Abstract

Background

Surgical scars are crucial cosmetic problem, especially when in exposed areas such as the anterior neck following thyroidectomy.

Objective

To evaluate the impact of post-thyroidectomy scars on quality of life (QoL) of thyroid cancer patients and identify the relationship between scar characteristics and QoL.

Methods

Patients with post-thyroidectomy scars on the neck were recruited. QoL was measured using the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI). Scar characteristics were graded according to Vancouver scar scale (VSS) score.

Results

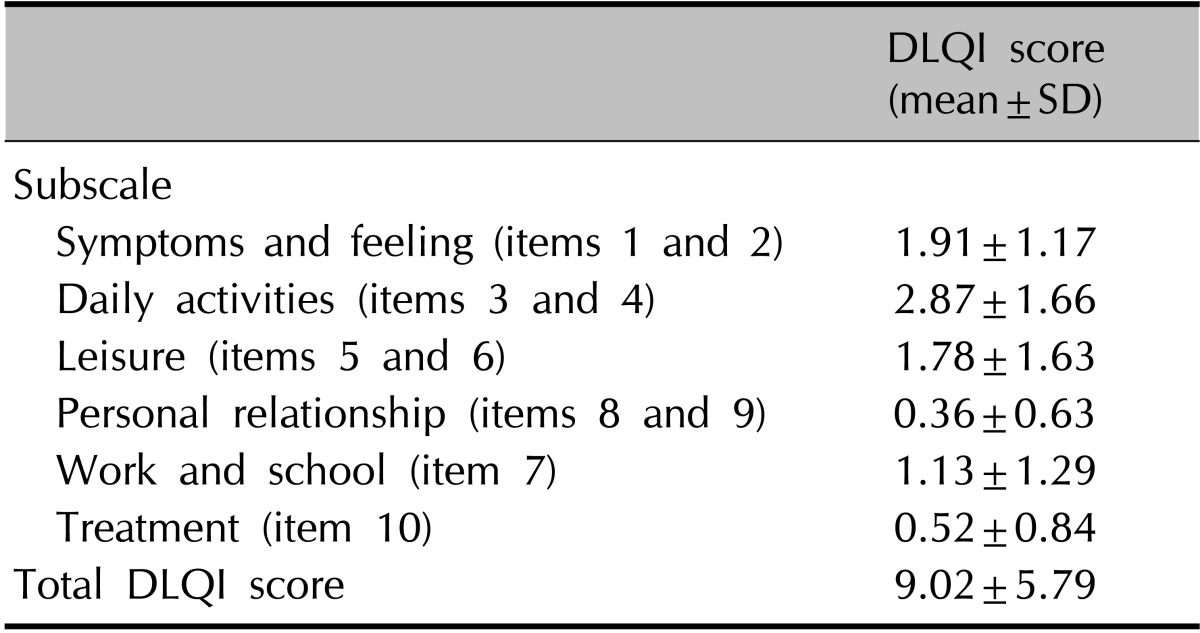

Ninety-seven patients completed a battery of questions at the time of enrollment. Post-thyroidectomy scars were classified according to morphology as linear flat scars, linear bulging scars, hypertrophic scars or adhesive scars. There were 32 patients (33.0%), 9 patients (9.3%), 41 patients (42.3%) and 15 patients (15.5%), respectively, in each group. The mean total DLQI score was 9.02. Domain 2 (daily activities, 2.87 points), which includes questions about clothing, was the most greatly impacted among patients. The total DLQI scores of patients who have experienced scar-related symptoms were significantly higher than those of patients without symptoms (p<0.05). The VSS scores were 3.09 for linear flat scars, 6.89 for linear bulging scars, 6.29 for hypertrophic scars and 5.60 for adhesive scars. However, the DLQI scores did not significantly differ among scar types or VSS scores.

Conclusion

Post-thyroidectomy scars on the neck affect the QoL of thyroid cancer patients regardless of scar type. Therefore, clinicians should pay attention to the psychological effects of scars on patients and take care to minimize post-thyroidectomy scar.

Keywords: Dermatology life quality index, Post-surgical scar, Quality of life, Scar, Thyroidectomy

INTRODUCTION

Thyroid cancer is one of the most rapidly increasing tumor types worldwide, including Korea1. Traditional thyroidectomy is the most common method of thyroid cancer surgery. In this method, the thyroid is typically approached through transverse incisions in the neck2. As a result, it causes scar formation in a highly visible area of the neck.

These visible scars cause significant cosmetic problems, leading to functional impairment and psychosocial burdens. Balci et al.3 has reported that the quality of life (QoL) of patients with keloid and hypertrophic scars is impaired as much as in patients with psoriasis. However, there are no studies investigating how much postthyroidectomy scarring affects the QoL of thyroid cancer patients relative to other types of scars, cancers, or dermatological disorders.

The Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) is a dermatology-specific QoL measure that has been widely validated in a range of skin conditions4,5. It has been used in 33 different skin conditions in 32 countries and is available in 55 languages. Therefore, the aim of this study is to evaluate the impact of postthyroidectomy scars on the QoL of thyroid cancer patients and identify the relation between scar characteristics and QoL.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

This single-center, prospective observational study was conducted from October 2011 to March 2012 at the Department of Dermatology, Gangnam Severance Hospital, Korea. Informed consent was obtained from all participants after providing extensive written and oral information about the study. The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of Gangnam Severance Hospital (Registration No. 3-2011-0193).

Patients

Thyroid cancer patients who underwent traditional thyroidectomy surgery at the Department of Surgery in Gangnam Severance Hospital, Yonsei University were assessed for inclusion. The criteria for patient selection were as follows: patients with thyroid cancer who had undergone traditional thyroidectomy procedures at least 2 months before the survey; able to provide written informed consent; aged 16 years or older; able to read the Korean language; and did not have any severe dermatological, mental, or physical illnesses.

Measures

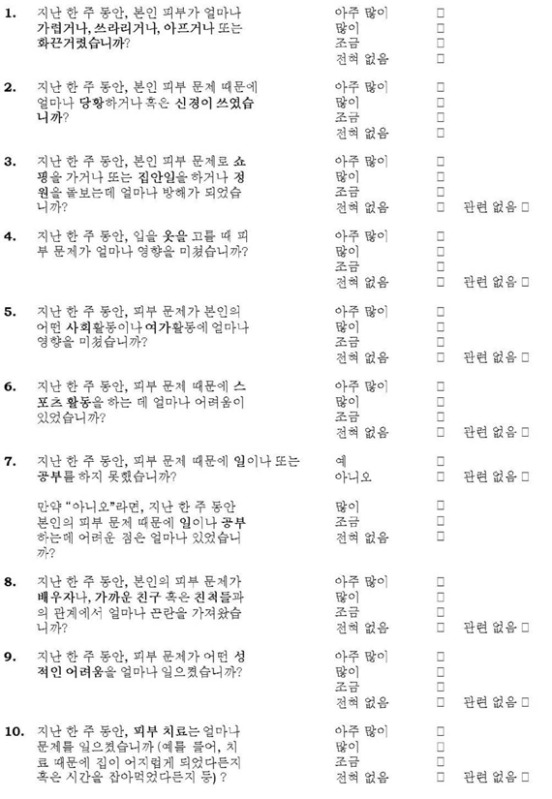

The DLQI is one of the most frequently used QoL measure in dermatology6. It consists of 10 questions and is designed for use in patients older than 16 years. The questions are classified to subscales: symptoms and feelings (questions 1 and 2), daily activities (questions 3 and 4), leisure (questions 5 and 6), personal relationships (questions 8 and 9), work and school (question 7), and treatment (question 10) (Appendix). The total DLQI score is calculated by summing the scores of the 10 questions with a maximum score of 30 and a minimum score of 0. The higher the score, the more the QoL is impaired. Grade 1 (0~1) indicates no effect, grade 2 (2~5) indicates a small effect, grade 3 (6~10) indicates a moderate effect, grade 4 (11~20) indicates a very large effect, and grade 5 (21~30) indicates an extremely large effect.7 In this study, we used a validated Korean translation of the DLQI.

Photographs of all scars were taken by using identical camera settings, patient positioning, and room lighting. Two dermatologists blinded to other study parameters performed the clinical assessment of scars by using a modified Vancouver scar scale (VSS) composed of four parameters: vascularity, thickness, pliability, and pigmentation8. To evaluate vascularity more precisely, dermoscopic examination was performed. Postthyroidectomy scar lesions present for ≤1 year were classified as active scars, whereas those present for >1 year were classified as mature scars.

Data analysis

Statistical analyses were performed by using SAS version 9.2 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Descriptive data are presented as counts with percentages and means with standard deviations. Logistic regression was used to identify relations between DLQI scores and clinical, social, and demographic factors. Risk factors with p<0.05 were considered statistically significant in a univariate model. Results are presented with p-values.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

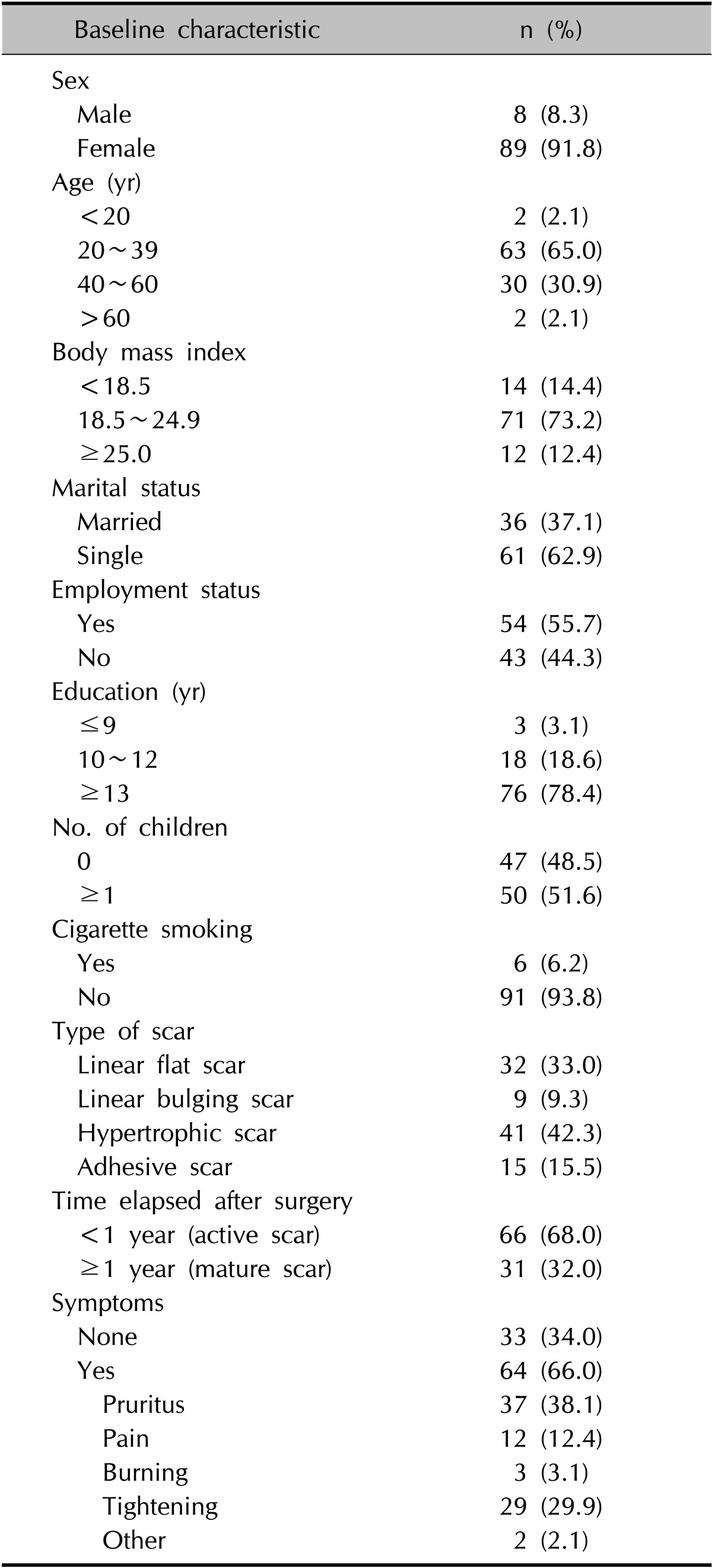

Ninety-seven patients (8 men, 89 women) were recruited for the study. The demographic and clinical characteristics of the participants are given in Table 1. The median age was 36.9 years (range, 16~64 years). The mean time that had elapsed from the thyroidectomy to the survey was 12.9 months.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients (n=97)

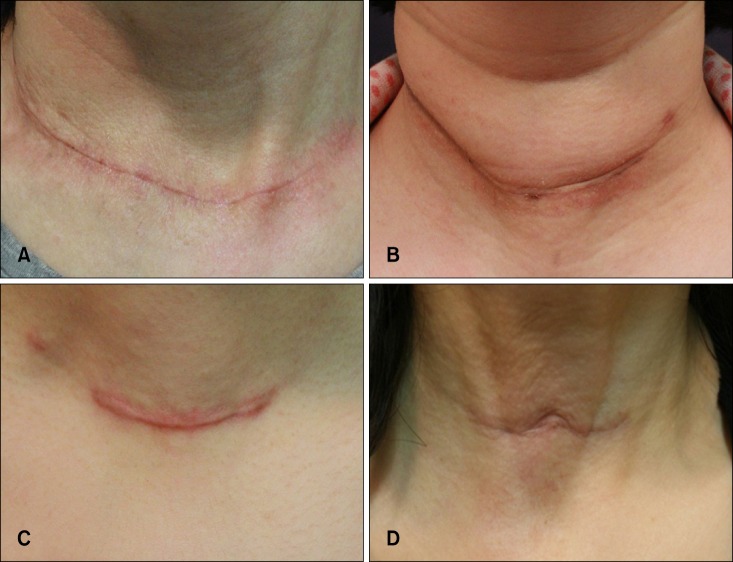

The classification and definition of postthyroidectomy scars were as follows (Fig. 1): (i) linear flat scars, flat scars with linear configuration; (ii) linear bulging scars, similar to linear flat scars but with bulging on the upper portion of the scar; (iii) hypertrophic scars, elevated scars that are typically raised and stiffer than the surrounding skin; and (iv) adhesive scars, immovable by manual inspection, and exhibiting fixation to the underlying skin.

Fig. 1.

Classification of postthyroidectomy scars. (A) Linear flat scar. (B) Linear bulging scar. (C) Hypertrophic scar. (D) Adhesive scar.

The postthyroidectomy scars were classified as linear flat scars in 32 patients (33.0%), linear bulging scars in 9 patients (9.3%), hypertrophic scars in 41 patients (42.3%), and adhesive scars in 15 patients (15.5%).

Symptoms associated with postthyroidectomy scars were present in 64 patients (66.0%), including pruritus (n=37, 38.1%), tightening (n=29, 29.9%), pain (n=12, 12.4%), and burning sensation (n=3, 3.1%). After traditional thyroidectomy, the obtained specimens were diagnosed as papillary microcarcinoma in 67 patients (69.1%), papillary carcinoma in 24 patients (24.7%), adenomatous hyperplasia in 3 patients (3.1%), follicular adenoma in 2 patients (2.1%), and thyroid goiter in 1 patient (1.0%), according to postoperative pathological evaluation.

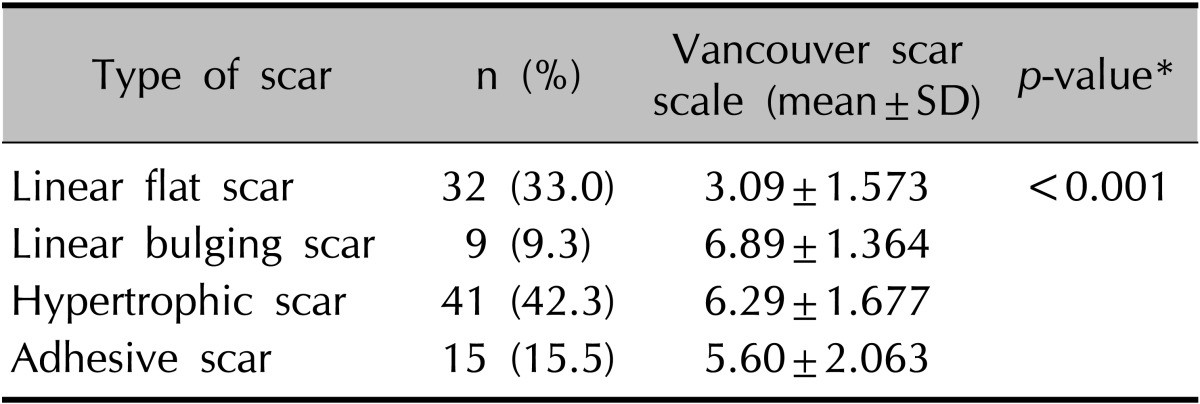

Vancouver scar scale

The VSS scores differed significantly among the types of scars (Table 2, Fig. 2; p<0.05). The mean VSS score was 5.18±2.24; the VSS scores were as follows: 3.09 for linear flat scars, 6.89 for linear bulging scars, 6.29 for hypertrophic scars, and 5.60 for adhesive scars.

Table 2.

VSS according to scar type

VSS: Vancouver scar scale, SD: standard deviation. *ANOVA.

Fig. 2.

Vancouver scar scale according to the type of scar.

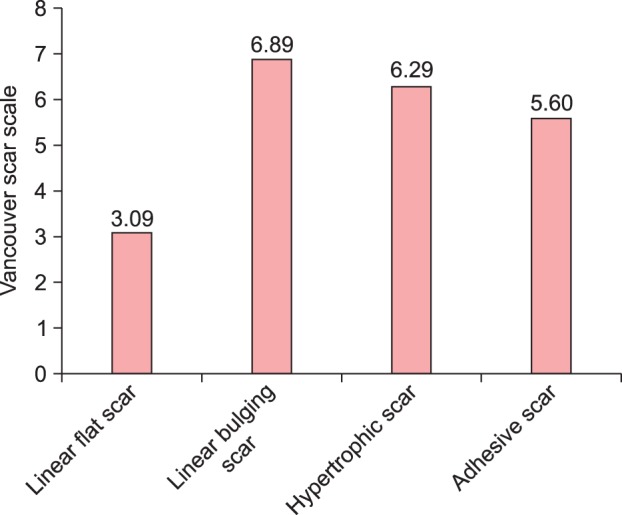

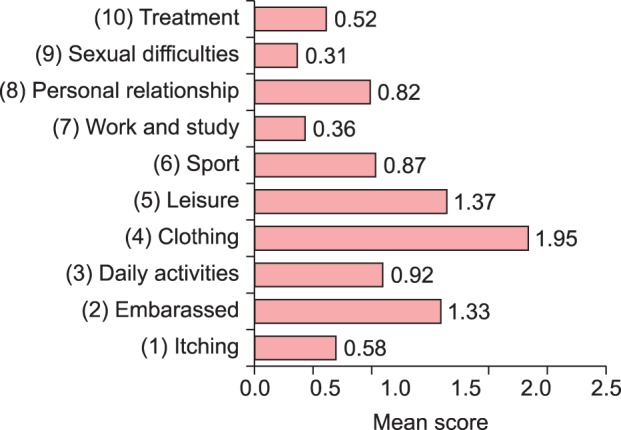

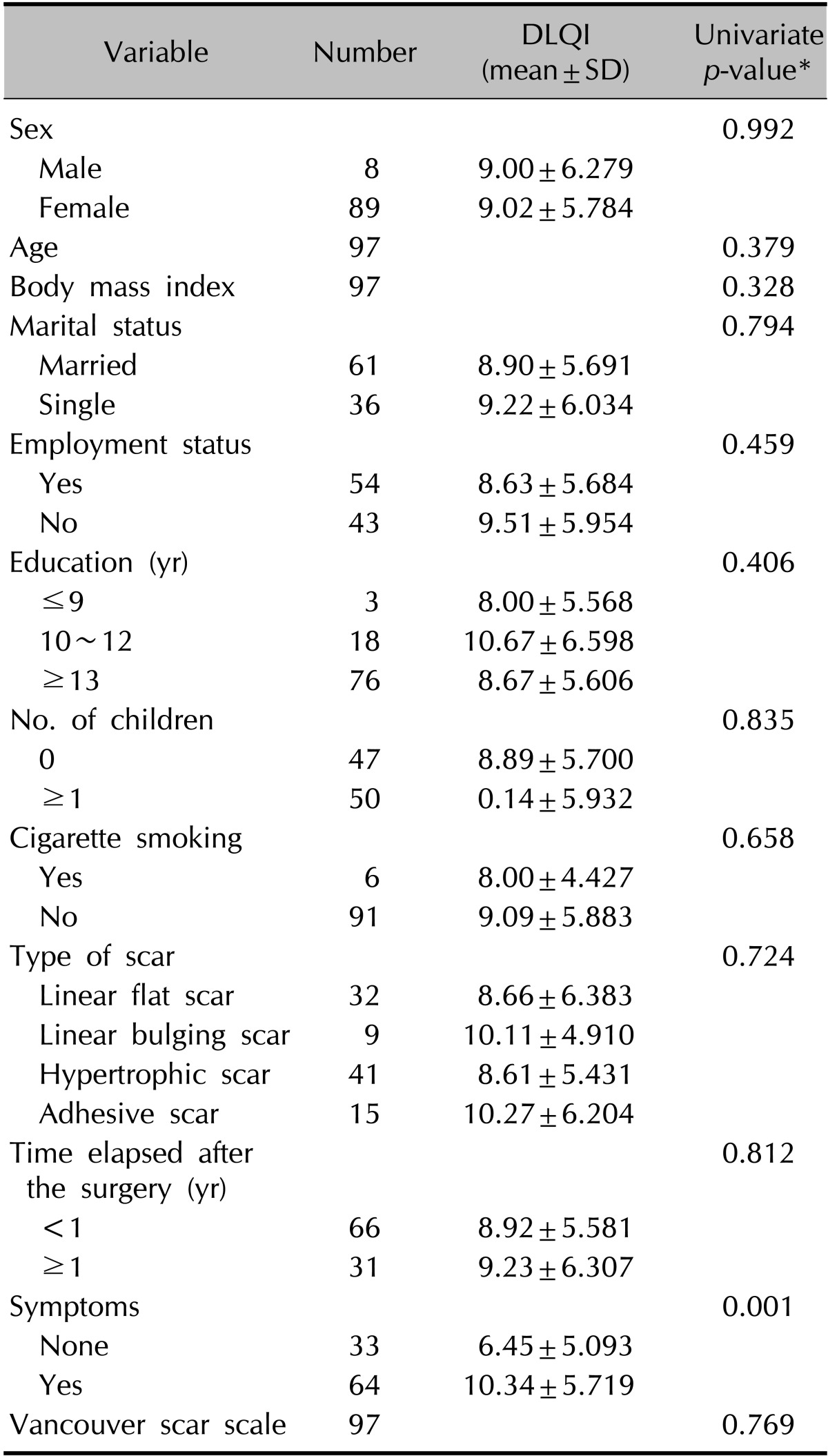

Dermatology Life Quality Index scores

DLQI indicated that postthyroidectomy scars impaired QoL in thyroid cancer patients (Table 3). The mean DLQI score was 9.02±5.79 (minimum=0, maximum=12). Domain 2 (daily activities, 2.87 points) was the most greatly affected among patients with postthyroidectomy scars. The lowest mean DLQI individual score was for item 7 (work and school, 0.36 points), whereas the highest mean DLQI score was for item 4 (clothing, 1.95 points) (Fig. 3). The relations between DLQI scores and clinical, social, and demographic factors were analyzed by using logistic regression analyses (Table 4). A univariate analysis showed that patients with associated symptoms such as pruritus, pain, burning, or tightening (ratio of mean DLQI differences in scores of patients without the symptom to patients with the symptom=6.45 : 10.34) showed greater QoL impairment. Scores were not associated with age, body mass index (BMI), employment, marital status, number of children, smoking, type of scar, time elapsed after surgery, or VSS score.

Table 3.

Distribution of subscale and total DLQI scores

DLQI: Dermatology Life Quality Index, SD: standard deviation.

Fig. 3.

Mean score of each item of the Dermatology Life Quality Index.

Table 4.

Relations between DLQI scores and disease-related patient characteristics

DLQI: Dermatology Life Quality Index, SD: standard deviation. *Univariate regression analysis.

DISCUSSION

The incidence of thyroid cancer has been increasing in many countries, including the United States, the United Kingdom, France, China, and Korea1,9,10. There has been an especially large increase in the incidence rates in women (from 2.4 to 4.5 per 100,000 population)10. As the incidence of thyroid cancer has increased, the number of thyroidectomy surgeries has also increased. Although thyroidectomy is usually performed without many complications by experienced surgeons at most medical centers, postthyroidectomy scarring is unavoidable11.

To ameliorate this adverse cosmetic outcome, there have been efforts to perform alternative techniques including transaxillary or scarless endoscopic thyroidectomy and minimally invasive thyroidectomy2,12,13. However, traditional thyroidectomy is still the most common method of thyroid surgery because it provides good direct exposure to facilitate safe dissection, and is a quick procedure with low morbidity and minimal mortality.12

As scarring after traditional thyroidectomy occurs on the anterior neck, postthyroidectomy scars are visible and exposed. Furthermore, in some patients, we have observed that traditional neck incisions could result in hypertrophic scar formation (unpublished data). Thus, patients with postthyroidectomy scars are likely to have decreased QoL.

Decreased QoL is common in patients affected by chronic skin disease. The DLQI questionnaire has been used to assess the QoL of patients with various dermatologic diseases, such as psoriasis, vitiligo, acne vulgaris, atopic dermatitis, and hypertrophic scars. In vitiligo patients, the mean DLQI scores ranged from 4.82 to 10.674,14,15,16; in patients with psoriasis and scabies, the mean DLQI scores ranged from 8.73 to 9.16 and 10.09, respectively3,5,17. The mean DLQI scores of patients with severe atopic dermatitis was 8.818. In this study, the mean DLQI score of patients with postthyroidectomy scar was 9.02, which is comparable to those of psoriasis and severe atopic dermatitis18,19.

Balci et al.3 recently compared DLQI scores in patients with keloid and hypertrophic scars to those of psoriasis patients and normal controls. The average DLQI score of patients with postthyroidectomy scars in the present study (9.02) is much higher than those of patients with hypertrophic and keloid scars (7.79) and normal controls (0.58) reported in the previous study, and is even slightly higher than that of patients with psoriasis (8.73). Rapp et al.20 reported that patients with psoriasis vulgaris experience the same reductions in QoL as patients with life-threatening diseases, such as severe heart failure. Therefore, investigations of QoL not only in patients with chronic diseases but also in those with postsurgical scars are important to appropriately manage such patients.

Moreover, the mean DLQI scores of patients who have experienced scar-related symptoms were significantly higher than those of patients without symptoms (10.34 : 6.45 points, p<0.05). In this study, 66.0% of patients (n=64) experienced more than one symptom, including pruritus, pain, burning, and tightening. This suggests that management and treatment to relieve scar-related symptoms is one of the most important aspects in the care of postthyroidectomy scars provided by attending physicians.

Interestingly, the DLQI scores of our patients with postthyroidectomy scars were not associated with either the characteristics of thyroid scars (duration, type, and VSS score) or with patient characteristics (age, sex, BMI, marital status, employment status, education, and smoking). The QoL does not seem to be associated with the severity or type of the scar, but rather with the presence of the scar itself. One study about the QoL of patients with keloids and hypertrophic scars reported similar results to ours3. The DLQI scores of patients with keloids and hypertrophic scars were not associated with age, sex, and duration of disease. Thus, all patients with postthyroidectomy scars may be affected by decreased QoL regardless of the characteristics of the scar or their own status.

Bock et al.21 reported that the QoL in patients with visible scars is poorer than in those with invisible lesions. Thyroid scars after traditional thyroidectomy are almost always located on the anterior neck. This may explain the higher DLQI scores than those of patients with hypertrophic and keloid scars.

Our study has some limitations. We classified four types of postthyroidectomy scars according to the visible morphologic type. However, some scars have mixtures of characteristics. Therefore, we classified the patients according to the most noticeable feature of the scar. Scarring, especially hypertrophic scarring, has a rapid growth phase for up to 6 months and then gradually regresses22. Scars may change in morphology over time. We assessed only a single period during the sequence of scarring. In addition, our study included a limited number of patients.

To our knowledge, this is the first attempt to measure QoL in patients with postthyroidectomy scars. Our findings suggest that the QoL of patients with postthyroidectomy scars is impaired after traditional thyroidectomy as much as that of patients with other chronic skin diseases, such as psoriasis, vitiligo, and severe atopic dermatitis. Future studies should explore the improvement of QoL through the management of postthyroidectomy scars.

Appendix

Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) questionnaire in Korean

References

- 1.Han MA, Choi KS, Lee HY, Kim Y, Jun JK, Park EC. Current status of thyroid cancer screening in Korea: results from a nationwide interview survey. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2011;12:1657–1663. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Duncan TD, Rashid Q, Speights F, Ejeh I. Transaxillary endoscopic thyroidectomy: an alternative to traditional open thyroidectomy. J Natl Med Assoc. 2009;101:783–787. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)31006-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balci DD, Inandi T, Dogramaci CA, Celik E. DLQI scores in patients with keloids and hypertrophic scars: a prospective case control study. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2009;7:688–692. doi: 10.1111/j.1610-0387.2009.07034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Finlay AY, Khan GK. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI)--a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:210–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.1994.tb01167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jin-gang A, Sheng-xiang X, Sheng-bin X, Jun-min W, Song-mei G, Ying-ying D, et al. Quality of life of patients with scabies. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:1187–1191. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown BC, McKenna SP, Siddhi K, McGrouther DA, Bayat A. The hidden cost of skin scars: quality of life after skin scarring. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2008;61:1049–1058. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2008.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hongbo Y, Thomas CL, Harrison MA, Salek MS, Finlay AY. Translating the science of quality of life into practice: What do dermatology life quality index scores mean? J Invest Dermatol. 2005;125:659–664. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2005.23621.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Idriss N, Maibach HI. Scar assessment scales: a dermatologic overview. Skin Res Technol. 2009;15:1–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0846.2008.00327.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davies L, Welch HG. Increasing incidence of thyroid cancer in the United States, 1973-2002. JAMA. 2006;295:2164–2167. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.18.2164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang Y, Wang W. Increasing Incidence of Thyroid Cancer in Shanghai, China, 1983-2007. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2012 doi: 10.1177/1010539512436874. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bargren AE, Meyer-Rochow GY, Delbridge LW, Sidhu SB, Chen H. Outcomes of surgically managed pediatric thyroid cancer. J Surg Res. 2009;156:70–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2009.03.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tan CT, Cheah WK, Delbridge L. "Scarless" (in the neck) endoscopic thyroidectomy (SET): an evidence-based review of published techniques. World J Surg. 2008;32:1349–1357. doi: 10.1007/s00268-008-9555-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alvarado R, McMullen T, Sidhu SB, Delbridge LW, Sywak MS. Minimally invasive thyroid surgery for single nodules: an evidence-based review of the lateral mini-incision technique. World J Surg. 2008;32:1341–1348. doi: 10.1007/s00268-008-9554-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kent G, al-Abadie M. Factors affecting responses on Dermatology Life Quality Index items among vitiligo sufferers. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1996;21:330–333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dolatshahi M, Ghazi P, Feizy V, Hemami MR. Life quality assessment among patients with vitiligo: comparison of married and single patients in Iran. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2008;74:700. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.45141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parsad D, Pandhi R, Dogra S, Kanwar AJ, Kumar B. Dermatology Life Quality Index score in vitiligo and its impact on the treatment outcome. Br J Dermatol. 2003;148:373–374. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2003.05097_9.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin TY, See LC, Shen YM, Liang CY, Chang HN, Lin YK. Quality of life in patients with psoriasis in northern Taiwan. Chang Gung Med J. 2011;34:186–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Misery L, Finlay AY, Martin N, Boussetta S, Nguyen C, Myon E, et al. Atopic dermatitis: impact on the quality of life of patients and their partners. Dermatology. 2007;215:123–129. doi: 10.1159/000104263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mazzotti E, Barbaranelli C, Picardi A, Abeni D, Pasquini P. Psychometric properties of the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) in 900 Italian patients with psoriasis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2005;85:409–413. doi: 10.1080/00015550510032832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rapp SR, Feldman SR, Exum ML, Fleischer AB, Jr, Reboussin DM. Psoriasis causes as much disability as other major medical diseases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:401–407. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(99)70112-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bock O, Schmid-Ott G, Malewski P, Mrowietz U. Quality of life of patients with keloid and hypertrophic scarring. Arch Dermatol Res. 2006;297:433–438. doi: 10.1007/s00403-006-0651-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gauglitz GG, Korting HC, Pavicic T, Ruzicka T, Jeschke MG. Hypertrophic scarring and keloids: pathomechanisms and current and emerging treatment strategies. Mol Med. 2011;17:113–125. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2009.00153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]