Abstract

BACKGROUND/OBJECTIVES

Recent research regarding vitamin B6 status including biochemical index is limited. Thus, this study estimated intakes and major food sources of vitamin B6; determined plasma pyridoxal 5'-phosphate (PLP); and assessed vitamin B6 status of Korean adults.

MATERIALS/METHODS

Three consecutive 24-h diet recalls and fasting blood samples were collected from healthy 20- to 64-year-old adults (n = 254) living in the Seoul metropolitan area, cities of Kwangju and Gumi, Korea. Vitamin B6 intake and plasma PLP were analyzed by gender and by vitamin B6 supplementation. Pearson's correlation coefficient was used to determine associations of vitamin B6 intake and plasma PLP.

RESULTS

The mean dietary and total (dietary plus supplemental) vitamin B6 intake was 1.94 ± 0.64 and 2.41 ± 1.45 mg/day, respectively. Median (50th percentile) dietary intake of men and women was 2.062 and 1.706 mg/day. Foods from plant sources provided 70.61% of dietary vitamin B6 intake. Only 6.3% of subjects consumed total vitamin B6 less than Estimated Average Requirements. Plasma PLP concentration of all subjects was 40.03 ± 23.71 nmol/L. The concentration of users of vitamin B6 supplements was significantly higher than that of nonusers (P < 0.001). Approximately 16% of Korean adults had PLP levels < 20 nmol/L, indicating a biochemical deficiency of vitamin B6, while 19.7% had marginal vitamin B6 status. Plasma PLP concentration showed positive correlation with total vitamin B6 intake (r = 0.40984, P < 0.0001).

CONCLUSIONS

In this study, vitamin B6 intake of Korean adults was generally adequate. However, one-third of subjects had vitamin B6 deficiency or marginal status. Therefore, in some adults in Korea, consumption of vitamin B6-rich food sources should be encouraged.

Keywords: Vitamin B6 intake, vitamin B6 status, pyridoxal 5'-phosphate (PLP), Korean adults

INTRODUCTION

Vitamin B6 is water-soluble and consists of pyridoxine (PN), pyridoxamine (PM), pyridoxal (PL), and their respective phosphate esters. Pyridoxal 5'-phosphate (PLP) is the most biologically active form of vitamin B6. Vitamin B6, which activates a number of coenzymes, is involved in numerous metabolic reactions. PLP is a cofactor for transaminases, decarboxylase, racemases, and other enzymes used in the metabolic transformations of amino acids and nitrogen-containing compounds [1].

Vitamin B6 deficiency includes weakness, sleeplessness, depression, cheilosis, glossitis, stomatitis, and impaired cell-mediated immunity [1]. Plasma PLP is most commonly used for measurement of vitamin B6 status because it reflects liver PLP concentrations and stores [2,3]. It has been suggested that vitamin B6 deficiency corresponds to plasma PLP levels < 20 nmol/L [4], while marginal, suboptimal vitamin B6 status may be observed for plasma PLP concentrations at 20- < 30 nmol/L [5,6]. Low PLP concentration has been linked to increased risk of seizures, chronic pain, depression, cognitive failure, immune deficiency, cancer, cardiovascular disease (CVD), and diabetes. [7,8,9,10,11]. Thus, an adequate vitamin B6 status may be important to reducing risk of these diseases in populations. Primary vitamin B6 deficiency is considered rare in developed countries; however, low vitamin B6 (PLP) concentrations have been reported in elderly populations, smokers, and alcoholics [12].

Vitamin B6 is widely distributed in foods from plant and animal origin. It is found in meats and eggs and in plant foods such as beans, cereals, and brown rice [4]. PL and PM are most common in animal products and PN predominates in plant foods. Plant sources are generally less bioavailable than animal sources because plants contain dietary fiber causing incomplete digestion and less bioavailable glycosylated forms of PN [13]. Korean adults consumed two-thirds of vitamin B6 from plant foods [14], which may result in insufficient vitamin B6 status in Koreans, although they have adequate vitamin B6 intakes. In addition, individuals with marginal intake of vitamin B6 would be more prone to decreased vitamin B6 status due to this incomplete bioavailability [15]. According to the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES 2007-2008), the mean vitamin B6 intakes of male and female adults were higher than the Recommended Nutrient Intakes (RNI) for Koreans [4]. Although vitamin B6 intakes of Koreans have been reported in several studies [16,17], recent research regarding vitamin B6 status including plasma PLP for Koreans is limited.

Therefore, the objectives of this study were to investigate intakes and major food sources of vitamin B6; examine associations between vitamin B6 intake and plasma PLP; and assess vitamin B6 status with plasma PLP concentration of 20- to 64-year-old adults in Korea.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

Korean adults (n = 275), aged 20 to 64 years, were recruited by advertisement in a convenience sampling in the Seoul metropolitan area (n = 148) and the cities of Kwangju (n = 76) and Gumi (n = 51) from 2009 to 2011. The subjects were interviewed in order to obtain information regarding age, former and current illness, medications taken, intake of vitamin and mineral supplements, and appetite. Twenty one adults who had known illnesses, took medications, or were not in good health were excluded. Thus, 254 Korean adults were included in this study. During an interview, subjects were asked whether they had used any vitamins, minerals, or other dietary supplements within 30 days of the interview. Subjects taking supplements were asked to provide information on the names, daily amount, and duration of supplementation. All interviews were conducted by trained interviewers. Interviewers measured weights and heights of the subjects in light clothing without shoes. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as kg/m2. Approval of the study protocol was obtained from the Institutional Review Board at Duksung Women's University (2011-04-0001), and each participant provided written informed consent.

Calculation of intake of selected nutrients and vitamin B6

A trained Korean interviewer recorded three consecutive 24-hour diet recalls (two weekdays and one weekend day). A computer-aided nutritional analysis program (CAN-pro) developed by the Korean Nutrition Society [18] was used in calculating intakes of macronutrients, water-soluble vitamins, and vitamin B6. Forty two subjects (16.5%, 17 men and 25 women) took supplements containing vitamin B6 (30 subjects in the Seoul metropolitan area and 12 subjects in Kwangju and Gumi). In subjects in their 20s, 19.5% took vitamin B6 supplements, and 19.6%, 14.0%, 10.9%, and 10.0% of those in their 30s, 40s, 50s, and 60s, respectively, took vitamin B6 supplements. Thus, the amounts of vitamin B6 consumed by the subjects were reported as dietary vitamin B6 (from foods only) and total vitamin B6 intake (dietary + supplemental vitamin B6). The dietary and total intakes of vitamin B6 were compared with the Estimated Average Requirements (EARs) for Koreans [4]. The top 30 major food sources of vitamin B6 consumed by the subjects were determined using the method of Cho and Kim [14].

Blood samples and plasma measurements

Venous blood samples (8-10 mL) were collected from the subjects, who had fasted overnight, in EDTA-containing vacutainer tubes between 7 and 10 am. The tubes were kept in crushed ice and protected from light. Blood samples were centrifuged at 3,000 rpm at 5℃ for 10 minutes. Plasma was frozen at -70℃ until analyzed.

Plasma PLP concentrations were determined by HPLC with fluorometric detection [19]. Recovery of added PLP from plasma was 94.2%. Within-day and between-day reproducibility was < 4% and < 5%, respectively. Detection limit of the assay was 1.94 nmol/L. All plasma samples were extracted in duplicate. A cutoff < 20 nmol/L for plasma PLP was used to indicate vitamin B6 deficiency [4] and 20- < 30 nmol/L was also used to indicate a marginal status [5,6].

Statistical analyi

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.1.3 software (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, North Carolina, US). Values are reported as mean ± standard deviation, and the differences in all variables between men and women were analyzed using Student's-test. Percentile values of vitamin B6 intakes were also reported by gender. Vitamin B6 intakes and plasma PLP concentrations were also reported by vitamin B6 supplementation (nonusers vs. users of dietary vitamin B6 supplements). Pearson's correlation coefficients were computed to determine relationships among vitamin B6 intake and plasma PLP concentration. Results were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Subject characteristics

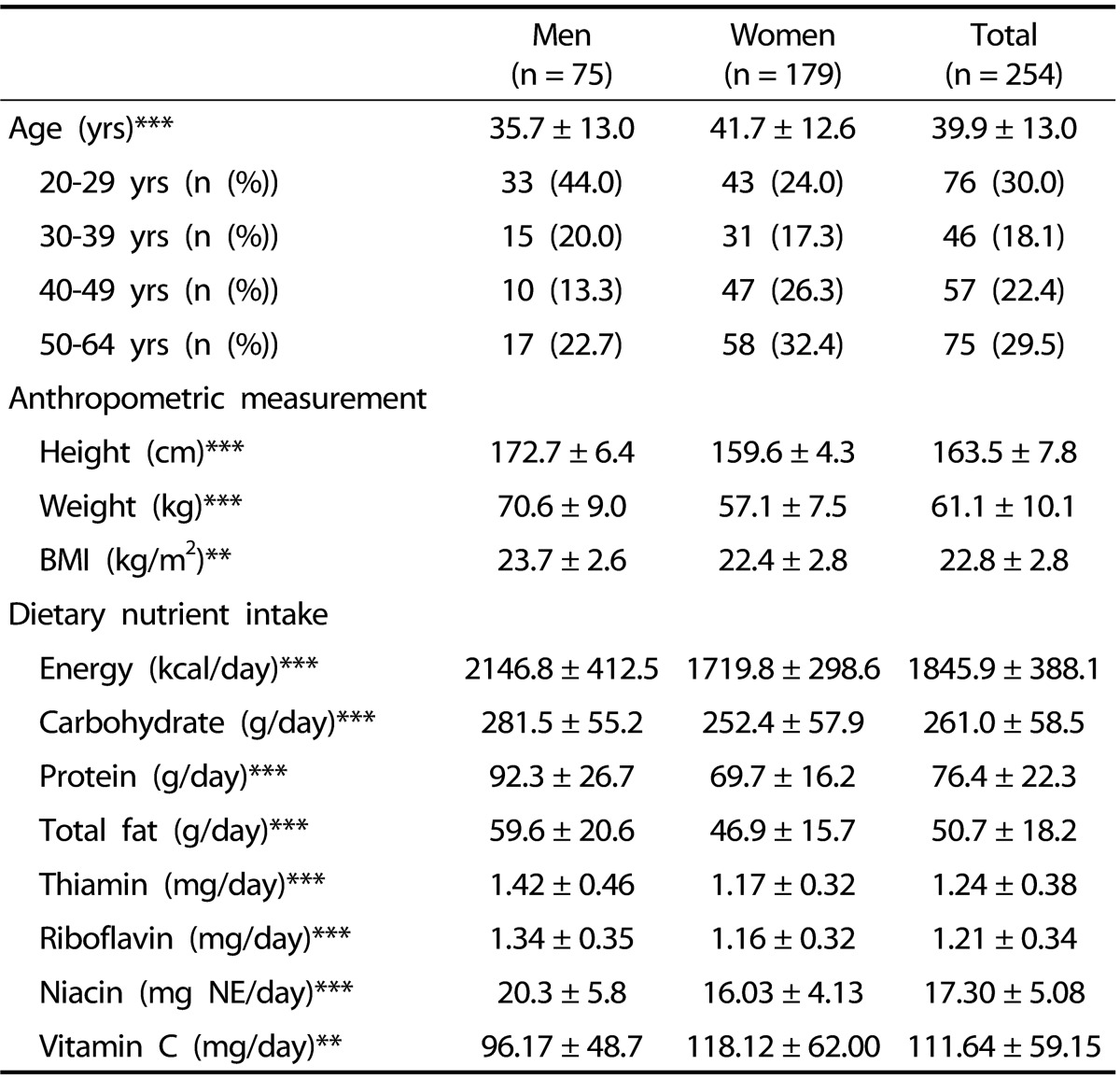

The characteristics of 254 Korean adults aged 20-64 years are shown in Table 1. The mean age of subjects was 39.9 ± 13.0 years and BMI was 22.8 ± 2.8 kg/m2. Significantly higher mean intakes of energy, macronutrients, and water-soluble vitamins were observed for male subjects compared with female subjects (P < 0.01).

Table 1.

General characteristics of 254 Korean adults by gender

Values are means ± standard deviations.

* P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001 by t-test

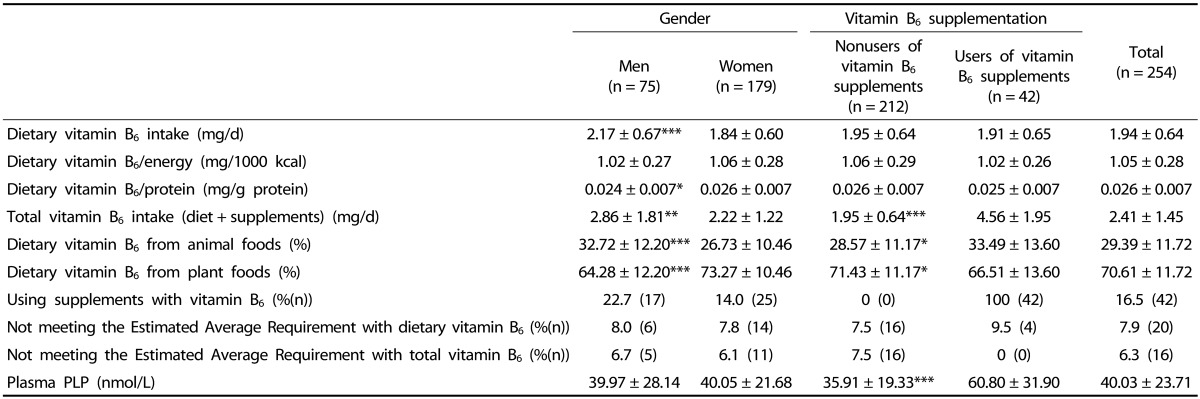

Vitamin B6 intake and major food sources

The mean dietary and total vitamin B6 intake was 1.94 ± 0.64 and 2.41 ± 1.45 mg/day, respectively (Table 2). Significantly higher dietary vitamin B6 intake was observed for males than for females, while a significantly lower ratio of dietary vitamin B6 to protein intake was observed for males than for females. Foods from plant sources provided 70.61% of dietary vitamin B6 intake. Women consumed more dietary vitamin B6 from plant foods than men and nonusers of vitamin B6 supplements had more vitamin B6 from plant foods than users (P < 0.05). Only 6.3% of the subjects consumed total vitamin B6 less than EARs.

Table 2.

Vitamin B6 intakes and plasma pyridoxal 5'-phosphate (PLP) concentration of 254 Korean adults by gender and by vitamin B6 supplementation

Values are means ± standard deviations. The Estimated Average Requirement for vitamin B6 is 1.3 mg/day for men aged 20-64 y and 1.2 mg/day for women aged 20-64 yrs.

* P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001 by t-test

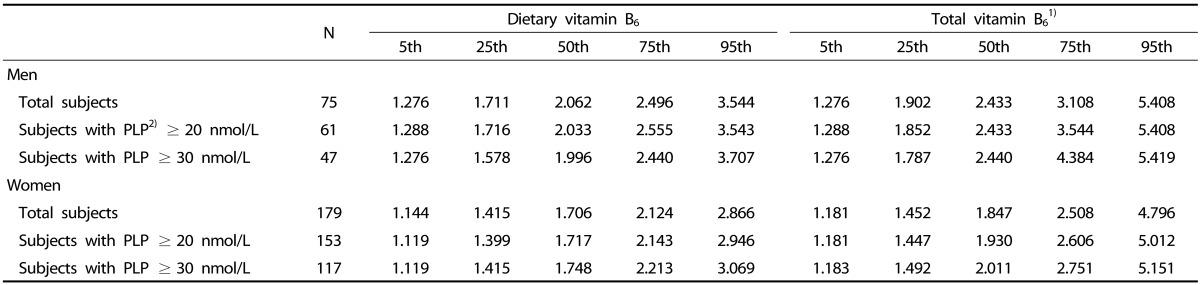

The mean dietary and total vitamin B6 intakes of Koreans with plasma PLP ≥ 20 nmol/L were 1.95 ± 0.56 and 2.36 ± 1.29 mg/day, respectively. The mean dietary and total vitamin B6 intake of subjects having PLP ≥ 30 nmol/L was 1.96 ± 0.69 and 2.50 ± 1.40 mg/day, respectively (data not shown). Percentile values of dietary and total vitamin B6 intake by gender are shown in Table 3. Median dietary and total vitamin B6 intake of male subjects was 2.062 and 2.433 mg/day, respectively. Female subjects had median dietary and total vitamin B6 intake of 1.706 and 1.847 mg/day, respectively.

Table 3.

Percentile values of dietary and total vitamin B6 intake of Korean adults aged 20-64 years

1) Dietary + supplemental vitamin B6

2) Plasma pyridoxal 5'-phosphate

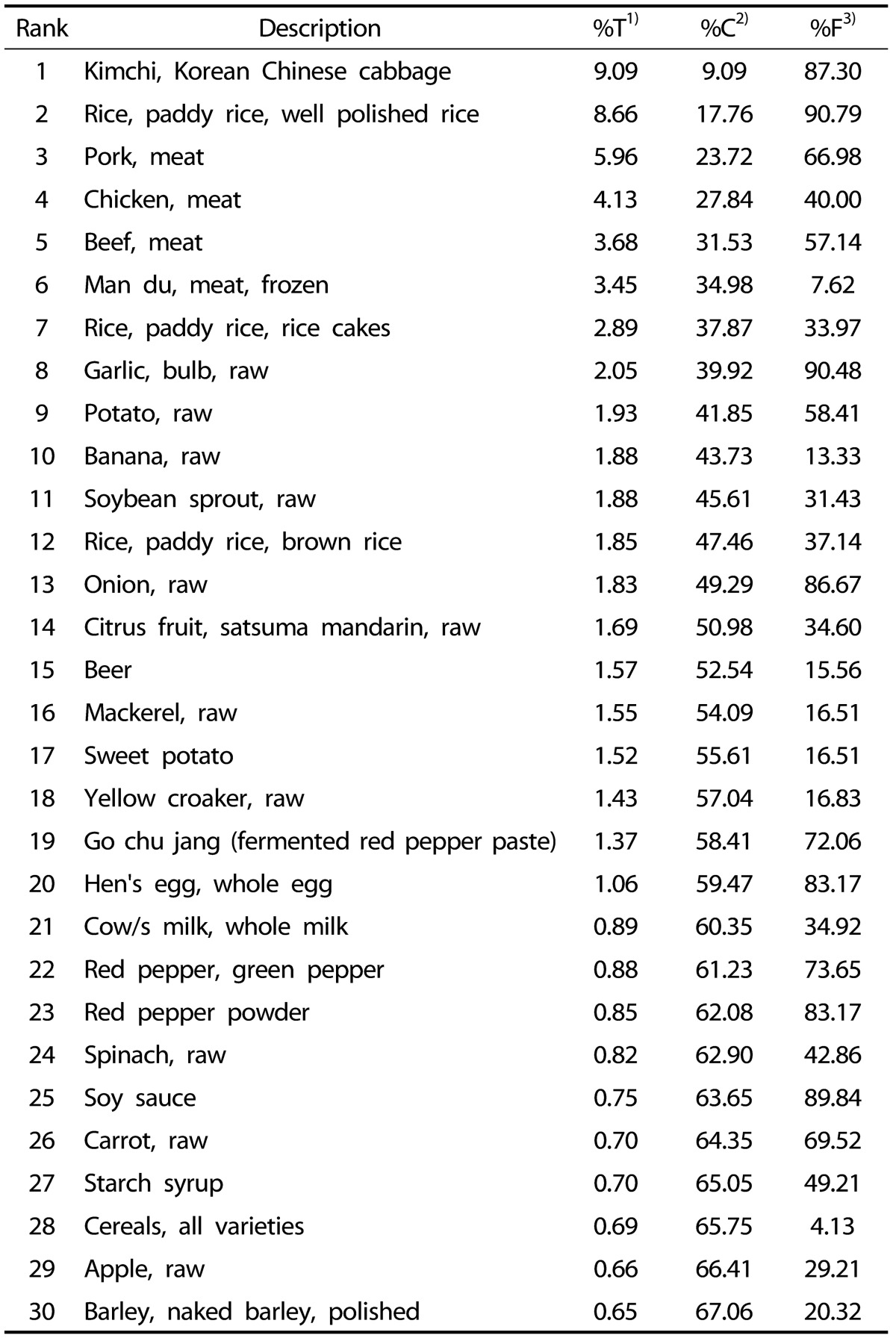

A list of major food sources of vitamin B6 consumed by Korean adults in this study is shown in Table 4. The top 10 major dietary sources were Korean Chinese cabbage kimchi, rice, pork, chicken, beef, Man Du (dumpling), rice cake, garlic, potato, and banana. The top 10 foods provided 43.73% of vitamin B6 intake, and the top 30 foods provided 67.06% of the intake.

Table 4.

Major food sources of vitamin B6 of 254 Korean adults

1) Percent of total intake

2) Cumulative percent of intake

3) Percent frequency

Plasma PLP concentration and vitamin B6 status

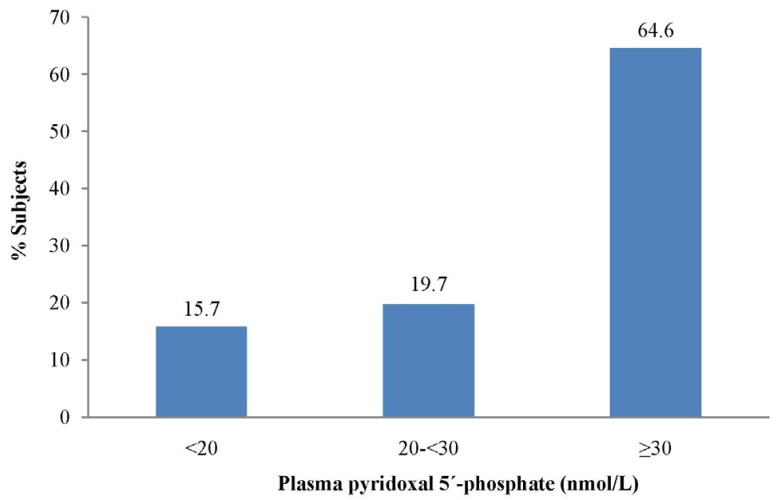

Plasma PLP concentration of all subjects was 40.03 ± 23.71 nmol/L (Table 2). No significant differences in PLP levels were observed by gender (P ≥ 0.05), however, a significantly higher concentration was observed for users of vitamin B6 supplements compared with nonusers (P < 0.001). The percent distribution of the subjects by plasma PLP concentration is shown in Fig. 1. Approximately 16% of Korean adults had PLP levels < 20 nmol/L, indicating a biochemical deficiency of vitamin B6 in adults [4]; 19% of subjects had marginal vitamin B6 status.

Fig. 1.

Percent distribution of 254 Korean adults by plasma pyridoxal 5'-phosphate concentration

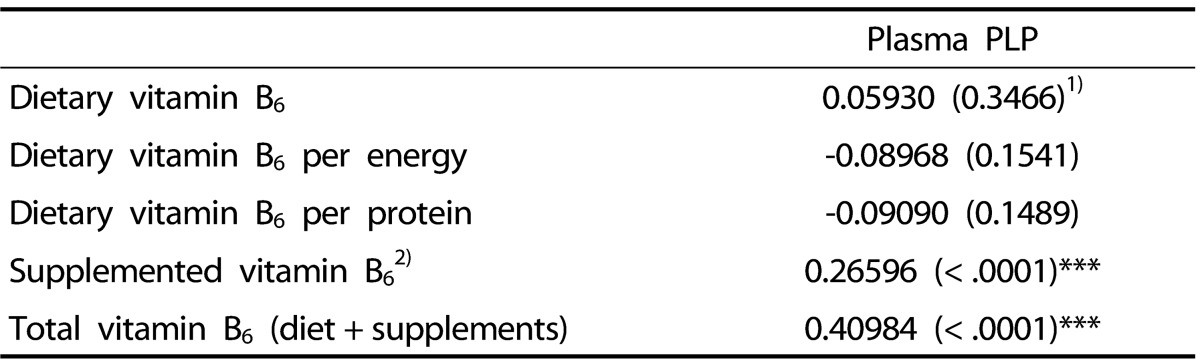

Associations among vitamin B6 intake and plasma PLP concentration

No significant correlations were observed between plasma PLP concentration and dietary vitamin B6 intake including the ratios of dietary vitamin B6 to energy and protein intake (P ≥ 0.05) (Table 5). However, plasma PLP concentration showed strong positive correlation with total vitamin B6 intake (r = 0.40984, P < 0.0001).

Table 5.

Correlations between vitamin B6 intakes and plasma pyridoxal 5'-phosphate (PLP) concentration

* Significant at P < 0.05, ** significant at P < 0.01, *** significant at P < 0.001

1) P-value

2) Vitamin B6 intake only from supplements of (n = 42)

DISCUSSION

The Korean Dietary Reference Intakes (KDRIs), revised in 2010, and the recommendations for vitamin B6 were the same as previous KDRIs. The KDRIs for vitamin B6 are set as EAR, RNI, and UL in all age groups older than one year old. EAR of the KDRIs for vitamin B6 is set at 1.3 mg/day for men and 1.2 mg/day for women aged 19-64 years, based on reports that the intake of vitamin B6 of Korean adults is 1.5 mg/day with the plasma PLP concentration over 30 nmol/L. The median intakes of 2007-2008 KNHANES, 1.5-1.7 mg/d, were also considered [4]. EARs are the daily nutrient intake estimated to meet the requirement of half of healthy individuals in a life-stage group, and thus are set at the median of the distribution of requirements. RNIs for nutrients are expected to meet the needs of 97-98% of healthy individuals. RNIs have been set using the same concept as the Recommended Dietary Allowances (RDAs) of 2005 [4].

In this study, the mean dietary vitamin B6 intakes of men (2.17 mg/day) and women (1.84 mg/day) were much higher than RNIs and intakes of Korean adults (1.7-1.8 for men, 1.3-1.4 mg/day for women) reported in KNHANES 2007-2008 [4]. Also, in this study, current dietary vitamin B6 intake (1.94 ± 0.64 mg/day) was increased compared to the intakes of Korean young adults reported in 2001 (0.987 mg/day) [14] and 2005 (1.44-1.57 mg/day) [20], but is similar to recently reported dietary vitamin B6 intake of Japanese (1.7 mg/day) [21] and Chinese adults (1.7 mg/day) [22]. In this study, dietary supplements providing vitamin B6 increased mean intake from food sources alone by 32% for men, from 2.17 to 2.86 mg, and by 21% for women, from 1.84 to 2.22 mg. Approximately 17% of Korean adults took vitamin B6 supplements and their mean total vitamin B6 intake was 4.56 mg/day, which is much lower than that of American adults taking vitamin B6 supplements (13.74-14.16 mg/day) [23].

Median (50th percentile) nutrient intakes of the healthy population are used for setting EARs. EARs for vitamin B6 are based on the vitamin B6 intake required for plasma PLP ≥ 30 nmol/L [4]. In this study, median dietary vitamin B6 intakes of men and women were 2.062 and 1.706 mg/day, respectively, higher than those of KNHANES 2007-2008 (1.5-1.6 mg/day for men, 1.1-1.2 mg/day for women) [4]. Median dietary vitamin B6 intake of men and women with PLP ≥ 30 nmol/L was 1.996 and 1.748 mg/day, respectively. Thus, current EARs for vitamin B6 of KDRIs might be underestimated.

EARs are used to estimate the prevalence of inadequate intake within a group of individuals [4]. In this study, in Korean adults aged 20-64 years, low proportions of participants had intakes below EARs for dietary vitamin B6 intake (8.0 % of men, 7.8% of women). Only 6.3% had total vitamin B6 (dietary + supplemental) less than EARs. In previous studies conducted before 2005, dietary vitamin B6 intakes were compared to RDAs for vitamin B6. In 2001, Cho and Kim [14] reported that 87.2% of Korean women (n = 218) consumed vitamin B6 less than RDAs. In 2005, 57% of Korean young adults (n = 294) had vitamin B6 intake less than RDAs [20]. In the current study, total vitamin B6 intakes of only 20% were less than the current RNIs. Therefore, vitamin B6 intakes of Koreans are improved and are currently adequate.

Regarding major dietary sources of vitamin B6, in the current study, the top 10 foods provide nearly 44% of dietary vitamin B6, whereas approximately 64% and 50-75% was reported for Korean adults in 2001 [14] and in 2005 [20], respectively; thus, dietary contributors of vitamin B6 of Korean adults have been more varied over the years. Among the 10 major sources in this study, rice, pork, chicken, garlic, potato, and banana were found in the top 10 sources reported in 2001 [20]. In this study, women consumed more dietary vitamin B6 from plant foods than men. In general, plant foods contain less protein than animal-derived foods. For this reason, the ratio of dietary vitamin B6 to protein intake of women might be higher than that of men who had much high protein intake.

Plasma PLP concentration, a direct measure of the active coenzyme, reflects dietary intake and tissue status of vitamin B6. Plasma PLP < 30 nmol/L has been used as an indicator of vitamin B6 deficient status and the Committee of KDRIs based the vitamin B6 intake required for this value [4]. The more conservative cutoff for plasma PLP of 20 nmol/L was selected as the basis for the average requirement (EAR) for vitamin B6 in US DRIs, although its use may overestimate the B6 requirement for health maintenance of more than half of the group, and Hansen et al. [24] reported an acceptable value of 30 nmol/L for plasma PLP concentration. Therefore, values in the 20 to 30 nmol/L range are recommended as indicative of suboptimal, marginal vitamin B6 status [25]. Vitamin B6 deficiency has also been shown to be common in the adult population, with prevalence rates of 11-24% [12,26]. According to the 2003-2006 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) in the U.S., 24% of people had vitamin B6 deficient status [12]. In this study, the prevalence rate of the deficiency was 15.7%, and 19.7% of the subjects had marginal vitamin B6 status. In users of vitamin B6 supplements, only two subjects (4.8 %) had plasma PLP concentration < 20 nmol/L and none of the users had marginal status, meaning that vitamin B6 supplementation may protect against vitamin B6 deficiency. Although not accompanied by clinical symptoms of deficiency, marginal vitamin B6 status may increase the risk for chronic diseases such as cancer and CVD [27,28,29]. In the current study, 35.4% of Korean adults had plasma PLP concentration < 30 nmol/L, slightly higher than those of Taiwanese (28.9%) [27] and Puerto Rican adults (28.5%) [26]. Therefore, in this study, one-third of Korean adults were vitamin B6 deficient or marginal status and should improve their vitamin B6 status for prevention of chronic diseases such as CVD, inflammatory diseases, and cancer.

In this study, although male subjects showed significantly higher dietary and total vitamin B6 intakes than female subjects, no significant difference in plasma PLP concentration by gender was observed. Vitamin B6 is required by many enzymes in protein metabolism and high protein intake may increase usage of vitamin B6 in the body. Thus, several studies have reported that high protein intake lowers plasma PLP concentrations [30,31]. In this study, men consumed less dietary vitamin B6 per protein intake than women, which might result in no difference of plasma PLP concentration by gender.

The bioavailability of nutrients in foods and dietary supplements is an important issue in evaluating the adequacy of diets and resolving inadequate status [25]. In an animal study, the bioavailability of vitamin B6 in humans consuming a mixed diet was approximately 75% [32] and the digestibility of vitamin B6 from animal products was approximately 10% greater than from plant sources [33]. Pyridoxine 5'-β-D-glucoside, a glycosylated from of vitamin B6 commonly found in foods of plant origin, is approximately 50% as bioavailable as other forms of vitamin B6 [8]. Therefore, the bioavailability of vitamin B6 from animalderived foods is higher than that from plant foods. In the U.S., approximately 50% of dietary vitamin B6 is from animal sources and the other 50% is from plant-based foods [34]. According to the National Diet and Nutrition Survey, British adults consume 35% of vitamin B6 from animal foods [35]. In this study, only 29% of vitamin B6 intake was from animal sources, slightly lower, compared to results reported for Korean adults in 2001 (32%) [14] and 2005 (32-37%) [20]. Although the prevalence of inadequate vitamin B6 intake was quite low, one-third of the subjects in this study had vitamin B6 deficiency or marginal status. The reason might be that vitamin B6 intakes were mainly from plant foods, which are less bioavailable.

A positive relationship has been observed between vitamin B6 intake and plasma PLP [19,24]. In addition, significant correlations between plasma PLP and urinary total vitamin B6 and plasma total vitamin B6 have been reported [36]. In this study, no significant correlations were observed between plasma PLP and dietary vitamin B6 intake, including the ratios of dietary vitamin B6 to energy and protein intake. However, plasma PLP concentration showed strong positive correlation with total vitamin B6 intake (r = 0.40984, P < 0.0001). Because the subjects supplementing vitamin B6 additionally consumed 0.44-7.62 mg/day of vitamin B6, total vitamin B6 intake showed significant correlation with plasma PLP rather than dietary intake. In addition, the form of vitamin B6 in most supplements consumed by subjects was PN hydrochloride, which is more bioavailable than a glycosylated from of vitamin B6 in plant foods. Thus, in this study, supplemented vitamin B6 might produce a greater response on plasma PLP than dietary vitamin B6 mostly from plant foods.

The nutrient database of CAN-pro is based on the Korean Food Composition Table (Korean Rural Development Administration, 2006) and the Food Values (Korean Nutrition Society, 2009). The nutrient database including vitamin B6 of these is based on raw foods. In raw foods, nutrient contents are changed by food preparation, cooking conditions (e.g. time and temperature), and the addition of different ingredients depending on household preferences. Therefore, cooked foods consumed by the subjects might be underestimated.

In conclusion, in this study, vitamin B6 intake of Korean adults was generally adequate. However, 15% of the subjects had vitamin B6 deficiency and 20% had marginal status. Low vitamin B6 status is associated with high risk of CVD, inflammatory disease, and cancer. Therefore, in some adults in Korea, consumption of vitamin B6-rich animal food sources, which are more bioavailable, should be encouraged. Vitamin B6 supplementation could be considered for improvement of vitamin B6 status, if necessary.

Footnotes

This research was supported by the 2013 research fund from the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2011-0021273).

References

- 1.Combs GF., Jr . The Vitamins: Fundamental Aspects in Nutrition and Health. 3rd ed. Burlington (MA): Elsevier Academic Press; 2008. Chapter 13. Vitamin B6; pp. 313–329. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lumeng L, Lui A, Li TK. Plasma content of B6 vitamers and its relationship to hepatic vitamin B6 metabolism. J Clin Invest. 1980;66:688–695. doi: 10.1172/JCI109906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bode W, Mocking JA, van den Berg H. Influence of age and sex on vitamin B6 vitamer distribution and on vitamin B6 metabolizing enzymes in Wistar rats. J Nutr. 1991;121:318–329. doi: 10.1093/jn/121.3.318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.The Korean Nutrition Society. Dietary Reference Intakes for Koreans. Seoul: The Korean Nutrition Society; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leklem JE. Vitamin B6: a status report. J Nutr. 1990;120(Suppl 11):1503–1507. doi: 10.1093/jn/120.suppl_11.1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Driskell JA. Vitamin B6 requirements of humans. Nutr Res. 1994;14:293–324. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Merete C, Falcon LM, Tucker KL. Vitamin B6 is associated with depressive symptomatology in Massachusetts elders. J Am Coll Nutr. 2008;27:421–427. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2008.10719720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spinneker A, Sola R, Lemmen V, Castillo MJ, Pietrzik K, González-Gross M. Vitamin B6 status, deficiency and its consequences--an overview. Nutr Hosp. 2007;22:7–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peeters AC, van Landeghem BA, Graafsma SJ, Kranendonk SE, Hermus AR, Blom HJ, den Heijer M. Low vitamin B6, and not plasma homocysteine concentration, as risk factor for abdominal aortic aneurysm: a retrospective case-control study. J Vasc Surg. 2007;45:701–705. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2006.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang XH, Ma J, Smith-Warner SA, Lee JE, Giovannucci E. Vitamin B6 and colorectal cancer: current evidence and future directions. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:1005–1010. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i7.1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rogers KS, Mohan C. Vitamin B6 metabolism and diabetes. Biochem Med Metab Biol. 1994;52:10–17. doi: 10.1006/bmmb.1994.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morris MS, Picciano MF, Jacques PF, Selhub J. Plasma pyridoxal 5'-phosphate in the US population: the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2003-2004. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87:1446–1454. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/87.5.1446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gregory JF, 3rd, et al. Bioavailability of vitamin B6. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1997;51(Suppl 1):S43–S48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cho YO, Kim YN. Dietary intake and major dietary sources of vitamin B6 in Korean young women. Nutr Sci. 2001;4:20–25. [Google Scholar]

- 15.da Silva VR, Russell KA, Gregory JF., 3rd . Vitamin B6. In: Erdman JW Jr, MacDonald IA, Zeisel SH, editors. Present Knowledge in Nutrition. 10th ed. Ames (IA): John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., Publication; 2012. pp. 307–320. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chung KH, Shin KO, Yoon JA, Choi KS. Study on the obesity and nutrition status of housewives in Seoul and Kyunggi area. Nutr Res Pract. 2011;5:140–149. doi: 10.4162/nrp.2011.5.2.140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jeon KJ, Lee O, Kim HK, Han SN. Comparison of the dietary intake and clinical characteristics of obese and normal weight adults. Nutr Res Pract. 2011;5:329–336. doi: 10.4162/nrp.2011.5.4.329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.The Korean Nutrition Society. Computer Aided Nutritional Analysis Program for Professionals. Seoul: The Korean Nutrition Society; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cho YO, Kim YN. Evaluation of vitamin B6 status and Korean RDA in Korean college students following a uncontrolled diet. Nutr Sci. 2002;5:20–25. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cho YO, Kim BY. Vitamin B6 intake by Koreans should be based on sufficient amount and a variety of food sources. Nutrition. 2005;21:1113–1119. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2005.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takata Y, Cai Q, Beeghly-Fadiel A, Li H, Shrubsole MJ, Ji BT, Yang G, Chow WH, Gao YT, Zheng W, Shu XO. Dietary B vitamin and methionine intakes and lung cancer risk among female never smokers in China. Cancer Causes Control. 2012;23:1965–1975. doi: 10.1007/s10552-012-0074-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ma E, Iwasaki M, Kobayashi M, Kasuga Y, Yokoyama S, Onuma H, Nishimura H, Kusama R, Tsugane S. Dietary intake of folate, vitamin B2, vitamin B6, vitamin B12, genetic polymorphism of related enzymes, and risk of breast cancer: a case-control study in Japan. Nutr Cancer. 2009;61:447–456. doi: 10.1080/01635580802610123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service. Total nutrient intakes: percent reporting and mean amounts of selected vitamins and minerals from food and dietary supplements, by gender and age, what we eat in American, NHANES 2009-2010 [Internet] Washington, D.C.: Agricultural Research Service; 2012. [cited 2014 May 10]. Available from: http://www.ars.usda.gov/ba/bhnrc/fsrg. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hansen CM, Shultz TD, Kwak HK, Memon HS, Leklem JE. Assessment of vitamin B6 status in young women consuming a controlled diet containing four levels of vitamin B6 provides an estimated average requirement and recommended dietary allowance. J Nutr. 2001;131:1777–1786. doi: 10.1093/jn/131.6.1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.da Silva VR, Mackey AD, Davis SR, Gregory JF., 3rd . Vitamin B6. In: Ross AC, Caballero B, Cousins RJ, Tucker KL, Ziegler TR, editors. Modern Nutrition in Health and Disease. 11th ed. Philadephia (PA): Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2014. pp. 341–350. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ye X, Maras JE, Bakun PJ, Tucker KL. Dietary intake of vitamin B6, plasma pyridoxal 5'-phosphate, and homocysteine in Puerto Rican adults. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010;110:1660–1668. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2010.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin PT, Cheng CH, Liaw YP, Lee BJ, Lee TW, Huang YC. Low pyridoxal 5\'-phosphate is associated with increased risk of coronary artery disease. Nutrition. 2006;22:1146–1151. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2006.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sakakeeny L, Roubenoff R, Obin M, Fontes JD, Benjamin EJ, Bujanover Y, Jacques PF, Selhub J. Plasma pyridoxal-5-phosphate is inversely associated with systemic markers of inflammation in a population of U.S. adults. J Nutr. 2012;142:1280–1285. doi: 10.3945/jn.111.153056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shen J, Lai CQ, Mattei J, Ordovas JM, Tucker KL. Association of vitamin B6 status with inflammation, oxidative stress, and chronic inflammatory conditions: the Boston Puerto Rican Health Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91:337–342. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2009.28571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pannemans DL, van den Berg H, Westerterp KR. The influence of protein intake on vitamin B6 metabolism differs in young and elderly humans. J Nutr. 1994;124:1207–1214. doi: 10.1093/jn/124.8.1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hansen CM, Leklem JE, Miller LT. Vitamin B6 status of women with a constant intake of vitamin B6 changes with three levels of dietary protein. J Nutr. 1996;126:1891–1901. doi: 10.1093/jn/126.7.1891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tarr JB, Tamura T, Stokstad EL. Availability of vitamin B6 and pantothenate in an average American diet in man. Am J Clin Nutr. 1981;34:1328–1337. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/34.7.1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roth-Maier DA, Kettler SI, Kirchgessner M. Availability of vitamin B6 from different food sources. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2002;53:171–179. doi: 10.1080/09637480220132184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kant AK, Block G. Dietary vitamin B6 intake and food sources in the US population: NHANES II, 1976-1980. Am J Clin Nutr. 1990;52:707–716. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/52.4.707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Henderson L, Irving K, Gregory J, Bates CJ, Prentice A, Perks J, Swan G, Farron M. Volume 3: Vitamin and Mineral Intake and Urinary Analytes. London: The Stationery Office; 2003. The National Diet and Nutrition Survey: Adults Aged 19 to 64 Years. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hansen CM, Leklem JE, Miller LT. Changes in vitamin B6 status indicators of women fed a constant protein diet with varying levels of vitamin B6. Am J Clin Nutr. 1997;66:1379–1387. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/66.6.1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]