Abstract

No-reflow or slow-flow phenomenon is one of the serious complications of percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI) in acute myocardial infarction, as well as during elective procedures, and is an independent predictor of myocardial infarction, and in-hospital and long-term mortality. We present a case of an elective PCI of native coronary artery lesion that was assessed to be vulnerable based on coronary computed tomography angiography, complicated with slow-flow phenomenon.

Keywords: vulnerable plaque, computed tomography

Introduction

No-reflow or slow-flow phenomenon is one of the serious complications of percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI) in acute myocardial infarction (AMI), as well as during elective procedures, and is an independent predictor of myocardial infarction, and in-hospital and long-term mortality [1, 2]. The incidence of no-reflow in elective PCI varies between 2% and 5% and is estimated to be around 30% in primary PCI [3]. The mechanism of no-reflow associated with elective PCI is mainly damage of local tissue and distal embolisation of atherosclerotic material. With development of coronary imaging methods such as intravascular ultrasound (IVUS), optical coherence tomography (OCT) and coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA), it has become possible to identify lesions with high risk of distal embolisation.

Below we present a case of an elective PCI of native coronary artery lesion that was assessed to be vulnerable based on CCTA, complicated with slow-flow phenomenon.

Case report

A 56-year-old man with a medical history of anterior ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) treated with PCI of the left anterior descending artery (LAD) with implantation of everolimus-eluting stent and PCI of first diagonal branch with implantation of sirolimus-eluting stent was admitted to the hospital to perform elective PCI of a tight ostial lesion in the obtuse marginal branch (OM). The patient's comorbidities were a history of ischaemic stroke, left internal carotid artery endarterectomy performed 5 years ago and hyperlipidaemia.

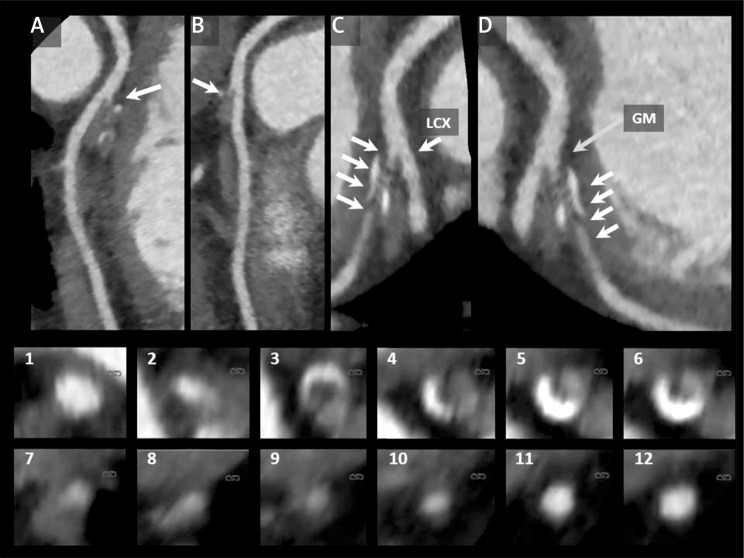

Coronary computed tomography angiography was performed in the patient prior to PCI due to his participation in the clinical trial carried out in the hospital. Coronary computed tomography angiography revealed a tight lesion in the ostium and proximal segment of the marginal branch caused by low-attenuation atheromatous plaque with features of instability. A napkin-ring sign was observed within the lesion (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Coronary computed tomography. A, B – Left circumflex artery – posterior descending artery (PDA) without significant atherosclerotic lesions. Arrow indicates ostium of the obtuse marginal branch. C, D – obtuse marginal branch with long significant stenosis (arrows). 1–12 – serial cross-sectional images of the PDA (1), lesion in OM (2–10), and OM distal to lesion (11, 12)

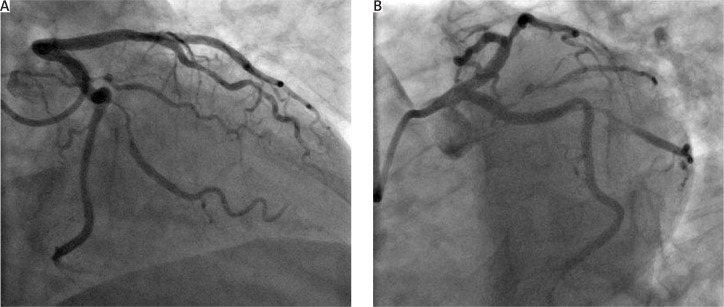

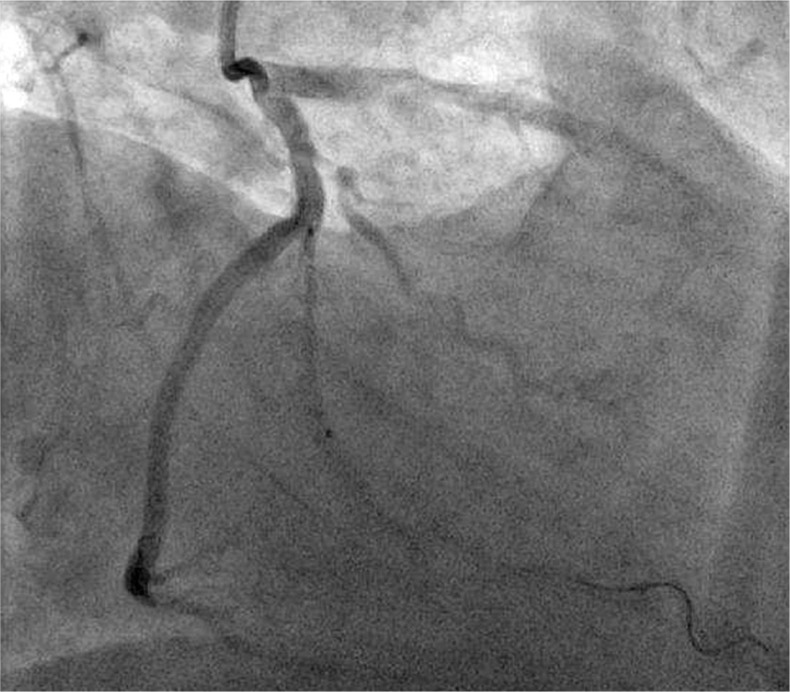

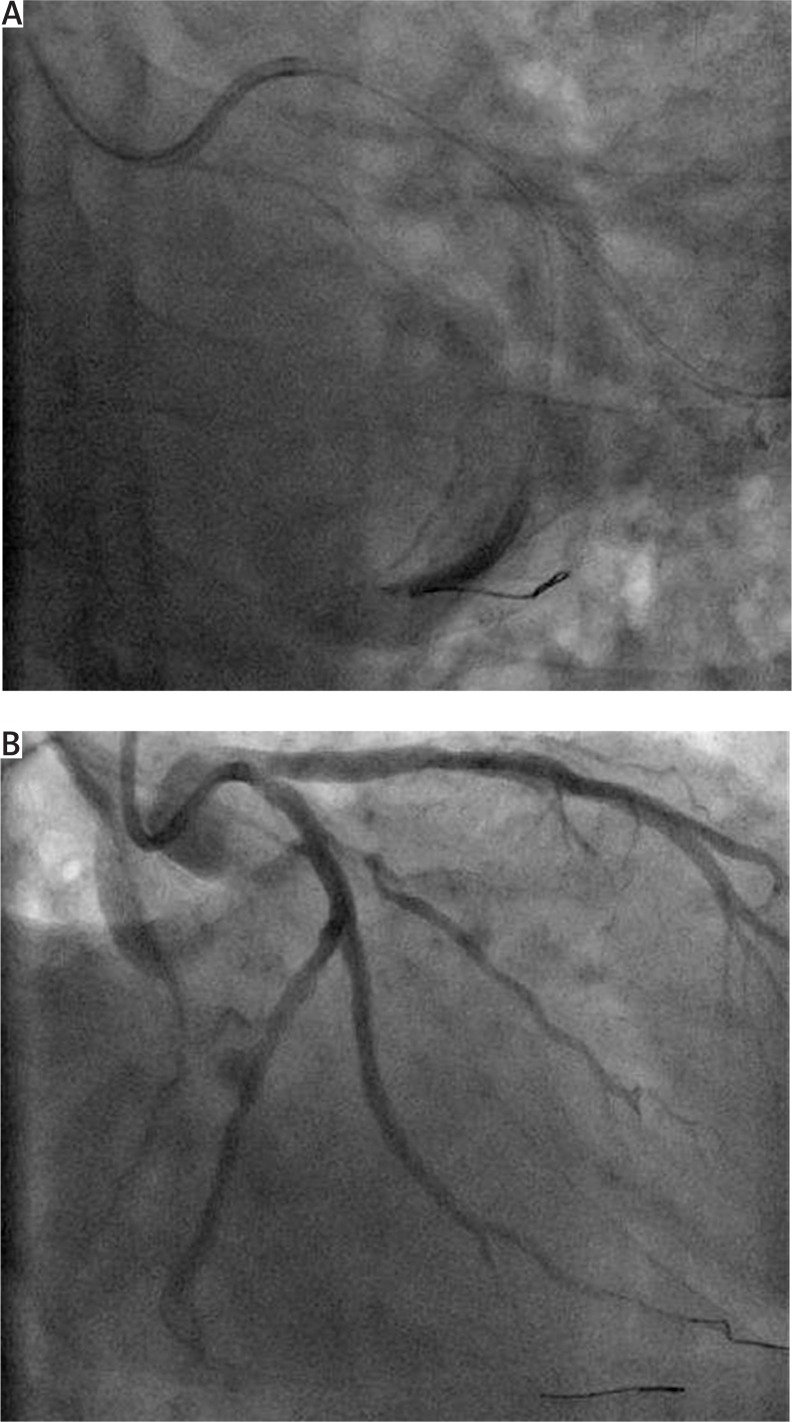

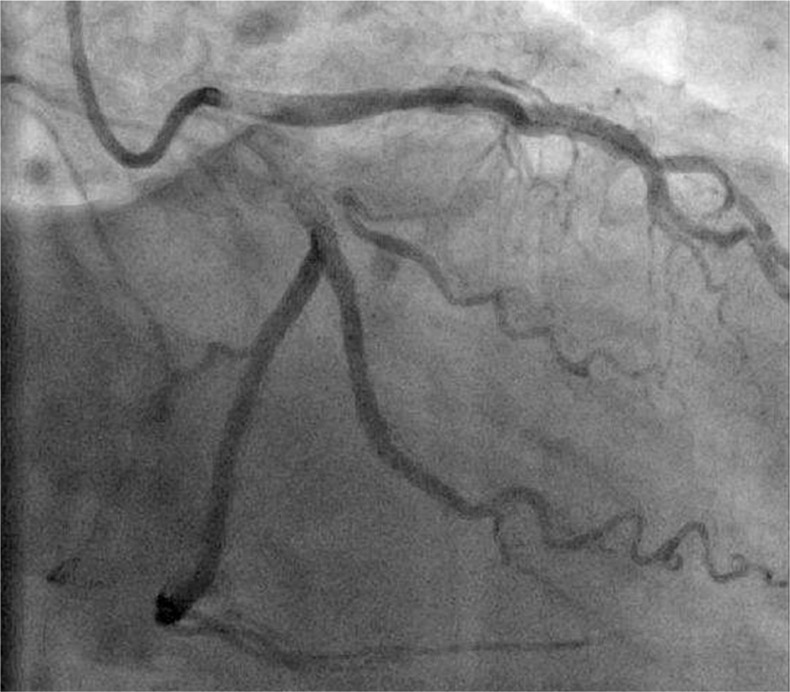

The angiographic views of the tight, long lesion in the marginal branch are shown in Figure 2. Percutaneous coronary intervention was performed by transradial approach using a 6 Fr AL 2 guiding catheter. An intravenous bolus of 100 IU/kg unfractionated heparin (UFH) was administered. Posterior descending artery (PDA) and obtuse marginal branch were engaged with balance middle weight (BMW) guidewires. The lesion was pre-dilated with a 2.5 mm × 20 mm balloon (14 atm), and a 3.0 mm × 26 mm sirolimus-eluting stent was implanted to the marginal branch from the ostium of the vessel (Figure 3). After stent deployment there was TIMI 3 flow in OM and TIMI 1 flow with distal contrast medium staining in the PDA (Figure 4). The patient developed retrosternal chest pain, ST-segment elevation in the ECG, and III° atrioventricular block. Atropine and eptifibatide were administered intravenously, and sequential inflations of the 3.0 mm × 15 mm balloon were performed in the PDA. TIMI 2 flow was restored in the PDA (Figure 5), and gradual symptoms relief was achieved. The patient's stay in the intensive care unit (ICU) was complicated with atrial fibrillation treated with intravenous amiodarone. There was significant elevation of troponin T levels up to 1158 ng/l. In echocardiographic examination new hy-pokinesia of the basal segment of the lateral wall was observed. The Patient was discharged home within 6 days from the PCI.

Figure 2.

Angiographic views of long, tight ostial lesion in obtuse marginal branch prior to PCI; A – RAO 30, CAUD 60; B – LAO 40, CAUD 60

Figure 3.

Placement of 3.0 mm × 26 mm sirolimus-eluting stent in the OM branch; RAO 30, CAUD 30

Figure 4.

Direct angiographic effect of PCI. A – Contrast staining in the distal segment of PDA; B – TIMI 1 flow in the PDA; RAO 30, CAUD 30

Figure 5.

Final angiographic result of the PCI. TIMI 2 flow in the PDA. TIMI 3 flow in the OM; RAO 30, CAUD 30

Discussion

No-reflow or slow-flow phenomenon, as a result of distal embolisation, is associated with myocardial damage, release of myocardial necrosis biomarkers, and prolonged hospitalisation. Since pharmacological treatment of no-reflow is based mainly on vasodilators, the use of which is justified in no-reflow caused by microvascular spasm, usually in the setting of primary PCI in myocardial infarction, but has no impact on embolic no-reflow, it is important to identify lesions with high risk of distal embolisation before PCI.

Intravascular ultrasound findings associated with higher risk of slow-flow are as follows: intraluminal thrombus, echolucent plaque, thin-capped fibroatheroma morphology (TCFA), extensive necrotic core, and large plaque burden [4, 5]. Since non-invasive assessment of coronary plaque morphology in CCTA is becoming widely available and there area a growing number of patients in whom CCTA is performed pre-procedurally, it seems reasonable to look for tomographic predictors of poor PCI outcome and apply sufficient methods of minimising the risk of complications. Kinohira et al. [6] showed in a small study on 26 patients that low-attenuation plaque in CCTA can predict PCI complications, mainly slow-flow.

The napkin-ring (or signet-ring) sign (NRS) is currently being widely studied. It is usually described as a specific attenuation pattern of CCTA-imaged plaques characterised by a plaque core with low attenuation surrounded by a rim-like area of higher attenuation [7]. It corresponds with the thin-capped fibroatheroma described in IVUS studies [8]. Histopathological analyses have shown that the low-attenuation central part of NRS is a lipid-rich necrotic core and the high-attenuation outer rim is a fibrous plaque tissue [7]. However, it has been shown that the NRS sign found in CCTA may also indicate a ruptured plaque in which contrast medium enhances the outskirt of the plaque [9]. To date it has been shown in one study that NRS is a strong predictor of future acute coronary syndromes [10]. There is still little evidence on its association with outcome of elective PCI. In the small study of Nakazawa et al. [11] MDCT images of the culprit lesion were assessed in 51 patients who underwent PCI. In patients in whom no-reflow occurred after PCI there was significantly lower culprit plaque density and signet-ring sign was found more frequently.

Regardless of identification of a vulnerable lesion, the treatment strategy remains an important issue. It might be reasonable for patients with multiple vulnerable plaques to be scheduled for coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) rather than PCI. If PCI is chosen, avoiding balloon predilation and performing direct stenting should be encouraged. The use of distal protection devices should be considered. Its significant impact on reduction of major adverse cardiac events after PCI in saphenous vein grafts was shown in the SAFER trial [12]; however, there was no such relationship in the setting of primary PCI of native coronary arteries in the EMERALD trial [13]. On the other hand, when only patients with angioscopically-detected ruptured plaque were analysed, distal protection reduced microcirculation damage and left ventricular dysfunction [14]. Another concern is the potential use of additional antiplatelet drugs. Pre-procedural glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor inhibitor administration may be beneficial in some high-risk patients undergoing saphenous graft angioplasty [15]. Little is known to date about the effectiveness and potential bleeding risk of such a strategy in stable patients undergoing elective PCI.

Conclusions

The presented case shows the usefulness of CCTA in the detection of vulnerable coronary plaque, which may be associated with embolic complications during PCI. While the number of PCI-scheduled patients with available pre-PCI CCTA is growing, the operators should be encouraged to analyse the CCTA image before the procedure. This will probably influence the patient's pretreatment and procedure strategy to minimise the risk of no-reflow or slow-flow.

References

- 1.Brosh D, Assali AR, Mager A, et al. Effect of no-reflow during primary percutaneous coronary intervention for acute myocardial infarction on six-month mortality. Am J Cardiol. 2007;99:442–4. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.08.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Resnic FS, Wainstein M, Lee MK, et al. No-reflow is an independent predictor of death and myocardial infarction after percutaneous coronary intervention. Am Heart J. 2003;145:42–6. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2003.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salinas P, Jimenez-Valero S, Moreno R, et al. Update in pharmacological management of coronary no-reflow phenomenon. Cardiovasc Hematol Agents Med Chem. 2012;10:256–64. doi: 10.2174/187152512802651024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iijima R, Shinji H, Ikeda N, et al. Comparison of coronary arterial finding by intravascular ultrasound in patients with “transient no-reflow” versus “reflow” during percutaneous coronary intervention in acute coronary syndrome. Am J Cardiol. 2006;97:29–33. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.07.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hong YJ, Jeong MH, Choi YH, et al. Impact of plaque components on no-reflow phenomenon after stent deployment in patients with acute coronary syndrome: a virtual histology-intravascular ultrasound analysis. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:2059–66. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kinohira Y, Akutsu Y, Li HL, et al. Coronary arterial plaque characterized by multislice computed tomography predicts complications following coronary intervention. Int Heart J. 2007;48:25–3. doi: 10.1536/ihj.48.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maurovich-Horvat P, Hoffmann U, Vorpahl M, et al. The napkin-ring sign: CT signature of high-risk coronary plaques? JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2010;3:440–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2010.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kashiwagi M, Tanaka A, Kitabata H, et al. Feasibility of noninvasive assessment of thin-cap fibroatheroma by multidetector computed tomography. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2009;2:1412–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2009.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tanaka A, Shimada K, Yoshida K, et al. Non-invasive assessment of plaque rupture by 64-slice multidetector computed tomography. Comparison with intravascular ultrasound. Circ J. 2008;72:1276–81. doi: 10.1253/circj.72.1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Otsuka K, Fukuda S, Tanaka A, et al. Napkin-ring sign on coronary CT angiography for the prediction of acute coronary syndrome. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;6:448–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2012.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nakazawa G, Tanabe K, Onuma Y, et al. Efficacy of culprit plaque assessment by 64-slice multidetector computed tomography to predict transient no-reflow phenomenon during percutaneous coronary intervention. Am Heart J. 2008;155:1150–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baim DS, Wahr D, George B, et al. Randomized trial of a distal embolic protection device during percutaneous intervention of saphenous vein aorto-coronary bypass grafts. Circulation. 2002;105:1285–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stone GW, Webb J, Cox DA, et al. Distal microcirculatory protection during percutaneous coronary intervention in acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;293:1063–72. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.9.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mizote I, Ueda Y, Ohtani T, et al. Distal protection improved reperfusion and reduced left ventricular dysfunction in patients with acute myocardial infarction who had angioscopically defined ruptured plaque. Circulation. 2005;112:1001–7. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.532820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jonas M, Stone GW, Mehran R, et al. Platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor inhibition as adjunctive treatment during saphenous vein graft stenting: differential effects after randomization to occlusion or filter-based embolic protection. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:920–8. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]