/. Accessed July 3, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Strode A, Mthembu S, Essack Z. “She made up a choice for me”: 22 HIV-positive women's experiences of involuntary sterilization in two South African provinces. Reprod Health Matters. 2012;20(39 suppl):61–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ahmed A, Roseman MJ, Gatsi-Mallet J. “At the hospital there are no human rights”: Reproductive and sexual rights violations of women living with HIV in Namibia. Boston, MA: Northeastern Faculty of Law; 2012; Available at: http://iris.lib.neu.edu/slaw_fac_pubs/246/. Accessed July 3, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Freedman LP, Kruk ME. Disrespect and abuse of women in childbirth: challenging the global quality and accountability agendas. Lancet. 2014;384:e42–e44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]