Abstract

Introduction:

Safer conception strategies create opportunities for HIV-serodiscordant couples to realize fertility goals and minimize periconception HIV transmission. Patient–provider communication about fertility goals is the first step in safer conception counseling.

Methods:

We explored provider practices of assessing fertility intentions among HIV-infected men and women, attitudes toward people living with HIV (PLWH) having children, and knowledge and provision of safer conception advice. We conducted in-depth interviews (9 counselors, 15 nurses, 5 doctors) and focus group discussions (6 counselors, 7 professional nurses) in eThekwini District, South Africa. Data were translated, transcribed, and analyzed using content analysis with NVivo10 software.

Results:

Among 42 participants, median age was 41 (range, 28–60) years, 93% (39) were women, and median years worked in the clinic was 7 (range, 1–27). Some providers assessed women's, not men's, plans for having children at antiretroviral therapy initiation, to avoid fetal exposure to efavirenz. When conducted, reproductive counseling included CD4 cell count and HIV viral load assessment, advising mutual HIV status disclosure, and referral to another provider. Barriers to safer conception counseling included provider assumptions of HIV seroconcordance, low knowledge of safer conception strategies, personal feelings toward PLWH having children, and challenges to tailoring safer sex messages.

Conclusions:

Providers need information about HIV serodiscordance and safer conception strategies to move beyond discussing only perinatal transmission and maternal health for PLWH who choose to conceive. Safer conception counseling may be more feasible if the message is distilled to delaying conception attempts until the infected partner is on antiretroviral therapy. Designated and motivated nurse providers may be required to provide comprehensive safer conception counseling.

Key Words: safer conception, client–provider communication, HIV prevention, South Africa

INTRODUCTION

Stable serodiscordant partnerships account for up to 60% of new HIV infections,1 and 20%–50% of men and women living with HIV desire children.2–7 As many as 30% of stable heterosexual couples in South Africa are HIV-1 serodiscordant.8,9 Safer conception strategies, including home artificial insemination, unprotected sex limited to peak fertility, male circumcision, antiretroviral therapy (ART), and preexposure antiretroviral prophylaxis, create opportunities for HIV-serodiscordant couples to realize fertility goals while minimizing periconception HIV transmission risks.10–12

Safer conception recommendations have evolved; yet, implementation has not kept pace. Before effective HIV treatment, the prevailing professional recommendation was for people living with HIV (PLWH) to avoid pregnancy.13 South Africa's constitution protects reproductive rights for PLWH, and recent guidelines from the Southern African HIV Clinicians Society and South Africa's Department of Health offer strategies for those who choose to conceive.11,14,15 The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends treatment for the infected partner in serodiscordant relationships, particularly if the couple plans to conceive.1

However, HIV-infected men and women rarely discuss fertility desires or plans with health-care providers, a critical first step to safer conception counseling. In Cape Town, over 30% of HIV-infected women and 65% of HIV-infected men attending public sector clinics were interested in having additional children; yet, only 19% and 6%, respectively, had discussed this with a health-care provider.16 Among HIV-infected women in Johannesburg with plans to conceive in the next year, 40% had a conversation about fertility plans with a provider.17 Conversations with providers about conception plans were also infrequent in Uganda,18 Argentina,19 Brazil,20 Canada,21 and the United States.22,23

Thus, many HIV-uninfected partners of PLWH are exposed to more periconception risks than necessary given the efficacy of pharmacobehavioral prevention for HIV-serodiscordant couples. For uninfected women, HIV acquisition during periconception or pregnancy periods harms her health and increases the risk of perinatal transmission. We used qualitative methods to understand whether fertility assessments were taking place in eThekwini District, South Africa, an HIV-endemic setting. We explored barriers to patient–provider communication about fertility intentions and providers' safer conception knowledge and clinical practices among health-care providers, including doctors, nurses, and counselors. The goal of this research is to inform interventions to limit transmission among HIV-serodiscordant partners who choose to conceive.

METHODS

Setting

We conducted in-depth interviews (IDI) and focus group discussions (FGD) with providers from 6 public sector clinics in April and May 2012. These clinics are located in a township outside of Durban, South Africa, part of the eThekwini District where antenatal clinic HIV prevalence is estimated at 42%.24

Sampling and Recruitment

Lists of providers were generated for each clinic. Six doctors were working across the selected clinics; thus, we attempted to conduct interviews with all available doctors. For nurses and counselors, the lists were randomized and stratified by site and provider type and selected providers were invited to participate. If a selected provider refused to participate (n = 2) or was unavailable (several providers at each site were on leave or working night shifts during recruitment), we approached the next provider on the list. Interviews were conducted with counselors, nurses, and doctors. Two FGDs were conducted, one with counselors and one with professional nurses. In public sector clinics in South Africa, professional nurses are responsible for most patient consultations, including initiation of and management of ART, antenatal care (ANC), and preventing mother-to-child transmission programs (PMTCT).25 Doctors are available in the clinics on a sessional basis to see patients referred for more complex problems and often to initiate ART. Most counseling activities are the responsibility of lay counselors.26,27

Ethics

Ethics approvals were obtained from the University of the Witwatersrand Human Research Ethics Committee (Johannesburg, South Africa) and Partners Healthcare (Boston, MA).

Data Collection

The research focus was to explore whether and how providers assess fertility intentions among their HIV-infected male and female patients. This required open-ended questions through IDIs and FGDs and an inductive approach to data collection and analysis.28,29 Interview guides were developed by the authors with input from local providers. Guides explored provider practices of assessing fertility intentions among HIV-infected men and women, attitudes toward PLWH having children, knowledge of safer conception practices, and provision of safer conception advice. Interviews explored individual-level practices and attitudes, whereas focus groups explored commonly held views and accepted practices. Interviews and focus groups were conducted by research assistants fluent in English and isiZulu; sessions were audio recorded and lasted approximately an hour.

Data Preparation

Research assistants produced a complete transcript in English from either English or isiZulu language digital recordings. Each transcript was reviewed for quality by another member of the study team, and corrections were made where indicated.

Data Analysis

Content analysis was used to assess whether providers assessed the fertility goals of HIV-infected men and women in their clinic, what advice was offered, and knowledge of different safer conception strategies. Themes related to why providers do not assess fertility goals among PLWH were uncovered and explored. This iterative process was performed by the authors (L.T.M., C.M., and R.G.) using techniques described by Miles and Huberman.30

The coding team first identified major themes through independent review of a subset of transcripts. Coding was then performed to structure data into categories and create groups. Themes were then reexamined, and major and minor themes within each content area were identified. To ensure validity of the emergent data, themes were discussed with additional study team members, including the research assistants who conducted interviews and focus groups. To ensure reliability, 3 coders analyzed the data independently. Results from each phase of analyses were compared and discrepancies discussed until a resolution was reached. To check reliability of coding in the final phase, 9 interviews were coded by 2 coders each and then reviewed to resolve discrepancies before proceeding with coding the remaining data. NVivo10 software (QSR International, Melbourne, Australia) was used to organize the analysis.

RESULTS

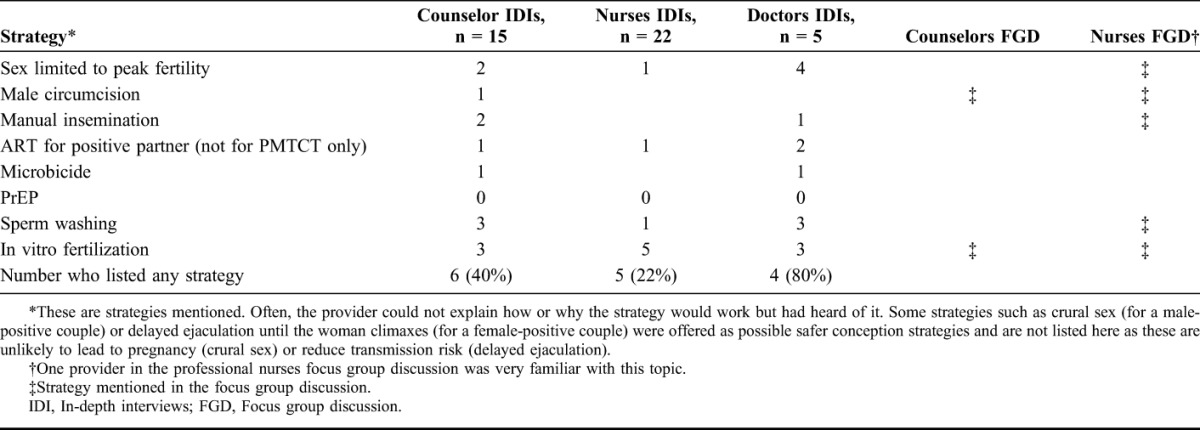

Forty-two providers participated in the study, including 29 IDIs with nurses (22), counselors (15), and doctors (5) and 2 FGDs with professional nurses (7) and counselors (6), respectively. Most participants were women (93%) who had worked in the clinic for a median of 5 (range, 1–27) years and saw a median of 11 (range, 2–60) HIV-infected patients in their last full workday (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of Participating Providers

Overview

The data are presented first as a description of providers' practices around assessing fertility desires among HIV-infected patients followed by an exploration of barriers to assessing fertility desires. Some of the categories were identified before the research (a priori) and some emerged from the data (emergent). We first describe (1) whether providers assess fertility goals (a priori) followed by a description of barriers to fertility goal assessment, including (2) assumptions of HIV seroconcordance (emergent), (3) low knowledge of safer conception strategies (a priori), (4) tension between a rights-based approach and personal feelings toward PLWH having children (emergent), and (5) challenges to delivering individualized safer sex messages in a busy clinic (emergent).

Providers Do Not Routinely Assess Fertility Goals

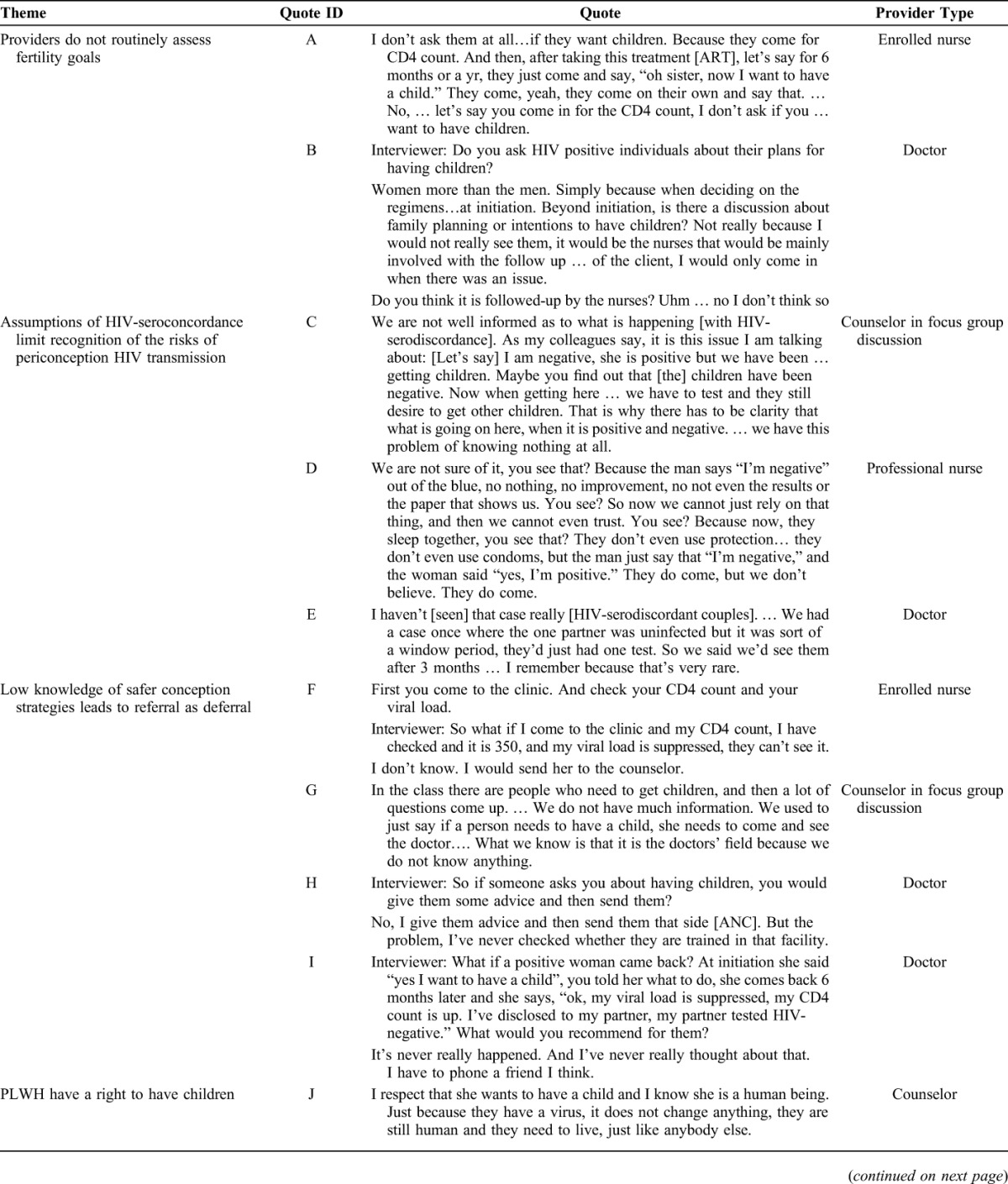

Most providers did not routinely assess fertility goals for women living with HIV and almost never assessed fertility goals for men living with HIV. Many providers spontaneously reported that patients ask about their options for having children (Table 2, quote A). Some providers assessed fertility goals for women at ART initiation to avoid efavirenz because of teratogenicity concerns (Table 2, quote B).

TABLE 2.

Representative Quotes in Support of Themes

Assumptions of HIV-Seroconcordance Limit Recognition of the Risks of Periconception HIV Transmission

Providers working as counselors, nurses, and doctors demonstrated skepticism about HIV serodiscordance—or how an HIV-infected individual could be sexually active with a partner who remained HIV uninfected. In the FGDs with counselors, who conduct couple-based HIV counseling and testing, challenges to understanding and explaining serodiscordance were a major conversation topic raised by the participants (Table 2, quote C).

Accordingly, providers did not know how to respond to patient descriptions of a serodiscordant relationship (Table 2, quote D) and underestimated the prevalence of serodiscordance (Table 2, quote E), which is about 20% among stable couples in the province of KwaZulu-Natal.8,9 When asked about the risks they worried about for PLWH who wanted to have children, most providers assumed the woman was infected and focused on issues related to the well-being of the child: the mother's health, perinatal transmission, and social issues such as the ability of the couple to support the child. During IDIs, only 7 providers (24%) listed sexual transmission to an uninfected partner as a risk they worried about.

Low Knowledge of Safer Conception Strategies Leads to Referral as Deferral

All providers were familiar with strategies to prevent mother to child transmission (PMTCT) and recommended practices, such as waiting to conceive until the CD4 count is high, initiating the woman on ART during pregnancy, encouraging adherence to ART during pregnancy, the importance of attending ANC appointments, and breastfeeding practices.

Many providers suggested that if PLWH want a child, they should come to the clinic, plan pregnancy, check CD4 cell count and HIV viral load (principally to reduce perinatal transmission risk), and disclose HIV status to partner. Because so many providers listed these tasks, interviewers probed for what providers would recommend if the individual returned to clinic having completed these assignments. Most providers then recommended referral—counselors referred to nurses, nurses referred to doctors, and doctors referred to another doctor (specialist or tertiary facility) or counselor. No provider described follow-up with a client who had successfully followed through on their recommendations and/or successfully sought care at a referral site (Table 2, quotes F–I).

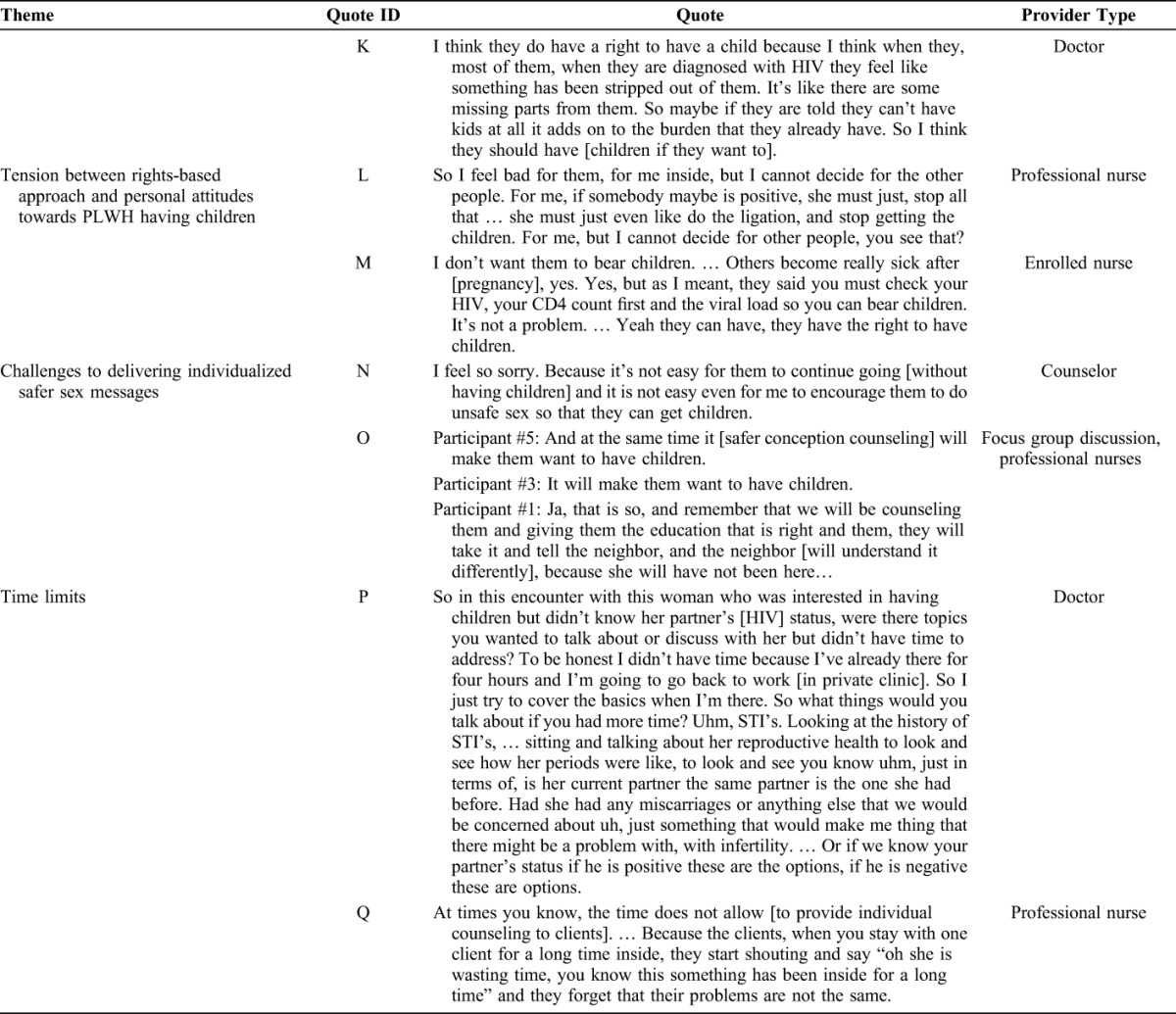

Only 2 providers (doctors) had ever offered safer conception counseling. When asked what they would offer, most providers were not familiar with the range of safer conception options and tended to focus on resource-intensive, largely unavailable strategies, such as sperm washing and in vitro fertilization (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Safer conception Strategies Mentioned by Providers

Tension Between Rights-Based Approach and Personal Attitudes Toward PLWH Having Children

Almost all providers stated that PLWH have a right to have children (Table 2, quotes J–K). This was consistent across all clinics and provider types.

Although some providers reported positive attitudes toward PLWH having children, many expressed concerns that risks to the mother and the child are too high to justify intentional conception (Table 2, quote L).

Challenges to Delivering Individualized Safer Sex Messages

Providers were uncomfortable recommending unprotected sex. This was linked to personal discomfort offering harm reduction advice and concerns that couples would increase risk behavior if given information about the relative risks of sex without condoms (Table 2, quotes N–O). The challenge of offering a message that deviates from standard condoms as prevention was linked to time constraints: nurses and doctors spend 5–10 minutes with each client (Tables 1 and 2, quotes P and Q). Deviating from standard messages in a public sector clinic may not be feasible for providers carrying out routine care.

DISCUSSION

Addressing periconception HIV transmission may reduce HIV incidence among women, men, and their children in HIV-endemic settings. Our data suggest that despite evolving guidelines, providers do not routinely ask patients about their plans for having children. When they do, the advice is for women and focuses on protecting the future fetus (avoid efavirenz, wait to conceive until the woman is healthy, come to the clinic for ANC, adhere to ART once pregnant). Now that efavirenz is offered to women regardless of pregnancy plans (based on WHO guidance and data suggesting that the risks of efavirenz teratogenicity are relatively low),31 the primary trigger for these conversations no longer exists.32 Safer conception counseling that addresses sexual transmission risk is hindered by misunderstandings of HIV serodiscordance, a lack of information about safer conception strategies, providers' discomfort with PLWH having children, and time constraints that limit capacity to deliver tailored prevention messages. Empowering providers to effectively counsel men and women living with HIV who want to conceive will require more than improving providers' technical knowledge of safer conception strategies.

Prevention for HIV-serodiscordant couples is a priority for policy makers and researchers.1,33–35 Our data suggest that counselors, nurses, and doctors responsible for implementation do not understand the principles underlying prevention for this high-risk group. Providers assumed HIV seroconcordance in stable partners and thus rarely identified sexual transmission as a concern for PLWH who want to have children. Underestimation of the prevalence of serodiscordant couples reduces safer conception counseling and any prevention for serodiscordant couples. Almost a decade ago, confusion about serodiscordance among clients and counselors in Uganda was highlighted as a public health concern.36 We reported that South African men and women in HIV-serodiscordant relationships were confused by HIV serodiscordance, but this is the first data we are aware of suggesting that providers also struggle with this concept.37 Our data suggest an urgent need for education and training about HIV serodiscordance, especially as WHO guidelines such as ART for the infected partner in a serodiscordant relationship are implemented.1

Protocol-driven patient care allows providers to manage a large number of clients but limits capacity to deliver tailored messages. Providers are overwhelmed addressing the immediate needs of clients presenting for care and do not have time or energy to solicit additional patient issues (such as plans for pregnancy) requiring non–protocol-based responses. Safer conception guidelines exist for South Africa, but providers were not aware of these. Many providers in our sample had heard something about safer conception but focused on costly methods, such as sperm washing and in vitro fertilization. As work progresses to implement safer conception protocols, the most important message within safer conception counseling may be to delay conception attempts until the infected partner is on ART with suppressed viral load. Adding this distilled message to existing protocols for ART initiation, family planning, and HIV counseling may promote safer conception behavior without overwhelming providers. In addition, efforts to disseminate safer conception guidelines may empower providers to address this topic as part of the guideline-based care.

Additional safer conception methods (preexposure antiretroviral prophylaxis for the uninfected partner, limiting unprotected sex to peak fertility, male circumcision, and manual insemination for female infected partners) could be explained by a provider with supplemental training. Our data suggest that PLWH would most benefit from a reliable provider with the information, motivation, and time to address safer conception at each clinic site. Steiner et al38 considered who should provide preconception care for PLWH from the US perspective and suggested a medical home model, call centers, and/or web-based consultation. At present, these are not viable solutions for public sector clinics in South Africa. The Southern African HIV Clinicians guidelines and the Department of Health guidelines do not specify who should provide preconception counseling. It is clear from our data that specific responsibility needs to be assigned to limit referral as deferral. Safer conception training for nurses in family planning and HIV clinics may be a good starting point because doctors are rarely available and nurses can prescribe antiretrovirals for prevention.

Many providers in our sample were conflicted between reproductive rights policies and personal feelings about PLWH having children, with opinions nearly identical to those expressed a decade ago.14 Providers' personal feelings about PLWH having children may hinder their capacity to provide quality counseling and care, no matter how simple the message. Data suggest that PMTCT successes have made providers more comfortable with women having children18 (this dataset, data not shown); increased information about safer conception may similarly influence providers to support conception among PLWH. The first pillar of PMTCT is to prevent infection among women of reproductive age.39

Thus, uptake of safer conception counseling may be increased by framing it as an important part of PMTCT—a strategy to prevent transmission before the woman is infected, which clearly benefits the woman's health and that of her child. This framing also provides an opening for engaging male partners in prevention, through their desire to father uninfected children and the role they play in conception.40–43

Limitations to these data are those inherent to qualitative research. Although these data are rich and revealed unanticipated themes, few providers were sampled and the findings may not be generalizable: these findings should be explored in a larger sample. Because of the nature of qualitative interview and FGD techniques, there is a risk of social desirability bias. Strengths of these data include opinions from a range of providers working in the public sector in an area with high HIV prevalence after publication of safer conception guidelines.

In conclusion, our data suggest that providers need information about HIV serodiscordance and efficacy of safer conception strategies to move beyond discussing perinatal transmission and maternal health for PLWH considering conception. Distilling the basic safer conception message to delaying conception attempts until the infected partner is on ART with viral load suppression may make it feasible for providers to offer useful advice within current protocols. Designated nurse providers with knowledge and motivation may be required to provide comprehensive safer conception counseling.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the providers who participated in this study and the Maternal, Adolescent, and Child Health Research team that participated in data collection and preparation.

Footnotes

Supported by the NICHD (R03-HD072602) and the Canada-Sub-Saharan Africa HIV/AIDS Network (CANSSA). The analysis was also supported by NIH grants K23 MH095655, K24MH87227, K24MH094214, K23MH096651, and the Harvard CFAR (P30 AI060354).

The content is the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. Guidance on Couples HIV Testing and Counselling Including Antiretroviral Therapy for Treatment and Prevention in Serodiscordant Couples. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Myer L, Morroni C, Rebe K. Prevalence and determinants of fertility intentions of HIV-infected women and men receiving antiretroviral therapy in South Africa. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2007;21:278–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brubaker SG, Bukusi EA, Odoyo J, et al. Pregnancy and HIV transmission among HIV-discordant couples in a clinical trial in Kisumu, Kenya. HIV Med. 2011;12:316–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beyeza-Kashesya J, Ekstrom AM, Kaharuza F, et al. My partner wants a child: a cross-sectional study of the determinants of the desire for children among mutually disclosed sero-discordant couples receiving care in Uganda. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Homsy J, Bunnell R, Moore D, et al. Reproductive intentions and outcomes among women on antiretroviral therapy in rural Uganda: a prospective cohort study. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nakayiwa S, Abang B, Packel L, et al. Desire for children and pregnancy risk behavior among HIV-infected men and women in Uganda. AIDS Behav. 2006;10(4 suppl):S95–S104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Awiti Ujiji O, Ekstrom AM, Ilako F, et al. “I will not let my HIV status stand in the way.” Decisions on motherhood among women on ART in a slum in Kenya—a qualitative study. BMC Womens Health. 2010;10:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lurie MN, Williams BG, Zuma K, et al. Who infects whom? HIV-1 concordance and discordance among migrant and non-migrant couples in South Africa. AIDS. 2003;17:2245–2252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lingappa JR, Lambdin B, Bukusi EA, et al. Regional differences in prevalence of HIV-1 discordance in Africa and enrollment of HIV-1 discordant couples into an HIV-1 prevention trial. PLoS One. 2008;3:e1411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matthews L, Mukherjee J. Strategies for harm reduction among HIV-affected couples who want to conceive. AIDS Behav. 2009;13(suppl 1):S5–S11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bekker LG, Black V, Myer L, et al. Guideline on safer conception in fertile HIV-infected individuals and couples. South Afr J HIV Med. 2011;12:31–44. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matthews LT, Smit JA, Cu-Uvin S, et al. Antiretrovirals and safer conception for HIV-serodiscordant couples. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2012;7:569–578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barreiro P, Castilla JA, Labarga P, et al. Is natural conception a valid option for HIV-serodiscordant couples? Hum Reprod. 2007;22:2353–2358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harries J, Cooper D, Myer L, et al. Policy maker and health care provider perspectives on reproductive decision-making amongst HIV-infected individuals in South Africa. BMC Public Health. 2007;7:282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Department of Health Republic of South Africa. National Contraception and Fertility Planning Policy and Service Delivery Guidelines. Pretoria, South Africa: World Health Organization; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cooper D, Moodley J, Zweigenthal V, et al. Fertility intentions and reproductive health care needs of people living with HIV in Cape Town, South Africa: implications for integrating reproductive health and HIV care services. AIDS Behav. 2009;13(suppl 1):38–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schwartz SR, Mehta SH, Taha TE, et al. High pregnancy intentions and Missed opportunities for patient-provider communication about fertility in a South African cohort of HIV-positive women on antiretroviral therapy. AIDS Behav. 2012;16:69–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wanyenze RK, Wagner GJ, Tumwesigye NM, et al. Fertility and contraceptive decision-making and support for HIV infected individuals: client and provider experiences and perceptions at two HIV clinics in Uganda. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gogna ML, Pecheny MM, Ibarlucia I, et al. The reproductive needs and rights of people living with HIV in Argentina: health service users' and providers' perspectives. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69:813–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paiva V, Filipe EV, Santos N, et al. The right to love: the desire for parenthood among men living with HIV. Reprod Health Matters. 2003;11:91–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Loutfy MR, Blitz S, Zhang Y, et al. Self-reported preconception care of HIV-positive women of reproductive Potential: A Retrospective Study. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care. 2014;13:424–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Finocchario-Kessler S, Dariotis JK, Sweat MD, et al. Do HIV-infected women want to discuss reproductive plans with providers, and are those conversations occurring? AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2010;24:317–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mindry D, Wagner G, Lake J, et al. Fertility desires among HIV-infected men and women in Los Angeles County: client needs and provider perspectives. Matern Child Health J. 2013;17:593–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Department of Health South Africa. National Antenatal Sentinel HIV and Syphilis Prevalence Survey in South Africa, 2010. Pretoria, South Africa: National Department of Health; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dohrn J, Nzama B, Murrman M. The impact of HIV scale-up on the role of nurses in South Africa: time for a new approach. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;52(suppl 1):S27–S29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sprague C, Chersich MF, Black V. Health system weaknesses constrain access to PMTCT and maternal HIV services in South Africa: a qualitative enquiry. AIDS Res Ther. 2011;8:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Rooyen H, Durrheim K, Lindegger G. Advice-giving difficulties in voluntary counselling and testing: a distinctly moral activity. AIDS Care. 2011;23:281–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ulin PR, Robinson ET, Tolley EE. Qualitative Methods in Public Health: a field guide for applied research. San Francisco: Jolley-bass; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook. 2nd ed Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 31.World Health Organization. Use of Efavirenz During Pregnancy: A Public Health Perspective. Technical Update on Treatment Optimization. Geneva Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Department of Health Republic of South Africa. The South African Antiretroviral Treatment Guidelines 2013. Pretoria, South Africa: Department of Health; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:493–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baeten JM, Donnell D, Ndase P, et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV prevention in heterosexual men and women. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:399–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.World Health Organization. Consolidated Guidelines on the Use of Antiretroviral Drugs for Treating and Preventing HIV Infection: Recommendations for a Public Health Approach. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bunnell RE, Nassozi J, Marum E, et al. Living with discordance: knowledge, challenges, and prevention strategies of HIV-discordant couples in Uganda. AIDS Care. 2005;17:999–1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Matthews LT, Crankshaw T, Giddy J, et al. Reproductive decision-making and periconception practices among HIV-positive men and women attending HIV services in durban, South Africa. AIDS Behav. 2013;17:461–470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Steiner RJ, Dariotis JK, Anderson JR, et al. Preconception care for people living with HIV: recommendations for advancing implementation. AIDS. 2013;27(suppl 1):S113–S119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.World Health Organization. PMTCT Strategic Vision 2010–2015: Preventing Mother-to-Child Transmission of HIV to Reach the UNGASS and Millennium Development Goals. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Conkling M, Shutes EL, Karita E, et al. Couples' voluntary counselling and testing and nevirapine use in antenatal clinics in two African capitals: a prospective cohort study. J Int AIDS Soc. 2010;13:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Peltzer K, Jones D, Weiss SM, et al. Promoting male involvement to improve PMTCT uptake and reduce antenatal HIV infection: a cluster randomized controlled trial protocol. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bertine SL, Sylvere BB, Marcelle AS, et al. Male involvement in the prevention of vertical transmission of HIV in Ivory Coast. Abstract #THPE237. XIX International AIDS Conference/AIDS2012; 2012; Washington DC.

- 43.Villar-Loubet OM, Cook R, Chakhtoura N, et al. HIV knowledge and sexual risk behavior among pregnant couples in South Africa: the PartnerPlus project. AIDS Behav. 2013;17:479–487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]