Summary

The human microbiome contains diverse microorganisms, which share and compete for the same environmental niches [1, 2]. A major microbial growth form in the human body is the biofilm state, where tightly packed bacterial, archaeal and fungal cells must cooperate and/or compete for resources in order to survive [3–6]. We examined mixed biofilms composed of the major fungal species of the gut microbiome, C. albicans, and each of five prevalent bacterial gastrointestinal inhabitants: Bacteroides fragilis, Clostridium perfringens, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae and Enterococcus faecalis [7–10]. We observed that biofilms formed by C. albicans provide a hypoxic microenvironment that supports the growth of two anaerobic bacteria, even when cultured in ambient oxic conditions that are normally toxic to the bacteria. We also found that co-culture with bacteria in biofilms induces massive gene expression changes in C. albicans, including upregulation of WOR1, which encodes a transcription regulator that controls a phenotypic switch in C. albicans, from the “white” cell type to the “opaque” cell type. Finally, we observed that in suspension cultures, C. perfringens induces aggregation of C. albicans into “mini-biofilms,” which allow C. perfringens cells to survive in a normally toxic environment. This work indicates that bacteria and C. albicans interactions modulate the local chemistry of their environment in multiple ways to create niches favorable to their growth and survival.

Results

The fungal species C. albicans forms mixed biofilms with five bacterial species

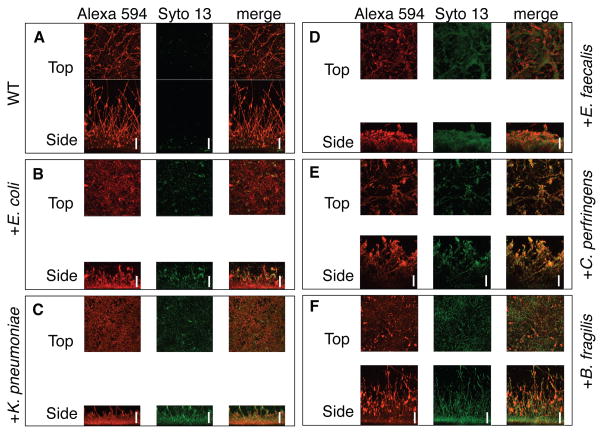

C. albicans with or without C. perfringens, B. fragilis, E. faecalis, E. coli or K. pneumoniae cells were adhered to a bovine serum coated, polystyrene well for 90 minutes and allowed to develop into biofilms for 24 hours, a standard procedure for producing C. albicans biofilms [11, 12]. Confocal scanning laser microscopy (CSLM) images confirmed that in all cases, both fungal and bacterial species incorporated into the biofilm (Figure 1). The bacteria adhered to both C. albicans hyphal and yeast-form cells (Figure 1; Figure S1A – F). While B. fragilis, and C. perfringens had minimal effect on the biofilm architecture, incorporation of E. coli, E. faecalis and K. pneumoniae reduced the overall biofilm thickness (Figure S1G). We designed a colony forming unit (CFU) assay as a readout for live bacterial and C. albicans cells present, and found that both bacteria and C. albicans were incorporated into the biofilms over time (Figure 2A – D, S2A – C).

Figure 1. C. albicans forms biofilms with five different species of bacteria in vitro.

C. albicans was grown in biofilms for 24 h either alone (A), or with E. coli (B), K. pneumoniae (C), E. faecalis (D), C. perfringens (E), or B. fragilis (F). Biofilms were stained with conconavalin A – Alexa 594 and Syto 13 dyes, then imaged by CSLM. Images are maximum intensity projections of the top and side view. Representative images of at least three replicates are shown. Scale bars are 50 μm. See also Figure S1.

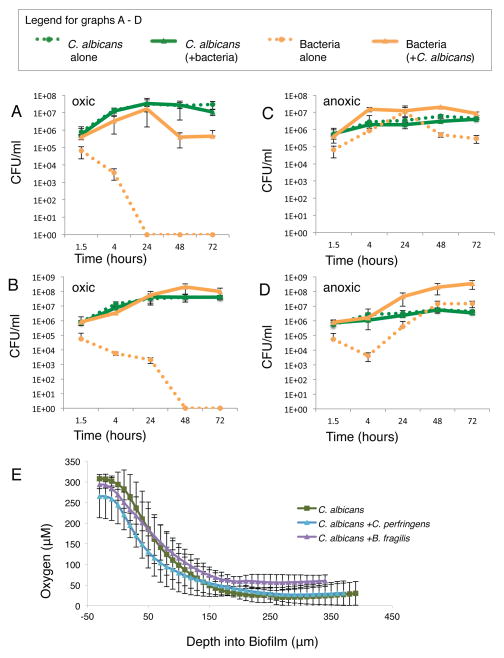

Figure 2. Mixed-species biofilms provide a niche for growth of anaerobic bacteria.

(A–D) CFU/ml of indicated species grown in biofilms in monoculture or co-culture under oxic or anoxic conditions. Cells were collected from biofilms only (not from the media above the biofilm) at 1.5, 4, 24, 48, and 72 h, and plated for CFUs. A) C. albicans and/or C. perfringens in oxic conditions. B) C. albicans and/or B. fragilis in oxic conditions. C) C. albicans and/or C. perfringens in anoxic conditions. D) C. albicans and/or B. fragilis in anoxic conditions. E) Oxygen was measured in biofilms composed of the indicated species using a STOX-Sensor. Readings were taken every 10 μm from the top to the bottom of the biofilm. For all graphs, the mean of at least two replicates is shown, with error bars representing standard deviation. See also Figure S2.

C. perfringens and B. fragilis proliferate in co-cultured biofilms with C. albicans under ambient oxic conditions

C. albicans and/or C. perfringens or B. fragilis cells were co-cultured in biofilms for 4, 24, 48, or 72 h, under ambient oxic or anoxic conditions. Growth of each species over time was measured by plating for CFUs (Figure 2A – D). The adherence and growth of C. albicans was unaffected by the presence or absence of bacterial cells; however the initial adherence of C. perfringens and B. fragilis increased ten-fold in the presence of C. albicans. In mixed biofilms, after adherence, C. perfringens showed substantial growth, from ~5×105 CFU/ml to ~1×107 CFU/ml in 24 h, regardless of whether the biofilm was grown under ambient oxic or anoxic conditions (Figure 2A, C). Without C. albicans, viable C. perfringens cells decreased below detection (<10 CFU/ml) after 24 h in ambient oxic conditions (Figure 2A). B. fragilis showed the same trend (Figure 2B, D). In addition to the standard laboratory strain of C. albicans (SC5314), we tested two other clinical isolates of C. albicans and found they are also able to support anaerobe growth (Figure S2D, E). Our data demonstrate that incorporation into a C. albicans biofilm grown under ambient oxic conditions enables growth of the anaerobes C. perfringens and B. fragilis; without the protective biofilm, the viability of both bacterial species rapidly declines.

C. albicans biofilms create a hypoxic microenvironment

To test the hypothesis that biofilms create locally hypoxic environments which enable the growth of anaerobic bacteria, we measured oxygen levels in biofilms using a miniaturized, Switch-able Trace Oxygen Sensor (STOX-Sensor), an instrument capable of measuring oxygen concentrations as low as 10 nM [13]. Measurements with the STOX-Sensor revealed a gradient of oxygen concentration throughout the depth of the biofilm, decreasing from ~300 μM (ambient oxygen) near the top of the biofilm to less than 50 μM near the bottom (Figure 2E). The oxygen gradient remained the same whether C. albicans was grown in monoculture or was co-cultured with C. perfringens or B. fragilis.

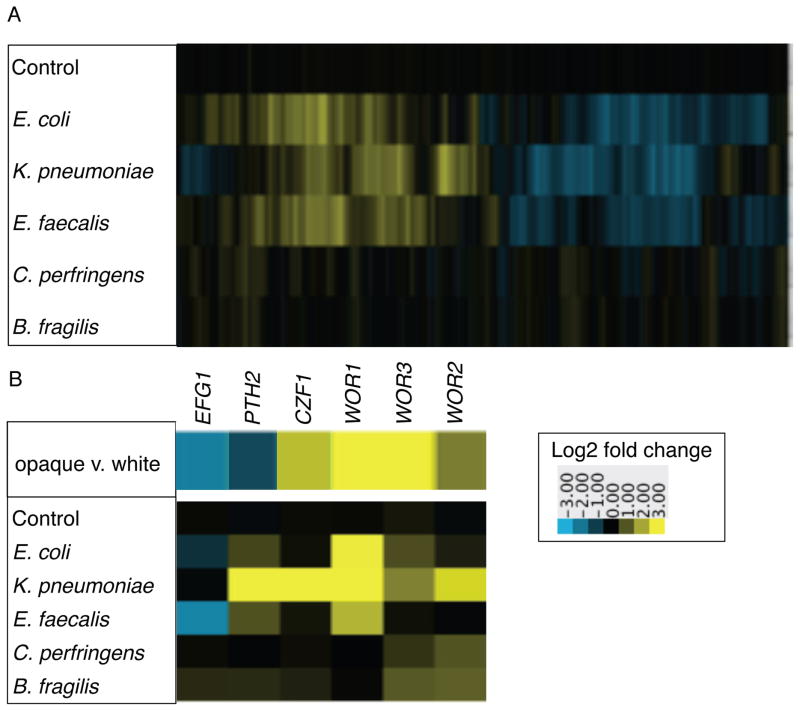

Co-culture in biofilms with bacteria alters gene expression in C. albicans

To determine whether C. albicans was responding to bacteria in the mixed-species biofilm, we measured gene expression changes in C. albicans by microarray (Figure 3A; Dataset 1). Relative to the C. albicans biofilm formed in the absence of bacteria, many genes were up- and down-regulated in the presence of bacteria. Some genes changed expression in response to all of the bacterial species, while others were specific to a few species.

Figure 3. Co-culture with bacteria in biofilms induces differential gene expression in C. albicans.

A) Heat map of gene expression in C. albicans when co-cultured with the indicated species in biofilms, compared to C. albicans alone. Shown are the median values of at least two biological replicates. Control refers to C. albicans with media added to mimic the inoculum with bacteria, compared to C. albicans alone. 2863 genes differentially regulated at least twofold in at least one condition are displayed along the x-axis. Upregulated genes are yellow, downregulated genes are blue. B) Gene expression pattern of genes encoding transcription regulators that control the white-opaque switch circuit. The top panel shows expression levels measured in opaque vs. white cells from [19]. The bottom panel shows expression levels when C. albicans is co-cultured in biofilms with the indicated bacterial species, compared to C. albicans alone. See also Figure S3.

Among the most differentially regulated genes were those encoding the transcription regulators controlling the white-opaque switch in C. albicans, a transition between two cell types, each of which is heritable for many generations [14–17] (Figure 3B). In particular, WOR1, which encodes the “master” regulator of white-opaque switching, was strongly upregulated by co-culture with K. pneumoniae, E. coli, and E. faecalis. Co-culture with K. pneumoniae also induced upregulation of several other transcription regulators known to play roles in the white-opaque switch, in a WOR1-independent manner (Figure S3, Dataset 2) [16, 18–21].

Although a number of opaque-specific genes were upregulated, the full opaque-specific gene expression pattern was not observed, and when removed from this condition, the C. albicans cells revert to “classical” white cells. We propose that co-culture with bacterial cells poises C. albicans to switch from white to opaque, but that additional signals are required for full switching.

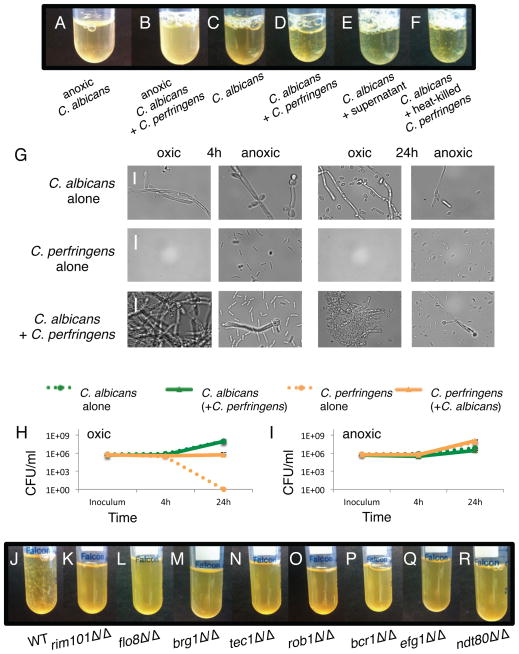

C. perfringens is protected by and induces aggregation of C. albicans in suspension culture

To further explore interactions between C. albicans and the bacterial microbiome members, we co-cultured them in suspension cultures, and observed that some of the bacteria induced co-aggregation with C. albicans cells (Table S1, Figure 4A – D). The most dramatic effect occurred with C. perfringens in ambient oxic conditions. Light microscopy revealed that the aggregates induced by C. perfringens were composed of dense clumps containing both C. albicans and C. perfringens cells and resembling miniature biofilms (Figure 4G). By monitoring CFUs/ml of C. perfringens grown in suspension cultures over time (Figure 4H, I), we observed that the presence of C. albicans enabled survival of C. perfringens in oxic suspension conditions to levels of ~1×106 CFU/ml; in the absence of C. albicans, C. perfringens CFUs dropped at least five orders of magnitude, to undetectable levels (<10 CFU/ml) by 24 h (Figure 4H).

Figure 4. C. perfringens induces aggregation of C. albicans during ambient oxic, suspension co-culture.

Suspension cultures of C. albicans with or without C. perfringens, grown for 4 h or 24 h at 37°C, in anoxic or ambient oxic conditions. A–F) 4 h growth. A) C. albicans alone, anoxic. B) C. albicans + C. perfringens, anoxic. C) C. albicans alone, oxic. D) C. albicans + C. perfringens, oxic. E) C. albicans + cell-free supernatant from C. perfringens culture. F) C. albicans + heat-killed C. perfringens cells. G) C. albicans and/or C. perfringens imaged by light microscopy. Representative images are shown. Scale bars are 20 μm. H–I) CFU/ml of indicated species grown in monoculture or co-culture, in suspension cultures under ambient oxic or anoxic conditions. H) C. albicans and/or C. perfringens in ambient oxic conditions. I) C. albicans and/or C. perfringens in anoxic conditions. Shown is the mean of at least two replicates, error bars are standard deviation. J–R) C. albicans wild type or mutant strains grown in suspension, in ambient oxygen, for 4 h with C. perfringens. J) WT. K) rim101Δ/Δ. L) flo8Δ/Δ. M) brg1Δ/Δ. N) tec1Δ/Δ. O) rob1Δ/Δ. P) bcr1Δ/Δ. Q) efg1Δ/Δ. R) ndt80Δ/Δ. Assay was performed at least twice for each condition or mutant strain. See also Figure S4.

Although the mini-biofilms are too small to directly probe for oxygen concentration, we note that C. albicans gene expression under these conditions was significantly enriched for genes regulated during hypoxic conditions (P = 1.4×10−5) [22] (Figure S4A, Dataset 3), suggesting that the mini-biofilms, like conventional, surface-adhered biofilms, provide a hypoxic environment. Consistent with this idea, we found that C. perfringens cells also stimulate aggregation in early stages of conventional C. albicans biofilm formation on a solid surface (Figure S4B).

We repeated the suspension growth experiment with cell-free supernatant or heat-killed C. perfringens cells, and observed that both are able to induce aggregation of C. albicans (Figure 4E, F). We blindly screened a library of 205 deletion strains in C. albicans [23] (Table S2), and identified eight transcription regulator-encoding genes and two other genes that are required for the observed interspecies aggregation (Figure 4K–R; Figure S4C). Notably, six of the transcription regulators (Brg1, Tec1, Rob1, Bcr1, Ndt80, and Efg1) found in our screen were previously identified “master regulators” of conventional biofilm formation [12], providing strong evidence that C. perfringens induces aggregate formation via the biofilm genetic program. The other two regulator mutants deficient in aggregation were rim101Δ/Δ and flo8Δ/Δ, which have not been reported to be required for conventional biofilm formation. DEF1, which regulates hyphal extension [24], and ALS3, which encodes an adhesin important for biofilm formation and plays a role in interacting with many bacterial species [25–29], were also required for aggregation (Figure S4C). As described in supplemental materials, we quantified aggregation using a sedimentation assay and verified that the deletion strains were complemented by gene “add-backs” (Figure S4D, E).

These results support a model whereby in ambient oxic suspension culture, C. perfringens induces C. albicans to form protective aggregates, which depend on the C. albicans biofilm genetic program. These mini-biofilms, which contain both C. albicans and C. perfringens, allow C. perfringens to survive in oxic conditions that are normally toxic.

Discussion

In this work we uncovered multiple interactions between C. albicans, a major fungal species of the human microbiome, and several bacterial members of the microbiome.

C. albicans biofilms: a microenvironment supporting anaerobic bacterial growth

It has been known for some time that bacterial biofilms are able to generate hypoxic microenvironments, supporting the growth of anaerobic bacterial species [30, 31], and it has been speculated that biofilms formed by Candida species may also be hypoxic, based on gene expression data and mutant phenotypes [30, 32–34]. Our work directly demonstrates, for the first time, that C. albicans biofilms create a hypoxic internal microenvironment when grown under ambient oxygen conditions. We also show that the microenvironment within the C. albicans biofilm is sufficient to support the growth of two different anaerobic species, C. perfringens and B. fragilis, and it is likely that decreased oxygen concentration plays a major role in anaerobe survival. Different strains of C. perfringens and B. fragilis have been reported to grow in oxygen levels as high as 3–5% (~40–70 μM) [35, 36], and we have shown that C. albicans biofilms provide an environment where the oxygen concentration is as low as ~50 μM. This finding suggests that C. albicans may permit the growth of anaerobes in oxic areas of the host that would otherwise be uninhabitable by those species. This idea may be especially important for the establishment of C. perfringens infection, which causes a wide variety of illnesses, including enterotoxemia, gas gangrene, and wound infections, many of which are life-threatening [37, 38].

The fact that oxygen concentration decreases steadily from the top to the bottom of a C. albicans biofilm adds to our understanding of the heterogeneous nature of biofilms. C. albicans biofilms are composed of multiple cell types (yeast, pseudohyphae, hyphae, persister/dormant cells and dispersing cells) that express different genetic programs [39–43] due to their precise location within the biofilm. The oxygen concentration gradient is one critical variable that structures the biofilm microenvironment and suggests that metabolism and gene expression vary between cells at different levels throughout the biofilm.

Partial induction of the white/opaque switch program in C. albicans

We monitored the transcriptional response of C. albicans to bacterial species in mixed biofilms, and found there was significant overlap between the genes upregulated by co-culture with K. pneumoniae and genes enriched in opaque cells compared to white cells (p = 8.4×10−20). There is also significant overlap between genes upregulated by co-culture with K. pneumoniae and genes enriched in a strain overexpressing WOR1 after passage through the mouse gut, compared to a wild type strain (p = 3.4×10−9) [44]. We propose that induction of WOR1 by bacteria may prime C. albicans for white-opaque switching, but that additional environmental cues are needed to fully induce the switch to the opaque form. An alternative hypothesis is that partial induction of the opaque program is an adaptive response to exposure to bacteria.

Aggregation induction by co-culture in suspension

We found that C. perfringens induces aggregation of C. albicans in ambient oxic suspension cultures and that the aggregates, which contain both fungi and bacteria, allow C. perfringens to survive in a normally toxic environment. Induction of aggregation may be similar to induction of biofilm formation, as aggregation requires the same master regulators needed for C. albicans to form a “conventional” biofilm on a solid surface. Moreover, the cells in the aggregates resemble cells in biofilms on solid surfaces. These observations indicate that the biofilm “program” in C. albicans does not require a solid surface to become activated, and the definition of a C. albicans biofilm may be expanded from a substrate-attached community to include suspended aggregates. E. coli, Pediococcus damnosus, and several other bacterial species were previously found to induce aggregation when co-cultured with several yeast species, including Candida utilis, S. cerevisiae, and Schizosaccharomyces pombe [45]. The evidence suggests that many microbial species are able to co-aggregate, and our work has demonstrated that adherence between fungi and bacteria can allow the survival of the bacteria.

Interspecies Interactions

We have shown that C. albicans interacts in a variety of ways with several representative species of the gut microbiome. These microbes are clearly able to sense one another; for example C. albicans responds through large changes in adherence and gene expression. We have provided new evidence of antagonistic (reduction of C. albicans biofilm thickness by the presence of K. pneumoniae) and beneficial (protection of C. perfringens by C. albicans biofilms) relationships, and have begun to uncover the genes involved in these interactions. These findings highlight the importance of considering the microenvironments encountered by microbiome members. The strategy of studying pairwise interactions between fungi and bacteria in the context of heterogeneous microenvironments can be expanded to better understand the complex community of thousands of species that encounter one another in the host.

Experimental Procedures

Co-cultures in suspension or biofilms

C. albicans and/or bacteria were grown in suspension or in biofilms adhered in 6-well polystyrene plates, in Brain Heart Infusion (BHI) medium, supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (BHI-FBS). Additional details in Supplement.

Colony Forming Units (CFUs) Assay

CFUs were plated from serial dilutions of either biofilms or suspension cultures. Dilutions were plated on YPD agar, LB agar, or blood agar at 30°C or 37°C, depending on the species. Additional details in Supplement.

Oxygen measurement

Oxygen concentration in biofilms was measured with a Unisense STOX-Sensor microelectrode, with measurements obtained every 10 μm from top to bottom. Additional details in Supplement.

Gene expression microarrays

Cy3 or Cy5-labeled cDNA was hybridized to custom Agilent microarrays, analyzed in GenePix Pro, and normalized with LOWESS. Additional details in Supplement.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1, Related to Figure 1. Bacteria are incorporated throughout the biofilm. C. albicans was grown in biofilms for 24 hours either alone (A), or with E. coli (B), K. pneumoniae (C), E. faecalis (D), C. perfringens (E), or B. fragilis (F). Biofilms were stained with conconavalin A – Alexa 594 and Syto 13 dyes, then imaged by CSLM. Images shown are top view, maximum intensity projection z-stacks of 65 μm thick sections internal to the biofilm. Scale bars are 50 μm. G) Biofilm thickness of at least six technical and two biological replicates was measured using CSLM. Average values shown, error bars indicate standard deviation. *Significantly different from C. albicans alone, P < 0.001, by student’s paired t-test.

Figure S2, related to Figure 2. Incorporation of C. albicans and bacteria in biofilms is affected by co-culture. CFU/ml of indicated species grown in biofilms in monoculture or co-culture, in biofilms in ambient oxic conditions. A) C. albicans SN250 and/or E. coli. B) C. albicans SN250 and/or K. pneumoniae. C) C. albicans SN250 and/or E. faecalis. D) C. albicans P57055 and/or C. perfringens E) C. albicans CEC3494 and/or C. perfringens. Shown is the mean of at least two replicates, error bars are standard deviation.

Figure S3, Related to Figure 3. WOR1 is regulated independently from other opaque regulators during biofilm co-culture. A) Confocal Scanning Laser Microscopy of wild type (SN250) or wor1Δ/Δ deletion (TF176) strain co-cultured with or without K. pneumoniae (abbreviated Kp). Images shown are maximum intensity projections of the top and side view. Scale bars are 50 μm. B) Top two rows: heat map of gene expression in C. albicans (SN250) when co-cultured with K. pneumoniae in biofilms, compared to C. albicans alone. Values are the median values of at least two biological replicates. Bottom two rows: heat map of gene expression in opaque (AHY136) compared to white cells (AHY135); and genes whose promoters are bound by Wor1 (Hernday et al, 2013). 6111 genes are along the x-axis and are unlabeled. Yellow genes are upregulated or bound by Wor1, Blue genes are downregulated, gray genes are not bound by Wor1. C–D) Quantitative RT-PCR. Shown are the mean values of at least two biological replicates. Error bars are standard deviation. WT = SN250, Kp = K. pneumoniae. C) Expression of WOR1 in the indicated strains. D) Expression of WOR1, WOR2, CZF1, and PTH2 in the indicated strains.

Figure S4, Related to Figure 4. Characterization of C. perfringens-induced aggregates when co-cultured in ambient oxic cultures with C. albicans. A) Heat map of gene expression in C. albicans when co-cultured in suspension with C. perfringens, compared to C. albicans alone. Shown are genes differentially regulated more than two fold. Values are the median values of at least two biological replicates. Upregulated genes are yellow, downregulated genes are blue. *Genes that are regulated during hypoxia in C. albicans; these genes are significantly enriched in our dataset with a p <1.5×10−5 by the chi-squared test. B) C. albicans was grown with or without C. perfringens, in biofilms for 1 hour. Biofilms were stained with conconavalin A – Alexa 594 and Syto 13 dyes, then imaged by CSLM. Images shown are maximum intensity projections of the top view. Scale bars are 50 μm. At least two replicates were visualized, representative images are shown. C – E) Suspension cultures of the indicated C. albicans strains, with or without C. perfringens, grown for 4 hours at 37°C. Assay was performed at least twice for each condition or mutant strain. C) C. albicans wild type or indicated mutant strains. D) C. albicans complemented strains where a wild type copy of indicated gene is restored in the deletion strain background. E) Aggregation was measured using an adapted assay from S. cerevisiae, in which flocculation is associated with greater sedimentation of aggregates, as measured by optical density (OD600). Assay was performed at least twice, error bars are standard deviation. Cp = C. perfringens. *Significantly different from WT +Cp, P < 0.05. #Significantly different from WT alone, P < 0.05. **Significantly different between indicated deletion strain and complemented strain, P < 0.05. Student’s paired t-test was used to calculate significance.

Induction of C. albicans aggregation by bacteria during suspension co-culture in oxic or anoxic conditions

Screen of C. albicans deletion mutant strains for aggregation during oxic suspension co-culture with C. perfringens.

Strains.

Primers.

Highlights.

C. albicans biofilms are hypoxic and support anaerobic bacteria survival

Bacteria induce part of the C. albicans opaque genetic program in mixed biofilms

C. perfringens induces biofilm formation in C. albicans in suspension co-culture

Acknowledgments

We thank Matthew Lohse, Aaron Hernday, Chiraj Dalal, Oliver Homann and Jose Christian Perez for strains or plasmids used in this study, Sheena Singh Babak and Trevor Sorrells for comments on the manuscript, and Jorge Mendoza for technical assistance. We appreciate use of the UCSF Nikon Imaging Center. This study was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant R01AI083311 (A.D.J.) and by a UCSF Program for Breakthrough Biomedical Research award, funded partly by the Sandler Foundation. E.P.F. was supported by NIH fellowship T32AI060537, C.J.N. was supported by NIH grant K99AI100896, and D.K.N. was supported by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI) and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the NIH (R01HL117328). D.K.N. is an HHMI Investigator.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Savage DC. Microbial ecology of the gastrointestinal tract. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1977;31:107–33. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.31.100177.000543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eckburg PB, Bik EM, Bernstein CN, Purdom E, Dethlefsen L, Sargent M, Gill SR, Nelson KE, Relman Da. Diversity of the human intestinal microbial flora. Science. 2005;308:1635–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1110591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.López D, Vlamakis H, Kolter R. Biofilms. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2:a000398. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a000398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kolter R, Greenberg EP. Microbial sciences: the superficial life of microbes. Nature. 2006;441:300–2. doi: 10.1038/441300a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Donlan RM, Costerton JW. Biofilms: Survival Mechanisms of Clinically Relevant Microorganisms. 2002;15:167–193. doi: 10.1128/CMR.15.2.167-193.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wolcott R, Costerton JW, Raoult D, Cutler SJ. The polymicrobial nature of biofilm infection. 2012:1–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.04001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iliev ID, Funari Va, Taylor KD, Nguyen Q, Reyes CN, Strom SP, Brown J, Becker Ca, Fleshner PR, Dubinsky M, et al. Interactions between commensal fungi and the C-type lectin receptor Dectin-1 influence colitis. Science. 2012;336:1314–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1221789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moyes DL, Naglik JR. The mycobiome: influencing IBD severity. Cell Host Microbe. 2012;11:551–2. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ghannoum Ma, Jurevic RJ, Mukherjee PK, Cui F, Sikaroodi M, Naqvi A, Gillevet PM. Characterization of the oral fungal microbiome (mycobiome) in healthy individuals. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000713. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khatib R, Riederer KM, Ramanathan J, Baran J. Faecal fungal flora in healthy volunteers and inpatients. Mycoses. 2001;44:151–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-0507.2001.00639.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nobile CJ, Mitchell AP. Regulation of cell-surface genes and biofilm formation by the C. albicans transcription factor Bcr1p. Curr Biol. 2005;15:1150–5. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.05.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nobile CJ, Fox EP, Nett JE, Sorrells TR, Mitrovich QM, Hernday AD, Tuch BB, Andes DR, Johnson AD. A recently evolved transcriptional network controls biofilm development in Candida albicans. Cell. 2012;148:126–38. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Revsbech NP, Larsen LH, Gundersen J, Dalsgaard T, Ulloa O, Thamdrup B. Determination of ultra-low oxygen concentrations in oxygen minimum zones by the STOX sensor. Limnol Oceanogr Methods. 2009;7:371–381. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Slutsky B, Staebell M, Anderson J, Risen L, Pfaller M, Soll DR. “White-opaque transition”: a second high-frequency switching system in Candida albicans. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:189–97. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.1.189-197.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Srikantha T, Borneman AR, Daniels KJ, Pujol C, Wu W, Seringhaus MR, Gerstein M, Yi S, Snyder M, Soll DR. TOS9 regulates white-opaque switching in Candida albicans. Eukaryot Cell. 2006;5:1674–87. doi: 10.1128/EC.00252-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zordan RE, Galgoczy DJ, Johnson AD. Epigenetic properties of white-opaque switching in Candida albicans are based on a self-sustaining transcriptional feedback loop. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:12807–12. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605138103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rikkerink EH, Magee BB, Magee PT. Opaque-white phenotype transition: a programmed morphological transition in Candida albicans. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:895–9. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.2.895-899.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lohse MB, Johnson AD. Temporal anatomy of an epigenetic switch in cell programming: the white-opaque transition of C.albicans. Mol Microbiol. 2010;78:331–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07331.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hernday AD, Lohse MB, Fordyce PM, Nobile CJ, DeRisi JL, Johnson AD. Structure of the transcriptional network controlling white-opaque switching in Candida albicans. Mol Microbiol. 2013;90:22–35. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tuch BB, Mitrovich QM, Homann OR, Hernday AD, Monighetti CK, De La Vega FM, Johnson AD. The transcriptomes of two heritable cell types illuminate the circuit governing their differentiation. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1001070. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zordan RE, Miller MG, Galgoczy DJ, Tuch BB, Johnson AD. Interlocking transcriptional feedback loops control white-opaque switching in Candida albicans. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e256. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Synnott JM, Guida A, Mulhern-Haughey S, Higgins DG, Butler G. Regulation of the hypoxic response in Candida albicans. Eukaryot Cell. 2010;9:1734–46. doi: 10.1128/EC.00159-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Homann OR, Dea J, Noble SM, Johnson AD. A phenotypic profile of the Candida albicans regulatory network. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000783. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martin R, Moran GP, Jacobsen ID, Heyken A, Domey J, Sullivan DJ, Kurzai O, Hube B. The Candida albicans-specific gene EED1 encodes a key regulator of hyphal extension. PLoS One. 2011;6:e18394. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhao X, Daniels KJ, Oh S, Green CB, Yeater KM, Soll DR, Hoyer LL. Candida albicans Als3p is required for wild-type biofilm formation on silicone elastomer surfaces. Microbiology. 2006;152:2287–99. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28959-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu Y, Filler SG. Candida albicans Als3, a multifunctional adhesin and invasin. Eukaryot Cell. 2011;10:168–73. doi: 10.1128/EC.00279-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Silverman RJ, Nobbs AH, Vickerman MM, Barbour ME, Jenkinson HF. Interaction of Candida albicans cell wall Als3 protein with Streptococcus gordonii SspB adhesin promotes development of mixed-species communities. Infect Immun. 2010;78:4644–52. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00685-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peters BM, Ovchinnikova ES, Krom BP, Schlecht LM, Zhou H, Hoyer LL, Busscher HJ, van der Mei HC, Jabra-Rizk MA, Shirtliff ME. Staphylococcus aureus adherence to Candida albicans hyphae is mediated by the hyphal adhesin Als3p. Microbiology. 2012;158:2975–86. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.062109-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nobile CJ, Andes DR, Nett JE, Smith FJ, Yue F, Phan QT, Edwards JE, Filler SG, Mitchell AP. Critical role of Bcr1-dependent adhesins in C. albicans biofilm formation in vitro and in vivo. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2:e63. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bradshaw DJ, Marsh PD, Allison C, Schilling KM. Effect of oxygen, inoculum composition and flow rate on development of mixed-culture oral biofilms. Microbiology. 1996;142(Pt 3):623–9. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-3-623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bradshaw DJ, Marsh PD, Watson GK, Allison C. Role of Fusobacterium nucleatum and coaggregation in anaerobe survival in planktonic and biofilm oral microbial communities during aeration. Infect Immun. 1998;66:4729–32. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.10.4729-4732.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rossignol T, Ding C, Guida A, D’Enfert C, Higgins DG, Butler G. Correlation between biofilm formation and the hypoxic response in Candida parapsilosis. Eukaryot Cell. 2009;8:550–9. doi: 10.1128/EC.00350-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bonhomme J, Chauvel M, Goyard S, Roux P, Rossignol T, D’Enfert C. Contribution of the glycolytic flux and hypoxia adaptation to efficient biofilm formation by Candida albicans. Mol Microbiol. 2011;80:995–1013. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07626.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stichternoth C, Ernst JF. Hypoxic adaptation by Efg1 regulates biofilm formation by Candida albicans. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75:3663–72. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00098-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Loesche WJ. Oxygen sensitivity of various anaerobic bacteria. Appl Microbiol. 1969;18:723–7. doi: 10.1128/am.18.5.723-727.1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tally FP, Stewart PR, Sutter VL, Rosenblatt JE. Oxygen tolerance of fresh clinical anaerobic bacteria. J Clin Microbiol. 1975;1:161–4. doi: 10.1128/jcm.1.2.161-164.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li J, Adams V, Bannam TL, Miyamoto K, Garcia JP, Uzal Fa, Rood JI, McClane Ba. Toxin plasmids of Clostridium perfringens. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2013;77:208–33. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00062-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stevens DL, Aldape MJ, Bryant AE. Life-threatening clostridial infections. Anaerobe. 2012;18:254–9. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2011.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lewis K. Persister cells. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2010;64:357–72. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.112408.134306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yeater KM, Chandra J, Cheng G, Mukherjee PK, Zhao X, Rodriguez-Zas SL, Kwast KE, Ghannoum Ma, Hoyer LL. Temporal analysis of Candida albicans gene expression during biofilm development. Microbiology. 2007;153:2373–85. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2007/006163-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Uppuluri P, Chaturvedi AK, Srinivasan A, Banerjee M, Ramasubramaniam AK, Köhler JR, Kadosh D, Lopez-Ribot JL. Dispersion as an important step in the Candida albicans biofilm developmental cycle. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000828. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Baillie GS, Douglas LJ. Role of dimorphism in the development of Candida albicans biofilms. J Med Microbiol. 1999;48:671–9. doi: 10.1099/00222615-48-7-671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nett JE, Lepak AJ, Marchillo K, Andes DR. Time course global gene expression analysis of an in vivo Candida biofilm. J Infect Dis. 2009;200:307–13. doi: 10.1086/599838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pande K, Chen C, Noble SM. Passage through the mammalian gut triggers a phenotypic switch that promotes Candida albicans commensalism. Nat Genet. 2013:1–6. doi: 10.1038/ng.2710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Peng X, Sun J, Iserentant D, Michiels C, Verachtert H. Flocculation and coflocculation of bacteria by yeasts. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2001;55:777–81. doi: 10.1007/s002530000564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1, Related to Figure 1. Bacteria are incorporated throughout the biofilm. C. albicans was grown in biofilms for 24 hours either alone (A), or with E. coli (B), K. pneumoniae (C), E. faecalis (D), C. perfringens (E), or B. fragilis (F). Biofilms were stained with conconavalin A – Alexa 594 and Syto 13 dyes, then imaged by CSLM. Images shown are top view, maximum intensity projection z-stacks of 65 μm thick sections internal to the biofilm. Scale bars are 50 μm. G) Biofilm thickness of at least six technical and two biological replicates was measured using CSLM. Average values shown, error bars indicate standard deviation. *Significantly different from C. albicans alone, P < 0.001, by student’s paired t-test.

Figure S2, related to Figure 2. Incorporation of C. albicans and bacteria in biofilms is affected by co-culture. CFU/ml of indicated species grown in biofilms in monoculture or co-culture, in biofilms in ambient oxic conditions. A) C. albicans SN250 and/or E. coli. B) C. albicans SN250 and/or K. pneumoniae. C) C. albicans SN250 and/or E. faecalis. D) C. albicans P57055 and/or C. perfringens E) C. albicans CEC3494 and/or C. perfringens. Shown is the mean of at least two replicates, error bars are standard deviation.

Figure S3, Related to Figure 3. WOR1 is regulated independently from other opaque regulators during biofilm co-culture. A) Confocal Scanning Laser Microscopy of wild type (SN250) or wor1Δ/Δ deletion (TF176) strain co-cultured with or without K. pneumoniae (abbreviated Kp). Images shown are maximum intensity projections of the top and side view. Scale bars are 50 μm. B) Top two rows: heat map of gene expression in C. albicans (SN250) when co-cultured with K. pneumoniae in biofilms, compared to C. albicans alone. Values are the median values of at least two biological replicates. Bottom two rows: heat map of gene expression in opaque (AHY136) compared to white cells (AHY135); and genes whose promoters are bound by Wor1 (Hernday et al, 2013). 6111 genes are along the x-axis and are unlabeled. Yellow genes are upregulated or bound by Wor1, Blue genes are downregulated, gray genes are not bound by Wor1. C–D) Quantitative RT-PCR. Shown are the mean values of at least two biological replicates. Error bars are standard deviation. WT = SN250, Kp = K. pneumoniae. C) Expression of WOR1 in the indicated strains. D) Expression of WOR1, WOR2, CZF1, and PTH2 in the indicated strains.

Figure S4, Related to Figure 4. Characterization of C. perfringens-induced aggregates when co-cultured in ambient oxic cultures with C. albicans. A) Heat map of gene expression in C. albicans when co-cultured in suspension with C. perfringens, compared to C. albicans alone. Shown are genes differentially regulated more than two fold. Values are the median values of at least two biological replicates. Upregulated genes are yellow, downregulated genes are blue. *Genes that are regulated during hypoxia in C. albicans; these genes are significantly enriched in our dataset with a p <1.5×10−5 by the chi-squared test. B) C. albicans was grown with or without C. perfringens, in biofilms for 1 hour. Biofilms were stained with conconavalin A – Alexa 594 and Syto 13 dyes, then imaged by CSLM. Images shown are maximum intensity projections of the top view. Scale bars are 50 μm. At least two replicates were visualized, representative images are shown. C – E) Suspension cultures of the indicated C. albicans strains, with or without C. perfringens, grown for 4 hours at 37°C. Assay was performed at least twice for each condition or mutant strain. C) C. albicans wild type or indicated mutant strains. D) C. albicans complemented strains where a wild type copy of indicated gene is restored in the deletion strain background. E) Aggregation was measured using an adapted assay from S. cerevisiae, in which flocculation is associated with greater sedimentation of aggregates, as measured by optical density (OD600). Assay was performed at least twice, error bars are standard deviation. Cp = C. perfringens. *Significantly different from WT +Cp, P < 0.05. #Significantly different from WT alone, P < 0.05. **Significantly different between indicated deletion strain and complemented strain, P < 0.05. Student’s paired t-test was used to calculate significance.

Induction of C. albicans aggregation by bacteria during suspension co-culture in oxic or anoxic conditions

Screen of C. albicans deletion mutant strains for aggregation during oxic suspension co-culture with C. perfringens.

Strains.

Primers.