To the Editor:

We previously reported that inner-city childhood asthma was associated independently with measures of early childhood exposure to bisphenol A (BPA)1and prenatal, but not childhood, exposures to di-n-butyl phthalate (DnBP) and butylbenzyl phthalate (BBzP).2 Here we evaluate whether these two classes of endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs) interact to increase risk of asthma.

Method

We evaluated n=292 inner-city women and their children ages 5-11 years from the Columbia Center for Children's Environmental Health (CCCEH) birth cohort of pregnant women who delivered between 1998-2006. Enrollment, exclusion criteria, and a description of the cohort have been described previously.3 Subjects were selected for the current study based on availability of: (1) measurements of phthalates in spot urine collected from the mother during pregnancy (33.9±3.1 weeks gestation) and BPA in child urine at ages 3 (n=237), 5 (259) and/or 7 (n=161) years; (2) data on child asthma and wheeze-related outcomes; and (3) availability of model covariates. Demographics on CCCEH subjects are provided in the online repository (Table E1). All participants gave written informed consent.

Samples were analyzed at the Center for Disease Control and Prevention for concentrations of monobenzyl phthalate (MBzP metabolite of BBzP), mono-n-butyl phthalate (MnBP, metabolite of DnBP) and BPA.4, 5 Consistent with our prior approach,1 mean urinary postnatal BPA concentrations were calculated across child ages 3-7 year samples, except for a small subset (n=10) missing respiratory questionnaire data after age 6 years for whom the mean BPA was calculated for ages 3-5 years. Specific gravity was measured using a handheld refractometer (Atago PAL 10-S, Bellevue, WA) to control for urinary dilution.

Repeat questionnaires, including the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood (ISAAC) were administered to the parent at child ages 5, 6 7, 9 and 11 years (n=1202 questionnaires, average 4.1 per child). Children with report in the last 12 months of any of the following asthma-related symptoms on ≥ one questionnaire were referred to an allergist or pulmonologist for asthma diagnosis using standardized criteria: wheeze or whistling in the chest; a cough that lasted more than a week; other breathing problems; and/or use of asthma rescue or controller medication.1 Children without any of these asthma-related symptoms on the repeat questionnaires were classified as non-asthmatic. Children were evaluated for persistent wheeze (≥ 3 reports of wheeze in the last 12 months on ≥ 3 ISAAC questionnaires), exercise-induced wheeze (≥ 1 report in the last 12 months of the child's chest sounding wheezy during or after exercise) and report of emergency care visits in the last 12 months to a doctor, clinic or emergency room for asthma, wheeze or other breathing problems on ≥ 1 repeat questionnaire.

Variables assessed as potential confounders have been described 1,2 and were retained in the models if they were significant (p < 0.05) and/or their inclusion resulted in greater than 10% change in the predictor variables (see online repository). Prior to statistical analyses, the one prenatal MBzP and 15 postnatal BPA concentrations below the limit of detection (LOD; 0.22 µg/L [MBzP] and 0.4 μg/L [BPA]) were assigned a value of half the LOD. Metabolite concentrations were right-skewed and transformed using the natural logarithm. In analyses in which metabolites were categorized, we adjusted concentrations by specific gravity prior to ranking as described previously.6 Consistent with our prior approach,2 we used a modified Poisson regression to generate relative risk (RR), and variance estimates for dichotomized outcomes (i.e. child asthma) using the methods of Zou.7 Analyses were conducted using SPSS 21. Results were considered significant at p<0.05.

Results

A total of 168/292 (57.5%) of the children had a history of the asthma-related symptoms on repeat questionnaires. Of these, 142 were evaluated by a study allergist or pulmonologist; 86 were diagnosed with current asthma and 56 with the asthma-related symptoms but without current asthma. The remaining 124 children had no history of the asthma-like symptoms and were classified as non-asthmatic. 44/217 (20%) children had persistent wheeze, 62/292 (21%) had exercise-induced wheeze and 98/292 (34%) had emergency care visits for asthma or other respiratory problems.

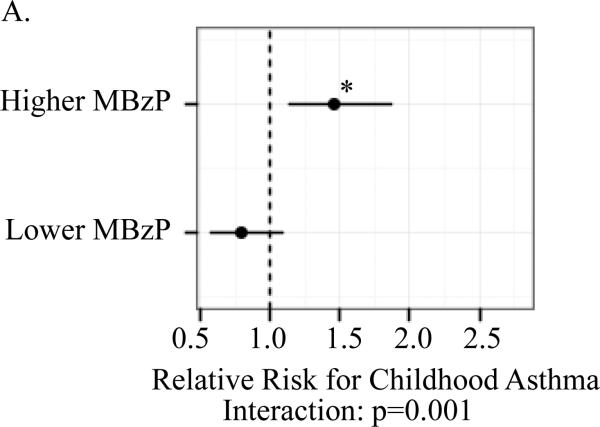

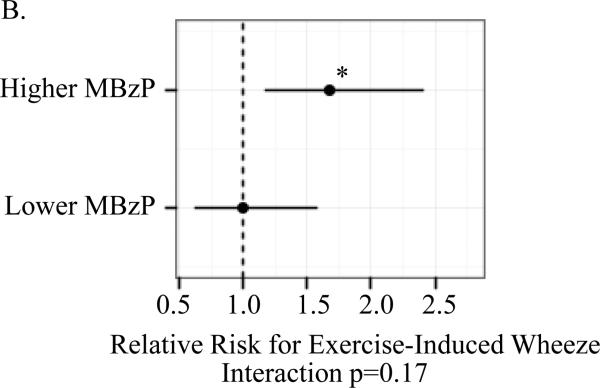

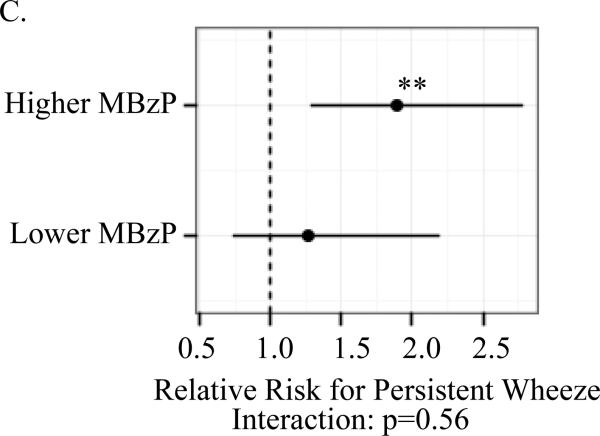

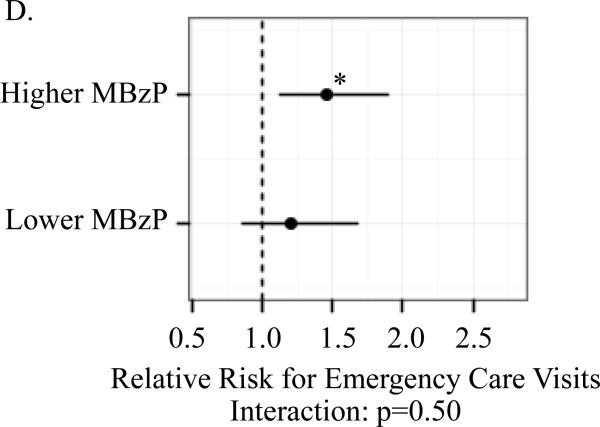

A significant association between child (ln)BPA concentrations and the respiratory outcomes was observed only among children whose mothers had prenatal MBzP concentrations above but not below the median. For children with prenatal MBzP concentrations above the median, the RR per log uinit increase in child BPA concentrations were: 1.46 (95% CI 1.14, 1.87) for child current asthma; 1.89 (95% Ci 1.29, 2.78) for persistent wheeze; 1.67 (95% Ci 1.17, 2.40) for exercise-induced wheeze; and 1.47 (95% CI 1.13, 1.89) for emergency care visits. The multiplicative interaction between child (ln)BPA and higher versus lower prenatal MBzP was significant for asthma (p=0.001) but not the other outcomes (Figure 1).

Figure I.

Association between child (ln)BPA concentrations by strata of higher versus lower prenatal MBzP (above and below median) and child asthma (A), exercise-induced wheeze (B), persistent wheeze (C) and emergency care vists (D)

Models controlled for maternal asthma, household smoke exposure, maternal prenatal BPA, maternal prenatal specific gravity, maternal prenatal demoralization, child age at asthma diagnosis or classification as non-asthmatic (A), child sex (B-D). Mutiplicative interactions between postnatal (ln)BPA concentrations and higher versus lower prenatal MBzP were also evaluated for each outcomes (A-D). *p<0.01 **p≤0.001

Table 1 shows associations between asthma and the wheeze-related outcomes among children with both prenatal MBzP and child BPA concentrataions above the median compared to children with one or both measurements below the median. There was a highly significant increase in RR for all of these outcomes among children with both prenatal MBzP and child BPA above the median. By contrast, there was no increase in RR if only one of the EDCs but not both were above the median (p-values ranged from 0.12-0.94, data not shown). There were no significant interactions between (1) prenatal BPA and either prenatal MBzP or MnBP concentrations or (2) prenatal MnBP and child BPA concentations on risk of child asthma, frequent wheeze, exercised-induced wheeze or emergency care visits (data not shown).

Table I.

Asthma-related outcomes among children with both maternal prenatal MBzP and child BPA above the median versus one or both below the median.

| Relative risk (95% confidence interval) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Childhood asthma (n=210) | Persistent wheeze (n=217) | Exercise-induced wheeze (n=292) | Emergency care visits (n=292) |

| 1.67 (1.25, 2.23)** | 2.02 (1.22, 3.35)* | 1.76 (1.13, 2.72)* | 1.71 (1.25, 2.34)** |

Models controlled for maternal asthma, household smoke exposure, prenatal BPA, maternal prenatal specific gravity, maternal prenatal demoralization, child age (at the time of asthma diagnosis included in asthma model only) and child sex (in models of the other asthma-related outcomes).

p≤0.01

p≤0.001

Discussion

Using two analytic approaches, we found a novel and significant association between child BPA and risk of child asthma and other wheeze-related symptoms among inner-city children whose mothers had higher but not lower prenatal measures of exposures to BBzP. These findings suggest the possibility of a ‘multi-hit’ model such that higher prenatal BBzP exposures may render the child more susceptible to adverse effects of BPA on the airways during early childhood. While potential mechanisms for this hypothesis need to be evaluated and results require replication, findings are of concern given that exposures to these compounds are ubiquitous in the U.S. and other countries.

Detail on the methods and subject characteristics

Women 18-35 years old who self-identified as African American or Dominican were enrolled through prenatal clinics at Harlem Hospital and New York Presbyterian Hospital. Women were excluded if they reported active smoking, use of other tobacco products or illicit drugs, had diabetes, hypertension or known HIV, had their first prenatal visit after the 20th week of gestation or had resided in the study area for less than one year prior to pregnancy. Family history of asthma was not a required inclusion criterion. Study subject characteristics are provided in Table S1 below. The 292 subjects did not differ significantly from the remaining 435 subjects in the CCCEH cohort by race/ethnicity, maternal prenatal marital status and education level, household income, prenatal and postnatal tobacco smoke, or maternal history of asthma (all p-values ≥0.16). All participants provided written informed consent, child age 7 and older provided assent and the institutional review boards at the Columbia University Medical Center and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention approved the study.

Variables assessed as potential confounders were selected based on our prior analyses of prenatal MBzP and postnatal BPA as described18, 19 and were retained in the models if they were significant (p < 0.05) and/or their inclusion in the model resulted in greater than 10% change in the predictor variables. The variables assessed as potential confounders included maternal age, maternal education, maternal history of asthma, race/ethnicity, household smoke exposure (from others during pregnancy as the cohort was restricted to non-smoking pregnant women at enrollment and from the mother and/or others during childhood as some mothers began smoking after delivery), number of previous live births, breastfeeding history, number of previous live births (0, 1-3, >3), maternal prenatal BPA concentrations, child age at asthma diagnosis or classification as non-asthmatic, child sex, and child BMI. Maternal prenatal demoralization (measured by a 27-item Psychiatric Epidemiology Research Instrument-Demoralization Scale (Dohrenwend et al. 1978)) also was assessed, as it previously has been associated with wheeze among children in the cohort (Reyes et al. 2011). Prenatal and postnatal urinary specific gravity concentrations were included in models to control for urinary dilution. We did not collect a validated history of all child viral illnesses from cohort subjects by questionnaire as we did not believe we could do so reliably at the onset of the study. Therefore we were not able to determine whether or not child viral illnesses were potential confounders. Child postnatal MBzP and MnBP concentrations were not controlled, as they were not associated with any of the outcomes (all p-values ≥ 0.4) and inclusion did not alter results over those presented here. The cohort was predominantly full-term (97% ≥37 weeks gestation) and neither gestational age nor birth weight were confounders.

Supplementary Material

Capsule summary.

In a novel ‘multi hit’ model, prenatal exposure to butylbenzyl phthalate and childhood exposure to bisphenol A interact to increase risk of childhood asthma in an inner-city minority population.

Acknowledgments

Sources of support: Funding was provided by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences: R01ES014393, RC2ES018784, R01ES13163, R01ES08977 and NIEHS/EPA P01 ES09600/RD 83214101, P30ES009089; the John and Wendy Neu Family Foundation; Blanchette Hooker Rockefeller Fund; New York Community Trust; and the Millstream Fund. The findings expressed in this paper are the opinions of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Donohue KM, Miller RL, Perzanowski MS, Just AC, Hoepner LA, Arunajadai S, et al. Prenatal and postnatal bisphenol A exposure and asthma development among inner-city children. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131:736–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.12.1573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Whyatt RM, Perzanowski MS, Just AC, Rundle AG, Donohue KM, Calafat AM, et al. Asthma in Inner-City Children at 5-11 Years of Age and Prenatal Exposure to Phthalates: The Columbia Center for Children's Environmental Health. Environ Health Perspect. 2014 doi: 10.1289/ehp.1307670. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perera F, Viswanathan S, Whyatt R, Tang D, Miller RL, Rauh V. Children's environmental health research--highlights from the Columbia Center for Children's Environmental Health. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1076:15–28. doi: 10.1196/annals.1371.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kato K, Silva MJ, Needham LL, Calafat AM. Determination of 16 phthalate metabolites in urine using automated sample preparation and on-line preconcentration/high-performance liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2005;77:2985–91. doi: 10.1021/ac0481248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ye X, Kuklenyik Z, Needham LL, Calafat AM. Automated on-line column-switching HPLC-MS/MS method with peak focusing for the determination of nine environmental phenols in urine. Anal Chem. 2005;77:5407–13. doi: 10.1021/ac050390d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hauser R, Meeker JD, Park S, Silva MJ, Calafat AM. Temporal variability of urinary phthalate metabolite levels in men of reproductive age. Environ Health Perspect. 2004;112:1734–40. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zou G. A modified poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159:702–6. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.