Abstract

Serum amyloid A (SAA) is a major acute-phase protein and a precursor of amyloid A, the deposit of which leads to amyloidosis. Different alleles exist in SAA1, a predominant form of the human SAA gene family. Emerging evidence has shown correlations between these alleles and diseases including familiar Mediterranean fever and amyloidosis. However, it remains unclear how the proteins encoded by these SAA1 alleles act differently. Here we report the characterization of proteins encoded by SAA1.1, SAA1.3 and SAA1.5, in comparison to that encoded by SAA2.2, for their preference of the SAA receptors including formyl peptide receptor 2 (FPR2) and Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2). SAA1.1 was more efficacious than SAA1.3 and SAA1.5 but equally efficacious to SAA2.2 in calcium mobilization and chemotaxis assays, which measure the activation of the G protein-coupled FPR2. In agreement with this, SAA1.1 and SAA2.2 induced more robust phosphorylation of ERK than SAA1.3 and SAA1.5. Only small differences were observed between the SAA1 proteins tested and SAA2.2 in TLR2-dependent NF-κB luciferase reporter assay. In comparison, SAA1.3 was most effective in stimulating ERK and p38 MAPK phosphorylation. Using bone marrow-derived macrophages from C57BL/10ScN (Tlr4lps-del) mice, we examined the SAA isoforms for their induction of selected pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines. SAA1.3 was most potent in the induction of TNFα and IL-1rn, whereas SAA1.5 induced robust IL-10 expression. These results show differences of the SAA1 isoforms in their selectivity for the SAA receptors, which may affect their roles in modulating inflammation and immunity.

Keywords: Serum amyloid A, inflammation, innate immunity, polymorphism, Toll-like receptors, formyl peptide receptors

Introduction

Human serum amyloid A (SAA) is a family of proteins consisting of SAA1, SAA2, and SAA4 (Uhlar and Whitehead, 1999). Among these proteins, SAA1 and SAA2 are largely responsible for the rapid rise in its plasma concentration by up to 1,000-fold during acute-phase response (Kushner and Rzewnicki, 1999). Increased levels of SAA1 and SAA2 correlate with the severity of inflammatory diseases such as atherosclerosis (Fyfe et al., 1997), rheumatoid arthritis (O’Hara et al., 2000) and several cancer variants (Malle et al., 2009). SAA is one of the agonists for the G protein-coupled formyl peptide receptor 2 (FPR2) (Su et al., 1999, Ye et al., 2009), which not only mediates SAA-induced IL-8 release (He et al., 2003), but also contributes to inflammation by rescuing neutrophils from apoptosis via the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and Akt signaling pathways (El Kebir et al., 2007). Binding of SAA to FPR2 may contribute to the destruction of bone and cartilage via the promotion of synoviocyte hyperplasia and angiogenesis, which also involves the p42/44 MAPK and Akt signaling similarly to that in neutrophils (Lee et al., 2006).

In addition to FPR2, several receptors for SAA have been identified. These include the scavenger receptor SR-BI (Baranova et al., 2005, Cai et al., 2005), the receptor for advanced glycation end product (RAGE) (Yan et al., 2000), and two of the Toll-like receptors. Cheng and coworkers (Cheng et al., 2008) reported that SAA could act as an endogenous agonist for the Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2), a finding confirmed in independent studies (Ather et al., 2011, O’Reilly et al., 2014, Sun et al., 2014). SAA binding to TLR2 results in NF-κB activation and enhanced expression of proinflammatory and anti-apoptotic genes. Moreover, other studies demonstrate that SAA stimulates G-CSF production through TLR2, leading to neutrophilia (He et al., 2009). These and other functions contribute to the pathogenesis of chronic inflammatory diseases.

SAA1, encoding a major form of acute-phase SAA, contains single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in both coding sequence and non-coding sequence (Buxbaum, 2006, Kluve-Beckerman et al., 1986). Two single nucleotide polymorphisms at exon 3 of SAA1 lead to three different SAA1 alleles that code for SAA1.1 (Val52-Ala57), SAA1.3 (Ala52-Ala57), and SAA1.5 (Ala52-Val57). Published reports have shown that these allelic differences may influence the development of amyloidosis. For instance, SAA1.1 has been considered a risk factor for amyloidosis in patients with RA (van der Hilst et al., 2008). Moreover, different alleles of SAA1 have been associated with other chronic diseases and cancer (Lung et al., 2014, Malle et al., 2009). However, the underlying mechanisms have not been fully understood. In this study, we compared the three SAA1 isoforms and SAA2.2 for their ability to activate FPR2 and TLR2. Our results show that the three major SAA1 isoforms differ in their preference of FPR2 and TLR2, displaying different efficacy in cellular activities such as chemotaxis, calcium mobilization and induction of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines. These SAA1 isoforms were compared with SAA2.2, which was nearly as potent as SAA1.1 in the functional assays. These findings indicate that the SAA1 isoforms may play different roles in the modulation of inflammation and immunity through their selectivity for the two SAA receptors.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

FLIPR calcium 5 reagent was obtained from Molecular Devices (Sunnyvale, CA). The anti-phospho-MAPK (ERK, p38) polyclonal antibodies were obtained from Cell Signaling Technologies (Beverly, MA). Polyvinylpyrrodone-free polycarbonate filter was obtained from GE Water & Process Technologies (Trevose, PA). Other chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

Animals

C57BL/10ScN (Tlr4lps-del) mice were purchased from Nanjing University Model Animal Research Institute (Nanjing, China).

SAA expression and purification

The SAA1 isoforms and SAA2.2 were designed for soluble expression in Escherichia coli. The human SAA1.1 cDNA was cloned into a pET28a-His6-SUMO vector downstream of the SUMO tag. The resulting construct was transformed into the Escherichia coli strain BL21(DE3). The SAA1.3, SAA1.5 and SAA2.2 constructs were obtained through site-directed mutagenesis using the pET28a-His6-SUMO-SAA1.1 expression construct as template. The transformed BL21(DE3) cells were grown in LB media at 37°C to an OD600 of 1.0. Isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside (1 mM final) was added to induce the expression of the proteins at 16°C overnight. The cultures were harvested and the proteins were purified by Ni2+ affinity chromatography. The purified proteins were treated with TEV protease and then again purified by Ni2+ affinity chromatography to remove the His6-SUMO tag. The recombinant SAA1 isoforms and SAA2.2 were stored in 20 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4). A BCA Protein Assay Kit (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) was used to determine the protein content. Tachypleus Amebocyte Lysate (TAL, Zhanjiang A&C Biological Ltd., Guangdong, China) was used for endotoxin level measurement.

SAA-induced cytokines gene expression

Bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDM) from C57BL/10ScN (Tlr4lps-del) mice (1×106 cells/sample) were stimulated with 1 μM SAA. Total RNA was prepared after the indicated time of stimulation. Real-time PCR was conducted on an ABI Prism 7000 sequence detection system using SYBR Green and the ΔCt (threshold cycle) method for quantification. The expression of GAPDH was used as an internal control. Cell-free supernatant was collected, centrifuged and assayed for selected cytokines using ELISA kits (Mlbio, Shanghai, China).

Calcium Mobilization

The rat basophilic leukemia cell line RBL-2H3 (CRL-2256, ATCC, Manassas, VA) was transfected with an expression vector SFFV.neo containing the human FPR2 (previously named FPRL1) cDNA, as described (Nanamori et al., 2004). RBL-FPR2 cells were grown to 90% confluence in black wall/clear bottom 96-well assay plates. The calcium mobilization assay was performed using FLIPR calcium 5 reagent according to manufacturer’s recommendation. After 1 h incubation with the reagent (37°C, with 5% CO2), SAA1 isoforms and SAA2.2 were added robotically, and samples were read in a FlexStation III multi-reader (Molecular Devices) with an excitation wavelength of 485 nm and an emission wavelength of 525 nm. Data were acquired by SoftMax Pro 6 (Molecular Devices) and analyzed with Origin 7.5 software (Northampton, MA).

Chemotaxis

Migration of RBL-2H3-FPR2 induced by SAA1 isoforms and SAA2.2 was assessed using a 48-well microchemotaxis chamber (Neuro Probe, Cabin John, MD). The SAA proteins (2 μM) were placed in wells (30 μl) of the lower compartment, and cells (50 μl of a 5×105/ml suspension) were seeded into wells of the upper compartment, which was separated from the lower compartment by a polyvinylpyrrodone-free polycarbonate filter (8-μm pore size). The filter was pre-coated with 10 μg/ml collagen (Cat. No. C9791; Sigma-Aldrich) for 60 min. The chamber was incubated in a humidified environment at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 4 h. The membrane was removed, fixed in methanol, and stained with crystal violet solution for 30 min followed by destaining with water. The cells that migrated across the membrane were counted using light microscopy. Chemotaxis index was calculated as the ratio of the number of cells migrated towards chemoattractant divided by the number of cells migrated towards medium.

NF-κB luciferase reporter assay

SAA-induced expression of a NF-κB-directed luciferase reporter was conducted using stable transfected cell line TLR2-HeLa, as previously reported (Cheng et al., 2008). For luciferase reporter assay, TLR2-HeLa cells were transiently transfected in 12-well cell culture plates with 0.9 μg NF-κB luciferase reporter and 0.1 μg pRL-TK (expression of Renilla luciferase). Twenty-four hours after transfection, the cells were starved in serum-free medium for 16 h and then stimulated with SAA1 isoforms or SAA2.2 for 4 h. The NF-κB driven expression of firefly luciferase was determined, and data were normalized against Renilla luciferase activity.

MAPK phosphorylation

TLR2-HeLa cells were plated in six-well plates at 2×106/well and starved in serum-free DMEM overnight. SAA1 isoforms and SAA2.2 were used to stimulate TLR2-HeLa cells for different time intervals. Cells were then collected and lysed. The cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting. Phosphorylation of MAPKs was detected by antibodies against p38 MAPK (Thr180/Tyr182), ERK (Thr202/Tyr204), and the respective total MAPKs (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA). The relative level of phosphorylation was quantified by densitometry analysis of the blots using the ImageJ software (NIH, Bethesda, MD).

Results

Expression and characterization of recombinant SAA proteins

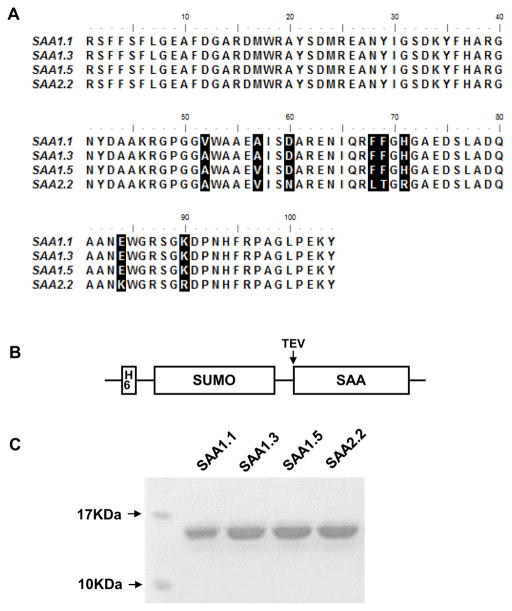

The three major SAA1 alleles (SAA1.1, 1.3 and 1.5) encode proteins with different amino acids at positions 52 and 57 of the mature SAA protein (Fig. 1A). Previous studies have shown that these SAA1 isoforms might contribute differently to chronic diseases such as amyloidosis (Buxbaum, 2006) and nasopharyngeal carcinoma (Lung et al., 2014). To understand the action mechanisms underlying the difference, we prepared recombinant proteins representing 3 different human SAA1 isoforms, using similarly prepared SAA2.2 for comparison. When expressed in E. coli, SAA1 proteins are often present within the inclusion bodies with loss of functions (data not shown). To overcome this technical difficulty, a fusion construct was prepared that contains His6-SUMO (small ubiquitin-related modifier) tags upstream of the mature SAA protein, separated by a cleavage site for tobacco etch virus (TEV) protease (Fig. 1B). This design not only improved solubility of the recombinant fusion protein but also facilitated protein purification. The resulting SAA1 isoforms and SAA2.2 were purified to at least 95% (Fig. 1C), with endotoxin level controlled below 0.08 ng/μg of SAA1 protein (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Sequence alignment, expression and purification of SAA1 isoforms. (A) Mature protein sequences (without signal peptide) of the 3 SAA isoforms and SAA2.2 are compared. Different amino acids are shown in reverse color. (B) Expression construct of SAA1 isoforms. A SUMO tag is added to increase solubility, and a 6xHis tag was added to facilitate purification. TEV marks the tobacco etch virus protease cleavage site. (C) Expression of the SAA1 isoforms and SAA2.2 protein in E. coli. Gel image shows a single species with apparent molecular weight of ~15 kDa (the calculated molecular mass is 12 kDa). The purity of the expressed proteins is estimated to be 95% or higher.

Table 1.

Properties of the recombinant SAA isoforms. SAA1.1, 1.3, 1.5 and SAA2.2 were expressed in the E. coli strain BL21 (DE3). The endotoxin level of purified SAA protein was measured using Tachypleus amoebocyte lysate. Molecular weight and isoelectric points are also shown.

| Protein | Source | Molecular weight(KDa) | Purity | Endotoxin level | Isoelectric point |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SAA1.1 | E. coli | 12.026 | ≥95% | <0.08 ng/μg | 5.55 |

| SAA1.3 | E. coli | 11.998 | ≥95% | <0.08 ng/μg | 5.55 |

| SAA1.5 | E. coli | 12.026 | ≥95% | <0.08 ng/μg | 5.55 |

| SAA2.2 | E. coli | 11.991 | ≥95% | <0.08 ng/μg | 8.05 |

Bioactivity of the SAA1 isoforms and SAA2.2 at FPR2

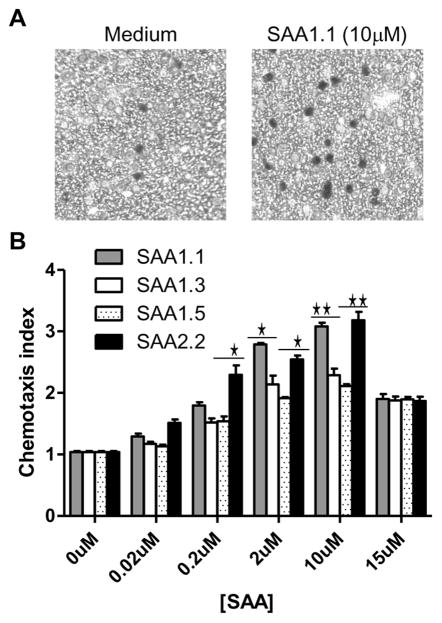

The G protein-coupled receptor FPR2 is a functional receptor for SAA, which stimulates neutrophil chemotaxis (Su et al., 1999) and production of the chemokine IL-8 as well as matrix metalloproteases such as MMP9 (He et al., 2003, Lee et al., 2005). Since other SAA receptors such as TLR2 are also present in neutrophils and macrophages (Cheng et al., 2008, He et al., 2009), we used the transfected rat basophilic leukemia cell line RBL-2H3 that express the human FPR2 (RBL-FPR2) to observe SAA-induced activities through FPR2. Different SAA1 isoforms could induce chemotaxis of the RBL-FPR2 cells in microchemotaxis chambers (Fig. 2A). Cell migration peaked at 10 μM, generating typical bell-shaped dose curves (Fig. 2B). An analysis of the dose curves identified SAA1.1 and SAA2.2 as being most efficacious in the induction of chemotaxis. In comparison, SAA1.3 and SAA1.5 were less efficacious as they induced less cell migration even when applied at higher concentrations (10 and 15 μM).

Fig. 2.

Chemotaxis of RBL-FPR2 cells induced by the SAA1 isoforms and SAA2.2. Migration of RBL-FPR2 induced by the SAA1 isoforms and SAA2.2 was assessed using a 48-well microchemotaxis chamber. (A) Sample images of cells migrated through polycarbonate filter (8-μm pore size) after incubation for 4 h with medium (left) and SAA1.1 (right). (B) Chemotaxis index was calculated as the ratio of the number of cells migrated toward stimuli over those migrated toward medium. Data from one of three representative experiments are shown. Statistical significance was determined using two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test. The SAA1.1- and SAA2.2-stimulated samples display higher chemotaxis indexes at some concentrations (*, p < 0.05, **, p < 0.01, compared with SAA1.3- and SAA1.5-stimulated samples).

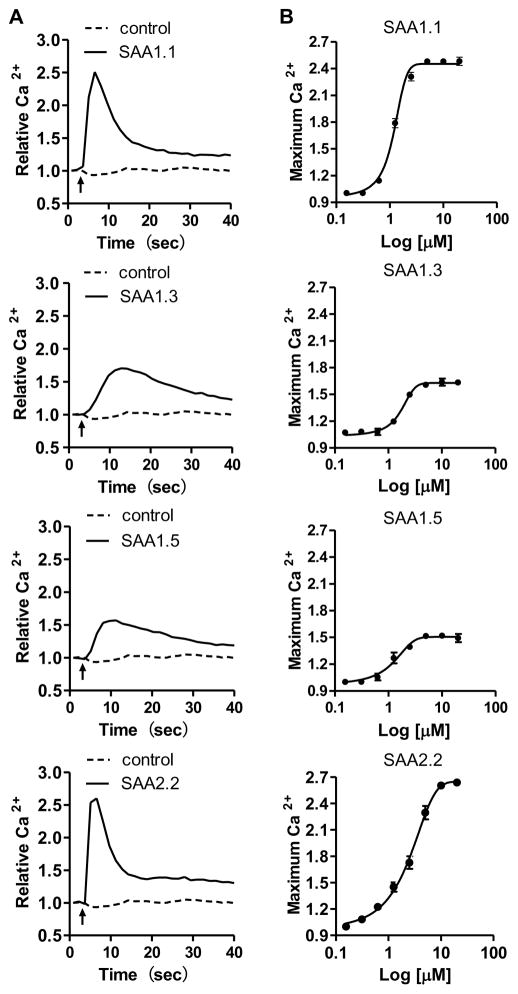

In addition to chemotaxis, Ca2+ mobilization is a cellular function mediated by activated FPR2 (He et al., 2003, Su et al., 1999) but not TLR2 (Cheng et al., 2008) or TLR4 (Sandri et al., 2008). We therefore chose Ca2+ mobilization as an assay to compare the different SAA1 isoforms for their efficacy at FPR2. In previous studies, we have observed that RBL-FPR2 cells produced robust Ca2+ flux when stimulated with FPR2 agonists (He et al., 2014, He et al., 2003). As shown in Fig. 3, SAA1.1 and SAA2.2 were highly efficacious in the induction of Ca2+ mobilization with peak values of fluorescence reaching 2.51±0.06 and 2.60±0.08, respectively. In contrast, SAA1.3 and SAA1.5 induced less Ca2+ mobilization with much lower peak values even when used at higher concentrations, suggesting that SAA1.3 and SAA1.5 were less efficacious compared to SAA1.1 and SAA2.2 (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Calcium mobilization in RBL-FPR2 cells stimulated with SAA1 isoforms and SAA2.2. The cells were loaded with calcium sensitive reagent (FLIPR Calcium 5) and changes in intracellular Ca2+ was determined. (A) Typical calcium traces in response to the indicated SAA isoforms (10 μM). (B) Dose-response curves are shown as means ± SEM, based on peak Ca2+ fluorescence from 3 separate experiments.

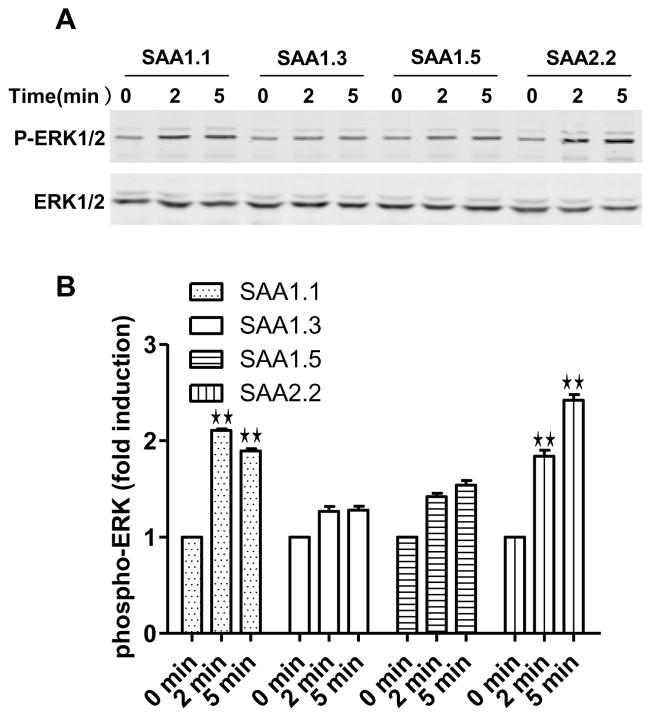

Activation of FPR2 leads to a series of signaling events, including phosphorylation of signaling molecules such as the protein kinase ERK. Although ERK activation can also be triggered by activated TLR2 and TLR4 in primary macrophages and neutrophils, only FPR2-transfected RBL cells but not the untransfected cells responded to SAA with ERK phosphorylation (data not shown). Stimulation of RBL-FPR2 cells with the SAA1 isoforms resulted in a pattern that matches the potency of each SAA isoforms tested in the chemotaxis and Ca2+ mobilization assays (Fig. 4). Taken together, these results show that SAA1.1 and SAA2.2 are more active at FPR2, whereas SAA1.3 and 1.5 are less active.

Fig. 4.

SAA-induced phosphorylation in RBL-FPR2 cells. Serum-starved RBL-FPR2 cells were stimulated with SAA (2 μM). Phosphorylation of ERK1/2 (P-ERK1/2) was determined by Western blotting using an anti-phospho-ERK antibody. Total ERK level was determined with an anti-ERK antibody. (A) Representative blots from one of the three independent experiments. (B) Relative levels of ERK phosphorylation. Densitometry intensity of phosphorylated ERK was normalized against that of total ERK. Data shown were mean ± SEM based on separate experiments. The SAA1.1- and SAA2.2-stimulated samples display higher levels of phosphorylation when compared with SAA1.3- and SAA1.5-stimulated samples at the same time points (**, p < 0.01).

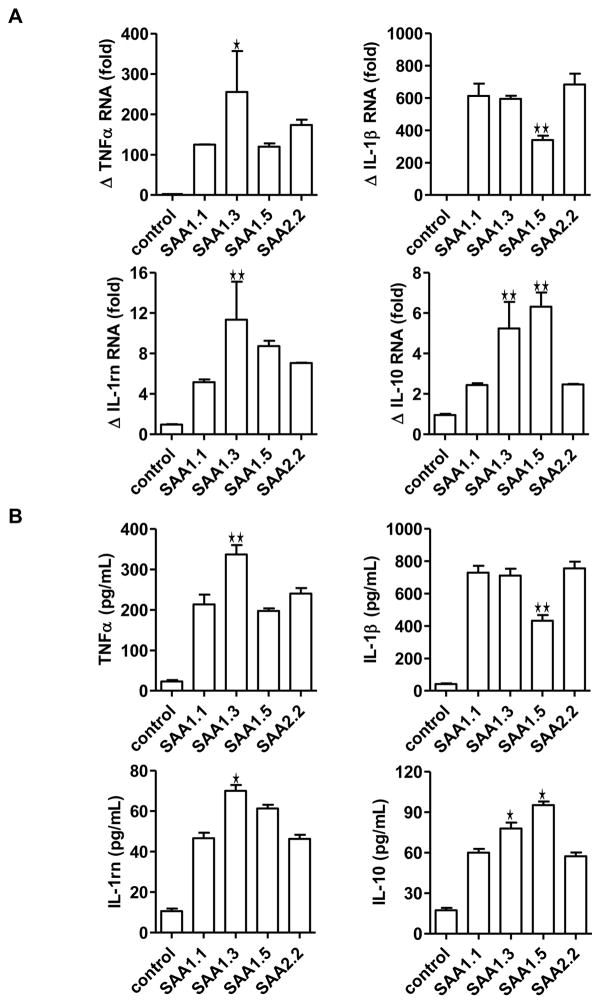

Differential induction of cytokine expression by the SAA1 isoforms and SAA2.2

Published studies have shown that SAA possesses cytokine-like activity (He et al., 2003, Patel et al., 1998). In several published studies, recombinant SAA was found to stimulate the expression of proinflammatory cytokines, chemokines and tissue-degrading enzymes (Cheng et al., 2008, He et al., 2006, He et al., 2009, O’Hara et al., 2004, Sandri et al., 2008, Sodin-Semrl et al., 2004). In these well-controlled studies, these activities of SAA could be distinguished from those of bacterial products such as lipopolysaccharide (LPS). However, it has been difficult to exclude a role for LPS in the observed cytokine-inducing effect of SAA due to the fact that the recombinant SAA used in most published studies were expressed in E. coli. To address this concern, we prepared bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDM) from C57BL/10ScN (Tlr4lps-del) mice, which are defective in LPS signaling due to mutations in the tlr4 gene that abrogated Tlr4 expression (Poltorak et al., 1998). Based on real-time PCR analysis of selected cytokine transcripts and ELISA-based quantification of cytokines released by the activated BMDM cells, SAA1.3 induced higher levels of the TNFα and IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1rn) transcripts than other SAA1 isoforms and SAA2.2 (Fig. 5A and 5B). In comparison, SAA1.5 was less effective in the induction of IL-1β gene, but it promoted IL-10 expression better than other SAA isoforms tested (Fig. 5A and 5B). Because LPS signaling through Tlr4 is no longer an important concern here, the results from this experiment suggest that the SAA1 isoforms tested have the ability to distinguish between different receptors with only one or two amino acid substitutions. The results from this experiment, therefore, provide a structural basis for receptor selectivity by different SAA isoforms in the absence of LPS signaling.

Fig. 5.

Induction of cytokine transcripts and proteins in macrophages treated with SAA isoforms. BMDM from C57BL/10ScN (Tlr4lps-del) mice (1×106 cells/sample) were stimulated with 1 μM SAA for 4 h. (A) The transcripts for selected cytokines (TNFα, IL-1β, IL-1 receptor antagonist, IL-10) were measured with real-time PCR. Changes (Δ) in the relative levels of these cytokine transcripts were shown as mean ± SEM from triplicate measurements. (B) The levels of cytokines secreted by BMDM from C57BL/10ScN (Tlr4lps-del) mice were measured using ELISA. *, p < 0.05, and **, p < 0.01, compared with SAA1.1-stimulated samples.

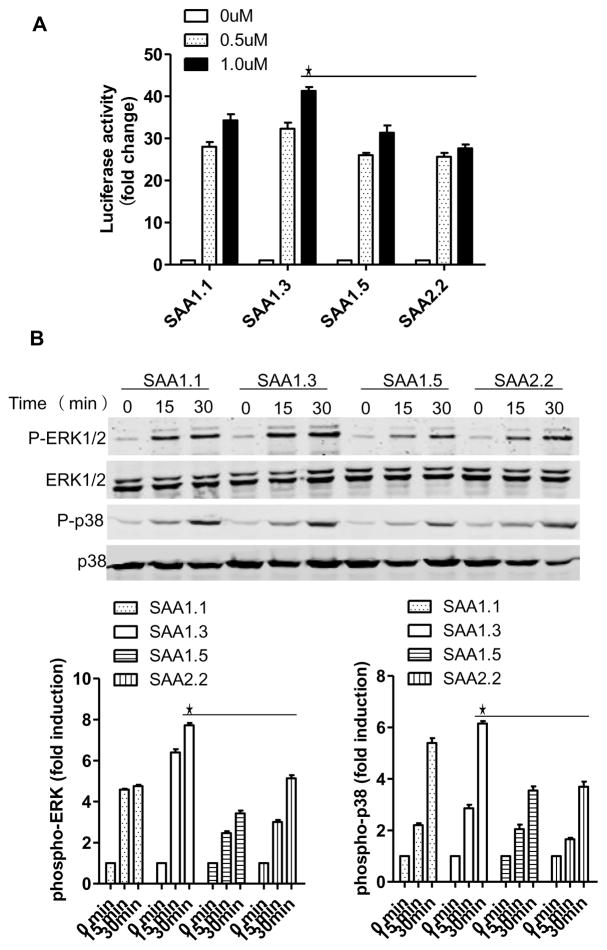

Bioactivity of the SAA1 isoforms at TLR2

In the cytokine induction assay described above, SAA1.3 displayed higher activity than other SAA1 isoforms and SAA2.2. Because SAA1.3 was relatively weak in FPR2-dependent cellular functions (Fig. 2, 3 and 4), it was speculated that SAA1.3 might be more selective for TLR2. This possibility was examined in assays that use transfected HeLa cells expressing TLR2 (TLR2-HeLa). In a TLR2-dependent, NF-κB-driven luciferase assay, SAA1.3 induced higher luciferase activities (Fig. 6A), and the difference was statistically significant when compared with the activities of SAA1.5 and SAA2.2 at 1 μM. To confirm that SAA1.3 preferentially activates TLR2, we next examined phosphorylation of ERK and p38 MAPK after stimulation of the TLR2-HeLa cells with the SAA isoforms. As shown in Fig. 6B, SAA1.3 displayed higher activity than other SAA isoforms examined in the induction of ERK and p38 MAPK phosphorylation. This pattern of TLR2-dependent signaling is similar to that of the SAA-induced luciferase reporter activity above. Together, these results suggest that SAA1.3 is more active at TLR2.

Fig. 6.

TLR2-dependent signaling in transfected cells. HeLa cells stably transfected to express human TLR2 (TLR2-HeLa) were stimulated with the SAA isoforms at different concentrations (A) or at 0.5 μM for different times (B). In (A), the SAA-induced NF-κB driven luciferase activity was shown as fold changes compared to unstimulated cells. In (B), SAA-induced phosphorylation of ERK and p38 MAPK was shown with representative blots (top). Quantification of the blots was conducted based on densitometry intensity of the species, and shown below the blots. Data shown are the mean ± SEM from at least separate experiments. Values from the SAA1.3 samples are higher when compared with SAA1.5- and SAA2.2-stimulated samples at the same time points (*, p < 0.05).

Discussion

Results from this study show that the three SAA1 variants differ in their preference of receptors. SAA1.1 displays properties similar to SAA2.2, and both are potent agonists for the G protein-coupled FPR2. This is shown in FPR2-dependent functional assays including chemotaxis, Ca2+ mobilization and phosphorylation of ERK. In another set of experiments, we found that SAA1.3 is more potent than other tested SAA variants in cytokine induction, most likely through activation of TLR2. Of particular interest, SAA1.5 is much more potent than SAA1.1 and SAA2.2 in the induction of IL-10, an anti-inflammatory cytokine. It also appears that SAA1.5 is less potent in the induction of proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β. These findings provide clues for the identification of SAA-activated pathways leading to the expression of various cytokines, which may involve different receptors and signaling molecules. At present, it remains unclear what combination of signals are required for the induced expression of a given cytokine as shown in this study. Due to technical limitations, we were unable to carry out a large-scale survey of cytokines that may be induced by SAA; however, the use of the Tlr4-deficient C57BL/10ScN mice eliminated a major concern over commercially available recombinant SAA, which is produced by E. coli and can have LPS contamination. It may be concluded that SAA1 allelic variation leads to changes in protein structure and receptor selectivity.

Allelic variants of SAA1 have been studied previously for their association with secondary amyloidosis, as in the case of rheumatoid arthritis (Yamada et al., 2003). The study showed that rheumatoid patients with the SAA1.3 isoform have the highest risk for AA amyloidosis. In addition to SNPs in the coding region resulting in 5 different SAA1 variants (SAA1.1–1.5), SNPs occurring in non-coding sequence have been found to affect SAA1 functions through identified and unidentified mechanisms. Of particular interest is the finding that synonymous codon changes resulting from SAA1 SNPs (e.g., rs12218), which does not lead to amino acid substitution, has been associated with several diseases including increased serum uric acid level and increased body weight (Xu et al., 2013). How this type of SNPs affects SAA1 function remains unclear, but it may be related to altered SAA1 expression level. As an example, the −13C SNP affects the expression level of SAA1 and hence its function (Moriguchi et al., 2005). With the SNPs that cause amino acid substitutions, it has been reported that certain SAA1 isoforms may be more susceptible to degradation by matrix metalloproteases such as MMP-1 (van der Hilst et al., 2008). It is also known that some SAA1 isoforms tend to form fibrils more easily than others (Srinivasan et al., 2013). These findings suggest that amino acid substitutions occurring at two positions in SAA1 are sufficient to alter its structure, leading to functional changes. During the course of this study, Lung et al reported that SAA1 polymorphisms are associated with variation in tumor-suppressive and angiogenic activities based on a study of nasopharyngeal carcinoma (Lung et al., 2014). This study not only established a functional association of the SAA1 allelic variation with a particular type of tumor, but also show that the ability of an SAA1 isoform to interact with the integrin αVβ3 directly correlates with its tumor-suppressive activity. As a result, SAA1.5, which minimally interacts with αVβ3, is defective in its tumor-suppressive function. In the present study, we attempt to delineate the structure-function relationship of different SAA1 variants based on their selectivity for FPR2 and TLR2. Future studies will be focused on the interaction of SAA1 isoforms with other receptors. Our findings may be considered together with other reports on the association of certain SAA1 isoforms with chronic disorders.

A number of recent studies have shown that SAA proteins with high sequence homology actually have different biophysical properties. A comparison of the pathogenic SAA1.1 with the non-pathogenic SAA2.2 in mice revealed that the two proteins differ in their quaternary structure (Srinivasan et al., 2013). Whereas SAA1.1 has a lag phase of a few days for oligomer-rich fibrillation, SAA2.2 displays no lag phase and forms small fibrils. Another study reported that the fibrils formed by SAA1.1 and SAA1.3 differ, and this is attributed to the only amino acid substitution at position 52 (Val in SAA1.1 and Ala in SAA1.3) (Takase et al., 2014). More recently, the crystal structure of SAA has been determined (Lu et al., 2014). There are 4 bundled alpha-helices, forming a funnel shaped structure. The different amino acids between the three SAA1 isoforms are located in alpha helix 3 which, when positioned in the 3D structure, are near the bottom of the funnel (Lu et al., 2014). It is conceivable that the amino acid substitutions resulting from SAA1 polymorphism alter the 3D structure of the SAA protein, thus affecting its interaction with FPR2, TLR2 and αVβ3. Whether the structural changes also affect SAA interaction with high-density lipoprotein and cholesterol efflux remains to be investigated.

In summary, the present study provides experimental evidence for different receptor selectivity between the three SAA1 isoforms. These findings may help to delineate the mechanisms by which different SAA1 variants are associated with chronic diseases. With the structure of SAA now becoming available, it is possible to build a computer-assisted model that simulates the structural changes resulting from SAA1 polymorphism in coding regions, thus advancing our understanding of the structure and function relationship of SAA polymorphism.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant 31270941), from National Basic Research Program of China (973 Program, Grant 2012CB518000), from the Specialized Research Fund for the Doctoral Program of Higher Education of China (Grant 20120073110069), and from National Institutes of Health (Grants AI040176 and AI033503).

Abbreviations

- SAA

serum amyloid A

- FPR2

formyl peptide receptor 2

- TLR2

Toll-like receptor 2

- RAGE

receptor for advanced glycation end product

- BMDM

bone marrow-derived macrophages

- SUMO

small ubiquitin-related modifier

- TEV

tobacco etch virus

- TAL

Tachypleus Amebocyte Lysate

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors have no financial conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ather JL, Ckless K, Martin R, Foley KL, Suratt BT, Boyson JE, Fitzgerald KA, Flavell RA, Eisenbarth SC, Poynter ME. Serum amyloid A activates the NLRP3 inflammasome and promotes Th17 allergic asthma in mice. J Immunol. 2011;187:64–73. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baranova IN, Vishnyakova TG, Bocharov AV, Kurlander R, Chen Z, Kimelman ML, Remaley AT, Csako G, Thomas F, Eggerman TL, Patterson AP. Serum amyloid A binding to CLA-1 (CD36 and LIMPII analogous-1) mediates serum amyloid A protein-induced activation of ERK1/2 and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinases. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:8031–8040. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405009200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buxbaum J. The genetics of the amyloidoses: interactions with immunity and inflammation. Genes Immun. 2006;7:439–449. doi: 10.1038/sj.gene.6364323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai L, de Beer MC, de Beer FC, van der Westhuyzen DR. Serum amyloid A is a ligand for scavenger receptor class B type I and inhibits high density lipoprotein binding and selective lipid uptake. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:2954–2961. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411555200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng N, He R, Tian J, Ye PP, Ye RD. Cutting Edge: TLR2 Is a Functional Receptor for Acute-Phase Serum Amyloid A. J Immunol. 2008;181:22–26. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.1.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Kebir D, Jozsef L, Khreiss T, Pan W, Petasis NA, Serhan CN, Filep JG. Aspirin-triggered lipoxins override the apoptosis-delaying action of serum amyloid A in human neutrophils: a novel mechanism for resolution of inflammation. J Immunol. 2007;179:616–622. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.1.616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fyfe AI, Rothenberg LS, DeBeer FC, Cantor RM, Rotter JI, Lusis AJ. Association between serum amyloid A proteins and coronary artery disease: evidence from two distinct arteriosclerotic processes. Circulation. 1997;96:2914–2919. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.9.2914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He HQ, Troksa EL, Caltabiano G, Pardo L, Ye RD. Structural determinants for the interaction of formyl peptide receptor 2 with peptide ligands. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:2295–2306. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.509216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He R, Sang H, Ye RD. Serum amyloid A induces IL-8 secretion through a G protein-coupled receptor, FPRL1/LXA4R. Blood. 2003;101:1572–1581. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-05-1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He R, Shepard LW, Chen J, Pan ZK, Ye RD. Serum amyloid A is an endogenous ligand that differentially induces IL-12 and IL-23. J Immunol. 2006;177:4072–4079. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.6.4072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He RL, Zhou J, Hanson CZ, Chen J, Cheng N, Ye RD. Serum amyloid A induces G-CSF expression and neutrophilia via Toll-like receptor 2. Blood. 2009;113:429–437. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-03-139923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kluve-Beckerman B, Long GL, Benson MD. DNA sequence evidence for polymorphic forms of human serum amyloid A (SAA) Biochem Genet. 1986;24:795–803. doi: 10.1007/BF00554519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushner I, Rzewnicki D. Acute phase response. 3. Lippincott Willams & Wilkins; Philadelphia: 1999. pp. 317–329. [Google Scholar]

- Lee HY, Kim MK, Park KS, Bae YH, Yun J, Park JI, Kwak JY, Bae YS. Serum amyloid A stimulates matrix-metalloproteinase-9 upregulation via formyl peptide receptor like-1-mediated signaling in human monocytic cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;330:989–998. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.03.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MS, Yoo SA, Cho CS, Suh PG, Kim WU, Ryu SH. Serum amyloid A binding to formyl peptide receptor-like 1 induces synovial hyperplasia and angiogenesis. J Immunol. 2006;177:5585–5594. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.8.5585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J, Yu Y, Zhu I, Cheng Y, Sun PD. Structural mechanism of serum amyloid A-mediated inflammatory amyloidosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:5189–5194. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1322357111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lung HL, Man OY, Yeung MC, Ko JM, Cheung AK, Law EW, Yu Z, Shuen WH, Tung E, Chan SH, Bangarusamy DK, Cheng Y, Yang X, Kan R, Phoon Y, Chan KC, Chua D, Kwong DL, Lee AW, Ji MF, Lung ML. SAA1 polymorphisms are associated with variation in antiangiogenic and tumor-suppressive activities in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Oncogene. 2014 doi: 10.1038/onc.2014.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malle E, Sodin-Semrl S, Kovacevic A. Serum amyloid A: an acute-phase protein involved in tumour pathogenesis. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009;66:9–26. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8321-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriguchi M, Kaneko H, Terai C, Koseki Y, Kajiyama H, Inada S, Kitamura Y, Kamatani N. Relative transcriptional activities of SAA1 promoters polymorphic at position −13(T/C): potential association between increased transcription and amyloidosis. Amyloid. 2005;12:26–32. doi: 10.1080/13506120500032394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanamori M, Cheng X, Mei J, Sang H, Xuan Y, Zhou C, Wang MW, Ye RD. A novel nonpeptide ligand for formyl peptide receptor-like 1. Mol Pharmacol. 2004;66:1213–1222. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.004309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Hara R, Murphy EP, Whitehead AS, FitzGerald O, Bresnihan B. Acute-phase serum amyloid A production by rheumatoid arthritis synovial tissue. Arthritis Res. 2000;2:142–144. doi: 10.1186/ar78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Hara R, Murphy EP, Whitehead AS, FitzGerald O, Bresnihan B. Local expression of the serum amyloid A and formyl peptide receptor-like 1 genes in synovial tissue is associated with matrix metalloproteinase production in patients with inflammatory arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:1788–1799. doi: 10.1002/art.20301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly S, Cant R, Ciechomska M, Finnegan J, Oakley F, Hambleton S, van Laar JM. Serum Amyloid A (SAA) induces IL-6 in dermal fibroblasts via TLR2, IRAK4 and NF-kappaB. Immunology. 2014 doi: 10.1111/imm.12260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel H, Fellowes R, Coade S, Woo P. Human serum amyloid A has cytokine-like properties. Scand J Immunol. 1998;48:410–418. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.1998.00394.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poltorak A, He X, Smirnova I, Liu MY, Van Huffel C, Du X, Birdwell D, Alejos E, Silva M, Galanos C, Freudenberg M, Ricciardi-Castagnoli P, Layton B, Beutler B. Defective LPS signaling in C3H/HeJ and C57BL/10ScCr mice: mutations in Tlr4 gene. Science. 1998;282:2085–2088. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5396.2085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandri S, Rodriguez D, Gomes E, Monteiro HP, Russo M, Campa A. Is serum amyloid A an endogenous TLR4 agonist? J Leukoc Biol. 2008;83:1174–1180. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0407203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sodin-Semrl S, Spagnolo A, Mikus R, Barbaro B, Varga J, Fiore S. Opposing regulation of interleukin-8 and NF-kappaB responses by lipoxin A4 and serum amyloid A via the common lipoxin A receptor. Int J Immunopharmacol. 2004;17:145–156. doi: 10.1177/039463200401700206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srinivasan S, Patke S, Wang Y, Ye Z, Litt J, Srivastava SK, Lopez MM, Kurouski D, Lednev IK, Kane RS, Colon W. Pathogenic serum amyloid A 1.1 shows a long oligomer-rich fibrillation lag phase contrary to the highly amyloidogenic non-pathogenic SAA2.2. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:2744–2755. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.394155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su SB, Gong W, Gao JL, Shen W, Murphy PM, Oppenheim JJ, Wang JM. A seven-transmembrane, G protein-coupled receptor, FPRL1, mediates the chemotactic activity of serum amyloid A for human phagocytic cells. J Exp Med. 1999;189:395–402. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.2.395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun L, Zhu Z, Cheng N, Yan Q, Ye RD. Serum amyloid A induces interleukin-33 expression through an IRF7-dependent pathway. Eur J Immunol. 2014 doi: 10.1002/eji.201344310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takase H, Tanaka M, Miyagawa S, Yamada T, Mukai T. Effect of amino acid variations in the central region of human serum amyloid A on the amyloidogenic properties. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;444:92–97. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uhlar CM, Whitehead AS. Serum amyloid A, the major vertebrate acute-phase reactant. Eur J Biochem. 1999;265:501–523. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00657.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Hilst JC, Yamada T, Op den Camp HJ, van der Meer JW, Drenth JP, Simon A. Increased susceptibility of serum amyloid A 1.1 to degradation by MMP-1: potential explanation for higher risk of type AA amyloidosis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2008;47:1651–1654. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ken371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu XL, Sun XT, Pang L, Huang G, Huang J, Shi M, Wang YQ. Rs12218 In SAA1 gene was associated with serum lipid levels. Lipids Health Dis. 2013;12:116. doi: 10.1186/1476-511X-12-116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada T, Okuda Y, Takasugi K, Wang L, Marks D, Benson MD, Kluve-Beckerman B. An allele of serum amyloid A1 associated with amyloidosis in both Japanese and Caucasians. Amyloid. 2003;10:7–11. doi: 10.3109/13506120308995250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan SD, Zhu H, Zhu A, Golabek A, Du H, Roher A, Yu J, Soto C, Schmidt AM, Stern D, Kindy M. Receptor-dependent cell stress and amyloid accumulation in systemic amyloidosis. Nat Med. 2000;6:643–651. doi: 10.1038/76216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye RD, Boulay F, Wang JM, Dahlgren C, Gerard C, Parmentier M, Serhan CN, Murphy PM. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. LXXIII. Nomenclature for the formyl peptide receptor (FPR) family. Pharmacol Rev. 2009;61:119–161. doi: 10.1124/pr.109.001578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]