SUMMARY

Macroautophagy (autophagy) is a lysosome-dependent degradation process that has been implicated in age-associated diseases. Autophagy is involved in both cell survival and cell death, but little is known about the mechanisms that distinguish its use during these distinct cell fates. Here, we identify the microRNA, miR-14, as being both necessary and sufficient for autophagy during developmentally regulated cell death in Drosophila. Loss of miR-14 prevented induction of autophagy during salivary gland cell death, but had no effect on starvation-induced autophagy in the fat body. Moreover, mis-expression of miR-14 was sufficient to prematurely induce autophagy in salivary glands, but not in the fat body. Importantly, miR-14 regulates this context-specific autophagy through its target, inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate kinase 2 (ip3k2) thereby affecting inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) signaling and calcium levels during salivary gland cell death. This study provides the first in vivo evidence of microRNA regulation of autophagy through modulation of IP3 signaling.

Keywords: autophagy, programmed cell death, microRNA, miR-14, IP3 kinase, IP3 signaling, calcium, Calmodulin

INTRODUCTION

Autophagy is a conserved catabolic process that delivers cytoplasmic materials, including proteins and organelles, to lysosomes for degradation (Mizushima and Komatsu, 2011). Autophagy functions in multiple cellular contexts, including infection, stress, and cell death, and is involved in multiple age-associated disorders, such as cancer and neurodegeneration. During starvation, cells utilize autophagy to maintain nutrient homeostasis and for cell survival. Autophagy can also function in cell death, such as in the developmentally regulated death of larval salivary gland cells in Drosophila (Berry and Baehrecke, 2007). Although much is known about the mechanisms that control autophagy in response to nutrient deprivation, little is known about the regulation of autophagy during developmental cell death.

microRNAs were first discovered as regulators of developmental timing; a process which appears to be conserved among metazoans (Ambros, 2011; Sokol, 2012). microRNAs are small, non-coding RNAs that primarily function by down-regulating gene expression post-transcriptionally through base pairing to the 3′untranslated regions (UTRs) of their target mRNAs. In Drosophila, microRNAs regulate multiple processes during development, including developmental timing, steroid hormone signaling, metabolism, and caspase activation (Brennecke et al., 2003; Caygill and Johnston, 2008; Varghese and Cohen, 2009; Varghese et al., 2010; Xu et al., 2003). The programmed degradation of larval salivary glands during Drosophila development requires the precise temporal regulation of hormone signaling, cell growth arrest, caspase activation, and autophagy (Berry and Baehrecke, 2007; Jiang et al., 1997; Lee and Baehrecke, 2001; Martin and Baehrecke, 2004). However, no microRNAs have been previously shown to control the destruction of this tissue.

microRNAs have been implicated in the regulation of autophagy (Frankel et al., 2011; Zhu et al., 2009). However, all previous studies have focused on the regulation of autophagy by microRNAs during nutrient deprivation in derived cell lines, and no evidence exists that microRNAs regulate autophagy under physiological conditions in animals. In addition, microRNAs have not been shown to influence autophagy during cell death, and how microRNAs influence autophagy is poorly understood.

Here we show that the microRNA, miR-14, is necessary for salivary gland degradation. While previous studies have shown that miR-14 can regulate hormone signaling and caspase activity in other contexts, we find that miR-14 does not influence either of these processes during salivary gland cell death. Rather, we ascertain that miR-14 regulates autophagy in dying salivary gland cells, and does so by targeting ip3k2, a gene that is involved in inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) signaling and calcium release from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). We determine that IP3 signaling, as well as the calcium binding messenger protein, Calmodulin, are necessary for the induction of autophagy during salivary gland cell death. In addition, through its regulation of ip3k2, miR-14 is necessary for a rise in calcium levels coinciding with salivary gland death. Moreover, this regulation of autophagy by miR-14, IP3 signaling, and Calmodulin appears to be specific to the context of the developmental cell death of larval salivary glands, as starvation-induced autophagy in the larval fat body was not influenced by altered function of miR-14, ip3k2, IP3 signaling, or Calmodulin.

RESULTS

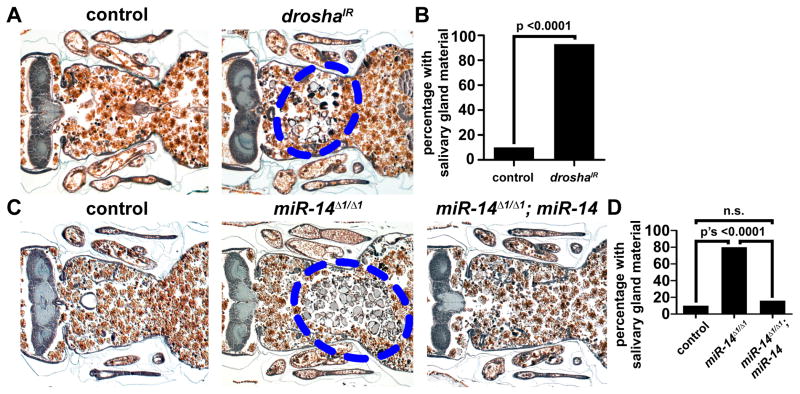

miR-14 functions in salivary gland cell death

The larval salivary glands of Drosophila undergo programmed cell death 14–16 hours after puparium formation resulting in no visible gland remnants by 24 hours after puparium formation (described in Figures S1A and S1B). To determine if micoRNAs play a role in regulating salivary gland cell death, we inhibited microRNAs in the salivary gland by knocking down the microRNA processing factors drosha or dicer-1 via salivary gland-specific RNAi. At 24 hours after puparium formation, histological analyses revealed that salivary gland cell fragments persisted in animals expressing a double-stranded inverse repeat construct designed to target either drosha (droshaIR) or dicer-1 (dicer-1IR), but no residual salivary gland material was observed in control animals at the same stage (Figures 1A, 1B, S1E and S1F; emphasized in Figure S1C). We then determined the profile of microRNAs expressed in dying salivary glands (Table S1), and we screened 11 available mutants of gland-expressed microRNA genes for defects in salivary gland clearance. One null mutant, miR-14Δ1, displayed a strong failure in salivary gland clearance (Figures 1C and 1D). In addition, expression of miR-14 specifically in salivary glands of homozygous miR-14 Δ1 mutant animals rescued the degradation defect in this tissue (Figures 1C and 1D). Furthermore, expression of droshaIR in the salivary glands of homozygous miR-14 mutant animals failed to enhance the phenotype observed in miR-14 mutant animals alone (Figures S1G and S1H). These results indicate that miR-14 is required for salivary gland clearance, that miR-14 functions in a salivary gland autonomous manner, and that if other microRNAs are required for salivary gland clearance, they function in the same genetic pathway as miR-14.

Figure 1. Drosha and miR-14 are required for salivary gland degradation.

(A) Samples from control animals (+/w; +/UAS-droshaIR), n = 16 (left), and those with salivary gland-specific knockdown of drosha (fkh-GAL4/w; +/UAS-droshaIR), n = 27 (right), analyzed by histology for the presence of salivary gland material (blue dotted circle) 24 h after puparium formation.

(B) Quantification of data from (A). Data are represented as mean. Statistical significance was determined using a Chi-squared test.

(C) Samples from control animals (w; +/miR-14Δ1; fkh-GAL4/UAS-luciferase-miR-14), n = 39 (left), miR-14 null mutants (w; miR-14Δ1/miR-14Δ1; +/UAS-luciferase-miR-14), n = 25 (middle), and miR-14 null mutants with salivary gland-specific expression of miR-14 (w; miR-14Δ1/miR-14Δ1; fkh-GAL4/UAS-luciferase-miR-14), n = 25 (right), analyzed by histology for the presence of salivary gland material (blue dotted circle) 24 h after puparium formation.

(D) Quantification of data from (C). Data are represented as mean. Statistical significance was determined using a Chi-squared test.

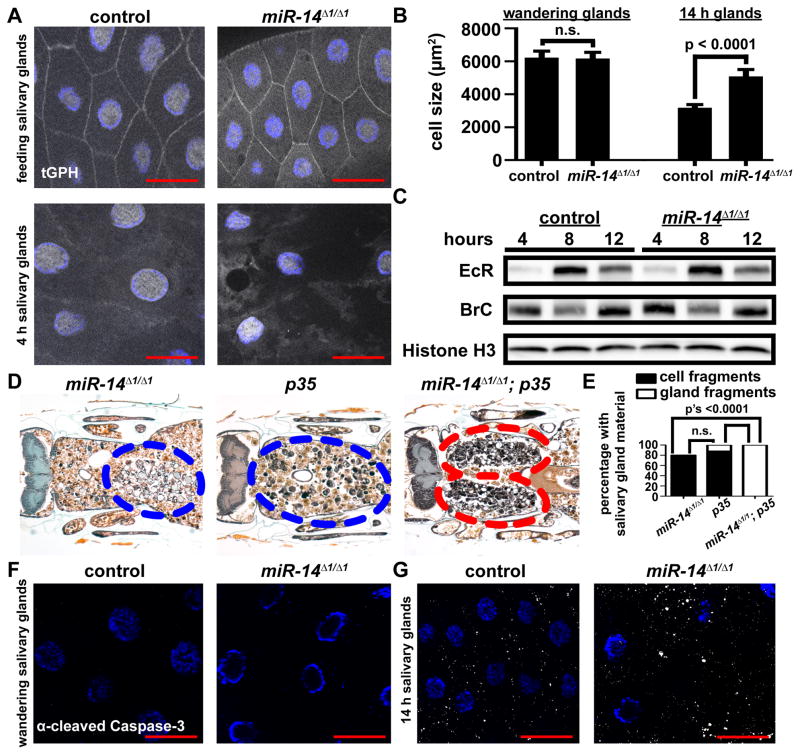

miR-14 does not regulate hormone signaling, cell growth arrest, or caspase activation during salivary gland cell death

Failure of salivary gland cell growth arrest results in attenuation of autophagy and incomplete salivary gland degradation (Berry and Baehrecke, 2007). Therefore, we tested if loss of miR-14 influences salivary gland cell growth arrest by using the tGPH reporter for phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-P3 (PIP3) activity (Britton et al., 2002), and by measuring cell area. We observed neither a difference in tGPH localization nor an increase cell area in control and miR-14 mutant salivary glands (Figures 2A and 2B). These data indicate that the salivary gland degradation defect in miR-14 mutant animals is not an indirect consequence of a defect in cell growth arrest.

Figure 2. Loss of miR-14 does not alter cell growth, hormone signaling, or caspase activity during salivary gland degradation.

(A) Salivary glands dissected from control (+/w; +/miR-14Δ1, tGPH) and miR-14 null mutant (w; miR-14Δ1/miR-14Δ1, tGPH) animals as feeding larvae (top) and 4 h after puparium formation (bottom) for analysis of tGPH localization. Salivary glands were all stained with Hoechst (blue). Scale bars represent 50μm.

(B) Salivary gland cell size in control (+/w; +/miR-14Δ1), n ≥ 32, and miR-14 null mutant (w; miR-14Δ1/miR-14Δ1), n ≥ 29, animals dissected from wandering larvae and 14 h after puparium formation. Statistical significance was determined using a Student’s t-test. Data are represented as mean +/− SEM.

(C) Protein extracts from salivary glands 4, 8 and 12 hours after puparium formation of control (+/w; +/miR-14Δ1) and miR-14 null mutant (w; miR-14Δ1/miR-14Δ1) animals analyzed by immuno-blot with anti-Ecdysone Receptor (EcR) and anti-Broad Complex (BR-C).

(D) Samples from miR-14 null mutants (w; miR-14Δ1/miR-14Δ1; UAS-p35/+), n = 20 (left), animals with salivary gland-specific expression of p35 (w; miR-14Δ1/+; UAS-p35/fkh-GAL4), n = 26 (middle), and miR-14 null mutants with salivary gland-specific expression of p35 (w; miR-14Δ1/miR-14Δ1; UAS-p35/fkh-GAL4), n = 24 (right), analyzed by histology for the presence of salivary gland material 24 h after puparium formation. Blue dotted circles enclose cell fragments; red dotted circles enclose gland fragments.

(E) Quantification of data from (D). Data are represented as mean. Statistical significance was determined using a Chi-squared test comparing the percentages of gland fragments. (F and G) Salivary glands dissected from control (+/w; +/miR-14Δ1) and miR-14 null mutant (w; miR-14Δ1/miR-14Δ1) animals and stained with cleaved Caspase-3 antibody (white) and Hoechst (blue). Salivary glands were dissected from wandering larvae (F) and 14 h after puparium formation (G). Scale bars represent 50 μm.

Salivary gland cell death is triggered by a developmental rise in the steroid hormone 20-hydroxyecdysone (ecdysone) (Jiang et al., 1997). The Ecdysone Receptor (EcR) and its partner ultraspiracle (USP) then directly induce the transcription of multiple target genes including Broad Complex (BrC) leading to the degradation of the larval salivary glands (Gauhar et al., 2009). A previous study indicated that miR-14 can influence EcR levels based on analyses of whole pupae 24 hours after puparium formation (Varghese and Cohen, 2009). Therefore, we tested if loss of miR-14 influenced EcR and BrC levels during salivary gland death. To our surprise, neither EcR nor BrC protein levels were significantly altered in salivary glands by loss of miR-14 (Figure 2C). These data indicate that the salivary gland clearance defect that is observed in miR-14 mutant animals is not due to miR-14 regulation of either EcR or altered steroid signaling.

Caspase activity and autophagy are both required for salivary gland degradation, and these two processes appear to function independently of each other (Berry and Baehrecke, 2007). Thus, when either autophagy or caspases are inhibited, partial degradation of the salivary glands occurs resulting in a weaker degradation phenotype consisting of diffuse fragments of cellular material that we define as cell fragments. By contrast, when both caspases and autophagy are inhibited simultaneously, more intact tissue fragments in the shape of the two oval salivary glands persist resulting in a stronger phenotype that we define as gland fragments (described in Figures S1C and S1D) (Berry and Baehrecke, 2007). In miR-14 homozygous mutant animals, we observed a weaker phenotype with dispersed cellular fragments (Figures 1C and 1D), suggesting that miR-14 regulates either autophagy or caspase activity but not both.

Since miR-14 was first identified as a genetic suppressor of apoptosis (Xu et al., 2003), we examined the relationship between caspases and miR-14 in dying salivary glands. We expressed the caspase inhibitor p35 in the salivary glands of control and miR-14 homozygous mutant animals. While the weaker phenotype of salivary gland cell fragments were observed in control animals of either p35-expressing or miR-14 mutant alone, we observed a distinctly stronger phenotype of two large oval-shaped salivary gland tissue fragments in miR-14 mutant animals that also expressed p35 (Figures 2D and 2E; emphasized in Figure S1D). This enhancement of the salivary gland clearance defect indicates that miR-14 functions in an additive manner with the caspase pathway. In support of this conclusion, miR-14 mutant and control salivary glands also exhibited no clear difference in either the timing or amount of cleaved Caspase-3 immuno-fluorescence (Figures 2F and 2G). Taken together, these data indicate that loss of miR-14 does not influence caspases in dying salivary glands.

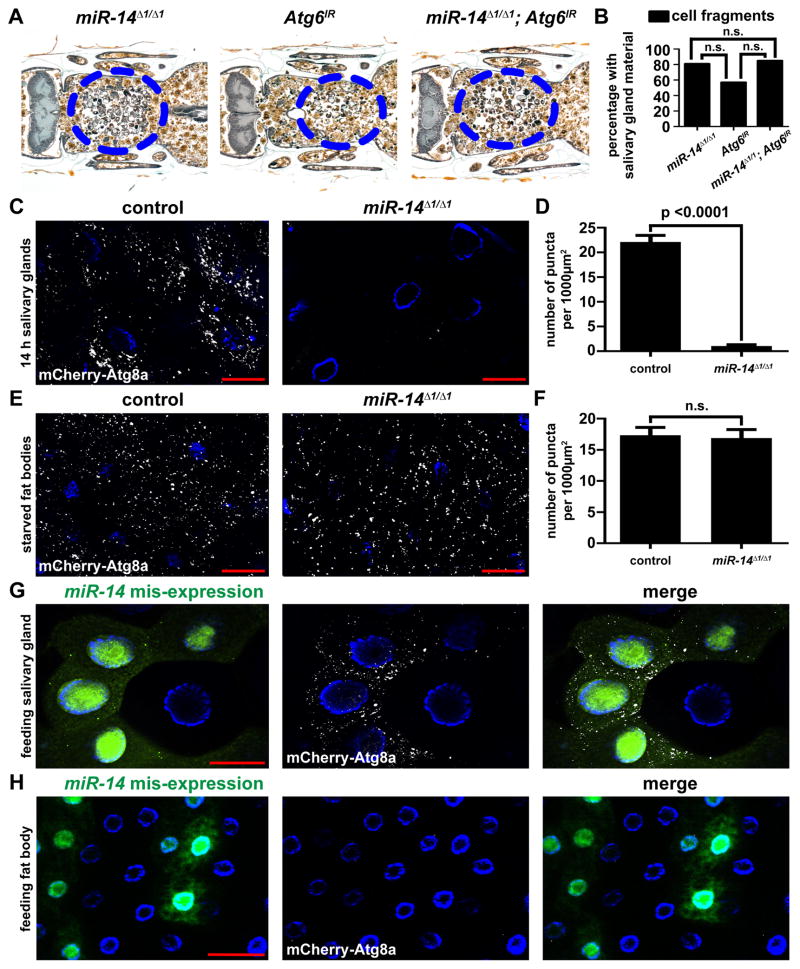

miR-14 is necessary and sufficient for autophagy during salivary gland cell death

Autophagy causes a reduction in cell size (Chang et al., 2013), and miR-14 mutant salivary gland cells failed to shrink as much as control cells (Figure 2B) suggesting that autophagy may be defective in miR-14 mutant salivary glands. To determine whether autophagy is involved in miR-14 regulation of salivary gland cell death, we inhibited autophagy by knockdown of the autophagy gene Atg6 in miR-14 mutant animals. We observed no clear differences in the cell fragment phenotypes of miR-14 homozygous mutant animals whether or not Atg6IR was expressed in salivary glands (Figures 3A and 3B). These data suggest that miR-14 functions in the same pathway as Atg6, and, therefore, regulates salivary gland cell death by autophagy. Consistent with this interpretation, homozygous miR-14 mutant salivary glands possess significantly fewer mCherry-Atg8a autophagy reporter puncta compared to heterozygous control salivary glands (Figures 3C and 3D). To determine if miR-14 is a general regulator of autophagy, we tested if this miRNA is required for starvation-induced autophagy in the larval fat body. In contrast to salivary gland cell death, we observed no difference in the amounts of mCherry-Atg8a autophagy reporter puncta in the fat bodies of control versus homozygous miR-14 mutant animals following four hours of nutrient deprivation (Figures 3E and 3F). This indicates that miR-14 is necessary for developmentally regulated autophagy in the salivary gland, but is dispensable for starvation-induced fat body autophagy.

Figure 3. miR-14 is necessary and sufficient for autophagy in salivary glands, but not fat body.

(A) Samples from miR-14 null mutants (w; miR-14Δ1/miR-14Δ1; UAS-Atg6IR/+), n = 24 (left), animals with salivary gland-specific knockdown of Atg6 (w; miR-14 Δ1/+; UAS-Atg6IR/fkh-GAL4), n = 21 (middle), and miR-14 null mutants with salivary gland-specific knockdown of Atg6 (w; miR-14Δ1/miR-14Δ1; UAS-Atg6IR/fkh-GAL4), n = 24 (right), analyzed by histology for the presence of salivary gland material 24 h after puparium formation. Blue dotted circles enclose cell fragments.

(B) Quantification of data from (A). Data are represented as mean. Statistical significance was determined using a Chi-squared test comparing the percentages of animals with gland fragments.

(C) mCherry-Atg8a was expressed in the salivary glands of control animals (+/w; +/pmCherry-Atg8a, miR-14Δ1) and in miR-14 null mutants (w; pmCherry-Atg8a, miR-14Δ1/miR-14Δ1). Salivary glands were dissected 14 h after puparium formation for analyses of mCherry-Atg8a puncta.

(D) Quantification of data from (C). Data are represented as mean +/− SEM; n ≥ 23. Statistical significance was determined using a Student’s t-test.

(E) mCherry-Atg8a was expressed in the fat bodies of control animals (+/w; +/pmCherry-Atg8a, miR-14Δ1) and in miR-14 null mutants (w; pmCherry-Atg8a, miR-14 Δ1/miR-14Δ1). Larvae were starved for 4 h, and fat bodies were dissected for analyses of mCherry-Atg8a puncta.

(F) Quantification of data from (E). Data are represented as mean +/− SEM; n ≥ 19. Statistical significance was determined using a Student’s t-test.

(G and H) Salivary glands (G) and fat bodies (H) expressing mCherry-Atg8a in all cells, and miR-14 mis-expression specifically in GFP-marked clone cells (heatshock (hs)flp/w; pmCherry-Atg8a/UAS-miR-14; act<FRT, cd2, FRT>Gal4, UAS-GFP/+) dissected from feeding larvae for analyses of mCherry-Atg8a puncta. Salivary glands and fat bodies were all stained with Hoechst (blue). Scale bars represent 50 μm.

We next tested if miR-14 is sufficient for autophagy. We observed that cell autonomous mis-expression of miR-14 was sufficient to induce premature mCherry-Atg8a puncta in the salivary glands of third instar larvae (Figure 3G), but was not sufficient to induce autophagy reporter puncta in larval fat body (Figure 3H). To ensure that this tissue specific induction of autophagy was in fact because of mis-expression of miR-14, we repeated this experiment with a second miR-14 transgenic line. Once again, autophagy was induced in the salivary gland, but not the fat body (Figures S2A and S2B). Thus, miR-14 functions to regulate autophagy during developmental salivary gland cell death, but is not involved in nutrient deprivation-induced autophagy. The observation that mis-expression of miR-14 resulted in autophagy occurring at an earlier developmental stage than in wild type (Figure 3G) suggests that during wild type development, miR-14 levels may be limiting at earlier stages.

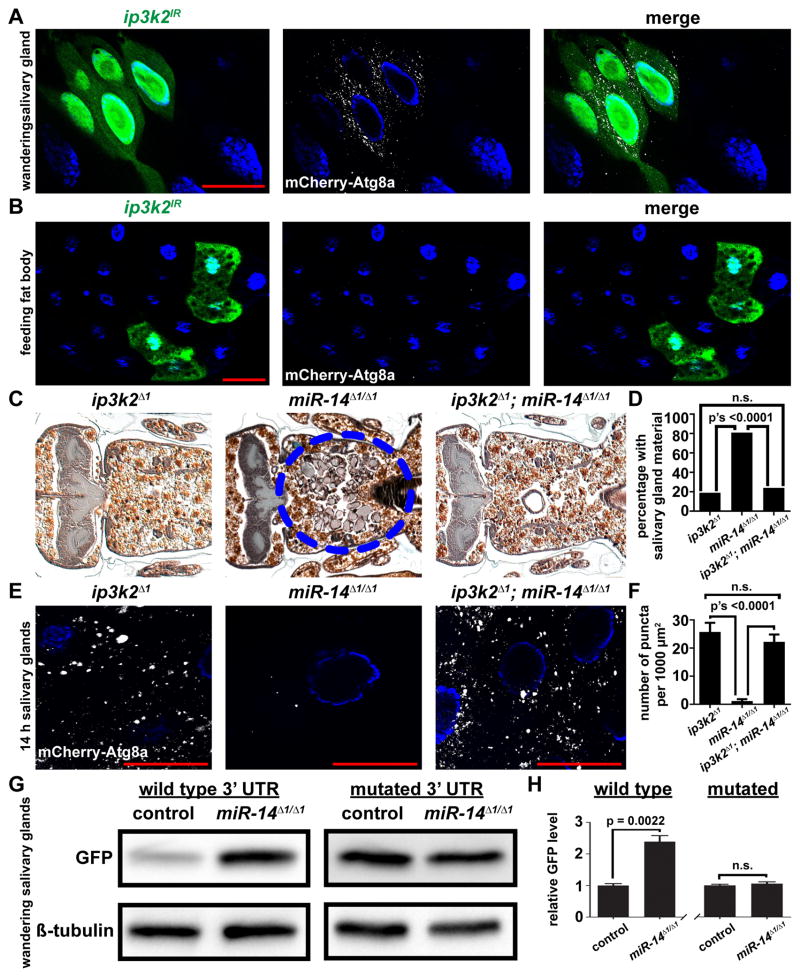

miR-14 targets the ip3k2 gene to regulate autophagy during salivary gland cell death

Our next goal was to identify targets of miR-14 that influence autophagy. We hypothesized that knockdown of miR-14 targets would result in phenotypes that are similar to those induced by mis-expression of miR-14. Knockdown of either EcR or sugarbabe, two previously-identified targets of miR-14 (Varghese and Cohen, 2009; Varghese et al., 2010), failed to induce mCherry-Atg8a autophagy reporter puncta in the salivary glands (Table S2). Therefore, we used the microRNA binding site prediction programs Pictar and Targetscan to identify candidate mir-14 target genes, and then used RNAi lines against these candidate targets to screen for the induction of mCherry-Atg8a autophagy reporter puncta (Table S2). Of the 31 genes tested, only knockdown of ip3k2 resulted in the tissue-specific induction of mCherry-Atg8a autophagy reporter puncta in salivary glands, and not in fat body (Figures 4A and 4B). To ensure that the phenotype observed was not due to an off target effect of the RNAi, we tested a second RNAi line that targeted a different sequence of ip3k2; this RNAi line also displayed the same phenotype as mis-expression of miR-14 (Figures S3A and S3B).

Figure 4. miR-14 targets inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate kinase 2 to regulate autophagy during salivary gland death.

(A and B) Salivary glands dissected from wandering larvae (A) and fat bodies dissected from feeding larvae (B) expressing mCherry-Atg8a in all cells, and ip3k2 knockdown specifically in GFP-marked clone cells (hsflp/w; pmCherry-Atg8a/UAS-ip3k2IR; act<FRT, cd2, FRT>Gal4, UAS-GFP/+) analyzed for mCherry-Atg8a puncta.

(C) Samples from ip3k2 mutant animals (ip3k2 Δ1/Y; +/miR-14Δ1), n = 21 (left), miR-14 null mutant animals (ip3k2 Δ1/w; miR-14Δ1/miR-14Δ1), n = 26 (middle), and ip3k2, miR-14 double mutant animals (ip3k2 Δ1/Y; miR-14Δ1/miR-14Δ1), n = 50 (right), analyzed by histology for the presence of salivary gland material (blue dotted circle) 24 h after puparium formation.

(D) Quantification of data from (C). Data are represented as mean. Statistical significance was determined using a Chi-squared test.

(E) mCherry-Atg8a was expressed in ip3k2 mutant animals (ip3k2 Δ1/Y; miR-14Δ1/pmCherry-Atg8a), miR-14 null mutant animals (ip3k2 Δ1/w; miR-14Δ1/miR-14Δ1, pmCherry-Atg8a), and ip3k2, miR-14 null double mutant animals (ip3k2 Δ1/Y; miR-14Δ1/miR-14Δ1, pmCherry-Atg8a). Salivary glands were dissected 14 h after puparium formation for analyses of mCherry-Atg8a puncta.

(F) Quantification of data from (E). Data are represented as mean +/− SEM; n ≥ 16. Statistical significance was determined using a Student’s t-test. Salivary glands and fat bodies were all stained with Hoechst (blue). Scale bars represent 50 μm.

(G) Protein extracts from salivary glands dissected from wandering larvae of control (w; miR-14Δ1/+; tub-GFP-ip3k2 3′UTR/+) and miR-14 null mutant (w; miR-14Δ1/miR-14Δ1; tub-GFP-ip3k2 3′UTR/+) animals expressing a GFP sensor containing either the wild type ip3k2 3′UTR or a mutated miR-14 binding site in the 3′UTR, and analyzed by immuno-blot with anti-GFP antibody.

(H) Quantification of data from (G). Wild type and mutated sensors are normalized to Beta-tubulin and plotted relative to their respective controls +/− SEM; n’s = 3. Statistical significance was determined using a Student’s t-test.

To further validate ip3k2 as a target of miR-14 by genetic epistasis, we created a loss-of- function mutant, ip3k2Δ1 (see Experimental Procedures) that lacks most of the ip3k2 gene, including the conserved inositol polyphosphate kinase (IPK) domain (Figures S3C and S3D). When we combined the ip3k2 and miR-14 mutants we observed a significant suppression of the miR-14 salivary gland clearance phenotype (Figures 4C and 4D). Furthermore, the ip3k2 mutation suppressed the miR-14 mutant salivary gland autophagy phenotype based on restoration of the number of mCherry-Atg8a autophagy reporter puncta (Figures 4E and 4F). Moreover, in miR-14 mutant animals, we did not observe dominant suppression of the gland clearance phenotype nor restoration of mCherry-Atg8s puncta when animals were also heterozygous for the ip3k2 mutation. In addition, the ip3k2 mutant showed no difference in the number of mCherry-Atg8a puncta in fat bodies of either fed or nutrient deprived larvae (Figures S4A and S4B). Interestingly, we observed that deletion of ip3k2 was sufficient to suppress the gland clearance phenotype observed when drosha was knocked down specifically in the salivary glands (Figures S5A and S5B). These data indicate that ip3k2 functions genetically downstream of miR-14 in the regulation of autophagy during salivary gland cell death, and that if other microRNAs regulate gland degradation, they appear to function upstream of and in the same pathway as ip3k2.

To investigate if ip3k2 3′ UTR sequences can mediate regulation by miR-14, we constructed in vivo green fluorescent protein (GFP) sensors. In these constructs, the 3′ UTR of ip3k2 was fused to GFP creating a wild type control sensor, and a similar sensor was created with mutations in the predicted miR-14 binding site (Figure S3E). Transgenic flies were generated containing either the wild type or mutant 3′ UTR constructs (Groth et al., 2004), and sensor levels were analyzed in control and miR-14 mutant salivary glands by immuno-blot. With the wild type sensor, we observed a significant elevation of GFP protein in the salivary glands of homozygous miR-14 mutant animals compared to the salivary glands of control animals (Figures 4G and 4H). Moreover, salivary gland GFP expression from the sensor containing the mutant miR-14 binding site was increased in control animals, and was identical to the GFP levels in homozygous miR-14 mutant animals (Figures 4G and 4H). These data support the conclusion that ip3k2 is a bona fide direct target of miR-14 that regulates autophagy during cell death of salivary glands.

IP3 signaling and Calmodulin are necessary for autophagy during salivary gland death

We next sought to determine how ip3k2 regulates autophagy during salivary gland death. ip3k2 contains a highly conserved IPK domain (Figure S4B) that is known to phosphorylate IP3 to form inositol 1,3,4,5-tetrakisphosphate (IP4) (Seeds et al., 2004). IP3 can serve as a cytoplasmic second messenger molecule that stimulates calcium release by binding the IP3-receptor, an ER localized calcium ion channel (Berridge et al., 2000).

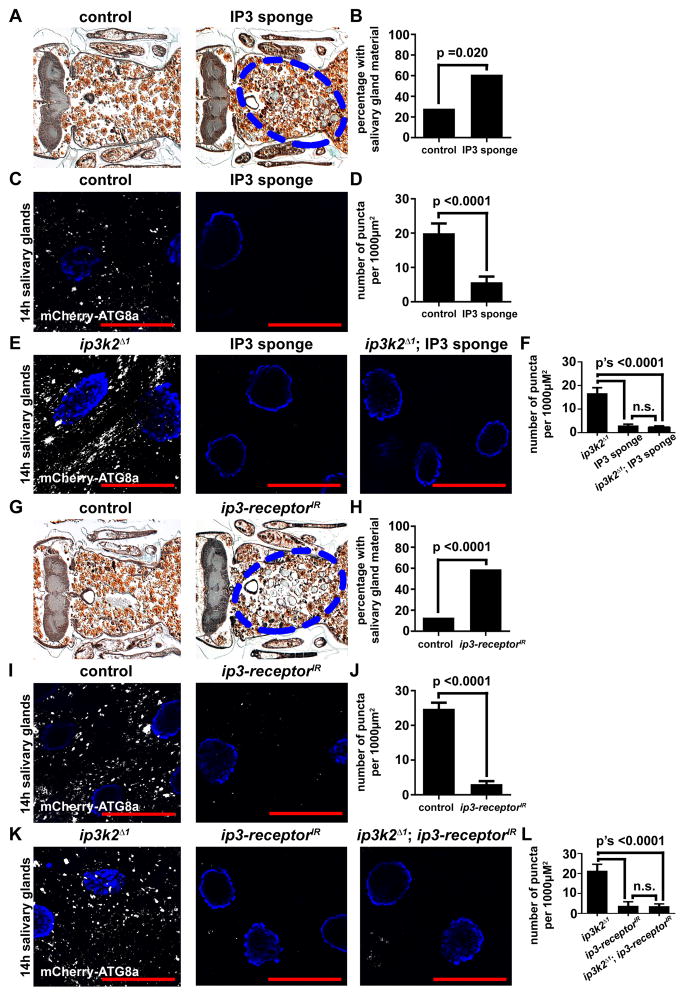

We hypothesized that in miR-14 mutant animals, IP3K2 levels are elevated resulting in low levels of IP3. To determine if IP3 signaling plays a role in salivary gland degradation, we expressed an IP3 sponge specifically in the salivary glands. This IP3 sponge contains multiple IP3 binding motifs that bind to IP3 and decrease its availability (Usui-Aoki et al., 2005). At 24 hours after puparium formation, the number of animals with persistent salivary gland cell fragments was increased in animals that expressed the IP3 sponge compared to control animals at the same stage (Figures 5A and 5B). In addition, expression of the IP3 sponge in salivary glands inhibited the induction of autophagy based on the number of mCherry-Atg8a puncta compared to controls (Figures 5C and 5D). Importantly, when the IP3 sponge was expressed in ip3k2 mutant animals, we still observed the persistence of salivary gland cell fragments (Figures S5A and S5B) and low levels of mCherry-Atg8a puncta compared to controls (Figures 5E and 5F).

Figure 5. IP3 signaling functions downstream of ip3k2 and is required for autophagy and the degradation of salivary glands.

(A) Samples from control animals (+/w; +/UAS-IP3 sponge), n = 32 (left), and those with salivary gland-specific expression of the IP3 sponge (fkh-GAL4/w; +/UAS-IP3 sponge), n = 28 (right), analyzed by histology for the presence of salivary gland material (blue dotted circle) 24 h after puparium formation.

(B) Quantification of data from (A). Data are represented as mean. Statistical significance was determined using a Chi-squared test.

(C) mCherry-Atg8a was expressed in the salivary glands of control animals (w; +/pmCherry-Atg8a; UAS-IP3 sponge/+) (left), and those with salivary gland-specific expression of the IP3 sponge (w; pmCherry-Atg8a/+; fkh-GAL4/UAS-IP3 sponge) (right). Salivary glands were dissected 14 h after puparium formation for analyses of mCherry-Atg8a puncta.

(D) Quantification of data from (C). Data are represented as mean +/− SEM; n ≥ 11. Statistical significance was determined using a Student’s t-test.

(E) mCherry-Atg8a was expressed in ip3k2 mutant animals (ip3k2 Δ1/Y; pmCherry-Atg8a/+; +/UAS-IP3 sponge), animals with salivary gland-specific expression of the IP3 sponge (ip3k2 Δ1/w; pmCherry-Atg8a/+; fkh-GAL4/UAS-IP3 sponge), and ip3k2 mutant animals with salivary gland-specific expression of the IP3 sponge (ip3k2 Δ1/Y; pmCherry-Atg8a/+; fkh-GAL4/UAS-IP3 sponge). Salivary glands were dissected 14 h after puparium formation for analyses of mCherry-Atg8a puncta.

(F) Quantification of data from (E). Data are represented as mean +/− SEM; n ≥ 14. Statistical significance was determined using a Student’s t-test.

(G) Samples from control animals (+/w; +/UAS-ip3-receptorIR), n = 15 (left), and those with salivary gland-specific knockdown of the ip3-receptor (fkh-GAL4/w; +/UAS-ip3-receptorIR), n = 27 (right), analyzed by histology for the presence of salivary gland material (blue dotted circle) 24 h after puparium formation.

(H) Quantification of data from (G). Data are represented as mean. Statistical significance was determined using a Chi-squared test.

(I) mCherry-Atg8a was expressed in the salivary glands of control animals (w; UAS-ip3-receptorIR/pmCherry-Atg8a) (left), and those with salivary gland-specific knockdown of the ip3-receptor (w; UAS-ip3-receptorIR/pmCherry-Atg8a; +/fkh-GAL4) (right). Salivary glands were dissected 14 h after puparium formation for analyses of mCherry-Atg8a puncta.

(J) Quantification of data from (I). Data are represented as mean +/− SEM; n ≥ 21. Statistical significance was determined using a Student’s t-test.

(K) mCherry-Atg8a was expressed in ip3k2 mutant animals (ip3k2 Δ1/Y; pmCherry-Atg8a/UAS-ip3-receptorIR), animals with salivary gland-specific knockdown of the ip3-receptor (ip3k2 Δ1/w; pmCherry-Atg8a/UAS-ip3-receptorIR; fkh-GAL4/+), and ip3k2 mutant animals with salivary gland-specific knockdown of the ip3-receptor (ip3k2 Δ1/Y; pmCherry-Atg8/UAS-ip3-receptorIR; fkh-GAL4/+). Salivary glands were dissected 14 h after puparium formation for analyses of mCherry-Atg8a puncta.

(L) Quantification of data from (K). Data are represented as mean +/− SEM; n ≥ 11. Statistical significance was determined using a Student’s t-test.

To complement our analyses of IP3 sponge expression, we also utilized RNAi to knock down the ip3-receptor specifically in the salivary glands. Similar to animals that express the IP3 sponge, animals with knockdown of the ip3-receptor in salivary glands possessed persistent salivary gland cell fragments (Figures 5G and 5H), and had significantly attenuated mCherry-Atg8a puncta compared to controls (Figures 5I and 5J). Furthermore, when the ip3-receptor was knocked down in ip3k2 mutant animals, we still observed the persistence of salivary gland cell fragments (Figures S5C and S5D), and reduced mCherry-Atg8a puncta relative to controls (Figures 5K and 5L). However, when either the IP3 sponge was expressed or the ip3-receptor was knocked down with RNAi in the fat body of animals following nutrient deprivation, we observed no difference in the number of mCherry-Atg8a puncta compared to control cells (Figures S4C–S4F). These data indicate that IP3 signaling through the IP3-receptor is necessary for autophagy and degradation during salivary gland cell death, but are dispensable for autophagy during nutrient deprivation of the fat body.

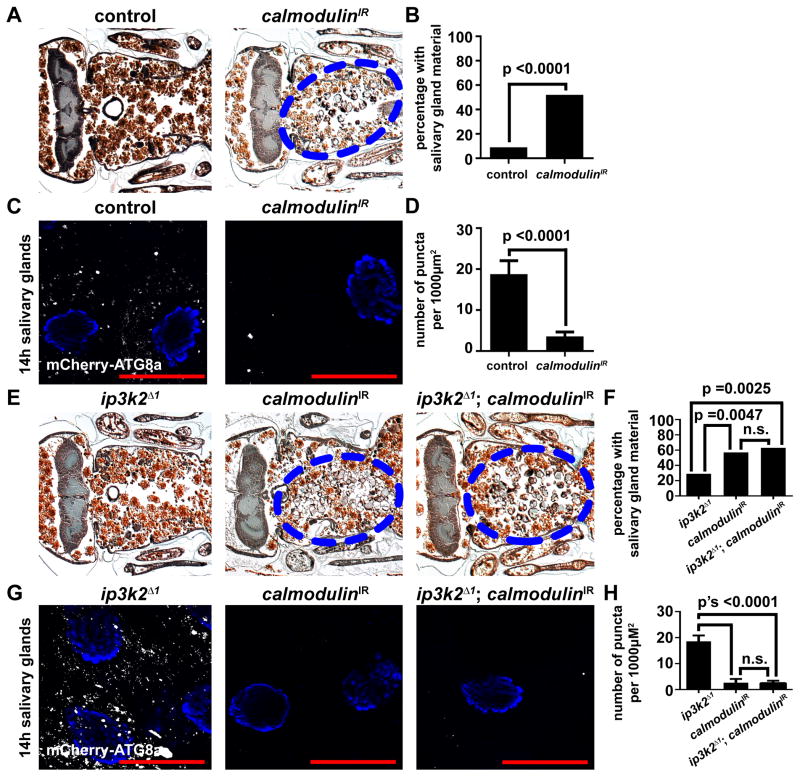

We hypothesized that IP3 regulates autophagy through calcium signaling during salivary gland cell death. To test our hypothesis, we used RNAi to decrease the function of the Calmodulin gene, which encodes a calcium-binding messenger protein. When Calmodulin was knocked down specifically in salivary glands we observed persistence of salivary gland cell fragments (Figures 6A and 6B), and decreased mCherry-Atg8a autophagy reporter puncta (Figures 6C and 6D). In addition, when Calmodulin was knocked-down specifically in the salivary glands of ip3k2 mutant animals, the salivary gland cell fragments persisted (Figures 6E and 6F) and mCherry-Atg8a puncta were attenuated (Figures 6G and 6H). However, when Calmodulin was knocked down by RNAi in the fat body of nutrient deprived larvae, we observed no difference in the number of mCherry-Atg8a puncta compared to control cells (Figures S4G and S4H) indicating that Calmodulin is dispensable for autophagy during nutrient deprivation. Combined, these data indicate that Calmodulin functions downstream of IP3K2 in the regulation of autophagy during salivary gland cell death.

Figure 6. Calmodulin functions downstream of ip3k2 and is required for autophagy and the degradation of salivary glands.

(A) Samples from control animals (+/w; +/UAS-CalmodulinIR), n = 22 (left), and those with salivary gland-specific knockdown of Calmodulin (fkh-GAL4/w; +/UAS-CalmodulinIR), n = 29 (right), analyzed by histology for the presence of salivary gland material (blue dotted circle) 24 h after puparium formation.

(B) Quantification of data from (A). Data are represented as mean. Statistical significance was determined using a Chi-squared test.

(C) mCherry-Atg8a was expressed in the salivary glands of control animals (w; pmCherry-Atg8a/+; +/UAS-CalmodulinIR) (left), and those with salivary gland-specific knockdown of Calmodulin (w; pmCherry-Atg8a/+; fkh-GAL4/UAS-CalmodulinIR) (right). Salivary glands were dissected 14 h after puparium formation for analyses of mCherry-Atg8a puncta.

(D) Quantification of data from (C). Data are represented as mean +/− SEM; n ≥ 15. Statistical significance was determined using a Student’s t-test. Salivary glands were all stained with Hoechst (blue). Scale bars represent 50 μm.

(E) Samples from ip3k2 mutant animals (ip3k2 Δ1/Y; +/UAS-CalmodulinIR), n = 21 (left), animals with salivary gland-specific knockdown of Calmodulin (ip3k2 Δ1/w; fkh-GAL4/UAS-CalmodulinIR), n = 28 (middle), and ip3k2 mutant animals with salivary gland-specific knockdown of Calmodulin (ip3k2 Δ1/Y; fkh-GAL4/UAS-CalmodulinIR), n = 24 (right), analyzed by histology for the presence of salivary gland material (blue dotted circles) 24 h after puparium formation.

(F) Quantification of data from (E). Data are represented as mean. Statistical significance was determined using a Chi-squared test.

(G) mCherry-Atg8a was expressed in ip3k2 mutant animals (ip3k2 Δ1/Y; pmCherry-Atg8a/+; +/UAS-CalmodulinIR), animals with salivary gland-specific knockdown of Calmodulin (ip3k2 Δ1/w; +/pmCherry-Atg8a; fkh-GAL4/UAS-CalmodulinIR), and ip3k2 mutant animals with salivary gland-specific knockdown of Calmodulin (ip3k2 Δ1/Y; pmCherry-Atg8a/+; fkh-GAL4/UAS-CalmodulinIR). Salivary glands were dissected 14 h after puparium formation for analyses of mCherry-Atg8a puncta.

(H) Quantification of data from (G). Data are represented as mean +/− SEM; n ≥ 10. Statistical significance was determined using a Student’s t-test. Salivary glands were all stained with Hoechst (blue). Scale bars represent 50 μm.

Next, we tested if IP3 signaling functioned downstream of miR-14 as indicated by our previous experiments. When the ip3-receptor was knocked down simultaneously with mis-expression of miR-14 in the salivary glands, we did not observe the premature increase in mCherry-Atg8a puncta characteristic of mir-14 misexpression alone (Figures S7A and S7B; compare with Figure 3G). These data indicate that knockdown of the ip3-receptor is sufficient to suppress the induction of autophagy that is triggered by mis-expression of miR-14, and functions downstream of miR-14.

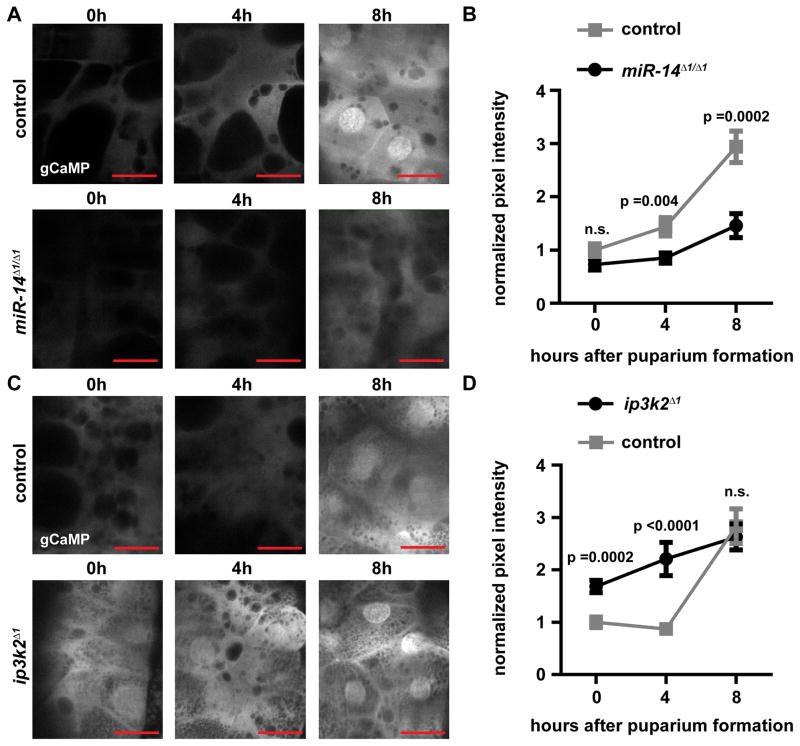

miR-14 and ip3k2 influence calcium levels in the salivary gland

We hypothesized that miR-14 regulation of ip3k2 mediates release of calcium during salivary gland destruction. Therefore, we sought to determine if miR-14 and ip3k2 influence calcium levels in the salivary gland using the calcium indicator, GCaMP (Akerboom et al., 2012). Perturbations, such as dissection of the salivary gland, resulted in a rapid release of calcium. Therefore, we live-imaged salivary glands expressing GCaMP in intact animals. In control animals, an increase in the GCaMP signal was observed at eight hours after puparium formation coinciding with the rise in ecdysone that triggers salivary gland destruction (Figure 7). In miR-14 mutant animals, the GCaMP signal was lower at all stages compared to control animals, including no marked increase at eight hours after puparium formation (Figures 7A and 7B). Additionally, ip3k2 mutant animals exhibited a significant premature elevation in the GCaMP signal compared to control animals (Figures 7C and 7D). These data indicate that release of calcium precedes salivary gland death, miR-14 is necessary for this release of calcium, and loss of ip3k2 results in premature elevation of calcium.

Figure 7. miR-14 and ip3k2 influence calcium levels in the salivary gland.

(A) GCaMP was expressed specifically in the salivary glands of control animals (w; +/miR-14Δ1; fkh-GAL4/UAS-GCaMP5) and miR-14 mutant animals (w; miR-14Δ1/miR-14Δ1; fkh-GAL4/UAS-GCaMP5), and live-imaged at 0, 4 and 8 h after puparium formation.

(B) Quantification of data from (A). Statistical significance was determined using a Student’s t-test. Error bars represent SEM; n ≥ 8. Scale bars represent 50 μm.

(C) GCaMP was expressed specifically in the salivary glands of control animals (ip3k2 Δ1/w; +/UAS-GCaMP5; +/fkh-GAL4) and ip3k2 mutant animals (ip3k2 Δ1/Y; +/UAS-GCaMP5; +/fkh-GAL4), and live-imaged at 0, 4 and 8 h after puparium formation.

(D) Quantification of data from (C). Statistical significance was determined using a Student’s t-test. Error bars represent SEM; n ≥ 10. Scale bars represent 50 μm. miR-14 and ip3k2 experiments are normalized to their respective controls.

DISCUSSION

While much is known about the regulation of autophagy during nutrient deprivation, relatively little is understood about the regulation of autophagy in the context of programmed cell death. Our findings reveal a mechanism involving the regulation of ip3k2 by the microRNA miR-14. In turn, these factors influence IP3 signaling and Calmodulin as a mechanism that distinguishes between the utilization of autophagy during programmed cell death from the use of autophagy in the context of cellular stress.

Previous studies have linked microRNAs and autophagy. For example, autophagy can modulate the intracellular levels of microRNAs by degradation of core microRNA machinery (Gibbings et al., 2012; Zhang and Zhang, 2013). In addition, multiple studies have shown that over-expression of microRNAs can be sufficient to inhibit autophagy in cell lines under starvation conditions (Frankel et al., 2011; Zhu et al., 2009). By contrast, our findings demonstrate that the microRNA, miR-14, is both necessary and sufficient for autophagy during developmental cell death in an animal, but that miR-14 has no apparent effect on autophagy triggered by nutrient deprivation. While miR-14 is expressed in the fat body (Varghese et al., 2010), it appears not to matter if miR-14 regulates ip3k2 in this tissue, as IP3 signaling and Calmodulin appear to play no detectable role in regulating autophagy during nutrient deprivation.

Interestingly, steroid signaling and caspase activity are both necessary for salivary gland cell death, and in other contexts, these two processes have been shown to be regulated by miR-14 (Varghese and Cohen, 2009; Varghese et al., 2010; Xu et al., 2003). However, during salivary gland cell death, neither of these processes was affected by loss of miR-14. This new role of miR-14 in promoting organ-specific developmental autophagy underscores the context-specific roles that microRNAs can play.

Our findings show that miR-14 controls this context-specific autophagy in dying salivary gland cells by targeting the IP3-kinase ip3k2. Although the percentage of animals with a defect in salivary gland clearance appears less severe in animals with compromised IP3/calcium signaling compared to miR-14 mutant animals, this is most likely due to RNAi knockdown and IP3 sponge expression efficiencies. In addition, in all histological analyses of salivary gland clearance, there is an inherent range of salivary gland material appearance and size. For example, cellular fragments are detached from each other and therefore fluid. Thus, two dimensional histological sections do not always convey the best representation of salivary gland material in an animal.

To the best of our knowledge, no IP3-kinase has previously been implicated in the control of autophagy. Our data indicate that ip3k2 regulates autophagy through IP3 signaling, by inducing the release of calcium, thereby affecting Calmodulin activity. Our findings imply that calcium-bound Calmodulin activity should result in the induction of autophagy, potentially through the modulation of proteins such as Calmodulin-dependent kinases and/or Atg proteins. A previous study demonstrated that Calmodulin can bind IP3K2 in vitro, and that this calcium-dependent binding decreased the ability of IP3K2 to remove IP3 (Lloyd-Burton et al., 2007). It is possible that calcium released by IP3 signaling could activate Calmodulin, resulting in a positive feedback loop to inhibit IP3K2, releasing more calcium to activate Calmodulin further, and induce higher levels of autophagy that contribute to salivary gland cell death.

Interestingly, ip3k1 is also a predicted target of miR-14, but we observed no influence of this gene on autophagy in the salivary gland using two independent RNAi lines that target distinct sequences (Table S2) (Terhzaz et al., 2010). Additionally, heterozygous loss of ip3k1 failed to suppress the miR-14 salivary gland clearance defect (data not shown), suggesting that ip3k1 is not involved in the regulation of autophagy during salivary gland death. Furthermore, a previous study demonstrated that Calmodulin cannot bind IP3K1 in vitro (Lloyd-Burton et al., 2007), and it may be this lack of interaction that ensures that IP3K1 does not regulate autophagy during salivary gland destruction.

While multiple studies have linked calcium signaling to autophagy (Decuypere et al., 2011), the manner, either positive or negative, in which calcium influences autophagy seems to depend on context. Since it has been shown that a rise in free Ca2+ can induce autophagy via mTOR inhibition (Høyer-Hansen et al., 2007), it is possible that the mTOR pathway could contribute to the effect of miR-14 on autophagy induction. However, we have previously shown that that modulation of mTOR pathway influences both cell size and tGPH reporter localization (Berry and Baehrecke, 2007). Since neither cell size nor tGPH reporter were affected in mir-14 mutant salivary glands (Figure 2A and 2B), it appears unlikely that mTOR activity is appreciably altered by loss of mir-14.

Finally, we cannot exclude that ip3k2 could also regulate autophagy in an IP3- and/or calcium-independent manner. For example, the mammalian Beclin1 (Atg6) complex has been shown to bind the ER localized IP3-receptor through the protein NAF-1 (Chang et al., 2010). Therefore, it is possible that IP3 signaling may serve as a mechanism to relocate the Beclin1 complex to the ER so that the ER can function as a membrane source for autophagosomes. Additionally, calcium signaling may cooperate with localization of the Beclin1 complex to the ER to achieve complete induction of autophagy during salivary gland cell death. Future studies should resolve how miR-14 and its target, the novel autophagy factor ip3k2, and IP3 signaling regulate autophagy.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Drosophila strains

ip3k2Δ1 mutant

The ip3k2Δ1 deletion allele was created by flippase mediated site specific recombination of two transposable p-element strains containing flippase recognition target sequences. For more details see supplemental experimental procedures.

Transgenic strains

To generate the tub-eGFP-ip3k2 wild type 3′UTR vector, the 3′UTR of ip3k2 was PCR amplified from genomic DNA. The miR-14 binding site was mutated via de novo gene synthesis (Biomatik). Construct sequences were validated and inserted into the attP2 landing site to generate transgenic Drosophila lines (Genetic Services, Inc). For more details see supplemental experimental procedures.

Quantitative real-time PCR

RNA isolated from staged salivary glands was performed as described previously (Andres and Thummel, 1994). Five μL of a 0.5ng/μL RNA sample was used for multiplex miR-Taqman reactions according to the manufacturer’s instruction, using an ABI 7900HT Real Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems).

Protein Extracts and Western Blotting

Protein extraction and Western Blotting were performed as described previously (Dutta and Baehrecke, 2008). Primary antibodies used were rabbit anti-GFP (1:1,000) (Novus Biologicals), chicken anti-GFP (1:20,000) (Abcam), mouse anti-Ecdysone Receptor (1:500) (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank), mouse anti-Broad Complex (1:100) (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank), Rabbit anti-Histone-H3 (1:2000) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and mouse anti-Beta-Tubulin (1:500) (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank). Western blots were imaged using a Bio-Rad Chemi-Doc XRS+ and quantified using Bio-Rad Image Lab software.

Histology

Histology was performed as described previously (Muro et al., 2006).

Immunolabeling and Microscopy

For immunohistochemisty, salivary glands were dissected from animals kept at 25°C, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) overnight at 4°C, blocked in PBS, 1% BSA and 0.1% tween (PBSBT), and incubated with rabbit anti-cleaved-Caspase-3 (1:400) (Cell Signaling Technology) overnight at 4°C. Salivary glands were washed for two hours at room temperature in PBSBT, incubated with appropriate secondary antibodies for two hours at room temperature, and washed for one hour in PBSBT. Salivary glands were mounted in Vectashield (Vector Laboratories). For mCherry-Atg8a, tGPH and cell size analyses, salivary glands were dissected from animals staged at 25°C, fixed in 2% PFA containing 2μM Hoechst stain for two minutes at room temperature, washed in PBS, and mounted in PBS. Cell size was measured using Zeiss measure software. mCherry-Atg8a puncta were quantified using Zeiss Automeasure software. Pixel intensity was measured using ImageJ software. All imaging except GCaMP was performed on a Zeiss Axiophot II microscope. GCaMP imaging was performed on a Zeiss two-photon microscope, LSM 7 MP. During all quantifications, the images that were used were unaltered. In all mCherry-Atg8a and cleaved-Caspase-3 figures, the brightness, contrast, and gamma were altered separately from the DNA to better emphasize puncta.

Induction of cell clones

The induction of mis-expression and RNAi-expressing cell clones was performed as described previously (McPhee et al., 2010).

Starvation of larvae

Starvation of larvae was performed as described previously (McPhee et al., 2010).

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. A description of salivary gland degradation during development, cellular and gland fragments, dicer-1 is required for salivary gland degradation, and drosha functions in the same pathway as miR-14. Related to Figure 1

(A) A histological section (left) of a wild type animal 6 h after puparium formation approximately 8–10 hours before complete gland degradation. The left side of all images is the anterior end of the animal. The image on the right shows emphasized salivary glands with all other material removed.

(B) A histological section (left) of a wild type animal 12 h after puparium formation approximately 2–4 hours before complete gland degradation. The image on the right shows emphasized salivary glands with all other material removed.

(C) A histological section (left) 24 h after puparium formation of an animal that partially, but not completely, degraded its salivary glands thereby displaying a cellular fragment phenotype (fkh-GAL4/w; +/UAS-droshaIR). Labeled are the head (left part of the animal), thorax (middle part of the animal), abdomen (right part of the animal), the brain (blue stained tissue), fat body cells (brown and red stained cells), and developing legs. The image on the right shows the cellular fragments with all other material removed. Note these cellular fragments have remained 10 h after they should have been degraded.

(D) A histological section (left) 24 h after puparium formation of an animal failed to degrade its salivary glands thereby displaying a salivary gland fragment phenotype (w; miR-14Δ1/miR-14Δ1; UAS-p35/fkh-GAL4). The image on the right shows the gland fragments with all other material removed. Note these gland fragments have remained 10 h after they should have been degraded.

(E) Samples from control animals (+/w; +/UAS-dicer-1IR), n = 27 (left), and those with salivary gland-specific knockdown of dicer-1 (fkh-GAL4/w; +/UAS-dicer-1IR), n = 28 (right), analyzed by histology for the presence of salivary gland material (blue dotted circle) 24 h after puparium formation.

F) Quantification of data from (E). Data are represented as mean. Statistical significance was determined using a Chi-squared test.

(G) Samples from miR-14 mutant animals (w; miR-14Δ1/miR-14Δ1;+/UAS-droshaIR), n = (left), animals with salivary gland-specific knockdown of drosha (w; +/miR-14Δ1; fkh-GAL4/UAS-droshaIR), n = 23 (middle), and miR-14 mutant animals with salivary gland-specific knockdown of drosha (w; miR-14Δ1/miR-14Δ1; fkh-GAL4/UAS-droshaIR), n= 20, analyzed by histology for the presence of salivary gland material (blue dotted circle) 24 h after puparium formation.

(H) Quantification of data from (G). Data are represented as mean. Statistical significance was determined using a Chi-squared test.

Figure S2. Mis-expression of miR-14 is sufficient to induce autophagy in the salivary gland, but not in the fat body. Related to Figure 3

(A and B) Salivary glands dissected from wandering larvae (A) and fat bodies dissected from feeding larvae (B) expressing mCherry-Atg8a in all cells, and miR-14 mis-expression specifically in GFP-marked clone cells (hsflp/w; pmCherry-Atg8a/+; act<FRT, cd2, FRT>Gal4, UAS-GFP/UAS-luciferase-miR-14) analyzed for mCherry-Atga8a puncta. Salivary glands and fat bodies were all stained with Hoechst (blue). Scale bars represent 50μm.

Figure S3. ip3k2 RNAi is sufficient to induce autophagy in the salivary gland, ip3k2 deletion mutant, the conserved IPK domain of IP3K2, and the predicted miR-14 binding site in ip3k2. Related to Figure 4

(A and B) Salivary glands (A) and fat bodies (B) expressing mCherry-Atg8a in all cells, and ip3k2IR knockdown specifically in GFP-marked clone cells (hsflp/w; pmCherry-Atg8a/+; act<FRT, cd2, FRT>Gal4, UAS-GFP/UAS-ip3k2IR) dissected from feeding larvae for analyses of mCherry-Atg8a puncta. Salivary glands and fat bodies were all stained with Hoechst (blue). Scale bars represent 50μm.

(C) The two flippase recognition target (FRT) containing elements, PBac{RB}IP3K2e02492 and P{RS3}CB-0529-3 were recombined together to create the ip3k2Δ1 allele containing a 10,540bp genomic deletion that deletes isoforms A and B, and most of isoforms C through H including the IPK domain of all isoforms.

(D) Alignment of the highly conserved IPK domain. The C. elegans protein is lfe-1. The D. melanogaster protein is IP3K2. The M. musculus and H. sapiens proteins are both ITPKA.

(E) The miR-14 binding site in the 3′ UTR of ip3k2. The nucleotides replaced in the mutated sensor line are indicated with *, and the new nucleotides are shown above.

Figure S4. The ip3k2 mutant, IP3 sponge, ip3-receptor and Calmodulin knockdowns are not sufficient to alter stress induced autophagy in the fat body. Related to Figure 4

(A) mCherry-Atg8a was expressed in the fat bodies of control animals (left) (w/ip3k2Δ1; +/pmCherry-Atg8a) and in ip3k2Δ1 mutant animals (right) (ip3k2Δ1/Y; +/pmCherry-Atg8a). Animals were either fed (top) or starved for 4 h (bottom), and fat bodies were dissected for analyses of mCherry-Atg8a puncta.

(B) Quantification of data from (A). Data are represented as mean +/− SEM; n ≥ 10. Statistical significance was determined using a Student’s t-test.

(C) Fat bodies expressing mCherry-Atg8a in all cells, and the IP3 sponge specifically in GFP-marked clone cells (hsflp/w; pmCherry-Atg8a/+; act<FRT, cd2, FRT>Gal4, UAS-GFP/UAS-IP3 sponge) dissected from 4 h starved larvae for analyses of mCherry-Atg8a puncta.

(D) Quantification of data from (C). Data are represented as mean +/− SEM; n = 8. Statistical significance was determined using a Student’s t-test.

(E) Fat bodies expressing mCherry-Atg8a in all cells, and knockdown of the ip3-receptor specifically in GFP-marked clone cells (hsflp/w; pmCherry-Atg8a/UAS-ip3-receptorIR; act<FRT, cd2, FRT>Gal4, UAS-GFP/+) dissected from 4 h starved larvae for analyses of mCherry-Atg8a puncta.

(F) Quantification of data from (E). Data are represented as mean +/− SEM; n = 7. Statistical significance was determined using a Student’s t-test.

(G) Fat bodies expressing mCherry-Atg8a in all cells, and knockdown of Calmodulin specifically in GFP-marked clone cells (hsflp/w; pmCherry-Atg8a/+; act<FRT, cd2, FRT>Gal4, UAS-GFP/UAS-CalmodulinIR) dissected from 4 h starved larvae for analyses of mCherry-Atg8a puncta.

(H) Quantification of data from (G). Data are represented as mean +/− SEM; n = 8. Statistical significance was determined using a Student’s t-test.

Figure S5. ip3k2 functions genetically downstream of drosha. Related to Figure 4

(A) Samples from ip3k2 mutant animals (ip3k2Δ1/Y; +/UAS-droshaIR), n = 24 (left), animals with salivary gland-specific knockdown of drosha (ip3k2Δ1/+; fkh-GAL4/UAS-droshaIR), n = 20 (middle), and ip3k2 mutant animals with salivary gland-specific knockdown of drosha (ip3k2Δ1/Y; fkh-GAL4/UAS-droshaIR), n = 21, analyzed by histology for the presence of salivary gland material (blue dotted circle) 24 h after puparium formation.

(B) Quantification of data from (A). Data are represented as mean. Statistical significance was determined using a Chi-squared test.

Figure S6. IP3 signaling is required for salivary gland degradation and function downstream of ip3k2. Related to Figure 5

(A) Samples from ip3k2 mutant animals (ip3k2 Δ1/Y; +/UAS-IP3 sponge), n = 22 (left), animals with salivary gland-specific expression of the IP3 sponge (ip3k2 Δ1/w; fkh-GAL4/UAS-IP3 sponge), n = 16 (middle), and ip3k2 mutant animals with salivary gland-specific expression of the IP3 sponge (ip3k2 Δ1/Y; fkh-GAL4/UAS-IP3 sponge), n = 20 (right), analyzed by histology for the presence of salivary gland material (blue dotted circles) 24 h after puparium formation.

(B) Quantification of data from (A). Data are represented as mean. Statistical significance was determined using a Chi-squared test.

(C) Samples from ip3k2 mutant animals (ip3k2 Δ1/Y; +/UAS-ip3-receptorIR), n = 16 (left), animals with salivary gland-specific knockdown of the ip3-receptor (ip3k2 Δ1/w; +/UAS-ip3-receptorIR; fkh-GAL4/+), n = 27 (middle), and ip3k2 mutant animals with salivary gland-specific knockdown of the ip3-receptor (ip3k2 Δ1/Y; +/UAS-ip3-receptorIR; fkh-GAL4/+), n = 22 (right), analyzed by histology for the presence of salivary gland material (blue dotted circles) 24 h after puparium formation.

(D) Quantification of data from (C). Data are represented as mean. Statistical significance was determined using a Chi-squared test.

Figure S7. Knockdown of the ip3-receptor in the salivary gland is sufficient to suppress the induction of autophagy by miR-14 mis-expression. Related to Figures 3 and 5

(A) A salivary gland expressing mCherry-Atg8a in all cells, and knockdown of the ip3-receptor as well as mis-expression of miR-14 specifically in GFP-marked clone cells (hsflp/w; pmCherry-Atg8a/UAS-ip3-receptorIR; act<FRT, cd2, FRT>Gal4, UAS-GFP/UAS-luc-miR-14) dissected from wandering larvae for analyses of mCherry-Atg8a puncta.

(B) Quantification of data from Figure S2A (first two columns) and (A) (last two columns). Data are represented as mean +/− SEM; n ≥ 9. Statistical significance was determined using a Student’s t-test.

Table S1. microRNA levels in the salivary gland during cell death. Related to Figure 1

Table S2. List of RNAi lines screened to identify targets of miR-14. Related to Figure 4

HIGHLIGHTS.

miR-14 is necessary and sufficient for autophagy during cell death

miR-14 targets the inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate kinase 2 gene to regulate autophagy

IP3 signaling and Calmodulin are necessary for autophagy during cell death

miR-14 regulates calcium levels during salivary gland destruction

Acknowledgments

We thank R. Carthew, S. Cohen, F.-B. Gao, B. Hay, L. Johnston, E. Lai, N. Sokol, P. Zamore, L. Zipursky, the Bloomington Stock Center, the Drosophila Genetic Resource Center, and the VDRC for flies and reagents, and S. Gupta, T. Fortier and R. Lee for technical support. This work was supported by NIH grants R01GM34028 to V.A. and GM079431 and GM079431-04S1 to E.H.B. V.A. and E.H.B. are Ellison Medical Foundation Scholars, and are members of the UMass DERC (DK32520).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Akerboom J, Chen TW, Wardill TJ, Tian L, Marvin JS, Mutlu S, Calderón NC, Esposti F, Borghuis BG, Sun XR, et al. Optimization of a GCaMP calcium indicator for neural activity imaging. J Neurosci. 2012;32:13819–13840. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2601-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambros V. MicroRNAs and developmental timing. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2011;21:511–517. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2011.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andres AJ, Thummel CS. In: Methods for quantitative analysis of transcription in larvae and prepupaeDrosophila melanogaster: Practical Uses in Cell and Molecular Biology. Goldstein L, Fyrberg E, editors. New York: Academic Press; 1994. pp. 565–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berridge MJ, Lipp P, Bootman MD. The versatility and universality of calcium signalling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2000;1:11–21. doi: 10.1038/35036035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry DL, Baehrecke EH. Growth arrest and autophagy are required for salivary gland cell degradation in Drosophila. Cell. 2007;131:1137–1148. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennecke J, Hipfner DR, Stark A, Russell RB, Cohen SM. bantam encodes a developmentally regulated microRNA that controls cell proliferation and regulates the proapoptotic gene hid in Drosophila. Cell. 2003;113:25–36. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00231-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britton JS, Lockwood WK, Li L, Cohen SM, Edgar BA. Drosophila’s insulin/PI3-kinase pathway coordinates cellular metabolism with nutritional conditions. Dev Cell. 2002;2:239–249. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00117-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caygill EE, Johnston LA. Temporal regulation of metamorphic processes in Drosophila by the let-7 and miR-125 heterochronic microRNAs. Curr Biol. 2008;18:943–950. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cayirlioglu P, Kadow IG, Zhan X, Okamura K, Suh GS, Gunning D, Lai EC, Zipursky SL. Hybrid neurons in a microRNA mutant are putative evolutionary intermediates in insect CO2 sensory systems. Science. 2008;319:1256–1260. doi: 10.1126/science.1149483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang NC, Nguyen M, Germain M, Shore GC. Antagonism of Beclin 1-dependent autophagy by BCL-2 at the endoplasmic reticulum requires NAF-1. EMBO J. 2010;29:606–618. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang TK, Shravage BV, Hayes SD, Powers CM, Simin RT, Harper JW, Baehrecke EH. Uba1 functions in Atg7- and Atg3-independent autophagy. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15:1067–1078. doi: 10.1038/ncb2804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decuypere JP, Bultynck G, Parys JB. A dual role for Ca(2+) in autophagy regulation. Cell Calcium. 2011;50:242–250. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2011.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denton D, Chang TK, Nicolson S, Shravage B, Simin R, Baehrecke EH, Kumar S. Relationship between growth arrest and autophagy in midgut programmed cell death in Drosophila. Cell Death Differ. 2012;19:1299–1307. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2012.43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta S, Baehrecke EH. Warts is required for PI3K-regulated growth arrest, autophagy, and autophagic cell death in Drosophila. Curr Biol. 2008;18:1466–1475. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.08.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankel LB, Wen J, Lees M, Høyer-Hansen M, Farkas T, Krogh A, Jäättelä M, Lund AH. microRNA-101 is a potent inhibitor of autophagy. EMBO J. 2011;30:4628–4641. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauhar Z, Sun LV, Hua S, Mason CE, Fuchs F, Li TR, Boutros M, White KP. Genomic mapping of binding regions for the Ecdysone receptor protein complex. Genome Res. 2009;19:1006–1013. doi: 10.1101/gr.081349.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbings D, Mostowy S, Jay F, Schwab Y, Cossart P, Voinnet O. Selective autophagy degrades DICER and AGO2 and regulates miRNA activity. Nat Cell Biol. 2012;14:1314–1321. doi: 10.1038/ncb2611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groth AC, Fish M, Nusse R, Calos MP. Construction of transgenic Drosophila by using the site-specific integrase from phage phiC31. Genetics. 2004;166:1775–1782. doi: 10.1534/genetics.166.4.1775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay BA, Wolff T, Rubin GM. Expression of baculovirus P35 prevents cell death in Drosophila. Development. 1994;120:2121–2129. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.8.2121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Høyer-Hansen M, Bastholm L, Szyniarowski P, Campanella M, Szabadkai G, Farkas T, Bianchi K, Fehrenbacher N, Elling F, Rizzuto R, et al. Control of macroautophagy by calcium, calmodulin-dependent kinase kinase-beta, and Bcl-2. Mol Cell. 2007;25:193–205. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang C, Baehrecke EH, Thummel CS. Steroid regulated programmed cell death during Drosophila metamorphosis. Development. 1997;124:4673–4683. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.22.4673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karres JS, Hilgers V, Carrera I, Treisman J, Cohen SM. The conserved microRNA miR-8 tunes atrophin levels to prevent neurodegeneration in Drosophila. Cell. 2007;131:136–145. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CY, Baehrecke EH. Steroid regulation of autophagic programmed cell death during development. Development. 2001;128:1443–1455. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.8.1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Carthew RW. A microRNA mediates EGF receptor signaling and promotes photoreceptor differentiation in the Drosophila eye. Cell. 2005;123:1267–1277. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Wang F, Lee JA, Gao FB. MicroRNA-9a ensures the precise specification of sensory organ precursors in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 2006;20:2793–2805. doi: 10.1101/gad.1466306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd-Burton SM, Yu JC, Irvine RF, Schell MJ. Regulation of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate 3-kinases by calcium and localization in cells. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:9526–9535. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M610253200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin DN, Baehrecke EH. Caspases function in autophagic cell death in Drosophila. Development. 2004;131:275–284. doi: 10.1242/dev.00933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPhee CK, Logan MA, Freeman MR, EHB Activation of autophagy during cell death requires the engulfment receptor Draper. Nature. 2010;465:1093–1096. doi: 10.1038/nature09127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizushima N, Komatsu M. Autophagy: Renovation of Cells and Tissues Cell. 2011;147:728–741. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muro I, Berry DL, Huh JR, Chen CH, Huang H, Yoo SJ, Guo M, Baehrecke EH, Hay BA. The Drosophila caspase Ice is important for many apoptotic cell deaths and for spermatid individualization, a nonapoptotic process. Development. 2006;133:3305–3315. doi: 10.1242/dev.02495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeds AM, Sandquist JC, Spana EP, York JD. A molecular basis for inositol polyphosphate synthesis in Drosophila melanogaster. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:47222–47232. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408295200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokol NS. Small temporal RNAs in animal development. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2012;22:368–373. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2012.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokol NS, Xu P, Jan YN, Ambros V. Drosophila let-7 microRNA is required for remodeling of the neuromusculature during metamorphosis. Genes Dev. 2008;22:1591–1596. doi: 10.1101/gad.1671708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teleman AA, Maitra S, Cohen SM. Drosophila lacking microRNA miR-278 are defective in energy homeostasis. Genes Dev. 2006;20:417–422. doi: 10.1101/gad.374406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terhzaz S, Finlayson AJ, Stirrat L, Yang J, Tricoire H, Woods DJ, Dow JA, Davies SA. Cell-specific inositol 1,4,5 trisphosphate 3-kinase mediates epithelial cell apoptosis in response to oxidative stress in Drosophila. Cell Signal. 2010;22:737–748. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2009.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usui-Aoki K, Matsumoto K, Koganezawa M, Kohatsu S, Isono K, Matsubayashi H, Yamamoto MT, Ueda R, Takahashi K, Saigo K, et al. Targeted expression of Ip3 sponge and Ip3 dsRNA impaires sugar taste sensation in Drosophila. J Neurogenet. 2005;19:123–141. doi: 10.1080/01677060600569713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varghese J, Cohen SM. microRNA miR-14 acts to modulate a positive autoregulatory loop controlling steroid hormone signaling in Drosophila. Genes Dev. 2009;21:2277–2282. doi: 10.1101/gad.439807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varghese J, Lim SF, Cohen SM. Drosophila miR-14 regulates insulin production and metabolism through its target, sugarbabe. Genes Dev. 2010;24:2748–2753. doi: 10.1101/gad.1995910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu P, Vernooy SY, Guo M, Hay BA. The Drosophila microRNA mir-14 suppresses cell death and is required for normal fat metabolism. Curr Biol. 2003;13:790–795. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00250-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang P, Zhang H. Autophagy modulates miRNA-mediated gene silencing and selectively degrades AIN-1/GW182 in C. elegans. EMBO Rep. 2013;14:568–576. doi: 10.1038/embor.2013.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu H, Wu H, Liu X, Li B, Chen Y, Ren X, Liu CG, Yang JM. Regulation of autophagy by a beclin 1-targeted microRNA, miR-30a, in cancer cells. Autophagy. 2009;5:816–823. doi: 10.4161/auto.9064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. A description of salivary gland degradation during development, cellular and gland fragments, dicer-1 is required for salivary gland degradation, and drosha functions in the same pathway as miR-14. Related to Figure 1

(A) A histological section (left) of a wild type animal 6 h after puparium formation approximately 8–10 hours before complete gland degradation. The left side of all images is the anterior end of the animal. The image on the right shows emphasized salivary glands with all other material removed.

(B) A histological section (left) of a wild type animal 12 h after puparium formation approximately 2–4 hours before complete gland degradation. The image on the right shows emphasized salivary glands with all other material removed.

(C) A histological section (left) 24 h after puparium formation of an animal that partially, but not completely, degraded its salivary glands thereby displaying a cellular fragment phenotype (fkh-GAL4/w; +/UAS-droshaIR). Labeled are the head (left part of the animal), thorax (middle part of the animal), abdomen (right part of the animal), the brain (blue stained tissue), fat body cells (brown and red stained cells), and developing legs. The image on the right shows the cellular fragments with all other material removed. Note these cellular fragments have remained 10 h after they should have been degraded.

(D) A histological section (left) 24 h after puparium formation of an animal failed to degrade its salivary glands thereby displaying a salivary gland fragment phenotype (w; miR-14Δ1/miR-14Δ1; UAS-p35/fkh-GAL4). The image on the right shows the gland fragments with all other material removed. Note these gland fragments have remained 10 h after they should have been degraded.

(E) Samples from control animals (+/w; +/UAS-dicer-1IR), n = 27 (left), and those with salivary gland-specific knockdown of dicer-1 (fkh-GAL4/w; +/UAS-dicer-1IR), n = 28 (right), analyzed by histology for the presence of salivary gland material (blue dotted circle) 24 h after puparium formation.

F) Quantification of data from (E). Data are represented as mean. Statistical significance was determined using a Chi-squared test.

(G) Samples from miR-14 mutant animals (w; miR-14Δ1/miR-14Δ1;+/UAS-droshaIR), n = (left), animals with salivary gland-specific knockdown of drosha (w; +/miR-14Δ1; fkh-GAL4/UAS-droshaIR), n = 23 (middle), and miR-14 mutant animals with salivary gland-specific knockdown of drosha (w; miR-14Δ1/miR-14Δ1; fkh-GAL4/UAS-droshaIR), n= 20, analyzed by histology for the presence of salivary gland material (blue dotted circle) 24 h after puparium formation.

(H) Quantification of data from (G). Data are represented as mean. Statistical significance was determined using a Chi-squared test.

Figure S2. Mis-expression of miR-14 is sufficient to induce autophagy in the salivary gland, but not in the fat body. Related to Figure 3

(A and B) Salivary glands dissected from wandering larvae (A) and fat bodies dissected from feeding larvae (B) expressing mCherry-Atg8a in all cells, and miR-14 mis-expression specifically in GFP-marked clone cells (hsflp/w; pmCherry-Atg8a/+; act<FRT, cd2, FRT>Gal4, UAS-GFP/UAS-luciferase-miR-14) analyzed for mCherry-Atga8a puncta. Salivary glands and fat bodies were all stained with Hoechst (blue). Scale bars represent 50μm.

Figure S3. ip3k2 RNAi is sufficient to induce autophagy in the salivary gland, ip3k2 deletion mutant, the conserved IPK domain of IP3K2, and the predicted miR-14 binding site in ip3k2. Related to Figure 4

(A and B) Salivary glands (A) and fat bodies (B) expressing mCherry-Atg8a in all cells, and ip3k2IR knockdown specifically in GFP-marked clone cells (hsflp/w; pmCherry-Atg8a/+; act<FRT, cd2, FRT>Gal4, UAS-GFP/UAS-ip3k2IR) dissected from feeding larvae for analyses of mCherry-Atg8a puncta. Salivary glands and fat bodies were all stained with Hoechst (blue). Scale bars represent 50μm.

(C) The two flippase recognition target (FRT) containing elements, PBac{RB}IP3K2e02492 and P{RS3}CB-0529-3 were recombined together to create the ip3k2Δ1 allele containing a 10,540bp genomic deletion that deletes isoforms A and B, and most of isoforms C through H including the IPK domain of all isoforms.

(D) Alignment of the highly conserved IPK domain. The C. elegans protein is lfe-1. The D. melanogaster protein is IP3K2. The M. musculus and H. sapiens proteins are both ITPKA.

(E) The miR-14 binding site in the 3′ UTR of ip3k2. The nucleotides replaced in the mutated sensor line are indicated with *, and the new nucleotides are shown above.

Figure S4. The ip3k2 mutant, IP3 sponge, ip3-receptor and Calmodulin knockdowns are not sufficient to alter stress induced autophagy in the fat body. Related to Figure 4

(A) mCherry-Atg8a was expressed in the fat bodies of control animals (left) (w/ip3k2Δ1; +/pmCherry-Atg8a) and in ip3k2Δ1 mutant animals (right) (ip3k2Δ1/Y; +/pmCherry-Atg8a). Animals were either fed (top) or starved for 4 h (bottom), and fat bodies were dissected for analyses of mCherry-Atg8a puncta.

(B) Quantification of data from (A). Data are represented as mean +/− SEM; n ≥ 10. Statistical significance was determined using a Student’s t-test.

(C) Fat bodies expressing mCherry-Atg8a in all cells, and the IP3 sponge specifically in GFP-marked clone cells (hsflp/w; pmCherry-Atg8a/+; act<FRT, cd2, FRT>Gal4, UAS-GFP/UAS-IP3 sponge) dissected from 4 h starved larvae for analyses of mCherry-Atg8a puncta.

(D) Quantification of data from (C). Data are represented as mean +/− SEM; n = 8. Statistical significance was determined using a Student’s t-test.

(E) Fat bodies expressing mCherry-Atg8a in all cells, and knockdown of the ip3-receptor specifically in GFP-marked clone cells (hsflp/w; pmCherry-Atg8a/UAS-ip3-receptorIR; act<FRT, cd2, FRT>Gal4, UAS-GFP/+) dissected from 4 h starved larvae for analyses of mCherry-Atg8a puncta.

(F) Quantification of data from (E). Data are represented as mean +/− SEM; n = 7. Statistical significance was determined using a Student’s t-test.

(G) Fat bodies expressing mCherry-Atg8a in all cells, and knockdown of Calmodulin specifically in GFP-marked clone cells (hsflp/w; pmCherry-Atg8a/+; act<FRT, cd2, FRT>Gal4, UAS-GFP/UAS-CalmodulinIR) dissected from 4 h starved larvae for analyses of mCherry-Atg8a puncta.

(H) Quantification of data from (G). Data are represented as mean +/− SEM; n = 8. Statistical significance was determined using a Student’s t-test.

Figure S5. ip3k2 functions genetically downstream of drosha. Related to Figure 4

(A) Samples from ip3k2 mutant animals (ip3k2Δ1/Y; +/UAS-droshaIR), n = 24 (left), animals with salivary gland-specific knockdown of drosha (ip3k2Δ1/+; fkh-GAL4/UAS-droshaIR), n = 20 (middle), and ip3k2 mutant animals with salivary gland-specific knockdown of drosha (ip3k2Δ1/Y; fkh-GAL4/UAS-droshaIR), n = 21, analyzed by histology for the presence of salivary gland material (blue dotted circle) 24 h after puparium formation.

(B) Quantification of data from (A). Data are represented as mean. Statistical significance was determined using a Chi-squared test.

Figure S6. IP3 signaling is required for salivary gland degradation and function downstream of ip3k2. Related to Figure 5

(A) Samples from ip3k2 mutant animals (ip3k2 Δ1/Y; +/UAS-IP3 sponge), n = 22 (left), animals with salivary gland-specific expression of the IP3 sponge (ip3k2 Δ1/w; fkh-GAL4/UAS-IP3 sponge), n = 16 (middle), and ip3k2 mutant animals with salivary gland-specific expression of the IP3 sponge (ip3k2 Δ1/Y; fkh-GAL4/UAS-IP3 sponge), n = 20 (right), analyzed by histology for the presence of salivary gland material (blue dotted circles) 24 h after puparium formation.

(B) Quantification of data from (A). Data are represented as mean. Statistical significance was determined using a Chi-squared test.

(C) Samples from ip3k2 mutant animals (ip3k2 Δ1/Y; +/UAS-ip3-receptorIR), n = 16 (left), animals with salivary gland-specific knockdown of the ip3-receptor (ip3k2 Δ1/w; +/UAS-ip3-receptorIR; fkh-GAL4/+), n = 27 (middle), and ip3k2 mutant animals with salivary gland-specific knockdown of the ip3-receptor (ip3k2 Δ1/Y; +/UAS-ip3-receptorIR; fkh-GAL4/+), n = 22 (right), analyzed by histology for the presence of salivary gland material (blue dotted circles) 24 h after puparium formation.

(D) Quantification of data from (C). Data are represented as mean. Statistical significance was determined using a Chi-squared test.

Figure S7. Knockdown of the ip3-receptor in the salivary gland is sufficient to suppress the induction of autophagy by miR-14 mis-expression. Related to Figures 3 and 5

(A) A salivary gland expressing mCherry-Atg8a in all cells, and knockdown of the ip3-receptor as well as mis-expression of miR-14 specifically in GFP-marked clone cells (hsflp/w; pmCherry-Atg8a/UAS-ip3-receptorIR; act<FRT, cd2, FRT>Gal4, UAS-GFP/UAS-luc-miR-14) dissected from wandering larvae for analyses of mCherry-Atg8a puncta.

(B) Quantification of data from Figure S2A (first two columns) and (A) (last two columns). Data are represented as mean +/− SEM; n ≥ 9. Statistical significance was determined using a Student’s t-test.

Table S1. microRNA levels in the salivary gland during cell death. Related to Figure 1

Table S2. List of RNAi lines screened to identify targets of miR-14. Related to Figure 4