Abstract

Background

Opioid-dependent (OD) women tend to engage in unprotected sex with high-risk partners, placing themselves at elevated risk for sexually transmitted HIV infection. This behavior generally persists after completion of interventions that increase sexual HIV risk reduction knowledge and skills, suggesting that decision-making biases may influence HIV transmission among OD women.

Methods

The primary aim of this report is to examine delay discounting of condom-protected sex among OD women and non-drug-using control women using the novel Sexual Discounting Task (SDT; Johnson and Bruner, 2012). Data were collected from 27 OD women and 33 non-drug-using control women using the SDT, a monetary discounting task, and the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (BIS-11).

Results

OD women discounted the value of delayed condom-protected sex more steeply than controls for hypothetical sexual partners in the two sets of paired partner conditions examined. Overall, women discounted condom protected sex more steeply for partners they perceived as being lowest STI risk vs. those they perceived as being highest risk. Steeper discounting of condomprotected sex was significantly associated with higher scores on the BIS-11, but not with discounting of money.

Conclusions

Delay discounting of condom-protected sex differs between OD women and non-drug-using women, is sensitive to perceived partner risk, and is correlated with a self-report measure of impulsivity, the BIS-11. The effect of delay on sexual decision-making is a critical but underappreciated dimension of HIV risk among women, and the SDT appears to be a promising measure of this domain. Further investigation of these relationships is warranted.

Keywords: HIV/AIDS, Delay discounting, Opioid dependence, Women

1. INTRODUCTION

Approximately 290,000 women in the U.S. are currently infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), with over 10,000 new infections occurring annually (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2012). Opioid-dependent (OD) women are especially vulnerable to HIV infection, with prevalence rates that are 250–1500 times higher than the national average (5–30% vs. 0.02%; Booth et al., 1993, 2000; CDC, 2011; Des Jarlais et al., 1996; Hall et al., 2008; Tempalski et al., 2009; Tyndall et al., 2002, 2003). Many of these infections are the result of risky sex with partners who are HIV-positive (National Institute on Drug Abuse [NIDA], 2012; Sánchez et al., 2002; Santibanez et al., 2006). Condoms are highly effective at protecting women from sexually transmitted HIV infection (Weller and Davis, 2002). Unfortunately, less than 20% of OD women use condoms consistently (Black et al., 2012; Magura et al., 1990; Panchanadeswaran et al., 2010). Increasing condom use among OD women would reduce their vulnerability to HIV infection, and thus is a public health priority.

Interventions aimed at increasing condom use among drug users generally range in intensity from a single session of HIV/AIDS education to multiple sessions of risk reduction counseling and/or skills building (e.g., Booth et al., 2011; Cottler et al., 1998; St. Lawrence et al., 1995; Tross et al., 2008; Wechsberg et al., 2004). Although these interventions can produce substantial increases in knowledge/skills, increases in actual condom use are modest (Campbell et al., 2011; Meader et al., 2010; Prendergast et al., 2001; Semaan et al., 2002; Tross et al., 2008). The same is true for interventions targeting OD women specifically (e.g., Tross et al., 2008), suggesting that deficits in risk reduction knowledge/skills do not fully account for the high rates sexual HIV risk behavior observed among OD women.

The decision-making processes that influence OD women to continue having risky unprotected sex in spite of gaining the knowledge/skills to reduce these risks warrant further investigation. One potential explanation is delay discounting, i.e., the observation that a consequence’s ability to control behavior decreases as the delay to its occurrence increases. Under many circumstances, unprotected sex is a behavior that offers immediate reinforcement coupled with a risk of delayed punishment (e.g., HIV/STI infection, unintended pregnancy). In situations where two people wish to have sex and a condom is immediately available, using the condom can dramatically reduce the risk of punishment while still allowing for immediate reinforcement. In situations where a condom is not immediately available, the reinforcement offered by condom-protected sex is delayed by the amount of time it would take to acquire a condom, while the reinforcement offered by unprotected sex remains immediate. If the delay to acquiring a condom increases, presumably the subjective value of condom-protected sex decreases relative to the value of immediate unprotected sex. Thus, individuals who discount delayed consequences at a steep rate may be more likely to engage in risky unprotected sex in circumstances where a condom is not immediately available. The extensive literature linking delay discounting and substance use disorders/other problem behaviors provides compelling rationale to examine discounting as a potential mechanism that underlies risky sexual behavior among OD women.

Madden et al. (1997) first demonstrated that OD individuals discount the value of delayed hypothetical monetary rewards significantly more steeply than non-drug-using controls. Subsequent studies demonstrated that cigarette smokers, alcoholics, and cocaine users also discount monetary rewards more steeply than non-users (e.g., Bickel et al., 1999; Coffey et al., 2003; Heil et al., 2006; Johnson et al., 2007; Petry, 2001). The external validity of these studies is bolstered by evidence that discounting is consistent across real and hypothetical rewards among substance users (i.e., cigarette smokers; Baker et al., 2003; Lawyer et al., 2011; Johnson et al., 2007) and non-users (e.g., Johnson and Bickel, 2002; Madden et al., 2003), and that steeper discounting of hypothetical rewards is associated with higher rates of hypothetical and real-world risk behavior (Odum et al., 2000; Reimers et al., 2008). However, the literature on relations between discounting and self-report measures of impulsivity, such as the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (BIS) is mixed; some studies have shown small but significant correlations (e.g., de Wit et al., 2007; Kirby and Petry, 2004; Kirby et al., 1999; Mitchell, 1999), while others have shown no correlation (e.g., Dom et al., 2006; Reynolds et al., 2006).

While measuring preferences between receiving smaller, immediate vs. larger, delayed monetary rewards has proven utility, it is important to remember that real-world choices between immediate and delayed outcomes involve a variety of reinforcers other than money. A more complete understanding of discounting may result from evaluating preferences between alternatives involving different commodities or more complicated tradeoffs. Tasks that assess discounting of other reinforcers, including drugs (e.g., Coffey et al., 2003; Field et al., 2006; Giordano et al., 2002; Madden et al., 1997), food (Odum et al., 2006; Rasmussen et al., 2010), sex (Jarmolowicz et al., 2013; Lawyer et al., 2010), and, more specifically, condom-protected sex (Johnson and Bruner, 2012, 2013) have been developed to better evaluate how delay influences choice in specific contexts.

The first studies examining delay discounting of condom-protected sex (Johnson and Bruner, 2012, 2013) administered the novel Sexual Discounting Task (SDT) to cocaine-dependent participants. These studies demonstrated that discounting of condom-protected sex among this group is orderly, reliable, and well-fit by two-parameter hyperbolic discounting functions (i.e., V=A/(1+kD)s). Furthermore, choices on the SDT appeared to be sensitive to partner characteristics that may influence real-world decisions to use condoms; participants discounted condom-protected sex more steeply for partners they most wanted to have sex with (MOST SEX) vs. partners they least wanted to have sex with (LEAST SEX) and for partners they thought were least likely to have a sexually transmitted infection (LEAST STI) vs. partners they thought were most likely to have a sexually transmitted infection (MOST STI). Finally, steeper discounting was associated with higher self-reported rates of real-world risky sexual behavior, suggesting the SDT has external validity.

Considering the results of Johnson and Bruner (2012, 2013) in the context of the discounting literature in general prompts the following three questions: 1) does discounting of condom-protected sex differ between drug users and non-users in the same manner as discounting of other commodities, such as money?; 2) does partner desirability and perceived STI risk influence discounting of condom-protected sex among OD women/non-drug-using women in the same manner as cocaine-dependent men/women?; and 3) is discounting of condom-protected sex related to self-report measures of impulsivity? The present study addressed these questions by: 1) comparing discounting of condom-protected sex and money between OD women and non-drug using control women. We hypothesized that OD women would discount both condom-protected sex and money significantly more steeply than non-drugusing controls, 2) comparing discounting of condom-protected sex between paired partner conditions (i.e., MOST SEX vs. LEAST SEX and LEAST STI vs. MOST STI). We hypothesized that OD women/non-drug-using women would show the same sensitivity to partner characteristics as the cocaine-dependent men/women described in previous reports, and 3) examining relations between discounting of condom-protected sex, discounting of money, and scores on the BIS-11. We hypothesized that steeper discounting of condom-protected sex may be associated with greater discounting of money and higher scores (greater impulsivity) on the BIS-11.

2. METHODS

2.1. Participants

2.1.1. OD women

OD women (n=27) completed all study related instruments during an initial screening visit for a clinical trial examining an intervention to promote prescription contraceptive use among OD women. OD women were included in the present study if they 1) were 18 years of age or older, 2) were actively receiving opioid maintenance treatment (methadone or buprenorphine) for at least 30 days, 3) reported having heterosexual intercourse at least once during the prior 3 months, and 4) were not incarcerated. Women who completed this screening visit were compensated $35.

2.1.2. Control women

Control women (n=33) were recruited from the greater Burlington, VT area via flyers distributed throughout the community (bus stops, health centers, grocery stores, shopping malls, etc.) and advertisements placed on the online classifieds site Craigslist. Controls completed an eligibility screen over the phone prior to study enrollment, and were offered the opportunity to participate if they 1) were 18 years of age or older, 2) reported no illicit drug use or substance abuse treatment during the past 30 days, 3) reported having heterosexual intercourse at least once during the prior 3 months, and 4) were not incarcerated. All study assessments were completed during a single one-hour visit, and control participants were compensated $40. Control participants received $5 more than OD participants to cover travel to the study site (OD participants regularly attended the opioid maintenance treatment clinic in the building housing the study site).

2.2. Assessments

2.2.1. Demographic characteristics and sexual HIV risk behavior

Participants completed a questionnaire that collected information about demographics and recent sexual HIV risk behavior. The risk behavior component contained nine items from the Risk Assessment Battery (Metzger et al., 1993). These items assessed the frequency of behaviors related to sexual HIV transmission (e.g., having unprotected sex, having multiple sexual partners, trading sex for drugs or money, etc.) during the prior six months.

2.2.2. Delay discounting

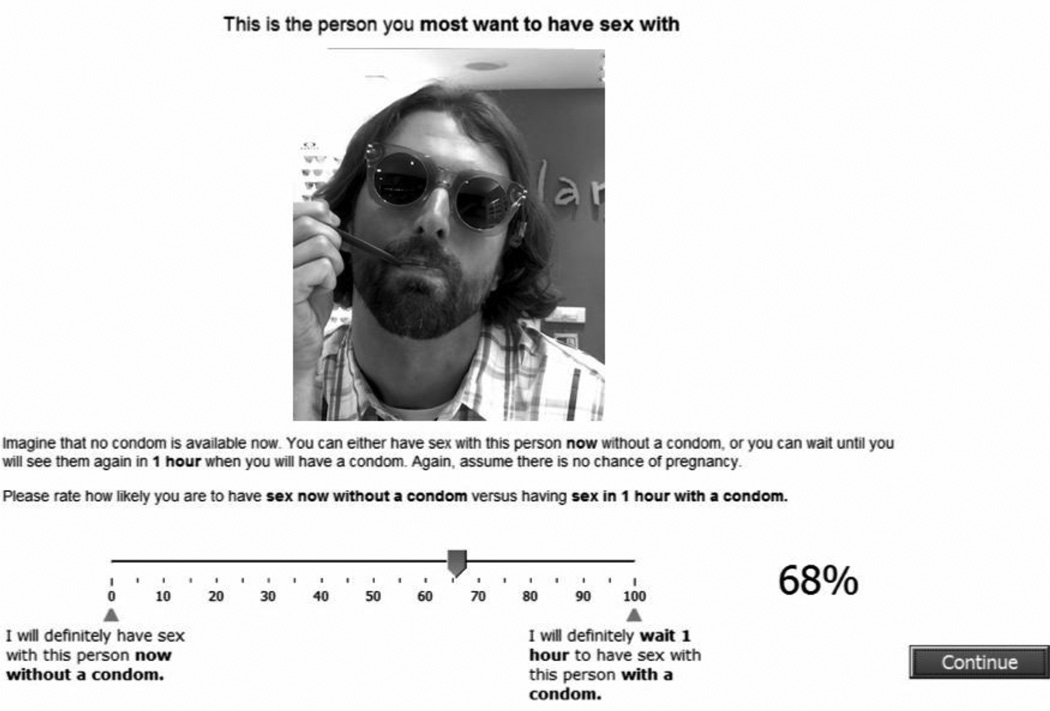

Discounting of condom-protected sex was assessed using the SDT. Participants began the task by viewing 60 photographs of a diverse sample of individuals on a laptop computer. Participants selected pictures of individuals they would consider having sex with, assuming that they just met the person, liked their personality, were not currently in a committed relationship, and that sex carried no risk of pregnancy. From selected photographs, participants chose MOST SEX, LEAST SEX, LEAST STI, and MOST STI partners. Participants could choose the same partner for more than one partner condition, but not within the same pair (i.e., a single partner could be both MOST SEX and LEAST STI, but could not be both MOST SEX and LEAST SEX). For each of these four partners, participants used a visual analog scale (VAS; from 0 to 100%) to rate their likelihood of: 1) having unprotected sex immediately vs. having condom-protected sex immediately (0-delay trial) and 2) having unprotected sex immediately vs. waiting a delay (i.e., 1 hour, 3 hours, 6 hours, 1 day, 1 week, 1 month, and 3 months, in 7 separate trials always presented in this order) to have condom-protected sex. An example 1-hour delay trial is shown in Figure 1. The relative difference between a participant’s 0-delay trial likelihood value and the value for a given delay trial indicates the degree to which they discounted the value of condom-protected sex as a function of that delay.

Figure 1.

Example delay trial (1 hour) from the Sexual Discounting Task showing the hypothetical sexual partner selected by a study participant for the MOST SEX partner condition and the corresponding visual analog scale (VAS) below. The arrow above the VAS and the percentage value to the right indicate the participant’s selected likelihood value (68%).

Discounting of money was assessed using a computerized monetary discounting task (MDT), a discrete-trial choice procedure where participants make hypothetical choices between receiving a large reward ($1000) after various delays vs. receiving a smaller reward ($20–980) immediately (Johnson and Bickel, 2002). The MDT contains seven blocks of trials, one block for each delay (1 day, 1 week, 1 month, 6 months, 1 year, 5 years, and 25 years), presented in ascending or descending order (counterbalanced within groups). For each delay, the MDT program automatically adjusted the value of the smaller reward based on the participant’s responses until an indifference point was found. This was repeated until indifference points were established for all 7 delays.

The orderliness of SDT and MDT data were assessed using criteria described previously (Johnson and Bruner, 2012; Johnson and Bickel, 2008). If any SDT delay value was higher than the preceding value by more than 20% of the scale then the data for that partner condition were considered nonsystematic. If any MDT indifference point was greater than the preceding indifference point by a magnitude greater than 20% of the larger later reward (i.e., $1000) data were considered nonsystematic. Nonsystematic data were excluded from between-subject tests on an individual basis and from within-subjects tests on a pairwise basis (e.g., MOST SEX vs. LEAST SEX). For each SDT partner condition, values from delay trials were standardized (i.e., divided by their respective 0-delay values) in order to isolate the effect of delay on choices between unprotected vs. condom-protected sex. If participants’ 0-delay values for a partner conditions were zero (i.e., the participant indicated a 0% likelihood of using an immediately available condom) the delay trial values from that partner condition were excluded from further analyses. MDT indifference points were expressed as a percent of the delayed monetary amount (i.e., divided by 1,000). In order to obtain an aggregate measure of discounting, area under the curve (AUC) was computed from each subject’s standardized SDT and MDT data per Myerson et al. (2001). 0-delay and AUC values were expressed as a proportion of the maximum possible value to limit their range from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating increased likelihood of condom use/less discounting.

2.2.3. Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (BIS-11)

The BIS-11 is a 30-item self-report questionnaire designed to measure impulsive behavior/personality traits. It has demonstrated reliability and validity, and has been used previously with OD individuals (Hanson et al., 2008; Huang et al., 2013; Marino et al., 2013; Neilsen et al., 2012; Patton et al., 1995). Individual BIS-11 items contain statements that describe common impulsive or non-impulsive behaviors/preferences (e.g., “I do things without thinking,” “I plan tasks carefully”). For each item, participants are asked to rate the frequency at which they emit the given behavior/preference using a 4-point scale (1 = Rarely/Never, 2 = Occasionally, 3 = Often, and 4 = Almost Always/Always). Total score on the BIS-11 is calculated as the sum of items (items related to non-impulsive behaviors are reverse scored), with higher scores indicating greater impulsivity (Patton et al., 1995). The BIS-11 also contains three second-order factor subscales: 1) the attentional subscale, which contains eight items that assess task-focus and intrusive/racing thoughts; 2) the motor subscale, which contains eleven items that assess tendency to act on the spur of the moment and consistency of lifestyle; and 3) the nonplanning subscale, which contains eleven items that assess careful thinking/planning and enjoyment of challenging mental tasks.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

2.3.1 Orderliness of discounting data

Root mean square error (RMSE) was calculated to examine how well systematic SDT and MDT data were fit by a two-parameter hyperbolic discounting function, V=A/(1+kD)s. In this function, V is the present value of the future reward, A is its amount, D is the delay to its receipt, k is a parameter governing the rate of decrease in value, and s is a nonlinear scaling parameter that modulates k (Green et al., 1994).

2.3.2. Comparisons between OD women and controls

Demographics and sexual HIV risk behaviors were compared between OD women and controls using t-tests for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables. The distributions of 0-delay and AUC values were skewed, therefore statistical comparisons were based on robust non-parametric generalized rank tests using two-way repeated measures analyses of variance performed on rank transformed data (see Conover and Iman, 1981). The two factors represented group (OD women vs. controls), and partner condition (MOST SEX/LEAST SEX or LEAST STI/MOST STI). Separate analyses were done for the two pairs of partner conditions to avoid comparing data from the same partner across conditions. One-way ANOVA performed on rank transformed data was used to compare standardized MDT AUC values between OD women and controls. This procedure is asymptotically equivalent to performing a Wilcoxon rank sum test. Subsequently, this procedure was replicated with smoking status included as a covariate to determine if OD women and controls differed after accounting for differences in smoking.

2.3.3. Associations among impulsivity measures

Spearman’s rank correlations were used to examine relations between the SDT AUC values and 1) MDT AUC values, 2) BIS-11 total scores, and 3) scores on BIS-11 attentional, motor, and nonplanning subscales among the full study sample. These analyses allowed us to examine if discounting of condom-protected sex was related to discounting of money and/or self-reported impulsive behavior/personality traits. Analyses were performed using SPSS statistical software, version 21 (IBM Corp, 2012) and SAS statistical software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Statistical significance was determined based on α=.05.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Demographics characteristics and HIV risk behavior

Demographic characteristics and sexual HIV risk behavior among study completers are summarized in Table 1. Over a third (37%) of OD women reported a history of injection drug use, and about three-quarters (74%) reported illicit drug use in the past 30 days, mainly of cannabis, prescription opioids, and/or cocaine. OD women averaged significantly fewer years of education (M = 12.2 [SD = 1.3] vs. M = 14.1 [SD = 2.3]), and were more likely to be unemployed (93% vs. 21%), have children (85% vs. 49%), smoke cigarettes (82% vs. 21%), and have been tested for HIV (96% vs. 74%) compared to control women. Regression analyses using the full study sample demonstrated that none of these factors predicted 0-delay or AUC values for any of the four SDT partner conditions, therefore, we did not control for them statistically in subsequent SDT analyses. Smoking status predicted AUC of money discounting and was thus entered as a covariate in MDT analyses.

Table 1.

Demographic and baseline characteristics of opioid-dependent (OD) women (n=27) and non-drug-using control women (n=33). Values are percentage of sample reporting unless otherwise indicated. Significant differences between OD women and controls are indicated by p values <.05.

| Characteristic | Opioid-Dependent (n=27) | Control (n=33) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age (years) (mean ± SD) | 29.7(4.6) | 32.0(12) | .36 |

| Race (white, non-hispanic) | 76 | 82 | .41 |

| Marital status (married) | 19 | 27 | .31 |

| Education (years) (mean ± SD) | 12.2(1.3) | 14.1(2.3) | <.01 |

| Employed (including full-time student) | 7 | 79 | <.01 |

| Have children | 85 | 49 | <.01 |

| Smoke cigarettes | 82 | 21 | <.01 |

| Risk Assessment Battery (RAB) | |||

| Sexual History | |||

| More than one male sexual partner in past six months | 16 | 15 | .60 |

| Traded sex for drugs/money in past six months | 12 | 0 | .08 |

| Condom Use | |||

| Never | 62 | 67 | |

| Sometimes | 27 | 12 | |

| Most of the time | 11 | 12 | |

| All of the time | 4 | 9 | .45 |

| HIV | |||

| Worried about getting HIV | 31 | 39 | .34 |

| Ever been tested for HIV | 96 | 73 | .03 |

| Tested for HIV in the past 12 months | 54 | 27 | .06 |

| Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (BIS-11) | |||

| Total Score (mean ± SD) | 72.6 (9.4) | 60.8 (11.4) | <.01 |

| Attentional subscale (mean ± SD) | 17.8 (4.1) | 15.6 (4.0) | .05 |

| Motor subscale (mean ± SD) | 25.9 (4.3) | 22.2 (4.5) | <.01 |

| Nonplanning subscale (mean ± SD) | 28.9 (3.2) | 23.1 (4.3) | <.01 |

Note. Significance based on chi-square tests for categorical variables and t-tests for continuous variables.

3.2. Orderliness of discounting data

The vast majority of SDT (85%) and MDT (95%) data met previously defined criteria for being systematic and were included in discounting analyses (sample sizes for each comparison are shown in ANOVA results below). Systematic discounting data were well-fit by the two-parameter hyperbolic discounting function (mean RMSE < 0.1 for all four SDT partner conditions and MDT).

3.3. Comparisons between OD women and controls

3.3.1 Likelihood of using Immediately available condoms (0-delay)

Robust two-way ANOVA on the ranks comparing 0-delay values indicated that the likelihood of using an immediately available condom with MOST SEX/LEAST SEX partners did not differ between OD women and controls [F(1,54)=0.04, p=.84], nor did it differ between MOST SEX and LEAST SEX partner conditions [F(1,54)=0.16, p=.69]. Additionally, there was no evidence of a group by condition interaction [F(1,54)=0.22, p=.64]. Median 0-delay likelihood values were 0.99 for both OD and control women for MOST SEX/LEAST SEX pairs and 0.96 vs. 0.99 for MOST SEX vs. LEAST SEX partners, respectively.

Two-way ANOVA on the ranks comparing 0-delay values between OD women and controls indicated that the likelihood of using an immediately available condom with LEAST STI/MOST STI partners did not significantly differ between OD women and controls [F(1,54)=3.22, p=.08]. Median 0-delay values were 0.99 for OD women vs. 1.00 for controls. There was a significant effect of partner condition; women were more likely to use an immediately available condom with MOST STI partners compared to LEAST STI partners [F(1,54)=8.10, p<.01]. This shift in the distribution between partner conditions was evident in the first quartile, which was 0.91 for MOST STI condition and 0.50 for LEAST STI condition. There was no evidence of a partner condition by group interaction [F(1,54)=0.29, p=.60].

3.3.2 Discounting of condom-protected sex

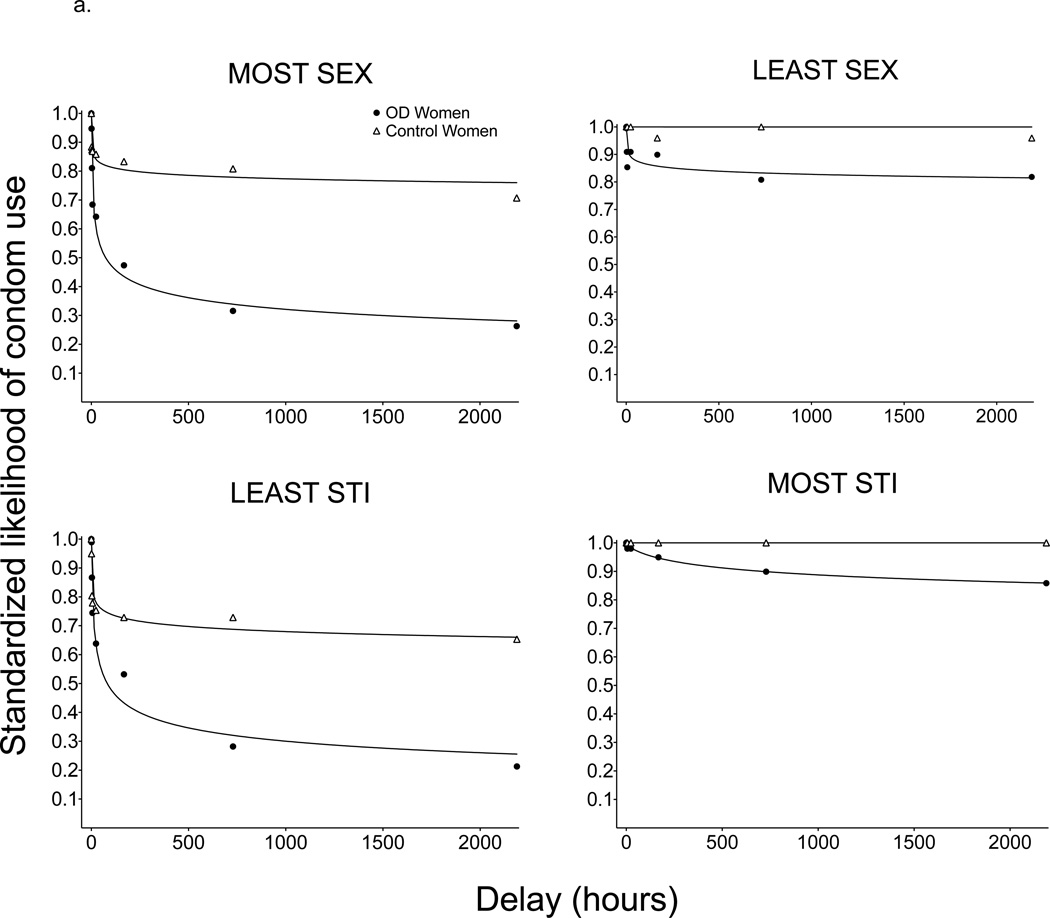

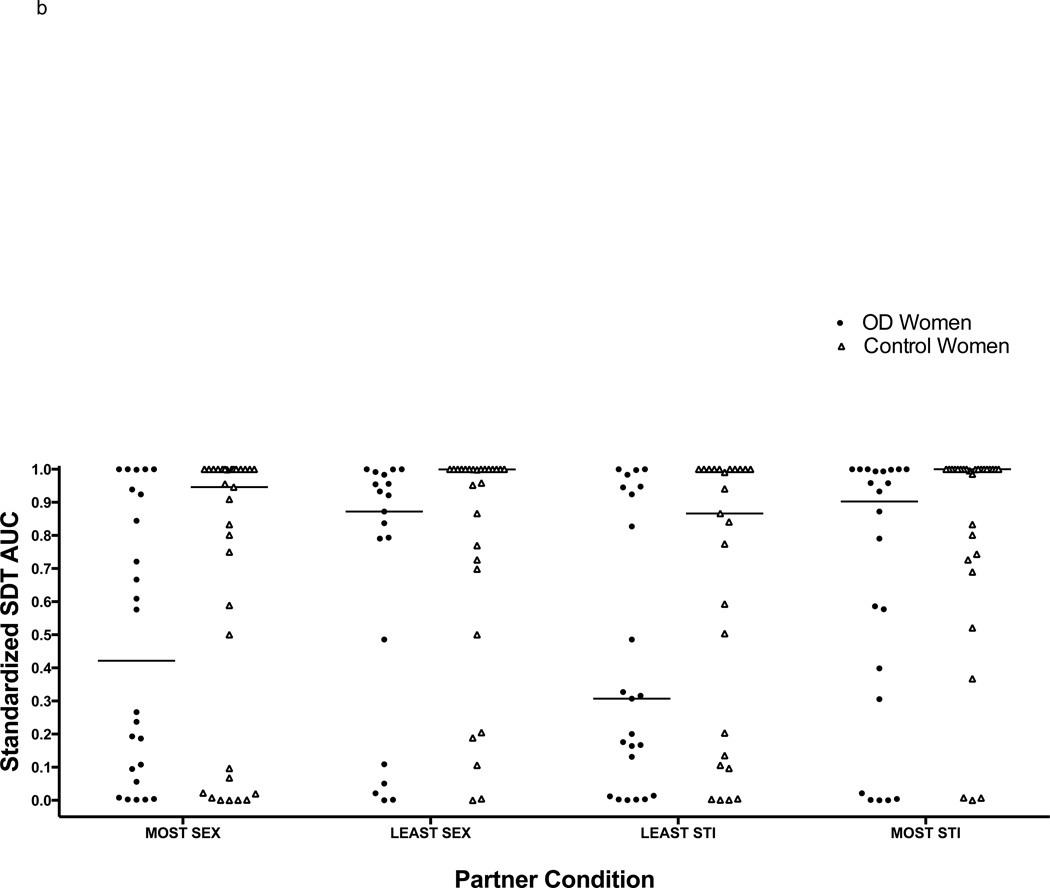

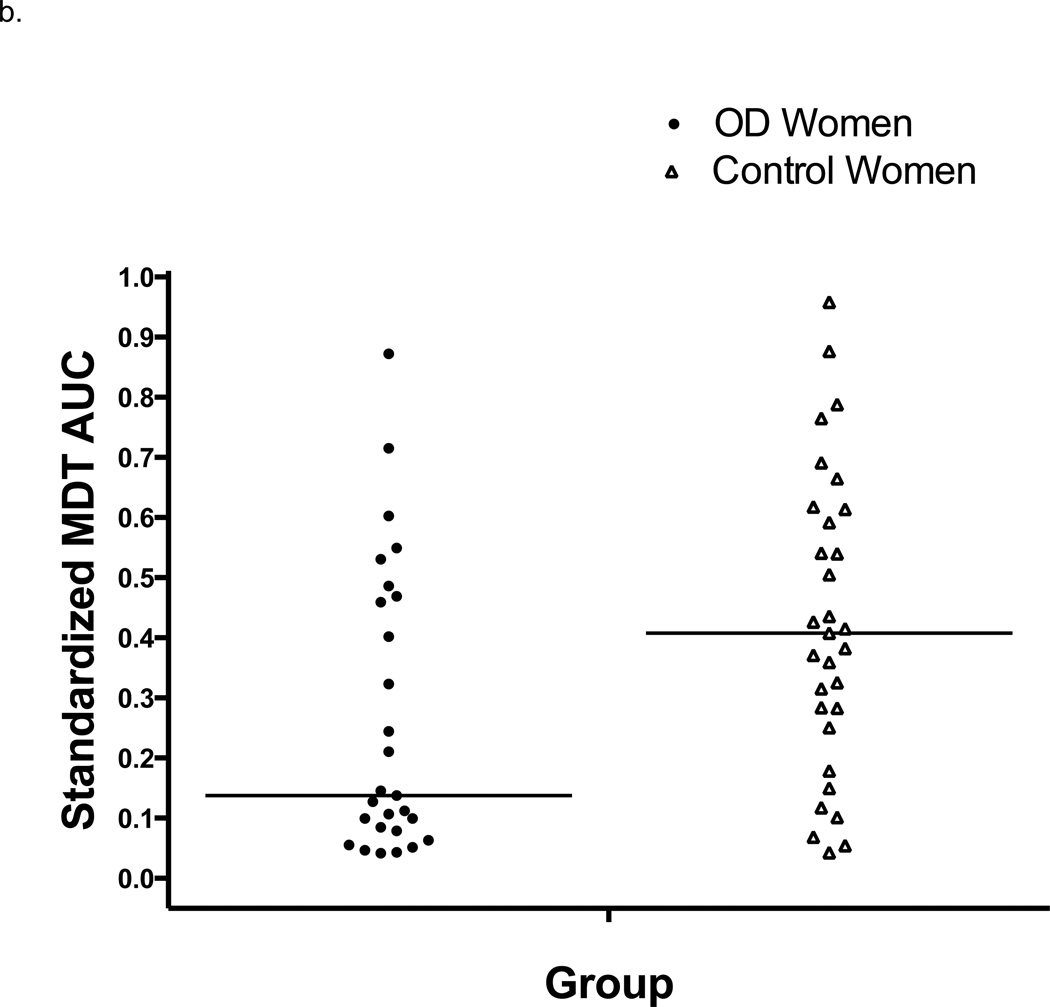

Best-fit two-parameter hyperbolic functions and median SDT likelihood values are displayed in Figure 2a for each group and partner condition. Individual participant’s AUC values from each partner condition and corresponding group medians are plotted in Figure 2b. Two-way ANOVA on rank transformed data comparing AUC values between OD women and controls for MOST SEX/LEAST SEX partner conditions indicated that OD women discounted condom-protected sex more steeply than controls for MOST SEX/LEAST SEX partners [F(1,54)=4.11, p=.048]. Median standardized AUC values were 0.72 for OD women compared to 0.98 for controls. There was no significant effect of partner condition [F(1,43)=2.23, p=.14]. Median AUC values were 0.75 for MOST SEX vs. 0.95 for LEAST SEX partner conditions. There was no evidence of a group by condition interaction [F(1,43)=0.12, p=.83].

Figure 2.

a. Median standardized likelihood values for each SDT partner condition with best-fit two-parameter hyperbolic functions (V=A/(1+kD)s) for OD women (n=33) and non-drug-using control women (n=27).

b. Individual participant’s standardized area under the curve (AUC) values from the SDT organized according to partner condition (MOST SEX, LEAST SEX, LEAST STI, and MOST STI) and group (OD women vs. non-drug-using controls). Horizontal lines indicate median AUC values for each partner condition/group. Two-way ANOVA indicated that OD women discounted condom-protected sex more steeply than controls for MOST SEX/LEAST SEX partners [F(1,54)=4.11, p=.048] and for LEAST STI/MOST STI partners [F(1,54)=7.50, p<.01]. Overall, women discounted condom-protected sex more steeply for LEAST STI partners than for MOST STI partners [F(1,43)=4.87, p=.03]. There were no overall differences between MOST SEX and LEAST SEX partners [F(1,43)=2.23, p=.14].

Two-way ANOVA comparing AUC values across groups and LEAST STI/MOST STI partner conditions resulted in significant main effects for both factors. OD women discounted condom-protected sex more steeply than controls [F(1,54)=7.50, p<.01] and women discounted condom protected sex more steeply for LEAST STI partners than for MOST STI partners [F(1,43)=4.87, p=.03]. Median AUC values were 0.87 for OD women vs. 1.00 for controls and 0.55 for LEAST STI vs. 0.99 for MOST STI partner conditions. There was no evidence of a group by partner interaction [F(1,43)=0.12, p=.73].

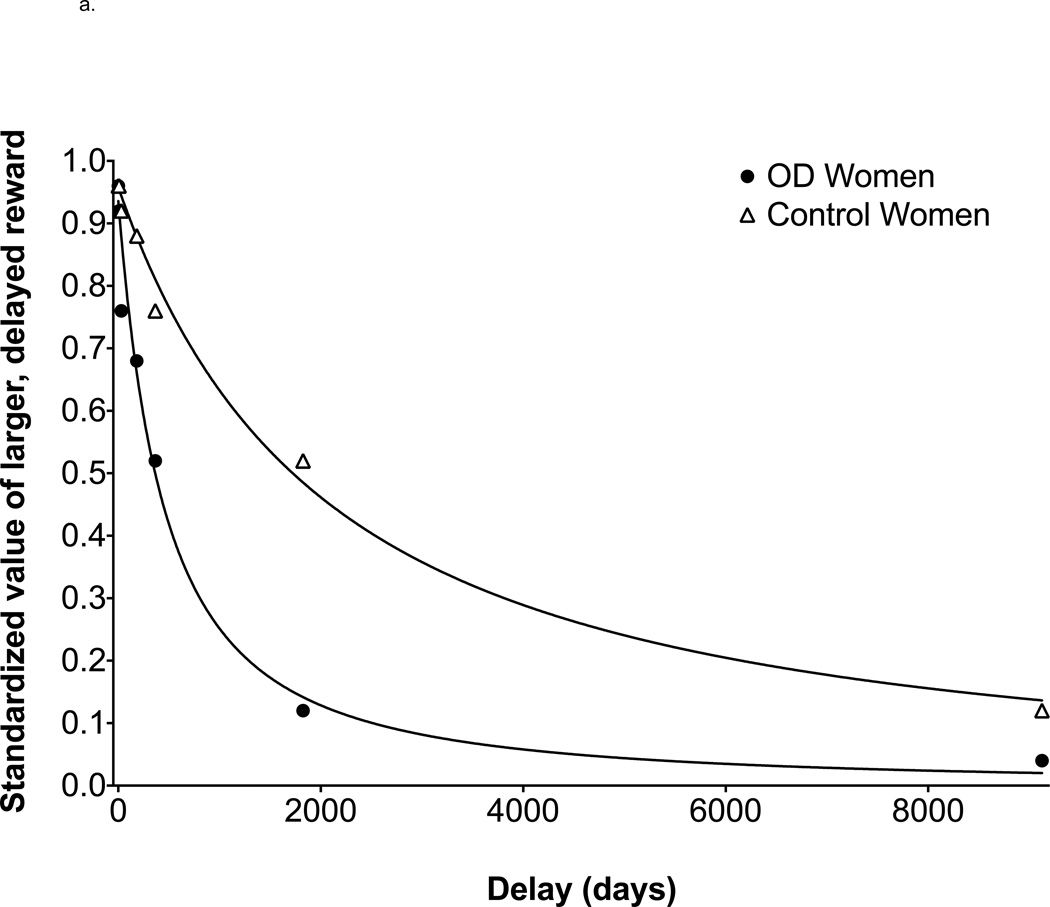

3.3.3. Discounting of money

Best-fit two-parameter hyperbolic functions and median MDT likelihood values are displayed in Figure 3a for each group. Individual participant’s standardized AUC values and corresponding group medians are plotted in Figure 3b. One-way ANOVA on the ranks indicated that OD women discounted the value of money more steeply than control women [F(1,55)=6.66, p=.012] with median AUC values of 0.14 vs. 0.42. Smoking status, which was significantly different across groups, was also a significant predictor of AUC [F(1,55)=8.57, p=.005]. Robust analysis of covariance based on ranks indicated that observed differences in money discounting between OD women and controls were no longer significant after controlling for smoking status [F(1,54)=1.07, p=.30].

Figure 3.

a. Median standardized indifference points from the MDT with best-fit two-parameter hyperbolic functions (V=A/(1+kD)s) for OD women (n=33) and non-drug-using control women (n=27).

b. Individual participant’s standardized area under the curve (AUC) values from the MDT organized by group (OD women vs. non-drug-using controls). Horizontal lines indicate median AUC values for each group. One-way ANOVA on the ranks indicated that OD women discounted the value of money more steeply than control women [F(1,55)=6.66, p=.012].

3.4. Associations among impulsivity measures

Spearman’s rank correlations between AUC of SDT data, AUC of MDT data, BIS-11 total scores, and scores on each BIS-11 subscale are displayed in Table 2. There were no significant associations between discounting of condom-protected sex and discounting of money. However, steeper discounting with MOST SEX, LEAST SEX, and MOST STI partners was associated with higher total scores on the BIS-11 and with higher scores on at least one of the three BIS-11 subscales.

Table 2.

Spearman’s rank correlations between standardized AUC values for each SDT partner condition, AUC of MDT data, BIS-11 total scores, and BIS-11 subscale scores among the full study sample (N=60). Significant correlations (p<.05) are shown in bold.

| Sexual Discounting Task Partner Condition |

Money Discounting AUC |

BIS-11 Total Score |

BIS-11 Attentional Subscale |

BIS-11 Motor Subscale |

BIS-11 Nonplanning Subscale |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MOST SEX AUC | .03 | −.33 | −.24 | −.33 | −.24 |

| LEAST SEX AUC | −.06 | −.40 | −.47 | −.22 | −.41 |

| LEAST STI AUC | −.15 | −.24 | −.20 | −.19 | −.26 |

| MOST STI AUC | .12 | −.31 | −.33 | −.16 | −.35 |

4. DISCUSSION

The present report describes three findings. First, OD women discounted condomprotected sex and money significantly more steeply than non-drug-using women. Second, both the likelihood of using an immediately available condom and discounting of condom-protected sex were influenced by women’s perceived likelihood of partners having a sexually transmitted infection. Third, discounting of condom-protected sex was correlated with BIS-11 total scores and subscale scores, but not with discounting of money.

OD women discounted the value of condom-protected sex more steeply than controls in both MOST SEX/LEAST SEX and LEAST STI/MOST STI paired partner conditions. These observations suggest that OD women may be less likely than non-drug-using women to delay sex in order to acquire and use a condom if one is not readily available, regardless of partner desirability or perceived riskiness. This tendency may lead to increases in unprotected sex and contribute to the higher rates of sexually transmitted HIV infection observed among OD women. Consistent with previous reports (e.g., Madden et al., 1997), OD women discounted money more steeply than non-drug-using women. Taken as a whole, this report demonstrates OD women exhibit decision-making that is more biased toward immediate outcomes than non-drug using women, and may partly explain why interventions that substantially increase risk reduction knowledge/skills produce comparably modest reductions in risk behavior.

Discounting of condom-protected sex among participants appeared to be sensitive to perceived risk of contracting a sexually transmitted infection. Overall, women discounted condom-protected sex more steeply for partners they perceived to be lowest risk (LEAST STI) vs. those they perceived to be highest risk (MOST STI). These findings are consistent with previous observations among cocaine-dependent individuals (i.e., Johnson and Bruner, 2012, 2013), suggesting that the influence of perceived risk on discounting of condom-protected sex appears to generalize across at least four different groups (cocaine-dependent men, cocaine-dependent women, opioid-dependent women, and non-drug-using women). Differences between MOST SEX and LEAST SEX partner conditions were not significant (p=.14), contrasting the previous reports by Johnson and Bruner.

Greater discounting of condom-protected sex with MOST SEX, LEAST SEX, and LEAST STI partners was associated with higher total scores on the BIS-11. Greater discounting with MOST SEX partners was associated with higher scores on the motor subscale, and greater discounting with LEAST SEX and MOST STI partners was associated higher scores on both attentional and nonplanning subscales. Relations between other partner conditions/subscales appeared to trend in the same direction, but did not reach statistical significance. Items on the BIS-11 query the respondent about their ability to focus on tasks at hand, their tendency to consider the consequences of their behavior before acting, and their ability to think about and plan future behavior carefully. The results of the present study suggest that steeper discounting of condom-protected sex may be related to deficits in these areas (e.g., attending to and considering the potential consequences of unprotected sex, planning ahead to have condoms in situations where they may be needed, etc.). Interestingly, discounting of condom-protected sex and discounting of money were not correlated, and discounting of condom-protected sex was not related to cigarette smoking (discounting of money was). These findings suggest that although discounting of various commodities differs between OD individuals and non-drug-users in the same manner, they may do so independently.

The findings of this study must be considered in light of four limitations. First, drug abstinence was not biochemically-verified among control women, thus, we cannot rule out the possibility that some may have been drug users. Second, there were differences between OD women and controls on some demographic variables known to influence discounting (education, smoking status). Although these variables did not significantly influence discounting of condom-protected sex in the present study, future studies may identify such relationships and need to control for differences statistically. Third, the SDT involves hypothetical choices and consequences; it is possible that choices made on the SDT do not reflect participants’ actual behavior if the choices/consequences were real. Experimental evidence suggests that discounting is consistent across real and hypothetical rewards (e.g., Johnson and Bickel, 2002; Madden et al., 2003), and the results of Johnson and Bruner (2012, 2013) demonstrate relations between discounting of condom-protected sex and real-world sexual behavior. Although we did not examine these relations in the present study, they are unlikely to differ substantially from previous observations given the consistency of our other findings. Fourth, individual differences in perceived risks of unprotected vs. protected sex may have influenced results. Future studies should examine relationships between sexual risk perception and discounting.

The present report summarizes the first study to compare delay discounting of condom-protected sex between drug users and non-users, and the first study to examine associations between discounting of condom-protected sex and a self-report measure of impulsivity, the BIS- 11. The results suggest that greater discounting of delayed condom-protected sex may partially explain the elevated rates of risky sexual behavior commonly observed among OD women, and that discounting may limit the efficacy of existing interventions aimed at reducing HIV risk behavior. This report also builds on prior studies (e.g., Johnson and Bruner, 2012, 2013; Rasmussen et al., 2010) by providing additional evidence that discounting is partially domainspecific. These observations suggest that tasks like the SDT, which measures decision-making patterns using stimuli and choices closely related to real-world risky behavior may prove to be more informative than generalized measures of impulsivity in evaluating HIV risk. Further studies that examine relationships between discounting and risky sexual behaviors are warranted.

Highlights.

-

.

Delay discounting of sexual rewards may influence HIV risk behavior

-

.

Opioid-dependent women discounted condom-protected sex more steeply than controls

-

.

Women discounted condom-protected sex more steeply with low risk partners

-

.

Discounting of condom-protected sex was correlated with higher scores on the BIS-11

-

.

The influence of discounting on condom use is a promising measure of HIV risk.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Stephen Higgins, Stacey Sigmon, Sayamwong Hammack, and William Falls for their assistance with study design, as well as Betsy Bahrenburg and Patricia Livingston for their assistance with data collection.

Role of Funding Source

Supported by grants R34DA030534 & T32DA07242 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). The NIDA had no further role in study design, in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data; in the writing of this report, or in the decision to submit this paper for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributors

Authors Evan Herrmann, Dennis Hand, and Sarah Heil designed the study and developed the protocol. Evan Herrmann, Dennis Hand, Matthew Johnson, and Sarah Heil managed literature searches and summaries of previous work. Evan Herrmann, Dennis Hand, and Gary Badger undertook the statistical analysis. Evan Herrmann, Dennis Hand, Matthew Johnson, Gary Badger, and Sarah Heil wrote the final draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- Baker F, Johnson MW, Bickel WK. Delay discounting in current and never-before cigarette smokers: similarities and differences across commodity, sign, and magnitude. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2003;112:382–392. doi: 10.1037/0021-843x.112.3.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Odum A, Madden GJ. Impulsivity and cigarette smoking: delay discounting in current, never, and ex-smokers. Psychopharmacology. 1999;146:447–454. doi: 10.1007/pl00005490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black KI, Stephens C, Haber PS, Lintzeris N. Unplanned pregnancy and contraceptive use in women attending drug treatment services. Aust. N. Z. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2012;52:146–150. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828X.2012.01413.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth RE, Campbell BK, Mikulich-Gilbertson SK, Tillotson CJ, Choi D, Robinson J, Calsyn DA, Mandler RN, Jenkins LM, Thompson LL, Dempsey CL, Liepman MR, McCarty D. Reducing HIV-related risk behaviors among injection drug users in residential detoxification. AIDS Behav. 2011;15:30–44. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9751-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth RE, Kwiatkowski CF, Chitwood DD. Sex related HIV risk behaviors: differential risks among injection drug users, crack smokers, and injection drug users who smoke crack. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2000;58:219–226. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00094-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth RE, Watters JK, Chitwood DD. HIV risk-related sex behaviors among injection drug users, crack smokers, and injection drug users who smoke crack. Am. J. Public Health. 1993;83:1144–8. doi: 10.2105/ajph.83.8.1144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell AN, Tross S, Hu MC, Pavlicova M, Kenney J, Nunes EV. Female condom skill and attitude: results from a NIDA Clinical Trials Network gender-specific HIV risk reduction study. AIDS Educ. Prev. 2011;23:329–340. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2011.23.4.329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV/AIDS Among Women. 2011 http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/women/index.htm.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV in the United States: At A Glance. 2012 http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/resources/factsheets/us.htm.

- Coffey SF, Gudleski GD, Saladin ME, Brady KT. Impulsivity and rapid discounting of delayed hypothetical rewards in cocaine-dependent individuals. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2003;11:18–25. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.11.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conover WJ, Iman RL. Rank transformations as a bridge between parametric and nonparametric statistics. Am. Stat. 1981;35:124–129. [Google Scholar]

- Cottler LB, Compton WM, Abdallah AB, Cunningham-Williams R, Abram F, Fichtenbaum C, Dotson W. Peer-delivered interventions reduce HIV risk behaviors among out-of-treatment drug abusers. Public Health Rep. 1998;113(Suppl. 1):s31–s41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wit H, Flory JD, Acheson A, McCloskey M, Manuck SB. IQ and nonplanning impulsivity are independently associated with delay discounting in middle-aged adults. Pers. Ind. Diff. 2007;42:111–121. [Google Scholar]

- Des Jarlais DC, Marmor M, Paone D, Titus S, Shi Q, Perlis T, Jose B, Friedman SR. HIV incidence among injecting drug users in New York City syringe-exchange programmes. Lancet. 1996;348:987–991. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)02536-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dom G, D’haene P, Hulstijn W, Sabbe B. Impulsivity in abstinent early- and late- onset alcoholics: differences in self- report measures and a discounting task. Addiction. 2006;101:50–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field M, Santarcangelo M, Sumnall H, Goudie A, Cole J. Delay discounting and the behavioural economics of cigarette purchases in smokers: the effects of nicotine deprivation. Psychopharmacol. 2006;186:255–263. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0385-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giordano LA, Bickel WK, Loewenstein G, Jacobs EA, Marsch L, Badger GJ. Mild opioid deprivation increases the degree that opioid-dependent outpatients discount delayed heroin and money. Psychopharmacol. 2002;163:174–182. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1159-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green L, Fry AF, Myerson J. Discounting of delayed rewards: a life-span comparison. Psych. Sci. 1994;5:33–36. [Google Scholar]

- Hall HI, Song R, Rhodes P, Prejean J, An Q, Lee LM, Karon J, Brookmeyer, Kaplan EH, McKenna MT, Janssen RS. Estimation of HIV incidence in the United States. JAMA. 2008;300:520–529. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.5.520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson KL, Luciana M, Sullwold K. Reward-related decision-making deficits and elevated impulsivity among MDMA and other drug users. Drug. Alcohol Depend. 2008;96:99–110. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang CY, Li CSR, Fang SC, Wu CS, Liao DL. The reliability of the Chinese version of the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale version 11, in abstinent, opioid-dependent participants in Taiwan. J. Chin. Med. Assoc. 2013;76:289–295. doi: 10.1016/j.jcma.2013.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heil SH, Johnson MW, Higgins ST, Bickel WK. Delay discounting in currently using and currently abstinent cocaine-dependent outpatients and non-drug-using matched controls. Addict. Behav. 2006;31:1290–1294. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 21.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.; Released 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Jarmolowicz DP, Bickel WK, Gatchalian KM. Alcohol-dependent individuals discount sex at higher rates than controls. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;131:320–323. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MW, Bickel WK. Within-subject comparison of real and hypothetical money rewards in delay discounting. J. Exp. Anal. Behav. 2002;77:129–146. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2002.77-129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MW, Bickel WK. An algorithm for identifying nonsystematic delay-discounting data. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2008;16:264–274. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.16.3.264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MW, Bickel WK, Baker F. Moderate drug use and delay discounting: a comparison of heavy, light, and never smokers. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2007;15:187–194. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.15.2.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MW, Bruner NR. The Sexual Discounting Task: HIV risk behavior and the discounting of delayed sexual rewards in cocaine dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;123:15–21. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.09.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MW, Bruner NR. Test–retest reliability and gender differences in the sexual discounting task among cocaine-dependent individuals. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2013;21:277–286. doi: 10.1037/a0033071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby KN, Petry NM, Bickel WK. Heroin addicts have higher discount rates for delayed rewards than non-drug-using controls. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 1999;128:78–87. doi: 10.1037//0096-3445.128.1.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby KN, Petry NM. Heroin and cocaine abusers have higher discount rates for delayed rewards than alcoholics or non- drug- using controls. Addiction. 2004;99:461–471. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2003.00669.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawyer SR, Schoepflin F, Green R, Jenks C. Discounting of hypothetical and potentially real outcomes in nicotine-dependent and nondependent samples. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2011;19:263. doi: 10.1037/a0024141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawyer SR, Williams SA, Prihodova T, Rollins JD, Lester AC. Probability and delay discounting of hypothetical sexual outcomes. Behav. Process. 2010;84:687–692. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2010.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madden GJ, Begotka AM, Raiff BR, Kastern LL. Delay discounting of real and hypothetical rewards. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2003;11:139–145. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.11.2.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madden GJ, Petry NM, Badger GJ, Bickel WK. Impulsive and self-control choices in opioid-dependent patients and non-drug-using control patients: drug and monetary rewards. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 1997;5:256–262. doi: 10.1037//1064-1297.5.3.256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magura S, Shapiro JL, Siddiqi Q, Lipton DS. Variables influencing condom use among intravenous drug users. Am. J. Public Health. 1990;80:82–84. doi: 10.2105/ajph.80.1.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marino EN, Rosen KD, Gutierrez A, Eckmann M, Ramamurthy S, Potter JS. Impulsivity but not sensation seeking is associated with opioid analgesic misuse risk in patients with chronic pain. Addict. Behav. 2013;38:2154–2157. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metzger DS. The Risk Assessment Battery: Validity and Reliability. In: Mitchell SH, editor. Paper presented at the 6th Annual Meeting of National Cooperative Vaccine Development Group for AIDS.1993. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell SH. Measures of impulsivity in cigarette smokers and non-smokers. Psychopharmacol. 1999;146:455–464. doi: 10.1007/pl00005491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myerson J, Green L, Warusawitharana M. Area under the curve as a measure of discounting. J Exp. Anal. Behav. 2001;76:235–243. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2001.76-235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. HIV/AIDS And Drug Abuse: Intertwined Epidemics. 2012 http://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/drugfacts/hivaids-drug-abuse-intertwin-edepidemics.

- Nielsen DA, Ho A, Bahl A, Varma P, Kellogg S, Borg L, Kreek MJ. Former heroin addicts with or without a history of cocaine dependence are more impulsive than controls. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;124:113–120. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odum AL, Baumann AA, Rimington DD. Discounting of delayed hypothetical money and food: effects of amount. Behav. Process. 2006;73:278–284. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odum AL, Madden GJ, Badger GJ, Bickel WK. Needle sharing in opioid-dependent outpatients: psychological processes underlying risk. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2000;60:259–266. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(00)00111-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton JH, Stanford MS, Barratt ES. Factor structure of the Barratt impulsiveness scale. J. Clin. Psychol. 1995;51:768–774. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(199511)51:6<768::aid-jclp2270510607>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panchanadeswaran S, Frye V, Nandi V, Galea S, Vlahov D, Ompad D. Intimate partner violence and consistent condom use among drug-using heterosexual women in New York City. Women Health. 2010;50:107–124. doi: 10.1080/03630241003705151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM. Delay discounting of money and alcohol in actively using alcoholics, currently abstinent alcoholics, and controls. Psychopharmacol. 2001;154:243–250. doi: 10.1007/s002130000638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen EB, Lawyer SR, Reilly W. Percent body fat is related to delay and probability discounting for food in humans. Behav. Process. 2010;83:23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2009.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds B, Ortengren A, Richards JB, de Wit H. Dimensions of impulsive behavior: personality and behavioral measures. Pers. Ind. Diff. 2006;40:305–315. [Google Scholar]

- Reimers S, Maylor EA, Stewart N, Chater N. Associations between a one-shot delay discounting measure and, age, income, education and real-world impulsive behavior. Pers. Ind. Diff. 2009;47:973–978. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez J, Comerford M, Chitwood DD, Fernandez MI, McCoy CB. High risk sexual behaviours among heroin sniffers who have no history of injection drug use: implications for HIV risk reduction. AIDS Care. 2002;14:391–398. doi: 10.1080/09540120220123793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santibanez SS, Garfein RS, Swartzendruber A, Purcell DW, Paxton LA, Greenberg AE. Update and overview of practical epidemiologic aspects of HIV/AIDS among injection drug users in the United States. J. Urban Health. 2006;83:86–100. doi: 10.1007/s11524-005-9009-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St. Lawrence JS, Jefferson KW, Alleyne E, Brasfield TL. Comparison of education versus behavioral skills training interventions in lowering sexual HIV-risk. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1995;63:154–157. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.63.1.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tempalski B, Lieb S, Cleland CM, Cooper H, Brady JE, Friedman SR. HIV prevalence rates among injection drug users in 96 large US metropolitan areas, 1992–2002. J. Urban Health. 2009;86:132–154. doi: 10.1007/s11524-008-9328-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tross S, Campbell AN, Cohen LR, Calsyn D, Pavlicova M, Miele GM, Hu MC, Haynes L, Nugent N, Gan W, Hatch-Maillette M, Mandler R, et al. Effectiveness of HIV/STD sexual risk reduction groups for women in substance abuse treatment programs: results of a NIDA clinical trials network trial. J. Acquir. Immune. Defic. Syndr. 2008;48:581–589. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31817efb6e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyndall MW, Currie S, Spittal P, Li K, Wood E, O'Shaughnessy MV, Schechter MT. Intensive injection cocaine use as the primary risk factor in the Vancouver HIV-1 epidemic. AIDS. 2003;17:887–893. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200304110-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyndall MW, Patrick D, Spittal P, Li K, O'Shaughnessy MV, Schechter MT. Risky sexual behaviours among injection drugs users with high HIV prevalence: implications for STD control. Sex. Trans. Infect. 2002;78(Suppl. 1):i170–i175. doi: 10.1136/sti.78.suppl_1.i170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsberg WM, Lam WK, Zule WA, Bobashev G. Efficacy of a woman-focused intervention to reduce HIV risk and increase self-sufficiency among African American crack abusers. Am. J. Public Health. 2004;94:1165–1173. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.7.1165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weller S, Davis K. Condom effectiveness in reducing heterosexual HIV transmission. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2002;1:1–10. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]