Introduction

Bladder cancer is the most commonly diagnosed malignancy of the genitourinary tract. In 2013, an estimated 74,690 new cases were diagnosed and there were 15,580 deaths from bladder cancer in the United States.[1] The predominant histologic subtype is urothelial, accounting for 90% of cases in developed countries.[2] Superficial, non-muscle invasive urothelial carcinoma accounts for 70% of new bladder cancer diagnoses.[3] High-risk, typically high grade and T1 lesions, will progress to invade the muscularis propria in 20-25% of patients.[4] The remainder of new diagnoses are either muscle-invasive, locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma. Approximately 50% of patients with muscle-invasive disease will have a distant recurrence after radical cystectomy.[5]

Unfortunately, metastatic urothelial carcinoma portends a very poor prognosis. Treatment with standard first-line chemotherapy regimens such as gemcitabine/cisplatin (GC) or dose-dense methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin, and cisplatin (MVAC) leads to a median overall survival of only approximately 15 months.[6, 7] Furthermore, despite better detection modalities and molecular understanding of the disease, there has been no significant improvement in survival over the past twenty years. Interestingly, a small subset of patients with metastatic disease are long-term survivors, with 5-year survival rates of 6.8%.[7], but there is limited data describing which patient- or tumor-related features associate with long-term survival. Here, we present two patients with bone-predominant metastatic urothelial cancer who have had prolonged survival with limited treatment. We also discuss current understanding of prognostic factors in metastatic urothelial carcinoma, and summarize potential future areas of investigation.

Case 1

A 65-year-old male with a long-standing smoking history presented with gross hematuria. A computed tomography (CT) scan showed a mass in the left lateral bladder wall and indeterminate size right-sided pelvic lymph nodes. The patient then underwent cystoscopy and transurethral resection of bladder tumor (TURBT) with pathology showing a high-grade urothelial carcinoma with evidence of muscle invasion with focal areas concerning for lymphovascular invasion. The patient then completed 3 cycles of dose-dense MVAC with follow-up imaging showing only some irregular wall thickening in the left bladder wall. He was then, unfortunately, lost to follow-up for several months. Approximately 11 months following initial presentation, the patient re-established care and was found on imaging to have evidence of recurrence in the left lateral bladder wall. This was completely resected and pathology was consistent with the earlier specimen. Following this TURBT, the patient underwent concomitant chemoradiation with low-dose weekly cisplatin and subsequent imaging revealed no evidence of disease. Approximately 21 months from initial diagnosis, he developed severe right shoulder pain with subsequent pathologic fracture. The patient was taken to the operating room for fixation and biopsy with pathology showing metastatic urothelial carcinoma. He was then treated with palliative radiotherapy. Restaging bone scan showed multiple osseous metastases involving both the axial and appendicular skeleton. There was no evidence of liver or lung metastases on CT. He was enrolled on a clinical trial of combination docetaxel and vandetanib for 4 months until restaging imaging showed progression into the soft tissue of the pre-existing bony metastatic lesions in the right ischium and right posterior 5th rib. The patient then received 4 cycles of gemcitabine and paclitaxel before going on a treatment holiday with every 3-6 month surveillance imaging. After 3 years off therapy and almost 6 years since diagnosis, bone scan continued to not show any signs of recurrence (Figure 1). However, surveillance CT imaging revealed new jejunal thickening. He underwent a small bowel resection with pathology confirming recurrence of previously diagnosed urothelial primary with evidence of perineural and lymphovascular invasion. The patient has now been surveyed for 6 months since the surgery, with reimaging every 3 months without any further evidence of disease recurrence.

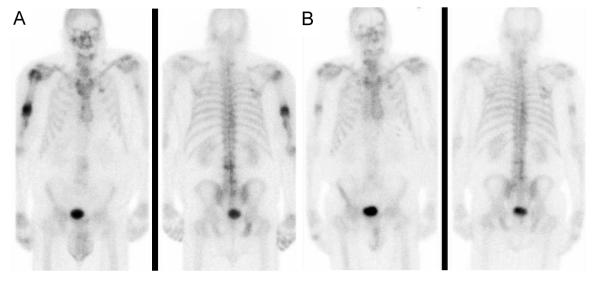

Figure 1.

A. Bone scan prior to initiation of chemotherapy with gemcitabine and paclitaxel

B. Bone scan 36 months after completion of chemotherapy

Case 2

A 74-year-old male presented with superficial, non-muscle invasive urothelial carcinoma and was treated with multiple TURBTs and intravesicular BCG. Three years after initial presentation, he developed hematuria. Cystoscopy with TURBT revealed progression to high-grade muscle-invasive urothelial cancer and evidence of carcinoma in situ but no lymphovascular invasion in the left lateral bladder wall. The patient underwent chemoradiotherapy with weekly paclitaxel at a dose of 50 mg/m2 after declining radical cystectomy. Four months after completing concomitant chemoradiation, the patient presented with neck pain and was noted to have cervical spine metastases at C1, C3, and C4 on CT. A biopsy was consistent with metastatic urothelial cancer. He underwent proton beam radiation therapy to the cervical spine and subsequent spinal fusion. Restaging CT scan revealed prominent peri-aortic and aorto-caval lymph nodes, the largest measuring 1.6 cm in diameter. Bone scan imaging demonstrated new bony metastatic disease in the sternum, ribs, left scapula, and multiple thoracic vertebrae. He then completed 6 cycles of chemotherapy with gemcitabine and cisplatin with complete regression of all suspicious retroperitoneal lymph nodes. He has continued with surveillance imaging every 3-6 months for 2 years without evidence of soft tissue or bony disease progression despite being off all treatment (Figure 2).

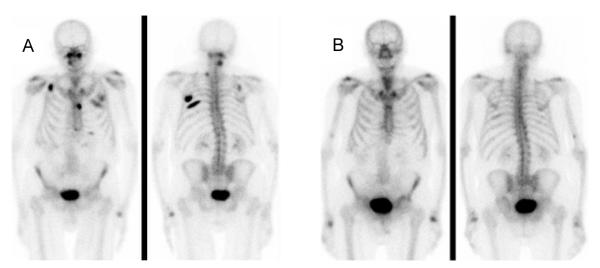

Figure 2.

A. Bone scan prior to initiation of chemotherapy B. Bone scan 20 months after completion of chemotherapy

Discussion

Our early understanding of prognosis in metastatic bladder cancer is based on long-term follow-up of an intergroup trial comparing cisplatin to MVAC.[8] In this analysis, non-urothelial histology, poor performance status, and the presence of either bone or liver metastases were found to be poor prognostic features.[9] Subsequently, Bajorin et al. also demonstrated that patients with poor performance status and/or the presence of “visceral metastases” had worse outcomes in a cohort of patients treated with MVAC.[10] In this and later studies, “visceral metastases” were grouped and defined as the presence of either liver, lung, and/or bone metastases. Interestingly, though significant in the univariate analysis, liver, lung, and bone metastases were not independently prognostic in the multivariate analysis. Since then, multiple other studies have shown similar results indicating the importance of “visceral metastases” on outcomes in metastatic urothelial cancer.[11-14] However, none of these studies defined bone metastases as an independent predictor of poor outcome. Conversely, in two studies, the presence of liver metastases alone conferred worse outcomes, with bone metastases not influencing survival.[15, 16] Taken together, these studies suggest that the number of sites of metastases and possibly the presence of liver metastases drive the poor prognosis in metastatic urothelial cancer and bone involvement may not negatively affect prognosis.

Our report describes two cases of long-term survival in patients with bone-predominant metastatic urothelial cancer. In review of the literature, only one other report of this phenomenon was identified.[17] In that report, a 38 year old patient with biopsy-proven metastatic urothelial cancer only to bone received 6 cycles of carboplatin and gemcitabine with complete radiographic resolution of all sites of disease. He then underwent radical cystoprostatectomy and pelvic lymph node dissection with pathology also demonstrating a complete response in the surgical specimen. After two years, the patient did not have evidence of disease recurrence.

Bone is an unrecognized, relatively common site of metastasis of from urothelial carcinoma. Reports estimate the frequency of bone metastases range from 25-47%.[18] However, only 5-15% of patients with urothelial cancer will have bone as the only site of metastatic disease.[18, 19] Neither the prognosis nor mechanism of development of bone-predominant metastatic urothelial cancer have been clearly elucidated. One recent study indicated that older patients had a higher frequency of single-site metastasis, including to bone, based on ICD-9 coding of hospitalized patients.[20] Potentially, as evidenced in this report, bone-predominant disease may be indicative of a good prognosis.

One possible mechanism may be that the genetic changes in tumors of patients with bone only or bone predominant metastases may be associated with either a specific treatment-sensitivity or a less aggressive disease phenotype. An example of the former would be case 1, a patient whose disease progressed rapidly after initiating therapy with docetaxel and vandetanib, but had a dramatic and prolonged response to gemcitabine and paclitaxel. Furthermore, recent work suggests that 69% of invasive urothelial bladder carcinomas have targetable genomic alterations, particularly along the PI3K/Akt/mTOR and RTK/MAPK pathways.[21] By utilizing gene sequencing panels to identify and subsequently target these actionable mutations, we may be able to achieve better long term outcomes, not only in bone-predominant disease, but all patients with metastatic urothelial carcinoma.

Conclusion

In summary, the prognosis of patients with bone predominant metastatic urothelial cancer is not well-defined by the current literature. Here, we described two cases with excellent long-term survival. Additional observations of this sort in patients with bone predominant metastatic urothelial cancer will facilitate further study into the underlying molecular mechanisms.

Clinical Practice Points.

Performance status and visceral metastases are established prognostic features in patients with bladder cancer

A small subset of patients with metastatic urothelial carcinoma have excellent long term overall survival

Contrary to early reports, bone-predominant metastatic disease may have better clinical outcomes, though this requires further investigation

Ultimately, molecular characterization and identification of individual targetable genomic alterations may improve patient outcomes in metastatic urothelial carcinoma

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Bibliography

- 1.Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, et al. Cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64(1):9–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clark PE, Agarwal N, Biagioli MC, et al. Bladder cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2013;11(4):446–75. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2013.0059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kirkali Z, Chan T, Manoharan M, et al. Bladder cancer: epidemiology, staging and grading, and diagnosis. Urology. 2005;66(6 Suppl 1):4–34. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.07.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peyromaure M, Zerbib M. T1G3 transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder: recurrence, progression and survival. BJU Int. 2004;93(1):60–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.2004.04556.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Malkowicz SB, van Poppel H, Mickisch G, et al. Muscle-invasive urothelial carcinoma of the bladder. Urology. 2007;69(1 Suppl):3–16. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2006.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sternberg CN, de Mulder PH, Schornagel JH, et al. Randomized phase III trial of high-dose-intensity methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin, and cisplatin (MVAC) chemotherapy and recombinant human granulocyte colony-stimulating factor versus classic MVAC in advanced urothelial tract tumors: European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Protocol no. 30924. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(10):2638–46. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.10.2638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.von der Maase H, Hansen SW, Roberts JT, et al. Gemcitabine and cisplatin versus methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin, and cisplatin in advanced or metastatic bladder cancer: results of a large, randomized, multinational, multicenter, phase III study. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18(17):3068–77. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.17.3068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Loehrer PJ, Sr., Einhorn LH, Elson PJ, et al. A randomized comparison of cisplatin alone or in combination with methotrexate, vinblastine, and doxorubicin in patients with metastatic urothelial carcinoma: a cooperative group study. J Clin Oncol. 1992;10(7):1066–73. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1992.10.7.1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saxman SB, Propert KJ, Einhorn LH, et al. Long-term follow-up of a phase III intergroup study of cisplatin alone or in combination with methotrexate, vinblastine, and doxorubicin in patients with metastatic urothelial carcinoma: a cooperative group study. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15(7):2564–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.7.2564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bajorin DF, Dodd PM, Mazumdar M, et al. Long-term survival in metastatic transitional-cell carcinoma and prognostic factors predicting outcome of therapy. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17(10):3173–81. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.10.3173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bellmunt J, Albanell J, Paz-Ares L, et al. Pretreatment prognostic factors for survival in patients with advanced urothelial tumors treated in a phase I/II trial with paclitaxel, cisplatin, and gemcitabine. Cancer. 2002;95(4):751–7. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin CC, Hsu CH, Huang CY, et al. Prognostic factors for metastatic urothelial carcinoma treated with cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil-based regimens. Urology. 2007;69(3):479–84. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2006.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stadler WM, Hayden A, von der Maase H, et al. Long-term survival in phase II trials of gemcitabine plus cisplatin for advanced transitional cell cancer. Urol Oncol. 2002;7(4):153–7. doi: 10.1016/s1078-1439(02)00182-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.von der Maase H, Sengelov L, Roberts JT, et al. Long-term survival results of a randomized trial comparing gemcitabine plus cisplatin, with methotrexate, vinblastine, doxorubicin, plus cisplatin in patients with bladder cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(21):4602–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.07.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bellmunt J, Choueiri TK, Fougeray R, et al. Prognostic factors in patients with advanced transitional cell carcinoma of the urothelial tract experiencing treatment failure with platinum-containing regimens. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(11):1850–5. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.4599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sengelov L, Kamby C, von der Maase H. Metastatic urothelial cancer: evaluation of prognostic factors and change in prognosis during the last twenty years. Eur Urol. 2001;39(6):634–42. doi: 10.1159/000052520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Joudi FN, Dahmoush L, Spector DM, et al. Complete response of bony metastatic bladder urothelial cancer to neoadjuvant chemotherapy and cystectomy. Urol Oncol. 2006;24(5):403–6. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2005.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shinagare AB, Ramaiya NH, Jagannathan JP, et al. Metastatic pattern of bladder cancer: correlation with the characteristics of the primary tumor. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;196(1):117–22. doi: 10.2214/AJR.10.5036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sengelov L, Kamby C, von der Maase H. Pattern of metastases in relation to characteristics of primary tumor and treatment in patients with disseminated urothelial carcinoma. J Urol. 1996;155(1):111–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bianchi M, Roghmann F, Becker A, et al. Age-stratified distribution of metastatic sites in bladder cancer: A population-based analysis. Can Urol Assoc J. 2014;8(3-4):E148–58. doi: 10.5489/cuaj.787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network Comprehensive molecular characterization of urothelial bladder carcinoma. Nature. 2014;507(7492):315–22. doi: 10.1038/nature12965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]