Abstract

NG2 is purportedly one of the most growth-inhibitory chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans (CSPGs) produced after spinal cord injury. Nonetheless, once the severed axon tips dieback from the lesion core into the penumbra they closely associate with NG2+ cells. We asked if proteoglycans play a role in this tight cell—cell interaction and whether overadhesion upon these cells might participate in regeneration failure in rodents. Studies using varying ratios of CSPGs and adhesion molecules along with chondroitinase ABC, as well as purified adult cord-derived NG2 glia, demonstrate that CSPGs are involved in entrapping neurons. Once dystrophic axons become stabilized upon NG2+ cells, they form synaptic-like connections both in vitro and in vivo. In NG2 knock-out mice, sensory axons in the dorsal columns dieback further than their control counterparts. When axons are double conditioned to enhance their growth potential, some traverse the lesion core and express reduced amounts of synaptic proteins. Our studies suggest that proteoglycan-mediated entrapment upon NG2+ cells is an additional obstacle to CNS axon regeneration.

Keywords: chondroitinase, dystrophic axons, glial scar, NG2 proteoglycan, oligodendrocyte progenitor cells, spinal cord injury

Introduction

After spinal cord injury (SCI), various cellular and molecular changes occur that result in glial scar formation. While the scar itself is formed primarily by reactive astrocytes and plays a role in regeneration failure, the functions of the cell types that proliferate within and migrate toward the core of the lesion are poorly understood (Frisén et al., 1995; Zai and Wrathall, 2005; Lytle et al., 2006; Busch et al., 2010; Göritz et al., 2011; Soderblom et al., 2013). Our lab suggested that one population of neural-glial 2 proteoglycan (NG2)-producing cells in the lesion core may help stabilize dystrophic axons as activated macrophages force them to retract to the caudal end of the lesion (Busch et al., 2010). However, the mechanisms that govern this tight interaction and whether chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans (CSPGs) are involved remain important unanswered questions.

The role of NG2+ cells in the normal CNS and after injury remains controversial. NG2 is a member of the CSPG family of ECM molecules that contribute to formation of the scar. CSPGs, comprised of a protein core and varying numbers of covalently linked glycosaminoglycan (GAG) side chains, at high concentrations inhibit neurite outgrowth and cell attachment (Snow et al., 1990; McKeon et al., 1991; Dou and Levine, 1994; Fitch and Silver, 1997; Shen et al., 2009). Because NG2 is upregulated after CNS injury (Levine, 1994; Jones et al., 2002), it has been suggested that NG2+ cells inhibit regeneration (Dou and Levine, 1994; Tan et al., 2005). However, several studies suggest that NG2+ cells are growth promoting. Axons that have regrown through a graft after SCI (Jones et al., 2003) and the dystrophic tips of severed axons that remain within the lesion reside closely among NG2+ cells (Jones et al., 2002; McTigue et al., 2006; Busch et al., 2010). The extent of axon regeneration did not increase in NG2-null mice after spinal cord transection (de Castro et al., 2005) and NG2+ cells seem to facilitate growth of developing axons (Yang et al., 2006).

We sought to better understand the interaction between severed sensory axons and NG2+ cells after dorsal column injury. When combined with growth-promoting molecules in critical ratios in vitro, NG2 and other CSPGs initially confine axons to their territory via a GAG-mediated mechanism. NG2+ cells also constrain early outgrowth and can lead to longer-lasting entrapment of the neuron on the cell surface through synaptic-like connections mediated, in part, by integrins. Given that neurons form synapses with NG2+ cells under physiological conditions throughout the CNS (Bergles et al., 2000; Gallo et al., 2008), it is possible that synaptic-like interactions within the damaged white matter allow for long-lasting associations between the dystrophic tips of sensory neurons and NG2+ cells. While these stabilizations may initially prevent further dieback, they may also restrain the forward movements of the axon tip. This interaction between NG2+ cells and injured neurons after SCI provides a new way of thinking about how CSPGs “inhibit” cell migration and helps explain for the first time how dystrophic axon tips persist within the lesion environment.

Materials and Methods

Purification of NG2+ cells from the adult spinal cord.

We used a novel isolation protocol (Bai et al., 2013) to obtain highly purified NG2+ cells from adult (>8 weeks) C57BL/6J mice. After dissecting out the spinal cords, the surface blood vessels were removed and the tissue was dissociated with trypsin and EDTA for 30 min at room temperature. Digested tissue was spun at 800 × g for 5 min, washed three times, then placed on a Percoll gradient (GE Healthcare, catalog #17-0891-02). The gradient was centrifuged for 30 min at 2000 rpm. The cellular fractions were collected, washed, and resuspended in 1 ml of DMEM/F12 medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum. Cells were plated in a PLL-coated 75 cm2 flask and grown at 37°C in 5% CO2 for 4 weeks, then passaged to purify. After passage, 99% of cells were NG2+, <5% expressed GFAP, and there was no detectable expression of mature oligodendrocyte markers, such as CNP or MBP. Most cells (84%) expressed PDGFα receptor, a marker often associated with oligodendrocyte precursor cells. The majority of cells (99%) expressed oligodendrocyte lineage markers A2B5, Olig2, and O4 (in later passages).

Culturing DRG neurons.

DRG neurons were harvested as previously described (Tom et al., 2004b). Briefly, the DRGs were removed from adult female Sprague Dawley rats (Zivic-Miller Laboratories; Harlan). After the central and peripheral roots were trimmed, DRGs were incubated in a solution of collagenase II (200 U/ml; Worthington Biochemicals) and dispase II (2.5 U/ml; Roche) in HBSS. Digested DRGs were washed in HBSS-CMF and gently triturated three times, followed by low-speed centrifugation. The dissociated neurons were resuspended in Neurobasal A media supplemented with B-27, GlutaMAX, and penicillin–streptomycin (Invitrogen) for counting.

Longest neurite outgrowth assay.

The coverslips were coated with poly-l-lysine (PLL; 0.1 mg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich) overnight at room temperature, then washed with ddH20. Coverslips were bathed in laminin (5 μg/ml; Invitrogen) in HBSS-CMF and incubated (37°C) for 2 h before plating cells. For the NG2+ cell monolayer experiments, adult mouse spinal cord NG2+ glial cells were densely plated (60,000 cells/spot) for 24 h. Cells were treated with chondroitinase ABC (ch'ase; 0.1 U/ml in saline; Seikagaku) for 4 h before adding dissociated DRG neurons (1500–2000 neurons/coverslip) to the culture. DRGs, along with ch'ase in fresh medium, were added and permitted to grow for 24 h. For the laminin outgrowth coverslips, PLL-coated coverslips were bathed in 1 μg/ml or 5 μg/ml laminin in CMF and incubated at 37°C. After 2 h of incubation, dissociated DRG neurons were added to the culture. Outgrowth was permitted for 24 h, then the cultures were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and stained for NG2 (Millipore Bioscience Research Reagents) and β-III-tubulin (Sigma). For outgrowth studies, the longest neurite of each neuron growing on a complete monolayer of NG2+ cells was measured using MetaMorph software.

Entrapment assay.

The coverslips were coated with PLL and then with nitrocellulose. The coverslips were then bathed in laminin to form substrates of various concentrations [0 μg/ml, 1 μg/ml, or 5 μg/ml in Ca2+/Mg2+-free HBSS (HBSS-CMF); BTI] for 2+ h at 37°C. Adult mouse spinal cord NG2+ cells were plated on the coverslips at a density of 15,000 cells/coverslip. Coverslips were placed in the incubator (37°C). Twenty-four hours after the plating of NG2+ cells, dissociated DRG neurons were added to the culture (2000 cells/coverslip). After an additional 24 h, the cultures were fixed for 30 min with 4% paraformaldehyde, washed, and blocked in 5% natural goat serum. The fixed cells were stained for NG2, β-III-tubulin, and DAPI. Each neuron with a cell body beginning on an NG2+ cell with neurite outgrowth was imaged and quantified by counting the number of neurons capable of extending processes off the surface of the NG2+ cell. To examine the role of NG2 and other CSPGs in entrapment, chondroitinase was added in the media (0.1 U/ml) at the time of NG2+ cell plating, then again in the media at the time of adding DRG neurons. For 5 d studies, the media and ch'ase were replaced daily.

Stripe assays.

The stripe assay experiments were performed according to a protocol modified from Knöll et al., 2007. The coverslips were coated in PLL overnight at room temperature, then washed with ddH20. The coverslips were dried completely and each coverslip was placed in the center of a large Petri dish. The stripe matrix (Karlsruhe Institute of Technology, Germany) was placed on the center of the coverslip, ensuring that the entire lanes were on the coverslip. Solution A consisted of a laminin (1 μg/ml, 5 μg/ml, or 10 μg/ml; Invitrogen)-aggrecan (50 μg/ml or 100 μg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich) mixture or a laminin (2 μg/ml)-NG2 (7 μg/ml; gift from Joel Levine, Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, NY) mixture (made with BSA conjugated with 488 in CMF). One-hundred fifty microliters of solution A was placed on the inlet channel and gently aspirated through the lanes using a flamed glass pipette, with care taken not to aspirate through the entire solution so the lanes remain covered in substrate. The coverslips were then placed in the incubator for 30 min. The solution was removed from the matrix and replaced with 2% BSA. After an additional 10 min incubation at 37°C, the BSA was removed from the coverslips, along with the matrix. Coverslips were placed in a 24-well plate, where they were bathed in 400 μl of solution B [low laminin (1 μg/ml) or fibronectin (5 μg/ml), with BSA in CMF] and incubated at 37°C for 30 min. Solution B was then removed from the wells and replaced with 2% BSA for another 10 min incubation at 37°C. To remove the GAG chains of the proteoglycans, chondroitinase (0.1 U/ml in saline) was added to the coverslips 4+ h before the plating of DRG neurons. Dissociated DRG neurons were then added to the coverslips at a density of 2000 cells/coverslip. Outgrowth was permitted for 48 h and then the cultures were fixed with 4% PFA. Some coverslips were immunostained for laminin (Sigma), CS56 (Sigma), and fibronectin (BD Biosciences) to ensure these components were present. All coverslips were stained with β-III-tubulin to visualize the neurons. All neurons with outgrowth twice the length of their cell bodies were imaged. Neurons with cell bodies beginning in the green lane were analyzed to see whether or not they extended processes into the black lane and vice versa.

Immunocytochemistry.

All cultures were blocked in 5% natural goat serum. All antibodies were incubated overnight at 4°C. The primary antibodies used included the following: anti-NG2 (Millipore), anti-GFAP (Accurate), anti-vimentin (Sigma), anti-SV2 (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank), anti-PSD-95 (Abcam), anti-SNAP-25 (Sigma), anti-fibronectin (BD Biosciences), anti-laminin (Sigma), DAPI (Sigma), anti-Olig2 (Millipore), anti-A2B5, and anti-O4 (generous gifts from the laboratory of Robert Miller, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH). This was followed by the appropriate secondary antibodies, Alexa Fluor 350, 488, 594, 633, or 647.

Quantification of synaptoid number in vitro between DRG axons and NG2 cells.

Pixel intensity was measured using ImageJ software for colocalization studies. Methods similar to those described by Ippolito and Eroglu, 2010 were used to quantify synapses. All images were taken with the same settings on the Zeiss LSM510 confocal microscope. An area of interest was outlined around the cell body, two times the cell body diameter in size. Using the puncta analyzer and setting the threshold for 50, the number of puncta were calculated.

Synaptic vesicle cycling assay.

Dishes were coated in poly-l-lysine overnight at room temperature, rinsed, and coated in 1 μg/ml laminin in CMF for 2 h at 37°C. Laminin was removed and NG2+ cells were plated densely to form a monolayer (40,000 cells in 40 μl DMEM-F12 media for 30 min at room temperature), then 3 ml of DMEM-F12 was added to the dishes and the dishes were incubated overnight. DRG neurons were added 24 h later. The dishes were incubated for 5 d, and the media was changed at day 3 to maintain the cultures. On day 5 of coculture, the media was removed and a high K+ solution (5.37 mm KCl, 125 mm NaCl, 24 mm NaHCO3) containing FM dye (FM1–43; Invitrogen) was added to the culture for 3 min. A low Ca2+ (0.5 mm) solution was added to the dish, followed immediately by the addition of ADVACEP-7 (Sigma) for 5 min to quench background fluorescence. The solutions were removed and an additional wash with low Ca2+ was performed for 10 min. The fluorescence was imaged on a Leica DMI6000 (AF) microscope. Then the solution was removed and high K+ was added without dye for 3 min. The fluorescence was imaged again. ImageJ software was used to outline the entire neuron and compare the pixel intensity within the neuron before and after stimulation with or without dye.

Cell lysate for Western blot.

NG2+ cells were grown to confluency on cell culture dishes pretreated with 1× PLL for 48 h. For cells that were pretreated with ch'ase, the enzyme was added (0.1 U) to the media 1 h before adding the RIPA buffer. Cells were washed with ice-cold PBS and incubated on ice with RIPA buffer (Thermo Scientific) and 1:500 protease inhibitor cocktail (Abcam) for 1 min. Sterile cell scrapers were used to scrape cells from the cell culture dish. Cells suspended in RIPA buffer were then vortexed for 30 min at 4°C and spun down at 14.1 rcf for 20 min. The supernatant was saved from each group and protein concentration was assayed using a BCA kit (Thermo Scientific).

Western blot.

NG2 lysates were denatured with β-mercaptoethanol at 80°C for 10 min. Ten micrograms of protein was run on a 7.5% TGX gel (Bio-Rad) for 1.5 h at 125 V. Transfer occurred overnight at 12 V on PVDF membranes. PVDF membranes were blocked (Thermo Scientific Super Blocker) for 1 h shaking at room temperature and incubated at 4°C overnight with an NG2 antibody (NG2; Millipore). The membrane was then washed with 1× PBS and 0.1% Tween 20 three times for 15 min each at room temperature while shaking. Anti-rabbit HRP antibody (Millipore Bioscience Research Reagents) was added for2 h, shaking at room temperature. Thermo Scientific ECL was then used to develop the blot. Then the blots were washed in PBS-Tween 20 and incubated on an orbital shaker in Thermo Scientific Restore Stripping Buffer for 15 min at room temperature followed by three washes with PBS-Tween 20 for 15 min each. Blots were then blocked using Thermo Scientific Blocking Buffer for 2 h at room temperature on the orbital shaker before incubation with primary antibody anti-2B6 (Seikagaku; 1:1000 dilution) overnight at 4°C. Before development with ECL Western blotting substrate, blots were incubated with an HRP-conjugated secondary antibody for 2 hat room temperature after three 15 min washes with PBS-Tween 20.

Cortical neuron culture and entrapment assay.

Coverslips were coated with PLL then bathed in laminin substrates of various concentrations (0 μg/ml, 1 μg/ml, or 5 μg/ml) for 2 h at 37°C. Adult mouse spinal cord NG2+ cells were plated on the coverslips at a density of 10,000 cells/coverslip and incubated at 37°C for 24 h. Whole cortices of 0- to 4-d-old BALBC/B6/129S mice (The Jackson Laboratory) were dissected in a bath of HBSS and kynurenate and incubated in a solution containing Papain, kynurenate, and cysteine for 30 min at 37°C. The neurons were then washed in HBSS-CMF, triturated, and filtered. After a brief low-speed centrifugation, the dissociated neurons were resuspended in Neurobasal A media containing B-27 supplement, GlutaMAX, and penicillin–streptomycin (Invitrogen) and plated on coverslips at a concentration of 2000 cells per coverslip. Coverslips were treated with an anti-mitotic agent (5′fluoro-2′-deoxy-uridine/uridine) at the time of neuron plating and chondroitinase ABC was added in the media (0.1 U/ml; Seikagaku) where indicated. Coverslips were incubated for 24 h before fixing with 4% paraformaldehyde and immunostained.

Dorsal column crush, double-conditioning lesion, and axon labeling.

All surgeries were performed in accordance with procedures and protocols of the Animal Resource Center of Case Western Reserve University. Female adult Sprague Dawley rats (250–300 g) were given a dorsal column crush injury as described previously (Horn et al., 2008). Briefly, while the animals were anesthetized using inhaled isoflurane gas (2% in oxygen) and under aseptic technique, a T1 laminectomy was performed to expose the dorsal aspect of the C8 segment. The tines of Dumont #3 jeweler's forceps were inserted through a hole in the dura 1.5 mm apart and 1 mm deep. The cord was then crushed three times for 10 s each to create the lesion. Gel film was placed over the site of injury and the muscle layers were sutured with 4-0 nylon suture. Surgical staples were used to close the skin, at which time the animals received Marcaine (1.0 mg/kg) subcutaneously and buprenorphine (0.1 mg/kg) intramuscularly. Using 3000 MW Dextran-Texas Red (Invitrogen), axons were labeled through the right sciatic nerve 2 d before killing the animal. The animals were killed at 7 d, 14 d, 21 d, or 28 d (N = 6/group). The tissue was then used for either immunohistochemistry or electron microscopy. For the double-conditioning lesion studies, the dorsal column crush (DCC) procedure was performed, as mentioned above, and immediately following the injury, the right sciatic nerve was exposed and crushed. One week later, the right sciatic nerve was re-exposed and crushed a second time, 1 mm proximal to the previous nerve crush. Two weeks later (3 weeks total), the animals were labeled, perfused, and sectioned as described above.

Because NG2 staining declines over time, we conducted studies in parallel on mice expressing enhanced green fluorescent protein under an NG2-promoter. These were obtained from Dr. Dwight Bergles (Department of Neuroscience, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD). The NG2 knock-out experiments were performed on NG2 knock-out mice obtained from Dr. William Stallcup (Sanford-Burnham Medical Research Institute, La Jolla, CA). For these experiments, the DCC was performed at T12 and animals were killed after either 14 d or 28 d.

In the double-conditioning experiments, SV2 expression was compared qualitatively. Tissue from five different mice was examined for visible SV2 staining in Dextran-labeled fibers found rostral to the lesion compared with those that remained within or caudal to the lesion.

Immunohistochemistry.

The animals were perfused with 4% PFA. The cord was postfixed in 4% PFA overnight, followed by submersion in 30% sucrose overnight. The tissue was frozen in OCT mounting media and sectioned on a cryostat into 20 μm longitudinal sections. The sections were stained with anti-GFAP (Accurate Chemical and Scientific Corporation), anti-SV2 (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank), anti-PSD-95 (Abcam), anti-SNAP-25 (Sigma), anti-vimentin (Sigma), anti-NG2 (Millipore), or anti-fibronectin (BD Biosciences), followed by either Alexa Fluor 405, 488, or 633. Images were obtained using a Zeiss LSM510 confocal microscope.

Quantification of dystrophic endings in contact with NG2+ cells.

Tissue was used from four rats. The animals were skilled 7 d after injury as described above. Z-stack images were obtained using a Zeiss LSM510 confocal microscope. The number of Dextran-Texas Red-labeled endballs in contact with an NG2+ cell were counted and compared with the total number of endballs observed.

Electron microscopy.

For TEM analysis, cells were seeded onto a sterilized ACLAR Embedding Film (Electron Microscopy Sciences), which was cut into pieces of appropriate size to fit a 24-well plate. Adult NG2+ cells were plated on 1 μg/ml laminin at a concentration of 40,000 cells per coverslip. Twenty-four hours later DRGs (3500 per slip) were added to the coverslip and cultures were placed in a 37°C, 10% CO2 incubator and allowed to reach ∼80% confluence. After the cells had reached this level of confluence (either 3 d or 5 d in coculture), the ACLAR sheets with their attached cells were immersed in fixative. The initial fixative was 2.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 m cacodylate buffer, pH 7.3. The specimen was postfixed in ferrocyanide-reduced 1% osmium tetroxide (Karnovsky, 1971). After a soak in acidified uranyl acetate (Tandler, 1990), the specimen was dehydrated in ethanol, passed through propylene oxide, and embedded in Poly/Bed. Thin sections were stained first with acidified uranyl acetate in 50% methanol (Tandler, 1990), then with the triple lead stain of Sato as modified by Hanaichi et al. (1986). These sections were examined in a JEOL 1200 EX electron microscope.

Statistical analysis.

All experiments were conducted in triplicate and repeated at least twice. The investigator was blinded before analyzing the data. Data were analyzed by the Student's t test, the two-proportion test, or two-way ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc test using Minitab 15 Software, or with the Kruskal–Wallis test followed by the Mann–Whitney U test with SPSS, as appropriate. All data are presented as mean ± SEM. Differences were considered statistically significant when the p value was <0.05.

Results

Dystrophic axons stabilize and persist on NG2+ cells at the caudal end of the lesion penumbra

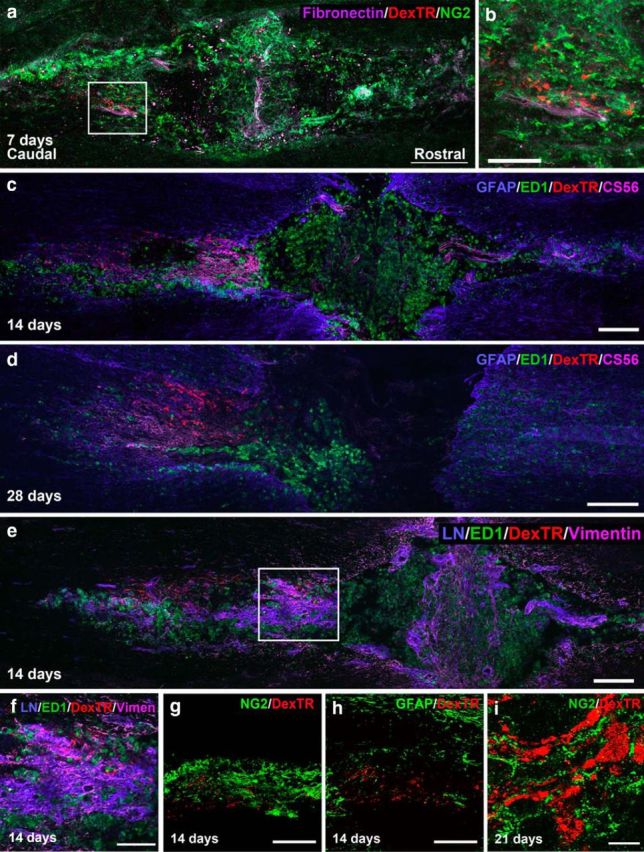

In our previous study, we observed that injured sensory axons associate closely with NG2+ cells, rather than astrocytes, at the caudal end of the lesion after macrophage-mediated dieback (Busch et al., 2010), expanding upon the work by McTigue et al. (2006). Two days after injury, GFAP+ and vimentin+ cells intermingled throughout the lesion. However, by 7 d after injury, the staining pattern of these two markers became largely mutually exclusive. Vimentin+ cells expanded within the lesion core, while GFAP+ astrocytes pulled away from the lesion center. Further characterization of these vimentin+ cells revealed significant overlap between vimentin (an intermediate filament marker and marker of progenitor cells), the progenitor marker nestin, and NG2. Here, we observed that the majority of dystrophic axons begin to associate with NG2+ cells as early as 7 d after a DCC injury in the rat (Fig. 1a; 138 of 143 fibers). At 14 d after injury, labeled fibers were found in the penumbra of the lesion in an area of high vimentin/CS56 expression, minimal GFAP expression, and abundant ED1+ activated macrophages (Fig. 1c,e). Although ED1 is found in the vicinity of the labeled fibers at the caudal end of the lesion, the fibers were more closely associated with CS56 staining, which becomes more obvious at 28 d after injury when macrophages (which do not express CS56) begin to leave the lesion area (Fig. 1d). High levels of the ECM molecules fibronectin and laminin in association with NG2+ cells were also found within the lesion core, in the vicinity of the dystrophic endings (Fig. 1a,b,e,f). These ECM molecules provide a favorable substrate for dystrophic axons (Yang et al., 2006; Busch et al., 2010). At 14 d after injury, the labeled axons were still closely associated with NG2+ cells within the lesion epicenter (Fig. 1g) but not with GFAP+ astrocytes that formed a wall around the perimeter of the injury site (Fig. 1h). The fibers remain associated with NG2+ cells even at 21 d after injury (Fig. 1i).

Figure 1.

Injured fibers remain associated with NG2+ cells for several weeks after injury. a, Confocal montage of a longitudinal section through the injured section of rat cord, 7 d after injury. At 7 d after injury, Dextran-Texas Red (DexTR)-labeled fibers of dystrophic axons (red) can be found caudal to the lesion, in an area rich in NG2 (green) and fibronectin (purple). The slice is oriented with the rostral end of tissue to the right and caudal to the left throughout the paper, unless otherwise noted. b, High magnification of the area outlined in a. c, Dextran-Texas Red-labeled fibers remain in the penumbra of the lesion, in an area rich in CS56, with some GFAP and ED1 expression. The fibers are associated most closely with CS56 expression. d, At 28 d after injury, the fibers remain in this area, even as ED1 expression is reduced. e, Fourteen days after injury these fibers are also found in an area rich in laminin and vimentin. f, High magnification of the area outlined in e. g, At 14 d after injury, the fibers are still associated with NG2+ cells (green) in the lesion, but not with astrocytes labeled with GFAP (green) at the caudal end of the lesion (h), where the majority of the fibers have stabilized. i, Close association with NG2+ cells persists at 21 d after injury. Scale bars: a, c–e, g, h, 200 μm; b, i, 10 μm; f, 100 μm.

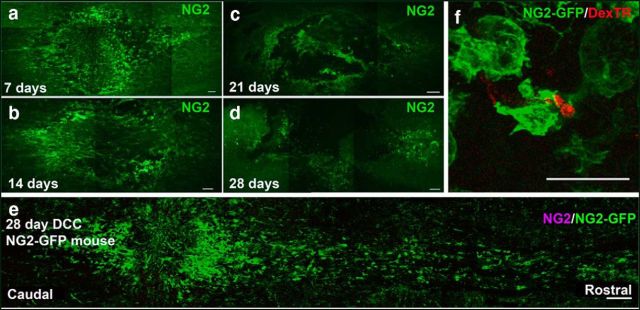

Within the first few days after injury, NG2+ cells in the vicinity of the lesion increase their immunoreactivity to the NG2 antibody relative to those in uninjured tissue (Levine, 1994). Although NG2 is expressed throughout the entire spinal cord under normal conditions, the injury-induced increase in NG2 expression on the cell surface makes immunohistochemical detection of NG2 around the lesion readily possible. Confirming previous studies in SCI (McTigue et al., 2001; McTigue et al., 2006; Jones et al., 2002), following DCC in rat, NG2 expression increased within the lesion and peaked 14 d after injury (Fig. 2 a,b). However, 28 d after injury, immunohistological detection of NG2 was greatly diminished (Fig. 2d), so it was difficult to determine whether dystrophic axon tips remained associated with these cells longer term. Using mice that express GFP under an NG2 promoter, cells that produce NG2 persist in the lesion core and penumbra even at 28 d after DCC injury. Injured axons remain associated with these cells, although the expression of NG2 itself declines over time as in rat (Fig. 2e,f). Although in mice the lesion after DCC is more disk shaped and cavitation does not occur as it does in the rat, the continuing close association between dystrophic axon tips and NG2 glia is comparable to that which occurs in the rat.

Figure 2.

NG2 expression declines over time, but formerly expressing NG2-cells remain in the lesion. a–d, Level of NG2 expression at 7 (a), 14 (b), 21 (c), and 28 d (d) after injury in rat. e, A montage of the lesion in an NG2-lck-eGFP mouse 28 d after injury. Even small amounts of NG2 promoter activity are able to drive large amounts of GFP expression. f, A z-stack projection of a fiber enwrapped by a GFP+ cell at the caudal end of the lesion, 28 d after injury, from a different slice than that imaged in e. Scale bars: e, 200 μm; a–d, 100 μm; f, 25 μm. DexTR, Dextran-Texas Red

The NG2+ cell surface is a preferred substrate for DRG axon growth

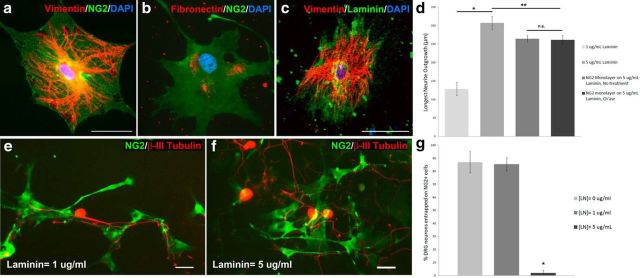

Since their discovery, there has been controversy as to whether NG2+ cells are growth inhibitory or promoting. To address this question, we used an NG2+ cell population from the adult mouse spinal cord. This isolated cell population expresses both NG2 and vimentin (98.2%; Fig. 3a). Because these cells do not express GFAP (4.6%) but they do express PDGFRα, Olig2, A2B5, and O4 (in later passages), these cells appear to be oligodendrocyte precursor cells (OPCs). These cells also express laminin and fibronectin on their surface, consistent with previous reports (Yang et al., 2006; Busch et al., 2010; Fig. 3b,c) and their phenotypes in vivo (Fig. 1). Previous characterizations of these cells suggest they have stem-like properties. A minority of them share some similarities with pericytes in early passages, as exemplified by their expression of α-SMA (<20% of cells), which is greatly reduced during later passages (Bai et al., 2013). Therefore, we used late-passaged NG2+ cells in vitro, suggesting an OPC phenotype. However, a possibility remains that there may be a minor contaminating NG2+ pericyte-like population. Thus, we will refer to these cells as NG2+ cells throughout the results.

Figure 3.

NG2+ cells provide a growth-permissive substrate. a, NG2+ cells also express vimentin (red), a progenitor marker. b, NG2+ cells express growth-permissive extracellular matrix molecules such as laminin (red) and fibronectin (red, c). d, Neurite outgrowth on the low-laminin substrate (1 μg/ml) was significantly lower than on the high-laminin substrate (5 μg/ml) or NG2+ cell monolayer. Outgrowth on the NG2+ cell monolayer was significantly less than on a high-laminin substrate. No significant difference in outgrowth was observed on the NG2+ cell monolayer with or without ch'ase treatment. Kruskal–Wallis test, Mann–Whitney U test; n = 33 (1 μg/ml laminin), 97 (5 μg/ml laminin), 176 (NG2 monolayer, no treatment), 174 (NG2 monolayer, ch'ase); *p < 0.0005, **p < 0.015. H(3) = 43.57. e, Neurons whose cell bodies begin on the surface of an NG2+ cell remain on the NG2+ cell surface and do not extend processes off onto a low-laminin (1 μg/ml) substrate. f, DRG neurons beginning on an NG2+ cell surface can extend neurites off the NG2+ cell onto a high-laminin (5 μg/ml) substrate. g, The percentage of DRG neurons per coverslip that began on the surface of an NG2+ cell and did not extend neurons onto the laminin background at different laminin concentrations was calculated. Neurons remain entrapped on the surface of the NG2+ cell when laminin concentrations are at 1 μg/ml or below. One-way ANOVA, Tukey post hoc test, n = 6 coverslips per condition, *p < 0.02. F(9) = 36.41. Scale bar: 50 μm.

To address the question of whether NG2+ cells are growth inhibitory or growth permissive, we compared the length of neurite outgrowth of adult DRG neurons on various substrates. Because laminin is known to be a favorable substrate for neurite outgrowth, we compared the longest neurites of DRG neurons grown on a low concentration of laminin (1 μg/ml), a high concentration of laminin (5 μg/ml), and a monolayer of NG2+ cells (Figs. 3d, 6a,c). Neurite outgrowth on the low-laminin substrate was significantly lower than on the high-laminin substrate or the NG2+ cell monolayer. However, outgrowth on the high-laminin substrate was only marginally better than on the NG2+ cell monolayer. Because the inhibitory properties of CSPGs are often attributed to their GAG side chains, we also compared neurite outgrowth on confluent NG2+ cell monolayers with or without treatment with chondroitinase ABC (ch'ase). Ch'ase is an enzyme that cleaves the inhibitory GAG chains and has been reported to improve neurite outgrowth on CSPG-containing substrates (Snow et al., 1990; Bradbury et al., 2002; Shen et al., 2009). Surprisingly, no significant difference in outgrowth was observed on the NG2+ cell monolayer with ch'ase treatment (Fig. 3d). Although neurons are capable of considerable growth on the confluent NG2+ cell monolayer, they do not adhere to or grow well upon a uniform substrate of pure NG2 proteoglycan (7 μg/ml; data not shown), confirming previous studies reporting the inhibitory nature of this CSPG (Dou and Levine, 1994; Fidler et al., 1999; Ughrin et al., 2003). These data are consistent with the current thinking that although the NG2 proteoglycan may be inhibitory, the NG2+ cell surface is more complex and therefore may not be repulsive as previously thought.

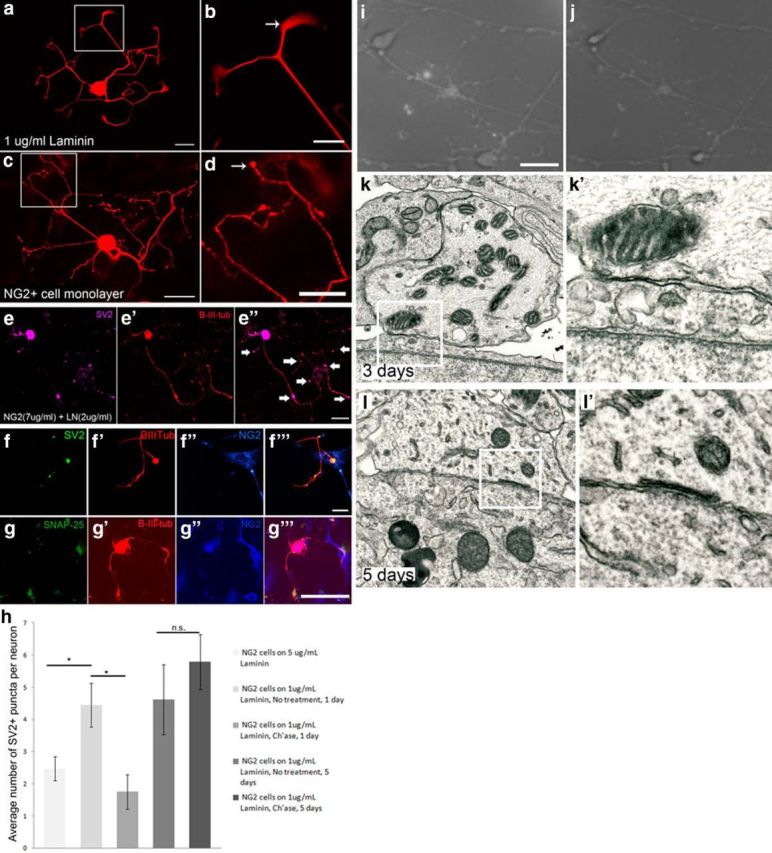

Figure 6.

NG2+ cells and adult DRG neurons form synaptic-like connections in vitro. a, Dissociated neurons growing on a uniform laminin substrate extend many neurites with lamellipodia at the growth cones. b, Inset from a, showing a growth cone. c, Neurons have a different morphology when growing on an NG2+ cell monolayer. Neurons appear to have en passant synapses along their neurites. d, Inset from c, showing bulb endings. e, An adult DRG neuron growing on a uniform substrate of NG2 (7 μg/ml) and laminin (2 μg/ml) has SV2 accumulation in puncta along its processes. f, DRG neurons growing on sparsely plated NG2+ cells for 2 d begin to express SV2+ puncta along their processes where the neurites contact NG2+ cell processes. g, An adult DRG neuron expresses the presynaptic marker, SNAP-25, when it contacts an NG2+ cell in culture. h, Quantification of the number of SV2+ puncta in a DRG neuron in a defined area when grown on an NG2+ cell monolayer for 1 and 5 d. One-way ANOVA, Tukey post hoc test, n = 40 (NG2 cells on 5 μg/ml LN, 1 d),18 (NG2 cells on 1 μg/ml LN, 1 d, no treatment), 29 (NG2 cells on 1 μg/ml LN, 1 d, ch'ase),18 (NG2 cells on 1 μg/ml LN, 5 d, no treatment), 23 (NG2 cells on 1 μg/ml LN, 1 d, ch'ase); *p < 0.0005 F(4) = 6.20. i, DRG neuron growing on an NG2+ cell monolayer for 5 DIV after high K+ stimulation in the presence of FM dye. j, The same neuron imaged in i after another high K+ stimulation without dye, showing a reduction in fluorescence. k, Electron micrograph image of a neuron in close association with an NG2+ cell after 3 d in coculture. k′, Higher magnification of the area boxed in k. l, Electron micrograph of a neuron in close association with an NG2+ cell after 5 d in coculture. L′, Boxed area in l, showing a subsurface cistern in the neuron. Scale bars: a, c, e, f, g, 50 μm; b, d, i, 25 μm.

NG2+ cells constrain then entrap DRG neurons on their surface

Because the surface of the NG2+ cell was permissive to DRG neurite outgrowth, we sought to explore whether sensory neurons would grow on NG2+ cells or laminin preferentially when given a choice. We plated NG2+ cells at a subconfluent density on PLL-coated coverslips containing no laminin, low laminin (1 μg/ml), or high laminin (5 μg/ml). Adult DRG neurons were added to the cultures 24 h later. After an additional 24 h, the cocultures were analyzed to determine whether neurons with cell bodies lying on an NG2+ cell extended processes that remained on that NG2+ cell or could abandon the cell and extend neurites onto the laminin substrate. When the coculture was grown on either PLL alone or low laminin, the neurons tended to confine their growth to the NG2+ cell surface (Fig. 3e,g). In contrast, when the coculture was grown on a high-laminin substrate, the neurons freely extended neurites off the NG2+ cell surface onto the laminin background (Fig. 3f,g). Thus, DRG neurons prefer to grow on NG2+ cells and become predominantly confined to their surface when grown on a less permissive substrate such as PLL or low laminin.

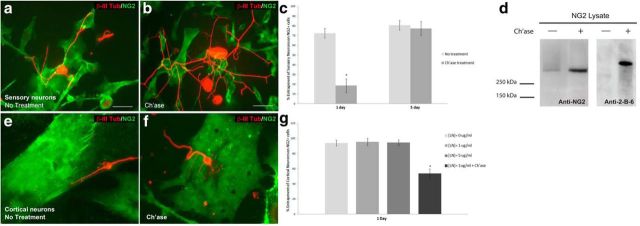

Chondroitinase treatment early on releases DRG neurites from the NG2+ cell surface

Because GAGs are known to be inhibitory, we hypothesized that treatment with ch'ase would make the NG2+ cell surface even more favorable, such that neurites would rarely grow off onto the low-laminin (1 μg/ml) background. Again, NG2+ cells were plated at a subconfluent density, such that they did not reach confluency during the course of the experiment. Neurons were added 24 h later. Without an NG2+ cell monolayer, the neurons had a choice to extend neurites on or off the NG2+ cell surface. Surprisingly, in 24 h cocultures, the addition of ch'ase at the time of plating DRG neurons with NG2+ cells released the neurites from the NG2+ cell surface (Fig. 4a,b) even onto a low-laminin substrate. These data suggest that the presence of GAG chains of CSPGs, NG2, and possibly other CSPGs on the NG2+ cell surface such as versican (Asher et al., 2002), play a role in constraining neurites. Unlike on the monolayer, where ch'ase treatment had no effect on growth (Fig. 3d), here ch'ase allowed processes to extend onto an alternative substrate so they were no longer confined to the limited area of the NG2+ cell. Interestingly, when the two cell types were cocultured for an extended period of time (5 DIV), the neurites of DRG neurons were no longer able to extend off the NG2+ cell surface, despite daily ch'ase treatment (Fig. 4c). Because NG2 is a part-time proteoglycan, we performed a Western blot to confirm that NG2 was glycosylated on the surface of the NG2+ cells. Using an NG2+ cell lysate probed with an NG2 antibody, a high molecular weight smear was observed at ∼300 kDa. Importantly, this smear became a single focused band when the cells were pretreated with ch'ase, indicating that NG2 is in fact glycosylated (Fig. 4d). It is important to note that other proteoglycans are also known to be expressed on the NG2+ cell surface and may also play a role in mediating entrapment. To demonstrate this as a possibility in our system, the blot was stripped and reprobed for 2B6, a stub antigen that is exposed after ch'ase treatment. Indeed, this procedure revealed a new band at a higher molecular weight than when the blot was probed for NG2, suggesting that there are other proteoglycans present on the NG2+ cell. Their abundance and entrapping potency relative to NG2 is unknown.

Figure 4.

Chondroitinase treatment reverses entrapment. a, When NG2+ cells and DRG neurons are cocultured on low-laminin (1 μg/ml) substrates, the neurons usually do not extend processes off the surface of the NG2+ cell. b, Chondroitinase treatment (0.1 U/ml) at the time of DRG plating allows neurites to extend onto the laminin substrate more frequently. c, The percentage of neurons that begin on the NG2+ cell surface and are unable to extend processes onto the laminin substrate was significantly reduced when the cocultures were treated with ch'ase (0.1 U/ml) before DRG plating when cocultured for 1 DIV. At 5 DIV, neurites are unable to extend off the NG2+ cell surface, even after ch'ase treatment. Two-proportions test, n = 106 (1 d, no treatment), 160 (1 d, ch'ase), 90 (5 d, no treatment), 71 (5 d, ch'ase); *p < 0.0005, p = 0.828, z = 11.16, 0.22. d, A Western blot using protein from NG2+ cell lysate reveals a high molecular weight smear ∼300 kDa in lane 2. Lane 1 contains a protein ladder with a band at 250 kDa. Lane 2 contains lysate from NG2+ cells without treatment and lane 3 contains lysate from NG2+ cells pretreated with ch'ase for 1 h, which removes the smear. e–g, Cortical neurons (stained with β-III-tubulin, red) cocultured with NG2+ cells for 24 h become entrapped, just as the adult DRG neurons in a. e, A cortical neuron whose cell body begins on the surface on an NG2+ cells (green) becomes entrapped on the NG2+ cell surface and does not extend processes onto the low-laminin substrate (1 μg/ml). f, When cocultures are treated with ch'ase at the time of neuronal plating, neurites extend off the NG2+ cell surface onto low laminin. g, Quantification of the percentage of neurons per coverslip that become entrapped on the NG2+ cell. Ch'ase treatment at 1 DIV allows neurites to extend onto laminin. Units are percentage entrapment per coverslip and data are presented as mean + SEM; *p value < 0.05. Scale bars: a, b, 50 μm.

We next tested another neuronal subtype to see if this constraining phenomenon was unique to sensory neurons or translates to CNS neurons as well. To test the generality of this observation, we isolated cortical neurons from P0–P1 mouse pups and cocultured them with NG2+ cells on either no laminin (PLL alone), low laminin (1 μg/ml), or high laminin (5 μg/ml), as described above. After 24 h, the cocultures were fixed and examined to see if the processes of cortical neurons whose cell bodies lie on the surface of an NG2+ cell were able to extend onto the background substrate. Like the adult DRG neurons, neonatal cortical neurons also became constrained to the NG2+ cell surface when grown on no- or low-laminin surfaces (Fig. 4e,g). Interestingly, this phenomenon was even more robust for cortical neurons, which were unable to escape the NG2+ cell surface even when a high-laminin substrate was available (Fig. 4g). However, importantly, as observed with DRG neurons, the processes of cortical neurons were able to extend off the NG2+ cell surface after 24 h when the cultures were treated with ch'ase (Fig. 4f,g). These data suggest that constraint upon NG2+ cells may not be unique to sensory neurons.

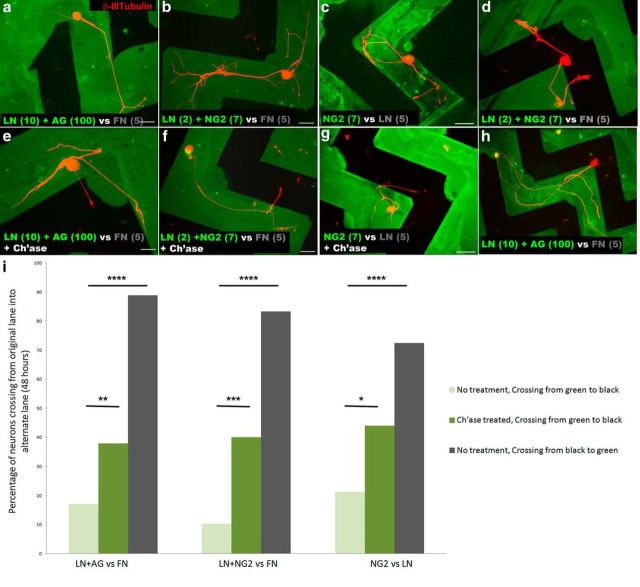

The balance between laminin/fibronectin and proteoglycan can regulate constraint upon CSPGs

To understand better the constraining phenomenon, we examined axon growth on various mixtures of ECM molecules expressed on the NG2+ cell surface. In addition to laminin and NG2, these cells also express fibronectin (Fig. 3b). All three of these ECM molecules are also highly expressed within the vicinity of the lesion core (Fig. 1a,b,e,f). If neurons regrow beyond the lesion core, the next potential cell type they would encounter would be reactive astrocytes, which express other types of CSPGs and low levels of fibronectin, but little or no laminin (Tom et al., 2004a). We hypothesized that the balance between growth-promoting molecules and the NG2 proteoglycan might be responsible for restricting neurite outgrowth to the NG2+ cell surface. To test this hypothesis, we used purified ECM molecules in stripe assays to mimic the in vivo patterning of these substrates in vitro, consisting of two sets of cues arranged in alternating stripes. In this assay, the first substrate, in this case a laminin-proteoglycan mixture, is adhered to the coverslip and then the entire coverslip is bathed in a second substrate. We used two different proteoglycans to address this hypothesis: NG2, which only has a single GAG chain (Stallcup and Dahlin-Huppe, 2001), and aggrecan, which contains a large number of GAG side chains (Kiani et al., 2002). We used fibronectin as the second substrate, which added a third component to the laminin-proteoglycan lanes and comprised the entirety of the alternate lanes. When DRG neurons were added to the coverslips, they preferentially grew in the laminin-proteoglycan-fibronectin lanes over the lanes containing only fibronectin (Fig. 5a,b,i). However, when the coverslips were treated with ch'ase before DRG plating, the neurons readily extended neurites off the proteoglycan-containing lanes onto the fibronectin-only substrate, implicating the proteoglycan in the constraint of neurites (Fig. 5e,f,i). This result was observed when either NG2 or aggrecan was used.

Figure 5.

Proteoglycans play a role in entrapping neurons. DRG neurons were plated on striped substrates, given the choice between a laminin-proteoglycan lane (green) and a fibronectin (FN) or laminin-only background (black). a, b, Neurons prefer to grow in the laminin-proteoglycan (a, aggrecan, 100 μg/ml; b, NG2, 7 μg/ml) lane, rather than the fibronectin-only lane (5 μg/ml). c, Neurons preferentially grow in lanes containing only NG2 (7 μg/ml), rather than laminin-only (5 μg/ml). d, When the cell bodies of neurons begin in the lane containing fibronectin only, they freely extend into and out of the various lanes. e–g, When cultures were ch'ase treated (0.1 U/ml) at the time of plating DRG neurons, neurons extend processes onto the fibronectin (e, f) or laminin (g) background. h, When a neuron beginning on laminin only projects for an extended period in the CSPG-containing lane, it becomes entrapped. i, The percentage of neurons beginning in a green lane and extending neurites from the green to the black substrate were quantified. The same was done for those crossing from black to green when cell bodies began in the black lane. Two-proportions test, n = 85 (LN/AG vs FN, no treatment), 53 (LN/AG vs FN, ch'ase), 9 (LN/AG vs FN, no treatment, crossing black to green) 39 (LN/NG2 vs FN, no treatment), 25 (LN/NG2 vs FN, ch'ase), 12 (LN/NG2 vs FN, no treatment crossing black to green), 80 (NG2 vs LN, no treatment), 25 (NG2 vs LN, ch'ase), 40 (NG2 vs LN, no treatment, crossing black to green). Two-proportions test, *p = 0.037,**p = 0.026, ***p = 0.005, and ****p < 0.0005. z= −2.23, −4.08, −2.81, −4.96, 2.08, −6.09. Scale bar, 50 μm. AG, aggrecan.

To provide further evidence that proteoglycan rather than laminin is responsible for this growth preference in the laminin-proteoglycan lane, we simplified the system further. First, the NG2 proteoglycan alone was adhered in lanes, then the entire coverslip was bathed in laminin, resulting in a choice assay between NG2-laminin versus laminin only. Again, neurons initiating growth from within the NG2/laminin lanes preferentially grew in the lanes containing NG2 (Fig. 5c,i). Ch'ase treatment before DRG plating allowed the neurons to leave the proteoglycan-containing lanes and extend their processes freely onto the laminin-only lanes (Fig. 5g,i). Neurons did not adhere well to the lanes containing only aggrecan, rather than an aggrecan-laminin mixture, confirming the inhibitory nature of this proteoglycan.

Interestingly, those neurons with cell bodies situated in the laminin-only lanes (Fig. 5d,i) or fibronectin-only lanes, where no proteoglycan was present, extended processes that freely crossed onto but then off of the proteoglycan-containing lanes. Neurons that initiate growth on a permissive ECM do not become constrained when they subsequently enter the proteoglycan-rich terrain. On occasion, neurons with cell bodies in a proteoglycan-free lane would extend long processes into a proteoglycan-containing lane and then appear to also become constrained, suggesting that the length of time on proteoglycan may also be important (Fig. 5h). Additionally, when higher concentrations of NG2 were used (8 μg/ml, 10 μg/ml, or 12 μg/ml), the neurons did not adhere or extend processes as well, consistent with previous studies suggesting a more repulsive type of inhibitory nature of CSPGs (data not shown).

Confinement leads to synaptic-like formations and entrapment

Ch'ase was only able to reverse confinement acutely (24 h), but not after cells had been cocultured for 5 d, suggesting that the connection between the neuron and NG2+ cell eventually becomes even more stable, perhaps through a molecular mechanism distinct from that mediated via CSPGs. While comparing DRG neurite outgrowth on a pure laminin substrate (1 μg/ml) to outgrowth on an NG2+ cell monolayer, we observed a profound difference in neuronal morphology. The neurons growing on laminin extended smooth processes with growth cones containing lamellipodia at their tips (Fig. 6a,b). In contrast, all neurons growing on the NG2+ cell monolayer developed beaded, bouton-like swellings along their processes (Fig. 6c,d). When DRG neurons were cocultured with subconfluent NG2+ cells, discrete puncta of synaptic vesicle 2 (SV2) expression were observed at select points along the neurite where they contacted the surface of the NG2+ cell (Fig. 6f). Similar puncta could even develop when neurons were cultured on a uniform substrate consisting of purified NG2 (7 μg/ml) and laminin (2 μg/ml; Fig. 6e). We compared the levels of SV2 expression in neurons grown for 2 d or 5 d on laminin, an NG2+ cell monolayer, or an NG2+ cell monolayer treated acutely with ch'ase (Fig. 6h). After 2 d, when neurons were grown on laminin, SV2 expression was evenly distributed throughout the entire length of the neurites, but when DRG neurons were cocultured on an NG2+ cell monolayer, discrete puncta of SV2 expression were observed (Fig. 6h). After ch'ase treatment in 2 d cultures, such synaptic-like puncta along the neurite were significantly reduced (Fig. 6h). However, ch'ase had no significant effect on the number of SV2+ puncta in 5 d cultures, suggesting that by 5 DIV the neurons had formed stable, synaptic-like connections with NG2+ cells. The presynaptic marker, SNAP-25, also accumulated in the endings of cultured neurons when the processes terminated on an NG2+ cell (Fig. 6g). These data further suggest that the NG2 proteoglycan not only plays a role in entrapping neurons onto the cell surface of NG2+ cells, but also functions in facilitating or initiating formation of synaptic-like connections between these two cell types.

To test the functionality of these connections, we imaged synaptic vesicle recycling in 5 d cocultures of NG2+ cells and adult DRG neurons. After the cells had been cocultured for 5 d, they were stimulated with high K+ in the presence of FM dye for 3 min. During this time, the dye is taken up by the neurons in vesicles. The coculture was washed with low Ca2+ and then ADVACEP, to quench any background fluorescence, followed by an additional low Ca2+ wash. Next the cells were imaged under fluorescence. The cultures were then stimulated with a high K+ solution again, but this time without dye, and imaged once more. If synaptic vesicles exocytose, the dye will be released into the solution, causing the fluorescence of the neuron to decrease. Indeed, the fluorescence of the neurons significantly decreased upon stimulation without dye, suggesting that these neurons had formed functional synaptic-like contacts with NG2+ cells in culture (average pixel intensity: stimulation with dye 90.1 ± 13.4, stimulation without dye 75.81 ± 11, two-sample t test, n = 16 per condition, *p = 0.003. t(28) = 3.30; Fig. 6i,j).

We next examined these connections at the ultrastructural level. DRG neurons were cocultured on NG2+ cell monolayers for either 3 d or 5 d, then processed for electron microscopy. At 3 d, the membranes of the NG2+ cells and the neurons were in close proximity, but no classic synaptic specializations were observed (Fig. 6k). At 5 d, we observed subsurface cisterns, which have been suggested to alter the neuronal cell body in preparation for synapse formation (Sumner, 1975), throughout the presynaptic membranes of the neurons (Fig. 6l). Therefore, these structures may represent early markers of synaptic-like formations that need to be further explored at the ultrastructural level.

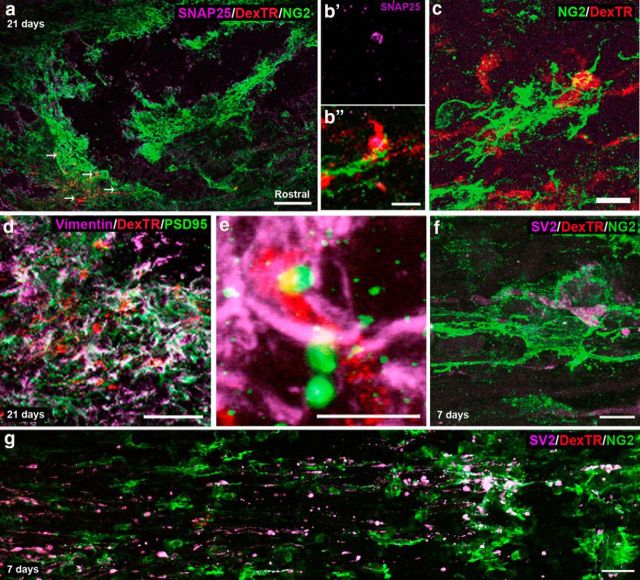

Dystrophic axons form synaptic-like connections on NG2+ cells in vivo

Several studies have reported that neurons normally form synapses with NG2+ cells in various areas of the CNS (Bergles et al., 2000; Gallo et al., 2008). Because dystrophic axons persist on NG2+ cells and form synaptic-like contacts in culture, and because severed axon tips persist in the vicinity of NG2+ cells for extended periods of time after SCI, we hypothesized that this stable interaction might be the result of synaptoid formation between these two cell types within the lesion environment. NG2+ cells were still tightly associated with labeled dystrophic axon tips (Fig. 7c) 21 d after injury. The presynaptic marker, SNAP-25, accumulated in endings of dystrophic axons in association with NG2+ cells (Fig. 7a,b) 21 d after injury. PSD-95 expression was observed only in vimentin+ cells closest to the lesion core, in the area where dystrophic endings stabilize (Fig. 7d,e). The predominant cell population expressing vimentin within the lesion environment also expresses NG2, but has little overlap with GFAP (Fig. 1). We examined the expression of SV2 at various time points (7, 14, and 21 d) after SCI. As a synaptic vesicle marker, SV2 expression is detected throughout the labeled processes, as would be expected for cycling vesicles. In all animals, SV2 accumulated densely in the dystrophic endballs of Dextran-labeled regenerating axons in contact with NG2+ cells (Fig. 7f,g). To further confirm synapse-like formation between dystrophic endballs and NG2+ glia in vivo, we attempted immunoelectron microscopy, labeling the NG2+ cells with immunogold and the dystrophic fibers with biotinylated Dextran-Texas Red for HRP staining. Despite numerous attempts (six different cohorts of animals at various time points), while we were able to find close contacts between the two cell types, we were unable to uncover definitive synaptic-like structures akin to those described in normal brain tissue (Bergles et al., 2000). However, after injury, these synaptic-like contacts may be less mature or may differ in appearance from those seen in normal tissue. Therefore, further characterization is necessary to better understand the morphological appearance of these contacts at the ultrastructural level.

Figure 7.

NG2+ cells and dystrophic axons colocalize with synaptic markers in vivo. Dystrophic axons stabilize on NG2+ cells at the caudal end of the lesion after spinal cord injury and begin to form synapses. a, Montage of confocal images of a longitudinal section of the lesion 21 d after injury. Endballs of retrogradely labeled fibers are found associated with NG2+ cells at 21 d after a dorsal column crush. b, SNAP-25 accumulates in the endings of Dextran-Texas Red (DexTR)-labeled fibers. c, Projection of z-stack confocal images depicting an NG2+ cell enwrapping a Dextran-Texas Red-labeled fiber. d, Vimentin expression is highest adjacent to the lesion. PSD-95 expression is observed in vimentin+ cells where labeled fibers stabilize. e, Higher magnification, showing PSD-95 puncta accumulating in vimentin+ cells adjacent to stabilized fibers. f, Z-stack projection of a Dextran-Texas Red-labeled fiber expressing SV2 and enwrapped by an NG2+ cell. g, As early as 7 d after injury, SV2 accumulates in the endings of labeled fibers, caudal to the lesion. Scale bars: a,100 μm; d, g, 50 μm; b, 25 μm; c, e, f, 10 μm.

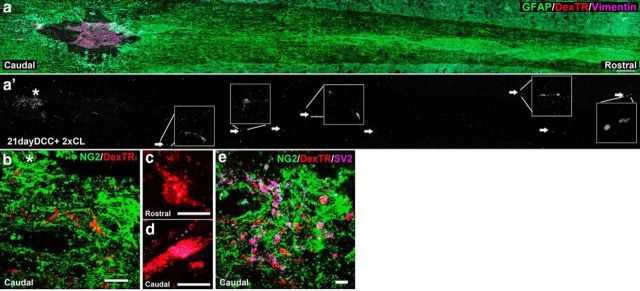

Enhancing intrinsic growth capacity reduces entrapment

Many previous studies have used conditioning or double conditioning of the sciatic nerve to enhance the regenerative capacities of injured neurons in the periphery as well as the dorsal columns (McQuarrie and Grafstein, 1973; McQuarrie et al., 1977; Richardson and Issa, 1984; Neumann et al., 2005). Conditioned neurons regenerate further within the CNS lesion and some can even extend beyond. To examine the presence or absence of synaptoids on NG2+ cells within and beyond the lesion after double conditioning, we performed a dorsal column crush, immediately followed by a sciatic nerve crush. One week later, the sciatic nerve was re-exposed and crushed again just proximal to the previous crush. The animals were allowed to recover for two additional weeks. Confirming the results of Neumann et al. (2005), several fibers regenerated a few millimeters beyond the lesion core. Within the lesion, the tips of nonregenerating fibers persist in an area low in GFAP (Fig. 8a) and remain associated with NG2+ cells (Fig. 8b). Interestingly, while there was much less SV2 in fibers that regenerated beyond the lesion (Fig. 8c; detectable SV2 was found in only 3 of the 34 tips examined), those fibers that still remained in the caudal penumbra of the lesion where NG2 was still expressed continued to produce high levels of SV2 (Fig. 8d,e; detectable SV2 was found in 41 of the 48 tips examined). These data suggest that conditioned fibers with enhanced regenerative capacities form less stable connections with NG2+ cells.

Figure 8.

Conditioned fibers beyond the lesion still associate with NG2+ cells. Double conditioning lesion (2xCL) of the sciatic nerve allows several injured fibers to grow beyond the lesion center 21 d after SCI. a, GFAP expression (green) shows the glial scar surrounding the lesion. Vimentin (purple) is expressed within the lesion center and the penumbra. Arrows show fibers that have grown rostral to the lesion. a′, Dextran-Texas Red (DexTR)-labeled fibers from image a. The boxes illustrate select fiber endings at higher magnification. b, Higher magnification of the area near the asterisk in a′ from a serial slice, demonstrating that the majority of Dextran-Texas Red-labeled fibers remain caudal to the lesion in association with NG2+ cells. NG2 (green) expression is found in the lesion center and throughout the tissue. The brightness in a and b differ, so that NG2 expression could be visualized. SV2 expression is found accumulated in the endings of fibers caudal to the lesion but not those that have crossed rostrally. c, Fiber rostral to the lesion without SV2 (purple) expression. d, Fiber from b caudal to the lesion, with SV2 expression in its ending. e, Z-stack projection of a Dextran-Texas Red-labeled fiber found rostral to lesion core associated with NG2 expression. Scale bars: a,100 μm; b, 50 μm; c, d,10 μm; e, 20 μm.

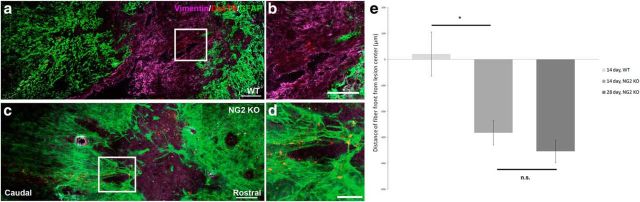

Knocking out NG2 in vivo alters entrapment

To further understand the role of NG2 after SCI, we performed a dorsal column crush in NG2- proteoglycan knock-out mice and compared them to wild-type littermates at 14 and 28 d after injury. We analyzed the position of the most rostral axon tip within the fiber front. The fiber front was defined as the area where the majority of the labeled fibers were found. Similar to results seen in de Castro et al. (2005), who examined calcitonin gene-related peptide-positive sensory afferents and serotonergic axons following injury in these KO mice, injured sensory fibers in the dorsal columns also did not cross the lesion. Rather, at 14 d after injury the fibers died back further in knock-out animals into the territory of reactive astrocytes (Fig. 9). This finding supports the hypothesis that NG2 is necessary to initiate the stabilization of injured axons after dieback. It is also interesting to note that the lesion core of NG2-KO animals is filled with vimentin+ cells at levels comparable to WT controls.

Figure 9.

Removal of NG2 causes increased dieback of sensory fibers after SCI. NG2 may be necessary to prevent further dieback after DCC. a, Dextran-Texas Red (DexTR)-labeled fibers are found within the lesion core of WT mice 14 d after DCC. b, Inset from a, showing where the majority of fibers stabilize in WT mice. c, DexTR-labeled fibers are found more caudal to the lesion in NG2-KO mice littermates. d, Inset from c, showing the majority of fibers in the KO animals are found caudal to the lesion, rather than within the lesion core. e, Quantification of the distance of the fiber front away from the lesion center. Two-sample t test, *p = 0.035, p = 0.302. t(4) = 3.13, t(7) = 1.11. Scale bars: a, c,100 μm; b, d,50 μm.

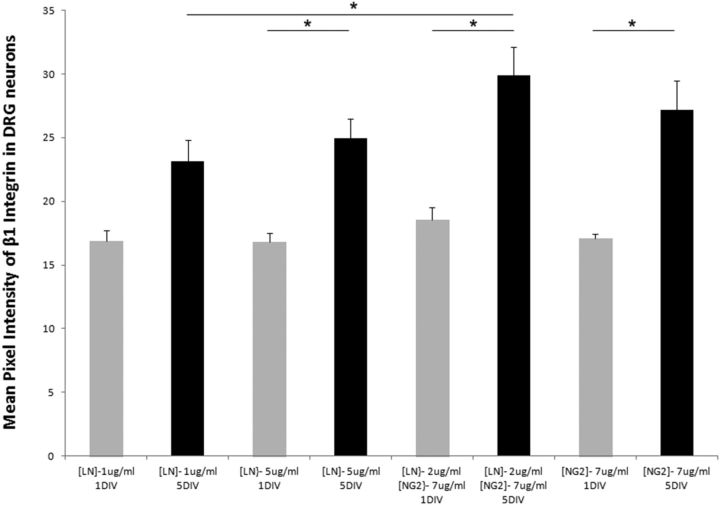

DRG neurons upregulate β1 integrin after 5 DIV on a laminin-NG2 mixture or NG2 alone

Because previous studies had demonstrated that proteoglycans upregulate neuronal integrin expression and increase cell adhesion on laminin (Condic et al., 1999), we asked if this was one of the underlying mechanisms that might lead to neurite entrapment on NG2+ cells. To address this question, we cultured adult DRG neurons on different purified uniform substrates, either low laminin (1 μg/ml), high laminin (5 μg/ml), NG2 alone (7 μg/ml), or a low laminin (LN)-NG2 mixture (LN = 2 μg/ml, NG2 = 7 μg/ml). While DRG neurons cultured for 24 h did not change integrin expression regardless of the substrate upon which they were plated, by 5 DIV DRG neurons cultured on high laminin, low-laminin-NG2 mixture, or the few that remained on purified NG2 did significantly upregulate integrin β1 expression (Fig. 10). Notably, although previously we observed that the growth of DRG processes was largely restricted to NG2+ cells by 24 h in vitro, integrin upregulation did not occur until 5 DIV, the period of entrapment.

Figure 10.

DRG neurons plated on an NG2 substrate upregulated integrin β1 after 5 DIV. At 1 DIV, there was no difference in integrin expression within the DRG neuron on any substrate. By 5 DIV, integrin expression significantly increased on high laminin, a laminin-NG2 mixture, or an NG2 only substrate. Units are mean pixel intensity per region. All data are presented as group mean + SEM, *p value < 0.05.

Discussion

It had long been thought that following axotomy, neurons with severed axons within CNS white matter tracts would either retract to a sustaining collateral (Ramon y Cajal, 1928) or die. However, modern labeling techniques have demonstrated that following the initial phase of retraction, axotomized neurons often survive (Houle, 1991; Kwon et al., 2002; Nielson et al., 2010) and the cut axon tips can remain within the penumbra of the lesion for years (Lu et al., 2007). What maintains the dystrophic tip of the axon chronically within the hostile environment of the glial scar? Are the mechanisms involved with long-term maintenance of the severed axon critical to regeneration failure? Here, we report that dystrophic axons form synaptic-like connections with NG2+ cells after SCI and our studies, both in vitro and in vivo, suggest that the NG2 proteoglycan (and other proteoglycans on the NG2+ cell surface) play a critical role in this entrapment phenomenon.

The idea that synaptic-like connections form between regenerating axons and reactive glia, and may curtail axonal regrowth after injury, had been suggested years ago, but had largely been abandoned. After a dorsal root crush, even following a peripheral conditioning lesion, injured sensory axons can regenerate rapidly within the proximal root until they reach the dorsal root entry zone (DREZ), a transitional region between the PNS and the CNS where the axons abruptly halt their forward progress and remain (Carlstedt, 1985; Liuzzi and Lasek, 1987; Di Maio et al., 2011). Early studies suggested that as peripheral axons regenerate toward the CNS they contact reactive astrocytes, which signal for the growth cone to limit extension of filopodia and initiate the early stages of synaptic-like formations in close association with the astrocyte surface. Our data show that dystrophic axons after DCC are actually stabilizing on the NG2+ cell, rather than astrocytes, and this relationship is also likely to occur at the DREZ. It was previously thought that NG2 expression repelled regeneration, causing injured neurons to cease regrowth as they approached cells that express this purportedly inhibitory CSPG. In fact, our data confirm that NG2 does prevent regeneration beyond the NG2+ cell boundary, but this occurs because the axons prefer the NG2+ cell surface. We propose that this strong association at the caudal end of the lesion is another major contributor to regeneration failure.

The underlying molecular machinery is unknown, but entrapment is likely to be receptor-mediated. Our study demonstrates that crucial ratios of both growth-permissive ECM molecules and proteoglycans are necessary for entrapment to occur. Integrins are a family of receptors for laminin and fibronectin (Tomaselli et al., 1993) and recent studies have identified members of the leukocyte antigen-related (LAR) subfamily as receptors for CSPGs (Shen et al., 2009; Fisher et al., 2011). Condic et al. (1999) demonstrated that neurons grown on laminin in the presence of low concentrations of aggrecan adapted by increasing both the levels of integrin RNA and surface protein for integrins α6β1 and α3β1 (Condic et al., 1999). The presence of the NG2 proteoglycan also seems to trigger increasing levels of integrin expression in adult DRG neurons. Several studies from the Stallcup lab have shown that NG2 does activate integrins, specifically α3β1, and downstream signaling in the context of angiogenesis and tumor resistance, supporting the hypothesis that NG2 may activate integrin pathways in mediating growth upon the NG2+ cell surface and entrapment (Fukushi et al., 2004; Makagiansar et al., 2007; Chekenya et al., 2008). In the current study it is notable that there was no significant change in integrin expression at 1 DIV, demonstrating that the change in expression takes time. This may help explain why neurons are able to extend neurites off the NG2+ cell surface when ch'ase treated for 24 h, but not at later time points, when integrin expression has increased. Previous characterizations of growth cones as they progress from one permissive substrate to another found that axons often pause or turn as they approach a new substrate (Burden-Gulley et al., 1995; Challacombe et al., 1996, 1997). Here, under certain conditions, we observed neurites extending within or across a variety of substrates that contained low levels of CSPGs. However, we have not yet examined the close details of growth cone dynamics as they enter or exit the stripes or NG2+ cell surface, but it is likely that growth cones display a variety of intriguing behaviors at these interfaces. In vitro, DRG neurons exhibited different growth patterns depending upon which substrate the neuron cell body resided, as was described by Grimpe et al. (2005). Kuffler et al. (2009) observed a similar phenomenon, referred to as substrate specification, in which neurons in soma contact with Schwann cells expressing low levels of CSPGs did not extend neurites off the Schwann cell membrane onto the laminin background. Eliminating the CSPG removed the substrate specification, suggesting that neurons express different receptors based on which substrate molecules they encounter first. We hypothesize that neurons beginning on a growth-permissive substrate, such as laminin or fibronectin, express sufficiently high levels of integrin to enable them to detect these growth-promoting molecules when they grow onto low-abundance CSPG-containing lanes or the NG2+ cell surface. Upregulation of LAR family receptors (see below) may also take time, so short encounters with low-level CSPG are likely not enough to cause entrapment and encounters at sharp edges of high concentrations of CSPG cause turning. However, if the neurite grows within a CSPG-containing substrate for extended periods, it will eventually increase LAR receptors and become constrained and no longer leave for an alternate growth-permissive substrate (Fig. 4c). Conversely, neurons beginning on the NG2+ cell surface are exposed to low levels of CSPG and adhesion molecules from the outset, causing them to express high levels of both integrins and LAR family receptors, resulting in tight adhesions.

The two receptors for CSPGs, protein tyrosine phosphatase σ (PTPσ) and LAR phosphatase (Shen et al., 2009; Fisher et al., 2011), bind ligands that lie within the GAG chains. In addition to the activation of these receptors possibly playing a role in altering integrin RNA levels (Condic et al., 1999), PTPσ has been implicated directly in synapse formation (Um and Ko, 2013). Ch'ase treatment early on not only reduces entrapment on the NG2+ cell surface, but also reduces the number of SV2+ puncta found along the DRG neurites, suggesting that GAG chains of CSPGs play a critical role at least in the initiation of synapse-like formations between the neuron and NG2+ cell. We suggest that once integrins and/or LAR or PTPσ aid in the initial constraint on the NG2+ cell, continuing increases in signaling through LAR family receptors may cause neurite outgrowth to slow to the point of allowing synaptic-like formation upon a non-neuronal cell type. However, we do not yet know precisely how integrin and LAR family receptors interact, nor do we understand the regulatory machinery downstream of receptor activation that leads to the creation of a state of long-term entrapment.

Synapse formation between NG2+ cells and neurons has been reported in several areas of the CNS under normal conditions (Bergles et al., 2000; Gallo et al., 2008). The exact role of these synapses remains unclear and there is debate over whether these are classical synapses, since there may be some ultrastructural differences. Synaptic contacts in gray matter between neurons and NG2+ cells have a presynaptic bouton containing an array of vesicles, with electron dense material both presynaptically and postsynaptically, in addition to well aligned membranes (Bergles et al., 2000; Gallo et al., 2008). In the white matter, synaptic specializations are less apparent. There are fewer synaptic vesicles and less electron dense material (Kukley et al., 2007). Functionally, the synaptic currents in NG2+ cells are similar to those in neurons. In this study, we observed synaptic-like connections between NG2+ cells caudal to the lesion and injured axons after dieback. These synaptic-like connections are found in the white matter, where there are no dendrites or normal targets for the injured axons. Even when NG2 expression declines, axons persist on the cells that once expressed this CSPG, suggesting that NG2 (or other CSPGs on the NG2+ cell surface) is necessary for initial stabilization and synapse-like formation, but is not necessary to maintain this connection. Our study with the NG2 KO mice further suggests that NG2 is necessary to help stabilize retracting fibers after injury. Without NG2, the axons retract further from the lesion core supporting observations by de Castro et al. (2005). However, the fibers do not continue to dieback at 28 d, suggesting that NG2 may be necessary for faster stabilization, but without it, other CSPGs on the NG2+ cell surface or reactive astrocytes may compensate and stabilize axons over time. The ultimate fate of the dystrophic axon tips in normal as well as NG2 KO animals over many months or years remains to be determined.

After conditioning, a subset of sensory axons are able to navigate through and even beyond the lesion core where they once again become stalled. It is possible that their regeneration may be slowed because they downregulate growth-associated proteins or growth-regulatory pathways (Sun et al., 2011; Lewandowski and Steward, 2014) as they continue to associate with NG2+ glia and reactive astrocytes that tile the white matter distal to the lesion. Unfortunately, the strong bond that evolves between regenerating axons and NG2 cells in the lesion core may prove difficult to break. Finding methods to dismantle this synaptic-like connection, especially at chronic time points following cord injury, without the need to surgically re-sever the axon will be a major effort in the future.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health–National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Grant NS025713 (J.S.), National Institutes of Health Training Grant T32 (A.F.), and the New York State Department of Health and the Brumagin Memorial Fund. We extend our thanks to Hongmei Hu and JingQiang You for technical assistance, as well as Maryanne Pendergast for assistance with imaging. We would also like to thank Steven Nord for his assistance with statistics.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Asher RA, Morgenstern DA, Shearer MC, Adcock KH, Pesheva P, Fawcett JW. Versican is upregulated in CNS injury and is a product of oligodendrocyte lineage cells. J Neurosci. 2002;22:2225–2236. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-06-02225.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai L, Hecker J, Kerstetter A, Miller RH. Myelin repair and functional recovery mediated by neural cell transplantation in a mouse model of multiple sclerosis. Neurosci Bull. 2013;29:239–250. doi: 10.1007/s12264-013-1312-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergles DE, Roberts JD, Somogyi P, Jahr CE. Glutamatergic synapses on oligodendrocyte precursor cells in the hippocampus. Nature. 2000;405:187–191. doi: 10.1038/35012083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury EJ, Moon LD, Popat RJ, King VR, Bennett GS, Patel PN, Fawcett JW, McMahon SB. Chondroitinase ABC promotes functional recovery after spinal cord injury. Nature. 2002;416:636–640. doi: 10.1038/416636a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burden-Gulley SM, Payne HR, Lemmon V. Growth cones are actively influenced by substrate-bound adhesion molecules. J Neurosci. 1995;15:4370–4381. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-06-04370.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busch SA, Horn KP, Cuascut FX, Hawthorne AL, Bai L, Miller RH, Silver J. Adult NG2+ cells are permissive to neurite outgrowth and stabilize sensory axons during macrophage-induced axonal dieback after spinal cord injury. J Neurosci. 2010;30:255–265. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3705-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlstedt T. Regenerating axons form nerve terminals at astrocytes. Brain Res. 1985;347:188–191. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)90911-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Challacombe JF, Snow DM, Letourneau PC. Actin filament bundles are required for microtubule reorientation during growth cone turning to avoid an inhibitory guidance cue. J Cell Sci. 1996;109:2031–2040. doi: 10.1242/jcs.109.8.2031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Challacombe JF, Snow DM, Letourneau PC. Dynamic microtubule ends are required for growth cone turning to avoid an inhibitory guidance cue. J Neurosci. 1997;17:3085–3095. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-09-03085.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chekenya M, Krakstad C, Svendsen A, Netland IA, Staalesen V, Tysnes BB, Selheim F, Wang J, Sakariassen PØ, Sandal T, Lønning PE, Flatmark T, Enger PØ, Bjerkvig R, Sioud M, Stallcup WB. The progenitor cell marker NG2/MPG promotes chemoresistance by activation of integrin-dependent PI3K/Akt signaling. Oncogene. 2008;27:5182–5194. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Condic ML, Snow DM, Letourneau PC. Embryonic neurons adapt to the inhibitory proteoglycan aggrecan by increasing integrin expression. J Neurosci. 1999;19:10036–10043. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-22-10036.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Castro R, Jr, Tajrishi R, Claros J, Stallcup WB. Differential responses of spinal axons to transection: influence of the NG2 proteoglycan. Exp Neurol. 2005;192:299–309. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2004.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Maio A, Skuba A, Himes BT, Bhagat SL, Hyun JK, Tessler A, Bishop D, Son YJ. In vivo imaging of dorsal root regeneration: rapid immobilization and presynaptic differentiation at the CNS/PNS border. J Neurosci. 2011;31:4569–4582. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4638-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dou CL, Levine JM. Inhibition of neurite growth by the NG2 chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan. J Neurosci. 1994;14:7616–7628. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-12-07616.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fidler PS, Schuette K, Asher RA, Dobbertin A, Thornton SR, Calle-Patino Y, Muir E, Levine JM, Geller HM, Rogers JH, Faissner A, Fawcett JW. Comparing astrocytic cell lines that are inhibitory or permissive for axon growth: the major axon-inhibitory proteoglycan is NG2. J Neurosci. 1999;19:8778–8788. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-20-08778.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher D, Xing B, Dill J, Li H, Hoang HH, Zhao Z, Yang XL, Bachoo R, Cannon S, Longo FM, Sheng M, Silver J, Li S. Leukocyte common antigen-related phosphatase is a functional receptor for chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan axon growth inhibitors. J Neurosci. 2011;31:14051–14066. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1737-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitch MT, Silver J. Glial cell extracellular matrix: boundaries for axon growth in development and regeneration. Cell Tissue Res. 1997;290:379–384. doi: 10.1007/s004410050944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisén J, Haegerstrand A, Risling M, Fried K, Johansson CB, Hammarberg H, Elde R, Hökfelt T, Cullheim S. Spinal axons in central nervous system scar tissue are closely related to laminin-immunoreactive astrocytes. Neuroscience. 1995;65:293–304. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)00467-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukushi J, Makagiansar IT, Stallcup WB. NG2 proteoglycan promotes endothelial cell motility and angiogenesis via engagement of galectin-3 and alpha3beta1 integrin. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:3580–3590. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-03-0236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo V, Mangin JM, Kukley M, Dietrich D. Synapses on NG2-expressing progenitors in the brain: multiple functions? J Physiol. 2008;586:3767–3781. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.158436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Göritz C, Dias DO, Tomilin N, Barbacid M, Shupliakov O, Frisén J. A pericyte origin of spinal cord scar tissue. Science. 2011;333:238–242. doi: 10.1126/science.1203165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimpe B, Pressman Y, Lupa MD, Horn KP, Bunge MB, Silver J. The role of proteoglycans in Schwann cell/astrocyte interactions and in regeneration failure at PNS/CNS interfaces. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2005;28:18–29. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2004.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanaichi T, Sato T, Iwamoto T, Malavasi-Yamashiro J, Hoshino M, Mizuno N. A stable lead by modification of Sato's method. J Electron Microsc. 1986;35:304–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn KP, Busch SA, Hawthorne AL, van Rooijen N, Silver J. Another barrier to regeneration in the CNS: activated macrophages induce extensive retraction of dystrophic axons through direct physical interactions. J Neurosci. 2008;28:9330–9341. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2488-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houle JD. Demonstration of the potential for chronically injured neurons to regenerate axons into intraspinal peripheral nerve grafts. Exp Neurol. 1991;113:1–9. doi: 10.1016/0014-4886(91)90139-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ippolito DM, Eroglu C. Quantifying synapses: an immunocytochemistry-based assay to quantify synapse number. J Vis Exp. 2010;45:2270. doi: 10.3791/2270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones LL, Yamaguchi Y, Stallcup WB, Tuszynski MH. NG2 is a major chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan produced after spinal cord injury and is expressed by macrophages and oligodendrocyte progenitors. J Neurosci. 2002;22:2792–2803. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-07-02792.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones LL, Sajed D, Tuszynski MH. Axonal regeneration through regions of chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan deposition after spinal cord injury: a balance of permissiveness and inhibition. J Neurosci. 2003;23:9276–9288. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-28-09276.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karnovsky MJ. Use of ferrocyanide-reduced osmium tetroxide in electron microscopy. Proceedings of the 11th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Cell Biology; New Orleans. 1971. p. 146. [Google Scholar]

- Kiani C, Chen L, Wu YJ, Yee AJ, Yang BB. Structure and function of aggrecan. Cell Res. 2002;12:19–32. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knöll B, Weinl C, Nordheim A, Bonhoeffer F. Stripe assay to examine axonal guidance and cell migration. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:1216–1224. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuffler DP1, Sosa IJ, Reyes O. Schwann cell chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan inhibits dorsal root ganglion neuron neurite outgrowth and substrate specificity via a soma and not a growth cone mechanism. J Neurosci Res. 2009;87:28663–28671. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kukley M, Capetillo-Zarate E, Dietrich D. Vesicular glutamate release from axons in white matter. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:311–320. doi: 10.1038/nn1850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon BK, Liu J, Messerer C, Kobayashi NR, McGraw J, Oschipok L, Tetzlaff W. Survival and regeneration of rubrospinal neurons 1 year after spinal cord injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:3246–3251. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052308899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]