Abstract

Objective

Spinal cord ischemia (SCI) is a devastating, but potentially preventable, complication of thoracic endovascular aortic repair (TEVAR). The purpose of this analysis was to determine what factors predict SCI after TEVAR.

Methods

All TEVAR procedures at a single institution were reviewed for patient characteristics, prior aortic repair history, aortic centerline of flow analysis, and procedural characteristics. SCI was defined as any lower extremity neurologic deficit that was not attributable to an intracranial process or peripheral neuropathy. Forty-three patient and procedural variables were evaluated individually for association with SCI. Those with the strongest relationships to SCI (P < .1) were included in a multivariable logistic regression model, and a stepwise variable elimination algorithm was bootstrapped to derive a best subset of predictors from this model.

Results

From 2002–13, 741 patients underwent TEVAR for various indications and 68 (9.2%) developed SCI (permanent: N = 38; 5.1%). Due to lack of adequate imaging for centerline analysis, 586 patients (any SCI, N = 43; 7.4%) were subsequently analyzed. Patients experiencing SCI after TEVAR were older (SCI 72±11 vs. No SCI, 65±15 years; P < .0001) and had significantly higher rates of multiple cardiovascular risk factors. The stepwise selection procedure identified five variables as the most important predictors of SCI: age (odds ratio, OR, multiplies by 1.3 per 10 years; 95% CI 0.9–1.8, P = .06), aortic coverage length (OR multiplies by 1.3 per 5cm; CI 1.1–1.6, P = .002), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (OR, 1.9; CI .9–4.1, P = .1), chronic renal insufficiency(creatinine ≥ 1.6; OR, 1.9; CI .8–4.2, P = .1), and hypertension (defined as chart history and/or medication; OR, 6.4; CI 2.6–18, P < .0001). A logistic regression model with just these five covariates had excellent discrimination (AUC = .83) and calibration (χ2 = 9.8; P = .28).

Conclusion

This analysis generated a simple model that reliably predicts SCI after TEVAR. This clinical tool can assist decision-making regarding when to proceed with TEVAR, guide discussions about intervention risk, and help determine when maneuvers to mitigate SCI risk should be implemented.

Introduction

Thoracic endovascular aortic repair (TEVAR) has revolutionized the management of thoracic aortic pathologies, with reduced early morbidity and mortality rates compared to open operation1–4. Despite the reduced risk of major morbidity, spinal cord ischemia (SCI) occurs after TEVAR in 2–15% of patients, which can lead to profound long-term disability, and is known to significantly increase the risk of 1-year mortality5–9. Various proactive and reactive treatment protocols have been developed in an attempt to identify strategies for reducing the risk of developing this potentially devastating complication9, 10. However, some of these interventions, such as pharmacologic adjuncts and/or spinal drainage, have their own risk of complications and lead to increased resource utilization, which argues for a selective approach for initiation of these therapies9, 11.

A number of patient and procedure-related factors have been associated with the development of SCI after TEVAR, including operative indication, urgency, aortic coverage length, left subclavian artery coverage, adjunctive procedure use (e.g. conduit, embolization, arch or visceral debranching), age, obesity, blood loss, perioperative hypotension, renal insufficiency, presence of unrepaired abdominal aneurysm and prior history of aortic repair6, 12–15. While these are important for the clinician to consider, several of the variables are not available in the preoperative setting, and there are currently no reliable clinical decision-making tools that can predict SCI after TEVAR.

Given the impact that SCI has on quality of life and survival after TEVAR, avoidance of this complication is tantamount to the success of the operation. The purpose of this study is to develop a predictive model of SCI after TEVAR, which may help inform decision-making about whether and when to offer TEVAR to patients at high risk for SCI, and can guide the use of adjunctive maneuvers to mitigate SCI risk in the perioperative setting.

Methods

The University of Florida Institutional Review Board (FWA00005790) approved this study. A waiver of informed consent was granted because all collected data pre-existed in medical records and no study related interventions or subject contact occurred. Therefore, the rights and welfare of these subjects was not adversely affected.

Patient cohort and definitions

A retrospective analysis was performed on a prospectively maintained endovascular aortic database and all TEVAR patients from 2002–2013 were reviewed. Demographics, comorbidities, history of previous aortic surgery, and procedural details were determined by review of the database and/or electronic medical record. Comorbidities (see Appendix Table I for definitions), coverage zones and procedural adjuncts were defined and recorded using SVS reporting standards16.

Aortic centerline analysis

The first postoperative computed tomographic angiogram (CTA) for each patient was analyzed in order to obtain specific anatomic covariates. There were 586 patients with adequate imaging to create a centerline using an Aquarius workstation (Tera Recon, Sanata Rosa, CA) and they constitute the primary study population in whom subsequent predictive modeling was performed. Multiple measurements were made including total aortic length (defined as the distance from the sinotubular junction to the aortic bifurcation), as well as the length and percentage of covered aorta (proximal stent boundary to distal most stent boundary). Additional variables that were recorded, as well as a detailed description of the centerline measurement methodology, are highlighted in Figure 1. Two independent observers performed the measurements using the described methods, and interobserver agreement was excellent [Spearman correlation = .94, mean difference in measurements = .4cm (±standard deviation (SD) = .37, P = .54)].

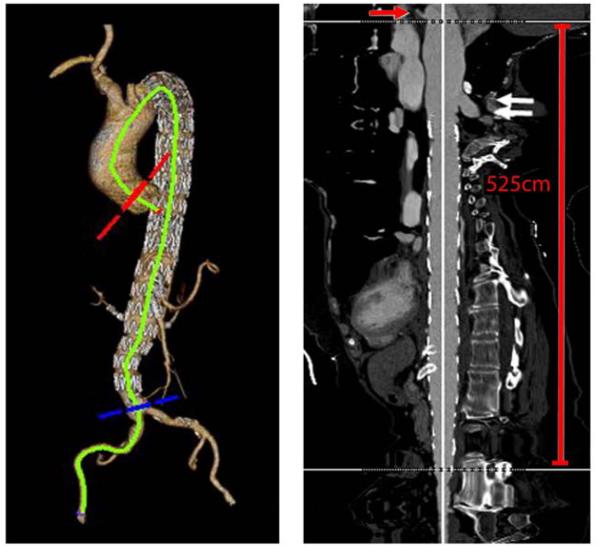

Figure 1.

This image demonstrates the method for obtaining aortic length from the sinotubular junction (red arrow demonstrates the left coronary artery, white arrows are the region of the proximal stent boundary) to the aortic bifurcation. This patient's total aortic length was 525mm along the centerline. A measurement of the total stent coverage which is equivalent to the total aortic coverage length was determined by measurement of the centerline distance from the most proximal stent boundary to the distal most stent boundary. The percentage of aortic coverage was derived by dividing the total aortic coverage length by total aortic length x100. Additional measurements were taken from the distal most stent boundary to the top of the celiac and superior mesenteric artery origins, as well as to the aortic bifurcation. The total number of aortic zones that were covered was tabulated and included total and partial zone coverage's (e.g. if the distal stent boundary extended only partially into Zone 5, then this was tabulated as a covered zone).

Clinical practice

SCI has been consistently7, 12, 14, 17 defined at our institution as any new lower extremity motor and/or sensory deficit that is not explained by any intracranial process and/or peripheral nerve dysfunction (e.g. epidural hematoma, stroke, peripheral neuropathy, or neuropraxia), and may range from frank paralysis to mild paraparesis. Patients were offered preoperative spinal drainage at the discretion of the operating surgeon. In general, elective patients with an anticipated aortic coverage length ≥ 150mm were given preoperative spinal drains, and patients treated emergently had spinal drains placed selectively once stabilized.

If SCI developed, the mean arterial pressure was typically raised to a goal of ≥ 90mmHg, which was achieved using volume resuscitation and vasoactive agents as needed, depending on the clinical scenario. The goal CSF pressure was kept at 10 mmHg, and if symptoms persisted, this would be lowered to 5mmHg to promote efflux of spinal fluid. Patients routinely had CSF drained for 72 hours after the onset of symptoms, and those who did not experience complete resolution of their symptoms postoperatively were classified as having permanent SCI. Adjunctive maneuvers such as motor evoked potentials and/or epidural cooling were not employed. Additionally, pharmacologic agents such as corticosteroids and naloxone were not routinely used during the study interval. Finally, neurological consultation with or without confirmatory spinal MRI was obtained only in equivocal cases. No significant changes occurred to this protocol during the study interval.

Development of SCI prediction model

There was complete demographic, peri-procedural and aortic centerline measurement data for 79% (N = 586) of patients, 43 of whom had SCI. Forty-three patient and procedural variables were evaluated separately for association with SCI. Those with the strongest relationships to SCI (P < .1) were included in a full multivariable logistic regression model. This model included age, stent length, aortic bifurcation to distal TEVAR stent length, distal landing zone designation, preoperative indication, ASA status, COPD, chronic renal insufficiency (Cr ≥ 1.6), smoking, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, peripheral vascular occlusive disease, cerebrovascular occlusive disease, fluoroscopy time, contrast volume exposure and procedure time (incision to dressing). Subsequently, fluoroscopy time, contrast volume and procedure time were removed since they are not available in the preoperative setting.

To derive the best subset of predictors from the full preoperative model, a stepwise elimination algorithm based on the Akaike Information Criterion (the stepAIC function in the R package MASS) was used. Since stepwise procedures are known to be somewhat unstable and vulnerable to the influence of extreme observations, the stepwise procedure was bootstrapped 100 times and the number of times each variable in the full model was selected for inclusion in the reduced model was recorded. This process identified hypertension, age, aortic coverage length, chronic renal insufficiency (CRI) and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) as the most important and consistent predictors of SCI. A model with just these five covariates yielded the following equation: probability of SCI = exp(X)/[1 + exp(X)], where X = A + B*Age + C*coverage length + D(if `yes' HTN) + E (if `yes' COPD) + F (if `yes' preoperative Cr ≥ 1.6), with A = −7.45, B = 0.03, C = 0.006, D = 1.86, E = 0.64, and F = 0.64. To estimate the performance of the model on new data, the model was applied to 1,000 bootstrapped samples from the original dataset and the mean AUC, with 95% confidence intervals, was determined.

Results

Patient characteristics

Between January 2002 and June 2013, 741 patients underwent TEVAR for multiple indications and 68 (9.2%) experienced postoperative SCI (permanent, N = 38; 5.1%). On univariate testing, significant differences in age and multiple comorbidities were found between the two patient cohorts. The data regarding patient demographics, comorbidities and history of prior aortic repair are highlighted in Table I. Details regarding the indication specific SCI rates after TEVAR are demonstrated in Figure 2.

Table I.

Patient demographics and comorbidities of all TEVAR patients

| No SCI (N = 673) | SCI (N = 68) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Feature | No. (%) | No. (%) | P-value |

| Age (mean±SD) | 65±15 | 72±11 | <.0001 |

| Female | 211 (32) | 24 (35) | .6 |

| Body mass index (mean±SD) | 27.6±5.6 | 27.3±6.4 | .7 |

| Hypertension | 259 (39) | 61 (90) | <.0001 |

| Dyslipidemia | 124 (18) | 31 (46) | <.0001 |

| COPD | 58 (9) | 21 (31) | <.0001 |

| Smoking (any history) | 136 (20) | 28 (41) | .0001 |

| Renal insufficiency (Cr > 1.6) | 55 (8) | 22 (32) | <.0001 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 20 (3.) | 11 (16) | <.0001 |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 24 (4) | 7 (10) | .02 |

| Coronary artery disease | 87 (13) | 13 (19) | .2 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 44 (7) | 6 (9) | .6 |

| Arrhythmia | 26 (4) | 5 (7) | .3 |

| Prior aortic repair | 136 (20) | 18 (27) | .3 |

SCI, spinal cord ischemia; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

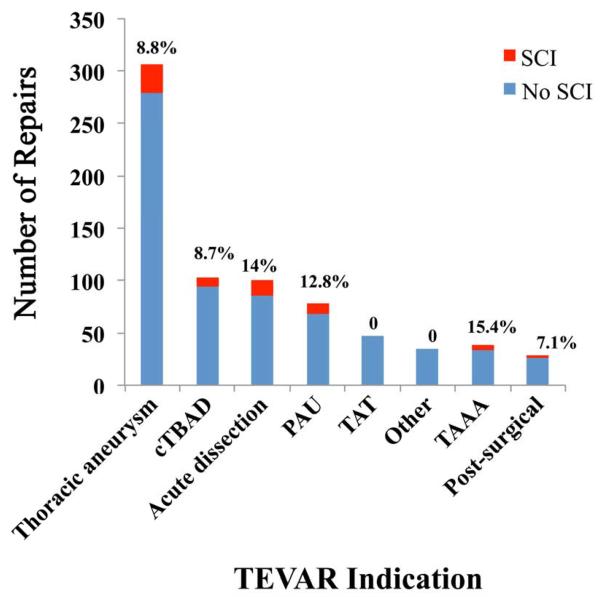

Figure 2.

This graph demonstrates the indications for TEVAR in our data set and the prevalence of any form of SCI in each group at the top of each bar. The most common indication was thoracic aneurysm, with an overall SCI rate of 8.8%. The highest rate of SCI was within the TAAA group and was 15.4%.

The indications, procedural urgency, spinal drain usage, as well as other intraoperative features of the TEVAR patients are depicted in Table II. Rate of preoperative spinal drain use did not differ (P = 1), however patients documented to have experienced postoperative SCI were significantly more likely to have an American Society of Anesthesiology class 4 designation (P = .05) and have greater fluoroscopy (P = .04) and procedure times (P = .05). Details of the anatomic measurement variables that were captured in the centerline analysis are displayed in Table III. Patients undergoing TEVAR for a thoracoabdominal aneurysm indication had the greatest overall coverage length for the entire cohort [mean±SD: 272±104mm; median [IQR] (range): 268 [183, 326] (107, 508)] while traumatic transection cases had the shortest absolute coverage length [100±32; 93 [84, 106] (48, 216)] (Appendix Table II).

Table II.

Procedural characteristics of all patients undergoing TEVAR

| No SCI (N = 673) | SCI (N = 68) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Feature | No. (%) | No. (%) | P-value |

| Indication | |||

| Thoracic aneurysm | 279 (42) | 27 (40) | |

| Acute dissection | 87 (13) | 14 (21) | |

| Chronic type B dissection | 93 (14) | 9 (13) | |

| Othera | 209 (31) | 18 (27) | .4 |

| Urgency | |||

| Urgent/symptomatic | 128 (19) | 16 (24) | |

| Emergent/ruptured | 117 (17) | 15 (22) | .3 |

| ASA Status | |||

| 3 | 145 (22) | 7 (10) | |

| 4 | 391 (58) | 43 (63) | .05 |

| Pre-TEVAR implant spinal drain | 290 (43) | 27 (40) | 1 |

| Postoperative spinal drain | 16 (2) | 38 (56) | <.0001 |

| Anesthesia | |||

| General | 472 (70) | 56 (82) | |

| Regional | 200 (30) | 13 (18) | .1 |

| Device | |||

| Cook/TX2 | 263 (40) | 33 (49) | |

| Gore TAG | 241 (36) | 25 (37) | |

| Fenestrated graft | 38 (6) | 7 (10) | |

| Medtronic Talent/Valiant | 85 (12) | 1 (2) | |

| Bolton Relay | 25 (4) | 1 (2) | |

| Aortic cuff | 13 (2) | 0 | .3 |

| Access vessel open or endo conduit | 139 (21) | 20 (29) | .1 |

| Any intraoperative adjunct | 266 (40) | 27 (40) | 1 |

| Carotid-subclavian bypass | |||

| Postoperative | 7 (1) | 3 (4) | |

| Intraoperative with TEVAR | 41 (6) | 2 (3) | |

| Preoperative | 45 (7) | 6 (9) | .07 |

| Procedural details (median, IQR) | |||

| Fluoroscopy time, min | 18 [12, 29] | 27 [16, 44] | .04 |

| Contrast exposure, mL | 120 [87, 160] | 140 [99, 196] | .09 |

| Estimated blood loss, mL | 250 [200, 300] | 250 [200, 313] | .5 |

| Procedure time, hours | 1.7 [1.2, 2.8] | 2.0 [1.5, 3.2] | .05 |

includes penetrating ulcer, traumatic transection, thoracoabdominal aneurysm, pseudoaneurysm, mycotic aneurysm with visceral debranching, and Kommerel's diverticulum; ASA, American Society of Anesthesiology; IQR, interquartile range

Table III.

Anatomic categorization and measurements of TEVAR patientsa

| No SCI (N = 673) | SCI (N = 68) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Feature (mean±SD) | No. (%) | No. (%) | P-value |

| Proximal landing zone | |||

| Zones 0–2 | 316 (47) | 31 (46) | |

| Zones 3–5 | 353 (53) | 37 (54) | .6 |

| Distal landing zone | |||

| Zone 4 | 267 (40) | 25 (37) | |

| Zone 5 | 308 (46) | 26 (39) | |

| Zones 6–11 | 96 (14) | 16 (24) | .1 |

| Number of zones covered | 3.5±1.5 | 3.8±1.8 | .3 |

| Number of stents implanted | 2.0±1.1 | 2.4±0.9 | <.0001 |

| Total aortic length, mm | 541±62 | 547±54 | |

| Total stented length, mm | 213±88 | 272±65 | <.0001 |

| % aortic coverage | 39±14 | 50±10 | <.0001 |

| Distal stent to aortic bifurcation, mm | 202±85 | 157±54 | <.0001 |

| Celiac to aortic bifurcation, mm | 143±26 | 142±26 | .6 |

| SMA to aortic bifurcation, mm | 125±24 | 123±24 | .6 |

based on available CT imaging; 586 patients had complete imaging however, additional patients had missing CT data and/or non-contrasted CT scans due to chronic renal insufficiency so centerline reconstruction was not always possible; SMA, superior mesenteric arterv

Outcomes

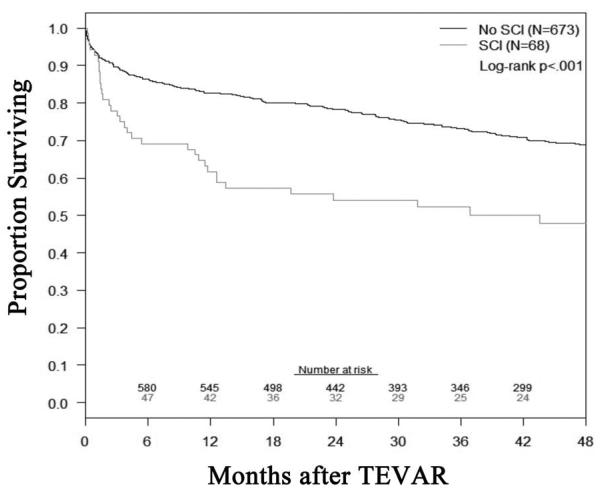

The overall 30-day mortality was 6% (N = 4) and 4% (N = 25) in patients with and without SCI (P = .3), respectively. Mean length of stay was significantly greater in patients with SCI [median 13 (IQR 8, 22) vs. No SCI, 5 (3, 9) days; P < .0001]. Additional details of other complications that occurred in the two groups are listed in Table IV. Of note, SCI patients were significantly more likely to have a postoperative pulmonary (P = .0004) and/or renal complication (P = .005). The all-cause mortality, defined as any death that occurred during the follow-up interval, was significantly different between patients with or without SCI after TEVAR (log-rank P < .001; Appendix figure).

Table IV.

Outcomes after TEVAR in all patients with or without SCI

| No SCI (N = 673) | SCI (N = 68) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Feature | No. (%) | No. (%) | P-valuea |

| 30-day mortality | 25 (4) | 4 (6) | .3 |

| Length of stay (median [IQR]) | 5 [3, 9] | 13 [8, 22] | <.0001 |

| Complications | |||

| Pulmonary | 51 (8) | 15 (22) | .0004 |

| Renal | 35 (5) | 10 (15) | .005 |

| Bleeding | 25 (4) | 4 (6) | .3 |

| Stroke | 21 (3) | 4 (6) | .3 |

| Gastrointestinal | 20 (3) | 3 (4) | .5 |

| Cardiac | 20 (3) | 4 (6) | .3 |

P-values were generated using Chi-square of Fischer's exact when appropriate; IQR, interquartile range

Predictors of SCI

Of 741 total patients, 155 (21%) were excluded from the analysis because they did not receive follow-up CT scans and thus their percent-coverage data were missing. A comparison of these patients to the 586 patients included in the development of the model shows that the excluded patients had a significantly higher rate of SCI, were significantly older, had higher rates of multiple comorbidities, presented more urgent/emergently and were more likely to suffer multiple postoperative complications (Table V).

Table V.

Comparison of included and excluded patients used in development of the preoperative prediction of SCI after TEVAR model

| Feature, No. (%) | In model (N=586, 79%) | Not in model (N= 155,21%) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any SCI | 43 (7%) | 25 (16%) | .001 |

| Age±SD | 65±15 | 68±14 | |

| Female | 184 (32%) | 53 (34%) | .02 |

| BMI±SD | 28±6 | 27±5 | .6 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Hypertension | 243 (42%) | 77 (50%) | .08 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 118 (20%) | 37 (24%) | .4 |

| Coronary artery disease | 72 (12%) | 28 (18%) | .08 |

| Chronic renal insufficiency (Cr > 1.6) | 51 (9%) | 26 (17%) | .005 |

| Diabetes | 40 (7%) | 10 (7%) | 1 |

| Congestive heart failure | 22 (4%) | 8 (5%) | .6 |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 24 (4%) | 7 (5%) | .9 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 18 (3%) | 13 (8%) | .007 |

| Arrhythmia | 24 (4%) | 7 (5%) | .9 |

| Indication | |||

| Thoracic aneurysm | 245 (42%) | 61 (40%) | |

| Acute dissection | 76 (13%) | 25 (16%) | |

| Chronic type B dissection | 85 (15%) | 17 (11%) | |

| Other | 177 (30%) | 50 (33%) | .5 |

| Urgency | |||

| Elective | 379 (65%) | 84 (55%) | |

| Urgent/emergent | 206 (35%) | 70 (45%) | .007 |

| Anesthesia type | |||

| General | 403 (69%) | 125 (81%) | |

| Regional | 179 (30%) | 30 (19%) | |

| Local | 3 (1) | 0 | .02 |

| Procedure related details | |||

| Proximal LZ Zone 0–2a | 258(44%) | 89(57%) | .02 |

| Distal LZ Zone 4 | 157(27%) | 135(89%) | <.0001 |

| Any adjunct use | 232 (40%) | 61 (39%) | 1 |

| Use of open or endo conduit | 126 (22%) | 33 (22%) | 1 |

| Procedure time (hours±SD) | 2.2±1.6 | 2.5±2.0 | .6 |

| Fluoroscopy time (min), median, IQR | 18 [0, 165] | 21 [13,32] | .6 |

| Contrast use (mL±SD) | 128±64 | 121±70 | .6 |

| Estimated blood loss (mL), median, IQR | 250 [200, 300] | 250 [150, 338] | .2 |

| Outcomesb | |||

| In-hospital and/or 30-day death | 7 (1%) | 22 (14%) | <.0001 |

| Any complication | 192 (33%) | 76 (49%) | .0002 |

| Stroke | 12 (2%) | 13 (8%) | .0005 |

| Renal complication | 26 (4%) | 19 (12%) | .0009 |

| Pulmonary complication | 42 (7%) | 24 (16%) | .002 |

BMI, body mass index; Other includes penetrating ulcer, traumatic transection, thoraco abdominal aneurysm, pseudoaneurysm, mycotic aneurysm with visceral debranching, and Kommerel's diverticulum;

When individual Zone analysis was performed, no significant association with SCI was noted;

All other complication categories had no significant differences

Of the 43 patient and procedural variables that were evaluated separately for association with SCI, 13 with the strongest relationships to SCI (P < .1) were included in a full multivariable logistic regression model. Of these 13, a stepwise variable elimination procedure, bootstrapped 100 times to protect against spurious associations, identified five as having the most predictive power (Table VI). Prior analysis demonstrated that age and aortic coverage length had roughly linear relationships with the probability of developing SCI, so these associations were modeled as linear throughout the model-building process. These associations are demonstrated in Figure 3.

Table VI.

Results of step-wise elimination algorithma

| Variable | Number of times chosen as important predictor |

|---|---|

| Aortic coverage length | 96 |

| Hypertension | 93 |

| Age | 67 |

| COPD | 66 |

| CRI(Cr > 1.6) | 49 |

| ASA class 4 | 44 |

| Smoking (any history) | 38 |

| Indication | 33 |

| Cerebrovascular occlusive disease | 30 |

| Distal landing zone beyond Zone 4 | 29 |

After initial 100 bootstrapped samples were analyzed to generate this list of predictors, the best set of predictors were then chosen and 1000 bootstrapped samples were tested to determine model reliability

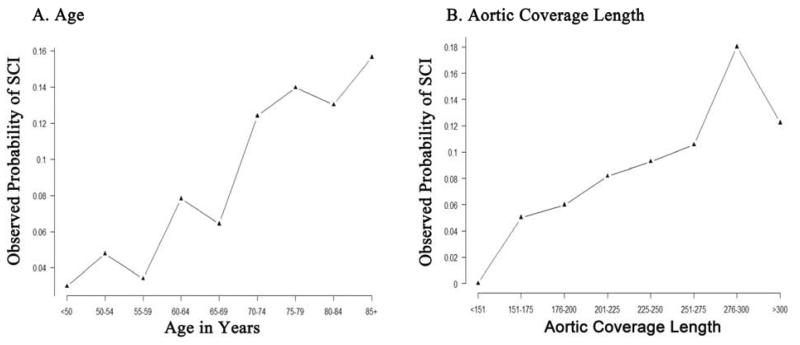

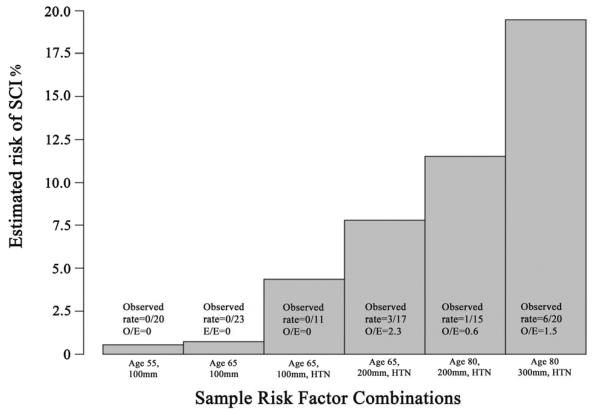

Figure 3.

These graphs demonstrate the association of age (3A) and coverage length (3B) to SCI. There is essentially a linear relationship with these two variables to the occurrence of SCI.

When further discriminating the nature of hypertension as a SCI predictor, a weak association with chronic (>30 days) preoperative use of alpha blocking agents (e.g. doxazosin, terazosin, prazosin, clonidine, methyldopa, guanethidine) was noted (P = .07). No other medication class or total number of anti-hypertensive medications (P = .4) was found to be associated with development of SCI.

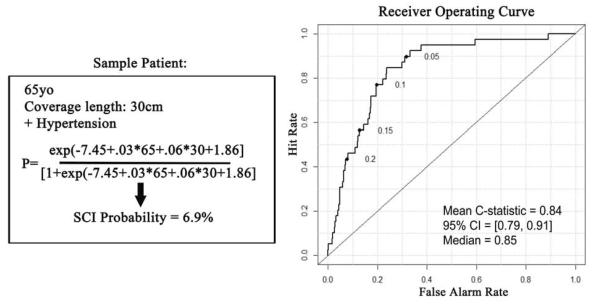

Selected predictors of any SCI were age (odds ratio, OR, multiplies 1.3 per 10 years; 95% CI 0.9–1.8, P = .06), aortic coverage length (OR multiplies 1.3 per 5cm; CI 1.1–1.6, P = .002), COPD (OR, 1.9; CI .9–4.1, P = .1), CRI (OR, 1.9; CI .8–4.2, P = .1), and hypertension (OR, 6.4; CI 2.6–18, P < .0001). A model with only these covariates had excellent discrimination (AUC = .83) and calibration (χ2 = 9.8; P = .28) (Figure 4). In 1,000 bootstrapped iterations, the model had mean AUC = 0.84 (95% CI = 0.79, 0.91).

Figure 4.

On the left is the model developed from our multivariable analysis. The sample case is a 65 year old patient with 30cm of coverage length and a history of hypertension. The probability of SCI in this patient is 6.9% based on those parameters. On the right is the receiver operating curve, which demonstrates an area under the curve of 0.84 from the bootstrapped iterative sampling.

The additive impact of the different predictors on the risk of developing SCI after TEVAR is further demonstrated in Figure 5. For example, a 65-year-old patient with no history of hypertension who undergoes TEVAR with an aortic coverage length of 10cm has a predicted risk of SCI that is ≤ 1%; however an 80-year-old patient with hypertension and planned 30cm of aortic coverage can have a SCI risk that approaches 20%.

Figure 5.

This figure demonstrates the estimated probability of SCI related to each of the demonstrated combinations of risk factors. A patient that is 65 year old patient with a short coverage length of 100mm and no history of hypertension would have a preoperative predicted rate of post-TEVAR SCI of <1%, while an 80 year old patient with a long coverage length of 300mm and a history of hypertension would have a predicted SCI rate that can approach 20%.

Discussion

Multiple reports have documented various predictors of SCI after TEVAR14, 15, 18–22. However, the current analysis is the first to identify independent factors that can be used preoperatively to derive the predicted risk of SCI after TEVAR. Preoperative variables that were most strongly associated with SCI included advanced age, hypertension, COPD, CRI and aortic coverage length. This predictive model had high fidelity and generated a simple clinical decision tool based on readily available factors that can be used to facilitate clinical decision making and inform patient counseling about the risk of TEVAR.

The less invasive nature of TEVAR has led to repeated demonstration that it has lower perioperatively morbidity and mortality when compared to open operation1, 2, 4, 23, which has resulted in an increasing number of patients deemed eligible for repair without strong evidence of longer term benefit24, 25. Despite the perioperative advantage of TEVAR compared to open aortic repair, SCI remains a devastating complication that has profound influence on long-term outcome. In our own experience, patients who develop permanent SCI after TEVAR have a mean postoperative survival of 37±5 compared to 72±4 months in patients without SCI (P < .0006)7. Therefore, identification of which patients are most vulnerable and/or prevention of this complication are crucial to achieving successful outcome after TEVAR.

There are multiple reported risk factors for development of SCI after TEVAR that are based on patient demographics, comorbidities, presentation, anatomic considerations of the repair, and postoperative events5, 6, 12, 15, 26. The most frequently identified risk factor is length of aortic coverage. A variety of thoracic aortic pathologies may involve large segments of the aorta, such as the case with thoracoabdominal aneurysm and dissection related pathology. Indeed, in our own experience, patients undergoing TEVAR for these indications had the highest overall rates of SCI (Figure 2). Importantly, our study demonstrated that aortic coverage length was linearly correlated with the risk of SCI, so choice of any specific value would be arbitrary. The reason for the increased risk of SCI as a function of aortic coverage length is thought to be due to the segmental blood supply of the spinal cord and endograft coverage of important radicular arteries, as well as the putative location of the Artery of Adamkawiecz in the distal thoracic aorta27, 28.

An interesting predictor of SCI after TEVAR in this analysis is a preoperative diagnosis of hypertension. While not often described in the TEVAR literature, some insight about the potential physiologic reason for this association may be gained by review of the open TAAA literature. A variety of hemodynamic factors have been reported to be associated with elevated risk of SCI in open TAAA repair, including arterial hypotension, decreased cardiac index, and reduced oxygen carrying capacity from anemia29, 30. One mechanistic explanation as to why hypertension was such an important predictor in our series may be related to perturbations in collateral blood flow to the spinal cord. Spinal cord perfusion pressure is dictated by the difference in mean systemic arterial pressure and cerebrospinal fluid pressure. It is possible that patients with pre-existing hypertension require a higher basal mean arterial pressure to maintain cord perfusion after TEVAR similar to how certain patient groups with renal artery stenosis experiencing postoperative hypotension are vulnerable to acute kidney injury31.

Another important variable that was identified in this analysis is age. Other reports have corroborated this finding14, 32; however there may be several explanations for the associated risk of SCI with increasing age. From a statistical standpoint, age is a better candidate predictor than any single comorbidity since it is a continuous variable that all patients possess, which allows any two patients to be directly compared. The presumption that older patients have higher likelihood of multiple comorbidities that increase risk of SCI would not entirely explain the age correlation to SCI since the effect of age should disappear when all the different covariates were considered in the development of the model. The more probable explanation is that older patients likely have many unknown biologic vulnerabilities that cannot be accounted for in the prediction model. We speculate that these vulnerabilities may be related to subtle postoperative derangement in cardiac performance indices, underappreciated comorbidity severity, and/or unmeasured local and systemic changes in spinal cord metabolism.

Finally, our model included chronic renal insufficiency, as well as COPD. Renal insufficiency has been reported to be significantly associated with SCI in both TEVAR6, 26 and open TAAA series32, 33. A more precise method for defining chronic renal insufficiency would have been analysis of preoperative estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) instead of using a creatinine ≥ 1.6. However, we excluded eGFR as a candidate predictor in our model because this data point was missing for 28% of subjects. Notably, SCI rates among patients for whom eGFR was available show a highly significant and approximately linear relationship. Unadjusted for any covariates, the odds of SCI are estimated to multiply by 0.98 for each unit increase in eGFR (95% CI = [0.97, 0.99], P < .001). The mechanism for this is poorly understood, but some have postulated that CRI is a marker for severe systemic peripheral atherosclerotic disease. Accordingly, these patients may have diseased radicular collaterals making the spinal cord more susceptible to hemodynamic perturbations after TEVAR. Similarly, although not previously described in TEVAR subjects, COPD patients may have compromised oxygen kinetics34 which may lead to the increased risk of axonal injury during times of neuronal ischemia.

Our current clinical practice has evolved as a result of this analysis and appreciation of the increasing body of literature on the topic of SCI after TEVAR. We currently employ a liberal spinal drainage protocol and aggressively revascularize the left subclavian artery in elective cases in which coverage of the vessel origin is required to achieve an adequate proximal landing zone; however, our blood pressure management has been modified. Examples of this include more routine use of permissive hypertension (goal MAP > 90mmHg in all patients), and many patients now have their alpha-blocking and/or angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor medications withheld perioperatively. This shift in clinical practice is supported by the report from Bobadilla and colleagues10 and makes our management more proactive than reactive to the development of SCI after TEVAR. Additionally, while we have a well-described and previously published SCI treatment protocol7, 12, 14, 17, we are developing a `spinal cord ischemia bundle' similar to what has been done for ventilator associated pneumonia in surgical intensive care units35. This effort will hopefully pre-identify the most vulnerable patients and improve care processes. Lastly, the risk model is used in our preoperative decision making when trying to decide which patients should receive TEVAR, as well as to improve discussions about the risks and benefits of repair.

There are several limitations to this study including the retrospective, single-center experience, which introduces inherent selection bias to the analysis. Although we offer a novel description of a preoperative prediction clinical decision making tool for SCI after TEVAR, validation in a multi-center trial and/or registry dataset is required prior to broader application in routine clinical practice. Intercostal and hypogastric artery patency were not specifically captured in the dataset and may have allowed better refinement of the predictive model. Despite this shortcoming, our model had an AUC of 0.83, which is excellent for a biologic prediction model.

Hypertension was not anticipated to be such a strong independent predictor of the development of SCI after TEVAR so mechanistic insight about this covariate is limited. The retrospective nature of the study restricts the ability to accurately grade hypertension severity and duration. A chart history or chronic (> 30 day) preoperative use of anti-hypertensive medications was used to define hypertension and patient medication compliance history is not available. Importantly, we do not have detailed intraoperative or postoperative hemodynamic data to help determine whether and when true or relative hypotension occurred, making it difficult to determine what role this played in the pathophysiology of each patient's SCI. However, our sense is that relative hypotensive events (compared to the patient's preoperative outpatient baseline blood pressure) may have precipitated SCI in some cases, especially since hypertension was a significant independent predictor in the model. Additionally, this analysis relied upon several broad definitions to document other patient comorbidities, and the imprecise severity grading and resulting impact on the analysis is not readily known.

Further, SCI was defined broadly, which increased overall sensitivity for its detection and could lower specificity. This may have introduced unmeasured bias and/or confounding into the models. Despite having a relatively large number of patients in the analysis, the event rate for SCI is modest, which limits the number of predictors that can be reasonably identified without over-fitting statistical models. This is particularly important since there are known differential risks with various patient presentations (e.g. urgent/emergent presentations, dissection-related pathology, etc.). We excluded 21% of the patients in the original dataset, which could have allowed for more robust modeling; however, missing CT imaging did not allow for this analysis. Notwithstanding removal of these subjects, four of the five variables we identified as predictors of SCI for patients included in the analysis are also associated with SCI for the group of excluded patients, so we believe the likelihood that the exclusions biased our results is small. However, any association between aortic coverage length and SCI in the group of excluded patients, along with the effect it might have had on our results, cannot be determined.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this study demonstrated that hypertension, advanced age, COPD, CRI and longer aortic coverage lengths are highly predictive of SCI after TEVAR. Based on these data, we have modified our existing SCI management protocols by liberalizing our postoperative blood pressure parameters and use these data in our patient discussions and decision algorithm for whether and when to proceed with aortic repair. Validation of this predictive model is needed before broader clinical application should occur.

Appendix Table 1.

Comorbidity definitions

| Comorbidity | Definition |

|---|---|

| Arrhythmia | -Requiring medical intervention and/or escalation in monitoring/care level |

| Coronary artery disease (CAD) | -Any history of myocardial infarction [MI], angina, prior coronary intervention, or ECG changes consistent with prior MI |

| Cerebrovascular disease | -History of TIA, stroke, and/or prior carotid endarterectomy/stent |

| Congestive heart failure (CHF) | -Chart history, New York Heart Association II or greater or on pre-operative evaluation, EF <40% |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) |

-Chart history or pre-operative pulmonary function testing consistent with the diagnosis |

| Diabetes mellitus | -Chart history, insulin or non-insulin requiring |

| Chronic renal insufficiency | -Creatinine > 1.6 and/or dialysis dependence |

| Hypertension | -Chart history, on anti-hypertensive medications or pre-operative blood pressure ≥ 140/90mmHg |

| Dyslipidemia | -Chart history, on cholesterol-lowering medications |

| Peripheral arterial disease | -ABI < 0.9, chart history, prior peripheral endovascular intervention or open infrainguinal reconstruction |

ECG, electrocardiogram; TIA, transient ischemic attack; ABI, ankle brachial index

Appendix Table 2.

Aortic coverage length data for various TEVAR indications*

| Aortic Coverage Length, mm |

||

|---|---|---|

| Indication (No.) | Mean(±SD) | Median [IQR] (range) |

| Acute dissection (N = 75) | 245 (74) | 253 [186, 285] (90, 451) |

| Chronic type B dissection (N = 86) | 238 (70) | 249 [183, 285] (102, 457) |

| Thoracic aneurysm (N = 245) | 238 (81) | 237 [183, 283] (56, 494) |

| Penetrating ulcer (N = 62) | 160 (61) | 141 [122, 186] (76, 343) |

| Traumatic transection (N = 37) | 100 (32) | 93 [84, 106] (48, 216) |

| Thoracoabdominal aneurysm (N = 31) | 272 (104) | 268 [183, 326] (107, 508) |

| Post-surgical pseudoaneurysm (N = 22) | 178 (79) | 181 [119, 209] (34, 376) |

| Other (N = 26)□ | 134 (62) | 125 [109, 147] (66, 386) |

N = 586patients with available CT imaging that was adequate for aortic centerline 3D reconstruction;

Other includes Kommerel's diverticulum, atheromatous disease, and mycotic indications

Appendix figure.

This figure demonstrates the all-cause mortality after TEVAR for patients with and without any degree of SCI (log-rank P <.001). The standard error of the mean is < 10% for all displayed intervals.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Presented at the Vascular Annual Meeting, June 6th, 2014 Boston, MA

References

- 1.Patel HJ, Williams DM, Upchurch GR, Jr, Dasika NL, Passow MC, Prager RL, et al. A comparison of open and endovascular descending thoracic aortic repair in patients older than 75 years of age. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2008;85:1597–1603. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.01.044. discussion 1603–1594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheng D, Martin J, Shennib H, Dunning J, Muneretto C, Schueler S, et al. Endovascular aortic repair versus open surgical repair for descending thoracic aortic disease a systematic review and meta-analysis of comparative studies. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:986–1001. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.11.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gopaldas RR, Huh J, Dao TK, LeMaire SA, Chu D, Bakaeen FG, et al. Superior nationwide outcomes of endovascular versus open repair for isolated descending thoracic aortic aneurysm in 11,669 patients. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 2010;140:1001–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2010.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cambria RP, Crawford RS, Cho JS, Bavaria J, Farber M, Lee WA, et al. A multicenter clinical trial of endovascular stent graft repair of acute catastrophes of the descending thoracic aorta. Journal of vascular surgery. 2009;50:1255–1264. e1251–1254. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2009.07.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feezor RJ, Lee WA. Strategies for detection and prevention of spinal cord ischemia during tevar. Semin Vasc Surg. 2009;22:187–192. doi: 10.1053/j.semvascsurg.2009.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buth J, Harris PL, Hobo R, van Eps R, Cuypers P, Duijm L, et al. Neurologic complications associated with endovascular repair of thoracic aortic pathology: Incidence and risk factors. A study from the european collaborators on stent/graft techniques for aortic aneurysm repair (eurostar) registry. J Vasc Surg. 2007;46:1103–1110. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2007.08.020. discussion 1110–1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DeSart K, Scali ST, Feezor RJ, Hong M, Hess PJ, Jr, Beaver TM, et al. Fate of patients with spinal cord ischemia complicating thoracic endovascular aortic repair. Journal of vascular surgery. 2013;58:635–642. e632. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2013.02.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fairman RM, Criado F, Farber M, Kwolek C, Mehta M, White R, et al. Pivotal results of the medtronic vascular talent thoracic stent graft system: The valor trial. J Vasc Surg. 2008;48:546–554. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2008.03.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keith CJ, Jr, Passman MA, Carignan MJ, Parmar GM, Nagre SB, Patterson MA, et al. Protocol implementation of selective postoperative lumbar spinal drainage after thoracic aortic endograft. Journal of vascular surgery. 2012;55:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2011.07.086. discussion 8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bobadilla JL, Wynn M, Tefera G, Acher CW. Low incidence of paraplegia after thoracic endovascular aneurysm repair with proactive spinal cord protective protocols. Journal of vascular surgery. 2013;57:1537–1542. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2012.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hanna JM, Andersen ND, Aziz H, Shah AA, McCann RL, Hughes GC. Results with selective preoperative lumbar drain placement for thoracic endovascular aortic repair. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2013;95:1968–1974. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.03.016. discussion 1974–1965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feezor RJ, Martin TD, Hess PJ, Jr, Daniels MJ, Beaver TM, Klodell CT, et al. Extent of aortic coverage and incidence of spinal cord ischemia after thoracic endovascular aneurysm repair. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;86:1809–1814. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.09.022. discussion 1814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Amabile P, Grisoli D, Giorgi R, Bartoli JM, Piquet P. Incidence and determinants of spinal cord ischaemia in stent-graft repair of the thoracic aorta. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2008;35:455–461. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2007.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martin DJ, Martin TD, Hess PJ, Daniels MJ, Feezor RJ, Lee WA. Spinal cord ischemia after tevar in patients with abdominal aortic aneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 2009;49:302–306. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2008.08.119. discussion 306–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gravereaux EC, Faries PL, Burks JA, Latessa V, Spielvogel D, Hollier LH, et al. Risk of spinal cord ischemia after endograft repair of thoracic aortic aneurysms. J Vasc Surg. 2001;34:997–1003. doi: 10.1067/mva.2001.119890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fillinger MF, Greenberg RK, McKinsey JF, Chaikof EL. Reporting standards for thoracic endovascular aortic repair (tevar) Journal of vascular surgery. 2010;52:1022–1033. 1033, e1015. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2010.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feezor RJ, Martin TD, Hess PJ, Jr, Beaver TM, Klodell CT, Lee WA. Early outcomes after endovascular management of acute, complicated type b aortic dissection. Journal of vascular surgery. 2009;49:561–566. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2008.09.071. discussion 566–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ullery BW, Cheung AT, Fairman RM, Jackson BM, Woo EY, Bavaria J, et al. Risk factors, outcomes, and clinical manifestations of spinal cord ischemia following thoracic endovascular aortic repair. J Vasc Surg. 2011;54:677–684. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2011.03.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cheung AT, Pochettino A, McGarvey ML, Appoo JJ, Fairman RM, Carpenter JP, et al. Strategies to manage paraplegia risk after endovascular stent repair of descending thoracic aortic aneurysms. Ann Thorac Surg. 2005;80:1280–1288. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2005.04.027. discussion 1288–1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khoynezhad A, Donayre CE, Bui H, Kopchok GE, Walot I, White RA. Risk factors of neurologic deficit after thoracic aortic endografting. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;83:S882–889. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.10.090. discussion S890–882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schlosser FJ, Verhagen HJ, Lin PH, Verhoeven EL, van Herwaarden JA, Moll FL, et al. Tevar following prior abdominal aortic aneurysm surgery: Increased risk of neurological deficit. J Vasc Surg. 2009;49:308–314. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2008.07.093. discussion 314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Czerny M, Eggebrecht H, Sodeck G, Verzini F, Cao P, Maritati G, et al. Mechanisms of symptomatic spinal cord ischemia after tevar: Insights from the european registry of endovascular aortic repair complications (eurec) J Endovasc Ther. 2012;19:37–43. doi: 10.1583/11-3578.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stone DH, Brewster DC, Kwolek CJ, Lamuraglia GM, Conrad MF, Chung TK, et al. Stent-graft versus open-surgical repair of the thoracic aorta: Mid-term results. Journal of vascular surgery. 2006;44:1188–1197. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2006.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goodney PP, Travis L, Lucas FL, Fillinger MF, Goodman DC, Cronenwett JL, et al. Survival after open versus endovascular thoracic aortic aneurysm repair in an observational study of the medicare population. Circulation. 2011;124:2661–2669. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.033944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scali ST, Goodney PP, Walsh DB, Travis LL, Nolan BW, Goodman DC, et al. National trends and regional variation of open and endovascular repair of thoracic and thoracoabdominal aneurysms in contemporary practice. Journal of vascular surgery. 2011;53:1499–1505. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2011.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ullery BW, Quatromoni J, Jackson BM, Woo EY, Fairman RM, Desai ND, et al. Impact of intercostal artery occlusion on spinal cord ischemia following thoracic endovascular aortic repair. Vasc Endovascular Surg. 2011;45:519–523. doi: 10.1177/1538574411408742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Adams HD, Van Geertruyden HH. Neurologic complications of aortic surgery. Ann Surg. 1956;144:574–610. doi: 10.1097/00000658-195610000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Acher CW, Wynn M. A modern theory of paraplegia in the treatment of aneurysms of the thoracoabdominal aorta: An analysis of technique specific observed/expected ratios for paralysis. Journal of vascular surgery. 2009;49:1117–1124. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2008.10.074. discussion 1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blaisdell FW, Cooley DA. The mechanism of paraplegia after temporary thoracic aortic occlusion and its relationship to spinal fluid pressure. Surgery. 1962;51:351–355. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marini CP, Levison J, Caliendo F, Nathan IM, Cohen JR. Control of proximal hypertension during aortic cross-clamping: Its effect on cerebrospinal fluid dynamics and spinal cord perfusion pressure. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1998;10:51–56. doi: 10.1016/s1043-0679(98)70018-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Philip F, Gornik HL, Rajeswaran J, Blackstone EH, Shishehbor MH. The impact of renal artery stenosis on outcomes after open-heart surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:310–316. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.09.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.LeMaire SA, Miller CC, 3rd, Conklin LD, Schmittling ZC, Koksoy C, Coselli JS. A new predictive model for adverse outcomes after elective thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm repair. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2001;71:1233–1238. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(00)02678-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Coselli JS, LeMaire SA, Miller CC, 3rd, Schmittling ZC, Koksoy C, Pagan J, et al. Mortality and paraplegia after thoracoabdominal aortic aneurysm repair: A risk factor analysis. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2000;69:409–414. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(99)01478-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vogiatzis I, Zakynthinos S, Georgiadou O, Golemati S, Pedotti A, Macklem PT, et al. Oxygen kinetics and debt during recovery from expiratory flow-limited exercise in healthy humans. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2007;99:265–274. doi: 10.1007/s00421-006-0342-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Resar R, Pronovost P, Haraden C, Simmonds T, Rainey T, Nolan T. Using a bundle approach to improve ventilator care processes and reduce ventilator-associated pneumonia. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2005;31:243–248. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(05)31031-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]